Epilogue

Those Who Did Not Come Home

Michael Harold Hyer, “Epilogue: Those Who Did Not Come Home,” in Saints at War in the Philippines: Latter-day Saints in WWII Prison Camps (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 231‒44.

What is this thing that men call death,

This quiet passing in the night?

’Tis not the end, but genesis

Of better worlds and greater light.

O God, touch Thou my aching heart,

And calm my troubled, haunting fears.

Let hope and faith, transcendent, pure,

Give strength and peace beyond my tears.

There is no death, but only change,

With recompense for victory won;

The gift of Him who loved all men,

The Son of God, the Holy One.

—President Gordon B. Hinckley[1]

For the families of those Latter-day Saint POWs on the Shinyo Maru, there would be no War Department telegram advising that their loved one was alive and returning home, no hearing his voice in a long-distance phone call, and no warm welcome home by family and friends who had never lost hope. Instead, they, like so many others, received a series of terse War Department letters advising them of that which they had hoped and prayed never to be told.

These Latter-day Saint POWs had survived two and a half years of brutal imprisonment that included beatings, torture, sicknesses, and starvation at the hands of a brutal enemy—all while maintaining a faith and hope in God—only to be killed by an American torpedo. For many families, this was an incomprehensible tragedy. That none of the Latter-day Saint POWs were among the survivors of the Shinyo Maru was a crushing blow to their families’ faith in God and their religion. Before receiving official confirmation of the POWs’ deaths, one father wrote, “I believe that I have as much faith in my religion as any Latter-day Saint, but I will never be able to understand this. Certainly some of those boys were entitled to the blessings that are promised to those that obey the laws and keep the commandments of God. . . . I hope and pray that some of those boys are alive, otherwise I will have a hard time reconciling the fact they were all killed with what my faith has taught me to believe.”[2]

How could these families find solace for such a heartbreaking loss? How could they reconcile their faith in God with the unfathomable injustice of the death of their sons?

Like other grieving families who lost loved ones in WWII, these Latter-day Saint families would find comfort and support from a nation that, while celebrating victory and the safe return of others, openly and genuinely acknowledged its gratitude for the sacrifices made. Sincere condolences were offered for their loss, as witnessed by the many memorials, monuments, ceremonies, and posthumous awards of medals and citations.[3]

The grieving families found comfort and support among caring family members, friends in their community and church, and sometimes from surviving POWs. It was not unusual for families to be visited by surviving POWs who had known their lost loved one, often to make good on an earlier promise made to him. The grieving families also found peace in their religious faith, and for the families of these lost Latter-day Saint POWs, their faith included particularly reassuring teachings about death.

A Most Comforting Doctrine

As part of their faith, these Latter-day Saint families believed that families can be together throughout the eternities—that their son, brother, or husband was not lost to them forever. This belief is not merely a vague hope for the distant eternities, but their faith informs them, in considerable detail, of the state of their departed loved one now as well as in the eternities.[4]

From section 138 of the Doctrine and Covenants, which is President Joseph F. Smith’s account of his 1918 vision of the spirit world, the faithful families of these POWs knew that there is a continuation of sociality among the spirits and that their loved one would be among friends and relatives who have died. In a passage that would certainly resonate with the families of these deceased young men, President Smith said that in his vision, “I beheld that the faithful elders of this dispensation, when they depart from mortal life, continue their labors in the preaching of the gospel of repentance and redemption, through the sacrifice of the Only Begotten Son of God, among those who are in darkness and under the bondage of sin in the great world of the spirits of the dead.”[5]

The parents of these deceased Latter-day Saint POWs may have never adjusted completely to their tragic loss, and nothing can fill the empty place in the hearts and homes of these families or compensate for the dashing of all their hopes and dreams for their lost family member.[6] Nevertheless, for the faithful Latter-day Saint families, their understanding of death must have been an especially comforting source of solace and hope.

We now consider the families of two of these deceased POWs, Staff Sergeant Ernest R. Parry and First Lieutenant George R. Brown.

Ernest R. Parry

Staff Sergeant Ernest R. Parry was known to his family by his middle name, Reynolds. He was the only son of his widowed mother and was brother to two sisters. He was the caring companion who befriended Private Franklin East at a difficult time on the voyage to the Philippines, earning East’s eternal gratitude and respect, and was a mainstay of the branch at Davao. His mother, Georgiana R. Parry, responded to the news of the death of her only son by writing a poem entitled “My Service Flag”:

My service flag, so brilliant,

With its silver, red, and blue,

Tells of the service of my son,

So young, so strong and true.He went away all smiling

In his uniform so trim,

With never a sign of sorrow

But knowing war is grim.He wrote such cheerful letters!

Wishing he could hear from home,

Telling of islands far away,

Of the ocean, blue, with its foam.“O Father,” I prayed, “have mercy

On all boys of tender age,

Who answer the call of country

To write across history’s page.”The story of war—its sorrows,

Its shocking atrocities, too.

How many died of starvation!

How many the enemy slew!Today there came a letter.

The gist of its message is old.

As I looked up for solace, I saw

My blue star had turned to gold.[7]

Reynolds has not been forgotten but continues to inspire his family. Although he was lost at sea, his family placed a grave marker for him in the Evergreen Cemetery in Springville, Utah. A family tradition that still continues is to place flowers on the grave marker on Memorial Day.[8] Suzanne Julian, the granddaughter of one of Parry’s sisters, was honored to speak at a Devotional at Brigham Young University in 2014. Among those she offered as a source of inspiration for a righteous life was her great-uncle Staff Sergeant Ernest Reynolds Parry.[9]

George Robin “Bobby” Brown

Back in El Paso, the news of the death of First Lieutenant George Robin (Bobby) Brown came to his family as an emotional rollercoaster of tentative, incomplete, and in the end unfounded pieces of hope. The Browns received a letter from the War Department dated October 27, 1944:

The War Department was recently notified of the destruction at sea of a Japanese freighter that was transporting American Prisoners of War from the Philippine Islands.

A number of survivors were later returned to the military control of our forces. There were also a large number who did not survive or who were recaptured by the Japanese and about whose present status no positive information is available. It is with deep regret that I must inform you that your son, First Lieutenant George R. Brown, 0890150, was in this latter group. Because of the War Department’s lack of definite information concerning First Lieutenant Brown, no change in his Prisoner of War classification is being made at this time.

Please be assured that as soon as additional information becomes available you will be immediately notified.[10]

Ruby then began a series of anxious, but in the end fruitless, correspondence with her Congressman and the army, seeking additional information and confirmation of various rumors then circulating about the fate of those on Shinyo Maru.[11]

On February 14, 1945, the US War Department received from the Japanese an official list of the POWs aboard the Shinyo Maru, and Bobby was on that list. The War Department notified the Browns of Bobby’s death in a letter dated February 19, 1945.[12] Similar letters were sent to families of all 688 who died in the sinking of the Shinyo Maru.[13]

However, since Japanese reports were not always considered accurate, there was still some hope that Bobby had not actually been on the Shinyo Maru. The family desperately contacted a number of men who had been POWs in the Philippines, desperately looking for some evidence to support that hope, but without success.[14] It slowly became clear and the facts unavoidable. The Japanese list had been correct.[15] Bobby had been on the Shinyo Maru and was dead. George acknowledged as much on February 27 by starting correspondence with the government regarding the steps needed to “get Bobby’s affairs with the government settled,” as he wanted to “make it a closed book as soon as possible.”[16]

For months during this period, Ruby was ill and bedridden with what her doctor had diagnosed as a heart ailment.[17] More likely she was simply overwhelmed, first with the fear and anxiety over the fate of her son and then with the emotional shock of his death. As to her faith, she wrote, “You know very well that there have been thousands of prayers offered for Bobby, both by his family and friends, and I feel that he was worthy of the protection of the Priesthood, but it must be that his work was finished. . . . At least that is the most comforting thought to me and we had to have comfort from somewhere.”[18]

A Final Matter for Eternity

While Bobby Brown’s mortal life ended on September 7, 1944, there remained a final matter of mortality to be attended to, one final gift to Bobby of eternal significance: the temple endowment. Ruby finally gathered herself up from her afflictions, and she and George went to take care of this final earthly ordinance for Bobby. On November 13, 1945—with his father, George, as proxy and his mother, Ruby, and sister Nelle in attendance—Bobby received the endowment ordinance in the Mesa Arizona Temple. It was a solemn but joyful day for the family.[19]

Medals and Ceremonies

After the war, George and Ruby, along with Bobby’s older sister, Nelle, attended a special ceremony held in the office of Major General John L. Homer, the commander of Fort Bliss in El Paso, where Bobby was awarded a Bronze Star, a Purple Heart, and some other medals posthumously.[20] Friends and family attended, including Gregorio Villasenor, who had been Bobby’s driver and who had been with him when they surrendered in Bataan. In presenting the medals, General Homer spoke to them of Bobby’s heroism and offered thoughts of comfort.

Ruby Brown receiving a medal posthumously for Lt. George Robin (Bobby) Brown. Courtesy of the Brown family collection.

Ruby Brown receiving a medal posthumously for Lt. George Robin (Bobby) Brown. Courtesy of the Brown family collection.

Sadly, Homer had to conduct many such ceremonies and knew the medals and his words were little consolation for the grieving families. In that context, he said something else to the Brown family members that Ruby and Nelle were careful to record later in a family history. Nelle wrote,

When he saw the attitude of the family, General Homer made a very profound statement, “On many occasions that have taken place in this office, I have had the privilege of honoring so many in ceremonies such as these, and there will be many more.” Then he added, as he held both mother and father’s hands, and looked into their faces, “Would that I could wrap into a package the feelings of acceptance of God’s will, and the lack of bitterness that is in your hearts, that I might give it to those who are not so blessed with whatever it is that you have, that makes you so understanding. No greater gift, short of their loved one, could I give them.”[21]

What General Homer was seeing but could not specifically identify in the Brown family was their religious faith—their belief that Bobby was not lost to them forever but that they would yet be reunited after death. As to the bitterness, perhaps their positive faith effectively hid it, but there was in the corner of the hearts of Ruby and George a gnawing bitterness and hatred toward the Japanese.

On December 7, 1946, five years after Pearl Harbor, George and Ruby, accompanied by Bobby’s siblings Jane and Paul, attended a gathering held for surviving friends and families of those in the 200th Regiment who had not survived the war. It was held in Santa Fe, where the regiment had its origin. The venue was the old Seth Hall, a famous building with beautiful territorial-style architecture. To sad-faced parents, widows, and children of the men of Bataan—Anglo-Saxon, Native American, and Hispanic—was presented, along with other medals, the Bataan Medal, the highest honor from the State of New Mexico.

Visitors

During imprisonment, POWs spoke to each other of their homes and families and often promised, if they managed to make it home, to contact a fellow prisoner’s family. They memorized fellow POWs’ phone numbers and addresses. More than one hundred returning soldiers who knew Bobby visited the Brown family at their home in El Paso.[22] Many just walked up to the house unannounced, saying, “I was with your son in Mindanao.” They would ask to see the fishpond and fountain in the backyard that Bobby must have spoken about, and they mentioned other personal recollections.[23]

Among those visitors was Major Robert G. Davey. He reenlisted and in 1946 was stationed briefly at Fort Bliss in El Paso. He had recently married, and he and his wife, Dorothy, lived in a small trailer parked in a vacant lot adjoining the Brown residence. He was a frequent guest in the Brown home; the Browns learned much from him about Bobby’s experience as a POW and the branch they had formed at Davao.[24]

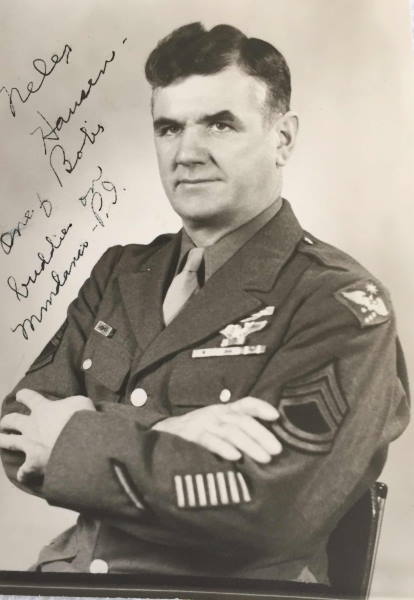

Another visitor was Sergeant Peter Nelsen (Nels) Hansen, the high priest who served with Brown in the Davao Branch.[25] One of the first things Hansen did on arriving in the United States was telephone the Brown family. In that call, Hansen offered to be a proxy and to perform the temple ordinances for Bobby. That wasn’t necessary, because by that time those ordinances had been done. However, to a devout Saint like Ruby, that simple offer conveyed a wealth of reassuring information about the nature of the Latter-day Saints her son had been with in captivity.[26] Among the pictures Ruby kept and treasured was an autographed army photo of Hansen.

Army photo of Master Sergeant Nels Hansen, which was autographed by Hansen and given to Ruby Brown. Courtesy of the Brown family collection.

Army photo of Master Sergeant Nels Hansen, which was autographed by Hansen and given to Ruby Brown. Courtesy of the Brown family collection.

Arthur M. Baclawski survived the Bataan Death March, Camp O’Donnell, and Cabanatuan camps in the Philippines, a hell ship voyage to Japan, and the cold and hardship of a POW work camp in Japan—one of the surviving New Mexico members of the 200th. He kept a diary of those he knew in the war who had died, and after the war he visited the families of many of them. Bobby Brown was on the list, and a couple of years after the war, Baclawski went to visit the Browns in El Paso.[27] While visiting with George and Ruby, he also met Bobby’s younger sister Jane. There followed a courtship, romance, and marriage.

I knew him as my Uncle Art. While I assume he suffered some lingering effects of his captivity, I never noticed them, and whatever physical or emotional demons he may have carried home from his POW experience did not get the better of him. He went on to have a successful career as a landscape architect for the federal government. Uncle Art was not a member of the Church and did not join after the war or after his marriage. Even so, he encouraged Jane’s and his children’s activity in the Church, and his children were raised as active members of the Church. Finally, on November 28, 1991, he was baptized a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He died just over a week later on December 7, 1991.

An Extraordinary Experience

George and Ruby Brown understood and accepted the Church teachings on death and found solace in them. Nevertheless, they felt deeply the loss of their son Bobby and had yet to be emotionally reconciled to his death. Then, nearly five years after Bobby’s death, they were unexpectedly blessed with their own personal, private “revelation” on death.

On July 31, 1949, a Sunday evening, George suffered a severe heart attack and was taken to the hospital. His prospects were not good. Ruby stayed in the hospital with him through Thursday.

Thursday evening, feeling lonely and worried, Ruby went home to get some sleep. But sleep did not come and she tried reading to get drowsy. Ruby later wrote that she had felt the unmistakable presence of Bobby in the house. His presence had entered through the front door and gone into the kitchen and other parts of the house, although not into her room. The strangeness of the experience left her unable to breathe. Nevertheless, Ruby described it as “the sweetest feeling in my soul that I have ever experienced.” After a few minutes, it was gone.

Nothing was seen and no voices were heard, but Ruby later wrote that she knew then that Bobby’s presence was real and knew it as certainly as she knew that she was “now writing this on my typewriter.” She related that her first reaction had been panic, believing it was a sign that Bobby had come from the dead to take George from among the living, but that feeling was soon replaced by a “sweet, calm spirit,” and she finally fell asleep.

The next morning, Ruby went to see George in the hospital and found him somewhat improved. George asked Ruby to close the door, as he wanted to tell her something. Speaking with difficulty because of his emotions, George explained that ever since the heart attack, he had had the feeling that he would die and had been desperately worried about the fate of the family. While he was in this state of worrying about his and the family’s fate and drifting in and out of sleep and consciousness, he had had the following experience, which he related to Ruby:

It seemed that [George] was in front of a large building, and a lot of people were there, and among them, his mother, and Dan Skousen, his brother-in-law, and they were talking and visiting, when a door opened, and Bobby came out, apparently by appointment. Very casually, he came over and greeted his father [George] and told him they were discussing and deciding just what they were going to do about him.

It also seemed that there were some young people there, who were trying to get to speak to Bobby, but he told his father to tell them he had to go on an errand but would get back as soon as he could. . . . He soon returned and smilingly explained that he just had to go on, and then turning, he added that they had not yet reached a decision about [George].

Bobby looked well and happy . . . and was well dressed. He had whispered to his father and told him to get ready for whatever was done with him, and to tell Nelle to get ready for she too had work to do.

Bobby smiled, and walked quietly away, and then [George] heard the nurse tell [him] that he was better, and she was going to feed him some breakfast.[28]

Ruby then shared her experience of the prior evening. They wept together, “knowing that our prayers had been heard in the high heavens, and that Bobby was there . . . looking after us, and that at times he is not so very far away.”[29]

George did not die but survived that heart attack and, according to Ruby, did “his level best . . . to make up for anything he might have failed to do, . . . trusting in the Lord for strength and courage” until his death eleven years later on August 20, 1960.[30] Ruby continued serving in the Church, doing genealogy and temple work, and, as a faithful family chronicler, writing family histories and stories.

In the misery of a World War II POW camp in the Philippines, Bobby had often found peace and comfort in singing the hymns of Zion, hymns he had first learned from his mother in Colonia Chuichupa high in Mexico’s Sierra Madre. Late in Ruby’s life, when the cumulative toll of infirmities and the effects of old age had left her troubled in mind and body, she too would find solace to her soul in that same source—the hymns of Zion. Ruby died in peace on May 3, 1981, at the age of ninety.

Notes

[1] Gordon B. Hinckley, “The Empty Tomb Bore Testimony,” Ensign, May 1988. In 2007 the poem was put to music by Janice Kapp Perry and titled “What Is This Thing Man Calls Death?,” Ensign, February 2010.

[2] Clark and Kowallis, “Fate of the Davao Penal Colony,” 128.

[3] There are memorial markers for these POWs at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in Manila, Philippines. Brown’s name, along with the other members of the New Mexico’s 200th and 515th Coast Artillery, are engraved on twelve granite columns at Bataan Memorial Park in Albuquerque, New Mexico. In 1964, El Paso dedicated the El Paso County War Memorial. Inscribed on the wings of the monument are 657 names of those who sacrificed their lives in WWII and the Korean War, and Brown’s name is among them.

[4] In this spirit world, the spirits of the righteous are received into a state of happiness, which is called paradise, and the spirits of those who die without knowledge of the truth and those who are disobedient in mortality are received into a state called spirit prison. Spirits from paradise are able to teach the gospel of Jesus Christ to those in spirit prison. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Basic Doctrine, https://

[5] Doctrine and Covenants 138:57.

[6] Clark and Kowallis, “Fate of the Davao Penal Colony,” 128. (Clark and Kowallis were able to interview some of the siblings of the deceased POWs who “reported that their parents probably never adjusted completely to the tragedy”).

[7] Julian, “Led by the Spirit” (quoting poem, which is used with permission). At that time families with a member serving in the war displayed a blue star in their window. Those who had lost a family member displayed a gold star.

[8] Email from Suzanne Julian to author, April 20, 2017.

[9] Julian, “Led by the Spirit.”

[10] J. A. Ulio, Major General, The Adjutant General, War Department, to Mr. George A. Brown, October 27, 1944, NARA Records.

[11] Mrs. George A. Brown to Honorable R. E. Thomason, November 12, 1944, NARA Records; Honorable R.E. Thomason to J.A. Ulio, Major General, The Adjutant General, November 14, 1944, NARA Records (forwarding the Brown letter of November 12, 1944); Mr. and Mrs. George A. Brown to Major General J. A. Ulio, Adjutant General, November 17, 1944, NARA Records.

[12] J. A. Ulio, Major General, The Advocate General, The Adjutant General’s Office, War Department, to Mr. George A. Brown, February 19, 1945, NARA Records.

[13] Clark and Kowallis, “Fate of the Davao Penal Colony,” 127.

[14] For example, Sergeant Calvin Graef from Carlbad, New Mexico, a survivor from Bobby’s unit, first told the Brown family that he had seen Bobby at Dapecol in October 1944, but later conceded that he had been mistaken about the date.

[15] Clark and Kowallis, “Fate of the Davao Penal Colony,” 127–28.

[16] George A. Brown to Honorable R. E. Thomasson, February 27, 1945, NARA Records; Honorable R. E. Thomason to Major General J. A. Ulio, The Adjutant General, War Department, March 2, 1945, NARA Records (forwarding Brown’s February 27, 1945 letter).

[17] Brown and Zundel, “George Robin Brown . . . His Story,” 17; Hyer, “Classy Grandmas,” 9.

[18] Clark and Kowallis, “Fate of the Davao Penal Colony,” 128.

[19] For members of the Church, the temple endowment ordinance prepares and qualifies a person to receive the fullness of God’s blessings in heaven after death. For those who die without having received this ordinance, such as Bobby Brown, another person, a proxy, may receive this ordinance in the temple on their behalf. The realization of the blessings of the ordinance, however, depends on its acceptance and the faithfulness of the deceased. To provide this ordinance, through proxy, for a deceased family member is for Church members a sacred experience and offering. The temple endowment ordinances were also performed for Brown’s close friend John Keeler, with Ivan Zundel as proxy, and for Ruby’s cousin Acord Spilsbury with Ivan’s father, Jacob E. Zundel, as proxy. Ivan was the husband of Bobby’s older sister Nelle. Brown and Zundel, “George Robin Brown . . . His Story,” 17. The Brown family histories refer to the ordinances as being performed on November 15, 1945. However, the Church records indicate those ordinances were performed on November 13, 1945.

[20] Zundel, “Brown Family History,” 5. Brown was posthumously awarded the following: Bronze Star Medal with Letter “V” Device, Purple Heart, Distinguished Unit Emblem with 2 Oak Clusters, American Defense Service Medal with Foreign Service Clasp, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with two Bronze Service Stars, World War II Victory Medal, Philippine Defense Ribbon with one Bronze Service Star, Philippine Liberation Ribbon with one Bronze Service Star, and Philippine Independence Ribbon. Official Statement of Military Service and Death of George R. Brown, 0 890 150 by Kenneth G. Wickham, Major General, USA, the Adjutant General, NARA Records. Brown was also posthumously awarded the “Bataan Medal” by the State of New Mexico.

[21] Brown and Zundel, “George Robin Brown . . . His Story,” 22–23.

[22] Zundel, “Brown Family History,” 5.

[23] Brown and Zundel, “George Robin Brown . . . His Story,” 20.

[24] Brown and Zundel, “George Robin Brown . . . His Story,” 17–18.

[25] Brown and Zundel, “George Robin Brown . . . His Story,” 17–18.

[26] Brown and Zundel, “George Robin Brown . . . His Story,” 17–18.

[27] Based on emails and conversations with Paul and Robert Baclawski, two of Arthur Baclawski’s sons.

[28] Ruby S. Brown, “This Is a Very Sacred Story,” December 16, 1953, El Paso, Texas, vol. 4, item H.4, Ruby S. Brown Collection, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, 1–2. See also Brent L. Top, “What Is This Thing That Men Call Death? Latter-day Saint Teachings About the Spirit World” (BYU Campus Education Week address, August 18, 2010), BYU Speeches, 12–13 (overview of Church teachings on living persons receiving help and comfort from a deceased family member in the spirit world).

[29] Ruby S. Brown, “This Is a Very Sacred Story,” 1–2.

[30] Brown, “This Is a Very Sacred Story,” 2.