Service in Cardston

Donald G. Godfrey, "Service in Cardston," in In Their Footsteps: Mormon Pioneers of Faith (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 315–334.

The town of Cardston grew from the philosophical service traditions of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Dedication to the LDS Church meant dedication and involvement in one’s community. Local Church officers served, and still serve, without financial compensation.[1] While believing strongly in the separation of church and state, members were encouraged to be involved in all kinds of government and civic affairs. Even though Cardston and southern Alberta had a limited industrial base, they shipped cattle and crops across Canada and around the world. One of their primary exports became human talent. It spread across Canada and into LDS leadership. Those in the general leadership of the Church from Cardston included N. Eldon Tanner and Hugh B. Brown in the First Presidency; Robert E. Sackley and William R. Walker in the Quorum of Seventy; Elaine Low Jack, Relief Society General President; and Ardeth Greene Kapp, Young Women General President. Cardston’s famous citizens, those not associated with the LDS Church, included Herman Linder, Canadian rodeo champion; James Gladston, Canadian senator; George Woolf, jockey of the famous racehorse Seabiscuit; Fay Wray, King Kong movie star; and Rose Marie Reid, fashion designer—just to name a few. Many people from the area served as local mayors, state governors representatives in the House of Parliament and Congress, and presidential cabinet members, as well as in provincial legislative assemblies and courts.[2] Throughout Church history, members have pledged their time and talents, serving with integrity and honesty and working together for the mutual benefit of their Church, towns, and countries. They were taught to support leadership and each other for the greater good and to not give in to the temptations of ego and notoriety.

Just a few years after Floyd and Clarice Godfrey’s marriage, and with two children at home, Floyd was appointed as a volunteer Magrath fireman.[3] Later on, he ran in his first Cardston public election for the school board. They then had been married fifteen years, with four school-aged children: Kenneth (17), Arlene (16), Marilyn (12), and Lorin (11), with a fifth child on the way. The family survived through the Great Depression and World War II by moving from Magrath to Cardston in hopes of improved opportunities. Ambitious entrepreneurs, they started their own furniture business. In 1945, Germany surrendered, and the United States dropped atomic bombs over Japan, forcing its surrender. Before all this, the children in the Cardston schools had practiced war drills, had watched the Canadian Air Force planes scramble over their town at night practicing, had participated in food rationing, and had wholeheartedly supported the war efforts. Life would never be the same as it moved from the Great Depression and World War II, but it would improve. It was a time of change and service.

Cardston School District

It was February 1944 when Floyd agreed to run for his first elective office. He was campaigning for the school board ballot with Percy C. Gregson, Brigham Y. Low, and Lyman M. Rasmussen.[4] Their campaign consisted of a few newspaper ads and word of mouth. They promoted a progressive, well-managed, and well-equipped school system cooperating with “parents, students, and taxpayers” with “no untried and expensive experiments.” They were a slate of men well known in town, and all four were elected.[5]

The initial Cardston School District had been organized in 1894, shortly after the first pioneers arrived. It came under the rule of the Northwest Territories, and by 1944, the province of Alberta had control. The business of the school board was to draft an inclusion agreement with the St. Mary’s Division, giving community schools a greater share in available funds and grants. In other words, the schools of Cardston were in financial difficulty.

Multiple rural schools popping up throughout the region had become a financial drain with a limited tax base. Local ranchers were moving their children into Cardston, where the student population was climbing and broader educational programs were available. Growing families and returning soldiers starting families all stressed the school budgets. It had become difficult for the town to pay its portion of the costs. When Floyd was elected to the school board, Lyman Rasmussen was chairperson. Floyd followed as the next school board chairperson, under which capacity he served for several years.[6]

The new board’s charge was to merge fifty-three small rural schools out of the St. Mary’s River Division and create “nine centralized schools at Cardston, Hillspring, Glenwood, Mountain View, Del Bonita and Magrath.” Floyd wrote that this reorganization was controversial and “took many, many long meetings and travel.”[7] But with the cooperative representation of John S. Smith, a Cardston resident and financier, Floyd and John took the train to Edmonton to present their case in the provincial capital. Their position was simply that combining rural and town schools would provide a better education at a lower cost. The minister of education and the Alberta premier were supportive of Floyd and John’s position. The Cardston schools were consolidated, and “education seemed to bounce ahead.” The work of Smith, Godfrey, and Cardston board members remains the conceptual foundation of today’s Westwood School Division #74.[8]

Lions Club and Chamber of Commerce

It was good citizenry that drew people into the public service organizations. By 1946, Floyd was a school board member and would soon become a director of the Cardston Lions Club International, a member of the Rotary Club, and a member of the Chamber of Commerce. The Cardston Lions Club was organized in November 1940 with the motto “We Serve.” They promoted citizenship, good government, unification of people in friendship, and service without personal or financial gain. During WWII, the Lions of Cardston raised money for the Red Cross and the War Service Committee. By 1942, the Lions had committed to building a permanent community park along Lee Creek and a swimming pool close to the center of town. Both have stood for more than six decades. [9]

The Cardston Chamber of Commerce was originally known as the Board of Trade. In 1948, the name changed to the Chamber of Commerce to promote trade and economic growth.[10] Floyd’s brother Bert was a member of the board when he encouraged Floyd and Clarice’s move from Magrath to Cardston. Years later, the new Chamber brought the town merchants together, including Floyd’s Furniture, organizing and sponsoring economic development projects. There were blood-donation drives, “Paint Up, Clean Up, Fix Up” campaigns, and ever-present sporting events. Participation in these events attracted attention to the activities and traffic in the stores.[11] Over the years, Floyd’s Furniture was listed among the various sponsors. In 1948 and 1953, art exhibits of school, local, and native artists were on display in the front window of Floyd’s Furniture.[12] The Cardston 3rd Ward Explorers basketball team, coached by Ken Godfrey, brought home the winning trophy from Idaho. Coach Godfrey reported that the boys had won the sportsmanship trophy as well but were allowed to bring just one home. This basketball trophy too appeared in the window of Floyd’s Furniture.[13] Floyd’s Furniture, along with all the Main Street merchants, donated what they could to community development.

In 1962, Floyd was succeeded by Lloyd Gregson as president of the Chamber of Commerce, and Floyd became the planner of his most memorable community service events: “Silver Dollar Days” and “Crazy Days.” Gregson was a friend of Floyd’s, was the owner of the Foodland, and was later the elders quorum president in the Cardston Fifth Ward with Bishop Godfrey, so they worked well together. The “Silver Dollar Days” featured seventeen thousand legal tender silver dollars that were shipped to the Cardston Royal Bank. Merchants purchased these silver dollars, and they gave the silver dollars as change during a week of special sales. In a matter of three weeks, the coins were gone. The campaign stimulated business, the result illustrating “how fast money moves around.” During “Crazy Days,” merchants blacked out their windows and opened stores later than usual, offering discounted screwball sales items, pulling in customers. Men dressed as women, Milton Berle style, and pranced up and down the streets during the Cardston Rodeo Day parades, embarrassing every merchant’s teenage son or daughter.[14]

The chamber’s efforts saw the official opening of the new main street bridge over Lee’s Creek in 1962.[15] South of the business district, it crossed over the creek on the southern leg of Alberta Highway 2 that ran from Grimshaw in northern Alberta and on to Calgary and Cardston, then to the borderline at Carway, Alberta, where it became the historic US Highway 89 south into Montana. It was a small bridge in a small town, but it meant a lot to the community’s development along this historic drive. John Diefenbaker, the Canadian prime minister, and Hugh B. Brown, a member of the First Presidency of the Church and former Cardston resident, were invited to the celebration of Cardston’s seventy-fifth anniversary in July 1962. Brown’s wife, Zina, was one of the first children born in Cardston, and her father was Charles Ora Card.[16] Diefenbaker and the Browns were escorted to the Social Center in a horse-drawn carriage. Seated on the rostrum, Floyd, as president of the Chamber, was to conduct the meeting. He whispered to Brown, who was sitting beside him, “Brother Brown would you speak first?” Brown responded, “Brother Godfrey, nobody is ahead of the Prime Minister.” Floyd immediately recognized the priority of dignitaries and introduced the Prime Minister, declaring that President Brown “set me straight.”[17] It was an interesting learning curve for a new civic leader.

Cardston Town Council

On 24 February 1955, Floyd was nominated for the first time for a seat on the Cardston town council. He was on the slate with Albert Widmer, also running for a council position, and Henry H. Atkins, who was running for mayor.[18] They were up against the incumbents, Mayor Joseph S. Low and his councilors William G. Bennett and Willis A. Pitcher.[19] Both slates offered considerable community experience, and it was predicted to be a close election.[20] Low had served for two years and had been a councilman for eight. The incumbent’s push was a continuance “for sound financial and progressive civic government.” The competition, on the other hand, were all comparative newcomers. Atkins served on the town council before and was a successful merchant with an interest in public affairs and municipal business. Widmer and Floyd were completely new candidates. As a councilman nominee, Floyd promoted himself as active in the community, with years of service on the school board and as chair of the board. Widmer campaigned as a livewire citizen with experience as proprietor of the Center Service Company. The overall push for the Atkins, Widmer, and Godfrey campaign ticket was a “Vote for Natural Gas.”[21] The new slate swept the election. The Cardston voters overwhelmingly wanted the Canadian Western Natural Gas Company as a utility. Now, with a new mayor and council, a significant step began on 17 March 1955, when the last reading of the gas franchise bill was read and passed by the town council. Ironically, it was the last act of Mayor Low and the retiring council before the new officers were sworn in. The laying of the gas line between Lethbridge and Cardston began in the spring.[22] Floyd was appointed to the water, sewer, finances, and public welfare committees. He served three terms under Mayors Pitcher (1957–58) and Lyle Holland (1959–60). In 1961, Floyd ran for mayor but was soundly defeated by Robert Dennis Burt (1961–67). “It didn’t bother me much . . . of course no one ever likes to get beat,” but Floyd enjoyed serving. He loved his community.[23] In 1970, Floyd retired, took a hiatus from public service, and sold Floyd’s Furniture. A year later, he and Clarice were on their way to Taiwan to serve an LDS mission there in the Republic of China (see chapter 12). Seven years later, he would be convinced to enter the political race again as a candidate for mayor.[24]

Cardston Mayor

Nomination day for Cardston was on 19 October 1977. There was a flurry of activity that resulted in eighteen candidates vying for six town council positions and two candidates for mayor. Floyd Godfrey and Robert W. Russell were in the mayoral race.[25]

Russell was a noted physician.[26] He had served three terms on the town council and was a current member. His experience in former town councils had been in the late 1950s. Floyd was seventy-one, retired from twenty-five years in the furniture business and public service. He had recently spent almost two years in Taiwan, the Republic of China. He wanted to keep busy and return basically as a busy volunteer. He was anxious and a little uncertain when asked to run, but he made it “a matter of prayer,” after which he moved boldly forward.[27]

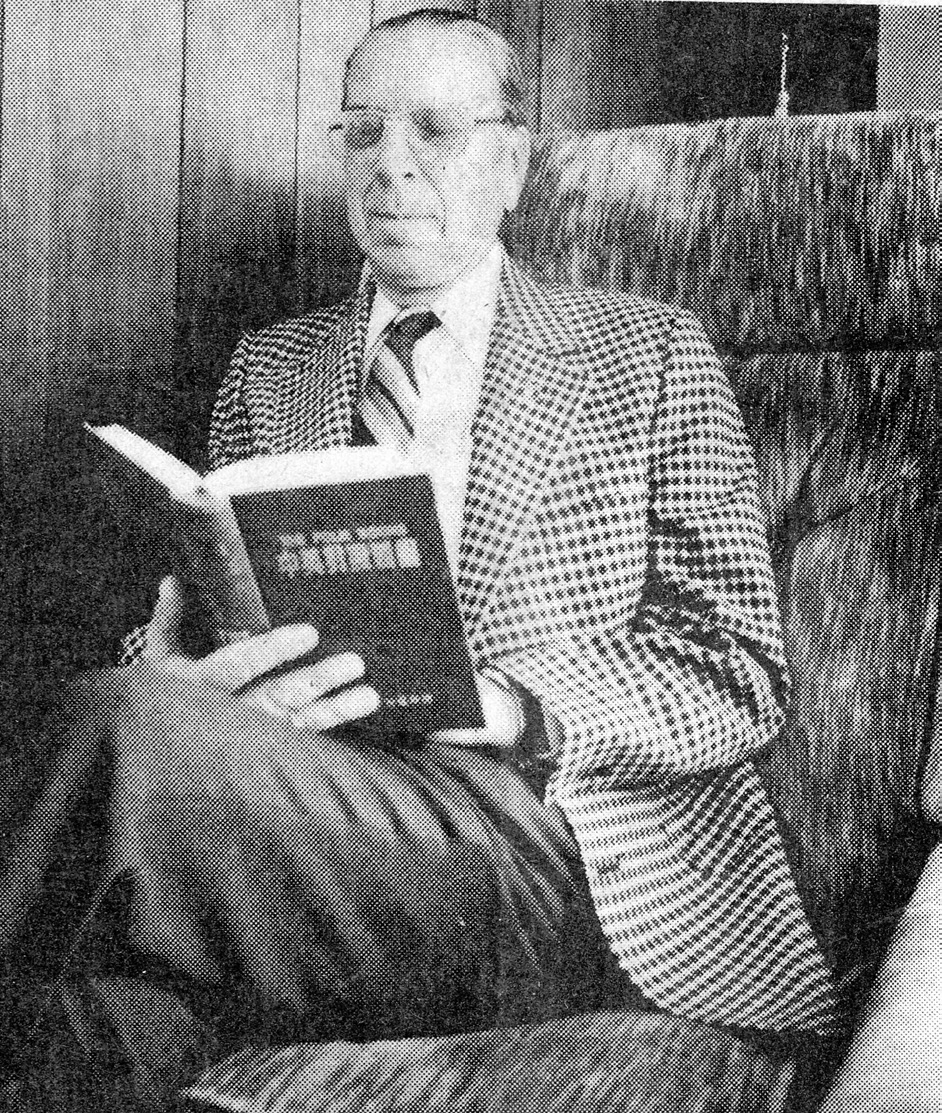

Both candidates’ platforms expressed concern over water, sewer, taxes, new development, and the debts left by the government’s financial grants. The town’s airstrip and agricultural facility had been constructed with such project grants to promote employment. However, at times, local autonomy was not always possible. Even when communities satisfied their portion of the grant, they were still “forced to pay interest until the end of the loan term.”[28] Floyd’s campaign differed only slightly from Russell’s, adding desires to expand industry, improve communications, and upgrade the library. Speaking before the Cardston Rotary Club, he stressed the need for economic growth, tourism, job creation, library upgrades, improved communication, and closer relations with Glacier and Waterton parks, Macleod, Pincher Creek, the Native people, and the municipal district. He declared, “My life has been service to this community, Church and individuals. I have no axe to grind. I give you my time and experience.”[29] His position was one of creating industry to trigger employment for the town’s young people, many of whom moved away reluctantly because there was no work. “If we work together and make the town into a tourist destination, it could really grow,” Floyd declared. Elected one of the first full-time mayors, he never passed up an opportunity to beautify the town and preserve its history. He wanted to see the town library expand into a regional center. “We need everyone working on the project,” he urged. Perhaps the only significant difference between the two candidates was Russell’s promise to “make the time commitment to serve the community,” implying time away from his medical practice while Floyd’s was to devote “FULL TIME, I have the EXPERIENCE.”[30] An interesting photo of both candidates appeared in the Lethbridge Herald, with Russell reading a medical file in his clinic and Floyd at home in his easy chair, reading the words of Confucius with a sly grin on his face.

On 26 October 1977, Cardston’s turnout “broke all previous records,” with virtually 90 percent of voters casting a ballot. Floyd Godfrey was elected to be the eighty-sixth mayor of Cardston.[31] Joining him on the town council were Rhea Jensen, Laurier J. Vadnais, Dale Lowry, Delbert L. Steed, D. Dahl Leavitt, and Lowell Hartley.[32]

The first order of town business was to become acquainted with the work of the prior council, then complete projects in progress with a smooth transition to new leadership. Primary among the ongoing projects were the spiraling costs of the water system and the effects of the new bypass road on tourism. Even before the new council was organized, Floyd reached out to the neighboring communities. He met with their leadership and opened lines of communication. He interviewed each council member, assessing backgrounds and interests for the various committees and assignments. Perhaps one of the most important of Floyd’s mayoral leadership qualities was this assessment of his council and their appointments to various project committees, standing committees, and committee chairs. Once appointments were made, Mayor Godfrey let them do the work and got out of the way. He communicated with them, and when reports were turned into the council, he supported the committee recommendations. He did not seek the limelight or credit, and he pushed for progress and resolution.[33]

Floyd Reading Confucius, mayoral campaign photo. Courtesy of Godfrey Family Files.

Floyd Reading Confucius, mayoral campaign photo. Courtesy of Godfrey Family Files.

There were a variety of community activities that demanded the mayor’s presence. One was the ribbon-cutting ceremony for the Cardston Mall, which opened the summer after the elections. Dale Tagg, who managed the anchor IGA grocery store, attended the debut. He had once worked at Floyd’s Furniture, so there was a strong friendship already existing. The mall featured the IGA, Robinson’s Clothing, Doug’s Sports, and Topsy Fashion. It was expected to be the center of community shopping. However, plans for expansion were derailed years later with the opening of the Extra Foods store, and consumer traffic moved again. Mayor Godfrey was a strong supporter of “Hire-a-Student” week. It was an employment opportunity matching young people with jobs. The program brought together financial support from the federal, provincial, and local governments to help the youth find work. It linked employers to potential employees and assisted students in the particulars of writing a résumé and landing a job. In 1981, the mayor presented the Cardston Library Board with a Rotary Club check for $3,500 ($8,835), a partial payment of the total $10,000 ($25,244) committed the new library building. Plans for expansion of the library grew exponentially when the mayor and council decided to renovate the old town office building, creating much needed space for a new library.[34] A new town office was built, along with the reconstruction and development of the former community social center. The town council was temporarily housed in the provincial building on south Main Street as construction progressed.

From the beginning, Mayor Godfrey was described as a go-getter. He was actively engaged with every council committee, encouraging and “forwarding the cause of a better Cardston.”[35] His communications and “Letters to the Editor” of the Westwind News continually encouraged the involvement of the electorate. “Now is the time, Let’s do it,” he proclaimed. He wanted to repair Cardston homes and purchase property and paint from local merchants. “Let’s even out our own economy. Our [Canadian dollar] might be going down, but our determination and working ability is going up. . . . This town has strength, character and beauty. Let’s be part of it and do it NOW.”[36] A year later, Mayor Godfrey gave a similar message, along with a public report on town council activities, and concluded, “I see a Cardston with people eager to help. We have great youth, let us support them. They are the Cardston of tomorrow.”[37] The mayor spoke at the Treaty 7 banquet, emphasizing the need for constructive relationships between Cardston and the Blood Indian Reserve. He stated that “it is only through friendship and being good neighbors that this goal will ever be reached.”[38]

Mayor Godfrey traveled extensively throughout Alberta, cementing relationships and bringing new business to the town. With Clarice at his side, he was on the road to Calgary working with Caravan Industries, which had seemed interested in opening a small factory in Cardston. He made trips to Edmonton, where he met with Alberta provincial ministers. During his meetings with the minister of environment, they focused on the controversy over a much-needed sewage treatment plant, as well as erosion of the Lee’s Creek waterbed and the Goose Lake Reservoir. In his meeting with the minister of transportation, they focused on the need for road improvements, the Cardston bypass, and possible bus service for the town. In his meeting with the minister of education, they dealt with representation on the local school board. Mayor Godfrey pitched to the minister of finance to acquire assistance in financing a clothing factory for Cardston. Finally, in his meetings with Premier Lockheed, the two men focused on communication and overall government. He attended small-town association meetings working to reach out. “All listened and promised to follow through.”[39]

Controversial Politics

No political organization is ever without its issues. Water supply, flood control, and sewer lines were among the early attention-getters in Floyd’s administration. A 1979 study of Cardston’s key water resource control had landowners in an uproar at the idea that the Goose Lake water reserves on the Lee’s Creek basin might be dammed.[40] Those in favor felt it would allow greater flood control and “give the town a greater reservoir capacity.” The system that was then in place gave Cardston “only eight weeks of water” in case of drought or a hard frost. The issue was further clouded by opponents who objected to the work of the environmentalists seeking to redirect the creek in efforts to cope with flood control. The council had commissioned a study fifteen months earlier and stated that a report from the engineers would be made public next month.[41] Sensitivity to the environment and the needs of the town kept the search for water at the forefront. The town finally commissioned Stanley Associates Engineering from Lethbridge to study and analyze costs.

The conflict over sewer treatment plants involved examining alternative updated methods of sewage treatment and the selection of a suitable site for the plant itself.[42] There was concern about keeping the citizenry fully informed and about the potential devaluation of property “less than a block away from a residential area.” The citizens claimed they had not been informed. The council was hesitant to delay construction due to rising costs. However, there was delay and the plant was relocated.[43]

A new water resource and treatment plant was dedicated in 1978 at the west end of town. It pleased the environmentalists who wanted the Lee’s Creek Basin and Goose Lake to be pristine. It held the potential for town growth, providing water for five thousand. The town had room to attract new residents, as its current population of 3,500 residents had been stable over the years.

The sewage treatment plant was christened on the east end of town in undeveloped flat land. Part of this development included the creation of a ballpark watered with treated effluent from the plant.

Federal Government, Cardston, and the Blood Tribe

The most significant conflict occurred in July 1980 when Cardston was caught in the middle of the federal government and the Blood Tribe over disputed land agreements. Floyd received a late-night telephone call from local Mounted Police: “Sorry to wake you up at this hour, but we have troubles . . . we need you right away.” There had been rumors of a group preparing for a conflict, “but perhaps they had something to say to him and he should listen.” The First Nations people’s claim was that Cardston was positioned on native land, and they wanted the Mormons out. The listening session escalated, dragged into hours, and then into days of arbitration with police, government officials, and First Nations people. Their tempers were prepared for violence, and the conflict came to a head when Highway 5, the tourist and local route to Waterton National Park and communities west, was blockaded with construction equipment by the tribe. Cardston locals knew their way through town and accessed Highway 5 by skirting the protestors from the road north of the rodeo grounds. The tourists heading to the park, on the other hand, were mystified and were unaware of any detour.

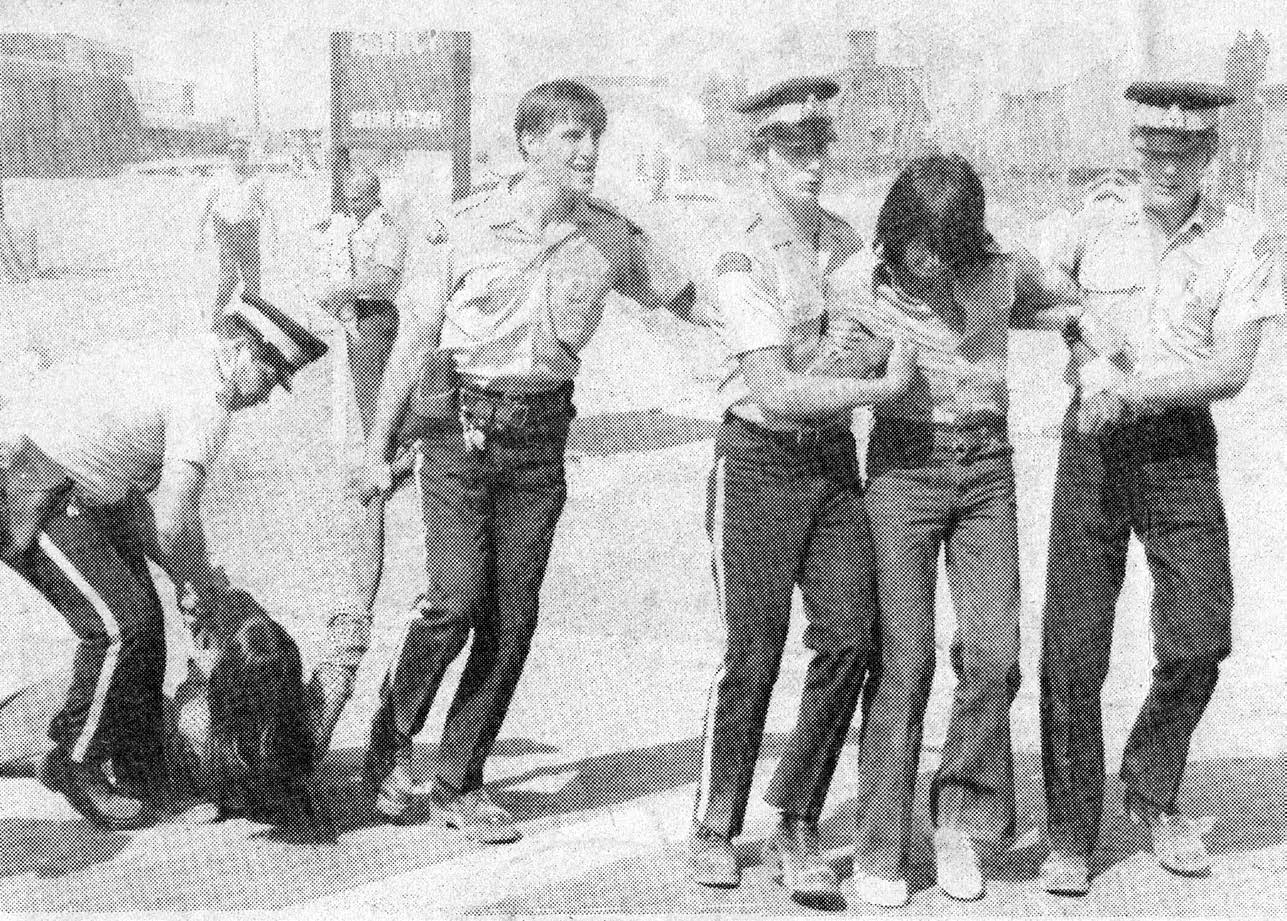

First Nations protest, Cardston Chronicle, 29 July 1980. Courtesy of Mayor Floyd Godfrey Files.

First Nations protest, Cardston Chronicle, 29 July 1980. Courtesy of Mayor Floyd Godfrey Files.

The protest blocked the Esso gas station emblazoned with signs reading “Mormons Go Home,” and “You’ve Taken More Than Enough, White Man.” News reporters arrived early on the scene in the morning to film the scene. Mayor Godfrey wondered where they had learned of the dispute so early, asking, “How did they know?”[44] The answer was that the protestors had invited the press. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police were called, and detachments from Cardston and Lethbridge gathered to remove the roadblocks and disperse the crowd. The protesters refused, scuffles broke out, Mounties made arrests, and peace was restored.[45] John Munro, federal minister for Indian affairs, met with the Blood Band Council a week later in a closed meeting in Standoff at the headquarters of the tribe, located twenty miles north of Cardston. The Blood Band expressed six concerns: treaties, treatment at the Carway, the US border crossing, treatment in Cardston schools, treatment in hospitals, and the police dogs. Canadian federal authorities and the Cardston town council pointed to the 1883 Treaty 7, which established the reservation borders and noted that the Mormon settlers had not appeared until five years later, in 1887. Mayor Godfrey encouraged law and order in the resolution of the conflict, suggesting to the federal government that “Commitments made by Federal, Provincial or Municipal bodies, as well as those made by the Blood Band, should be honored . . . and would support the Blood Indians request of the Federal Government to have all commitment made to them honored.”[46] The mayor had executed his due diligence and immediately contacted Church headquarters, resulting in President N. Eldon Tanner sending records and titles that documented the property around Cardston.[47] He had the proof but did not need to use it. His response stressed that settling controversy needed to be within the boundaries of the law. Mayor Godfrey invited the Blood chief, Shot Both Sides, and members of the Blood Council to meet with the Cardston town council to air their dissatisfaction regarding treatment in schools and hospitals, but there was no reply.[48] The treatment of border agents was outside local control. A task force was immediately established to gather the facts and help resolve differences of opinion. The goals of the task force were to “generate understanding between all people concerned, provide information relative to education, hospitals and business concerns; and insure the safety, security and Human Rights necessary for the growth and cultural development of all people in this area.”[49]

Floyd always felt he had had a good relationship with the Blood Tribe. He seemed to recognize that changing their way of life “to the white man’s way of life was very difficult for them” and not always what they wanted.[50] He knew they had been disadvantaged from the beginning by the American whiskey traders who smuggled alcohol into southern Alberta, long before the Mormons ever immigrated. Floyd found the First Nations people, who had traded at Floyd’s Furniture, to be “very good people.” He felt like he had friends on the reservation, so he was totally surprised and frightened when his life was threatened during the protests. The Mounties suggested he might want to consider a vacation until the discontent abated.[51]

Dr. Roy Spackman, the medical doctor treating the protestors, responded to the charge of aggressive canine behavior, calling the accusations “radical and misinformed” and created to attract media attention and enlist sympathy. Dr. Spackman reported that contrary to published newspaper reports, “there were no significant injuries” to anyone, and that there had been “no dog bites, no broken bones and no beatings.” He called attention to the fact that the “beaten and bruised women on T.V. was a misleading charade of the highest order.” The only significant injuries were “to the RCMP [Royal Canadian Mounted Police], and of this, the media has said nothing.” He challenged the media to report truth.[52]

As in most media-generated events, the controversy subsided. The concerned parties met in discussion and the press moved on to other events.

Legacies of the Mayor

The real challenges of Mayor Godfrey’s service began in placing the right person in the right place. Floyd was happy with his appointments. “They worked hard and long on their projects,” and he supported their actions. In the first year, the new water system was completed. The mayor’s only concern was the flow of water in dry years and cold winter months. He was concerned that provincial environmentalists, without notifying the town government, had started clearing the Lee’s Creek watershed, which was the town’s primary water source. After heated discussions, the town decided to monitor the creek and survey the base, which was accomplished “at no cost.” Water was considered the town’s most valuable commodity. With the cooperation of later authorities, workers were able to bring the erosion of the creek bed under control. The authorities paid for 75 percent of the costs, which included the costs for the Third Avenue Bridge. Roadwork included working on the town bypass, with a parking area for heavy trucks. Workers completed a large parking lot behind the post office. These workers also reinforced roads along the creek, supporting a part of flood control. Highway 2 improvements through the area facilitated travel between Calgary and Helena. As a part of this project, workers installed new lights along Main Street from the top of the south hill to the top of the north hill—again at no cost to the town. Workers also upgraded the roads to Fort Macleod and Waterton. They also constructed a new swimming pool, and the mayor hoped to see a solar panel on the roof of the building to heat the pool so that it could be utilized in the winter. Floyd envisioned it as part of the school sports curriculum. A revitalized Lions Park created a multiuse park for sports, community, and school. A new campground, patterned after the Glacier and Waterton centers, was opened on the south side of Lee’s Creek. Tourism was considered a must, and a tourist hut provided local information for visitors.[53] However, progress on anything new slowed due to accelerating prices.

Mayor Godfrey traveled throughout the province, lobbying for cooperation among Cardston, the Waterton-Glacier International Peace Parks, Fort Macleod, Pincher Creek, and the surrounding area. He pleaded with them, “We sit between two parks and we should try to do something” to take advantage of this location. The council moved the town office to the Provincial Building while the library and the Social Hall were renovated into a new Town Center. He lobbied for small business development.[54]

From Town Service to Home Service

Mayor Godfrey might have run for another term, but life had other plans. In all of Floyd’s community and Church service assignments, his wife, Clarice, had been his ally at home and in his travels. In each of the official photos they were side-by-side, and if one looked closely, he or she could see that the two were holding hands. If Floyd traveled, she went with him, and she was always pleased when visiting dignitaries recognized her, asking, “How are you, Mrs. Godfrey?”[55] When Floyd’s obligations took him away from home, she never complained. She was supportive and was always there for Floyd. In fact, she was the inspiration of his life. When Floyd was reluctant to take on an assignment or step forward, she prodded him, saying, “You can do it; . . . you can do it.” This encouragement was a key factor in Floyd’s activities.[56]

It was following their Taiwan mission and during Floyd’s mayoral occupation when Clarice’s health began to deteriorate rapidly. She was a lifelong lover of sweets and suffered from high blood pressure and hardening of her arteries. She had undergone several surgeries, all leaving her body weak and in poor health.

Her parents had suffered from dementia. Medical care facilities were unavailable, and her father, George, was sent to what today is called the Centennial Centre for Mental Health and Brain Injury in Panoka, Alberta, for the last years of his life. This was painful for Clarice, who feared that this, too, was her fate. When her mother began to suffer the same symptoms, Floyd and Clarice converted the garage into a small one-bedroom home next door so that Clarice could care for her. It was a challenge, and she loved her mother but feared for herself. As Clarice’s health waned, Floyd felt that his primary responsibility was to her. He left public service to care for his wife as she had cared for her parents. Clarice passed away on 16 December 1980.

Notes

[1] Bruce Douglas Porter, “Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,” in Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 1:277, 281.

[2] Porter, “Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,” Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 1:285–86. See also Ernest G. Mardon and Austin A. Mardon, Alberta Mormon Politicians (Edmonton: Golden Meteorite Press, 1992), 61–74; G. Homer Durham, N. Eldon Tanner His Life and Service, 50–90; Eugene E. Campbell and Richard D. Poll, Hugh B. Brown: His Life and Thought, 104–12; Shaw, “Government: Local, Provincial, Federal,” in Chief Mountain Country, 3:159–86; and Shaw, “Citizens & Celebrities,” in Chief Mountain Country, 3:229–64.

[3] Minutes of the Meeting of the Magrath Town Council, 15 April 1935, Magrath Museum Files.

[4] Gregson founded the Foodland Grocery in 1940, Low owned a large ranch on Lee’s Creek, and Rasmussen was a part owner in the Cardston Trading Company. Shaw, Chief Mountain Country, 327, 389–90. See also Shaw, Chief Mountain Country, 2:298–99, 426–27.

[5] See “Ballots,” “Vote,” and “Election Results,” Cardston News, 10 and 14 February 1944, n.p.

[6] There are two Lyman Merrill Rasmussens listed in Shaw, Chief Mountain Country, 2:426–27. This is likely the son of the pioneers Lyman and Annie. Lyman Sr. passed away on 7 November 1947.

[7] Shaw, Chief Mountain Country, 2:51–52; See also Shaw, Chief Mountain Country, 2:58–59; and “School Board,” Floyd Godfrey notes and the Cardston Inclusion Agreement, Godfrey Family Papers.

[8] Shaw, Chief Mountain Country, 2:51. See also “Smith Addresses Home-School Meet,” Lethbridge Herald (16 March 1948), 5. John S. Smith was a businessman of considerable wealth and influence. He served on the St. Mary’s Divisional School Board and later the Cardston School Board for twenty years. Shaw, Chief Mountain Country, 2:472–74. See also Floyd Godfrey, oral history, March 1982.

[9] Shaw, Chief Mountain Country, 2:165–66. See also “Cardston Lions Club Reorganized,” Cardston News, 1 August 1946, 1.

[10] Shaw, Chief Mountain Country, 2:118–22.

[11]“Wanted: 300 Blood Donors,” Cardston News, 22 November 1951, 5. This was repeated in the Cardston News on 24 July 1952, 6. See also advertisements “Beautify Canada by Beautifying Our Community,” Cardston News, 20 May 1948, back page; “Art Exhibit,” 19 February 1948, 2; and “Art Exhibits Held Here,” 5 November 1953, 1; “Explorers Victorious Bring Home Cup,” April 1952. In the “Floyd & Clarice Godfrey Family History: News Clippings,” Godfrey Family Papers.

[12] “Cardston District First Public Art Exhibition,” Cardston News, 18 February 1948, 2. See also “Art Exhibits To be Held Here,” Cardston News, 5 November 1953, 2.

[13] “Explorers Victorious—Bring Home Cup,” Cardston News, 3 April 1952, 1. The Explorers were a boys’ group within the LDS Mutual Improvement Association.

[14] Shaw, Chief Mountain Country, 2:120–1.

[15] “Scene of Official Bridge Opening,” and “Godfrey Heads Temple Chamber,” Cardston News, 1962, n.p., from “News Clippings,” Godfrey Family Papers.

[16] Campbell and Poll, Hugh B. Brown: His Life and Thought, 247.

[17] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, March 1982, 39–40.

[18] “Nominations,” Cardston News, 24 February 1955, 1.

[19] “Vote March 7,” Cardston News, 3 March 1955, 8.

[20] “Interesting and Close Election,” Cardston News, 24 February 1955, 1.

[21] “Vote for Natural Gas,” advertisement, Cardston News, 24 February 1955, 3. See also “Vote March 7,” advertisement, Cardston News, 3 March 1955, 8; and “Build Cardston,” advertisement, Cardston News, 3 March 1955, 3.

[22] “H. H. Atkins New Cardston Mayor” and “Work on Southern Albert Gas Line to Start This Spring,” Cardston News, 10 March 1955, 1. The newspaper campaign advertisements are not clear which team—the incumbents or the newcomers—was the stronger supporter for natural gas. However, the newspaper reports cast the natural gas favor to the Atkins, Widmer, and Godfrey ticket.

[23] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, March 1982, 39–40.

[24] Shaw, Chief Mountain Country, 2:105.

[25] Al Schindler, “Cardston Election Day, October 19th,” Westwind News, 28 September 1977, 4.

[26] Fred N. Spackman, “The Cardston Clinic,” in Shaw, Chief Mountain Country, 2:74.

[27] “LDS Drive Nets Large Voter Turnout,” Church News, 10 December 1977, 7. See also Floyd Godfrey, oral history, March 1982.

[28]“Mayor Concerned Over Government Grants,” Westwind News, 8 November 1978, 2.

[29] Rotary Club Address, October 1977. Draft in Godfrey Family Papers.

[30]“Vote Godfrey for Mayor,” advertisement, Westwind News, 12 October 1977, 3; emphasis in the advertisement.

[31] “Cardston,” Lethbridge Herald, 19 October 1977, from “Floyd & Clarice Godfrey Family History: News Clippings,” Godfrey Family Papers. There is a difference in voter turnout reported between the Lethbridge Herald, which reported “nearly 90 percent,” and the Church News, 10 December 1977, report indicating “an 80 percent voter turnout,” 86th year placard in Godfrey Family Papers.

[32] “Statement of Officer Presiding at Poll Accounting for Ballots—Town of Cardston,” 19 October 1977, copy in Godfrey Family Papers. Al Schindler, “Cardston Election Results,” Westwind News, 26 October 1977, 3.

[33] Rhea Jensen, video history interview, 1996, Godfrey Family Papers.

[34] “Cardston Mall Official Opened by Mayor,” Westwind News, 23 August 1978, 2, 5; see also “Community Support Makes Hire-a-Student Week Success,” Westwind News, 11 July 1979, 3; “Hire-A-Student Program,” Cardston Chronicle, 27 May 1980, 1; and “Rotary Club Makes Presentation to Library,” Cardston Chronicle, 14 October 1980, 1.

[35] Gordon Brinkhurst, “New Mayor a Go Getter,” Westwind News 26 October 1977, 3.

[36] Floyd Godfrey, “Letter to the Editor,” Westwind News, 13 September 1978, 2; emphasis in original.

[37] Floyd Godfrey, “Letter to the Editor: To the People of the Town of Cardston,” Westwind News, 21 February 1979, 12, from “Floyd & Clarice Godfrey Family History: News Clippings.”

[38] “Chamber of Commerce Treaty 7 Banquet,” Westwind News, 2 November 1977, 2. Treaty 7 was one of eleven agreements signed between the First Nations people and Queen Victoria. The agreement basically established today’s Blood Indian Reserve north of Cardston. See also Alexander Morris, The Treaties of Canada with the Indians of Manitoba and the North-West Territories (Toronto; Willing & Williamson, 1880; Toronto: Coles Canadiana, 1971).

[39] Journal of Floyd Godfrey, 5–7 June 1979, Godfrey Family Papers.

[40] “Goose Lake/

[41] Brent Harker, Lethbridge Herald, 31 October 1979, 15, from “Floyd & Clarice Godfrey Family History: News Clippings.”

[42] “Proposal to Town of Cardston for Design Service for New Sewage Treatment Facilities,” 5 December 1977, by Underwood McLellen & Associates.

[43] Gordon Brinkhurst, “Citizen Irate Over Sewage Plans,” Westwind News, 6 June 1979, 3.

[44] Floyd Godfrey Notes & Prose, handwritten notes following the event, untitled and undated, Godfrey Family Papers.

[45] “Tension High Over Weekend in Cardston,” Cardston Chronicle, 29 July 1980, 1, 3.

[46] “Minutes of the Regular Meeting of the Town Council,” 29 July 1980, 3.

[47] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, March 1982.

[48] “Minutes of the Regular Meeting of the Town Council,” 12 August 1980, 5. See also “Minister Meets with Bloods” and “Town of Cardston Makes Declaration,” Cardston Chronicle, 5 August 1980, 1.

[49] “Meeting of the Task Force for Indian Affairs,” Town of Cardston, 21 August 1980.

[50] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, March 1982, 57.

[51] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, March 1982, 57.

[52] R. R. Spackman, “Letter to the Editor,” Lethbridge Herald, republished in the Cardston Chronicle, 26 August 1980, 2.

[53] Floyd Godfrey, “Work of a Council,” Godfrey Family Papers.

[54] “Mayor Report of Activity,” 23 March 1979, handwritten text in Godfrey Family Papers.

[55] Comment from the Alberta premier, in Floyd Godfrey, oral history, March 1982.

[56] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, March 1982, 44–47, 64–65.