Into the Canadian West

Donald G. Godfrey, "Into the Canadian West," in In Their Footsteps: Mormon Pioneers of Faith (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 71–98.

In the 1800s, southern Alberta, Canada, was wide-open grassland crisscrossed by rivers, dotted with lakes, and covered with rolling foothills leading west to the Canadian Rocky Mountains. The First Nations people moved about following their food supply—the buffalo. By the time Charles Ora Card arrived in 1886, the land was owned mostly by the Galt Alberta Railway and Irrigation Company and the Blood Indian Reservation.[1] The company land was part of the coal mining rights established by Alexander Galt and his son Elliot. They lived in Lethbridge, just twenty miles northeast of what is now Magrath, Alberta. Charles Alexander Magrath worked for the Galts as their corporate officer in charge of land development and sales. He was instrumental in establishing the town that today bears his name. Later, he became the mayor of Lethbridge, the speaker of the Northwest Territorial Legislature, and a member of the Dominion (Canadian) Parliament. The tribal reserve was land set aside for the First Nations people, assuring its preservation and protecting it from the growing western immigrations.[2]

McIntyre Ranch

In 1887, the Mormons arrived and acquired land for settlement immediately south of the Blood Indian Reserve. In 1894, the Galts sold a large tract of land south of Magrath to Utah rancher William McIntyre.[3] Known as the McIntyre Ranch and operated by William and his son William Jr., it became a huge operation, running six thousand to nine thousand head of cattle. The ranch covered approximately “160,000 acres, with six sets of ranch and farming buildings” for housing family and the cowboys working the cattle and maintenance sheds. The McIntyres branded “2,000 calves per year and annually marketed about that same number.”[4] The herds had the freedom of the prairies. Cowboys in their saddles, with guns and rifles at their sides, protected them day and night from the roaming buffalo and the wolves. They all shared the open plains. The First Nations people were given forty to fifty head each year, which helped keep the peace. Stampeding buffalo created havoc and the several wolves that inhabited the area were hungry for easy prey, so cowboys were kept busy.

The McIntyre Ranch was centered at the edge of the western Canadian prairies in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains near the US border at Del Bonita. The land was largely unsettled until the Mormon pioneers arrived in Cardston, twenty miles west. The only city of any size was Lethbridge, twenty miles north of the ranch. Mormon settlers had come to Cardston seven years earlier, in 1887, under the leadership of Charles Ora Card, the first LDS pioneer in southern Alberta. They set their hopes on religious freedom, ranching, and farming opportunities.

Financing Irrigation

During the 1890s, southern Alberta was in the throes of an economic depression which dampened the spirit of bankable growth envisioned by the Galts. Future development required water, financing, and people. Irrigation was required to stimulate economic growth and diversification. The trio of the first irrigation builders were Galt, Magrath, and Card. Galt and Magrath recognized the feasibility of irrigation in southern Alberta as a means of expanding the potential of the land. Magrath, who was in charge of planning under Galt, was impressed with Card, who had irrigation experience from Cache Valley, Utah. Card extolled the southern Alberta potential of the rivers providing an abundance of water for both farming in the prairies and ranching in the foothills. Basically, the Galts provided the financing, Magrath provided the planning through his surveying and land development expertise, and Card provided the personnel to make it happen.

By 1891, Charles Ora Card and John W. Taylor (son of the LDS Church President John Taylor) had convinced Church authorities of the Canadian potential and, with Galt, they signed a contract for a purchase of 720,000 acres.[5] On this land the towns of Magrath, Stirling, Welling, Raymond, and other small settlements emerged. Settlers provided the labor for building a canal system in exchange for money and land. The Godfrey, Card, and Coleman families, along with many others from Utah and Wyoming, were part of this northward Mormon migration.

Town of Magrath

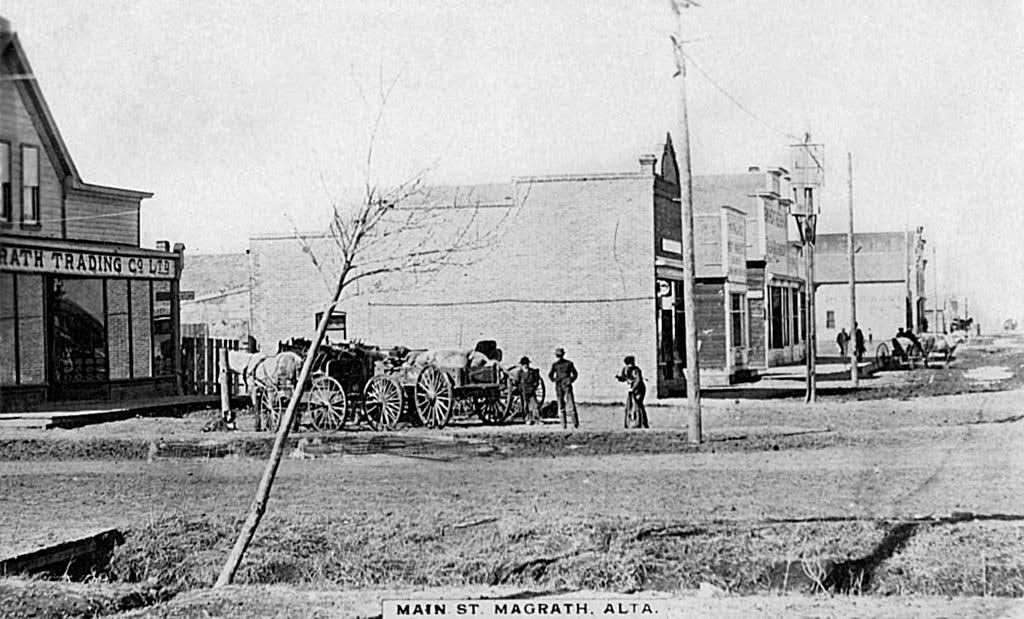

Downtown pioneer Magrath, Alberta. Courtesy of Glenbow Museum.

Downtown pioneer Magrath, Alberta. Courtesy of Glenbow Museum.

The first settlers arrived along Pothole Creek (Magrath) in 1899, but it was not until 1901 that the settlement had progressed into what could be called a village by the Northwest Territorial Legislature. It was named “Magrath” in honor of Charles Alexander Magrath. Within six years, on 24 July 1907, it was incorporated as a town. The first election created a mayor and council: Levi Harker (mayor), Andrew Hudson, Dr. Charles Sanders, Orson A. Woolsey, J. J. Head, J. B. Ririe, and Anthony Rasmussen (counselors). Two months after incorporation, the town council appointed the first town constable, Melvin Godfrey.[6] This was the “stroke of luck” of which Eva had spoken earlier. Melvin’s salary was eighty dollars ($1,941) a month.

Melvin’s work with the town gave his family a foundation. In addition to his role as marshal, he was also appointed secretary-treasurer of the town council, “to look after all of the affairs of the town business.” That meant he was the town’s “secretary, assessor, road master, water master, and trouble man in general,”[7] as well as the town foreman, pounds keeper, and bookkeeper. Shortly after his appointment, the council thought the marshal should have a phone in his home, so they installed one and they paid half the bill.[8] The council meetings were first held in the LDS Church tithing office, later in an assembly hall constructed by Hyrum Taylor (another son of Church President John Taylor), and then in 1910 officially at the first Magrath Town Hall. As constable, Melvin worked and served at the bidding of the councils through the mayoral terms of Levi Harker, James B. Ririe, Chris Jensen, and Ernest Bennion.

Lethbridge High Level Bridge, 1909. Courtesy of Galt Museum.

Lethbridge High Level Bridge, 1909. Courtesy of Galt Museum.

Melvin was an enthusiastic supporter of his town. As a member of the Magrath Board of Trade and the Agricultural Society, he helped organize community activities and supported improvements as the town expanded. The town was an important part of his life, pride, and service. He represented Magrath when the high-level Canadian Pacific Railway bridge, located in Lethbridge, was opened in 1909. He was with the first group to ride across the bridge. This massive steel structure over the Old Man River remains the largest railway structure in Canada even today. By 1914, Melvin was the city clerk.[9] He accompanied Mayor Bennion to Calgary, securing the first electric lights for Magrath.[10] The electrical system they created was later purchased by Calgary Power, which was then supplying efficient reliable energy and signing franchises with smaller towns throughout the province.[11]

Melvin remained a dedicated town servant throughout the years of Magrath’s expansion. He served during council debates regarding the evils of the pool hall, and on one occasion the council directed him to remove all tobacco products from the shelves of his own grocery store. He complied. When the town temporarily closed his theater for back taxes between 15 and 29 March 1919, he came after the council for the $372 ($5,162) loss incurred. His petition was denied.[12] He caught up on his taxes and moved forward positively, never again faltering on them. He served on the Sports Committee, the Board of Education, and the Board of Health Committees. The minutes of the town council meetings reflect that Melvin supported those who sought tax relief during difficult times.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, everyone in Magrath struggled financially and citizens were all behind in their taxes, including Melvin. He advised patience and lower taxes. “We have a nice little town as could be found in the province,” he commented. “The idea was to work cooperatively and pull together for the good of the community and we could pull out of this difficulty all right.”[13] His motto was one of service and commitment: “Magrath first, and everybody work to make Magrath the best place to live.”[14]

“Mean” Town Marshal

Melvin held a variety of legal responsibilities in the growing town of Magrath. In 1912, and again in 1917, he became a justice of the peace, a position he retained into the late 1940s.[15] In 1915, Melvin was appointed as a bailiff.[16] His responsibilities kept him in close contact with the town council and the citizens.

Being the town marshal had its dramatic moments. One such experience was when Melvin was the officer in charge of the search for John Taylor, son of Hyrum and Louisa Taylor. The boy went missing from the farm near Welling, six miles northeast of Magrath.[17] Because nothing was more important than family to these pioneers, Melvin easily recruited the entire town to volunteer to find the lost child, and they did.[18]

In the summers, Melvin organized and recruited firefighters to battle the prairie wildfires that occurred regularly just southeast of Magrath. One fire burned almost two square miles before it was extinguished. The prairie fires were annual events sparked by the lightning and thunderheads blowing across the plains. The fires usually burned themselves out or were stopped by a natural barrier or a creek. However, those threatening life or a farmer’s crops were fought by community volunteers working together.

Perhaps Melvin’s less dramatic—but certainly emotionally charged—experiences were just the regular passions that accompanied the job as a “cop [dealing] with drunks, kidnappers, and the such.”[19] As a judge, he later tried many such cases and some people went to jail, while others paid fines.[20]

Marshal Godfrey worked hard as a law officer and a father. He taught his children the meaning of work. Bert, Floyd, Mervin, and Joseph were recruited to recover stray cattle that had broken out of their corrals and wandered the public streets and into neighborhood gardens. Gardens in the early 1900s were important assets, unlike the modern-day ornamental hobby they are today. Building lots accommodated the need for large gardens. Magrath lots averaged at least an acre apiece and included space for the house, a barn, perhaps a pig pen and chicken coop, and gardens. The gardens were a means of year-round food. A stray cow in the summer garden meant less food on the winter table, so the Godfrey boys’ responsibility was herding the stray cattle into the town corral, an impound lot where the owner could retrieve the cattle after paying a fine. It cost fifty cents ($11) for the owner to free the cow from the pound, and the boys were paid twenty five cents ($5.50) per head. Thus, the streets of the town were kept free of cattle, gardens grew, and Melvin taught his boys to work.[21]

Within a few years, Melvin purchased a horse and saddle for herding the strays. The horse was a French coach buck with long legs named “Old Baldy,” but he was more than a buggy horse. The horse knew more about rounding up cattle than the kids. Occasionally, when chasing the cows, which naturally did not want to be in the pound because of its lack of food, the boys led the horse one direction, but Old Baldy turned another. Old Baldy was better at anticipating the movement of the cows than his riders, who with his quick turns were often launched into the air, landing them right in the irrigation ditch.[22] There was a rumor that the boys were earning a little extra cash by sometimes letting the cows out of their pens in the first place, but no charges were ever pressed or proven.

Magrath’s First Elementary School House. Courtesy of Magrath Museum.

Magrath’s First Elementary School House. Courtesy of Magrath Museum.

With a father as the town marshal, Melvin’s boys were exposed to unique experiences. When they were small, they accompanied Melvin into the bell tower of the old school to announce the evening curfew. The three-story school stood in the middle of town, just two blocks from main street, and it welcomed students from first grade through eleventh grade. To a child, it seemed like a monstrous brick building. In the dark of night, while fighting off the pigeons and sometimes catching them, Melvin and his children rang the nightly curfew. The curfew signified that people were to clear the streets at an appointed hour. For Melvin, ringing the bell was a responsibility as bailiff, but for his sons and daughter it was an adventure. They climbed the rickety stairs, making their way through the dark halls, going forbidden places other students—their friends—had never seen. They carefully made their way up three floors to the tower, edging closer to where the rope of the bell hung.[23] At the top they grabbed the rope and pulled. It rang at 10:00 p.m., calling young and old home for the night.

As the law officer and an officer of the courts, Melvin visited the school often to engage the youth.[24] But being marshal at times made him unpopular. One gentleman, who had three or four cows in the pound, “slipped over at night and slashed the tires of Melvin’s Model T Ford.”[25] The vandalism was vengeful and hurt Melvin because he loved his cars. He even collected license plates on the wall inside his garage.

Melvin’s nerves were not easily rattled. When a Royal Canadian Mounted Police officer kidnapped his own daughter, Melvin was called by the officer’s family to bring her back. The Mountie had married a Magrath girl, they had a child, and then they divorced. His wife raised their child—a girl—for the next two or three years after they had separated, but after that, the ex-husband wanted his little girl back. Melvin was simply a town marshal and was about to confront a Royal Canadian Mounted Police officer as he waited at the train station on the north end of town. While standing on the station platform, he was the target of a group of rebellious teens being daringly boisterous, who threw raw eggs at him and ran. Luckily for them, he was more concerned about the child and the Mountie than being covered with raw eggs. Melvin found the Mountie on the train with the little girl, and other than being egged, tragedy was averted.[26]

Melvin was especially unpopular with the rowdy teenagers of the town, who he called “a gang full of mischief.” Sometimes their consequences were jail or fines, and other times their consequences were natural. One evening, this gang of mischiefs was tipping over the outside biffies (toilets) when one of them fell into the hole up to his knees in raw sewage. The incident was reported to Melvin, who simply let the natural consequence play out.[27] Not only was it awkward to lift a companion from the sewer hole, but one had to wash off in the cold irrigation ditch before returning home wet and smelly. Melvin’s work with these mischief-makers was double-barreled. When teenagers were in trouble with the law, they knew Marshal Godfrey was a direct pipeline to their parents, and that too was a natural consequence because that meant the trouble multiplied when they returned home.

One summer day, Melvin confronted two boys for allegedly stealing a chicken. They wanted candy and the confectionary on main street was giving it away for the simple exchange of a chicken. The boys were carrying a fresh hen toward the store when Melvin approached. They told him the bird had come from their own chicken coop. They pleaded their innocence, but unfortunately at some point tried to run and hide, which weakened their case. They got off that time with only a disciplining action from their own father. However, the same two boys, along with a friend, were later caught trying to sneak into the evening movie theater without a ticket and “in walked old Man Godfrey the town cop.” This time Melvin took them all to jail and locked up the three frightened friends. The jail was a “cold cell with no lights whatever,” they whimpered. A few hours later he returned, jangling his keys to warn them of his approach. He released two at midnight and the third at 3:00 a.m. “He was really an old devil, that old man Godfrey.”[28] Melvin knew the boys’ families and made sure the youngsters would have to explain their actions and return home late to their parents. In this small community, such things seldom escaped the marshal’s knowledge. Melvin was easygoing on a first offense, but afterward he became increasingly stern.[29] Melvin was tall, a little over six feet. In his younger years he was slim with black hair and a mustache. His demeanor was imposing even to his own family. “A stern look was all he used to discipline” his children as well as the first warning to others who might be just testing the limits of the law. He never swore, but when he looked at his daughter Lottie, she knew “he meant get up and do the dishes.”[30]

Melvin’s most quietly compassionate service came as he cared for the aging and those who died, meaning that when anyone passed away, he got the first call. He was once summoned to the basement of a grain elevator where a man’s clothing caught in one of the fly wheels of the machine moving the grain. The wheel had quite literally whipped him around and around, beating the man to death. Melvin prepared the man’s body with the same care as others. He dressed it in clothing for the funeral and burial. This combined both civil and sacred religious service he performed as marshal and as a member of the high priests group of the Magrath First Ward.[31]

Magrath’s Baseball Trio

The history of Magrath and the story of the Godfrey family into the twentieth century would be incomplete without noting their love for baseball and competitive sports. “Pothole Against the World,” was the Magrath slogan in sports of every kind.[32] Pothole Creek was a stream running through the town and the town’s first name was Pothole. Melvin was on every Magrath celebration planning committee, and baseball was as much a part of the festivities as the parades, community picnics, and fireworks. Every celebration began early in the morning with a cannon fired from the back of a flatbed, which was heard all over town. Afterward, the band roamed the town streets performing familiar tunes and marching songs, waking everyone for the celebration and the parades, which started at 10:00 a.m. Sometimes the band gave a concert in the assembly hall. There were races and activities of all kinds for all ages—the rooster chase, the three-legged race, novelty pony races for the older children, and tug-of-war contests for the town masses. Softball at noon pitted the single women against the married women. Men’s baseball was the early evening highlight, followed by feasts and dancing at the pavilion.[33]

Southern Alberta intercommunity sports competition had its roots in those games. Each town fielded a team and competition was aggressive. They played against every settlement in the vicinity, creating the foundations of fierce but friendly contests. The tradition continues even now throughout southern Alberta.

Melvin and his two brothers, Josiah and Jeremiah (Jerry), were an integral part of early Magrath baseball. They were a mean trio, and baseball was one of their favorite pastimes. Melvin was the catcher, and “with his bulk, no backstop was required.”[34] Josiah was the pitcher, with Jerry at first base. Because these brothers were so close, they knew one another’s expressions, movements, and characteristics well. They also anticipated the opposition on the field, making it difficult for the opposing team to get anything past them. When Melvin got too old to play, he umpired. His youngest son, Douglas, remembered the “little ivory colored hand device that recorded the strikes and foul balls.”[35] Baseball continued as family lore and recreation through the decades. It was a favorite relaxation from the rigors of marshaling the town.

Silent Movies and the Empress

Melvin was an entrepreneur as well as a marshal and a baseball player. He was a vigorous business man with a lot of ideas, always alert for ways to improve the town and the family income.[36] His employment with the town provided stability but little promise for advancement or increased income. So while he continued with his responsibilities as Magrath’s law officer, he also branched out.[37] He constructed a three-section brick building downtown and rented out each unit: one for a barber shop, another for a Chinese restaurant, and the last for a grocery store, which he operated and called the Gusts Grocery. He paid his children one dollar a day ($18) for an 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. workday at Gusts.[38]

The Empress Theatre was the most significant of Melvin’s commercial entrepreneurial ventures. The motion picture business at that time was new and innovative. There were no movie theaters in Hollywood let alone Magrath in these days. It was after the turn of a new century, around 1910, that independent producers began producing films and, along with traveling performers, lecturers, actors, and actresses, moved in theatrical circuits with the early movies. Radio broadcast demonstrations were even a part of the attractions. Melvin exhibited the pioneering films as well as hosted the live performances. He pioneered film and its new culture in Magrath. Melvin ran the family theater business from 1915 to 1945, first in Magrath and then in Picture Butte, just north of Lethbridge, Alberta.[39] He was synonymous with Magrath’s first movie theater.

John H. Bennett actually owned the first Magrath film theater, called “The Electric.”[40] Bennett’s theater doubled as a roller-skating rink when it was not exhibiting films. He sold it to the partnership of George Coleman and Melvin Godfrey and they changed the name to “The Movie Theater.”[41] The theater was just off Main Street near Earl Tanner’s lumber yard, the Pioneer Lumber Company.[42] Unfortunately, the Movie Theater burned to the ground in 1915.[43] Although what started the fire remains unknown, it is a fact that the first films were highly combustible.[44]

After the Movie Theater fire, it was rumored that the Colemans would rebuild, but they were concerned and cautious. Melvin, however, was unafraid and marched forward. In 1915, he bought out the Colemans and sought permission from the town to build the Empress Theatre.[45] This theater was on Main Street, just south of the Town Hall, across the street from Magrath’s primary place of business, the Magrath Trading Company.

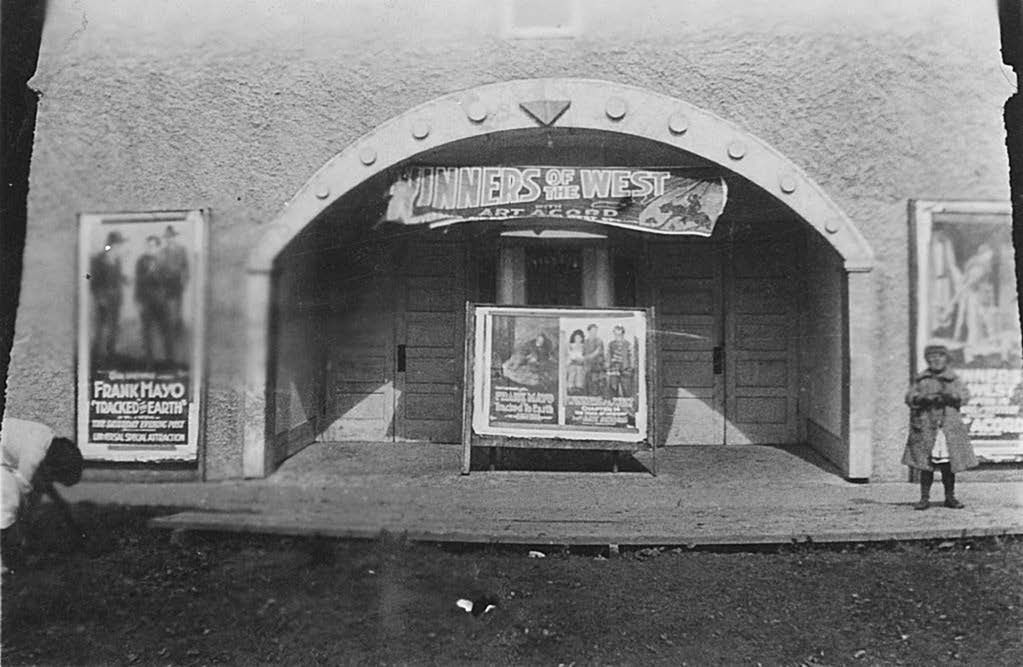

Empress Movie Theatre, 1926. Courtesy of Marilyn Ockey- Pitcher.

Empress Movie Theatre, 1926. Courtesy of Marilyn Ockey- Pitcher.

The Empress was a small, wood building perhaps fifty feet wide and one hundred feet long. It featured a projection booth and a stage. The main floor sloped slightly toward the front screen and seated 375 people on long, heavy, wooden benches. There were no individual seats. The audience sat on two sides of the auditorium in rows, extending fifteen feet long. The screen, twelve feet by twelve feet, was behind the stage on the front wall. The stage was about four feet high and stood below the screen. Live traveling vaudeville acts performed here. Once, a child named Orin Harker was injured when he fell off the stage while playfully jumping. He reached out to stabilize himself, grabbing the door to ease himself down, but his ring caught on the top of the door and cut off his finger as he fell.[46] Children didn’t jump around much on the stage afterward.

When needed, the theater was heated by a large, potbellied, coal-burning stove in one corner. This wasn’t a perfect system because people close to the stove were too warm, while those far away from it were too cold. In the corner opposite the stove sat the piano, with which a pianist would provide the sound accompaniment for the movie.

There was no concession stand in the theater, so the first audiences brought their own refreshments or purchased food from the Chinese restaurant across the street. Their favorite treats were bottles of orange soda, popcorn, candy, and peanuts. Theatergoers ate bushels of peanuts, eating the shells and dropping them on the floor. By the end of the show, the old wooden floor was littered with peanut husks. Also, because families had come by horse and wagon straight from the farms, the floor was covered with manure from the boots of the farmers. Furthermore, the roads were dirt or gravel, so in wet weather, audiences would also track mud into the Empress. At the end of the day, the mud, manure, and peanut shells were swept up, burned, and hauled out with the ashes.

In its day, the Empress rode the first wave of cinematic and theatrical pop culture. Families watched Charlie Chaplin, Mae West, Douglas Fairbanks, and D. W. Griffith, as well as the Tom Mix westerns. They also watched the Canadian-born Mary Pickford, one of the founders of United Artists.[47] Films they saw included Million Dollar Mystery, Birth of a Nation, Ben Hur, Girl of the Golden West, Poor Little Rich Girl, and Girl of the Game, which featured Pearl White.[48]

The earliest films were hand cranked and silent. At the Empress, this assignment went to Melvin’s sons. If one of these projectionists had invited a date up into the projection booth, then the film was cranked a little faster than it should have been. There was no sound to these movies other than that produced by a live pianist. Vera Babcock, Wanda Gibb-Coleman, Zelpha Harris-Dow, “the two Ririe Sisters,” and Lyal Fletcher all played piano accompaniment for the Empress.[49] These local musicians never needed sheet music. During a romantic scene, they played tender love songs and during the battles they played up-tempo marching music, which fit right into the theme of the film.[50]

In 1927, the music of Al Jolson’s Jazz Singer delivered the first sound-on-film to viewers. Technology and the industry were progressing rapidly.[51] The Academy Awards gave their first Oscar to a movie called Wings, starring Buddy Rodgers, Richard Arlene, and Gary Cooper. Melvin advertised this film with a World War I model biplane hanging outside of the theater. It was made of balsa wood by young Rulon Bingham, and it had a two- to three-foot wingspan to attract attention to the upcoming feature. Years after the show, Eva found the plane and returned it to Rulon.[52]

Melvin used all kinds of activities to promote the movies. Posters and banners in front of the theater pitched both current as well as coming attractions. If the posters were not required to be returned to the distributor, they became wallpaper for his grandchildren. Occasionally, he advertised in the Magrath Store News, and other times, on the evening of the movie, the whole town could hear his electric generator start up and see the beam of the arc light circling around in the sky.[53]

An evening of entertainment at the Empress consisted of a newsreel; a reel of comedy, cartoons, or vaudeville; a serial film; and, finally, the feature film. Movie serials were popular and sometimes continued for fifteen weeks. The last act of these short films always left the hero or heroine in some precarious cliffhanging situation, resolved miraculously in the next week’s episode. All told, the evening lasted two hours.

Not all cliffhangers were due to film creations. If the film broke, there was a delay, and the evening lasted for a bit longer. Electricity ushered in significant change; however, in rural theaters, electrical power came not from the urban street lines, but rather from a gasoline-driven electric generator. If the generator faded out in the middle of the movie, as it often did at the Empress, it sent Melvin, his boys, and all the males in the audience outside to grab the engine handle and hand-crank the heavy flywheel, thus restarting the engine. Once restarted, they returned to enjoy the end of the show.[54]

Melvin and the Empress Theatre were keeping up with changing technology and multitasking. When the generator was not being used for powering a projector, a conveyor belt converted it into a machine for chopping farmers’ grain. Then, in the evening, the belt was removed and the whole town again heard the series of explosions as the machine started up for theatergoers. When it did, “the light burst forth on a pole above the theater. It was time to go to the show.”[55] Melvin guided the bright beam of light from the projector’s carbon arc up and down the street, alerting the town that the movie was about to begin. He estimated the crowd size for an evening’s entertainment by climbing to the roof of the theater and scanning around to see how many wagons or cars were heading for town. At times, people lined up for three hundred yards waiting to get their tickets. Depending on the movie or performance, tickets sold between ten cents ($1.11) for children and twenty-five cents ($1.66) for adults.

During the Great Depression when money was scarce, tickets were bartered for some potatoes, eggs, or produce to feed the family. For the price of three potatoes, families were admitted to the movie. At one point, Melvin offered a prize for the best potatoes. This promotion sent children scouring their parents’ root cellars searching for their best ones. Eva and her daughter Lottie worked the ticket booth and during the Depression, and while they did, there were piles of potatoes in the corner. Later, the egg shows produced so many eggs, it was more than the family could eat.

Following a full workday at home, Eva went to the theater every night without complaint.[56] One evening, she found a good deal of money on the floor—375 dollars, or what is now worth a little more than 4,000 dollars. She put a slide up on the screen for a while, but no one claimed it. She kept advertising and finally someone came, properly identified the amount, and she returned it. He gave her a five-dollar ($56) reward.[57]

The Godfrey boys—Bert, Floyd, and later Joseph—were the projectionists, licensed by the Province of Alberta. The tiny projection room was at the back of the theater, up the ladder five steps to the second floor, and through a narrow door. This dark, mysterious little room was off limits to most. Floyd and Joseph were the primary projectionists, since Bert, the oldest, had married and was out on his own. Douglas, the youngest, was always sent to the Chinese restaurant for sodas. But the brothers all crowded in together, often making so much noise that Melvin had to scold them.

The first projectors used a carbon lamp for the light. These lamps were white-hot and dangerous. The projection room in the Empress was unfurnished. Opposite the projector was a bench for handling and rewinding the film. At first, when the theater had only the one projector, the audience waited while each finished reel was unloaded and the next film reel was loaded and restarted. There was a small window where the projectionist watched the screen and looked down at the audience. Floyd recalled, “I had to stop the show every 1000 feet of film and change the reels I had to be fast or the crowd became uneasy and started to shout and applaud.”[58] It was not long before the Empress added a second projector, which required Melvin to cut a hole in the wall for the second and another to the outside through which he shone the light into the street, thus gathering a crowd. The Empress exhibited films, but the enterprising Melvin rented the theater for vaudeville events, which featured speakers, traveling stage entertainers, and demonstrations. Films were brokered through the Motion Picture Exhibitors Association out of Calgary. Melvin, accompanied by two of his sons, Floyd and Joseph, attended the National Committee meetings in Calgary to book upcoming events.[59]

The first live entertainers at the Empress Theatre were varied. There was a phrenologist who placed his hands on Douglas’s head, feeling for bumps and claiming that would predict his future. Though not technically an entertainer, a doctor from another part of the province gave lectures on sex to the young people in the eighth through eleventh grades. One circuit entertainer introduced the newest in radio technology at the Empress. Another demonstrated the building of a crystal radio set, “so simple even a youngster could listen to the radio.” Even sounds of static excited the audience.

Radio was a novelty. There were probably no more than two receivers in Magrath, but a demonstrator from Calgary gladly set up his radio antenna outside the Empress, advertising for three or four weeks to draw a crowd. On the evening of the event, the radio set was carefully placed in front of the audience on a platform so everyone could see. The loudspeaker was likely akin to the RCA Radiola horn, popular in the day. The radio master searched the air for a station. The radio squealed and squawked and nothing materialized. Just once, he caught a station from San Francisco, just over 1,300 miles away. The audience cheered so loud at the sound that “no one could hear even if the radio had been on loud.” The evening ended, and with the radio and antenna disassembled, the audience went home content with the miracle of listening to a voice from San Francisco on this new “thing called the radio.”[60]

The Empress participated in a historic radio demonstration on 2 July 1921. It was a US national radio broadcast of the infamous Jack Dempsey–George Carpentier boxing match. Producers of the event promoted and linked the broadcast to radio stations and theaters across the United States and Canada. They generated significant profits, filling theater seats and launching the newest medium of radio. It resulted in the largest mass radio audience at that point in history.[61] The Empress brought this radio demonstration to Magrath with record crowds attending.[62]

During these kinds of demonstrations and performances, hawkers walked up and down the aisles carrying a tray attached to a strap hung around their neck, selling candy. “Every box contained a valuable prize, such as watches, rings . . . all for only 25 cents. Usually, the prize was a metal tin frog clicker.”[63] These profits went to the event organizers.

The Empress existed on the exhibition of films, vaudeville shows, magicians, actors, jugglers, and dancers. This was a family business, as Eva proudly declared, “We ran it without hiring.”[64] At the end of the movie or any event, the boys cleaned the floors. They pushed the long, wooden benches toward the front of the theater and swept the peanut shells toward the rear. Afterward, it was family time, and back at home around the kitchen table they tallied the income from the tickets while dining on oyster soup. One night after the show, Douglas slipped a fake pearl into the can of soup and made a “big production out of finding a real pearl in his supper.”[65] The family laughed and went right on eating.

In 1935, the middle of the Great Depression, Melvin branched out and opened a second theater in Picture Butte, Alberta. Picture Butte was a small town seventeen miles north of Lethbridge. Picture Butte had begun growing in 1923 with the construction of the Lethbridge Northern Irrigation System and the Canadian Pacific Rail Line passing through. Two years later, the town had been chosen as the site for the Canadian Sugar Factory. Thus, Melvin reasoned that the community had potential, and more motivation was the fact that his older brother Jeremiah lived there. So they moved to Picture Butte and started working at the theater. The new Picture Butte theater was managed by Joseph, who had segued into the position of projectionist at the Empress after his brother Floyd married and moved to Cardston in 1937. Joseph was the only son to continue his father’s film legacy.

The Picture Butte operation was called Melody Theatre. It offered a small room on the south side of the building that served as an office or living quarters for Melvin and Joseph while both Magrath and Picture Butte theaters were operating. It was Joseph’s first home when he married and took over the business.[66] There were two beds, a chesterfield sofa, a kitchenette table, and a few chairs. Visiting grandchildren stayed in this room with their grandfather and uncle.[67] On opening night, Melvin took free tickets to Jeremiah’s family. His nieces and nephews were mesmerized and happy that they got to see a free movie. If they were old enough, they helped with cleaning and taking tickets.

The Melody Theatre was constructed with a small concession stand selling popcorn and candy to the audience. It was a new theatrical profit center. Saloon-like swinging doors separated the concession area from the theater auditorium. In the auditorium, people took their popcorn and sat on either side of two aisles, separating the audience into thirds. At the end of the movie, they exited two doors toward the front and on both sides of the building. At this point, World War II was coming to an end, and the motion picture industry was growing with the rest of the nation’s economy.

Melvin kept his boys busy with work, who supported themselves with the little they earned while their father encouraged them as they grew. Working with their father and their mother at the theater and at home was just a part of growing up and life training.

Eva’s Household Routines and Heartache

Life in these early years of the twentieth century offered little leisure time. It came with challenge and tragedy. Eva worked at Melvin’s side in the theater and held down the home as his responsibilities grew in town and business. Their fifth son, Joseph, was born on 29 February 1911. Their sixth son, Norris, was born on 9 March 1913, just two years later. One day, Eva and Melvin had gone to work at the movie theater and left fifteen-year-old Bert in charge when Norris became ill. The six-month-old baby was choking, and they were called home along with the doctor. Baby Norris’s lungs had filled with fluid and he passed away. People poured into the Godfrey home to pay their respects. “Horses and buggies were tied up in front of our home and across the street.”[68] As Eva wrote of this tragedy years later, her last lines reflected her heart and her attitude: “I am thankful for my lovely children that never caused me to worry over them.”[69] As she aged, she retained her “sweet, kind and gentle soul . . . she dealt with her children without anger, only kindness and love.”[70]

Eva maintained all types of homes: tents, dugouts, log cabins, wooden shacks, and finally, a beautiful brick home on Magrath’s main street. Her earliest homes lacked modern conveniences such as electricity, running water, refrigerators, or indoor bathrooms. Instead, they hauled water in buckets one at a time from an outside spring or a well, and they collected soft rain water in barrels at the eaves of the house. Eva liked the soft water to wash her hair. The well water was outside the house, about ten feet deep and away from the outhouse.[71] The outhouse was the bathroom, simply built over a hole in the ground with two holes in the bench and an old Eaton’s catalog as the only toilet paper.[72] There may have been a chamber pot under the bed if it were winter and too cold to run outside. However, a boy’s quick outside run assured there was little constipation within the children.

Their first Magrath home had no insulation. The children slept three to a bed, and in winter, they huddled deep under many covers. In the morning, the water reservoir in the side of the stove and the bucket in the house were frozen.[73] A coal-burning stove was their only heat, meaning that most of the house was bitterly cold on winter nights. The children undressed and dressed in the kitchen, sat on the oven doors for warmth, and then ran for the quilt covers of their beds.

The Saturday-evening bath was an interesting ritual requiring significant preparation. Children bathed once a week in a large, round wash tub. They hauled water from the well or melted snow. In the winter, the parents sent the boys out to the yard for a “tub full of snow,” which they put on the stove to melt. As snow levels decreased, they went back out to “roll up a good size snowball,” about two feet in diameter, and it was added to the tub. As it filled and heated, Eva would skim the leaves and grass from atop of the water. The youngest bathed first, then the rest, all using the same water, perhaps “freshened” with warmer water as each took their turn. The older brothers always protested at being last, claiming the brother just before them had peed in the tub, and that “this didn’t freshen it up much.”[74]

In the summer mornings, thousands of flies covered the ceilings in the house. It was an astonishing sight. Melvin got the kitchen broom and swept them off, shaking the broom into the burning stove. The boys helped, using dish towels and whirling them around their heads to “herd-and-drive” the flies out the screen door. Just three or four such fly drives would clear most of the house.[75]

Monday was wash day. Laundry water too was heated on the stove and then poured into the hand-cranked washing machine. Clothes were then rolled through a wringer to remove excess water, after which they were hung outside on the clothesline for drying. In the winter, long underwear froze instantly and looked like ghosts swinging in the wind. Mysteriously, when brought back into the house, they were dry. The family would then iron the laundry in the kitchen using a heavy black iron, heated and reheated on top of the cook stove as the full day’s work progressed.

Eva was a great cook. The family all ate together around a table in the kitchen. Every meal was preceded with a prayer blessing the food. Breakfast was oatmeal—“mush,” as it was called—pancakes, eggs, ham, and buttered toast. Dinner, the noon meal, included fresh summer vegetables grown in the garden or stored in the basement from summer harvest. Eva canned the vegetables, dried the corn, bottled the fruits, and churned her own butter from the cream from the milk cows. Also, the smell of homemade bread filled the house and brought everyone together. Finally, the evening meal was supper.[76] Melvin’s favorite dish for this meal was mutton stew. And every Saturday night after the movies, supper was oyster soup. Desserts included freshly baked apples, a wild berry or rhubarb pie, and raspberries with cream or homemade ice cream.

Eva was a dedicated service worker for the LDS Church in addition to her duties to her family and to the Empress. She worked in the children’s Primary organization and the women’s Relief Society for many years.[77] While she was in the Primary Presidency, she tried to teach her boys to stay out of the pool hall, telling them that “you learn no good there.” She also instructed her boys to stay clear of face cards, as they were “the work of the devil.”[78] In the Relief Society, she was a dedicated class instructor and visiting teacher. She and Henrietta Crookston traveled by horse and buggy to complete their visiting teaching. Some women on the route were ten miles out of town and it took most of the day fulfilling their monthly visits. Visits focused on performing service to the aging, giving individual attention to those they visited, and lightening spirits along the way. Eva was in the Relief Society presidency for eight years, and she always loved the gospel and the women she served.

Eva was an active member of the Magrath women’s organizations that were not a part of the LDS Church. In town, she was among the organizers of “the club.” This was a group of ladies who regularly gathered in one another’s homes to visit, sew, do handwork, do needlework, and just enjoy one another’s company. After these visits, they had a “lovely lunch.” There were almost twenty women in Eva’s Magrath circle.[79]

The life of a pioneer meant work at every turn, and the Godfreys did this as they moved from North Ogden, Utah, into Magrath, Alberta. As they traveled, they witnessed a few new conveniences appearing much later in their lives such as automobiles, washing machines, and indoor plumbing and water. Melvin drove one of the first cars in Magrath and enjoyed trips to Waterton Park and Lethbridge. For the most part, they were really just an average family, like everyone else in Magrath, establishing themselves and their faith in a new community, in a new land.

Notes

[1] Lowry Nelson, The Mormon Village: A Pattern and Technique of Land Settlement (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1952), 216, figure 16.

[2] Alex Johnson and Andy A. den Otter, Lethbridge: A Centennial History. City of Lethbridge and the Fort Whoop-up Country Chapter, Historical Society of Alberta, 1985. See also Howard Palmer, “Polygamy and Progress: The Reaction to the Mormons in Canada, 1887–1923,” in Brigham Y. Card et al., The Mormon Presence in Canada (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1990), 117–19. And Nelson, The Mormon Village, 239–48.

[3] William H. McIntyre Jr., “A Brief History of the McIntyre Ranch” (Lethbridge, 1947). A local history published by the ranch. See also Magrath and District History Association (hereafter cited as MDHA), Irrigation Builders (Lethbridge: Southern Printing, 1974), 41–44.

[4] McIntyre, “A Brief History,” 31.

[5] MDHA, Irrigation Builders, 41–45; see also Cary Harker and Kathy Bly, Power of a Dream (Magrath: Keyline Communications, 1999), 10–15; and Howard Palmer, “Canada, LDS Pioneer Settlements In,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 1:252–54.

[6] Minutes of the Town Council Meetings of Magrath, 16 September 1906, 22, Magrath Historical Museum, Magrath, Alberta, Canada.

[7] “Melvin Godfrey,” 2. Autobiographical two-page document written in first person, Godfrey Family Papers. See also Magrath Historical Museum Family Papers. “Melvin Godfrey,” in MDHA, Irrigation Builders, 459.

[8] Minutes of the Town Council Meetings of Magrath, 2 December 1907, 37, Magrath Historical Museum.

[9]“Province of Alberta,” The Canadian Almanac and Miscellaneous Directory (Toronto: Copp, Clark, 1913): 439.

[10] “Magrath Town Council Minutes,” 26 January 1917.

[11] Max Foran, Calgary Canada’s Frontier Metropolis: An Illustrated History (Windsor, Ontario: Windsor Publications, 1982), 76.

[12] “Magrath Town Council Minutes,” 7 May 1919. We get an interesting glimpse of the Empress Theatre profits in this exchange and it would be important to recognize that this was the time of the Spanish Flu pandemic.

[13] Comment of Melvin Godfrey before the Magrath Town Council, Minutes of 14 March 1934.

[14] “Melvin Godfrey,” 2.

[15]“Magrath Town Council Minutes,” 3 July 1912. Also, Melvin’s biographical document mentions he was justice of the peace at the time as well as on his fiftieth wedding anniversary, which was in 1947. It is therefore assumed this document was typewritten in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The last entry in his journal, “Court Cases Held by Melvin Godfrey, 1946” was written on 5 March 1947. For “passing another vehicle on a hill,” the fine was $2.50 ($27), court costs $4.50 ($48).

[16] Bailiff is the British term for a sheriff. Although utilizing different terms, Melvin was the only law in the town. It would appear that these were responsibilities for which payment was rendered for services performed, but not full-time employment positions as considered in the modern day. Dates of appointments overlap considerably. Magrath was a small, growing town, with expanding municipal and business ventures.

[17]“Hyrum Ririe,” in MDHA, Irrigation Builders, 513–14, 527.

[18] This was likely Hyde Taylor. See MDHA, Irrigation Builders, 527.

[19] Melvin Godfrey, “Brief History of Melvin Godfrey,” 7–9.

[20] “Court Cases Held By Melvin Godfrey, 1946.” Original handwritten journal in Godfrey Family Papers, copy placed with the Magrath Museum.

[21] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, conducted by the author, 1972, Godfrey Family Papers.

[22] “Life of Bertrand Richard Godfrey,” recorded by Kathleen Godfrey-Watts, 3 February 1980, 2, Magrath Museum. See also Floyd Godfrey, Just Mine: Poetic Philosophy (Mesa, AZ: Chrisdon Communications, 1996), 36.

[23] Arlene Janet Payne-Godfrey, “Magrath School Bell Memories,” September 1993, 1–2, transcript in Godfrey Family Papers.

[24] “Hither and Yon,” Magrath Store News, 10 November 1933, 3. “Hither and Yon” appears to be a school edition of the Magrath Store News.

[25] Bert records that this incident occurred when he was thirteen or fourteen years old, which would make the year 1911 or 1912. The Model T’s Fords were manufactured 1908–27. See “Life of Bertrand Richard Godfrey,” 2.

[26] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 1972.

[27] “Life of Bertrand Richard Godfrey,” 3.

[28] “Our Pioneer Heritage: The Charles Heber Dudley Family” (n.p., 2008), 267–68, Magrath Museum.

[29] MDHA, Irrigation Builders, 442–45.

[30] Douglas Godfrey, “Memories of My Father, 1818–1957” (6 December 2011), 1; see also “Memoirs of Lottie Harker,” 5.

[31] “Ordination Certificate,” Floyd Godfrey Family Papers.

[32] Harker and Bly, Power of the Dream, 71–73. MDHA, Irrigation Builders, 388–91, 394.

[33] “Celebrate July 24th Magrath,” Magrath Store News, July 1934, Magrath Museum. The Magrath Store News was a mimeographed publication of the Magrath Trading Company, Ltd.

[34] MDHA, Irrigation Builders, 459.

[35] Douglas Godfrey, Letter, 2 January 2013.

[36] MDHA, Irrigation Builders, 157.

[37] MDHA, Irrigation Builders, 157.

[38] Douglas Godfrey, “Memories of My Father . . . ,” 2. See also Mervin Godfrey, “I Remember an Autobiography,” 8.

[39] Douglas Godfrey, 7 October 2014. “Autobiography of Douglas Godfrey” (22 November 2009), 8, Godfrey Family Papers. There is a discrepancy in dates reported as to when the Empress was sold to the Brewerton Brothers. Douglas Godfrey reports 1945. One Magrath Museum document, titled “Empress Theatre,” by Nyal Fletcher, indicates that the Empress was sold to the Brewerton brothers in 1930. Furthermore, both “Lee Brewerton & Moving Picture History of Brewerton Family” and “Empress Theatre” by Steele Brewerton report it being sold in 1930. These articles are from the Steele Brewerton Family Files. However, “Park Theatre Magrath,” from the Steele Brewerton Family Files, indicates floor plans and that the construction of the Magrath Park Theatre was to be done between 1947 and 1948. These are all secondary sources and primary documentation is not available. Thus, both dates are possible. A convincing argument for 1945 is the substantial history on the “potato” movies featured by the Godfreys during the Great Depression as well as the Park Theatre construction permits of 1947.

[40] MDHA, Irrigation Builders, 154–55.

[41] MDHA, Irrigation Builders, 155. See also Tandy Stringam, “Nyal Fletcher: Memories of Magrath’s Movie Theater,” Magrath Museum. Fletcher’s memories do not always correlate with other accounts. It is unknown as to when they were written. Fletcher was a boyhood friend of Douglas Godfrey, the youngest of the Godfrey boys.

[42] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, March 1982, in Godfrey Family Papers. Earl Pingree Tanner Sr. had come to Magrath in 1903 from Afton, Wyoming. MDHA, Irrigation Builders, 525. See also Power of the Dream, 57, 150.

[43]“Magrath to Get a Fine New Picture House,” clipping from an unidentified Raymond, Alberta, newspaper, 16 April 1915, from personal files of Steele C. Brewerton, Cardston, Alberta.

[44] Musser, Emergence of the Cinema, 443–44.

[45] “Magrath Town Council Minutes,” 6 May 1915. See also Floyd Godfrey, oral history, March 1982, Godfrey Family Papers.

[46] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 1972. See also MDHA, Irrigation Builders, 466–67.

[47] Richard Koszarski, An Evening’s Entertainment: The Age of Silent Feature Film (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 263–71, 288–91.

[48] Koszarski, An Evening’s Entertainment, 259.

[49] MDHA, Irrigation Builders, 157. See also Tandy Stringham, “Nyal Fletcher: Memories of Magrath’s Movie Theater,” Magrath Museum; Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 1972.

[50] Mervin Godfrey, oral history, 7. See also “Life of Joseph Godfrey,” 22; and Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 1972.

[51] Koszarski, An Evening’s Entertainment, 90. For technological advances, see 139–61.

[52] MDHA, Irrigation Builders, 415–16; see also “Information from Jack Harker, December 7, 1986,” from the Steele Brewerton Files. Copies in Godfrey Family Papers.

[53] Magrath Store News, 28 November 1934. This paper advertised The Parole Girl, starring Mae Clark and Ralph Bellamy, and Soldiers of the Storm, starring Reg Toomey and Anita Page.

[54] Bessie Godfrey, “Life of Joseph Godfrey,” February 1979, 23. Bessie was the wife of Joseph, the son of Melvin.

[55] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, March 1982. See also MDHA, Irrigation Builders, 154.

[56] Melvin Godfrey, oral history, interview by Floyd Godfrey, 25 March 1982, 5. See also Godfrey Family Papers, “Life of Joseph Godfrey,” 23.

[57] Douglas Godfrey, “Memories of My Father Melvin Godfrey, 1918–1957,” 6. See also Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 1972, Godfrey Family Papers.

[58] Handwritten note from Floyd Godfrey to his son Kenneth, n.d. Reproduced by Lorin Godfrey for the 2008 Godfrey Family Reunion, Godfrey Family Papers. See also Floyd Godfrey, oral history, 1972.

[59] Joseph Godfrey would later become one of the directors of the association. See “Theater Convention at Calgary,” 15 September 1957, clipping from an unidentified newspaper; Bessie Godfrey, “The Life of Joseph Godfrey,” 54.

[60] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, March 1982.

[61] Douglas Gomery, A History of Broadcasting in the United States (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2008), 1–7.

[62] Handwritten note from Floyd Godfrey to his son Kenneth, n.d. Reproduced by Lorin Godfrey for the 2008 Godfrey Family Reunion, Godfrey Family Papers.

[63] Floyd Godfrey, oral history, March 1982.

[64] Eva Godfrey, “A Life Sketch,” 6, Magrath Museum.

[65] Douglas Godfrey, “Memories of My Father Melvin Godfrey, 1918–1957,” 8.

[66] Bessie Godfrey, “Life of Joseph Godfrey,” 34.

[67] Lorin Godfrey, “Grandpa Melvin Godfrey,” 4 December 2012, Godfrey Family Papers.

[68] Bessie Godfrey, “Life of Joseph Godfrey,” 11, Godfrey Family Papers.

[69] Eva Godfrey, “Eva Jones Godfrey, A Life Sketch,” 7.

[70] Douglas Godfrey, “Memories of My Mother: Eva Jones Godfrey, 1918–1963,” (1 July 2012), 1–3.

[71] Mervin Godfrey, “I Remember and Autobiography,” 2.

[72] The Eaton Company of Canada was a major retail store. The Eaton’s mail order catalog was published from 1884 through 1976. These catalogs sold merchandise of all kinds throughout the rural populations of Canada.

[73] Mervin Godfrey, “I Remember and Autobiography,” 1.

[74] Mervin Godfrey, oral history, 1–2.

[75] Douglas Godfrey, “Memories of My Mother: Eva Jones Godfrey, 1918–1963.” See also Floyd Godfrey, oral history, March 1982.

[76] Breakfast, dinner, then supper was the British connotation and order. Lunch was something packed in the morning and taken to school or out into the field for a work lunch.

[77] Douglas Godfrey, “Memoirs of Lottie Harker” (taken from notes and interviews, 1999–2001), 3–4, Magrath Museum.

[78] “Memoirs of Lottie Harker,” 4.

[79] “Eva Jones Godfrey, A Life Sketch,” 9.