Scott C. Esplin, “The Salt Lake Tabernacle: A Witness to the Growth of God's Kingdom,” in Salt Lake City: The Place Which God Prepared, ed. Scott C. Esplin and Kenneth L. Alford (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, Salt Lake City, 2011), 69–96.

Scott C. Esplin is an assistant professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University.

Temple Square, including the Salt Lake Tabernacle and Assembly Hall, as the Salt Lake Temple nears completion (ca. 1891). (© Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

Temple Square, including the Salt Lake Tabernacle and Assembly Hall, as the Salt Lake Temple nears completion (ca. 1891). (© Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

“In great deeds something abides,” reminisced Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, a famed Civil War colonel. “On great fields something stays. Forms change and pass; bodies disappear, but spirits linger, to consecrate ground for the vision-place of souls. And reverent men and women from afar, and generations that know us not and that we know not of, heart-drawn to see where and by whom great things were suffered and done for them, shall come to this deathless field to ponder and dream; And lo! the shadow of a mighty presence shall wrap them in its bosom, and the power of the vision pass into their souls.” [1] For Latter-day Saints, the historic Salt Lake Tabernacle has become one of those sacred sites—a consecrated hall where “something abides” and “spirits linger” and where modern visitors are wrapped in “the shadow of a mighty presence” while visions of the Restoration “pass into their souls.” President Gordon B. Hinckley summarized the influence the Tabernacle has had on the Church: “The Spirit of the Lord has been in this structure. It is sacred unto us.” [2]

With the construction of larger and more modern conference halls, the Salt Lake Tabernacle stands today as a silent witness to its pioneer past. Having undergone significant transformations throughout its life, the building serves not only as a monument to pioneer greatness but also as an example of changes in the Church’s history. Its sacred heritage mimics the faith’s own transformation into a recognizable worldwide church. Born of necessity, the Tabernacle began as a functional assembly hall for pre-railroad Utah in the 1860s. As the Church grew, the Tabernacle changed from a meeting place into a missionary messenger, a means for disseminating the faith. Improved technology, coupled with the increasing popularity of the building’s famed choir, brought the structure into a new era. However, the recognition of the choir and of the Church eventually caused the faith to outgrow the building, leaving the structure as a memorial to pioneer ingenuity and resourcefulness. Throughout these transformations, the Salt Lake Tabernacle has hosted within its walls some of the most significant events associated with the growth of the Church and the establishment of Zion. It stands as a reminder of this past and as a witness that the Church’s future remains connected to its prophetic founding. [3]

The Tabernacle as Functional Assembly Hall

The Salt Lake Tabernacle began as one of a series of options Church leadership explored to answer a problem that continually plagued early Mormonism: how to accommodate all who wanted to hear the prophet’s voice. “It used to be in the days of the Prophet Joseph, a kind of common adage that Mormonism flourished best out of doors,” noted Elder George A. Smith. [4] Indeed, throughout Joseph Smith’s life, the Church struggled to provide adequate meeting space for its growing membership. Beginning with the Kirtland Temple, the first formally erected meetinghouse, the Church and its leaders failed to accommodate all who wanted to worship. “I felt to regret that any of my brethren and sisters should be deprived of the meeting,” the Prophet Joseph Smith remarked, when more people than could fit crowded in to witness the Kirtland Temple dedication on March 27, 1836. Although those who did not fit in the temple were sent to a nearby schoolhouse and promised a second dedicatory service, many were still left out. [5] Later, in Nauvoo, the challenge to seat the Saints continued, with the Prophet and other leaders regularly addressing congregations outdoors because of the crowds. A canvas tabernacle requiring more than four thousand yards of cloth was planned for the lot directly west of the Nauvoo Temple, but the project was scrapped and the materials were used to outfit westbound wagons following the Prophet’s death. [6]

In Salt Lake City, the problem of accommodating all who wished to gather for meetings persisted. As early as one week after entering the valley, leaders sought to protect Saints from the harsh elements by building an open-air bowery, a pavilion covered by evergreen branches. As many as five of these boweries stood for nearly two decades in and around Temple Square; the largest was built in the early 1860s and may have held more than eight thousand people. [7] While good for shade, these structures were useless against harsh winters. As early as 1852, a more permanent structure (known today as the “Old Tabernacle”) was built along the southwest corner of Temple Square. Able to accommodate about 2,200 people, the hastily built structure served as a temporary measure until something larger and more lasting could be erected. Church leaders hoped the Salt Lake Tabernacle would solve this problem permanently when they announced plans for its construction at April conference in 1863.

Church leaders optimistically hoped the Tabernacle would be “enclosed [the first] fall, and when finished . . . seat nearly 9000 persons.” The structure missed both estimates. [8] As construction stretched over more than four years, Church leaders began to realize that the building would never accomplish their goal of seating all the Saints. In the conference preceding its dedication, Elder George A. Smith predicted, “I expect that by the time our great Tabernacle is finished, we shall begin to complain that it is too small, for we have never had a building sufficiently large and convenient to accommodate our congregations at Conference times.” [9] President Brigham Young similarly downplayed Saints’ expectations:

We calculate by next October, when the brethren and sisters come together, to have room for all. And if there is not room under the roof, the doors are placed in such a way that the people can stand in the openings and hear just as well as inside. I expect, however, that by the time our building is finished we shall find that we shall want a little more room. “Mormonism” is growing, spreading abroad, swelling and increasing, and I expect it is likely that our building will not be quite large enough; but we have it so arranged, standing on piers, that we can open all the doors and preach to people outside. [10]

Elder Smith’s and President Young’s statements proved prophetic. When the building was first used the following October, the aisles and doorways were crowded, and many members were left standing outside. [11]

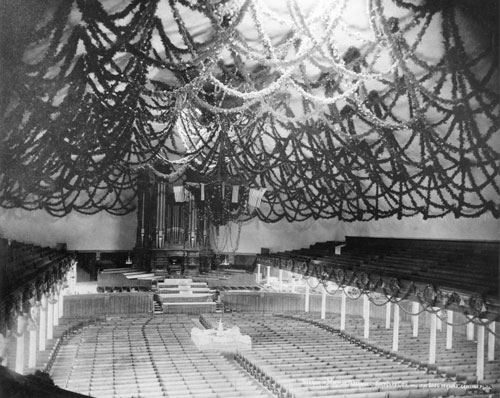

View of the interior of the Salt Lake Tabernacle, decorated with garlands and featuring a water fountain in the center. (© Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

View of the interior of the Salt Lake Tabernacle, decorated with garlands and featuring a water fountain in the center. (© Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

Resolved to increase the functionality of their new meeting hall, Church leaders took measures to enlarge the space. Just two years after the Tabernacle was completed, the Saints began adding a gallery that would significantly increase seating. Shortly before its completion in April 1870, the Deseret News remarked, “By the 5th of next month it is believed that the new gallery will be so far finished as to be ready for use by the public, and twelve thousand persons may then be comfortably seated within the walls of the spacious building. Under such circumstances it is presumed that Conference may be held in comfort, and that none who desire to attend will be under the necessity of staying away, for lack of comfortable accommodation, as has been the case on many occasions in the past.” [12]

Indeed, with the Tabernacle’s ability to accommodate large crowds, the pioneer builders next turned their attention to increasing the masses’ comfort. From 1875 until the mid-1880s, a large water fountain flanked by four statues of lions rested twelve rows from the front podium in the center of the structure. Designed to cool the occupants, it also provided some comic relief when, on one occasion, a child made use of the fountain. “It seems that at one June conference, when the Tabernacle was very warm,” LeRoi C. Snow recalled, “a family of good Saints from Hawaii was in attendance. They had entered the Tabernacle from a front side door and were attempting to make their way down the center aisle to find seats. To do so they had to detour around the fountain, for which purpose steps and a walkway were provided. One of the youngsters of the family, on coming abreast of the fountain fell a victim of temptation and eagerly dived in, and began a vigorous splashing. He was duly extricated, much to the amusement and probably the envy of the assembled Saints.” [13] Though less exciting, additional amenities including gas lighting and heating were added to the structure in 1884. [14]

As they did their best to improve the comfort and use of the building, early leaders never forgot its primary purpose as an edifice where the Saints could gather to hear the word of God. John Taylor’s dedicatory prayer, finally offered in October 1875, eight years after the building was first used, highlighted the Tabernacle’s original intent. “We, thy servants,” Taylor prayed, “dedicate and consecrate this house unto thee, and unto thy cause, as a place of worship for thy Saints, wherein thy people may assemble from time to time, to obey thy commandment to meet often together to observe thy holy Sabbath, to partake of thy holy Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper, and wherein they may associate for the purpose of prayer, praise and thanksgiving, for the transaction of business pertaining to thy Church and kingdom, and for whatsoever purpose thy people shall assemble in thy name.” Further emphasizing the hall’s primary focus, Taylor implored, “May thy holy angels and ministering spirits be in and round about this habitation, that when thy servants are called upon to stand in these sacred places, to minister unto thy people, the visions of eternity may be open to their view, and they may be filled with the spirit and inspiration of the Holy Ghost and the gift and power of God; and let all thy people who hearken to the words of thy servants drink freely at the fountain of the waters of life.” [15]

Drinking “freely at the fountain of the waters of life” encapsulates the Tabernacle’s purpose throughout much of its useful life. While it was regularly used for sacrament meetings until the 1890s and for weekly worship services into the 1920s, the building’s best-known meeting function was always hosting the Church’s general conferences. From the first conference held there in October 1867 to the last in October 1999, the Salt Lake Tabernacle served as the home of the semiannual gatherings. In fact, during that 132-year period, only five general conferences (held outside of Salt Lake due to the antipolygamy opposition of the 1880s) were ever convened outside the Tabernacle. [16]

As home to general conference for more than a century, the Tabernacle witnessed some of the Church’s most significant events, including solemn assemblies for thirteen Church presidents, the canonizing of scripture, and announcements of official Church action (for example, the cessation of plural marriage in 1890 and the extension of priesthood access to all worthy males in 1978). It also hosted unique general conference sessions, including a special testimony meeting held as the last session of the October 1942 gathering. At the height of World War II, the sacrament was administered during this meeting, and those assembled “returned home better able to cope with the dark days ahead.” [17] At the structure’s rededication in 2007, Bishop H. David Burton recalled some of these historic Tabernacle occasions: “These old walls, if they could talk, would shout, ‘We were here’” when Joseph F. Smith shared his vision of the redemption of the dead, when President Heber J. Grant inaugurated the Church welfare plan during the depth of the Depression, and when Harold B. Lee reiterated the First Presidency’s 1915 call for family home evening. [18] President Boyd K. Packer likewise remembered,

Here in 1880 the Pearl of Great Price was accepted as one of the standard works of the Church.

Here also two revelations were added to the standard works, now known as Doctrine and Covenants sections 137 and 138. . . .

Here in 1979, after years of preparation, the LDS version of the King James Bible was introduced to the Church.

The new editions of the Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price were announced to the Church here.

In 1908 in a general conference, President Joseph F. Smith read section 89 of the Doctrine and Covenants—the Word of Wisdom. . . . Then a vote to accept it as binding upon the members of the Church was unanimously passed. . . .

Here the Book of Mormon was given the subtitle “Another Testament of Jesus Christ.” [19]

In summary, as President Packer said, “Great events which shaped the destiny of the Church have occurred in this Tabernacle at Temple Square.” [20]

In addition to many unique conference occasions, the Tabernacle’s walls have also resounded with testimonies from every Church president from Brigham Young to Thomas S. Monson. During the building’s eighty-fifth anniversary in 1952, Elder Stephen L Richards reflected upon the powerful doctrinal declarations that had been delivered in the building:

Ponder for a moment, my brethren and sisters, and all who listen, the glorious and vital truths which have been proclaimed in this building—the nature and composition of the Godhead, the organization of the universe, the history and placement of man in the earth, his purpose in living, and the divine destiny set for him, the laws governing his conduct and his eligibility for exaltation in the celestial presence, the true concept of family life in the eternal progression of the race, the truth about liberty and the place of governments in the earth, the correct concept of property, its acquisition and distribution, the sure foundations for peace, brotherhood, and universal justice. All these elemental things, and many others incident thereto, have been the burden of the message of truth which has come from this building through the generations. [21]

The impact of these truths caused Richards to conclude, “I stand today in a pulpit sanctified by its history. When I recall the noble servants of our Heavenly Father who have stood here and given inspired counsel to the people, and borne testimony with such power and conviction and spirit as to electrify every soul who heard; when I contemplate the operation of the still, small voice, which has come from simple and lowly words given here, which have touched the hearts and sympathies of the people; when I think of the vast volume of precious truth which has been proclaimed from this stand, I feel very small and weak within it.” [22]

In addition to being home to the prophet’s general conference addresses, the Tabernacle has also been the site for many of their final farewells. One of the earliest funerals in the Tabernacle was held for President Heber C. Kimball on June 24, 1868, just nine months after the building opened. The first funeral for a President of the Church in Salt Lake City occurred in 1877 when Saints bid farewell to Brigham Young in the historic structure. From then until the completion of the Conference Center in 2000, funeral services for every President of the Church (except President Joseph F. Smith, whose service was private because of the 1918 flu epidemic) and numerous other prominent men and women have been held in the Tabernacle. Elder Richards said, “Within these sacred walls have the great of our community found opportunity for the expression of their noblest thoughts and convictions, and from here they have been laid to rest in the closing of their lives.” [23] Providing a place for the Saints to transact important Church business while greeting, learning from, and bidding farewell to Church leaders, the Tabernacle has served as the spiritual home of the Saints for more than a century.

The Tabernacle as Missionary Messenger

While originally built to host the Saints’ spiritual events, the Salt Lake Tabernacle, easily the largest hall in the region, quickly took on other functions. During the late nineteenth century and throughout much of the twentieth century, the Tabernacle shifted from being a meeting hall to a missionary location. The Tabernacle “has stood as a great missionary,” observed Elder Howard W. Hunter, “introducing the gospel of Jesus Christ to people all around the world—those who have entered its portals and those who have heard the message that has gone forth from here in music and the spoken word.” [24] More so than the temples, which are reserved for members, the public Tabernacle became a place of intersection for Mormons and the outside world. “The Tabernacle was where early Mormonism revealed itself to contemporaries,” historian Ronald W. Walker summarized. [25]

The Tabernacle’s earliest missionary influence was its construction and size, both of which were unique in the West. Of the visitors who toured the structure, Walker observed, “Everyone agreed that the building was big, especially for its time. Travelers to Salt Lake City used such words as ‘huge,’ ‘extraordinary,’ ‘immense,’ and a ‘monster in size’ to voice their awe. . . . [However,] admiration for the building’s engineering and size did not necessarily translate into praise for its design.” [26] After lauding the orderliness of the city itself, one eastern visitor remarked, “The far-famed tabernacle strikes one as a huge monstrosity, a tumour of bricks and mortar rising on the face of the earth. It is a perfectly plain egg-shaped building, studded with heavy entrance doors all around; there is not the slightest attempt at ornamentation of any kind; it is a mass of ugliness; the inside is vast, dreary, and strikes one with a chill, as though entering a vault.” [27] Others remarked that the building had “no more architectural character . . . than . . . a prairie dog’s hole.” [28]

Disdain for the building may have stemmed from contempt for the faith it represented, causing the Tabernacle to became “a frequent target for caricature.” [29] Some called it “the Church of the Holy Turtle,” others “half of an eggshell set upon pillars.” Additional comparisons included a “culinary serving dish, . . . Noah’s ark had it been capsized, . . . [and] balloons, bathtubs, bells, watermelons, a whale, and even mushrooms.” In one instance of extreme exaggeration, one man remarked, “For my part, I decided that, so far as my experience goes, the oval tabernacle . . . is unsurpassed, even by its neighboring preaching shanty, for oppressive ugliness among all the buildings now standing in the world.” Ronald Walker summarized, “In short, the building was a gigantic curio, something ‘strange’ and ‘unique,’ to be talked or written about because of its outlandishness. ‘We have never seen anything like it,’ said a British minister.” [30]

Visitors could often overcome their disregard for the architecture, however, if they enjoyed the experience inside. In an effort to provide culture for its residents and welcome the world, the Church transformed the Tabernacle from merely a religious assembly hall into a community gathering place. In rededicating the structure, President Gordon B. Hinckley noted that the Tabernacle has not merely served the Church in religious functions. He observed,

Through these many years, this has been a unique and wonderful place of assembly. Many men and women have spoken here, testifying of the Restoration of the gospel of Jesus Christ. From the time of Brigham Young to the present, every prophet has spoken from this pulpit. Other men and women of note have spoken, including various presidents of the United States. It has been a home for the arts and culture of this community. The Utah Symphony first used this as a place to perform. Great artistic productions have been presented here, such as the Messiah and the Tanner Gift of Music. Funeral services for men and women of prominence have been conducted here. It has truly been a centerpiece for this community through all of these many years. [31]

As a community centerpiece, the Salt Lake Tabernacle has witnessed some of the most significant civic events in Salt Lake’s history. Prominent visitors to the state have sought out the Tabernacle. Ulysses S. Grant, the first United States president to come to Utah, toured the historic tabernacle shortly before its dedication in 1875. [32] Other United States presidents who visited or spoke in the historic structure include Rutherford B. Hayes, Theodore Roosevelt, William H. Taft, Woodrow Wilson, Warren G. Harding, Herbert C. Hoover, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson. President Hayes was amazed with the building’s acoustics and the fact that he could carry on a conversation with General William T. Sherman from two hundred feet away. [33] Presidential candidates, some of whom later won election to the office, spoke from its podium, including Dwight D. Eisenhower, William Jennings Bryan, James G. Blaine, Richard M. Nixon, and Barry Goldwater. Other prominent visitors came from all over the world. They included General William Booth, Sir Arthur Sullivan, Susan B. Anthony, Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil, Queen Liliuokalani of Hawaii, actress Lillie Langtry, General Phillip Sheridan, actor Edwin Booth, Joseph Smith III, Ferdinand de Lesseps, Henry Ward Beecher, Dr. Norman Vincent Peale, and Harvard president Charles William Elliot.

In addition to prominent dignitaries, the Tabernacle has also regularly hosted the world’s great performers. While Church leaders valued music, the idea of introducing sectarian singing into the Tabernacle was met with some protests. Although some members of the Twelve disapproved of sectarian uses for the building, the world-famous operatic soprano Adeline Patti gave one of the earliest concerts held in the historic structure in February 1884. By one account, Madame Patti won President John Taylor over to the idea of a concert by praising the magnificent Tabernacle and expressing “a strong desire that she might be allowed to try her voice there.” Apparently, her appeal included “enthusiastic praise of the Mormon doctrines, and, in fact, . . . a strong wish to join the Mormon Church.” [34] The event was significant not only because of the prestige of the performer but also because it marked the first event held on a winter night in the Tabernacle. Gas lamps and pot-bellied stoves were brought in to illuminate and warm the building. Patti had a special rail line built to take her car directly to the Tabernacle itself. [35] Though Patti’s conversion is questionable, the concert was a success, with over fourteen thousand people reportedly present.

Since Patti’s visit, musicians have made the Salt Lake Tabernacle a regular stop on their North American tours. The building has hosted some of the most famous musicians of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, including Polish pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff, Austrian violinist Fritz Kreisler, and, more recently, American vocalists Frederica von Stade and Gladys Knight. [36] Deseret News music editor Harold Lundstrom observed, “At least a dozen of the world’s great artists . . . have told me that the principal reason for their accepting a concert date in Utah was so that they could include in their concert credits a ‘performance in the Salt Lake Mormon Tabernacle.’ At least four of them have said that a performance in the Tabernacle carried the prestige second only to Carnegie Hall.” [37] Like soloists, famed performing groups have also sought out the hall as a venue. Over the years, the Tabernacle has hosted the New York Philharmonic, the Pittsburgh Symphony, the Chicago Symphony, the Berlin Philharmonic, and the Vienna Philharmonic.

Though visits by these performers and groups are significant, the Tabernacle’s musical claim to fame remains its renowned namesake and chief occupant, the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. [38] In celebrating the building’s renovation in 2007, President Packer remarked, “Worthy music of all kinds has its place. And there are endless numbers of places where it can be heard. But the Tabernacle on Temple Square is different from them all.” [39] The difference may lie in the choir itself, which has become synonymous with the building. President Stephen L. Richards best summarized the relationship: “I would not venture to say whether the Tabernacle has made the choir or the choir has made the Tabernacle famous.” [40] In fact, though the adjacent Conference Center is much larger, President Gordon B. Hinckley carefully indicated that, upon completion of its renovation, the Tabernacle would remain the choir’s home. “[This building] has become known across the world as the home of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir,” he stated. “It will again be home to the Tabernacle Choir and the Orchestra on Temple Square.” [41]

In addition to musical performances, numerous other civic events have been held in the building, including “nominating conventions for political offices, a mass protest meeting over the conduct of federal appointees in the territory, a benefit concert for the Johnstown flood victims, the Western Silver Conference, President Wilford Woodruff’s 90th birthday celebration, [and] . . . a convention of Episcopalians.” [42] Prominent among these civic events have been sacred memorials of national and international import. In 1923, for example, a memorial service was held in the Tabernacle mourning the death of United States president Warren G. Harding. Coincidentally, President Harding had spoken in the Tabernacle on his visit to Utah only six short weeks earlier. More recently, the hall served as a solemn gathering place for the Church following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. As part of the National Day of Prayer and Remembrance, Church members and leaders gathered in the historic Tabernacle to sing, worship, and pray. Following the meeting, Church News editor Gerry Avant observed, “With seeming reluctance, people filed from the Tabernacle that, for the brief span of about an hour, had sheltered them as in a dome of peace and tranquility.” [43]

Many of these civic events hosted in the Tabernacle include memorable Church productions aimed at distributing the Church’s message both to its members and to the world. During the twentieth century, the Church frequently used the hall for various historical commemorations. In honor of the centennial of the Church in 1930, members participated in a pageant entitled “The Message of the Ages,” held in the building throughout the month of April. Emphasizing the restoration of the gospel, it presented a chronological summary of the history of God’s work on earth. One observer commented that this was “probably one of the most outstanding events ever held in the Tabernacle.” [44] Seventeen years later, in 1947, a similar production was held to commemorate the arrival of the pioneers in Utah and the Church’s reaching a milestone of one million members worldwide. More recently, the Tabernacle was used in Salt Lake’s celebration of the 2002 Winter Olympics and Paralympics, hosting concerts with the Tabernacle Choir and world-renowned artists throughout the games.

To accommodate its wide variety of uses and keep up with technological change, the Church has made frequent improvements to the Tabernacle. An article in the Church’s Improvement Era during the building’s centennial year summarized many of the changes: “The building has been remodeled and changed through the years as science and technology have opened new doors and avenues to improvement. The choir loft has been rebuilt half a dozen times; new electrical and heating systems have been installed; broadcast facilities have been added; the balcony stairs have been remodeled to allow for outside rather than inside access; and many other improvements have been made.” [45]

Some of the earliest technological advancements brought to the building involved lighting and heat. Though the numerous doors and windows provided some natural light, artificial lighting soon became a necessity. A similar need to heat the hall was quickly recognized, as functionality was hampered during the cold winter months. In 1884, a heating and lighting system was installed. Three hundred gas-filled jets flooded the hall with light. Gradually, the gas was replaced with electricity, and the Tabernacle became one of the first structures in Utah to have electric lighting. [46] Later lighting changes have been driven by the needs of the various productions held in the structure.

While utility improvements have increased the functionality of the Tabernacle, safety improvements have increased its longevity. The Improvement Era remembered some famous near-disasters over the life of the building:

The days of the Tabernacle have not been without excitement. During a Fourth of July celebration in 1887, fireworks ignited the roof, but, according to Church historical records, ‘the flames were promptly put out by the fire brigade before doing much damage.’ . . .

In 1933 water pipes froze and burst one bitterly cold night, causing extensive damage to some of the walls and carpets. Six inches of water accumulated in the basement under the organ, but the organ itself was not touched.

On a quiet January Sunday in 1938, four men were found spraying gasoline on the building. During the ensuing scuffle, one of them was severely burned. [47]

These and other potential disasters prompted safety improvements in the structure. A tin roof replaced the original four hundred thousand wooden shingles at the turn of the century, and an aluminum roof replaced the tin in 1947. [48] A sprinkler system was added to the interior in 1930. To protect the Tabernacle against earthquakes, the entire roof was reinforced with angle iron in 1942. [49]

In addition to improving safety, Church officials have sought to increase the comfort and serviceability of the Tabernacle. For example, in 1951 a quiet room was added for members with young families. Later, in 1968, a full basement was dug underneath the building to house mechanical equipment, radio and television facilities, offices, and storage. Especially important was the addition of dressing rooms and storage facilities for the Mormon Tabernacle Choir.

In many ways, the Salt Lake Tabernacle has become the public face of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The thousands who enter the hall to hear a politician, enjoy a concert, view a production, or listen to its choir experience a different side of Mormonism. As the Church’s most visited historic site, Temple Square and its famed Tabernacle fulfill, in small measure, an earlier directive from the Lord regarding Nauvoo. “Let it be a delightful habitation for man, and a resting-place for the weary traveler, that he may contemplate the glory of Zion, and the glory of this, the corner-stone thereof; that he may receive also the counsel from those whom I have set to be as plants of renown, and as watchmen upon her walls” (D&C 124:60–61).

The Tabernacle as Pioneer Hallmark

The Salt Lake Tabernacle faced new challenges throughout the latter half of the twentieth century; it had to house general conference for a membership approaching thirteen million, balance cultural, civic, and choral demands, and serve as a state-of-the-art recording and broadcast studio. Though leaders did their best to keep the building up to date, technology and Church growth eventually brought significant changes to the edifice. The construction of the neighboring Conference Center, followed by the renovation of the Salt Lake Tabernacle itself, brought the building into a new phase of life. Today it stands as a pioneer hallmark, a visible connection to the Church’s triumphant past.

Though technological and safety concerns certainly contributed to the choice to construct the Conference Center, a driving force behind the change was seating, the very issue that led to the Tabernacle’s construction more than 140 years earlier. In announcing the construction of the Conference Center, President Hinckley remarked,

I regret that many who wish to meet with us in the Tabernacle this morning are unable to get in. There are very many out on the grounds. This unique and remarkable hall, built by our pioneer forebears and dedicated to the worship of the Lord, comfortably seats about 6,000. Some of you seated on those hard benches for two hours may question the word comfortably.

My heart reaches out to those who wish to get in and could not be accommodated. . . .

We recognize, of course, that we can never build a hall large enough to accommodate all the membership of this growing Church. We’ve been richly blessed with other means of communication, and the availability of satellite transmission makes it possible to carry the proceedings of the conference to hundreds of thousands throughout the world.

But there are still those in large numbers who wish to be seated where they can see in person those who are speaking and participating in other ways. [50]

At the first general conference held in the completed Conference Center, President Hinckley further remarked, “The Tabernacle, which has served us so well for more than a century, simply became inadequate for our needs.” [51]

While inadequate as a meeting hall, the building was preserved to serve a different function—as a monument to pioneer resourcefulness and a visual connection to both past struggles and future growth. President Packer commented on the building’s symbolism, “The Tabernacle stands here next to the temple as an anchor and has become symbolic of the Restoration. It was built by very poor and very, very ordinary people. It is now known worldwide.” [52] However, to continue to send this message, the Tabernacle needed to be preserved, necessitating the building’s renovation from 2005 to 2007. Commenting on the renovation, President Gordon B. Hinckley observed, “We must do extensive work on the Salt Lake Tabernacle to make it seismically safe. . . . The time has come when we must do something to preserve it. It is one of the unique architectural masterpieces in the entire world and a building of immense historical interest. Its historical qualities will be carefully preserved, while its utility, comfort, and safety will be increased.” [53]

As President Hinckley noted, making the building seismically safe was the primary focus of the Tabernacle’s recent upgrade. A seismographic study may have, in fact, initiated the project. While building practices had changed dramatically since its construction, the Tabernacle’s original design remained largely unchanged. However, an account of the renovation reported, “One day church leadership asked the very pertinent question, ‘How would this building cope in an earthquake?’ . . . The answer was not favorable.” The Church commissioned the Salt Lake architectural firm FFKR to investigate. Using the 1994 Northridge California tremor as a model, they evaluated the effects a large quake would have on the historic structure. Architect Roger Jackson responded, “The study showed that the big stone piers, which are three ft. wide, nine ft. long and vary in heights from 12 to 21 ft., would start to tip over. And at about the same time, the big wood trusses would slide from the tops of them. So to the question, ‘How would it cope?’ the answer was, ‘Not very well.’” [54] Structural engineer Jeff Miller summarized the problem: “The biggest deficiency in the whole structure was that nothing was really tied together, especially the roof.” To protect against possible tragedy, engineers added steel trusses to each king truss, installed a steel-belt truss where the piers meet the roof, secured the balcony to the walls, and reinforced each pier with improved steel and concrete foundations. The work essentially tied together the structural elements of the Tabernacle “so that the edifice would move as a single mass in the event of a major earthquake.” [55]

Preparing new steel and concrete foundations to reinforce external piers of the Tabernacle. (© Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

Preparing new steel and concrete foundations to reinforce external piers of the Tabernacle. (© Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

Utility, comfort, and safety were also improved significantly during the renovation. With the completion of the spacious Conference Center in the spring of 2000, the need for maximum occupancy in the Tabernacle was reduced. Accordingly, seating was rearranged on both the main floor and the balcony, expanding spacing between rows and lowering the building’s seating capacity by more than one thousand. [56] Replica pews made of oak replaced the original faux-painted white pine pews, though several were preserved near the rear of the facility for exhibition purposes. [57] While the new pews are more accommodating than the originals, President Hinckley still quipped at the building’s rededication, “As you’ve already discovered, the new benches are just as hard as the old ones were!” [58] Additional comforts include air conditioning for the choir seats and podium and interior staircases for the balconies, which previously were accessible only from the exterior. Finally, although unseen by the average visitor, the basement facilities were significantly improved with renovated choir offices, dressing rooms, rehearsal areas, and a recording studio. [59] Work in the basement also included the addition of a large lift capable of moving “the organ console, parts of the lectern, a grand piano, and other elements between the basement and the main floor.” [60] These changes allow the building to quickly transform into any one of its three major configurations: a full rostrum for large meetings, a limited rostrum for small meetings, and a stage for concerts with orchestra. [61]

Throughout the entire process, Church leaders charged construction crews to maintain the Tabernacle’s historical integrity. Announcing the renovation, President Hinckley remarked, “Buildings, like men, get old. They don’t last forever unless you look after them, and this building is old now.” [62] The improvements made by the Church during renovation reflect an attempt to preserve and protect this jewel of Church architecture. President Hinckley continued, “I respect this building. I love this building. I honor this building. I want it preserved. I want the historicity of it preserved. I don’t want anything done here which will destroy the historical aspect of this rare gem of architecture. Now in the process of working on it, they’ll have to put in some steel work, yes, and so on. But I don’t want a modern, 2004–2005 building. I want the old original Tabernacle, its weak joints bound together and preserved and strengthened and its natural and wonderful beauty preserved and strengthened.” [63] He warned those involved in the project, “Now, [to] the engineers, the architects, I just want to say, be careful. Don’t you do anything you shouldn’t do, but whatever you do, do well and do right. . . . [Bishop H. David Burton is] going to take you through an exercise on exactly what they’re going to do. But I am going to say this, when the drawings are all complete, I’m going to take another look at them to see that nothing is destroyed that shouldn’t be destroyed.” [64]

With the renovation complete, President Hinckley seems to have made good on his promise to ensure historical accuracy. Indeed, this goal appears to have guided the entire project. “President Hinckley’s request to return the ‘old original Tabernacle’ became the standard for making difficult architectural and construction decisions. The phrase was used to express the essence and objective of the project,” [65] recalled Bishop Burton. Architect Roger Jackson summarized the difficulty: “The major challenge was to preserve the feel and character and the historic integrity of the building and to not let this work overshadow the building and its history.” [66] At the building’s dedication, Bishop Burton reported on their success: “A charge was extended to preserve, strengthen, and return the old original Salt Lake Tabernacle, revitalized and ready for another period of distinguished service. Today, dear President, we present this senior citizen of a building, all attired in a fresh new finish, fitly framed together in its historical elegance—although a bit more comfortable. The Presiding Bishopric, along with more than 2,000 craftsmen, proudly return the ‘old original Tabernacle,’ along with a 100-year warranty.” [67]

Moving the Tabernacle through the renovation and into a new phase of utility has taught Latter-day Saints much about the building as well as their past. During the renovation, Church archivists acquired previously unknown early architectural renderings for portions of the building, adding to appreciation of pioneer craftsmanship. Scientists at Brigham Young University took advantage of access to early timbers during the project to date the lumber, and in the process learned about pioneer resourcefulness. They found that timbers from early structures, possibly the Temple Square boweries, were reused during the meager years when early settlers carved a living from a barren desert. [68] These are the kinds of lessons the renovation’s champion, President Hinckley, encouraged. “It is good to look to the past to gain appreciation for the present and perspective for the future,” he remarked. “It is good to look upon the virtues of those who have gone before, to gain strength for whatever lies ahead. It is good to reflect upon the work of those who labored so hard and gained so little in this world, but out of whose dreams and early plans, so well nurtured, has come a great harvest of which we are the beneficiaries. Their tremendous example can become a compelling motivation for us all, for each of us is a pioneer in his own life, often in his own family, and many of us pioneer daily in trying to establish a gospel foothold in distant parts of the world.” [69] The preservation of the Tabernacle has moved the building into its third phase of utility, that of a historic landmark that teaches modern Saints about the past.

Conclusion

“A building develops a personality of its own,” President Gordon B. Hinckley remarked of the historic Salt Lake Tabernacle. [70] In many ways, the personality of the Tabernacle reflects that of the Church. Born of pioneer necessity, the building’s original purpose—to seat the Saints—has long been supplanted. However, in spiritual and historical significance, it cannot be replaced.

While witnessing the development of the kingdom, the Tabernacle has undergone changes in form and purpose to match those experienced by the saints. As a meeting hall, the Tabernacle could never host all of the faithful. However, it has been transformed from a place of refuge and utility to one of outreach and now tribute to a triumphant past. John Taylor’s plea at the building’s dedication continues to be fulfilled: “Pour out thy Holy Spirit, we pray thee, upon every sincere soul now before thee.” [71]

For nearly 150 years, the Tabernacle has stood as a silent witness to significant events in Church and world history. When it opened in 1867, it was the primary meeting place for a Church with a membership of approximately one hundred thousand located in only four stakes (Salt Lake, Weber, Utah, and Parowan) and ten missions. [72] A sixty-six-year-old Brigham Young presided over the first general conference in the building, an occasion at which the Church sustained twenty-eight-year-old Joseph F. Smith as the newest member of the Quorum of the Twelve. Now fourteen decades, fourteen Church Presidents, and thirteen million members later, the building still stands as a solid reminder of the faith, ingenuity, and vision of its pioneer builders.

The Tabernacle is the most significant functional assembly hall in the history of the Church. Originally designed to shield occupants from harsh frontier elements, it has since provided a place where listeners can be protected from a spiritual climate much more corrosive. Born of necessity and created with pioneer ingenuity, it has witnessed many of the faith’s most prominent events and hosted its most influential people. The feelings of President Thomas S. Monson characterize its importance for General Authorities and lay members alike: “The Tabernacle is a part of my life—a part which I cherish.” [73]

Notes

[1] Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, Dedication of the Monument to the 20th Maine, October 3, 1889, in Jim Lighthizer, “Reflecting on the 150th Anniversary of the Civil War,” Civil War Preservation Trust, http://

[2] Gordon B. Hinckley, “Good-bye to This Wonderful Old Tabernacle,” Ensign, November 1999, 91.

[3] For additional information on the history of the Salt Lake Tabernacle, see Scott C. Esplin, The Tabernacle: An Old and Wonderful Friend (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2007).

[4] George A. Smith, in Journal History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, August 12, 1855, 1, Church History Library, Salt Lake City; hereafter cited as Journal History.

[5] Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1957), 2:410–11.

[6] Elden J. Watson, “The Nauvoo Tabernacle,” BYU Studies 19, no. 3 (Spring 1979): 416–21.

[7] Ronald W. Walker, “The Salt Lake Tabernacle in the Nineteenth Century: A Glimpse of Early Mormonism,” Journal of Mormon History 32, no. 3 (Fall 2005): 200.

[8] “The New Tabernacle,” Deseret News, June 3, 1863, 387.

[9] David W. Evans, “Discourse by Elder Geo. A. Smith, Delivered in the Tabernacle, Great Salt Lake City, April 7, 1867,” Deseret News, May 15, 1867, 154.

[10] David W. Evans, “Remarks by President Brigham Young, Delivered in the Tabernacle, Great Salt Lake City, April 7, 1867,” Deseret News, July 10, 1867, 218.

[11] “The Thirty-seventh Semi-annual Conference,” Salt Lake Telegraph, in Journal History, October 6, 1867, 1.

[12] “Fortieth Annual Conference,” Deseret Evening News, in Journal History, April 5, 1870, 3.

[13] Steward L. Grow, “A Historical Study of the Construction of the Salt Lake Tabernacle,” in Scott C. Esplin, The Tabernacle: An Old and Wonderful Friend (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2007), 251.

[14] “All Ready,” Salt Lake Daily Herald, April 1, 1884.

[15] “The New Tabernacle Dedicatory Prayer,” Deseret News, October 20, 1975, 594.

[16] Kenneth W. Godfrey, “150 Years of General Conference,” Ensign, February 1981, 70. The five conferences convened outside the Salt Lake Tabernacle include the April and October 1885 conferences held in Logan, the April 1886 conference held in Provo, the October 1886 conference held in Coalville, and the April 1887 conference held again in Provo.

[17] Godfrey, “150 Years of General Conference,” 70.

[18] H. David Burton, “If These Old Walls Could Talk,” Ensign, May 2007, 32–33.

[19] Boyd K. Packer, “The Spirit of the Tabernacle,” Ensign, May 2007, 27–28.

[20] Packer, “Spirit of the Tabernacle,” 27.

[21] Stephen L. Richards, in Conference Report, April 1952, 46.

[22] Richards, in Conference Report, 45.

[23] Richards, in Conference Report, 46.

[24] Howard W. Hunter, “The Tabernacle,” Ensign, November 1975, 96.

[25] Walker, “Salt Lake Tabernacle,” 199.

[26] Walker, “Salt Lake Tabernacle,” 208–9.

[27] Lady Hardy, “The Tabernacle, Salt Lake City,” in Historic Buildings of America as Seen by Famous Writers, ed. Esther Singleton (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1906), 217–18.

[28] In Walker, “Salt Lake Tabernacle,” 210.

[29] In Walker, “Salt Lake Tabernacle,” 210.

[30] In Walker, “Salt Lake Tabernacle,” 210–12.

[31] Hinckley, “Tabernacle in the Wilderness,” Ensign, May 2007, 43.

[32] Hunter, “Tabernacle,” 95–96.

[33] Arnold J. Irvine, “8 Prophets Spoke from Its Podium,” Church News, September 30, 1967, 5.

[34] Kate B. Carter, The Great Mormon Tabernacle (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1967), 62.

[35] Harold Lundstrom, “Voices of the Musical Great Echoed in Historic Salt Lake Tabernacle,” Church News, September 30, 1967, 6.

[36] Eleanor Knowles, “Focal Point for Important Events,” Improvement Era, April 1967, 24.

[37] Lundstrom, “Voices of the Musical Great,” 7.

[38] For additional information on the choir, see Lloyd D. Newell’s work herein.

[39] Packer, “Spirit of the Tabernacle,” 26–27.

[40] Richards, in Conference Report, April 1952, 44.

[41] Hinckley, “Tabernacle in the Wilderness,” 43.

[42] Irvine, “8 Prophets Spoke from Its Podium,” 5.

[43] Gerry Avant, “‘Balm for Wounded Hearts’ at Memorial,” Church News, September 22, 2001, 3.

[44] In Carter, Great Mormon Tabernacle, 64.

[45] Knowles, “Focal Point for Important Events,” 23.

[46] Carter, Great Mormon Tabernacle, 62.

[47] Knowles, “Focal Point for Important Events,” 25.

[48] Carter, Great Mormon Tabernacle, 61–62.

[49] Carter, Great Mormon Tabernacle, 61.

[50] Hinckley, “This Glorious Eastern Morn,” Ensign, May 1996, 65.

[51] Hinckley, “This Great Millennial Year,” Ensign, November 2000, 68.

[52] Packer, “Spirit of the Tabernacle,” 28.

[53] Hinckley, “Condition of the Church,” Ensign, November 2004, 5–6.

[54] Lynne Lavelle, “A Singing Endorsement,” Traditional Building 22, no. 6 (December 2009); www.traditional-building.com/

[55] Brett Hansen, “Gathering Strength,” Civil Engineering 8, no. 77 (August 2007): 49.

[56] Hansen, “Gathering Strength,” 52–53. Architect Roger Jackson said that the number of balcony rows was reduced from nine to seven and the spacing on the floor was expanded from nine to fourteen inches. Roger Jackson, “If These Walls Could Talk: Preserving the Historic Salt Lake Tabernacle” (lecture, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, January 18, 2008).

[57] “Tabernacle Project Fact Sheet,” Newsroom; http://

[58] Hinckley, “Tabernacle in the Wilderness,” 43.

[59] Jennifer Dobner, “Mormon Tabernacle Reopens after Renovations, Seismic Upgrade,” Deseret News, April 1, 2007.

[60] Hansen, “Gathering Strength,” 53. Unfortunately, the addition of this lift also led to what may be the renovation’s “largest casualty from the standpoint of preservation”—the “timber framing system that was used to support the original podium” had to be removed to accommodate the lift. “It was hopelessly in the way,” remarked architect Roger Jackson. “That was a piece of old fabric that would have been really nice to keep” (53).

[61] Hansen, “Gathering Strength,” 53.

[62] Gordon B. Hinckley, “Tabernacle Renovation Press Briefing,” October 1, 2004; see newsroom.lds.org.

[63] Hinckley, “Tabernacle Renovation Press Briefing.”

[64] Hinckley, “Tabernacle Renovation Press Briefing.”

[65] H. David Burton, “If These Old Walls Could Talk,” Ensign, May 2007, 32.

[66] Hansen, “Gathering Strength,” 49.

[67] Burton, “If These Old walls Could Talk,” 32.

[68] Matthew F. Bekker and David M. Heath, “Dendroarchaeology of the Salt Lake Tabernacle, Utah,” Tree-Ring Research 63, no. 2 (2007) 95.

[69] Hinckley, “The Faith of the Pioneers,” Ensign, July 1984, 3.

[70] Hinckley, “Good-bye to This Wonderful Old Tabernacle,” Ensign, November 1999, 91.

[71] “The New Tabernacle Dedicatory Prayer,” The Deseret News, October 20, 1875, 594.

[72] Henry A. Smith, “137th Conference Will Note Tabernacle’s 100th Birthday,” Church News, September 30, 1967, 3.

[73] Thomas S. Monson, “Tabernacle Memories,” Ensign, May 2007, 42.