On the Western Frontier

Donald G. Godfrey, "On the Western Frontier," in In Their Footsteps: Mormon Pioneers of Faith (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 101–128.

It had been the hope of the earliest English settlers in New England that they could establish “a virtual theocratic state, governed by a Calvinist clergy.”[1] This idea of an absolute religious theocracy was hotly contested by those with a more liberal interpretation of doctrine whose ideas allowed complete freedom of religion. It was within this atmosphere, “a cauldron of religious excitement,” that Mormonism and the Card families fostered their American beginnings.[2] For generations, the Card ancestors lived in New England. They were among the English settlers who had arrived in the New World during the early 1600s. They were spirited independents, farmers, and crafts people. These were challenging and changing times. William Card (1722–85) served in the Continental Army. The family experienced the onslaught of the wars and the turmoil that created a nation as they raised their families. Elisha Card (1738–90) was a Revolutionary War veteran.[3] William Fuller Card (1787–1846) served the American Armed Forces in the War of 1812 as a lieutenant in “Captain Bell’s [Campbell] Company of the New York Militia.” Cyrus William Card’s (1814–1900) family coped with the conflicts that would lead to the American Civil War (1861–65). William, and his wife Sarah Sabin Card (1793–1864), along with Cyrus W. and his wife Sarah Ann, were the first Cards to join the LDS Church.[4] In the South, slavery provided the labor force for the flourishing cotton industry. The debate over slavery was intense and would eventually result in the Civil War. At the same time, the Mormons were pouring into the Great Salt Lake Basin. Most of them were Northerners, including the Cards, who advocated for an end to slavery. Charles Ora Card (1839–1906) was yet in his youth.

The Card ancestors were among those common pioneers who forged the nation. They experienced economic and cultural revolutions that engulfed the United States. Following the Civil War, they witnessed the Industrial Revolution of the 1800s which fostered new factories in the East, increasing employment and urbanization. Railroads were just beginning to interconnect the eastern seaboard cities to coal, lumber, mining, and industrial interests. Individuals, families, and groups began migrating in great distances and numbers. News of the times came to rural America and Canada from travelers, touring politicians, preachers, and performers who traveled the Chautauqua circuits. The traveling speakers spoke at community congregations and gatherings, sharing stories about religious revivals, philosophy, and politics. Sometimes their speeches were simply a form of entertainment. Many travelers’ names are known today: Ralph Waldo Emerson, William Ellery Channing, Lyman Beecher, John Calhoun, and Daniel Webster. They spoke of ideological disputations and struggles that when resolved formed the fundamentals of our nation. The frontier newspapers often published letters from travelers. The idea of professional journalists was still on the horizon. On 13 July 1859, a young New York Tribune reporter Horace Greeley was granted a two-hour interview with Brigham Young.[5] The article appeared 20 August 1859 and was simply an abbreviated transcript of the interview.[6] Some forty years later, colonizer Charles Ora Card used the frontier newspapers to recruit settlers to Canada. In the newspapers, readers generally learned about distant places simply from people who were writing home.[7]

Early Wheelmen

Cyrus William Card was born at Painted Post, Steuben County, New York, about seventy-five miles south of Rochester and Palmyra, and just under three hundred miles northwest of New York City. This is where his son, Charles, spent his earliest years. The family home was in Ossian, where the Canaseraga and Sugar Creeks converged. It was a mostly rural countryside, with picturesque rolling green hills and forests at the edge of the Allegheny Mountains just north of the Pennsylvania line. It was a rich agricultural land. The Cards were fairly affluent settlers, skilled craftsman, and well-educated people for their day. Cyrus spent eight to ten years of his young adult life learning the trades of a wheelwright. A wheelwright was a skilled craftsman who specialized in wagon wheels. He built several wood mills within the Caesarea and Sugar Creek areas. This eventually led him into the lumber industry.

In adulthood, Cyrus was a man on the go. He believed that order was the first law of heaven and the home. His tool sheds, home, and even outhouse were so clean and well organized that “he could find anything in the dark,” because he knew where it was, and he expected the same of his family. His neighbors brought wagons of all kinds to his workbench, including “a little red wagon,” sleds, and carriages, because they knew they could find the missing part and get things fixed.[8] Women brought him milk pans to solder, wooden barrels rims to tighten, and barrels to convert to water troughs for the animals. Cyrus never left home without taking a shovel. He wanted to be prepared, if needed, to fill a chuckhole in the road or repair an irrigation ditch that might be flooded. His garden and their small farm supplemented his wheelwright services and provided food for his family.

Cyrus and his wife, Sarah Tuttle (1819–94), were married in 1837. They had five children: Abigail Jane, who lived only a few short years (1837–41); Charles Ora, the second child and first son (1839–1906); Polly Caroline (1841–56), who would die while crossing the Plains; Matilda Francis (1852–75); and Sarah Angeline (1854–71). Sarah Tuttle complemented her husband’s work ethic and generosity. She was the “typical New England mother. . . . Their home was almost like a hotel.”[9] People coming and going were always welcome and well fed. To her school children, she was known as “auntie.” Her cookie jar was always full.

The family was baptized into the LDS Church on 12 April 1843 by William Hyde in Canaersaga Creek, near Whitney’s Crossing in the township of Burnes, Allegheny County, New York. Charles was baptized by his uncle Joseph Francis. They became part of the New York Ossian East Branch of the Mormon Church.[10] Cyrus’s father, William Fuller Card, died three years later. Even before his death, William and his wife, Sarah Ann Sabin, had buried five of their eleven children and four more would eventually die, leaving only Cyrus and his younger sister Sarah. Cyrus moved his family to Park Center, Michigan, where they cared for his mother and several younger children who were seriously ill. He was there to arrange his father’s affairs. The sadness, depression, and agony were likely challenging. Cyrus’s family were in Michigan for five years, 1847–51, during which young Charles attended school.[11] They returned to New York to recuperate and make preparations for the long journey to the Salt Lake Valley to be with the Saints who gathered there.

Back in New York, the family settled at Whitney’s Crossing in the township of Burnes, close to their first home. Charles and his younger sister Polly continued in school until April 1856. Finally, preparations were complete and they started for the Salt Lake Valley. Within days of Charles’s baptism, they were on their way.[12]

Life and Death Trekking West

It was at this time that the first handcarts were authorized by Brigham Young as a new and improved means of moving people across the country. The handcarts were an inexpensive solution compared to the more expensive oxen-drawn covered wagons. The handcarts were intended for traveling light and increasing the flow of people. They were fashioned after the fruit and vegetable peddlers’ wagons common in larger eastern cities, designed to be pulled from location to location without the need for livestock. Each cart carried minimal provisions for about four to five people.[13] One wagon per twenty handcarts was assigned to carry heavier provisions. Each person was allowed seventeen pounds of belongings. This included cooking utensils, bedding, and personal items such as clothing. If the carts were overweight or people had additional luggage, it went into a wagon, and they were charged extra. If the traveler could not afford the extra freight charges, their materials were abandoned. The handcart pioneers all walked across the plains pulling their carts loaded with whatever they could afford.[14]

The Cyrus Card family traveled with the Edmund L. Ellsworth company. Their little group included Cyrus (42), Sarah (37), and children Charles (16), Polly (14), Matilda (3), and Sarah (2), along with Grandmother Sarah Ann Tuttle Card and uncle Joseph Francis.[15] By 15 April 1856, the family took the first steps of their journey. The first leg was via train from New York State to Iowa City, Iowa, where they joined others in the main group of their handcart company. The Cards enjoyed two advantages: Cyrus’s wheelwright experience and their two wagons.[16]

The company set out 9 June 1856. There were 52 wagons and 275 people. Progress crept forward slowly and was filled with individual challenge. Handcarts and wagons were in constant need of repair. One can safely assume that Cyrus was at the center of those repairs. Finding drinking water was tricky and at times water they could find was unpleasant to swallow. Rain captured in prairie buffalo wallows provided some welcomed yet nasty relief. [17] At one point, Cyrus was so desperate that he dug out a spring to reach fresh water. The company stopped routinely at a stream at least every ten days to fill their water barrels.

Young Charles took his turn in adult chores. If wood was unavailable for the evening fires, he gathered buffalo chips. The dried buffalo dung might have smelled a bit, but it was fuel sufficient for cooking. He stood guard at night. He joined the hunters who scouted for buffalo herds. Hunting was the major food source. Apparently, a few of the trek leaders were unkind to the foreigners from Italy. These new folks were unfamiliar with the herding of the domestic animals, hunting, and the ways of the West. As a consequence, they were blamed for slow progress and forced to walk more than others. Charles quietly smuggled women and children who were weak and tired aboard his father’s wagons to rest for a few miles. Crossing the strong rivers and gentle streams, Charles carried the women and children one at a time on his back. As one of the travelers wrote, “The captain was not too kind, but that Charles O. Card was a kind boy. . . . God bless that man. I love him for his kindness and I hope I will never forget his name.”[18] When Cyrus and Charles’s uncle took sick, it fell to Charles to care for their wagons and four yoke of oxen, as well as all the travel and camping chores. He was forced to grow up quickly.

One stormy night in July, almost two months into the journey, Charles’s sister Polly became ill. She had a fever, developed a bloody cough, and turned very pale. It was consumption.[19] She was only fourteen and died along the trail. Archer Walter, a traveler in the company, crafted a coffin for Polly. Cyrus paid him 50 cents ($13). Her “burrying [sic] ground [was] at the Town of Linden (I think).”[20] The family was distraught, but they carried on.

On 11 September, the company was surprised by a chance meeting with Apostle Parley P. Pratt and seventeen missionaries headed east for missions in Great Britain. Elder Pratt tried to address the travelers, but “observing that this was a new era in American as well as Church history . . . my utterance was choked, and I had to make a third try before I could overcome my emotions.” What Pratt saw was a crowd a few weeks away from their destination. “Their faces were sunburnt and lips parched; but cheerfulness reigned in every heart, and joy seemed to beam on every countenance.”[21] The chance meeting produced a joyous celebration, and the next day both groups continued on their way.

Eight miles east of Salt Lake, President Brigham Young and the Nauvoo Brass Band met the Ellsworth company. President Young rose to offer his welcome, but when he saw the hunger in the little ones’ faces, he simply said, “Come, let’s serve the food; speeches can wait.”[22] They ate and then were addressed by President Young and Ellsworth. “Never has a company been so highly honored . . . since Israel has arrived in these mountains, as the Pioneer handcart companies.”[23] They had walked 1,300 rugged miles.

Missions and the Man

Within a week, the families were attending the October general conference, where for the first time they listened to the authorities of the Church. It was a climactic celebration, after months of travel hardships, when they heard Brigham Young’s call for volunteers to travel back to Wyoming to assist the Willie and Martin Handcart Companies, which had set off late in the season and were tragically trapped in a severe winter snowstorm.[24]

Cyrus and his family first lived for three years in Farmington, a hamlet twelve miles north of Salt Lake City. In 1858 Charles was ordained to the office of a Seventy in the Church lay priesthood. He was now nineteen years old. He held that office for the next nineteen years.

In 1859, Cache Valley was being settled. Crops reported by the earliest pioneers had been plentiful, and President Young sent Apostles Orson Hyde and Ezra T. Benson to organize several communities. James Henry Martineau, a convert and surveyor, was creating city blocks with lots at 1.35 acres.[25] Cyrus and his son, Charles, traveled to Logan to stake out a homesite. Cyrus left Charles in Logan to build their first cabin. It would be a one-room structure among a small group of houses arranged like a fort for protection from the Shoshone natives and any interference from the federal government.[26] Within a year, Cyrus moved the whole family to the new settlement of Logan. There were soon one hundred homes in the rapidly growing Cache Valley.[27]

Cyrus sustained the family with a new business, the Card & Son Sawmill, Lath, and Shingle Mill. Cyrus and Charles were business partners. Logan and the lumber business did well. Their sawmill was essential to the valley’s homesteaders and the town. Between 1862 and 1880, Charles calculated he and his father had paid $2,480.90 or $137.82 per year tithing ($58,137 or $3,234).[28] Over this same time they purchased four three-quarter-acre building lots in the city and a thirty-five-acre farm.[29] They were not farmers as much as businessmen, but crops were planted, and gardens provided food for their families. This is how everyone was fed. The Cards acquired their raw lumber from the Green and Logan Canyons, although the Logan Canyon road extended only a few miles into the mountains.[30] Trees were harvested in early fall or late winter. The light snows made it easier for the teams to drag out the logs. They hauled them to the mill for sawing in preparation for construction and sale. Until 1875, their sawmill faced only one competitor, the F. N. Peterson & Sons Planing Mill.

In 1875, Cyrus and Charles supported the establishment of the United Order in Logan. The Card & Son Sawmill, Lath, and Shingle Mill and the P. N. Petersen & Sons Planing Mill merged under the new United Order Manufacturing and Building Company of the Logan Second Ward.[31] One year later it opened for business “with a paid-up capital of $10,410” ($221,368).[32] No matter how these finances were divided, the sum was significant.

The United Orders were established in Mormon communities from Utah to Mexico during the late 1800s. These cooperative enterprises were originally regarded as ideal for the development of individual independence while eliminating poverty. This was to be accomplished by having everyone deed all their personal property to the Church for redistribution according to individual stewards. The system was short-lived, but it did aid colonizers. It promoted self-sufficiency as everyone was expected to work and contribute. Most importantly, the United Order symbolized a more perfect society in which everyone worked supporting each other.[33] Cyrus and Charles were leaders in the Logan United Order. Charles became a member of the governing board. After the Card Sawmill went to the Order, Cyrus managed the mill that provided lumber for the town as well as the construction of the Logan Tabernacle and the temple.

Charles was a part of a loving family and had a deep respect for his father and his father’s families.[34] Cyrus instilled a desire for education, a respect for order, and a love for the Church. Cyrus died 4 September 1900, having nurtured his son’s deep-rooted foundation of faith.

Cache Valley Leadership

In maturity, Charles emerged as a prominent leader in Cache Valley. He was elected to the first Logan City Council (1866), at age twenty-seven, and served as a city councilman for sixteen years. As a member of the Logan City Council, he served on a special committee organized to curb the consumption of alcohol.[35] They were unsuccessful, but it was a colorful point of contention between members of the Church who wanted to be left alone and nonmembers who too had recognized the farming and business potential in the valley. Charles was appointed to the Board of Teacher Examiners and the Logan School Board. He worked as director of the Logan Irrigation Canal Company and was a road commissioner for almost three decades. This experience was invaluable when he later helped develop Alberta irrigation. In Logan, he was elected a county selectman with the assignment of regulating timber and water privileges. When the Logan Board of Education was created in 1872, he was elected to it and chosen as the chairman of the board of trustees for two years. In 1877, when Brigham Young College was founded, Charles was appointed to its board of trustees, in which he served for another twelve years.[36]

Charles was a strong proponent of education. He had attended schools in New York and Michigan. He attended business school in Ogden and taught school in Logan.[37] As a community and church leader, he spoke relentlessly, encouraging “the schooling of our children,” praising their capability for the “highest attainments.”[38] Charles taught school in the Logan First Ward meetinghouse. One of his pupils was his future wife, Sarah Jane Painter. One day, Sarah and her friends were tardy because they had been out picking wildflowers. The penalty was each one taking turns “standing on the block.” Sarah left for home after school crying, “I am never going back to that old Charley Card’s school anymore.” She apparently had forgotten the incident when they married nine years later.[39]

Charles’s daily life was an interwoven pattern of activities dedicated to his family, community, and religious service. He worked on any project he thought would improve his community. When the Church proceeded with construction of the Logan Tabernacle in 1873, he was asked to act as the building superintendent. In 1877, he was transferred from this project to a still more imposing religious edifice, the Logan Temple.[40] The cornerstone was laid 17 September 1877.[41] These building assignments involved establishing specialized mills, factories, rock quarries, and kilns along with roads to get the materials to the building sites. He solicited donations for buildings and maintained the accounting records along with recruiting and supervising workers and volunteer laborers.

The most important agricultural industry experience Charles drew from Cache Valley was irrigation, which he would use in Canada. Like Cache Valley—southern Alberta, Canada, was semiarid. Farming success was dependent upon drawing and controlling water from the mountains. In Utah, the Hyde Park, Smithfield, and Richmond canals were an immense complex, channeling water into Cache Valley through about thirty-two miles of ditches dug by hand and horse-drawn machinery. The water irrigated eleven thousand acres of farm land.[42] Card’s greatest accomplishment in Canada “was to oversee the construction of the Kimball-Lethbridge Canal [in Southern Alberta]. . . . This canal had 65 miles of channels, besides the natural waterways, irrigating about 200,000 acres of land.”[43] It brought homesteaders to southern Alberta—providing sustaining work, establishing settlements, and stimulating economic growth.

New England Mission

Like most Church leaders, Charles was called to serve a mission.[44] His New England Mission was comparatively brief. He was called and directed to revisit the states of his youth. He departed Saturday, 9 December 1871, taking with him a list of family and friends’ names as he headed out on foot.[45] His companion was William Hyde Jr., the son of the missionary who had converted the Cards. For four months, Charles and William traversed Wisconsin, Michigan, and New York. They walked the distance with food and rest provided by friends and people along the way. Anti-Mormon literature and polygamy issues preceded them. More than teaching converts, they “had the privilege of defending the cause of Celestial Marriage [polygamy]. . . and met with a little abuse.”[46] They were treated warmly when they introduced themselves as missionaries to a Baptist minister who immediately turned cold when he realized they were Latter-day Saints. Charles reported that generally, “religion was at a very low ebb in these parts, the majority of the people seeking after quick fortunes and it seems to the passer that everyone is trying to see who can make the most with the least labor and many don’t mind grinding the faces of the poor.”[47] This was a commentary both on conditions, as he saw them, as well as revealing his own work ethic.

Perhaps the most significant experience of Charles’s mission was his incidental meeting with a former non-Mormon neighbor of the Prophet Joseph Smith. It was in the midst of the anti-Mormon publishers and authors, such as Eber D. Howe’s Mormonism Unvailed (1834), attempting to tarnish the reputation of the Church and character of Joseph Smith, calling the members a lazy, shiftless, and poor people. Amidst the criticism, it is revealing that Card and Hyde encountered Mrs. Canfield Dickenson, who offered her own assessment. She “lived about two miles from the Smith family,” and she “gave us a very favorable account of Joseph Smith and his parents,” describing them as “farmers and industrious and neat and tidy about their house.”[48]

As the companions headed home in the green mountains of “old Mass,” Charles was walking among the laurel bushes where he selected a walking cane “as a natural curiosity to cary [sic] home to our distant Utah.”[49] He and his companion stripped the bark from the canes, varnished them, and carried them home.[50] Over time, the cane has become a priceless antique.

“Quorum of Wives”

Charles’s community and church responsibilities increased with his age and service. “He seemed to know the hearts of men and have a persuasive technique to draw the potential abilities from others.”[51] His service was continuous throughout his life, as was his service to his four wives and fifteen children. With the exception of his first wife, the remaining three worked together, loved one another, supported each other in their trials, and enjoyed a flow of communication among them. In August 1923, they were all seated together for Heber J. Grant’s dedication of the first Canadian temple.[52]

Sarah Jane Birdneau (1850–1926)

At age 28, on 17 October 1867, Charles married his first wife Sarah “Sallie” Jane Birdneau.[53] Sallie was the daughter of Nehemiah Birdneau, who was among the Cache Valley pioneers. Charles was already a partner in his sawmill business, a teacher, and a member of what would become the Logan School Board. The newlyweds’ first home was a one-room log cabin with a dirt floor, located right next door to his father’s residence. Four years later, their first child, a daughter, Sarah Jane Card, was born (1870–1930). She was affectionately called “Jennie.” She was eight months old when Charles was called to serve a mission in the eastern states. It might have seemed difficult, yet he and Sallie corresponded regularly, exchanging photographs and many letters during his mission.[54] Charles Ora Card Jr. was born six years later (1873–1930).

Over the next ten years, Charles built Sallie a frame home with wooden floors. As he evolved into an influential church and community leader, he was often called upon to defend the ideals of polygamy. At first Sarah shared the beliefs. In 1882, when she fell ill, he cleared his schedule for six days, never leaving her side. There was a love and caring “shown during these hectic . . . years.”[55] Sallie and children, Jennie and Charles Jr., traveled with him to his various business and Church assignments, but there was also mounting tension.

Unfortunately, Sallie was finding herself stretched between different worlds.[56] On 14 April 1879, while Charles was away, his father and her father entered her home and ejected a male visitor. The affair left Charles devastated with deep “feelings of anguish . . . seemingly more than I could bear.”[57] His heart would survive this first affair, but not the second, this time with one of Charles’s construction workers on the temple, Benjamin Ramsel. Ramsel had been Charles’s companion on numerous chores in temple construction. Charles had admired him for his outdoor skills. He had visited Charles’s home often—apparently too often. Charles felt betrayed. Defending herself in the affairs, Sallie became increasingly antagonistic, living in and out of Church norms. After the affair with Ramsel, she finally requested a divorce. Charles did not want a divorce. Sallie counseled with her father and Charles. She struggled with the implications of plural marriage. Sallie would repent, continue in the affair, get counseling, and repent again. It was a cycle that ended in heartache. Finally, the divorce was granted. Charles wrote, “I desire not a separation, but desire peace.”[58]

After the divorce, Charles built a separate residence for Sallie in Logan, but the custody of the children was given to Charles. Sallie would eventually marry Ramsel, and while Charles was in hiding from federal authorities, she persuaded the children to leave the Church and follow her ways. The two who suffered most from the divorce were the children. They would eventually move to Baker, Oregon, where they spent the rest of their lives.[59]

Sarah Jane Painter (1839–1936)

On 17 October 1876, Charles wed his second wife, Sarah Jane Painter. This was his first polygamous union. They would have six children: Matilda Francis (1878–79), George Cyrus (1880–1958), Lavantia Painter (1881–1937), Pearl Painter (1884–1965), Abigale Jane (1886–1939), and Franklin Almon (1892–1972). Sarah was eight years younger than Sallie, yet it was Sarah to whom Sallie went for counsel during her own conflicts with Charles.

Sarah Jane was the daughter of George Painter and Jane Herbert, long-time residents of Logan.[60] She was born 15 March 1858 in Bountiful, Utah, and passed away 9 February 1936. Her parents were a hardworking, no frills, traditional English family. George Painter supported this family by making brooms and selling them from his home along with managing a small coal business. As with all the pioneers, a modest farm kept the family fed. George taught his children a rigorous work ethic as they toiled at his side. Jane dried apples and made apple cider. The cider was often fermented to make a cider vinegar. All three products were used in the family and sold to neighbors. Sarah was a proficient bookkeeper. She managed the accounts of the family businesses, skills she would use in her own family. She attended the Logan First Ward School located on First North and Main Street where Charles Ora Card was her teacher. She remembered him in that role as a strict, “rather interesting gentleman.”[61]

Sarah would translate her English customs, skills, and heritage into her family with Charles. She managed their Logan farms and their own home while Charles was in exile and hiding from the marshals, then again while he was in Canada for sixteen years. She never spoke negatively about polygamy and in fact tried to encourage Sallie, who would have been considered the senior wife, to stay the course, repent, and hold true to the gospel.

Charles and Sarah’s home was a humble one, but it was always full of the smells of good cooking—such as homemade bread, red potatoes, and peas dipped in melted butter. “Well, it isn’t very much,” she would say, as family, visitors, and Church dignitaries surrounded her table, “but you are surely welcome.” Her English upbringing was apparent in her table manners, as she could eat her peas with even a knife without dropping a single one. After dinner, the children helped clear the table and clean the kitchen. Then they gathered around to listen as she told stories of pioneering and Indians. These stories were laden with gospel principles and her testimony.[62]

Sarah’s position was significant in the Card family. She became the de facto senior wife as she attempted to pull Sallie back into the fold. Her life revolved around her family and service. During Charles’s mission in Canada, she was alone. Persecution weighed on her, but she was faithful.[63] The wives were scattered. She remained in Logan, managing family and business affairs. She participated in the dedication of the Logan Temple and served as the Logan Relief Society president for decades. Following Charles’s death, Sarah would live the next thirty-six years as a widow with her five children.

Zina Young Williams (1850–1931)

Charles’s third wife, Zina Young Williams Card, was the daughter of Brigham Young and Zina Diantha Huntington. Charles and Zina were married 17 June 1884. They would have three children: Joseph Young Card (1885–1956), Zina Young (1888–1975), and Orson Rega Card (1891–1984). Their daughter Zina would later marry Hugh B. Brown. Their son Orson was the grandfather of Orson Scott Card, the famous science fiction writer. Their family was one of distinction.

Zina Young was an extraordinary woman. She was one of the eldest daughters of Brigham Young, a position which gave her prominence within the Church, as well as in Utah and later southern Alberta societies. She was among the earliest leaders of the Young Women’s Mutual Improvement Association and the first “Ladies Matron” at what would become Brigham Young University. It was at Brigham Young Academy that she met Charles. He had enrolled Charles Jr. and Jennie in the academy, and he had arranged visiting and counseling for them with Zina, the school’s matron, as they struggled with the divorce of their parents.[64]

Zina, who was not yet thirty, was one of the first women from the state of Utah working in the suffrage movement. This assignment gave her national recognition. She toured the eastern United States as an ambassador, meeting with President Rutherford B. Hayes, speaking before the United States Senate, and even interviewing with Senator George Franklin Edmunds, a sponsor of the antipolygamy legislation known as the Edmunds Act and Edmunds-Tucker Act.[65] In her day, she was an outspoken feminist and a spokesperson for her beliefs. As a part of the Mormon immigration into Alberta, she hosted a parade of curious Canadian dignitaries in her home.

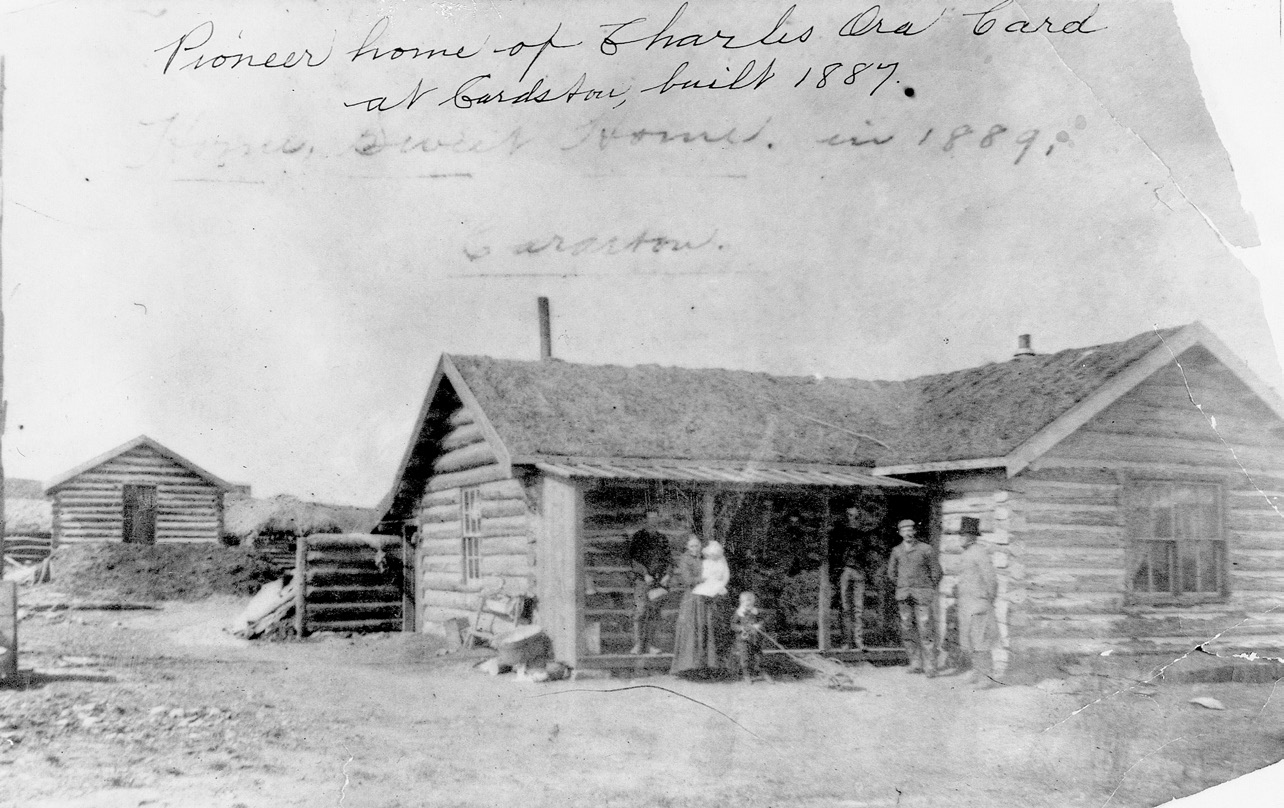

Pioneer home of Charles and Zina Card, 1887. Courtesy of Marilyn Ockey-Pitcher.

Pioneer home of Charles and Zina Card, 1887. Courtesy of Marilyn Ockey-Pitcher.

Zina was forced from the comfort of her Utah home in 1887 to escape the persecution she and Charles endured at the hands of the US marshals during the days of polygamy. They were forced into the Mormon Underground to avoid the US marshals.[66] Zina was among the first women to settle in southern Alberta. Apostle John Taylor singled out Zina as a major influence in the Canadian settlement: “Zina had a mission here [in Canada].” In southern Alberta literature, Charles is credited as founding the town of Cardston; and Zina was the settlement’s first lady.[67]

Lavinia Clark Rigby (1839–1960)

Lavinia Card married Charles on 2 December 1885.[68] She was his fourth wife. They had five children: Mary (born 1887), Lavinia (1890), Charles (1896), Sterling (1899), and William (1904).[69] She was the sixth daughter of William F. Rigby and Mary Clark Rigby, who would become pioneers in southern Idaho.

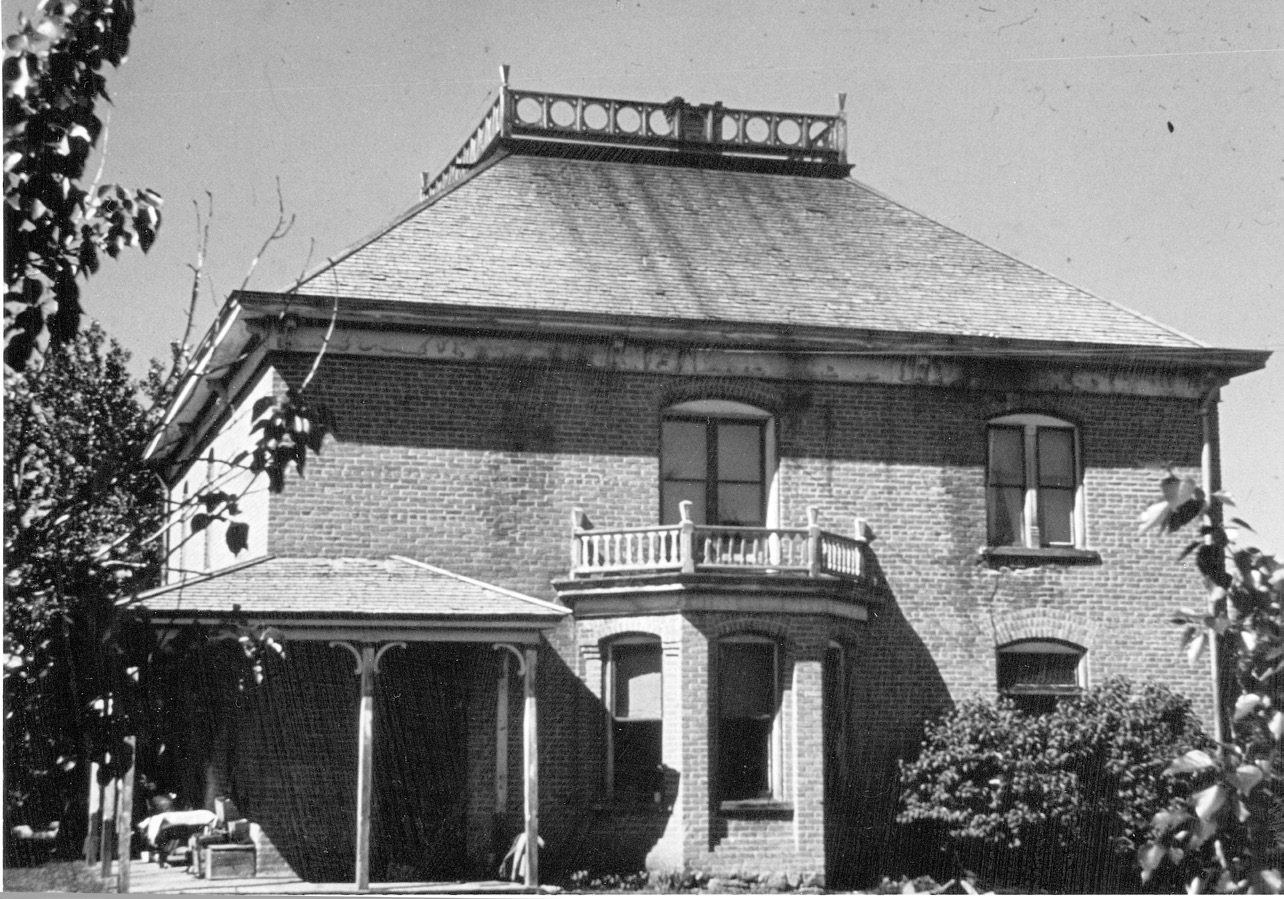

Brick home of Charles and Zina Card, circa 1903. Courtesy of Marilyn Ockey-Pitcher.

Brick home of Charles and Zina Card, circa 1903. Courtesy of Marilyn Ockey-Pitcher.

Lavinia lived and grew up in the Cache Valley. Her parents lived in their covered wagon as they moved about finally settling in Clarkston, where her father constructed a one-room log cabin with an attic. It was cold and cramped, but roomier and warmer than the wagon. In nearby Newton, their next home was to be a six-room log cabin. However, before they could occupy it, one of the workmen kicked wood shavings into the fireplace, and the house caught fire. Their entire home, furniture, and all personal belongings were reduced to ashes. William’s next home was larger than any in the vicinity, and here he often hosted local meetings and dances.

Lavinia wrote that her childhood days were happy. Entertainment meant making popcorn or molasses candy. The molasses was made from sugar cane raised on the farm. William read the scriptures to his children in a loud and spirited voice and laced his other stories with gospel principles. He had a good sense of humor. One day he gave the children the task of harvesting the peas in the field. When he returned, he asked how many they had picked. The dutiful children reported that they had “stepped it off” and found “all twelve acres were pulled.” This surprised their father because he had planted only one acre of peas. The children were caught in their ways and thereafter whenever William told his evening stories with hyperbole, he would end with “now that is ten acres of peas.”[70] The children got the message. After his stories, the evenings closed with a song. This nightly event took place in many pioneering homes after all the chores were done. It was their form of entertainment and social communication.

In 1879, when Lavinia was twelve, she was hired on as a cook for the loggers in Beaver Canyon. Beaver Canyon was east of Logan, into the mountains up Logan Canyon between Logan and Bear Lake.[71] She was taking on adult responsibilities. As she grew into teenage and dating years, she accompanied her father, who had the lumber contracts in the area, and for the next two years she helped support the family. They worked harvesting trees from the mountains and crops on the farm. They fought off the grasshoppers by digging a large hole in the field and covering it with a green cloth. The children then took long sticks and herded the hoppers onto the cloth. Then they dumped the critters into the hole and covered it with dirt. It taught the children good work habits, but the grasshoppers likely won the battle.[72]

With each year, Lavinia grew in her responsibilities, and she attended school. She was counselor in the Mutual Improvement Organization and taught a Sunday School class. At eighteen, she moved to Logan and entered the Brigham Young College. It was in 1885 that Charles proposed marriage. Lavinia was nineteen and Charles was forty-six. She had known Charles all of her life, and she was active and dating when Charles approached her. His proposal was a surprise. She counseled with her father and family who advised her to do what she thought was the right thing. She accepted. Zina helped make her wedding dress. Lavinia and Charles were married 2 December 1885.[73]

This marriage was a little different, as the federal marshals were now aggressively hunting for Charles.[74] In a letter to President John Taylor, Card notes, “They watch me so closely I have retired for the present to the mountains where I am writing this. They have spotters and detectives to work watching my houses as well as streets and roads.”[75] One of his secret hiding places was the Rigby home attic. Because of these conditions, Lavinia and Charles had a quiet temple wedding with a family gathering afterward for supper and celebration. Even moving around the valley with his new bride and meeting his other families invited disaster. Traveling must have been a frightening experience for young Lavinia. Charles often took other leaders with him and they hid out together. The persecution was increasingly severe. Lavinia hid in the woods alone, away from the marshals when they came looking. They wanted her to testify against Charles. Eventually, Charles purchased a home for her near Rexburg, and she lived there with their children away from the prowling federal authorities.[76]

Polygamy, Persecution, and Strength

Charles’s life was increasingly complex. In 1879, he became a member of the Logan Stake presidency, serving with Marriner W. Merrill as counselors to William B. Preston. He was still the superintendent of construction on the Logan Temple, along with all his other city and county offices. His diaries reflect extensive travels throughout the region from Bear Lake to Salt Lake, which must have felt like continual weeks of service. In 1884, William B. Preston was called to be the presiding bishop of the Church, and Charles was called as the new president of the Cache Valley Stake. This made him the presiding Church officer of the region. Again it increased his responsibilities, and this time it placed him higher on the list of primary targets in the eyes of the marshals.[77]

The passing of the Edmunds Act and Edmunds-Tucker Act disenfranchised Charles. Now, he was no longer allowed to vote, hold a public office, or serve on a jury. He was legally stripped of all his civic titles and responsibilities, which were given to the minority non-Mormons. Yet, the majority of the population, the Mormons, still depended on his leadership in every aspect of their lives. The acts aimed at eradicating polygamy sought to punish those engaging in “cohabitation.” It was directed specifically at the Mormon population and its leadership who engaged in the practice. Charles was among this group. He supported three wives. Following passage of these laws, Charles and many other Church leaders struggled in the conflicts over families, polygamy, and power that effectively divided Mormons and non-Mormons (“gentiles”), polarizing the territory. Families were forcibly divided. Charles’s own home was unsafe. The US Marshals wanted to put him on trial. As a result, he stayed with friends and relatives in what has been called the Mormon Underground. He hid in the attic of the Tabernacle and various rooms in the temple as well in Logan Canyon brush and timber. Yet, he still was concerned and responsible for the administration of Church-owned assets, now being transferred to local entities to avoid financial loss and federal takeovers.[78] He was constantly dealing with disruptions in local Church leadership, families, and his work. It was the increasing pressure of the 1882 and 1887 acts that forced Charles’s departure from Logan without even enough time to organize for his traveling.

Captured and Escaped

Persecution increased to the point that Charles and other Church leaders were afraid to go to their homes. They were afraid for their families. They administered their Church responsibilities as best as they could while in hiding. Charles was forced to move his wives and families. Families struggling to make a living were physically separated, and they scattered across the West. Some headed north to Montana to work in the mines and on the railroad. Others went to southern Arizona and the colonies of Mexico. Wives were alone. Single-parent family responsibilities were forced upon them. Husbands disappeared, then visited when they could and tried to provide some sustenance and support. Such was the environment in which Charles found himself. Something had to be done. Charles planned his escape. Sarah was to stay in Logan and manage his properties there, Zina would head into the Mormon Underground, and Lavinia was to move with Charles to Arizona. It was as good a plan as any. However, it was not to be.[79]

By midsummer 1886, Charles went into the Mormon Underground, which basically meant “keeping out of the way of the U.S. Deputy Marshals.” He knew they were watching for both him and Apostle Moses Thatcher, who also lived in Logan.[80] Charles was conducting the family business, mostly left to his father, and Church business as best he could.

Hiding out with a relative, he woke in the morning and was invited to breakfast, but he declined, preferring to be home with his wife Sarah Jane. So he went home, finding that breakfast had already been served. Even though Sarah had not been expecting him, she went about preparing an additional “cozy meal” while Charles went to the stable, greased his buggy, hitched up the horse, and drove to the front gate. He watched his stepson Sterling Williams pulling a load of hay from the field. Seeing his father, Sterling announced that they needed a pitch fork. So Charles drove into town, purchased a fork, and returned with it for his boys to unload the hay. He did not know if the marshals had seen him in town, so he took the extra precaution not to tie his horse.

He was half finished with his breakfast when Ben Garr and US Marshall E. W. Exum were at his back door.[81] As Charles walked toward them he was “impressed not to run.” The marshal drew his revolver and commanded Charles to stop. Charles “instantaneously almost and intuitively . . . reached for one I had in my hip pocket. . . . I did no more than place my hand upon my pocket, as we both knew the consequence.” Mr. Exum drew out a warrant from his pocket, and Charles was arrested.[82] He was taken to town, where he telegraphed Church headquarters to secure a bondsman. As the group moved about the community conducting business, Charles engaged his captors in conversation as to their unjust persecution against the polygamists. They went to dinner at the hotel and granted Charles his request to visit the bank, the telegraph office, and even accompanied him home to say goodbye to his wife Sarah.

Word had spread through town that morning and when the Charles and the marshals arrived at the train depot for the afternoon train, there was quite a crowd gathering about. Charles shook hands with everyone while the marshal obtained the tickets. As the party boarded the train with other passengers, the marshal and Charles got separated. The train started slowly, and Charles saw his escape opportunity. He jumped off the train to the ground looking for a horse or buggy. As it happened, a “young powerful horse” was on the east side of the street and Charles jumped on. The previous rider, however, was long legged, and Charles’s feet could not reach the stirrups. As a result he was bounced around in with one of the “roughest [rides] of his life.”[83]

Reportedly, the marshal demanded the train be stopped, but the conductor refused.[84] Charles hid out in the bushes and spent the night with friends. It was a dramatic experience.[85] It was a time that made it difficult to hold families and Church organizations together. Fathers and leaders were scattered. Charles was assisted by his counselor, Elder Orson Smith, in the stake presidency, and when Smith was targeted, he headed north and worked in building railroads in Montana.[86]

Onward and Northward

From a community, church, and family perspective, Cache Valley was a very successful settlement endeavor. It had achieved a blend of private and cooperative enterprise, educational institutions, varied agricultural operations, numerous local industries, and it had produced local leaders called to Church-wide positions. The Utah Journal noted that “no other Utah city matched the percentage of growth—24%.” This was Charles’s experience and his legacy until persecution intensified.[87]

Early in 1886, Charles met with the president of the Mormon Church, John Taylor. Knowing it would be a long time before he would be able to appear again publicly in Logan, Charles asked permission to leave Cache Valley with his family and migrate to Mexico. A number of other Mormons including Apostle Moses Thatcher, all in similar circumstances, were already making this trek. John Taylor surprised Charles, asking that he not go south but north to explore the British territory. Exploration and preparation for migration to Canada began 14 September 1886. Lavinia would move to her exiled father’s home in Idaho, away from the marshals, and Zina would go with Charles to Canada.[88]

Notes

[1] Wrage and Baskerville, American Forum, 75.

[2] Leonard J. Arrington and Davis Bitton, The Mormon Experience: A History of the Latter-day Saints (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 3–19.

[3]“The Story of Charles Ora Card,” handwritten notebook by Clarice Card Godfrey, Godfrey Family Papers. See also “Charles Ora Card,” Pearl Card Sloan Family Papers, BYU Archive (hereafter referred to as the Sloan Papers). In these two references, “Campbell” is also simply referred to as “Bell.”

[4] Notes from the family history files of Clarice Card Godfrey, reproduced in The Floyd Godfrey Family Organization News 1, no. 5 (May 1979), insert 10.

[5] Louis L. Snyder and Richard B. Morris, A Treasury of Great Reporting (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1962), 106–9.

[6] Snyder and Morris, A Treasury of Great Reporting, 107–9.

[7] Edwin Emery, The Press and America: An Interpretative History of Journalism (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1962), 213–44.

[8]“Charles Ora Card,” Sloan Papers.

[9]“Charles Ora Card,” Sloan Papers.

[10] William Hyde, in Davie Bitton, Guide to Mormon Diaries and Autobiographies (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1977), 170. Also, Andrew Jenson, “Charles Ora Card,” LDS Biographical Encyclopedia (Salt Lake City: Jenson Historical Company, 1901), 1:297. The records do not indicate how the Cards came in contact with a Mormon missionary.

[11] 19 January 1872, entry in The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Utah Years, 1871–1886, ed. Donald G. Godfrey and Kenneth W. Godfrey (Provo: Religious Studies Center, 2006), 19 January 1872. Card was in Michigan on a mission at the time of this entry.

[12] Jenson, “Charles Ora Card,” 297.

[13] Arrington and Bitton, The Mormon Experience, 133–34.

[14] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 156–60.

[15] Cyrus’s younger sister Sarah Lavantia Card was not listed with the traveling group, but she did make the trek at some time as she died and was buried in Logan.

[16] Cyrus left New York mid-April and would have arrived in Iowa within a few days. It is uncertain as to where they caught the train to Iowa. The handcart company did not leave Iowa until a month and a half later, 9 June. One wonders if Cyrus constructed the wagons for his family or if he had the finances to buy them from inheritance or his trade.

[17] A wallow was a naturally occurring shallow water hole found on the prairies. The water was often stagnant and filled with animal hair, skin oils, and debris.

[18] Notes from the family history files of Clarice Card Godfrey. Reproduced in The Floyd Godfrey Family Organization News 1, no. 5 (May 1979), 10.

[19] Diary of Ann Han Hickenlooper, 29 July 1856, https://

[20] Journal of John Oakley, journal excerpt 1856, June–August, https://

[21] Parley P. Pratt, Autobiography of Parley Parker Pratt (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1950), 434–35. Newell R. Walker, “They Walked 1,300 Miles,” Ensign, 44–49. Walker has this meeting on 18 September. Pratt records it as 11 September.

[22] Walker, “They Walked 1,300 Miles,” 48.

[23] Walker, “They Walked 1,300 Miles,” 49. The Cards are not listed in the newspaper as arriving with the immigrants. One record indicates they may have left the company at Fort Bridger. It is also possible that only the handcart pioneers were listed.

[24] Howard A. Christy, “Weather, Disaster and Responsibility: An Essay on the Willie and Martin Handcart Story,” BYU Studies 37, no. 1 (1997–98), 6–74.

[25] F. Ross Peterson, A History of Cache Country (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1997), 35–37. Also, Godfrey and McCarty, An Uncommon Common Pioneer, 148. Martineau’s surveys spanned several decades reaching from Logan and south to the Mexican Mormon colonies.

[26] See Chapter 15, “The ‘Invasion’ of Utah,” and Chapter 16, “Babylon Wars: Zion Grows,” in Leonard J. Arrington, Brigham Young: American Moses (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 251–302.

[27] Joel E. Ricks, “The First Settlements,” in History of a Valley, ed. Joel E. Ricks and Averett L. Cooley (Logan, UT: Deseret News Press, 1956), 43–47.

[28] Godfrey and Godfrey, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Utah Years, 1871–1886, 17 April 1880.

[29] James A. Hudson, Charles Ora Card: Pioneer and Colonizer (Cardston, AB, Canada: Hudson, 1963), 164.

[30] Ricks and Cooley, History of a Valley, 161.

[31] The LDS Church is organized geographically and by population within specific areas. A ward or branch consists of members living within a geographically defined area. A stake is the combination of multiple wards. In this way, the larger organization kept the emphasis on the local service as opposed to the megachurch concept.

[32] Leonard J. Arrington, Feramorz Y. Fox, and Dean L. May, Building The City of God: Community & Cooperation Among the Mormons (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 223. Also Ricks and Cooley, History of a Valley, 198.

[33] Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-Day Saints, 1830–1900, 330–33. See also L. Dwight Israelson, “United Orders,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 4:1493–95; Ricks and Cooley, History of a Valley, 198–99.

[34] Godfrey and Godfrey, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Utah Years, 1871–1886, 273f28. Also James A. Hudson, Charles Ora Card: Pioneer and Colonizer (Cardston: Hudson, 1963), 176–77. Cyrus entered into two polygamous marriages with sisters Emma Booth (in 1859) and Ann Booth (in 1861). The family records of Jo Anne Sloan Rogers and Marilyn Godfrey Ockey Pitcher all confirm the Tuttle and Booth marriages. Internet sources add a Nancy Campbell (1862) and a Sarabette Stone (1857), thus bringing Cyrus’s possible total number of wives to five. The sealing dates of the latter were 2003 and 1994 respectively. The Internet data on these last two wives are conflicting and undocumented.

[35] See Godfrey and Godfrey, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Utah Years, 1871–1886, 1 March 1883, also 10 July 1883 for activities.

[36]“Charles Ora Card Activities Timeline,” in The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Canadian Years, 1886–1903, ed. Donald G. Godfrey and Brigham Y. Card (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1993), xxxix.

[37] Hudson, Charles Ora Card, 297.

[38] Godfrey and Godfrey, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Utah Years,: 1871–1886, 17 April and 2 May 1881.

[39]“The Story of Charles Ora Card,” Godfrey Family Papers.

[40] Correspondence from John Taylor to Charles O. Card, 19 October 1877, CR 1 20, John Taylor Papers, Church History Library. Kenneth W. Godfrey, Logan, Utah: A One Hundred Fifty Year History (Logan, UT: Exemplar Press, 2010), 28

[41] Godfrey and Godfrey, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Utah Years, 1871–1886, 17 September 1877.

[42] Peterson, “History of Cache County,” 58–61. Also, Hudson, Charles Ora Card, 21.

[43] Hudson, Charles Ora Card, 21.

[44] The LDS Church has no paid ministry in missionary, local, and stake organizations. The work of the Church is accomplished through volunteer service. “Callings” or assignments come from Church leaders. Ludlow, 248–50.

[45] See Godfrey and Godfrey, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Utah Years, 1871–1886, 9 April 1872, 9 December 1891.

[46] See Godfrey and Godfrey, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Utah Years, 1871–1886, 25 February 1872.

[47]“Correspondence: Whitney’s Cross, Allegheny Country, N. Y. February 3, 1872,” Deseret News, 6 March 1872, 50.

[48] See Godfrey and Godfrey, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Utah Years, 1871–1886, 30 December 1871. The complete name and circumstance of Mrs. Dickenson is unknown in this writing.

[49] See Godfrey and Godfrey, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Utah Years, 1871–1886, 28 February 1872. A laurel is an aromatic evergreen shrub. The leaves are used in seasoning and the oil from them can be made into a salve for healing open wounds.

[50] This cane was handed down from Clarice Card Godfrey to her son Kenneth Floyd Godfrey, then to Donald G. Godfrey.

[51] Hudson, Charles Ora Card, 47.

[52] The best description of each wife is found in Brigham Y. Card, “Life Histories of the Wives of Charles Ora Card,” M270 L 7225, Church History Library. The life of Zina is detailed in Donald G. Godfrey, “Zina Presendia Young Williams Card: Brigham’s Daughter, Cardston’s First Lady,” Journal of Mormon History 23, no. 2 (Fall 1997), 107–27. Also, Bradley and Woodward, Four Zinas.

[53] The name Birdneau comes with several different spellings in history: Beirdneau, Birdeneau, and Birdno all refer to the same person or family. In this writing, the author selected the first spelling, as this is how it appears throughout Card’s diaries.

[54] Card, “Life Histories of the Wives of Charles Ora Card,” 2.

[55] Godfrey and Godfrey, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Utah Years, 1871–1886, 17 February and 5 June 1878. The diaries of this time are replete with these family outings and birthday celebrations. See Card, “Life Histories of the Wives of Charles Ora Card,” 3.

[56] See Godfrey and Godfrey, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Utah Years, 1871–1886, 17 June 1878.

[57] See Godfrey and Godfrey, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Utah Years, 1871–1886, 14 April 1879. Also, “The Story of Sarah Jane Beirdneau,” in Brigham Y. Card, “Life Histories of the Wives of Charles Ora Card,” 4.

[58] Godfrey and Godfrey, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Utah Years, 1871–1886, 18–21 March 1884.

[59] Sarah was buried in Baker, Oregon, in 1930, and Charles Jr. in Portland, Oregon, also 1930.

[60]“Sarah Jane Painter,” Life Histories of the Wives of Charles Ora Card, n. p.

[61]“Sarah Jane Painter,” Life Histories of the Wives of Charles Ora Card, n. p. Also, Kenneth W. Godfrey, Logan, Utah: One Hundred Fifty Year History, 44.

[62]“Sarah Jane Painter,” Life Histories of the Wives of Charles Ora Card, n. p.

[63]“Sarah Jane Painter,” Life Histories of the Wives of Charles Ora Card, n. p.

[64] At this time, Charles was in hiding, and in his forced absence, Sallie’s influence increased over her children. They would eventually leave the Brigham Young Academy in Provo and enroll in the Logan Protestant School. They then followed Sallie and her new husband to Oregon.

[65] Godfrey, “Zina Presendia Young Williams Card: Brigham’s Daughter, Cardston’s First Lady,” 114–15. Also, Bradley and Woodward, A Story of Mothers and Daughters on the Mormon Frontier, 349.

[66] Godfrey, “Zina Presendia Young Williams Card: Brigham’s Daughter, Cardston’s First Lady,” 118–21.

[67] Godfrey, “Zina Presendia Young Williams Card: Brigham’s Daughter, Cardston’s First Lady,” 124–27.

[68] There are two spellings for the name Lavinia in the family papers: Lavinia and LaVinia. Both are the same individual. See “History of Lavinia C. Card,” Life Histories of the Wives of Charles Ora Card, n. p.

[69] Death dates of Livinia Card’s children were footnotes in Brigham Y. Card’s, “Life Histories of the Wives of Charles Ora Card.” Alternate sources give conflicting dates.

[70]“History of Lavinia C. Rigby Card,” Life Histories of the Wives of Charles Ora Card, 3.

[71] Today Beaver Canyon is a ski resort. Peterson, History of Cache Country, 273.

[72] Lavinia Rigby Card, “Ingredients of the Happy Home Life of the Rigby Family,” Godfrey Family Papers. See also box 186, William F. Rigby Collection.

[73]“History of Lavinia C. Rigby Card,” Life Histories of the Wives of Charles Ora Card, 3–5.

[74] Godfrey and Godfrey, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Utah Years, 1871–1886, 565.

[75] Letter from Charles Ora Card to John Taylor, 15 August 1886. Reproduced in Godfrey and Godfrey, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Utah Years, 1871–1886, 570.

[76]“History of Lavinia C. Rigby Card,” Life Histories of the Wives of Charles Ora Card, 7.

[77] Godfrey and Godfrey, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Utah Years, 1871–1886, notes found on inside the cover of the diaries, 570, 8 October, 1900.

[78] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 362–63.

[79] See The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Utah Years, 1871–1886, 14 and 25 September 1886.

[80] Moses Thatcher was a leading businessman and Cache Valley Stake president from 1871 to 1879 when he was called to be a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. See Deseret News 1989–90 Church Almanac, 50. Also Ricks and Cooley, History of a Valley, 278–81.

[81] Ben Garr was a former member of the Church but was now part of the group hunting the Church leadership. The Garrs came to Cache Valley among the herders working some three thousand head of cattle and horses, of which two thousand head belonged to the Mormon Church. William Garr had been a town selectman in 1856. See Ricks and Cooley, History of a Valley, 29–31, 90.

[82] See Godfrey and Card, Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Canadian Years, 1886–1903, 24 July 1886.

[83] The horse belonged to Logan’s mayor Aaron Farr, who was arrested for leaving the horse at the depot. Card wrote the Utah Journal, denying any prearrangement with Farr and recounting again his impromptu decision to escape. The letter was also reprinted in the Deseret News, Wednesday, 17 November 1886. See Hudson, “Charles Ora Card: Pioneer and Colonizer,” 80–81.

[84] When Card learned that the conductor refused to stop the train is not known, except it must have been before 14 September 1886. The conductor himself recounted his refusal to stop the train as recorded in Card’s diary for 14 February 1890.

[85] Up to 14 September 1886, there were four arrests in Cache County according to the compilation of Professor Lowell Ben Bennion from Andrew Jenson’s Church Chronology (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1914). Apparently the two Wellsville arrests were not known to Andrew Jenson, whose record of arrests by years is 1884: 2; 1885: 2; 1886: 5 (or 7), C. O. Card’s being the first for that year; 1887: 15; 1888: 17; 1889: 6; 1890: 3; 1891: 4; and 1893: 1; all in Cache County—a total of 55 to 57 arrests.

[86] See Godfrey and Card, Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Canadian Years, 1886–1903, 6 August 1886. For the detailed story of his escape see Diaries of Charles Ora Card, 25 July–7 August 1886.

[87] The Utah Journal, 3 October 1888. See also Godfrey, Logan, Utah: A One Hundred Fifty Year History, 49–77.

[88] For correspondence from Charles Ora Card to John Taylor, see John Taylor Papers and the John Taylor Letterpress Copybooks, Church History Library.