Setting the Stage

Riley M. Moffat, Fred E. Woods, and Brent R. Anderson, "Setting the Stage," in Saints of Tonga (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 1–8.

Geography and Settlement of Tonga

All history takes place on the stage of landscape. It has a geographical as well as a temporal dimension. In Tonga the stage is a bit different than most.

The Tongan Islands are scattered along the eastern edge of the Australian tectonic plate for five hundred miles as it overrides the Pacific Plate between the latitudes of 15 and 23 degrees south. The islands are south of Samoa and east of Fiji (see book endpapers). The Tongan Islands include 176 islands, 36 of which are inhabited, totaling only 277 square miles. Three main island groups include Tongatapu in the south, Ha‘apai in the middle, and Vava‘u in the north. Two chains of islands run north and south—the high volcanic chain of islands to the west that are generally uninhabited except for Niuafo‘ou and Niuatoputapu in the north and the lower limestone or coralline islands on the east along the edge of the tectonic plate from Vava‘u south 200 miles to Tongatapu and ‘Eua. Beyond these islands to the east lies the Tonga Trench, the second deepest in the world at 35,702 feet, or 10,882 meters. Tonga lies at the southern edge of the tropics, so there is a slight seasonal variation. Hurricanes, called cyclones in that part of the world, and earthquakes are occasional natural hazards.

The Tongan Islands are thought to have been discovered and inhabited about three thousand years ago by the Lapita people, who arrived from the west. They were so called from their style of pottery, which died out after they reached Tonga and Samoa in western Polynesia because they could not find the right clay for making their pottery.[1] This sort of material culture is used to date the migrations of early Pacific peoples. While this origin for the peoples of Polynesia is very strong, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints believes that migrations of people from the Americas brought the blood of Israel into the Pacific.[2] Genealogies of the chiefly lines extend back over one thousand years to ‘Aho‘eitu, the first Tu‘i Tonga, or Lord of Tonga. Tongan society has always been highly structured with a high value placed on obedience to established authority—this made acceptance of Christian authority easy to embrace. When discovered by Westerners, there were perhaps thirty thousand Tongans living on the islands. However, during most of the nineteenth century the population is thought to have been down to around twenty thousand because of introduced disease and internal conflict.[3] Tongans were notable voyagers ranging far and wide across the Pacific.

Tonga Becomes Christian

The islands were visited by Dutch explorers Jakob Le Maire in 1616 and Abel Tasman in 1643 and by British explorer James Cook between 1773 and 1777, who named them the Friendly Islands and really put them on the world map. After that there were regular visits by other Western explorers and traders. As Westerners created a written form of the Tongan language they used a g for the ng and a b for the p sound until after World War II when Crown Prince Tungī corrected it, thereby rendering “Togatabu” as “Tongatapu.” The authors have chosen to use the current spellings except in the case of direct quotes.

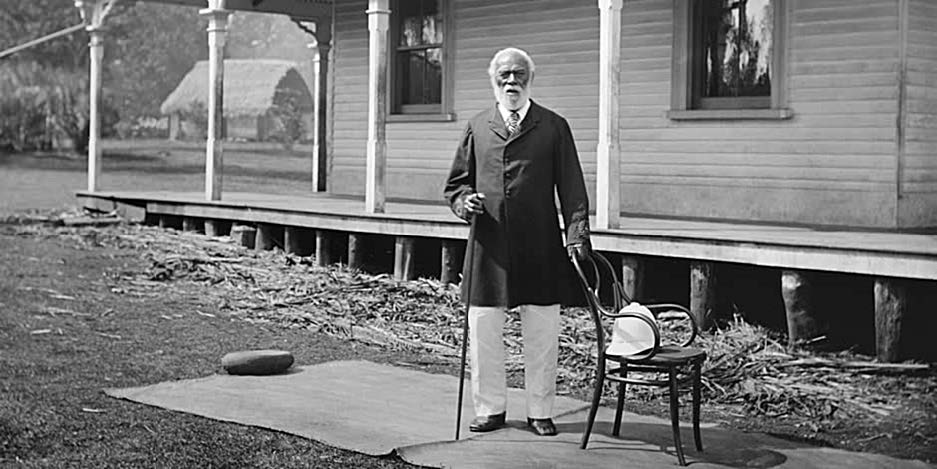

The London Missionary Society (LMS) attempted to introduce Christianity to Tonga as early as 1797 when the LMS ship Duff dropped off George Vason and others on Tongatapu. This attempt was woefully unsuccessful, but the Society tried again in 1822 with Reverend Walter Lawry, who left after a year. Finally, Wesleyan Methodist missionaries John Thomas and John Hutchinson established a permanent mission station in 1826 at Ha‘atafu and later at Nuku‘alofa.[4] An early significant convert was the chief Taufa‘ahau of Ha‘apai, who was baptized a Christian in 1831. Like the Hawaiian chief Kamehameha the Great, Taufa‘ahau unified the Islands of Tonga through a series of wars from 1826 to 1852. He assumed the chiefly title of Tu‘i Kanokupolu in 1845 and declared himself King George in 1852. He, along with most other Tongans, accepted Christianity for both spiritual and material reasons, seeing Western ways and the Christian God as superior to their traditional gods. This became one of the most pivotal events in Tonga’s history. Taufa‘ahau also recognized the competition by Western powers to colonize the Pacific and the need to align with one of them for protection. On November 29, 1839, at Pouono in Neiafu, he chose to dedicate Tonga to God,[5] viewing education and Christianity as the path to Western wealth. Tonga’s internal conflicts caused the people to move off their ‘api ‘uta (plantations) and congregate in villages around their churches and schools for protection.

King Siaosi Tupou I. Wikimedia Commons from the Hocken Collection.

King Siaosi Tupou I. Wikimedia Commons from the Hocken Collection.

The Catholics entered Tonga and set up a mission station at Pea in 1842[6] to compete with the Methodists for converts; they used the threat of intervention by French warships to solidify their position. They later moved their headquarters to Ma‘ufanga in 1885. These threats to Tongan sovereignty worried King George and the Methodist missionaries until the government was able to negotiate treaties with Germany and Britain recognizing Tongan independence. There had been an informal agreement between the various existing Protestant missionary groups in the Pacific since 1830 that the Methodists would supervise the Christianization of Tonga, so other religions were considered interlopers.

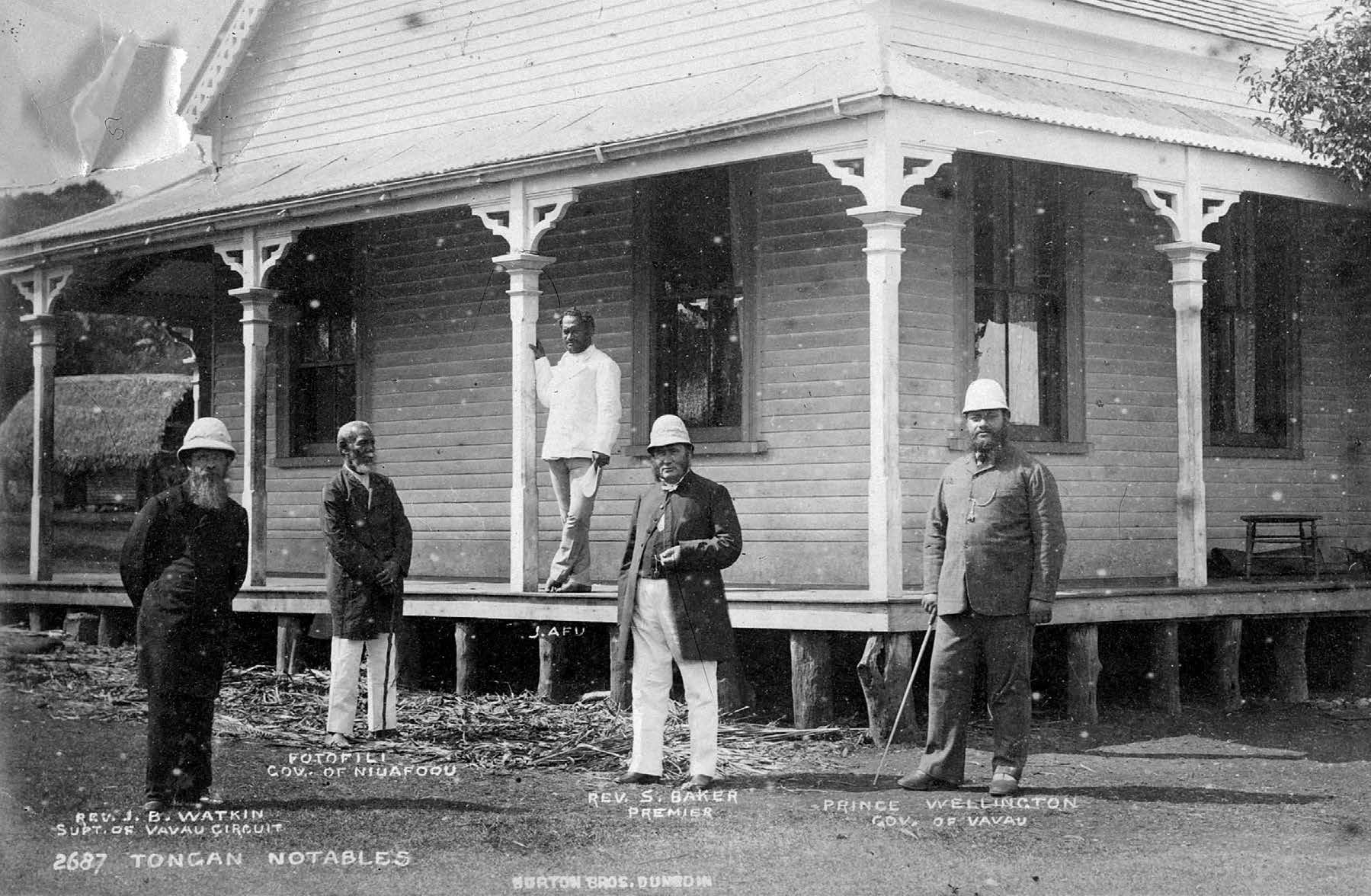

In 1860 a Methodist missionary named Shirley Baker arrived from Australia and became a confidant and adviser to King George. Baker advised the king on ways to preserve his independence and control the influence of the foreign traders and planters. He was an efficient and loyal servant of the king, which created animosities against the expatriate community as he strengthened the power of the monarch, sometimes at the expense of foreign interests. By 1879 King George named Baker as premier. Baker was instrumental in establishing the constitutions of 1862 and 1875.

Tongan notables ca. 1884. Left to right: Rev. Jabez B. Watkin, Fotofili, J. Afu, Rev. Shirley Baker, and Crown Prince Wellington Ngu. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Tongan notables ca. 1884. Left to right: Rev. Jabez B. Watkin, Fotofili, J. Afu, Rev. Shirley Baker, and Crown Prince Wellington Ngu. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Shirley Baker convinced the king that the relationship between the Methodist Church in Tonga and the church headquarters in Sydney was not in Tonga’s best interest. The king wanted a church independent and autonomous from Australia. Among other things, this would mean that all donations collected in Tonga would stay in Tonga. In January 1885 Baker announced the formation of the Wesleyan Free Church of Tonga, and the king advised all his subjects to switch allegiance. In this Baker was opposed by another Methodist missionary named James Moulton who had come to Tonga in 1865 to establish Tupou College. The king threatened retaliation to those who did not switch, then followed through with some of those threats. Baker and the king were adamant and would not consider reunification. Significantly, this expatriate prime minister instigated a division and contention in Tongan religious society that has not been resolved to this day. There were complaints to the British colonial authorities, who eventually deported Baker in 1890.[7] The new prime minister, Siaosi U. Tuku‘aho, educated at Tupou College and supported by the expatriate community and British assistant premier Sir Basil Thomson, pardoned all who had remained loyal to the Methodist Church. By 1891 Tuku‘aho and Thomson got the government functioning again.[8]

The constitution of 1875 guaranteed religious freedom, but there was still animosity and competition between the existing churches, and bad memories persisted. There also existed a de facto state church with the king as its head, which gave it cultural and political clout. Ever since 1830 the Wesleyan Methodists believed they had a monopoly on Christianity in Tonga, and since 1847 the Catholics had been tolerated. But none of the existing churches in Tonga wanted to see any new interlopers competing for the souls of the Tongan people. The government was heavily reliant on the advice of European ministers from the established churches who naturally wanted the status quo preserved. To fully understand the context of the social, political, and economic situation in Tonga that the missionaries and members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints faced throughout its history, the authors recommend consulting Ian C. Campbell’s Island Kingdom: Tonga Ancient and Modern.[9]

Arrival of the Elders

Elders Brigham Smoot and Alva Butler, the first Latter-day Saint missionaries in Tonga, entered into this milieu on July 15, 1891.[10] Elders Smoot and Butler had been called to labor in the Samoan Mission, which had been established only three years before, in 1888. Elder Smoot had arrived in Samoa on June 17, 1889,[11] and Elder Butler on June 14, 1891.[12] President William O. Lee, president of the Samoan Mission, decided to reassign Elder Smoot to Tonga on June 15, 1891.[13] The following day Smoot was appointed as the presiding elder of the Tonga Conference, or district, of the Samoan Mission. He selected Elder Alva Butler to be his companion.[14] Elder Smoot had already learned the Samoan language, and it may not be coincidental that he and Butler met a native Tongan named Mataele in Samoa who helped them learn some Tongan and prepared them to preach the gospel in the Tongan language.[15] This was to be one of the first of many “coincidences,” or tender mercies, that helped establish the Church in the Kingdom of Tonga.

Notes

[1] See Patrick Kirch, “A Trail of Tattooed Pots,” in A Shark Going Inland Is My Chief (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 21–37, and his The Lapita Peoples: Ancestors of the Oceanic World (Oxford: Blackwell, 1997).

[2] This possibility of American contact has been demonstrated by Thor Heyerdahl in his Kon-Tiki and American Indians in the Pacific, also DeVere Baker in The Raft Lehi IV. For genealogical relationships, see Russell Clement, “Polynesian Origins: More Word on the Mormon Perspective,” Dialogue 13, no. 4 (1980): 88–98; also Bruce Sutton, Lehi, Father of Polynesia: Polynesians Are Nephites (Orem, UT: Hawaiki, 2001); and William Cole and Elwin Jensen, Israel in the Pacific: A Genealogical Text for Polynesia (Salt Lake City: Genealogical Society, 1961).

[3] The first official census, held in 1900, recorded 20,019 inhabitants of Tonga.

[4] A. H. Wood, A History and Geography of Tonga (Auckland, New Zealand: Wilson & Horton, 1943), 45.

[5] Eric B. Shumway, producer, Tuku Fonua: The Land Given to God (Nuku‘alofa: The Government of the Kingdom of Tonga, 2007), DVD.

[6] Ian C. Campbell, Island Kingdom: Tonga, Ancient and Modern, 3rd ed. (Christchurch: Canterbury University Press, 2015), 90–91.

[7] Noel Rutherford, Friendly Islands: A History of Tonga (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1977), 54–172. See Sione Latukefu, Church and State in Tonga (Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1974), and Noel Rutherford, Shirley Baker and the King of Tonga (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1971).

[8] British consul Roger Beckwith Leefe played little part in the day-to-day affairs of the kingdom during this rebuilding phase.

[9] Campbell, Island Kingdom.

[10] R. Lanier Britsch, Unto the Islands of the Sea: A History of the Latter-day Saints in the Pacific (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1986), 431–33.

[11] Brigham Smoot journal, June 17, 1889, Perry Special Collections.

[12] Smoot journal, June 14, 1891, notes that Butler arrived in Samoa with several other missionaries on June 14, 1891.

[13] Smoot journal, June 15, 1891. Here Smoot wrote, “Never before did I receive such a birthday present and such a surprise as when appointed President of the Tongan mission.”

[14] Smoot journal, June 16, 1891. Herein, Smoot described how Butler was selected as his companion: “Bro Lee and I took a walk to see if one of [the] new Brethren could be settled upon as a partner for me. Neither of us could decide between Bro. Van Cott and Butler, so I suggested that we follow the example of the ancient Apostles viz. Pray and cast lots. We did so. The lot fell to Bro. Butler.” See also Samoan Mission manuscript history, 1888–1891, CHL.

[15] Smoot journal, June 12, 1891: “My Tongan friend . . . called about 3 P.M. and spent the day. Had a fine lesson and finished translating the ‘Articles of Faith.’” Thus, Smoot had a translation of the Articles of Faith to read to the king of Tonga before he ever left Samoa.