Shinyo Maru

Michael Harold Hyer, “Shinyo Maru,” in Saints at War in the Philippines: Latter-day Saints in WWII Prison Camps (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 169‒80.

And should we die before our journey’s through,

Happy day! All is well!

We then are free from toil and sorrow, too;

With the just we shall dwell!

—William Clayton, “Come, Come, Ye Saints”

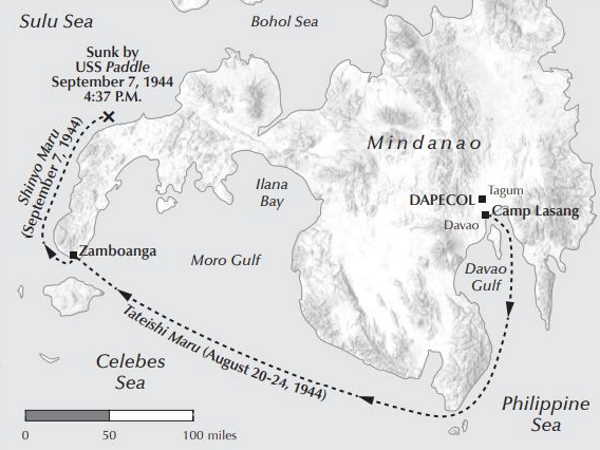

On August 20, 1944, the 650 POWs from Lasang—including Brown, Ernest Parry, and fifteen other Latter-day Saints from the branch in Davao—were roped together and marched shoeless a few miles to the Tibungco Pier, a small pier for a lumber mill near the Davao Gulf. There they were joined by one hundred prisoners from another camp.[1] Due to the increasing guerrilla activity in the area, they were heavily guarded. The POWs were first to be shipped to Cebu and then to Manila with Japan as the likely final destination.[2] Similar to the hell ship experience of other POWs, this group of prisoners would face the next three weeks living in the most miserable conditions.

At the Tibungco Pier, they were loaded aboard the old Japanese Army freighter Tateishi Maru, but it was marked only as “86”—a hell ship.[3] Many of the prisoners had been in a Japanese transport vessel before when they were taken to Davao, but this would be much worse. Suffocating heat, stagnant air, little food and water, the stench of sick and dying men, and darkness would now be their life. They were taken out to the side of the ship in small boats and then made to climb up a wide lattice rope to the deck. Four hundred were placed in one hold, and 350 in another. They climbed down ladders into the holds, where a Japanese soldier was waiting with his rifle and bayonet to crowd them tightly in the holds. They had to take turns standing and sitting, because there was not enough room for all to sit, let alone lie down, at the same time.

In the intense heat in the holds, the POWs were soon drenched in sweat. In such heat, the sweat on dirty skin caused skin rashes that later became open sores. Toilet facilities consisted of three five-gallon cans dropped down through the hatch and placed in the middle of the hold for use in full view. The food was inadequate, but food was not the problem; many of the POWs had managed to bring with them food from Red Cross packages they had previously received in camp. Rather, the problem was the lack of water and fresh air.[4]

Two POWs had escaped during an earlier voyage of a hell ship in this area. For that reason, coupled with the increasing risk of Allied attacks, the Japanese now kept the hatches covered and opened them for only brief periods.[5] A POW provided this description of the conditions:

Some got sick and many passed out for lack of oxygen. When the hatch covers were opened again, there wasn’t a sound; we were all too weak to say anything. . . . Possibly as many as one hundred fifty to two hundred men passed out in both holds and two men simply went berserk and had to be tied down. . . .

Many men were close to death by the time the hatch covers and tarp were removed. Revival was slow. Some thought they were dying and asked for last rites. . . . Many were desperate for water. . . . Some fought over who got the last drop from the canteen. All of us were terribly dehydrated. Those who had dysentery were in worse shape. Many were so weak they tried crawling to the latrine cans but just couldn’t make it; they just wallowed in their own filth. We urinated only once in a great while and with excruciating pain![6]

While the conditions were indescribably horrible and the Japanese crew was merciless, the POWs understood that their greatest danger came from Allied planes and submarines. To the US Navy, their unmarked freighter was just another tempting enemy target.[7]

The ship arrived in Zamboanga Harbor on the southwest tip of Mindanao on the Moro Gulf late in the afternoon on August 24, 1944. There the prisoners remained, cramped and sweltering in the dark, hot, and filthy hold for ten days.[8] Finally, on September 4, the hatch cover was opened, and the prisoners were ordered up the ladder. The POWs climbed up the ladder and noticed another ship, the Shinyo Maru, a few feet away. They were then ordered across a narrow plank precariously stretched across the gap between the ships. Once on the Shinyo Maru, they climbed down a long narrow ladder into the darkness of the bottom of the ship.

Ships of this size were generally divided horizontally into two compartments: an upper compartment about one-third of the way down from the deck and a lower compartment below. On the first ship, the Tateishi Maru, the POWs occupied the upper compartment. On the Shinyo Maru, however, the prisoners were put in the lower compartment at the very bottom of the ship. The long metal ladder went all the way from the deck down through the upper compartment, which was loaded with bales of cargo, to a dark abyss. It was a death trap.[9]

The Shinyo Maru was an antiquated freighter built in Scotland in 1884 and captured by the Japanese in Shanghai in 1941. At 312 feet long by 40.2 feet wide and only 2,600 tons in weight, the Shinyo Maru was smaller than the 3,801-gross-ton Tateishi Maru they were leaving. While it had been crowded on the Tateishi Maru, the prisoners were absolutely sardined in the holds of the Shinyo Maru. As done on other ships, boards were put across the single hatch just above the end of the ladder, cutting off any possible air circulation and adding to the prisoners’ terror and misery.

Map 3. Voyage of the Shinyo Maru. Map by Nat Case.

Map 3. Voyage of the Shinyo Maru. Map by Nat Case.

With information from the Magic intelligence operation, the United States already knew a lot about the Shinyo Maru, then at anchor at Zamboanga. On August 14, 1944, the US intelligence unit had first intercepted a Japanese naval message from Manila to Tokyo referring to the Japanese Navy’s urgent need for the Shinyo Maru.[10] A few days later on August 18, 1944, US intelligence intercepted another message ordering the Shinyo Maru to proceed from Zamboanga to Cebu and then on to Manila. Finally, a message intercepted on September 6 stated that the “C-076 convoy” was to depart Zamboanga for Cebu on September 7 at 2 a.m. The message indicated that the Shinyo Maru, transporting “750 troops for Manila via Cebu,” would be part of that convoy. Months later, British intelligence indicated that FRUPac, the US intelligence unit in Hawaii, may have erred in its interpretation of that message and that, correctly interpreted, the Japanese message stated that the Shinyo Maru was transporting 750 POWs, not 750 Japanese troops.[11]

Early in the morning of September 7, 1944, with the POWs crammed and suffocating in the hot, stale stench of its hold, the Shinyo Maru left for Cebu in a convoy.[12] It was not a coincidence that on that same day, a US submarine, the USS Paddle, was also in that part of the South China Sea looking for enemy ships to attack.[13]

The Paddle’s report of September 7, 1944, states that while the submarine was in her patrol area, about ten miles north of Sindangan Point, Mindanao, she sighted a small convoy consisting of “a medium tanker, two medium AKs [AK refers to a cargo ship], two small AKs, two torpedo boats or DE-type escorts [DE refers to a destroyer escort] and one small coastal tanker type craft [and] the tanker was leading the medium AKs and very close to the coast.” The submarine also observed two planes overhead.

USS Paddle (SS-263) underway 1944–45. Courtesy of United States Navy.

USS Paddle (SS-263) underway 1944–45. Courtesy of United States Navy.

To reduce the risk of being discovered, all periscope observations were very brief, and no effort was made to identify the actual names of the vessels spotted. The captain’s report then states: “Fired four bow tubes at AO [the tanker]. Immediately shifted set-up to leading AK [the freighter] and fired two tubes. . . . All torpedoes were heard to run towards targets. . . . Escort on starboard beam seen to have turned directly toward, so order was given to go deep. Periscope went under . . . before extent of damage to AK and AO could be seen. Loud, characteristic, breaking up noises were heard almost immediately however, and continued for some time after depth charging began. It is believed that of those two ships at least the AK sank and possibly both.”[14] The USS Paddle narrowly survived the forty-five Japanese depth charges and bombs aimed at it after the attack, and after a few hours it returned to its patrolling.

The “breaking up noises” that the USS Paddle crew heard came from the Shinyo Maru, which had been hit by a torpedo; trapped in its lower holds were 750 POWs, including the seventeen Latter-day Saints. For most of the POWs, death came quickly and violently from the explosion of the torpedoes. Others drowned as cargo bales and a bulwark from the upper compartment fell on them, trapping them at the bottom of the ship. Others were killed by Japanese guards firing machine guns into the hold and throwing down grenades. Some POWs, however, managed to escape through the hatch onto the deck or through the hole in the ship, only to face machine gun fire from Japanese guards as they emerged onto the deck or dived into the water.

The captain of the Eiyo Maru, the tanker also torpedoed, beached the ship near the shore to avoid sinking it. He then directed machine gun fire at the POWs who were swimming to shore. Lifeboats rescued the Japanese soldiers and crew from the Shinyo Maru, but the Japanese continued to shoot the escaping prisoners. Japanese patrol planes were also strafing POWs in the water.[15]

Despite the explosion, the sinking vessel, and the Japanese hand grenades and machine guns, eighty-three POWs managed to escape the sinking Shinyo Maru and reach the land, where they were gathered up by Filipino guerrillas and hidden from the Japanese in the jungle. In a remarkable rescue, all but two of them later escaped on the submarine USS Narwhal. One later died from injuries suffered in the attack on the ship, and another stayed in the Philippines to fight with the guerrilla forces. But none of the seventeen Latter-day Saint POWs was among those eighty-three survivors.[16]

For these Latter-day Saint POWs on the Shinyo Maru, the war was over, their respective missions on this earth complete. The seventeen Latter-day Saints who died in the sinking of the Shinyo Maru include the following:

- Private First Class William Murle Allred from Artesia, Arizona

- Private David Weston Balfour from Salt Lake City, Utah

- Private Jack W. Bradley from Moroni, Utah

- First Lieutenant George R. (Bobby) Brown from El Paso, Texas

- Private Mack K. Davis from Lehi, Utah

- Private First Class Woodrow L. Dunkley from Franklin, Idaho

- Second Lieutenant Richard E. Harris from Logan, Utah

- Private First Class Theodore Jackson Hippler from Bloomfield, New Mexico

- Private First Class Ferrin C. Holjeson from Smithfield, Utah

- Private Russell Seymore Jensen from Centerfield, Utah

- Private First Class Ronald M. Landon from Kimball, Idaho

- Private Harry O. Miller Jr. from Magrath, Alberta, Canada

- Staff Sergeant Ernest R. Parry from Salt Lake City, Utah

- Private First Class Lamar V. Polve from Kenilworth, Utah

- Private Jesse G. Smurthwaite from Baker, Oregon

- First Lieutenant Gerald Clifton Stillman from Salt Lake City, Utah

- Private Frederick D. Thomas from St. Johns, Idaho[17]

We know little of the particular circumstances of their deaths, although after the war, the Brown family learned from survivors more details about Brown’s death. Over the course of his imprisonment, Brown learned some Japanese, and while on the Shinyo Maru he had become acquainted with one of the Japanese officers. Brown was either on the deck at the time of the attack or was able to make his way to the deck shortly after the attack, because after the attack, he was seen on the deck trying to persuade this Japanese officer to order the guards to stop firing into the hold. The officer ignored him. Brown and a friend, Lieutenant Colonel George T. Colvard, a doctor from Deming, New Mexico, then leaped into the water to help some wounded prisoners who were clinging to debris. When a volley of shots rang out in their direction, they both dove under the water, but neither surfaced.[18]

Having died in the attack, these seventeen Latter-day Saint POWs on the Shinyo Maru left us no personal histories or memoirs. We know them and their final years largely through inferences and educated speculation from military records and histories of others. But what we do know suggests that they were ordinary Latter-day Saints placed in extraordinary times, who, although not perfect, nevertheless endured their trials faithfully and courageously to the end.

Missions

We know a little more about Bobby Brown, however. His mother, Ruby, and his older sister, Nelle Zundel, conscientious family historians, wrote several personal histories about him. Family members have preserved those histories along with various photos and other reminders of his life. Although highly informative, family histories are not necessarily objective. These were written as tributes to a beloved son and brother, not dispassionate accounts memorializing his shortcomings. In perusing those histories, we see clues to an aspect of Bobby as a young man that, while not necessarily hidden in the histories, is not accentuated.

Before departing for the Philippines, Bobby received a blessing from a Church patriarch that included a promise that he would be “preserved to complete a mission on this earth.” Family members regretted that Bobby was not able to serve that promised mission, and as people of faith in such blessings, I suppose they privately puzzled over why that blessing was not fulfilled.

When Bobby received that blessing, he was twenty-five years old. At that time, young men in the Church typically could serve missions as early as twenty or twenty-one years of age. A fair question would be why Bobby had not already served a mission. For example, although younger than Bobby, Orland Hamblin and Franklin East had each served missions before being drafted; East had even married shortly before leaving for the Philippines. Nels Hansen, although older than Bobby, had served two missions before being drafted—one at age nineteen, unusual for the time, and another at age twenty-one. Serving a mission for the Church is not required, and there are many acceptable reasons for not serving. Nevertheless, for those able to serve, missionary service is evidence of one’s commitment to the gospel of Jesus Christ and the Church. Bobby’s father, George, had served a mission in Mexico as a young man.

George sometimes made a personal list near the beginning of each year of things he needed to do or improve on, all with respect to the family. An item on one of those lists was to get “Bobby married or on a mission.” While there would have been many good reasons for Bobby not having served a mission or married, his parents were concerned about what he was doing with his life—not an unusual worry for parents of a single twenty-five-year-old living at home.

All the family members worked to support the family, which was financially struggling in the Great Depression. Bobby’s financial contributions to the family may have been especially important. He had a good job at the El Paso Electric Company, the local electrical utility, and had even provided some of the funds the family used to purchase their first home. A desire to continue this financial support may have been a reason for him not having yet served a mission. Even so, a perusal of old family photos reveals several with Bobby posing proudly by his new Ford, a car that incidentally was newer and nicer than his father’s. In El Paso, he had also been active and successful in community theater, musical productions, and a radio show.

Bobby Brown was most assuredly a dyed-in-the-wool, true-blue Latter-day Saint as a product of his solid upbringing and culture. He was hardworking and industrious, with leadership and musical skills and talents, and deeply loved his family and his church. He may also have been a young man with a taste for the more worldly aspects of life—cars, money, and the excitement of public theater and performance. Perhaps at that particular time in the battle for Bobby’s heart and mind, the lure of the world may have been winning over the call of his religion.

If so, Bobby changed. The war and his captivity purged him of any ambivalence about his commitment to his faith. While fragmentary, the evidence depicts a Bobby Brown who, with his leadership skills and musical talents, dedicated himself to bringing the blessing of gospel fellowship and hope to his fellow POWs. He became a leader, mainstay, and moving force in the branch in Dapecol. Nonetheless, a challenge for his family is reconciling the fate with his patriarchal blessing.

Notes

[1] Sneddon, Zero Ward, 73–76; Bolitho, “A Japanese POW Story,” part 6 (December 5, 2009), 1; Michno, Hellships, 225–26.

[2] Clark and Kowallis, “Fate of the Davao Penal Colony,” 123.

[3] The ship was the 3,801-gross-ton Japanese Army transport No. 86 named the Tateishi Maru. West-Point.Org., “Hell Ship Information and Photographs,” http://

[4] Bolitho, “A Japanese POW Story,” part 6, 1–3.

[5] Michno, Hellships, 173–74. The two POWs had escaped from the Yashu Maru, which coincidentally had been transporting the POWs who had remained at Dapecol.

[6] Bolitho, “A Japanese POW Story,” part 6, 2.

[7] Lukacs, Escape from Davao, 111, 343.

[8] Sneddon, Zero Ward, 88–89; Clark and Kowallis, “Fate of the Davao Penal Colony,” 124.

[9] Sneddon, Zero Ward, 90–94.

[10] Gladwin, “American POWs on Japanese Ships.”

[11] On December 31, 1944, a note was added in pencil to FRUPac’s translation of that September 6 message stating, “FRUEF [the British Fleet Radio Unit Eastern Fleet] (31 Dec ’44) gets 750 Ps/

[12] Sneddon, Zero Ward, 94–95; Clark and Kowallis, “Fate of the Davao Penal Colony,” 124; Gladwin, “American POWs on Japanese Ships;” West-Point.Org, “Hell Ship Information and Photographs.”

[13] Michno, Hellships, 295.

[14] USS Paddle (SS263), Report of Fifth War Patrol, B.H Nowell, Lt.-Cdr. USN, September 7, 1944, 7–10. (The report can be viewed at the “Submarine War Reports” page on pages 186–89 of the microfilm of the USS Paddle reports, accessible at the website for the Historical Naval Ships Association, at http://

[15] Lukacs, Escape from Davao, 344; Sneddon, Zero Ward, 99–107; Clark and Kowallis, “Fate of the Davao Penal Colony,” 124–26.

[16] Sneddon, Zero Ward, 99–107, Lukacs, Escape from Davao, 343–44; Clark and Kowallis, “Fate of the Davao Penal Colony,” 124–27.

[17] This list is simply the Latter-day Saint POWs at Davao whose names are also on the roster of the Shinyo Maru. “Roster of Allied Prisoners of War believed aboard Shinyo Maru when torpedoed and sunk September 7, 1944,” http://

[18] Brown and Zundel, “George Robin Brown . . . His Story,” 21; Nelle B. Zundel, “A Problem Solved” (unpublished manuscript, April 2, 1992). These accounts are similar, although with more detail, to the account in the Clark and Kowallis article, which was based on a nephew’s recollection of the story as told him by Ruby. Clark and Kowallis, “Fate of the Davao Penal Colony,” 124–26; see also Kimball, Miracle of Forgiveness, 288. In the family history account, Ruby and her daughter Nelle Zundel wrote that the story of Brown’s death came from one of the survivors, but the name of the survivor was not mentioned. The family history account includes a specific reference to “a Doctor friend of Bob’s, from Deming, N.M.” Although the account does not name the doctor, he was likely Dr. George Colvard. The roster of those who died in the sinking of the Shinyo Maru includes Lt. Col. George T. Colvard, a surgeon in the 200th. Shinyo Maru Roster, http://