“Best Educational Position in America”

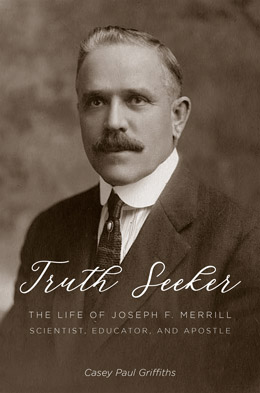

Casey Paul Griffiths, “'Best Educational Position in America,'” in Truth Seeker: The Life of Joseph F. Merrill, Scientist, Educator, and Apostle (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 159‒88.

Leaving the University of Utah to become the head of the Church educational system gave Joseph F. Merrill a new sense of purpose in his professional life. He always retained a warm affection for the university, but the possibilities of new challenges and the chance to take the lead in determining the destiny of an entire system of education reignited the passion absent for many years in his work. He wrote to his daughter, “How [do I] like the job? I have the finest and best educational position in America—none excepted and I would not choose to exchange it for another.” His glee at the new position spilling over, he continued, “Happy? To the brim. . . . I have never thought of my present position, hence had no aspirations for it.” Merrill was an outsider to Latter-day Saint education, a fact he recognized upon entering the post. Reflecting on this, he wrote, “Remarkable! I who have never attended a church school a day in my life being called to preside over the Church school system.”[1] Speaking in a Church general conference a few months after his call, he declared, “There is no kind of education in the world that is so fine and so elevating and so good and so important as religious education.”[2]

Now, Merrill was able to play on a larger stage. His travels as head of the Church educational system took him throughout the western United States, and his work during this time gave rise to his most important and lasting contributions. The chance for him to make a large impact on the system he now led came quickly, in large measure because Merrill’s induction into the world of Latter-day Saint education came in the midst of a period of remarkable transformation.

Latter-day Saint Education before 1928

“The course of the church educational system from 1900 to 1930,” wrote an eminent Church historian, “resembled nothing quite so much as a balloon.”[3] During the first part of the twentieth century, the educational programs set up by the Latter-day Saints enjoyed a rapid expansion, with dozens of Church-sponsored high schools opening throughout the Intermountain West. Established in locations as far north as Raymond, Canada, and as far south as Colonia Juárez in Mexico, the Church academies, as they were known, were organized in most of the major Latter-day Saint settlements in the West, though most of the academies remained in Utah. By the time Joseph F. Merrill became the head of the Church educational system in 1928, the academies were all but gone, supplanted by a seed Merrill had planted sixteen years earlier: the seminaries. Merrill’s work as Church commissioner completed the transformation of Latter-day Saint education, establishing the basic model still in use throughout the world today.

When Joseph F. Merrill became the head of the Church educational system in 1928, he entered a system based on a radically different mindset than the one he had encountered in his university career. Merrill saw his work at the university as inclusive—he wanted to use the common language of learning to build bridges between the opposing worldviews of the Latter-day Saint and nonmember elements of his community. He saw the university as the great meeting place of ideas, where different creeds came together in a gathering of minds.

The Latter-day Saint educational system was born of the siege mentality common when the Church was under attack on all sides because of the controversies surrounding plural marriage and Latter-day Saint separatism. In 1888 the First Presidency of the Church announced the formal creation of the Church Board of Education, telling Church members, “We feel that the time has arrived when the proper education of our children should be taken in hand by us as a people.” The missive continued, “Religious training is practically excluded from the district schools. The perusal of books that we value as divine records is forbidden. Our children, if left to the training they receive in these schools, will grow up entirely ignorant of those principles of salvation for which the Latter-day Saints have made so many sacrifices.”[4] From the inception of the Latter-day Saint system, the goal was to create an environment for transmitting the gospel culture of the Saints to the next generation.

For a generation, these Latter-day Saint schools prospered; they remained the dominant educational system in the state of Utah from 1895 to 1910. However, the system was not without its limitations. The geographic reach of the academies was limited. Many of the smaller settlements lacked the population and funding to justify an academy. Many academies were established and then failed. To provide religious training for its youth, the Church established an innovative program of supplemental religion classes outside the regular school day.[5] The religion classes held promise, but many Church leaders feared they went too far in blurring the line between church and state. Many of the religion classes were taught in the same buildings, often by the same teachers, as the secular classes.[6] Enrollment in the academies continued to grow, but the percentage of students enrolled was surpassed by the even greater growth of Utah’s public high schools. By 1910 enrollment in public schools surpassed the academies for the first time. Church members started to feel the strain of maintaining a double system, paying tuition to the Church schools while also paying taxes to support the public schools. In the years following, the number of students in public schools rose sharply, while the percentage of students in the Church schools began to gradually decline.[7]

At the same time, Church leaders also began to feel the financial strain of maintaining the Church school system. In 1915 Church President Joseph F. Smith, normally a staunch advocate of the Church schools, proposed that some of the smaller academies should be turned over to the state and converted into public high schools in order to divert more funds to the Church schools, which were providing teacher training. President Smith felt the academy system had reached the limits of its expansion, and confronted the reality that the Church would “have to trim [its] educational sails to the financial winds.”[8] Even David O. McKay, a former principal of the Weber Academy, recognized that maintaining the Church academies “[was] a policy which [would] eventually bankrupt the Church.”[9] As time progressed, it became clearer that the Church would have difficulty duplicating and competing with the growing public school system. The animosity of the public schools and government support also diminished, so it was not seen as such a detrimental system.

During these discussions, the seminary program started by Merrill at Granite High School in 1912 grew quietly in the background. In 1915 a second seminary was established in Brigham City. Merrill later explicitly stated that he did not intend for the seminaries to replace the academies but only to bring weekday religious instruction to public school students.[10] Nevertheless, the seminary program spread rapidly and began to overtake the academies as the dominant component in Church education. One of the primary factors driving this shift was economic. While a Church school required hundreds of thousands of dollars to construct and maintain, only twenty-five hundred dollars was necessary to build the seminary building at Granite High.[11] Only one teacher, and not an entire faculty, taught religion at a seminary.

Seminary held benefits over the religion-class program as well, since it took advantage of the fact that most Latter-day Saint students in a local area were already gathered at public schools. Classes held during the school day removed the need for a separate gathering outside of school time and allowed access for students who would be unable to attend otherwise. Such limited costs made it possible to bring seminary to nearly every community with Latter-day Saint students, while the academies served only a limited area. Within a decade after Merrill helped launch the first seminary, the program had grown to include thirty-two seminaries, with an enrollment of forty-four hundred students.[12]

The direction of the Church’s educational programs saw a major shift in 1920. In 1919 the Church Board of Education reorganized the governing hierarchy of Church education, naming Apostle David O. McKay as the first commissioner. Stephen L. Richards served under McKay as first assistant commissioner and Richard R. Lyman as second assistant. The board appointed Adam S. Bennion, a former principal of Granite High School, as the superintendent of schools.[13] Within several months, McKay proposed the practical measure that “all small schools in communities where LDS influence predominates . . . be eliminated” and that the Church “maintain [only] four or five schools with the aim of giving first-class training to teachers.”[14]

Soon afterward, the Church Board of Education announced the closure or transfer to state control of nearly all of the Church academies. A few of the stronger academies—specifically Ricks, Weber, Snow, and Dixie—received upgrades in status to junior colleges, designed mainly to function as teacher training schools. In the new system, Brigham Young University acted as the parent school to these junior colleges, which in turn acted as feeder schools to BYU.[15] The beginnings of this arrangement marked a major change in the Church’s educational policies. Rather than competing with secular systems, the Church instead chose to cooperate, offering religious education via the seminary program to supplement the education of its youth. In 1922 Church President Heber J. Grant illuminated this new policy in a speech at one of the Church schools. The purpose of Church education, Grant said, “was to make better Latter-day Saints. But for this reason, I am convinced there would be no need of having church schools as ordinary education can be secured at the expense of the taxpayers of the state.”[16]

Throughout the 1920s, the restructuring of the system continued. At a meeting of the Church Board of Education, Bennion submitted a report clearly explaining the financial position of the Church schools and the seminaries. Bennion estimated that the relative cost of operating the schools was $818,426.01, compared to $197,502.59 for the seminaries, a nearly one-to-eight ratio in favor of the seminaries. In light of these facts, Bennion called for the Church to withdraw altogether from the field of secular education in favor of providing a supplementary religious education to Latter-day Saint students. He also recommended establishing collegiate-level seminaries near university and college campuses with large numbers of Latter-day Saint students. Summarizing his arguments, Bennion explained, “My judgment leads me to the conclusion that finally and inevitably we shall withdraw from the academic field and center upon religious education. It is only a question as to when we may best do that.”[17]

The most ardent opponent to the plan was David O. McKay, who urged caution in so quickly abandoning the Church schools. McKay wanted to seek a compromise between the two alternatives of maintaining the Church schools and moving entirely in favor of the seminaries. He told the board, “The influence of seminaries, if you put them all over the Church, will not equal the influence of the Church schools that are now established.”[18] McKay’s dissent in 1929 seems to be on the grounds that the 1920 restructuring decision was carried out with the assumption that the academies would be maintained for the purpose of training teachers, who would then be a good influence throughout the schools and seminaries. In McKay’s view, by eliminating the Church schools, the opportunity to train the necessary number of teachers was lost.

Commissioner of Education

For reasons not completely known, Bennion suddenly announced his resignation at a meeting of the Ogden Kiwanis Club in December 1927.[19] During his speech, Bennion declared, “This will probably be the last time I shall appear before you in my present position. It is only a few months when I shall leave the Church school service, and be a man of the business world.”[20] The move was apparently unknown to Church leaders—no notice of Bennion’s departure appears in the official minutes of the board until two months later.[21] Within a few days, Merrill was called into the office of the First Presidency and offered Bennion’s position.[22]

Merrill’s acceptance of the post came at a particularly challenging moment for Church education. During his nine years as the effective head of Church educational programs, Bennion had launched a radical program of restructuring. Nearly all the Church schools closed in favor of seminaries, and the remaining schools were overhauled, becoming small colleges with an emphasis on teacher training. By the time of Bennion’s departure, discussion centered on a total withdrawal of Church efforts in the field of secular education. Some leaders favored the closure of all Church schools, including the colleges and Brigham Young University, in favor of religious education programs. Emblematic of the change was the title given to Merrill when he officially took over the post in February 1928. Instead of Bennion’s title of “Superintendent of Church Schools,” Merrill was designated as the “Church Commissioner of Education,” a title deemed broad enough to “cover the administration of the other fields of the department.”[23] One of the underlying truths behind the title change was that, given the current trends, within a few years there might be no Church schools to supervise.

Years after his accession to the post, Merrill recalled Church leaders’ feelings about education. He wrote, “When I was asked by the First Presidency if I would accept the position being vacated by Dr. Bennion, I asked for a statement of policy. They replied, ‘We have concluded to spend all the money we can afford for education in the field of religious education.’ My first duty would be to eliminate the junior colleges from the Church School system.” Merrill also remembered a request “to promote the extension of the seminary system, just as widely as our means would permit. . . . The First Presidency told me that this was the plan they would like to see followed. But the junior colleges were to be closed.”[24]

Before the Church withdrew from the field of collegiate education, however, Church leaders expressed a keen desire for some sort of equivalent seminary program for college students. The creation of a system to provide religious training for Latter-day Saint college students had been contemplated for many years before Merrill became commissioner. In July 1912 Horace G. Cummings, then the Church superintendent of schools, reported to the Church board that “the authorities of the state University [the University of Utah] are anxious to have some steps taken towards caring for the religious welfare of the Mormon students at that institution.” Cummings reported, “At present nothing is being done to look after them spiritually, and as a result some of our best educated boys and girls are losing interest in the gospel and becoming tainted with erroneous ideas and theories.”[25] Merrill’s name is not specifically mentioned in the report, but the appearance of such a request to the Church board precisely when Merrill was rushing to prepare the first seminary program at Granite High is too large a coincidence to ignore. In the same meeting where Cummings reported on the need for religious education at the university, Merrill’s letter requesting the hire of the first seminary teacher appeared as an earlier agenda item. A second request for religion classes at the U came in September, only weeks after the opening of the first seminary.[26] Three years later, Cummings brought the question to the board again, writing, “I wish to call your attention to the urgent need of making some provision to care for the Latter-day Saint students attending the State University.” According to Cummings, “The presidency of that school and many of its teachers have urged that some kind of building be erected by the Church, near the campus, and that a course in theological training be established for which they would be willing to give college credit.”[27] A few weeks later, Cummings wrote to Merrill, appointing him as head of the committee designated to look after students at the school for an indefinite period of time.[28] It looked as if the creation of a collegiate brand of seminaries was on the way, but the discussion then faded away, overshadowed by larger concerns about the Church educational budget.

Creation of the Institute Program

The discussion on collegiate seminaries was resurrected over a decade later, this time to soothe the concerns of a worried father. Norma and Zola Geddes entered the University of Idaho as freshmen in 1925. The two girls, the only children of William C. Geddes, an influential business executive in the lumber industry, entered their schooling with some apprehension, as they were two of only a handful of Latter-day Saint students at the school. The branch of the university they attended was located in Moscow, Idaho, a small college community hundreds of miles away from traditional Latter-day Saint strongholds. A few weeks after the girls arrived at school, Geddes arrived in town to visit his daughters. Inquiring about the meeting place of the local Latter-day Saint branch, Geddes, a devoted member of the Church, walked with his children to the local hall of the International Order of Odd Fellows, where Church services were conducted every Sunday. Walking up a narrow staircase to the pungent, dark hall, Geddes was appalled. As part of their regular Sunday routine, his daughters set about sweeping the hall to remove old cigarette butts and picking up empty bottles of bootleg whiskey from the night prior. Norma later remarked, “It took a hardy soul and strong desire to attend church.” Her father was so disgusted by the conditions that he contacted Preston Nibley, an old friend whose father, Charles W. Nibley, was a member of the Church’s First Presidency.[29]

J. Wyley Sessions, the first Latter-day Saint institute teacher. Courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, BYU.

J. Wyley Sessions, the first Latter-day Saint institute teacher. Courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, BYU.

Meanwhile, in Salt Lake City a young mission president stepped off the train, exhausted from traveling nearly halfway across the globe. J. Wyley Sessions was returning home after seven years in South Africa, an assignment so far away from home that he jokingly claimed he could travel any direction from his assignment and be closer to home.[30] Financially destitute from his missionary service, Sessions arrived for a meeting with the First Presidency, fully expecting to receive a comfortable position in the Church-owned Utah-Idaho Sugar Company. He enjoyed a congenial visit with Church President Heber J. Grant and his counselors, Charles Nibley and Anthony W. Ivins. His position in the company seemed assured when suddenly Charles Nibley stopped talking midsentence and abruptly announced, “Heber! We’re making a mistake! I’ve never felt good about Brother Sessions in the sugar business—he may not like it. There’s something else for this man.” After a moment of silence, Nibley looked directly at Sessions and said, “Brother Sessions, you’re the man for us to send to the University of Idaho to take care of our boys and girls who are attending the university there, and to study the situation and tell us what the Church should do for Latter-day Saint students attending state universities.”[31]

Sessions responded less than enthusiastically, protesting, “Oh no! We’ve been home just twelve days today, since we arrived from more than seven years in the mission system, are you calling me on another mission?” In reply Grant said, “No, no, Brother Sessions, we’re just offering you a wonderful professional opportunity. Go downstairs and talk to the Church superintendent, Brother Bennion, and then come back and see us about 3 o’clock.” Years later Sessions would recall his conflicted feelings upon leaving the meeting: “I went, crying all the way. I didn’t want to do it. But just a few days later our baggage was checked to Moscow, Idaho, and there [we] started the LDS Institutes of Religion.”[32]

Sessions was an unlikely candidate for the job. He was not a professional educator but an agronomist, a fact that likely contributed to his shock when the First Presidency assigned him to Moscow. Despite the fact that the Church had dozens of qualified teachers at its colleges and a growing number of competent religion teachers in the seminary program, he was sent to Moscow. Sessions himself wrestled with his qualifications for the position, later noting, “I could do something about farm fertilizer, but I didn’t know anything about the Bible and religious teaching!”[33]

When Sessions arrived in Moscow, he was greeted with suspicion, if not outright hostility, by many members of the community. An association of local church ministers organized university faculty members and a number of local business leaders into a committee charged with preventing any attempts by Sessions to “Mormonize” the university.[34] In the face of this opposition, Sessions dove into his assignment with gusto. He and his wife, Magdalene, began taking graduate classes at the university. He joined the local chapter of the Kiwanis Club and became an active member of the Chamber of Commerce.[35] Sessions began using these affiliations to build a network of support, even turning some of his most bitter foes into fast friends. For example, at Chamber of Commerce dinners, Sessions manipulated the seating arrangements whenever possible to sit next to Fred Fulton, head of the committee appointed to oppose his work. Unable to resist Sessions’s charm, Fulton finally turned to his foe at one of the dinners and said, “You son-of-a-gun, you’re the darndest fellow. I was appointed on a committee to keep you out of Moscow and every time I see you, you come in here so darn friendly that I like you better all the time.” The grinning Sessions replied, “I’m the same way. We just as well be friends.” The two remained fast friends for the remainder of Sessions’s time in Moscow.[36]

By the time Merrill was appointed as Church commissioner, Sessions was in his second year in Moscow. Devoting his time to winning the support of the community, Session made little progress toward launching the collegiate venture. The instructions he received from Heber J. Grant before his arrival in Moscow reflected a frustrating amount of vagueness about the aims of the new venture. According to Sessions’s later recollection, the only direct instruction he received from Grant was, “Brother Sessions, go up there and see what we ought to do for the boys and girls who attend state universities and the Lord bless you.”[37] Church Board of Education records concerning the collegiate seminaries present only a rough concept of spiritual mentoring, not a fully formed educational venture. When Adam S. Bennion presented the initial proposal to the Church board in 1926, he remarked, “In the days when I was needed, help did not come through any organization, but the two men who helped me most in the University of Utah were Milton Bennion and James E. Talmage. If we could have at the University of Utah a strong man who could draw the students to him and whom they could consult personally and counsel with, such a man would be of infinite value. I am thinking of Moscow University in that same way.”[38]

Like Bennion, Joseph F. Merrill brought to his position the memories of his educational experiences as a young Latter-day Saint student in the East. Sessions wrote to Merrill seeking advice: “I have been working on a plan for the organization of our Institute and the courses we should offer in our weekday classes. I confess that the building of a curriculum for such an institution has worried me a lot and it is a job that I feel unqualified for.” Merrill’s reply two days later captures his vision for the fledgling program. Merrill told Sessions that the objective of the new collegiate classes was to “enable our young people attending these colleges to make the necessary adjustments between the things they have been taught in the Church and the things they are learning in the university, to enable them to become firmly settled in their faith as members of the Church.” Merrill saw the new program not as a strictly religious venture but as a bridge between the worlds of faith and reason. He continued, “When our young people go to college and study science and philosophy in all their branches, they are inclined to become materialistic, to forget God, and to believe that the knowledge of men is all-sufficient. . . . Can the truths of science and philosophy be reconciled with religious truths?” Merrill wanted a logical approach toward religion, like any other university subject. He argued, “Personally, I am convinced that religion is as reasonable as science; that religious truths and scientific truths nowhere are in conflict; that there is one great unifying purpose extending throughout all creation; that we are living in a wonderful, though at the present-time deeply mysterious, world; and that there is an all-wise, all-powerful Creator at the back of it all. Can this same faith be developed in the minds of all our collegiate and university students? Our collegiate institutes are established as means to this end.”[39]

In devising the institute program, Merrill and Sessions envisioned offering more than just religion classes. A year prior to Sessions’s arrival in Moscow, two seminary teachers, Andrew Anderson and Gustive Larsen, began teaching collegiate religion classes at the College of Southern Utah.[40] What distinguished Sessions’s efforts from Anderson’s and Larsen’s were his intentions to launch an entire program designed to meet the spiritual, intellectual, and social needs of his students. To assist him in this endeavor, Sessions enlisted his wife, Magdalene, who devised a varied program of social and cultural activities.[41] Under their supervision, the institute became an all-out effort to form the scattered students into their own community at the university.

The new program also envisioned a larger audience than just Latter-day Saints. Encouraged by Merrill, Sessions reached out to educators at the university, members of the Church or otherwise, to assist in crafting the new venture. Even the eventual name for the program came from a Methodist, not a Latter-day Saint. Sessions developed a close friendship with Dr. Jay G. Eldridge, a professor of German language and literature at the university. As he and Eldridge walked past the construction site of the new building, Eldridge inquired about what Sessions planned to call it. Up to this point, the most common name was the “collegiate seminaries.”[42] Sessions told his companion he had no idea, and Eldridge replied, “I’ll tell you what the name is. What you see up there is the Latter-day Saint Institute of Religion at the University of Idaho north campus.” Eldridge told Sessions that when his church built a similar structure, it would be called the Methodist Institute of Religion, hopefully leading to other denominations following suit with their own institutes.[43] The suggestion was forwarded to Merrill at Church headquarters, who sent back a letter addressed to “the Director of the Latter-day Saint Institute of Religion—Moscow, Idaho.” When other institutes were founded, the name remained, becoming the official title of the program.[44] The other denominations never launched their own “institutes of religion,” though around the same time Jewish groups formed the Hillel Foundation; Catholics, the Newman Foundation; and Methodists, the Wesley Foundation—all organizations intended to help college-age students find a spiritual home during their studies.[45]

While Sessions and Merrill agreed on the basic philosophy behind the new program, they argued over the size and cost of the new building. Sessions later half-jokingly described Merrill as “the most conservative, economical General Authority of this dispensation.”[46] Pleading his case directly to the First Presidency, Sessions told Heber J. Grant, “President Grant, I cannot go back to Moscow and build a little shanty at the University of Idaho.” The Church President cautiously replied, “If we give you $40,000, you will return and ask for $49,000 or $50,000.” Sessions shot back, “President Grant, I promise I will not ask you for $45,000 or $50,000, but I will not promise that I will not ask for $55,000 to $60,000.” Grant, smiling, answered, “Of course, the Moscow building must be nice.” A budget of $60,000 was allotted for the construction of the building. When the structure was completed, $5,000 was returned to President Grant, who remarked incredulously, “I did not think it possible or that I should live to see this occur.”[47] Sessions wanted even the physical appearance of the institute to set a precedent for others to follow, taking as his motto, “If it’s the LDS Institute, it’s the best thing on campus.”[48]

The original Moscow Institute of Religion was intended to be a classroom, social club, and home away from home for the students at the University of Idaho. Courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, BYU.

The original Moscow Institute of Religion was intended to be a classroom, social club, and home away from home for the students at the University of Idaho. Courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, BYU.

The Moscow institute building was dedicated on 25 September 1928, with Merrill traveling to appear in person.[49] The dedicatory prayer was given by Charles W. Nibley, a fitting feature of the occasion, given that Nibley made the initial suggestion to send Sessions to Moscow. In just a few short years, the institute came to be widely respected on the campus. The program started by Sessions and his wife began a tradition of excellence. During the 1930s, students living at the institute won the campus scholarship cup so often they were eventually excluded from competition.[50] The institute also won praise from outside observers. Ernest O. Holland, president of Washington State College, visited the building several times and remarked to several gatherings of educators that the institute program came nearer to solving the problem of religious education for college students than any other program he knew of.[51] The same year a second institute was founded in Logan, Utah. Sessions went on to found additional institutes in Pocatello, Idaho, and Laramie, Wyoming. He eventually became the head of the Division of Religion at Brigham Young University.[52]

For Merrill, the founding of the institutes fulfilled a longing he had felt ever since his days as a young graduate student wandering on Sundays from church to church in the streets of Baltimore. Where Merrill had lacked a spiritual home and a mentor to reconcile the worlds of science and religion, Latter-day Saint students now had both in the institute program. In a speech given at the dedication of the Pocatello institute, Merrill spoke to this need, saying, “When students go to college they are faced with new problems, some of them disturbing to their religious faith. They hear, read, and are taught some things that seem in conflict with religious views previously held. What shall they do? Are adjustments possible?” Merrill declared that “the Latter-day Saints are firm believers in the harmony of all truth. To them it is impossible that truths discovered in the realms of science and philosophy shall be in conflict with the truths of religion.” Surprisingly, Merrill then criticized the hard-headed partisans of both the scientific and religious factions, continuing, “Our understanding of truth is often faulty. The chaff often conceals the kernel. Dogmatism raises its arrogant hand and smothers clear thinking. . . . Religious faith need not retreat from nor surrender in any of the fields of research or learning. Scholarship can never put God out of existence nor find a substitute for Him. This is the abiding confidence of the Latter-day Saints.”[53]

Deciding the Fate of Latter-day Saint Higher Education

The institute program promised a flexible, inexpensive system of reaching Latter-day Saint college students throughout the country. If it succeeded on the level approaching the seminary program, the institutes could potentially replace the system of junior colleges in Utah, Idaho, and Arizona, just as the seminaries had replaced the Church academies. The idea of closing all Church educational institutions, including Brigham Young University, had been hotly debated by the board even before Merrill was appointed as commissioner. Merrill’s predecessor, Adam S. Bennion, told the board in no uncertain terms, “My judgment leads me to the conclusion that finally and inevitably we shall withdraw from the academic field and center upon religious education. It is only a question as to when we may best do that.”[54]

The question was seemingly settled by the time Merrill was appointed, and he pursued the goal of saving the Church colleges by transferring them to state control with single-mindedness. Under Bennion’s direction, the Brigham Young College in Logan closed in 1926, and negotiations were underway to transfer the rest of the schools to state control or, if necessary, close them. Before he accepted the position of commissioner, Merrill asked for a clarification of the Church’s stance regarding these schools. He would later recall in a letter to his brother, “When I was asked by the First Presidency if I would accept the position being vacated by Dr. Bennion, I asked for a statement of policy. They replied, ‘We have concluded to spend all the money we can afford for education in the field of religious education.’” Merrill’s task seemed clear: “My first duty would be to eliminate the junior colleges from the Church School system, just as the B.Y.C. had been eliminated a year and half before, and to promote the extension of the seminary system, just as widely as our means would permit. . . . The junior colleges were to be closed.[55]

Before he could move forward, however, Merrill sought a clear consensus from the Church Board of Education concerning the matter. Wasting no time, he raised the question in a meeting with the Church board after assuming the post of commissioner. The ensuing discussion raised the board’s hope that the junior colleges in Utah, Idaho, and Arizona might not be eliminated altogether but perhaps transferred to state control and continued. Merrill was directed to work toward converting the schools to state control as quickly as possible.[56]

J. Wyley Sessions standing on the steps of the Moscow Institute of Religion. Courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, BYU.

J. Wyley Sessions standing on the steps of the Moscow Institute of Religion. Courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, BYU.

Merrill immediately began writing to members of the Utah state superintendent’s committee for the study of junior colleges. He wrote to one member of the committee, saying that he felt the junior colleges were “the next step in the advance in our educational development in the state.”[57] Merrill’s motives in pushing for such a rapid transfer to the state emerges in his surviving correspondence. He wanted to avoid the closure of the schools; he wanted them to continue under state control. Members of the Church board supported his feelings on the matter. On 17 January 1929, the board unanimously passed a resolution stating, “We favor the establishment of junior colleges under public auspices and the enactment of the legislation necessary to accomplish this end.”[58]

The school in the most danger was the Latter-day Saint College (LDS College), located in the heart of Salt Lake City. Knowing its survival was unlikely if it remained an independent school, Merrill attempted to make the college an auxiliary of the University of Utah. He wrote to Edward H. Snow, a member of the state Board of Equalization, about his plans to save the school. “I think the outstanding practical point I make is that we can convert the LDS College temporarily into an auxiliary of the University of Utah, where we can do first year college work on the University plane, without any cost to the state,” he told Snow. He continued, “This expense, then that the State would have to bear, might be put into a fund for the taking over of one or two of our junior colleges. Thus the state will be saved any additional expense at the present time and the whole movement can get a start.”[59]

The letter concludes on a cautionary note, with Merrill informing Snow that if the offer was not accepted, he would be forced to recommend the immediate elimination of all junior college work at LDS College, thus depriving the state of a valuable resource. Whether or not Merrill actually intended to do this or was simply trying to give the state a motive to move quickly cannot be told. When the state rejected the offer, a portion of the school’s collegiate department survived and eventually became LDS Business College (later Ensign College).[60]

While trying to save at least a portion of the LDS College, Merrill found himself engaged in an intense campaign to manage a successful transfer of the rest of the Church junior colleges to the state. February 1929 witnessed a flurry of activity on Merrill’s part to persuade legislators to take over control of the schools. By this time two bills that could effect a successful transfer of the Church schools to state control were before the legislature. The first, the Candland Bill, favored a takeover of the junior colleges, making them independent, locally controlled institutions. The second, the Hollingsworth Bill, would reorganize Snow and Weber Colleges as branches of the University of Utah. Merrill favored the Candland Bill, feeling that keeping the schools independent would be more economical and beneficial in the long run.[61]

Undermining Merrill’s efforts, however, was a growing sense of doubt among the state’s legislators, who questioned whether Church leaders were united in their efforts to transfer or close the schools. Merrill wrote to one school official to dampen rumors of division between the Church board and the Church Department of Education on the issue. Quoting directly from the minutes of the Church board’s decision, Merrill laid out the proposition, unequivocally stating the Church’s position on the junior colleges: “The attitude of the Department of Education is one of extreme friendliness to the enactment of junior college legislation. We have told the Governor that this Department would cooperate one hundred percent with the State in making it possible for the State to begin this movement without additional revenues or further delay.”[62]

The next day an editorial was published in the Deseret News designed to communicate to the legislators just how serious the Church leaders were about the closures: “The General Church Board of Education at a meeting Wednesday afternoon decided to close at least two of the Church junior colleges in Utah on or before June 15th, 1930. . . . The feeling has been growing that changing conditions force the closing of other schools in the immediate future.” The editorial pointed out the generosity of the Church’s offer, continuing, “The Church Commissioner of Education has proposed a plan of cooperation to the State and the University, enabling the Church to withdraw gradually from the junior college field, to avoid throwing the full burden upon the public school system all at once and to avoid the immediate need of additional state revenues to support junior college works as per the Candland bill.” The conclusions threw down the gauntlet to the legislature: “The question is does the public care to take advantage of the successful pioneer work in this field done by the Church?”[63]

The legislature’s hesitation was not entirely unjustified. The 1920s were a difficult period economically for Utah as the state struggled to recover from a postwar economic slump. One Utah historian referred to this period as the “Little Depression.”[64] The onset of the Great Depression, only months away, would make things worse. Many in the state legislature felt it was the wrong time to launch a junior college system. On 8 February that year, Merrill received a letter from state senator C. R. Hollingsworth expressing sympathy toward his desires but also stating that the financial condition of the state would not permit the establishment of junior colleges at the time. Two days later, Merrill wrote a lengthy letter in reply, reassuring the senator of the plan’s feasibility and desirability.

The drive to transfer the schools was a clear demonstration of how far The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints had moved into the American mainstream in the early twentieth century. Only a generation earlier, the move to establish Church schools was seen as a necessity to preserve the unique culture of the Saints; now Merrill spearheaded a movement to place almost all Latter-day Saint students in public high schools and colleges. He wrote to a colleague in the legislature, “I have always thought that there was an absurdity in the Church and State competing in the educational field. The ideal condition, I think, is one in which everybody supports the public school system from A to Z, from kindergarten to the university. Therefore, like my predecessor, Dr. Bennion, I am very desirous of getting the Church out of the field of secular education in which I do not believe it belongs.”[65]

While Merrill maintained a cordial tone in his letters, he became more direct as the opposition mounted. Writing to the superintendent of schools in Ogden, he plainly stated, “If Ogden does not care to have a junior college, the neutral attitude is exactly the one to take, but please be advised that the days of maintenance of Weber College by the LDS Church are probably numbered.” He went on to say, “Personally, I am anxious to do all I can to avoid a condition in which Ogden will be without a junior college, but I cannot avoid this condition single-handed.” He added a forceful warning, “You will observe . . . that we are doing all in our power to make favorable the passing of the Candland Bill. It is now up to the University, and to the Legislature. In any case, this Department is going ahead eliminating junior colleges. Of course we would greatly prefer to eliminate only when the public is ready to begin, but we are serving notice of our intentions. Does Ogden want a junior college? If so, my suggestion is that Ogden get its coat off and go to work.”[66]

It may be noted that Merrill’s style was markedly different from his predecessor, Adam S. Bennion. Even colleagues in the department noted that Merrill lacked the “liberal warmth and perspective” Bennion possessed.[67] Bennion was an English literature major and an eloquent speaker and writer. While Merrill could be eloquent, his background as a scientist led him to communicate through blunt facts. His public speeches were filled with more honest, plain statements than rhetorical flourish. Merrill may also have been expressing a desire to let the educational community and legislature know that there was a new sheriff in town, sending a clear signal about Church intentions concerning the schools in language that was about to become even more direct.

Merrill met with the state committee and explained the details of the plan, wanting the state to know in no uncertain terms that the Church was serious about its offer. The committee was skeptical. Merrill left the meeting frustrated, feeling the legislature did not appreciate the seriousness of his offer. “The offer I made to the Governor and the University on behalf of this Department, that we would cooperate fully to enable the State to begin support of junior colleges outside of Salt Lake City, has been treated very lightly, almost scoffingly,” he later wrote to Senator Hollingsworth. He continued, “If this Legislature does not act, the date of closing will be hastened. In the Church colleges there are now enrolled approximately fourteen hundred junior college students. I am telling you only the plain truth when I say the Church will no longer carry this burden and it will drop it much sooner than otherwise if the University and the State do not care to accept our offer.”[68]

Clarification of the Church Position on the Junior Colleges

Even while Merrill played hardball with the state, dissent existed among Church leaders over the schools’ fate. While the way forward existed clearly in Merrill’s mind, some confusion remained as to how the policy should be executed. When Merrill asked the First Presidency for a clear statement of policy concerning the schools, he received only a vague direction to read the minutes of the board. Reporting his findings, Merrill wrote to Anthony W. Ivins, a member of the First Presidency, “I find among other things that President Nibley is recorded as having said: It is easier to formulate some policy with three or four than with twenty. Let us form some definite policy and work to that end. If it is to establish seminaries, let us establish them. If it is to go and continue and compete with the public schools, why let us go ahead, but the main thing is to get some definite policy for the future. I make this suggestion as a motion.”[69] Merrill took Nibley’s statement that the policy should be formed by “three or four” men—to mean the office of the Church Commissioner, along with the First Presidency.

However, Merrill was surprised to find members of the General Board of Education still making suggestions on the matter. He included just a sampling of the mixed messages he received from different members of the Church board: “Brother McKay recently submitted a document relative to the maintenance of our schools to the Presidency. Since the meeting of the General Board I have met with President Nibley, who asked me not to let Brother McKay swerve me from the plan of eliminating some more of our schools.” He continued, “I went to see President Grant, who told me that the Church did not have the money to continue the schools and the development of seminaries. I told him in some detail of what I had written to the Governor and others, of talks I had had, and so on. He approved the suggestion that we should work to eliminate more of our schools. . . . I have felt, therefore, that I am expected to work toward further elimination; so I have been doing it.”[70]

The most determined advocate of the continuation of Church schools was David O. McKay, a young, energetic Apostle and, like Merrill, a career educator. In the opposite direction, the First Presidency was pushing to eliminate the schools as soon as possible. Merrill’s own feeling at the time seemed to be in favor of eliminating some schools, but his tone was cautious. A few months after his appointment, he wrote privately, “The field of education is so extensive that every dollar that the Church can spare for educational purposes must be used for religious education. . . . But in all of our planning I believe we should keep in mind what is wise, economical, and best.”[71]

While Merrill was a strong proponent of the seminary system, it appears that he did not favor the total elimination of all Church schools, especially Brigham Young University. Before he assumed the post as commissioner, he wrote in a letter to Franklin S. Harris, the president of BYU, “If my views can be approved by the Board you will have, I think, no reason to regret my recent appointment.”[72]

All these forces came to a head in a critical meeting of the Church board on 20 February 1929. Merrill forced the board to finally make a choice by placing on the agenda the question, “Shall Weber and at least one other junior college be closed on or before June 15, 1930?” He informed the board of his efforts to eliminate Church schools but flatly declared his aversion to a simple closure, depriving the state of a large part of its system of higher education. The only alternative was to have the state take over the junior colleges, but paradoxically, Merrill felt that the legislature would not take the Church seriously unless the Church announced the closure of one or more of the junior colleges. Otherwise, the legislature would continue to assume that the Church would maintain the colleges indefinitely, even if the state never took them over. A decisive closure might shock the legislature into taking action on the school issue.[73]

Two members of the First Presidency spoke out in favor of Merrill’s plan. Anthony Ivins spoke first, declaring that, according to his understanding, the Church wanted to close the schools as quickly as possible in favor of seminaries and institutes. Recognizing confusion on the subject, Ivins requested the board secretary read the minutes to see if a decision had actually been reached. A brief reading of the minutes showed that several meetings had been devoted to the subject, but the final word on the matter had been deferred to the First Presidency. Upon hearing this, Merrill directly asked President Heber J. Grant for a clear statement of policy. President Grant replied that it was Church policy to close the schools as quickly as possible.

The debate was settled until President Ivins asked if there was any understanding to the contrary. At this point David O. McKay spoke up, declaring that he found no action establishing such a policy in his reading of the board minutes. If such a policy did exist, it originated with an act of the First Presidency and not the board. Grant replied that after a series of discussions, Brigham Young College had been closed, which clearly settled the question. President Charles Nibley restated the financial benefits of a seminary system over the Church schools and expressed the belief held by some board members that the religious instruction in seminaries was better than in Church schools, though he acknowledged that the seminaries could never fully replace the schools. At this point McKay cut to the heart of the matter, stating that his understanding was that the policy applied to the Church high schools only and not to the junior colleges or Brigham Young University.[74]

At this point Merrill was several months into negotiations with the state, and such divisiveness among the Church board was seriously undermining his work. It seems clear that by February 1929 the board had only indicated that the general goal was to eliminate some Church schools. How far the board was willing to take this policy and just how many schools should be eliminated had never been decided in any concrete way. The Church commissioner and First Presidency had acted independently of the board to this point, but it was evident that a united decision from the board was necessary to take such a monumental step as closing the junior colleges. Any decision made to that effect would have a huge impact on the future direction of Church education. For McKay the stakes were personal. He had served as principal of the Weber Academy before it became a junior college and had always maintained close ties to the school.[75] The thought of closing an institution so close to his heart may have been what spurred him into action.[76]

Grant finally spoke, declaring that the policy covered all Church schools. Even BYU would eventually be considered for closing or transfer, just as the junior colleges would be. Grant expressed his feeling that it “almost breaks one’s heart” to think of closing the schools after they had accomplished so much good, but Church finances simply could no longer support them.[77]

At this point Stephen L. Richards moved for the board to officially sustain and approve the Presidency’s decision in order to clarify the record. McKay spoke in opposition, stating that he did not wish to be considered as not sustaining the First Presidency but that he could not vote in favor of eliminating the Church colleges. The motion was seconded by President Ivins and carried.[78]

Grant then addressed Merrill’s specific question, stating, “You can put it down that unless we definitely announce that some of these schools are to be closed at a certain time and then stand by that decision, the state will take no action. If we do not carry out the terms of our announcement we shall be considered as merely ‘bluffing’ and shall not be taken seriously in further eliminations.”[79]

Regarding what schools would be closing, Richards questioned whether they should specifically name any schools. He suggested simply stating that at least two junior colleges would be closed by 15 June 1930. The motion was seconded and carried, with David O. McKay dissenting.

After the vote McKay continued to press the issue. He felt that school closures would cause the Church to lose control over the training of teachers. In his opinion it would be better to slow the growth of the seminary program in favor of retaining the junior colleges. Seminaries and institutes were still largely untested, he argued, and more time was needed to determine if they were a suitable replacement for the schools. He also deemed it necessary to consult the local Church members where the schools were located and gain their approval before the Church made any decisions.[80] While Merrill left the meeting with the clarification he had been seeking, he may have gotten more than he hoped. It is clear that he never favored the total closure of BYU, even though he was now under orders to work toward closing the school. Merrill’s firm desire was to transfer the schools, not to close them entirely.[81]

Whatever Merrill’s feelings, the board’s decision gave him some added leverage, and he began using it to his advantage. In late February 1929 the board publicly announced the closure of two schools by June 1930. Merrill knew that the first school closed would be LDS College, and he threw his efforts into somehow saving it. Writing to Senator Alonzo Irvine, Merrill informed him that Weber College, Snow College, and LDS College were the three schools under consideration for closing. He again offered to give LDS College to the University of Utah, expressing a willingness to take five hundred incoming freshmen, a move that would save the state $75,000 a year. He also reminded the senator of the low cost of taking over the physical facilities at Weber and Snow compared to building colleges from scratch. He ended with another direct call to action: “If no junior college legislation is passed, the LDS College will be one of those closed by the end of the school year, and our opportunity to assist the State in this matter will have passed. The above is plain statement of the facts in the case, and I think it is well that you should know them.”[82]

Writing to other legislators, Merrill continued to press the Church’s need to divest itself of the schools. In a letter to Senator Ray E. Dillman, chairman of the Utah legislative committee on education, he stated, “The Church must now withdraw from the junior college field. It has, however, demonstrated the advisability, the feasibility, and the practicability of junior colleges. But the finances of the Church will no longer permit of a continuance of junior college maintenance. The State is distressed, but not so much as the Church is. . . . There will be no turning back, however, from our decision to begin closing our junior colleges at the end of next year.”[83]

The course was set for the closure of all Church schools in favor of seminaries and institutes. With a clear directive from Church leaders to close the schools, and the continued obtuse reaction of the state legislature toward Merrill’s attempts to turn the schools over to the state, it looked as if the junior colleges were headed for closure. However, the Church now possessed a viable alternative in the growing seminary and institute programs. The fate of the Church schools was sealed, and religious education was the future. Within a few months, though, the wisdom of this change in direction would come into serious doubt.

Notes

[1] Joseph F. Merrill to Edith Merrill, 26 March 1928, box 14c, folder 4, Joseph F. Merrill Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University (BYU).

[2] Joseph F. Merrill, in Conference Report, 6–8 April 1928, 38.

[3] Thomas G. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 158.

[4] James R. Clark, ed., Messages of the First Presidency, ed. James R. Clark, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1965), 3:168.

[5] See D. Michael Quinn, “Utah’s Educational Innovation: LDS Religion Classes, 1890–1929,” Utah Historical Quarterly 43 (Fall 1975): 379–89; and Brett Dowdle, “‘A New Policy in Church School Work’: The Founding of the Mormon Supplementary Religious Education Movement” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 2011).

[6] Brett D. Dowdle and Casey Paul Griffiths, “A Godsend for the Salvation of Israel: The Creation of the Seminary Program,” in Joseph F. Smith: Reflections on the Man and His Times, ed. Craig K. Manscill, Brian D. Reeves, Guy L. Dorius, and J. B. Haws (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2013), 386–88.

[7] Milton L. Bennion, Mormonism and Education (Salt Lake City: Department of Education of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1939), 177.

[8] Minutes of the Church Board of Education, 27 January 1915, UA 566, box 24, folder 8, Centennial History Project Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, BYU.

[9] Mary Jane Woodger, “David O. McKay, Father of the Church Educational System,” in Out of Obscurity: The LDS Church in the Twentieth Century, ed. Susan Easton Black (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 382.

[10] Joseph F. Merrill, “A New Institution in Religious Education,” Improvement Era, January 1938, 55–56.

[11] Charles Coleman and Dwight Jones, “History of Granite Seminary,” (Salt Lake City: unpublished manuscript, 1933), MS 2237, Church History Library, 6.

[12] James R. Clark, “Church and State Relationships in Education in Utah” (PhD diss., Utah State University, 1958), 309.

[13] Kenneth G. Bell, “Adam Samuel Bennion: Superintendent of LDS Education, 1919 to 1928” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1969), 47–48.

[14] Woodger, “David O. McKay,” 382.

[15] Clark, Church and State Relationships, 312–13.

[16] Alexander, Mormonism in Transition, 165.

[17] Minutes of the Church Board of Education, 23 March 1926, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[18] Minutes of the Church Board, 23 March 1926, Church History Library, 74–75.

[19] Bennion’s exact reasons for resignation are unknown, though some have suggested he clashed with Church leaders over their conservative attitudes. See John Andrew Braithwaite, “Adam Samuel Bennion, Educator, Businessman, and Apostle” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1965), 34. It should be noted that Bennion continued to serve on the Church Board of Education even after his resignation as superintendent of Church schools. See Bell, “Adam Samuel Bennion: Superintendent of LDS Education,” 97.

[20] “Bennion to Quit Church Schools,” Salt Lake Telegram, 15 December 1927.

[21] Minutes of the Church Board, 1 February 1928, 32, Church History Library.

[22] “Dr. Adam S. Bennion Quits Schools, Accepts Position with Power Firm, Dr. Joseph F. Merrill Is Successor,” Deseret News, 28 December 1927.

[23] Minutes of the Church Board, 22 March 1928, Church History Library, 192–93.

[24] Joseph F. Merrill to Amos N. Merrill, 13 December 1951, MSS 1540, box 4, folder 2, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[25] Minutes of the Church Board, 29 May 1912, Church History Library, 1–2.

[26] Minutes of the Church Board, 29 May 1912; 27 September 1912, Church History Library, 1–2.

[27] Minutes of the Church Board, 15 September 1915, Church History Library, 4.

[28] Horace G. Cummings to Joseph F. Merrill, 20 October 1915, Joseph F. Merrill Collection, Church History Library.

[29] Dennis A. Wright, “The Beginnings of the First LDS Institute of Religion at Moscow, Idaho,” Mormon Historical Studies 10, no. 1 (Spring 2009): 65–70.

[30] James Wyley and Magdalene Sessions, interview by Richard O. Cowan, 29 June 1965, transcript and audio recording in author’s possession (hereafter designated as Sessions 1965 oral history), 3.

[31] Sessions 1965 oral history. James Wyley Sessions, interview by Marc Sessions, 12 August 1972, MS 15866, Church History Library (hereafter designated as Sessions 1972 oral history), 8–9.

[32] Sessions 1965 oral history; Sessions 1972 oral history. See also Leonard Arrington, “The Founding of LDS Institutes of Religion,” Dialogue 2, no. 2 (Summer 1967): 137–47; and Ward H. Magleby, “1926—Another Beginning, Moscow, Idaho,” Impact (Winter 1968).

[33] Sessions 1965 oral history, 10.

[34] Sessions 1972 oral history, 5.

[35] Magleby, “1926,” 23; Sessions 1965 oral history, 13.

[36] Sessions 1972 oral history, 5; Sessions 1965 oral history, 13.

[37] Sessions 1965 oral history, 9.

[38] Bell, “Adam Samuel Bennion: Superintendent of LDS Education,” 90.

[39] Magleby, “1926,” 31–32. As one of the first native Utahns to obtain a PhD, Merrill was intimately familiar with the struggles he describes in his letter. He experienced them himself as a young man as he attended Johns Hopkins University. See Casey P. Griffiths, “Joseph F. Merrill: Latter-day Saint Commissioner of Education, 1928–1933” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 2007), 24–30; and Joseph F. Merrill, “The Lord Overrules,” Improvement Era, July 1934, 413, 447.

[40] A. Gary Anderson, “A Historical Survey of the Full-Time Institutes of Religion of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1926–1966” (EdD thesis, Brigham Young University, 1968), 44.

[41] Moscow Institute of Religion, Sixty Years of Institute, 1986, CR 102 205, Church History Library, 5.

[42] Bell, “Adam Samuel Bennion: Superintendent of LDS Education,” 93.

[43] Sessions 1965 oral history, 12.

[44] Magleby, “1926,” 27.

[45] Terry Lyn Tomlinson, “The Institute of Religion Movement and the Religious Education Foundations Movement: Divergent or Convergent Movements in Religious Education in American Higher Education?” (paper presented at the Mormon History Association 49th Annual Conference, San Antonio). The Catholic foundation began in 1929, the Methodist in 1938. Founded in 1923, the Jewish Hillel Foundation preceded the institutes of religion by several years. Tomlinson, “Institute of Religion Movement,” 6–10.

[46] J. Wyley Sessions to Ward H. Magleby, 29 December 1967, box 2, folder 5, Sessions Collection, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, BYU.

[47] Sessions to Magleby, 29 December 1967, Sessions Collection, BYU.

[48] Sessions 1965 Oral History, 11.

[49] Magleby, “1926,” 32.

[50] “Sharing the Light: History of the University of Idaho LDS Institute of Religion, 1926–1976,” Sessions Collection, BYU.

[51] Arrington, “Founding of LDS Institutes,” 143.

[52] See Casey Paul Griffiths, “The First Institute Teacher,” Religious Educator 11, no. 2 (2010): 174–201.

[53] Joseph F. Merrill, “LDS Institutes and Why,” Improvement Era, December 1929, 135–37.

[54] Minutes of the Church Board, 23 March 1926, Church History Library, 28.

[55] Joseph F. Merrill to Amos N. Merrill, 13 December 1951, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[56] Church Board of Education Minutes, 22 March 1928, Church History Library, 197.

[57] Joseph F. Merrill to D. C. Woodward, 21 May 1928, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[58] Joseph F. Merrill to C. H. Skidmore, 1 February 1929, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[59] Joseph F. Merrill to Edward H. Snow, 28 January 1929, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[60] A. Gary Anderson, “Historical Survey,” 138–9.

[61] Joseph F. Merrill to A. P. Bigelow, 27 March 1929, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[62] Merrill to Skidmore, 1 February 1929, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[63] Deseret News editorial, 2 February 1929, Merrill Papers, BYU (emphasis added).

[64] Thomas G. Alexander, Utah: The Right Place (Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith, 2003), 276, 302.

[65] Joseph F. Merrill to C. R. Hollingsworth, 6 February 1929, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[66] Joseph F. Merrill to W. Karl Hopkins, 9 February 1929, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[67] Russel B. Swenson, interview by Mark K. Allen, 13 September 1978, UA OH 32, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, BYU.

[68] Merrill to Hollingsworth, 14 February 1929, Merrill Papers, BYU (emphasis added).

[69] Joseph F. Merrill to Anthony W. Ivins, 1 February 1929, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[70] Merrill to Ivins, 1 February 1929, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[71] Joseph F. Merrill to O. W. Adams, 26 July 1928, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[72] Joseph F. Merrill to Franklin S. Harris, 28 December 1927, Harris Presidential Papers, cited in Ernest L. Wilkinson, ed., Brigham Young University: The First One Hundred Years, 5 vols. (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1975), 2:85.

[73] Church Board of Education Minutes, 20 February 1929, Church History Library, 210–13.

[74] William E. Berrett, CES History Resource Files, 1899–1985, CR 102 174, Church Archives, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City.

[75] See Jeanette McKay Morrell, Highlights in the Life of President David O. McKay (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1966), 56–57.

[76] Church Board of Education Minutes, 20 February 1929, Church History Library, 210–13.

[77] Church Board of Education Minutes, 20 February 1929, Church History Library, 210–13.

[78] Church Board of Education Minutes, 20 February 1929, Church History Library, 210–13.

[79] Church Board of Education Minutes, 20 February 1929, Church History Library, 210–13.

[80] Berrett, CES History Resource File, 1899–1905.

[81] Church Board of Education Minutes, 20 February 1929, Church History Library, 210–13.

[82] Joseph F. Merrill to Alonzo Blair Irvine, 27 February 1929, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[83] Joseph F. Merrill to Ray E. Dillman, 1 March 1929, Merrill Papers, BYU.