What in the World Was Going On?

Michael Harold Hyer, “What in the World Was Going On?,” in Saints at War in the Philippines: Latter-day Saints in WWII Prison Camps (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 21‒26.

God moves in a mysterious way

His wonders to perform;

He plants his footsteps in the sea

And rides upon the storm.

—William Cowper, “God Moves in a Mysterious Way”

What in the world was going on that would make the Philippines, an economically insignificant group of islands in East Asia, an assignment of great importance to the United States? Why were these soldiers sent more than seven thousand miles from their homeland? In a scenario that would seem all too familiar to us in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, it involved oil.

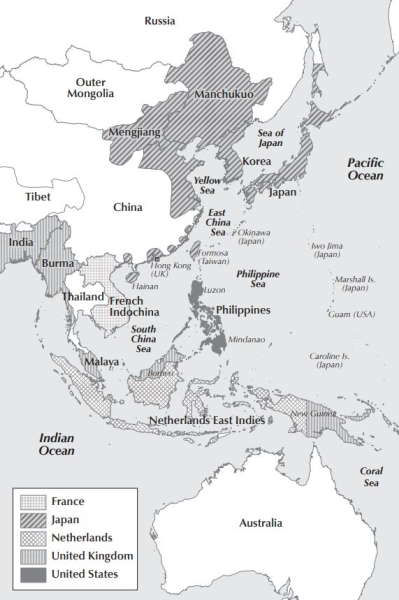

Map 1. Political Map of the Far East in 1939. Map by Nat Case.

Map 1. Political Map of the Far East in 1939. Map by Nat Case.

The Old Colonial Economic Order

In the years preceding WWII, Asia still contained the remnants of the once-great European colonial empires of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. There were British colonies in what are now India, Pakistan, Malaysia, Singapore, Myanmar (Burma), and Hong Kong; French colonies (French Indo-China) in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia; and Dutch colonies (Netherlands East Indies) in what is now Indonesia. While the United States never developed a colonial system like these European powers, as a result of the Spanish American War in 1898, it came into possession of the Philippines and joined these European colonial powers in having significant economic and political interests in Asia.[1]

The Oil Embargo

In the years leading up to WWII, an emperor nominally ruled Japan, but an ultranationalistic military was the dominant political force and viewed itself as Asia’s champion, destined to liberate the Asian colonies from the Westerners and expand Japanese influence through its “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.”[2] What the Japanese viewed as liberating Asia from these Western colonial powers, others saw as Japan simply building its own colonial empire following this European model, especially since Japan lacked the natural resources necessary to fuel its growing economy and imperial ambitions.[3]

In 1937 Japan invaded China, a country with which the United States had a longstanding friendship and commercial trading relationship at the time. To pressure Japan to withdraw from China and halt its expansionist actions, on July 26, 1941—just days before the 200th regiment shipped out—the United States imposed a full embargo on trade with Japan, including all oil imports. At that time, most of Japan’s oil imports came from the United States. Britain and the Netherlands imposed similar embargos.

The Japanese, however, had no intention of withdrawing from China or halting its drive for a Japanese-led “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” Japan and the United States had been holding diplomatic negotiations to resolve the conflict, but with the full trade embargo, those negotiations deadlocked.[4] While the Latter-day Saint soldiers were enjoying their voyage across the Pacific, Japanese military leaders were planning other, nondiplomatic solutions to their problem.

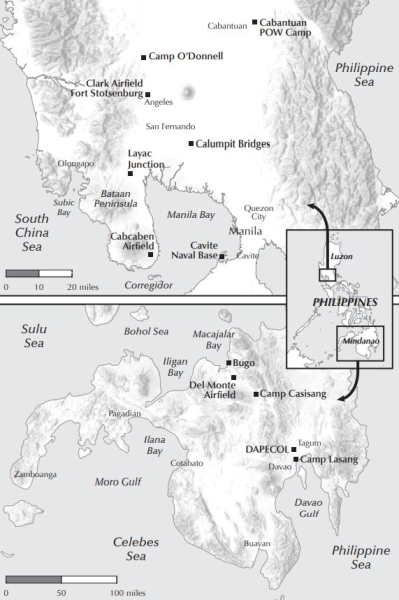

Geography now became important to the fate of these Latter-day Saint soldiers on their way to the Philippines. The Philippines archipelago comprises almost seventy-one hundred islands. Located more than five thousand miles from Hawaii and seven thousand miles from San Francisco, these islands are situated in the middle of the Far East and lie athwart the trade routes leading from China and Japan to Southeast Asia and the rich supplies of rubber, oil, and minerals in the East Indies.[5] One of the most promising sources of oil for Japan’s growing military and industrial appetite was the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). However, the Philippine Islands sat between Japan and that source of oil. The US Navy’s Pacific Fleet sailed those waters, and any oil-laden Japanese ship going from the Dutch East Indies to Japan would have to pass by the US-controlled Philippines.[6]

War Plan Orange

United States military planners for many years had been preparing and revising plans to defend against a potential war with Japan. War plans were color-coded, and Japan was assigned the color orange. War Plan Orange (WPO) was the plan for defense for war with Japan.[7] The Philippines was something of a conundrum for the military planners. The core line of defense of the continental United States was an arc from Panama through Hawaii to the Aleutian Islands off Alaska. The Philippines was thousands of miles west of that defensive line. The problem for defense planners was how to reinforce and supply the military outpost in the Philippines in the face of a Japanese attack and naval blockade.

WPO assumed the Philippines would be able to defend an attack for six months, by which time the US Pacific Fleet would have battled its way across the Pacific to reinforce the troops. However, no one with any authority actually believed that could be done. The navy estimated it would take at least two years for the fleet to fight its way across the Pacific. Although never explicitly stated in the war plans, the implicit conclusion was that the Philippines would have to be abandoned in the event of a war with Japan. In any event, no plans were made to concentrate men or stockpile supplies on the West Coast in preparation for such an attack.[8]

In the summer of 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt brought General Douglas MacArthur out of retirement and put him in command of what was then called the United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE), with its command center in Manila. General MacArthur, a charismatic and highly regarded general with unquestioned knowledge of East Asia, was a strong advocate against the defeatist attitude of WPO and a forceful proponent for the reinforcement and defense of the Philippines.[9] A key element of General MacArthur’s strategy to defend the Philippines was the use of the then-new ground-based B-17 four-engine, heavy bombers (the Flying Fortress).[10]

General MacArthur’s view ultimately prevailed, and WPO was changed. The War Department identified the Philippines as a “strategic opportunity of utmost importance” and contemplated that it would be the key to the US strategic position in the Pacific. The War Department recommended that the Philippines be reinforced by antiaircraft artillery to protect the airfields and bombers that were key to General MacArthur’s strategy.[11] The 200th (with Brown and Hamblin) and the Fifth Air Base group (with its group of Latter-day Saint air corpsmen on their way to the Philippines) were tactical pieces in this larger Pacific strategy.[12]

Map 2. Luzon and Mindanao Islands in the Philippines. Map by Nat Case.

Map 2. Luzon and Mindanao Islands in the Philippines. Map by Nat Case.

Despite official neutrality (and a general isolationist sentiment among the public), President Roosevelt’s administration was nevertheless simultaneously preparing for war with Japan in the Pacific and with Germany in Europe. Yet it is hard to imagine today how unprepared for war the United States truly was, especially for war on two fronts. In 1938 the United States ranked nineteenth globally in the size of its total air and land forces, just behind Portugal and slightly ahead of neutral Switzerland.[13]

The accelerated buildup for war on two fronts exceeded the nation’s logistical capacity, creating an epidemic of shortages and mistakes. It is not surprising that the intended buildup in the Philippines would turn out to be more of an aspiration than fact. For example, pilots would arrive but not their airplanes, and the planes that did arrive often lacked key parts and supplies. Meanwhile, soldiers drilled with the brimmed model M1917A1 doughboy helmets of WWI and old Springfield 1903 and Enfield rifles with suspect WWI-era ammunition.[14] When visualizing these soldiers in the Philippines, do not think of the “steel pot” helmets and the M1 carbines we normally associate with WWII. Those had not yet been developed or issued to these soldiers. Think of WWI doughboys.

In the fall of 1941, these Latter-day Saint soldiers landed in the Philippines and into this political and military muddle.

Notes

[1] Louis Morton, The United States Army in WWII / The War in the Pacific / The Fall of the Philippines, commemorative edition (Harrisburg, PA: National Historical Society, 1993), 2–3. In 1935 the Philippines became an autonomous commonwealth of the United States.

[2] US Department of State, “Milestones: 1937–1945, Japan, China, the United States and the Road to Pearl Harbor, 1937–41” (Washington, DC: Office of Historian), https://

[3] US Department of State, “Milestones: 1937–1945”; Columbia University, “Japan’s Quest for Power”; United States Army, A Brief History of the U.S. Army in World War II (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 1992), 3.1, http://

[4] US Department of State, “Road to Pearl Harbor”; Burton, Fortnight of Infamy, 20.

[5] Morton, Fall of the Philippines, 4.

[6] Morton, Fall of the Philippines, 52; United States Army, Brief History, 31–32.

[7] Morton, Fall of the Philippines, 61.

[8] Morton, Fall of the Philippines, 63–64; Burton, Fortnight of Infamy, 28–29.

[9] Morton, Fall of the Philippines, 64.

[10] Morton, Fall of the Philippines, 64; Shively, Profiles in Survival, 12–14; United States Army, Brief History, 31–33.

[11] United States Army, Brief History, 31–33; John D. Lukacs, Escape from Davao: The Forgotten Story of the Most Daring Prison Break of the Pacific War (New York City: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 10–11.

[12] See Morton, Fall of the Philippines, 33, 43.

[13] Lukacs, Escape from Davao, 32.

[14] Lukacs, 10–11; see also Morton, Fall of the Philippines, 43–45; Burton, Fortnight of Infamy, 39; Cave, Beyond Courage, 53.