Struggling to Create a Firm Foundation (1920-29)

Riley M. Moffat, Fred E. Woods, and Brent R. Anderson, "Struggling to Create a Firm Foundation (1920-29)," in Saints of Tonga (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 93–134.

Mark Vernon Coombs Arrives

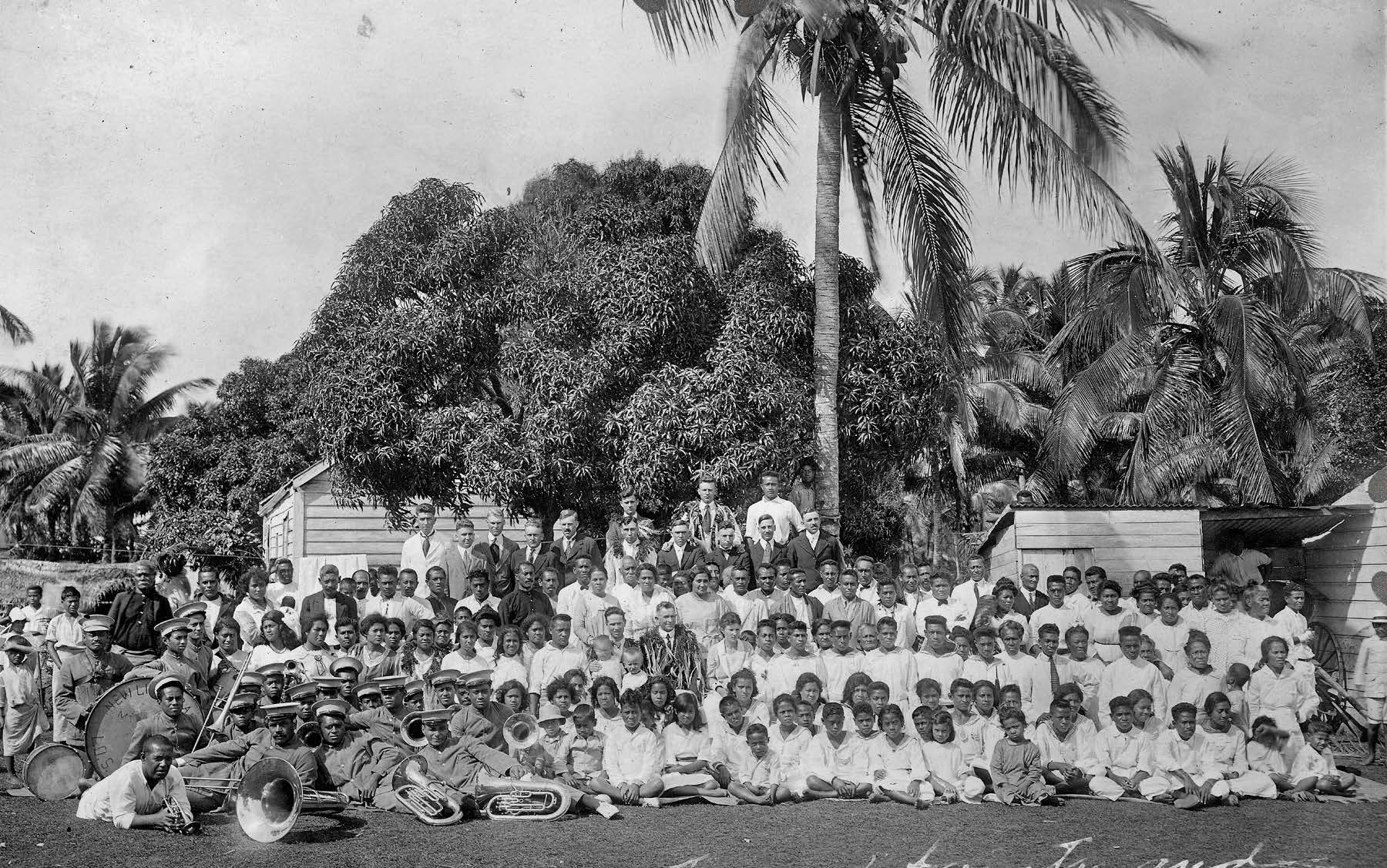

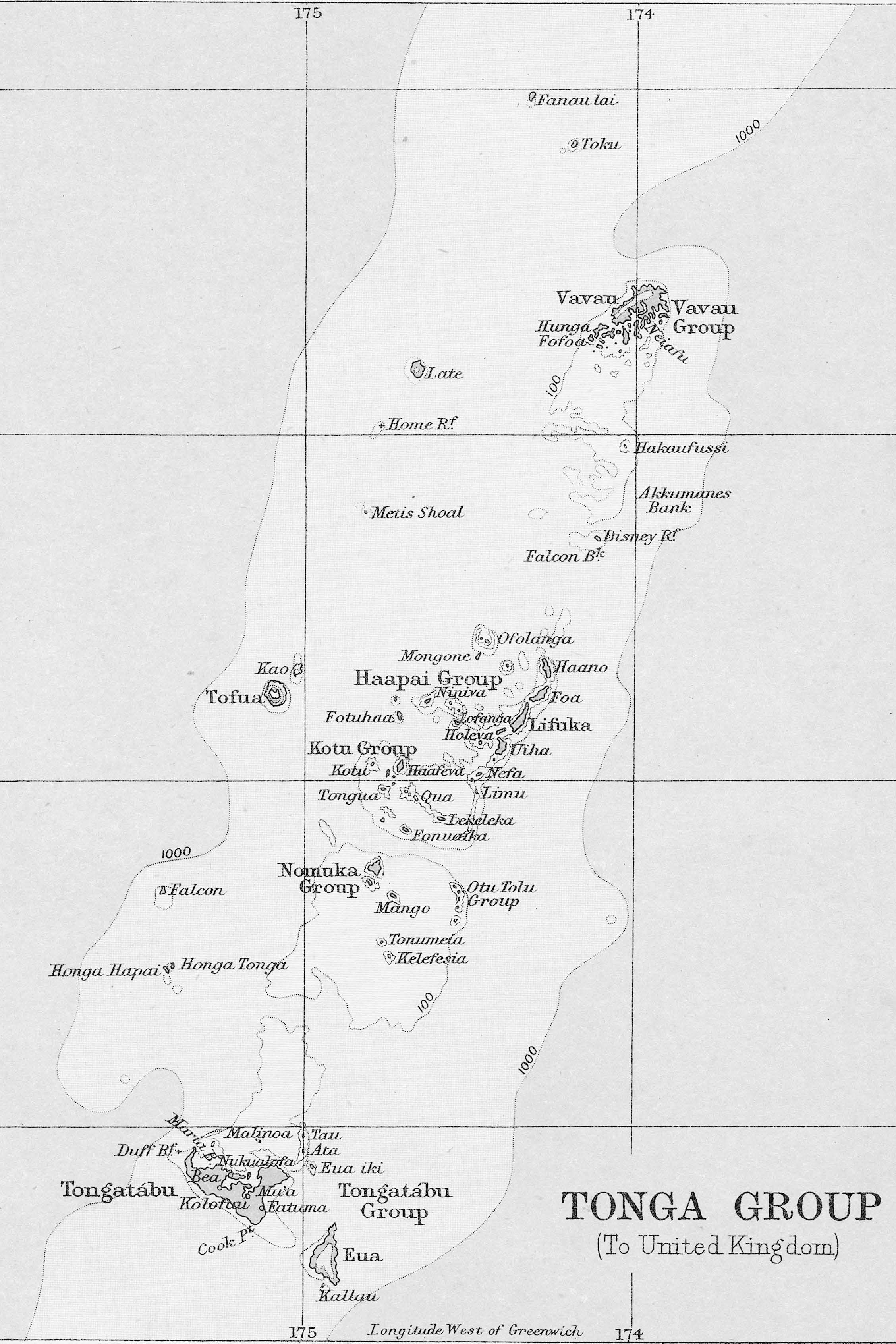

In addition to President Edward J. Wood, Samoan Mission president, and Willard L. Smith, first president of the Tongan Mission, Mark Vernon Coombs was another young man called from the Alberta Stake to serve a mission to Samoa. Originally, he was assigned to teach at the Church’s Mapusaga school on Tutuila in 1911. When he got there, he started a band that was a very successful missionary tool as they performed around the Samoan Islands. Mission president John A. Nelson requested he take the band on a tour of the Tongan Conference in November 1913. In Vava‘u they were hosted by Iki and Levaitai Tupou and even performed for King George II, who was in Vava‘u to convince the high chief Pita Afu of Ha‘alaufuli, who had become a Latter-day Saint, to return to the Free Church. Then the band went on to Tongatapu and performed at all the branches there before returning to Mapusaga.

In 1920 Coombs and his wife, LaVera, whom he had met when she and her family were serving as missionaries in Samoa, received their call to preside over the Tongan Mission. They arrived in Nuku‘alofa on August 10, 1920, and were met by acting president Elder Elmer Fullmer, who had been appointed by President Willard Smith before he returned home for health reasons. In emergency situations like this, it could take months to receive a call, get all the permissions and visas, and then find the ships that could get a new missionary from North America to Tonga. President Coombs did not know much Tongan, but because he already knew Samoan, Coombs said he learned the language in three weeks. In Nuku‘alofa they established a fine new mission home called Matavaimo‘ui on one and one-half acres in Kolomotu‘a. The property also contained the foundation for a proper timber chapel and Tongan fale (thatched hut) dorms for students attending the little school, held in an oval tin-roof chapel.

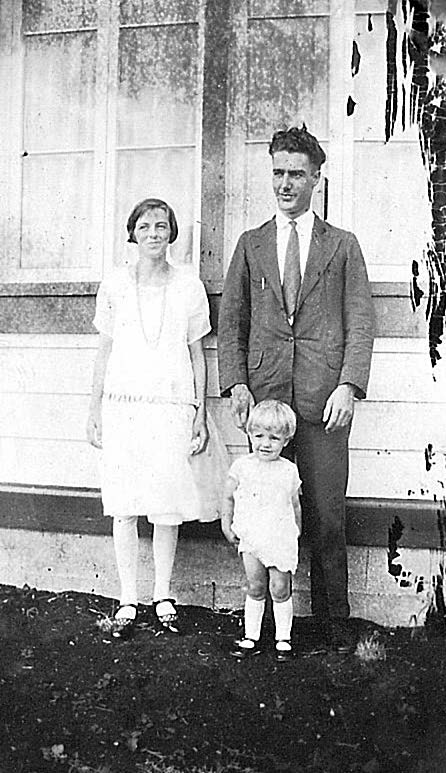

President Mark Vernon and Sister LaVera Coombs with their children and some elders. Clarence Henderson collection courtesy of

President Mark Vernon and Sister LaVera Coombs with their children and some elders. Clarence Henderson collection courtesy of

Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Immediately a problem emerged. Except for Elder Emile C. Dunn, all the other missionaries had already been in the mission field for four years because of the refusal of Great Britain to issue visas to Latter-day Saint missionaries. These elders should have returned home before he arrived. He also found that all applications to buy land for chapels and schools had been refused by the government since they assumed that with no new missionaries the Church would wither and die. Within thirteen months, all the experienced elders who knew the language had departed, leaving Coombs and a few new elders to do the best they could. He also learned that the Tongan government was following the lead of Great Britain and its other colonies in seeking to restrict Latter-day Saint missionary activities. His Canadian passport offered little protection, and he was advised by the British consul in Tonga to “lay low.”

President Coombs, who became known in Tonga as “Misi Vina,” considered the Church’s schools the highest priority. He wrote in a letter to the Deseret News: “The main feature of our work is school teaching, every Elder whether from office, farm, or shop teaches school when they come to TONGA.”[1] He also saw that just having primary schools was simply not enough: “Ever since our arrival in Tonga it was very clear to me that if our schools were to measure up to our expectations it would be imperative that we have a piece of land on which to build suitable school buildings and ground in which to grow food for the children. The very life of our missionary endeavor depended upon the success of our schools.”[2]

President Coombs described the school at Matavaimo‘ui in a December 1920 letter to the First Presidency:

In common with other island Missions, a great deal of our work here is in the school-room. Each Elder teaches a school in the village wherein he is stationed. This necessitates the establishment of a head school somewhere, that the brighter and older students can attend. The students at the h[e]ad school have to grow their own food for they are unable to buy, and their families live on distant islands making it impossible for the student to get food from them. For some time previous President W. L. Smith had endeavored to lease a piece of land that the students might sustain themselves but was not able to do so.[3]

He was concerned about the shrinking attendance in the Church’s schools. When the Church would open a school, students would flock to it, and many were baptized along with some of their parents, but when the students and their parents were asked to help support the school with the purchase of supplies, they quit coming because the school was no longer free. Many baptized students stopped coming not only to school but also to church. From the very beginning of missionary work in Tonga, it was apparent that some were more interested in getting free schooling than in committing to the teachings of the gospel.

As President Coombs surveyed the Tongan Mission, he saw some practical needs that he wanted to make a priority. He asked Church leaders in Salt Lake City for missionaries who could do carpentry because he wanted to build five chapels and there were no missionaries or members who could do that. He also wanted a missionary with musical skills to continue the band at the Maamafo‘ou school in Neiafu after Elder S. Ibey May left. It was the only band on the island, and it was asked to play at all the ship arrivals and departures at Neiafu and made concert tours around Vava‘u, which gave the Church tremendous visibility.[4] President Coombs said, “The band was a big factor in our school there.”[5] Coombs also needed missionaries who could teach school because the schools were by far the greatest missionary tool the mission had. Salt Lake replied that missionaries with those types of skills were hard to find and that most elders would prefer to proselytize rather than perform these kinds of practical labor.[6] Because of the shortage of missionaries with practical skills, the Saints at Pangai had built a chapel out of their own pockets for $1,300.

During the administration of President Mark Vernon Coombs, the official policy of the Tongan government reflected not only the examples of Great Britain and other Commonwealth countries like New Zealand but also the de facto relationship of the Free Church of Tonga and the Wesleyan Methodist Church with the government. The queen was trying to get the two churches reunited, but they refused. They were often at odds and had enough problems just trying to get along with each other without having to deal with churches like The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, who were trying to convert their members. They tried to make life as difficult as they possibly could under the constitutional promise of freedom of religion, yet many saw truth in what the Latter-day Saints taught, coupled with their good works.

Visit of Elder David O. McKay

An important wireless arrived on May 29, 1921, advising that Elder David O. McKay of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles was planning to arrive on the Tofua in a week’s time and that President Coombs was to arrange for meetings to be held with the Tongan Saints at the various islands the Tofua would visit. The Tofua arrived on May 8 but was quarantined because of a reported measles outbreak in a previous port, so no one could come ashore. A note was passed to President Coombs inviting him to come aboard and take passage with Elder McKay and his traveling companion, President Hugh J. Cannon of the Liberty Stake in Salt Lake City. They could then go to Samoa together and return to Tonga in a month with the hope that the quarantine would be over.

Passengers quarantined on Makaha‘a Island with Elder David O. McKay. Clarence Henderson collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Passengers quarantined on Makaha‘a Island with Elder David O. McKay. Clarence Henderson collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

President Coombs instructed Elder Emile Dunn to arrange conferences for their return and then bid his family goodbye. Coombs learned from passengers on board that there really was no epidemic of measles in the previous ports of Suva or Auckland, so something was suspicious. He “felt that the quarantine was imposed at the instigation of the Tonga Free Church and the Wesleyan denomination just to prevent the visit to Tonga of Elder McKay.”[7] The ship was also quarantined during its stops in Ha‘apai and Vava‘u, but not when they reached Apia.

They arrived back at Nuku‘alofa on June 11 to find the Tofua was again quarantined. President Coombs prevailed upon Elder McKay to undergo the two-week quarantine so he could visit with the Saints in Tonga. Elder McKay instructed President Cannon to proceed on to New Zealand. Thirty-one passengers hoping to land at Nuku‘alofa were then dumped on tiny Makaha‘a Island, only one hundred by two hundred yards and situated two miles northeast from Nuku‘alofa, to undergo their quarantine. Along with Elder McKay and President Coombs were four new elders coming to Tonga, as well as some passengers from Japan, the Solomon Islands, and two Protestant ministers. Elder McKay’s daily diary described a boring two weeks in which he became very homesick as he wandered around the tiny island. Regarding living in close quarters with the two Wesleyan ministers, McKay wrote, “You just can not mix oil and water.”[8]

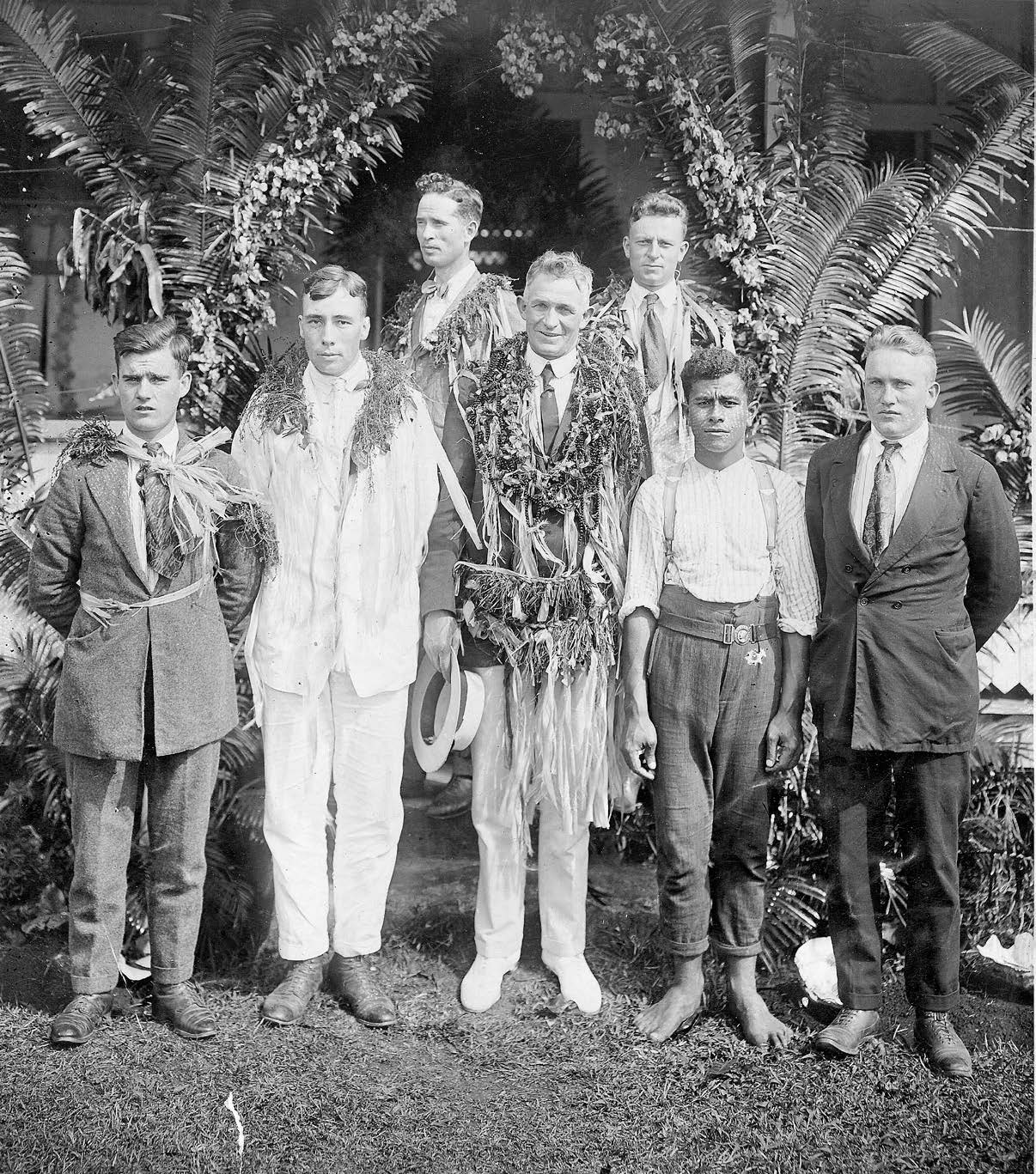

“Just out of quarantine.” Top left to right: President M. Vernon Coombs and Elder Lewis Parkin. Bottom left to right: Elders Walter Phillips, George Robinson, David O. McKay, Pauliasi Fua Matua, and Clarence Henderson. Clarence Henderson collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

“Just out of quarantine.” Top left to right: President M. Vernon Coombs and Elder Lewis Parkin. Bottom left to right: Elders Walter Phillips, George Robinson, David O. McKay, Pauliasi Fua Matua, and Clarence Henderson. Clarence Henderson collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

The quarantine period gave President Coombs time to update Elder McKay on the conditions of the mission. Because of these unusual circumstances, President Coombs decided to call one grand mission conference on the island of Tongatapu. While Elder McKay and President Coombs were quarantined on Makaha‘a, Elder Dunn and Sister Coombs made excellent preparations for Elder McKay’s visit. Many Saints had come down from the other islands to meet Elder McKay. However, at the instigation of the Protestants, the Church’s Maamafo‘ou College band from Vava‘u was not allowed to march to greet Elder McKay when they finally came ashore in Nuku‘alofa. The mission home was gorgeously decorated with flowers and arches, and a large bowery was built to hold the crowd that had assembled. Elder McKay said he could pick out those who held the priesthood by the look in their eyes.[9] He was then welcomed with a kava ceremony.

The next day at the conference, Elder S. Ibey May attempted to interpret Elder McKay’s talks, but was overcome with emotion, so Lui Wolfgramm stepped in. Elder McKay said, “Some day the Tongan Government will appreciate the work done and efforts of the Missionaries of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.”[10] Elder McKay then issued a warning: “No government nor man can raise its hand against the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints without bringing punishment, disintegration and separation upon itself. I say this in the authority of my apostleship. No weapon raised against Zion shall prosper. If this government takes an unfavorable attitude toward you brethren, I tremble for its future; for pestilence and scourges shall be poured out upon them until the leaders repent.”[11]

Makaha‘a detainee house.

Makaha‘a detainee house.

He was obviously referring to the official reception he had received upon arriving in Tonga. He then shook hands with everyone in attendance and remarked: “These are the greatest people to shake hands with that I have ever seen, . . . true descendants of Israel.”[12] At the close of the first session of the conference, Elder J. K. Rallison of the Ha‘apai Conference baptized thirteen souls, including the daughter of a noble. In addition, Maile of Nukunuku and Metui of Fahefa were ordained elders. Only Siosifa Naeata of Ha‘alaufuli had previously been ordained an elder.[13] Coombs wrote, “The ministers of the other churches are quite concerned over the matter. They are so exercised that only recently did the head of the Tongan Free Church make a special visit to the queen and advised her to command certain nobles to either discontinue their connections with the Mormons on pain of losing their claim to the nobility and thus their heritage.”[14]

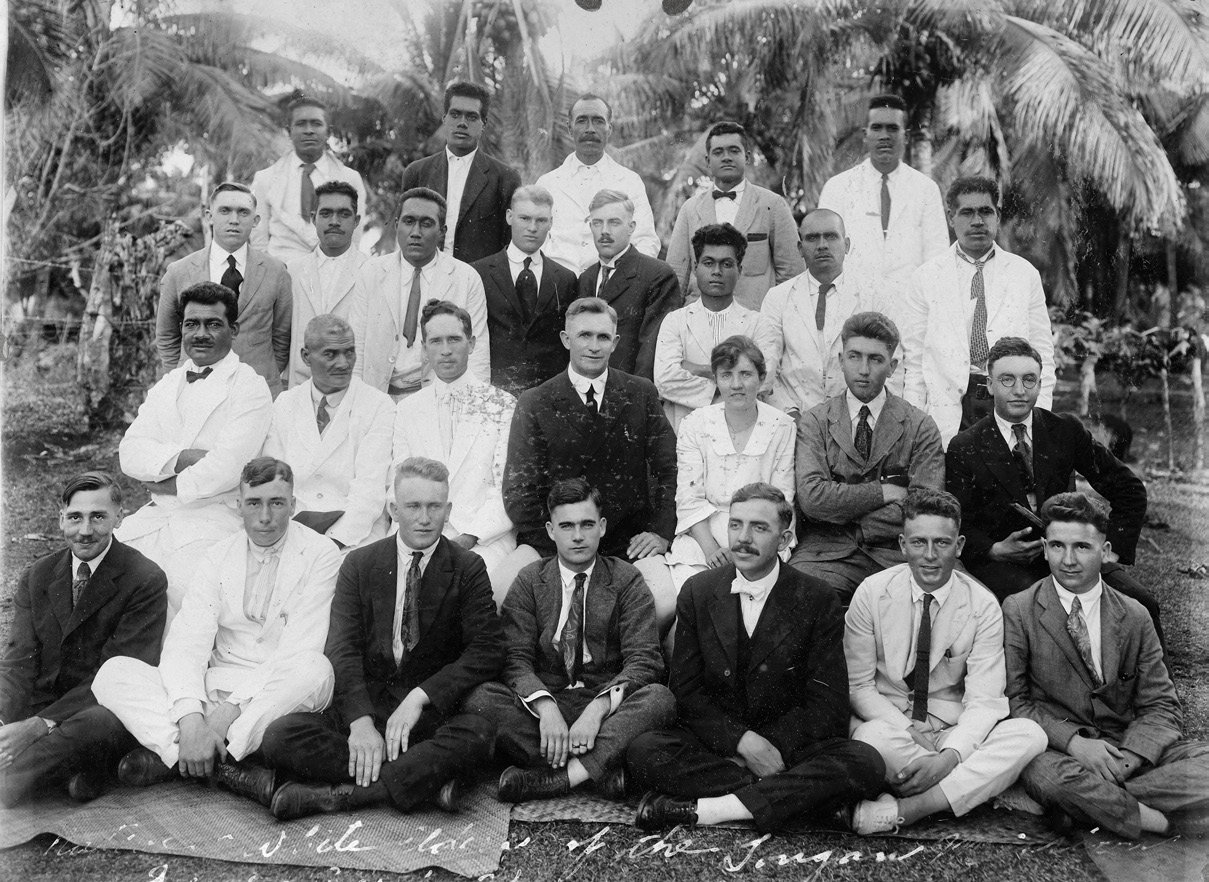

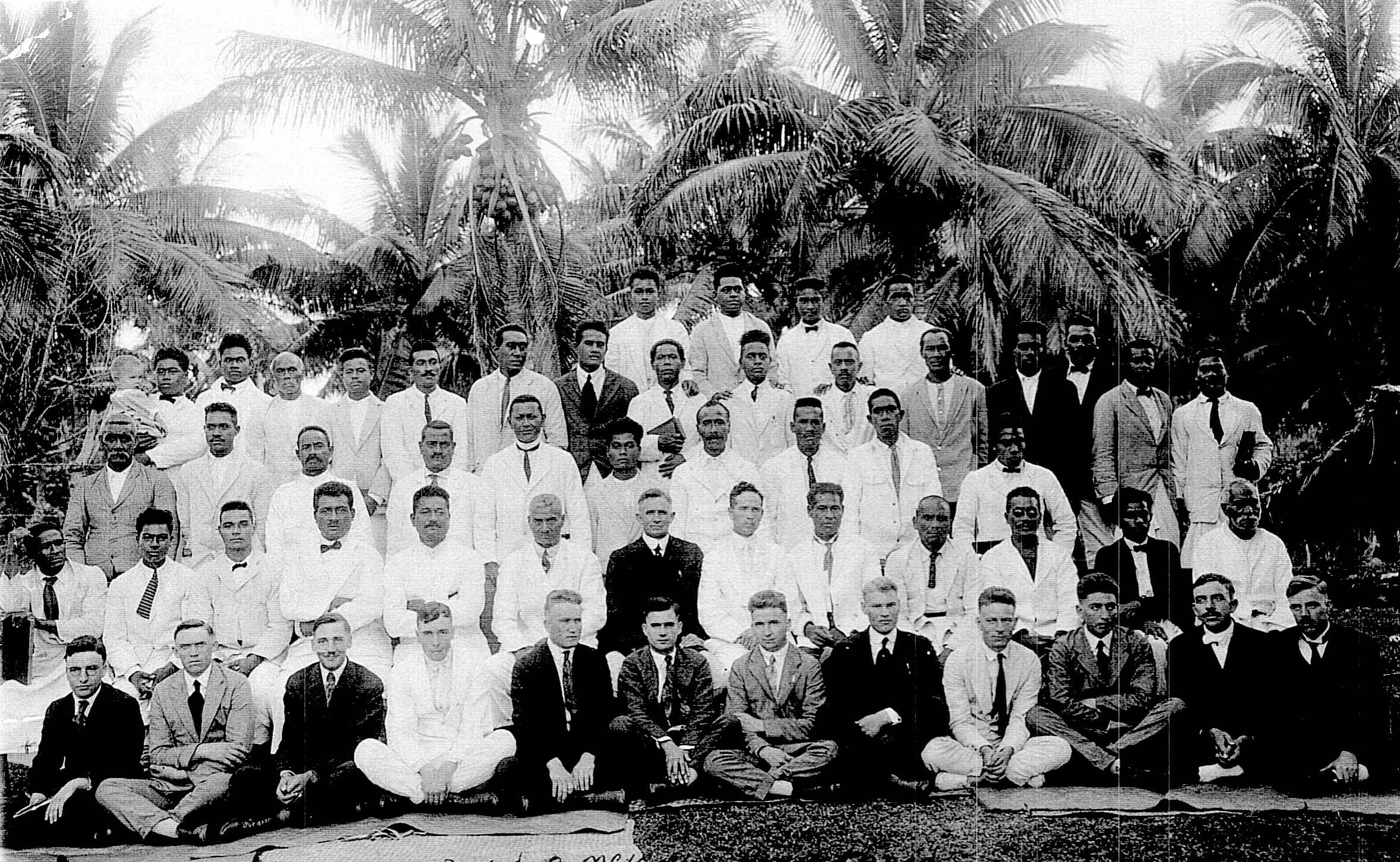

Elder David O. McKay and missionaries. Clarence Henderson collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Elder David O. McKay and missionaries. Clarence Henderson collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Mr. George Scott, the prime minister’s secretary, arranged an interview with Prince Tungī, the prime minister and husband of Queen Salote. Prince Tungī candidly told him, “I have nothing against your efforts here, but the Wesleyan and the Tongan Free Church feel that you are taking away too many of their members.”[15] In terms of the Church school situation, Elder McKay told President Coombs to continue his efforts to find a suitable piece of land for a school.[16] Elder McKay, along with the elders, unveiled the granite tombstone the family of Elder Charles John Langston had sent to put over his grave in the cemetery across from Matavaimo‘ui. Elder Langston had died helping others during the Spanish influenza pandemic in 1918. Elder McKay also took time to inspect pieces of land President Coombs was considering for a school site in Houma and Ha‘ateiho, but none seemed adequate.

A remarkable spiritual manifestation of the gift of tongues was recorded during Elder McKay’s visit by a faithful member from Houma named Sili Fehi. He related that when Elder McKay spoke at Nuku‘alofa he understood everything that Elder McKay said without waiting for the interpretation, although he did not know any English.[17]

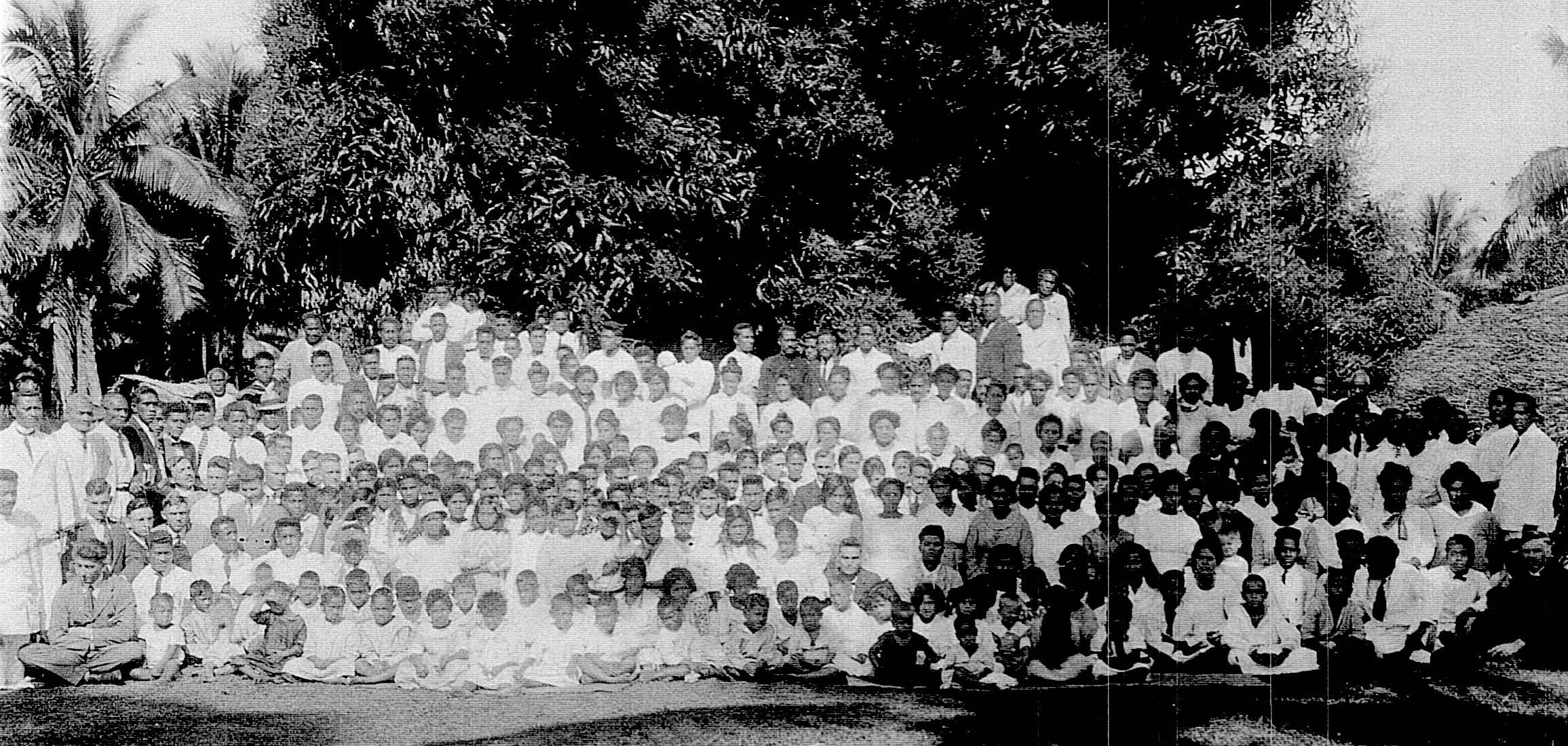

Elder David O. McKay with missionaries and men holding the priesthood. Clermont Oborn collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Elder David O. McKay with missionaries and men holding the priesthood. Clermont Oborn collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

A large group of Saints accompanied Elder McKay aboard the Tararawa, which Elder McKay renamed the “Ta-Ra-Ra-Ra-Boom-De-Ay.” On June 30 it sailed north to Ha‘apai. Elder McKay said he wanted to experience what the elders had to go through as they traveled from island to island. The captain was drunk, and they all thought they would die in the rough sea and the many unmarked reefs, but Elder McKay hid the captain’s whiskey bottle so he could eventually sober up.[18]

The group had only a few hours with the Saints in Ha‘apai before setting off for Vava‘u after fixing a broken rudder. The poor captain veered off course to the west overnight, and it took an extra day to get to Neiafu.

In Vava‘u they only had a few hours because the Tofua was in port and would leave that evening, but there was time to have a sacrament meeting at the Ha‘alaufuli chapel and ordain Charles F. W. Wolfgramm, the branch president, an elder. “It was at this meeting that Elder McKay blessed the land and the people for the spreading of the Gospel.”[19] In a letter to Junius F. Wells, President Coombs reflected back on the early days in Vava‘u. He said that of the three or four people baptized in Vava‘u in the 1890s, Jacob Olsen was the one who had remained very faithful to the principles of the gospel.[20] He had been baptized just before the elders were withdrawn in 1897, and he welcomed them back when they returned in 1907.

Elder David O. McKay and Relief Society sisters. Clermont Oborn collection. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Elder David O. McKay and Relief Society sisters. Clermont Oborn collection. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Events after Elder McKay’s Visit

Later in 1921 President Coombs had applied for a lease of land in Pangai, Ha‘apai, to build an elders’ home. The government secretary xreplied by saying: “I have been requested by cabinet to inform you that the Government has under its consideration the question of preventing Mormons from coming to Tonga, and, pending the settlement of that question they do not consider it desirable to grant any more leases to the Mormon Church.” In reply to this letter President Coombs wrote: “In line with this action you will no doubt be interested to know that of a recent inspection on the various schools, public and secular, ours were pronounced by the Government Inspector to be the best excepting only the Government college at Nukualofa.”[21] Yet it took another four years to finally get a lease to build the elders’ home in Pangai.

Another noteworthy event occurred in 1921. Elder Sterling Ibey May had worked diligently at translating the Book of Mormon into Tongan. By the time he left to go home in October 1921, Elder May had translated half of the book. Unfortunately, his manuscript was put on a shelf in the mission home and forgotten.

The following spring, May 16, 1922, a boat came in from Ha‘apai bearing the news that Elder Clermont Oborn had died at Pangai five days earlier. He had contracted typhoid fever and had been cared for by Sione Kongaika and his wife, Mele. By law he had to be buried the next day. The Saints arranged for a choice gravesite next to the ocean that belonged to one of Tonga’s highest chiefs. Elder Oborn had been teaching sixty students at the Pangai school, but by July only nine were attending. Heartbreaking news continued as the spirit of apostasy crept into some of the branches soon after the spiritual high Elder McKay’s visit had brought to Tonga. Even more bleak news arrived informing them that one of the Tongan students at the Maori Agricultural College, Manase Mailangi, had died on June 14 and was buried at the college.

The Passport Act

Two weeks later, President Coombs learned that as Elder McKay had prophetically warned, “the Tongan government passed an ordinance forbidding any more MORMONS to enter the Kingdom of Tonga with but four dissenting votes.”[22] As early as 1919 Prime Minister Tu‘ivakano had held discussions with the cabinet that it was “not advisable to allow any more members of the Mormon Church to come to Tonga”[23] and asked for British Consul Islay McOwan’s help. The government’s feeling was that the two largest denominations were all that were needed. McOwan said that he needed evidence to proceed. Tu‘ivakano admitted he had none, just rumors from England that elders were exporting young girls to Utah.[24] In the cabinet’s debate, a copy of which Coombs did not get until 1923, the main issue was polygamy and the fact that it was supposedly being taught in Tonga.[25]

The notice about restricting the entry of Latter-day Saints appeared in the Tonga Government Gazette, no. 21, to go into effect Tuesday, July 18, 1922. Page 113 reads, “An Act Relating to Passports. Be it enacted by the Queen and Legislative Assembly of Tonga in the Legislature of the Kingdom of Tonga as follows: This act may be cited for all purposes as the Passport Act of 1922.” Article 7 states, “Every person who is a member or adherent of the sect styled the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints commonly called Mormons is hereby forbidden to land in the Kingdom.”[26] Then articles 8 and 9 lay out the penalties that could be imposed. President Coombs learned that Tu‘ivakano was the chief proponent. He had “asked for British permission to pass a law banning Latter-day Saint missionaries as undesirable immigrants.” Tu‘ivakano reasoned, “They can hardly be looked on as Christians and therefore religious liberty would not apply to them.”[27]

Manase Kaho, one of the four dissenting votes, told Coombs that “Tugi [Tungī], Prime Minister and husband of the Queen, accused us in the legislature of teaching the natives to be disobedient to the Queen, Her Consort, and to the nobles and that we taught and practiced polygamy.”[28] In the queen’s closing remarks of the legislative session, she commended the legislature “for enacting prohibitive laws against those elements which tended to cause contention and disorder in the Kingdom.”[29]

So, until further notice, President Coombs had only twelve missionaries to help him run the mission. Elder Lawrence and Sister Mary Ann Leavitt, who were assigned to replace Elder Bryan and Sister Elsie Winward as teachers at the Ha‘alaufuli school, arrived just before the prohibition started. Nevertheless, the mission moved forward. One ray of light appeared when Coombs was invited to join the exclusive Nuku‘alofa Club by former American consul Mr. J. Clements; there he was able to get better acquainted with leading expatriates and nobles. In addition, the elders went ahead with construction of the chapel at Matavaimo‘ui in Nuku‘alofa with Elder Reuben Wiberg in charge. President Grant wrote to encourage President Coombs by saying, “There is no doubt in my mind that the ministers of the various denominations were instigators of the recent legislation against our people. . . . It is only a question of time, Brother Coombs, when right will triumph and we will have liberty in Great Britain and all her colonies.”[30]

The public’s reaction to this ban forbidding Latter-day Saints to enter Tonga was to generally snub the missionaries, who in their minds were now undesirable foreigners. President Coombs wrote to President Grant, “We have been stoned out of houses, in Ha‘apai the natives will absolutely not allow us to ride in their boats. In Vava‘u the natives politely request us to leave their houses, and the natives everywhere have informed us they are strictly forbidden to converse with a Mormon missionary.”[31] The elders were also refused passage on boats owned by the Protestants and their members. Elder Clarence Henderson, president of the Ha‘apai Conference, found it impossible to make the rounds of his conference because the Ha‘apai people would not allow a Latter-day Saint on one of their boats. So Elder Henderson borrowed a rowboat and risked his life on treacherous seas to visit the Saints.[32]

Some of the people President Coombs did business with confided that the Wesleyans were at the bottom of the affair. Many members of other faiths thought that the Latter-day Saints would give up their proselytizing efforts and were surprised to see the construction of the Matavaimo‘ui chapel proceed. An unintended benefit was that the law created interest in the Church. Po malanga (evening street meetings) in Nuku‘alofa were well attended.

At the request of Mr. Quincy Roberts, American consul at Apia, President Coombs sent a detailed letter describing the Church’s relations with the Tongan government.[33] Overall, the Passport Act put a great deal of social pressure on members of the Church. Coombs doubted if very many members could withstand the pressure. He did all he could to get the offending parts of the act repealed, but for the rest of 1922 and 1923 such a prospect did not look promising for the Church. What Coombs didn’t know was that there were significant efforts behind the scenes in Washington, London, and elsewhere to reverse what was viewed as blatant religious discrimination, but it would take time.[34]

One improvement was the change in attitude of Tonga’s British Consul Islay McOwan. McOwan even invited Coombs to join a golf club that Coombs learned to enjoy, and he invited President and Sister Coombs to high-level social functions, much to the discomfort of some other attendees. McOwan’s actions sent notice that he was on President Coombs’s side in the Passport Act debate. This political intrigue was aided by a deepening rift and intense feelings that escalated into some violence between members of the Free Church of Tonga, supported by the people’s representatives in the legislature, and the Wesleyan Church, supported by the queen and the nobles. Coombs recorded that people were being injured and even killed in fights over the queen’s attempt to reunite the Free Church and the Wesleyans (which had split around 1885 in the days of Shirley Baker and Tupou I). This infighting weakened the positions of both churches and took attention away from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. President Coombs wrote, “The common people are losing confidence in their own spiritual advisors and are opening their homes and hearts to us. Our difficulty is in distinguishing between the truly repentant and believer AND the fellow who wants to join us because he is simply disgusted with his missionary.”[35]

The Passport Act caused a few members with weak testimonies to fall away. They were not able to withstand the ridicule they received. This and the infighting of the Wesleyan and Free Church congregations stirred up the people into a religious fervor. Mission records reveal that at the end of 1922 there were 1,008 members, with about 200 being “inactive.”[36] However, as time passed, many disaffected members returned to their duties and the missionaries began to find more success with those interested in discovering the truth. The outcomes of the challenges the Church faced from 1922 to 1924 included the falling away of weak members (often those interested only in the high-quality education their children could receive in the Church’s schools) and, conversely, the strengthening of testimonies to withstand ridicule faced during this time of difficulty.

Ermel Morton summed up his take on the Passport Act crisis:

The 1922 Passport Act caused two basic reactions in that it successfully and completely stopped the flow of Mormon missionaries into the Tongan Islands. This, of course, was its underlying purpose. But along with preventing the entrance of Mormon missionaries into Tonga it also turned much criticism and ridicule against those missionaries already in Tonga and against the Tongan members of the Church. Many of the newly converted members of the Church could not bear this added burden and subsequently fell into inactivity and in some instances even became numbered among those who ridiculed the active members. Concurrent with the passage of this act and its subsequent two-year imposition there existed a period of religious ferment between the Tongan Free Church and the Wesleyan Church. This ferment, coupled with curiosity generated by the imposition of the 1922 Passport Act caused a wave of interest in the Church of Jesus Christ which brought many new members into the Church.[37]

The work moved forward. A new thirty-by-fifty-foot chapel with a fifteen-foot-high arched ceiling in Kolomotu‘a at Matavaimo‘ui was dedicated on March 9, 1923.[38] The chapel included a belfry and bell. There were no benches as the members preferred to sit on the floor. It included a bronze sign made in New Zealand declaring it as Koe Jiaji o Jisu Kalaisi moe Kau Maonioni Aho ki Mui Ni (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints). People were intrigued to learn that what they had always known as the Mormon Church was actually the Church of Jesus Christ.

Matavaimo‘ui chapel. Clarence Henderson collection.

Matavaimo‘ui chapel. Clarence Henderson collection.

Then on July 11 Coombs received word that Elder Althen Rasmussen had also died of typhoid fever in Ha‘apai. He was laid to rest beside Elder Oborn in the beachside cemetery just north of Pangai.

Because of the issues existing between the Church and the Tongan government that prevented missionaries from entering Tonga, President Coombs received a letter from President Grant on January 23, 1924, suggesting the mission be closed. During this time of discouragement, President Coombs considered the suggestion to find a “gathering place” for the Saints in Tonga away from persecution. He was aware of gathering places the Church had established in Hawai‘i at La‘ie and at Sauniatu in Samoa.

Matavaimo‘ui chapel. Clarence Henderson collection.

Matavaimo‘ui chapel. Clarence Henderson collection.

On April 13 President Coombs invited eight couples to go to the Hawaiian Temple, but no one seemed to have enough money.[39] In the midst of all this, on June 28, President Grant asked President Coombs to stay on as mission president for three more years and promised one hundred dollars a month for his support.

About two and a half months earlier, on April 15, President Coombs had asked Siosaia Mataele, a member of the legislature, to speak for the Church in presenting a petition to rescind the offending parts of the Passport Act in the upcoming session.[40] This request came just as the queen’s attempt to reunify the Wesleyan and Free Church was falling apart. President Coombs counseled Church members to stay clear of the dispute. Almost all the Europeans around Nuku‘alofa were willing to sign President Coombs’s petition. The petition was signed by 122 Europeans (almost all the Europeans on the island) and 424 Tongans. It also had the support of the Catholics and the Free Church of Tonga, who may have been worried about their future freedom of religion rights.

The question of repealing the Latter-day Saint exclusionary law was finally brought before the Tongan Legislative Assembly on July 3, 1924, for debate and a vote. The day before, Siosaia Mataele suggested that as many members and friends as possible attend the legislative debate as a show of support. The debate in the legislature went back and forth; Fisi‘ihoi spoke in favor of the Church, while Tu‘ivakanō and Ata brought up spurious stories they could not support. Then Chief Justice Strong spoke up, saying that his “views of the Mormons during the past two years had undergone complete change. He had learned that the evidence on which he had condemned the Latter-day Saints was erroneous.”[41] Then several others spoke in the Church’s favor before the legislature broke for lunch. When the legislature reconvened, Speaker ‘Ulukalala called for a vote. The vote to repeal the three offending parts of the law was eleven for repeal and eight against. President Coombs was elated. Some of the langovaka that supported the Church through this difficult time were Fulivai, Vaea, Mataele, Manase Kaho, Fisi‘ihoi, and McOwan.

Nevertheless, because the embargo on issuing landing permits for Latter-day Saint missionaries throughout the British Commonwealth was still in force, by mid-1924, whenever an elder returned home, there was no one to take his place. Now Coombs was down to six elders in the mission. They were able to support only one school in each of the three island groups.

When the session of Parliament closed on July 10, President Coombs noticed that the queen seemed to have aged considerably. The repeal of sections 7, 8, and 9 of the Passport Act was officially published in the July 31 Government Gazette. One author wrote, “When Coombs received the official notice of the repeal, he sent a telegram to Salt Lake City informing President Grant of the good news. . . . To his dismay, on October 25, 1924 Coombs received a letter from the First Presidency congratulating him on the ‘splendid accomplishment’ but informing him of a tentative decision to withdraw missionaries from Tonga.”[42] Their letter explained:

We have had under consideration for several months the advisability of withdrawing from Tonga. Results obtained in that field are so completely out of proportion to the sacrifice of time and money expended by our people, we feel we will be perfectly justified in closing the mission. The Gospel has been preached in Tonga for more than thirty years. . . . We are of the opinion that if we withdraw from that field temporarily until conditions are more propitious and until the people are more prepared to receive and comprehend and appreciate the message that we have to bear, an injustice will be done to them. Indeed, such a move might have the effect of causing them to sense the importance of it.[43]

Historian R. Lanier Britsch concludes that the reason the offending parts of the Passport Act were repealed was not so much the powerfully written arguments in the petition but the troubles between the Free Church and the Wesleyans. “The trouble between the Tongan Free Church and the Wesleyan Church has caused intense feeling between all people. All the nobles except one . . . are with the Queen and the Wesleyan Church. The representatives . . . are generally against the Queen and the Wesleyan Church and hence will readily support any cause objectionable to the queen and nobles.”[44]

The day after receiving the letter from the First Presidency, President Coombs composed and posted a tender letter for the First Presidency expressing his profound feelings toward the Tongan people and the mission:

But oh, Brethren, if it is not too late, let me plead for my people. This is the hardest proposition that I have ever faced in my life, and Brethren, I would rather lay down my life for them than to run off and leave them leaderless. They are my people, I have made my greatest sacrifices for them and have used my God-given talents in their behalf; I have bought them with seven years of my youth. I have rejoiced when they have rejoiced and have gone down in sorrow with them. I do not want to persuade you against your better judgement, but if we could have only four missionaries we could, at least, hold our own.[45]

Locating Makeke

His fervent plea was heard and almost immediately things began to look up. Soon after the repeal of parts 7–9 of the Passport Act, President Coombs was talking to Mr. Gauld of Burns Philp & Co. and learned of a property belonging to a Mr. Miles that he wanted to dispose of. It was about eighty acres on the Liku Road south of Veitongo. On August 3 Mr. Miles took President Coombs out to look over the property. It ran from the government road to the sea and included nutmeg trees near the ocean and three acres of coconuts and bananas. There was also a four-hundred-gallon water tank and an iron shed. The whole property was fenced. Mr. Miles accepted President Coombs’s offer of £250 as it stood for his equity and a lease of four shillings per acre per year.

Coombs named it Makeke, meaning “awake and arise.” He joyfully wrote to Salt Lake: “Last week I got a 75-acre piece only 7½ miles from the center of Nukualofa. . . . The piece I have been successful in getting is all virgin land and all fenced around with barbed wire. It fronts the Government road and the sea extends along the complete back of the place, the good soil extending to the water’s edge.”[46] In 1925 President Coombs received authorization to lease an additional hundred acres across the government road, but this lease was never completed.[47] The lease for Makeke was for forty-five years and was officially registered in the land office on August 25. President Coombs wrote to the First Presidency of his actions and hoped they would support him.

As mentioned, because of the shortage of missionaries, the number of little primary schools had dropped from ten to three, one for each island group. Elder and Sister Leavitt were running the Ha‘alaufuli school, Elder Alden C. Glines was keeping the Pangai, Ha‘apai, school open, but the school at Matavaimo‘ui had to be closed for eighteen months for lack of a teacher.[48] With the government troubles largely over and with the likelihood of more missionaries coming, President Coombs envisioned a larger boarding school for children from all over the Kingdom of Tonga to receive the education they otherwise could not get. Perhaps something could be arranged along the lines of the Church’s Maori Agricultural College in New Zealand.

On September 4 the schoolboys from Matavaimo‘ui and some other brethren met at Makeke to begin clearing the bush, fixing fences, and planting gardens for the schoolchildren. By the end of October, Elder Reuben Wiberg told President Coombs that there was very little support for the schools on Tongatapu, so President Coombs decided to discontinue the schools indefinitely. Yet President Coombs later received a letter from the Presiding Bishopric approving his purchase of Makeke. There were regular workdays every Saturday, some better supported than others. The European missionaries on Tongatapu got to work on the school project, and each branch was assigned to send six men each week to help on a rotating basis. President Coombs also met Samuela Fakatou, who had been attending the Maori Agricultural College in New Zealand. The college president in New Zealand, Elder Stanley Kimball, said that Sam was the student body president and that the Tongan boys led out in all activities.[49]

Elder Reuben Wiberg was released on January 11, 1925, after serving more than four years, leaving only President and Sister Coombs on Tongatapu to supervise the affairs of the Church. That would leave only one Tongan-speaking missionary to help President Coombs, and he would need to be released soon. The other elders were new and inexperienced, so President Coombs had to consider calling local brethren to lead the districts. In Vava‘u he called Herman Wolfgramm as the first Tongan district president.

Surviving a Hurricane at Sea

Finally, on February 5, Coombs got word that Jay and Ada Cahoon, newlyweds who were both just nineteen, were on their way to Tonga, the first missionaries to come in nearly three years. They arrived on February 14, along with official word that the mission would not be discontinued and that it was authorized to buy its first automobile. Previously, the missionaries, including the president, got around by boat or on foot, horse, horse cart, or bicycle. And in 1925 transportation throughout the islands of the Kingdom of Tonga was rather irregular. Aside from the steamer Tofua, which made monthly calls, only smaller vessels sailed between the islands.

During this period, President Coombs had written out a release for Elder and Sister Leavitt, who were teaching school at Ha‘alaufuli (150 miles north of mission headquarters), and planned to take it to them along with the Cahoons, who were assigned to conduct the school there. President Coombs arranged to take them up to their new post on the single-masted schooner Makamaile and hold a district conference. This was usually a two-day sail.

The Makamaile was forty-five feet in length, with a fifteen-foot beam, a seven-and-a-half-foot draft, and a four-ton lead keel that tended to keep it upright. It had been built as a Norwegian Coast Guard lifeboat that was bought by writer Jack London and elegantly refitted and renamed Dream Boat. It was described as a very seaworthy craft. When he got to Tonga, London sold it after he stripped out all the luxurious fittings, leaving behind just three spare compartments. It was skippered by Sione Kongaika, a recent convert from Ha‘apai and crewed by Sami Mafileo and two other young men.

When the Makamaile left Nuku‘alofa, besides President Coombs and the Cahoons, the boat carried fifty or sixty Tongans, including Kitione and Lose Maile. Years later Jay Cahoon recalled the captain being called Sione Ika, or John Fish, and that there were ninety passengers. They left Nuku‘alofa at 4:00 p.m. on March 6 with fair winds. They hoped to be in Vava‘u the next day, but the winds died and they finally got to Lifuka, Ha‘apai, about half way, at 5:00 p.m. on March 7.

The next day they headed north at noon but got only as far as Ha‘ano when the wind died again. There they were able to visit with Sione and Nau Po‘uha, Fetu‘u Aho, and Siosaia Fatani. In the mailbags was the release notice for the Leavitts to catch the Tofua to sail for Fiji and on back to America, but on March 12 they saw the steamship Tofua pass by them on the calm sea.

Finally, on March 13 a favorable wind picked up from the south, and at 4:00 p.m. they were off again, hoping to be in Vava‘u the next morning. That evening the winds switched to the north and increased to gale force, then hurricane force. The following day the seas were higher than the mast, with waves at least fifty feet high. Captain Kongaika ordered everyone below deck and closed the door. Four old women were tied to the mast so they wouldn’t get washed overboard. Ada Cahoon went up on deck to get some fresh air, but Kitione Maile held on to her ankles in case a wave tried to wash her overboard; she estimated the waves to be ninety to one hundred feet. This was a terrifying sight for a girl from the prairies of southern Alberta. Vava‘u was in sight, but they were making no headway tacking into the wind. In fact, with the jib torn in half, they were losing ground with each tack. Sami Mafileo was tied to the tiller the whole night in case a wave tried to wash him overboard. His clothes were torn off, and he was trying to keep warm with regular doses of coconut oil on his bare skin. Food and water were gone. Babies were crying, and everyone was vomiting.

On Sunday, March 15, President Coombs relieved Mafileo at the tiller. The mainsail was torn to shreds, and the compass in the binnacle was smashed. President Coombs recalled:

I have on several occasions through the ordeal called upon the passengers to join me in prayer to ask the Lord to temper the winds, but to no avail. I finally asked Sione if it was possible to turn about and retreat to Ha‘apai. He said, “President Coombs, didn’t you say you have an appointment in Vava‘u for Conference?” When I assured him I did he continued: “Well, with the Lord as my helper I’m going to get you there.” What a man. Sione then reminded me that perhaps we had been praying for the wrong thing. Maybe we should, instead of asking the Lord to moderate the storm, we should ask him to give us the strength and know-how to get through. I thereupon called the passengers together in prayer and asked the Lord for that strength and ability to get through to our destination and appointments.[50]

By the next day Sione somehow managed to tie a portion of the mainsail together, and they began making a little headway with each tack. The rain ceased but the wind continued. As they finally passed Tu‘anuku and entered the channel to Neiafu, the winds died and they had to be towed in to the wharf. They arrived on March 16; the two-day voyage had taken ten days.

The lesson to be gained here comes from a new convert who had implicit faith that when the Lord calls, even though the path may seem impossible, the first step is to ask for wisdom on how to get through the ordeal. Then one should listen for the promptings of the Holy Ghost to grant that wisdom. Combined with Sione’s faith was his knowledge that when the Lord calls, he provides a way to accomplish the assignment.[51] After the conference feast the next day, Coombs kindly “sent a liberal portion of the food to the Captain and crew of the Makamaile.”[52]

An effective conference was held. The Leavitts got their release but had to wait four weeks for the next visit of the Tofua. The Cahoons began teaching school at Ha‘alaufuli, Jay taking the upper grades and Ada the younger children who spoke no English. She quickly learned to speak Tongan like a native.

One humorous incident occurred around this time. When the Ford motorcar the Presiding Bishopric authorized Coombs to purchase arrived in Tonga, it fell into the ocean when it was being off-loaded. Coombs refused to accept the car since “we Mormons were very peculiar and insisting in doing our own baptisms in our own way.”[53] A new car was sent and the old one soon rusted away. Coombs had never driven before, so he had Tupou Hettig teach him. On one of his first drives he ran over a huge pig and bent his driveshaft.

Building Makeke and Calling Local Missionaries

At the Tongatapu conference on April 19, nine local missionaries, some with their wives, were called to serve in the various branches on the island. Six more were called to serve at a July 11 conference at Ha‘alaufuli in Vava‘u, where a native, Herman L. Wolfgramm, served as the district president. With the shortage of foreign missionaries, the mission president for some time had depended on local missionaries to carry on the work. The local Saints responded admirably. At a faikava the evening of the conference, the brethren discussed building the schoolhouse at Makeke. The Tongan way was to give everyone an opportunity to voice their thoughts on such a community project.

School house at Makeke. Maurice

School house at Makeke. Maurice

Jensen collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

By May 15, 1925, the Saints were enthusiastically supporting the Makeke plantation. Various work parties had cleared and planted ten acres of kumala, or sweet potatoes. About two weeks later, the first Tongan house at Makeke was finished and a Tongan house used as a Matavaimo‘ui dormitory was moved out to Makeke, then a second fale was moved out two days later. President Coombs recorded on June 9 that he “received a request from the Presiding Bishop’s office requesting plans and specifications & estimates for Elders’ residence and school house at Makeke. Apparently, they approve of my application to build accommodations there at Makeke.”[54]

While at Vava‘u on July 17, Coombs received a wireless message from the First Presidency consisting of just one word: “BUILD.” Coombs wrote, “The Lord seems to be satisfied with my blundering so far or why would He keep me here for more than five years.”[55] The first job was to put up a pig-proof fence to keep the many wild pigs from invading during the night and eating their gardens. Next was a storage shed for the cement and other building materials. In addition, President Coombs wrote to President Grant, “I had had the dormitories, which had heretofore stood in our crowded back yard at Nuku‘alofa, moved out [to] the plantation and erected. We had also constructed a good hog-proof fence around the land. . . . As soon as word came from the First Presidency to go ahead with the building, Elder Fisher and I proceeded at once the building operations.”[56]

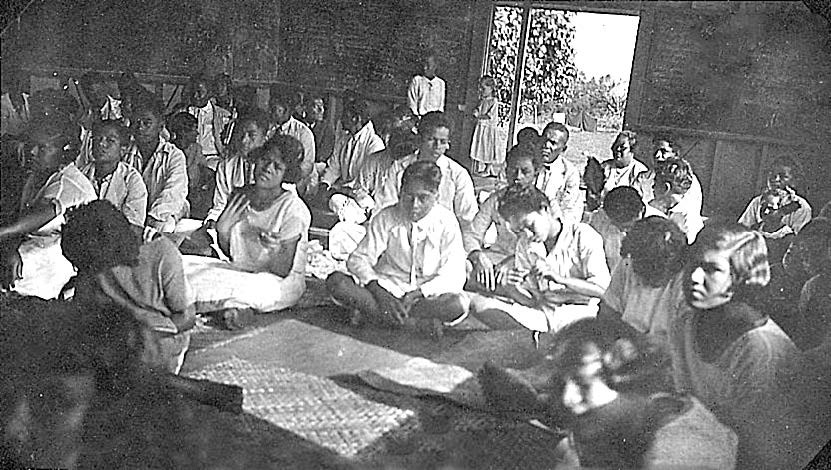

Forms were set, and the first batch of the concrete foundation was laid with a ceremony on October 7. Work continued steadily on the building. Groups of men would show up on a rotating basis. This was all accomplished with only basic hand tools. It was all done by the local Saints because President Coombs and Elder Fisher were the only missionaries from Zion on Tongatapu, and all worked nearly every day on the project. Two new elders arrived on November 25 and were put to work at Makeke the next day. There was little proselytizing being done, but the new elders were learning the language more quickly. On the last day of the year, President Coombs announced that they should open Makeke on the same day as the government schools, January 25, 1926. They hoped all would be ready. All students were to be at least fourteen years of age. However, there were some construction delays, and school opened a month later. During this period, President and Sister Coombs took Harry Selwood, headmaster of the government school, to see Makeke, and Mr. Selwood was quite impressed.

Inside the Makeke school room. Maurice Jensen collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Inside the Makeke school room. Maurice Jensen collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

The Tofua arrived from New Zealand on January 11, 1926, carrying recent graduates Samuela Fakatou and Misitana Vea, who had been studying at the M.A.C. for six years. President Coombs extended calls for them to serve local missions the same day. Samuela agreed immediately and was assigned to be a teacher at Makeke. Elder Maurice Jensen was placed in charge of the Makeke school and plantation with Lisione Manisela in charge of the dorms. Since the Church’s primary schools had been closed for a year because of a lack of teachers, the opening of Makeke created considerable interest. A mission-wide conference was held at Makeke from February 19 to 22, during which the Makeke College was dedicated by President Coombs. Then fourteen people were baptized in the ocean nearby. In addition, Misitana Vea, one of the M.A.C. boys, was called as a teacher at Ha‘alaufuli. On March 18 Coombs reported that Makeke had bountiful gardens and that the staff were catching plenty of wild pigs to eat.[57]

Nineteen twenty-six was also a year of trial as Tonga was experiencing the worst drought that Coombs could remember. Even the most resourceful Tongans were running out of food. Now that the Church had Makeke, Coombs counseled all branches to start community gardens wherever possible and offered space at Makeke.

Tongans at the Maori Agricultural College

Mission presidents in Tonga sent a number of young men to the Church’s Maori Agricultural College (M.A.C.), a boys’ boarding school in Hawkes Bay, New Zealand, for secondary education. Some boys stayed just a few years, but others remained and graduated. They returned to Tonga and most became leaders and educators in the Church in Tonga, especially during the years when there were so few missionaries from overseas—which was usually the case.

When these young Tongans arrived at the M.A.C., they usually had to undertake some remedial classes to prepare them for the secondary curriculum, but if they persevered, they usually became leaders in the school, both in the classroom and on the sports field. These young men and their years at the M.A.C. are worthy of remembrance: Samuela Fakatou (1918–25), Manase Mailangi (1919–21), John Philip (1919–20), Misitana Vea (1919–24), Pauliasi Pikula (1922–28), Charles Sanft (1922–25), William Sovea (1922–25), John Tuita (1922–28), Fred Davis (1923–25), Josiah Mateaki (1923–27), Viliami Naeata (1923–24), Wilhelm Schultz (1923–25), Ernest Wolfgramm (1923–25), Charles ‘A. Wolfgramm (1923–28), Tunifai Leao (1926–28), Tevita Maile Niu (1926–30), David Langi (1928–29), and Josiah Pahulu (1929–30). This same process of leaving Tonga for education and training and then returning to serve was repeated some forty years later when young men and women went to the Church College of Hawaii, then returned to build the kingdom of God in Tonga through their service in the Church schools and ecclesiastical leadership. They became a great blessing to the Church in Tonga.

In October 1925 one of the Tongan boys at the M.A.C., Ernest Wolfgramm, son of the Vava‘u district president, was diagnosed with leprosy, or Hansen’s disease. He was sent to the leprosy settlement on Makogai Island in Fiji. President Coombs received a wireless from the college on October 5 saying, “Wolfgramm at Makogai, Fiji.”[58] Because of the manual arts training Ernest Wolfgramm had received at the M.A.C., he became a very valuable person on Makogai. They even named a building after him. Before the M.A.C. closed in 1931 because of an earthquake, a group of Catholic nuns who served on Makogai visited the M.A.C. to see where this wonderful young man had received his training.

Jay A. Cahoon Replaces Mark Vernon Coombs

On May 2, 1926, the Tofua arrived bearing a letter from the First Presidency notifying President Coombs of his release and instructing him to turn over the mission to Elder Jay Cahoon, who, along with his wife, Ada, was running the school at Ha‘alaufuli. Coombs was quite surprised since Elder Cahoon had been in the mission only one year and was not yet twenty-one. Elder Cahoon had to be notified, trained, and introduced around the mission. “Jay and Ada Cahoon were quite unprepared for this turn of events and nearly wilted when they read the letter.”[59] In preparing to make the move down to Tongatapu, Sister Cahoon did not want to go on one of the small interisland sailboats like the Makamaile with her baby. The memory of her journey to Vava’u was too terrifying, and she preferred to wait for a larger vessel. After two weeks she and her baby were offered passage on the personal yacht of the Governor General of New Zealand, General Sir Charles Fergusson. While wrapping up his affairs in the mission, President Coombs arranged with Vehikite of ‘Otea to lease the beautiful property on the beach that became their chapel site and also with the high chief Tupou Kapetaua of Pangai to lease his land and house for a mission home in Ha‘apai.

As word of his release as mission president became public, it was recommended to the central committee of the Free Church by some of their ministers that they should offer the position of president of the Free Church to President Coombs. Coombs wanted to see what the people would think, so he held off making a reply. At an overflow meeting in the Pangai, Ha‘apai, chapel that could hold only seventy-five, he started by saying he might be inclined if the offer were properly put to him. The Saints gasped at his treachery. The members of other faiths were audibly pleased. Then he said he would accept if the Free Church would (1) swear to obey the same laws he did; (2) discontinue the use of tobacco, coffee, tea, and intoxicants; (3) repent the way he repented; (4) believe in the same Father and Son he believed in; (5) submit to the same baptism he did; (6) wholeheartedly sustain and support the same authorities he supported and sustained. The Saints were delighted while the Free Church crowd was disappointed when they realized that President Coombs did not have any intention of accepting the position as president of their organization. Coombs then addressed the rumor that he would be financially reimbursed when he went back to America. He replied that he would be reimbursed with a grant of land. It would be six feet long, three feet wide, and six feet deep.[60]

In Nuku‘alofa President Coombs took Elder Cahoon around to introduce him to all the government, business, and social leaders. Over the previous six years, President Coombs had made many good friends, and some said that he was the finest leader of any of the missions. He noted especially a group of Europeans that stood by them when the Church was not so popular with those in power. At a Makeke conference, President Coombs suggested that inasmuch as the school buildings at Makeke were just about finished, it was time for the elders to spend more time proselytizing. He also asked the Brethren to move the Church’s schoolhouse at Petani in Ma‘ufanga to Makeke.

President Jay and Sister Ada Cahoon with Orlene. Ralph Olsen missionary journal on FamilySearch.

President Jay and Sister Ada Cahoon with Orlene. Ralph Olsen missionary journal on FamilySearch.

The previous December, Stanley Prescott, a member from Australia who held the Melchizedek Priesthood, had arrived in Tonga on a one-year contract to work as a government accountant. President Coombs highly valued his friendship and expertise in helping him organize the finances and books of the mission and to help in the smooth transfer of the books to Elder Cahoon.

As they prepared to leave, President and Sister Coombs had the distinct impression that as young as they were, someday they would return. On June 30, 1926, President Coombs set Elder Jay Cahoon apart as the president of the Tongan Mission, and the Coombs family boarded the Tofua to head home. On board the Niagara from Suva to Honolulu, the Coombs dressed their four children in Tongan costumes, and because the children did not speak English, the passengers were very interested in them. Thus ended a most challenging but rewarding six years in Tonga for the Coombs family.

In the annual report for 1926, President Cahoon summarized his view of the mission: “There is a splendid spirit among the Saints throughout all the Mission, and the time is ripe for the work to progress here. But, sorry to say, there are such a few Elders from Zion here, and they have only a partial knowledge of the language that the work is not pushing ahead as rapidly as it should.”[61] When Elder Jay Cahoon, known as “Misi Kahuni,” assumed the presidency of the Tongan Mission on June 30, 1926, there were three conferences with the following branches: the Tongatapu Conference with the Nuku‘alofa, Fo‘ui, Nukunuku, Fahefa, Houma, Ha‘akame, Fua‘amotu, and Mu‘a branches; the Ha‘apai Conference with the Pangai and ‘Uiha branches; and the Vava‘u Conference with the Neiafu, Ha‘alaufuli, Mataika, Koloa, Tefisi, and ‘Otea Branches. There were a total of 1,096 members: 481 on Tongatapu, 202 in Ha‘apai, and 397 in Vava‘u. There were nineteen native elders, and many were serving as full- or part-time missionaries to supplement the few foreign elders. The mission books were all in order thanks to Brother Stanley Prescott. The new mission school at Makeke was in the middle of its inaugural year.

In a 1980 interview, Sister Ada Cahoon recalled that she and her husband were both very young and had never held any leadership positions, so they prayed a lot. She let the house girls take care of everything at the mission home while she spent much of her time translating Primary, Mutual Improvement Association, and Relief Society lessons into Tongan. It was mentioned in several places that she had learned to speak Tongan like a native while teaching the junior classes at the Church primary school in Ha‘alaufuli.[62]

A number of the foreign and local elders continued to build up Makeke. They completed an elders’ home that was dedicated by President Cahoon on September 24, 1927. Elder Ralph Olson noted that some Saints didn’t help at Makeke because they thought they ought to get paid. Elder Olson also mentioned that at this time they held priesthood and sacrament meetings only once a month in the Tongan Mission.[63] As principal at Makeke, Elder Maurice Jensen was replaced by Elder C. Sterling Cluff; then Elder Robert A. Nelson took over from him on September 27, 1929. There were generally one or two foreign elders teaching at Makeke and several Tongan teachers, usually graduates of the M.A.C.

President Cahoon sent monthly reports back to Salt Lake, and midway through 1927, he made this comment: “Our school at Makeke is a drawing card for the Mission, and . . . is doing wonderful work. The school is not very large, but certainly has the pick of the islands for students. The Primary schools in Vava‘u and Ha‘apai are likewise leaders in that class of school as is shown by the government inspector’s report.”[64] Elder Fred Stone recalled that seventy-five students showed up for the first day of school at Ha‘alaufuli on January 30, 1928, although many families could not afford the school fee of five shillings a semester.[65]

Makeke organized a rugby team that competed with the other secondary schools on the island. Some of the local teachers such as Samuela Fakatou and Misitana Vea had played for a very strong team at the M.A.C., some of whose members went on to play for the New Zealand All Blacks. During this time Fakatou and Vea also represented Tonga on its national team in matches against Fiji.

During President Cahoon’s term as president, he sought to mitigate the chronic shortage of elders from Zion by calling local elders who were usually married to serve with their families on short-term missions. “The local missionaries communicated well with their own people, learned to teach and defend the gospel, and, perhaps most important, strengthened their own testimonies of and commitment to the Church. And Tongan returned missionaries strengthened the local branches and districts.”[66]

Mission Progress as Newel J. Cutler Replaces Jay A. Cahoon

President Newel J. and Sister Floy Cutler and their children. Courtesy of Viliami Toluta’u.

President Newel J. and Sister Floy Cutler and their children. Courtesy of Viliami Toluta’u.

Newel J. Cutler, “Misi Semisi,” arrived as mission president on September 16, 1928, and Jay Cahoon was released after serving for twenty-six months as mission president. The Cahoons left on the same ship that the Cutlers arrived on, so there was not the usual overlap that allowed the outgoing president to brief the incoming one and to introduce him to the people he would be working with in the community. President Cutler had served as a missionary in Tonga from 1913 to 1919 and was well known to the older Saints.

On October 13 President Cutler assigned Elder Da Costa Clark to focus on developing a genealogical program throughout the mission. He recorded many faith-promoting experiences and miraculous healings during an epidemic of fever that killed many people but none of the sixty-five students at Makeke.

The service of the elders, both Tongan and from Zion, and the priesthood blessings they gave, made many new friends for the Church. The native priesthood brethren more than carried their share of the burden of missionary work and leadership. Elder Fred Stone recalled that Kalauta, the chief of Neiafu, said he believed the doctrine but was afraid of offending the queen.[67] In Ha‘apai, Elder Stone recorded that he organized a Boy Scout troop with thirteen boys.[68] Most branches had local leadership so the foreign missionaries could focus on proselytizing, holding cottage meetings, and serving at Makeke. On September 22, 1929, word came that another Tongan student at the M.A.C., Tevita Langi, had died of typhoid fever and was buried at the college.

In Ha‘apai it was normal for the elders to regularly spend a week or two visiting many of the little islands to the west. After getting permission from the chief of the island, they would hold a cottage meeting and then go on to the next island. Elder Fred Stone described one such circuit in July 1929, visiting Mo‘unga‘one, Fotuha‘a, Kotu, Matuku, Ha‘afeva, Tungua, and ‘O‘ua then back to ‘Uiha.[69]

At the end of 1930, the Church membership in Tonga stood at 554 for Tongatapu, 471 for Vava‘u, and 207 for Ha‘apai, making a total of 1,232 Latter-day Saints in Tonga.[70]

Notes

[1] Mark Vernon Coombs, “Missionaries in Tonga,” 1926, typescript in possession of the authors, see also Journal History of the Church, October 24, 1921, and Deseret News, December 10 and 17, 1921.

[2] Mark Vernon Coombs autobiography, 1920–1954, 1973, CHL.

[3] Ermel J. Morton, 20th-Century Western and Mormon Americana, Perry Special Collections (hereafter cited as Morton notes), page labeled “1920 land & schools” (no page number or date).

[4] Ermel Morton, Brief History of the Tongan Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Golden Jubilee (Suva: Fiji Times, 1968), 17.

[5] Coombs autobiography, 92 (February 13, 1922).

[6] Morton, Brief History of the Tongan Mission, 17–18.

[7] Coombs autobiography, 55 (May 8, 1921).

[8] Reid L. Neilson and Carson V. Teuscher, eds., Pacific Apostle: The 1920–1921 Diary of Mormon Apostle David O. McKay in the Pacific Island Missions (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2020), chapter 7. See Riley Moffat, “Apostle in Quarantine: Elder David O. McKay’s Visit to Tonga in 1921,” typescript in possession of the author.

[9] M. V. Coombs, “Apostle David O. McKay’s Visit in Tonga” (typescript, 1921), in possession of the authors.

[10] Coombs autobiography, 59 (June 12, 1921).

[11] Coombs autobiography, 59–60 (June 12, 1921).

[12] “Elder David O. McKay’s Visit to Tonga,” Deseret News, December 10, 1921, cited in MHHR, vol. 1, part 1.

[13] Coombs autobiography, 59 (June 12, 1921).

[14] Coombs, “Apostle David O. McKay’s Visit in Tonga.”

[15] Neilson and Teuscher, eds., Pacific Pioneer (relates a detailed account of their conversation in McKay’s diary for June 28, 1921). See Coombs autobiography, 60 (June 29, 1921).

[16] Coombs autobiography, 60 (June 29, 1921).

[17] Journal History of the Church, October 24, 1921. See also “Apostle David O. McKay’s Visit to Tonga,” Deseret News, December 10 and 17, 1921. For other accounts, see Morton, Brief History of the Tongan Mission, 21. See also Hugh J. Cannon and Reid L. Neilson, To the Peripheries of Mormondom: The Apostolic Around-the-World Journey of David O McKay, 1920–1921 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2011), 101–6, and Clare Middlemiss, Cherished Experiences from the Writings of President David O. McKay (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1955), 103–14.

[18] Coombs autobiography, 61 (June 30, 1921).

[19] Coombs autobiography, 62 (July 3, 1921).

[20] M. V. Coombs to J. F. Wells, November 8, 1921, CHL and MHHR, November 8, 1921.

[21] Morton, Brief History, 21.

[22] Coombs autobiography, 104 (June 29, 1922).

[23] R. Lanier Britsch, “Mormon Intruders in Tonga: The Passport Act of 1922,” in Mormons, Scripture, and the Ancient World: Studies in Honor of John L. Sorenson, ed. Davis Bitton (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998), 121–48.

[24] There was a strong bias against Latter-day Saints in Britain that impacted the Church’s ability to secure landing permits for its missionaries not only in Britain but also throughout the Commonwealth. See Malcolm R. Thorp, “The British Government and the Mormon Question, 1910–1922,” Journal of Church and State 21, no. 2 (1979): 305–24. This was portrayed in the British public eye by such scandalous films as Trapped by the Mormons. Tonga, in particular, was following the example of New Zealand on this issue.

[25] R. Lanier Britsch, Unto the Islands of the Sea: A History of the Latter-day Saints in the Pacific (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1986), 441–42.

[26] Coombs autobiography, 104 (July 18, 1922).

[27] Britsch, Unto the Islands of the Sea, 441.

[28] Coombs autobiography, 105 (July 3, 1922).

[29] Coombs autobiography, 106 (July 5, 1922).

[30] Morton, Brief History of the Tongan Mission, 22. This was a worldwide issue for the Church. An overview can be found in Thorp, “British Government and the Mormon Question,” 308–24.

[31] Britsch, Unto the Islands of the Sea, 442.

[32] Morton notes, ca. 1922–23.

[33] See full text in Coombs autobiography, 113–20 (November 3, 1922).

[34] See Britsch, “Mormon Intruders in Tonga,” 121–48. See also Thorp, “British Government and the Mormon Question,” 308–24.

[35] Morton notes, ca. 1923.

[36] Coombs autobiography, 121 (December 2, 1922).

[37] Morton notes, ca. 1922.

[38] Coombs autobiography, 125 (March 9, 1923).

[39] Unlike members in New Zealand and Samoa, only four Tongan families ever had the opportunity to go to the temple prior to 1958, when the New Zealand Temple was dedicated.

[40] The text of this lengthy petition is in Coombs autobiography, 168–88 (May 4, 1924).

[41] Coombs autobiography, 196 (July 3, 1924).

[42] Britsch, “Mormon Intruders in Tonga,” 139–40.

[43] Morton, Brief History of the Tongan Mission, 23–24.

[44] Britsch, Unto the Islands of the Sea, 444.

[45] Britsch, Unto the Islands of the Sea, 444–45.

[46] Morton notes, August 1924.

[47] Morton, Brief History of the Tongan Mission, 24.

[48] Morton, Brief History of the Tongan Mission, 24.

[49] Coombs autobiography, 208 (November 23, 1924).

[50] Coombs autobiography, 222 (March 15, 1925). See also M. V. Coombs, “A Thrilling Experience and a Testimony,” Improvement Era, February 1922, 407–11, and Ada Cahoon interview by Vai Latu, 1980.

[51] Coombs autobiography, 222 (March 15, 1925), and Jay Cahoon interview, 1980. See also Riley Moffat, “A Lesson in a Hurricane” (typescript, 2018), in possession of the author.

[52] Coombs autobiography, 222 (March 17, 1925).

[53] Coombs autobiography, 226 (April 3, 1925).

[54] Coombs autobiography, 237 (June 9, 1925).

[55] Coombs autobiography, 245 (July 17, 1925).

[56] Morton, Brief History of the Tongan Mission, 25.

[57] Coombs autobiography, 290 (March 18, 1926).

[58] Coombs autobiography, 260 (October 5, 1925).

[59] Coombs autobiography, 298 (May 2, 1926).

[60] Coombs autobiography, 304–5 (May 23, 1926).

[61] Morton, Brief History of the Tongan Mission, 27.

[62] Ada Cahoon, interview by Vai Latu, 1980.

[63] Ralph Dallas Olson missionary journal, 102 (January 1, 1928).

[64] Morton, Brief History of the Tongan Mission, 27.

[65] Fred Stone journal, 1926–1968, January 4, 1928, MS 900, CHL.

[66] Britsch, Unto the Islands of the Sea, 449.

[67] Stone journal, January 17, 1929.

[68] Stone journal, May 17, 1929.

[69] Stone journal, July 17–23, 1929.

[70] MHHR, December 31, 1930.