The Modern Canadian West

Donald G. Godfrey, "The Modern Canadian West," in In Their Footsteps: Mormon Pioneers of Faith (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 251–284.

Foundations for modern families are laid in the footprints of their ancestors and the communities in which they lived. The horse-and-buggy frontier West was almost behind the times, and the modern West was just ahead. Family pioneers experienced civilizations in transition: from handcarts to horseback, and to oxen- and cattle-drawn wagons. Uncharted trails became wagon roads and immigration and trade routes. The Industrial Age provided automobiles, new farm machinery, and a film and radio industry. It introduced the telephone and electricity into homes.[1] Railroads created faster transportation and trade. By the late 1800s, trains had become the first mass rapid transit system.[2] Families often used the rails,[3] for even in those days it was certainly faster than the horse-drawn carriage. The Canadian Pacific Railway connected Canada, just as the Union Pacific connected the United States.[4] The Canadian version of the golden spike was driven at Craigellachie, British Columbia, on 7 November 1885, just one year before Card, then forty-six years of age, would board for his famous trip from Kamloops, British Columbia, to Calgary, Alberta.[5]

The Roaring Twenties were exuberant years. They were a release from the earlier sufferings of World War I. During World War I and the Twenties, Floyd Godfrey and Clarice Card grew from children into working adults. They experienced the tensions of WWI, the terror of the Spanish flu pandemic, and the boisterousness of the 1920s. In contrast, the Great Depression hit like a hammer as the economy fell out from under the nations of the world. There was little cash, so barter and trade in kind became the manner of conducting small-town business. Salaries were cut, taxes went unpaid, and people, families, and governments found themselves struggling. Many of those employed before the stock market crash were making less than 50 percent of their previous wages, even four years later.[6] These were the years that would launch the next family generation.

Wedding: The Godfreys and Cards

By 1926, Floyd had completed school; he was working at the Magrath Trading Company and the Empress Theater. He was saving his money as best he could and preparing for marriage. His only expenses were clothing and dating. Clarice worked as a clerk in the Jensen Brothers Mercantile Company.

Getting permission and preparing for marriage was nerve-racking, yet fun. By 1927, Melvin had started building his third home uptown on Main Street and was moving one last time. Word was getting out about Floyd and Clarice, and Melvin asked Floyd if they wanted the old Godfrey house after they were married. The answer was yes. Now Floyd just had to muster up the courage to ask Clarice’s father.

Everyone could see the direction the courtship was headed, but Floyd was still nervous about approaching George Card. One spring morning, George went to his farm and came back to town with a team of horses so he and Floyd could plow the garden on the old Godfrey property for the summer garden. George was driving the team and Floyd was holding the blade deep into the soil as he turned the dirt and gathered his courage. He tried to work his question into casual conversation, but blurted it out: “Mr. Card, Clarice and I would like to get married. What do you think about that?” Floyd never forgot his response: “What in the hell do you think we’re plowing this garden for, Floyd?”[7] And that was how Floyd received permission for Clarice’s hand.

Floyd was twenty-one and Clarice was twenty when they married. Clarice had $27.40 ($360) in her savings. Floyd had his jobs at the trading company and the theater. The day before their wedding, 7 June, they caught the train to Cardston. Unusually heavy rain had been pouring for several days. As they rode, they listened to the railroad ties sloshing in the wet soil, splashing the water over the tracks as the ties sunk into the railbed. But Floyd and Clarice had no worries. Happiness, excitement, and anticipation were the emotions they shared. They were met at the Cardston Railway Station by Clarice’s uncle, Joseph Y. Card. The day before their wedding was spent in preparation, obtaining their wedding license, and visiting with Clarice’s extended family—Joseph Y. Card, Hugh B. Brown, and Zina Card-Brown.

On 8 June 1927, “They were joined together in the Holy Bonds of Matrimony according to the Ordinance of God and the Laws of the Province of Alberta at the Temple in Cardston.” Joseph Y. Card performed the sealing ordinance, which was witnessed by James Hanson and William Henderson.[8] That evening, Joseph held a family reception at his home. It was a small family gathering but a joyous occasion. People were poor and could not give much to the newlyweds, but if Floyd and Clarice got even a dish towel as a gift, they were grateful, because they had nothing. As they were returning to Magrath the next day, a friend, “Dad” Hudson, sprinkled them with wheat as they stepped off the train. The round-trip to Cardston was their only honeymoon.

The young couple went directly to work and began preparing their home. They cleaned the old Melvin Godfrey house, 155 South First Street West. This home of Floyd’s childhood would now be the first home of their family. They furnished it with borrowed hand-me-downs and homemade furniture. They had a couch, a table, two bow-backed chairs, a woodburning cook stove, a cupboard, a bedroom chest made of boxes, and a bed.[9] George gave them a cow and a calf for milk and beef. It was meager, but it was a beginning.

A Loving and Learning Partnership

Lessons of life and marriage progressed in the jubilant times of 1927, 1928, and into 1929. A year after they married, Floyd and Clarice joined with friends and headed to the Raymond Stampede for a day of fun. Their savings had grown to $45 ($597) with which Clarice had hoped to purchase a bedroom dresser she needed. Their first dresser was made from cardboard boxes, wallpaper, and a cotton curtain with a mirror hanging from the wall. For the stampede, they thought they might use a little cash from their savings, so they took it all with them.

As they passed through the gates of the stampede grounds, walking along the circus sideshows, Floyd stopped to play a little “Crown and Anchor.” It should be noted that the Crown and Anchor was a gambling concession. In this game, the player rolls the dice, and when the symbols on the dice match those on the playing mat, the player wins. If the symbol doesn’t match, the player loses the bet. He won, tried it again, and then again. He worked their $45 up to having $85 ($1,126). The group strolled through the concessions and finally took their seats in the grandstands as the rodeo began. All the while Floyd’s winnings were “burning a hole in [his] pocket,” as he used to say. All he could think about was winning the cash to purchase the dresser. So he excused himself from the group, hurrying back to the Crown and Anchor.

Floyd ended up losing all of their savings! Dejected, feeling guilty and nervous, he slowly made his way back to Clarice, who was still watching the rodeo with their friends. He pondered just how he would tell her what he had done. When he told her, she cried and was not too happy with her husband. Floyd felt so deflated the next morning that he went to the Trading Company and made arrangements to purchase the dresser on credit, promising to pay $5 ($66) a month. Clarice got her furniture, and Floyd learned a valuable lesson.[10] They would later laugh at each retelling of the story.

Kenneth Floyd was born at home ten months after the wedding, on 28 April 1928. Dr. Douglas B. Fowler and nurse Sarah Polson attended the delivery. As Ken took his first breath, Nurse Polson hollered, “Come in here, Floyd, and see what you have been doing.” The doctor appeared at the door, however, and directed the new father to “stay out” in the kitchen.[11] All was well. Arlene Janet followed Ken sixteen months later on 13 September 1929. Both were born in Magrath. Floyd said that Arlene Janet was “our pride and joy. We sure did spoil her.”[12] Less than a year after Arlene’s birth, Clarice was in the hospital for the first time in her life to have her appendix removed.[13] Nonetheless, another daughter named Marilyn Rose was born three years later on 12 January 1932, with Lorin Card following not too long after on 22 July 1933. It was a busy beginning to their marriage. Within in six years, the couple expanded to a family of six. All of the oldest four children were born at home. Two more would surprise them later.

Community Dramatics

Live local theater was a part of community entertainment. The Magrath Home Dramatics were under the direction of Louisa Ann Taylor.[14] Taylor directed a dozen or so actors and actresses, including Floyd, and they performed various three-act plays. It was a carefully selected group of young adults. Allowing too many people to participate resulted in goofing off that made control harder during rehearsals. Mrs. Taylor took her dramas seriously, and she expected the same from her actors and crews. The scripts were handwritten. Practice involved long weeks of memorization and rehearsal. Taylor always teased the lighthearted Floyd about practicing his lines: “When you learn your lines, please learn them correctly, so that you can cue the person following you. . . . Don’t you know it is impossible for them to follow you if you don’t give the right cues?”[15] Her reminders were necessary because Floyd was too good at improvising. Plays were enjoyable winter activities when life slowed on the farm.

Floyd enjoyed his part in community dramas, and sometimes he brought his family to watch. In one play, he was the general of an army. He had a uniform and a sword hanging at his side. He was to clash with the enemy in a climactic duel. Though makeshift wooden swords had sufficed in rehearsals, these swords were real, acquired from local veterans who had fought in real battles and who expected the swords returned. Floyd’s opponent was a short fellow, his friend “Dad” Hudson. Dad Hudson had borrowed a long sword and scabbard. Floyd and Dad, the opposing general, approached each other to fight it out, delivering their lines with bold, exaggerated anger, challenging each other to draw the sword. Floyd was taller and swiftly drew his sword, but Dad Hudson suffered an equipment malfunction. His sword was so long and his arms were so short that he couldn’t pull it out. Floyd could have “run him through ten times before he drew his sword.” The audience broke into laughter; the actors were embarrassed, but everyone had a good time.[16]

Young Kenneth, who had just turned four years old, came to see a performance in which Floyd was the hero. The actors had scheduled a full dress rehearsal as a matinee. They watched through a small half-inch hole in the curtain as parents and sweethearts arrived, filling the auditorium. Children and families were specially invited to this afternoon performance. The actors dressed in costume, with the makeup artist having “really done his work well . . . with greasy paint and powder.” Floyd did not think anyone would ever recognize him. The hero strutted confidently toward center stage as he delivered his lines. At just the right moment, as if on his own cue, little Kenneth got up from his mother’s lap, walked straight to the front of the auditorium, looked barely over the top of the stage, and hollered, “Hello, Daddy,” in a voice heard throughout the hall. The crowd roared.[17]

Floyd and Clarice had a young family, but they still enjoyed going to dances and gatherings with friends who were also getting married. Floyd’s participation in local dramatics continued, and they were active in their church. Between 1927 and 1935, Floyd was called to serve as the resident of the Young Men’s Mutual Association, a local church program sponsoring youth activities and teachings.[18] He was ordained a Seventy, served as the Quorum of the Seventy secretary, and served as the secretary of the Melchizedek Priesthood committee.[19] He starred in local dramas and felt guilty about leaving Clarice alone with the children as he was off in rehearsals. However, she didn’t mind too much because she was kept busy working in the Primary.

The Great Depression Hits Home

A month after Arlene’s birth, the world of Floyd and Clarice changed drastically from the frivolity of the Roaring Twenties to the depths of the Depression. On 29 October 1929, the Great Depression hit families like a massive landslide. It buried every individual in unforgiving debt and hardship and choked the life and work from its victims. It was a catastrophe of international consequences, shaking the economy of every nation, state, and province. Alberta’s per capita income dropped from $548 ($7,259) in 1928 to $212 ($3,710) by 1933, a drop of 61 percent.[20] Floyd’s salary at the Magrath Trading Company was cut in half, dropping to $0.18 ($3.15) per hour.[21] Four months before the crash, Floyd had started to build a new home at 145 South First Street West, south of Main Street and only a few doors south of his father’s home.[22] This is the home where Marilyn and Lorin would be born. Floyd was twenty-three years old. Out behind the house, in the barn, they kept two cows. In the morning, the cows were milked and put out in the morning to graze with the city herd. The herdsman returned the cows each evening, and Clarice herded them back into the barnyard. If they weren’t cooperating, she had to run up and down the alley trying to catch them. The cows provided milk for the family, and extra was sold to the neighbors. With the economic disaster settling in, debt and declining wages made it difficult for Floyd to pay even the interest on his home construction loan and the related property taxes. By 1935, he was asking the town to consolidate back taxes owed in the amount of $171.25 ($2,824).[23]

Floyd and Clarice almost finished their new Magrath home during these difficult few years. It was completely framed, roof and walls were in place. The outside was stucco and held tiny flecks of glass, giving it a reflective glitter. The family was anxious, and they moved in before the interior was finished. The children’s Grandfather Godfrey gave them Hollywood movie posters to cover wall studs. They had no concern for the bare walls, but a movie poster was exciting, and no one else in town had them. There was a hole in the floor in one room where the children climbed down into the basement. There was a chemical toilet in the upstairs and likely one outside as well.[24] Still, paying the mortgage on the construction was a challenge for Floyd and Clarice during the Depression.

Floyd and Clarice were not alone in their struggles. Values on a farmer’s crops and a rancher’s cattle hit rock bottom. It was impossible for many farmers to pay for expenses out of the meager returns from the crops, if they got any returns at all. Added to this economic upheaval, in 1930, southern Alberta was coping with drought conditions, and harvests were few. It was a time people could not forget but hoped they could. Alberta’s stake president, Edward J. Wood, called for a day to be set apart for a “special fast for the preservation of our crops.”[25] Church members were asked to abstain from food and drink while praying for moisture.[26] All local Cardston Seventies, including Floyd’s brother Bert, were called to the temple for a special prayer circle.[27] “I don’t know who was the mouth, but we were in there for about three hours. . . . I lived one-half block north of the temple. The rain was pouring down so hard that I was soaking wet by the time I got home, now that is an answer to prayer, my dear children.”[28]

Life moved forward as the Great Depression directed. It was busy, and it was physical. During summer vacations from the trading company, Floyd borrowed the wagon from his father-in-law and drove the team north of Magrath about twelve to thirteen miles to Pothole Creek, where he dug coal for the winter. It was hard manual labor. A lump of coal as large as a kitchen table was maneuverable in the water, but when the second workers got it above water, its weight was immediately apparent. They broke it into manageable pieces with a pick and a shovel and threw it into the wagon box, then hauled it home.[29] This was a soft, dirty-burning coal that left a lot of ash, not the hard, long-burning coal of the nearby Lethbridge mines. But there were no complaints. The soft coal was available for the digging. So, with intensive heavy labor, Floyd hauled ten tons each year. This was sufficient to keep his family warm through the winter.

Hay and grain for their animals was hauled from the Card farm, where Floyd helped his father-in-law cut and stack it. He was paid for his labor in feed for his cow. Cattle was essential on every farm. Cows were a food supply—milk, cream, and a new calf each year that supplied the family with meat. Even Ken contributed, as he was now old enough to fill his wagon with fourteen quarts of milk and haul them to the train station, where he was paid $1 ($17). It was much-needed money, as Floyd was only earning $1.50 per day at the trading company.

Wheat from the Card farm was taken to the nearby Rockport Colony, where the Hutterites ground the grain into wheat and pancake flour.[30] If there was a charge for the service, it was probably an exchange in kind, meaning the Hutterites would take a part of the wheat in payment and grind it for themselves.[31] Beef also came from the Card farm. Vegetables from their own garden were all tended to maturity, harvested, and preserved. Ice for perishable food was still dug from the creek. This time Floyd was not a spectator, as in his youth, but among those cutting, lifting, and hauling.

The year 1935 was particularly dry, another drought adding to the woes of the Depression. It was so dry that little hay was produced for the cattle, so Floyd improvised. He purchased some oat straw and filled his barn. Then he went to the Raymond Sugar Factory and bought sugar beet pulp and molasses. Two dollars ($34) loaded the wagon to the point that it was difficult for the horses to pull the load. The round trip took all day, the distance being ten miles from Magrath. He covered the pulp with straw to keep it from freezing in the winter months. When the cows were ready for feed, he placed a few pitchforks of straw in the manger, then poured a stinky quart of pulp over the hay. “The cows loved it,” he recorded in his history. But it smelled, and it tainted the taste of the drinking milk. “After the cows had eaten, with the straw sticking to their noses, they looked like some strange creature from outer space with slick syrup and straw stuck all over their nostrils.” They tried to lick it clean, but it seldom worked. It was a nonfattening diet for the cows, like the healthier hay, but it pulled his family through difficult winters. George Card’s crop of sugar beets also produced a harvest of beet tops that were good cattle food. Floyd placed these in small piles all over his garden; each pile was just large enough for one feeding.[32]

Floyd kept his job at the trading company, and with the extra work, the family got along. Everyone in Magrath was living the same circumstances. Soup lines formed in the cities, and many people were on welfare. Floyd and Clarice thankfully were not. They were always proud of the fact that during their most difficult years, they “were never on [government] relief.”[33] It was in the middle of the Depression when Floyd and Clarice began considering moving to Cardston.

Life’s Turning Points

Floyd’s brother Bert was influential in convincing him to relocate his family from Magrath to Cardston. Bert had returned from his LDS mission, and he too struggled with employment, moving as work was available. He worked in one of the Magrath grain elevators until it closed because of the Depression. He moved to Cardston to operate the Cardston theater for Gordon Bremerton. He then moved up into Crows Nest Pass in Coleman, where he worked in the theater and the mines. Later, he returned to Cardston and established his own store.[34] He sold lemons for $.25 per dozen from Godfrey’s Groceteria. He had an ice cream parlor in the store, where his younger brother Douglas worked as a soda jerk.[35] Bert was also a sales representative for a Lethbridge funeral home.[36] He was active in the town business developmental circles and served as treasurer for the Cardston Board of Trade. Things were looking up for Bert in Cardston. By 1936, he was in a number of diversified fields. However, almost everyone was scrambling. He knew his younger brother Floyd was struggling in Magrath, so he reached out.[37]

By 1937, the Depression was still in control of everyone’s life, and World War II was approaching. Bert suggested that Floyd move to Cardston. “You can make a lot more money here than in Magrath,” Bert had told Floyd.[38] Earl and Hal Peterson had just constructed a complex for Texaco Oil in Cardston at 195 Main Street. They built a new large warehouse and bulk storage facility, which included the service station.[39] So in March 1937, Floyd turned his Magrath home back to the Lethbridge lender, cleared his debt, resigned from the Magrath Trading Company, and moved to Cardston. He took the job of managing the Cardston Texaco Service Station, which still stands on the north Cardston hill across from the Cahoon Hotel, 211 Main Street. It was apparently a quick decision that caught the Magrath Trading Company staff by surprise. They promised him a “rip-roaring ding-buster party” as soon as he was available, “for there’s no one who is entitled to it more that good old Floyd.”[40] True to Bert’s prediction, moving to Cardston more than doubled Floyd’s wages, from $40 per month to $90 ($652 to $1,467).[41]

Cardston Auto Service

Old Floyd was thirty-one at this essential transition of his life. A month later, in the first week in May, Floyd made arrangements to move his wife and four young children to Cardston.[42] Kenneth was nine; Arlene, eight; Marilyn, five; and Lorin, three.

The advertisements began appearing in the Cardston News in mid-March: “Announcing New Management of Cardston Auto Service, Floyd Godfrey.”[43] Douglas Godfrey said that “Floyd looked sharp in his Texaco uniform.” The new job matched the standards Floyd maintained in the station, along with his quality of customer service and the work habits he had learned at the trading company. The operations of the station were oil changes, light mechanics, gasoline, and service. This service included filling the customer’s tank with gasoline, checking the tire pressure and oil levels, and washing car windows. The station’s advertising emphasized 100 percent efficiency. There were three or four employees. In less than a year, the business had shown an increase of 65 percent.[44]

Cardston Auto Service, circa late 1940s. Courtesy of Glenbow Museum.

Cardston Auto Service, circa late 1940s. Courtesy of Glenbow Museum.

Floyd was a progressive manager. He installed a new Alemite grease cabinet and a Lincoln grease gun.[45] The station grew beyond just auto service. They sold automotive parts, batteries, and electronics; new Sparton radios for 1938 model cars; and even the “Norge Rollator Refrigerators.” By 1939, the Texaco station was the agent for the new Pontiac automobiles. The Cardston News advertisements all concluded with the bold line “Cardston Auto Service, Floyd Godfrey, Phone 20.” The number 20 was the phone number of the station.

As Floyd’s family adapted to Cardston and the Texaco station grew, all the children pitched in. Ken helped clean the mechanics area; Arlene and Marilyn cleaned the toilets, sinks, mirrors, and floor; and Lorin flittered around or generally stayed home with their mother, which history says their older siblings did not much appreciate. Cleaning the restrooms was the “yucky job,” so Floyd paid his daughters $0.25 ($4.08) to split between them when they did this job.[46]

Like his children, Floyd did not enjoy the service station job. He was progressing, and business was expanding, but the Texaco regional management often popped in unannounced and headed back to where the mechanics were working. They fostered contention. If there was a single spot of oil on the floor, they hollered and cussed out the mechanics with whom Floyd worked. It was a needless show of authority that disrupted the operations.

The station opened early in the morning and remained open until all the other businesses in town—including the movie house—were closed, just to sell a few gallons of gas at 10 cents ($1.63) a gallon.[47] One evening as Floyd was closing up, a rough-looking character entered. Floyd told the gentleman that he was just closing and ready to lock up. The man responded that he just wanted to use the restroom, so Floyd waited for him outside the door. It had been a successful day, and Floyd had the cash in his pocket, ready to take home and then to the bank the following morning. When the fellow reappeared, Floyd locked up, but the man seemed to hang around a bit longer than Floyd thought normal. It was uncomfortable. Floyd started walking home, and the fellow followed for three blocks. Afraid a robbery was on the mind of the vagrant, Floyd offered a silent prayer and began to run. He made it home, and the frightening affair passed without incident. Thanks to an answered prayer and something extra in Floyd’s quickstep, he was safe.[48]

Floyd missed the hardware business. He had worked ten years as a clerk at the Magrath Trading Company. In Magrath, Floyd and Clarice’s families had all lived within a few miles, so the move to Cardston had not been taken lightly. However, if Floyd had stayed the course in Magrath, he might have lost his Magrath home and “worked for nothing all my life.” In Cardston there were occupational options, growth, and opportunities for entrepreneurship.[49] The challenges of the Texaco station and relocating to Cardston were a major turning point for the family. The move to Cardston did not mean life became easy, just that there were more choices.

Coombs Hardware

Forest Wood pulled Floyd back into the hardware business. Forest was the son of Edward James Wood, who was the first Cardston Temple president.[50] He had opened a hardware store in 1928, almost a decade before Floyd arrived in Cardston. He had partnered with Mark A. Coombs until 1942, when he purchased the store but retained the same name, Coomb’s Hardware.[51] Visiting the hardware store one day in the late 1930s, Forest invited Floyd to join him at Coombs Hardware. He offered him a job, and Floyd took it.

Coombs Hardware was a bit of a contrast to the Magrath Trading Company. In Magrath, Floyd had learned the importance of keeping the store clean, clear of clutter, and in order. Coombs Hardware was “anything but in order.” So Floyd set about constructing new merchandise displays. As he thought himself “half a carpenter,” he constructed new shelving, painted, and began to attractively arrange the store’s inventory, which included everything from farm tools to fine china. Forest’s father, Edward J. Wood, was the Alberta Stake president (1903–42), then the temple president with the dedication of the Cardston Temple on 26 August 1923.[52] Edward J. Wood was so pleased with Floyd’s work that he offered to help Floyd purchase eighty acres of land on the Glenwood Irrigations District if he would remain at the hardware store.[53] Floyd had a lot of respect for a man in the dual role as his stake president and temple president.[54] Floyd would stay in the store for a few more years, but he was not interested in work of the farmer. From his youth, he had enjoyed the role of merchant.[55]

Cardston Implement Company

In 1941–42, Floyd went to work for Kirk Lee. Lee had purchased the Cardston Implement Company. He had seen what Floyd had done for Coombs Hardware and asked him to do the same thing for him.[56] Floyd agreed. The implement company was a little different from Coombs in that it had small furniture on display on the second floor. Cardston Implement was a business fitting the “needs of your Home and Farm, Bringing the Spring into the Home,” which meant an inventory of spring-filled chesterfields and sofas, electric washing machines, electric irons, wash boilers, tubs, tools, saws, rugs, hardware, and bicycles. By February 1942, Floyd had taken over as manager from Alf Strate.[57]

The Brown House

The first Cardston home of Floyd and Clarice Godfrey was affectionately called “the Brown House,” a rental up a small hill a half block from the northwest corner of Cardston Town Square. It was owned by a Mr. Gooding Brown, who lived next door. There were two rental units in the Brown House. Lilly Gregson Archibald, her daughter Donna, and several others lived in an adjoining modest unit during the years Floyd, Clarice, and family occupied the larger unit. It was a small house, but it accommodated the needs of their family. The four Godfrey kids slept in two double beds in the northwest corner room of the house. It was cold in the winter. Getting warm and ready for bed meant the children took their pillows out into the living room, at the north end of the room, where their dad stoked a red-hot fire to last the night. They held their pillows toward the stove, a puffin-billy, letting them absorb the heat and then dashed into their beds, hugging the pillows. In the summer, they enjoyed the cool of sleeping on the porch. The only fear was of the wandering “Black Aces,” which “scared the dickens out of us . . . [and] woke-us-up telling us they were ‘going to get us’ and take us somewhere.”[58] The Black Aces were a group of young men, perhaps a year older than Ken, hoodlums of the day, bullies in today’s vernacular. They dressed in black and cruised around neighborhoods frightening the younger children, climbing the walls of the temple, and acting a little more mischievous than usual. As the oldest, close to the Aces age, Ken knew who they were. He was unafraid and protected his younger sisters and brother. The Black Aces eventually faded, and home remained the family center for playing, cooking, and eating. Life was good. There was even an indoor bathroom in the southwest corner of this house.[59]

The barn and a root cellar were out back, just east behind the house. They were childhood magnets. Their Uncle Bert kept greyhounds in their barn along with their own cow and a few chickens. One of Ken’s jobs was beheading the chickens, and he drafted Arlene and Lorin to hold the legs, trying to keep the victims steady on the chopping block. Then grabbing them before they ran, headless, underneath the chicken coop. The root cellar was just like the one they’d had in Magrath, except this one filled with water every spring.

Just out the kitchen door was a cesspool that smelled like an aging sewer. It was a septic tank, as there was no central town sewage-treatment system in town. So, if the home had an indoor bathroom, the sewage was stored in the tank, which was emptied periodically. Without a lid, it was dangerous. The wood sheet covering the pool was rotting. One day the kids’ dog, Sport, fell in. As the children rushed to the hole, their mother saw them and hollered to stop. Otherwise, a little one of her own might have joined Sport in the pool. The dog was rescued. Clarice gave it a bath, and the landlord covered the cesspool. Sport survived his fall into the sump, but he did not survive the passing cars he loved to chase. It is the way of childhood pets. Floyd consoled his children and promised they would have Sport in the hereafter, and soon another dog came into the family.

Home and community gardens were a significant means of food, especially during the Depression. Gardening was not a hobby; it fed the family. Community gardens in Cardston supplemented the large family garden plots that came with every house. The community garden was down near the Smith Dairy, along Lee’s Creek. Every week during spring and summer in the Depression years, families planted, weeded, and harvested potatoes, corn, peas, and beans. The Church had a simple steam canning system people used to preserve the harvest. When corn was ready, the parents had to get it canned before the kids had eaten it all. For them the harvest included the following: cook the corn; add salt, pepper, and butter; then eat away. The family worked their part of the garden with a group of friends, all of whom were LDS and belonged to their neighborhood study group.[60]

The Godfreys’ home garden at the Brown House was as large as their first Magrath home. Along the north end of the garden was a long row of gooseberries and chokecherry bushes—sour! But berry pies were Clarice’s specialty. All the preserves from the harvest were stored in the cellar with the vegetables. The cellar was a challenge each spring when it filled with water. The kids didn’t mind because they got into a galvanized iron wash tub, using it as their boat, and paddled across to the shelves, retrieving a bottle of fruit or the vegetables for their mother.

The family remained fiercely self-sufficient through the Depression and into World War II. Grandparents from Magrath visited, often bringing food as they could. The road went in both directions. They ate what they grew and grew what they ate. If they tired of beef, poultry, or pork, then they made a family outing of going fishing. They fished the Belly River where the irrigation water was diverted from the river into Payne Lake for the eastern farm and ranch lands. The stream sported fresh mountain suckers that were so plentiful these fish could be scooped up into large wash tubs, beheaded, washed, and cut into small pieces, which were taken home and bottled. In theory, this variety of sucker was different from their bottom-feeding cousins found along the junction of Lee’s Creek and St. Mary’s River. These Belly River suckers were eaten with a milk-cream sauce filled with peas and butter. The children’s description remains “yucky” even today, but in the Depression it was all they had, and they were happy to have it.[61]

There was a small garage at the side of the Brown House, but since Floyd had no car, the structure was a storage shed for coal and wood. The kids used the driveway as a small soccer field. A graveled street running north and south in front of the house was an extension of the driveway, adding to the neighborhood playground. Ken, Arlene, Marilyn, Lorin, and friends played baseball, soccer, and the childhood games of run-sheepy-run, tag, and hide-and-seek with the neighborhood. They built bonfires of dry autumn leaves, threw potatoes into the flames, and called it supper. There was a willow tree in front of the house to the side of the driveway. This was where Tarzan played.

World War II

World War II was a surreal experience, especially for the children. Families were glued to the new technology of radio, listening to the news of Edward R. Murrow; the speeches from the political leaders of the time, including William Lyon McKenzie King, Canadian prime minister; Winston Churchill, Great Britain’s prime minister; and Adolf Hitler.[62] Radio had quickly become popular, and as it was brought into every home, it linked the small towns and large cities together in a common experience.[63] World War II was frightening and set everyone in action. Even the children contributed by collecting tinfoil from anywhere, including gum wrappers, to recycle into the war effort. They came home from school selling “poppies,” which were pinned to the lapel of one’s suit, shirt, or dress, with profits going to the war effort. They sold “War Saving Stamps” for 25 cents ($4.10). The stamps were glued into small booklets, and at the end of the war the bank reimbursed them along with interest. Schools practiced evacuation drills and taught children how to get under their school desks for protection against falling bombs. It was just practice. There were no bombs dropped, but air raid drills took place overhead at night. The town lights were shut off. A lone plane flew over the town from the Pearce Air Training Base, north near Fort Macleod. It dropped a “bright flair that seemed to light up the whole town.” Within minutes, the squadrons followed, “hundreds of them” it seemed. They were noisy, flying low enough to almost touch the roofs of houses. It was nerve-racking as the family contemplated the reason for these activities, but “we all stood out on the front lawn and watched.” When it was over, the town lights switched back on, and the children went hunting for the burnt-out flair.[64]

Ironically, the war also brought people together, as all were supportive. Families seldom ate anywhere but home. Their three regimented meals were breakfast in the morning, dinner at noon, and supper in the evening. The movies promoted the war effort and for the most part were entertaining and inspiring. Movie fans of the time were shocked with Gone with the Wind, when Clark Gable, as Rhett Butler, said, “Frankly my dear, I don’t give a damn.” Swearing was taboo, but the movie was certainly a success.[65]

Cardston Home Central

The Brown House was Floyd and Clarice’s first home in Cardston as they became established in the community, making the transition from the Depression to World War II. Floyd and Clarice lived there for five years. It was the childhood home of Kenneth, Arlene, Marilyn, and Lorin. Their growing years were spent in the two Magrath homes, the Brown House, and a new one under construction. It was the latter where two more boys, Donald and Robert, would join the Godfrey flock.

In September 1941, Floyd applied for a building lot permit just south of the Thomas S. and Annie Gregson’s home. The lot cost $60 ($958).[66] Constructed during 1941–42, it remains standing today at 334 4th Street West. This was the family home for the next fifty years—from 1942 to 1992, home central for half a century.

The home was built by the hands of Floyd and Clarice, with the children helping as they could. Children cleared the debris from the property. Rusty cans were placed in a burlap gunny sack and hauled away. Floyd worked late into the night, when weather permitted, as the children watched from the Brown House for the bright electric light to go out at the construction site of their new home, knowing their father would soon return. Help came as well from the neighbors and church friends. Henry Noble dredged the basement with his team of horses. Alfred Schaffer and Brig Low aided roofing the house, and others shingled.[67] The first room constructed was the indoor bathroom, followed by the kitchen. The family moved in with only these two rooms completed. They lived on a rough floor, with nothing on the walls, just the raw 2 x 4 boards. Cardboard furniture boxes from the Cardston Implement Company were nailed to the walls, and before bedrooms were added, the walls were plastered with movie posters from their Grandfather Godfrey’s Empress Theater in Magrath.

Floyd and Clarice saved their money, adding rooms as they could afford it. When the home was finished, it consisted of the front room and two bedrooms, one on each side of the bathroom, with the girls’ room, to the east, still walled with movie posters and the master bedroom to the west. The boys slept in a small bedroom downstairs in the basement. There were bunk beds and a small closet built under the stairway where they hung their clothes. Upstairs, two back rooms were eventually added, a bedroom and sun room, plus a new rear entrance. This was part of the lifestyle of the times—a little at a time—neighbors helping neighbors and pay as you go.

Floyd and Clarice Godfrey, Cardston home. Courtesy of Marilyn Ockey-Pitcher.

Floyd and Clarice Godfrey, Cardston home. Courtesy of Marilyn Ockey-Pitcher.

The new house faced the town square to the west, and the Cardston Alberta Temple, almost in the backyard, was just to the east. The old clothesline was out the back door and down five steps. The loose wire strung with wet clothes ran between two short wooden poles, with six lines running parallel. Lugging a basket of wet laundry from the basement washing machine to the upstairs to hang them outside was a physical feat not for the faint of heart, but it was repeated by Clarice every Monday.

Monday was laundry day every week on every calendar. Dirty clothes were dropped through a clothing chute in the bathroom. They fell into the dirty clothes bin in the basement. The bin’s latched door opened, and the clothes fell onto a table for separating into whites and colors. Chips of soap from a homemade bar were added to the washing machine as it started. It was a new electrical model. Whites were washed first and afterward put through the wringer to squeeze out the water. After a rinse or two, the clothes were placed in a wicker basket; carried upstairs, outside, down the porch steps; and hung on the clotheslines east side of the house. Floyd later constructed a closer entry on the east of the house and stretched a long clothesline with a pulley system from which Clarice hung the washing to dry. This saved many paces and a few stairs. It was a nice change, out of the wind, where she simply stood on the porch, hung the laundry on the line, and rotated the lines on the pulley stretched from the steps over her summer flower garden to a tall pole at the other side of the yard. This was modernization. Monday’s winter laundry was frozen solid, but it was somehow dry when brought into the house. One load at a time, all day long, with loads of sheets, towels, colored shirts, and work pants.

Godfrey home, backyard view, winter 1955. Courtesy of Godfrey Family Files.

Godfrey home, backyard view, winter 1955. Courtesy of Godfrey Family Files.

The gardening traditions continued in the new house, but now there were two gardens. Floyd’s was the family vegetable garden. The first was just southeast, behind the barn. The plot itself was as long as the house, perhaps 30 x 60 feet. The noise of their father’s early morning work woke the sleeping children. Floyd was a proficient gardener. Years later, when the barn was dismantled, the garden moved to the north of the house. While planting, Floyd would leave a small play circle in the middle of a dozen rows of corn where his children could play.[68] A month or two after planting, the corn towered above their heads as they played in their secret hideout among the spiraling stalks.

Clarice’s garden was a beautiful bouquet of roses and honeysuckles, and a burst of all kinds of flowers. She loved this garden. The tiny red-white bleeding hearts provided a delicate contrast against the majestic gladiolas. In summer, the aroma of her sweet peas filled the air. The honeysuckles could be pinched and eaten while weeding. Clarice even won a few prizes at the garden fair.

There was nothing unusual or ornate about the garden or the home. It was immaculately clean and full of love. Everyone was welcome! The doors were never locked, for there was no need. The exterior of the house was finished in white stucco and trimmed with a four-foot dark green strip at the base. The roof was a contrasting lead-based dark green paint. In the 1950s, a thirty-foot television antenna was raised. It pointed east toward Lethbridge and was anchored onto the roof. The house had a television! One channel was all that was needed for complete family entertainment: Disney nature films, cartoons, and wrestling from the Maple Leaf Gardens. A curious copper wire stretched from the antenna into the ground. Floyd explained to the children and his grandchildren that it was for lightning storms that thundered over the town from the foothills.

To the south of the house, during the 1950s, Floyd constructed a free-standing garage. A line of three crab apple trees stretched between the house and the garage. The trees were white, with blossoms in the spring. Branches swung low and heavy with fruit by late summer. The fruit was small, delicately bite sized, and sour. The apples were enjoyable for the neighborhood children with a fancy for things tart. What the kids chose not to eat, the Hutterites from one of the nearby colonies were pleased to harvest for jam.[69] The garage never housed an automobile. Instead, it became a storehouse and was later renovated as a home for Grandmother Card. It was small and humble, clean, and even warm in the winter, allowing a grandmother to live close during her final years.

A line of ash trees and a small lawn separated the front of the house from the western edge of the property. These were stout little trees protecting the house from the persistent winds and the winter snow drifts. When the plow removed the snow from the street, it was piled on the west side of the road so high neither children nor drivers could see Town Square nor the trees. Children climbed up these piles of snow like young mountaineers.

Originally, an ornate wrought iron fence separated the house from the trees and the road. The heavy gates were always open to the new driveway. It seems someone kept backing into it, so the bent and snarled iron was finally removed. The front door to the house was generally “stuck” closed. It was warped by the snow, wind, and moisture, but it did not matter; it was used only by visitors anyway. Family and friends used the back door. Remodeling had moved the sunroom back door from the west and replaced it with a lilac bush outside. The door was relocated to the rear of the house, where an entrance and porch were added, protecting the entrance from the constant west wind. Five weather-beaten wooden steps at this entry had been painted green, but were so well worn, no one ever really noticed. There was a cast iron mud scraper sealed into the cement at the bottom of the steps. Here, the visitor, children, and parents scrapped the mud and snow from their boots before heading up onto a small porch leading to the entry.

Winter storms drifted snow right to the top of this porch. Snow was caught in a small white lap-wooden fence between the house and the garage, with drifts as high as six feet and extending as far east as the barn. The results produced short sled rides or a good snowball fight between parents and children. Children, left to their own imaginations, dug passages in drifts where there was a quiet stillness within these safe worlds of snow and ice. The porch provided a resting place for children in the summer months. They would just sit there and visit with their mom or play with the dog—Fido, Pal, or Sport—friends that lived underneath the steps.

The porch led into an entry room. It was a 4-x-6-foot cubicle for hanging winter parkas and storing overshoes. It insulated the main house from the inclement weather and mud that might be otherwise tracked through. In the entry, the children defrosted their ears and shook off snow before entering the blanketing warmth of home. It was at this little entry where the children first called for “mother.” There were never really any questions following the initial inquiry as to her presence. Children just wanted the comfort of knowing she was always there for them. If not, there was always a note of explanation on the kitchen table.

Once in the house, children huddled around the cook stove or sat on the oven door to warm up. Every morning started with Floyd as the first one out of bed, and he made the fire in the kitchen stove while singing, “You are my sunshine, my only sunshine.”[70] It was a sad country song about a man whose wife had left him. Floyd repeated the chorus over and over. Modern appliances replaced the wood and coal-burning kitchen stove with an electric one and central heating. Central heating shot hot air from the furnace downstairs to the upstairs kitchen vent. Clarice’s wide dress caught the heat blowing from the vents, so kids stood close, and she would cuddle them and laugh as they pushed and maneuvered for the warmest positions.

A barn was the second building on the property, southeast of the house. The haystack was immediately south of the barn. The pig pen was a muddy mess between the haystack and the wall of the barn. On the other side of the wall there was the chicken coop. At the north end of the barn were feeding and milking mangers for the cattle. The manure trough was in the middle of the barn. The oats, wheat, grain, and bailed hay were along the west side of the manger. The barn housed one or two cows, a pig, and the chickens. Each spring, Floyd brought home a box of little yellow chicks and placed them in the open oven to keep warm and adjust to home before they were sent to live in the chicken coop. Betsy was the family cow, a pet of sorts. She had one lone horn, but with it she could hook the gate or barn door and escape out, only to be recaptured and returned. At night, the manger was filled with hay, and in the cold winter the hay helped protect the animals. Manure rich in nitrogen was hauled from the barn to fertilize the garden. The cows were returned for milking each evening. The cows were bred to bear a calf each fall and were the winter meat.

The barn was all work and part play, depending upon age and the child’s position within the family. Ken and Lorin did the milking and heavy barn work. As they filled the milk buckets, they squirted the barn cat and any passing young ladies they might have been trying to impress or annoy. The raw milk was placed in milk bottles and capped. A day later, the cream had risen to the top, and young Don now had the milk delivery responsibilities. He pulled his red wagon full of milk bottles to the waiting neighbors. Disaster struck one day when Lorin came home from school to water the cows. They had broken into the grain bin and lay on the barn floor bloated. Floyd, Lorin, and the veterinarian righted the cows and tried running them to force the gas out, but to no avail. Something was expelled, and it covered Lorin from head to toe, but the cows died, and they were dragged off the property.[71] It was a significant loss to the family in terms of income and nourishment, but new cattle were acquired. The daily opportunities for tending to the livestock, milking, feeding, and watering the cows, were always a source of debate among Floyd’s sons. Debate persists to this day among eldest brothers as to who did most of the milking.[72]

As time passed, cows gave way to the milkman’s daily delivery and eventually the grocery store. The family maintained the animals as a means of sustaining their daily living. Floyd kept hay for the cow outside in a haystack and brought it inside the barn dry to feed the animals. The hay was purchased by weight from the neighboring Blood Tribe farmers. If it had been a dry year, the cattle would get beet tops from the Magrath farms. Generally, on Thanksgiving Day, Floyd shook his two oldest sons from their slumber and headed to Magrath to load their borrowed truck with beet tops.[73] They hauled them back to Cardston and unloaded them in stacks placed around the garden. The beet tops were frozen by the time the cows got them, but that didn’t seem to deter them at all. This Thanksgiving Day routine kept Kenneth and Lorin out of their mother’s hair while she, Arlene, and Marilyn prepared the feast. After the beets had been unloaded, the men cleaned up, and grandparents, relatives, and friends arrived, and Floyd carved the turkey.

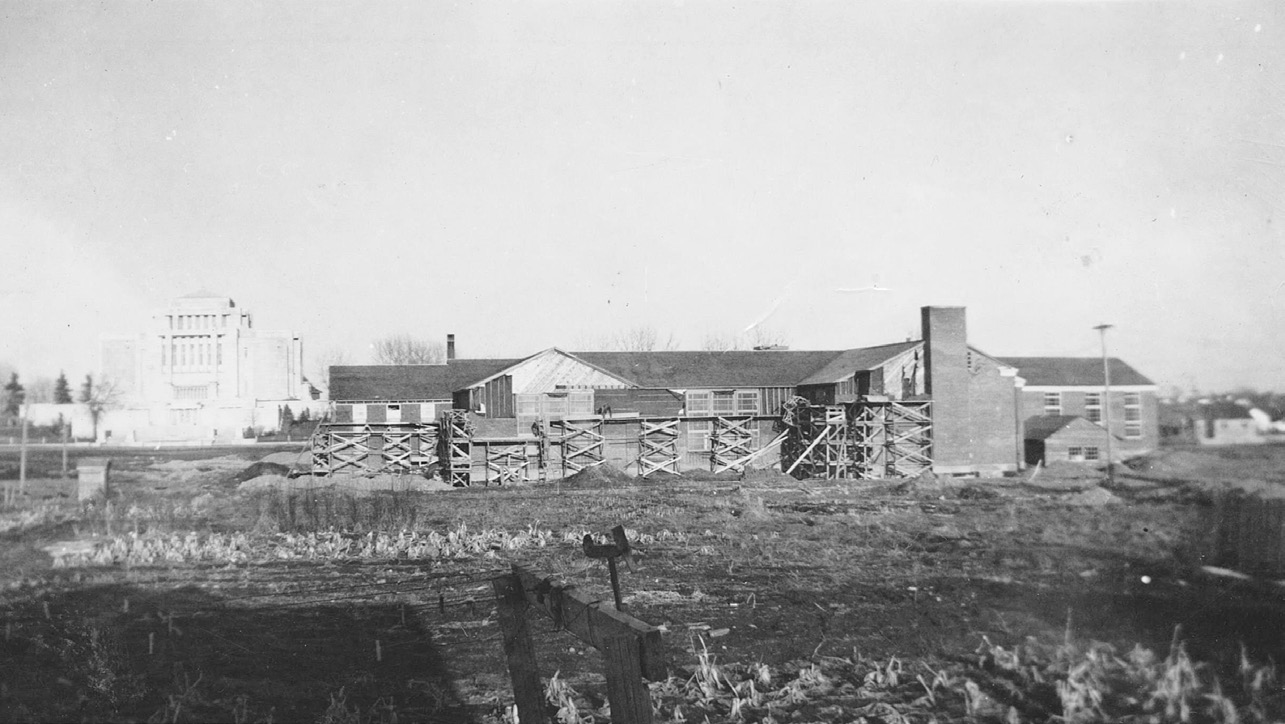

Alberta Stake Center under construction, 1953–54; view from Godfreys’ back porch; note the clothesline in the foreground and the outhouses left. Courtesy of Godfrey Family Files.

Alberta Stake Center under construction, 1953–54; view from Godfreys’ back porch; note the clothesline in the foreground and the outhouses left. Courtesy of Godfrey Family Files.

In 1954, their barn and garden land to the east of the house was donated for the building of the LDS Church Alberta Stake Center. The barn disappeared, and the garden was moved to a plot immediately north of the house. A wooden fence separated the Godfreys’ and their neighbors’ gardens. The old cat walking across wooden planks was good target practice for the young man with a rock in hand. When Kenneth’s aim proved accurate, his father instructed him that he would go and have a talk with Grandma Annie Gregson.

In addition to the eastern property, Floyd and Clarice donated a strip of land along the south edge for an east-west roadway access. The ragweeds, into which children once tunneled, also disappeared. The east garden and barn became part of the new church building with a large parking lot. Sunday services were in the new chapel. Basketball, scout activities, dances, and a small theater stage resulted in a continuous flow of activity, since the stake center building was always open. Even after school, neighborhood children gathered for basketball. There were no uniforms. Teams were chosen and games played: “shirts” against the “skins.”

The stake center’s construction was a welcomed sacrifice for the entire neighborhood. Families happily donated their land. Clarice sewed the curtains for the large stage, and he started his own store, Floyd’s Furniture, providing the carpet and the chairs. The days of barns and large lots in the town transformed into more home lots. It was a community and a neighborhood transformation. Everyone pitched in to help.

Cardston Alberta Temple. Photo by Matthias Süßen.

Cardston Alberta Temple. Photo by Matthias Süßen.

Cardston Alberta Temple

The most imposing structure in the neighborhood and in southern Alberta was and remains today the Cardston Alberta Temple of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. It was constructed and dedicated in 1923, when Floyd and Clarice were teenagers living in Magrath. Their families were not directly involved in the construction of the temple, but they did teach their children the significance of this spiritual structure. Over the front door it reads, “The House of the Lord.” The Cardston Temple sits on a small hill, just an echo away from the Godfreys’ back porch, and Floyd’s whistle would bounce off the granite walls as he called the children for supper. This edifice of religious worship centered around family life, community, heritage, cultural pride, and religious belief. Every week, Floyd and Clarice went to the temple, promising the children that when they were old enough they too could worship there. It produced a comforting spirit in the backyard. It was a symbol of profound history and cherished personal worship.

Cardston Town Square

The Charles Ora Card Town Square had family and town history. The land owned by Charles was donated and set aside as a recreation park for Cardston. The center of the town’s sports activities remains directly across the street, just west of the Godfrey home. It was originally surrounded by a wooden fence, then enclosed as a field with barbed wire. Today it is an open four-square block of recreational space. In the early years of the Godfrey family, it was simply a block reserved for baseball, tennis, and ice skating. If the neighborhood children were not in the gardens, running around the yards, or playing in the wilds of the ragweeds, they could be found across the street playing baseball. There was one baseball diamond at the southeast corner. Games were played both informally by neighborhood kids and competitively between church youth groups teams in surrounding towns. Behind home plate stood a larger-than-life, weather-beaten, gray-green grandstand. It was a shady place to watch the games. The front of the grandstand was covered with chicken wire to protect the fans who sat on the wooden benches. The whole structure was about fifty feet wide and sat immediately behind home plate. The teams sat on several 2-x-6-inch benches strung along both the first-base and third-base lines. In all likelihood, no more than a few hundred spectators could have squeezed onto the stand. It was uncomfortable and slivery, but better than a ground blanket on a hot summer day. Town workmen used the space underneath the grandstand for storage. The neighborhood children snuck into the darkness to smoke corn silk, thinking they were committing a great sin. The back doors were always locked tight, but the enterprising youngster was always able to find a loose board or crawl under the steps for entry. Miraculously, the stand never burned down. Today the field is beautifully developed with multiple ball diamonds and known as the Town Square.

The tennis courts were off right field to the north of the baseball diamond. There were three courts created with crushed red rock, and tattered nets. Whether the nets were abused or worn is unknown, probably both. They were surrounded by a twelve-foot-high fence that never seemed high enough. At night the children lay in bed and listened to the wind whistle through the courts like a song. Hearing the wind singing was an ever-present soothing sound; unless it blew the roof off the school’s shop building. Even that was okay, though, because the kids would not have to go to school when a classroom had no roof.

Hockey and ice skating were winter sports at the northwest corner of the square. There was a freshwater spring that kept this corner of the field moist and sticky. Walking across it in the summer, a child could lose a shoe or boot yanking their foot from the mud. It was a good place to catch tiny frogs. In the winter it froze, transforming itself into a children’s skating pond. Children sailed over the bumpy ice—mostly west to east as they unzipped their parkas, lifted them over their heads (like a sail), and skated to the east side of the ice. Once there, they’d drop their jackets, zip them up, fight the wind back to the west side, then sail back for another trip over the ice. The older boys took off their snow boots and put on their skates and practiced their hockey. They would lace two boots on the north end of the pond and two on the south and use them as their goal posts as they practiced for the NHL. Today, the bog has been drained and filled to make space for more baseball diamonds.

A five-foot-deep ditch once ran north to south along the west side of the park, attempting to drain the water, but more importantly, the high mud banks provided an imaginary world of childhood cowboy heroes: “Zorro,” “The Lone Ranger,” or “Lash LaRue.” The running water at the bottom of the ditch heightened the imagination and the danger in this visionary world of play. The ditch ran for half a mile before it emptied into Lee’s Creek.

This was the 1940s and 1950s neighborhood—the hub of the Godfrey family—the center of their earliest years in Cardston. Children ventured beyond the neighborhood, but only to hike Lee’s Creek, swim up the creek to Bob’s Hole or Slaughter Hole, go on a family picnic in Waterton and Glacier Parks, or visit extended family in Utah. The influence of people, places, and events within these few blocks was substantial. Within this neighborhood, children were protected, and teenagers were guided by mothers and fathers who taught high standards and expected discipline. Footprints were etched and molded from the seeds of this heritage, loving hands, time and experience, and were traced by the families who followed.

Notes

[1] Kyvig, Daily Life, 27, 53, 91. Also, Ernest J. Wrage and Barnet Baskerville, American Forum (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1960), 223.

[2] In the United States, the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads produced employment and transportation for thousands from Cache and Weber valley settlements. See Ricks and Cooley, The History of Cache Valley, 172–74, 182–85. The Union Pacific Railroad would eventually take over the Utah Central Railroad and the Utah & Northern Railroad. The Utah Central Railroad connected Ogden and Salt Lake. The Utah Northern (which is a separate railroad from the Utah & Northern Railroad) connected Ogden to Brigham City; Logan; Franklin, Idaho; Idaho Falls; Dillon, Montana; and the Montana mines. Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830–1900 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1958), 257–92. In southern Alberta, the Galt Lines connected with the Great Northern lines in Shelby and Great Falls, Montana. Small towns throughout southern Alberta were Lethbridge and Calgary. Se, R. F. P. Bowman, Railways in Southern Alberta (Lethbridge: Lethbridge Historical Society, 2002), 36, map.

[3] R. F. P. Bowman, Railways in Southern Alberta, 36.

[4] See Pierre Berton, The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881–1885 (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1971). Also Robert G. Athern, Union Pacific Country (New York: Rand McNally, 1971); Frederick M. Huchel, A History of Box Elder County (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society), 105–22.

[5] Godfrey and Card, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Canadian Years, 1886–1903, 14 October, 1886. See also, Claude Waitrowski, Railroads across North America: An Illustrated History (New York: Crestline, 2012), 146.

[6] Kyvig, Daily Life, 209.

[7] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, January 1977, 3–5. Also, 20 March 1982, 18.

[8] Marriage Certificate, license 5491, issued by Ira C. Fletcher, certificate in Godfrey Family Papers. A “sealing” in the LDS temple symbolizes the concept of an eternal marriage as opposed to this life only. Joseph Y. Card was the son of Charles Ora Card. James Andrew Hanson was son of Niels Hansen, one of Cardston’s original pioneers. William Henderson came to Canada in 1898. Keith Shaw, Chief Mountain Country, 332–33, 338–39. See the Journals of Joseph Young Card, 8 June 1927, L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

[9] Floyd Godfrey, “Great Events in My Life,” from “Life Stories,” file of undated handwritten stories from the life of Floyd Godfrey.

[10] Floyd and Clarice Godfrey, joint oral history, 8 May 1977.

[11] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, January 1977, 34–35.

[12] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, February 1977, 35. Fowler was Magrath’s doctor from 1925 to 1936; Nurse Polson is said to have brought “hundreds of babies into the world.” Magrath and District History Association, Irrigation Builders (Lethbridge: Southern Printing Company, 1974), 367, 506.

[13] Cardston News, 22 May 1930, 1.

[14] Magrath and District History Association, Irrigation Builders, 527. In Floyd Godfrey, “The Home Town Play,” from “Life Stories,” file of undated handwritten stories from the life of Floyd Godfrey, he indicates the director was “L. S.” Taylor, but this is undoubtedly Louisa Ann.

[15] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, March 1982.

[16] Floyd Godfrey, “The Home Town Play,” from “Life Stories,” file of undated handwritten stories from the life of Floyd Godfrey.

[17] Floyd Godfrey, “The Home Town Play,” in “Life Stories,” Godfrey Family Papers. Also, Floyd Godfrey, oral history, February 1977.

[18] An LDS Church “calling” is an invitation delivered by a church authority to assist in church labors. The church is supported by the voluntary, unpaid involvement in service and self-government. Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 248–49.

[19] Certificate of ordination, 5 August 1935, in Godfrey Family Papers. A Seventy was a general priesthood office in the Melchizedek Priesthood. In 1986 the practice of local Seventies was discontinued and set aside for General Authorities.

[20] Great Depression of Canada, http://

[21] Floyd Godfrey’s 1977 oral history indicates $.18 cents per hour. In his 1982 oral history, he indicated his salary was approximately $40 per month. To make these conflicting figures compute, Floyd’s work week would need to approach fifty-five hours per week, which during the Great Depression may have been likely.

[22] Magrath Town Council Minutes, 5 June 1929. Minutes reflect Floyd is working to purchase the land of Dora Coleman for his new home. Also, Lorin Godfrey, “A Touch of History,” July 2008.

[23] Magrath Town Council Minutes, 1 September 1935.

[24] Correspondence from Arlene Janet Godfrey Payne, 11 October 2011.

[25] Journal of Edward J. Wood, June 1931, in Melvin S. Tagg, “The Life of Edward James Wood” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, July 1959), 105–6.

[26] An LDS stake is a geographic designation of several wards or congregations. Fasting is the voluntary abstaining from food while praying for the Lord’s blessings. It was practiced in Biblical and Book of Mormon times. In this case, it was a public fast, seeking the Lord’s intervention in the drought. Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 500–502.

[27] Prayer circles are a part of LDS temple worship, the practice dating back to biblical times. In this case, the prayer circle was formed for a special priesthood group, the members of the Seventy Quorum of the Alberta Stake. Except for the temple endowment, the practice of special prayer circles outside of the temple endowment were discontinued 3 May 1978. Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 1121–22.

[28] Bertrand Richard Godfrey, oral history, February 1980.

[29] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 20 March 1982.

[30] Hutterites are a Christian people who adhere to traditional ways and live communally.

[31] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 20 March 1982. The Rockford Colony was formed not far from Magrath in 1918. See John A. Hostetler, Hutterite Society (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974), 364.

[32] Floyd Godfrey, “Cow and Beet Molasses,” in “Life Stories,” Godfrey Family Papers.

[33] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, January 1977, 34.

[34] Bertrand Richard Godfrey, oral history, February 1980. Bert Godfrey sold the Cardston Palace Theater to the Brewerton Brothers in 1927. The Brewertons would eventually purchase the Empress in Magrath and theaters throughout the small towns of southern Alberta. See Keith Shaw, Chief Mountain Country, 31–33.

[35]“Seen and Heard,” Cardston News, 22 March 1937, 1. A soda jerk was a person who operated the soda fountain in a store, serving flavored soda water and ice cream.

[36] Advertisements, Cardston News, 20 October 1936, 4, 8.

[37] Cardston News, November 1936, 1.

[38] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 1977.

[39] Shaw, Chief Mountain Country, 439–40. There are several conflicting accounts of what drew Floyd to this job. His 1977 oral history suggests Bert Godfrey had the license for the station and wanted Floyd to “come and run it.” At this writing, there was no evidence that this partnership ever existed or that Bert ever took an active part in the garage. Correspondence with Floyd’s children, in March 2014, suggests that Floyd was working closely with the Petersons, who in 1944 purchased the station. Also, correspondence from Douglas Godfrey to author, 13 March 2014.

[40]“Local and General,” Cardston News, 16 March 1937, 6.

[41] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 20 March 1982.

[42]“Local and General,” Cardston News, 11 May 1937, 1.

[43] Advertisement, Cardston News, 16 March, and 23 March, 1937, 3, 2.

[44] Advertisement, Cardston News, 25 January 1938, n. p. Also, correspondence from Douglas Godfrey to author, 13 March 2014.

[45]“Progressive Cardston” and “Local and General,” Cardston News, 16 August 1938, 1. See advertisement, Cardston News, 14 September 1937 and 26 April 1938. Also, “Texaco Quality: The Best,” Cardston News, 11 July 1939.

[46] Correspondence from Arlene Janet Godfrey Payne, 31 December 2010. Godfrey Family Papers.

[47]“The People History,” http://

[48] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, February, 1977, 2–3.

[49] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 20 March 1982.

[50] Melvin S. Tagg, The Life of Edward James Wood, Church Patriot (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University 1959), 8–15; also, Edward James Wood, https://

[51] Shaw, Chief Mountain Country, 520. Also, Chief Mountain Country, vol. 3, 127, indicated the sale to Wood was in 1943.

[52] V.A. Wood, The Alberta Temple: Centre and Symbol of Faith (Calgary: Detselig Enterprises Ltd., 1989), 18–19.

[53] Tagg, The Life of Edward James Wood, 103–25.

[54] Tagg, The Life of Edward James Wood, 103–5.

[55] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 20 March 1982.

[56]“Floyd Godfrey Manager ‘IMP,’” Cardston News, 3 February 1942, 1; Chief Mountain Country, vol. 3, 129. Also, Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 20 March 1982.

[57]“Good News,” Cardston News, February 1944, 1. Also advertisement, Cardston News, 16 March 1944, 3.

[58] Correspondence from Arlene Janet Godfrey Payne, 11 January 2011 and Lorin Card Godfrey, 29 March 2014; also, Kenneth Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 2013.

[59] Correspondence from Arlene Janet Godfrey Payne, 11 January 2011, and Lorin Card Godfrey, 29 March 2014; also, Kenneth Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 2013.

[60] Correspondence from Arlene Janet Godfrey Payne, 11 January 2011, and Lorin Card Godfrey, 29 March 2014.

[61] Correspondence from Arlene Janet Godfrey Payne, 11 January 2011, and Lorin Card Godfrey, 29 March 2014.

[62] Milo Ryan, History in Sound (Seattle; University of Washington Press, 1963). Speeches of these leaders were recorded by the British Broadcast Corporation, London and KIRO-CBS Radio, Seattle. These collections are today housed in the British War Museum, London, and the Milo Ryan Phonoarchive (National Archives, Washington, DC).

[63] Kyvig, Daily Life, 71–72.

[64] Letters from Lorin Godfrey and Arlene Godfrey Payne, 12 and 13 June 2014, Godfrey Family Papers.

[65] Letter from Arlene Godfrey Payne, 13 June 2011.

[66] Cardston News, 16 September 1941, 1. Also Shaw, Chief Mountain Country, 326–27; Floyd Godfrey, oral history, February 1982.

[67] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, February 1977.

[68] Donald was born 17 July 1944 and Robert 7 May 1961. Certificate in Godfrey Family Papers.

[69] The Hutterite colonies near Cardston were Raley, West Raley, Big Bend, and East Cardston. Hostetler, Hutterite Society, 362–65.

[70]“You Are My Sunshine,” by Jimmie Davie and Charles Mitchell, was first recorded in 1939.

[71] Lorin Godfrey, “The Barn,” 1 November 2012, Godfrey Family Papers; also, Kenneth Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 2013.

[72] Lorin Godfrey, “The Barn,” 1 November 2012, Godfrey Family Papers.

[73] Thanksgiving Day in Canada is a celebration of the harvest and occurs the second Monday in October.