Mormons Moving into Southern Alberta

Donald G. Godfrey, "Mormons Moving into Southern Alberta," in In Their Footsteps: Mormon Pioneers of Faith (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 129–172.

The state of Utah and the Cache Valley were settled mostly by the Mormons, who were united in their religious, civic, economic, and cultural values. They were the majority. In contrast, the Mormons heading into Canada found a land far different in culture and people. Nineteenth-century Alberta featured a diverse people with a lively array of multicultural political characteristics. The Mormons would have to learn about them and adjust to their role as citizens in a new land.[1] The first permanent Mormon settlement in Canada would be called Card’s Town, after its founder.

Canadian Northwest Setting

Canada’s Northwest Territories made up a vast region stretching from the Hudson Bay through Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta.[2] It was a wilderness filled with thousands of lakes dotting the Canadian Shield. It featured the waving grassland of rolling prairies and the wind-blown foothills of the Canadian Rocky Mountains. Its resources seemed inexhaustible. The first whites in the territory were French-Canadian trappers. The Hudson’s Bay Company, chartered in Great Britain in 1670, gave these trappers exclusive trading rights to all the rivers of the West, which drained into the Hudson Bay. In this region, the company systematically directed fur trading operations for two hundred years. By 1870, the company had transferred the land to the Dominion of Canada, which had been formed in 1867. Twelve years later, the parliament of Canada had divided the Northwest Territories into the districts (later the provinces) of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba.[3]

An Order in Council of 1881, issued from the House of Commons, provided more incentives for western Canadian settlement. It allowed for land leases up to one hundred thousand acres for twenty-one years at a rental fee of one cent ($0.23) per acre.[4] Canadian Senator Matthew H. Cochrane took advantage. He acquired two ranches in Alberta and a third in British Columbia. In Alberta, his ranches were along the Belly River in southern Alberta, where he would meet Charles Ora Card. His third ranch was near Calgary, in what is now the town of Cochrane.[5] In 1885, Alberta was given one seat in the Canadian House of Commons.[6] Sixteen years before Charles Ora Card’s first trip reached the Rockies, ranchers were already working the land in British Columbia and central Alberta. Farming and agriculture had blossomed on the prairies. By 1886, the railways ferried more immigrants to the area. This railroad construction reached coast-to-coast and funneled more people West.[7] All of these elements caused the Dominion of Canada to rapidly expand. The Order in Council was an aggressively open policy, encouraging settlers into the West. It was into this setting that the new Mormon immigrants came into southern Alberta.

The Northwest Territories were originally populated by the First Nations people of the plains. They knew no borders, following the buffalo herds for their survival. The coming of the fur traders, explorers, whisky traders, and missionaries of all types radically changed their lives,[8] as they were exploited and threatened with extinction. They were denigrated particularly by the white traders from the United States, who came to the area and killed buffalo and sold alcohol. The tribes had always depended on the wildlife for their sustenance, and with the arrival of the trappers and traders, those resources were disappearing.[9] The Canadian government recognized the need to protect the native people, and as a result, they stationed the Northwest Mounted Police in the area.[10] In 1874, small detachments were scattered along the border between Canada and the United States, with headquarters at Fort Macleod, Alberta.

The Canadian Pacific Railway played a vital role in western settlement, moving people east to west just as the Union Pacific in the United States. The first train excursion across Canada occurred in 1886, just months before Charles Card’s first exploration through British Columbia. Growing rail lines attracted contractors and provided jobs for people, including the Mormons, who were hired from both sides of the border to build spur lines. These narrow gauge lines created a web of transportation routes throughout the western regions of both nations. Branch lines from Calgary and Lethbridge would connect the transcontinental United States and Canadian lines. They connected communities throughout southern Alberta and down to Shelby and Great Falls, Montana. By the standards of the 1880s and 1890s, this little corner of the West was changing. It was not a stop on the transcontinental routes but neither was it totally isolated.[11]

Settling Southern Alberta

Charles Ora Card moved quickly to mix with the already established influential classes of southern Alberta. It was a small group of ideological leaders whose thoughts and ideas Charles sought out as his colonies evolved. This group included the Chief Red Crow, Frederick Haultain, William Pearce, Elliot T. Galt, and Charles A. Magrath.

Chief Red Crow was the leader of the Blood Indian Tribe. He was the political statesman for his people when in 1877, under Treaty Number 7, the tribe took possession of the large Blood Reserve in southern Alberta.[12] In 1883, the land area was expanded to today’s borders, which include 352,000 acres between the Belly and St. Mary Rivers.[13] Red Crow was the leader who took them from being a nomadic tribe of hunters into an agricultural tribe. He was a warrior who had survived the tribal wars and led his people through conflict and plague. He had survived the effects of small pox and measles that had ravaged his and other tribes.[14] He had traveled across Canada at the invitation of the Canadian government to observe Mohawk progress in education and industry.[15] Before Red Crow met Charles in 1886–87, he had a dream of his people meeting those encroaching from the civilization with dignity and equality through their own industry, education, and strict preservation of reserve lands.[16] While this vision is most likely associated with the overall wave of western migration, it could also apply more specifically to the coming of the Mormons. Charles Card saw the native people and saw a great missionary opportunity, since he felt he had a common biblical heritage. Furthermore, they had been denigrated by the unscrupulous white traders from the US, and in his mind, Charles believed that he and Red Crow would become friends, working for the common good of their people.[17]

Frederick Haultain was a Fort Macleod lawyer from whom Charles and the Mormons would seek advice and counsel. He was a member of the Canadian Territorial Assembly in 1886 when Charles first met him and in 1897 became Alberta’s Premier.[18] Haultain’s view of liquor laws, politics, and new settlements complemented Card’s ideology.[19]

William Pearce was the Northwest Territories superintendent of mines and chief federal officer in the region. He was a strong advocate of irrigation. Even before the Mormon immigrants entered southern Alberta, Pearce had already conducted a field study of irrigation practices, including those in Utah, and he was convinced that the Alberta mountain rivers could be used to water the semi-arid land of the plains. With the expected new immigrants, Card and Pearce drafted the Northwest Irrigation Act of 1894, thus giving Pearce the title “The father of irrigation in Alberta.” However, it would take both the Mormons and the Galts in Lethbridge to actually introduce the first fully operational system into the region.[20]

Elliot T. Galt was the son of Sir Alexander T. Galt, one of the fathers of the Canadian Confederation, and the founder of the city of Lethbridge, Alberta. This father-and-son team developed the coal industry of Lethbridge and the two men were major landowners. The younger Galt reflected his father’s vision of western prosperity in terms of his organizational ability and economics.[21]

Charles A. Magrath was a land surveyor who worked for the Galts. In 1885, he was the land officer for their Northwest Coal and Navigation Company. He managed company affairs and was active in social and political circles. He and the Galts understood the need for employment to attract new settlers. The southern Alberta irrigation project succeeded in providing water and crops and generating jobs under the combined leadership of Magrath, Galt, and Card.[22]

Charles Card led the workforce of Mormons into Canada in 1887. It was not by choice that the Mormons were moving from their Utah homes—it was by design to avoid the US government’s Edmunds-Tucker Act of 1887, which defined marriage as being between one man and one woman. Plural marriage had started among the Mormon leadership almost forty-five years earlier in the early 1840s. It was ceased by a Manifesto issued by Wilford Woodruff, the President of the Church, on 6 October 1890.[23] During the time of the most severe persecution, the US government sought to confiscate LDS Church property and strip community leaders of their elected offices. Individuals practicing polygamy were tracked down, taken to court, fined, and served jail time. Plural marriage became a rallying point for anti-Mormons, and the resulting persecution scattered the Mormons throughout the West.[24] They fled as far west as Hawaii, as far south as Mexico, and as far north as Canada to escape persecution.[25] Although the official practice of polygamy ended, the movement of people fleeing Utah had established migrations from which opportunities and settlements grew. It is from this hostile environment that opportunities arose in which new Mormon colonies could be created and the Mormons could live in peace.

Exiting a Hostile Environment

By summer 1886, Charles’s work in Cache Valley, Utah, was considerably inhibited. If caught and prosecuted, his fine would have been $300, or what today would be worth about $7,549 today. In addition to this, he could face six months in jail for each charge. Charles had three wives, meaning there would be a minimum of three charges that could be filed against him. Considering these personal costs became unimaginable. In Logan, the new temple and Church-owned properties were deeded to an independent association in order to legally sidestep federal government takeover of LDS properties.[26] The local and national Church leaders were in hiding to protect themselves, their families, and the Church. Governance, as the Mormon majority had known it, was now almost untenable. Their meetings were in secret, taking place behind locked doors in ever-changing hiding places, which made communication difficult. Charles often used aliases to prevent intercepted mail from giving away his location or plans. Correspondence signed as Cy Williams, Jessie Tuttle, and Zimri Jorgenson were all fictitious names he used during his time in the underground and while traveling to and from Canada. Ever the optimist, Charles continued his community, family, business, and Church responsibilities, even under these persecutions. It was barely workable, and it had to change.

Logan Temple, with shed in the foreground, 1884. Courtesy of Merrill-Cazier Library, Special Collections and Archives, Utah State University.

Logan Temple, with shed in the foreground, 1884. Courtesy of Merrill-Cazier Library, Special Collections and Archives, Utah State University.

In mid-July 1886, Charles had been captured, but he then escaped from the marshals (see chapter 4). He wrote to John Taylor, President of the LDS Church, asking about relocating to Mexico to avoid being captured again and being imprisoned. In northeastern Mexico and in the far corner of southeastern Arizona, polygamous families already found a temporary, somewhat safer haven.[27] Charles reasoned that he might be released from his calling as Cache Valley Stake president and that he could purchase a tract of land in Chihuahua, Mexico, or Thatcher, Arizona.[28] In fact, he was already planning on taking Lavinia (one of his wives) and his children, and he was literally preparing his wagon for the trek. Responding to Charles’s request, President Taylor joked about his escape, which appeared in the Logan newspaper: “We heard the horse ran away with you, but this is better than to have your enemies run away with you.” Taylor’s directives to Charles were shared in underground meetings and reported in a few surviving letters. Taylor surprised Charles, asking him to explore the land above the Washington Territory.[29] Charles summarized the directives much later, noting that President Taylor asked him “to go into the Dominion of Canada and British Columbia and explore the British Domains to find a place of refuge for the much persecuted Latter-day Saint.”[30] Sterling Williams, Charles’s stepson with Zina, reported that Charles was directed “to go north and seek a place of refuge for the Saints upon British Soil.” Bates records Taylor saying, “I am impressed to tell you to go to the British North West, for I have always found justice under the British Flag.”[31] Taylor’s own Canadian heritage gave him hope for opportunities in his old homeland as an alternative to those who were hesitant to go to Mexico.[32] They charted a new direction, and the history of the Mormons in Canada, along with the families of Card and Godfrey, would take root and new communities would grow.

A British Canadian Land

As Mormon exploration of the British Territory began, the British Hudson’s Bay Company had just transferred the land to the Dominion of Canada. British Columbia, not wanting to be annexed by the United States, linked itself to the Dominion with the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway. The Canadian federal government’s willingness to assume the provincial colonial period debts cemented the decision. Mining, forestry, and agriculture encouraged pioneers to find a home in the western provinces, particularly the coast and central Okanagan Valley where the temperatures were mild. Similarly, the resources in southern Alberta were based in agriculture and coal mining.

This was the landscape into which Charles would lead the colonists. Mountain peaks reached the sky and deep canyons directed swift waters to the Pacific or the Hudson Bay, depending upon where the travelers were located in regard to the Continental and Hudson Bay Divides. The prairies were wide open, rolling hills of grass, free of any fences. There were no roads, though perhaps there were a few trails followed by animals and the native people. The Canadian Blood Indian Reserve had just been established. Since there were no roads, there were also no bridges to cross the large Columbia river in Washington or the small Lee’s Creek in Alberta. Years later, pioneers that moved to the area would call it the best land on the continent.

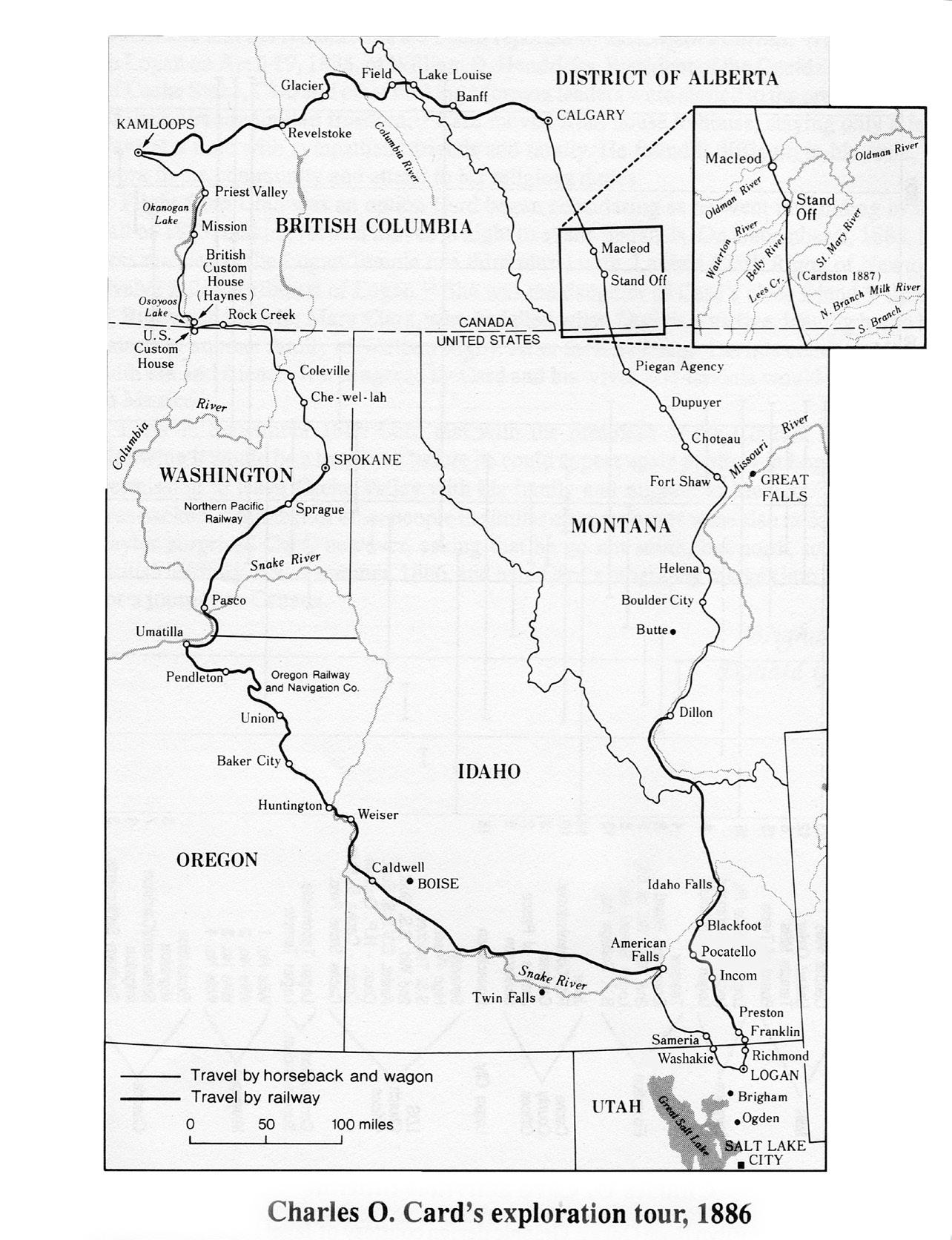

The first exploration was launched from the home of James Z. Stewart in Logan, Utah, on 10 September 1886. Charles and John W. Hendricks were called and set apart for their callings with a blessing by Apostle Francis M. Lyman. Their mission was to explore the British Northwest Territories above the Washington State line, the 49th parallel, for a place of refuge. This was the official start and the charge for their mission: explore and find a land for settlement.[33]

Four days later, on Tuesday, 14 September 1886, Charles Ora Card spent the evening visiting his wives and his oldest children, giving them each a father’s blessing and saying goodbye to his parents. His son George, who would later join him in Alberta, was six years old. Charles left his family and friends that evening under the cover of midnight darkness. He reported having $750 ($18,873) in his pocket, two horses, and a wagon. The following people helped raise expenses for the exploration: John Taylor, as Trustee in Trust, raised $300 ($7,549); C. O. Card raised $100 ($2,516); M. W. Merrill raised $100; William D. Hendricks raised $50 ($1,258); P. G. Taylor raised $20 ($503); Henry Hughes raised $20; Ralph Smith raised $2; and the Cache Stake Defense Fund raised $178 ($4,479). This brought the total to $770, or what would today be worth around $19,376.[34]

The objective of the first leg of travel was to make it to the British Territories unscathed and without arrest. Card was to be accompanied by Hendricks and David E. Zundell. Hendricks was an experienced pioneer who lived in Richmond, Utah, near Logan. Zundell was a missionary to the First Nations people, Shoshone, and Bannock Tribes in northern Utah and southern Idaho. He spoke the native languages and served as the first bishop over a Native American ward in Washakie, Utah.[35]

Card and Hendricks were leaving Logan together and planned to pick Zundell up along the way. They were accompanied by Charles’s brother-in-law William F. Hyde as they left Logan that night. Hyde was to take them as far as American Falls, Idaho, in his democrat wagon, where they would connect with the Oregon Short Line train, upon which he would return to Logan. This first wagon ride was nothing like the sturdy covered variety commonly associated with western migrations. A democrat wagon was a simple, framed, flatbed wagon fitted with temporary seats for the passengers. It was inexpensive, lightweight, and only sometimes had cover. This was basic, even rough transportation. The group drove through the night arriving at Washakie, named in honor of a Shoshone chief, located just south of Portage and the Idaho border.[36]

Zundell was not at the rendezvous spot to meet them, but a native, James Brown, agreed to help them search. He took the two across the Idaho state line to Samaria, where they spent two days searching for him. They finally found Zundell just north of the Snake River, and with him joining the group, the exploration party was now fully assembled. They gave Brown two blankets for his scouting services and thanked the Lord in prayer for locating Zundell.[37] “The Lord is always on our side,” Card wrote, “when we trust in Him, for surely we did, for not a person in Washakie knew of B. Zs [Bishop Zundell] whereabouts.” The confusion they experienced here may have sprung from the reality that Zundell likely knew little or nothing about the call he was about to receive.[38] As the three prepared to depart, they exchanged food with the locals, giving them apples for hay. The locals accepted the exchange in kind and let them off without a cash payment, “because we were his Mormon brethren all of which we appreciated.”[39] The trio drove their wagon to the Oregon Short Line train depot in American Falls and caught the train to Spokane, Washington. “We were watched closely by the conductors and others as much so as if we were desperados,” but no one said a word.[40]

Card, Henderson, and Zundell rode the train northwest from American Falls, Idaho, through Huntington, Oregon, where they switched to the Oregon Navigation Company Railroad and continued on to Pendleton, Oregon. They crossed over the Columbia River to Pasco, Washington, finally arriving at Spokane, early in the morning of 20 September, six days after they had left their homes. They had come almost 880 miles by wagon, horseback, and train. They needed rest but felt uneasy about stopping. Instead, the day was spent readying for more travel, and they purchased three saddles and seven horses, two of which were used as pack horses.

Early that afternoon they retired to the Spokane Keystone Hotel and rented an upstairs room in the southeast corner of the building, just above the saloon.[41] For protection and to save money, all three stayed in a single room. Card and Hendricks were soon asleep from exhaustion and jangled nerves. Zundell took the first watch, staying alert to any potential dangers. At one o’clock in the morning, Zundell heard a threatening conversation growing in intensity among the men from the bar below, “these Mormons are here and I am after them.”[42] The would-be captors crept quietly upstairs, and within moments they were only a few feet from the door. Zundell woke his companions, and after listening to the men outside their door and discussing their options briefly, Card and Hendricks went back to sleep, leaving Zundell wide awake. He heard the intruders again shouting at the hotel keeper about the “renegade Mormons and demanded admittance into our room,” but the keeper refused.[43] Zundell again woke his companions, they listened to the threats outside their door but now could hear only whispers. Contemplating the possibilities of a second arrest, this time so far away from home, Card “asked the Lord to cause the [threatening] party . . . to sleep long enough for us to pack up and get out of the way. We all exercised our faith in this direction . . . [then] got up one at a time, went downstairs, passing their snoozing opposition. They met on the banks of the Spokane River, packed their horses and by 9:20 A.M. rode out of harms way.”[44] They did not get much rest, but they were safe.

The tension of constant danger was unsettling, but at the same time, it motivated them to move forward. They put the danger aside and focused on their mission. As they traveled, they visited the locals, who did not know them. They asked directions and marked their travels. North of Spokane, they happened upon more Native Americans, Chinese, and Caucasians, all of whom were mining. They were often unintentionally misdirected and took several wrong turns. But even these exchanges were seen positively as giving them the opportunity to learn more of the countryside, trails and wagon roads. In this rugged mountain terrain, they met generous people who assisted them with food, information, and feed for their horses.

The explorers stopped at one mine when Zundell was sick, and the miners offered him medicine, suggesting that he had been “with too many women the night before,” prostitution being common in these parts.[45] Not wanting to give away his identity, Zundell played along with the group and avoided their medicine. The next day, as he was recovering, the miners gave them directions which once again proved incorrect. By 26 September, they had reached the banks of the northern Columbia River and were in search of a ferry to get them across. It took two days to find a ferry, but once they did, they paid $7 ($176) to cross.

On the north side of the Columbia, they met a party of Native Americans from Colville who were headed to a powwow at the Okanagan Lake, where they “were going to dance, run horses and have a good time.”[46] They were cheerful and friendly, so Card and his party rode along with them.

“In Collumbia We Are Free”

Wednesday, 29 September 1886 was a historic day in the history of Canadian Mormonism. Card, Hendricks, and Zundell broke camp south of the Canadian border, headed north, and at 9:35 a.m., they crossed the 49th parallel onto British soil. There was a unanimous sigh of relief. They felt they were out of danger and had reached the land they were sent to explore. Charles took off his hat, swung it into the air round his head and shouted, “in Collumbia We are free.”[47] At this point, the serious search for settlement land began.

Charles met with John C. Haynes, who was a collector of customs, a justice of the peace, and an owner of a small ranch in the Okanagan Valley.[48] Charles took time with him to learn of the regulations relative to immigration. He got the impression that the British and American customs officers were “not on the most friendly terms,” likely lessening his own anxiety and making the group feel safe.[49] Their intention then was finding a location within British Columbia and returning to Utah via the same route that brought them this far. They registered their horses to avoid paying import duty when they returned to the United States. They also paid an incoming duty of $28 ($705) for their belongings, and then they rode up the Osoyoos Lake a few miles away, camping with the First Nations people.

The first LDS sacrament meeting conducted on western Canadian soil under the authority of the Melchizedek Priesthood occurred on Sunday, 3 October 1886. Only the three men attended, and they met at 1 p.m. They rested and prayed, and Card preached, blessed the land, and asked the Lord to direct them in their explorations to find the right place. They blessed and passed the sacrament, and then each declared their testimonies of the gospel, declaring that they had “never felt better in their lives.” The meeting ended, and they went down to Osoyoos Lake, bathed, and retired for the evening early. Truly, this was “a day long to be remembered by our little party.”[50]

Exploration of Alberta

The Okanagan Valley was a beautiful region of southern British Columbia, right on the border between British Columbia and Washington state. It was defined by the Okanagan Lake and its tributaries, and it was a land with a moderate climate, rich in water, minerals, and timber. Card’s exploration party zigzagged along the terrain as they worked their way northward.[51] They stopped at the home of Michael Keogan, who was among the first settlers in the valley. He gave them information and a parting gift of fresh fruit.[52] As the three men continued traveling, they were keenly alert to the natural resources of the land and the people. The Natives were the farmers and whites the ranchers, the opposite of Charles’s experience in Cache Valley. Stock cattle cost between $28 and $30 and milk cows $45 ($705–755 and $1,132).[53] Though the land was rich for farming, the best land was already occupied. They traveled up the Okanagan River to Penticton, which Charles described as a “small Indian Village.”[54] They explored Mission Valley, west of Kelowna. Mission Creek was the main source of water running into the Okanagan Lake and of special interest to Card, but despite all this, the most farmable land was already taken.

Traveling was uncomfortable. In some areas, there were no roads or even trails. Instead, the three men were high on rocky ridges, low in deep ravines, and surrounded by dense forests, all of which they crossed on horseback. However rough the trip, they were treated warmly by those whom they met. For example, people gave them fruit all along their journey. Card watched the natives fish for salmon in the river. Zundell shot a deer and they ate well, but because Card did not eat a lot of meat, they gave it to the natives.[55]

It was at the northern end of the Okanagan Valley near Mission Valley where the explorers met an old mountaineer, Duncan McDonald. Duncan was a British trader, who in 1871 worked the Hudson’s Bay Company Flathead Post at Fort Connah.[56] McDonald was the son of the Canadian Hudson Bay Company trader Angus McDonald. As a young man, Duncan hauled freight—likely beaver and trapped fur—for the Hudson Bay Company from the Flathead Lake Reservation in Montana into Alberta. On these trips, he had passed through the mountains of what today is the Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park in northern Montana and southern Alberta. Lake McDonald bears his name.[57] He knew the area well, so when McDonald gave Card information, it changed their direction and ultimately led to a settlement in southern Alberta. He told them about a sparsely settled land on the eastern side of the Rockies. Charles felt this information came “as we needed and we all feel to acknowledge the hand of the Lord in it.”[58]

They then were heading as quickly as they could to Kamloops, where they would catch a Canadian Pacific Railway east to Calgary, Alberta. They were approaching Priest’s Valley at the head of Okanagan Lake when they were forced to seek shelter from an autumn deluge. They stayed with a rancher just in time to save his life. The man’s wife had deserted him and when Card’s party arrived, he was in the middle of a “drunken spree and sought to nearly” commit suicide. The group counseled the distraught rancher, “talked with him, quieted him, [and] gave him good moral advice.”[59] They had saved his life, at least for a time. They stayed the night and left in the morning.

Three days after receiving McDonald’s directions into southern Alberta, they crossed the Salmon River, and then reached the Thompson River. All through British Columbia they consistently noted the best land was still inhabited by the monopoly of the larger ranchers who had arrived earlier and already homesteaded. Eighteen miles east of Kamloops, they came across a stagecoach station. Charles boarded the coach arriving ahead of Hendricks and Zundell so that he could make arrangements for train tickets as well as report to Church headquarters. He reported to President Taylor that they were unsuccessful in British Columbia because “the laws of this land are so liberal that a few cattle kings hold all the country, especially the desirable portions. . . . We have learned of a fine and extensive tract of prairie land situated on the east side of the Rocky Mountains . . . . [with] much easier access to our people through Montana.”[60]

Kamloops was a bustling railroad town and had just celebrated the first train excursion across Canada, which had passed through only four months earlier, in June 1886.[61] Hendricks and Zundell followed along the Thompson River and arrived shortly after Charles. It took a few days to sell their horses, and they kept their saddles, satchels, bedding, and purchased train tickets for Calgary. The fares were $26.10 each ($657), plus freight costs for their saddles and belongings. Total costs were $87.50 ($2,204). They boarded the train at 2:00 a.m. and rode through the Canadian Rockies. “We rode all day through mountains, gorges, and around sharp curves and over high trestle bridges across . . . dry ravines all wending our way to the Territories of the North West.” They arrived in Calgary at 3:00 a.m. on 15 October.[62] Away from home for more than a month, they traveled by every conceivable means of the time.

The explorers found Calgary different from the warmer valleys of the Okanagan Valley. It was a rapidly growing rail and cattle town on the Bow River with some 1,300 inhabitants.[63] Originally, the Bow River land was occupied by the Blackfoot, Blood, and Psuu Tina tribes. The Hudson’s Bay Company traders had begun camping along the Bow, and by the mid-1880s, farmers were moving onto the plains. By 1883, the Canadian Pacific Railway had reached Calgary, Alberta.

Charles and his companions were hesitant, because when they exited the train in Calgary, they had arrived in the middle of a blizzard. It lasted all day, so they were not too impressed with the frigid weather. However, their spirits remained buoyed by the descriptions McDonald had shared and they decided against their urge to “take the next train for a warmer clime.”[64] They needed horses again, but their funds were low and prices were much higher in Calgary. They visited the stables, looking for the best deal, and with their budget of $180 ($4,529), they purchased two horses and a wagon. They settled on a rather wild team of broncos they dubbed “Brit” and “Bert” in honor of British Columbia and Alberta. The horses were nearly uncontrollable, jumping, jostling around, and charging in every direction. Zundell got kicked in the leg, which left him limping for a few days. One horse, while the men tried to harness the team, “threw himself under the tongue of the wagon.” Unfortunately, this was the best team available, despite considerable shopping.[65] They stayed a second night at the Calgary Royal Hotel. The next morning, they paid their bill and hitched their team to their wagon.

On the first travel day south, they covered just eight miles. They crossed the beautiful well-watered prairie with its rich black loam soil, and they noted unlimited timber resources in the mountains just to the west. Fort Macleod was a “little warmer” and not so frostbitten as Calgary. Established in 1874, Macleod was a Northwest Mounted Police Post, and by 1886, it had become a trading and administrative center of several hundred people.[66]

They stayed a night in Fort Macleod, camping along the Old Man River and learning what they could from the Mounties. The next day, they traveled to the junction of the Kootenay and Belly Rivers. Today, the Kootenay River and the Kootenay Lakes are the Waterton River and the Waterton Lakes. Here they observed the least signs of frost and that “good land and water, the two essentials for farmers and husbandman” were abundant. They further noted that there were coal miners east in Lethbridge. Settlers reported that the “winters [were] very light here.”[67]

Locating the Settlement Site

Card and his companions were in the heart of the Blackfoot Confederacy with the Blood and Piegan First Nations people. Card thought that “this would be a good place to establish a mission . . . [the people] are intelligent . . . although degraded by the many low lived white men that allure them to whoring” and alcohol.[68] They stayed a few days at Standoff, Alberta, a name given the area by the Natives who had stood off US whiskey traders attempting to sell alcohol. Card was resting the horses over the weekend, one of which had gone lame. They searched for another horse but without success. On Sunday, he and Zundell hiked west along the Waterton River, two miles from Standoff, where they knelt down and “dedicated the land to the Lord for the benefit of Israel both red and white.”[69]

After this, they set out to locate the settlement site. There are three stories as to how the Cardston town site was selected. The first has roots from the meeting with Duncan McDonald in British Columbia. Some suggest that McDonald gave them more than a description. He related “a grass-covered buffalo plains where the country could be plowed for miles,” and which Charles later declared, “where the buffalo can live, the Mormon can live.”[70] Charles’s wife Zina records, “Card gathered them [Zundell and Hendricks] close and with their arms around each other’s shoulders said, Brethren, I have an inspiration that Buffalo Plains is where we want to go.”[71]

The second is an apocryphal story of one night in 1886 when they were camping at the junction of Lee’s Creek and the St. Mary’s River. The trio had pitched their tent and had retired for the night. The wind was blowing and snow covered the ground. Charles was pondering the location for settlement, his mission, and what would come of it. As he lay in thought, he sensed “someone in the tent with him.” He looked up and an angel appeared. He was dressed in the tradition of the First Nations people, “immaculately clean.” The angel introduced himself as Rega, an ancient Native who had once lived on the land. The two talked through much of the night about what was ahead for the country and the new colony Charles was sent to establish. He supposedly told Charles that the place for the Mormon settlement was there along Lee’s Creek, and then the angel disappeared as suddenly as he had appeared. Charles got up, questioning what had just happened, went to the door of his tent, and looked out over the land. There were no tracks in the recent light snow, which someone one would have made had they walked into and out of Charles’s tent. He was certain he had seen the vision and was equally bewildered.[72]

The third version of the location decision is most likely accurate. On the first 1886 exploration trip, there was no specific settlement site selected. However, the explorers camped in the vicinity of the St. Mary’s River and Lee’s Creek and explored the area thoroughly. They rode along Lee’s Creek to the Mounted Police Outpost, toward today’s Beazer town site, where the officers gave them hay for their team and possibly more directions. They camped the night and headed southeast toward the North Milk River. They were within a few miles of the US border, traveling east along Boundary Creek toward today’s Del Bonita and Whiskey Gap areas. Finding no wood for their own fire, they cooked their supper over a fire of dry buffalo chips, “a rather smokey uphill business.”[73]

The exploration was complete. They were on their way back to Utah. They had a regional destination and a recommendation for President Taylor, but the exact location was undetermined until spring 1887.

Explorers Part Ways

Card, Hendricks, and Zundell had completed their exploratory mission, and they were in a hurry to return home. Yet even in these homeward travels, Charles remained focused. Now he was creating a route for future settlers who would migrate to Canada.

On 1 November 1886, they camped in Prickly Pear Canyon south of Great Falls, near Wolf Creek, Montana. Here, they unintentionally met some Cache Valley friends who had been working on the Canadian Pacific Railway near Medicine Hat, one of whom was Charles’s counselor in the Cache Stake presidency, Orson Smith. It was a joyous occasion. Simeon Allen collected $75 ($1,887) to help Hendricks and Zundell complete their return home, no doubt understanding the financial needs of the exploration team.[74] The team drafted a report to President Taylor in final preparations for leaving.

The report was written by Card and signed by all three: Card, Zundell, and Hendricks. They described what they had learned from the old settlers, mountaineers, the Natives, and their own experiences. They liked the Kootenay and Belly River area of southwestern Alberta because they were less frostbitten than the other locations they scouted and the grass was plentiful. The land between Red Deer and Calgary, Alberta, was better for farmland. Good coal was abundant and the industry was growing, as were the spur rail lines that served southern Alberta and northern Montana. As proof of successful farming, Card carried home samples of oat, barley, potato, and wheat crops raised by the Blood Tribe. He noted both ranching and farming success without irrigation, but suggested irrigation would be needed south of Macleod. He wrote appreciatively of the information he received from the people of the Blood Tribe. He noted their location near Standoff, and he again commented disgustedly on the “degrading influence of the unprincipled white man.” He closed his report with a note comparing the southern Alberta climate with that of Bear Lake Valley, in northeast Utah. “The snows are melted earlier and oftener by the south west winds (chinook) is the only advantage I can see or learn at present [different from Bear Lake]. Southern Alberta had been a grazing ground of the buffalo, but now only their bleaching bones mark their last resting place.”[75] After signing the report, “I bade Bros. Zundell and Hendricks goodbye and had become so much attached to them I could not refrain from tears.” The original Canadian Mormon explorers’ work was complete and they parted company, acknowledging “the Hand of the Lord” in all things.[76] Charles was alone, and he filled the day writing to his family, doing laundry, and resting. He celebrated his forty-seventh birthday writing in his journal and expressing love for his mother.

Charles was anxious to hear about his next assignment and whether he would be sent to the north or to the south. “I am setting alone . . . my thoughts turn homeward to my wives, children, parents and many friends . . . who risk their own liberty for the servants of God. . . . I would enjoy the caresses of my wives and children, could we be free from the hand of tyrants that lust after our homes and property. Free from those that demoralized our community. Free from those that would debauch our son and daughters . . . of their virtue. Sometimes we feel to say, ‘Oh Lord how long . . .’”[77] On 12 November, a letter arrived from President Taylor thanking Charles for his service and directing him to return to Cache Valley.

Homeward in Disguise

Charles was anxious to return to his family and at the same time was nervous about returning to the United States, but he prepared his wagon and left immediately. Heading for Dillon, Montana, he passed through Helena and Boulder City. He slept under his wagon as the snows increased, alert to the fact that he was an outlaw. As he approached Dillon, where he could catch the train, he donned a disguise. As part of this disguise, he shaved his beard. It was the first time in fifteen years he had shaved it off. He then dressed in a “greasy canvas coat and blue jeans.” He boarded the train, saw both people he knew and people who opposed him, but he went about undetected by both. “One young man was so taken up with his sweetheart so much that he did not recognize me with my beard off.”[78] Those who knew Charles and recognized him said nothing.[79] Those who could have arrested him must have regarded him as a mountain man working for the railroads. He passed safely, getting off at Preston, Idaho, just north of the Utah border. He stayed with friends and met with William C. Parkinson, bishop of the Preston Ward. Parkinson took him into his own home where Charles caught up on some sleep and ate before the last few miles of his journey. Parkinson had already organized confidential communications for getting Charles back to Logan. In an ironic twist, as Parkinson was making arrangements for Charles, he himself was preparing for his incarceration because of polygamy. That very evening, his children were gathered around him saying their good-byes. The scene drew tears from Charles.[80] The next day, Charles had arrived safely back at home.

Recruiting Settlers

Charles’s exploration travels had ended. The larger task before him was now recruiting settlers for a new colony. Working from exile while simultaneously organizing an immigration movement was a challenge. The Edmunds-Tucker Act was passed on 19 February 1887, just four months after Charles’s return. This new act increased the pace of persecution and confusion, as well as the intensity of the rhetoric on both sides. On one side, the anti-Mormons pushed to rid the nation of polygamy. On the other, the Church was in a scrambling, moving assets away from possible government takeovers. The new law put into effect greater persecuting, fining, and jailing of polygamists, and marshals had become increasingly aggressive. This was the atmosphere in which Charles was expected to recruit.

Charles again hid among family, friends, and in the wilds of Logan Canyon. He so wanted to be with his wives and family where he was freed of his loneliness, but he felt unsafe, knowing the marshals were already watching his houses. He maintained his beardless disguise and remained in hiding, even scaring a few friends who thought he had been called away on a mission to England. His anonymity allowed a little flexibility to recruit reluctant volunteers for the expedition to Alberta in the spring. People were afraid because without financial assistance, which the Church could no longer provide, and no calling to go from President Taylor, it seemed that no one could afford the move. Some just thought it wiser to take their chances, remaining hidden in Logan.[81] In short, Charles was not having a lot of success.

Card met with Apostle Franklin D. Richards on Friday, 4 March 1887, for four hours. At this time, he received directions and his calling. He was feeling “nearly alone to go to Alberta [but at the same time] . . . expected to go.” He persuaded a few recruits but not many. He poured out his lonely soul to his friend and leader, and Richards replied only encouragingly to Card, telling him, “If I went I would be the founder of a city and do a good work as a pioneer in a new country and should be known for my good works.”[82] He gave Card a blessing and sent him on his way. The meeting boosted Card’s spirit and determination. Soon after, he was preparing for his second trip to Alberta. He counseled with his wives, particularly Lavinia, who originally was to accompany him to Mexico, and Zina, who would now accompany him to his “northern mission.” He received Lavinia’s blessing, which she freely gave and wished him a safe journey free from the “vengeance of [his] enemies.” Card was touched. “When a man has a quorum of wives that pray as faithful for my safety, he is much inspired . . . God Bless the faithful wives of all the undergrounds. Also, those of the Imprisoned and exiled.”[83]

Canadian Mission

Card visited family and friends over the several days before again departing for Alberta. He stayed with Lavinia, and her youthful spirit buoyed his own. He would have preferred staying home with his wives if he could just be left alone to care for them—but it was not to be. At 8:00 p.m. on Wednesday, 23 March 1887, he started north again. This time his disguise had a few refinements. Besides being clean shaven, he sported a new mustache, a heavy cane, and a pipe, even though he had “not learned that filthy habit.” William Rigby again provided transportation to the train depot in Idaho. However, before they barely made it out of Logan, he accidentally drove the wagon over an embankment and into a river. Charles and William were soaked in the cold mountain runoff and their possessions were swept downstream. In all the commotion, a group of marshals who were camping across the stream hurried to investigate. Charles spoke to them in a heavy “Irish Brogue” explaining the situation. They did not recognize him, and they headed back to their camp.[84] Charles and William changed their clothes, did a little repair on the buggy, and were quickly off again. Charles felt the accident was the hand of Providence, for had they not fallen into the creek, they would have driven directly into the camp and the hands of the law.

First immigration route, 1887. Courtesy of Michael Fisher, cartographer, University of Alberta.

First immigration route, 1887. Courtesy of Michael Fisher, cartographer, University of Alberta.

The remainder of the trip was solemn and uneventful. Charles caught the train at Marsh Center, south of Pocatello, and two days later arrived in Helena where he met his friends Simeon F. Allen, Joseph Ricks, Michael Johnson, and Niels Monson, who were working on the railroads.[85] He waited with them for the arrival of Thomas E. Ricks, who he expected would join him.[86] Card did not like waiting, but he passed the time writing, reading, attending Catholic services, and shopping for farm tools. He also attended a dramatic production of “Over the Wall,” performed by the George S. Knight Comedy Company, which displeased him.[87] He lamented missing the birthday of his oldest daughter, Sarah, with the feelings of a helpless father. He had given her a blessing a few days earlier, but he was anxious about the reappearance of her mother, Sallie, who had divorced him, and he was afraid that her anti-Mormon beliefs would influence their daughter, who he sensed was vulnerable without a father’s influence.[88]

By 2 April, Card could wait no longer. He said his goodbyes and left with Thomas X. Smith and Henry Morrison, who was driving the wagon.[89] Thomas Ricks finally caught up with the group west of Great Falls, near Flat Creek in Choteau country.[90] Charles knew these men from Church and community endeavors. They were trusted friends, and several were in the same predicament, running from the marshals. He called his friends the “exiled band.”[91]

Attempting to recruit immigrants, Card called on people even while he traveled. He must have been somewhat nervous when the sheriff of Choteau warned him about a group of threatening Natives roaming the area. However, his small band of brethren “rode the ranges [and] were heavily armed as a rule.”[92] They always took precautions, tethering their horses at night to prevent theft. The group was always friendly with the local natives while on this trip and purchased their hay for their horses.

Once Card arrived in southwestern Alberta, he and his companions immediately began scouting for a specific settlement site. They met with Canadian senator Matthew H. Cochrane.[93] Taking advantage of settlement laws, Senator Cochrane owned a one-hundred-thousand-acre lease on the property along the Waterton River in southwest Alberta. This interested Card, but Cochrane told them he had no authority to lease the land to them.[94] Ironically, this very Cochrane Ranch operation went out of business in 1903 and was sold to the LDS Church for $3,128,000 ($78,705,000).[95] The locals would later call it “the Church Ranch” until 1968 when it was sold.[96]

Charles was unsuccessful in purchasing the land from Cochrane, so he headed to the Belly River. As he traveled, he communicated with Thomas White, the Canadian secretary of the interior, as well as Elliot Galt, asking for information on leasing land for a settlement. He checked in with the Fort Macleod Customs at this same time.[97] Then, finally, he wrote President Taylor and suggested the lands be purchased south of the Blood Reserve. On Monday, 25 April 1887 at 8:00 a.m., he and his companions traveled up Lee’s Creek, passing a coal prospect, finding plentiful grasslands and several unoccupied flats of land. They returned at 7:00 p.m., hunted and ate prairie chicken for supper, and then retired for the night.[98]

The next day, they headed back to the St. Mary’s River and Lee’s Creek junction. They traveled upstream to the Mounted Police post for dinner, after which Charles and Smith again went up the river another five miles exploring. “River bottoms were gravelly, good [farm] land being vastly in the minority, however it will all afford good pasture, but the best soil is not so good as on the bench of the plateau on the south side of Lee’s Creek.” That night they fished and had three rainbow trout for supper, “their first from Canadian waters.” It was a windy but pleasant evening. “This evening we voted unanimously that Lee’s Creek was the best location at present and decided to plant our colony thereon.”[99] Card felt this was a place from which they could grow, and the North West Coal and Navigation Company, owned by the Galts, purchased the land.[100]

On Sunday, 1 May 1887, the first settlers arrived: Andrew L. Allen and Warner H. Allen, from Logan. They cheered Card’s heart.[101] Within days they had begun plowing and planting. Shortly after, twelve families would arrive, including Card’s third wife, Zina, whom he met on route near Helena. It was a small beginning, but the settlement would grow. Charles’s labors in Canada extended over sixteen years, starting with the exploration in 1886 and ending with his release as the Alberta Stake president in 1902.

Legacies of the Man

It would be easy to write about the towns and pioneering legacies that Charles left behind. He and his father owned the Cache Valley Lumber Mills of the Card and Son Company, and they worked together for the Central Mills under the United Order. He was on the Board of Trade in the Order and was the superintendent of the construction of both the Tabernacle and the Logan Temple. He was experienced in construction, which included building his own homes. In irrigation development, he was instrumental in three Logan systems: Logan and Hyde Park, Logan and Richmond, and the Logan and Smithfield. He brought this experience into Alberta. Irrigation fostered farming throughout southern Alberta, and it invited Mormon settlers to the area, who could be paid in land and dollars for their labors. In Cache Valley, he was a teacher and was on the Logan School Board and the Brigham College Board. In civic activities he was a Logan city councilman, a road commissioner, a justice of the peace, and a selectman and coroner. His Church callings in Cache Valley included being a Sunday School teacher, Sunday School superintendent, counselor in his high priests group, counselor in the Cache Valley Stake presidency, and finally stake president. His stake at one time included Rexburg, Idaho, and stretched all the way into Canada.

Apostle Franklin D. Richards told Charles that if he went to Canada he would be the “founder of a city, . . . a pioneer in a new country and known for his good works.” That blessing clearly came to pass. He conducted the first Latter-day Saint exploration of western Canada, scouting south-central British Columbia and southern Alberta for settlement land. He led the first Mormon immigrants into Alberta and established the settlement. He networked with the influential people of Canada, and with them, he developed irrigation through the area. Many of the southern Alberta towns and irrigations systems had their foundations in his leadership. These accomplishments reflect his success, but they also reveal something about the spirit and the heart of the inner man.

Charles was in Logan for only a few months recruiting settlers and then was on the road again. Lavinia and Sarah were the wives he sorrowfully left behind. Zina would meet Charles in Canada.

A Tender Heart

There is ample evidence to trust that Charles had a tender heart. His diaries and letters exhibit several undeniable examples that reflect the love of a husband and father. His work ethic and commitment to church assignments were balanced with a tender heart, supportive wives, and an infallible faith in the gospel of Jesus Christ.

His teenage heart reflected tenderness even along the Mormon Trail as he crossed the plains with the first handcart company. He was sixteen and assisted his father and uncle as they buried his little sister Polly. Charles felt sorry for the European immigrants who were treated unkindly by the trek leaders because they were unfamiliar with cattle, horses, and the oxen, thus causing too many delays. They were forced to walk more than others. Charles quietly snuck them into his wagons as the company progressed and he let them ride and rest.

He loved his parents and conveyed a deep respect for them. He was a business partner with his father, and his mother was the first president of the Logan Second Ward Relief Society. Charles lived with them until he was twenty-eight, when he was first married. On his forty-seventh birthday he paid tribute to his mother, saying, “The lucky boy [I was] to be given a mother . . . an excellent faithful one.”[102] His parents taught him honesty, hard work, faith, and constant service to the Lord. While visiting from Canada in 1889, he saw his mother, who was then seventy years old. Her body was “broken with toil,” and he did not know how much longer she was going to live. When they met, “she clasped my hands kissed me then embraced me and we wept together.”[103]

A most loving tribute to his mother came a year later when Card visited his wife Sarah. His mother brought him a piece of her pie, which caused him to write that “every time she comes she brings me some little nicknack. A kinder hearted mother never lived. She is always kind to everybody.”[104] Within five years, he would return for his mother’s funeral, where he was to have paid his last tribute “to a mother that has been very dear to me and always faithful to her trust as ever valiant in the testimony of Jesus Christ.” Sarah, Lavinia, and their children attended the funeral, but Card did not. Washed out roads and flooding delayed his arrival until after the funeral and after his mother’s burial. His heart was broken as he could only visit her grave. He was buoyed by the knowledge that he would be with her in the eternities: “She had died faithful. Now it is left with me to follow and if I am faithful it will sur[e]ly come to pass.”[105] His father died a short time later on 8 September 1900, and Charles attended the funeral in the Logan Tabernacle, “a grand edifice that I superintended . . . at a cost of about $80,000 ($1,699,724). Father and I tried to do our part in this.”[106]

A Caring Father

Charles and his second wife, Sarah Jane Painter, lost their first daughter, Matilda, to death. On Saturday, 13 December 1879, after a series of church meetings, he returned to find Matilda Francis critically ill. She was just twenty months old. Over the next eight days, as he went about his duties, his mind was filled with dread. On Sunday, 21 December, she was worse. He called Elders Charles W. Nibley and William Apperly to administer to her, after which Charles laid his hands on her head and gave her a father’s blessing. She ended up passing away. Four days later, it was Christmas. He was happy to spend time and eat dinner with his family, but he declared, “I feel more to sorrow than joy.”[107]

This experience repeated itself on 17 November 1894, when Zina’s son, Orson Rega, fell sick with life-threatening fever. Charles left his home quietly, remembering a promise made at the dedication of the Salt Lake Temple that if anybody desired a blessing, he or she should take it to the temple and ask the Lord. He went to the temple at 9:00 p.m. Secretly, while sitting alone in the sitting room of the Logan Temple, he poured his soul to his Father in Heaven. He pleaded with the Lord to “spare our son, to relieve him of the raging fever and give him rest.” He returned home and his son’s recovery was so sudden that it startled both him and Zina. Two days later their hearts were filled “with gratitude toward our God and deliverer.”[108]

One day, four-year-old George and his three-year-old sister Lavantia (son and daughter of Sarah Jane Painter) were entertaining themselves in the parlor of the home. Their mother was down the block helping a neighbor and left the children for a few minutes in the care of an elderly gentleman. Charles, their father, was in Ogden attending to Logan Temple construction business when he felt impressed to take an early train home. He arrived, visited with an aging brother, and, determining all was well, he relaxed by reading the newspaper as his children played. Suddenly, there was a “peal of laughter followed by screams.” He ran to the door and saw his daughter on the floor, looking up at the lace curtains blazing with fire almost as high as the ceiling above her head. She just sat watching the fire and smiling as though it were entertainment. He moved with the speed only a parent can muster, rushing into the room, pulling the curtains down, and smothering the flames. The older gentleman was hard of hearing and never sensed the danger. Charles, however, immediately realized why he had been prompted to take the earlier train. His children were safe and disaster was averted.[109]

By 17 April 1889, Charles had been on the road for almost three years, exploring and creating the settlement and that would continue for more than a decade. To stay away from the marshals, he could visit only briefly and write under a pen name. During this time, he visited the children at home when he could. One evening when Sarah had brought supper and their children, Charles realized that he did not recognize two of his youngest, Pearl and Abbie. They were three and one years old when he had left for Canada, and now five and three respectively. “But the trial came . . . when I drew each one to my bosom and kissed them was more than I could do without bursting into tears. Who would not weep for their own flesh and blood when forced from them by the power of an unrighteous government?” He was always delightfully pleased to know his children were well and especially enjoyed the photos, “just lovely and much appreciated by their exiled father I can assure you,” which he underlined for emphasis. “Tell Georgie [George Cyrus Card] it pleased papa much to hear he can cut wood for ma . . . I hope to hear he takes good care of the garden and is a good boy in school.”[110] As George grew into teenage responsibilities, his work was much more in the garden and on the farm.

Charles wrote and praised each child. He loved the letters he received, and although Sarah wondered if he could read the children’s writing, he responded “those loving letters of Pearl’s and Abbies, why papa can read them like a book and knows every letter and mark came just from their dear little hearts. God bless you my sweet little daughters. I love you and return you a kinder kiss each and so many for Georgie.”[111]

Family Traveling Together

Charles had a special affection for his wives, who he called his quorum of good, faithful wives.[112] He married four times, and he spent as much time as possible with his wives and families. They were all together when they could be and met individually when circumstances would otherwise allow. During the years prior to persecution, he often took them on his travels throughout the stake. He established each of them in different locations during the years of persecution, removing them from danger and incarceration. During the years in Canada, he visited them each at least once or twice a year.

On 6 February 1887, he had just returned from his first exploratory trip into Canada. Keeping out of the way back in Logan, he described as “pleasant to meet one’s family in these precarious times and when man is deprived of these things they seem nearer when they come. Thank God I have wives that love me for I know I have the ones I implored the Lord for and I pray ever they may keep the faith and rear their children of my loins in fear of God and not of man.” Just a few days later he was hiding behind a door listening in on a testimony meeting at his home. It filled his heart. Zina and Sarah both spoke expressing their spirit, “which was a great satisfaction to a husband that so much desires their children behold an example of faith.”[113]

Emotional Trials

In 1887 while in Canada, Zina would serve as the private secretary to her mother, Zina D. H. Young, who had been called as the president of the Relief Society of the Church. Charles’s response was both humorous and reflective of his person. “While it will leave me wifeless in this land, I have never refused to comply with the wishes of my [church] leaders and always desire to act in concert with the prophets of God.”[114] On 4 November, a dozen years since his first trip to Canada, Charles wrote to Zina in Salt Lake, “I have no greater interest in heaven than my wives and children and some of them have been a sore trial to me, . . . yet I have done my duty by them.”[115]

There were several emotional trials in Charles’s life that spanned the spectrum of life’s challenges: illness and death, capture and escape from the US marshals, leadership in exile, exile from home because of vigilant marshals, children without a father, wives without a husband, and, unfortunately, unwanted divorce.

One of his wives, Sallie, had what Charles saw as a negative influence on their children during his exile, and this influence drew them away from him. Charles had done everything within his power to avert the divorce, which dragged out over almost seven years. He had counseled Sallie. He admonished her to repent from her promiscuity but all to no avail. She would promise to be faithful and then recant. “Many is the day I [Charles] have tried to drown those affiliations with hard labor and seeking the Lord for consolation and aid, which I have received and thus far have been able to carry the burden.”[116] The burden was growing with each passing year. “How sad to contemplate such a thing as the parting of a man and wife, a circumstance, I have always abhorred from my youth, but when a wife or husband ceases to love the truth there is no knowing what length they will go.”[117] He learned, on 24 March 1889, that Sallie had enrolled their oldest son, Charles Jr., in the Episcopal School in Logan. This was painful to a father who wanted his children “to walk in the light of truth.” Despite his aching heart, his letters to his eldest daughter, Jennie, and Charles Jr. reflect only love and concern. He was never negative in his writing about their mother or the divorce.

Protecting Her in Divorce

One wonders how far Sallie would go in this divorce and how Charles would handle the emotions of her attacks in addition to his own trial for polygamy. She filed a lawsuit against him in 1886.

He was in Canada in 1890 when his feelings of frustration and isolation climaxed to the point that he visited with his lawyers, Charles C. Richard, Henry H. Rolapp, and a Mr. Barton. After that meeting he decided to take his chances in the US courts, so he returned to Logan. He was going to fight for his freedom. His own father was so concerned that he “came stalking to my bedside” one morning and he asked why Charles had come, to which he responded that it was for “liberty.”[118] He laid out his defense for his father, wives, family friends, and church leaders, and with their approval, he voluntarily surrendered to the marshals at 2:00 p.m. on Wednesday, 23 July 1890. He took the train with his captors to Ogden, where he was arraigned, posted a $1,500 bond ($37,745), and was set free to await trial. He retired late that evening to “enjoy my first nights repose of freedom for 4 years. Thus, the Lord opens the way. He opened my way of escape 4 years ago and now has opened my way for liberty with less sacrifice.”[119] The lawsuit indictment carried no gains for Sallie, other than spite, but she was the prosecution’s chief witness. The charge was that Charles “did unlawfully, live and cohabit with more than one woman as his wives,” contrary to the laws of the United States.[120]

It would be nearly Christmas before Charles would have his day in court on Monday, 22 December 1890 at 10:10 a.m. Sarah Jane and Sallie were called as witnesses, but they were late. Sarah’s train had delayed her arrival by twenty minutes, but Sallie did not appear until 11:00 a.m.—a move that worried the prosecution and irritated the judge. Sarah was the first witness. She was nervous and apprehensive, but Charles had faith in a blessing he had given her earlier comforting her that she could endure the ordeal. “She was put on the stand and nagged for 1/

Even under these pressures, Charles protected his ex-wife, Sallie. His attorneys had obtained a marriage certificate documenting her marriage to Benjamin Ramsel. They turned to Charles asking excitedly, “Shall I fire that in now?” Charles declined to use the evidence against Sallie, including the marriage certificate and testimony of three other known affairs in which she had engaged during her marriage to Charles. When asked the reason for the divorce, Sallie responded, “We did not agree upon religious principles.” Charles sat quietly, said nothing, but wrote, “She was correct, for she desired a plurality of men and I practiced only with my wives that I had taken by the Laws of God.” The last witnesses were Mark Fletcher, whom Charles called “his avowed enemy” and N. W. Crookston, a former Logan marshal but a friend to Charles. The two witnesses contradicted each other in their answers, and in answer to Charles’s prayer, the prosecution rested. And Charles was acquitted. The case had “insufficient evidence.”[122]

Even in this emotionally charged court environment, Charles’s heart and faith led him to a higher ground. He did not defame Sallie. In fact, he protected her from public humiliation. In a literal sense, the case against Charles was true, according to the laws of the land. The evidence against Sallie was also true but would have embarrassed and crushed her and his children Charles Jr. and Jennie, as well as the Birdneau family, who were among his friends in Logan. Charles had always counseled against the spirit of contention in anyone, urging humility and faith, and seeking the Lord in prayer.[123]

Temples in Card’s Life

The work and dedication of the Logan Temple in May 1884 reflect Charles’s heart in unique ways. It was through his pioneering legacy as superintendent of construction that the fourth temple was built by the Church. His leadership brought him into contact with multitudes of people whom he asked to dedicate their time and talents to complete the work. The temple was a spiritual experience in solemn, symbolic learning in which his heart and soul were touched.

During construction, parents and leaders urged small children to save their nickels and donate them to the temple fund. One day, a small child showed up at the construction site and climbed up on the construction walls. He wanted to see where his nickel was going. Thinking of the child’s safety, a worker turned the child away sorrowfully. Charles saw the interaction and the disappointment in the boy’s eyes, and he took the youngster on a private tour.[124]

After the dedication of the Logan Temple, one might expect that the superintendent would want to be among the first to receive the blessing of the temple, but Charles did not. Perhaps he sought to put others before himself. He witnessed the three dedicatory services of the temple and watched as the blessings were bestowed upon others. He had opened the way for the Lord to confirm the blessings. “While sitting there [in the temple] nearly noon Pres[ident] George G. Cannon bade me to go and get myself and wife ready to receive our 2nd anointing.” Charles and Sarah Jane Painter were “the first to receive their 2nd anointings in the house of the Lord.” He returned home in “joy.” It had been seven years since Brigham Young had called Charles as superintendent, so when the temple had been finished and dedicated, Charles declared, “Great is my joy and satisfaction in beholding its completion.”[125]

The Logan Temple was one of the most significant achievements of Charles’s life. However, it would not overshadow eighteen years of service in Canada where again friends and family were relocated in protection from persecution. There, he established the foundations for new communities, regional irrigation, and another temple, the first built outside of the United States. His wives would attend that dedication in 1923, but Charles would not. He passed away on 9 September 1906.[126]

Unceasing Diligence

On 12 September 1902, Charles was released from his Canadian Mission, which had started in 1886. He presided over the Cache Valley Stake from 1883 to 1890 and over the Canadian Mission, including the Alberta Stake, from 1886 to 1902. The Canadian Mission during the early settlement period was actually considered a part of the Cache Valley Stake. He was praised for his unceasing diligence. The Deseret Evening News noted, “His name will never be forgotten, but upon history’s pages we shall find him chronicled as the ‘Pioneer of southern Alberta and the Father of Cardston.’”[127]

Charles’s work ethic and his determination, as well as the unusual pressures of persecution and travel, eventually wore him down, causing his health to deteriorate. In 1903, he and Zina were living in their new two-story brick home in Cardston, but they did not enjoy it long.[128] In December, Charles turned his business affairs over to his son Joseph and left Cardston for Cache Valley on a stretcher. He was critically ill. He had never slowed long enough to rest and recuperate before he was up and back at it. For almost sixteen years he had been on the rough roads of southern Alberta and Cache Valley, Utah. After he was released from his Canadian mission, he made the decision to return to Logan, where in August 1903, he retired. He occasionally attended the temple. He also had been ordained a patriarch and spent much of his time blessing others. He lived primarily with Zina and Lavinia, who cared for him until his death on 9 September 1906. It would be his Canadian family who would remain and carry on his legacy and assure his name continued in history.[129]

Notes

[1] A. A. den Otter, “A Congenial Environment: Southern Alberta on the Arrival of the Mormons,” in Card et al., The Mormon Presence in Canada, 53–74.

[2] The terms “North-West” and “Northwest” are both correct. The former refers to British colonial times and the latter to any time after 1912.

[3] Anthony W. Rasporich, “Early Mormon Settlement in Western Canada,” in Card et al., The Mormon Presence in Canada, 136–49.

[4] Alex Johnson and M. Joan MacKinnon, “Alberta’s Ranching Heritage,” Rangelands 4, no. 3 (June 1982), 99.

[5] Johnson and MacKinnon, “Alberta’s Ranching Heritage,” 99.

[6] Provinces in Canada are the equivalent of states in the US. The House of Commons is a legislative body of the Canadian national government, somewhat equivalent to the US House of Representatives but with more power.

[7] Doug Owram, Promise of Eden: The Canadian Expansion Movement and the Idea of the West, 1856–1900 (University of Toronto Press, 1980), 79–100.

[8] Hugh A. Dempsey, Indian Tribes of Alberta (Calgary: Glenbow Museum, 1997), 26–33.

[9] Owram, Promise of Eden, 1–3. See also W. Keith Regular, Neighbors and Networks: The Blood Tribe in the Southern Alberta Economy, 1884–1939 (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2009), 35–69.

[10] Donald Ward, The People: A Historical Guide to the First Nations of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba (Markhan, Ontario: Fifth House, 1995), 25–26; 42–44.

[11] A. A. den Otter, 161–2; 110–11; 183–87. See also R. F. Bowman, Railways in Southern Alberta (Lethbridge: Lethbridge Historical Society, 2002), 7–8; Map, 36.

[12] Mike Mountain Horse, My People the Bloods (Calgary: Glenbow-Alberta Institute and Blood Tribal Council, 1989), 1–3, 105.

[13] Dempsey, Indian Tribes of Alberta, 27–28.

[14] Hugh A. Dempsey, Red Crow: Warrior Chief (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan: Fifth House, 1995), 15–17, 75–77.

[15] Dempsey, Red Crow, 197–99.

[16] Dempsey, Red Crow, 159–61, 183–89.

[17] W. Keith Regular perpetuates the rumor that the Mormons acquired the land for settlement by “getting Red Crow drunk.” He offered no substantiation for the charge. In fact, the evidence provided through Charles Card’s diaries more accurately suggests that Card had nothing but respect for the First Nations people. He continually described them positively but was not so kind in his descriptions of the white whisky smugglers. See Keith Regular, Neighbors and Networks: The Blood Tribe in Southern Alberta Economy, 1884–1939 (Calgary; University of Calgary Press, 2009), 26. For an example of Card’s descriptions of the First Nations people, see Godfrey and Card, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Canadian Years, 24 October 1886.

[18] A provincial premier is the equivalent of a US state governor.

[19] For those interested in reading more about Haultain, see Grant MacEvan, Frederick Haultain: Frontier Statesman of the Canadian Northwest (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan: Western Produce Prairie Books, 1985).

[20] E. Alyn Mitchner, “William Pearce: Father of Alberta Irrigation” (unpublished master’s thesis, University of Alberta, 1966), 3, 33, 48–40.

[21] den Otter, Civilizing the West, 92–93, 203–6.

[22] den Otter, Civilizing the West, 165–66, 206–11.

[23] Leonard J. Arrington and Davis Bitton, The Mormon Experience: A History of the Latter-day Saints (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 183–4.

[24] Arrington and Bitton, Mormon Experience, 69, 183–85.

[25] See Brigham Y. Card et al., eds., The Mormon Presence in Canada (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1990). See also Nelson, Mormon Village, 219–20; Thomas Cottam Romney, The Mormon Colonies in Mexico (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2005); and Grant Underwood, ed., Voyages of Faith: Explorations in Mormon Pacific History (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2000).

[26] John Taylor to Charles O. Card, 10 July 1885, CR 1 10, Historical Department Church, Archived Division, Church History Library of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah, hereafter referred to as CHL. The government eventually returned the property it had taken over, but with an added cost.

[27] Charles Ora Card to John Taylor, 15 August 1886, John Taylor Papers, CR 1 180, CHL.

[28] For the contrasting experience of those who left Cache Valley for Mexico and Arizona, see Thomas Cottam Romney, The Mormon Colonies in Mexico (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2005); and James H. McClintock, Mormon Settlement in Arizona: A Record of Peaceful Conquest of the Desert (Phoenix: Manufacturing Stationers, 1921).

[29] John Taylor to Charles O. Card, 19 August 1996, John Taylor Papers, CR 1 20 DKS, CHL. Letters are reproduced in Godfrey and Godfrey, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card, 566–69.

[30] Charles Ora Card to John W. Taylor, 8 September 1902. John Taylor Papers, CR 1 20 DKS CHL.

[31] The Sterling Williams manuscript is quoted in Hudson, Charles Ora Card, 83. See also Jane Eliza Woolf Bates and Zina Alberta Woolf Hickman, Founding of Cardston and Vicinity—Pioneer Problems (Cardston: William L. Woolf, 1960), 1. Bates and Hickman blend Card’s diaries with their own records of historical events in the manuscript that was edited and published by her sister Zina. The Woolf family was among the first to follow Card into Canada.

[32] John Taylor has British roots. His family had emigrated to Canada from Britain in 1830. By 1839, they were living in Toronto, and a missionary, Parley P. Pratt, baptized the family. See Paul Thomas Smith, “John Taylor,” in Leonard J. Arrington, ed. The Presidents of the Church (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1986), 75–114.

[33] Francis M. Lyman was a member of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles. Stewart was President of Brigham Young College and a friend. See Godfrey and Card, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Canadian Years, 1886–1903, 14 September 1886. See also Charles Ora Card to John Taylor, 8 September 1902.

[34] Charles Ora Card to John Taylor, 2 November 1886; and 27 January 1887, John Taylor Papers, CR 1 180, CHL. In the 2 November correspondence, he indicates that he had $750, and on 28 January, he reports that the total was $770. George’s daughter Clarice would later connect with the Godfreys. “Trustee” refers to the President of the Church as a corporation. “Trusts” refers to accounts the president administers and to which he has free access. A Trustee in Trusts provides a manner in which religious corporations can conduct business transactions. Arrington, The Great Basin Kingdom, 431.

[35] Zundell assisted the First Nations people in digging a canal from Samaria to Washakie. He also taught in the Portage Branch. See Gale Willing, Fielding: The People and Events That Affected Their Lives (Logan, UT: Herff Jones, 1992), 14–15, 173, 209.

[36] Jenson, Encyclopedic History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1312.

[37] Godfrey and Card, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Canadian Years, 1886–1903, 14–17 September 1886.

[38] There was no evidence to tell whether or not Zundell knew he was about to be a part of this exploration party. It would appear he did not know. However, his services were indispensable because he knew the native peoples and their languages. Card writes on 10 October 1886 that they each wrote in their journals, but the journals of Hendricks and Zundell were not located at the time this book was written.