Bruce C. Hafen, "Love and Delight: Teaching Our Children Diligently About Christ," in The Tragedy and the Triumph, ed. Charles Swift (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 1–26.

Elder Bruce C. Hafen is a General Authority Emeritus who served as president of the St. George Utah Temple from 2010 to 2013. He was formerly president of BYU-Idaho, dean of the J. Reuben Clark Law School, and provost of Brigham Young University.

The Joseph Smith Building at Brigham Young University has special meaning for Marie and me. We first met in a religion class in the original JSB. As a reminder to us, we have kept a brick that was part of that old building until this building replaced it in 1991.

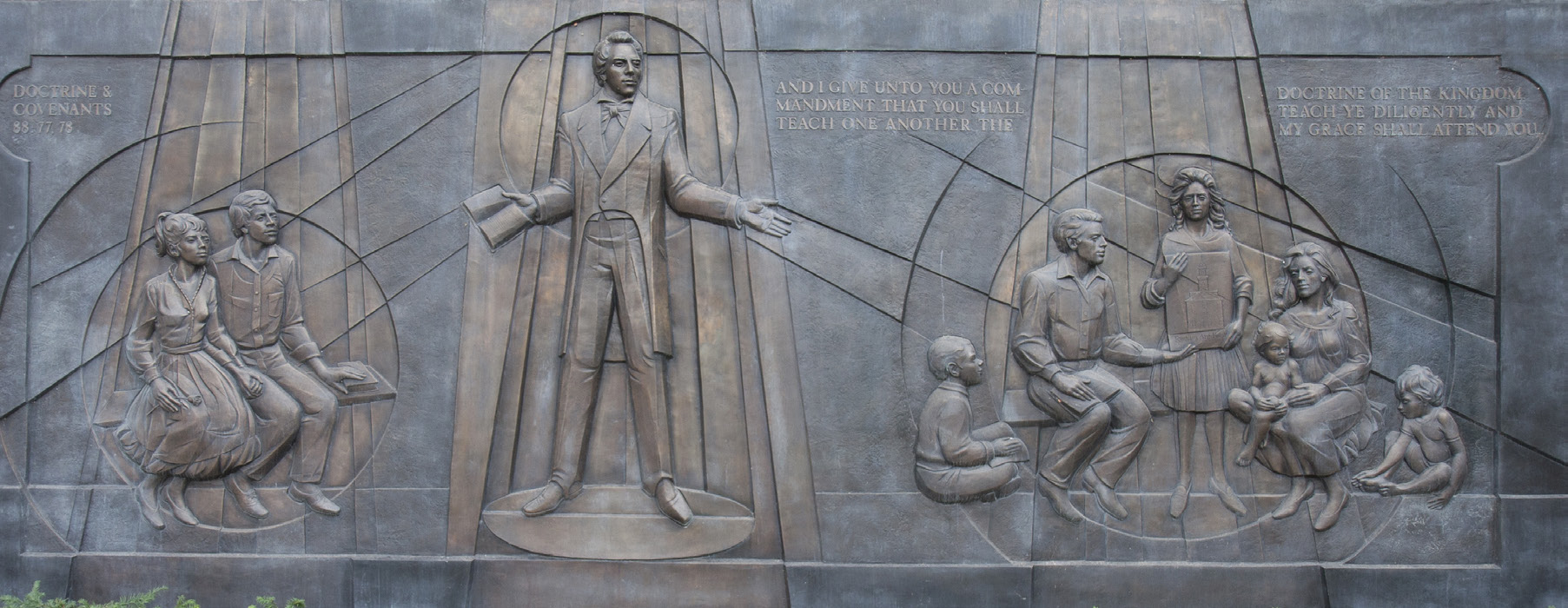

I invite you to visualize the large bronze relief sculpture now on the north face of this new JSB. It was beautifully crafted by Franz Johansen of the BYU art faculty to depict the building’s purpose as the religious teaching center of the campus. At first Franz drew several sketches of Joseph alone, but something was missing—the connection between Joseph and BYU’s mission. A prayerful search for that connection led to the Lord’s words to Joseph—now part of the sculpture: “I give unto you a commandment that you shall teach one another the doctrine of the kingdom. Teach ye diligently and my grace shall attend you” (Doctrine and Covenants 88:77–78).

So the sculpture shows Joseph Smith in the center, standing as if in a keyhole, holding the keys of this dispensation. He gestures with his right hand as if teaching two current BYU students. He gestures with his left hand toward the children those BYU students hope to teach some day. And streaming from above are small but bold vertical lines that suggest the grace of heaven. These lines intersect with diagonal lines that suggest the interplay between grace and teaching if we teach one another diligently—because that diligence is the condition on which the grace is bestowed. Diligent means careful, serious, and determined.[1] It derives from a Latin term that means loving or taking delight in.[2] .

Franz Johansen, Relief sculpture on BYU’s Joseph Smith Building.

Franz Johansen, Relief sculpture on BYU’s Joseph Smith Building.

Courtesy of Richard Crookston.

Looking at the children in the sculpture draws my mind to Nephi’s stirring words about talking, rejoicing, and writing about Christ—so that “our children may know . . . ” Here is Nephi’s larger context: “For we labor diligently [there’s that strong conditional word again—probably no coincidence] . . . to persuade our children, and also our brethren, . . . to believe in Christ . . . for we know that it is by grace that we are saved, after all we can do.” Yet we also “keep the law of Moses, and look forward with steadfastness unto Christ, until the law [of Moses] shall be fulfilled. . . . We talk of Christ, we rejoice in Christ, . . . we prophesy of Christ, and we write according to our prophecies that our children may know to what source they may look for a remission of their sins.” And we teach them “the deadness of the law [of Moses] . . . [so] that [our children] may look forward unto that life which is in Christ” (2 Nephi 25:23–27).

I am intrigued at how Nephi here introduces the idea that we should “persuade” our children to believe in Christ. His opening language includes one of the best-known verses in scripture about the Restoration’s unique doctrine of grace—which differs significantly from both the Catholic and Protestant traditions: “it is by grace that we are saved, after all we can do” (2 Nephi 25:23).

When I was a German missionary in the 1960s, the Latter-day Saint translation of this sentence into German read, “aus Gnade selig werden, trotz allem, was wir tun können.” The word trotz means “in spite of” or “regardless of.” In other words, whoever translated that verse into German thought the English phrase meant we are saved by grace regardless of (or in spite of) whatever we do of our own accord. That’s vintage Martin Luther, the great German Reformer, and it reflects other Luther-like ideas about humankind’s natural depravity, our lack of free will, and our total incapacity for any righteous action except what the righteousness of Christ “enables” when he elects to dwell in us.

Annie Henrie, Great in the Sight of God. © Annie Henrie Nader.

Annie Henrie, Great in the Sight of God. © Annie Henrie Nader.

When living in Germany again forty years later, I found that the Saints were using a new Book of Mormon translation, updated by the Scriptures Committee of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The crucial verse now reads, “durch Gnade errettet werden, nach allem was wir tun können.” Nach is the primary change—and it literally means “after.” So the phrase now reads exactly as Joseph wrote it—we are saved by grace after, or in addition to or along with, all we can do. Hooray for the Scriptures Committee—because on the hinge of that one word swings such a huge doctrinal and historical door.

I am concerned that, according to some non–Latter-day Saint observers, recent writing and conversations about grace and Christ’s Atonement among today’s Latter-day Saints are moving the Church toward an inaccurate understanding of the relationship between grace and works that draws on and is becoming more consistent with Luther-like doctrines—especially grace-oriented evangelical Protestantism. For example, one evangelical scholar applauds the work of Latter-day Saint writers who he believes “promote an understanding of the relationship between grace and works that is openly modeled” after evangelical teachings. He sees the work of these writers as a “move away from” Joseph Smith’s teachings about the nature of God and man’s capacity to become like God, as Joseph expressed in the King Follett discourse.[3]

Why does all of this matter? Because the Lord has now restored Christ’s original teachings about the Fall, human nature, the purpose of his Atonement, and the very purpose of life. The doctrines of traditional Christianity were misguided about these issues, undermining our initiative, our incentives, and our confidence in our own capacity to learn, to grow, and to become all that our Father sent us here to become.

The bitterness we taste in life is not because there is something evil or wrong with us, or with God, or with life. Rather, we taste the bitter that we may learn to prize the good and the sweet. And the Atonement of Jesus Christ—the central message of Easter—is not just for the purpose of erasing black marks. It is fundamentally a doctrine of human development that makes our eternal growth both possible and meaningful. Because of the Atonement, we can learn from our experience without being condemned by it.[4]

At the same time, grace does include certain gifts that are free and unconditional—the universal resurrection, Atonement for Adam’s original sin, and the plan of salvation. Because Christ rose from the tomb on that first Easter morning, every one of us will be resurrected. And as Jacob wrote, “it is by his grace, and his great condescensions unto the children of men, that we have power . . . [even to come] upon the face of the earth” (Jacob 4:7, 9), where we may have the opportunity to learn about salvation and eternal life. This universal feature of grace is never earned. We never deserve it, as if we were entitled to it. If the Lord hadn’t freely extended this level of grace to us in the first place, we would all be totally lost and without hope.

Beyond this unconditional dimension of grace, however, its other dimensions are conditional—they are not free gifts. We qualify for this additional level of grace only when we meet certain conditions—not to satisfy some arbitrary standard of “works” in a mathematical grace-works formula, but because of the very nature of human growth. For example, forgiveness is conditioned upon our repentance, which can sometimes make enormous demands of us. Further, the Lord’s words on the outside wall of this building say not just to teach, but “Teach ye diligently and my grace shall attend you” (Doctrine and Covenants 88:78).

And the stories about the Lord’s delivering the Israelites or the Nephites or the handcart companies from their bondage and trauma show that the Savior offers us the grace of his strengthening blessings only as we willingly participate in our deliverance by exerting our own strength and faithfulness to the utmost. This voluntary and active participation is absolutely essential to the growth process that results in our spiritual development. As one handcart tragedy survivor put it, we came to know the Lord in our extremities. We don’t come to know him in our hammocks, but in our extremities. Even as he extends to us his grace, sometimes the Lord stretches us to the outer edge of our extremities.

You might know the story of Agnes Caldwell, the nine-year-old who was among the Martin and Willie handcart survivors. Starving and exhausted, little Agnes walked in freezing snow and wind alongside a rescue wagon while hoping for a ride. Finally the driver asked, “Sissy, would you like a ride?” He took her outstretched hand, but then he clucked to his horses to speed up, pressing Agnes into a run. She thought the driver was “the meanest man who ever lived.” Then, later, when she could stagger no further, he lifted her into the warm comfort of a blanket in the wagon. Only then did she realize that if he had let her ride at her first request, she would have frozen to death. The run increased her circulation. The wagon master’s “severe mercy” saved her life.[5]

Matt Reier, Jesus Christ

Matt Reier, Jesus Christ

The Lord is our wagon master, but only we, like Agnes, can take certain essential steps. And without our complete engagement, it’s not that the Lord’s grace won’t make us grow, but that it can’t. He can’t grow for us. Spiritual strength is like a muscle; it will grow only when it is repeatedly stretched—sometimes further, then further again.

With this doctrinal introduction, that extended passage from 2 Nephi 25 urges us to rejoice, write, prophesy, and teach our children to look to Christ as the source of two great blessings: (1) the remission of sins and (2) that “life” which is in Christ. He is the source of both blessings—but not the sole source. Both also require of us “all we can do.”

Especially in today’s culture of hostility toward religion, we must teach our children diligently to have their own testimonies. They are our most important investigators. But they can’t survive only on light borrowed from their parents or anyone else. The social mainstream is now so polluted that those who want to be believing face the exhausting pushback of wading upstream against the cultural current. Heber C. Kimball famously prophesied of our day that the Lord’s people will face difficulties of “such a [demanding] character” that “it will be necessary for you to have a knowledge of the truth of this work for yourself. . . . The time will come when no man or woman will be able to stand on borrowed light.”[6]

Courtesy of Christina Smith.

Courtesy of Christina Smith.

The rising generation in Mosiah 26 lived in such a time. Unlike their parents, who had heard King Benjamin, many of the young ones could not understand the word of God—so they rejected it. Why couldn’t they understand? “Because of their unbelief,” said Alma. And that attitude of unbelief can be culturally imposed, just as believing attitudes can be inspired by a culture of belief. Belief precedes understanding. Understanding does not precede belief. So we nourish a culture of belief in our homes to help our children understand God’s word.

Moreover, building Zion means building a multigenerational Church—on both sides of the veil. Zion isn’t completely “established” in new locations until it becomes a multigenerational Church. One of the Church’s great challenges today, especially internationally, is our need to increase the percentage of members who have been sealed in the temple. Multigenerational, temple-sealed families are the ideal source, although not the only source, for teaching children in a culture of belief.

Sometimes, though, we don’t foresee the long-term effects of our choices on the next generation. A few years ago in the St. George Temple, I met with an eighty-year-old man who was there to receive his own endowment. When I learned his name and connected a few dots, I found that he’d been raised in a Latter-day Saint home and was the nephew of a former First Presidency member. He had married, he and his wife had several children, and then they were divorced. Life went on, and finally at age eighty he had at last found his way, alone, to the temple. I was thrilled for him. Near the end of our visit, he asked me earnestly, “Can I have my children sealed to me now?”

His former wife had remarried. Neither she nor his now-adult children were active in the Church. I saw his tears, and my heart hurt for him when I had to explain that child-parent sealings must include two parents. And sealings of adult children must be voluntary. No one will be sealed to someone they don’t choose to be sealed to. Even children born in the covenant will remain eternally sealed to their parents only if they want to be.

The good news was that he had come back. He was worthy to receive the holy temple endowment. But it was a bittersweet day for him. As our daughter Sarah d’Evegnee once wrote,

I wonder how many people realize that they are tethering their families to the decisions they make as they navigate uncertainty. Some people don’t give their own historicity enough thought. Others, like the Saints of Nauvoo, invite us to witness their sacrifice and follow their example. They wrote on the Nauvoo Temple wall, “The Lord has beheld our sacrifice. Come after us.”

Sometimes allowing yourself to move forward with even a drop of faith allows you to pass that drop on to your children. If we choose to see ourselves as an isolated figure with isolated choices, we may miss the chance to witness and to learn from the sacrifices of those who came before us. And in doing so, we actually blind our own children so that they never have the chance to see the sacrifices of our ancestors or to make sacrifices of their own. . . . Our choices that take us away from the priesthood can take our whole family away from the priesthood.[7]

In addition, teaching our children diligently asks more of us than just taking them to church. I recently became acquainted with a kindly, older woman whose father I had known years earlier. Her parents were tirelessly faithful people who served in visible Church callings for decades. At one point I asked her if it had been hard for her to see her father be away from home so much, as good a man as he was. She spoke generously of her love and admiration for him. Yet as we continued talking, she expressed a childlike disappointment that she had never felt she had her own testimony, her own deep relationship with the Lord. “My parents had such strong faith,” she said. “I trusted them completely. And that was enough for me.” But now she was wishing she had known more, firsthand, for herself. She had supported her own posterity for years in their mission calls and Church activity, but her lack of spiritual confidence left her feeling a kind of void, limiting her commitment to the temple and to full discipleship.

Carl Bloch, Christ and the Young Child

Carl Bloch, Christ and the Young Child

So we talked about Doctrine and Covenants 46:13–14, the section on spiritual gifts: “To some it is given by the Holy Ghost to know that Jesus Christ is the Son of God. . . . To others it is given to believe on their words, that they also might have eternal life if they continue faithful.” Something about that promise sparked a hopeful look in her eyes. A few days later, I learned from a mutual friend that she was already beginning to fan that spark into her own fire.

Moreover, in announcing the Church’s new emphasis on a “home-centered, Church-supported . . . curriculum” last October, President Russell M. Nelson asked parents to “transform their home into a sanctuary of faith,” rather than assuming that Church meetings are the primary sources of gospel teaching.[8]

These experiences and President Nelson’s counsel have made me want to understand better what parents can do to teach their children how to develop their own testimonies. Just being Church-active parents is simply not enough, not today, if it ever was. People value what they discover far more than they value what they are told. And children make spiritual discoveries only when their parents and other teachers teach them “diligently”—carefully, seriously, lovingly, and with delight.

So I identified a sample of young adults who already have their own secure spiritual moorings, their own life-giving connection with the Lord. Then I asked them to tell me what their parents had done to help them discover him and the gospel’s truth.

For one thing, these parents understand the difference between private and public religious behavior. And they know that private behavior—such as prayer, personal scripture study, and developing a personal relationship with God—is far more likely to lead to adult religious commitments than is public religious behavior alone—such as attending Church meetings or activities, as useful as those things are.

They also know the difference between tradition and testimony. In Mosiah 26, Alma said the rising generation couldn’t understand the word of God because they “did not believe the tradition of their fathers” (Mosiah 26:1). Perhaps instead of teaching them diligently to know the Lord for themselves, their parents had simply taught them a tradition, a history.[9]

Moreover, these parents know the difference between teaching and preaching—and their children saw the difference. As one little boy asked after hearing his grandfather talk in Church, “Was that a true story, Grandpa, or were you just preaching?”

And instead of being shocked or making a crisis out of a child’s honest questions, these parents calmly use the questions to teach. For instance, one fourteen-year-old boy asked, “Mom, is it OK to not believe in God?” She said something like, “What a wonderful question! That shows you are thinking about very important things. Let’s talk more.”

Here are some comments from the young adult sample. First was gratitude to their parents:

- “My parents created an environment of love and of the spirit in our home. I saw them doing what they asked me to do: praying alone, reading the scriptures alone and together. I saw them live the gospel when they didn’t know I was watching.”

- “I watched how my parents treated each other, how they treated each of their kids. And in our family we talked about the gospel every day as a natural and real part of everyday life.”

- “What they put first in their lives showed me what is most important in life.”

- “I have watched them go through the repentance process. That helped me see how the gospel changes lives.”

- “My parents have gotten through tough times because of their faith, and that has shown us kids that it’s real.”

Courtesy of Cody Bell.

Courtesy of Cody Bell.

What had the parents done specifically to help their children develop their own testimonies? Some samples:

- “They turned me to the Lord to find my own answers and encouraged me to live the answers I found. They helped me get to places where I could figure out things on my own—like EFY, girls’ camp, temple baptisms, and Church history sites.”

- “A testimony has to be gained independently. My parents have done their best to make sure their kids gain independence with everything, especially the gospel. I have grown more by studying on my own than having someone else do the studying for me.”

- “Because of their example, they have helped me want to gain my testimony—not just that I need to or should gain a testimony. They taught me the what, who, and how of the gospel. This laid the foundation for what was mine to discover: the why—why I need the gospel in my life.”

- “My parents understood that most kids at some point naturally realize they need to know for themselves. So they let me piggyback on their testimony until I was strong enough to gain my own. They first showed me the motions; now I’m able to stand on my own two feet and teach my own children.” [Notice her natural multigenerational instinct.]

Nephi said they taught their children to have their own faith in Christ, first so they would know to what source they should look for a remission of their sins. Second, Nephi wanted his children to know the “deadness” of a law-of-Moses approach to the gospel so the children could comprehend “that life which is in Christ.”

Carl Bloch, Let the Little Children

Carl Bloch, Let the Little Children

Come unto Jesus.

Christ is the ultimate source not only of forgiveness, but also of charity. He is the source not only of redemption, but also of spiritual strength and perfection. To illustrate, I have a friend whose son was married in the temple, then he and his wife had several children. All were Church-active. After their children were grown, a pattern of tension and criticism began growing between the parents. I’ll not include the details, but within a few years the tension grew into mutual mistrust and sometimes hostility. Yet neither one had violated temple covenants. They said they didn’t want a divorce, but marriage counseling hadn’t helped, and they continually argued about personal issues that filled their lives with miserable contention. And it was getting worse.

When my friend asked for advice, I felt his love and empathy for both of them. But I told him honestly that I didn’t know anything he didn’t know about such difficulties. Then I remembered and shared something I once experienced that, until then, hadn’t struck me as a story about marriage.

During my Church service, I was assigned to review a Church member’s appeal of a stake disciplinary council decision to excommunicate him from the Church. As I reviewed the council’s minutes, I had difficulty understanding why the council had decided on excommunication. Seeking clarification, I called the stake president, a gentle, quiet man who was new in his calling. He said the case involved two capable men in his stake who had once been good friends. Then they had a misunderstanding that gradually escalated into a long and angry quarrel that affected both families, fueled by mutual claims of gossip and bad-mouthing. One of the men, who for years had been a forceful leader in their stake, was so filled with righteous indignation that he demanded the other man’s excommunication. And he persuaded the disciplinary council to agree with him. Then the excommunicated man appealed the council’s decision.

Rather than upholding or denying the appeal, the authorized Church leaders asked the stake president to hold a new disciplinary council. The two men and their supporting witnesses attended again, presenting basically and emotionally what they had done before. After the witnesses were excused and the council began its private deliberations, the two men sat silently smoldering outside the high council room, awaiting the decision.

After a time of silent waiting, one of the men suddenly stood up and walked over to the other man. He knelt down in front of him and began to cry, saying, “What on earth are we doing to each other? I am so sorry! Can you ever forgive me?” The other man was stunned—but his heart melted. Within minutes, the two had embraced, wept, and repeatedly apologized to each other. Then they knocked on the door. The council members were astonished to see these two former adversaries crying in the doorway, their arms around each other. After the two gave a brief explanation, the room erupted in tears of joy, relief, gratitude, and embracing.

The next day the stake president called to tell me what had happened. As I choked back my own tears, I asked if he knew what had prompted the one man to approach the other. He knew only that the Spirit of the Lord had somehow touched their hearts. That was that. No more disciplinary council. No more contention.

This experience reminds me of those peaceful years after Christ’s visit to the Nephites: “There was no contention in the land, because of the love of God which did dwell in the hearts of the people” (4 Nephi 1:15). It was Christ himself, personally, who had touched and taught those people and their children so profoundly. In Nephi’s words, they knew firsthand to what “source” they should look—not only for a remission of their sins, but also to find “that life which is in Christ” (2 Nephi 25:26–27)—as opposed to “the deadness of the law” of Moses with its emphasis on an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.

Can you imagine how many marriages, how many families, how many personal relationships could—and can—be healed by finding this form of “life”? The Savior said, “I am the resurrection, and the life” (John 11:25). This Easter, I bow in gratitude not only for the physical resurrection but also for that new life of charity that is found through Christ Jesus.

How do we access that sacred power? I don’t want to minimize the complexities and entanglements that confound the personal relationships all around us—including, sometimes, our own. I am not talking about just shouting a cliché or waving a magic wand. Our personal entanglements usually don’t happen all at once, and usually we can disentangle them—like tangled fishing lines—only one knot and one loop at a time, prayerfully and patiently calling on all of the forbearance, self-discipline, and love we can muster. We often, even typically, need to examine intractable human problems with every conceivable resource—logically, spiritually, psychologically, financially, and otherwise.

Yet there is also a deeper resource, known and available to the Saints of the Most High—and to their children—if they have been diligently taught to know Christ. I believe it was the spiritual gift of charity that descended upon the first man in that story. That resource, that grace, is not some autonomous wellspring in the sky but is, rather, the spiritual power that flows from our Atonement-based relationship with the Savior, much of it coming through the instrumentality of the Holy Ghost. And on what condition? Moroni said God bestows charity “upon all who are true followers of his Son” (Moroni 7:48).

How did charity break through the barriers between those two men, helping their hearts to change so completely? I don’t know firsthand. But I believe that, first, the Lord didn’t simply zap them against their will—or as if they had no will. That might be Luther’s interpretation. But no, through the promptings of the Holy Ghost, the Lord offered his hand and his charity. The first man recognized it and took it, and the second man responded in kind. They both “yield[ed] to the enticings of the Holy Spirit, and [put] off the natural man” (Mosiah 3:19).

Second, I believe these men were both able to respond as they did because they had previously been taught diligently to what source they should look—to forgive, to be forgiven, and to grasp that life which is in Christ. Like Enos in the forest or young Alma on the earth, in the pivotal moment when these two men had spent their fury, they remembered what their parents (or their missionaries) had taught them about the teachings of Jesus.

Minerva Teichert, Christ with Children.

Minerva Teichert, Christ with Children.

Third, we can satisfy the conditions of grace in the midst of our weaknesses; even because of a weakness, when we choose to give it up, with his help, and turn to him. The Lord graciously bestows the gifts of the Spirit “for the benefit of those who love me and keep all my commandments, and him that seeketh so to do” (Doctrine and Covenants 46:9; emphasis added).

On a recent family handcart “trek” visit to Wyoming, we noted that most historians believe the decisions of the Martin and Willie companies to begin their handcart journeys so late in the year was an ill-advised mistake. But, after a group vote, that was their choice. So I asked our family members, did we come to Martin’s Cove to celebrate a mistake? One of our grandchildren raised a hand and said, “We all make mistakes, sometimes dumb ones. We’re here to honor and to learn from those people and their rescuers because of their faith and sacrifice to overcome the effects of their mistakes. Knowing that the Lord helps us do that means more to me than if he only helps us when we’re perfect.” Saved by grace, after—and during—all we can do.

BYU students in the light. Courtesy of BYU Photo

BYU students in the light. Courtesy of BYU Photo

Let’s look again at the relief sculpture on this building—and its message about the grace that is bestowed on those who teach and learn diligently, whether as students or parents. Once our granddaughter Sarah Anne, then about four years old, was walking across a crowded BYU campus with her aunt, also named Sarah, who was then a BYU student. (Notice the streams of light on the BYU students in the nearby image—streaming symbols of grace.) When the carillon bell tower chimed the top of the hour, most of the students on the quad scurried quickly to their next class, leaving the two Sarahs to walk almost alone.

As little Sarah saw all those students scattering into the surrounding buildings, she looked up and asked her aunt in childlike wonder, “Are the BYU students all going into those buildings so they can learn about the temple?” That was a young child’s instinct about BYU’s core purpose—probably her take on whatever her parents, both BYU graduates, had taught her. And she was pretty close. Both for now and for the future, “Teach ye diligently and my grace shall attend you,” bringing love and delight into our lives and the lives of our posterity.

Notes

[1] Cambridge English Dictionary (online edition).

[2] Oxford English Dictionary (online edition).

[3] Carl Mosser, “And the Saints Go Marching On: The New Mormon Challenge for World Missions, Apologetics, and Theology,” chapter 2 in The New Mormon Challenge, ed. Francis J. Beckwith, Carl Mosser, and Paul Owen (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2002).

[4] For additional commentary on how Restoration theology about grace and Christ’s Atonement differs from Protestant and Catholic doctrine, see Bruce C. Hafen and Marie K. Hafen, The Contrite Spirit: How the Temple Helps Us Apply Christ’s Atonement (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), chapters 1–5.

[5] For a more complete account of this story, including Agnes Caldwell’s journal, see Hafen and Hafen, Contrite Spirit, 22–23.

[6] Orson F. Whitney, Life of Heber C. Kimball (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1967), 450.

[7] Email from Sarah d’Evegnee to Bruce C. Hafen, 19 July 2018.

[8] President Russell M. Nelson, “Becoming Exemplary Latter-day Saints,” Ensign, November 2018, 113.

[9] I thank Charles Swift for this insight.