Veteran Accounts

Kenneth L. Alford, “The War in Afghanistan: Veteran Accounts,” in Saints at War: The Gulf War, Afghanistan, and Iraq (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 56‒192.

(Arranged alphabetically by last name)

R. SCOTT ADAMS

Scott Adams received a commission in the United States Air Force in 2008 after completing law school. He served a mission in the Philippines and received his undergraduate degree from Brigham Young University. Adams has served in Alaska; Illinois; Georgia; Washington, DC; Guantanamo Bay, Cuba; and Afghanistan. He represented the U.S. Air Force in Australia. He has served as a ward missionary, bishopric counselor, high councilor, and Gospel Doctrine teacher.

Like most members of the armed forces, physical danger is a rare experience for me. Consequently, the relative burden of my sacrifice is small. But deployments are still stressful experiences of prolonged absence. In 2010, I deployed to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba (GTMO). I left on a cloudy day near the end of the Alaska winter. I have a vivid, gray memory of the departure, waiting for the taxi next to my wife in silent anxiety while the children slept. “I wrote a prayer in my journal in those first days, which included a plea concerning my then fifteen-month-old boy: “Please, Lord,” I wrote, “bless my boy. Do not let him forget me.”

The remedies for my initial melancholy turned out to be prayer, time, and busyness. I immersed myself in work at GTMO and was captivated by it. I became familiar with each detainee—two hundred of them at that time. I knew their files and spoke with them face-to-face. I often reflected on the idea from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s writing: “If we could read the secret history of our enemies, we should find in each man’s life sorrow and suffering enough to disarm all hostility.” Frequent, face-to-face interaction did indeed melt away any inner hostility I might have felt. In its place came the surprising realization that these men suffered sorrow much like my own: longing for home, anxiety for their children, and a desire for freedom.

It is often said the law of war is founded on three fundamental principles—necessity, humanity, and honor—and that honor, the principle that animates all other rules of war, is based on mutual respect among combatants. That seems rather idealized today, but I learned at GTMO that mutual respect is possible, even with extreme enemies.

I spent one afternoon with a detainee, trying to convince him to write again to the federal courts to request an attorney. He kept sending mail to the wrong addressee, and I was trying to show him how to address his letter properly. While working with this man, I recall being struck by his youth. He seemed frail, vulnerable, and was certainly younger than me. This same detainee claimed to have converted to Christianity. The claim was met with skepticism, but I had no reason to doubt his sincerity. He spent long hours reading his Bible, and his conversion came at great sacrifice to him, resulting in isolated confinement for his safety. I recall sitting with him while he affectionately stroked his Bible as if it was a soft treasure. While at GTMO, I ensured the detainee library included a copy of the Book of Mormon. I attended a small, eclectic branch, worshipping near the noisy evangelical group in the next room.

R. Scott Adams is greeted by his children as he returns from Cuba. Courtesy of R. Scott Adams.

R. Scott Adams is greeted by his children as he returns from Cuba. Courtesy of R. Scott Adams.

I found a broad spectrum of behavior and attitudes among the detainees. At one end of the spectrum were men like Khalid Sheikh Mohammad, a principal architect of 9/

We were in the business of releasing detainees, and I interviewed each one shortly before they were released. One man played a vigorous game of soccer in the recreation field the day before his release. When he learned there would be photographers documenting his return, he demanded a wheelchair—claiming that as a result of many years of torture, he could no longer walk. Many detainees were dishonest and made claims of abuse. But others were quiet, complacent men who spent their days napping, reading Harry Potter, and taking art classes.

Throughout my time at GTMO, I longed to be home. I clearly recall walking through the airport in Alaska, desperate to look like a returning hero. I had spent half my toddler son’s life away from him. But his sisters’ squeals of “Daddy!” warmed him to the idea of a returning father. I did not believe the frequent reminders that postdeployment readjustment can be difficult. It sounded like a warning that heaven will initially be very hard, but I was surprised to find the reacquainting period was a significant family challenge.

* * * * *

The second time I deployed was easier. We were living in Georgia when I left for an eight-month deployment to Afghanistan in 2013. The children had grown some, and we had a new son. This time the entire family took me to the airport, where we embraced on the sidewalk. I recalled a famous quotation from Seneca—“Wretchedness is a sacred thing.” The collective weeping of a young family was, for us, a sacred experience that drew us closer together.

Afghanistan included some of the risks many people imagine, including indirect fire rockets landing in random spots. However, I never felt anxious or in danger at any time. It was a divine blessing, a tender mercy. It felt normal, even comforting, to take the sacrament in a concrete room late on a Sunday night, with service members in uniform who had weapons slung over their shoulders.

I worked in Afghanistan as the Judge Advocate, or JAG, for an Air Force combat wing. That meant conducting investigations and courts-martial, resolving funding issues and other routine business. Each Saturday I was given the morning off. During that time, I taught an English class at a local school for young men or volunteered at a local hospital. One Saturday I brought a box of blankets to donate at the hospital. This was an unusual donation. I typically brought crayons and paper or stories to read to the children. But when I opened the box of blankets, I quickly found myself overrun by women in burqas, pushing me aside, desperately grabbing the blankets. It was a sobering look at the faceless destitution of Afghan women.

I became very attached to the people at the hospital and the young men in the school. It often struck me as remarkable that despite the ostensibly important office work I did in that theater of war, the most meaningful time in any given week was always the three short hours I struggled to teach English. Because I had no materials and no experience teaching English to foreigners, I taught much the same way I used to teach Tagalog to young American men in the Missionary Training Center.

While I was in Afghanistan, the Afghan government held elections. Voting was risky, and many polling locations were attacked. I was amazed at the courage and patriotism of those incredible young men when I learned every one of them had risked his life to vote. During my final class, we parted with tears. I still keep in touch with many of the young men, who continue to fill me with optimism for the future.

I returned home again desperate to appear as a returning hero but ultimately content to slip quietly back into domestic life. I found pleasure in anonymously taking the sacrament in a large chapel with a shirt and tie, next to restless children. Like my mission, I am grateful for the deployment experiences but might be reluctant to repeat them. In the end, it was prayer, church, and family that provided me the necessary strength to endure.

CHAZ ALLEN

Chaz Allen grew up in a loving home of eight children and served a mission in Belém, Brazil. He attended the United States Military Academy and was commissioned as an Army Aviator. He later became a scout recon pilot of the OH-58D Kiowa Warrior and served as a platoon leader and troop commander in Afghanistan, supporting Operation Enduring Freedom from 2010 to 2011 and 2013 to 2014. His wife and five children enjoyed living at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, while he served as an instructor. He has served as a Primary teacher, ward mission leader, and Young Men president.

Emails sent from Kandahar, Afghanistan

April 16, 2010

Looking a little like Darth Vader, Lieutenant Chaz Allen prepares to fly another helicopter mission. Courtesy of Chaz Allen.

Looking a little like Darth Vader, Lieutenant Chaz Allen prepares to fly another helicopter mission. Courtesy of Chaz Allen.

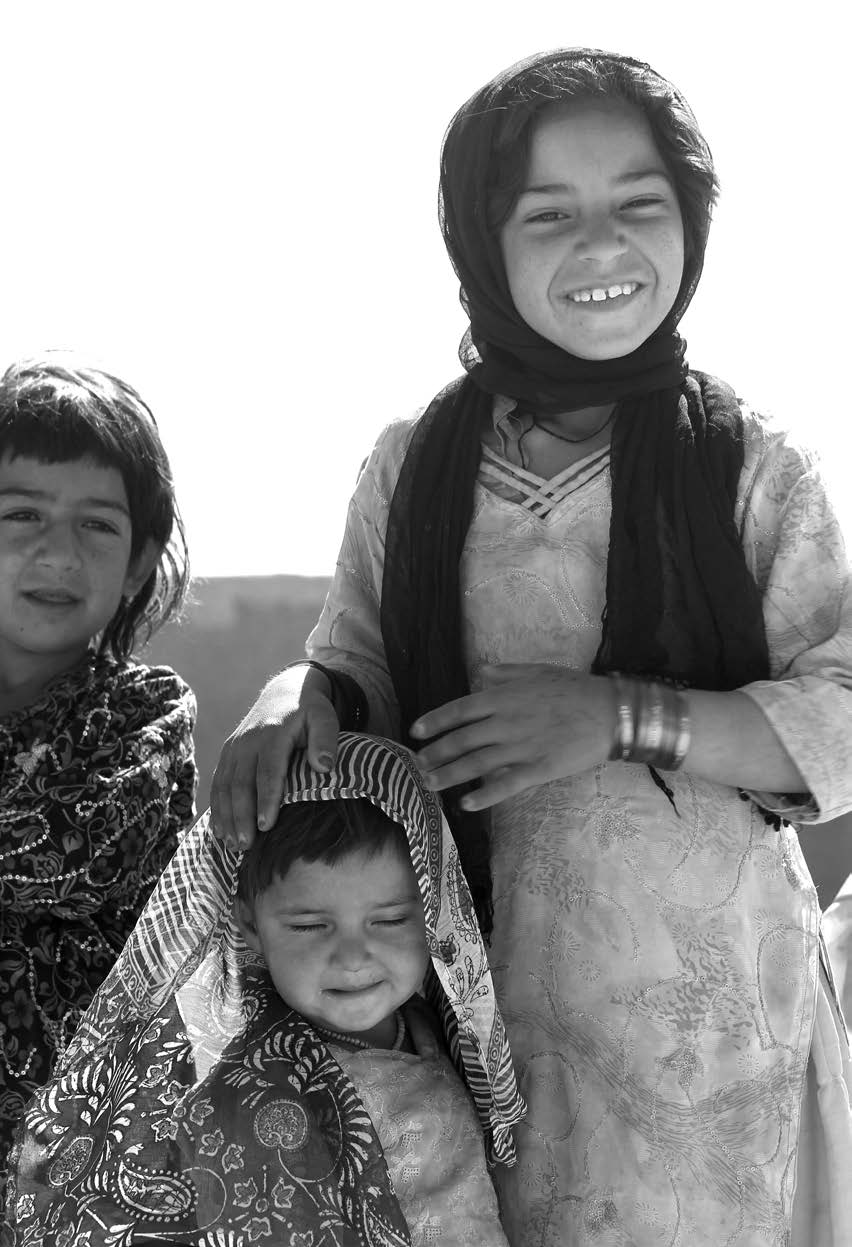

Every day, little boys will gather near the fence line of our base and petition for bottled water or treats from soldiers. We are restricted from approaching the fence or giving things to them because the enemy we fight is so insidious that it would easily enlist a child as a suicide bomber or human shield. I’m sure most of those boys are innocent and curious, but the reality of this kind of warfare won’t allow for interaction with them. There are some big hearts in our troop, though, and we do try and show some affection to the local little ones. On today’s flight, we brought some “candy bombs” with us: about six bags of a variety of candy that our team threw out the door at little kids so they could have a treat from the Americans and enjoy chocolate or bubble gum for probably the first time. The children were curious at first, and some were scared of us when we flew over; but when they realized we meant them no harm, they started swarming to the candy as we threw it. I particularly enjoyed throwing it in the direction of some little girls: they were very shy and looked like they were going to miss out, but they burst out of their reserved posture to try and grab up some of the candy I threw near them. Grandma Allen challenged me to get some treats to the kids of this rough place, and as I saw those smiling faces below our skids, I couldn’t help but smile and wave right back at them. It’s hard to believe that a lot of those boys will be enlisted to fight against us. Right then, all I saw were some beautiful children of God who were embracing the simple joys of youth.

August 16, 2010

I had been asleep in my metallic cube of a room for about two hours when I started hearing the whir of the sirens that warn of impending rocket and indirect-fire attacks on our airfield. I was tired from a night full of flying in our area of operations and considered just ignoring the sirens and rolling over. But, being a platoon leader, I dragged myself out of bed, hopped off my bunk, slapped some sandals on my feet, and put some sunglasses on before leaving the dark comfort of my air-conditioned room for the 120-degree heat and blindingly bright light outside. As I started checking rooms and getting accountability of my men, I noticed a change in the siren’s tone. I strained to hear a crackling voice over the loudspeakers: “KAF [Kandahar Airfield] is under direct attack—seek shelter.” That was a new one for me. I knew what an indirect attack was like, but a direct attack meant the perimeter was in jeopardy, and we might have some uninvited guests. I ran back to my room and loaded up my M9 Beretta [pistol]. By now, many of our troopers were coming out of their rooms like zombies (that’s what the night shift can do to you), and everyone was looking for some answers. “Get back in your rooms, lock and load,” I ordered. “Be ready to gear up and launch if things get crazy.”

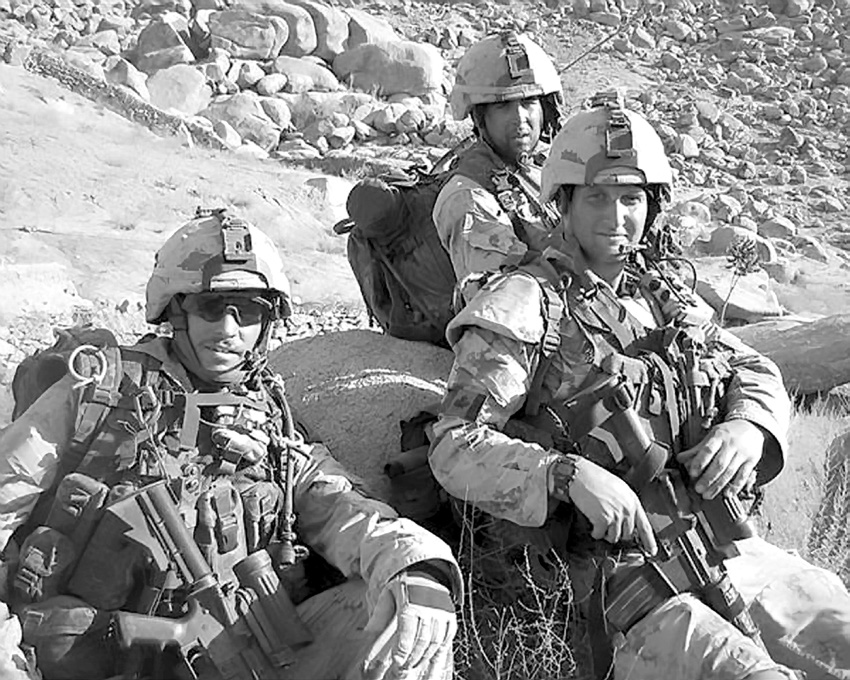

First Lieutenant Chaz Allen’s Army aviation unit at Kandahar, Afghanistan, in 2010. Courtesy of Chaz Allen.

First Lieutenant Chaz Allen’s Army aviation unit at Kandahar, Afghanistan, in 2010. Courtesy of Chaz Allen.

On our northern perimeter, a large group of enemy insurgents had snuck up within a few hundred yards of the perimeter and were charging the fence line. Their goal was to breach the wire with suicide bombers and open up a channel for their men to pour in in order to disrupt and terrorize the airfield. They were well equipped with small arms, RPGs, and enough explosives wrapped around them to make a crater the size of a swimming pool. When they charged the wire, the tower saw them, initiated the sirens, and began engaging them. I don’t know what happened, but as the kamikazes neared the wire, one of the men “prematurely detonated,” vaporizing himself and blowing apart all the rest of his assaulting cohorts. In one instant, their attack was over; their lives ended.

At the same time, we had a scout weapons team (two Kiowa OH-58Ds, a lightly armored reconnaissance helicopter) coming back to our airfield after test-firing their weapon systems. They showed up seconds after the blast, just as the chunks of dirt, flesh, and broken AK-47s settled to the ground. The team confirmed that there were no more insurgents in the area and that the immediate threat in that sector appeared to be over. The rest of the day was quiet, but the attack was a clear portent of an emboldened enemy pushing their offensive even as we push ours. I was startled to think that our airfield wasn’t the impenetrable fortress I’d grown accustomed to thinking it was. I realized that out here, there is no such thing as being “safe and sound.”

December 17, 2010

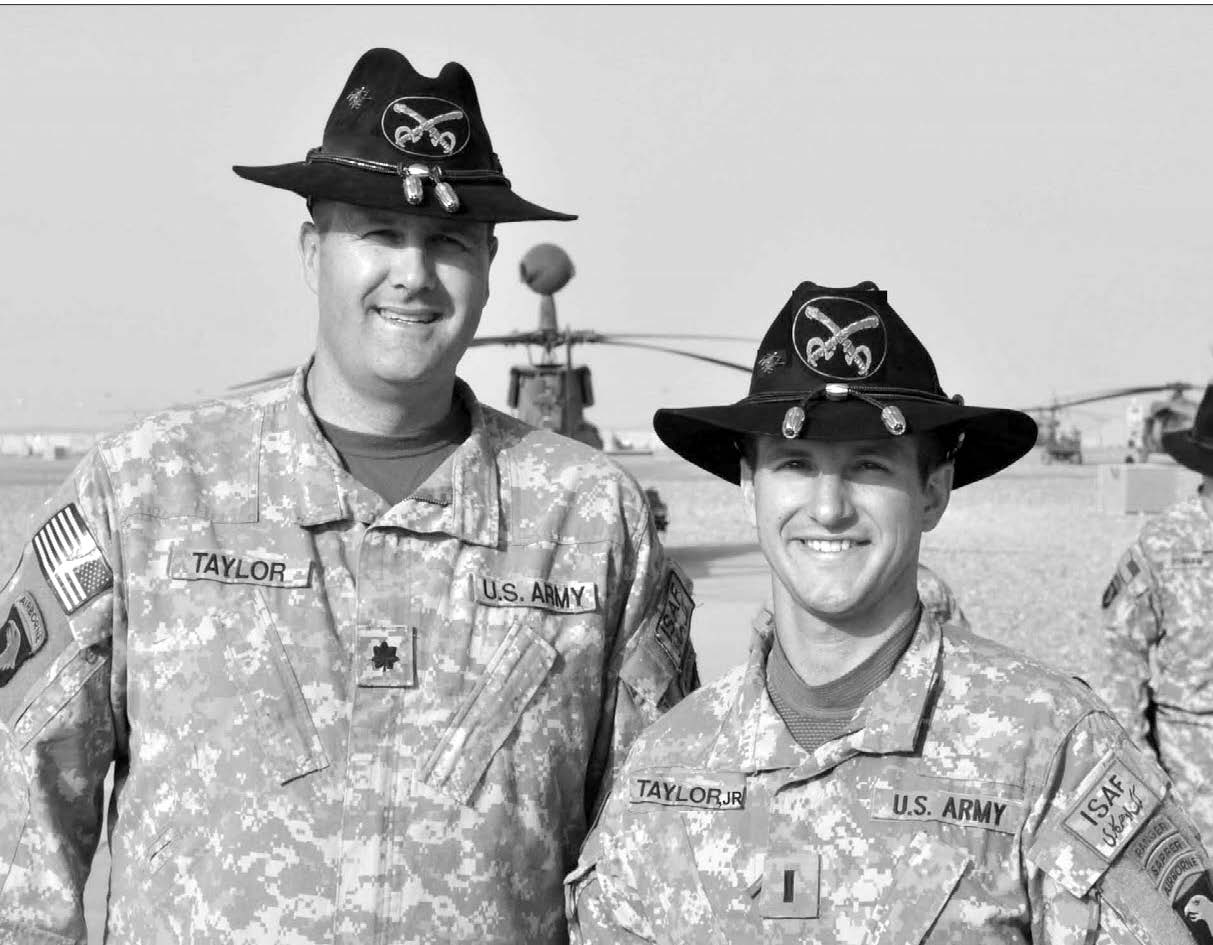

While zooming past dried grape fields and mud huts, my squadron commander, Lieutenant Colonel “Hank” Taylor, one of three Latter-day Saints in the squadron, asked, “So how is Sara doing? Are you doing a good job keeping in touch with her and your boys?” (Our commander knew every one of his soldiers by name and likely every spouse’s name as well.) I responded that things were great at home. I have been greatly blessed with a wife who is both independent and fully competent in handling all the issues back home, and he shared with me how his family was doing.

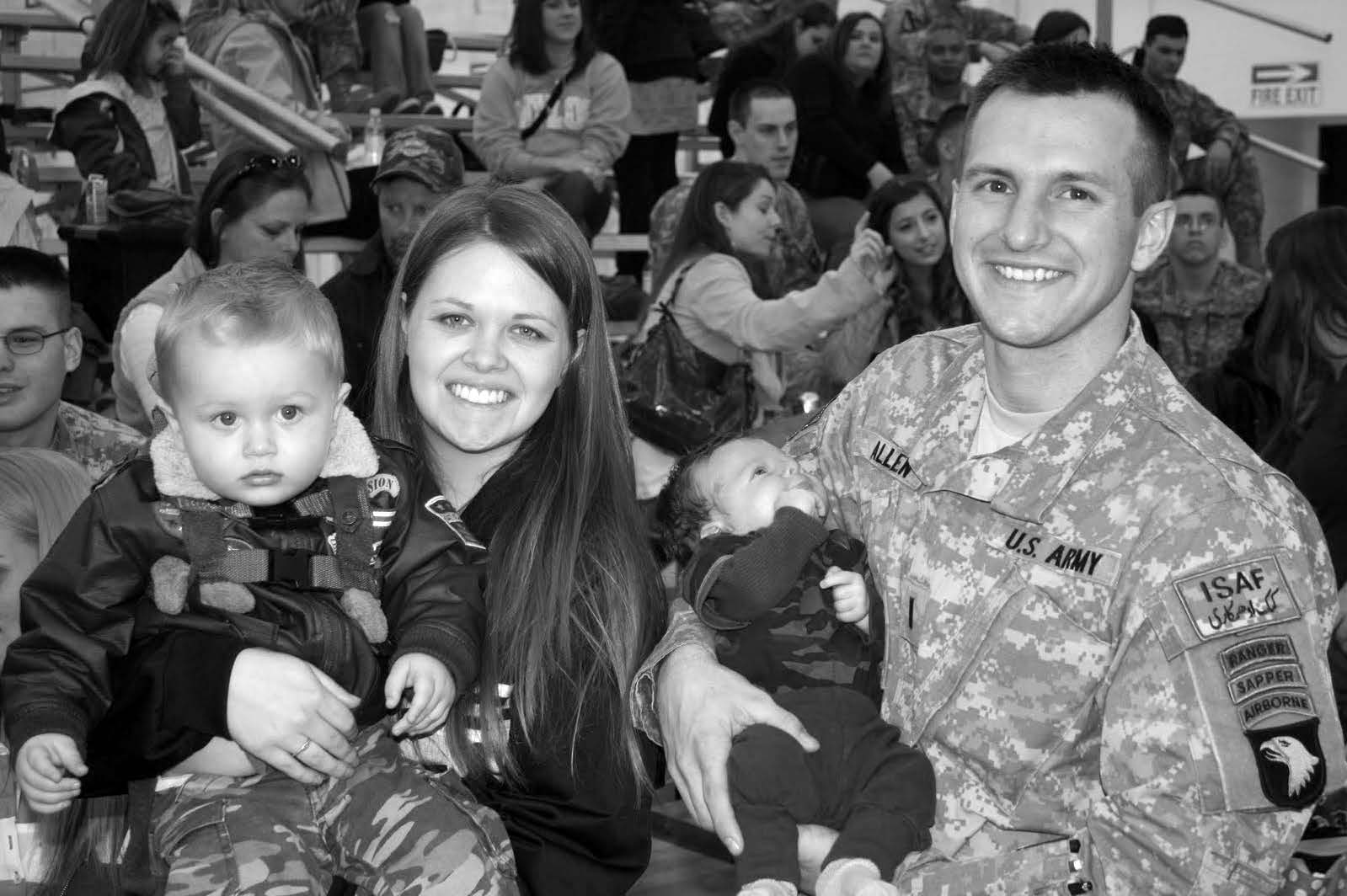

Lieutenant Chaz Allen holds his son prior to deploying to Afghanistan in 2010. Courtesy of Chaz Allen.

Lieutenant Chaz Allen holds his son prior to deploying to Afghanistan in 2010. Courtesy of Chaz Allen.

As the flight continued, we provided area security for the ground elements that were holed up in an abandoned compound. While flying overhead, we started hearing the soft popcorn-popping sounds of what could only be small-arms fire. The ground element crackled over the radio, “We’re taking fire—it looks like it’s coming from the east at 150 meters! One of our guys is hit; we’ll need a medevac!” I looked out of my door to see the camouflage-clad soldiers below taking cover behind the thick mud walls of the compound and returning fire with well-aimed shots. The tracers raced to and from the different fighting positions like a laser light show, and amidst this chaos our team set up for attack runs.

The lead aircraft nosed it over and unleashed a fury of .50-cal rounds that shredded the enemy’s position in a tree line. Our aircraft came in directly behind them and thundered more incendiary rounds into the position. Then the Apache came in for the final blow and fired 30mm high-explosive rounds until the position was nothing more than a smoldering mass of dust and debris. We banked our aircraft around to ensure that there were no enemy personnel sneaking away from the engagement site and then began thinking about how we were going to secure the landing zone for the medevac pickup. We instructed the ground force to pop smoke, and they marked the LZ [landing zone] with the billowing clouds of green smoke from a smoke grenade. As the Black Hawk came in for its final approach, we dropped altitude and set up to cover the site where the enemy would likely be. While inbound, the enemy forces did their best to shoot us down.

The medevac bird picked up the casualty and egressed [exited] in a safe direction while we focused our attention on the elusive enemy. We searched for the shooters but were unable to regain contact, so we covered the friendlies nearby until they exfilled [withdrew] from their positions and moved back to their combat outposts.

When we refueled, we checked for any aircraft damage. To me, it seemed that surely there would be scars along the thin metallic frame of our aircraft—at least shards of shrapnel in the blades. To my utter surprise, there was not one mark on our entire aircraft: We had come through the firefight unscathed—both ourselves and our airframe. I knew that Heavenly Father was mindful of me, and he had taken care of our team.

December 17, 2010

The Christmas spirit is a very powerful thing. I know for me, though, it was a bit challenging to get into that oh-so-desired Christmas spirit this year. When I returned from R&R [rest and recuperation], everything seemed quite bleak and depressing. I had just returned from fifteen of the most heavenly days of my entire life. I enjoyed the unspeakably wonderful reunion with my incredible wife and adorable boys and met up with so many loved ones that my heart was brimming with joy; we did everything we had meticulously planned and then some. I was blessed with two of the most perfect weeks a man could ever hope for. I was surrounded by everything and everyone that was important to me. When those final foreboding days closed in on me and I knew that I would be leaving soon, I would catch myself staring off into space with a glum look, allowing the overwhelming weight of homesickness and loneliness to slowly bear down on me. My shoulders would literally sag under the weight of it.

Chaz and Sara Allen comfort two of their children prior to Lieutenant Allen’s departure for Afghanistan.

Chaz and Sara Allen comfort two of their children prior to Lieutenant Allen’s departure for Afghanistan.

Courtesy of Chaz Allen.

When the time came to go to the airport, my heart seemed to beat slower than normal, begrudging me for leaving my family yet again. I was in my Army combat uniform, and Sara and I broke protocol to hold hands, hug, and kiss every chance we had in those last few minutes.

When it was time to provide the flight attendant my ticket and offer a single, final goodbye, I turned to Sara and gave her and Marek, my son, the biggest bear hug I could muster. As I pulled back, I saw Sara’s eyes brimming with tears as she strove to be strong. Her soft voice broke as she said, “I love you, Chaz,” and right there my tough-guy image shattered and the floodgates opened. The vision of my beautiful wife blurred as the tears poured down my cheeks, and I gave them both a final squeeze, saying, “I love you, Sara. I love you, Marek. I’ll miss you so.”

My heart felt broken, and my legs felt so heavy that each step took enormous willpower. Looking back, I noticed that the man behind me and the ones behind him were crying too. With a gentle voice, he said, “Thank you for your service, son,” and patted me on the shoulder. When I sat down in my seat, nearly every single person that passed by me gave my shoulder a pat or a squeeze and muttered a word of encouragement or thanks. Later, I learned that Sara, at the gate door, received hugs and encouragement from passengers who also had tear-streaked cheeks. I was inspired by the support of my brothers and sisters on that flight and know that the image of Sara with Marek in her arms as we shared that last goodbye will be forever in my heart. Those next few days were filled with lonely flights and long nights in Kuwait while I made my way back to Afghanistan. After arriving here, I was met with some smiles and a few “welcome backs”—but most of the men knew there was little “welcome” about returning to combat.

February 3, 2011

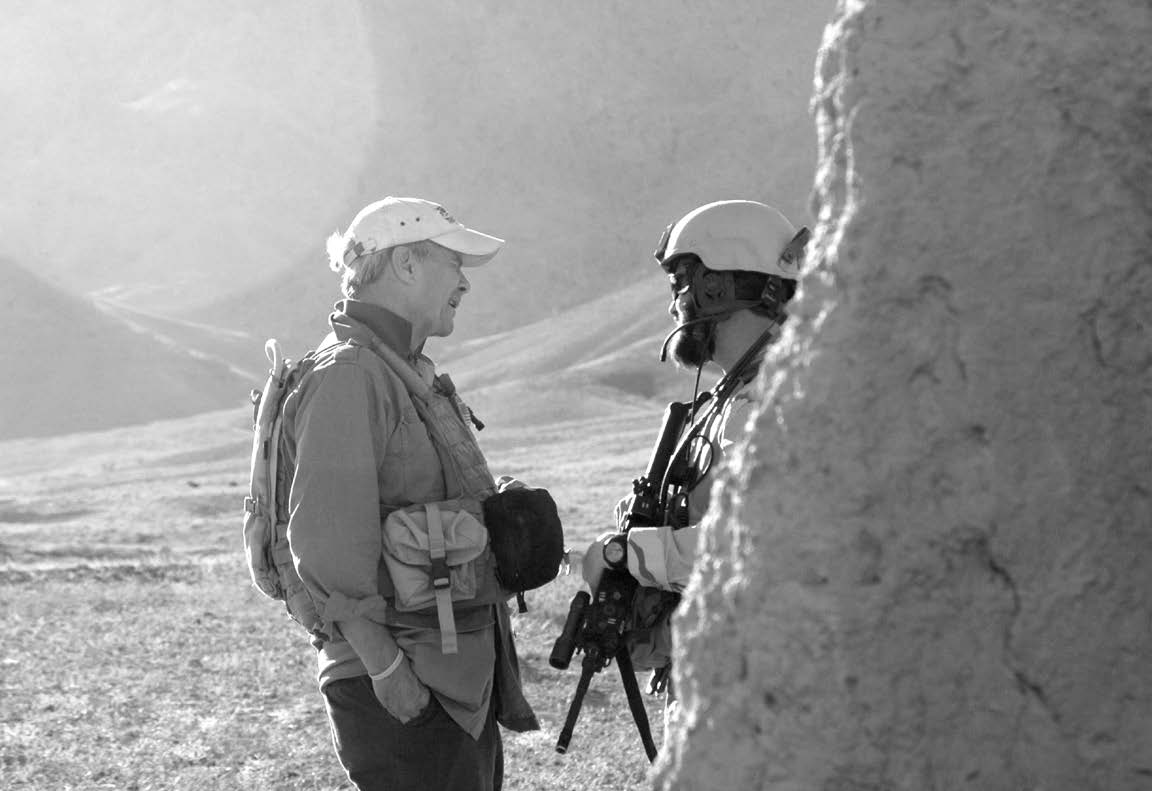

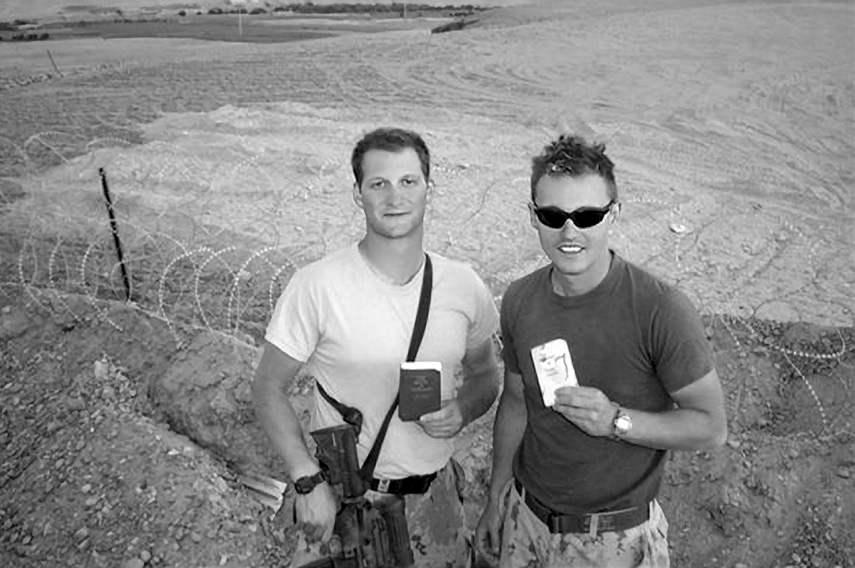

First Lieutenant Chaz Allen’s commander in 2010 in Afghanistan was another Latter-day Saint, Lieutenant Colonel Hank Taylor (left). Note that Lieutenant Allen’s nametag reads “Taylor, Jr.” Courtesy of Chaz Allen.

First Lieutenant Chaz Allen’s commander in 2010 in Afghanistan was another Latter-day Saint, Lieutenant Colonel Hank Taylor (left). Note that Lieutenant Allen’s nametag reads “Taylor, Jr.” Courtesy of Chaz Allen.

“Long Knife Two-Six, this is Chaos Nine-Five Romeo. We are in heavy contact. Requesting air support. Over!” Fifteen kilometers away, I brought my hand to my headset to further press my ear cup and speaker to my ear. I channeled my radio to the distressed voice’s call and pressed my push-to-talk switch. “Chaos Nine-Five Romeo, this is Long Knife Two-Six. Understood last transmission. Request position, current sitrep [situation report], and enemy location. Over.” I looked to my copilot who gave me a knowing nod. A second later, a transmission breaks across our headsets, filled with the shaking voice of the forward observer as he passed us his grid location and as much as he knew about the enemy firing on his position. I pointed my finger out the door in the general direction of the contact and transmitted to my team that a TIC [troops in contact] is taking place fifteen klicks to our south and that we are moving in now—weapons hot. I am the air mission commander on this flight and know that every second we take in getting to our men on the ground could spell the difference between life and death. I directed our scout weapons team to drop low and cut above the treetops and mud huts, flying NAP [near as possible] to the earth to mask our rotor noise as we were inbound and allow us to find, fix, and destroy the enemy.

Suddenly, our radios crackled with the panicked voice of our forward observer: “Enemy positions now to our north and east, two hundred meters. One of our men is hit. We’re assessing the wounds. They are bounding on us!” In the cockpit of a Kiowa Warrior, there is an unusual serenity during firefights. The sound we hear is attenuated by two separate, effective layers of soundproofing in our helmets, and radio transmissions come across incredibly clear above the muffled rotor noise and the pops and booms of bullets and explosions. We are taught to bring calm to the situation when things start getting rough. In my seat behind the flight controls, I am detached enough from the fight to keep a clear head but can also recognize that things are heating up significantly and that the pressure is on our soldiers to hold their ground.

I informed Chaos Nine-Five we were thirty seconds out and requested he fire M203 smoke into the enemy position to mark it. We were inbound with .50-cal [machine guns] and high-explosive rockets. I can distinctly hear the relief in his voice as he returned with “Roger. Smoke’s out.”

My lead aircraft pulled back on his cyclic and initiated an aggressive climb to gain altitude, bleed off airspeed, creating a gun-to-target line that would maximize ballistic effects. As soon as he bumped up, we began our bump as well. I could hear the thunder of his .50-cal through my headset. As we nose over our aircraft, Sharp let loose with two rockets and then ripped into the enemy position with the .50-cal M3P machine gun, which is hard mounted to the airframe about three feet behind the left seater’s position. The gun’s muzzle is almost directly outside the left seater’s door. When that weapon fires, the concussion caused by hurling those armor-piercing incendiary rounds two thousand feet per second literally causes your teeth to chatter and jostles the entire helicopter, even in its most stable dive profile.

Our team’s .50-cal run was successful in suppressing the northern enemy position, and we moved in on the enemy to the east. We banked our helicopters over until the earth was almost all we could see and rolled out, setting up our inbound attack run. Our lead dove in on the enemy and fired a short burst of .50—too short—and then followed up with rockets. As we were coming inbound, the lead bird called on our internal frequency: “Our .50 just jammed. We’re rockets pure.” We dove in on the enemy, and the ground element informed us that the bad guys moved into a grape hut set up like a bunker. We adjusted our run and began a lethal burst of .50-cal that stitched through the mud hut’s roof, setting the reeds and grass aflame. At the end of our burst, I heard Sharp curse and perform a break turn out of our inbound dive. He looked over to me and said, “Sir, can you see if the .50 is jammed? I’m getting no response!” I stuck my head out the door and saw that the belt-fed weapon’s control arm was stuck midway through its race and that our .50 was now out of the fight as well. In this firefight, both of our fire-breathing dragons were down. We were now limited to two seven-shot rocket pods each, and we had both already fired two of our folding-fin rockets.

Chaplain Mark Allison (center) is shown leading a group in prayer before a mission. Courtesy of Mark Allison.

Chaplain Mark Allison (center) is shown leading a group in prayer before a mission. Courtesy of Mark Allison.

The ground element reported taking further fire from the south and said that since we are overhead, they were going to try and assault through the enemy position and capture the enemy hunkered down in the grape hut. Knowing that our rockets would not be enough to support those Joes, I called up our sister team that was operating a couple of klicks away and requested his assistance for a hasty battle handover.

Now the camouflage-clad gladiators below us are moving fiercely forward over the terrain, determined to get their hands on the men who injured one of their brothers-in-arms. As the inbound team sped to our position, the ground element requested another attack on the grape hut. Our lead fired off all his rockets but one. (You always keep some munitions aboard to ensure you’re armed while en route to the forward arming and refueling point.) As we approached, Sharp pressed the fire switch and a rocket thundered out of our rocket pod. He pressed it again—once, twice, three times—with no result before breaking away. As we broke, Sharp told me that the number four, three, and two rockets didn’t recognize the fire command and that we have only one left.

I knew the ground element needed cover now more than ever. I could see them bounding into certain enemy fire. Our fuel was critical, and our .50s were down. We had only one rocket that might not even fire, and our ground element was in the most vulnerable moments of its assault. It was a moment of crucial importance, and without even thinking, I deviated from protocol and requested my inbound team to pick up my six and follow us in. “Look for my mark,” I declared. “We’re marking with rockets. Fire directly on our mark. Friendlies inbound and potentially danger close.”

We moved in, unleashed our last rocket, and broke away. . . . We witnessed, in reluctant jubilation, as the rounds thrashed apart the enemy grape hut and left our friendlies unscathed. I passed the battle into the capable hands of our fellow air cavalry scout troopers, and we made a break for the nearest refuel point. As we moved away from the battlefield, I could still hear the chatter on the radio as the ground elements moved in on the objective area. Before we finally signed off, they offered their appreciation.

At the refuel point, we had our .50s worked on by our crew chiefs and got our rockets checked out. There was no explanation for why our last rocket fired when the system was already down, and I am not sure what drove me to mix teams and risk air-to-air collisions in a firefight. Now I realize that the whole time I was up there, ideas came to me suddenly and smoothly, and although I did not ever hear a distinct voice directing me where to go and what to do, I felt guided and somehow looked after. It was one of many unique and now treasured experiences I have had with the Holy Spirit this year in which he assisted me in calling crucial information to remembrance, comforted me, and led me to safety.

MARK ALLISON

See Mark Allison’s biography in the Gulf War section.

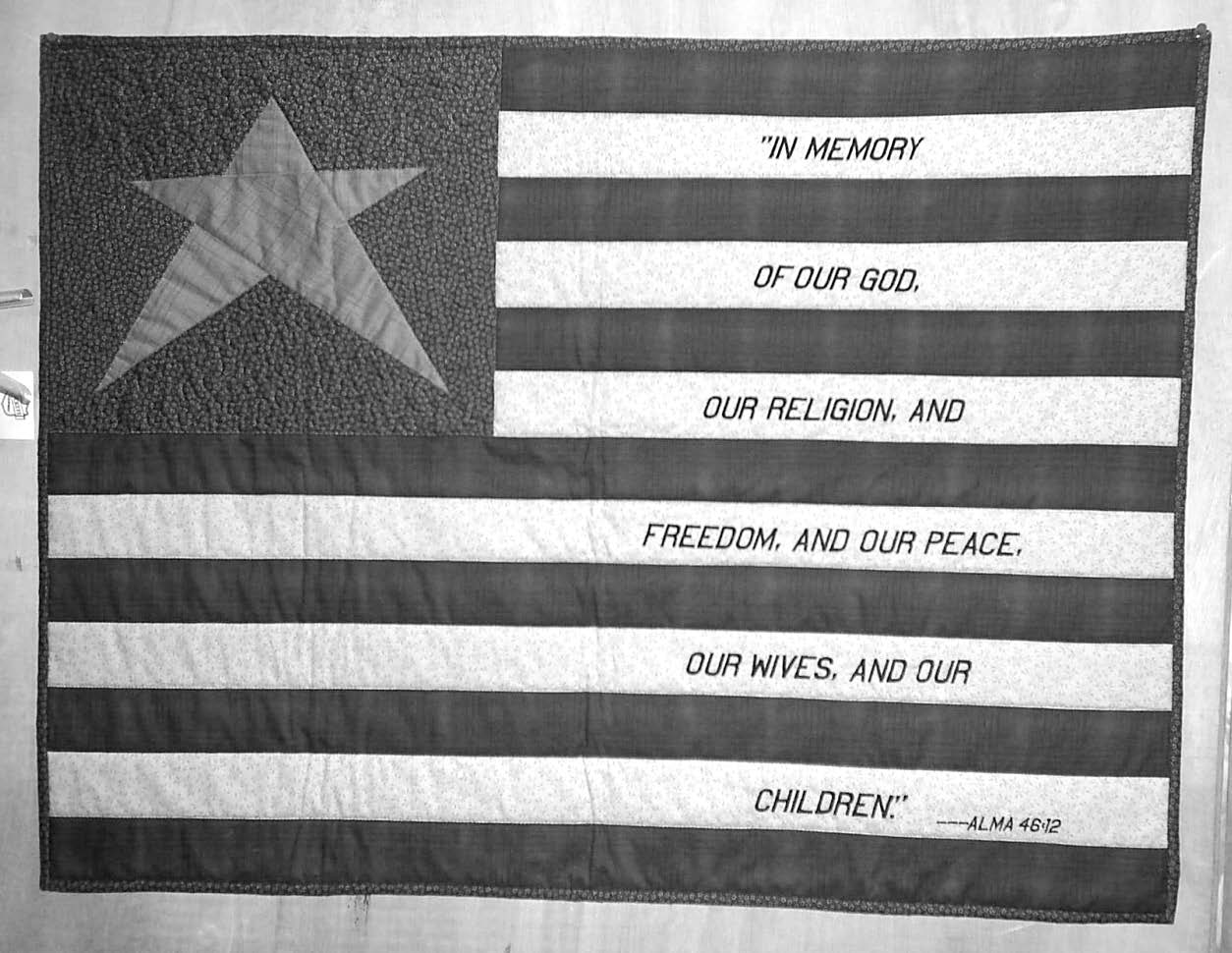

This title of liberty flag was made for Chaplain Mark Allison by Sister Leslie Ison in his home stake. Courtesy of Mark Allison.

This title of liberty flag was made for Chaplain Mark Allison by Sister Leslie Ison in his home stake. Courtesy of Mark Allison.

I asked Sister Leslie Ison, a quilt maker in my Salt Lake Cottonwood Heights home ward, to make a flag representation of Captain Moroni’s title of liberty, so I could carry it with me and display it at Latter-day Saint service member sacrament meetings as I traveled throughout the combat zone. She gladly quilted the flag and sent it to me in time for it to be displayed at our first Latter-day Saint service member conference in Afghanistan on December 12, 2004, which was presided over by Elder William Jackson, Area Authority Seventy. Additionally, Sister Ison also secured the help of our ward Relief Society sisters to make several hundred postcard-sized title of liberty flags for me to give to Latter-day Saint service members wherever I encountered them throughout Afghanistan. After three to four months I had distributed all of them. They proved to be a powerful and motivating symbol for Latter-day Saint warriors. It even inspired an Army Apache helicopter pilot to paint the words of the title of liberty on the side of his helicopter.

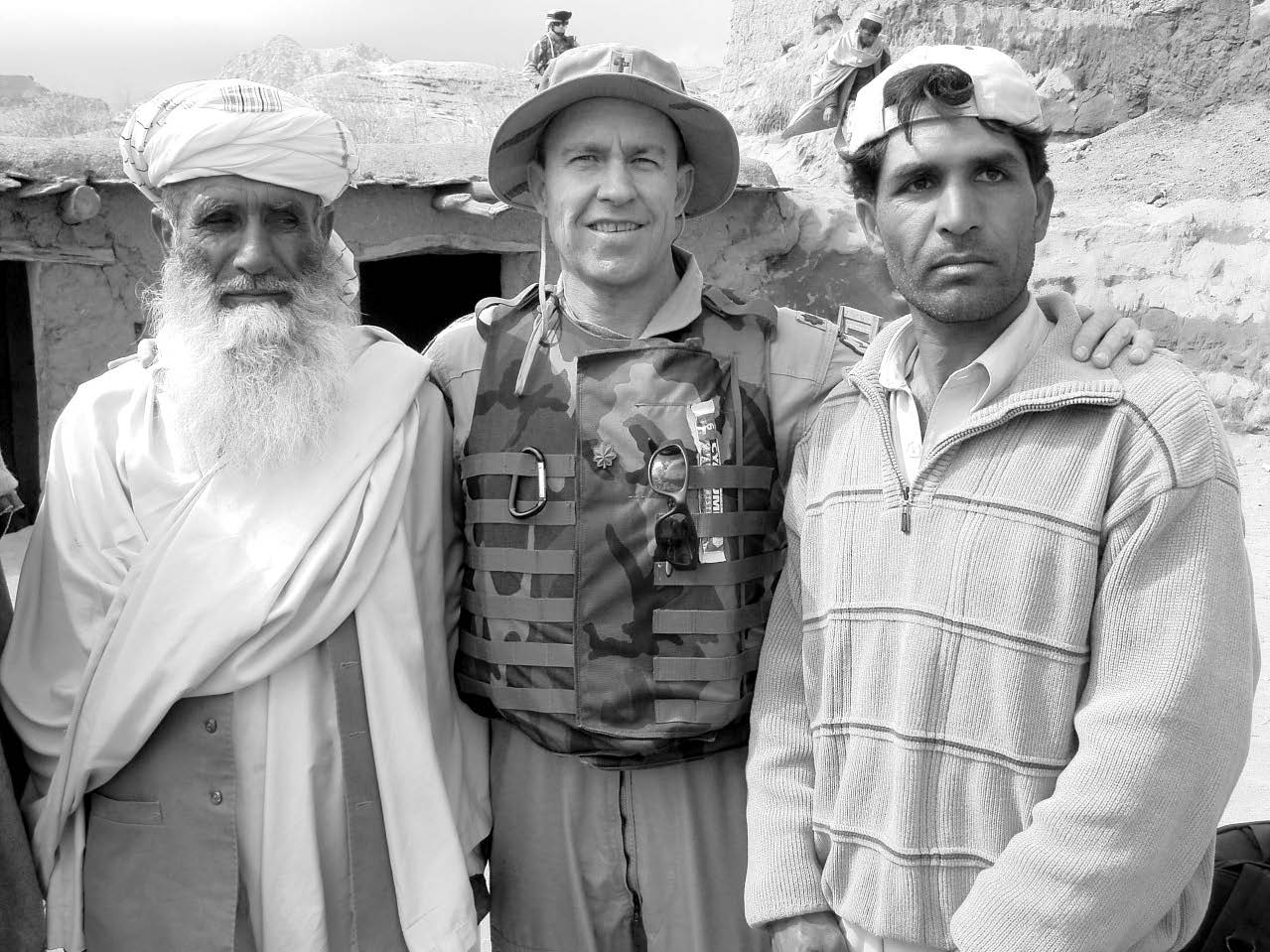

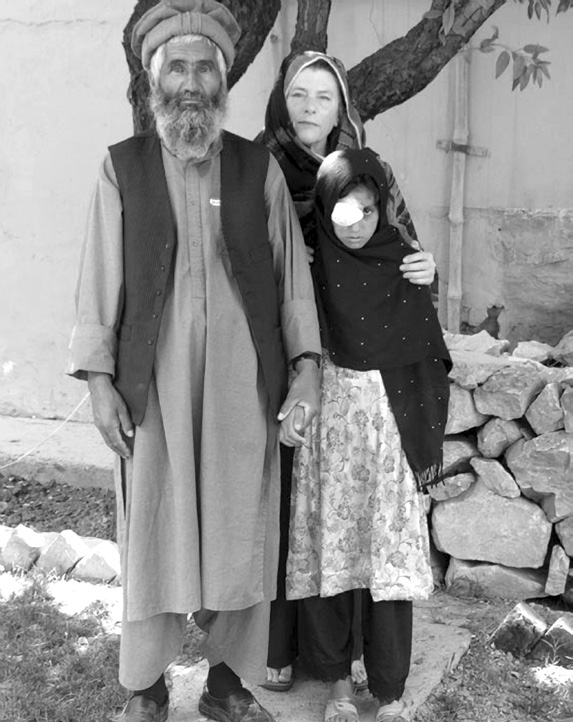

Latter-day Saint chaplain Mark Allison (center) is shown with an Afghan father and son near the border of Afghanistan and Pakistan. Courtesy of Mark Allison.

Latter-day Saint chaplain Mark Allison (center) is shown with an Afghan father and son near the border of Afghanistan and Pakistan. Courtesy of Mark Allison.

Before long, I noticed that these miniature title of liberty flags were an effective reactivation tool with less active Latter-day Saint military personnel. It was heartwarming and brought a smile to my face when I circulated throughout the battlefront visiting Latter-day Saint troops at Forward Operating Bases and saw the small title of liberty flags being displayed by both active and less active service members. Others kept it in their scriptures, and several carried it with them whenever they went “outside the wire” on combat missions. Displaying and distributing these small flags was likely the most powerful and effective ministry tool I have had in my long career as a military chaplain. Without a doubt, the words of Captain Moroni from so long ago echo through the centuries of time to inspire, motivate, comfort, and strengthen modern-day righteous warriors.

JOSEPH LORENZO “REN” ALLRED

Ren Allred was commissioned through the University of Utah’s Army ROTC program in 1972. He was chief of the Army’s Media Relations Branch at the Pentagon during Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm. During more than twenty-four years of active service, he served in a variety of command assignments, from battery command to commanding an artillery group in the Republic of Turkey. He has worked as a government contractor in Africa, the Middle East, and former Soviet Republics. Lieutenant Colonel Allred was the professor of military science (Army ROTC) at Brigham Young University from August 1993 to September 1995. He retired from active duty in March 1996. As a civilian contractor, he was the last president of the Kabul Afghanistan Military District. He and his wife, Linda Kathleen Noble Allred, are the parents of eight children.

My wife, Kathy, and I were in Brazil picking up our son from his mission when I received a phone call from a friend of mine, who was a program manager in Afghanistan. He said, “I need a media individual here as quickly as possible. Would you be willing to come for a year?” Kathy and I discussed it and prayed about it. Since I wasn’t quite ready to retire, I thought it was a great opportunity. Kathy and I visited with Elder Bruce Porter, of the Seventy, seeking his guidance as he had been our bishop and a close friend for many years. Elder Porter told us, “I don’t know why you’re going to Afghanistan, but there must be a reason.” We accepted the job and decided this would be a good opportunity to serve both church and country.

About two months after I arrived in Afghanistan, I was called to be a member of the district council. A month later, I was called to serve as a counselor in the district presidency. After two or three weeks, I still hadn’t been sustained. The next Sunday, I was sustained but not set apart. The district president said, “I don’t know why I’m not setting you apart, but we’ll just delay.” That afternoon, he received word his contract had been eliminated. He was given just three days to leave the country. He called the Area Seventy and explained the situation. Soon after, I received a call from the Area Seventy. He interviewed me and asked for recommendations for the next district president. The next evening, he called me as the district president, but he wanted to know how long I would remain in Afghanistan. I explained I would be there for another six months. At the end of that six months, my company asked me to stay for another year in a new job with an increase in responsibility. I called the brethren and let them know.

Our military district covered all of Afghanistan—from the far south to the far north, from Mazar-e Sharif to Kandahar, and from Helmand province in the west to Jalalabad in the east. Our district also included Manas Air Force Base in Kyrgyzstan. We had over 1,500 members in six branches, about ninety-two service member groups, and about seventy members in remote locations. We also had several members in Black Ops (covert) units. I would receive emails stating, “President, I’m here in country, but I can’t tell you where I am.”

We estimated that approximately 1 percent of the force in Afghanistan were Latter-day Saints—military, defense contractors, and government employees. We had Church members from at least fifteen different countries. I had to recognize I couldn’t do everything I would normally do in a regular, organized Church unit. Possibly 90 percent of my Church time was spent using the Internet. I relied heavily on the Spirit and on email. I called branch presidents, counselors, elders quorum presidencies, and many others over the Internet. I also used the phone whenever I could. I didn’t have the opportunity to travel outside of Kabul because of security concerns.

* * * * *

U.S. Army soldiers being transported in a CH-47 Chinook helicopter. Courtesy of J. Joseph DuWors.

U.S. Army soldiers being transported in a CH-47 Chinook helicopter. Courtesy of J. Joseph DuWors.

We found there were generally four types of Church members who arrived in Afghanistan. The first were active individuals. They were active at home, and they were active while they were deployed. They sought out the Church. They were quickly called into the leadership roles and were extremely helpful. The second type was individuals who were active at home, but in Afghanistan they wanted to “take a break.” The third type was individuals who weren’t active at home, but once they were in the war zone they wanted to become active. They were great. Hopefully, many of them returned home more active than when they left. The fourth and final type were individuals who had not been active at home, and they didn’t want to be active in Afghanistan. I frequently received phone calls from family members who said, “My son (or husband, or daughter, or brother) is stationed over there. He hasn’t been active in the Church. Would you reach out to him? Can you let him know that the Church is there for him?” We were more than happy to do so. Sometimes our overtures were well received, and sometimes they were met with a belligerent attitude. Seeing individuals come back into the faith when they’ve been away for a while were the most tender experiences I had. Interestingly, most of those experiences were generated because of the faith of another member of the Church. It was gratifying to see people change their lives.

* * * * *

One day, I met with an Afghan general officer. He spoke perfect English to me. As I sat down by his desk, he called his “tea boy” to bring us some chai (tea). We would then be expected to spend ten to fifteen minutes socializing. Afghans used “chai time” to determine if they were going to trust you. As the chai boy placed a cup in front of me, I turned to the general and said, “Sir, I appreciate this offer, but I do not drink tea.” I put my hand over my heart and said, “I do not drink tea because of my faith.” He looked at me and said, “You’re a Mormon, aren’t you?” When I answered “Yes, I am,” he replied, “I’ve been to America. I know your religion. I congratulate you for living it.”

I always taught the Latter-day Saints in our military district, “You should be up-front and appropriately share your beliefs with others. They will honor people who are true to their faith.”

* * * * *

Our sacrament services were like a normal sacrament meeting. We had the same format; the same spirit generated by music, prayers, talks, and testimony bearing. The duration of our meetings could be different, though. Sometimes sacrament meeting would only last ten or fifteen minutes because that was all the time the members could attend. Across our military district, we had meetings on Fridays, Sundays, Wednesdays, and other days. Our meetings were matched to the circumstances, the amount of time available, and the number of people who could attend.

One of the pieces of counsel I received from our leaders was to ensure everyone had the opportunity to partake of the sacrament at least once a week. Therefore, the sacrament was a part of almost every meeting. During the week wherever and whenever we could, we offered “gospel instruction classes”—a term the chaplains asked us to use because individuals could be briefly released from duty to attend. Many attendees would not have been able to attend if we called it institute. We often had a combined priesthood and Relief Society class.

To increase individual spirituality among the members, we encouraged every member to read the Book of Mormon each day with the goal to complete it, at least once, during their tour of duty. This helped many members stay close to the Spirit even in difficult times.

The gospel can give you a blessing of comfort when you need it most. It can also build the armor that is always needed around us. Will the gospel protect you against all harm? No, but it can certainly help you to deal with harm. The Lord knows our needs, and he provides the solution.

* * * * *

At the end of my second year, I was told my job was being eliminated. The next day, after I had told the brethren I was leaving, my company again invited me to stay for another year. I accepted their offer and continued serving as district president. During that year there were political actions taken to reduce the number of soldiers in Afghanistan. We saw a significant decrease in the overall force and the number of Church members in the country. I was released on December 31, 2014. The district was reduced to a branch in Kabul with groups located in Kandahar and Bagram. The day I left Afghanistan, we were down to seventy-five members in the entire country.

MICHAEL BEESLEY

Michael Beesley is a retired Salt Lake City police officer. He served two tours in Iraq and five in Afghanistan (2006 to 2013). He has been married to his wife, Marilynn, for thirty-nine years, and they have three children. Michael’s Church service includes being an ordinance worker in the Jordan River Utah Temple and counselor in several bishoprics. He served a mission in New England from 1975 to 1977.

October 3, 2009

Forward Operating Base Bostick

Naray District, Konar Province, Afghanistan

Today was another sorrowful day for our AO [area of operation]. At 0615 [6:15 a.m.], I awoke to the roar of our 155mm cannons. The sound was deafening so we knew the powder charge was for maximum range. This went on for a full hour—two rounds every thirty seconds. When I saw the direction of fire, I knew the reports that had been coming in for the last several days of an impending attack on one of our COPs [combat outposts][1] was more than likely proving to be true. The COP, which was in the process of being closed and then relocated, was vulnerable and presented an excellent tactical opportunity for the AAF [anti-Afghan forces] to strike.

At the same time, air raid sirens at our FOB [forward operating base] were sounding the alert: “In-coming fire; seek hard structure!” We were being shelled by indirect mortar fire from just beyond the mountain ridges on both sides. I quickly got into my body armor and strapped on my Kevlar helmet. I pulled the charging handle on my M-4 and racked a round in my pistol. I then sat in my small but fortified room and waited for further instruction over the loud speakers.

For the next hour, my cement and wooden bunker shook, with dust and small particles falling from the ceiling around me. I had previously put up an angled awning over my bed to catch the falling debris during such artillery fire. Intermittent between the loud blasts of our guns, distant impacts of AAF 82mm mortar rounds could be heard exploding inside and outside the wire [base perimeter]. Within the next hour, Apache gunships, UH-58 Kiowas, and MEDEVAC Blackhawk helicopters began arriving—partly to defend our FOB, but primarily to arm and refuel to support the COP under attack.

Finally, the overhead announcement came that the threat level had dropped at our base, but that a level three uniform was still required when moving about [body armor and Kevlar]. As the day progressed, an announcement I had become all too familiar with was broadcast: “All personnel assigned to battlefield recovery, respond to the aid station.” I said out loud, “Oh no, here we go again.” I knew that stretcher teams, off-duty medical personnel, and anyone else with medical experience would be crossing my doorway, for I was located next to the aid station and across from the new hospital under construction. With focus and determination, these unsung heroes came. As usual, more showed up to help than were needed, but no one was turned away. Due to the large number of assigned staff, of which I was a part, and the overabundance of volunteers, our briefing location was moved to a spacious but unfinished room in the unfinished hospital.

We were informed a large number of casualties were expected and much preparation needed to be completed before we received our wounded warriors. Teams were quickly formed with specialized members shuffling toward their assigned groups. It was then requested that all those with medical experience raise their hands. At the beginning of my police career, I received my EMT certification and throughout the coming years was able to apply many of those skills in the field, so I raised my hand.

This picture, taken in summer 2006, shows Michael Beesley’s military police squad from the 511th Military Police, deployed from Fort Drum, New York, to Tal-Afar, Afghanistan. Courtesy of Marilynn Beesley.

This picture, taken in summer 2006, shows Michael Beesley’s military police squad from the 511th Military Police, deployed from Fort Drum, New York, to Tal-Afar, Afghanistan. Courtesy of Marilynn Beesley.

The first sergeant, who I had come to know during these call-ups in the past, saw me raise my hand and walked toward me. When he got to my side, he pulled me close and quietly said, “You’re not going to have time to help with the wounded. You’re needed for the KIAs [killed in action].” I learned eight U.S. Army soldiers had been killed in the fighting. I repeated, “Eight U.S.?,” showing my obvious surprise. In confirmation, the first sergeant simply responded, “Eight.”

Knowing what was needed next, I began looking for eight tables to set up in an isolated section of the building. I soon learned all available tables had been brought to the aid station. Even the makeshift receiving rooms for the “walking wounded” would only be able to use field stretchers placed on the ground for lack of tables. A young specialist, who saw the concern in my eyes as I stood rubbing my chin, walked up to me and said, “Don’t worry, sir, we’ll get you some tables.” Within fifteen minutes, eight tables from the overflow chow hall were set up—four along one side and four along the other side of the room. I would soon spend two hours attending to eight brave soldiers cut down in the prime of their lives.

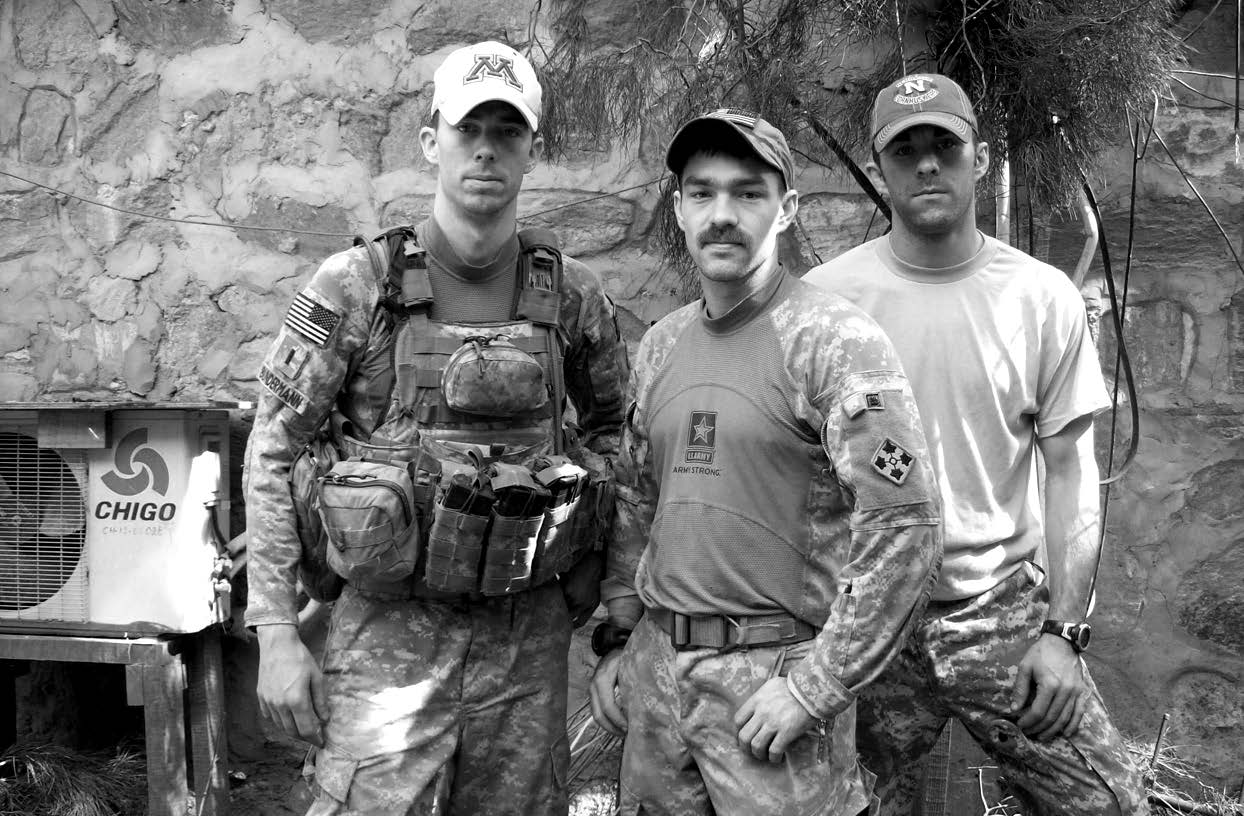

Michael Beesley (second from right) is shown with three Afghan soldiers. Courtesy of Michael Beesley.

Michael Beesley (second from right) is shown with three Afghan soldiers. Courtesy of Michael Beesley.

As the tables were being set up, suddenly a brilliant beam of light shone through the only window in the room, coming to rest upon one of the tables that would soon hold one of the fallen soldiers. I gasped at its brilliant luster and was overcome with the feeling that our loving Heavenly Father had come to take home eight of his brave sons.

The battle at the COP lasted more than ten hours. After two hundred U.S. and Afghan reinforcements were sent into the battle, the COP was finally secured. The dead and wounded could now be flown back to our forward operating base.

While waiting, I was able to recruit two young, wide-eyed sergeants to assist me with notetaking and other associated functions. They were polite and eager to assist, but I could see the trepidation in their eyes. I emphasized to them the importance of what we were about to engage in and attempted to prepare them for what they would see and do. When the time finally came, the fallen soldiers were brought in as they had been taken from their battle positions. The next two hours were very emotional—spent by the side of each soldier helping to identify and prepare him for his final flight home.

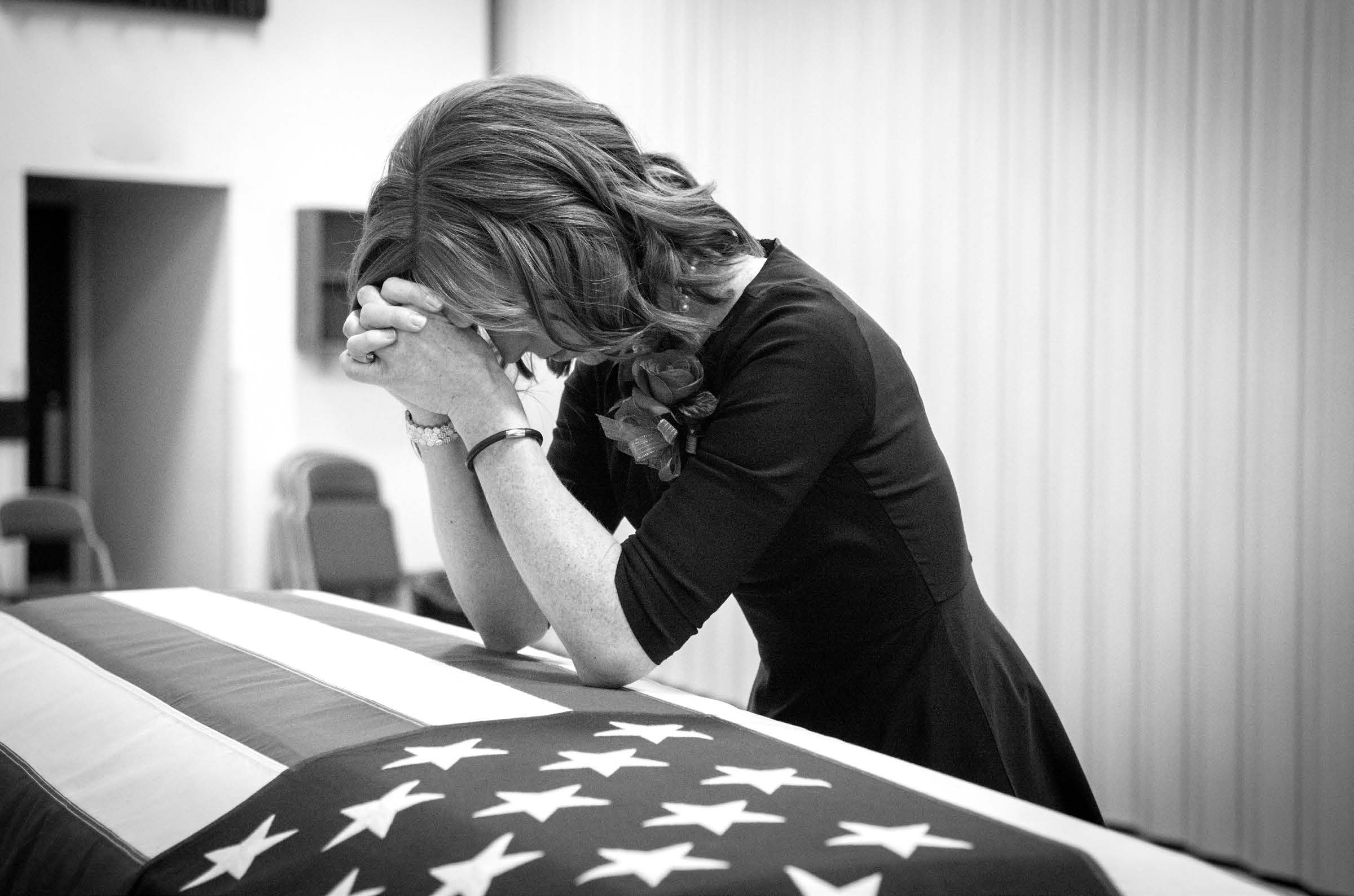

Upon completion of our duties, eight fallen heroes lay flag-draped and ready to be returned to the members of their unit who waited restlessly, but respectfully, just outside the room. As I stripped off my last pair of latex gloves and walked out of that hallowed empty room, I thanked the Lord for those selfless, patriotic soldiers. Not just the ones who had given their lives, but for all the men and women who tirelessly, and without complaint, stayed to the very end in true and loving service to their fellow brothers-in-arms.

WILLIAM BLACK

William Black served in the United States Marine Corps Forces Reserve in Utah from 2002 to 2011 as a light armored vehicle crewman. He served on deployments to Okinawa, Japan, in 2003–4, Fallujah, Iraq, in 2007–8, and Helmand Province, Afghanistan, in 2009–10. He served a Latter-day Saint mission in Melbourne, Australia, and graduated from Utah Valley University and the University of Iowa. He has served in Young Men and elders quorum presidencies.

Helmand Province, Afghanistan

Winter 2009

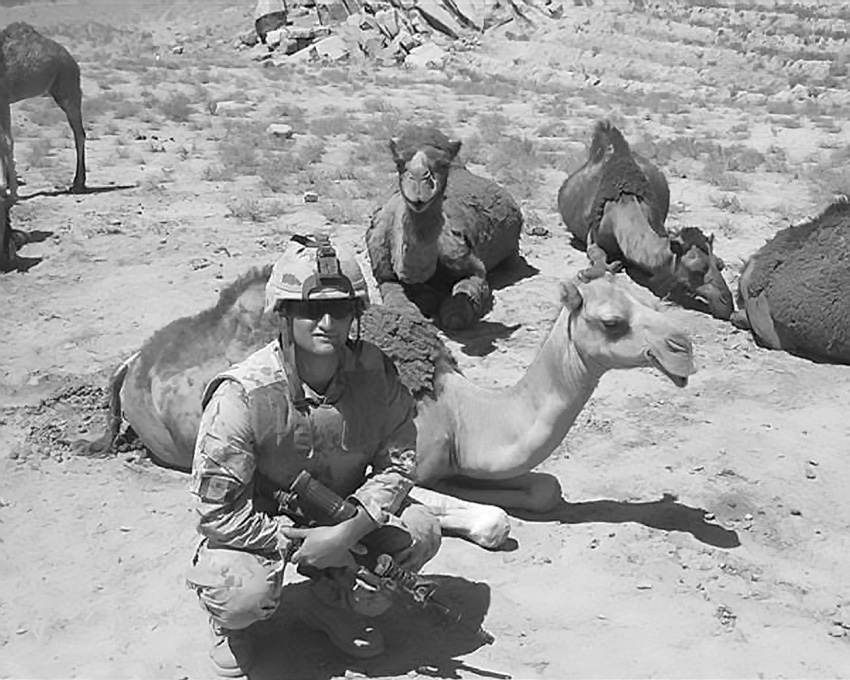

William Black at Combat Outpost Payne in Helmand Province, Afghanistan, during the summer of 2010. Courtesy of William Black.

William Black at Combat Outpost Payne in Helmand Province, Afghanistan, during the summer of 2010. Courtesy of William Black.

While providing security for a route clearance team, I decided to position my LAV (light armored vehicle) atop a certain hill that was preventing us from seeing a good portion of open desert clearly. I felt the position would be the perfect vantage point for us to provide security without having to move the vehicle while the route clearance crew inspected the area for bombs.

As we approached the top of the hill, a feeling hit me very powerfully that we should stop immediately. Almost before I could issue the command to the driver, he stopped accelerating. I felt we were in danger and that there was an improvised explosive device (IED) somewhere nearby. We backed down the hill, keeping to our original tracks so as not to disturb any new ground. We took up a position on the far side of the hill, and our sudden change of plans caught the platoon commander’s eye.

About twenty minutes later, I told him of my impression, and he asked the route clearance team to inspect the top of the hill. They discovered a large IED buried directly in front of our tracks, not more than ten feet from where we had stopped. The explosive charge was larger than one that had killed several crew members in a similar vehicle about a month earlier.

I have never felt such an overwhelming compulsion to act a certain way while in a combat zone. The warning I received was definite and powerful enough to prompt me and my driver to react immediately. As I told him to stop, he felt an identical feeling of urgency and immediately stopped. My driver did not consider himself to be a religious person, but he told me, without my prompting him, that he felt an unmistakable need to stop driving forward immediately before my command to do so. Another few feet, a fraction of a second at our speed, and we would have run over sixty pounds of handmade explosives.

No other explanation adequately describes my experience, including the simultaneous impressions my driver and I received that day, other than that God protected us. I believe he did—whether in answer to the faith and prayers of the wives and children of the members of my crew or for some other reason, it makes no difference. We received a warning that probably saved our lives.

DANIEL C. BOLICK

Daniel Bolick retired from the Federal Bureau of Investigation in 2009 after twenty-six years of service as a special agent, supervisory special agent, and acting legal attaché in Hong Kong and Pretoria, South Africa. He worked as a civilian in Afghanistan in the NATO Rule of Law Field Support Mission—Afghanistan in Helmand Province. He served in Afghanistan several years and was Patrol Base Jaker Latter-day Saint service member group leader. He served a Latter-day Saint mission in Taiwan in the late 1970s.

It was Sunday in Helmand Province, Afghanistan. There were no organized Latter-day Saint meetings on the military base where I stayed, but I saw that a nondenominational service was scheduled and decided to check it out. I felt a warning premonition from the Spirit as this thought passed through my mind, but I was uncertain what it meant. It wasn’t telling me to stay away, so I entered.

The Kandahar Military Branch of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in May 2009. Courtesy of Eugene J. Wikle.

The Kandahar Military Branch of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in May 2009. Courtesy of Eugene J. Wikle.

The one-hour meeting began with an opening hymn familiar to me. It is found in Latter-day Saint hymnbooks under a different name from the chapel’s hymnal. The melodic sounds were sung a cappella by a couple dozen attendees because there was no piano. I sang along, adding my voice to those of my fellow Christians.

The leader of this small congregation gave his sermon from the New Testament, Philippians 3, and I followed along in my smartphone version of the King James Bible, highlighting selected passages as he read. Midsermon and without any warning, the pastor suddenly turned to the topic of Mormonism. “There is a great heresy called Mormonism,” he declared from the rickety wooden podium.

I could not allow such a statement to go unchallenged. I did not hesitate to raise both hand and voice, which easily carried through this tiny congregation. “Excuse me, but I am a Mormon,” I announced. The preacher gave no audience to my comment and continued through his prepared remarks. “They believe in little gods,” he started to say, but then he stopped, suddenly jumping back to his comments on Philippians, which was supposed to be the basis for his sermon—an awkward transition at best.

I thought for a moment what I should do and considered walking out, but the presence of the Spirit told me to remain and think uplifting thoughts, so I stayed seated in my now somewhat uncomfortable position. Nothing more was said about Latter-day Saints, and I sensed that my brief interjection may have derailed what would otherwise have been a protracted tirade against the teachings of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. I bowed my head for the closing prayer and was the first person out the door afterward.

As I hastily walked away from the diminutive chapel, I heard footsteps approaching from behind. It was a member of the congregation. He caught up with me to apologize for the chaplain. The fellow attendee reassured me he did not agree with what was said about my faith. A few moments passed, and another person from the congregation caught up with me and gave similar feedback. Having heard the words of those two, I believed there were still others who probably also felt the same way.

Time passed, and I went to the chow hall for dinner. Much to my surprise, the chaplain bumped into me as I waited in line. Ashen-face, he then asked politely for a moment of my time, and I withdrew from the queue to speak with him. He apologized to me for his inappropriate remarks and asked for my forgiveness. I knew that the only correct answer to give was “Yes, I forgive you.”

RICHARD BRATT

Lieutenant Colonel Richard Bratt, U.S. Army (retired), deployed to Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom. A native of Winslow, Arizona, he attended the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, for two years and then served in the New Zealand Wellington Mission. He returned to West Point after his mission and graduated in 1996 with a degree in mechanical engineering. He also earned a master’s degree in aerospace engineering from the University of Alabama at Huntsville and graduated from the U.S. Naval Test Pilot School in Patuxent River Naval Air Station. Richard retired from the Army after twenty-one years of active duty service. Richard and his wife, Nancy, have enjoyed serving in the many branches and wards where they have been stationed.

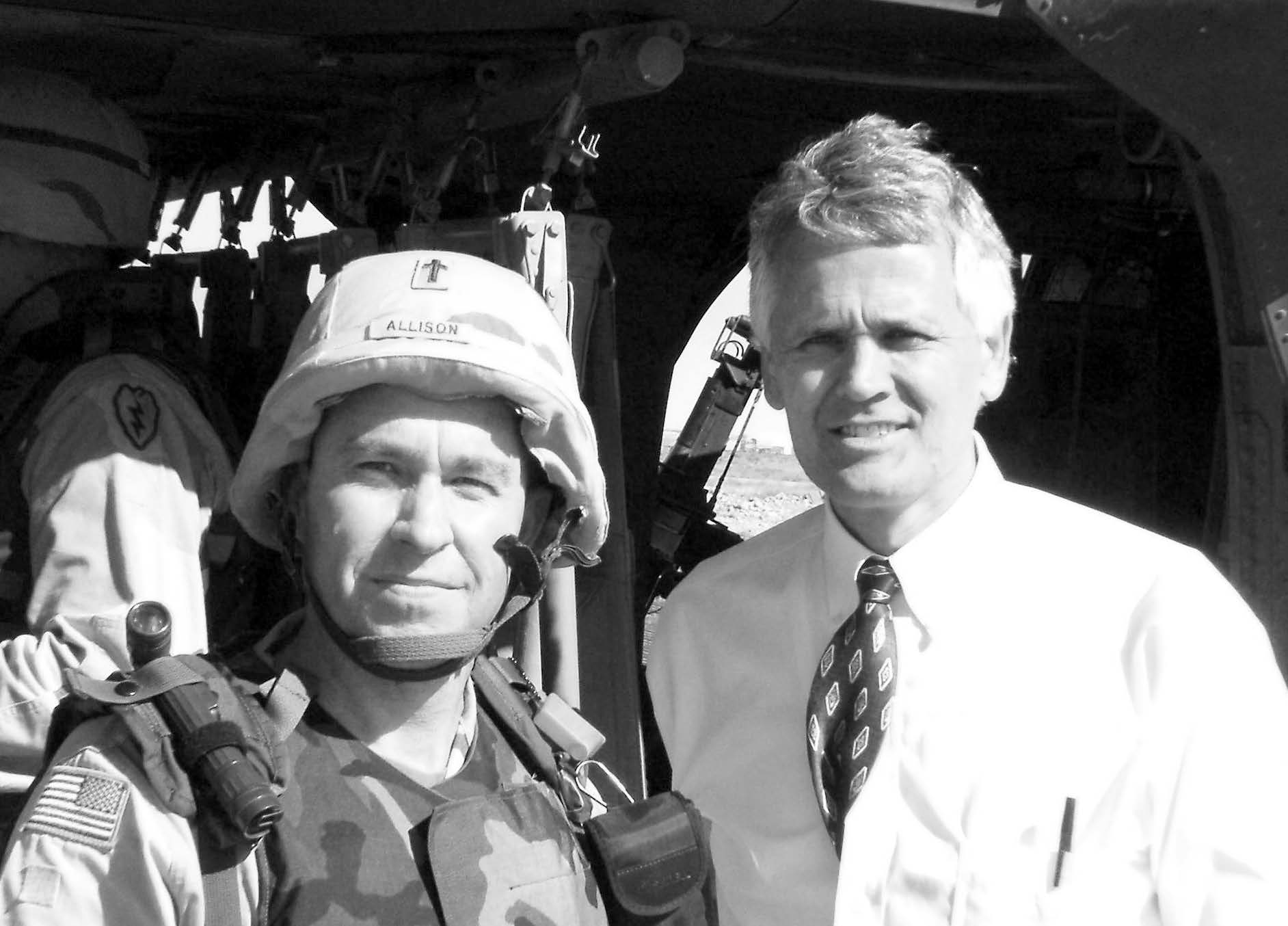

Captain Richard Holling and country singer Toby Keith are shown flying from Kabul to Bagram, Afghanistan, on June 3, 2004. Toby Keith was visiting National Guard soldiers from his home state of Oklahoma. Courtesy of Richard Bratt.

Captain Richard Holling and country singer Toby Keith are shown flying from Kabul to Bagram, Afghanistan, on June 3, 2004. Toby Keith was visiting National Guard soldiers from his home state of Oklahoma. Courtesy of Richard Bratt.

I served in Bagram, Afghanistan, from March 2004 to March 2005 in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. I was the commander of B Company, 214 Aviation Regiment, a CH-47D (Chinook) helicopter company based out of Wheeler Army Airfield, Hawaii. I had several great experiences in Afghanistan as a pilot, commander, and member of the Church. I flew a variety of missions including basic resupply, sling loads carrying vehicles, humanitarian aid missions, Army and Marine air assaults, and different types of Special Forces infiltrations. The tactical missions were the most challenging missions to plan and execute but were the most rewarding to fly. Because our Chinooks had such a large carrying capacity, we also flew many VIPs. I flew country singer Toby Keith, rock legend Ted Nugent, CBS News reporter Laura Logan, former Secretary of the Navy and U.S. Senator James Webb, and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld.

On September 16, 2004, our task force received the mission to transport Afghan Interim President Hamid Karzai, his entourage, and protective detail to Gardez (a town sixty miles south of Kabul) for a school opening. This critical mission required extensive planning and was considered very high-visibility because it was three weeks prior to Afghanistan’s first democratic election. We were always told that if we lost President Karzai, we would lose Afghanistan because of his ability to keep the many Afghan factions together. In order to perform this mission, we flew three Chinooks and had two AH-64A Apache escorts for protection.

The mission began as we departed Bagram and headed south to Kabul to pick up President Karzai at the presidential palace. I was the air mission commander for the Chinook flight and also the pilot-in-command of the second aircraft of three. The first aircraft landed at the palace, picked up several people, and departed the palace landing zone. My aircraft landed at the palace to pick up the remaining passengers going to Gardez. My crew chiefs and flight engineer did an excellent job preparing the aircraft for the mission. They even got an extra soft seat cushion for President Karzai to use. The first thing we noticed about him as he boarded the aircraft was that he gave the cushion to an older Afghani gentleman who also was on the flight. Everyone in the crew remarked how impressed they were by that small act of kindness. We then departed Kabul and headed south for Gardez.

The initial plan was for both aircraft to land at the same time in a large dirt soccer field near the school. As we approached the landing zone, we saw hundreds of people awaiting President Karzai’s arrival. As the first Chinook landed and offloaded the passengers, we realized it would be impossible to land two Chinooks simultaneously because of the hazardous dust conditions created by the first Chinook. For some reason, the locals had plowed the entire field, which made the landing even worse because of the poor visibility created by the dusty conditions.

Consequently, we flew a go-around to the right and came in after the first aircraft departed the landing zone. My copilot, CW4 Neil Hermoso, was on the controls as we approached the field above twenty knots to avoid losing our visual cues from the dust cloud. He began the descent, and as the aft wheels touched the dirt, a dust cloud engulfed the aircraft, and we couldn’t see anything. Usually, when we conducted dust landings, the aircraft would sink into the soft ground, but for some reason we kept sliding forward.

On July 24, 2004, 25th Infantry Division Soldiers, assigned to the Joint Logistics Command stationed in Bagram, Afghanistan, prepare a vehicle to be sling-loaded by a Chinook helicopter. Courtesy of DoD.

On July 24, 2004, 25th Infantry Division Soldiers, assigned to the Joint Logistics Command stationed in Bagram, Afghanistan, prepare a vehicle to be sling-loaded by a Chinook helicopter. Courtesy of DoD.

As I tried to see through the dust, I could see the aircraft approaching the rock wall of the soccer field, and I immediately told Neil, “Go-around!” If we continued, the front rotor blades would have hit the wall. Neil did a tremendous job and executed a smooth go-around, despite the dusty conditions of the landing zone. As we came in on short final for the next approach, the ground controller came across the radio and screamed, “Rockets! Rockets!—Abort!” We immediately broke to the left and departed to the north. I made contact with Pirate 6 (LTC Rodney Robinson, from the 1-211th Aviation Regiment—Utah National Guard), who was in one of the Apaches and informed him of our situation and intentions.

We eventually reorganized the flight and returned to Kabul. While en route, President Karzai inquired if any of the children or people at the school opening were injured from the rockets. When we landed back at the presidential palace, President Karzai made his way to the front of the cockpit, shook our hands, and gave us a thumbs-up sign.

We then flew back to Bagram and shut down the aircraft like it was just any other routine mission. As Neil and I walked back from our flight, we both talked about how we were watched over by Heavenly Father. A few short hours after the incident, the assassination attempt was already on the major news channels.

As I look back on the incident, I am amazed at how the Lord protected us. For some unknown reason, the field had been recently plowed, which made the dust situation worse. As we completed our first approach and landing, the view from our six o’clock position was totally obscured. This is significant because that was the same direction the RPGs came from. We were on the ground for only about 3–5 seconds, and the dust cloud was so huge that it totally masked the aircraft. If we would have landed first, we would have waited for the dust to settle before lowering the ramp to let President Karzai and his detail out, which would have given the enemy an excellent opportunity to engage our aircraft on the ground—a much easier target than in the air. Because we were on the ground for such a short time, the dust cloud still masked our entire aircraft. On our second approach, the enemy decided to engage our aircraft prior to landing. Fortunately for us, they missed the aircraft completely!

Three weeks later, Afghanistan held its first successful democratic election and Hamid Karzai was elected president. Reflecting on that September day, I know Heavenly Father protected all of us. There may be some who would attribute the events to superior airmanship or just plain luck; however, I absolutely know that the Lord had a hand in the events of that day.

PAUL BRECK

Paul Breckserved as a missionary in the California Los Angeles Mission. He served in the active and reserve components of the U.S. Army for over nineteen years. He also served as a platoon leader for the 1457th Engineer Battalion in Operation Iraqi Freedom. He served as a company commander and staff officer with the 1st Infantry Division, 3rd Brigade in Jalalabad, Afghanistan, from June 2008 to June 2009. He also served in Kabul, Afghanistan, as the Camp Eggers facility project manager.

On June 13, 2008, I started my journey to Afghanistan. I felt prepared and ready for the deployment. I had trained for over a year with A Company, Special Troops Battalion, Third Infantry Brigade Combat Team, First Infantry Division. Shortly before deploying, I was the commander of A Company Engineers, but I had a change of command before leaving. I had served for twelve months as a commander. I left with eight other people on what is known as the torch party. We were sent ahead of the brigade to start the process of taking over from the 173rd Parachute Infantry Regiment based out of Jalalabad, Afghanistan. The advance party consisted of logisticians, transportation officers, and property book officers.

Soldiers salute their fallen comrades. Courtesy of J. Joseph DuWors.

Soldiers salute their fallen comrades. Courtesy of J. Joseph DuWors.

After a day or two in Bagram, I heard on the loud speaker, “In thirty minutes, all personnel are to report to Disney Drive for a ramp ceremony.” Disney was the main road that spanned the entire main part of the airfield and led to the air terminal. I was not sure what was going on, but I remembered that during orientation, they said if we heard that announcement we were to move to Disney and participate. Hundreds, if not thousands, of people lined the street.

Everyone was very quiet, and I was struck with a sense of humility. I saw a vehicle out of the corner of my eye making a turn down the part of the road I was on. I was near the passenger terminal, and the only way to the flight line was right in front of me. The vehicle was moving slowly and had several people walking behind it. As it approached, the emotions started to kick in. Tears welled up in my eyes. I figured out what was going on. The vehicle was carrying the flag-draped caskets of two fallen soldiers. Behind the vehicle was a general officer, a battalion commander, and a command sergeant major. Behind them were two NCOs [noncommissioned officers] who were to escort the remains all the way to their final resting place. Near them was a cameraman filming the ceremony. As the vehicle approached, I noticed that all were slowly raising their right arms to render a very deliberate and reverent salute. Each soldier, airman, sailor, and Marine rendered a very somber salute. The vehicle moved closer to me, and tears slowly rolled down my face. I stood tall and turned my head slightly to the left to put my eyes on the Stars and Stripes draped over the coffins. I slowly brought the fingers of my right hand to the very edge of the brim of my hat. I watched as the vehicle drove by me, and I said a little prayer to myself: “Our Father in Heaven, please be with these fallen heroes as they pass through the veil, and comfort their families, and let thy Spirit be with them. Amen.” The Spirit was present, and I felt overwhelmed. The moment was very somber and humbling, and it was difficult to control my emotions. I had been in the military for nearly seventeen years, but this was the first time I had experienced a “ramp ceremony.” The caskets moved onto the flight line and were loaded onto an empty C-17 cargo jet. The jet was quickly buttoned up and headed down the runway for takeoff. All of the workers around the flight line stood by to render a salute as the plane passed by.

This was the start to my yearlong deployment. The realities of combat had just hit me as hard as a Mack truck. Nothing over the past year of training had prepared me for a moment like this. Two days later, we boarded a C-130 cargo plane and flew to Jalalabad. The flight was only thirty minutes. After arriving at Jalalabad, I quickly settled in and started working. I lived at Forward Operating Base Finley-Shields. The base was named after two soldiers who were killed by a suicide car bomb about a month prior to my arrival.

A soldier relaxes during a few minutes of quiet time. Military life in a combat zone has been described as “hours of boredom punctuated by moments of sheer terror.” Courtesy of J. Joseph DuWors.

A soldier relaxes during a few minutes of quiet time. Military life in a combat zone has been described as “hours of boredom punctuated by moments of sheer terror.” Courtesy of J. Joseph DuWors.

As I settled in, I started going out on convoys and helicopter rides. I was able to see the areas my battalion would be responsible for in Nangarhar province while conducting counterinsurgency operations. The terrain was spectacular. To the south are the Tora Bora Mountains, about eighteen thousand to twenty thousand feet tall. They were still snowcapped, and their beauty is awe inspiring. These mountains are rugged and steep and provide most of Southern Nangarhar with water for irrigation and living.

Soldiers from my battalion arrived and settled in. I had lots of concerns and doubts, but I put my head down and kept moving forward. The mission must go on. We must do our duty, whatever it is.

On July 8, 2010, my good friend and brother-in-arms Sergeant Douglas Bull was killed by an IED [improvised explosive device]. I woke up that morning feeling uneasy and on edge. I went to the office around 0730 [7:30 a.m.] and started working on some emails and small projects. Around 1100 [11:00 a.m.], word came down that a vehicle had been hit in Chowkay Valley [near the Pakistani border] by an IED. Chaos ensued as we tried to get the details.

An American infantry rifleman looks for enemy activity. Courtesy of J. Joseph DuWors.

An American infantry rifleman looks for enemy activity. Courtesy of J. Joseph DuWors.

We soon learned that an IED killed one soldier and wounded three others. I asked Major Kip Korth if he knew who was killed. He hesitated and said, “Sergeant Bull.” My eyes immediately welled up with tears. A communications blackout was put in place so there was no way for me to call home. I sent my wife a quick note that said “Bad things happened today. Can’t say much. I will talk to you in a couple of days.”

For the first time in my life, I felt depressed and alone. I had hundreds of people around me, yet I felt alone. I started to feel like I was in the wrong place doing the wrong job. That night, I lay in bed and cried. I did not sleep and had a hard time not thinking about SGT Bull and the family he left behind. I had thoughts that I never had before. I wondered if there was any way I could get out of this deployment. I fell asleep and woke up feeling like I could do this assignment. My mind was not cleared, but clearer thought processes had returned. Now it was time to help everyone move on.

Around July 10th, a memorial service was scheduled. After a few speakers, the service continued with the first sergeant reading the roll call, a long and solemn tradition. This brought tears to my eyes. He read the names one at a time, and then he said the name that we had all come to honor, “Bull. SGT Douglas Bull. SGT Douglas Bull.” No answer. At that moment, “Taps” began to play. We all stood and rendered a salute in honor of Sergeant Douglas Bull. Following the playing of “Taps,” we filed one by one to the front of the memorial. We snapped to attention, raised our hands slowly to a salute, lowered them slowly, and then knelt before the memorial display and said a short prayer.

LILIA BULLOCK

Lilia Bullock, born in San Angelo, Texas, served in both Iraq and Afghanistan. During her Afghanistan deployment, she served as a captain in the United States Army in the 82nd Combat Aviation Brigade as the brigade chemical officer. She also served as the assistant S2 (Intelligence) during the deployment. She was the branch pianist during the deployment and a Primary worker in her home ward. She married Donald Earl Bullock Jr. on December 20, 2005.

I believe in the power of fasting and prayer. This past Sunday, I felt the strong urge to fast. I hadn’t fasted the previous Sunday since I had to work that day. I almost went to breakfast. I did go to the chow hall. On my way there, my feet stopped on their own, and the word “fast” came powerfully to my brain. I tried to ignore it and justify why I shouldn’t fast. I signed in at the chow hall and felt a heavy weight on my chest. I grabbed a tray and stood in line, but I couldn’t think straight. All I felt was that I shouldn’t be there. I stepped out of the line and walked out of the chow hall without grabbing a bite to eat. I went straight to my room and started my fast. I fasted for the safety of my husband, asking the Lord to watch over him while he flew, so that he could come back safely to me and we could be sealed for time and all eternity.

He was stationed in Shindand, Farah, Afghanistan, at that time and had been gone for a week. He came back the next day without incident. I didn’t think much of it until this morning. Last night, my husband went out on a three- to four-hour resupply mission. He was flying attack chase for three Black Hawks [helicopters]. He smelled faint smoke in the cockpit but didn’t think much of it. He thought it was the smoke from fire in the villages that sometimes wafts into his aircraft. When they were coming back, smell of smoke came back stronger as he was climbing over a mountain. He told his front seater to put on his goggles since he thought it might be a generator fail. Three seconds after his front seater put on his night vision goggles, the generator failed and the cockpit started to fill with heavy smoke. He looked for a place to land, but he was over rocky terrain, and there was no safe place.

He started to descend and asked one of the Black Hawks to be his wing and tell him if his aircraft was on fire. His left generator was blowing heavy sparks, which meant he was on fire. He wanted to open the cockpit door to relieve some of the smoke in the cockpit, but he knew that at the altitude and speed that he was flying, the door would be ripped off. He started getting flashbacks of our friend who was in a similar situation in May, who died while trying to land an aircraft in a little valley on a mountaintop. He started to panic but said a quick prayer. As he was about to open the door, he felt a strong feeling to calm down—everything would be all right. Within a couple of minutes, he felt the airframe shudder, and almost immediately the smoke cleared.

The generator exploded, which stopped the sparks and kept the aircraft from going up in flames. He was able to safely make it home. As he told me the story this morning, I kept thinking about my fast and all of my prayers for his safety, as well as my family’s prayers and placing our names on temple prayer rolls. I broke down and cried for a second when I thought about this.

* * * * *

Donald and Lilia Bullock served together in the same

Donald and Lilia Bullock served together in the same

area in Afghanistan. Courtesy of Donald and Lilia Bullock.

My deployment story started when I was sent to Iraq in 2007 as a brand-new second lieutenant. I was fresh, green, and naive to the ways of the Army. I was eager to start my job, eager to integrate with my new unit, and I was single. I became a target to every male in that camp. Though I wanted to maintain the standards of the Church, I allowed the intense peer pressure to break me down.

The stress of the deployment, the relationship I was in, and my loneliness finally pushed me to turn to a friend of my boyfriend, named Don Bullock, whom I trusted. He was a maintenance test pilot for the AH-64D Apaches and worked with my boyfriend. He was the only person who showed a willingness to listen to my distress. I latched on to his kindness with a fervent grasp. He made an effort to eat breakfast every morning with me, as no one else in my unit would eat with me, not even my boyfriend. A friendship sprang up between us that I didn’t want to lose.

As we redeployed back to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, the current relationship I was in threatened the friendship I had developed with Don. Fortunately, that poisonous relationship came to an end, and I was able to foster the relationship I had with my dear friend. That friendship gradually sprung into a relationship and from there into our marriage. I loved this man and couldn’t see how I could spend the rest of my life away from him. However, he wasn’t a member of the Church. As we became serious in our relationship before our marriage, I told him I could never leave the Church, even if I wasn’t living my life in accordance to Church standards at the time. He was open-minded to what I had to say, and he had family history with the Church. He related to me that he used to go to the Church meetings with his great-grandmother when his mother used to live with her in his early years. When his mother decided to leave the Church, she took him with her. Despite his experiences growing up and going through his first marriage, he was constantly looking for a church to join. He started coming to church with me five months before we were married.

Donald and Lilia Bullock share a moment with Church district president Gene Wikle (right) in Afghanistan. Courtesy of Eugene J. Wikle.

Donald and Lilia Bullock share a moment with Church district president Gene Wikle (right) in Afghanistan. Courtesy of Eugene J. Wikle.

Although I wanted a small wedding, we ended up marrying in the church on December 20, 2008. The ceremony was performed by our ward bishop and attended by my family and half of the ward members. The day was bittersweet. I was elated that I was marrying my sweetheart and that my immediate family could all be there, but I wasn’t being sealed for time and all eternity, which was something I wanted more than anything else.

After we married, my husband started taking the missionary discussions and was baptized on February 21, 2009, two months after our marriage. That day was so beautiful to me. It was a step closer to our ultimate goal of being sealed together. A month and a half later, we were deploying again, this time to Afghanistan. We were originally scheduled to deploy in November 2009, but with the push to increase troops in Afghanistan, my brigade commander pushed to have us deploy six months earlier than scheduled. He received his wish, and April 2009 saw the 82nd Combat Aviation Brigade deploying to southern Afghanistan. My husband left a week before I did.

Donald and Lilia Bullock inside a military tent. Courtesy of Donald and Lilia Bullock.

Donald and Lilia Bullock inside a military tent. Courtesy of Donald and Lilia Bullock.

As I watched general conference the weekend before I deployed, I voiced some concerns I had about leaving to a close friend of mine in our ward. Her husband and my orthodontist (who lived in my ward) gave me a priesthood blessing. It was full of comfort and guidance. It assured me that my husband would return home safe and that I would be safe as well as long as I kept the commandments, remembered to pray faithfully, and continued reading my scriptures.

On the 31st of May 2009, our district president, President Gene Wikle, met with us. He spoke with me a little prior to the start of sacrament meeting, and I told him of my husband, who couldn’t be there because he had to fly some maintenance test flights that day. President Wikle was kind and gave me an “Armor of God” coin for my husband and myself. It was a beautiful coin, and I still carry it. He later announced to the little branch that my husband and I were the first recorded Latter-day Saint married couple in the Kandahar Branch in Afghanistan. I thought that was neat.

When I saw my husband later that day, I gave him the coin from President Wikle. He was impressed that the district president would think of us. I saw President Wikle the following Tuesday at the laundromat as I was pulling my clothing out of the dryer. We started talking again, and I felt impressed to let him know of my husband’s recent conversion. He asked if we had been to the temple yet. I told him no but that I was hoping we would be able to qualify to go soon after we returned to the States. He wrote down some notes about our situation, and we parted. He sent a message to the branch presidency that he wanted for us to take temple preparation classes. Once again, I was impressed by the love and concern he had shown for us in our little branch.

On the 17th of April 2010, Donald Earl Bullock Jr. and I were sealed for time and all eternity in the Raleigh North Carolina Temple. It was a beautiful day, perfect for this sacred ceremony.

BRADY COX

During Operation Enduring Freedom, Brady Cox served as an individual augmentee[2] in the U.S. Medical Role 2E Hospital at Camp Holland, Multinational Base Tarin Kowt, Uruzgan Province, Afghanistan. He was an emergency physician stationed at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth, Virginia. He has served in the bishopric of his ward and as an assistant group leader to a service member group.

An American flag flying at sunset over Camp Holland, Tarin Kowt, Afghanistan. Courtesy of Brady Cox.

An American flag flying at sunset over Camp Holland, Tarin Kowt, Afghanistan. Courtesy of Brady Cox.