Small-Town Business

Donald G. Godfrey, "Small-Town Business," in In Their Footsteps: Mormon Pioneers of Faith (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 285–314.

By the end of the 1930s, the Great Depression was passing, and the world was making the transition into World War II. The war caused social upheaval, but, at the same time, it was an economic revitalization. Canada was drawn into the war on 9 September 1939, in support of Great Britain and Europe. The war drew Canada into a critical position in the battle for the Atlantic and against the German air assaults, helping to grow the Canadian industrial manufacturing base.[1]

Farming, ranching, and other small-town businesses struggled but ultimately succeeded within the overarching tides of the nation’s economy—war, drifting consumer whims, transportation, competition, the evolution of society, and in southern Alberta, even the weather. Agriculture remained central to southern Alberta life. Cardston was the center of a unique market defined by ranches, small settlements, and the First Nations people in the region. Mountain View, Waterton Park, and Twin Butte framed the west side; the Blood Reserve, Standoff, Hillspring, and Glenwood to the north; Raley, Woolford, Spring Coulee, Magrath, and Raymond on the east side; and Aetna, Kimball, Jefferson Del Bonita, and Owendale to the south. In-town enterprise included blacksmith shops, saddle shops, a printing office, grocery stores, hardware stores, and an early community theater featured in the Cardston Tabernacle.[2] In the beginning, Cardston was a growing hub. Common religious beliefs and life’s challenges drew people together. Just a few families rolled into Cardston in 1887, but the population soon grew. Six years following the arrival of the first settlers, in 1893, the population was 593, and by 1901 it had 631 residents.[3] Today, the population has reached 4,167.[4] During the first few years, the growing land shortages in Utah contributed to the population growth in Cardston. The 1913 announcement of a temple in Alberta fulfilled the early pioneers’ dreams and fostered growth.[5]

Transportation was key to the growth of Cardston. The settlers first came to Cardston in horse-drawn and ox-drawn covered wagons. Freight from the United States was hauled up the trail from Fort Benton, Montana.[6] The Lethbridge stagecoach even stopped at Cardston.[7] Democrat wagons—horse-drawn carriages—were the first personal means of transportation. As the region’s transportation options grew from wagons, to railroads, and finally to automobiles, the distances between families, towns, and neighboring cities seemed to decrease. Business competition came knocking at the doors from the cities of Lethbridge and Calgary. The locally owned businesses always started small in Cardston and seldom grew beyond the region. They were simply passed from one generation to the next with little change. Some grew and were sold; Floyd’s Furniture was one such entrepreneurial enterprise.

Floyd’s Furniture

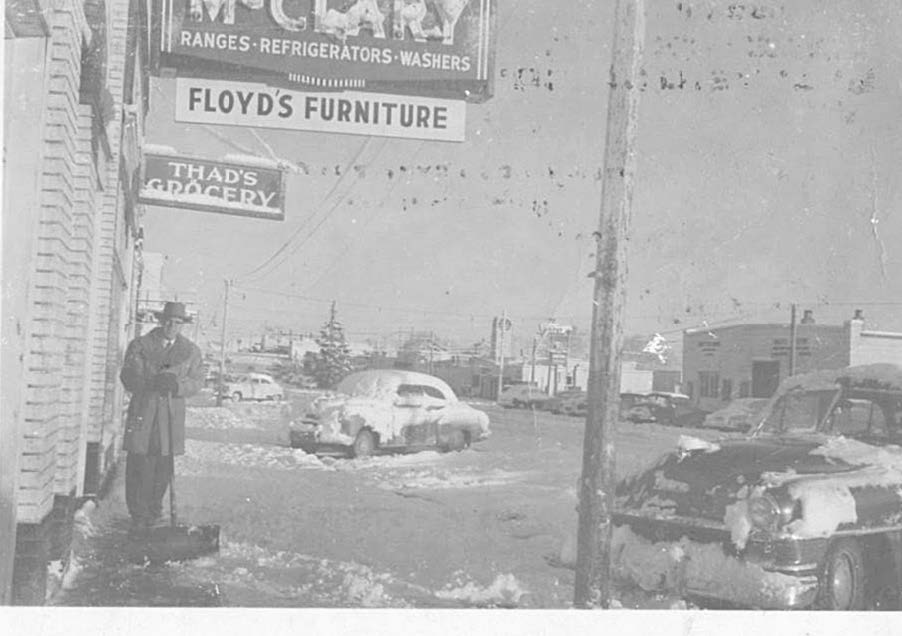

Floyd shovels snow in front of the store, 1950. Courtesy of Godfrey Family Files.

Floyd shovels snow in front of the store, 1950. Courtesy of Godfrey Family Files.

World War II was just ending as Floyd’s Furniture opened its doors. The transition to peacetime and then almost immediately into the Cold War was swift. Soldiers were returning home. Victory in Europe Day was celebrated Tuesday, 8 May 1945.[8] Cardston businesses were responding to change and were growing.

From the mid-1920s and into the 1930s, Floyd worked for the Magrath Trading Company. After that, he moved to Cardston and worked for Coombs Hardware, the Cardston Auto Service, and the Cardston Implement Company. Hardware was his interest and his trade. He had been offered land near Glenwood, but farming was not in his blood. The Cardston Implement Company, which sold furniture, interested him. Other businesses occasionally advertised limited pieces of furniture. The largest was Spencer’s Hardware. During the Depression, it traded furniture for farm products, attracting those who had no cash—“Will trade a good piano for 100 bushels of wheat.” It also advertised that they were willing to deliver the piano and take the wheat out of the bin as a part of the deal.[9] Furniture for sale in Cardston was spotty and an accessory to other business interests. But for Floyd, this was an opportunity. He wanted to branch out on his own, and the timing seemed right.

Spencer’s Hardware opened in 1936 in the middle of the Great Depression. It was initially connected with the Cardston Implement Company, but it broke away and began operating under Cardston Hardware and Furniture. Within a year it was renamed Spencer’s Hardware. In the mid-1940s, Floyd met with David D. Spencer, and Spencer suggested, “Godfrey, you go into the furniture business and I will quit selling it.” Spencer had no interest in furniture; he wanted to sell hardware.[10] Floyd jumped at the suggestion to be independent and grow on his own initiative. He was an entrepreneur and confident in his abilities. The question was simply one of financing.

Conservative Investments

Floyd and Clarice discussed the risks of owning their own business. They were somewhat anxious about the debt incurred. The financial exigencies of the Depression, the losses of their Magrath home, and the move to Cardston were still fresh in their minds and their wallets. They were excited about the prospects, but moved cautiously.

Floyd had just turned forty and Clarice thirty-nine. Their oldest child, Ken, was sixteen; followed by Arlene, fifteen; Marilyn, twelve; Lorin, eleven; Donald, two; and Robert, yet to come in 1951. Floyd drove to Magrath in his first car, a Model A Ford. He wanted his father’s advice before he went to the bank. Melvin encouraged his son, “You can do it, Floyd; . . . now go do it.” So Floyd set out to secure financing. The Royal Bank of Canada would only lend him $1,500 ($18,060), but Melvin agreed to match that with another $1,500, giving Floyd a capital of $3,000 ($36,120).[11] The reluctance of the bank was due to the fact that Floyd had no collateral. He had lost his Magrath home during the Depression and had just built a home in Cardston. However, the banker reasoned, “The way you have shown yourself on Main Street. . . . I’ll lend you [the money].”[12]

The Canadian economy was growing due to World War II manufacturing, and permission to open Floyd’s Furniture as a new household-furniture retail establishment came through the government Wartime Prices and Trade Board on 22 September 1944. Canada’s manufacturing operations were transforming from defense to consumer goods, but the bureaucracy of war still held tight control over progress. It took time for the appropriate authorization and for Floyd to get organized. The formal business license was issued two years later on 31 March 1947 by the Province of Alberta Department of Trade and Industry, eight days after its officially advertised opening.[13] The actual opening was 21 March 1947. “The Store is now open for business in the premises above the Cardston News Office. A large selection of furniture is now on display and new shipments are arriving every day. The new phone number is 266.”[14] Floyd was elated. He thought he might have done more with a larger investment and a bigger grand opening splash, even multiple stores over time, but funds were never available. He would start small and grow slowly.

Furniture Showroom Opens

Floyd invested his start-up cash in three places: a building, inventory, and advertising. He first rented showroom space above the Cardston News building. Entering the store, customers ascended a steep stairway to the second floor. The interior was large and adequate for multiple furniture displays, but there was just one small, square window—large enough to see only one chair from the street below. Floyd had the space; filling it with furniture was the next challenge.

Floyd took two approaches in creating inventory. First, he placed want ads in the Cardston News, letting the community know, “We Buy Used Furniture” and “We Do Upholstery.”[15] He knew there was a substantial market for used furniture, and Clarence Olsen’s upholstery shop was a quick walk from Floyd’s Furniture.[16] Second, Floyd networked in national furniture manufacturing circles. His contacts at the Magrath Trading Company and the Cardston Implement Company were his introduction to furniture wholesalers. He wanted quality furniture: Simmons, Kroeler, McClary Appliances, Mason & Rich pianos, and La-Z-Boy. He ordered the furniture, and it soon began arriving. It was shipped from Vancouver, Calgary, and Toronto manufacturers via the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) to the Cardston Railway Station. Lawrence H. Jessen and Max Pitcher trucked it to the store. Jessen backed his delivery vehicle right up against the rear of the building, where the waiting Godfreys—Floyd, Clarice, Ken, Arlene, Marilyn, and Lorin—all climbed onto the roof of the Cardston News building and lifted the furniture up through the back door of the second floor into the showroom.[17] Carrying the furniture up to the back second-story rooms then down a few steps to the display area was a family affair. Clarice and the children worked right alongside Floyd, Jessen, and Pitcher.

Finally, Floyd had to charm the customers up the front staircase and into the store. The earliest promotions for the store were in the newspaper want ads. The two-to-three lines in the classified section continued for more than ten years. They always emphasized that the store sold used furniture and crafted new upholstery. There was a ready market for good used furniture among the disadvantaged who were living in Moses Lake on the Blood Reservation and returning soldiers who were establishing their first homes. Moses Lake was across the highway, immediately north of the town and adjacent to Highways two and five. Full-page, half-page, and smaller black-and-white display advertisements later targeted the townsfolk, ranchers, farmers, and the surrounding Blood Indian Reservation First Nations people.

By the mid-1950s, Floyd’s Furniture’s sales campaigns included use of direct mail and even radio. Newspaper readers were directed to check their mailboxes for flyers and in-store specials.[18] Full-page flyers were printed on a variety of colored paper and folded and placed in every mail box at the post office—one of the busiest buildings in town. Everyone had a PO Box, as there was no neighborhood or rural delivery. Being somewhat venturous, Floyd even advertised on the airwaves of CJOC-AM radio. At that time, it was the only radio station in the region and reached the entire district.

Growing the Business

Wooden kitchen tables and chairs were the first furniture pieces sold. The solid set cost $89 ($1,078). Floyd remembered, “I must have sold a hundred of those” before manufacturers turned to chrome dinettes, a term synonymous with kitchen tables and chairs. The chrome dinettes trended toward sets with plastic tops and black, iron legs bent into a hairpin style. The newspaper announced the arrival of new chrome chairs and kitchen tables. A new two-piece “Bed Chesterfield [called a sofa and chair in US terms] sold for $165 [$1,999]; unfinished wooden end tables $3.95 [$48]; and a gold leaf framed round mirror, twenty-four-inch heavy plate glass, for $17.95 [$218] at Floyd’s Furniture, Upstairs News Office, phone 266.”[19] Net earnings for Floyd’s Furniture in 1948 were $4,429 ($43,147). Floyd discovered that “you could sell anything” to families relocating to southern Alberta.[20] The Godfreys were off to a strong start and in need of more showroom space.

The old bowling alley and pool hall building on the south block of Main Street became available in the early 1950s. It was next door to both the Mayfair Theater and Thad’s Grocery, two businesses which drew traffic. The building’s drawbacks became painfully obvious: it had only half a floor, no support braces for the roof, and had poor heating. The old furnace belched as much black soot as it did heat. Melting snow from the roof had to be shoveled to prevent possible collapse and leakage. Half of the floor was removed when Gordon Brewerton, the building owner, removed the bowling lanes, which left a long hole in the floor running the width of the building.[21]

Despite the drawbacks, the location gave Floyd significant advantages: approximately 20 percent more space on the ground floor—which was about forty feet wide and one hundred feet long—and two large display windows at street level. Folks driving past or walking into the movies or grocery store next door would see the new merchandise on display. Floyd felt the location was ideal. Brewerton wanted $75 ($677) per month for rent. Floyd’s Furniture had spent almost five years on the second floor above the Cardston News. He wanted to expand, and he took the chance.

Furnishing the larger store, Floyd and Clarice moved every piece of inventory from the Cardston News building to the new location. It did not fill the expanded space, so they went to what would be the first of many national furniture shows in Toronto, Ontario, looking for the latest styles. Floyd and Clarice wandered through the exhibits and learned about the latest trends in design and home furnishings from national manufacturers and wholesalers. Their homework resulted in new products filling the front half of the store.

National Furniture Shows

Over the years, the annual furniture show became both business and vacation time. Floyd and Clarice took the three-day train ride to Toronto, eating in the dining car and enjoying the scenery across Canada from the observation car. In Toronto, they stayed near the Toronto Exhibition Center on Lake Ontario or with their old Magrath friends Harold and Janet Boucher, and then took the streetcar to the show. The exhibit covered several large buildings with every Canadian manufacturer displaying and selling to retailers. It was three days of constant walking, making purchases for Floyd’s Furniture and the people of Cardston. Shipments were scheduled throughout the year. Networking, as well as inventory, were important elements of the show, and over time Floyd got to know the leading manufacturers as well as their representatives with whom he would work for more than two decades. After each furniture show, Floyd and Clarice visited her sister Melva in Ottawa or the Cahoons in New York, who were friends from Cardston.[22] This became an annual routine as Floyd worked to stay current with trends and the trade. Sometimes their sons Ken and Lorin went along so they could learn the business.

At the 1964 furniture show, Clarice entered a contest that picked the best display, and she won an all-expenses-paid trip to Bermuda. The trip was the first time Floyd and Clarice had ever flown. It was a far cry from train rides and bumpy gravel roads. They spent two weeks on the tropical island. Both the Cardston News and the Lethbridge Herald picked up the story.[23] At home, the youngest son, Robert, suffered a contracted appendicitis attack and needed surgery. At the time, he was staying with Lorin, and with the help of his sisters, Marilyn and Arlene, they all nursed him back to health. There was no emergency phone call to Bermuda; those remaining in Cardston did not want to spoil their parents’ once-in-a-lifetime vacation.

Largest Store in Cardston

Near the end of the 1950s, Gordon Brewerton, the owner of Cardston’s Mayfair Theater, informed Floyd that he wanted to sell the building, but Floyd reminded him that by contract Floyd had the rights of first refusal. Floyd quickly borrowed $11,000 ($87,522) from Lloyd Cahoon, promising to pay $100 ($796) per month at 6 percent interest. The sale was signed, sealed, and delivered 2 March 1961. Floyd was always proud of the fact that he “never missed a payment in those 100 months, a little over eight years.”[24] He cleared the debt and felt free from its pressures.

The next building purchased was the grocery store, which shared a common wall with Floyd’s Furniture. Guy Wilcox owned the grocery store, which he had sold to Thomas Thaddeus Gregson. It was Thad’s Grocery from 1945 to 1953.[25] When Wilcox offered the building to Floyd, the agreement was for $6,000 ($52,760), a $500 ($4,397) down payment and, again, $100 per month.

The Brewerton and Wilcox buildings were aging, so Floyd renovated. He cut a doorway through the support wall between the two buildings, providing customer access and almost doubling his overall square footage. The display space in Thad’s building was smaller, but the dirt-floor warehouse in back offered improved storage, and the front added a third large display window. Floyd acted quickly, installing updated heating and new wiring throughout the showrooms. He hung large fluorescent lights from the ceiling. They stretched about six to eight feet in length and around three feet wide, resembling flipped flat-nosed canoes and providing lighting for the displays. The roof was tarred, but still did not always hold back the weather. The heavy, wet snow caused the ceiling to creak with the weight as a warm Chinook wind turned snow into running water that slowly dripped through the ceiling. This created an immediate danger to the furniture below.

All challenges were met, and the expanded space enabled Floyd’s Furniture to buy a train car full of furniture. The savings were good, as the manufacturer often paid the freight bill. Renovations were costly, but they enhanced the attractiveness of the merchandise and the building, as well as taught the Godfrey children to work—there was always dusting and sweeping to be done. Floyd’s Furniture’s net earnings for 1953 were $6,091 ($53,560).

Business Weather

Business in a small town was small business. The opportunities for expansion were limited without opening new stores in other communities, but Cardston and the Church were still growing. The ranchers, farmers, Natives, and townspeople remained the foundation—a reality never far from Floyd’s mind.

By 1951, just after Floyd had purchased his first building, his success bolstered his courage and trust with his wholesalers. His eldest son, Ken, was in Europe serving in the France Mission, and Floyd reasoned that the family would be blessed for Ken’s service. Southern Alberta crops had never looked better. Taking a gamble, Floyd hesitantly approached Kroehler Furniture and Restmore Bedding and bought $9,000 ($81,794) in mattresses from Restmore and $11,000 ($99,970) in bedroom sets and front-room furniture from Kroehler. The crops were yet to be harvested, but they looked so promising, “just beautiful,” and so, he placed the orders. Lots of new furniture was in route to Cardston; then it started to rain. It was only August and it “never stopped raining.” The rain turned to snow, and “it never stopped snowing!” The crops were frozen, flattened, and rotted on the ground. It was not until spring the following year before the farmers desperately tried digging the frozen ground to rescue what little they could. Here, Floyd had “all this big debt on [his] shoulders,” furniture packed in his showrooms, and farmers with no crops. He called his debtors and explained what had happened, and they encouraged him, saying, “You just keep hammering away and send us what money you can, and we’ll keep taking care of you.”[26] It was an atmosphere of grateful cooperation. Floyd staged a Christmas-extravaganza sale and paid the debtors as much as he could. Clarice pitched in and ran the store while he traveled ranch-to-ranch making contacts. The debts took six years to clear and almost put Floyd’s Furniture out of business.[27] Through Floyd working directly with his wholesale distributors, who gave him leeway on payments, Floyd was able to dodge bankruptcy.

Crazy Days Promotion

As business advanced, so did Floyd’s involvement in the community. As a member of the Chamber of Commerce, he was part of a business development group on Main Street that organized events such as “Dollar Days,” “Crazy Days,” and promotions around the Dominion Day parades. These were small-town marketing tactics organized to bolster business, ideas hatched from the Chamber of Commerce. For Dollar Days, silver coins were stamped, and every merchant had to buy $100 or $200 worth to scatter throughout the community. The coins provided discounts on Main Street merchandise.[28]

During one Crazy Day promotion, the Cardston merchants and Floyd’s Furniture soaped all the windows using water and white Bon Ami (a powdered cleanser that is easily removed) and then covered all of the windows with brown butcher paper. For this sale, the stores did not open until 10 a.m., two hours later than the normal business day. Outside, the customers waited in anticipation. Inside, Floyd, Lorin, and the workers were busy tearing sheets of the brown paper and making torn price tags for everything, some with significant price reductions. During one sale, Floyd advertised a lamp for $1 ($8). First thing that morning, three women appeared at the door, headed straight for the lamp, and started arguing over it. One had hold of the lamp shade and the other two grabbed the stand. Floyd held off ringing up the sale for an hour or so as a cluster of shoppers enjoyed watching the hilarious competition. He finally gave his son Lorin the responsibility of handling the conflict. Names were written on small slips of paper and put into a bowl. Whoever drew his or her own name won the lamp. More profitable than $1 lamps were $99 ($796) Chesterfields desired by women who brought their husbands in tow. The women, liking the more expensive French provincials, opted for quality over savings and requested that their husbands write out the checks. One of the best window displays exhibited a friend of Floyd’s, Alex Glenn, sound asleep in a La-Z-Boy chair. Floyd had covered him with a warm blanket, and Alex slept for a couple of hours. It drew a nice crowd.[29]

Floyd’s Furniture was always a part of any community activity or celebration. During one parade celebration, Floyd dressed as a woman and paraded up and down Main Street as two tremendously embarrassed teenage sons tried to avoid eye contact with their father, who they pretended was a complete stranger. Floyd had fun and attracted attention. Even during the more serious Dominion Day parades, the store always participated with a float that advertised the latest in design, furniture, and appliances. The window display on these celebration days were critical as people lined the street, standing to see the parade and checking out what was in the store windows.

Church and Business Clients

Good service throughout his community evolved into meeting the needs of the growing number of LDS Church buildings across Canada and the development of business customers. This was a significant step forward from the customer base of local families. In 1958, Floyd learned that the Church wanted to buy three thousand folding chairs for its chapels across Canada and were requesting information from the T. Eatons Company of Canada. At that time, Eatons was Canada’s largest retail department store and a significant competitor.[30] The Eatons in Calgary was pursued because the Church was having difficulty getting furnishings across the border into Canada from United States manufacturers. An enterprising Floyd let the presiding bishop of the Church know that he too wanted to bid on the sale of the chairs. He claimed he could eliminate the import problem by providing Canadian products at a better price. He immediately contacted Royal Metal, a Canadian manufacturer, who insisted on an order of 3,100 chairs—one railcar load—but agreed to pay the freight. The cost was $6.35 per chair ($56), and Floyd had to provide the storage until the chairs were shipped throughout southern Alberta and across the country to the different chapels that were under construction. He built a garage next to his home, where the chairs were stored before they were needed and shipped.[31] This was a gigantic opportunity that could lead to other openings, but Floyd’s Furniture was small, and Royal Metal wanted payment within thirty days. Floyd was anxious. He and Clarice traveled to Salt Lake, meeting directly with the Presiding Bishop Joseph L. Wirthlin. Floyd knew Wirthlin from Church association, but he did not realize Wirthlin did all the buying for the whole Church.[32]

Floyd left a trusted employee, Lynn Sommerfelt, in charge of the store and drove off to Salt Lake. When he and Clarice reached the Church Office Building, he paused; he was “in fact scared” to go in. Clarice gave him a loving nudge. “You are as good as they [your competition and the buyers] are now go in there.” Floyd walked in, and Wirthlin was surprised to see him and said, “Well Floyd what can I do for you?” Floyd had done his homework in southern Alberta, surveying the chapels in the district and assessing their need for chairs. Wirthlin reviewed Floyd’s report and responded, “Well the committee are meeting upstairs now, let’s try them.” He called his secretary and asked that Floyd’s order be taken into the meeting to “get it okayed.” Ten minutes later, Floyd had an order for more than $19,000 ($166,898) worth of chairs.[33] He immediately called Royal Metal and gave them the order to ship. They sent Floyd an invoice, he sent it off to the Church, and the check came back ahead of the billing cycle.[34] In Floyd’s personal history, he sketched a little drawing in the margins. It was a cloud. Written inside are the words “Cloud Nine.” It was the beginning of many trips to Salt Lake City, as Floyd’s Furniture was the only LDS furniture distributor in southern Alberta for two decades before new LDS merchants in Lethbridge began circling this prized customer.

Godfrey family folklore tells that Floyd Godfrey spent more time on his knees in the Cardston Alberta Temple than any other temple worker or administrator—he carpeted the temple on multiple occasions. He sold exquisite English wool carpets. One such order called for a carpet labeled “Heaven’s Pile.”[35] As the temple patrons stepped onto it, their feet sank in, and walking across the temple floor seemed more like floating. As the temple carpets showed wear, a call to the Presiding Bishop’s office resulted in new floor coverings.

Renovations to the temple from 1961 to 1962 required carpet to be installed on granite steps. To accomplish this, a “smooth edge” was cut into one-inch pieces and fastened to both sides of the granite stairways with permanent adhesive. Today, “smooth edge” has a more appropriate name; it is called “tack board,” which uses yardsticks with small tack nails hammered through at a forty-five-degree angle. Strips were fastened around the edges of a wall or staircase wherever the carpet was laid. The tacks pointed at right angles toward the wall to grip the fibers. Carefully cut, expensive carpet was stretched and wedged between the tack board and the wall, held in position by the opposing wall. The long hours kneeling on granite stairs and temple floors were painful. Floyd sacrificed comfort for the excellence he wanted and the result expected in the Lord’s house.

Business clients of Floyd’s Furniture included The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and motels in Cardston and Waterton. These were competitive bids, which had to total less than Eatons’s bid. The inventoried order had to line up everything from kitchen pots, plates, pans, and utensils, to light switches, carpets, beds, and mattresses. These bids had to be detailed because, working on slim, competitive profit margins, one error caused the business to lose money.

Floyd was successful in getting the carpet contract for the prestigious Prince of Wales Hotel in the Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park, where he was also the victim of a little humor. His friend, Ted Weston, who was not a member of the LDS Church, hunted high and low for a camera so he could get a picture of Floyd laying carpet in the ornate hotel bar room. Floyd did not drink alcohol and would never be seen in a bar, except perhaps to lay carpet.[36]

In-Kind Trade

Like many small businesses, life in Floyd’s Furniture was not always rosy. On occasion, it required marathon negotiations and a plan to pay a debt. If wholesale inventory was unavailable, a smaller merchant purchased items from the larger retailer in Calgary, creating the necessity of a small markup to stay competitive. These jobs were considered an investment toward future business. The wholesale price and retail markup on any furniture item in Floyd’s Furniture varied depending on product quality, color, style, and manufacturer. Special orders were a little more expensive, but Floyd kept his pricing below big-city competitors. He stressed service and had a reputation for honesty and was therefore able to attract and retain customer loyalty. He made each customer feel that “they were the most important customers Floyd ever had . . . [and] every customer felt the same.”[37] Of course there were occasional complaints, but Floyd moved quickly to resolve any issues, and he was generally successful.

Floyd traded in-kind when times were difficult, when there was a mutual benefit, and when there was a need. He traded meat for a Chesterfield. He traded furniture for the services of a butcher and cold locker storage, for a delivery truck, and for a new blue Chrysler 300 with push-button transmission. Trading was a bedrock for making it easier for the customer as well as the store.

Small Business Challenges

Most of the significant challenges faced by Floyd’s Furniture were weather and crop failures, but there were the occasional disputes, too. One of the more dramatic conflicts came when two women got into a physical confrontation in full view of the store window one day. One pushed the other and she fell through the display and landed in a recliner chair, which toppled over backwards with her legs flying in the air. Arbitration and cleanup were significant.

Floyd’s Furniture was robbed on two occasions. Both incidents ended well. In the first incident, money was missing from the office and so Floyd reported the theft to the town police, who detained a young man. However, rather than file formal charges, Floyd suggested that the man “could work it out,” and over the years this man “became very trustworthy, got married, and [became] one of his [Floyd’s] best customers,” right up to the time Floyd’s Furniture was sold.[38] Floyd knew the man, but his name was never recorded in court or the family records. The second robbery ended when they found the whole unopened safe in a hay field. The safe was heavy, perhaps two feet by three feet of solid steel. The thieves got it out of the store but could not get it open.

First Television in Cardston

One of the first television receptions in Cardston was in the display window of Floyd’s Furniture in early October 1954.[39] Floyd cleared the window next to the Mayfair Theater and placed a small, black-and-white, twenty-one-inch receiver in the display, next to a water bucket for the rain dripping from the ceiling. The signal was coming from CHCT-TV Calgary, the first station on the air in Alberta. The Floyd’s Furniture antenna was extended and pointed north in hopes the signal would reach 145 miles to the south. Floyd turned on the set and checked the screen. What he saw was “snow,” matching the light flakes falling outside the window. He carefully worked the dials, tuning the signal. A ghost of an image appeared through the screen’s snow. He twisted the dials some more as his family and onlookers watched patiently and expectantly, becoming excited at even the slightest outline of an image. A fuzzy image and muffled sound was the best they got, but it would not be long before stations appeared in Lethbridge, and Floyd, his children, and other Cardston families were watching Disney’s nature movies and wrestling matches from the Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto. A few years later, color was added by placing a clear sheet of special plastic over the screen. As the light passed through the filter, red, green, and blue colors appeared to give a vividness to the images. It was soon replaced by the real thing.

Family and Young Employees

Floyd’s Furniture was about more than financing a family and supporting employees; it was also about teamwork. Floyd and Clarice used the store to teach their children, to help others, and to come together. They taught by example. Clarice moved furniture when it was necessary, managed the books, and accompanied Floyd on buying trips to Vancouver, Calgary, and Toronto. When Floyd was asked to perform Church or community service during store hours, she was at the store managing operations.

Lorin was younger and missed the Texaco Gas Station experiences of cleaning washrooms, but in his youth he delivered the daily Lethbridge Herald and eventually worked in the store longer than any other sibling. On his paper route one day, Lorin got caught in a dust storm so dark that he got lost. The dust was blinding, so he hid among the trees near his school. After a brief prayer, he heard someone calling, “Lorin, Lorin,” and knew it was his dad, who had left the store to find his son. They waited out the storm and delivered the remaining papers together. Later, they dusted the furniture together.

Dust brought by the wind could always be found on top of the furniture. If there was no obviously pressing work, Lorin was taught to find something and keep busy—which in a furniture store always meant dusting. If the furniture was dust free, Floyd and a helper would rearrange the furniture, creating new window displays and presentation groupings around the floor of the store. Every one of Floyd and Clarice’s children worked alongside their parents, learning work standards, honesty, ethics, service, and money management. In their younger years, the children had worked together at home and in the gardens just as their parents had done. At Floyd’s Furniture there was the constant need to help with new displays, new arrangements in the windows, deliveries to and from the store, daily sweeps of both the floors and the sidewalk, and daily dusts of the furniture. At times it wasn’t only Floyd’s children that helped; he hired young men preparing for and returning from missions. Floyd’s Furniture did more than put food on the table; it taught principles of living by example and experience. In 1949, Lorin was anxious to attend the first national Canadian scout jamboree in Ottawa, but he had no way of paying for it on his own. His dad offered to pay $100 ($986) toward this trip if Lorin would help unload a rail car full of furniture, which he did with his mother’s and father’s help. His earnings from carting furniture more than paid for his train ride.

Every young man employed by Floyd learned to work. Floyd hired a number of young men over the years: Brent Nielson, Robert Stringham, Alvin Hatch, Dale Tagg, Lynn Sommerfelt, and each of his four sons. He treated them all like extended family. Dale and Lynn stayed longer than others, and Floyd trusted them with the store when he traveled. More than needing help at the store, Floyd enjoyed watching each young man grow. One day, Lynn came into the store and found blood on the floor. Startled, he asked what had happened. An embarrassed Floyd told him, “Never mind,” and after Lynn had cleaned up the mess, Floyd admitted he was stapling a thick, clear plastic over the leaking skylights and had accidentally stapled his finger to the ceiling. Lynn “didn’t dare laugh because he needed the job.”[40]

Floyd reinforced the idea of making the best of your blessings in any situation. While carpeting the temple on one occasion, he cut the carpet incorrectly. Thus, Clarice was blessed with new carpet to cover the hardwood floors in her front room and dining room, and a new piece of matching carpet was ordered for the temple. Carpet laying was on-your-knees labor from start to finish, whether the laborers were in the temple, a chapel, or a home. Nothing went to waste, and making the best of your blessings was the standard.

The carpet incident was not the first time Clarice benefitted from store sales. She loved to host neighborhood club parties. Following these gatherings, a lady in attendance would frequently appear the next day in Floyd’s Furniture wanting “something like Clarice had in her front room.” At this point, that something would disappear from Clarice’s home and she would visit the store feigning aggravation and pick out another. One time her new kitchen table even disappeared and her old, wooden, drop-leaf table sat in its place. She was not happy, but it was replaced. Clarice’s home was a showroom, always full of the newest and the best furniture.

Floyd’s Furniture employees were taught that work was challenging, rewarding, and fun. When delivering fine hardwood furniture, Floyd always reminded his employees, tongue in cheek, of the value of what they were moving, saying, “Don’t scratch the furniture, your fingers will heal.” He loved training new carpet installers. They were normally assigned to lay the felt (now called padding) or carpet underlay, the depth of which gave the carpet its cushion. In the days of Floyd’s Furniture, padding consisted of horsehair pressed into half-inch-thick sheets that was rolled up for transport, just as the carpet was. The sheets were not always smooth. Once this padding was down on the floor, with the carpet on top, a keen eye could identify lumps on the carpet surface. It was the felt layer’s responsibility to take a fist-sized rubber hammer and beat the lumps flat. The start of the hammering was the cue for a friend, usually the lady of the house, to appear frantically yelling, “My canary, my canary, I’ve lost my canary . . . have you seen my canary?” At this point the entire crew, all in on the joke, looked over at the new hire, his rubber hammer frozen in midair. After the appropriate panic level registered on the unsuspecting worker’s face, the entire crew and the lady of the house burst out laughing. The workers in training were most often Floyd’s sons, a son-in-law, or someone he was trying to teach in his own version of a classroom. They learned and had fun.

Learning by the Spirit

One time, a teenage son walked hurriedly through the noisy back door of Floyd’s Furniture from the display area into the warehouse area, only to see his father Floyd kneeling in the dirt and praying. The son stopped and backed out, quietly closing the squeaky storage-room door. Nothing was ever said, but the image was powerful. Many times Floyd “knelt in the back of the store” and poured out his heart.[41]

When his son Lorin was on his mission in South Africa, there came a month when Floyd and Clarice had no money. They had managed to get funds for earlier months, but this month they had nothing. Sales were insufficient, and it was two weeks before the mission payment was due. They were supposed to send the money early so it would arrive in Africa by the end of the month. They fasted and prayed for several days, but the deadline came and no money arrived. “It was a Monday morning and we waited in despair.” Floyd had called on his outstanding accounts, people to whom he had sold furniture and trusted their credit. He had pushed for new sales, all to no avail. They did not know what to do, except trust in the Lord. As if on cue a fellow walked into the store that morning, “Floyd, I am ashamed of myself. . . . I’ve owed you this bill for four months.” He gave Floyd the cash and then he and Clarice went immediately to the bank and the funds were off to South Africa that same day. The Lord had answered their prayers.[42]

Christmas at Floyd’s Furniture and Home

Christmas was a special season at Floyd’s Furniture, because it was busy and Floyd loved Christmas. He exemplified the principle of service, always cautioning against wants versus needs, and, of course, he taught the true meaning of the holiday at home and in his store. He would go to any length to bring Christmas to his family, his neighbors, and his store. Every year, Clarice spent the autumn months preparing Christmas candies, cakes, and puddings. Even the fruit cakes were savored. Most memorable were her homemade breads, rolls, cinnamon buns, chocolate candies, and English toffee. It was difficult for her to stay ahead of her kids, who would eat the candy out of the freezer as fast as she could make it. Floyd and his grandson Roy were playing pool in the basement, aware that Clarice had just placed some Christmas chocolates in the freezer. They knew it was strictly off limits, but they snuck upstairs to see if they could snatch a couple without her noticing. After they had eaten the first few without getting caught, they were trapped and got a stern lecture from Clarice as she turned her back to them and walked away with a smile.

The store was adorned with the spirit, smell, and excitement of the season. None of his children thought much of the extra sealed boxes sitting in the back of the warehouse that were loaded into the delivery truck on Christmas Eve. If asked about the boxes, Floyd would simply suggest he had another delivery he had to make a little later. The store helped out Santa, delivering to family and customers.

Floyd knew his own daughters were Christmas snoopers. More often than not, the charge fell on Arlene, the oldest daughter. She liked poking around her presents and queried her brothers and sisters for hints. Unknowing little brothers were always more than happy to play along with the game until she figured out what gifts she was getting. One year, while Arlene and Marilyn were in their teens, a big parcel arrived addressed to them, “in care of Floyd’s Furniture.” It was from one of Floyd’s eastern Canadian distributers and was labeled “do not open until Christmas.” It had official manufacturing labels and was delivered by the Canadian Pacific Railway to Cardston. A CPR truck delivered it to the house, addressed to both sisters. They could hardly contain themselves. They grilled their father and mother endlessly. They and their friends rattled the long box endlessly, trying to assess its contents. The excitement built as Christmas morning approached. It was the first gift they opened: it was a kitchen broom. Floyd was a practical joker, but it remains uncertain whether the joke about the broom was rightly received. It has, however, produced laughter over the years of its telling. Floyd would frequently appear among the children and rattle the unknown gift contents of a paper bag around Arlene and Marilyn and say, “Oh, you are going to love this.” Clarice was the only one to laugh and protecting her daughters responded, “Floyd, cut it out.” Floyd was a tease and known as “the biggest kid in town.”

The kids decorated the house and the store with colorful streamers and put up Christmas trees. The trees came from either Pole Haven, one of the farmers, or the lot next to Floyd’s Furniture. On Christmas morning Floyd was the first one awake, or maybe he never slept. He grabbed pots and pans from the cupboard and went to each bedroom door, banging the pots loudly until all his children were wide awake. The smells of Christmas were already in the air. After presents were opened, Ken’s electric train knocked over Arlene’s new play cupboard and broke all of her dishes. Memories were not centered on the presents, but on the joys of spending the day together as a family. Relatives and friends arrived and gathered around an L-shaped table for dinner. Games and sharing filled the day and the Christmas dance filled the evening.

Floyd’s Furniture’s display windows were filled with rocking chairs, and cedar-lined hope chests were positioned near the door. The chairs were of every color and size imaginable. Entering the store, people were immediately hit with the smell of fresh cedar emanating from the hope chests. Every young lady wanted a hope chest so as to store items for her own future home, husband, and family. So Floyd offered a large selection. Christmas was a time of giving, sales, and service.

Christmas Eve Deliveries

Many a Christmas Eve was spent delivering furniture until midnight. In this manner, whatever was delivered was a surprise for the wife, daughter, or entire family. In the early ’60s, there was an extra-ugly Chesterfield that sat right behind the rockers. The colors were not complementary, contemporary, or Christmassy; they were dreary. It seemed this poor piece of furniture would remain in the store forever. The arctic wind was howling, and that meant a snow storm was coming. As one of Floyd’s sons entered the warmth of the store that morning, he saw the ugly sofa and said, “Dad, you’re going to have to haul that thing to the dump or give it away.”[43]

Work was rushed on this day when a gentleman came into the store and sat on the ugly couch and began talking with Floyd. In this small town, everyone knew everyone, and it was generally the ladies who dragged their husbands into the furniture store. This man was alone and obviously intense. Floyd said the fellow was “headed to the city where he thought he’d have a better selection.”

The last delivery of the day was done. It was getting colder, and a winter storm was predicted to come in from the north. It was past closing, and the man who had been there in the morning was again sitting on the ugly Chesterfield; this time he was all smiles. His wife was going to get the surprise of her life—a new sofa. Floyd smiled, “We have one more delivery, son,” he said. “We need to go to Waterton.” The gentleman from the morning had purchased the ugliest Chesterfield in the world. “Let’s go now so we can get back early.” That meant they would get back late, as driving in a blizzard was likely.

The wind howled as the ugly sofa was loaded into the truck. The snow had not yet started to fly, but the wind was picking up. The drive to Waterton, thirty miles west, was not particularly picturesque this day because it was too dark to see the mountains. Waterton is a village on the Canadian side of the border within the Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park. On this run, black clouds covered the stars, and the wind drove snow south over the highway.

As the delivery truck entered Waterton, the snowfall was getting heavy. “Let’s hurry,” Floyd urged. “We can make it home before the storm drifts over the road.” The gentleman’s family lived on Wildflower Avenue. The driveway had been cleared, and the snow was piled higher than the truck. The delivery moved quickly, but Floyd’s son struggled at first to match the spirit of this little family, who could hardly wait for this ugly thing to be in their home. The excitement in the air completely muted thoughts of the approaching blizzard. In contrast to his son, Floyd had a broad smile on his face, his voice happy. Was it the final sale of this “special” sofa, or just Floyd’s love of Christmas? It was likely both.

Then the unexpected occurred. There was something of a transformation. As the sofa was set into place, it became an integral part of one of the most beautiful Christmas scenes in memory. The children were jumping on and off the sofa while the mother sat at one end, near the Christmas tree, with tears streaming down her face. The father’s face was radiant. The son thought, “What was the matter with these folks? . . . Couldn’t they see this ugly thing?” No, they could not! Floyd carefully placed the gift in their home, exchanged pleasantries with the children, and rushed to put the chains on the truck for the drive back to Cardston. It was a Christmas picture to be remembered, as that ugly Chesterfield became the beautiful centerpiece of a family Christmas in the cold Rocky Mountains. Floyd didn’t talk much on the way back. The father’s gift of love for his family carried the Christmas spirit into their home. Floyd and his son both saw the transformation that love and joy bring.

Floyd’s service was often given quietly. He helped those he could. Max’s Fast Freight and the sheriff once went to a Native American woman’s home to repossess a kitchen set, table, and chairs for the store.[44] The next day, Floyd and Max Pitcher returned the furnishing to the family’s kitchen. Floyd felt she needed the furniture more than he needed the money, so he gave it to her.[45] This was not a common occurrence, but it happened more than once. He silently supported missionaries financially in the field and no one ever knew. People who accidentally discovered such evidence were sworn to secrecy.

There were many small acts of love and kindness. At times, Floyd let the Hutterite boys into the store and they quietly watched the marvel of television. They were not supposed to watch television, but they were so curious that Floyd let them in. He let Hutterite fathers into the store when all they wanted was to measure the fine wood furniture. After carefully making notes, they returned to their colony and made it themselves. He allowed First Nation mothers into the store where they headed to the back room for privacy to sit and nurse their babies or change a diaper. His kindness was silent and came from his heart.

Toward Retirement

Floyd’s Furniture fluctuated over the many years. It grew when crops were plentiful but wavered with the drought, the weather, growing interest rates, competition from the growing cities of Alberta, and the decline in personal banking. However, it served the Cardston district, the community, local business ventures, and the LDS Church in Canada. It trained Floyd and Clarice’s children to make their way in the world. It taught others in the community about love and service as well as produced furniture for their homes.

Floyd always hoped one of his sons would take over the business he had built. After Ken returned from his mission to France and got married, he worked for the store from 1952 to 1954. Lorin toiled for nearly a decade, from 1955 to 1963. He graduated from BYU and shared his market research that he thought would benefit Floyd’s Furniture. Arlene, Marilyn, Donald, and Robert mostly dusted furniture.[46] Ken moved to Utah after a few years, and Lorin spent the longest working with his father. Arlene and Marilyn married local ranchers, and Donald and Robert were the only remaining youngsters at home, but they were not at the age that either could consider taking over the business. The larger communities of Calgary and Lethbridge grew increasingly easier to reach with automobiles, now the mainstay of transportation. It was difficult to stay increasingly competitive and attract new customers.

Floyd always felt if he had amassed greater collateral or could have borrowed more from the beginning, “perhaps $50,000” ($304,501), he could have launched a chain of stores. He sent Ken to Cranbrook with a truckload of furniture and tried to establish Floyd’s Furniture in British Columbia. Lorin later explored Red Deer, Alberta, for opportunities. Nothing clicked. These were growing markets, which house multiple furniture retailers today, but the banks were not supportive. He asked each of his sons about taking over the Cardston business, but each headed onto different career paths. They had witnessed the burden of debt and knew the profits could not support multiple families. It was not to be. There simply was limited investment money. Floyd would later explain that he “had many ups and downs, but it was a happy time.”[47]

Floyd’s Furniture remained a small-town business. It did not make anyone rich, but it provided an income and the cornerstone for multiple individuals’ futures. The buildings were clear of debt and in the later years used as collateral for operational bank loans. The Godfrey home and property were paid in full. The family car and Floyd’s Furniture’s delivery truck were debt free. Floyd had repaid his father and debtors for their investments and trust in him. Profits were consistent, but a line graph would have shown a roller coaster ride for every year. The best year was 1961, when profits hit $9,404 ($78,823). The worst year followed in 1962 with a profit of only $2,499 ($19,686).[48] In contrast, Floyd’s operational debts with the Royal Bank had increased steadily with parallel pressures as competition and interest rates simultaneously grew.

In 1968, Canadian Simpson Sears opened a major store in Lethbridge. Automobiles and trucks had shrunk the travel time between Floyd’s small town and the cities. Customers now shopped from Cardston, Lethbridge, and Calgary—only short drives away. Floyd’s Furniture found it increasingly difficult to compete. Some years he was just meeting interest payments on the operational loans. He could match or beat city prices for his furniture, but the city stores were lures offering the appearance of greater selection and better pricing. The same merchandise might have been available at Floyd’s Furniture, but perception was winning the competition. Their effect on small-town business was to squeeze Floyd out. Increasing interest rates on bank loans were a progressively heavier load. Trust and reputation had been replaced by the necessity for collateral and cash.

Floyd was sixty-four and Clarice was sixty-three. Floyd’s Furniture had sustained their family for almost twenty-five years. Floyd wanted to serve an LDS mission, which he had been unable to complete in his youth. Floyd’s Furniture was a personal, family, and financial success, but he had a difficult decision to make. He consulted his children and his banker, who was also a personal friend. Floyd was six months away from turning sixty-five years of age, the date they had always planned to retire. He decided to sell.

Lorin was tending the store alone the day two men representing Macleods Hardware entered. They indicated interest in buying one of the Floyd’s Furniture buildings. They left for lunch indicating they would return, and Lorin quickly found his father. Floyd was very interested, and the north store building was purchased in 1965. Not long after, Leland Prince negotiated the sale of the second building, and Floyd’s Furniture closed on 20 October 1970.[49] It was like selling his heart. Steadying himself, Floyd realized that his heart belonged to his family, his church, and his community. Floyd and Clarice were looking to the future, not the past.

Floyd and Clarice entered the LDS mission home in Hawaii on 8 January 1972. Floyd’s first sentence in his mission journal reads, “It is glorious to be here.”[50] He and Clarice would later serve as the first mission couple in Taiwan.

Notes

[1] Kyvig, Daily Life, 257. Also C. P. Stacey, “Second World War (WWII),” in The Canadian Encyclopedia, accessed 18 January 2016, http://

[2] Shaw, Chief Mountain Country, 1:7, 38.

[3] V. A. Wood, The Alberta Temple, 18.

[4] Statistics Canada, Cardston County, Alberta (Code 4803001) and Alberta (Code 48) (table), Census Profile, 2011 Census, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-316-XWE, Ottawa,

http://

[5] V. A. Wood, The Alberta Temple, 25–27.

[6] David L. Innes and H. Dale Lowry, Lee’s Creek (Cardston, AB: Innes & Lowry, 2001), 6.

[7] Chief Mountain Country, 3:102.

[8] “V-E Day Program,” Cardston News, 8 May 1945.

[9] Advertisement, Cardston News, 16 November 1937.

[10] Chief Mountain Country, 2:36–37, 1:479. Also Shaw, Chief Mountain Country, 1:479. David D. Spencer was the older brother of Mark V. Spencer, sons of Mark Spencer and Janette James-Spencer. Also Floyd Godfrey, “Floyd’s Furniture,” in “Life Stories” file of undated, handwritten stories from the life of Floyd Godfrey. See Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 1982.

[11] Figures vary in different documents. In “Floyd’s Furniture,” from his “Life Stories,” the amounts borrowed were $1,500. In Floyd Godfrey’s oral history, the figure was $1,800 from his father and $1,000 from the bank. Totals thus ranged from $2,800 to $3,000.

[12] Floyd Godfrey, oral history.

[13] Wartime Prices and Trade Board, 7 March 1946, Order 414. Also Department of Trade and Industry, Government of the Province of Alberta, License H 1040, Floyd Godfrey (Floyd’s Furniture), Godfrey Family Papers.

[14] Cardston News, 21 March 1946, 8.

[15] Advertisement, Cardston News, 14 and 21 March 1946

[16] Lorin C. Godfrey to author, 8 April 2014, in author’s possession. Also Shaw, Chief Mountain Country, 429.

[17] Lorin C. Godfrey to author, 4 April 2014. Godfrey Family Papers, in author’s possession. Also Chief Mountain Country, 2:326–27.

[18] Advertisement, Cardston News, 29 July 1954, 1.

[19] A “Bed Chesterfield” is a fold-out sofa with a mattress. See Cardston News, 11 April 1946, 1. Also Floyd Godfrey, oral history.

[20] Floyd Godfrey, “Floyd’s Furniture,” in “Life Stories,” file of undated handwritten stories from the life of Floyd Godfrey.

[21] Lorin C. Godfrey, “A Touch of History,” July 2008, Floyd and Clarice Godfrey Family Reunion presentation, Godfrey Family Papers. Gordon S. Brewerton was the builder who constructed the first motion picture theaters in Cardston—the Mayfair and Roxy theatres. At the time of this transaction he was also the Alberta Stake president, the Church authority in the region. Chief Mountain Country, 3:231–33.

[22] Cardston News, 13 January 1955, 1.

[23] “Godfreys in Bermuda,” unidentified newspaper clipping from the files of Floyd Godfrey, Godfrey Family Papers.

[24] “Agreement,” contract between the Mayfair Theatres and Floyd Godfrey, 2 May 1961, Floyd’s Furniture Files, Godfrey Family History Papers. Floyd Godfrey, “Floyd’s Furniture.”

[25] Shaw, Chief Mountain Country, 327, 510–11. Also Chief Mountain Country, 2:299–300.

[26] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 31–33. In 1982, he reported these figures as totaling $20,000. His 1977 interview reported the totals at $21,000 to $22,000, 5.

[27] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 5.

[28] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 16–17.

[29] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 42.

[30] See Donica Belisle, Retail Nation: Department Stores and the Making of Modern Canada (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2011). In 1999, Eatons was purchased by Sears.

[31] “Application for Building Permit, Of the Town of Cardston,” 26 August 1958, signed by Clarice C. Godfrey and initialed by Floyd Godfrey, Godfrey Family Papers.

[32] There is a discrepancy in the oral histories of Floyd Godfrey in that he states “Bishop Burton” was a part of these transactions. In the “Biological Register of General Church Officers,” there was no “Burton” at the helm when these transactions took place. Lorin Godfrey, Floyd’s second son, who worked extensively with his father, reported “with certainty” it was Joseph L. Wirthlin as presiding bishop. Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 4:1631–51. Also Lorin C. Godfrey to author, 8 April 2014, Godfrey Family Papers.

[33] The order of 3,100 chairs at $6.35 would have resulted in a wholesale purchase price of $19,685.

[34] Floyd Godfrey, “Floyd’s Furniture,” in “Life Stories,” file of undated handwritten stories from the life of Floyd Godfrey.

[35] Floyd Godfrey, 1968 accounting book in which Floyd scratched estimates, diagrams, and possible sales, Godfrey Family Papers.

[36] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 1982, 47.

[37] Dahl Leavitt to Floyd Godfrey, April 1988, 82nd Birthday Celebration Collection, loose-leaf notebook in the Godfrey Family papers.

[38] Floyd Godfrey, “Floyd’s Furniture,” in “Life Stories,” file of undated handwritten stories from the life of Floyd Godfrey, Godfrey Family Papers.

[39] Floyd’s Furniture and Sunshine Industries were the first to have television receivers for sale in the area. Sunshine Industries was owned by Wilburn Van Orman, who owned a store along the Waterton Highway selling propane, appliances, and garage service.

[40] Lynn Sommerfelt to Floyd Godfrey, 13 March 1988, 82nd Birthday Celebration Collection, loose-leaf notebook in the Godfrey Family Papers.

[41] Floyd Godfrey, oral history.

[42] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 48–49.

[43] Donald G. Godfrey, “The Ugliest Chesterfield in the World,” in Seeds, Faith & Family History (Queen Creek, AZ: Chrisdon Communications, 2013), 24–26.

[44] This is Max Pitcher’s Fast Freight, which delivered goods to Calgary from the neighboring cities.

[45] Lorin Godfrey, “A Touch of History,” July 2008. Floyd and Clarice Godfrey family reunion presentation. Godfrey Family Papers.

[46] Ken married A. Naone Mason of Tremonton, Utah, on 27 December 1951; Arlene married Paul D. Payne of Mountain View, Alberta, on 25 January 1951; Marilyn married Eddie J. Ockey of Beazer, Alberta, on 8 September 1956; and Lorin married Ann Van Orman on 28 March 1956.

[47] Floyd Godfrey, “Floyd’s Furniture,” in “Life Stories,” file of undated handwritten stories from the life of Floyd Godfrey.

[48] “Floyd’s Furniture Net Earnings, 1948–1970,” Godfrey Family Papers.

[49] Clarice Card Godfrey to Melva Card Witbeck, 15 October 1970, Godfrey Family Papers.

[50] Missionary Journal of Floyd and Clarice Godfrey, 8 January 1972, 1, Godfrey Family Papers.