Veteran Accounts

Kenneth L. Alford, “The Gulf War: Veteran Accounts,” in Saints at War: The Gulf War, Afghanistan, and Iraq (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 9‒36.

(Arranged alphabetically by last name)

MARK ALLISON

Mark Allison served as a Latter-day Saint chaplain in the U.S. Navy, U.S. Marine Corps, and U.S. Army and retired from military service in 2018 at the rank of Colonel. In 1990, he was the first U.S. military chaplain to arrive in the Operation Desert Shield combat zone, and from 2004 to 2005 he served as the senior Latter-day Saint chaplain and priesthood leader in Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom. He currently serves as the Latter-day Saint chaplain at the VA Medical Center at Salt Lake City, Utah. His wife is Kathleen Allison.

A few months before my ship (USS England [CG-22], U.S. Pacific Fleet) departed on a routine six-month western Pacific deployment, Elder Neal Maxwell of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles accepted my invitation to speak at the San Diego regional Latter-day Saint military fireside. Prior to the fireside, I accompanied him to my ship berthed at the Naval Station San Diego, where we met the commanding officer and dined together in the officer’s wardroom. Later, Elder Maxwell graciously gave me an apostolic blessing of protection and counsel before I deployed overseas. This blessing proved to be prophetic, as we did not know at that time (at least I didn’t know) that in only a few short weeks my ship would unexpectedly be at the tip of the spear in a combat situation in the Persian Gulf.

At approximately 0400 hours [4:00 a.m.] on the morning of August 2, 1990, we awoke to the sound of General Quarters [a readiness condition when action is imminent]5 and the command “Battle stations, battle stations. All hands report to your battle stations immediately.” The voice of the officer of the deck through the ship’s intercom sternly added, “This is not a drill.” Like my fellow sailors, I hurried to my assigned battle station site with great haste.

Geographically, we were in the northern portion of the Persian Gulf with Kuwait to our left and Iraq to our right. There we were, alone, the only U.S. military deterrent on station. The USS Independence (CV-62) battle group, five days behind us, was still crossing the Indian Ocean. Throughout the first few days of the war, Iraqi fighter aircraft flying across the Persian Gulf toward Kuwait repeatedly locked their missile systems on our ship as if to fire. We, in turn, locked our antiaircraft missiles on their planes. In essence, we were “playing chicken” to see who would fire first. It was an extremely perilous and tense situation with enemy jets in the air and mines floating in the water. Events were further complicated by the fact that U.S. military rules of engagement were not yet in place. Our stress and adrenaline were at the highest level.

A starboard view of the guided missile cruiser USS England (CG-22) en route to the Persian Gulf before the invasion of Kuwait by Iraqi forces. Courtesy of DoD.

A starboard view of the guided missile cruiser USS England (CG-22) en route to the Persian Gulf before the invasion of Kuwait by Iraqi forces. Courtesy of DoD.

Throughout these months at sea in the Persian Gulf, I keenly sensed the danger, but I always felt divinely protected. It is my belief that the apostolic visit to my warship in San Diego by Elder Maxwell a few weeks before we deployed was inspired and preparatory to our entering a war zone. I have wondered to myself, “How is it that out of all six hundred ships in the U.S. Navy, of which only two had a Latter-day Saint chaplain, it happened to be my ship alone at the battlefront on the first day of the conflict?” The same ship that only a few weeks earlier was visited by an Apostle of the Lord. I had the strong impression that the hand of Providence had been at work right from the beginning, before we ever departed San Diego and put to sea.

On my ship of 450 sailors, there were only a small handful of Latter-day Saint sailors, and they were all less active. I was the chaplain for every sailor on that ship but especially for the Latter-day Saint sailors. Every one of the Latter-day Saint sailors became reactivated as a result of this wartime experience. They attended church on the ship and they also accompanied me when we went ashore at Bahrain, Abu Dhabi, and Dubai, where there were Latter-day Saint branches. Attending these local branches was different in that they met for church on Fridays, the Muslim Sabbath. Throughout my time in the Persian Gulf, I noticed a surge of church attendance not only among my Latter-day Saint sailors but also among the other sailors. While out to sea, as the ship’s chaplain, each week I would lead a Latter-day Saint sacrament service, facilitate a nondenominational Christian service, and supervise a Catholic service led by a lay leader. Because I was present at each worship service held on the ship each week, I noticed that the same people were attending all three services. They told me they were simply “covering all their bases.” From this wartime experience in the Persian Gulf, I learned there really are “no atheists in a foxhole”—nor on a U.S. Navy Warship in harm’s way.

As a deployed Navy chaplain at sea, it was my duty to give an evening prayer over the intercom system every night before Taps. Everyone on board the ship heard my daily prayers. I had only sixty seconds to say something meaningful and inspirational in these nightly prayers. It was like a sixty-second sermonette on a gospel principle fashioned in the form of a prayer, which connected to something that had occurred earlier in the day. When I concluded my prayer each night, the boatswain’s mate on the bridge would sound the alert and say, “Taps, taps. Lights out! Unless on shift, hit your rack and go to sleep.” Throughout our many months at sea in the Persian Gulf, the Holy Spirit inspired me every day in what to say in these prayers. From my wartime experience in the Persian Gulf, I learned that the most important battle was not fought on the sands of Arabia but in the heart of each sailor, marine, soldier, and airman.

RUSSELL H. HOPKINSON

Lieutenant Colonel Russell H. Hopkinson graduated from Brigham Young University and Air Force ROTC in December 1986, followed by undergraduate pilot training at Laughlin Air Force Base, Texas. He logged over 4,700 flight hours in KC-10, T-38, and T-1 aircraft. He supported multiple worldwide aerial combat operations including Operations Desert Storm, Restore Hope, and Allied Force. In 2002, he was awarded Daedalian Top Instructor Pilot of the Year at Randolph Air Force Base, Texas. He was also assigned as a faculty member of the Air Force ROTC at Brigham Young University. He and his wife, Suzy, have three children. He has served as an elders quorum instructor, Scoutmaster, and Primary teacher.

Russell Hopkinson's commissioning ceremony at Brigham Young University (December 1986). Courtesy of Russell H. Hopkinson.

Russell Hopkinson's commissioning ceremony at Brigham Young University (December 1986). Courtesy of Russell H. Hopkinson.

During the summer of 1990, the world focused its attention on Iraq. Many military personnel from our ward, including our bishop, prepared to depart with unknown return dates. This left our ward half-manned and struggling for almost a year. As a new U.S. Air Force pilot, I was soon asked to leave my wife and two-year-old son behind when deployed. The next year was spent overseas, in dozens of countries, supporting Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm.

For sixty days prior to the start of the air war, I was deployed to Zaragoza, Spain. As a KC-10 tanker pilot, I refueled all kinds of aircraft as they made their fourteen- to sixteen-hour flights from the United States to their respective destinations in Iraq. I remember being told by the flight operations center commander one evening that “tonight’s mission would probably be on the news tomorrow morning.” We all felt that an actual shooting war would start that night, and it did. When we returned to work the next morning, the news channels were reporting the events we had supported with our refueling the night before.

I wondered, as I watched the reports of death in Iraq, if I had just broken any of God’s commandments. I knew I had definitely helped other pilots drop bombs and kill people with my air refueling support. I resolved this personal dilemma by remembering that Captain Moroni and many other good and noble leaders in the Book of Mormon had also fought for freedom and righteousness. I knew that God does not like war but that he ultimately supports those who fight against evil.

Shortly after the air war started, I was told we were going to a secret location to set up a new air refueling operation. Normally, refueling tankers were stationed in groups of thirty to fifty aircraft with more than enough aircrews to keep the jets flying around the clock. We were informed that only a few aircraft and about ten aircrews would deploy to our new location. I was the only Latter-day Saint in that group. When we arrived at Malpensa International Airport in Milan, Italy, we were told to take our military uniforms and American-looking property and put them in a duffel bag. None of these items were to leave the hangar.

Our commander and intelligence officer told us this flight operations location was reluctantly agreed on by the Italian government. They said there was an unusually high amount of antiwar sentiment in our area. This briefing included information about local Communist party protests and radical antiwar groups known for their violent factions and threats against U.S. forces. We were also briefed on specific threats to our aircraft, like surface-to-air missiles, and how to counter them. Our tanker task force was quickly becoming more than just another air refueling support operation.

We were driven thirty minutes to a hotel at the base of the Italian Alps. German soldiers had used this hotel during World War II as a command and control center until Allied forces bombed it. You could still see bomb damage on the outside of the hotel. The hotel was on top of a hill that rose about three hundred feet above the ground. The entrance and base of the hill were guarded by Italian police who kept out unauthorized personnel. Security was tight.

Night after night, formations of our KC-10s would depart, often through layers of fog, on ten-hour missions, to refuel formations of B-52s [a U.S. Air Force heavy bomber]. We became increasingly stir-crazy and needed a break in the routine. After a few days, the protests and threats seemed to settle down. The intelligence officer said it would be all right if we took short walking trips in the immediate area.

As we left our base, we felt good about getting out. When we approached the shopping area of the small town, I became more vigilant watching the people around us. I made eye contact with a man standing on the other side of an upcoming four-way intersection to my right. I was aware he was watching us from over 150 feet away. He looked to his right at another man and called out something in Italian. The second man looked directly at me and began moving in our direction. The first man and a few others also headed for us. My two companions had not witnessed any of this. The entire exchange only took a few seconds. I was then overcome by an overwhelming message from the Holy Ghost, as clear as a verbal conversation, that I should immediately “turn around and depart now.” I told my companions something was wrong, and our trip to town was over. Before they could ask why, I turned around and headed toward the hotel.

The next day, I was asked to see the commander and intelligence officer. They asked me what had happened in town the day before. I was surprised the commander knew so much about the details of the event since no one, not even the two companions I was with, saw it happen. He told me that the Italian secret police had tailed us when we left our hotel because the threat situation was very high. The Italian secret police became very concerned as we approached the four-way intersection in the small town because they believed we were walking into a trap. They expected to rescue three Americans from a group of known antiwar protestors who had a history of violence. The secret police wanted to know how “that American” knew to turn around at the last minute and return to the hotel. The Italians thought they had an internal intelligence leak since they had not yet told the American intelligence officers about the new threats. They wondered how an American soldier could identify and successfully avoid the troubled area with such apparent, calculated ease.

The commander asked how I knew when to leave, and I told him I had been inspired to do so. He paused for a moment and remarked he was happy we were all safe. He then dismissed me to continue my preparations to fly another combat mission that evening. I have no doubt I had been spared some kind of harm that day. I have never had such direct orders from the Spirit as I did that day in January 1991. The Lord cares for us in all places and at all times, even when we least expect it.

BRENT JOHNSON

Colonel Brent Johnson was born in Rupert, Idaho, in 1962 and grew up in Burley, Idaho. He attended the United States Air Force Academy at Colorado Springs from 1980 to 1984 and was commissioned into the Air Force upon graduation. He spent most of his Air Force career overseas in England, Germany, Hawaii, and Alaska. He deployed to Operations Desert Storm, Deny Flight, Northern Watch, and Southern Watch. He principally flew F-4s and F-15s. He was baptized a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on July 7, 1988, and married his wife, Tamara, five days later.

Kuwait—February 28, 1991

Second Lieutenant Brent Johnson’s initial U.S. Air Force

Second Lieutenant Brent Johnson’s initial U.S. Air Force

pilot training on the T-38 Talon at Laughlin Air Force Base (AFB), Texas, in February 1985. Courtesy of Brent Johnson.

We had just ceased combat actions and were guarding a huge number of Iraqi prisoners of war. There were probably thousands of prisoners, who were being ushered to the rear ranks. We built a small POW pen outside our armored personnel carrier for a few officers and enlisted men. I watched the prisoners for a while. I had a tear in my eye for them, as many were limping and hurting. We gave them food and water.

Some of the American soldiers were trading items with the Iraqi POWs, and I thought, “Well, I don’t want to trade my boots, and I don’t really want their boots anyway, but some money might be a good idea.” So I took my weapons off, gave them to my compadre, and told him to cover me while I went up to the POW fence line. I walked up to an Iraqi major who spoke decent English and asked, “Hey, do you have any money you’d like to trade? Here’s a dollar.” He gave me one Iraqi dinar. I’m sure he got the better exchange rate out of the deal, but that was one neat little souvenir I got out there.

Captain Brent Johnson training on the new F-15E Strike Eagle at Luke AFB, Arizona, in August 1991. Courtesy of Brent Johnson.

Captain Brent Johnson training on the new F-15E Strike Eagle at Luke AFB, Arizona, in August 1991. Courtesy of Brent Johnson.

As Church members, we just need to show care and love no matter who our enemy is. Driving back and forth between Kuwait and southern Iraq, where I was stationed, you would see little children running along and waving at you. It was good to learn that kids all over the world are the same. They have the same dreams, hopes, and aspirations. They just want to be loved. Those kids in southern Iraq, who had just witnessed one of the biggest tank battles in history, were running, playing, and having fun.

THERON LAMBERT

During Operation Desert Storm, Theron Lambert served as an armor platoon leader in D Company, 7/

In August of 1990, I served as a platoon leader with 3-35th Armor of the 1st Armored Division and was stationed in Germany. I awoke one morning and turned on AFN [Armed Forces Network] to listen to the news. The headlines were about the deployment of the 82nd Airborne and the 101st Air Assault Divisions to Saudi Arabia to defend against the threat of an Iraqi invasion. At that moment, the Spirit bore witness to me that I would be deployed. I felt prepared personally and professionally but was concerned because we had just learned that my wife, Cheryl, was pregnant with our first child. During the next several months, I prepared while Cheryl worried. I was the elders quorum president in our branch, and Cheryl was the Relief Society president. There was quite a scramble leading up to deployment. I was busy preparing my troops and quorum, as well as making arrangements for Cheryl to return to the States to stay with her parents while I was deployed. I gave numerous blessings of comfort and counsel to deploying soldiers and their families, but it had not occurred to me to receive a blessing. On the last Sunday before our departure, someone mentioned it to me. I asked two missionaries who were standing nearby if they would give me a blessing. I sat down without telling them about any of my concerns, but nevertheless they gave me a blessing in which they addressed each of my worries—starting with the welfare of my wife and our unborn child and progressing through the spiritual welfare of my quorum members (all but two of whom were deploying), the physical welfare of my platoon, and finally concluding with a promise that I would return safely. The Spirit spoke through them and left me at peace.

We deployed as scheduled in January and spent several uneventful weeks preparing for what was to come. In late February, we moved forward into Iraq. A few days in, I spotted what was obviously a Soviet-made Iraqi BMP2 (a Russian-made armored personnel carrier used by the Iraqi Republican Guard’s mechanized infantry). The thermal signature in our night sights was quite clear, but our commander wanted us to advance closer to confirm the identification. This vehicle was about two thousand meters to our flank and could be dangerous to our Bradley Fighting Vehicles, although it was unlikely it could seriously damage our tanks.

American armored vehicles move across the desert during Operation Desert Storm. Courtesy of DoD.

American armored vehicles move across the desert during Operation Desert Storm. Courtesy of DoD.

The column halted while my wingman and I were sent to confirm it was an enemy vehicle. We moved forward in bounding overwatch [a military term for leapfrogging fighting forces] until we were within eight hundred meters. At that point, the Iraqi crew became alerted to our presence, and we detected movement. I gave the order to fire, and the vehicle was immediately destroyed. I have since wondered if I should have held my fire a bit longer to see if they would have surrendered. Despite my concern for those behind me, I will always wonder if this was the correct course of action.

Later that night, through our thermal sights we spotted dismounted infantry, who quickly dropped out of sight. Again, my wingman and I were sent forward, this time followed by a Bradley fighting vehicle with infantry aboard. Having closed in on the position where we believed the enemy to be, I ordered a machine gun burst to be fired. The Iraqi infantrymen immediately popped up in front of us with hands high above their heads. Our infantry dismounted and collected the prisoners. They were wearing only boots, pants, and shirts and had just one empty canteen between them—no food, no socks, no underwear, and in a trench by themselves. Pitiful.

We continued our movement until dawn. The chronology became a bit hazy after this, as we were short on sleep. We cleared several logistics bases and destroyed a number of vehicles over the next couple of days. I felt good about our accomplishments and performance but was saddened by the necessity of taking some of the lives of Heavenly Father’s children. I worked hard to maintain, and ensured my soldiers maintained, the perspective that the enemy were people with families and value rather than objects or animals. I reminded myself constantly that the enemy were children of God with friends and families who loved them. We would do what was necessary but not glory in it and would always give the enemy a chance to surrender.

On April 3rd or 4th, I received word through the Red Cross that I was the father of a healthy daughter born April 2nd. I returned to my military assignment in Germany on May 2, 1991, and was met by my wife and month-old baby daughter, who had made it back from the United States the previous day. It was a joy to see my wife again and hold my daughter for the first time.

TIMOTHY NORTON

Timothy Norton served as a civilian contractor for the Army. He taught combat leadership. He served on the stake high council in Savannah, Georgia, and Barstow, California, and as a ward executive secretary. He is married and has three children.

I was married with three children—ages ten, eight, and six months. The youngest was my first son. I wrote a letter, which I sent to my mother to give to him when he was twelve if I did not make it back. I remember telling him in the letter to honor his priesthood, to honor his mother and sisters, and to take care of them. I remember telling him how sorry I was that I was not there to teach him how to play football or drive a car. I remember telling him to go on a mission and bearing my testimony of the truthfulness of the gospel. I cried as I sealed the letter.

I had always prayed that if I was ever sent into battle that my unit’s chaplain would be a Latter-day Saint. I knew the chance of that happening was slim to none, so I was shocked when, in August of 1990, a new Latter-day Saint chaplain reported to my unit. Not more than a week later, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, and I knew I would be going to war. Having Chaplain Vance Theodore near was a God-sent blessing. I will never forget when the two of us went into the desert and partook of the sacrament. It was after my battalion commander’s last words and prior to our crossing the berm. The MLRS [multiple launch rocket system] were firing missiles overhead, and artillery battalions were shooting hundreds of rounds into the night sky as Chaplain Theodore and I blessed the bread (MRE crackers) and water (in his chaplain’s sacramental cup) and prepared ourselves spiritually for combat.

* * * * *

We had been in pursuit of the vaunted Republican Guard for twenty-eight hours and had just completed a two-hour firefight in the early hours before dawn. As we raced to cut off the Basra highway, the battalion intelligence officer told us that we had seen the last of our heavy fighting for the day. There would be no enemy for the next sixty kilometers. My tank company had been the advance guard for the brigade since the start of the war. It would be good to relax a little.

“Gray 6, this is Green 4. I have a T-69 [tank] at 3,250 meters, moving southeast to northwest. Request permission to engage.”

“Roger, Green 4. You are clear to fire.”

I looked out over the terrain as Green 4 engaged its prey. The sand there was rolling, with dunes as high as twenty or thirty feet. The sky was dark with an impending storm. As the skyline lit up with the flames from the burning T-69 tank, I projected the path of the destroyed tank to what looked like the mouth of a small valley. I thought to myself that the mouth of that valley would be a perfect place to set up an ambush.

“Guidons, this is 6. Stay alert for a possible armor ambush near the entrance of the valley 3,500 meters to our present position.”

Ten minutes later, all hell broke loose. Boom! Crack! The sound of the 105mm main guns, coming from the four M1s belonging to my lead tank platoon, brought me out of a stupor of thought and back into the here and now.

“Contact, tanks northeast, out!” called the Red platoon leader. The next thing I heard was the loud report of eight M1 tanks going off in volley fire. My Blue tank platoon had pulled alongside Red and was also engaging.

“Gray 6, this is Red 1. Have engaged and destroyed five tanks at grid QU335033.”

This time, there was a note of pride in his inflection. My company had just destroyed five tanks, and it had taken no more than sixty seconds. As my tank passed by the burning hulks, I saw smoldering duffel bags and other personal gear strewn across the desert floor by the explosions that had rocked the tanks. It made me think again how fragile life is in combat. Only moments before, this tank crew had been lying in ambush, waiting to do the same thing to my company. Somewhere in Iraq were the wives, parents, and children of the Iraqis we had just killed, who would now be left with emptiness in their hearts.

And yet I did not feel sorrow or grief. I felt pride. My platoon leaders had acted exactly as I had trained them. It had been a perfect, textbook engagement. It is hard to explain. Somehow, you keep telling yourself that it isn’t right to feel this way, but it had been a fair fight. If anything, they held the advantage, but we had defeated them before they could destroy us. An army trains hard to be the very best it can.

Back when I was in college, my classical literature professor told me something that I will never forget. He was an old Marine, a veteran of the Pacific campaigns during World War II. He told me that although he would never admit it to anyone other than another soldier, combat was the most exciting time of his life. He related how he had never felt more alive than when he was in a firefight. “There is something about being in a situation where it is your skill against your enemy, the ultimate test, with victory for the winner and death for the loser that makes you thrive on every moment.” I could not have said it better.

* * * * *

We were the first soldiers into the town of Safwan, Iraq. We had responsibility to secure the northeast sector of town—the sector closest to the enemy. My M1 tanks had been staring down the Iraqi T-72 tanks, only 1,500 meters from our position, for the last forty-eight hours. Peace talks had been scheduled to begin the day before, but the Iraqis had requested a twenty-four-hour extension.

We set up a checkpoint called Checkpoint Charlie on a highway overpass that controlled the main highway to Kuwait City. Safwan had been a Republican Guard stronghold, and they had withdrawn to the edge of town, waiting for their generals to negotiate the peace before leaving Safwan.

When word got out that the Americans controlled the town of Safwan, refugees started to work their way to our lines. It was a slow trickle at first, like the waterdrop that forms from condensation on the cool side of a glass of water on a hot summer day, but when the Iraqi generals signed the peace accord and the Republican Guard tanks pulled back, that trickle became a flood.

The first people to arrive were in newer model German and Japanese cars. They appeared to be the well-to-do. They were going to take this opportunity to leave Iraq while Saddam Hussein was busy elsewhere. Our responsibility was to search the vehicles and individuals to ensure that they were not carrying weapons or other illegal war material, and then let them continue down the road. Outside of Safwan, the International Red Cross had established an aid station to handle the refugees as they streamed south.

An M-1A1 Abrams battle tank of 1st Armored Division, 7th Corps, moves across the desert in northern Kuwait during Operation Desert Storm. Courtesy of DoD.

An M-1A1 Abrams battle tank of 1st Armored Division, 7th Corps, moves across the desert in northern Kuwait during Operation Desert Storm. Courtesy of DoD.

Soon, however, the refugees we were seeing presented a much different appearance. Our checkpoint started to fill up with the seriously injured, the homeless, and little children who had no one to take care of them. They arrived packed into anything that could move: an old school bus, a dump truck, and even cattle cars. We still had to search them because our military mission came first. Nevertheless, I had my medic provide immediate first aid. Each platoon fought for its turn to give the kids various little gifts of food and candy they had saved.

Here is an example engagement: An old truck would pull up to the dismount point. Depending upon what time of day it was, the vehicle might have been in line for two or three hours. The truck would normally be overheating, with steam billowing out of the radiator. One of my soldiers would motion to the individual driving to step outside while at least one Bradley Fighting Vehicle and one tank kept their main guns pointed at the vehicle to provide security. The driver was usually an old man, dressed in traditional Arab garb, not able to speak any English. The driver would always smile, bow, and attempt to strike up a conversation. My soldier would attempt, the best he could, to explain to the driver that he needed to have all the passengers in the back of the truck get down on the ground. Once this was accomplished, my medics would treat any wounds while another team of soldiers searched the vehicle and the occupants for contraband.

My medics treated everything from amputations to broken bones. I still remember a little boy who was no more than four or five years old. An Iraqi soldier had shot him in the hand. Our language barrier did not allow me to determine why he had been shot. The wound was over twenty-four hours old. His older sister had wrapped a rag around the hand to stop the bleeding. My medic unwrapped the dirty, blood-soaked rag covering the child’s hand. Several bones in his hand were broken, but he never cried or made a sound. He just looked as my medic washed and then tenderly bandaged his hand in gauze. There wasn’t much else that could be done.

A coalition special forces soldier inspects an Iraqi trench for enemy soldiers during Operation Desert Storm. Courtesy of DoD.

A coalition special forces soldier inspects an Iraqi trench for enemy soldiers during Operation Desert Storm. Courtesy of DoD.

Another of our missions was to destroy all the military equipment in the surrounding countryside. Since this had been a Republican Guard stronghold, it seemed you could not take five steps without discovering some underground bunker filled with ammunition or military equipment. Some of those bunker complexes were quite sophisticated, containing two or three levels and several rooms.

We were searching a dump truck carrying twenty-eight women and children when one of my engineers blew up some recently discovered bunkers. Suddenly, the children started to cry and clung to their mothers. The mothers, not understanding the nature of the explosions, looked at us with fear in their eyes. One little three year old, who had no one else to go to, wrapped her frail, tiny arms around my leg and cried. I reached down to comfort her while she repeated the words “No bomba! No bomba!” How could I explain that everything was going to be all right? I reached into my pocket and pulled out the last piece of See’s hard chocolate candy that my sister had sent me. I slowly unwrapped it and handed it to the small child, who had chosen me as her guardian. She smiled, placed the candy in her mouth, and continued to let the tears fall on her round little cheeks.

I wish we could have done more to help the refugees. We gave them what food and water we could spare. My maintenance sergeant even put a couple of gallons of gasoline into one old man’s pickup so that he could make it to the Red Cross camp, but we were only a temporary solution at best. We could not spend much time with any one group, and we never let our guard down. We daily caught Iraqis trying to sneak through our lines with weapons and explosives. We even had to stop one group of Iraqis from trying to cross our lines in a Soviet combat vehicle. I only wish that I had been able to provide more care and tenderness to the children I met at Checkpoint Charlie.

RICHARD REYNOLDS

Rich Reynolds is a retired colonel in the United States Army. He is a graduate of Brigham Young University with a degree in European studies. He served many tours in Middle Eastern countries.

Newly arrived Marines move through an airfield encampment during Operation Desert Shield.

Newly arrived Marines move through an airfield encampment during Operation Desert Shield.

Courtesy of DoD.

The First Gulf War was about liberating Kuwait. When I went into Kuwait City, it had been looted and, in many ways, destroyed. The hotels had their carpets, wires, and lights stolen. Anything of value had been stolen by Iraqi soldiers and taken north to Iraq. The Iraqi Army had been allowed to loot, rape, and pillage in Kuwait, and they had done so to tremendous effect. I worked with the Kuwaiti resistance forces during that war. Many of them suffered through horrible situations. The acts of debauchery and violence were unspeakable. The Kuwaitis were ecstatic to have us there. It was difficult to travel in Kuwait City because people were continually wanting to thank me, invite me to dinner, or do whatever they could to show their gratitude.

I was later assigned to a Kurdish area, and one of my responsibilities was to fly a helicopter to an Iraqi Army base and meet with Iraqi generals to talk about the situation in the north. As soon as I arrived, the Iraqi generals complained that the American fighter planes flying overhead were waking up Iraqi babies, causing them to cry. I explained that Kurdish babies seemed to sleep much better when our fighters were in the air.

DAVID A. SAWYER

Dave was an Air Force pilot for twenty-nine years. He served in the Church as a counselor in a stake presidency, a counselor in a bishopric, a Gospel Doctrine teacher, a Scoutmaster, and a choir director. He commanded the “Flying Tigers” during Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm. He was a major general serving in the Operations Directorate of the Joint State in the Pentagon at the time of his death in June 1997. He married Jeanne Tucker in 1967, and they have six children.

Selected Journal Entries

October 15, 1990

I arrived here on 31 August 1990 after flying across the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean.

October 16, 1990

Flying was fun today. I hadn’t been up in over a week. Went to the north CAS [close air support] area for the first time and ran simulated attacks against a whole bunch of U.S. armored units about halfway to the Kuwaiti border from here.

January 12, 1991

This was a very eventful day. Brig. Gen. Buster Glosson, my new commander of the 14th Air Division—all the fighter wings in CENTAF [Central Air Force Command]—came to King Fahad [a Saudi Arabian air base] and briefed all our pilots on the offensive plan to take down Iraq. Those of us in the A-10s would have a big part of that action, particularly in dismantling/

January 13, 1991

Well, two more days until the January 15 deadline for Iraq to pull out of Kuwait. Our pulses are up here, with some intelligence reports indicating Saddam will preemptively attack around 3:00 a.m. Tonight we further discussed the offensive plan. I will be flying early on the first day. . . . I will fly smart—too much riding on all this. Leadership by example is good, but if my example is not effective, I’ll do more harm than good. After day one, we’ll have around ninety new combat veterans in this seven-squadron A-10 force.

Monday, January 14, 1991

One day to go to the deadline! It’s actually midnight, Eastern Standard Time USA, so it will be 8:00 a.m. here (and in Baghdad). I don’t expect a U.S.-led offensive to start on the 16th. We’ll probably wait a few days for good weather (still raining here). I got all the support troops together in tent city and talked about the final preparations. It went well. I asked for a show of hands of those who had been to war before—there were four of us, which gives us credibility.

Tuesday, January 15, 1991

We received a warning order to implement the offensive against Iraq. Looks like war for sure. I spent a lot of time in the two 23 TFW [tactical fighter wing] squadrons giving last-minute advice to pilots and getting ready myself. I will be the first 76 TFS [tactical fighter squadron] vanguard flight. . . . I stayed up until 3:30 a.m. finishing letters to all the kids and Jeanne. I wanted them to have a precombat record of my thoughts—even Daniel. It felt good to put my love down on paper. They all mean the world to me, and I miss them terribly.

Wednesday, January 16, 1991

We received the executive order to go offensive. I’ll be flying three sorties against Iraqi infantry and armor divisions. . . . Everyone seems ready and eager. There was some joking around, but mostly the mood is serious—professional. We’ll see a dramatic growing-up process in the next few days. For now, I’m beat and going to bed. The next entry should find me a veteran of combat in my third aircraft type.

January 17, 1991

And so, it came to pass. I flew three sorties today. We fired three Maverick missiles (infrared version) at large trucks, one of which may have been carrying a FROG [free rocket over ground] surface-to-surface missile. One of the trucks was moving at great speed with another about five hundred yards behind. The Maverick scored a direct hit on the lead truck, which brought the second truck to a screeching halt. I then put another missile directly on the second truck—I’m sure the driver was long gone. I tried to strafe another moving truck (about two-and-a-half-ton size) but couldn’t hit it from the ten thousand feet range. It wasn’t worth going closer into antiaircraft fire. We saw a few sparkles from the ground, so I’m sure we were being fired upon. Some of the pilots saw quite of a bit of fire.

Saturday, January 19, 1991

We are wearing protective overgarments that have charcoal inner lining. The charcoal sloughs off and makes our fingers and faces perpetually dirty. Better dirty than “slimed” by mustard gas! A chemical attack is very unlikely—but possible. Effective chemical attack is even less likely. We’ll take off these overgarments once we’re very confident the chemical threat is virtually gone. Iraq lobbed three more missiles into Israel today. There were no deaths, just three minor injuries—one landed in a high school gym, for crying out loud. These Scuds have infinitesimal military effectiveness, but they’re great terror weapons. It was a long day today helping run the war.

Sunday, January 20, 1991

Tonight, we had three Scuds launched at Dhahran [a town in southeastern Saudi Arabia], all shot down by Patriots at about 9:50 p.m. I saw the streaks across the sky and heard the booms of the Patriots engaging the Scuds. It sounded like thunder. Then, around 12:30, it happened again. We also had between three and five missiles shot at Riyadh. There were no injuries, as all were intercepted by Patriots!! Hooray for the Army!

Monday, January 21, 1991

A flight from Myrtle Beach ran a search and rescue operation for an F-14 [a U.S. jet fighter] pilot: they not only found the downed pilot and escorted the rescue helicopters in, but they also blew away a couple of enemy vehicles that were driving up to the survivor—only about two hundred yards away! They literally saved the day! That was good news. The bad news was that some captured Allied pilots (American AF, Navy, and Brits) were paraded on Iraqi television. It was a typical propaganda show—subdued pilots, some with bruised faces, reading stilted statements about aggression against “peaceful Iraq.” This is actually good news, because if any of our guys get shot down, they’ll at least be captured and not killed. It’s getting personal.

Saturday, January 26, 1991

I stayed up all night Friday to supervise the operation. We had three Scud launches—actually two and one false alarm. One person was killed at Riyadh and Tel Aviv, so Saddam has killed his first enemy. We’re taking enormous pains to avoid civilian casualties while Saddam targets cities, deliberately trying to kill civilians. These are the acts of a desperate man. Today he pulled his most evil stunt so far. His troops are deliberately dumping about 100,000 barrels of crude oil per day into the gulf! The slick is now thirty miles by eight miles big and drifting along the coast. It’s ecological terrorism, and it really sickens me.

Saturday, February 2, 1991

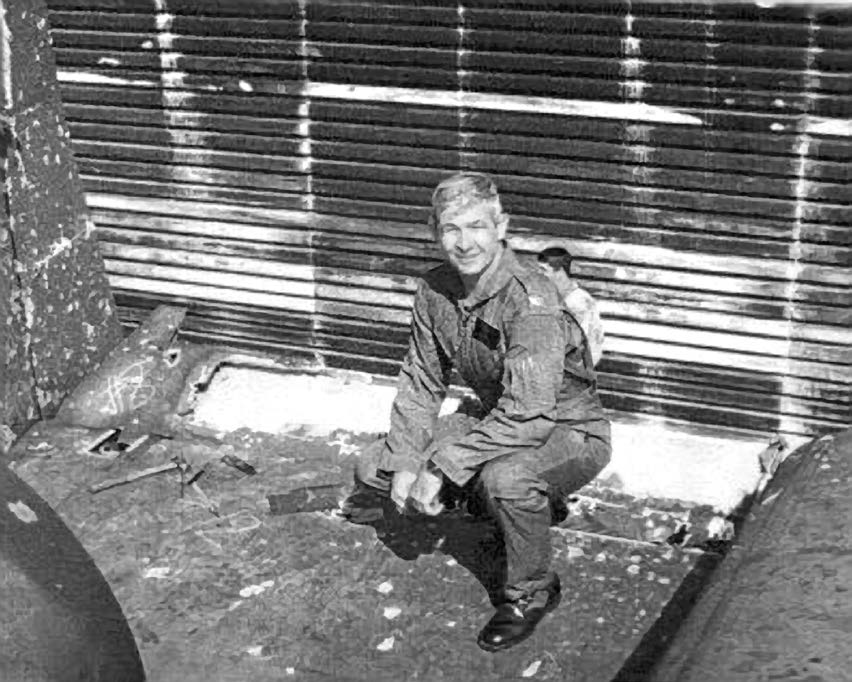

Dave Sawyer on top of the damaged tail of his A-10 aircraft. Courtesy of Jeanne Sawyer.

Dave Sawyer on top of the damaged tail of his A-10 aircraft. Courtesy of Jeanne Sawyer.

Today, I don’t like my job very much. I had to do the worst thing a wing commander has to do—deal with the loss of a pilot and an aircraft. Capt. Dale Storr apparently got hit by AAA [antiaircraft artillery] fire and rode his aircraft in. The wingman was Lt. Eric Miller, who saw the whole thing. Dale was recovering from a strafe pass, nose high left bank, when Eric saw a puff of black smoke come from Dale’s airplane. Eric asked him if he’d popped a self-protection flare or something. No answer. Dale started a descent (more of a drift actually) and Eric told him to get his nose up. Still no answer. Eric told him to eject, several times—no answer, no recovery attempt, no ejection attempt. Eric watched him all the way to impact. The crash site is about seven miles inside Kuwait. . . . Since the eyewitness account was so clear (not even a momentary loss of sight of the aircraft) and the chances of survival virtually zero, we elected not to try a rescue. It was not worth losing six more lives. We’re hoping a ground party can get to the wreckage in a day or two. . . . It’s such a shame. Pilots will be ready to go again tomorrow. The job’s got to be done. I’m scheduled Monday—won’t be a problem. But I sure want to come home alive. I need to see Jeanne and our precious children again. It would be awful to die after six months of not seeing them. It would be better to have some terminal illness where at least you could say goodbye.

Tuesday, February 5, 1991

It may not be as bleak as we initially thought on Dale Storr. Some classified sources I can’t talk about here indicate he may have been captured. More on this later.

Tuesday, February 12, 1991

This was an uneventful day. I changed the status of Dale Storr to missing in action [MIA] and called his mother and brothers out in Spokane. They were very understanding and seem to be taking all the uncertainty very well.

Thursday, February 14, 1991

Valentine’s Day. Any guess where I’d rather be today? Not too hard to figure out, eh? I sent some roses and a poem to Jeanne. Hope she likes them.

Friday, February 15, 1991

She did. I had another reason to call her today. I flew early this morning, going further north than I had ever been before. My wingman was Karl “Bugs” Buchberger, a captain fairly new to fighters and to the A-10. We had a preplanned target in the Republican Guard Tawakalna division, right near the Division Headquarters, which is in Iraq, near the Kuwait border. Our target was a tank battalion. We found the target area just fine—a beautiful day. Good delivery of our CBU [cluster bomb units] right on target on some storage vehicles in bunkers, and then I put a Maverick in a tank in a ditch. I saw three people run from the bunker I hit; they were heading for the next ditched vehicle, so I strafed that vehicle, and then climbed up to give the wingman a chance to shoot his Mavericks. Unfortunately, during the climbing turn, I took a very bad hit from a surface-to-air missile (we think—came to that decision later today after examining the aircraft). I felt a jolt in my feet and heard a muffled clank. At first, I thought I’d taken a hit under my feet because that’s where I felt it. I immediately checked my engines first. It panicked me a little that it was becoming quieter, but after I assured myself that the RPM, temperature, oil pressure, and hydraulic pressures were all good, I figured it was only getting quieter because I was climbing and slowing down. I was about forty-eight miles from friendly territory, so it took us about twelve minutes to get there—a long flight. After we crossed into Saudi Arabia, I had Karl fly in close and check me out. Both rudders were heavily peppered with holes, and the right rudder middle hinge was broken with the rudder bowed out. The right elevator was 90 percent blown away. Fortunately, the left elevator was mostly there, so I had pretty good pitch control. I flew back uneventfully and smoothly, so I didn’t put any strain on the flight controls, and performed an uneventful controllability check and landing. The pitch control was a little stiff, but everything else felt normal. After I climbed out of the airplane and got my first look at it, I was amazed at how much damage there was! The tail end was also shredded and hanging down by a thread—about the last foot or two. There are probably about two hundred holes in the airplane—also some in the engine. The miraculous thing is that there was not one hydraulic line or control cable damaged, much less severed! God was really watching out for me today. President Baher of the Alexandria Stake promised all of us at Eglin Air Force Base that we’d come home safely. I surely put that to the test today! I’m not proud of taking the hit—I obviously made one pass too many. But I feel I did a good job and kept cool. Unfortunately, two Myrtle Beach 354 TFW [tactical fighter wing] pilots weren’t as lucky this afternoon. Two pilots in the same flight were shot down, probably by missiles also. . . . What a terrible day!

Sunday, February 17, 1991

Very nice church meetings today. I’ve had dozens of people come to me and tell me to be careful. My battle damage was really extensive yet not that serious. My aircraft already has a new tail on it, from [a] New Orleans Jet. It looks really funny. I’m getting lots of kidding about it already.

Tuesday, February 19, 1991

Damage to the tail assembly of Colonel Dave Sawyer’s A-10 (Warthog) aircraft. Courtesy of Jeanne Sawyer.

Damage to the tail assembly of Colonel Dave Sawyer’s A-10 (Warthog) aircraft. Courtesy of Jeanne Sawyer.

Darn! We lost an OA-10 today. Lt Col Jeff “Sly” Fox, the ops officer of the 23 TASS (Tactical Air Support Squadron) was the pilot. He’s been captured by the Iraqis. The first anybody knew he was in trouble was a mayday call on Guard [emergency] channel, where he said he’d ejected and was on the ground. Just a few seconds later he said there was a guy with a gun coming toward him. Two minutes later he was captured, saying, “Too late, guys. He’s here.” Jeff was flying by himself, so no one else was around. I can’t figure out how he was shot down. His brother was notified first, then his sister and elderly father. Terrible days. We got a call from Gen. Glosson, who said the war’s going to last only another three weeks, that Iraq is on its knees. I hope he’s right. I don’t want to lose any more guys!

Wednesday, February 27, 1991

Today turned out to be the last day of the war. We should be beside ourselves with celebration, and would be if it were not for an awful tragedy. Lt. Patrick Olson (“Oly”), an OA-10 FAC [forward air controller] from Davis-Monthan, whom I know very well, died today when he crashed his battle-damaged airplane trying to land at KKMC [King Khalid Military City]. We could have saved him from himself if we had known how serious his situation really was. We knew he was in manual reversion, meaning he’d lost both hydraulic systems, but we figured he’d be able to land safely. Oly was committed to landing that aircraft, and he rushed the approach and put himself in a fix. The approach looked normal to some eyewitnesses, steep to others. It seemed alright until the last little bit when he developed a steep descent rate in the last seconds and hit the runway hard. His right landing gear collapsed, the right wingtip hit the runway, and he rolled upside down while getting airborne again and then landed upside down in a fireball. On the last day of the war—how very tragic.

Thursday, February 28, 1991

The cease-fire is holding. My last combat mission was Monday, which was kind of anticlimactic. I flew as #2 with Tom Coleman, Squadron commander of the 706 TFS [tactical fighter squadron] from NAS [Naval Air Station] New Orleans. Our first mission was good, supporting U.S. army tanks and armored personnel carriers against Iraqi artillery positions. We bombed some artillery positions, and I shot one tank. I would like to have worked longer, but I ran out of self-protection flares. That’s how I got shot up—not flaring enough. So we had to knock it off—we were almost out of gas anyway. On our second mission, we couldn’t get to the target area because of clouds. Tonight, we had a very nice memorial service for Oly. It was extremely moving, especially when Oly’s roommate read a letter Oly had written, which he wanted read in case he died. His Squadron Commander Lt. Col. Bob George gave an emotional tribute.

Monday, March 4, 1991

Time flies when you’re having fun. The cease-fire is still holding, and some POWs were released today in Baghdad. We got news that Dale Storr was a “fellow POW” with CBS newsman Bob Simon. This is really good news. . . . Gen. Glosson came by yesterday and talked to the troops, offering them some nice words of congratulations. He also said we’d be out of here fast, probably within two weeks after the actual cease-fire is signed. Come on, guys, let’s sign quickly!

VANCE P. THEODORE

Chaplain (Colonel, retired) Vance P. Theodore entered active duty in January 1984. He served in the 1st, 3rd, and 7th Infantry Divisions. He was an instructor at the School of the Americas, Fort Benning, Georgia, and served as the XVIII Airborne Corps artillery chaplain, installation chaplain at Fort Wainwright in Alaska, and as the Army Air Missile and Defense Command chaplain at Fort Shafter in Hawaii. He earned a PhD in human ecology at Kansas State University in 2011. He is married to Christine Clark of Berkeley, California. They have five children and eleven grandchildren. He is currently the associate graduate coordinator for the Master of Arts in Chaplaincy program at Brigham Young University.

During my first four years as a young chaplain, I belonged to the fifth of the twenty-first infantry battalion, part of the 7th Infantry Division. I was proud to serve with them. We had mottos like “Pack light—freeze at night.” I learned to love the men I served with. I remember having an interview with Elder Gene R. Cook, a member of the Seventy. He sat me down and said, “Vance, whenever you go into a commander’s office or first sergeant’s office, I want you to stop outside of that office, and I want you to ask, ‘Father, what would you have me do?’” I used that motto throughout my whole career.

I was a young chaplain captain in an armor unit, and we were getting ready to go to war. I remember going to the railhead, being with the men at two o’clock in the morning. I would always sweep my unit. Sweeping the unit means that before I went home, I would walk through the unit work areas—such as the motor pool, go to the offices, talk with commanders, and so on. I called it sweeping, just so they’d see my face. It was quick.

When we deployed to Desert Storm, I was involved in an intense battle, probably one of the most intense tank battles since World War II. We had the 24th Infantry Division to our left flank and the Brits to our right flank. We were the breach battalion. The breach battalion was the battalion that was going to breach the berm and go into Iraq. We were going to clear the mine fields, and I was their battalion chaplain. If you want to picture combat, just picture mines and clearing minefields. You’re on a lane and staying in your lane because if you get off the lane you might set off an explosion.

The previous week we had been asked to take some commo [communication equipment] about fifteen kilometers to a small village in Iraq. This is the routine of a chaplain. My guys were doing their preparatory battle checks. While they were doing that, I went to each Bradley [Fighting Vehicle] and offered to have prayer with the service members.

They were scared young men—concerned about going into battle. One soldier said, “Hey, chaplain, come here!”

“Okay,” I said.

He was sitting on an MRE [meals ready to eat] box, and said, “Hey, Chaplain Theodore, you got one of those Bibles that has one of those metal covers on it?”

“No, I don’t have one of those. They got rid of them after World War II.”

“You got one of those crosses?” he asked.

“Yeah,” I answered, “I’ve got a cross.”

“You wouldn’t happen to have a Star of David, too, would you?”

“Sure. I’ve got a Star of David,” I said as I handed it to him.

“You wouldn’t happen to have some of those prayer beads the Muslims use, do you?”

In my mind I thought, “Hey, what’s going on here?” But you have to realize that you don’t question soldiers when they’re going into combat. You just try to help them so I gave them to him. Then he said something I’ll never forget.

“You know, chaplain, you just can’t be too careful.”

Then we received a particularly hard assignment where we could have been killed. I monitored the radio. All of a sudden, I heard a tremendous amount of fire. You hear the machine guns—pop, pop, pop, pop, pop! You can hear all the chatter and scatter on the radio and soldiers screaming. When it was over, I remember talking to the commander and learning they had just destroyed a village. Fortunately, the villagers saw us coming and ran away first.

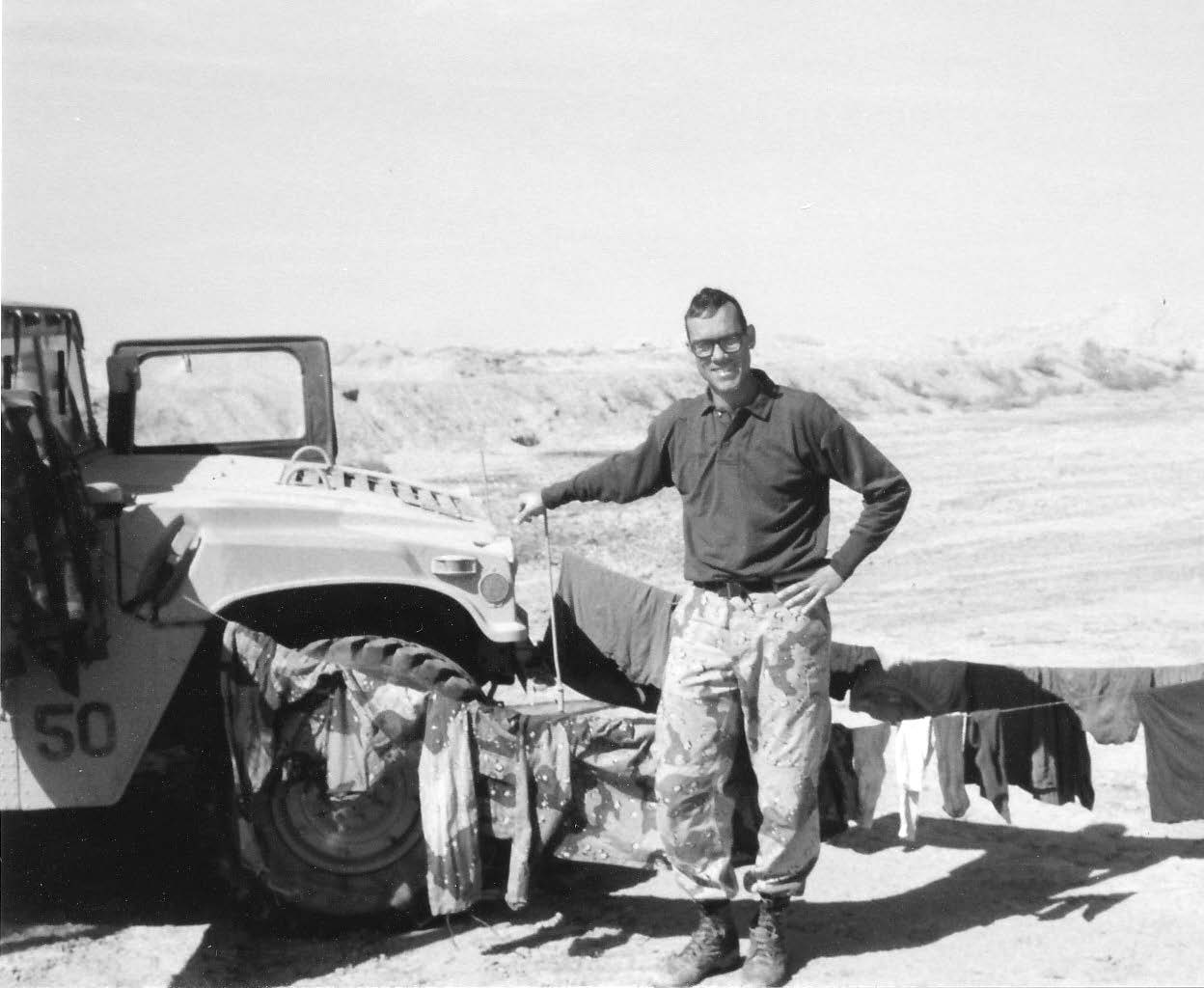

Latter-day Saint chaplain (Captain) Vance Theodore on wash day in the Iraqi desert. (This was not the day he dyed his uniforms pink.) Courtesy of Vance Theodore.

Latter-day Saint chaplain (Captain) Vance Theodore on wash day in the Iraqi desert. (This was not the day he dyed his uniforms pink.) Courtesy of Vance Theodore.

Chaplain (Captain) Vance Theodore preparing for Easter services in an open field in Iraq. Courtesy of Vance Theodore.

Chaplain (Captain) Vance Theodore preparing for Easter services in an open field in Iraq. Courtesy of Vance Theodore.

We had a friendly fire casualty. One soldier was shot in the leg. After that incident, the battalion commander took all six hundred of his soldiers before we crossed the berm into Iraq and talked to them about command and control. We never had another friendly fire incident. It was only a four-day battle, but there was an intense amount of conflict. When you’re in combat, it’s just very intense. But, surprisingly, I never felt scared. In fact, I would tease all the tankers because they were all safe. I drove on the battlefield in a hummer. A .50 caliber machine gun could slice through my vehicle like butter. We would always laugh about it.

I remember being in the aid station. We didn’t have any casualties from our soldiers because we were very protected, but we inflicted a lot of death. When we crossed the line, we were going at thirty kilometers per hour. We destroyed fifty-nine tanks. The carnage—I try not to think about it—was terrible.

Combat is horrible, and my men would come to me for comfort. I remember one particular scene when I was traveling about one hundred meters behind my men, so I could see everything, the battlefield and the death. One event broke my heart. An Iraqi T-72 tank had just popped its tank cover, and a white flag was starting to poke out. Just in that instant, it was destroyed. Those things are hard.

After a battle is over, the job of chaplain is to minister to prisoners of war. We took over a thousand prisoners on the first day of battle. It’s a tremendous amount of work. We were traveling and engaging the enemy at thirty kilometers an hour. At the same time, we were taking prisoners. I was trained and knew what you did with prisoners of war. I knew the procedures. First, you separate the officers. My job was to make sure that they were being taken care of adequately. If I saw soldiers abusing the Iraqi prisoners of war, I stopped it.

You have the thousand prisoners. Smoke was everywhere. It was surreal. It broke my heart to see how the Iraqis were treated by Saddam Hussein. As a chaplain, I was kind of like their grandpa. You would see improper things that some of the soldiers tried to do, and you stop them when necessary. Anytime we found an Iraqi dead, we catalogued the death, recorded GPS coordinates, and buried the person with respect. Then we gave the coordinates to the Iraqis when they signed the peace treaty so they could retrieve their dead.

During Desert Storm there were some funny things that happened, too. My wife had sent me some white socks. When you’re going to war, your command sergeant puts out a packing list, and you have to take all that stuff. We needed so many black socks. But the First Infantry Division had taken all the available socks. There were none left. So my wife came up with a brilliant idea. She would dye my white socks black. Brilliant! She dyed them, and I thought that I was good to go. When I was in the desert, I had my Hummer, and I got to wash once in a while. I had a plastic tub, and I washed my uniforms and black socks together. I looked at the water, pulled out my uniforms, and saw that they were now pink! My wife had actually dyed my socks with purple dye. They looked black, but now all of my uniforms were pink. My unit laughed at me for two weeks. “Hey, chaplain, where did you get those pink pajamas?” They provided a lot of comic relief.

I remember once I hadn’t taken a shower for three months, and my wife had sent me a beautiful black bag. You could put it on a tank or armored carrier, and the sun would heat the water. Then you could put it over your head and take a hot shower. I was really looking forward to having a shower. One of my soldiers at the aid station saw it and said, “Hey, chaplain, can I borrow that?” I let him borrow it and told him I would get it back that evening. I was thinking about a hot shower all day long.

When I returned to the area that evening, the specialist came up to me and looked like a lost soul. I thought, “Oh no. Someone’s been killed.” I asked, “What’s wrong?” and he pulled out my little shower bag. It was completely melted. He sheepishly explained, “I was taking a shower, chaplain, and the exhaust pipe on the armored carrier melted it.” I burst out laughing and said, “Well, at least somebody had a good shower!”

In combat there are also touching things that happen. I remember three Iraqis coming across the berm with their weapons. One of the Iraqis reached into his pocket. Quickly the turret and machine gun of an M1 tank and numerous M16 rifles were pointed at the three Iraqis. I was standing close to one of the Iraqis who started to tremble. You could see his body shaking. He pulled his hand out of his pocket, and he extended it to a nearby American lieutenant. The Iraqi opened his hand, and inside were three M&M pieces of candy. Fortunately, it was just candy, and the soldiers and Iraqis laughed.

A soldier carries his gear after arriving in Saudi Arabia during Operation Desert Shield. Courtesy of DoD.

A soldier carries his gear after arriving in Saudi Arabia during Operation Desert Shield. Courtesy of DoD.

I also remember how my men almost killed me. We were blowing up Iraqi T-72 tanks after the conflict was over (you put the C4 charge in and then blow them up). I was out visiting soldiers, and we drove through a wadi [dry ravine]. All of a sudden, we were receiving fire as rounds started ripping through my vehicle. I was clearly under attack. I got exasperated. My chaplain’s assistant floored the Hummer, and we got out of the kill zone as quickly as possible. When it was over, I saw American infantry soldiers running toward me. I was ready to light a fire under them. They thought that they had just killed their chaplain. When they saw me, they fell on the ground and started laughing hysterically. They said, “Chaplain Theodore, we thought we killed you.” They just kept laughing and laughing. That’s kind of the life of an infantry soldier. You love them—most of the time.

After the conflict was over, we began deploying home. One of the roles of the chaplain after combat is to take care of the wounded. It doesn’t matter who they are. I was tasked to take care of wounded Iraqis. I went to a field hospital station and was told, “On order, chaplain, be prepared to move out. You’re going to spend a week at a field hospital station,” in the middle of nowhere. I held Iraqi hands that were beaten up by battle, talked to them, and tried to soothe them. I spent a week there. War is not humane. It’s nasty, but I experienced only a little bit of it, so I’m not an expert.