Veteran Accounts

Kenneth L. Alford, “The Iraq War: Veteran Accounts,” in Saints at War: The Gulf War, Afghanistan, and Iraq (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 198‒278.

(Arranged alphabetically by last name)

GREGORY T. ADAMS

During Operation Iraqi Freedom, Greg Adams served 2009–10 as a U.S. Army lieutenant colonel (promotable). His assignments included deputy director for all Iraqi army training and military adviser to the Iraqi Army joint training staff. He also served in the first Baghdad Iraq Military District presidency. He currently lives in Utah, where he is a coordinator for the Church’s Institutes of Religion program. He has served in many Church positions including district presidency, bishop, stake high council, and elders quorum president.

Soldiers from a brigade combat team are shown while on patrol on April 8, 2005. Courtesy of DoD.

Soldiers from a brigade combat team are shown while on patrol on April 8, 2005. Courtesy of DoD.

As I boarded the “Freedom Flight” in Kuwait to return home to my family in the United States, I was placing my luggage in the cargo bay when I heard “Bruder Adams, Wie geht’s!” It took me by surprise. I had grown accustomed to hearing Arabic during the last year and was now hearing German, the language of my mission. I turned around and saw my old mission companion from Wuppertal, Germany—Elder Checketts. I had not seen him for years. He was now Colonel Gus Checketts and was returning home after arranging for his command to deploy to Balad, Iraq, in the coming months.

We enjoyed a wonderful flight reminiscing about our missions in Germany. I also outlined all of the wonderful events happening in the Church in Iraq. As we parted after landing in the States, I asked him to give me a call before he returned to Iraq. He called several months later, and I asked when he was deploying. He said he was leaving the next week but asked me to guess where he was. When I expressed I had no idea, he told me he had just left Elder Paul Pieper’s office at Church headquarters in Salt Lake City. Elder Pieper had just finished setting him apart to take my place in the district presidency in Iraq! Later that year, Gus was called to be the third president of the Baghdad Iraq Military District. After so many years, who would have ever thought two young missionary companions would again cross paths as soldiers in a war with an opportunity to bring the blessings of the gospel to Iraq.

I had many memorable experiences while serving my country in Iraq. Some were very rewarding and others were very difficult, as soldiers often witness man’s inhumanity to man. However, seeing the Lord’s hand with the people of Iraq and experiencing his love for them and for those serving in the country gave me a different perspective regarding God’s love and his divine plan for us all. It surely was a great privilege to serve my country and the Lord during that remarkable time.

KEN BACKES

Ken Backes served as the military assistant to the senior adviser for health for the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), which enabled him to work closely with the Iraqi minister of health and his staff.

The first Iraqi I met was Saba, a translator. She was a beautiful twenty-four-year-old woman who had recently graduated from college and hoped for a medical career. She was a bit shy on our first meeting, and she quickly introduced me to her friend Muntador, who was also a translator. Muntador went to school with Saba and had also recently graduated. He was twenty-five years old and looking forward to eight years of schooling to qualify as a brain surgeon—a skill sadly lacking in Iraq. Both Saba and Muntador were upbeat and positive about the future. Saba spoke with an Irish accent, strangely enough. She learned English from watching American movies. She shared the Iraqi version of cheese puffs with us, and we teased her about her “boyfriend” Muntador, although she protested that he was only a friend from school. The day ended with me feeling very positive about Iraq’s future.

Brass shell casings lie scattered in the road as U.S. Army soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division provide security after an altercation in Baghdad, Iraq, on February 22, 2006. Courtesy of DoD.

Brass shell casings lie scattered in the road as U.S. Army soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division provide security after an altercation in Baghdad, Iraq, on February 22, 2006. Courtesy of DoD.

The next day was not as good. We were headed out of the palace when my boss got a call from Ambassador Bremer’s office requesting a briefing on the Hajj [the Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca]. After a quick U-turn, we made our way to the office and received some guidance on preparing material for the governing council. As we left the palace, my phone rang. Our director of operations told me that someone had attempted to carjack the car of the director general and shot his driver, wounding him. He also said one of our translators had been assassinated in front of her home. I felt the air go out of my lungs as I realized he was talking about Saba, my new Iraqi friend. Apparently, the Iraqi version of the Mafia inside the Iraq Ministry of Defense threatened six people who were cooperating with the management of the ministry as they reorganized. Saba was the first on their list. Much of the day was spent in discussions and grief counseling for friends of Saba and employees of the ministry. We learned that Muntador had planned to meet Saba’s family tonight to ask for her hand in marriage. (Apparently, she was more enamored by him than she let on.) Tragically, he met her father for the first time as he told him of her death.

So that’s how things go in Iraq—good days and bad days. Democracy is messy and building it will unfortunately require some sacrifices that will be tough to make. I’m positive that what we are doing here is the right thing, and I’m proud to be contributing to this effort in a small way.

MICHAEL BEESLEY

See Michael Beesley’s brief biography in the Afghanistan section.

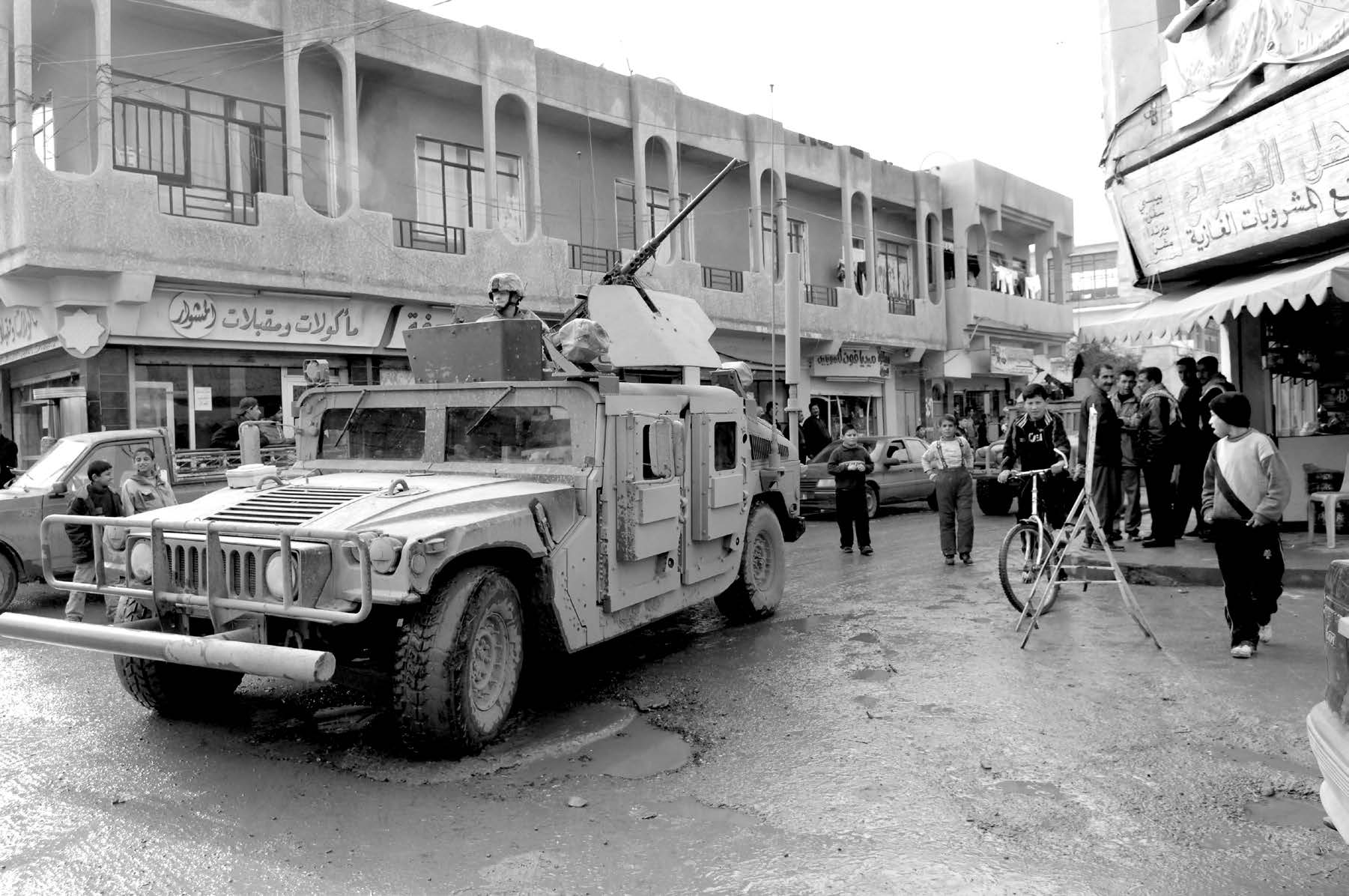

A local Iraqi boy observes U.S. Army soldiers in downtown Tall Afar, Iraq, on October 11, 2005.

A local Iraqi boy observes U.S. Army soldiers in downtown Tall Afar, Iraq, on October 11, 2005.

Courtesy of DoD.

Every month, the commander of the 511th Military Police Company and his personal security detail (PSD), to which I was attached, would hook up the trailers. Then, with a fist full of money, we would convoy into Duhok in Kurdistan, Iraq, to purchase supplies for the Iraqi Police (IP) stations we were in charge of. I had the opportunity to go on such trips if I wanted and decided to join up with this one. I had heard that Duhok was one of the friendly provinces in Kurdistan—one where you could walk freely down the streets without having to worry. I was looking forward to a change of scenery and being able to stroll into stores and restaurants again.

After we passed through the southern battle zones, the mood in the Humvees changed noticeably. Some of us even took off our helmets. Well, I didn’t need an invitation. I happily took any opportunity to take that heavy thing off without putting myself in danger. When we pulled into Duhok, I was surprised to see people, especially women, roaming about in western attire and looking normal, at least to me. There were no long, black, head-to-toe burkas or niqabs (face coverings that are traditionally worn in the south).

Our soldiers knew where they needed to go to get their supplies. After agreeing on a time to return, we all went our separate ways. As we started out, we were immediately thronged by a group of young boys, ages eight to fifteen, who were standing by to assist us with directions, answers, and translation. They even held our bags as we walked. One of the older boys sized me up quickly and cheerfully introduced himself in almost perfect English as he extended his hand in friendship. I was duly impressed and gladly accepted his offer to help. As we walked from place to place, I noticed that my helper was the ring leader of the group, as he would order other boys to be runners for certain items. When they returned, he would take the items from them and give them to me. I also noticed that he was sometimes mean and demanding to the smaller ones, at times slapping them about the head as he scolded them in Kurdish. I had to confront him a couple of times and let him know that wasn’t necessary. He would smile, grab my hand, and then shake it. After observing this young guy in action, I realized that this well-dressed kid with the flashy smile was simply a hustler, doing what he had to do and using who he had to use to make a buck. I also knew that the payoff would come at the end of the day. I was sure he was expecting the “rich American” to reward him for his service rendered.

For the remainder of the time we were together, I couldn’t help but notice a scruffy little guy who lagged behind, seemingly not interested in the run-and-get-things job. He was a polite boy when spoken to and also spoke very good English. I kept my eye on him and went out of my way to recognize him when the bigger kids would push him aside. The last hour, I walked with him, making sure he was by my side the whole time, which I could tell infuriated my older and wiser escort. There was just something about that little freckle-faced boy that captured my heart. He appeared poorer than the rest, as his clothes were torn in places and his face was a little dirtier. But he had a unique spirit about him—a quiet confidence that all would be well. As we talked, I learned he lived with his mother and didn’t have a father. He was proud of the fact that he went to school, and he wrote down a few words in English for me on a small notepad he carried. I would purchase things like bananas or ice cream for the kids as we walked, and they would all clamor around with arms extended in an attempt to get theirs first, except for this little fellow. He would wait politely, standing in the back and never expecting anything.

U.S. Army soldiers with the 14th Cavalry Regiment from Fort Wainwright, Alaska, near the Syrian border monitor the movement of local Iraqis by the Euphrates River in Iraq on October 2, 2005. Courtesy of DoD.

U.S. Army soldiers with the 14th Cavalry Regiment from Fort Wainwright, Alaska, near the Syrian border monitor the movement of local Iraqis by the Euphrates River in Iraq on October 2, 2005. Courtesy of DoD.

When our day of walking and shopping was over, sure enough, our helpers were Johnny-on-the-spot with their hands out! Though this kind of irritated me, I was grateful for their assistance and therefore gave each of them a few U.S. dollars. The bigger boy showed his disapproval with what he received—to the point I almost took it back. I looked around for my little friend, but he was gone. I concluded that he probably got caught up in the large crowd that had gathered to see us off. Before we left, I noticed the older boy wore two colored rubber wristbands with words in English embossed on the outside. When I asked him about the bands, he quickly took off the blue one and handed it to me. I declined but thanked him. He was insistent and pressed the small gift into my hand. I again thanked him; this time accepting his offer. As we drove off, I looked down at the band and read “Expect a Miracle” written on it. I liked what I saw and slipped it on.

I was later transferred to Sulaymaniyah in the northern part of Kurdistan. I decided to join the military on their trip to Duhok. It had been several months since I was last there, and I decided I needed another break from Tal Afar. Upon our arrival, the same group of boys met us, and I was delighted to see my little buddy among the group. I quickly reunited with him, put my arm around his shoulder, and gave him a little squeeze. I could tell he was as glad to see me as I was to see him. He talked freely and openly as we walked. The other boys looked on with envy. They knew this little eight- or nine-year-old boy had captured my attention and my heart. I offered to buy him things along the way, but he politely refused each time.

At the end of that most rewarding day, I took him aside. While kneeling on one knee, I took the liberty to give him some fatherly advice. I encouraged him to stay in school and to go to college. I told him to never smoke or drink and to always look after his mother and two younger brothers. He listened intently and promised me he would. I reached into my pocket and pressed a fifty-dollar bill into his small hand. I made him promise me he would give the money to his mother. He again assured me he would, and I believed him. I gave him a big hug, and he squeezed back. I opened the door to our Humvee and sat down, making ready to depart. As I was closing the door, my little lifelong-in-spirit buddy ran over and pointed yearningly at my blue wristband, then pointed back at himself. A flood of emotion came over me as I took off the band and handed it to him. I slowly closed the door. As we pulled forward, I looked out the thick bulletproof window for what would probably be the last time I would ever see him and noticed tears streaming down his face. The last thing I remember as we left Duhok that memorable day was this little boy pressing his fingers to his lips as he blew a kiss my way. Expect a miracle? I had just been allowed to be a small part of one that day.

FAREED M. AND JOAN S. BETROS

Fareed M. Betros, a 1981 graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, served on active duty during both Gulf Wars. He was a colonel in the U.S. Army Reserve, speaks Arabic, and is a Middle East expert. He worked in Baghdad, Iraq, as the coalition civil-military adviser for the executive offices of the Iraqi Ministry of Defense. He served in many Middle East assignments, both in the military and as a civilian contractor. He has worked as a volunteer for his church and other civic organizations. He is married to Joan Synan Betros.

Joan Synan Betros has many years of experience in the media industry with writing, hosting, casting, interviewing, reporting, and directing family television programming with an emphasis on women’s and children’s issues. She was the director of women’s and children’s family television programming for the Iraqi Media Network under the direction of the Coalition Provisional Authority. She wrote and produced a family-oriented television talk show in Saudi Arabia. Formerly, Joan was an executive producer for CNN, CNN International, CBS, Transworld Media Publicity Corporation, the King Faisal Foundation, and other cable networks. She has served as a Relief Society president and in numerous other Church callings.

December 29, 2005

In almost twenty years of marriage, we have shared many unique experiences together. One of the most dramatic was in Iraq. As a U.S. Army Reserve lieutenant colonel, I served on active duty there from May 2003 to July 2004 supporting the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA). My wife, Joan, arrived in Iraq in December 2003, working as executive director of family television programming for the Iraqi Media Network (IMN). Our experiences together in Iraq bonded us together more strongly than ever before.

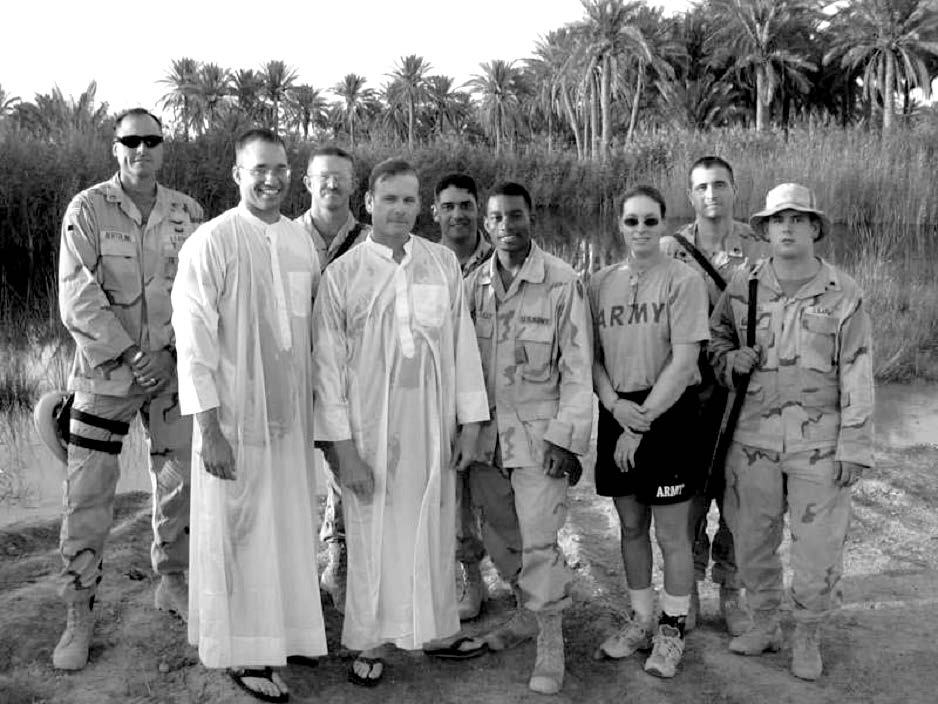

Joan and Fareed Betros served together in Baghdad. They are pictured at the Baghdad International Airport on Christmas Eve 2003. Courtesy of Joan

Joan and Fareed Betros served together in Baghdad. They are pictured at the Baghdad International Airport on Christmas Eve 2003. Courtesy of Joan

and Fareed Betros.

My tour of duty in Iraq was not my first Middle East deployment. In 1989, I decided to join the Utah National Guard (UTNG) and was placed in charge of their Arabic language section. I was called to active duty in August 1990 after Saddam Hussein attacked Kuwait. As an Army captain, I led a detachment of Arabic translators in the Kuwait theater during Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm.

I deployed with my unit to Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Kuwait for nine months. We were attached to various U.S. forces to assist with vital translation requirements. I worked as a cultural affairs advisor and translator, interacting closely with Saudi military and government officials. I also worked with many Iraqi refugees and prisoners of war.

Our journey back to Baghdad started as a result of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. As a U.S. Army Reserve lieutenant colonel and Middle East expert, I was called to active duty. We were living in northern Virginia. As the executive director of a public and cable television station, Joan became closely involved with news coverage of those events. She produced a television special that saluted families affected by the tragedy.

I arrived in Iraq in May of 2003. Our immediate mission concerned the dissolving of the Iraqi military. The Iraqi Ministry of Defense (MOD) and Iraqi military had been dissolved by order of Ambassador Bremer shortly before my arrival. My primary task was to find a way to pay hundreds of thousands of former Iraqi military personnel a monthly stipend in lieu of their monthly pay.

Through a contact I made, Joan was able to obtain a position to work in Iraq as the executive director for family television production. On December 24, 2003, Joan became my Christmas present when she arrived at the Baghdad International Airport. Fortunately, we both worked in the main presidential palace in the Green Zone and were able to stay in a small trailer.

Our first evening together in Baghdad was memorable. As we started to settle in for the evening after a long day, we heard the loud swoosh of a rocket being launched. A moment later, we heard the much louder explosion as the rocket slammed into the Sheraton Hotel across the Tigris River. Our trailer was situated close to the river so the rocket attack sounded as if it was right on top of us. We dove for the floor, put on our helmets and protective vests, and wished each other a merry Christmas!

Several people were killed during a suspected car bombing outside Entrance 1 to the Coalition Provisional Authority on January 18, 2004, at 8:03 a.m. local time. The vehicle exploded in the middle of the intersection outside the gate, causing massive destruction. Courtesy of DoD.

Several people were killed during a suspected car bombing outside Entrance 1 to the Coalition Provisional Authority on January 18, 2004, at 8:03 a.m. local time. The vehicle exploded in the middle of the intersection outside the gate, causing massive destruction. Courtesy of DoD.

January 18, 2004, started like most other days. Joan was scheduled to give a presentation that afternoon on her programming ideas to some officials at the CPA palace. I was going to meet my team at the Green Zone checkpoint so we could work on the stipend payments. I was in a bit of a rush to get out the door that morning because I did not want to be late. As I placed my hand on the door handle of our trailer, I paused for a moment and then released the handle. I felt Joan might need some assistance going over her presentation. I asked if she would like some help, and she said yes.

We left our trailer and walked to the palace. We were standing in the hallway when I said goodbye. Less than fifteen seconds after separating from each other, a powerful explosion rocked the palace, knocking out some of the windows. I ran back to Joan to ensure she was all right. We listened for any special instructions that might come from the guards but quickly learned the explosion had occurred some distance from the palace. Then we received the news that the explosion had occurred at the gate where I was scheduled to meet my team.

A Blackhawk helicopter from the 106th Aviation Regiment, Illinois Army National Guard flies past one of Saddam Hussein’s former palaces in Tikrit, Iraq. Courtesy of DoD.

A Blackhawk helicopter from the 106th Aviation Regiment, Illinois Army National Guard flies past one of Saddam Hussein’s former palaces in Tikrit, Iraq. Courtesy of DoD.

I raced to the main gate to look for my Iraqi team. What I found was a terrible scene of destruction. I soon found one of my team leaders. He told me three members of the team had been slightly injured. Fortunately, they had been on the opposite side of a large intersection in front of the main gate—a distance of about sixty meters. The car bomber had stopped his car about fifteen feet from where I would have been standing, if I had not stayed to help Joan. The explosion was so powerful it made a crater about two feet deep and ten feet round in the street pavement. The blast killed twenty-four people and wounded over eighty others. When I reached the site, emergency crews were already there and had taken the injured to local hospitals. A number of cars were on fire or still smoldering.

That day was a Sunday. Despite our busy schedules in Iraq, we always made it a point to attend church together. Our service was scheduled for 2:00 p.m., and with everything that happened that morning, we definitely planned on going. As we walked into the part of the palace set apart for chapel services, we heard the start of the opening song, “Count Your Blessings.” We definitely had much to be thankful for.

JIMMY F. BLACKMON

Jimmy Blackmon grew up in Ranger, a small town in northern Georgia at the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. He joined the Army Reserves in 1987 and attended North Georgia College (a military college with strict military lifestyle rules) in Dahlonega, Georgia. He joined the Church and married the former Lisa Martin in 1992. He served as an Army Aviator and Ranger and was stationed at Fort Benning, Georgia; Fort Rucker, Alabama; Fort Bliss, Texas; Fort Knox, Kentucky; Fort Hood, Texas; Fort Leavenworth, Kansas; Washington, DC; Buedingen and Hanau, Germany; Italy; and two tours in Iraq. He has served in a variety of Church assignments.

In February 2003, we moved south to Kuwait. After a few days in Kuwait, I flew home to be greeted by my pregnant wife, Lisa, and our three kids. The most difficult thing for me was reuniting with my darling three-year-old, who had forgotten who I was. She knew she had a father. Everyone told her it was me, but she didn’t know me. I’ll never forget her walking up to me numerous times, looking up at me with those crystal blue eyes and asking, “Are you my daddy?”

I’d say, “Yes, Madison. I’m your daddy.”

After which, she would wrap her tiny arms around my leg and hug me as tight as she could while saying, “You’re my daddy.” On the second day, Madison walked into the kitchen and saw me kiss Lisa. She looked up at us and asked, “Are you guys married?”

* * * * *

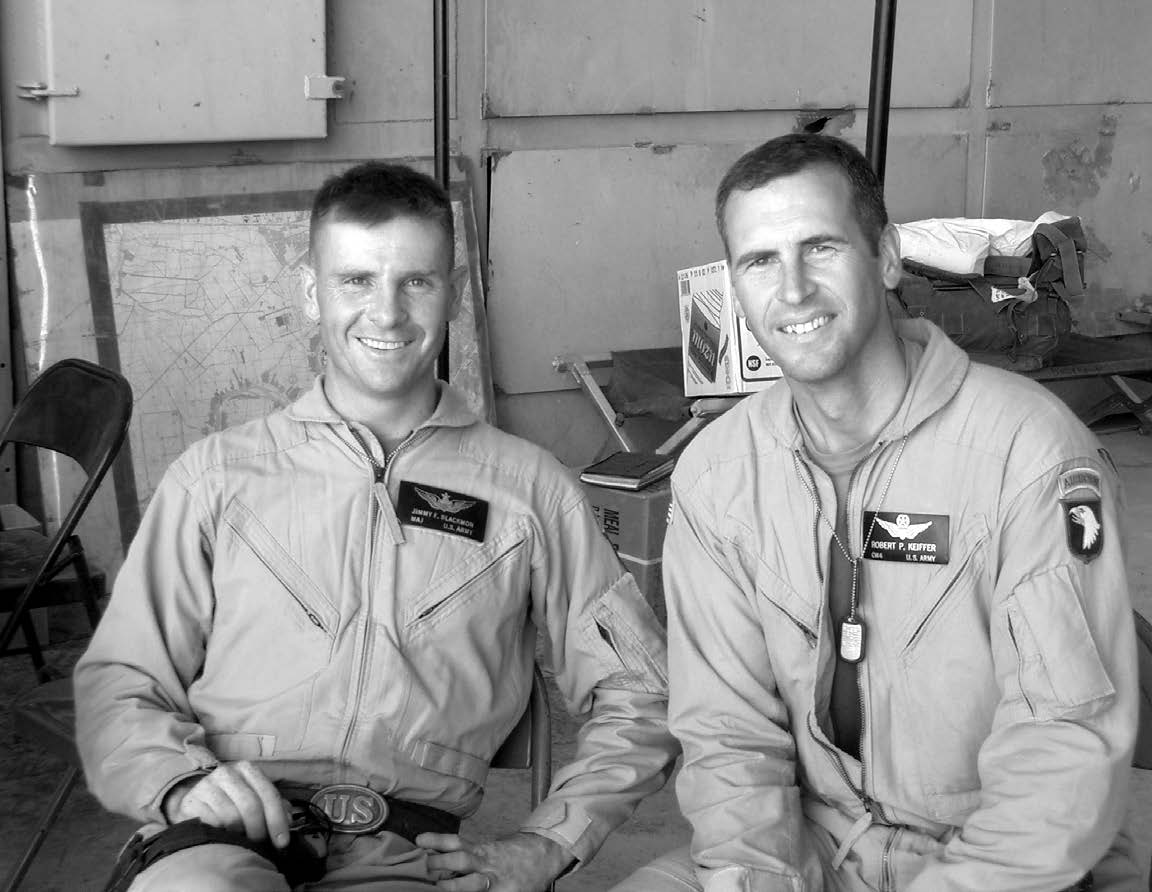

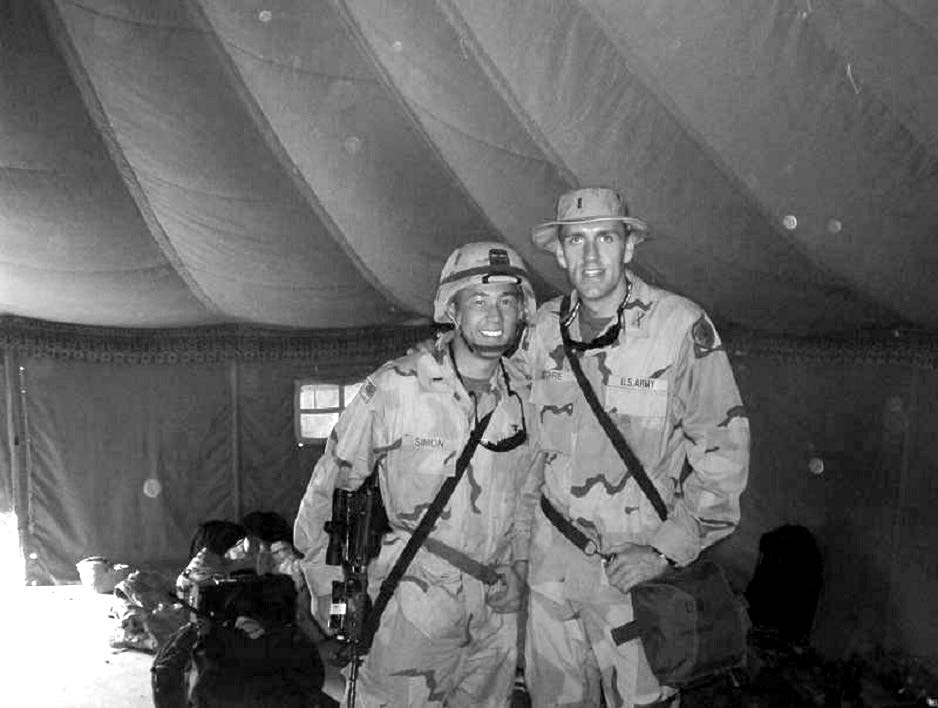

Major Jimmy Blackmon is shown relaxing with a fellow Army aviator. Courtesy of Jimmy F. Blackmon.

Major Jimmy Blackmon is shown relaxing with a fellow Army aviator. Courtesy of Jimmy F. Blackmon.

In June 2003, I deployed to Mosul, Iraq, where I assumed duties as the operations officer of 2-17 Cavalry. It was my first combat experience in actual firefights. In September 2003, we received a mission to locate and destroy a terrorist training camp in southwest Iraq. We conducted reconnaissance in the surrounding area and soon found numerous ammunition caches that included rocket-propelled grenades [RPGs], sniper rifles, mortars, and surface-to-air missiles.

The OH-58D [helicopter] we were flying is ideal for observation. We flew with the doors taken off so we could see better. One afternoon we saw two men sitting in the middle of the desert with their bed-rolls laid out. It was clear they were not Bedouins. They appeared very much out of place. Beside them was a handmade blanket. We came in closer to take a better look at those guys. I was flying in the left seat and had my M4 rifle lying in my lap. Our rotor blew up the blanket, revealing something underneath it. We flew in closer and saw the blanket was covering a cache of weapons. Those two guys were there to watch the cache.

We radioed the command and control helicopter in which our division commander, Major General David Petraeus, was flying and continued to circle the weapons cache. During each pass, we were prepared to fire. The two men realized we had seen the cache. They stood with their hands in the air as if to show their innocence or beg for our mercy. I listened as my squadron commander discussed the situation with General Petraeus. The dilemma was what to do with the two men, as there was no way to get them back to the holding facility at Al Asad [air base]. We realized that our commanding general might direct us to kill those two men. I knew they were terrorists and guilty, but I struggled with the thought of shooting them.

On each pass we came close enough to see their faces. I wished they would pick up a weapon and fire at us, but they only fidgeted with their hands up. Finally, the word came, “Shoot the cache. Blow it up. Leave the men.” My immediate feeling was of relief, but I began to wonder what I would feel if one of those men killed an American service member in the future. We blew up the cache with rockets and machine gun fire and then silently flew back to Al Asad.

* * * * *

This cache of rocket-propelled grenades discovered in southwest Iraq. Courtesy of Jimmy F. Blackmon.

This cache of rocket-propelled grenades discovered in southwest Iraq. Courtesy of Jimmy F. Blackmon.

When I arrived in Iraq for my second tour, I settled in at Forward Operating Base [FOB] Speicher in Tikrit, Iraq. I arrived in September 2005, found the service members’ group, and attended my first meeting. I was amazed at the organization of the group. The Church had made tremendous strides organizing groups and calling group leaders. We had twenty to thirty Saints who regularly attended our meetings. I was set apart as an assistant group leader and was grateful to serve my nation, my church, and the people of Iraq. We received tremendous support from Church headquarters, such as the video Let Not Your Heart Be Troubled, which I found to be most inspirational. I showed it to our division chaplain, a Protestant minister, who was so touched by its powerful message that he suggested to his superiors that they consider making a similar Protestant video.

While serving in OIF I was set apart as a group leader, and as such I tried to ensure that I kept an eye out for my fellow Latter-day Saint members. There was a young man who regularly attended meetings. He seldom spoke with other Church members and routinely slept during lessons. Each Sunday, I noticed he drifted off prior to the opening song. Combat deployments certainly drain you mentally and physically, but this good brother just seemed distant. I began to think how I could approach him and check how he was doing without pressuring him too hard.

One fast and testimony meeting, it was my week to conduct. During the announcements, I noticed that young man had already drifted off. During the passing of the sacrament, I said a prayer asking Heavenly Father that the testimonies today would touch each one present and that we would receive the blessing of the Spirit in our meeting. After my initial testimony, another brother bore his testimony, which was followed by a few moments’ pause, during which I continued thinking about the previously mentioned brother. After a few moments a Samoan brother from the Utah Air Guard came forward. He said he was lonely and didn’t know how we married brothers and sisters did it. He was engaged, and he missed his fiancée dearly. He said he felt alone, even when among friends, but he had a song that helped him. At that moment this fine young brother broke out in song. He stood at the podium and sang “Abide with Me.” It was beautiful. Complete silence consumed the room except for his beautiful voice and occasional sniffles from a congregation filled with teary eyes and the Spirit.

When his testimony was closed, he returned to his seat and wasn’t completely seated before the brother I was thinking about moved to the stand. He thanked our Samoan brother for his song and then related a story to us of him singing that song to a lady who had lost her son. He couldn’t get through the song, and she joined to help him finish. I thought my heart would burst as I listened to that young man bear his testimony of Jesus Christ and the restored gospel. I had prayed fervently, and Heavenly Father had sent a young Samoan brother.

BRYAN BLAIR

Bryan Blair served as a first lieutenant and captain in the Army during Operation Iraqi Freedom II. He was assigned as the company executive officer for Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC), 3rd Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division, stationed in the International (Green) Zone in downtown Baghdad, Iraq. His primary duties involved coordinating logistical support for companies that were housed in the Al Sijood Palace complex. He has always considered central Texas his home despite moving a lot as a child. He served a mission in Paraguay and has held callings in the Primary, Young Men, and elders quorum. In Iraq, he served as a service member group leader.

I deployed March 17, 2004, with HHC 3rd Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division. I was the executive officer for the company, which can be a particularly disdainful job. I wasn’t very happy about leaving my platoon and going to the brigade, but as time went on in Iraq, I saw why the Lord put me in that position. I found myself in a company with several other members of the Church, which wouldn’t have happened if I had stayed with my old battalion. CW2 [chief warrant officer] John Church and I were set apart as service member group leaders before we deployed, and our jobs at the brigade gave us the flexibility and resources to support our Church meetings.

Bryan Blair is shown near the Crossed Sabers monument in Baghdad, Iraq. Courtesy of Bryan Blair.

Bryan Blair is shown near the Crossed Sabers monument in Baghdad, Iraq. Courtesy of Bryan Blair.

We were stationed in the International Zone (Green Zone) in downtown Baghdad. We lived in the Al Sijood Palace compound, which was one of the original palaces Saddam Hussein built in the early 1980s. One of the larger and nicer rooms in the palace was converted into a chapel by the previous unit. We initially held our church services there. Our meetings were simple, but we did our best to make them as close to home as possible. We played our music on CDs because we didn’t have a pianist. I used my computer and printer to make programs for each meeting. We did our best to follow the normal program of instruction using the priesthood manual.

Staff Sergeant Files (left) was baptized by Captain Cudney (right). Courtesy of Bryan Blair.

Staff Sergeant Files (left) was baptized by Captain Cudney (right). Courtesy of Bryan Blair.

About the time of the first Iraqi elections, a battalion from the Wyoming National Guard was attached to our brigade. They worked with the Navy SEALs to provide security for government officials. The Church members from the new battalion did not have a group leader. We decided to hold the meetings in their complex for the convenience of everyone. It was nice to double our size and the list of potential speakers. The chapel in their complex was not as nicely appointed as our room in the palace, so we built a podium and sacrament table.

The week before we redeployed, we had a service member baptism (from the Wyoming unit). Brother Fines, who was baptized, met with us so frequently that we didn’t initially realize he wasn’t a member. After a few weeks, he decided to be baptized and didn’t want to wait until he returned home. We arranged to use one of the pools on the palace grounds next to our headquarters. His white baptismal clothes didn’t arrive in time, so we performed his baptism in uniform. It was a very spiritual experience.

My time in Iraq helped me value the importance of meeting together with other members of the Church. It was the first time I had ever felt anxious to go to church, not because I wanted to be away from work, but because I had to know if my brothers were all safe and sound. I felt a wonderful bond with them.

MARC E. “DEWEY” BOBERG

A former West Point football player, Dewey served a mission in Santiago, Chile. He graduated from the U.S. Military Academy in 1992 and was commissioned in the U.S. Army as an armor and cavalry officer. He served with the 1st Cavalry Division at Fort Lewis, Washington, and taught at the Armor School at Fort Knox, Kentucky, and in the Foreign Language Department at West Point. He deployed to Iraq twice with the 3rd Infantry Division. He also served as the U.S. Army ROTC professor of military science at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah.

When I went to Iraq (Diyala Province, northeast of Baghdad) from 2004 to 2006, we took smaller operating bases and consolidated them into larger ones, trying to transition responsibility to the Iraqis and consolidate U.S. forces. We did the reverse a year later. We pushed out from large operating bases to build platoon and company-sized combat outposts that were more imbedded in the area. We wanted the Iraqi population to see us there 24-7, as opposed to someone who came for a few hours and then left because all kinds of crazy things happened while you were gone. That policy meant that we were in a constant construction mode.

The Latter-day Saint service members’ group at Forward Operating Base Warhorse in Baquba, Iraq, during 2005.

The Latter-day Saint service members’ group at Forward Operating Base Warhorse in Baquba, Iraq, during 2005.

Courtesy of Marc E. “Dewey” Boberg.

About six months into our deployment, we also received two battalions of Georgians from the former Soviet republic of Georgia. There were some communication challenges at times. It was difficult finding Arabic-Georgian-English interpreters, but we had a generally successful fifteen months trying to stop the influx of weapons and ammunition between Iran and Baghdad.

The first week of January 2007, I was at the National Training Center trying to unload the train as President George W. Bush announced the surge, and we immediately were placed on orders to deploy directly from the National Training Center to Kuwait, draw equipment, and move into combat operations as soon as possible. I was in Kuwait about two weeks before they assigned us to east Baghdad, just east of the Tigris River, and the towns and area immediately east of Baghdad. We were tasked with stopping the Iranian influx of weapons into Baghdad, specifically IED-making materials [improvised explosive devices].

We started from scratch. We built a brand-new forward operating base east of Baghdad. We started doing our combat role as quickly as we could, but we were also building living quarters and trying to figure out force protection. And the area had not been patrolled by U.S. forces since the initial invasion. In some ways we kind of disturbed a hornet’s nest. My brigade lost about thirty soldiers in the first six months, primarily due to IEDs on the roads.

* * * * *

Major Marc “Dewey” Boberg (center) is shown during an armor operation as the S3 of 1st Battalion, 30th Infantry, in Diyala Province during Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2005. Courtesy of Marc E. “Dewey” Boberg.

Major Marc “Dewey” Boberg (center) is shown during an armor operation as the S3 of 1st Battalion, 30th Infantry, in Diyala Province during Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2005. Courtesy of Marc E. “Dewey” Boberg.

We normally worked eighteen- to twenty-hour days. Inevitably, you would go back to your tent and fall asleep as fast as you could because you had to get up again in three or four hours. I found that even if I was exhausted and could read only a couple of verses out of my Book of Mormon, it allowed me to clear my head, to realize other priorities. I would stop and pray, and it really caused me to be much calmer under pressure. If you could attend church services, it would rejuvenate you in the same way. It allowed you to take a small amount of time to remove yourself from the very chaotic, often very violent situations you were in. You could reorganize your mind and your spirituality to realize what really is important. It would be incredibly uplifting 99 percent of the time, even if it was only one hour out of an entire week. In those very quick moments of awesome violence, I could maintain my head and understand what was going on around me.

* * * * *

I was called to be a service member group leader. We had an average attendance of about fifteen. We met in a little building designated as a chapel, and we had a set time to meet. Church was about an hour long. We tended to start our meetings as a traditional sacrament meeting—with the sacrament—but instead of talks we tended to then have a lesson out of the priesthood manual. It was kind of a hybrid meeting. Once a month we would have a testimony meeting. We took the sacrament, though, every week. Several members of our group couldn’t attend weekly because of other operations, but they would attend when they could. We attempted to organize some home teaching, but it was not the most effective thing because of the mobility of our units.

* * * * *

I was in no less than seven or eight convoys that got hit by IEDs. Here’s one example: One night I was in my Bradley Fighting Vehicle along with a company who was attempting to secure an extended route from where our brigade headquarters was in Buquba to Muqdadiyah. It was a route where IEDs were placed night after night (they rarely were during the daytime). We were closer to the Iranian border, which meant the enemy had access to higher quality IEDs. We’d been patrolling for seven or eight hours that evening. It was probably three or four o’clock in the morning. We were traveling with five Bradleys headed back toward the forward operating base. I was riding in the second Bradley.

Suddenly, an IED exploded near the front end of my Bradley. There was a huge flash of light. It did not hit the Bradley squarely. It went off a few feet in front of my Bradley. The trigger mechanism must have been slow—detonating after the first Bradley and right before mine. We felt incredibly lucky. Debris went flying past my head. The explosion occurred five or six feet in front of me. I automatically had my gunner start scanning for whoever the trigger man was. The Bradley in front of us heard the explosion, moved forward, and secured the road so we could move out of the blast area. The Bradleys behind us didn’t enter the blast area.

We immediately started to dismount and secure the area. It was a semi-residential area, so we searched the houses around us, looking for suspects. We also checked for injuries. My driver was actually closer to the explosion than I was, but his hatch was closed while my hatch was open. I was looking at what was going on around us. None of us were hurt other than being banged around inside the Bradley. It does wake you up!

We were very lucky it went off at the wrong spot. A similar IED—just two days later—went off under a Bradley, hitting it squarely in the back where the personnel compartment is located. The force of the explosion warped the Bradley Fighting Vehicle’s hull to the point that the entire vehicle has to be removed from combat; however, it did not penetrate the armor. Fortunately, we didn’t lose any soldiers.

My crew was very blessed that we did not suffer anything greater than superficial damage. We had thousands of dollars of damage in broken glass and stuff, but no one ever was evacuated from one of my vehicles after an IED, even though we were hit several times.

DANNY BOYD

Danny Boyd entered U.S. Air Force active duty in July 1986. He served as an intelligence officer in Operation Joint Guard in Bosnia and during two deployments to Iraq, December 2003 to August 2004 and August 2008 to August 2009. Danny has served as a bishop, elders quorum president, ward and stake mission leader, Primary teacher, and high councilor. He currently serves as an early-morning seminary teacher. He married his wife, Laurie, on May 1, 1984.

An Iraqi soldier secures three suspected insurgents after a raid near Kirkuk, Iraq, on March 17, 2005. Courtesy of DoD.

An Iraqi soldier secures three suspected insurgents after a raid near Kirkuk, Iraq, on March 17, 2005. Courtesy of DoD.

I was assigned as an interrogator when I deployed to Iraq in 2004. Our unit was responsible for interrogating prisoners immediately after they were brought in from the battlefield. Some were not guilty of any crimes other than being in the wrong place at the wrong time. This was a determination we needed to make based on evidence brought in from the operation as well as the prisoner’s own testimony during our interrogation.

Suspected insurgents are assembled in a field as members of Iraqi National Guard, together with U.S. Army escorts, search the suspected insurgent’s homes during a raid in Babil Province, Iraq, on March 25, 2005. Courtesy of DoD.

Suspected insurgents are assembled in a field as members of Iraqi National Guard, together with U.S. Army escorts, search the suspected insurgent’s homes during a raid in Babil Province, Iraq, on March 25, 2005. Courtesy of DoD.

In the first few days of my tour, I was assigned to interrogate a suspected bomb maker. The evidence against him seemed incontrovertible: explosive gunpowder and empty artillery shells had been found at his home. His wife had lost several fingers during an accidental explosion. This man was turned in by a known informant as a maker of improvised explosive devices [IEDs], which were being used at the time to target both U.S. soldiers and Iraqi civilians. While the evidence against him was strong, he fervently denied any involvement. He seemed sincere, and even our experts could not detect him to be lying. His explanations of the presence of explosive materials were plausible. He claimed that he, like many Iraqis, collected artillery shells, emptied them of their gunpowder, and sold the empty casings as scrap metal. The gunpowder was given to children to make fireworks.

His case was perplexing for all of us. We could not come to a consensus as to what to do with him. We did not want to release back into society a bomb maker who would then be free to kill or maim fellow Americans and Iraqi civilians again. On the other hand, we did not want to send an innocent husband and father to prison for many years. He would have been transferred to the now infamous Abu Ghraib prison.

Because the case had been assigned to me, I was the one who had to make the final decision regarding his fate. My supervisors would abide by whatever I decided. I struggled over the evidence and over his interrogation reports. Finally, in the quiet of my tent and the relative solitude of my cot, I prayed. I asked Heavenly Father to please help me make the right decision: the life of one of his children was in the balance. As I prayed for guidance, I was overcome by the feeling that we should let this man go free. I felt comfort in that decision.

The next day, I told my colleagues I thought he was innocent, and we should release him. When they asked how I had come to that decision, I hesitated. I was not sure I was ready to share my religious devotion with those hardened soldiers. But in the end, it was the only way I could justify my decision to release him. I told them I had prayed about it and felt that it was the right thing to do.

Without much hesitation and with very little fanfare, they accepted my decision, and we went on with the day’s business. The man was released and never put into prison. Later that day, one of the experienced interrogators came to me privately and said that he wished he had prayer as a tool in his toolbox. We later learned that our alleged bomb maker was indeed innocent and that the informant who turned him in had been corrupted. I’m grateful for the power of prayer and the knowledge that our Heavenly Father is with us at all times, in all things, and in all places.

BRIAN BROOKER

Brian Brooker deployed to Iraq as an Army JAG (Judge Advocate General’s Corps) attorney with the 1st Brigade of the 25th Division Stryker Brigade Combat Team from September 2008 to March 2009. While deployed to Forward Operating Base [FOB] Warhorse in Diyala Province, Brian served as the service member group leader for approximately thirty Latter-day Saints stationed with him. With authorization from the stake president in Manama, Bahrain, Brian and his fellow group members taught missionary discussions to over forty Ugandan soldiers who were stationed with them at FOB Warhorse. He has served as a first counselor in a bishopric, stake executive secretary, Young Men president, and ward mission leader.

Forward Operating Base Warhorse, Diyala Province, Iraq

September 2008–March 2009

As an Army JAG attorney, my duties included being the criminal prosecutor for my brigade of over five thousand soldiers, providing legal reviews for proposed kinetic [drone] strikes, and advising commanders on the laws of war. But my most significant responsibility was the calling extended to me by the stake president of the Manama Bahrain Stake to be the group leader over more than thirty Latter-day Saint soldiers who were stationed with me at FOB Warhorse in the Diyala Province of Iraq.

After arriving in Iraq, I pondered and prayed about our circumstances. I knew all of us would be confronted with many spiritual challenges and temptations during our deployment. We were without most of our usual support structures, such as our families, home wards, and temples. We all faced the stresses and adversity of being in a combat zone. Our new environment could sometimes be an immoral one, full of all of Satan’s trappings. The language, conversations, jokes, entertainment, and decorations in our new surroundings were often foul. With the ancient city of Babylon being only one hundred miles south of us, we were both literally and figuratively in the midst of Babylon. It became clear to me that it was my job to get these soldiers home alive—physically and spiritually.

U.S. Army soldiers examine a map found by fellow soldiers during a house search in Al Bayaa, Iraq, June 21, 2006. Courtesy of DoD.

U.S. Army soldiers examine a map found by fellow soldiers during a house search in Al Bayaa, Iraq, June 21, 2006. Courtesy of DoD.

We focused on building spiritual strength as the means for seizing opportunities for personal growth. We encouraged our Latter-day Saint soldiers to read at least one chapter in the Book of Mormon each day and to engage in additional daily uplifting study to remain spiritually nourished. I experienced Zion among our group of Latter-day Saint soldiers in a dusty, Middle Eastern desert war zone more than I ever had. We worked to lift each other’s burdens and mourn with those who mourned. Members built their spiritual strength through study, prayer, fellowship, and service.

In addition to serving one another, we worked to serve others by teaching them the missionary discussions. The Manama stake president authorized me to teach the missionary discussions to those interested in our faith and to baptize investigators with his approval. Our group taught missionary discussions to several U.S. soldiers and over forty Ugandan soldiers who were stationed with us at FOB Warhorse. The Spirit was always very strong as we met with the Ugandan soldiers in the plywood shed they built to house their prayer meetings. As many group members as possible were involved in the missionary discussions, which gave a spiritual lift to all of us. It was especially rewarding seeing soldiers who had not served missions doing well at teaching the discussions. It was a life-changing experience for them.

Our group’s faith and effort resulted in many blessings and miracles. Soon after our arrival in Iraq, we had given away all of our copies of the Book of Mormon to the soldiers we were teaching, and we had no more copies to give other investigators with whom we had appointments to teach. I had requested more, but the shipment from Salt Lake City would not arrive in time for our next teaching appointments. I prayed and asked that somehow sufficient copies of the Book of Mormon would be provided. Two nights later, I stopped by the FOB Warhorse chapel with another member of our group after family home evening. To our great joy, we discovered six red military copies of the Book of Mormon neatly stacked in our chapel cubbyhole. I sat down where I stood, overcome with the Spirit. We learned the next day that the perimeter of the FOB had been breached, but the perpetrator had not been caught. In the following days, I confirmed with group members and our chaplains that they had not placed the books in the cubbyhole. We never learned the story behind their sudden appearance.

JOSEPH CAMPBELL

Joseph Campbell was born in 1978 in Tremonton, Utah, and was raised in southern Idaho. He had no intention of joining the military, but he kept his mind and heart open regarding what the Lord wanted him to do. He joined the United States Army and worked on an air ambulance platform (medevac). He married his wife, Tawny, on July 21, 2000.

When I think back on my time in Iraq, I can tap into life lessons, friendships, and moments where I could hold my head a little higher because my crew and I were heroes to someone. I was a flight medic on a Black Hawk helicopter. We landed in mountains, deserts, and cities to pick up the wounded. There were four of us on a crew—two pilots, a crew chief, and me, the medic. I never thought I would have an Iraqi patient reinforce an eternal principal for me. Negative propaganda by al-Qaeda made us hesitant to trust Iraqi, even Iraqi Police [IP] security details. A few of the IPs believed al-Qaeda’s lies and would put on a uniform to get close to Americans or fellow policemen in order to hurt them.

Joseph Campbell sitting in a cargo bay. Courtesy of Joseph Campbell.

Joseph Campbell sitting in a cargo bay. Courtesy of Joseph Campbell.

It was a warm June afternoon in Al Taqaddum [American air base in central Iraq]. (I use the term warm loosely; it was actually downright hot.) I was at a workstation with my laptop, filling out run sheets, when a crew chief came in and said, “Campbell, urgent.” They never have to say anything else. Urgent was the highest mission priority. It means someone is severely hurt, and their lease on life is based on the time we spend rushing to a prepped aircraft and flying to their location.

When I got my 9 line [military term for calling in a combat injury] from operations, I recognized the location—Fallujah. I had been there the previous night. The patient I had helped had a gunshot wound to the head. The lucky part was that the bullet missed everything that would have killed or permanently injured him. Not all of my missions were so easy.

Now we were returning to the same place. We got off the ground in minutes. Fallujah was close. It was not long before we crossed the river into the dusty city. I could see the yellow smoke at our landing zone on the north edge of the city. Our wheels touched the small cement pad that used to be the floor of a building long since destroyed and cleared. I hopped from my window just as the dust was dissipating. Marines on the landing zone pointed me toward one of their Humvees. As I was running toward the vehicle, a litter team was unloading the patient. It was a small Iraqi policeman; he was still conscious but in a tremendous amount of pain.

The policeman had been in an explosion and was now missing his left hand at the wrist, his left leg below his knee, and his right leg above the knee. I took pride in my ability to detach myself. My patient’s problems are my problems until I hand them off, and then I could sleep soundly at night. I got in the aircraft and clipped my D-ring into the frame as the litter team was leaving. Sergeant Bigelow, my crew chief, said, “What can I do, Joe?” I told him to work on the lower extremities to control bleeding, stabilize shrapnel, and look for bones protruding from what was left of the legs.

I took my medic shears and cut his pants and belt. His blue stained uniform was shredded and in pieces. As we lifted off, the man worked to get my attention. I couldn’t read lips, but I could see that he was asking for water. I am not supposed to give water to my patients, but he only wanted me to pour water over his head. There was a warm bottle rolling around on the floor. I had used it earlier that day to clean the windshield. I took the remaining amount and dumped it on my patient’s head. He closed his eyes as the water cascaded over his face. Blood and dirt washed free from his mouth.

The rapport I have with my patients is only as good as my ability to read lips and play charades, but the man used his remaining fortitude and leaned on his elbow on the arm where only a stub remained. I read something in his eyes I had never seen in any of my patients before. I had seen it before elsewhere; it was sincere brotherly love. “Thank you,” he said in English. He then dropped back to the litter and watched the rotor blades break the sunbeams as he was left to cope with the agony of losing three limbs.

The noise of the mission faded. I was deeply touched by the example of the skinny Iraqi policeman. This was not a time I needed to be a recipient of a gesture of thanks. More pressing issues plagued his mind, yet he still thought enough of those around him to offer thanks. In all the noise I make in my life about me, how many times have I thought to offer thanks?

Later that night we got a call to take the policeman to a higher level of care. The man had clean white bandages on his transformed body. He was sedated and connected to monitors and oxygen. I looked at the humble man on the litter. He was my friend and my brother.

TOMMY D. COOPER

Tommy Cooper grew up in California and joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in April 1976. He enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps after high school and served for twenty-six years. During Operation Iraqi Freedom, he served as a logistics contractor at Al Asad, Iraq. He has served in many Church positions, including bishop, branch president, counselor in a district presidency, elders quorum president, and service member group leader in Iraq. He is the father of ten children.

I deployed from North Carolina while serving as a bishop and was stationed in Iraq with many members of my ward. Here are some of the journal entries I recorded during my deployment:

February 16, 2005—Al Asad, Iraq

A group of Latter-day Saint solders at Al Asad, Iraq, in 2005. Courtesy of Tommy D. Cooper.

A group of Latter-day Saint solders at Al Asad, Iraq, in 2005. Courtesy of Tommy D. Cooper.

While walking back from the chow hall this evening, we were passed by a large convoy of tanks returning to the base. Although we have felt some stress here, our combat ground troops have felt it most acutely. Staring back at us from the top of their tanks, eighteen- and nineteen-year-old faces showed the lines of stress. None of them laughed or joked. They just stared at us with steely eyes. It is easy to understand why these young men are succumbing to the stress of combat. A trip “outside the wire” brings the possibility of attack from every direction. And where do these attacks come from? They come from people who look like everyday citizens. Attacks can also come from everyday objects—a parked car, an empty can, a dead animal, even human beings attacking as suicide bombers. From the moment they leave the semi-security of our base until their return, they are in danger.

What keeps these young warriors going? The Marines say that it is their commitment to each other. Helping each other return home safely is their motivation.

February 20, 2005—Al Asad, Iraq

Insurgents launched a rocket attack against our base this morning. From a scene of destruction and confusion, I walked quickly to a converted chapel and followed the back sidewalk to a rundown adobe-colored building. The building is scarred with holes created by shrapnel. The room assigned for Latter-day Saint services is dusty, gray, and lit by two protruding fluorescent lights centered in the middle of the roof. The floor is covered with a large maroon prayer rug and white plastic chairs.

Upon arriving, I began making preparation for our sacrament service, and I was soon joined by other priesthood holders. Within twenty minutes after the “all clear” signal was sounded, I was on my knees reciting the sacrament prayers. For the next hour, our Latter-day Saint service member group relished the period of tranquility felt during sacrament and the opportunity to freely worship our Father in Heaven.

May 9, 2005—Al Asad, Iraq

Lieutenant Tommy Cooper is pictured on the left. Courtesy of Tommy D. Cooper.

Lieutenant Tommy Cooper is pictured on the left. Courtesy of Tommy D. Cooper.

Another Marine died today defending our base in an intense firefight. Tonight we assembled at the back end of the KC-130 aircraft, which was scheduled to take us home to safety and our families. Upon command, we came to the position of attention while members of the flight line detail carried the gray metal casket quietly up the aircraft’s back ramp and strapped it to the aircraft’s floor with thick cargo netting. We stood motionless while an American flag was draped over the casket as a silent testimony to the Marine’s ultimate sacrifice. My eyes scanned the white tag with the young man’s name on it, while the words “Having died with honor on the field of battle” echoed through my mind. This was a makeshift service in a foreign land by comrades who honored him. In the confined space of that KC-130 aircraft, we silently gazed at his flag-draped casket and faced our own mortality.

JOHN COX

A member of the Utah Army National Guard, John Cox served in Operation Iraqi Freedom from January 2005 to June 2006 as a Humvee gun truck driver, radio/

On January 5, 2006, I had some hours off between patrol missions. Though occasionally “time off” meant a recruiting security detail, this time I was not assigned to work security at the Iraqi police recruiting drive being held at the nearby Ramadi glass and ceramic works. There was a lot of recruiting going on. Due to financial hardships in their community, the opportunity to work locally as a police officer was becoming a coveted position. Unfortunately, the huge turnout exceeded expectations and was too much for the provided security. As young men were bustling to get inside the gates of the glass factory to be considered as a police recruit, someone wearing an explosive vest laden with metal ball bearings came near the entrance, pretending to be just one more person wanting a job.

Fortunately, before that murderer could get inside the gates, a military working dog smelled the explosives. The canine and handler were able to intercept the suicide bomber and prevent his entrance through the main gate. The handler, knowing full well what his dog was smelling and what that meant for his life, made the ultimate sacrifice in order to minimize Iraqi and American casualties. Though the bomber was as far away as possible, casualties after the detonation were still horrendous. A mass casualty treatment and evacuation situation ensued. It took the lives of over sixty Iraqis and a number of Americans and injured many more.

John Cox participating in a military operation. Courtesy of John Cox.

John Cox participating in a military operation. Courtesy of John Cox.

I did not know any of that. I was a few kilometers away at Forward Operating Base Ramadi busy writing an email to my wife back home. I heard a loud explosion but did not think much of it, since we heard numerous unidentifiable explosions every day. It was not until someone stopped by and told us about a great need for soldiers to donate blood at Charlie Med that I realized what had happened. I had a package for my wife that I had planned to mail at our FOB post office. I decided I would mail it quickly and then donate blood.

Living conditions in Iraq were often spartan. Courtesy of John Cox.

Living conditions in Iraq were often spartan. Courtesy of John Cox.

I received a distinct impression to rearrange my schedule. Even though the post office was closer, I should go to Charlie Med first. I recognized it as a prompting from the Spirit and obeyed. There was a long line of soldiers who were willing to donate blood to help the suicide bomber’s victims. Knowing how caring and giving U.S. soldiers are, I expected as much. I felt good, however, knowing that I had followed the Spirit to go to Charlie Med first. I took my package and proceeded toward the FOB post office, wanting to get the package mailed before my time off ran out. As I went toward the post office from the direction of Charlie Med, I went right past the helicopter landing pads, which, for safety reasons, are surrounded by high dirt berms. Two large Chinooks flew overhead and began landing.

As I walked by the opening to the helicopter pad, I saw a number of military ambulance Humvees waiting there. I stopped when I noticed there were a number of full stretchers in each ambulance. It dawned on me that I was about to witness emergency helicopter medical evacuations of stabilized suicide bombing victims who would be transported to bigger and better medical facilities across Iraq. They were diverting helicopters from all over in order to help us distribute our injured. There was only one medical soldier to move all those stretchers onto the huge helicopters. I quickly looked around and saw a group of four soldiers about two hundred meters from me. I ran to them as quickly as I could. It turned out to be a group of officers who were surprised to be interrupted by a low-ranking enlisted man. That did not matter, however, because they were the right group to talk to.

As soon as they understood the situation, they dispersed and ran to get other groups of soldiers. I returned to the concealed landing pad and began helping pick up a bloody stretcher with a severely injured Iraqi man on it. My package was left forgotten against a sandy berm. I am of a slight build but was at the head of the stretcher, carrying the majority of the injured man’s weight. A big U.S. soldier got there in time to pick up and carry the little IV bag attached to the injured man’s arm. The three of us loaded the injured man, placing him on the furthest rack up front as the helicopter crew directed us.

John Cox (standing) with two Iraqi soldiers. Courtesy of John Cox.

John Cox (standing) with two Iraqi soldiers. Courtesy of John Cox.

By now, there were enough soldiers helping at the landing pad that the helicopters were being filled to capacity. I tried to mouth a few words of comfort in Arabic to the man I had helped carry and then quickly got off the helicopter so they could take off. There were still plenty of casualties but no room left on the helicopters. I contented myself by trying to talk to the Iraqi men who were obviously confused and in pain. I got more gauze from Charlie Med to help add to the bandages that were becoming saturated with blood.

When it became clear there would be a considerable wait before the arrival of more helicopters, other soldiers began sitting down to rest against the berm. I picked up my package covered with Iraqi sand and went to the post office. I walked slowly and tried to regain my breath. After mailing the package, I got a sergeant I knew who had studied Arabic more than I. The staff sergeant, Frank Staheli, made the long trek, without complaint, from our barracks past the post office to the helicopter landing pad in an attempt to talk to more of the injured Iraqis. I am sure many of them had no idea what had happened to them. One moment they had been trying to get in the front gate of the city’s former glass factory so that they could get a police job, and the next moment American medics were towering over their broken bodies trying to slow their bleeding. I hoped that they would receive some comfort from our attempts to talk to them.

It turned out that a number of brave soldiers from our Utah National Guard unit, the Triple Deuce, were also injured that day by the terrorist bomber. It was a hard day, but I felt blessed I could have a small part to play in helping evacuate injured people perhaps just a few minutes faster. I may never know in this life what happened to the man I helped carry, nor to the other men evacuated that day. Without that gentle prompting from the Holy Ghost, I never would have had any part in helping those injured people. I will always be grateful for a loving Heavenly Father who knows the thoughts and intents of my heart and knows what paths my feet should take on the way to a dusty old post office in a faraway city.

CHRISTOPHER DEGN

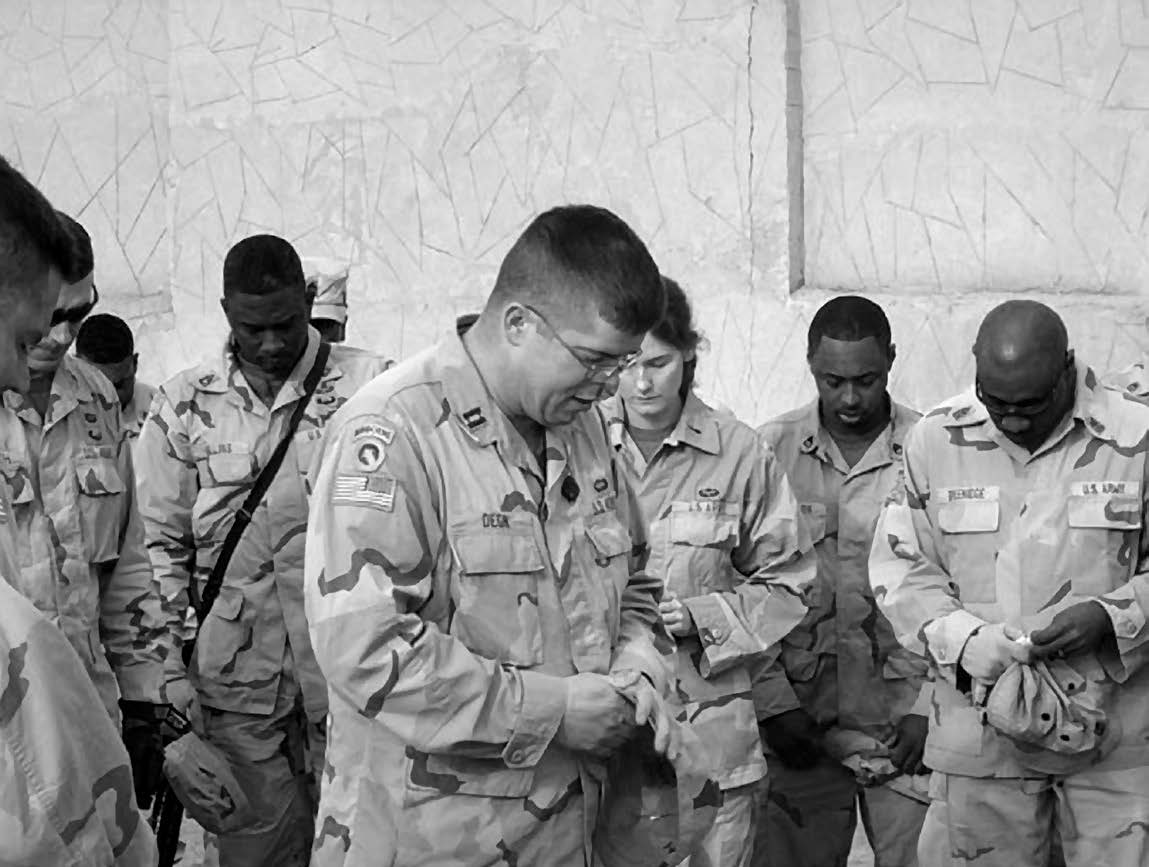

Christopher is from South Ogden, Utah, and entered the Army Reserve in November 1981 as a medical laboratory technician with the 328th General Hospital. He later graduated as a distinguished military graduate from the Army ROTC program at Brigham Young University. He earned a bachelor of arts degree in Spanish translation from BYU, a master of business administration degree from the American Graduate School of International Management (Thunderbird), and a master of science degree in counseling from the University of Phoenix—Utah Campus. After graduating from the Chaplain Officer Basic Course in 2001, he served as battalion chaplain for the 264th Corps Support Battalion (Airborne) at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, deploying with them to Bagram, Afghanistan, in support of Operation Enduring Freedom and later to Baghdad, Iraq, in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. He would return a second time to Iraq for a third combat deployment in 2006–7 with the 3rd Brigade Special Troops Battalion of the 25th Infantry Division.

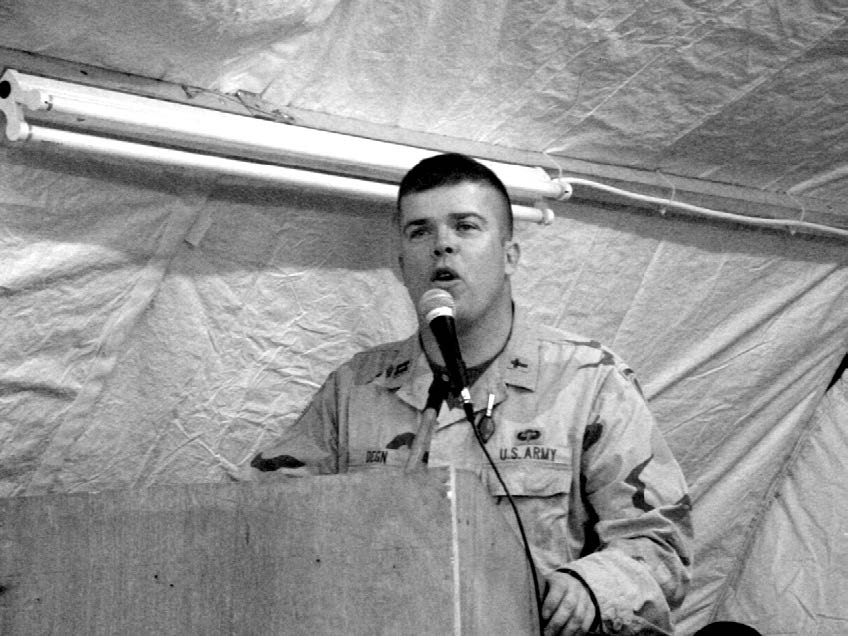

Top: Chaplain Christopher Degn is shown praying over a Humvee he was asked to bless before it “left the wire.” Bottom: Latter-day Saint Chaplain Christopher Degn is pictured preaching a Sunday sermon. Courtesy of Christopher Degn. Courtesy of Christopher Degn.

Top: Chaplain Christopher Degn is shown praying over a Humvee he was asked to bless before it “left the wire.” Bottom: Latter-day Saint Chaplain Christopher Degn is pictured preaching a Sunday sermon. Courtesy of Christopher Degn. Courtesy of Christopher Degn.

There’s an old television and radio jingle about using a well-known service to “reach out and touch someone.” One of the unique things of Operation Iraqi Freedom [OIF] that reached out and touched me and my soldiers was the improvised explosive device, or IED—basically, a roadside bomb. The IED set OIF apart from other wars in which American soldiers have given their lives. It was a booby trap device, primarily used on roadways, designed to be triggered when an unsuspecting victim touched or disturbed a seemingly harmless object. It could also be remotely triggered by an electronic device (such as a cell phone or garage door opener) when the victim entered the kill zone. For that reason, I preferred getting to the battlefield by flying in helicopters, rather than driving in convoys down the treacherous MSRs [main supply routes] of Iraq. I served with soldiers of Logistics Task Force 264 for four years and deployed with them to both OEF [Operation Enduring Freedom] in Bagram, Afghanistan (2002–3), and OIF in Baghdad, Iraq (2004–5).

In 2003, while at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, I was tasked to escort the remains of SFC [Sergeant First Class] Clint Ferrin, a Latter-day Saint soldier, back to his hometown of North Ogden, Utah, and conduct his military graveside honors there. Brother Ferrin’s Humvee had driven over an IED that used an unexploded, 500-pound Air Force bomb. The huge explosion resulting from such a hulking piece of ordnance flipped his vehicle four and a half times through the air and off the road into the river alongside the convoy route. The awful destructive force of the IED tore up his body, and his remains were gathered into what is known as a patriot roll, a green Army wool blanket closed up with thirteen safety pins. I drove out to Brother Ferrin’s home in Fayetteville, North Carolina, to help console his family. When I arrived, I immediately recognized his wife, Melinda. I had spoken in his ward a couple of times the year prior as a Fayetteville stake high councilor. This helped me connect in a powerful way to her immediate and extended family. I spoke at his memorial service held in the Fayetteville Ward, his funeral service at his home ward back in North Ogden, Utah, and at his graveside service.

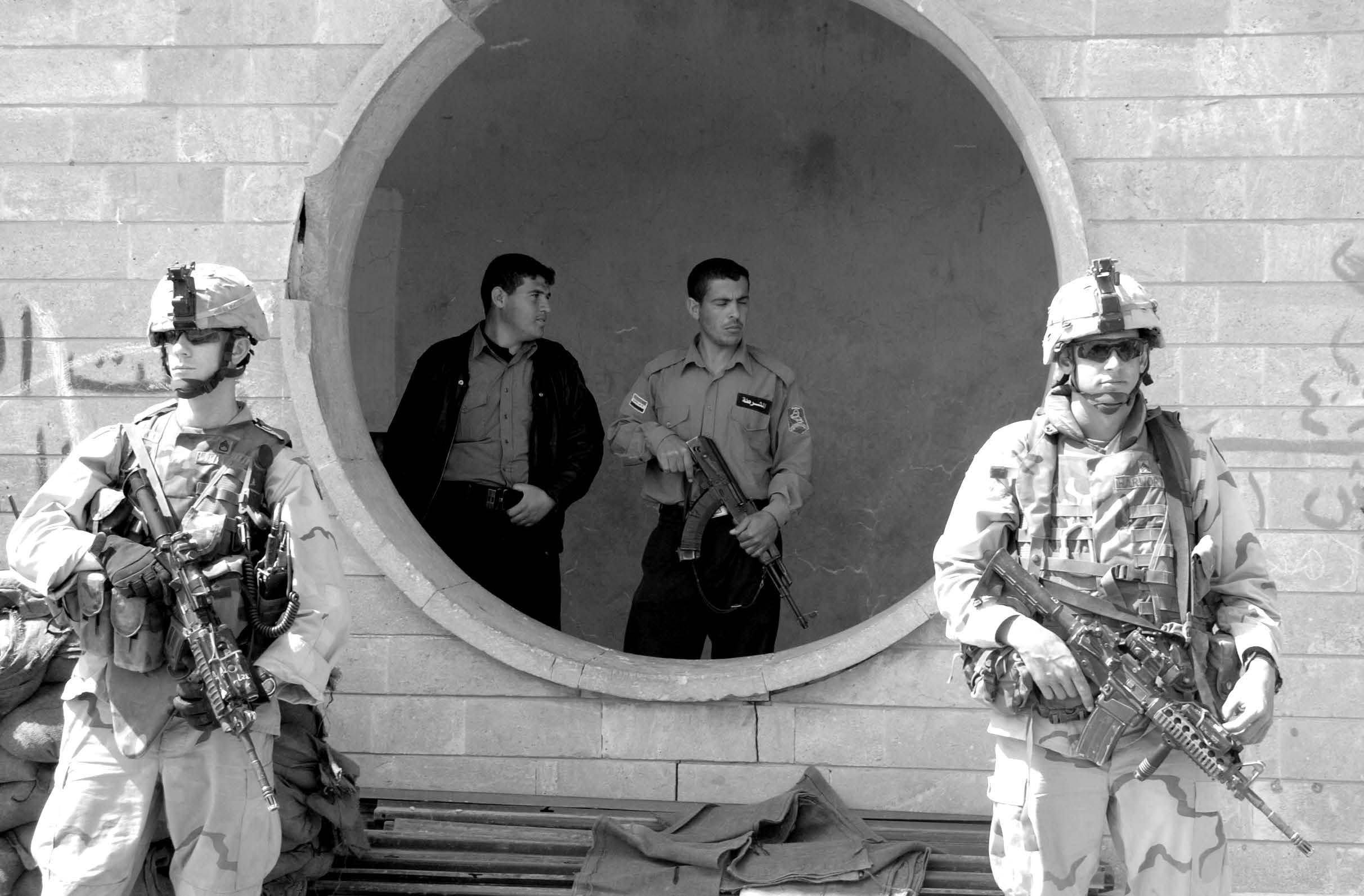

Chaplain Christopher Degn (right) is shown with a fellow Latter-day Saint, Captain Starkey. Courtesy of Christopher Degn.

Chaplain Christopher Degn (right) is shown with a fellow Latter-day Saint, Captain Starkey. Courtesy of Christopher Degn.

Some interesting things stand out in my mind from the experience. The company commander and I opened his casket with nobody else around, due to the sensitive nature of the disposition of his remains, in order to place his garments and temple packet alongside his patriot roll. For the second time in my career, I took a ribbon off my own dress uniform and placed it on his greens in the coffin because he had the incorrect number of oak leaf clusters on one of his awards. My father, Bill Degn, who lived just a few miles away from North Ogden, was able, for the first time, to come see me do my duty for God and country as a chaplain. He watched the graveside service from the sidelines, but he was somehow noticed by the deputy commanding general of the 82nd Airborne, who had been to forty straight graveside services for his troops. He walked up to my dad, shook his hand, and thanked him for raising me to do what I do. It really touched my father. I remember playing escort to the chain of command of the 82nd Airborne that took SFC Ferrin home to Utah. Having been raised in Ogden as a boy, I knew my way around. They got an exposure to Utah Latter-day Saint culture and learned what “funeral potatoes” were.

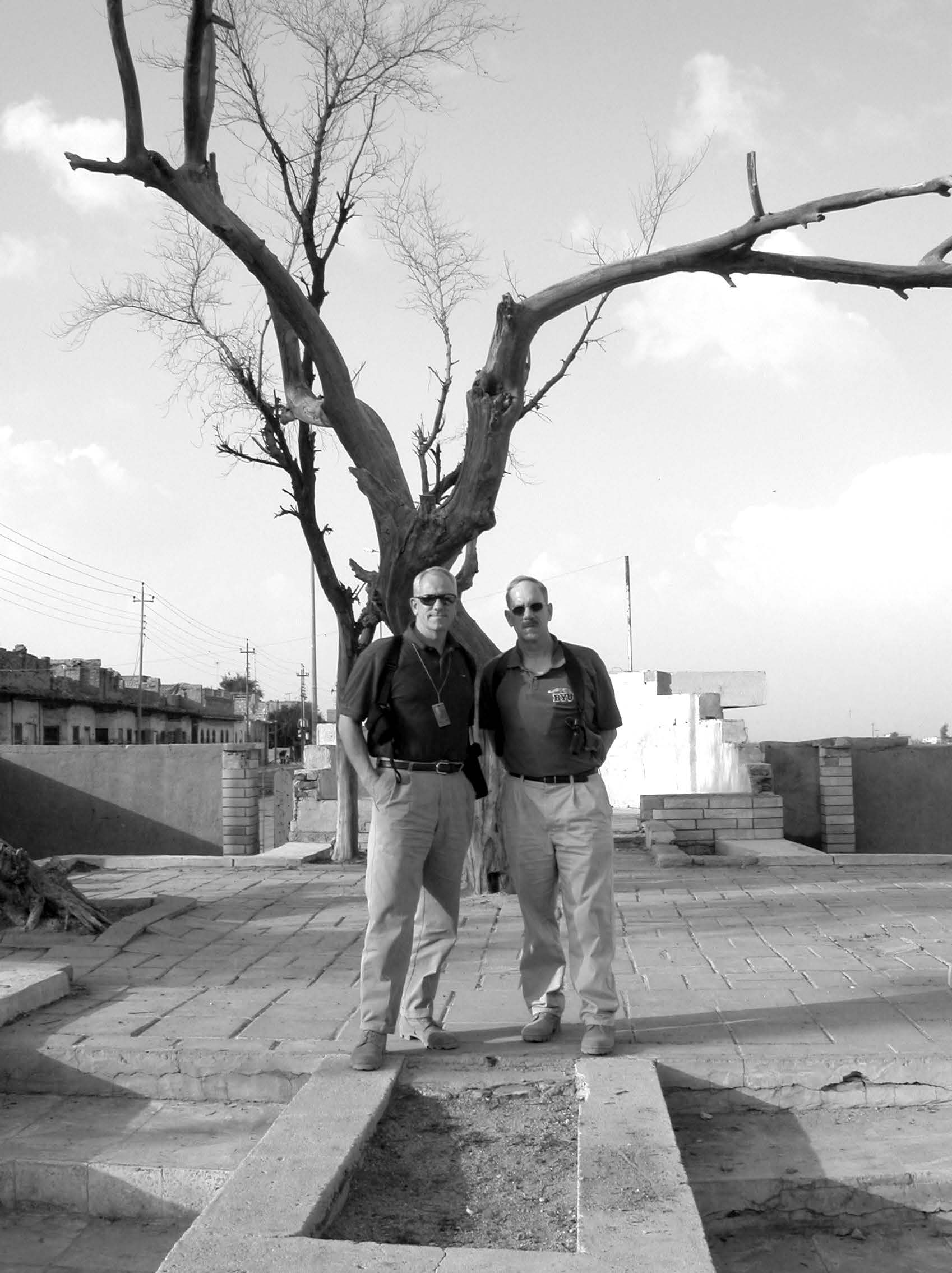

Chaplain Christopher Degn with two newly baptized members. Courtesy of Christopher Degn.

Chaplain Christopher Degn with two newly baptized members. Courtesy of Christopher Degn.

On March 16, 2005, the convoy of SGT Rocky Payne of the 497th Transportation Company (which came out of Fort Lewis, Washington) drove past the smoking, destroyed remains of a flatbed truck and received the full force of an IED set at the gunner’s level of their Humvee. Sergeant Payne rode at his usual post of gunner in that vehicle. I remember getting the call and riding with my task force commander, LTC Steve Cherry, to the Green Zone in Baghdad to minister to Sergeant Payne, but he was pronounced dead upon arrival. We were taken to the morgue and identified his remains. I gathered us all together in a circle and cried through a prayer. This one hurt more, because not only was it one of my troops, but it was one of my Latter-day Saint brethren.

Chaplain Christopher Degn is pictured leading a group of soldiers in prayer in Iraq. Courtesy of Christopher Degn.

Chaplain Christopher Degn is pictured leading a group of soldiers in prayer in Iraq. Courtesy of Christopher Degn.

I was not allowed to escort Brother Rocky Payne home to Utah like I did Brother Ferrin, but I gave him my all in the memorial ceremony we held at the Marne (3rd Infantry Division) Chapel at Camp Victory [about three miles from Baghdad International Airport]. My message contained what I called “Payne’s Points”: Be a Soldier. Be a believer. Be a friend. It was modeled loosely on President Gordon B. Hinckley’s book on the Beatitudes. These described Payne, who truly was a stripling warrior, a modern-day Captain Moroni, who enlisted in the Army after the Marine Corps put him out because of his bad knees. He had served two tours to Iraq: one as a Marine and one as a soldier. I was inspired to tell the story of Captain Moroni and his “title of liberty” (Alma 46) in my message, the only time I have ever heard the Book of Mormon quoted in a memorial ceremony. Latter-day Saint chaplains can’t get away with doing that often since we are called upon to be more Protestant or ecumenical in our quoting of scripture as ministers to a religiously diverse military. The division chaplain did not like me using a nonbiblical scripture as my theme, but the division commanding general commented to us that he loved the title of liberty story since “[1] had encouraged his fellow soldiers to remember that they were walking, talking titles of liberty in that each and every soldier there wore the U.S. flag on their right shoulder.” Rocky was a very unique soldier. He was known for his quirky sense of humor and the Army value of personal courage. He indeed deserved a unique scripture. When I finished speaking of the title of liberty, I just knew it was perfect!

Chaplain Christopher Degn serving in a medical assistance role. Courtesy of Christopher Degn.

Chaplain Christopher Degn serving in a medical assistance role. Courtesy of Christopher Degn.

Chaplain Christopher Degn conducts a reenlistment ceremony in Iraq. Courtesy of Christopher Degn.

Chaplain Christopher Degn conducts a reenlistment ceremony in Iraq. Courtesy of Christopher Degn.

Eight months later, I was able to join three leaders from SGT Payne’s company—the company commander, platoon leader, and squad leader—on a snowy December trip to little Howell, Utah, to visit his parents, brothers, and friends. They fed us. We presented Rocky’s CAB [Combat Action Badge] to them. We reminisced. We cried, and we healed. We visited the two-room schoolhouse in Howell, where one wall contains a memorial of Rocky Payne, one of Utah’s greatest sons. We visited his graveside and kneeled for photos next to “Payne’s Points,” which were engraved on the backside of the headstone. Rocky, as a teenager at a Latter-day Saint boys camp (he was also an Eagle Scout), had received the “title of liberty” award from his peers for his love of God and country. I was blessed by the trip with the confirmation of the divine inspiration of my message to his battle buddies and to his family.

MICHAEL E. FISHER

Michael Fisher grew up in Ann Arbor, Michigan. After graduating from Brigham Young University in 1996, he enlisted in the Utah National Guard. He taught high school for two years before deciding to become an officer in the regular army. He received his commission through ROTC in April 2001. He was stationed in Iraq for fifteen months during 2003–4 with the 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment and later served a second tour there. His Church experience includes full-time missionary service, Young Men president, Gospel Doctrine teacher, elders quorum presidency, and service member group leader of three separate groups.

As a first lieutenant platoon leader in Iraq, I often wondered how I would react if confronted with a life-or-death situation. We patrolled aggressively and visited often with the people in our area of responsibility. Most of the people appeared happy to see us patrolling their neighborhood. I prayed constantly that my soldiers and I would be attentive, recognize any threats, and act appropriately.

In March 2004, during my first tour in Iraq, I was supervising a tactical checkpoint in eastern Baghdad. We were searching vehicles for weapons or any materials used to make improvised explosive devices [IEDs]. There were several considerations regarding where and how we established our checkpoints. We looked for spots that made it difficult for people to turn around, turn onto a side street, or in any other way avoid our checkpoint. We considered, of course, where to station our soldiers in order to provide them with the best possible security. We also needed enough room so we could separate the vehicles we would be searching. Finally, we placed signs and orange cones about a hundred meters from our checkpoint to sufficiently warn approaching vehicles to prepare to stop.

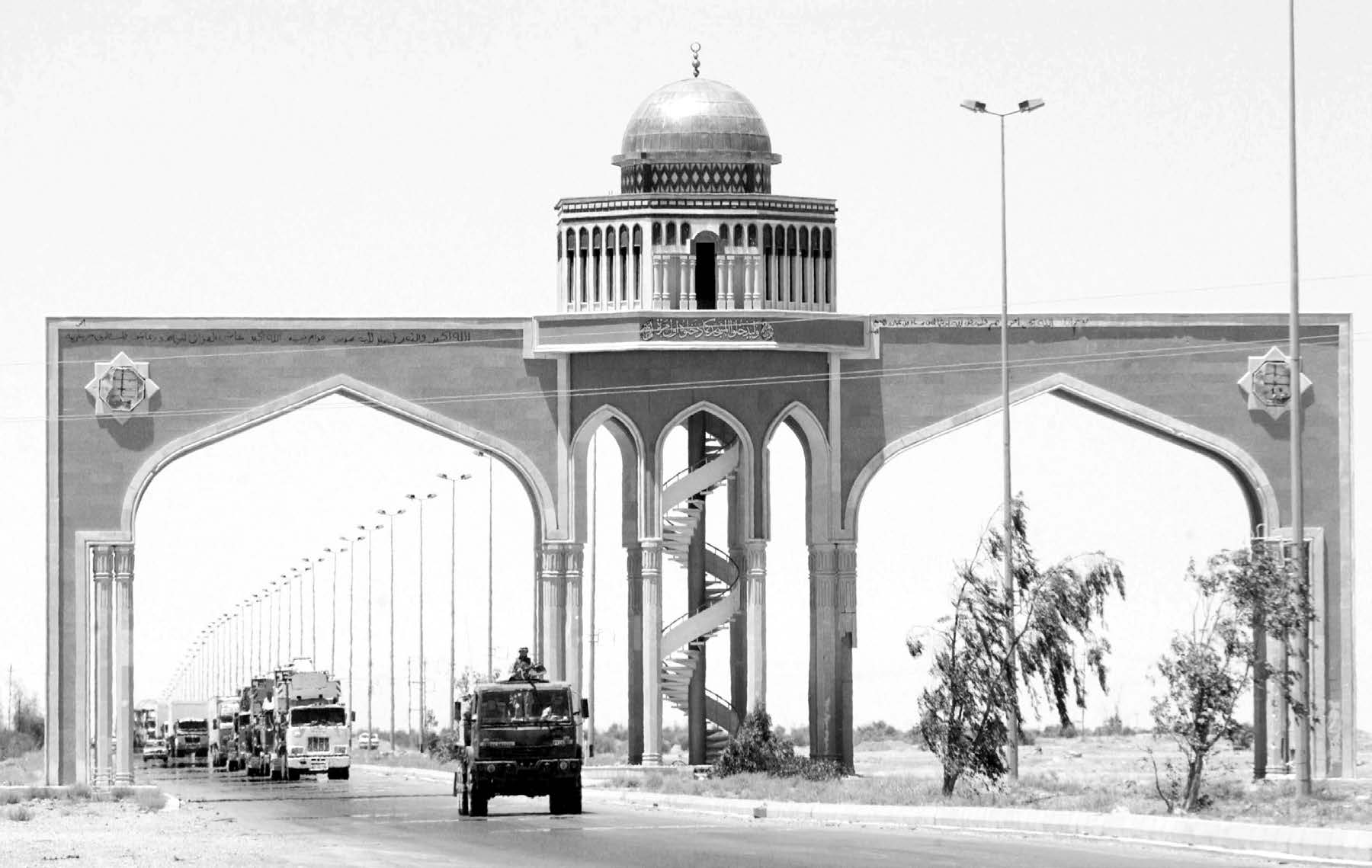

A gun truck from an air expeditionary force transportation company moves under an archway on the Main Supply Route with a convoy in tow in June 2004. Courtesy of DoD.

A gun truck from an air expeditionary force transportation company moves under an archway on the Main Supply Route with a convoy in tow in June 2004. Courtesy of DoD.

I clearly remember one night in particular. I’m sure we confiscated a handful of weapons. We usually did. But what I remember most was a Suburban vehicle and the family who almost died. Many cars on the streets of Baghdad are old, and their brakes don’t work very well. It was common for vehicles to fail to stop because their brakes didn’t work. It was impossible for soldiers to know if the driver of those vehicles was a suicide bomber, or if the vehicle simply had bad brakes.

There were few streetlights in Baghdad and none near our checkpoint. I heard tires screeching before it registered in my mind that a vehicle was approaching way too fast. The sergeant manning the machine gun next to me yelled, “Can I engage?” I quickly said, “No!” There wasn’t time to think through what the driver’s possible intentions might have been. The situation presented itself, and I just reacted. The Suburban didn’t come to a stop until it reached the search area, but as the men, women and children piled out of the vehicle, I was grateful I had refrained from shooting. I believe I reacted correctly that night because earlier that day I had prayed for the guidance of the Spirit, which saved the lives of nine people.

CHRISTOPHER FOGT

Christopher Fogt joined the ROTC at Utah Valley University (UVU) in 2005. He was commissioned in 2008 as an Army intelligence officer. He joined the Army’s world-class athlete program and competed in three Olympic Games for the USA bobsled team in Vancouver, Canada, in Sochi, Russia (winning a bronze medal), and in Pyeongchang, South Korea. He served in Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation New Dawn from July 2010 to July 2011 in Baghdad. He also served a two-year mission in the Philippines.