Victorian England

Donald G. Godfrey, "Victorian England," in In Their Footsteps: Mormon Pioneers of Faith (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 3–34.

Four generations ago, in England’s Victorian Era, Queen Victoria reigned on the throne of Great Britain (1837–1901) and the British Empire covered the globe. It was an era of domestic peace, prosperity, economic and industrial growth, global migrations, and, at the same time, one of increased social awareness.[1] Prosperity contrasted with child labor in the factories and mines.[2] Charles Dickens, born in 1812, created fictional characters most picturesque of this era.[3] As a journalist, Dickens would later describe the Latter-day Saints boarding a ship to America. The Bristol Channel provided the primary thoroughfare for worldwide shipping and flowed from England’s second-largest port at Bristol to the Atlantic Ocean. Industry sprung up around the port as ships sailed the world, returning with a bounty of imported goods: tobacco, rum, cocoa, sugarcane, slaves, spices, and whale oil. Ships sailed in and out on the waterway’s extreme high tides until locks were installed in the Bristol Harbour, luring companies that had used the larger harbor at Liverpool.

In the Victorian Age, childhood was an experience dependent upon family status. The children of aristocrats enjoyed the new fortunes of the time, whereas childhood barely existed for those born to poor families. Youngsters were expected to work, and some children as young as age five were contributing to the livelihood of their family. They worked in the factories, in the mines, and on the farms twelve to sixteen hours a day in unimaginable conditions. They crawled under new manufacturing machinery into spaces too small for adult workers. They cleaned the residue from the machines and the floors so that the machinery could churn nonstop. It was dangerous work. There were no child-labor laws protecting them. Working children who were lucky undertook apprenticeships, leading to respectable trades and domestic service for the rich. The others were consigned to a lifetime of poverty.

This was the time within which young Joseph Godfrey grew into childhood. He was born circa 14 March 1800, forty miles south of Bristol and in the vicinity of North Petherton, Somerset, England—a village along the Bristol Channel, which separates Wales and southern England.[4] The fifteenth-century Church of St. Mary, North Petherton, remains today. Joseph’s family was poor, yet amidst his suffering, he broke free, learned the sailor’s trade, and traveled the world. He could easily have been one of Dickens’s children of the street had it not been for a kind, nameless sea captain.

An Abusive Childhood

Joseph was the son of William Godfrey and Margaret Barrows[5] and the fourth of five children. Little is known about his two older brothers (Richard and John) and sister (Jemima). But Joseph and his younger sister Fanny cared deeply for each other. Their mother, Margaret, was missing during much of Joseph’s childhood, leaving her children to struggle with their father.[6] Love and attention were absent from this single-parent home. William was a physically abusive alcoholic, so Joseph and Fanny were sent to live with their Aunt Caroline Trott. Although she likely lived in the vicinity, it is not known exactly where she lived or how long they lived with her, but their placement proved temporary, as their father wanted them home. He likely wanted them for what they could financially contribute to the household rather than out of love. Home life with their father was painful, and young Joseph suffered.[7]

One day, Joseph took a loaf of bread his father had tried to hide on a high shelf. He climbed up and retrieved it to feed Fanny, who was crying for food. Joseph found the bread, broke it open, and scratched out the center to share with his little sister. Joseph “felt so sorry for her that he had reportedly often stole bread, which his father had hidden.” When William returned from work intoxicated and discovered the bread gone, he tied Joseph’s hands above his head, hooked them onto a wall, and “flogged him long and hard . . . ., beating him until he was in a stupor.” A doctor was called in, and the boy was treated. Most family histories reflect only one incident, but there may have been more.[8]

Joseph was only eleven, but after the beating he gathered what few possessions he had and planned his escape.[9] His disappearance that first morning went unnoticed. By the next day, he had made his way to the Bristol docks. He hid in an empty barrel that was being loaded onto a whaling ship in preparation for its departure to the North Sea. Joseph’s hiding place made the barrel too heavy to be empty and just before they set sail, he was discovered by the ship’s first mate.

At the same time, his father, now searching the harbor streets, rushed to the wharf, yelling for his son.[10] On board, Joseph pleaded with the captain not to return him to his father and showed the captain the fresh wounds on his back. The captain listened. Calling out to William, the captain told him Joseph was leaving with them and that William would never again abuse his son.[11] As the ship left harbor, Joseph watched his father walking along the wharf. It must have been a difficult moment in both of their lives—an emotional assortment of love, fear, anger, agony, relief, and anticipation.

The captain was kindhearted, and over the years he raised Joseph as his own son. Working as a cabin boy, Joseph won the hearts of his shipmates and over many years learned the working trades of the seamen. It was years later before the ship returned to Bristol. Even then, Joseph made no attempt to contact his family. Once when the ship was in port, Joseph saw his father at a distance, but he chose not to reach out to him.[12]

Sailing the World

Joseph grew to maturity under the watchful eye of the captain and progressed through the ranks of a British sailor. It was the captain who taught him to read and write, “how to splice a rope, box the compass, and in fact how to be a good sailor.”[13] He sailed to the northernmost outposts of the Atlantic, hunting for whales in Eskimo country. This was not casual labor and could be quite dangerous, as evidenced by the sinking of the Essex in 1820 by a sperm whale. When the crew sighted a sperm whale, the sailors dispatched in small boats to harpoon the whale, tie it alongside the larger vessel, and begin the grisly process of cutting it into pieces. The pieces were boiled to extract the oil, which was then stored in barrels. Joseph’s responsibilities during the whale hunt are unknown, but he no doubt knew about the dangers of the profession.

Joseph sailed east around South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope and into the Indian Ocean. On another trip, he sailed west, around South America’s Cape Horn into the Pacific. These were trade ship voyages, carrying precious cargo from the foreign ports back to Britain. He sailed into the principal ports of the world, reportedly before the mast of the English seas for almost thirty years in the days when the sun never set on the British Empire.[14] During his life at sea, Joseph, as well as the ship, captain, and rest of the crew, was sequestered into the British Navy likely as a cargo vessel. Joseph reportedly told his family of the Battle of Trafalgar and the death of Lord Nelson.[15] However, the ship was primarily a hunting and cargo vessel. Trade and cargo ships paid much better than those sequestered into navy service.

As the captain aged, many of the ship’s crew thought Joseph would assume the helm. However, when the captain became seriously ill and died, Joseph’s fortunes changed dramatically. It was the rule of the sea that the first mate had the senior claim of the captain’s position. Conflict fostered talk of mutiny between those supporting the first mate and those supporting Joseph. Seeing the potential trouble, Joseph chose not to fight for the captain’s helm and prepared to depart the ship. The new captain grew jealous of the crew’s loyalty to Joseph and planned vengeance. As emotions escalated, the ship was making its way up the St. Lawrence River, between the Canadian territory of Quebec and the US New England states. They docked at Quebec for a time and then continued to Prescott, Ontario. Anchored off the shore, Joseph concluded that for his own safety he must leave the ship quickly.[16] So, with his staunch sea friend, George Coleman, the two started off.[17] They packed their belongings into their seaman’s chests, and as they were lowering them down into a small waiting row boat, the new captain and one of his supporters dropped an iron bar through the bottom of their row boat. All of their belongings sank into the harbor. Joseph and George struggled with the chests, but realizing that it was going to be impossible to save both property and their lives, they dropped the chests, stripped off their coats and shoes, and swam for shore. They were without hats, coats, shoes, or any of the resources they had saved over the years and stashed away in the now sinking cases. They had nothing to show for their time at sea except each other, experience, and their invincible will.[18] Supporting themselves, they traded in their sea legs for those of the laborer, the militiaman, and the farmer for the next six years.

Joseph was now thirty-six years old.[19] Most of his life had been at sea. He and George’s first land travels took them over the St. Lawrence River from Prescott, Ontario, to Waterton, New York, where they worked through the winter of 1836. In the spring of 1837, they boarded a steamboat across the Great Lakes to Detroit, Michigan, and worked on the Chicago Canal, which was to connect Lake Michigan with the Mississippi River.

Chicago was a rapidly growing city of approximately four thousand residents.[20] Joseph apparently “was not a lover of larger cities with their noise, and he was not too happy with the people on the canal construction crew.”[21] Joseph and George returned to Canada and were drafted into the Canadian militia. They served for two years and were discharged 1 June 1839, then volunteered for an additional year at Fort Malden, Ontario. This fort was a British defense military staging area, used during the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837–38. Here, as Canadian Loyalists, Joseph and George fought against the rebels on the Canadian frontier who supported Canadian separation from British control.

On 1 June 1840, they were discharged, and the duo made its way back to Johnson’s Creek in New York. They were transient workers who labored as farm hands in western New York and New Jersey. One of these jobs would change their lives; they were hired to work the farm of James and Eunice Manning Reeves.[22] James and Eunice were parents of two daughters—Ann Elizabeth Eliza, age twenty-two, and Mary, age twenty.[23] Little is known of their courtship, but in 1840, Joseph married Ann, and George married Mary. The couples eventually settled in Roseville, Warren County, Illinois, a small town some fifty miles east of Nauvoo, Illinois.

Newlyweds amidst Turmoil

In the mid-1800s, the United States was struggling within itself over issues of slavery, the unification of the states, territorial expansion, and religious turmoil. These topics provided a forum for political debates on the establishment of “a more perfect union,” as well as new religious sermons on liberalism as opposed to traditional orthodoxy.[24] This historical era opened the western frontier and ushered in the progressive growth of an industrial age.

The people’s voice was being heard, but not without conflict. Three million slaves who had provided stability to a cotton-based economy in the southern states were fighting for freedom. New states of Florida and Texas were added to the nation as the union began to split apart. Lincoln and Douglas debated for the presidency. The whole of New England seemed occupied with religious debates. The Fox Sisters “cracked their toes,” providing individual prophecies for those who would listen. “Peepers” scoured the New England states, hunting for lost Spanish gold. Ralph Waldo Emerson attacked the dogmatic rituals of the Calvinist doctrine. This was the environment in which The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was founded, causing even more religious controversy. This was the environment of our two newlywed couples—Joseph and Ann Godfrey, and George and Mary Coleman.[25]

Challenges of Early Mormon Life

Mormonism, or more properly The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), was blossoming in New England, and Joseph Smith, the Church’s founder, was nominated as a candidate for the US Presidency on 29 January 1844.[26] As Joseph Godfrey and George Coleman moved about with their new wives, working as farm laborers from New York to Illinois, in 1843 they encountered the Mormon missionaries. Joseph and Ann were baptized by H. Jacobs.[27] George and Mary followed Joseph and Ann and were baptized on 3 April 1843 by Archibald Montgomery.[28] By late 1844, the couples had moved from New York to Hancock County, Illinois, and later to Nauvoo. Not too surprisingly, they were now treated as outcasts by family and former associates who wanted nothing to do with them because they had joined the Mormon Church. The enemies of the Church were bitter, and persecutions became more and more severe as the Church’s numbers and political influence grew and polygamy began. Nevertheless, Joseph, George, and their wives worked their farms and persevered.[29]

It was a frighteningly wonderful yet challenging time to be alive. In Nauvoo, they were with the main body of the believers, Joseph having purchased farm land just outside of Nauvoo. In 1845, he was ordained a local Seventy in the Church by Benjamin L. Clapp and became acquainted with the Prophet Joseph Smith.[30] He served as one of Joseph’s bodyguards and worked on the Prophet’s farm. The challenge that Joseph and George faced when they arrived in Nauvoo was that the city was at the height of bitter persecution. Missouri governor Lilburn W. Boggs had issued his infamous extermination order to rid the state of the Mormons. The extermination order was titled “Executive Order 44, issued 27 October 1838,” for the specific purpose of the “extermination” of all Mormons.[31] Illinois governor Thomas Ford even visited the jailed Joseph Smith and promised protection; however, within days, a local militia group, the Carthage Greys, had attacked the jail and murdered the Prophet.[32]

In 1846, the Latter-day Saints began fleeing Nauvoo. Joseph and George left their homes and farms to the mobs and set off on a journey of unspeakable poverty and hardship. The trek would be 1,300 miles across the Mississippi River to the Great Basin of the Rocky Mountains. The Mormons had been promised they could stay in Nauvoo until spring, but the violence inflicted upon those remaining prohibited any delay. Joseph and George left with the Saints. There is nothing in source materials describing specific violence against Joseph or George; however, fear permeated the city, their leader Joseph Smith had just been murdered, and violent attacks were increasing in Nauvoo.[33]

In the middle of winter, on 4 February 1846, Joseph, George, and their families crossed the Missouri River on the ice, making their way to Iowa. They relocated on a farm a few miles south of Council Bluffs. Winter hardships took their toll on the immigrants in Council Bluffs and Winter Quarters. Within a year, the two families moved again, this time to Misquote Creek near Kaysville, Illinois, and found new land for farming. They remained for three years, until 1849, working and acquiring supplies and a wagon for their trek west. Both families were poor. They scrimped every morsel of food as they saved for the journey west. Joseph and Ann lost three of their four children to cholera: sons Albert and James, and a daughter, Eliza Jane. In George’s family, Mary came down with dysentery. By the time they began moving toward to the Rocky Mountains, they were two families among the “approximately 20,000 Mormons scattered on the prairies in a thin line . . . across the prairies.”[34]

Mormon Battalion

Persecution remained severe. It is an understatement that the pioneers were significantly surprised, angered, and in a state of disbelief when their brethren were recruited by the United States federal government to engage in the Mexican-American War (1846–48). US President James K. Polk had the vision of a coast-to-coast nation, his eyes focused specifically on California. At the same time the Saints, the homeless band of believers, were leaving United States territory with the hope of creating their own independent State of Deseret where they could worship and live free from persecution.[35] The State of Deseret, would never materialize, but this was the context of the time when in July 1846 the US government asked for Mormon recruits. Church President Brigham Young encouraged the members to assist, and at this suggestion, five hundred men enlisted in what became known as the Mormon Battalion. Joseph and George drew lots to determine who would go and who would remain and care for their families, assuring that they made it to Utah. The lot fell upon George, and he joined the battalion. Joseph promised his friend that he would care for George’s family until he returned, to which George responded, “And if I don’t come back, raise a family for me will you?”[36] Thus, Joseph was left to take charge of George’s family “as far as she [Mary] would let him.”[37]

The officers of George’s company (Company A of the US Army of the West) were Jefferson Hunt, captain; George W. Orman, first lieutenant; Lorenzo Clark, second lieutenant; William W. Williams, third lieutenant; and “Willis,” who later became captain. George was enlisted as a private in the company.[38] The battalion leaders were professional soldiers, not empathetic Mormon volunteers. Complaints from the Saints who joined the battalion chronicled verbal abuse, drunkenness, and the constant threat from the officers to leave the volunteers behind or give them extra duties if they failed to follow orders or simply fell sick.

George’s company arrived in Sante Fe, 1 December 1846, but despite both cold and hunger they were ordered to continue marching. Traveling usually ten to twelve miles per day, some did fall sick and indeed were left behind. By 8 December, snow was falling, and members of the company were finally able to purchase food and supplies using their own funds. George was so hungry that he overate and did not feel at all well during the night. Dr. William Rust, one of the company men, gave him “tincture of lobelia,” which was a nineteenth-century herbal aspirin and “it helped a little.” The next day, Captain Willis ordered the company off again. George was still feeling poorly, so he was left behind with only a saddle and a mule. The company arrived at Pueblo mid-January, but George did not. A search party was sent back, but to no avail. His body was later found near where Captain Willis had left him. “He died sometime mid-December 1846.”[39] It would be several years before his wife and Joseph would learn of his death.

George’s death would change Joseph’s life forever. The story of George Coleman in the battalion spawned early speculation and folklore contrary to fact. Did George abandon his family, his friend, and the Church? The answer to these questions is a definitive no.[40]

At the same time George marched with the battalion, Joseph, Ann, and Mary trekked toward Utah. They eagerly anticipated George’s return and were preparing for their own migration west. It took two years to earn sufficient funds to purchase a team of oxen and a wagon. The westward movement of the Mormons was organized into companies to better handle the growing number of converts. They operated under strict rules in terms of daily prayers, the care of their guns, guarding animals, and night-time circling of the wagons.[41] By 1852, Mary and George’s only son, Moroni, had joined the Orson Hyde company. Joseph and Ann followed with the sixth company, under the leadership of David Wood. The David Wood company included 288 individuals and 58 wagons.[42]

It was an arduous journey and many just walked alongside the wagons. The European immigrants were often unfamiliar with driving a team of oxen; thus progress was slow going and continually delayed. The cattle were herded along at the side of the wagon train as they drove. Night camps were highly organized; wagons were circled for protection, with the tongue of each wagon tucked under the rear of the one in front. Food was prepared for the evening meal and the next day’s journey. At night, the company entertained themselves by singing hymns of encouragement and dancing, putting their hardships behind them in preparation for the next day.

Forging the rivers was viewed as both a blessing and a challenge. It was a blessing because it provided the pioneers a place to stop, rest, and wash the blood from their feet; however, it could be challenging if the river’s currents were treacherous. Women and children were carried on the backs of the men. The wagon masters used the rivers to replenish their critical water supply. Water needed to be restocked at least every Saturday so that a proper Sabbath could be observed. The Sabbath was a day of worship even on the trail. The Wood company followed the Mormon Trail, arriving in the Great Basin in October 1852, just in time for the Church’s quarterly conference.

Joseph settled his family in North Ogden, Utah. Mary Coleman and her son, Moroni, unaware of George’s fate in the battalion, went to Tooele. They lived with her sister Matilda Bates and awaited George’s return. Mary was desperate to find George, so in 1853 she left Moroni and returned to search for her husband. Before she left, she encouraged Moroni to “try and get along with Mr. Bates,” whom she described “as a rough and harsh character.”[43] Then she headed back to the Mississippi and the area of the battalion’s departure to find some trace of George. She searched but returned without him.[44]

North Ogden: Dugout Living

Joseph’s first home in North Ogden was a dugout. The dugout was a simple, uncultured shelter, a temporary dwelling place for pioneers and frontiersman moving west. It was built by excavating the ground from the face of the side of a hill or by simply digging a hole into the ground. To call these homes simple is an understatement. They had dirt floors, dirt walls, and dirt ceilings. A rock or adobe fireplace provided warmth and heat for cooking. An animal hide covered the hole, which served as a door, and a cotton sheet on the opposite side of the dwelling sometimes covered another hole as a window and provided cross ventilation. Pioneer-styled air-conditioning for summer heat consisted of replacing the hide that covered the windows with burlap, which, when soaked with water, created a cool breeze through the structure.

Homes and lifestyles were basic by today’s standards. The pioneers ate what they raised on the farm and harvested from their gardens and from the wild. A cow, pig, and chickens provided protein, and sheep offered wool for clothing. The women worked both on the farm and in the home long before the term “working women” took on a political posture. They assisted in planting and harvesting, tended to the farm animals, and made all their own clothing—spinning wool from the sheep and making the yarn from which cloth was woven. Joseph’s daughter remembers “seeing her [mother] spin day after day walking [rocking] back and forth at the old spinning wheel,” making yarn for clothing from the sheep’s wool.[45] Joseph too had a hand in household affairs. He held to the stern discipline of a sea captain and was strict with his children and how they dressed. He allowed no extravagance or showiness, such as ruffles on his daughter’s clothing.[46]

The farm and large gardens yielded grain, hay, vegetables, fruit, calves, pigs, and chickens in a good year. There was little or no money. Purchases were made “in kind,” meaning goods of equal value were exchanged. If the harvest was poor, families went without and were at the mercy of others. The disadvantaged later became Joseph’s responsibility when he was called into the bishopric of the North Ogden First Ward and put in charge of caring for the needy.

Home Life in North Ogden

Joseph’s dugout soon became a food cellar when he purchased thirty-three adjacent acres and constructed his first home. Ann sold her priceless china for the land. The dugout became the cellar underneath the home, where food was stored. The Mountain Water Ditch, part of a hand-dug irrigation system, carried fresh spring water and snow runoff through the northern boundary of Joseph’s acreage.[47] The western border was along what today is 600 East, or Barrett’s Lane.[48] The south end is today’s 2100 North and was called by the locals Orton and Woodfield Lanes.[49] The eastern boundary today is the LDS Church building’s property line. There was a water well dug in the northeast corner of the acreage. A canal cut diagonally through the farm is where the children learned to swim in the summer. The soil above the canal was rich and ideal for growing onions and garden vegetables. The soil below the canal was used to grow hay for the farm animals.[50]

The new home was a two-story structure with a rock foundation and the dirt cellar for food storage. The walls were adobe brick, twelve inches thick, protecting the family from the cold of winter and the heat of summer. There was nothing in the way of luxuries, no built-in closets, no cupboards, no bathrooms. However, compared to the dugout, the house would have seemed like a palace.

Ben Lomond Mountain

Mount Ben Lomond to the north became the sentinel of North Ogden. Joseph’s children and North Ogden’s John Hall each credit Joseph as being the first to name the mountain, which was named after Scotland’s Mount Ben Lomond.[51] The North Ogden Ben Lomond looked so much like Scotland’s—which he had often seen as he sailed up the Firth of Clyde to the port of Glasgow, Scotland—that his continual reference gave the Utah mountain the same name.[52]

Mount Ben Lomond, to the north of Ogden, Utah. Photo by Steven Ford, www.Fordesign.net.

Mount Ben Lomond, to the north of Ogden, Utah. Photo by Steven Ford, www.Fordesign.net.

Church and Community Service

It was but a few years after Joseph had arrived in North Ogden that he was settled and fully involved in community and church service. Brigham Young visited North Ogden on 4 March 1853 and changed their small branch into a ward.[53] Thomas James Dunn was the bishop of the ward, and within a few years, Joseph Godfrey became a counselor.[54] Joseph’s responsibilities in the ward included caring for the poor. If families were unable to provide for themselves, the bishops’ storehouse was a foundation for help.[55] If specific materials were unavailable at the storehouse, Joseph would canvas the neighborhood until he found and acquired what was needed. He was a humanitarian, kind and understanding toward the poor, and always giving more than he took. He often cared for them personally with his own resources. Joseph knew how to dress a wound and set a broken bone. He became known as the “family doctor” for his neighbors and any who were sick, dispensing medical advice learned from his sea travels.

Joseph was an entertaining storyteller, and in the evenings he kept youngsters in the neighborhood and his family enthralled with stories of his adventures at sea and around the world. The far-flung places of the earth were fantasy to the young minds, but reality to him, and he enjoyed these times with the children. Many called him “Father” or “Daddy” Godfrey. He created a unity of purpose within the community. His unique experiences gave him talents that he employed in personal service to others.

Unity did not mean that life was easy. Winters could be severe, and the winters of 1854 and 1855 in North Ogden were particularly trying. From November until March, snow piled up three to four feet and drifted over the foliage and closed all roads.[56] Farm animals were weakened and died of exposure and lack of food. After the long, cold winter, grasshoppers and crickets ate the crops, leading to food scarcities. During such times, Joseph harvested native plants: thistles, sour docks, and sego lily bulbs to sustain his family.[57]

In good harvest years, food was grown in the summer and stored for the winter. Bounteous harvests produced cellars full of fresh fruits and vegetables. Nothing went to waste. Meats were cured and hung from the rafters, and summer vegetables were dried. There was little sugar, so Joseph created North Ogden’s second sugarcane mill, where he crushed the cane and boiled it to extract the liquid molasses. This was the only sweetener the family had for many years.[58]

Multiple Wives

During the 1850s, two more children were born to Joseph and Ann: Reuben (1854) and Matilda (1856); and then tragedy struck. Ann Eliza Reeves Godfrey died (just seventeen days after Matilda was born) on 16 January 1857.[59] Ann was the first woman buried in the North Ogden Cemetery.

Joseph was grief stricken and left alone with a household of four young sons and a new baby daughter. Mary, the wife of Joseph’s friend George Coleman, and her son, Moroni, were still in Tooele, Utah, and having a difficult time of their own. Mary had apparently been briefly engaged to a man named Tolman, until they separated due to Mary’s melancholy over the prospects of a plural marriage and living in Tooele. When she heard Ann Eliza had died, she left to help her sister’s bereaved husband and his family.[60] It is possible that Mary learned of George’s death through the North Ogden’s bishop, Thomas Dunn. Dunn was a member of the Mormon Battalion for two-and-a-half years and came to North Ogden in 1851. Shortly after Mary came to North Ogden, Joseph proposed marriage. He was fifty-seven, Mary was thirty-seven, and Moroni was fourteen when they reunited in North Ogden.

Joseph also sought to hire temporary help. He approached the neighboring Jeremiah Price family and asked if their daughter Ann could assist with his children. But Ann was engaged to be married and thus occupied in her own life, so she sent her fifteen-year-old sister, Sarah Ann, to care for Joseph’s children and handle household chores. The wedding day, 7 March 1857, was an unusual day. After counseling with President Brigham Young—who had initially been hesitant to encourage Joseph to take more than one wife, until changing his position for some unknown reason—Joseph married both Mary and Sarah Ann. The marriages were performed by President Young in his Salt Lake City office. Despite her previous aversion to polygamy, Mary was now in a polygamous marriage. Mary and Joseph would have four children of their own, while Sarah and Joseph’s first child was born in 1860, and eight more would follow. With everyone living in one house, it was a tight fit.

In 1868, Mary and her sister Matilda received word that their brother John died and left them each an inheritance. So the sisters left Utah and headed back East for the inheritance. Mary received $5,000 ($123,335 in today’s money), which must have seemed like a fortune.[61] Mary used the money to purchase a “rock house with two lovely big bedrooms” and moved close by Joseph and Sarah’s home.[62] She later moved with Moroni and her other children to Park Valley in northern Utah, near the Idaho border. Abundant grasslands in the area attracted the early settlers, including Joseph and several North Ogden families who owned land in the area.[63]

War: American Indians and the Church

The Utah War from 1857 to 1858 was a trying time. The proximity of the Army under Colonel Albert S. Johnston prompted a temporary evacuation of North Ogden. Some residents moved to the mountain canyons, others moved south to Provo, and the few that remained in the city prepared to “torch the town,” thus robbing the army of food and sustenance.[64] The political pressures against the Church and the practice of polygamy were growing and began to affect the daily lives of Mormon families. President James Buchanan sent the U.S. Army to control the Mormons, who began preparing to defend against the army’s invasion.[65] It was a turbulent time for the Saints in Utah, but a “free and full pardon” was eventually extended by Buchanan and peace was restored.[66]

The relationship between North Ogden residents and Native Americans had its ups and downs. The Shoshone Indians were persistent in begging for food and often commandeered calves or food from the pioneers. One native youngster, caught stealing food, was whipped by a settler, and Joseph was called in to settle the delicate and potentially dangerous conflict. He offered the tribe fruit, meat, and a variety of vegetables, thereby defusing the contention. Afterward, the natives began calling upon him regularly, but their visits made Joseph’s children nervous. One described “three large Indians that often came to our home to eat and talk with my father following him as he went about his work ‘till he could hardly work.”[67]

North Ogden was a long way from Church headquarters, even by horse and buggy, so settlers were encouraged by Church authorities to build a fort to protect themselves against the Indians. The North Ogden “fort” was approximately seventy acres surrounded by a rock wall six to eight feet high. The fort was to be constructed within the boundaries of the North Ogden First Ward. However, as hostilities between the Saints and the natives decreased, plans for the fort were abandoned.[68]

Notwithstanding the pioneers’ hardships, the Church members of North Ogden formed a united community. During the winters, they gathered in the school house for Church services, dances, spelling bees, plays, and debates. The debates featured rhetorical questions: Which has the greatest influence over man—women or money? Who had been treated more cruelly—“the Indians or the Negro?”[69] Which gives life the most pleasure—the pursuit or the possession? All North Ogden’s fun and trials were set within a spiritual perspective. The settlers of the valley, including Joseph’s family, shared one common bond—the Church.

Joseph had been the first of his family to join the Mormon faith. In his later years, it was reported that “he went back to England at one time to try and get his family to come to America.” His brother and sisters were married and settled, and Joseph was reportedly “not well received by them.”[70]

Joseph eventually had twenty-one children, of which six died and fifteen grew to maturity. The children who lived had the same pioneering spirit as their father. All of them moved from North Ogden, scattering throughout the West into Idaho, Montana, and Alberta. Ann Eliza’s children moved to Montana, and Mary’s and Sarah’s children went to Idaho and Alberta.

The Man Joseph Godfrey

The man Joseph Godfrey can be characterized as a world sailor, a humanitarian, and an individual dedicated to the gospel. Joseph, once an abused runaway child, grew in experience and in stature as he learned the skills of a sailor, becoming a man of love and caring. He stood only five feet seven inches tall, weighing about 150 pounds. One can only assume that he would have been mostly muscle given his labor at sea and on land. His eyes were blue, and he had light brown hair, which was never combed. His face was rugged, with a heavy jaw line that reflected firmness and discipline. He read without glasses and had almost a full set of teeth even at age eighty. He knew the world of his day more extensively than his associates did—he had sailed around it.

Sketch of Joseph Godfrey (1800–1880). Courtesy of North Ogden Historical Museum.

Sketch of Joseph Godfrey (1800–1880). Courtesy of North Ogden Historical Museum.

Joseph was a community humanitarian and a member of the North Ogden bishopric, given the charge to care for the poor. It was said, “He could go into a group and pass a hat around, and the people would freely contribute, without saying a word or asking what or for whom it was for, all knowing that someone, whom he [Joseph] did not care to mention, was in need of help.”[71] If there was a need, he was first to give. He gave away his blacksmith and carpentry tools to young settlers. He created peace with the Indians; he believed it was better to feed and befriend them than to fight. The Indians sought him out, calling him “Emigary,” a native word meaning friend or peacemaker.[72] He was a sexton that cared for the aging and, when necessary, performed the responsibilities of undertaker. He was often asked to speak at the funerals of those whom he loved.[73]

Nowhere was his humanitarianism reflected more than in his family. He did not seek the responsibilities of plural marriage. His marriage to Mary Reeves, his sister-in-law, helped them both through difficult times. His marriage to Sarah Ann Price was at the suggestion of Brigham Young to ease the Price family’s and Joseph’s own difficulties. Sarah now had a home of her own and was no longer a dependent. To ease Sarah’s labors, Joseph bought her a Singer sewing machine, one of the first in North Ogden. Joseph’s family reflected the life of the times and the challenges of the pioneers.

Spiritual peace was in their hearts, but the physical trials of pioneering filled their daily lives. After Joseph’s first wife, Ann, had died, Sarah was the only wife that lived in his house, as Mary owned her own home. Joseph would die prior to the Edmunds Act of 1882, but they had joined the Church at a time when persecutions against polygamous Mormons were growing. He and Ann had been driven from their home in Nauvoo in the middle of winter and lost children from resulting illnesses, but they never lost their faith.

On his eightieth birthday, his neighbors gave him a surprise party. It was a community and family picnic at his home and supplied “everything to make the heart glad.” Thomas B. Helm, master of ceremonies, called the gathering to order, and after much singing and food, Joseph was asked to say a few words.[74] “He gave a brief history of his life, commencing with his early boyhood and the circumstances of his joining the church some forty years ago; his association with the Prophet Joseph [Smith]; the mobs; his starting to Carthage with the Prophet Joseph; his journey to Utah, and its early settlement.” It was a fitting tribute to a local leader. “May Father Godfrey live to see many more such occasions,” said the host.[75]

Joseph was healthy, but while husking corn sometime in the late fall, he felt a sudden chill. He developed pneumonia and in a weakening state suffered a stroke. He died 16 December 1880. He was eighty years, nine months, and twelve days old. His funeral was said to have been the largest to date ever held in North Ogden. He was revered for his memories, his testimony of the gospel, his loyalty, his citizenship, and his being “a zealous, unweary, an indefatigable worker for the good of the public.”[76]

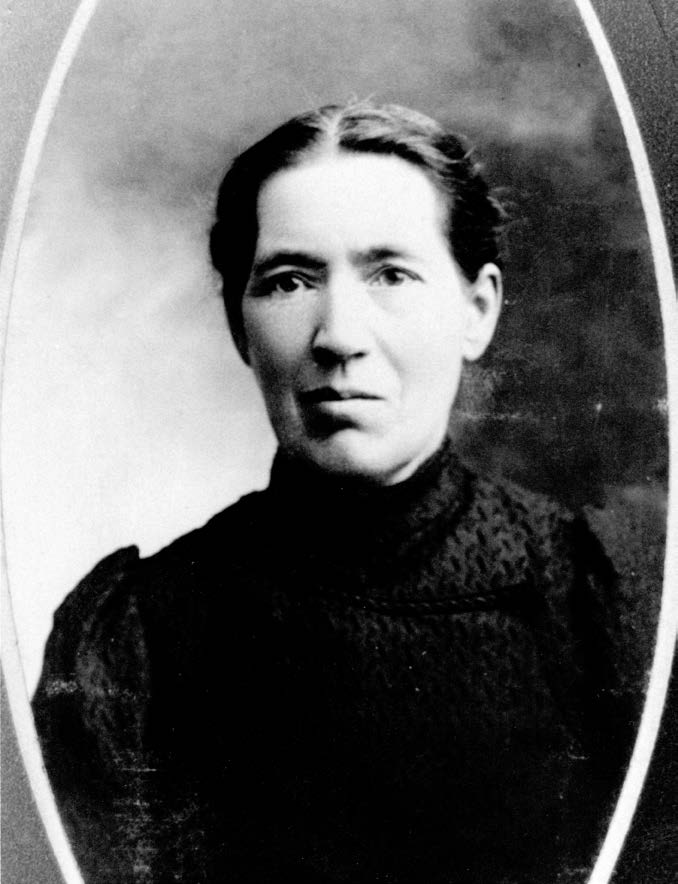

Sarah Ann Price

Sarah Ann Price-Godfrey

Sarah Ann Price-Godfrey

(1842–1928). Courtesy of

Godfrey Family Organization.

Sarah Ann Price (1842–1928) became Joseph Godfrey’s third wife. She was born 7 February 1842, in Rhymney, Monmouthshire, South Wales. Rhymney sits on the north side of the Bristol Channel, fifty-three miles north of the city of Bristol. In the mid-1800s, Bristol was a small ironworks factory town using the coal from the local pit mines. Sarah’s father, Jeremiah Price, was a superintendent at one of the mines and considered well-off financially.[77] He owned several homes in the area that he rented out to the mine workers.

Jeremiah, his son Josiah, and his daughter Sarah Ann met the Mormon missionaries in 1851. They were baptized the night of 4 December 1851 under a bridge and out of sight to avoid being seen and avert the persecution that would follow. However, when Jeremiah’s employer found out that he had joined the LDS faith, he was fired. The discrimination created family hardship. He lost his salary. Funds that he had lent earlier LDS immigrants went unpaid and now they were unable to help other immigrants, let alone repay their own debts. He was shunned by his former employer, friends, and peers, unable to sell his home and belongings at a fair market price for his voyage to America.[78]

Sarah’s mother, Jane Morgan Price, was a petite woman with dark hair, thick dark eyebrows, and dark skin. She apprenticed as a dressmaker and was a quick learner. She sold her dresses and clothing in the Bristol marketplace, which greatly helped with family finances. While sewing at home she displayed dresses and hats in the window and sold them out of their house. She valued a clean, neat home and scrubbed the floor of their home with sand, making the floor boards white and smooth. One day, while working in the house, their cow escaped the pasture. Jane left her scrubbing and ran to corral the cow. When she returned, she found her oldest daughter, Jane, still a baby, had somehow fallen into the bucket and drowned.[79]

Sarah spent much of her childhood with her grandmother, Margaret Liewelln Morgan. Why she lived with her grandparents is unknown, but it was five miles from her parents’ home in Merthyr Tydvil. Sarah walked the distance often and was frightened by the loud men and noise of the large ironworks factory as well as by a cemetery she passed on her journeys.[80] The family’s faith had always been strong. As Methodists, they walked a short distance every week to Sunday School, singing gospel hymns along the way. When they joined the Mormon Church, the walk became five miles. Walking was their only option for transportation.

Brother and Sister Come West

The Price family wanted to join the European exodus of Mormons to America and the Great Salt Lake Valley. The unemployed Jeremiah was particularly anxious, but his wife was reluctant to leave her fine two-story English brick home.[81] They decided to send two of their children first, with the remaining children and parents to join them in a few years. The two children to emigrate were eleven-year-old Sarah and her older brother Josiah, age nineteen.[82] May was afraid, as any mother would be, to let them go alone, but she relented in the end. Their journey took six weeks. They walked from their home to Merthyr, caught the train to Swansea, and sailed from there to Liverpool. They got lost wandering through the city, but eventually boarded the ship Jersey on 25 January 1853. Sarah celebrated her eleventh birthday while crossing the Atlantic.[83]

The Jersey sailed south over the Atlantic Ocean, through the Gulf of Mexico to New Orleans, and up the Mississippi River, where it landed in Keokuk, Iowa, at the state’s southeastern tip. At the time, Keokuk was one of the centers used for outfitting the Mormon settlers and other westward migrants.[84] In the spring of 1853, “2,548 Saints, 360 wagons, 1,440 oxen, and 720 milk cows” came across the plains in ten different wagon trains from Keokuk.[85] Sarah and her brother were with the Joseph Young Company.

Sarah had no wagon, no handcart, and no shoes; she walked the Plains barefoot. One day, she was playing with the other girls along the Platte River, where she almost lost her life. The children had been running along the river banks “killing rattlesnakes, swinging on the vines of the trees.” Each child took a turn pulling a makeshift play raft from the shore as the other children rode the water’s edge. It was Sarah’s turn to ride when the elders called the children to return to camp. Without thinking, the girls dropped the rope and started running. The raft, caught by a strong current, began gliding rapidly down the river. Sarah screamed for help, and the men had a difficult time retrieving the raft and pulling the child to safety. In the end, no one was hurt and Sarah was rescued.[86]

One day, while she was walking next to a wagon, an Indian from the Plains walked up, took her by the hand, and began walking alongside her. The intruder startled the company, and when “Brother Young saw the two, he ordered Sarah into the wagon, but the Indian would not let go of her hand,” so the whole company stopped. They fed the Indian, after which everyone moved on.[87] The company arrived in Salt Lake City on 10 October 1853.

Sarah earned her keep, working for room and board. She lived with several families over the next few years, all the time being observed carefully by her older brother Josiah, who helped her move each time it was required. At one time, she lived with three different families in one room. Some families were hard on her, treating her poorly, and others were kind. She was sent to school from time to time.[88] In the two years before her parents arrived, she was “bumped around from pillar to post” in a life full of uncertainty. She later described her duties as “running errands, gathering wood . . ., rocking the cradle that always seemed to be in use, or the many small things that small hands could do to help lighten the work of older folks.”[89]

Sarah’s parents, Jeremiah and Jane Price, arrived in the United States on 22 May 1855. It had been a heartbreaking passage. They lost a child at sea, but they did not turn back. They had sailed for Philadelphia on the ship Chimborazo, a journey lasting thirty-five days. The ship carried 431 people who were mostly financed with funds from the Perpetual Emigrating Fund.[90] They took the train from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh, a steamboat along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers to St. Louis, and then they camped at Gravery, Missouri, three miles north. Here they boarded a steamboat to Mormon Grove, near Atchison, Kansas, where the company was outfitted and organized. There were 350 people and 39 wagons in the sixth PEF company. Charles A. Harper was captain. They departed between 25 and 31 July 1855 on a three-month journey before they arrived in Salt Lake City around the 28 or 31 October 1855.[91]

Jeremiah, age fifty-one, and Jane, age forty-six, first settled in Payson, Utah. Sarah’s mother continued selling her fine hand-sewn clothing as she had done in England, and they started a poultry business raising chickens and selling them in town. On 19 March 1860, while Jane was doing the washing, Jeremiah and their son John were crossing Utah Lake on the ice to deliver chickens to their customers when the ice in the center of the lake broke and they fell through. Jeremiah pushed John out of the freezing water and John ran for help. Jeremiah had frozen to death before help had arrived. It was a blow to Sarah and the family.[92]

Their son Josiah had already acquired property in North Ogden and started to build an adobe home. Sarah and her mother and family moved north—close to Joseph Godfrey’s home—to be together and help one another. Sarah had already married Joseph, and now her family were their neighbors.[93]

The Youngest Bride

In comparison to the newly arrived Price family, who continued to struggle with life’s tragedies, Joseph Godfrey was an established member of the North Ogden community. Josiah likely knew Joseph, and Sarah first met him when he visited her home to enlist the aid of her older sister Ann. However, Ann was engaged to Rosser Jenkins and unable to accept employment.[94] Sarah was given the offer and had three weeks to make up her mind. She accepted. She worked for Joseph and his family for a month before Joseph proposed and they were married. Joseph and the family were very conscious of the age difference between Joseph and Sarah. She was yet a teenager, fifteen years of age; he was fifty-seven.[95] Their marriage, performed by Brigham Young, was to provide care for a young “daughter of Father in Heaven.” Family records report that Joseph “did not live with her until she became a mature woman.” Their first son, John, was born almost three years later on 12 December 1859. It was the first period of stability Sarah had in her life. She lived as a child with both her grandmother and her parents in England. She traveled across the Atlantic Ocean and walked the Great Plains. She shuffled from house to house, working for her room and board. She had lost her father in a tragic accident. The only constant in her teenage life, for almost six years, had been her older brother Josiah. As Joseph’s wife, she now had an anchor and a home of her own. Her first anchor was the gospel; her second, a stable family. Her own father had been middle-aged when he had married her mother, a teenage bride.[96] Sarah lived the pioneer life with Joseph, working the farm and spending time assisting others. She was thirty-eight when Joseph died. Their youngest child was one month old.

The Lady

Sarah Ann Price Godfrey was a small woman. She wore her hair parted at the center and braided down her back. She had a sharp nose and loving eyes. She always wore a black satin dress. She spent her life in church and family service. She taught Sunday School and was in the Primary presidency. She, like Joseph, was compassionate and caring. She was set apart with other sisters to “wash and anoint the sick, prepare and lay out the dead for burial.”[97] The hardships of her earlier life gave her empathy for others.

At fifty-four years of age, she wanted to travel and spend time with her children. In 1896, she formally achieved her citizenship in the United States of America so that she could move about freely and live where she wanted.[98] By 1898, she had homesteaded 160 acres near Choteau, Montana.[99] Her children homesteaded throughout central Montana and southern Alberta. She spent a good deal of her later life with them in Idaho, Montana, Utah, and Alberta. At eighty-six years of age she recognized that her time in life was short; “she was glad that she was going” and remarked that “she would not trade her husband [Joseph] for any man on earth.”[100]

At the time of her death, she and Joseph’s progeny numbered nine children, seventy grandchildren, 117 great-grandchildren, and four great-great-grandchildren.[101] It was Sarah and Joseph’s eighth son, Melvin, who, with several of his brothers, would eventually make the trek into Canada.

Notes

[1] See Christopher Hibbert, Queen Victoria: A Personal History (London: Harper Collins, 2000).

[2] See George Behler, Child Abuse and Moral Reform in England, 1870–1908 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1982).

[3] See Michael Slater, Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing (London: Yale University Press, 2009).

[4] In family papers, Joseph’s birth date varies from 1794 to 1806. Clarice Godfrey confirms that Joseph was christened at St. Mary Redcliffe on 1 March 1806. Primary histories include Ellen Clair Weaver Shaeffer, “Joseph Godfrey, 1806–1880: A Compilation of Various Sources,” 2008; John W. Gibson, “Biographical Sketch of Joseph Godfrey,” 1925, Godfrey Family Papers; Jemima Helen Godfrey, “Joseph Godfrey,” handwritten document related by Jemima to Lorine Woodwan and Myrtle C. Swainston, 31 December 1955, Godfrey Family Papers; Arlene G. Payne’s work, “Joseph Godfrey Our Grandfather,” Godfrey Family Papers, is a fictional children’s story based in fact and illustrated by her grandson.

[5] Margaret’s name appears as Barrows, Bauer, and Barron in differing family histories. The original parish records indicate Barrows. A later bishop’s transcription changes this to Barron. If these records are accurate, she would have died when Joseph was twenty to twenty-five years of age, thus further confusing the family relationships and dates. Correspondence with Marilyn Rose Pitcher, 1 June 2015, Godfrey Family Papers.

[6] As of the publication of this book, no documentation was found as to why his mother was absent.

[7] Arthur Meecham, “A Brief Sketch of the Life of Joseph Godfrey,” 1, Godfrey Family Papers.

[8] See Mary Ellen Godfrey Meacham, “Joseph Godfrey,” 1, Godfrey Family Papers.

[9] Melvin Godfrey, “Brief History of Melvin Godfrey,” 1, handwritten document in Godfrey Family Papers. Other sources place the age at eight or nine. Eleven fits his history better, given the maturity of the thinking.

[10] Lois Lindsay Anderson, untitled sketch on the life of Joseph Godfrey, Godfrey Family Papers.

[11] As of the publication of this book, the name of the captain or the ship was not discovered in any of the sources.

[12] Anderson, untitled sketch on the life of Joseph Godfrey.

[13] Quoted from Joseph’s grandson J. Arthur Meecham, “A Brief Sketch of the Life of Joseph Godfrey,” 1, Godfrey Family Papers.

[14] Reports of Joseph’s time at sea range from nineteen to thirty-one years.

[15] See Arthur Meecham, “A Brief Sketch of the Life of Joseph Godfrey,” 1. Meecham was a grandson giving a history lesson about his grandfather’s life. Meecham indicated that Joseph remembered the Crimean War. This is unlikely, as this conflict occurred from 1853 to 1856, when Joseph lived in North Ogden. If Joseph remembered the Battle of Trafalgar and the death of Horatio Nelson, it would have been at the very beginning of his experiences at sea, as the battle took place in 1805. Lord Nelson was a heroic British admiral who was shot and killed during the Battle of Trafalgar.

[16] As of the publication of this book, there was no documented time line for these events. To be considered for the position of captain would mean that Joseph was a mature adult when he was near the end of his career at sea. Whether Joseph debarked in Prescott, Ontario, or Quebec City, Quebec, remains a question. Prescott was a bustling town, a transfer point for cargo where travelers and settlers headed west. Travelers usually came from Montreal via stage coach. However, it is unlikely the ship sailed all the way from Quebec City to Prescott because it would have been difficult to navigate the rapids of the river without the canal system, which was not in place until 1845. Letter from Robert Dalley, general manager, port of Prescott, to Donald G. Godfrey, 30 October 2012. Jemima Helen Godfrey reports it was a “Canadian” port. See Jemima Helen Godfrey, daughter of Joseph Godfrey, as related to Lorine Goodwin and Myrtle C. Swainston, 1.

[17] In order to provide verification of information and events, it has been helpful to corroborate the records of the Joseph Godfrey and George Coleman families. While both families’ records are scant, there is no doubt that Joseph and George were stalwart friends: they married sisters, worked together, served in the military together, and lived parallel lives. See “Our Pioneer Heritage: The Moroni Coleman Family,” Magrath, Alberta, Canada, 2009, Magrath Museum. Hereafter referred to as “Coleman Family History.” George was born 2 March 1817 in Norfolk, England. “Coleman Family History,” 15.

[18] The Coleman family records confirm the records of Melvin Godfrey, Joseph’s son, which place the ship in Canadian waters. See Melvin Godfrey, “Brief History of Melvin Godfrey;” 1. Other reports vary as to whether the port was New York or Prescott.

[19] This assumes the 1800 birth date.

[20] Frank Alfred Randall and John D. Randall, History of the Development of Building Construction in Chicago (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1949; repr. 1999), 57, 88.

[21] “Coleman Family History,” 15, 79. These records indicated they served under Colonel Rattler.

[22] This name appears in two ways: Reeves and Rheese. The “Coleman Family History” uses the former.

[23] Ann Elizabeth Eliza was born 28 September in either 1817 or 1818. Mary was born 6 August 1820. See FamilySearch.org. Mary’s marriage date was 7 November 1842. “Coleman Family History,” 15.

[24] See Ernest J. Wrage and Barnet Baskerville, American Forum: Speeches on Historic Issues, 1788–1900 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1967).

[25] For more historical background of the Church during this time period, see Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830–1900 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1993).

[26] Andrew H. Hedges, Alex D. Smith, and Brent M. Rogers, eds., Journals, Volume 3: May 1843–June 1845, vol. 3 of the Journals series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin and Matthew J. Grow (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2015), 169.

[27] The only “H. Jacobs” appearing in the source materials at this time was Henry Bailey Jacobs. He was the first husband of Zina Diantha Huntington. She would later marry Joseph Smith, then Brigham Young. See Martha Sonntag Bradley and Mary Brown Firmage Woodward, 4 Zinas: A Story of Mothers and Daughters on the Mormon Frontier (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2000), 111–15; Donna Hill, Joseph Smith: The First Mormon (New York: Doubleday & Company, 1977), 361.

[28] “Coleman Family History,” 15.

[29] Secondary sources indicate that Joseph told stories of the mobs and his association with the prophet Joseph Smith. However, there is little detail or primary evidence of these events.

[30] Benjamin L. Clapp was a member of the First Council of the Seventy from 1845 to 1859 and was later excommunicated. See Encyclopedia of Mormonism (New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1992), s.v. “Appendix 1: Biographical Register of General Church Officers,” 1634, “Appendix 5: General Church Officers,” 1680.

[31] The order was rescinded in 2006 by a state resolution asking for pardon and forgiveness. See also Thomas Ford, A History of Illinois (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1995), 180.

[32] Ford, A History of Illinois, 243–48. See Dallin H. Oaks and Marvin S. Hill, Carthage Conspiracy: The Trial of the Accused Assassins of Joseph Smith (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1975), 1–45.

[33] See Marshall Hamilton, “From Assassination to Expulsion: Two Years of Distrust, Hostility, and Violence,” in Kingdom on the Mississippi Revisited: Nauvoo in Mormon History, ed. Roger D. Laumius and John E. Hallwas (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1996), 214–30.

[34] Norma Baldwin Ricketts, The Mormon Battalion: U.S. Army of the West, 1846–1848 (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1986), 1.

[35] Dale L. Morgan, “The State of Deseret,” Utah Historical Quarterly 8 (1940): 65–251.

[36] “Joseph Godfrey of North Ogden Utah,” 6, author unknown, handwritten document in Godfrey Family Papers.

[37] “Joseph Godfrey of North Ogden Utah,” 6.

[38] Ricketts, The Mormon Battalion, 21.

[39] Ricketts, The Mormon Battalion, 242–44. “Coleman Family History,” 17, 35. These records place his death at sixty-five miles from Sante Fe, New Mexico, on 18 December 1846.

[40] The rumors seem to stem from John W. Gibson in “Biographical Sketch of Joseph Godfrey,” 2–3. John William Gibson Jr. and Sr. were contemporary residents of North Ogden. See Jeanette Greenwell and Laura Chadwick Kump, Our North Ogden Pioneers, 1851–1900 (North Ogden, UT: Watkins Printing, 1998), 227–30. Page reference denotes the typewritten manuscript. The original handwritten document is in the Godfrey Family Papers.

[41] Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 18–21.

[42] “6th Company,” Deseret News Weekly, September 1852, 2.

[43] Francelia, “The Story of May Reeve’s Life,” 6, in Godfrey Family Papers.

[44] Lucy Brown Archer, “Women of the Mormon Battalion: Wives and Daughters of the Soldiers, 1846–1848,” The Life, Times, and Family of Orson Pratt Brown, http://

[45] “Coleman Family Papers,” 25.

[46] Jemima Helen Godfrey, as related to Loraine Goodwin and Myrtle C. Swainston, 3.

[47] Floyd J. Woodfield and Clara Woodfield, A History of North Ogden: Beginnings to 1985 (North Ogden, UT: Empire Printing, 1886), 203.

[48] See Greenwell and Kump, Our North Ogden Pioneers, 44–64. Today, Barrett Lane runs 600 East from 2100 North to 2550 North.

[49] Greenwell and Kump, Our North Ogden Pioneers, 360–71, 510–816. Today Orton Lane is 2100 North from Washington to Fruitland Drive. No designation for Woodfield Lane was located.

[50] Laura Chadwick Kump to the Godfrey Family, 16 November 1991, Godfrey Family Papers. This letter contains a rough diagram of the property.

[51] John Thomas Hall and John Hall Sr. were contemporary residents of North Ogden. See Greenwell and Kump, Our North Ogden Pioneers, 251–53. Numerous histories credit Joseph for naming Mount Ben Lomond in North Ogden. See letter from Lorin Card Godfrey to Donald G. Godfrey, 14 November 2012, Godfrey Family Papers, indicating that the director of the North Ogden Cemetery suggested Joseph had indeed named the mountain.

[52] Port Glasgow was a trading port where ships from Europe and Britain were unloaded and taken up river to the city of Glasgow. The naming of North Ogden’s Mount Ben Lomond is a debated subject. The tintype of Joseph Godfrey notes that he saw the mountain “every voyage he sailed on Loch Lomond at the foot on Scotland’s Ben.” This is inaccurate. When Joseph saw the mountain it would have been during the time he sailed up the Firth [Gulf] of Clyde and the River Clyde to Port Glasgow, Scotland. Author’s correspondence with Genna Tougher from the University of Glasgow Archive Services; and Barbara McLean from Mitchell Library Archives, Glasgow, 12 December 2012 and 19 December 2012. See “Tintype of Joseph Godfrey,” Godfrey Family Papers. Also, Jemima Helen Godfrey, as related to Lorine Goodwin and Myrtle C. Swainston, 1.

[53] In Joseph’s day, bishoprics served until they were released, which could mean decades of service.

[54] Woodfield and Woodfield, A History of North Ogden, 46.

[55] At a bishops’ storehouse, goods are not purchased but given to those in need. It is unlike the dole in that service may be required of the recipients, the goal being independence, not dependence. See R. Quinn Gardner, “Bishop’s Storehouse,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1992), 1:123–25.

[56] Gibson, “Biographical Sketch of Joseph Godfrey,” 6.

[57] Several varieties of wild thistle can be eaten as greens and are thought to have medicinal properties. Woodfield and Woodfield, A History of North Ogden, 19, mentions sourdock or sour dock as a food source. This is a sour-tasting herb, which can be used in salads or cooked carefully. It had to be prepared cautiously or it could make one sick. The bulbs of the sego lily were common in Utah and eaten by the pioneers.

[58] Meecham, “A Brief Sketch of the Life of Joseph Godfrey,” 4. Also, Woodfield, A History of North Ogden, 298.

[59] Greenwell and Kump, Our North Ogden Pioneers, 236–37.

[60] See Jemima Helen Godfrey, as related to Lorine Goodwin and Myrtle C. Swainston, 2. Also, Francelia, “The Story of May Reeve’s Life,” 6, Godfrey Family Papers. No additional confirmation could be located relative to the relationship between Mary and Tolman.

[61] “Coleman Family Papers,” 25. This is the first point at which the 2015-dollar equivalents are introduced. The inflation calculator used in this writing is http://

[62] Francelia, “The Story of May Reeve’s Life,” 9, Godfrey Family Papers.

[63] Greenwell and Kump, Our North Ogden Pioneers, 238. Here, Mary’s granddaughter Francelia mentions that “there was much tension in the home” and thus Mary decided to move. However, there is no other documentation that supports Francelia’s claim—quite the contrary. Greenwell and Kump indicate that Joseph was a frequent visitor and they had two more children. Did Mary move because of contention? Or, as with many other plural wives, had she simply established a separate home as antipolygamy pressures increased? See Frederick M. Huchel, A History of Box Elder County (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1999), 364.

[64] Woodfield and Woodfield, A History of North Ogden, 11–12. Richard D. Poll, “Utah Expedition,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1992), 1500–1502.

[65] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 170–74.

[66] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 192.

[67] “Joseph Godfrey of North Ogden Utah,” 7–8.

[68] Woodfield and Woodfield, A History of North Ogden, 10–11, 17. Also Gibson, “Biographical Sketch of Joseph Godfrey,” 4–5.

[69] Gibson, “Biographical Sketch of Joseph Godfrey,” 6. These local debates were a common form of small-community entertainment, along with the traveling Chautauqua speakers, local social dances, singing, and picnics. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Chautauqua was a popular entertainment enterprise, which included vaudeville entertainers, traveling preachers, politicians, and lecturers who traveled the circuit.

[70] See Jemima Helen Godfrey, as related to Lorine Goodwin and Myrtle C. Swainston, 3.

[71] Thersa Chadwick Lowder, “Life of Joseph Godfrey,” 3, Godfrey Family Papers. Lowder was Joseph’s granddaughter.

[72] This word is sometimes seen spelled “Hmigary.”

[73] “Died,” Deseret News, 26 February 1880, 16. Frank Esshom, Pioneers and Prominent Men of Utah (Salt Lake City: Utah Pioneers Book Publishing Company, 1913), 892.

[74] Helm was a resident of nearby Pleasant View, Utah. See Woodfield and Woodfield, A History of North Ogden, 125.

[75] “A Surprise Party,” Ogden Standard Examiner, 13 March 1800, 2. The article was written by an unknown subscriber. This practice was common in frontier journalism at the time as locals and travelers shared information.

[76] Lowder, “Life of Joseph Godfrey,” 4. “Died,” Deseret News, 12 January 1881, 16.

[77] This name appears with several different spellings in family records: Jermiah, Jeramiah, and Jermia—Jeremiah is correct. LaVerna Coleman Ackroyd, in her untitled single page history, indicated this was a limestone mine. Other sources indicate coal being mined.

[78] Myrtle C. Swainston, “Brief History of Jane Morgan Price,” Godfrey Family Papers. Myrtle C. Swainston was a great granddaughter of Sarah. “Jeremiah Price and Jane Morgan Price,” Godfrey Family Papers. “Jane Morgan Price,” Godfrey Family Papers.

[79] Myrtle C. Swainston, “Brief History of Jane Morgan Price,” Godfrey Family Papers. Myrtle C. Swainston was a great granddaughter of Sarah. La Verna Coleman Ackroyd, “Jeremiah Price and Jane Morgan Price,” Godfrey Family Papers. La Verna Coleman Ackroyd is also a granddaughter of Sarah. Jemima Campbell, “Jane Morgan Price,” Godfrey Family Papers.

[80] Jemima Campbell, “Jane Morgan Price,” Godfrey Family Papers.

[81] Myrtle C. Swainston, “Brief History of Jane Morgan Price,” Godfrey Family Papers.

[82] Swainston’s history indicates Sarah was nine years of age when she came to America. The Thersa Chadwick Louder history, “Sarah Ann Price Godfrey,” indicates she was ten. These appear to be errors. If Sarah was born in 1842 and sailed for the United States in 1853, then she was eleven.

[83] La Verna Coleman Ackroyd, “Jeremiah Price and Jane Morgan Price.” Louder, “Sarah Ann Price Godfrey,” Godfrey Family Papers. At this point, Joseph Godfrey would have already been settled in North Ogden. Jeremiah and Jane would leave 17 April 1855 and arrive in North Ogden in October 1855. The cost for an adult passage was $800 ($22,432).

[84] Andrew Jensen, Encyclopedic History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 398

[85] William G. Hartley, “Mormons and Early Iowa History (1838 to 1858): Eight Distinct Connections,” The Annals of Iowa 59 (Summer 2000): 217–60.

[86] “Sarah Ann Price Godfrey, As Told by Herself,” 29 October 1928, handwritten and typewritten copies, Godfrey Family Papers; Josephine Swensen, “Sarah Ann Price Godfrey,” typewritten document in Godfrey Family Papers; Ellen Clair Weaver Shaeffer, “Sarah Ann Price Godfrey, 1842–1928,” 2009, 6.

[87] Josephine Swensen [daughter], “Sarah Ann Price Godfrey;” typewritten document in Godfrey Family Papers.

[88] Shaeffer, “Sarah Ann Price Godfrey, 1842–1928,” 6. Louder, “Sarah Ann Price Godfrey,” Godfrey Family Papers.

[89] Shaeffer, “Sarah Ann Price Godfrey, 1842–1928,” 8.

[90] Conway B. Sonne, Ships, Saints, and Mariners: A Maritime Encyclopedia of Mormon Migration, 1830–1890 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1987), 42.

[91] “Immigration List,” Deseret News, 12 September 1855, 214–15.

[92] La Verna Coleman Ackroyd, “A Few Lines About Our Grandparents,” typewritten manuscript (n.d.); Jemima Campbell, “Jeremiah Price,” handwritten manuscript (n.d.); “Jeremiah Price,” Daughters of Utah Pioneers, Our Pioneer Heritage 2 (1959): 170; typewritten excerpt in Godfrey Family Papers.

[93] Shaeffer, “Sarah Ann Price Godfrey, 1842–1928,” 7. “Sarah Ann Price Godfrey, As Told to Her Daughter Josephine Swensen,” Godfrey Family Papers.

[94] Shaeffer, “Sarah Ann Price Godfrey, 1842–1928,” 7–8.

[95] Sarah was born on 7 February 1842, got married 7 March 1857, and had her first child on 12 December 1859.

[96] Family records indicate Mary was eighteen when she married Jeremiah Price. Mary was born 28 January 1810, got married 20 February 1929, and gave birth to her first child in 1830. See Myrtle C. Swainston, “Brief History of Jane Morgan Price.” Jemiama Campbell, “Jane Morgan Price and Clarice Godfrey,” Godfrey Family Papers; La Verna Coleman Ackroyd, “Jeremiah Price and Jane Morgan Price,” Godfrey Family Papers.

[97] Swenson, “Sarah Ann Price Godfrey,” 4.

[98] Declaration of Intention, United States of America District Court of the Tenth Judicial District of the State of Montana and for the County of Choteau, 6 March 1896, copy in Godfrey Family Papers.

[99] Homestead Certificate 4505, Helena, Montana Land Office, 6 April 1898, copy in Godfrey Family Papers. Homestead Certificate 1372, Helena, Montana Land Office, 25 November 1902, copy in Godfrey Family Papers.

[100] “The Life History of Sarah Ann Price,” written by an unidentified granddaughter, typewritten document in Godfrey Family Papers.

[101] Swenson, “Sarah Ann Price Godfrey,” 4; Correspondence from Floyd Godfrey [grandson] to the author, 6 February 1985, Godfrey Family Papers.