Beginnings

1875–1959

Richard O. Cowan, "Beginnings," Teaching the Word: Religious Education at Brigham Young University (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2008), 1–20.

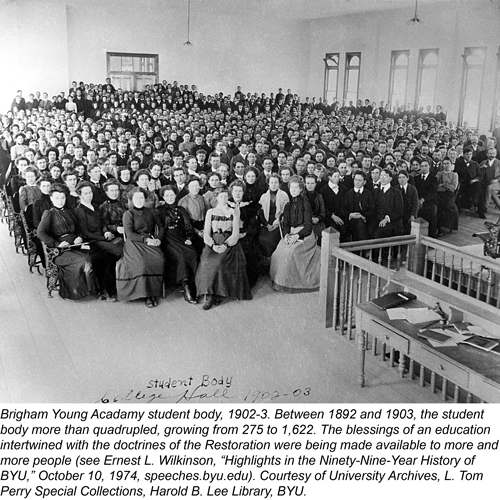

Religious Education faculty and staff members identify with those whose commission it was in ancient times “to teach the word of God among all the people” (Helaman 5:14; see also Alma 23:4; 38:15; 2 Timothy 4:2). Therefore, it has been their desire, as it was with two of Lehi’s sons, to “teach . . . the word of God with all diligence” (Jacob 1:19). Religious instruction has been a central part of Brigham Young University’s unique mission since the beginning.

Brigham Young’s Charge

President Brigham Young, founder of the university that bears his name, believed that all branches of education were important but that religious instruction needed extra emphasis. In 1852 he declared, “There are a great many branches of education. . . . But our favourite study is that branch which particularly belongs to the Elders of Israel—namely, theology. Every Elder should become a profound theologian—should understand this branch better than all the world.”[1]

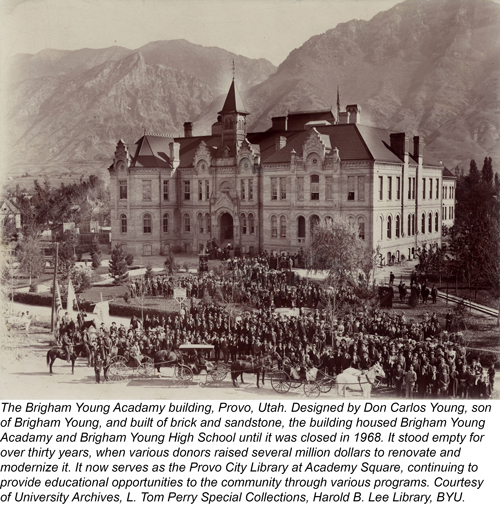

Specifically, Brigham Young Academy’s 1875 deed of trust directed that “all pupils shall be instructed in reading, penmanship, orthography, grammar, geography, and mathematics, together with such other branches as are usually taught in an academy of learning; and the Old and New Testaments, the Book of Mormon and the Book of Doctrine and Covenants shall be read and their doctrines inculcated in the Academy.”[2]

The next year, when Karl G. Maeser was sent to Provo to head the school, President Young instructed him: “Brother Maeser, I want you to remember that you ought not to teach even the alphabet or the multiplication tables, without the spirit of God. That is all. God bless you. Good-bye.”[3]

The influence of President Young’s philosophy has continued as a vital force in the twentieth century. In 1940 the Church Board of Education declared that its educational institutions and activities were maintained for three major reasons. First was “to provide the youth of Zion with religious training such as cannot be obtained in public schools; to teach the doctrines of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; to help establish within the students the testimony of the truth of the divine work established through the instrumentality of Joseph Smith, the Prophet; and thus to fit them for useful life in the Church, as intelligent, faithful, active Latter-day Saints.”[4]

Consistent with this direction, BYU’s 1981 mission statement affirmed that the university was to “assist individuals in their quest for perfection and eternal life.” Similarly, “spiritually strengthening” was listed as the first among the “Aims of a BYU Education,” adopted in 1995.

Early Religious Curriculum

From the beginning, the religious character of the curriculum was apparent. In 1879, James E. Talmage, who that year became a teacher at the academy, one month before his seventeenth birthday, reminded his class: “All our conduct in this academy, of teachers as well as students, all our discipline, all our studies are conducted according to the spirit of the living God.”[5]

During the 1880s, there were daily religion classes and devotionals. Furthermore, President John Taylor affirmed, all other subjects were to be taught in such a way that faith in the gospel would not be undermined. “It is this feature of teaching the principles of our religion, and embodying all other studies in them, which constitute one of the chief excellencies of the system of education at the B.Y. Academy.”[6]

During the early years of the twentieth century, however, there was increasing tension between traditional beliefs and new scientific ideas. Unfortunately, an investigation in 1911 found that three BYU faculty members employed the “higher criticism” of the Bible and questioned the historicity of certain events of the Restoration. As a result, the Board of Trustees recommended their dismissal. In the wake of this divisive controversy, President Joseph F. Smith advised against teaching any concepts that could be misleading or undermine faith.[7]

The 1912–13 catalog emphasized that the courses in theology were based on the standard works, the aim being to give the students a “theoretical understanding,” as well as practical application, of gospel principles in the light of latter-day revelation “in order that students may have faith in God and develop a religious character.” The curriculum consisted of yearlong courses, each meeting four times a week, in Book of Mormon, New Testament, Old Testament, and Church history and doctrine.[8]

A decade later, the “theology” offering was expanded and substantially changed because the basic questions facing the youth were not the same as in former generations. Most of the fifty-one listed courses were in the Bible, philosophy, Christian and other world religions, and even such related areas as teaching children, hymnology, Scouting, public speaking, and recreational and dance leadership. There was only one course each in such uniquely Latter-day Saint subjects as the Book of Mormon, Church history, and Mormon theology, even though these courses were the most appealing to students.[9]

A religion major was offered from 1927 to 1935. Students who wished to prepare for working with children, youth, or adults in the auxiliary organizations of the Church were permitted to major in theology, supplementing the regular courses in that department with additional classes in education and psychology.[10]

Graduate Program Initiated

The first graduate program of any kind at BYU began in 1916, and graduate offerings in religious education came six years later in 1922. At first, graduate religion courses were offered by various colleges on campus, but they were not taught by regular faculty members and were held only during the summer. In 1922, for example, the Education Department brought Dr. Charles Edward Rugh from the University of California to teach classes on religious education and the Bible.

The 1927 program was more directly aimed at seminary principals and teachers. Elder John A. Widtsoe, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve and former president of the University of Utah, offered a course in “Current Problems,” including the “higher criticism” of the Bible and the relationship between science and religion. Adam S. Bennion, superintendent of Church schools, also offered a course in the social and ethical aspects of religion.[11]

In 1929 Joseph F. Merrill (who became a member of the Twelve two years later) became the Church commissioner of education. He was convinced that “men of strong spirituality” as well as “good scholarship” were needed in the Church’s seminaries and institutes; therefore, he organized a special religion offering during the BYU summer session in 1929. He called Sidney B. Sperry, a doctoral student in Old Testament languages and literature at the University of Chicago and former seminary teacher, to give two courses in Old Testament.[12] Merrill then asked Sperry to recommend other scholars who might be invited to come in succeeding years. During the next four summers, classes were presented on the BYU campus by world-class scholars from the University of Chicago, such as New Testament translator Edgar J. Goodspeed and Christian history professor John T. McNeill.[13] “But there was a limit to what they could contribute,” noted Elder Boyd K. Packer of the Quorum of the Twelve, because they lacked the priesthood and inspiration of the Spirit.[14]

Beginning in 1929, graduate classes in “religious education” (which that year replaced the designation “theology”), were offered during the regular school year. The first students to receive master of science degrees with majors in religious education graduated in 1930. This honor went to Victor C. Anderson and H. Alvah Fitzgerald; the latter returned a quarter of a century later as a faculty member in the College of Religious Instruction.[15]

A Distinct Religion Faculty

From the beginning until 1930, religion classes were taught entirely by BYU faculty members who accepted this assignment in addition to work in their own disciplines. The expansion of the religion curriculum, and especially the introduction of graduate courses during the 1920s, made a change in this pattern advisable. Hence, the first full-time religion teacher at BYU, Guy C. Wilson, began his work on the campus in 1930. Even though others, including Joseph B. Keeler and George H. Brimhall, had the title professor of theology, a review of their teaching load and other university assignments indicates they were not full-time teachers of religion.

Guy C. Wilson earned the bachelor of pedagogy degree from the Brigham Young Academy in 1902 and then pursued graduate studies at four schools, including the University of Chicago and Columbia University. After serving fifteen years as principal of the Juárez Academy in northern Mexico, Wilson organized the Church’s first seminary at Granite High School in Salt Lake City in 1912. He later presided over the Latter-day Saints University (also in Salt Lake City) and from 1926 to 1930 served as the supervisor of religious education for the Church Department of Education. It was from this last assignment that he came to BYU as a professor of religious education until his retirement in 1941.

To meet the need for qualified teachers of religion, Commissioner Merrill encouraged a number of promising young seminary and institute teachers to go east for advanced training. Unfortunately, lamented Elder Packer years later, “some who went never returned. And some of them who returned never came back. They had followed, they supposed, the scriptural injunction: ‘Seek learning, even by study and also by faith’ (Doctrine and Covenants 88:118). But somehow the mix had been wrong, for they had sought learning out of the best books, even by study, but with too little faith.”[16] One who both received advanced training and came back was Sidney B. Sperry, who joined the faculty on a permanent basis in 1932.

The Division of Religion

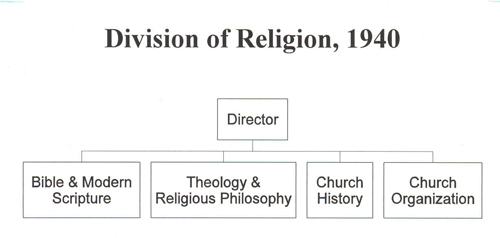

Although BYU catalogs from as early as 1902 listed religion classes under the heading “Department of Theology,” there was no official organization until 1940. In January of that year, the Board of Trustees organized the “Division of Religion” under the immediate direction of the president of the university. It was to have “co-ordinate academic standing with the schools of the University” and was to be “a general service division to all university departments in the field of religious education.” In addition to supervising “religious instruction,” the division was also responsible for “all religious activities on campus,” including devotionals, Sunday School, and the Mutual Improvement Association.

Students were required to take six quarter hours of religion each year, and the division issued certificates to those who completed thirty-six hours of religion as was being done in the institutes. Actual degrees in religion were offered only on the graduate level.[17]

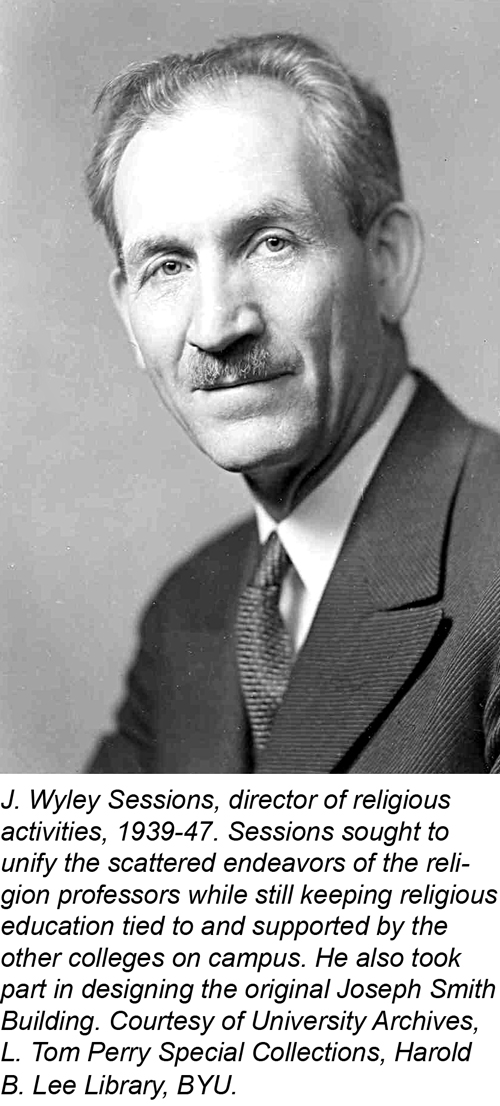

J. Wyley Sessions, who had joined the faculty as director of religious activities in 1939, assumed leadership in the new division. While working on a master’s degree at the University of Idaho, he organized the Church’s first “Institute of Religion” there in 1926.[18] He supervised the construction of an attractive building which would meet the students’ social as well as spiritual needs. He later served as Institute director in Pocatello, Idaho; Laramie, Wyoming; and Logan, Utah, traveling widely as a consultant for similar programs and buildings at other western campuses.

When he came to BYU, Sessions found teachers of religion scattered all over campus. Without central direction, the professors taught as they pleased. His goal was to form a curriculum that would provide the strongest possible religion program. He did not see the teaching of religion as being “set off or apart” but believed the Division of Religion should be “tied to, affiliated with, and supported by all the colleges of the University.”[19] Within the division, there were four subject-area departments, each headed by a chairman.

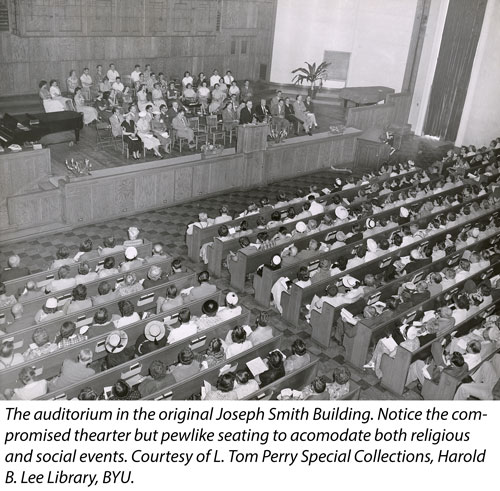

The Joseph Smith Building

As religious activities and instruction expanded, the need for an adequate facility to house them became increasingly apparent. BYU president Franklin S. Harris, for example, lamented that only one-third of the student body could be accommodated in College Hall on lower campus where the regular devotional assemblies were held: “Thus the majority were denied much of the very things that make Brigham Young University unique. Students coming from far away primarily to secure the spiritual advantages of the Institution were able to obtain these advantages only in part.”[20] The General Authorities were particularly concerned with the students’ spiritual welfare. President Heber J. Grant, for example, felt that the next building built on the campus should be a chapel and that no other construction should take place there until the religious character of the school was well established.[21]

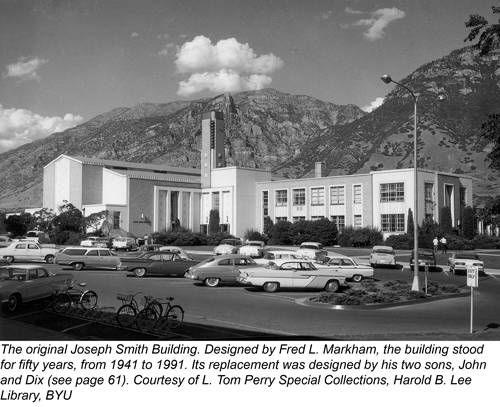

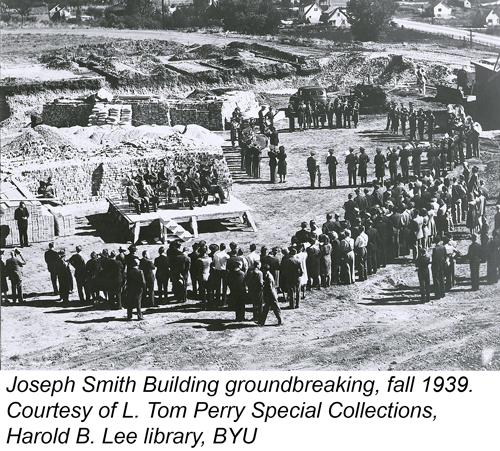

Church commissioner of education Franklin L. West had assigned J. Wyley Sessions, who was still consulting on new institute buildings, to design an institute building to serve thirty-five hundred to four thousand students. Sessions did not know where the large new institute building was to be built but thought it was for the University of Utah; it was not until he came to BYU in 1939 that he learned the structure would be for BYU.[22] Fred L. Markham of Provo was appointed architect, and a faculty committee supervised the project. Construction began in the fall of 1939 on what would become the original Joseph Smith Building.

The General Authorities decided to make the construction of this building a Church welfare project. The bishops in the twelve cooperating stakes were responsible for procuring the required workmen. When this supply of labor from the wards was insufficient, BYU students stepped in to help, contributing many days. On “Y Day” in 1941, all the male students participated in constructing the walks around the building. Provo businesses contributed three thousand dollars. Funds from a special fast day were used to buy produce to pay the workers.[23]

The building was dedicated on Founders’ Day, October 16, 1941. President Harris reminded the assembled congregation of the sacrifices made by the many individuals who had assisted in the construction and given “thousands of voluntary days of work.”[24] President David O. McKay, Second Counselor in the First Presidency, affirmed that “it is fitting that there should be on this campus an edifice bearing the name of the Prophet Joseph Smith. . . . Without revelation given to Joseph Smith there would be no Brigham Young University. In all classes here at this school there should be connoted [the] great truth: that God lives, that Jesus is the Christ, and that Joseph Smith was the divinely inspired Prophet of the Lord, chosen to establish Christ’s Church on earth in this latter day.” He described the new edifice as “a place of worship, a temple of learning, and a place of spiritual communion,” which stood for the “complete education of youth—the truest and the best in life.”[25]

At the time of the new building’s dedication, university officials anticipated that it would have a significant impact on the school’s programs: “The need of this building and the contributions it will make to the future of Brigham Young University and to the entire Church cannot be over-estimated.”[26]

In addition to providing the badly needed auditorium and classrooms, the new Joseph Smith Building included other facilities that accommodated a variety of campus activities. Behind the auditorium was a large, beautiful ballroom that doubled as an overflow area. The campus’s main cafeteria was located in the basement of the building’s south wing. A “banquet hall” occupied the building’s southeast corner. A special meal service was also offered in the adjoining “Club Room” at noon for members of the faculty and others—a precursor to the service later offered in the Sky Room. Beginning in 1952, major dramatic productions, including many of Shakespeare’s plays, were presented on the JSB auditorium’s stage.

Postwar Growth

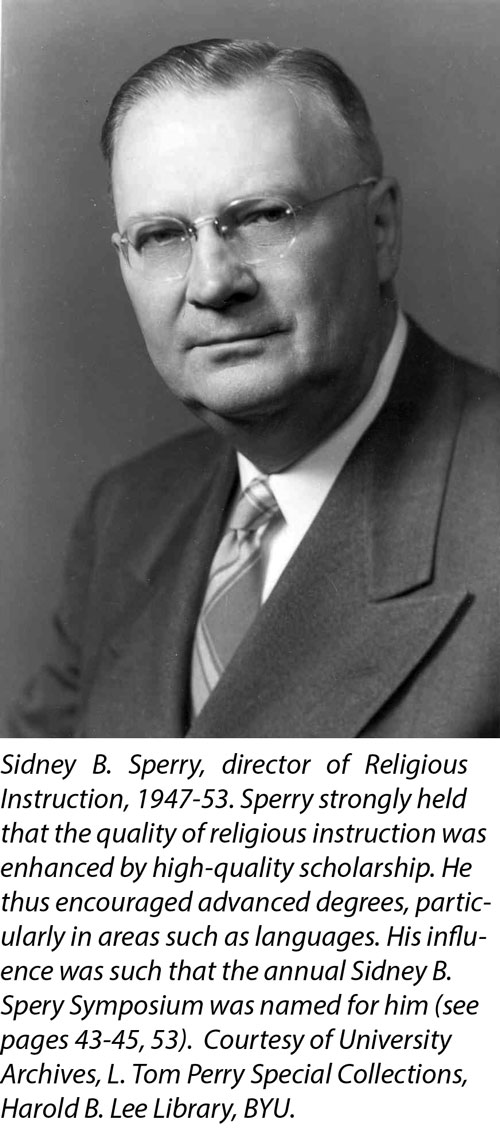

From 1939 until his retirement in 1947, Sessions served as director of Religious Activity, and Hugh B. Brown served briefly in the same office. In 1949 the office was discontinued because responsibility for social and related activities had been shifted from the Division of Religion to the recently created Church branches on campus (these branches would be organized into the first BYU stake on January 8, 1956). In 1947 Sidney B. Sperry was called to fill a new post, director of Religious Instruction, clearly in charge of only academic work.

Even though Sperry received his bachelor’s degree in chemistry and began teaching high school math and science, in 1922 he made the decision to become a seminary teacher. Following his doctoral training as one of the young men who went east for graduate education, in 1932 he became BYU’s second full-time religion teacher. Sperry’s contributions were not limited to the BYU campus. His pioneering lecture series in Utah, Idaho, Nevada, California, Washington, and Alberta anticipated the far-flung “Education Week” and Know Your Religion lectures of later years. His dozen books and countless articles also served to spread his influence. He even had the distinction of leading the first BYU Travel Study tour in the Holy Land in 1953.

As Dr. Sperry assumed his role as director of Religious Instruction, he had “great hopes for the Division of Religion; he had the desire and vision that some day it would become spiritually and scholastically the greatest in the world.”[27] To this end Sperry sought teachers who had both a thorough command of their subjects and a firm testimony of the gospel. Under Dr. Sperry’s leadership, the religion faculty experienced a dramatic increase from only four in 1947 to twenty-nine a decade later. Following the example of Commissioner Merrill twenty years earlier, Dr. Sperry encouraged promising potential teachers to seek further training in the leading universities of the country. David H. Yarn, a future dean of religion, paid tribute to Sperry’s leadership and personal example and affirmed that “to him more than any other person goes credit for the confidence the Brethren have established in this college for both individual and collective effort in preparation of manuals, handbooks, teacher supplements, etc.”[28]

The religion curriculum also felt the impact of Dr. Sperry’s influence. Under his direction, the number of undergraduate courses in the modern scriptures increased from three to ten. Similarly, by 1958, graduate courses expanded from six to ninety-two, including forty-two in languages. The Bible courses increased from one to twenty-one during this period, and where there had been no graduate courses on Latter-day Saint scriptures or Church history in 1938, the offerings in these areas reached six and ten classes, respectively.

As early as 1929 the catalog had referred to a master’s degree with a major in religious education. In 1958 the Division of Religion began offering the PhD in scripture and Church history and also launched the new master of religious education (MRE) degree. Five years later the doctor of religious education (DRE) degree was added. Unlike the PhD, the DRE was a “service degree” designed especially to meet the needs of seminary and institute teachers.[29] In 1963, Melvin S. Tagg was the first to earn a PhD in religion.[30] Over the years more than two hundred theses and dissertations were written on religious topics. “There is a definite need in the Church for scholarly research,” Sperry explained. “I hope to develop young scholars, especially those with a flair for languages.” He hoped to make it possible to pursue advanced degrees in the atmosphere of their own religion and not have to travel great distances to do so.[31]

In the fall of 1953 the responsibilities of leadership separated. The major administrative responsibility passed to B. West Belnap, who became director of the Undergraduate Division of Religion. Sperry was appointed to the new office of director of Graduate Studies in Religion.

Notes

[1] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86), 6:317.

[2] Deed of Trust, quoted in John P. Fugal, “University-wide Religious Objectives: Their History and Implementation at Brigham Young University” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1967), 36.

[3] Reinhard Maeser, Karl G. Maeser: A Biography by His Son (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, 1928), 79, as quoted in Fugal, “Religious Objectives,” 36.

[4] Quoted in Fugal, “Religious Objectives,” 26.

[5] “Theological References,” October 13, 1879, book 2, p. 9; University Archives.

[6] Letter to stake presidents and bishops, Inquirer, June 10, 1887.

[7] Ernest L. Wilkinson and W. Cleon Skousen, Brigham Young University: A School of Destiny (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1976), 200–212.

[8] Annual Catalogue, 1912–13, 82.

[9] Ernest L. Wilkinson, ed., Brigham Young University: The First One Hundred Years (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1965), 2:289–90.

[10] Annual Catalogue, 1927–28, 187; see corresponding entries in the following eight issues.

[11] Wilkinson, The First One Hundred Years, 2:287.

[12] Sidney B. Sperry, “History of a Graduate Religion at BYU,” unpublished paper delivered November 15, 1969, 3.

[13] Sperry, “Graduate Religion,” 3–4.

[14] Boyd K. Packer, “Seek Learning Even by Study and Also by Faith,” in Religious Education Foundational Readings (n.p.: Religious Education, Brigham Young University, June 2005), 28.

[15] 54th Annual Commencement of the Brigham Young University, June 4, 1930.

[16] Packer, “Seek Learning,” 28.

[17] Executive Committee of the BYU Board of Trustees, minutes, January 5, 1940.

[18] A. Gary Anderson, “A Historical Survey of the Full-time Institutes of Religion” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1968), 44.

[19] J. Wyley Sessions interview, June 29, 1965.

[20] Souvenir of the Dedication of the Joseph Smith Building, Brigham Young University Quarterly 38 (November 1, 1941): 1.

[21] Fred L. Markham, interview by M. Ephraim Hatch, November 1, 1973, in “History of the Brigham Young University Campus and Department of Physical Plant,” manuscript, 4:25, University Archives.

[22] Sessions interview.

[23] Souvenir, 5.

[24] Founders’ Day Report, October 16, 1941, manuscript, University Archives.

[25] Founders’ Day Report, October 16, 1941.

[26] Souvenir, 6–7.

[27] Sperry, “A Graduate Religion,” 10.

[28] Yarn, “A Tribute to Sperry,” 3–4.

[29] Catalog, 1958–59, 365.

[30] College of Religious Instruction graduate faculty meeting minutes, January 3, 1963.

[31] 88th Annual Commencement Convocation, 24.