On the American Frontier

Donald G. Godfrey, "On the American Frontier," in In Their Footsteps: Mormon Pioneers of Faith (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 35–70.

Joseph Godfrey’s family felt the venom of anti-Mormon mobs attacking Nauvoo, Illinois, during the winter of 1845–46. They were forced to abandon their home and farm, and they lost children to illness during the cold winter months, but they continued faithfully working and saving money to make the trek to Utah. The western frontier was the new landscape of the lives of Joseph and Sarah Godfrey. They were shaped by their faith and the immigration experiences of the Mormon Trail. In Utah, they evaded most of the persecutions surrounding polygamy because Joseph’s first wife, Ann, had died and his second wife, Mary, purchased and lived in her own home, leaving only Sarah in the original home. Their children, however, were keenly aware of the tensions surrounding the US marshals hunting the polygamists.

At the same time, more people were moving westward, with settlers traveling along the Oregon Trail to the California gold rush.[1] And Mormon settlements sprung up throughout the West and northward into the Canadian territories. Families moved at first to secure religious freedom, avoiding the persecution of Missouri and Illinois and later the increasing antipolygamist sentiment of the United States government. By the late 1800s, the government wrestled legal control of Utah from the Mormon Church leadership and awarded it to non-Mormons. This action created increased persecution and the division of polygamous families. Polygamist husbands were driven into hiding throughout Utah, Idaho, Wyoming, and Arizona, and even internationally in Mexico and Canada.

The Oregon Trail was used by people of all faiths and ambitions, coming from Europe and the eastern United States into farmland and the California gold fields. These movements all intersected with the Mormons. The Utah Latter-day Saints who remained in place often restocked westward travelers and freight wagons with the necessary provisions for their journeys as well as took advantage of some unique missionary opportunities as venturous travelers passed through Utah.[2] The Saints on the move also used these trails and the rapidly growing railroads to seek employment and get out of harm’s way. The marshals looking to arrest polygamists focused primarily on Church leadership, but no one felt safe. The expanding population of the West created farms, new towns, and industry; aided in the building of the Mormon economy; and provided new places to hide.

US expansion spread when the transcontinental railroad was completed, followed by the north–South spur lines, transporting goods and people where they had never traveled before. Temporary railroad towns emerged and often disappeared quickly when construction ended. They provided work and refuge for the polygamous fathers. It is in this context that the Saints moved into Canada, Mexico, and throughout the West. The earliest movers had only covered wagons, and then the railroads, to move about. Young Melvin Godfrey would be among these frontier movers.

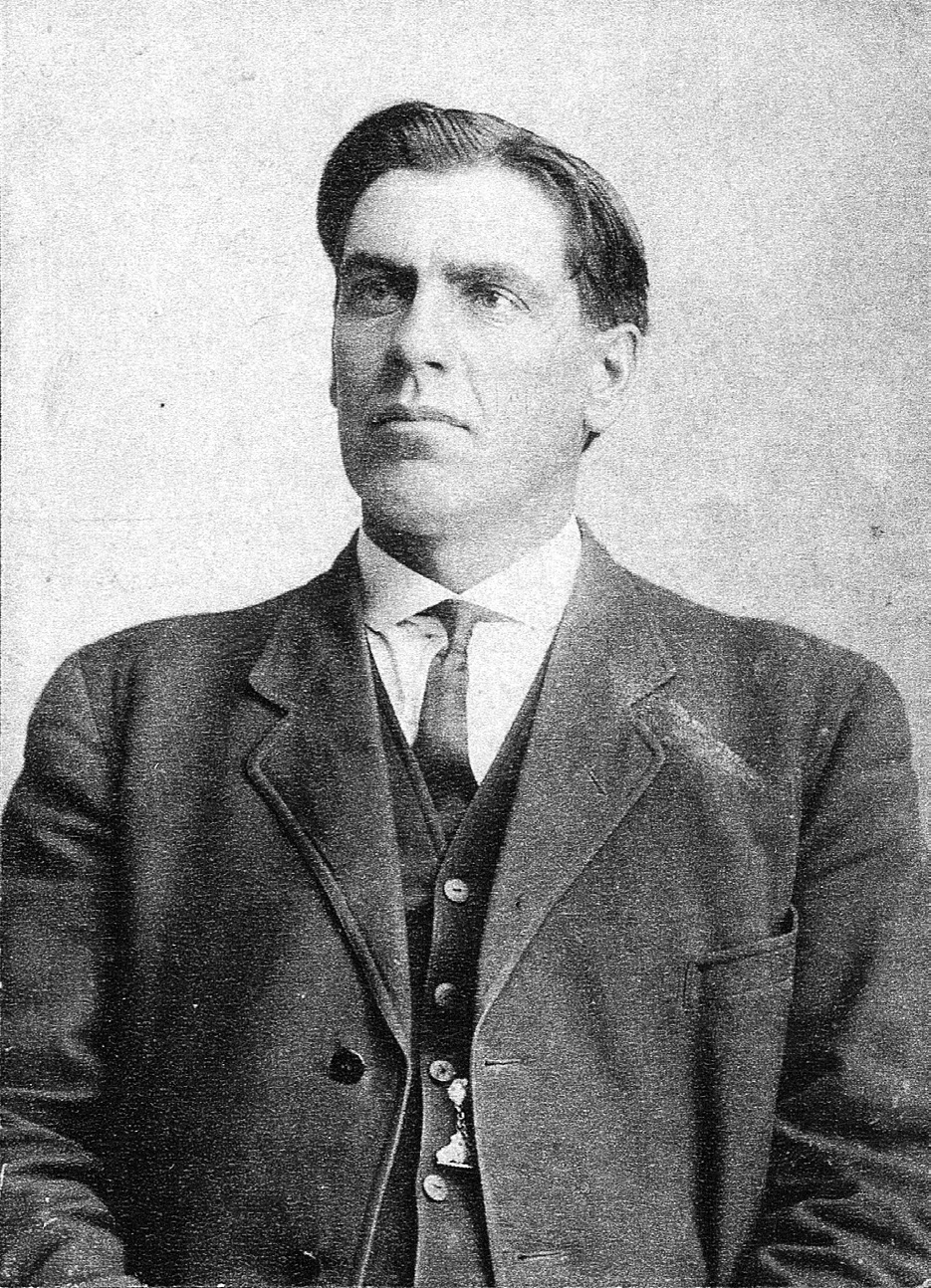

Melvin Godfrey (1878–1956). Courtesy of Melvin Godfrey Family.

Melvin Godfrey (1878–1956). Courtesy of Melvin Godfrey Family.

Melvin Godfrey (1878–1956), the eighth son of Joseph and Sarah Ann Price Godfrey, was born 15 October 1878 at 11 a.m. His father was seventy-eight years old. Two years later, Josephine completed the family and was barely a month old when their father died. All that Melvin remembered of his father was being lifted by a family member to “look in the coffin” to see him.[3] Melvin and Josephine were raised by their widowed mother and their older brothers and sisters. They lived with Joseph’s other children, all growing up as a close-knit family unit. They were “imbued with the pioneer spirit,” bonded together in work, love, and friendship. Melvin’s childhood was challenging. He was without a father. Daily farm chores required physical labor, as was the norm of rural farm life. His mother and sisters took care of the little ones as well as handling chores. They all learned the meaning of hard work—milking cows and feeding the cattle, horses, pigs, and chickens. As Melvin grew, his responsibilities included four acres of onions that needed constant weeding. Its yield was 1,400 bags per acre, for a total of 5,600 bags. This kept a boy busy. “Josiah and I done most of the weeding, crawling on hands and knees and topping the onions.”[4] They worked in the garden and the fields of hay, onions, and sugar beets. They were poor. Melvin had no clothes of his own, save for “hand-me-downs” from his brothers—“any kind of clothes . . . would do that would cover a person[‘s] body,” he wrote. At school, he wore a pair of brass-toed boots and an old jacket hood covering his head.[5] During these pioneering years, everyone made do and learned to make what they needed. Melvin learned rugged independence and the importance of education.

Educating the Family

Education was actively encouraged by Melvin’s family, the community, and the Church.[6] It was part of growing up. And it was important enough that schoolhouses were among the first buildings constructed in Utah communities. The older Godfrey children attended North Ogden’s first schoolhouse. It was a log house built in 1851, just one year before Joseph arrived.

By 1854, there were forty-seven families in the community, and the Godfrey family was one of them.[7] They used a second schoolhouse, built four years later using adobe brick. The school had an east–west layout, 30 x 60 square feet. The inside furnishings were handmade. Benches were pine logs hauled from the mountains and sawed in half. Children sat on them or, if they were writing, would kneel on the floor and use the flat surface of the log as a desktop on which to write. Individual chalk slate boards were used for drawing and multiplication questions. Writing quills were even made by the students, likely shaped from a feather. During winter, an open fireplace at one end of the building provided the only heat. Any classroom books were those of families who had brought them across the Plains. Tuition was $3 ($80) per term and could be paid either in kind, cash, or service. Service included gathering wood from the canyons for the fire, janitorial work, or providing teacher support.[8]

Melvin and Josephine started their education in North Ogden’s third schoolhouse, which was constructed in 1882. This was the same year that the Edmunds Act, an antipolygamy legislation, was passed in the US Congress. Melvin’s first school year was 1885–86. His class met in the new red brick structure known as the Sage Brush Academy. It had two windows. Students still sat on the log benches, but these were cut just long enough for only two children. Heat still radiated from a stove in the middle of the room. By 1890, Melvin’s class moved into the new Red Brick Schoolhouse, a major step forward, with more windows, five rooms, and a tower. The community and its children were growing.

North Ogden school of Melvin Godfrey’s Childhood. Courtesy of North Ogden Museum.

North Ogden school of Melvin Godfrey’s Childhood. Courtesy of North Ogden Museum.

Melvin and the children of North Ogden started their school days like many of the pioneer children. School began after morning chores at home. Then, as today, school got the kids out of the house as well as gave them an education. Children all walked to school in the sun, snow, or rain. Before class started, they played outside. At the sound of the bell, they lined up and marched inside. There were no age requirements for starting or ending a student’s school experience. There were no grade levels. The curriculum focused on reading, writing, arithmetic, penmanship, memorization, and manners. Each day began with the recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance and the Lord’s Prayer. Discipline was strict and swiftly administered with a hickory stick. A turn-of-the-century song depicting the discipline was written by Will D. Cobbs, “School Days.” The lyrics sang, “School days, school days, Dear old golden rule days, ‘readin’ and ‘ritin’ and ‘rithmetic,’ Taught to the tune of a hickory stick.” The stick kept the children in check. They talked only when called upon or when they raised their right hand for permission to speak. They could be excused only for a drink of water or going to the bathroom, which would have been outside. There were generally two terms in the school year: summer, from May to August, and winter, from November through April. These schools did not always see boys during planting and harvest seasons. They were needed in the fields. It did not affect their grades, as when they returned they simply picked up with the reader where they were prior to harvest. 11 Unlike today, the pioneer children were grouped according to skills and ability levels, not age or grade levels. They worked themselves through a series of readers. A “reader” was a saddle-stitched workbook which presented drills and checks on student comprehension. They were an organized series of individual progressive learning exercises. Children colored, worked the problems, and basically wrote in and all over their own individual books. When the exercises of each reader were completed and checked by the teacher, then the student advanced to the next level reader. One teacher taught all reader levels.[9]

Melvin was seven years old when he was given his first reader.[10] His schoolmaster was John W. Gibson.[11] Mr. Gibson was a harsh, no-nonsense teacher. His hickory stick enforced a “no talking” rule even when students whispered to the pupil in the next seat. He allowed no one out of his or her place during school hours. Students of all ages had a great respect for him, as well as a fear of his corporal punishment with the hickory stick across a pupil’s hand or hind end for even the smallest infraction. Melvin was afraid of Gibson. He dared not even raise his hand to ask to be excused. So he said, one day, “I had to fill my pants. Then he [Gibson] sure did let me out.” However, these were also the days when, if a child was in trouble at school, he or she was in more trouble at home, and so he “got a good ‘lickin’ from [his] sister, when [he] could not [even] help it.”[12]

Melvin did like his second teacher, John M. Bishop.[13] Now eleven years old, Melvin had made it through the first four readers. His interest in learning was encouraged, and he appeared to enjoy school. Edward Joseph Davis was his third teacher, and he helped Melvin “finish up to the eighth reader learning more than I ever learned in all my schooling.”

Melvin’s final instructor was a young lady named Jane West.[14] She was a “lovely person, quiet, gentle and loved music.” She took an interest in Melvin and helped him finish his ninth and tenth readers. It was she who “finished my education.”[15] Melvin was stricken with this teacher, but his success might also have had something to do with the fact that she was boarding at his home and with his family. In short, communication between mother, teacher, and student was extremely efficient.[16]

Growing-Up Strains

Melvin and the children of North Ogden felt the increasing strain of the 1882 Edmunds Act and particularly the later Edmunds-Tucker Act of 1887.[17] They were confused about why the US Congress had passed laws deeming their families illegal. They saw the result from a child’s point of view. The 1887 act awarded court jurisdiction to non-Mormons and set punishment for polygamy at six months in prison and a fine of $300 ($7,394), a fine that a family could not hope to pay. For the children, the scariest threats were from swarms of deputies who patrolled belligerently through the streets. The youngsters panicked when marshals dramatically burst into their homes unannounced. “Terror, frustration and embarrassment were multiplied many fold among all husbands, wives and children of plural marriages.” Families were split. The polygamist fathers disappeared into the Mormon Underground to avoid persecution. They were forced to leave wives and children without support.

Although Melvin’s polygamist father had died, Melvin knew polygamist families within this tight-knit community. It was during this time that he finished his education, worked in northern Utah, and then left home to work in Oregon’s construction boom.

As a teen, Melvin led a herd of horses to the grasslands of northern Utah at “the Promontory and lost every one of them.”[18] The Promontory is a mountain in northern Box Elder County almost at the Idaho border. He took a herd north for summer grazing. His family owned land in the area where the grass was reportedly “waiving around their horses’ knees, and occasionally as high as the stirrups of the saddles.”[19] Of the horses with him that day, Melvin “lost every one of them.”[20]

Melvin reported that his horses were stolen and that he had spent the entire summer searching for them. The only thing he found was a “beautiful saddle.” A few months later, the owner claimed the saddle, and Melvin received a fifty-cent reward for his efforts ($13). The horses were a major loss, and fifty cents was a limited reward for a young man who was pasturing the horses some fifty miles north of his home. There was a goodly bit of cash value lost when the herd was rustled away: a saddle valued around $60 ($1,536), work horses around $150 ($3,839), and a good saddle horse at $200 ($5,119). What remains unknown were the number of horses in his herd. But by any calculation, this was a significant loss to the family and a traumatic experience for a young man.

At age sixteen, Melvin was finished with his schooling and “ran away from home.”[21] In his writings, he gave no reason, but had just lost a valuable herd of horses to rustlers. Antipolygamy antagonism, fear, embarrassment, and tensions were high throughout the community, and Melvin was a robust, active young man confirming his independence. Melvin’s destination was Huntington, 380 miles northwest of Ogden and just across the eastern Idaho border into Oregon. Huntington was originally a small trading post until the railroads and construction stretched along the Snake River into the Northwest. Then it quickly transformed into a Union Pacific town, as it sat next to the junction of the Oregon Short Line and the Oregon Railroad, and next to the later expansion of the Northwest Railroad Company line down the Snake River. Melvin likely traveled northwest using the Oregon Short Line railway. He found work in Huntington with the railroad crews and in related building projects. It was physical, strenuous work amidst a rather crude, unruly crowd.

Melvin worked a while and “soon found out home was the best place and went back.”[22] The railroads attracted a transient, rough drinking crew. These workers lived outside the gospel standards ingrained by his home and community. The work was every bit as taxing as weeding onions, and he missed his family. He returned home, and in the act of rededicating himself, he was baptized anew 28 February 1894.[23] Rebaptism was a common practice at the time, and it reflected the sixteen-year-old’s renewed commitment.

Courtship

Back in North Ogden, Melvin worked the farm until just past his twentieth birthday. Topping and bagging onions remained his primary job, second only to chasing girls around “N.O. [North Ogden] wild as a Billy goat, not mentioning some of the things I done.”[24] “Chasing girls” segued into “chasing around with girls,” as was natural for his age. The special one in the pursuit was Eva Jones (1879–1963), daughter of Richard Jones and Elizabeth Wickham.[25] Melvin wrote that he talked Eva into marrying him. “I don’t think she ever did think much of me,” he said, “but I talked her into it so she did [it] to get rid of me,” he joked.[26]

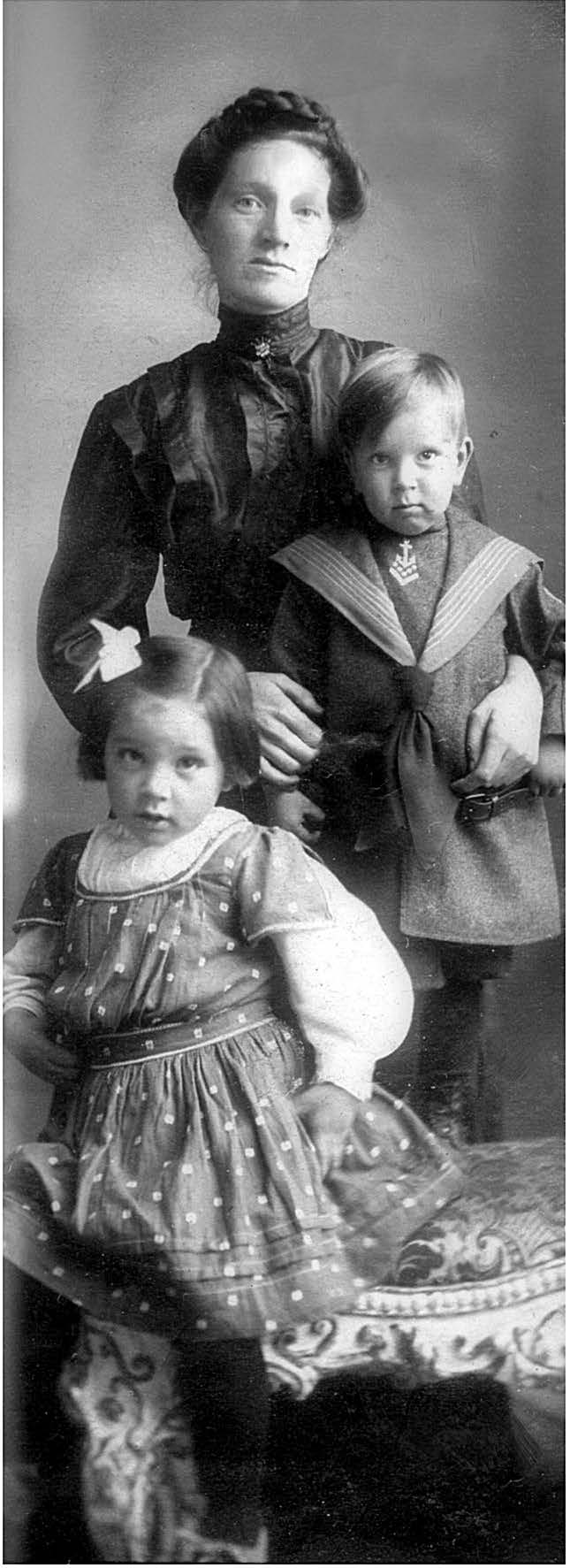

Marrying was not really a good way to get rid of a suitor, and Eva was, indeed, in love. She had fallen in love with Melvin at age fifteen, when her father had allowed her to attend dances: “I fell in love with Melvin Godfrey w[h]ich [whom] I married 4-years later.” Melvin was ordained an elder on 3 March 1897 by his future father-in-law, Richard Jones, and Melvin and Eva were married in the Salt Lake Temple the next day 4 March 1897.[27] They were both nineteen when they married. The marriage was solemnized by John R. Winder and witnessed by William W. Riter and George Romney.[28] After Winder had completed the sealing, he suggested to Melvin, “Kiss the bride”, Melvin later recalled, “I did not even know enough to do so.”[29] They celebrated their fiftieth wedding anniversary in 1941 and lived together for fifty-nine years before Melvin passed away on 6 April 1956.

Eva Jones–Godfrey (1879–1963), with daughter Lottie and son Floyd. Courtesy of Melvin Godfrey Family.

Eva Jones–Godfrey (1879–1963), with daughter Lottie and son Floyd. Courtesy of Melvin Godfrey Family.

Family Migration

Eva Jones was the youngest of six children born to Richard Jones and his second wife, Elizabeth Wickham, in North Ogden on 25 May 1878. She was five months Melvin Godfrey’s senior, a spiritually sensitive, stern young woman. She was thin, with dark blue eyes and rich auburn hair to her waist, which she wore braided and wound in a bun on the top of her head to keep it out of the way when she worked. She was shy and conservative, but she fit in easily with everyone.

Eva’s family were pioneers too. Her father, Richard Jones, was born 24 October 1824 in London, England.[30] Her mother, Elizabeth, was born 14 February 1833 in Eastwickam, England. In his youth, Richard, like Joseph Godfrey, had commenced a life on the ocean. He loved to travel.[31] He sailed the oceans and global ports of call—to Constantinople and the Isle of Patmos, through the Black Sea into Russia, and around the capes of Africa and South America. These were phenomenal experiences for a lad, even by modern standards, and significantly more so given the early 1800s. He was near the seas until his marriage on 19 November 1849 to a London orphan named Naomi Parson.[32] He wanted to be with his new family, so he gave up his job on the seas for a management position on London’s harbor loading docks.

While working the docks one day, Richard found several discarded LDS religious tracts. He was interested. He embraced the gospel and was baptized a member of the Church on 1 February 1852. He served as a missionary in London and was among the local leadership of the Church for almost a decade before he immigrated to America. With his family, he sailed from London on 4 June 1863 aboard “the splendid packet Amazon,” with 895 saints aboard.[33] A packet ship was a few steps above what Joseph and Richard likely sailed in their early careers at sea. A packet vessel had a regular schedule transporting people and cargo across the Atlantic. The term “packet” originates with early mail delivery that arrived in packets. Charles Dickens visited this ship before departure and described, “These people are so strikingly different from all other people in like circumstances whom I have ever seen, that I wonder aloud, ‘what would a stranger supposed these emigrants to be!’”[34] Richard and Naomi had six children, who all sailed to America aboard the Amazon.

Richard was well-to-do and paid the ship’s fare for his family as well as for thirty other Saints.[35] During the journey, the Church members were organized into wards to maintain order and protocol. They held regular morning and evening prayers, conducted their regular Sabbath services, and organized a brass band. There was an abundance of speeches, socialization, and worship. In the evenings, the deck was cleared of all women at 9 p.m., and guards were posted to see that “no female went up after that hour . . . and no sailor went below.”[36] They encountered a few fearful high winds and blustering seas over the thirty days of their journey, but they arrived safely in New York, 18 July 1863.[37]

From New York they rode the train to St. Joseph, Missouri, where they eventually joined with the company of Thomas Ricks and a group of “light-hearted saints, bound for the promised land, now only a thousand miles away.” Their only impediments were avoiding the “strife of the Civil War . . . raging in the United States.”[38] The trip took four months and one day from London to Utah.

Upon arrival, Richard asked where they should settle, and Brigham Young suggested they go “north and settle near the head of a stream.” Those general directions took them to North Ogden, where they arrived 10 October 1863. They settled on what became known in the family as the “cat claim.” It was a location with water already used by the native Shoshone, who claimed “squatter’s rights.”

The cat claim story emanates from a lady who wanted to repay Richard for her passage to America. She had no personal possessions except for a “nice house cat,” which Richard’s children wanted, and the woman was insistent. Thus, the children acquired their first pet, taking loving care of it and playing with the cat all the way across the Plains. As it happened, in North Ogden, when Richard was negotiating with the Indians for the land, one of them spotted the cat and wanted it. Reluctantly, the children gave up their household pet, the land rights were exchanged for the cat, and their farm became known as the “cat claim.”[39]

In North Ogden, the Jones family at first lived primarily on sego roots as they worked clearing the fields of rock and sagebrush. They plowed and planted sugarcane and worked in a ruit orchard with raspberries. After a few years, tragedy struck. Naomi became ill and was moved one mile into town to receive better care. The children and Richard visited Naomi often. The move seemed to hurt Naomi’s pride, yet she remained stalwart, serving as her health allowed, and Richard managed the two homes. Sadly, she died January 1876.[40]

Richard’s second wife was Elizabeth Wickham. They were married 8 February 1870. Elizabeth moved to the farm after Naomi had moved into town. She and Richard had seven children—Emma Georgina and Emiline (twins), Rosabel, Abraham (Lee), Mary Elizabeth, Joseph Edward, and Eva.[41] With Elizabeth’s and Naomi’s children, there were fourteen in the household. They all worked, harvesting fruit from the orchard. Richard loved raspberry jam and jelly. Elizabeth was now “the Lady in his household.”[42]

They were married eleven years when calamity struck again. Elizabeth took sick at home one day when smoke began filling the house. When she opened the bedroom door, the room was ablaze. It frightened her so severely that she suffered a stroke. Little Eva, three years old, was out picking berries, and by the time she returned home, “the house had burned to the ground.”[43] Two weeks later Elizabeth died, 21 October 1881.[44] The home was rebuilt, but this series of events would be life changing for Eva. She never overcame her fear of fire.[45]

In December 1881, Richard married his third wife, Mary Ann Duckworth.[46] A few years later, he married again. His fourth wife was the widow Margaret Walwork. He was seventy years old, she was fifty-nine, and Eva was an impressionable teenager at age fifteen. She missed her mother terribly.[47]

Richard would have a long life, surpassing each of his wives. He was an avid reader of world and Church literature, elders quorum president, and part of the North Ogden First Ward quorum’s presidency for thirty-five years. At this same time, Joseph Godfrey was a fixture in the bishopric, so they knew each other well. Their common sea adventures and gospel service likely made them devoted friends. Richard was active in building the community, constructing canyon roads, and logging the mountains for lumber to build schools, houses, and bridges. He developed irrigation throughout the area, plowing ditches and canals to divert the water to the farms and orchards. “Whatever was needed, he gladly lent a helping hand.”[48] He passed away at the age of ninety on 24 September 1914.

Love, Ghosts, and Dancing

Growing up, Eva was afraid of her stepmother Mary Ann Duckworth. She described her as “a nice lady, but real strict.”[49] Eva always respectfully addressed her as “mother,” likely out of fear of displeasing Mary or her father. On one occasion when Eva was invited to go to Church general conference in Salt Lake City with her father, Eva refused to let her mother bathe her. As a result, she was not allowed to accompany him.[50]

Her father recognized his daughter’s anguish following the loss of her own mother and his new marriage. He stepped in, and over the years the two developed a close relationship. He took Eva into the fields with him when she was little. She rode the plow horse while he worked—preparing, planting, and caring for the crops. She rode in the wagon, taking hay to the barn for the winter. She gathered eggs from the chicken coop and worked in the orchard, all just to be near her father and do her part as a member of the family. She took her childhood wagon into the orchard and gathered the apples fallen from the trees and fed them to the pigs. When she got older, she was allowed to go for “papa’s mail.” Her father was always full of praise, always loving and thanking his baby girl. “He was so kind,” she wrote.[51] The affection was mutual. “How I loved my father when he came in from the fields tired and dirty. I would bathe his feet to rest him.”[52]

As the years passed and her stepmother became ill, the mother-stepdaughter relationship failed to improve. Mary Ann even told Eva she would come back and haunt her after Mary died. Mary Ann Duckworth-Jones died 12 March 1894. Eva, now sixteen years old, was left in charge of the household. Her sisters were working outside of the home and had married. Eva also worked at the North Ogden Telephone Exchange to help support the family.[53] She cooked the meals and churned the cream into butter for her father and brothers, Abraham (Lee) and Joseph.

One dark evening, Eva was casually walking along the dirt road home with a friend, returning from a teenage party in town. As they strolled happily along like any two young teens, a ghost appeared in the center of the road. It was standing there like an evil spirit in the air above the gravel. “It stood one foot off the ground. It was white.” Eva screamed to her companion, “That is my mother.” The girls were so frightened they ran screeching all the way back to town. Wildly knocking on the door, a friend let them in, and they relayed the ghost story. It had stood above the road, with its white robe flowing in the wind. They were sure they had seen the ghost of Eva’s stepmother. The patient friend got his dog, and, with the two girls following slowly behind, he returned to investigate. The ghost remained, floating above the road. They approached cautiously. Then the would-be ghost turned slowly around to its side and walked away. “It was my pony! She had been [walking] in the mud, so it looked like she was standing off the ground,” with her white mane flowing in the wind.[54] It was a humorously sad story repeated through the generations.

Eva, now the lady of the house, was still a teenager who loved being a kid. She loved attending Church dances and parties and pulling candy. Her older stepbrother owned the hall where the dances were held, so Eva thought of herself as quite important. She attended the dances at her brother’s hall and other events like the traveling Chautauqua speakers and vaudeville performances. Boys were in pursuit, but “they had to be Mormon boys.” Eva’s father may have held her heart in his hand, but he too was strict. He told one young man, Jessie Woodruff, that she could not go to the dance with him because he did not belong to the Church. Eva wrote that he later joined the Church and was a fine man. Her successful suitor was Melvin Godfrey. She and Melvin won a “prize waltz,” and along with the waltz came Eva’s heart.[55]

Honeymoon

There was no honeymoon for the new couple. The first month and ten days of their marriage were spent working on the farm of Melvin’s uncle John Price in Malad, Idaho. Malad was just south of the Utah/

Losing the North Ogden Farm

Melvin and Eva farmed Joseph’s original thirty-three acres, now in the hands of his mother, Sarah, who lived in North Ogden. They did very well “raising sugar beets, onions, hay . . . a couple of cows and four nice pigs.” A baby boy joined the newlyweds. Their firstborn son, Bertrand Richard, arrived on 4 February 1898. On the family farm, Melvin thought he had the beginnings for his family. But it was going to be a difficult launch.

For some reason, his father’s estate was dragging slowly through the probate courts—eighteen years after his death.[57] Joseph had left no last will and testament, so his assets were placed in probate court to administer the affairs of his estate. The probate was not filed until 9 July 1897, just after Melvin and Eva had returned and planted a crop. In 1898, creditors were invited to submit claims before the probate administrators. The probate and guardianship notices appeared in the Ogden Standard Examiner for almost all of 1898 and a part of 1899.[58] Why probate was so long after Joseph’s death remains unknown. It would be accurate to say that the farm remained active and productive. Sarah and her children lived in the home, worked the land, and rented some of it. They were making it.

Jeremiah, Melvin’s older brother, was appointed the administrator of the estate along with three local appraisers. The farm and stock Joseph held in two irrigation companies were assessed at $4,543 ($123,372), along with water rights. The total value was $4,940 ($124,182).[59] There were no debtors. Jeremiah petitioned for a family allowance of $150 ($4,074) to support his mother, who was now fifty-six years old, his sister Josephine (eighteen), and Melvin, a newly married twenty-year-old with a wife and child. The petition was granted. On 26 November 1898, J. H. Lindsay objected to Sarah’s rights to the homestead based on the facts that the farm was still solvent and at the time of Joseph’s marriage he had another wife living with him.[60] As a result of this objection, a hearing was scheduled and creditor notices began appearing in the Ogden Standard Examiner.

In conclusion, there were sixteen heirs to the estate, including Sarah. The court awarded Sarah one-third of the farm, and the remaining two-thirds was divided among the children: William, George, Reuben, David, Jeremiah, Josiah, Melvin, Joseph, Josephine and John Godfrey, Mary and Martha Mecham, Sarah Jane Holmes, Jemima Campbell, and Emily Chadwick. Sarah received eleven acres, with the remaining twenty-two acres divided among the other fifteen children. It would not be enough to support a family.[61]

As the youngest son, and the only one still working the farm, Melvin felt he was treated poorly, even though his brother Jeremiah was the probate administrator. Unfortunately for Melvin, who assumed he would get the farm or at least enough of it to support his new family, “the oldest of the family wanted the property sold,” and Melvin’s fresh crops and the animals were sold with it. “I felt very bad about that,” was all he wrote of this turning point in his life. He inherited little of record.[62] This motivated a move, and it appears likely that whatever Melvin had received for his small share was used to make a new home in Wyoming, where a part of the George Coleman family had already relocated from North Ogden.

“Starve Valley”

The result of the North Ogden farm’s sale was that Melvin, his brother Josiah, and their wives were forced out. So they headed to Star Valley, Wyoming, to take up a homestead in a new locale. Melvin and Eva loaded all that they owned into the wagon—flour, fruit, two pigs—and started out. It was fall and winter was approaching, but the two brothers and their wives charged ahead. Their route took them through Mormon settlements in Cache Valley, up Logan River Canyon, past Card Canyon, the Beirdneau Mountain Peak, on to Bear Lake, then north into Star Valley, on the northwest side of the Wasatch Mountain Range.

The trek was challenging and was made even more so as winter engulfed them. The snow was heavy as they reached Bear Lake. Bear Lake sat in a beautiful valley at an elevation of 5,924 feet, straddling the Utah-Idaho border. They kept moving, making their way up the lake’s west side, stopping only for assistance at the small Mormon towns established by Charles C. Rich—Paris, Bloomington, and Montpelier.[63] Rich was known for his generosity, so people passing through had assistance as they traveled. The railroad had just made its way to Montpelier in 1892, and that changed the population base of that Mormon community from the original settlers to a now mixed population servicing travelers headed to Oregon and railroad workers settling the area. It had become a rail center.[64]

Melvin and Eva left the Bear Lake Valley, continuing north, ascending the mountains into Star Valley. Making life difficult, one of the horses became balky pulling the wagon in two feet of snow. The horses were cantankerous, but Melvin needed both working together to get over the mountains. The families decided to double up. Josiah’s family left its wagon at the bottom of the valley and climbed into Melvin’s wagon. The idea was to get one wagon to the top and then go back for the second. When they finally reached the top of the Salt River Wyoming mountain pass, they were at an elevation of 7,610 feet and freezing. They saw a house ahead, and it gave them hope. Melvin approached and knocked, and a man answered. Melvin asked if they could come in out of the snow and stay in the house. “No,” the man responded; his wife did not feel well. Melvin persisted “Can’t the women come in?” he pleaded. “No” was again the stern answer. Melvin, Josiah, their wives, and young babies would have frozen that night, and Melvin knew it. So when he walked back to his family’s wagons, he simply said, “Yes, you girls go right in.” Eva and Josiah’s wife, Gunda Beletta Peterson Godfrey, went straight into the stranger’s home with their two babies. The occupants looked surprised to see them, “but they let us stay. She fixed us supper and we were thankful for it.”[65]

The next day, the Godfrey brothers retrieved the second wagon and with their wives drove into what Eva later called “Starve Valley.”[66] They stayed with Moroni Coleman and his son George Moroni Coleman, who had settled earlier in the valley. Joseph Godfrey was actually the stepfather, uncle, and brother-in-law to Moroni Coleman.[67] George had moved from North Ogden to Park Valley and was now living in Star Valley and running a small dairy.[68] They were with friends and family. George had also lost a herd of horses to rustlers in Park Valley just like Melvin. Melvin, Eva, Josiah, and his wife were now among confederates, but Star Valley would yet be difficult. Through all their trials, the Colemans and the Godfreys stayed close throughout generations.[69]

Salt River Range, near Star Valley, Wyoming. Photo by Acroterion.

Salt River Range, near Star Valley, Wyoming. Photo by Acroterion.

Star Valley is a beautifully demanding Rocky Mountain region running north and south along the Idaho border in western Wyoming. It sits at 6,200 feet and between the Salt River Mountain Range in Wyoming and the Webster Range in eastern Idaho. Water is plentiful. Three rivers wind their way through the area. It remains today a rich grassland with good soil and productive farming and ranching.

Mormon settlers populated Star Valley two decades earlier, in 1879, and called it the “Star of All Valleys,” later shortened to Star Valley.[70] The falling snow was kinder for Melvin and Eva in 1899 than it had been ten years earlier. In 1889, forty inches covered the ground in just a few days, and the term “starve” made it descriptively into the valley’s title. Melvin and Eva still competed with the winter storms and severe cold. “It was very foolish to go there for the winter,” Melvin later declared.[71]

After a short time with the Colemans, Melvin and Eva rented a house about a mile away. In their first winter, Melvin had to leave to find work. Eva and Bert (who was barely two years old) were alone, but the family sorely needed an income. Melvin headed to the mountains and harvested mahogany trees. These were the curlleaf mountain mahogany, looking something like the wind-worn juniper trees of Wyoming, Idaho, and Utah. The native people used mahogany for bows and tools. The pioneers used them for construction, finer woodwork, furniture, and tools where hardwoods were advantageous. Melvin was paid $3 ($80) per cord, and it took him three days to haul a cord from the mountains.

On one occasion while Eva was alone with Bert, fixing supper and waiting for Melvin’s return, “down the road came an Indian with feathers down his back and around his head.” The Shoshone were drawn to the valley because deer and elk were prevalent. Eva was “hoping he would pass by, but he turned in. He was riding a pony. I picked up my Bert and went outside. He got off his horse walked past me and into the house” and said, “Meat and flour.” Eva didn’t have much flour, but she was “roasting some ribs for supper [and] she gave them all to him. He got on his horse and left.”[72] Eva was frightened and crying. Bert was screaming. After the incident and considerable calming of nerves, Eva realized the Indian was exploring the country, as he wore a scout’s head-dress. One wonders what Melvin got for supper when he returned.

The next summer, Melvin picked up whatever work he could in farm labor, mostly pitching hay and feeding the livestock for neighboring ranchers. He earned enough to homestead forty acres, acquire five head of cattle, and build a one-room log cabin. The cabin was 16 x 16 feet and had a dirt roof and factory cloth tacked to the ceiling logs. This kept the soil in the ceiling from falling into the bed or the food table. It also helped keep the mice and rats out of the cabin.[73] Eva wrote that they did “very well in three years.”[74]

The next winter, in 1900, Melvin again left Eva and Bert, heading east, this time herding sheep. It was the only work he could get, and it paid $40 ($1,023) per month. He drove a sheepherder’s wagon and rode with a dog and provisions. The two horses led the wagon at a walking pace. The wagon was perhaps ten to fifteen feet long. The main door was in the back. A window was in the front behind the driver’s seat, all covered in canvas. Inside was a one-man bed, a small cook stove, an ice box, and a tiny kitchen cupboard. Storage and shelves occupied any empty space. More storage was available in boxes hung outside the wagon. The sheepdog was an important companion and excellent at protecting and herding the sheep. The shepherd, once the sheep were settled for grazing, strung another canvas five feet high around the outside of the wagon, where the dog stayed, protected from the wind. When the sheep depleted the grass in one area, they packed up and moved to another pasture.

Top and Bottom: This shepherd’s wagon, circa 1900s, would have been similar to what Melvin Godfrey used in Wyoming. Replica @ Beaverhead County Museum, Dillon, Montana. Courtesy of Donald G. Godfrey.

Top and Bottom: This shepherd’s wagon, circa 1900s, would have been similar to what Melvin Godfrey used in Wyoming. Replica @ Beaverhead County Museum, Dillon, Montana. Courtesy of Donald G. Godfrey.

Melvin roamed a range he called “the Red Deseret [Desert]” that ran as far east as Cheyenne, Wyoming, and south to Greeley, Colorado. The Red Desert was a high-altitude expanse in south-central Wyoming. Both the Oregon and Mormon Trails ran through the area. Melvin herded the sheep through the grasslands of this winter range and fed “the woolleys” corn and beet pulp. He was alone in the hills with two good sheep dogs herding “two or three thousand sheep. . . . He slept and ate in the wagon. When he came [home] for provisions he would ride one horse and tied the pack horse to his horse’s tail.”[75] He wasn’t happy leaving his family each winter, and he “finally quit sheep.”[76]

Amidst life in Star Valley, their second son, Parley Melvin, was born on Christmas Eve, 1901, in Smoot, Wyoming.[77] Life was a physically severe struggle in “Starve Valley,” where neither Melvin nor Eva liked being alone. The family was growing, and Melvin heard reports of opportunities in Canada. After almost four years in Star Valley, on 1 March 1903, Melvin sold his Wyoming land and headed for southern Alberta, Canada.[78]

North to Canada

Melvin and Eva made the move from Smoot, Wyoming, to Magrath, Alberta, by train rather than trek. They sold their Wyoming homestead, making sufficient cash for their travel. It took planning and approximately two weeks in route. Even though their household belongings were to be shipped by train, they packed the wagons for the ride so that their belongings could be loaded and unloaded in bulk at different railroad transfer points. The railroad cars in 1903 were approximately nine feet wide and about forty feet in length.[79] If Josiah or the Colemans had traveled with them, it would have taken more than an entire railroad car. Livestock was generally placed in one train car, with freight and family in the other.

From the Afton area in Wyoming, they had two choices to get to a railroad center: south to Montpelier or west to Idaho Falls. It is uncertain which route they chose. Montpelier, south, was familiar territory. Idaho Falls, to the northwest, was on the Union Pacific route. The northern route crossed into the Snake River area of what is Yellowstone and reportedly some rugged territory toward Idaho Falls. Melvin’s son Mervin writes that as “they were going along the Snake River, they just about ended up in the river as the sleigh slipped off the road” and almost ditched them.[80] This suggests that they took the northwest route. But later it appears the southerly route was the choice, as “they hauled all their stuff to Montpelier, Idaho,” on a well-traveled pioneer route, which would have taken then by wagon south to the more active railroad center to catch the train.[81]

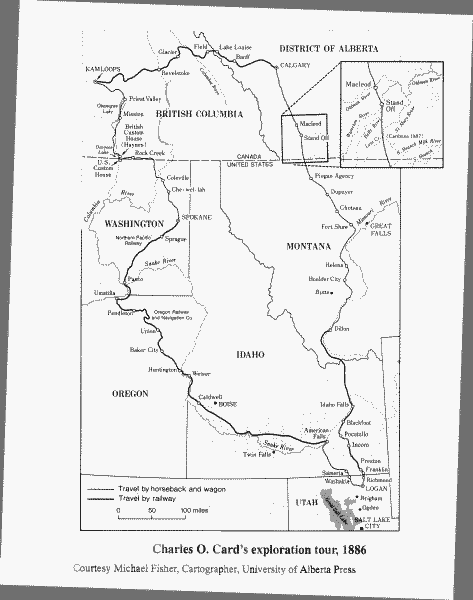

The route from Montpelier would have taken them to Pocatello, then to Idaho Falls, north to Butte, Montana, all on the Union Pacific and its subsidiaries. In Butte, the cars would have been transferred to the Chicago Burlington & Quincy Railroad (CB&Q) with the Burlington Route and its associated line through the West and on to the Canadian border. The final leg of the route took them through Helena, Great Falls, and directly north to Shelby. They crossed the US-Canadian border at Sweet Grass, then to Stirling, Alberta, Canada, where they disembarked.

The Godfreys joined many other Mormons in western Canada. The Mormons started settling southern Alberta, creating a community at Cardston in 1887. The Moroni Coleman family had moved to Canada a year before Melvin, in 1902.[82] So once again, they were among family, friends, and people of a common faith.

By the turn of the century, the Mormons in southern Alberta were farming and with their experience had teamed with Elliot Galt to develop irrigation systems throughout southwestern Alberta.[83] The rumors of cheap land and land in exchange for work on the canal spread throughout the Mormon colonies in Wyoming and Utah. Charles Ora Card wrote in the Deseret News, “We invite . . . all trades to make our towns and hamlets a success . . . and grow up within an enterprising and healthy country. Don’t forget to secure good farm land adjacent to one of the grandest irrigation systems of modern times.”[84] Southern Alberta was painted by Card poetically as possessing a variety of grasslands, grass reaching a horse’s belly, migratory bird routes, birds that serenade the forests, fragrancy exhaled from plants in full bloom, mellow sunlight, and the grasses taking on a new life.[85] Immigration and travel into Canada were improving at the same time. Short narrow-gauge railway lines provided north–south and local travel. These expansions were facilitated by increased mining and agricultural development. By 1889, Lethbridge, Alberta, and Great Falls, Montana, were connected by the Great Falls and Canadian Railway. In 1900, a route from Stirling, Alberta, to Cardston was developed through the towns of Magrath and Riley by the Galt Alberta Railway and Coal Company. Roads were dirt wagon and horse trails. There were steam automobiles appearing in the industrial East, but it is highly unlikely that any in this rural family migration had yet seen one. Trains had become the means of mass transportation and industry.[86]

The train ride to southern Alberta would have seemed luxurious compared to the covered wagon move from North Ogden to Star Valley. However, they would once again arrive in a snowstorm. They arrived at Stirling, Alberta, Canada, during “a terrible storm and couldn’t leave the station.” The snow was blinding; they could not see. They waited outside the railroad station, sitting on the northeast station benches, protected somewhat from the wind, until the next morning produced a beautiful sunshiny day. The ground was covered in deep white snow, the sky was clear blue, and it was cold.[87] Even so, immediate preparations were made to head to Magrath on horseback. Eva and Bert rode one horse, and Melvin and Parley were together on the other. The snow was so deep it came up to the horses’ bellies. The horses did not walk through the snow as much as they lunged their way through it. It was a rough ride. “How frightened I was,” Eva wrote describing the journey.[88] When they arrived, they stayed with Sarah Ann Jones, Eva’s aunt, for a few days until the train brought their provisions to Magrath.

Early LDS Communities scattered across Southern Alberta. Courtesy of Michael Fisher, Cartographer, University of Alberta.

Early LDS Communities scattered across Southern Alberta. Courtesy of Michael Fisher, Cartographer, University of Alberta.

Magrath, known as the Garden City of southern Alberta, was first settled in 1899 by Mormon settlers coming from Utah, Idaho, and Wyoming.[89] It was a small village, young and growing, incorporated in 1901.[90] Their new hometown of Magrath was a farming town. Many of the settlers were attracted by the glowing descriptions they had heard from Charles Ora Card and earlier settlers via letters and the newspaper. By the time Melvin and Eva settled, Alexander and Elliot Galt of Lethbridge had already developed the Lethbridge coal mines and wanted to establish irrigation in the region east of the Blood Indian Reserve and south from Lethbridge to the US border.[91] Galt and Card teamed with the Mormon immigrants developing the region for farming. The Godfreys and Colemans expected plenty of work, but it was not as advertised. By 1900, the first canal had already been completed. In 1902, it rained for two weeks straight, and a severe flood took out the head gates on Magrath’s Pothole Creek and threatened the community.[92] The flood created more work, but in 1903, when Melvin, Josiah, and the Colemans arrived, work seemed scarce.

Once again Melvin and Josiah were forced into traveling. This time Oregon seemed in need of carpenters and construction workers. The brothers left their wives in Magrath for a brief time. They likely caught the Great Northern Railroad out of Shelby, Montana. But finding work in Oregon was just as difficult, especially when the Oregon settlers discovered that the Godfrey brothers were Mormon and refused to hire them.[93] After a few months with no success, they returned to their families.

Eva, Bert, and Parley were alone in a tent while Melvin was in Oregon. They were dependent upon the love and generosity of their extended family, neighbors, and friends. More than food, it was their faith and love that sustained them. After they had just arrived, 6 May 1903 brought a brutal late spring blizzard. “It snowed and the wind blew for two days and nights,” as Eva remembered.[94] There were no fences on these open prairies, so hundreds of cattle from the nearby ranches stampeded toward the settler’s homes for protection from the blowing snows. Men scared them away from the scattered barns, homes, and tents as best they could. Eva was afraid the cows would run over her tent. One evening during the storm, she and her young children, now five and two years old, were huddled together. They had run out of coal. As a blizzard howled, they were hunkered down trying to keep warm and hoping for the passage of a storm that seemed endless. Eva turned to Bert and said, “Bert, we’ve got to pray!”[95] Together this young mother and her sons knelt in the dirt of their tent floor and prayed to their Father in Heaven for help. Outside the tent, the cold north wind swirled the snows, shaking their only shelter with every biting gust of horizontal snow. They did not know from where help might come or when. But they had the simple faith that “the Lord would provide.” It wasn’t but a few minutes after they had risen from their knees when someone outside called through the wind and snow, “Sister Godfrey, Sister Godfrey.” It was brother David Bingham, who lived down the road.[96] He knew of their circumstances. He knew they were alone. He carried half a sack of coal over his shoulder. “I thought you might need this,” he said as he handed the coal to Eva.[97] Then he pulled the wagon and buggy closer to her tent and tightened the ropes so that the cattle would not knock over Eva’s only protection.[98] He likely saved their lives. After the storm subsided and people emerged from their dwellings, there were dead cattle everywhere. “The men skinned them for their hides.”[99] Nothing went to waste.

Southern Alberta irrigation canal laborers with their teams. Courtesy of Magrath Museum.

Southern Alberta irrigation canal laborers with their teams. Courtesy of Magrath Museum.

Shortly after the storm, Melvin returned. Downtrodden and discouraged, he was yet determined and still seeking work. His first job in Magrath was breaking sod, which meant plowing virgin soil. The pioneers created fields for raising crops by breaking sod, and it was also a part of the expanding canal construction. Horses were hooked in teams, sometimes up to six animals pulling a single plow through centuries of hardened soil. Eva cooked for crews as well as cared for her family.

After breaking sod for a time, Melvin started working as a carpenter building houses. He moved his family from the tent they had brought from Wyoming into a lean-to, a dugout he constructed on the south bank of Pothole Creek. It was again a one-room shack. Their only possessions were a few clothes and their horses. This was the birthplace of their first daughter, Lottie, born 12 December 1903; and their third son, Floyd, born 7 April 1906. Eva was twenty-seven years old.

The winters in Magrath were harsh and unforgiving. The blizzards always came directly from the North. In one storm, the cattle from a neighboring ranch huddled near Melvin’s haystack for protection, and by the end of the storm they had devoured the entire stack in one night. It could be so cold, Melvin’s son Bert recalls, “I have seen cattle freeze to death standing up.”[100]

Then, as Eva described it, they had “a streak of good luck.”[101] Melvin was appointed the “town Marshal.” This provided security and a small but steady income for the family. “We moved out of the shack, uptown to be with the populace,” Bert wrote.[102] It was the beginning of a new era for their family. They built a one-room home on Second Street East, one block north of the Fletcher’s home on the corner and across the street from a steep drop to Pot Hole Creek.[103] “Two rooms were [later] added to their little home and we were happy.”[104] They were stable and growing as four more boys joined the family: Mervin “J” was born 21 April 1909; Joseph arrived 20 February 1911; Norris, 9 March 1913; and Douglas, 12 July 1918.[105]

Eva had just given birth to Mervin and was in fact still in bed with him when his older brother Parley caught scarlet fever. Today this infection would be easily treated with antibiotics. In 1909, it was especially deadly for children. “He took fits for six days. They would wrap him in hot sheets; that would settle him down . . . [but Eva] was in bed with Mervin only a few days old.” Parley was eight and suffering. Bert was twelve; Lottie, six; and Floyd, only three; and all waited helplessly. Parley called to his mother over and over for days, “Mama, Mama.” Melvin never left his son’s side. Eva could hear him, but the doctor would not allow her out of bed. New mothers were not allowed out of bed for days after birth in those days. “We thought if we got out of bed or bathed we would surely die.” Eva remained in her bed even when Parley passed away and his body was taken to the church for preparation, services, and burial. “Sister [Allie Rogers] Jensen stayed with me and held my hands as we prayed. I was surely blessed and was as calm as could be. I was thankful he [Parley] was released of his suffering.”[106]

Notes

[1] See Eugene E. Campbell, “The Mormon Gold Mining Mission of 1849,” BYU Studies nos. 1–2 (Autumn 1959–Winter 1969): 19–31. Also Ann M. Buttler and Kenneth L. Holmes, Covered Wagon Women, vol. 1, Diaries and Letters from the Western Trails, 1840–1849 (Lincoln: Bison Press, University of Nebraska, 1995).

[2] James Henry Martineau, for example, was on his way to the California gold fields when he veered south from the Oregon Trail to see the Mormons. He ended up settling in Utah. See Donald G. Godfrey and Rebecca S. Martineau-McCarty, An Uncommon Common Pioneer: The Journals of James Henry Martineau, 1828–1918 (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2008).

[3] “Brief History of Melvin Godfrey,” Godfrey Family Papers, 3.

[4] Josiah was Melvin’s older brother, born 1874. “Brief History of Melvin Godfrey,” 4.

[5] “Brief History of Melvin Godfrey,” 4.

[6] LDS scriptures promoting education include D&C 93:53 and 88:78–79.

[7] Woodfield, A History of North Ogden: Beginnings to 1985 (Ogden, UT: Empire Printing, 1986), 65.

[8] Woodfield, History of North Ogden, 43–47.

[9] See John C. Moffitt, The History of Education in Utah (Salt Lake City: John Clifton Moffitt, 1946).

[10] “Brief History of Melvin Godfrey,” 4.

[11] Schoolmaster denotes the male gender. This Gibson would appear to be the same person who would later write a Joseph Godfrey history. See Floyd J. Woodfield, A History of North Ogden: Beginnings to 1985 (Ogden, UT: Empire Printing, 1986), 47, 51. Also Richard C. Roberts and Richard W. Sadler, A History of Weber County (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1997), 90. Gibson was also one of the Probate Appraisers in 1898 when Joseph’s estate went to the Second District Court, Weber County, Utah. No. 693, Weber Country Second District Court Probate Case Files, Utah State Archives.

[12]“Brief History of Melvin Godfrey,” 4.

[13] John M. Bishop was the principal of the North Ogden Schools from 1892 to 1893 and again from 1894 to 1895. Woodfield, A History of North Ogden, 51–53. Greenwell and Kump note that the bishop and his wife were both teachers. See Greenwell and Kump, Our North Ogden Pioneers, 40.

[14] Jane West’s name appears in the records as Josie, Janie, and Jane. Jane is correct. See Greenwell and Kump, Our North Ogden Pioneers, 69, 150, 205, 240.

[15] “Brief History of Melvin Godfrey,” 5; also Greenwell and Kump, Our North Ogden Pioneers, 240.

[16] Her boarding in Joseph’s home could have provided extra income for the family and covered tuition for the children.

[17] For the broad effects of the Edmunds and Edmunds-Tucker Act, see Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 358–61, 376–79.

[18]“The Promontory” is a mountain in Park Valley at the northern end of the Promontory Mountain Range. Frederick M. Huchel, A History of Box Elder County (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1999), 363. It should not be confused with Promontory Point, which is at the south end of the Promontory Mountain Range extending down into the Great Salt Lake or Promontory, Utah, which was a railroad town near the point of the railways meeting, nor should it be confused with the Promontory Summit, where the first transcontinental railroad actually met 10 May 1869.

[19] Huchel, History of Box Elder County, 363–64. Also, it is worth noting that Joseph Godfrey and Moroni Coleman were among the first landowners of Park Valley, Utah. Dryland farming and abundant springs made it ideal for summer grazing. Without much rainfall, settlers did not stay long.

[20] Huchel, History of Box Elder County, 363.

[21] “Brief History of Melvin Godfrey,” 5.

[22] “Brief History of Melvin Godfrey,” 5.

[23] Rebaptism was not required of the Church, but it was practiced by many Saints between 1836 and 1897, before it was halted. It was part of the Mormon Reformation. See “Rebaptism,” H. Dean Garrett and Paul H. Peterson, “Reformation (LDS) of 1856–1857,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 3:1194, 1197–98. See also other rebaptisms of family in “Sketch of the Life of Richard Jones, Jr.,” Floyd Godfrey Files, Cardston, Alberta, 2. Also, Edna B. Robertson [granddaughter], “Personal History: Richard Jones,” Godfrey Family Papers.

[24] “Brief History of Melvin Godfrey,” 3, 5.

[25] Greenwell and Kump, Our North Ogden Pioneers, 301–2.

[26] “Brief History of Melvin Godfrey,” 5.

[27] As a child, Melvin was blessed by his father 5 March 1878 and baptized by Newman Henry Barker 18 October 1888. See Joseph Godfrey North Ogden Ward History, 110–11. B. F. Blaylock Ward Historian, Genealogical Library, North Ogden Ward Records.

[28] Book A, No. 1079, Godfrey Family Papers, 94. John R. Winder was second counselor to the presiding bishop of the Church, founder of the Winder Dairies in Salt Lake City, Sillitoe, A History of Salt Lake Country, 85. Riter was Orson Pratt’s missionary companion in Hungary, Douglas F. Tobler, “Europe, the Church In,” in Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 2:471. George Romney was a Salt Lake City bishop and business man. Noble Warrum, Utah Since Statehood: Historical and Biographical (Salt Lake City: S. J. Clark Publishing, 1919): 2:46–50. Also, Joseph Godfrey, North Ogden Ward History, 111.

[29] “Brief History of Melvin Godfrey,” 6.

[30] Greenwell and Kump, Our North Ogden Pioneers, 300.

[31] Robertson, “Personal History: Richard Jones,” 2–3, in Godfrey Family Papers.

[32] Greenwell and Kump, Our North Ogden Pioneers, 301.

[33] Conway B. Soone, Ships, Saints, and Mariners (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1987), 9–10. George Q. Cannon, Millennial Star (Liverpool: George Q. Cannon, 1863), 395.

[34] Soone, Ships, Saints, and Mariners, 9–10.

[35] It is reported that Richard Jones earned thirty pounds per month, which translates into $150 ($3,995). See Robertson, “Personal History: Richard Jones,” 3; also Greenwell and Kump, Our North Ogden Pioneers, 300–302. This seems out of place. However, no additional information was available at this writing. Comparing this income to Joseph Godfrey’s work evokes the question of the amount of Joseph’s wealth before it was tossed overboard in a Quebec harbor.

[36] For a personalized description of the Amazon, see the family records of LaVern Contrell, North Ogden, Museum North Ogden, Utah. Contrell is the great-granddaughter of Richard Jones.

[37]“Diary of John Watts Berrett” 4 June 1863 to 18 July 1863, FamilySearch, Mormon Immigration Index—Personal Accounts, http://

[38]“Sketch of the Life of Richard Jones, Jr.,” Godfrey Family Papers, 1–2. Note in this sketch that Jones records his “rebaptism” and that of his wife Naomi in November 1864. Also, Robertson, “Personal History: Richard Jones,” 3–5. See Thomas E. Ricks Company (1863), Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel, https://

[39] Robertson, “Personal History: Richard Jones,” 5.

[40] Greenwell and Kump, Our North Ogden Pioneers, 302.

[41] Floyd and Clarice Godfrey, “Book of Remembrance,” Richard Jones family group sheet, Godfrey Family Papers.

[42] His first wife had moved out of the house and was ill. She lived in town to be closer to the Church and to better care, but she remained a strong part of the family. Robertson, “Personal History: Richard Jones,” 8. Also “Richard Jones” (life story of Jones from the LaVern Contrell Family History), 8.

[43]“The Life of Eva Godfrey,” Godfrey Family Papers, 9.

[44] Robertson, “Personal History: Richard Jones,” 9. See also Greenwell and Kump, Our North Ogden Pioneers, 302.

[45]“The Life of Eva Godfrey,” 9.

[46] Richard and Elizabeth Jones family group sheet, prepared by Clarice Card Godfrey, Godfrey Family Papers. Eva Jones wrote she was “four” when her mother died—she was actually three. Eva was born 25 May 1878, and her mother, Elizabeth Wickham Jones, died 21 October 1881. “Eva Jones Godfrey, A Life Sketch,” 21 January 1962, Godfrey Family Papers, 1.

[47]“The Life of Eva Godfrey,” 8–9.

[48] Robertson, “Personal History: Richard Jones,” 7.

[49]“A Life Sketch of Eva Jones Godfrey,” 1962, 1.

[50]“A Life Sketch of Eva Jones Godfrey,” 1962, 1.

[51]“A Life Sketch of Eva Jones Godfrey,” 1962, 2; 1.

[52]“A Life Sketch of Eva Jones Godfrey,” 1962, 1.

[53] Woodfield, A History of North Ogden, 349.

[54]“A Life Sketch of Eva Jones Godfrey,” 1962, 1–2.

[55]“A Life Sketch of Eva Jones Godfrey,” 1962, 2, 8.

[56] “Brief History of Melvin Godfrey,” 6.

[57] Probate courts administer the assets of a decedent, provided no last will or trust exists.

[58] See “Probate and Guardian Notices, Estate of Joseph Godfrey, deceased,” Standard Examiner (Ogden), 25 January 1898, 7 through 16 March 1899.

[59] No. 693, 22 January 1898, Weber Country Second District Court Probate Case Files. The name J. H. Lindsay does not appear in either of the North Ogden histories or the histories of Weber or Box Elder County.

[60] Weber Country Second District Court Probate Case Files, No. 693, 26 November 1898.

[61] Weber Country Second District Court Probate Case Files, No. 693, 21 March 1899.

[62] “Brief History of Melvin Godfrey,” 6. Also, “A Life Sketch of Eva Jones Godfrey,” 1962, 2. While only two brothers are reflected in Melvin’s writing, there were three brothers who all eventually went north, Melvin, Josiah, and Jeremiah.

[63] Ted J. Warner, “California, Pioneer Settlements In,” in Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 1:246–47.

[64] Leonard J. Arrington, History of Idaho, vol. 1 (Moscow, ID: University of Idaho Press, 1995), 273.

[65]“A Life Sketch of Eva Jones Godfrey,” 1962, 3.

[66]“A Life Sketch of Eva Jones Godfrey,” 1962, 3.

[67] See “The Coleman Reeves Price Godfrey Meacham Relationships” chart, Coleman Family Papers.

[68] Coleman Family Papers, 175–81.

[69] Coleman Family Papers, 175–77.

[70] Ted J. Warner, “Wyoming, Pioneer Settlements In,” in Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 4:1598–99.

[71] “Brief History of Melvin Godfrey,” 6.

[72]“A Life Sketch of Eva Jones Godfrey,” 1962, 3–4.

[73] The factory cloth was likely a type of burlap. Eva records the dimensions of the cabin as 12 x 14. “A Life Sketch of Eva Jones Godfrey,” 1962, 4. See Kathleen Godfrey Watts, “Life of Bertrand Richard Godfrey,” 3 February 1980, Godfrey Family Papers, 1.

[74]“A Life Sketch of Eva Jones Godfrey,” 1962, 2. The 1962 story indicates five cows; the 1960 version says four.

[75]“A Life Sketch of Eva Jones Godfrey,” 1962, 4.

[76] Melvin Godfrey, “Brief History of Melvin Godfrey,” 7.

[77] Melvin Godfrey Family Group Sheet. Genealogical data comes from the records of Floyd and Clarice Godfrey, Godfrey Family Papers. The information is also available on FamilySearch.org, although this is not always a consistent source.

[78] Melvin gives this exact date for the beginning of the move. See “Brief History of Melvin Godfrey,” 7. Eva indicated it was fall. See “A Life Sketch of Eva Jones Godfrey,” 1962, 4.

[79] George W. Hilton, American Narrow Gauge Railroads (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990), 436–37.

[80] Mervin Godfrey, oral history, interview by Floyd Godfrey, 25 March 1982, Godfrey Family Papers, 1.

[81] Mervin Godfrey, oral history, 1.

[82] The Coleman Family Papers, 175–76.

[83] Howard Palmer, “Polygamy and Progress: The Reaction to Mormons in Canada, 1887–1923,” in edited by Brigham Y. Card, Hebert C. Northcott, John E. Forster, Howard Palmer, and George K. Jarvis, The Mormon Presence in Canada, (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1990), 118–19.

[84] See C. O. Card, “Letter to the Editor,” Deseret News, 16 April 1898, 6.

[85] For descriptions of the time see. C. M. MacInnes, In the Shadow of the Rockies (London: Rivingtons, 1930), 299–315.

[86] George W. Hildon, American Narrow Gauge Rail Roads (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990), 436–37.

[87]“A Life Sketch of Eva Jones Godfrey,” 1962, 4.

[88]“A Life Sketch of Eva Jones Godfrey,” 1962, 5.

[89]“Magrath, The Garden City of Southern Alberta,” Deseret News, 14 December 1907, 51. Also “Early Settlers,” Immigration Builders, 90–92.

[90] Gary Harker and Kathy Bly, Power of a Dream (Magrath: Keyline Communications, 1999), 29.

[91] For a map of the Galt land, see Harker and Bly, Power of the Dream, 12.

[92] Harker and Bly, Power of the Dream, 59.

[93] See “Brief History of Melvin Godfrey,” 6–7.

[94]“A Life Sketch of Eva Jones Godfrey,” 1962, 5. Also, “Life of Bertrand Richard Godfrey,” 1–2.

[95]“Life of Bertrand Richard Godfrey,” 1–2.

[96] This is likely David H. Bingham, who arrived in Magrath about the same time as Melvin and Eva. See Irrigation Builders, 414–16.

[97] Eva writes that Brother Bingham brought the coal. Bert remembers it a little differently as a child. He later wrote, “When we got up in the morning and opened up the door and pushed the snow out, there was a tub of coal.” See “Life of Bertrand Richard Godfrey,” 1.

[98] Floyd Godfrey oral history, 20 March 1982.

[99]“A Life Sketch of Eva Jones Godfrey,” 1962, 5.

[100]“Life of Bertrand Richard Godfrey,” 4.

[101]“A Life Sketch of Eva Jones Godfrey,” 1962, 6.

[102] Bert Godfrey oral history, 3 February 1980, Godfrey Family Papers.

[103] The Willard T. Fletcher family moved from Salt Lake City in 1889. See Irrigation Builders, 448–50.

[104]“A Life Sketch of Eva Jones Godfrey,” 1962, 6.

[105] Family Records of Melvin and Eva Godfrey, Floyd Godfrey Family Papers. See also, https://

[106]“A Life Sketch of Eva Jones Godfrey” (1962), 6. It was likely Allie Rogers Jensen, who stayed with Eva during these difficult hours. See Immigration Builders, 484. Interestingly, Eva’s grandson Ririe Melvin Godfrey would later marry Allie’s granddaughter Crystal Diana Robinson.