What the World (and George and Ruby) Now Knew

Michael Harold Hyer, “What the World (and George and Ruby) Now Knew,” in Saints at War in the Philippines: Latter-day Saints in WWII Prison Camps (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 139‒44.

As I have loved you,

Love one another.

This new commandment:

Love one another.

—Luacine Clark Fox, “Love One Another”

The escape of ten POWs from Dapecol in April 1943 affected not just the treatment of the remaining POWs at Dapecol but also events back in the United States. On July 24, 1943, three of the escapees from Dapecol arrived by submarine in Australia, where they were debriefed by General MacArthur and his staff. Their stories were “so horrifying that the stenographers could take them for only twenty minutes at a time.”[1] They were flown to the United States and again debriefed. Much to their disappointment, they were quarantined and placed under a gag order with the risk of criminal prosecution and losing their commissions should they speak of their experiences to anyone but authorized personnel.[2] On September 9, 1943, President Roosevelt issued a secret order forbidding the disclosure of this information.[3] Their dangerous and miraculous escape had been motivated by a hope that, if the world knew what was happening, the care of POWs back in the Philippines would improve. Their country had now put them under a gag order.

One of the three was Major William Edwin Dyess, US Army Air Forces, from Albany, Texas. Dyess, a skilled pilot and leader of a P-40 Warhawks squadron in the Philippines, was captured at Bataan. Dyess survived the Bataan Death March and ended up at Dapecol via Cabanatuan. Some journalists managed to get the Dyess story, but they were ordered by the government not to publish it.[4]

The official reason for the gag order was a concern that the publication of these Japanese atrocities might endanger a planned delivery by a neutral ship, the Gripsholm, of medical supplies for Allied prisoners in the Pacific.[5] However, some suspect the government may have also had other motives. The government had been heavily criticized for failures in the Philippines. While the government was still pursuing its Europe-first policy, some in the press and many civilians, especially the New Mexico based Bataan Relief Organization, were clamoring for action in the Pacific. Those at senior levels of the government may have feared that the Dyess story would draw more attention to the government’s lack of action in the Pacific and more questioning of its Europe-first policy.[6]

While the press was far more compliant with government censors in WWII than now, even in those days, the press had its limits. The Chicago Tribune, which had the Dyess story, fully appreciated the journalistic significance of what it had and had been pressing the government for permission to publish.[7] Finally, on January 28, 1944, nine months after their escape and five months after the first telling of their story, the official army-navy statement on the atrocities committed by the Japanese military against American prisoners of war was released, and the press published the stories they had been holding for months.[8]

The stories rapidly spread, not only in the United States but also worldwide. The public, outraged and revolted, was riveted to the stories. George and Ruby Brown awakened to newspapers with headlines such as the one appearing on the front page of the El Paso Herald-Post that read “STORY OF BATAAN HORRORS REVEALED” or on the front page of New York Times: “5,200 AMERICANS, MANY MORE FILIPINOS DIE OF STARVATION, TORTURE AFTER BATAAN.” Some of the many subheads read “AMERICANS BURIED ALIVE” and “Men Worked to Death—All ‘Boiled’ in Sun—12,000 Kept Without Food 7 Days.”[9]

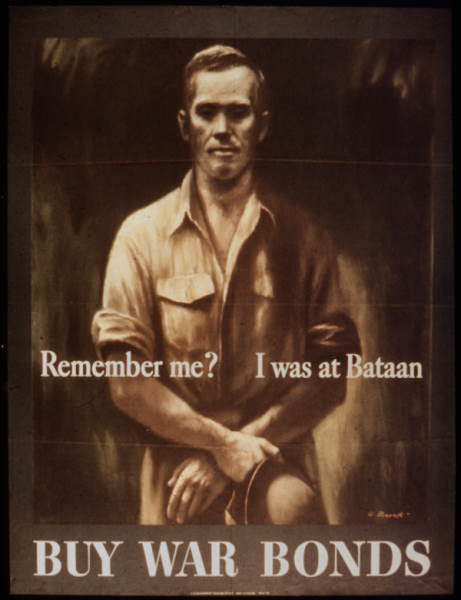

The tragedy of Bataan was used by the government to promote the sale of war bonds. Created by the Office for Emergency Management, Office of War Information, Domestic Operations Branch, Bureau of Special Services. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

The tragedy of Bataan was used by the government to promote the sale of war bonds. Created by the Office for Emergency Management, Office of War Information, Domestic Operations Branch, Bureau of Special Services. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

The stories then repeated the “factual and official” testimony of Dyess and the other escapees, spanning the fall of Bataan to the murder of a Dapecol POW. A week later, a Life magazine issue contained an exclusive feature entitled “Death Was a Part of Our Life,” authored by three of the escapees; the feature included photographs of all ten escapees and artists’ conceptions of events related by the authors. The Chicago Tribune and its one hundred associated papers published a total of twenty-four installments, one appearing each day for almost the next month. New Mexicans, through the Bataan Relief Organization, were now even more outraged, and they demanded to know why their government had withheld this information.[10]

This was likely the first reliable and detailed information the prisoners’ families would have received about the POWs in the Philippines since the surrender. We do not know the reaction of the families of these Latter-day Saint Pacific POWs to the release of the Dyess story or those of the other Davao escapees. In fact, these stories were notably absent from the stack of newspaper clippings that Ruby Brown had carefully clipped and saved. Nevertheless, after the publication of the atrocity stories, these families would have had a very graphic understanding of what may have happened or may yet happen to their captive son, brother, or husband.

George and Ruby Brown developed a deep and bitter hatred toward the Japanese that continued for many years.[11] An account of their efforts to forgive and shed that burden is included in President Spencer W. Kimball’s book The Miracle of Forgiveness.[12] Even if the hatred did not start with the revelations by Dyess and the other escapees, those stories would have intensified and given substance to those feelings.

The hate-engendering effect of the stories of Japanese atrocities was perhaps anticipated. The US government funded the war effort in part by selling war bonds to the public. The government’s release of the story appeared at the same time the government was launching a $14 billion war bond drive.[13] Though the government denied it at the time, it would strain credulity to accept that this was purely a coincidence.[14] In a staggering change of policy, the escapees were suddenly released from their gag order and, to support the sale of war bonds, pushed onto the national stage to make appearances and give interviews on the Japanese brutality.[15]

With the release of the atrocity stories and its “appeal to hatred,” war bond sales soared.[16] An El Paso newspaper quoted the chairman of the local war bond drive committee as saying, “The best answer to Japan’s fiendish treatment of American war prisoners is to buy War Bonds. . . . These official revelations by our Army and Navy make our blood boil. We on the home front can do something about it. We can buy War Bonds and thus give our fighting men the tools of war with which to avenge their comrades of Bataan.”[17] In appealing to vengeance and hatred to promote sales of war bonds, the government was building upon a prejudice already prevalent among many in the United States before the war.[18] After Pearl Harbor, the prejudice was particularly visible in the government-ordered incarceration of Japanese Americans in internment camps. Over 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, mostly from the West Coast, were forcibly interned and relocated to the western interior of the country simply because of their Japanese ancestry.

Leonard J. Arrington, a noted historian and Latter-day Saint, studied the internment camps, including one located in central Utah, and the resettlement of Japanese Americans. Many fellow citizens made inflammatory and derogatory remarks against Japanese Americans. Although he found that Japanese Americans were generally more welcome in the Latter-day Saint dominated Utah than in other states, there nonetheless was a strong sentiment against their presence, and they often faced blatant discrimination. Eventually, church authorities were compelled to publish a policy statement decrying this discrimination and pleading for the Saints to "banish these foolish prejudices from our natures."[19]

Over the course of the war, George and Ruby Brown developed a hatred of the Japanese. While the primary source of this hatred was the treatment by the Japanese Army of their son Bobby, George and Ruby were also simply absorbing a prejudice then prevalent among many in their country.

Notes

[1] Lukacs, Escape from Davao, 274.

[2] Lukacs, Escape from Davao, 278.

[3] Lukacs, Escape from Davao, 280.

[4] Lukacs, Escape from Davao, 309.

[5] Lukacs, Escape from Davao, 283; Daws, Prisoners of the Japanese, 274–75.

[6] Lukacs, Escape from Davao, 282.

[7] Lukacs, Escape from Davao, 309.

[8] Lukacs, Escape from Davao, 319.

[9] Lukacs, Escape from Davao, 319–23; “Story of Bataan Horrors Revealed: Japs Torture, Starve Murder Americans,” El Paso Herald-Post, January 28, 1944 (accessible in archives of Ancestry.com).

[10] Cave, Beyond Courage, 271–72.

[11] Clark and Kowallis, “Fate of the Davao Penal Colony,” 128.

[12] Kimball, Miracle of Forgiveness, 287–93.

[13] Lukacs, Escape from Davao, 324–25.

[14] The release was also timed to occur shortly before a planned offensive action in the Pacific, suggesting that the release may have been deliberately timed such that the planned action would provide immediate proof of the retaliatory action that the American public would surely demand. Lukacs, Escape from Davao, 329. The timing of the release was not lost on the members of the Bataan Relief Organization, who claimed the government suppressed the information because it feared the public’s demand for action in the Pacific and then only released it in time for the bond sale. Cave, Beyond Courage, 271.

[15] Lukacs, Escape from Davao, 326.

[16] Lukacs, Escape from Davao, 325.

[17] “Answer Japan by Buying War Bonds, El Pasoans Urged,” El Paso Herald-Post, January 28, 1944 (accessible in archives of Ancestry.com).

[18] Beginning with the Chinese exclusion act in the late nineteenth century and culminating with the 1924 immigration act, the United States government overtly discriminated against Asians.

[19] Leonard J. Arrington, "The Price of Prejudice" (Faculty Honor Lectures, paper 23, 1962), https://