Families Follow to Alberta

Donald G. Godfrey, "Families Follow to Alberta," in In Their Footsteps: Mormon Pioneers of Faith (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 173–188.

A Quiet, Loving Son

George Cyrus Card was the eldest son of Charles and Sarah Jane, born in Bountiful, Utah, on Monday, 26 January 1880, at 9:00 p.m. George took the name of his grandfather. It was a snowy winter evening, and the snowdrifts delayed the trains, making Charles late getting home from a church assignment at the Oxford Branch. He made it just in time to take care of some temple business and then be with his wife at George’s birth.[1] Within a few months, on Thursday, 6 May, George was given his name and a blessing by Henry W. Ballard. By the afternoon, Charles was back to work on the temple with Benjamin Ramsel.[2]

During the early 1880s, Cache Valley was expanding west as settlers formed new communities, thus causing business and industry to grow. “The city boomed with lawyers, doctors, and men of various processions, some not desirable,” wrote Joel E. Ricks.[3] People who were not Mormons saw the opportunities of the valley and that the population was growing. There were not adequate farmlands around the city, so communities around the valley sprang up. The Utah State Agricultural College was established in 1888 and was “a great prize for the region.”[4] Agriculture and its related industry were becoming well established. Government, education, and financial institutions were moving into the valley.[5]

George grew as most Cache Valley pioneer children did. He worked around the home with his mother, helped her in the gardens, helped on the farm, and attended school. However, unlike most other pioneer children, he received two patriarchal blessings instead of just one. The first was administered by John Smith on 10 September 1884, when George was only four years old. He was told that “the angel that was given to thee at thy birth shall watch over thee by day and night, direct thy course, give thee counsel in time of need and power over evil and unclean spirits.” The second blessing was administered by Henry L. Hinman on 19 August 1895, when George was fifteen years old. The persecution of his father, mother, and family no doubt frightened and unsettled him. The blessing reconfirmed the earlier promises and focused on spiritual admonitions. Be “respectful of thy parents and to the priesthood of God; . . . be prayerful; . . . be humble; . . . seek your wife in prayer. . . . I say unto thee strike against all weaknesses, even the weakness of the flesh that thy body may be strong.” George’s final blessing was given by his father as a newly ordained patriarch on 25 September 1902. George was twenty-two and living in Canada.[6]

George had lived in a peaceful, loving atmosphere—until the antipolygamy laws were passed in Congress and persecution began. He was an impressionable youngster. He was likely close by the house the day it was surrounded by the US marshals who arrested his father and led him away. No doubt he was scared for his life, as well as those of his father, mother, and little sister.

It was his mother’s influence that taught him the daily values of work and faith. However, the letters between him and his father during these years reflect lessons of life and love. Charles was always “papa,” Sarah Jane was always “mama,” and love was a constant. Charles cherished these while he was in exile, as George was the only one “old enough to bless me [and] that has the disposition to do so.” Charles always responded with love, teaching, and compliments. He told George his writing was of the quality that before long he could write for a newspaper and directed his son as to the proper use of a full signature in legal documents.[7] In a letter addressed to George from “Card on Lees Creek, N.W.T. Canada,” Charles encouraged and praised George in school progress, reminding him that his father and mother never had such formal opportunities.[8]

George’s writing would indeed improve and he would even try his hand at poetry. To his sister Pearl, at Christmas 1902, he wrote:

Our lives are albums written through

With good or ill, with false or true.

And as blessed angels turn

The prayers of our years

God grant they read the good with the smiles

And blot the ill with tears.[9]

Temptations and Trials of Youth

At seventeen years of age, George decided he had enough schooling. Charles was visiting Logan at the time and put him to work plowing the west field of the family farm. He purchased a horse and wagon for his son, helping him get started in a life on the farm. By 1898, George was engaged to Rose Elizabeth Plant, an aspiring teacher. She wanted to complete her schooling, and soon after the engagement they left Logan to complete her education.

Rose traveled almost three hundred miles north by train to Dillon, Montana, to attend the new Montana State Normal School. The school was established in 1893 to train teachers. Rose lived at the Hotel Metlen, where she also worked as a waitress to support herself and her goal of an education.[10] One of Rose’s small notebooks indicates that she took courses from a Professor Cooper in language, symbols of thought, grammar, literature, biology, science, religious truth, economic truth, and teaching. Her turn-of-the-century education came just before the Industrial Revolution and Gilded Age, giving speculative substance and debate to the subjects taught. Oil had just been discovered in Texas, and Rose studied how oil was affected by the weather. The science of weather on plants and people was critical for future farming. Her notes cover a spectrum of learning and continued faith in what she had been taught at home. She kept several recipes, among which are the following: gunsy gargle, which included a mixture of borax, potash, camphor gum, and a pint of brandy (likely Guernsey gargle used for throat relief); and black salve which was a paste applied to the skin for cancer and skin ailments. Her other recipes were probably tastier, such as those for Christmas pudding, carrot pudding, mint jelly, cocoa fudge, and peanut brittle. Rose loved to cook, and her grandchildren would later attest to the smell of date cookies whenever they entered her home.

While Rose was at school, George began dating Alice Louise Jones. They began a relationship and had a son, Edgar George Card, born on 2 March 1899, at which time he was given a name and a blessing by his grandfather Charles. George and Alice were married on 30 March 1899. Charles counseled George to hold onto the marriage with his new wife and son. Charles had learned the difficult life lesson and devastation of losing a wife and child through divorce. Nevertheless, the young couple eventually separated. Alice was given custody of their son, Edgar, and moved to Salt Lake City, where she married David Franklin Shelton.[11] These events were catalysts that drove George north to Canada and on an inward journey.

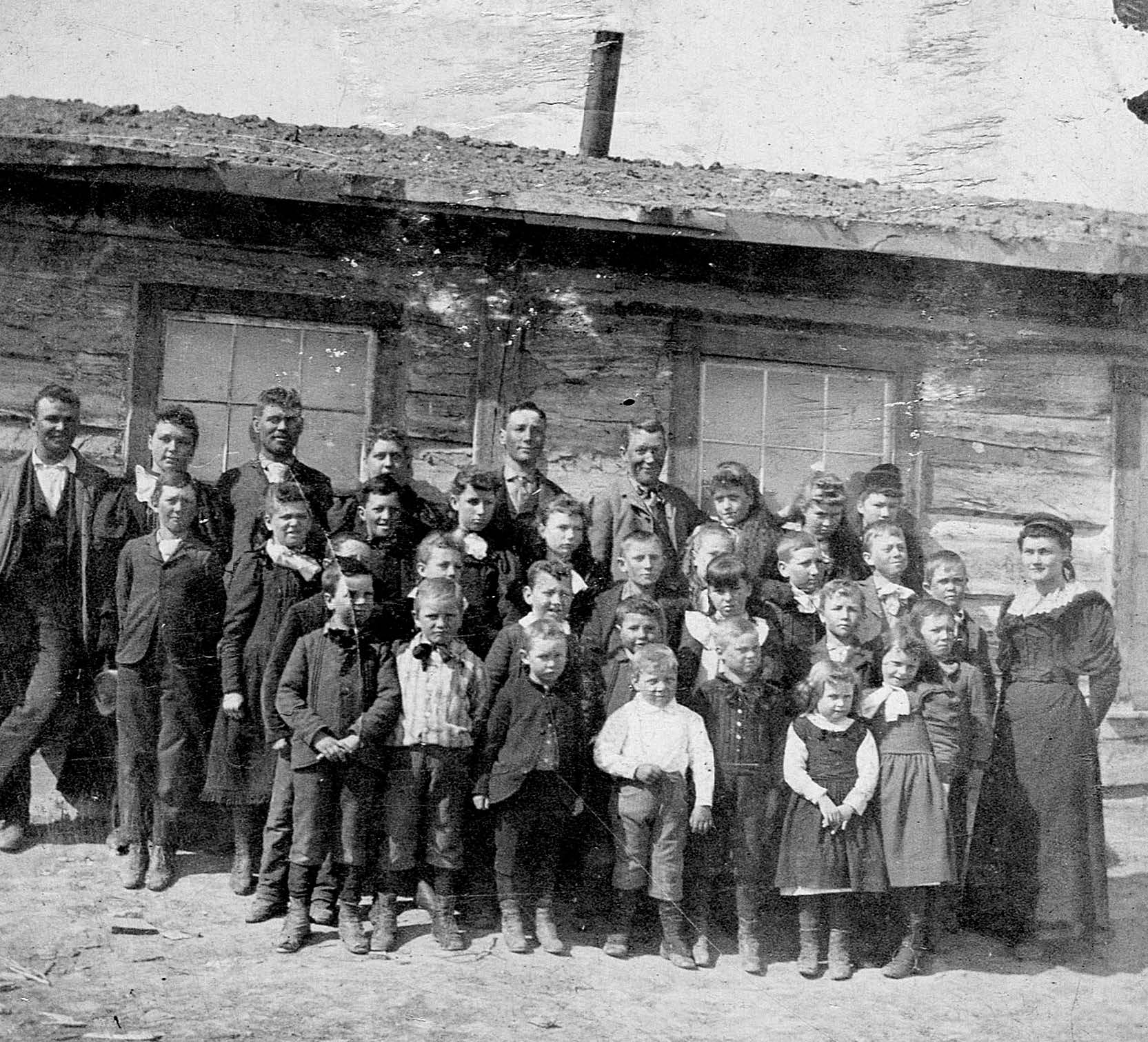

Rose was no doubt heartbroken and upset that George chose not to wait for her. But despite all this, she forged forward with her life. After acquiring her teacher certification, she accepted a position at the College Ward School.[12] College Ward was a small town at the southern end of Cache Valley, west of Millville, just five miles south of Logan. It had a one-room schoolhouse that doubled for church services. Rose taught grades one through eleven, and she loved learning. George and Rose were likely in contact, as she was still friends with his sister, Lavantia; but their relationship as a couple had obviously stalled.

University of Montana Normal School. Rose Elizabeth Plant Card attended, 1897–99. Courtesy of University of Montana Western.

University of Montana Normal School. Rose Elizabeth Plant Card attended, 1897–99. Courtesy of University of Montana Western.

Immediately after his divorce, George worked temporarily at a mining camp, but he soon decided it was not to his liking and moved to Canada to work with his father. He lived with Charles and Zina for two or three years in the log cabin that still stands in Cardston. He worked construction, shingled his father’s new brick home, and labored in an old meat market. “He was making a pretty good fist of the business, . . . a fair way to getting steady employment with the builders here.”[13] He sought other employment, reaching out beyond his father. The telephone was arriving in southern Alberta, and he helped build and repair the lines that were bringing electronic communication into the world.[14] Eventually, George acquired a job with the North West Irrigation Company. This would change his life. He was one of the workers who dug the canal from the St. Mary’s River to Magrath, carrying water from the mountain river to the fertile lands of the prairie farms. About five miles north of the border between the US and Canada, workers constructed a diversion dam on the St. Mary River, directing water toward the settlements of Kimball, Spring Coulee, and Magrath. Charles had plowed the first furrow of the canal in 1898.

George was a part of a $100,000 ($271,623,385) project “to make homes for and gain grown for a portion of the Kingdom of God.”[15] The canal was thirty feet wide at the top and twenty feet at the bottom, and when completed, it carried five feet of water. At Spring Coulee, a natural ravine carried the water along to Pothole Creek and Magrath. George drove his father’s horse team, plowing and dredging the canal. He was paid in cash and received 160 acres of farmland near Magrath. It was a quarter section and included mineral rights. He deeded a portion of the land to his father for use of the team and plow, but the land was later combined under George’s ownership. The land was comparatively inexpensive at the time, and cash was extremely rare. This was George’s southern Alberta foundation and would continue in the family for better than a century.

College Ward, Cache County, Utah, schoolhouse and class, 1899–1901. Teacher Rose Plant, standing with her class at far right. Courtesy of Marilyn Ockey-Pitcher.

College Ward, Cache County, Utah, schoolhouse and class, 1899–1901. Teacher Rose Plant, standing with her class at far right. Courtesy of Marilyn Ockey-Pitcher.

A Teacher in the Family

Rose Elizabeth Plant eventually married George in Canada. She was the youngest daughter of Henry Plant and Sarah Harris Plant, who lived in Cache Valley’s town of Richmond. She was born on 11 March 1879 and had five older sisters and three brothers. Her hair was wavy, and she had a small mole on her nose.

The Plant family had its roots in Cadeby, Leicester, England, where they owned a stocking factory. Henry, Sarah, and their first five children, along with Sarah’s sister, joined the Church and saved for years to make the journey to Salt Lake City. On 24 June 1868, they boarded the ship the Constitution for New York with some 457 other Church members. Forty-two days later, they arrived at New York.[16] As they disembarked, they met a man who claimed to be a representative of the Church sent to help them. In good faith, Henry gave the man all the money he had with him, holding back only sufficient to pay for the remainder of the travel. The family became a part of John Gillespie’s company that consisted of about five hundred people and fifty-four wagons. They traveled by train and wagon, arriving in Utah on 15 September. They had depleted their resources and went looking for the man to whom they had trusted their cash while in New York, who supposedly had taken it to make preparations for their arrival in Salt Lake. The man was nowhere to be found.[17]

It was difficult in a new land, but they established themselves in Richmond, Cache Valley County, north of Logan. They farmed, and during the times of persecution, their home was a safe haven for Church leaders, who hid in the attic when the marshals came around.

Rose was the youngest of nine. The Plants were a family who believed in hard work. Her father felt going to school was unnecessary for farm workers. However, her mother was a strong advocate of education. Rose’s mother and older sisters taught her numbers and the alphabet. Years later, she could still recite the alphabet backwards just as fast as she could forwards, without missing a letter. Rose had an express desire to learn. She worked hard and learned quickly. Her father died when she was just ten, and four years later, her mother passed away. This left Rose in the care of her older sisters. Her family was large, and all the children were expected to work. She completed her elementary and high school in Cache Valley and, in 1896, earned her common school diploma.[18] She worked in the summers, living with her sister in Blackfoot, Idaho, where she saved money so she could attend school in the winter. She was determined to be a schoolteacher, and it was at this time she attended the new Montana State Normal School in Dillon. She lived and worked at the Metlen Hotel just west across the street from the train station.[19] When she completed school, she moved back to Logan, where she took a position in the College Ward School, 1899–1901.

Metlen Hotel, Dillon, Montana, 1897, the building still stands. Rose Plant boarded and worked here while attending school. Photo by Donald G. Godfrey.

Metlen Hotel, Dillon, Montana, 1897, the building still stands. Rose Plant boarded and worked here while attending school. Photo by Donald G. Godfrey.

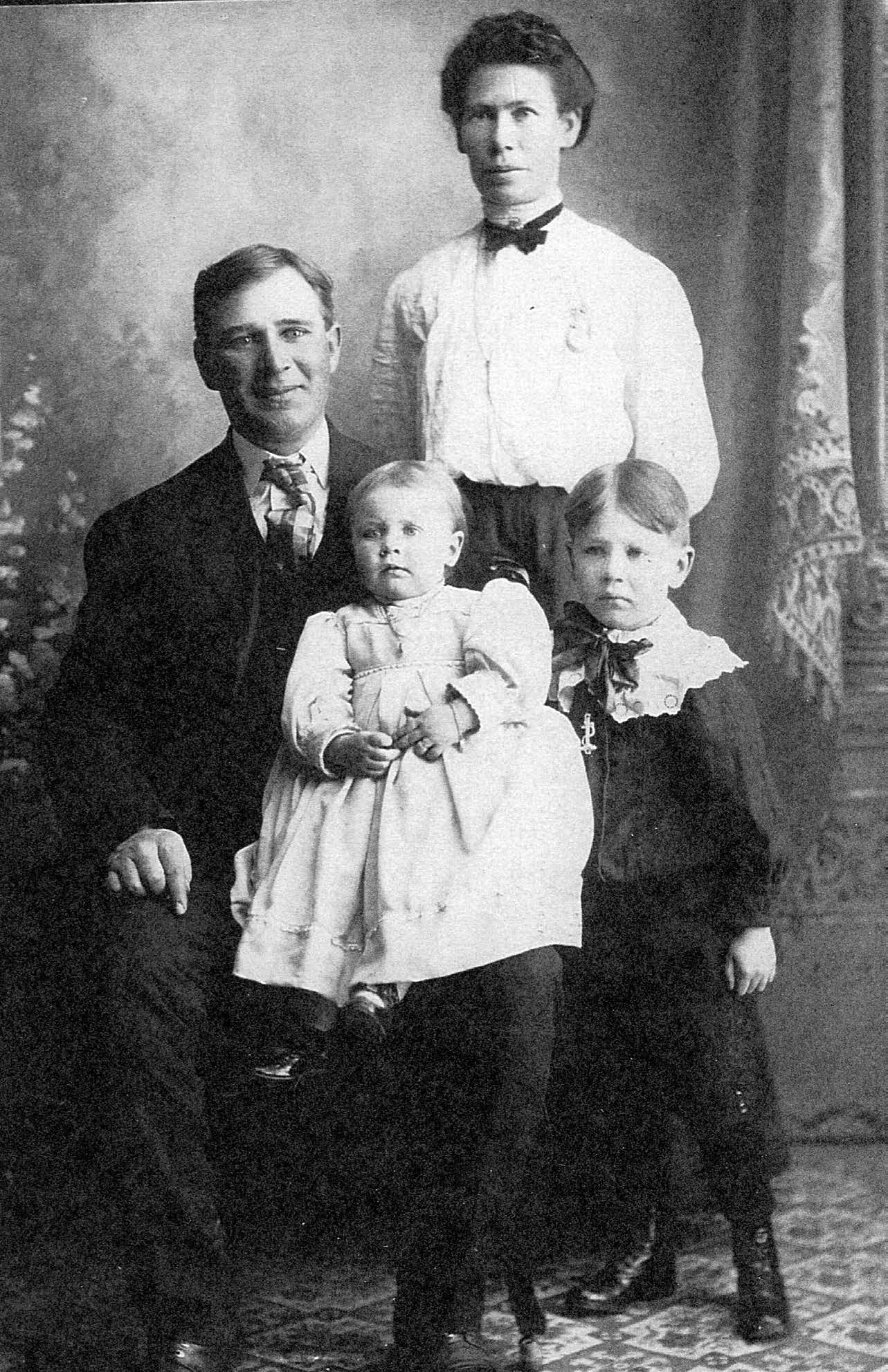

Little is written about George’s first marriage, but it is reasonable to assume that Rose must have been disappointed with George, and it must have taken more than a little persuasion before he finally convinced her to marry him and move with him to Canada.[20] Rose Elizabeth Plant and George Cyrus Card were married on 14 October 1902. The newlyweds lived with Charles and Zina in Canada until they had acquired the farmland just outside of Magrath. George hauled the logs to the farm using a team of horses and a wagon, and with those logs, he built a cabin. A few years later, George hired a Magrath carpenter named Melvin Godfrey to build a small two-room home. The home stands today, but with some additions. This was where George and Rose’s children were born: Leland Plant Card (1904–16); Clarice Card Godfrey (1907–80); Cyrus Henry (1909–87); Glen Charles Card (1911–90); and Melva Rose Card Witbeck (1925–2011).

Pioneering Farmers

George plowed the first furrow of his land and seeded it with the help of a friend, fellow canal worker Zebulon W. Jacobs. Jacobs owned the land just east of George’s plot, so they planted their crops together.[21] Wheat was their first crop. In these days, the seed was broadcast, meaning it was scattered across the furrows, cast by hand as the farmer walked the fields. It was then cultivated into the soil with a disk harrow pulled by horses. George worked with a shovel in his hands and gumboots on his feet. He worked hard to keep the weeds under control and the crops watered. The first crop was successful. George and Zebulon harvested the crops, hooked up a team of four horses to the wagon, and hauled the wheat to Lethbridge, where they sold it. This farming brought neighbors together in work and friendship. There were cows, chickens, and pigs on the farm. George corralled his pigs in the mud, and he was stern with any child or grandchild who approached the pen to gawk at the sow and her piglets.[22]

George was a loving father and a thoughtful, caring, and charitable friend. He and Rose eventually moved into the town of Magrath in 1918 so that their children would be closer to the schools. Many times, family and friends in need lived in their little home. Sometimes it was two entire families. If the husband was ill and the wife alone, George invited the wife and their children to live with them while their father recuperated in the hospital. When the husband died, George shared their sorrow and the family remained in his home with his support. Once, they took in a young girl whose father was abusive, and she lived with them for two years. When their son Cy’s first wife, Leta Cook, died, their children came to live with their grandparents.

There were also times when George could be too generous. He once tried to help a friend establish a business by loaning him money. When the friend indulged in too much alcohol, George was forced to take over the business. Then the Great Depression plunged him and the business deeply into debt.[23]

Community Affairs

George was easy to get along with and always willing to accept a service assignment from his ward and town leaders. He and Rose were both active supporters working for the Red Cross during World War II. George worked as a member of the “Old Folks Committee” of the town and church. He was always reaching out, organizing parties, and providing activities for the elderly. “He really liked to work with people and he was good with people,” especially those in need.[24] He was an active member and chair of the school board. In retirement, George enjoyed life working his gardens, visiting with friends and being with his grandchildren.[25] He was not one driven by the clock. “If he worried about anything, he did not show it.” He loved people, always lending a helping hand, and people loved him in return. In 1952, at George’s retirement from the farm, his eldest son, Cyrus, commented, “in our 22 years of farming together, we never had one serious disagreement; . . . he was honest . . . trustworthy” and never critical of anyone.[26]

George’s grandchildren described him as gentle and kindhearted. They all thought they were his favorites until they talked to one another and the secret was discovered: he cared for them all. One summer evening, Rose was out of town visiting their children, Glen and Helen, who lived in British Columbia. George’s granddaughter Arlene Godfrey had come to stay with him. She had gone to a movie with a friend when a fierce hailstorm struck. The wind took the power out, the show was cut short, huge trees were toppled, and gardens were left without a leaf blossom. Arlene walked to George’s home with a friend, but when she could not find him, she was scared. Too frightened to stay alone, she went to her friend’s home. Meanwhile, George was out looking for her. He found her the next morning after he had searched all night.[27]

George passed away on 4 September 1958, after an extended battle with Alzheimer’s disease.

Rose was a hard worker. On their Magrath farm, Rose raised a flock of chickens and turkeys that the family ate, and they sold the surplus of those that were not eaten. Only when a badger burrowed his way up through the dirt floor of the chicken coop did George get involved. The badger killed thirty-five chickens and stored them in his hole. The loss of that many chickens was significant for any pioneer farmer. Taking action to fight this, George flooded the hole, forcing the angry badger to the surface, at which point he shot it. There were also beehives on the farm to pollinate the crops and provide the family honey. It was bottled, stored, and used by the family, and the excess honey was sold.

George and Rose Card with children Clarice and Leland, circa 1912. Courtesy of Marilyn Ockey-Pitcher.

George and Rose Card with children Clarice and Leland, circa 1912. Courtesy of Marilyn Ockey-Pitcher.

George and Rose’s farm home had none of the conveniences of modern day. Oil lamps and candles furnished the only light until the 1950s. Coal stoves were the only heat for warmth and cooking. The townspeople would haul coal from the mines in Lethbridge, or they could dig a cheap, soft coal from the banks of Pothole Creek. Horses were the means of transportation and energy necessary to pull the plow and haul coal, lumber, and the harvest. They would pump water from a hand-dug well. Furthermore, multiple children slept in the same room and in the same bed.

There was also a form of refrigeration. People would cut large chunks of ice from Pothole Creek in the winter and preserve them in the summer with sawdust and gunnysacks. Fresh milk came straight from their cattle, and if the milk sat in the bucket or a bowl, by morning the cream would have risen to the top. George paid his grandchildren one penny per tail for each mouse or gopher they caught around the farm or the house. He worked for his father, installing the phone lines and helping in irrigation construction, but his own home had no phone or running water. The children walked to school in town even when they lived on the farm.

Rose and George were different in many ways. While George never worried, Rose worried about everything. She seemed to worry persistently, while George either did not notice or just did not say anything. She wanted things done right and according to schedule. She was perky and less than five feet tall. George was laid back and medium height. When she went to town or anywhere in public, she dressed formally, with her black hat sitting atop her head, a net draped over her eyes, and a black purse hanging on her arm. George was casual either in town or on the farm. Rose did her share of farm work, but with four little ones under her feet, there was a great deal to be done. She experienced the loss of her first son, Leland, when he mistook a bottle of poison in the cupboard for a bottle of wild berry juice and passed away on 22 June 1916. It was a devastating loss for George, Rose, and his younger sister, Clarice.[28]

Rose served in the Church, teaching in both the Primary and the Relief Society. For more than a half dozen years, she was a counselor to Mary Watson, who served as Primary president. In the community, she was the director of the Women’s Agriculture Fair competition. People from the town would bring their vegetables, flowers, and such to the fair to be judged. She and George loved their flower and vegetable garden. There were paths in the garden which allowed for grandchildren to pick bouquets for the table. Rose taught her grandchildren to make doll dresses from hollyhock blossoms and colored dye from the blossoms. Her home always smelled like date cookies whenever her grandchildren were visiting. She passed away on 6 May 1959, a little more than one year after George.

Rose and George had worked together on the farm. When they moved into town, they worked their huge garden together, harvesting and sharing with family, friends, and neighbors. They were supportive of one another in their service to others. However, Rose never let George forget his first marriage. She could not forget the hurt she felt, so there were differences between them, challenges to overcome, and stress in the marriage. However, they held it together, raising a successful family and providing a foundational heritage.

Notes

[1] Godfrey and Godfrey, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Utah Years: 1871–1886, 26 January 1880.

[2] After Charles’s first wife, Sallie, divorced him, Ramsel became her husband.

[3] Ricks and Cooley, The History of a Valley, 63.

[4] Peterson, A History of Cache County, 151.

[5] Peterson, A History of Cache County, 185.

[6] The first blessing by John Smith and the second by Henry L. Hinman are in Godfrey Family Papers. The third is mentioned in Hudson, Charles Ora Card, 151, but there is currently no transcription.

[7] Charles Ora Card to George Card, 3 January 1893, Godfrey Family Papers.

[8] Charles Ora Card to George Card, undated, Godfrey Family Papers.

[9] George Card to Pearl Card, 25 December 1902, MS 8735, reel 5, CHL.

[10] Clarice Card Godfrey, “Family Stories,” spiral notebook in Godfrey Family Papers.

[11] Clarice Card Godfrey, “Family Stories.” See also Godfrey and Card, “Editor’s Notes,” The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Canadian Years, 1886–1903, 474–75; and Maxine Smith, “Life Story of Edgar George Shelton,” Godfrey Family Papers, Maxine Smith was Edgar’s daughter.

[12] John A. Hansen, “The History of College and Young Wards, Cache County, Utah” (master’s thesis, Utah State University, 1968), 66. A listing of the early school teachers includes Rose Plant.

[13] Charles Ora Card to daughter Pearl Card, 11 June 1902, Godfrey Family Papers.

[14] Godfrey and Card, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Canadian Years, 1886–1903, 26 June 1899.

[15] Godfrey and Card, The Diaries of Charles Ora Card: The Canadian Years, 1886–1903, 26 August 1899. Underlining is C. O. Card’s.

[16] Conway B. Sonne, Ships, Saints and Mariners: A Maritime Encyclopedia of Mormon Migration, 1830–1890 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1987), 54–55.

[17] Clarice Card Godfrey, “Family Stories,” spiral notebook.

[18] Rose’s common school diploma states the following: “Rose Plant of Richmond Cache County, has satisfactorily completed the Common School Course of Study prescribed by the laws to be taught in the Public Schools of the State of Idaho. Logan, Utah 12 June 1896.” Her teacher was S. W. Hendricks, and superintendent of the schools was Samuel Oldham. Certificate in possession of Marilyn Rose Godfrey Ockey Pitcher.

[19] The Metlen Hotel still stands in Dillon, Montana.

[20]“Story of the Plant Family,” transcribed by Clarice Card Godfrey, Godfrey Family Papers. Arlene Godfrey Payne has a small notebook Rose used during her school years. Writing on the back of the photo of Rose Card indicates the class and the years. Notebook in possession of Marilyn Rose Godfrey Ockey Pitcher.

[21] Reminiscences of Cyrus H. Card, circa 1980. See also Clarice Card Godfrey, “Family Stories,” spiral notebook; and MDHA, Irrigation Builders, 482.

[22] Floyd and Clarice Godfrey, joint oral history interview, 8 May 1977, Godfrey Family Papers.

[23] Reminiscences of Cyrus Henry Card, circa 1980, 3, Godfrey Family Papers. Cyrus was the son of George and Rose. Nothing was written about the type of business venture it was.

[24] Clarice Card Godfrey transcription, Godfrey Family Papers.

[25] Reminiscence of Cyrus Card. See also unidentified newspaper obituary, “Southern Alberta Pioneer, George Cyrus Card, Magrath, Dies at 78 After Long Illness,” Magrath Museum and Godfrey Family Papers.

[26] “Reminiscences of Cyrus Henry Card,” circa 1980, 3, Godfrey Family Papers. See also unidentified newspaper obituary, “Southern Alberta Pioneer, George Cyrus Card, Magrath, Dies at 78 After Long Illness,” Magrath Museum and Godfrey Family Papers.

[27] Arlene Janet Godfrey Payne, “My Memories of George Cyrus Card and Rose Elizabeth Card: My Grandparents,” 3 March 1980, Godfrey Family Papers.

[28] Clarice Card Godfrey, oral history, April 1977. An unidentified family group sheet notes that the death of Leland was due to “heart failure following measles.” Both records in Godfrey Family Papers.