Returning to Establish a Mission (1907-19)

Riley M. Moffat, Fred E. Woods, and Brent R. Anderson, "Returning to Establish a Mission (1907-19)," in Saints of Tonga (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 53–92.

In Tongan shipbuilding, langovaka are the poles that hold up the hull of the boat during its construction on the beach. When the boat is finished, the poles are pulled down and placed under the keel, and the boat is slid down the poles into the water. The function of the langovaka in this process can describe the role of the ruling class in relation to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as it was being introduced into Tonga. In this analogy the boat is the Church with its members and organization; the poles are the supporters who are not members.[1]

Since 1891, when the gospel was first introduced into Tonga, a few embraced the gospel, were baptized, and were faithful to their testimonies. They made up the structure of the boat. The langovaka were those who supported the Church in various public or more private ways but for various reasons did not join the Church. This includes many of the ruling class of nobles, chiefs, and even ministers who may have believed the doctrines the missionaries taught or appreciated their good works, but for various personal, political, or economic reasons did not feel they could publicly align themselves with the Church and be baptized. Given the public relationship between the Protestant churches and the ruling class, there was just too much social pressure against supporting The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. To break away and join a new and different movement such as the Latter-day Saints would be seen as jeopardizing their position in a ruling class where position depended on the favor of the king and other nobles, who were heavily influenced by the ministers of the other churches.

The Tongan District of the Samoan Mission did not produce sufficient success in the eyes of Church leaders from 1891 to 1897 to warrant its continuation and was therefore closed. Some of the few members baptized in Tonga decided to leave. The Robert Crichton family moved to Samoa soon after baptism, and on October 31, 1901, the James Edward Giles family passed through Samoa on their way to America at the invitation of Elder Welker. In researching the history of the Church in Tonga, Ermel Morton found notes from 1922 by Mark Vernon Coombs that identified a few baptisms of Tongans apparently living in Samoa from 1901 to 1905, years in which Tonga was closed to missionary work. They were performed by elders serving in the Samoan Mission, which had jurisdiction over Tonga.[2]

Reopening Vava‘u

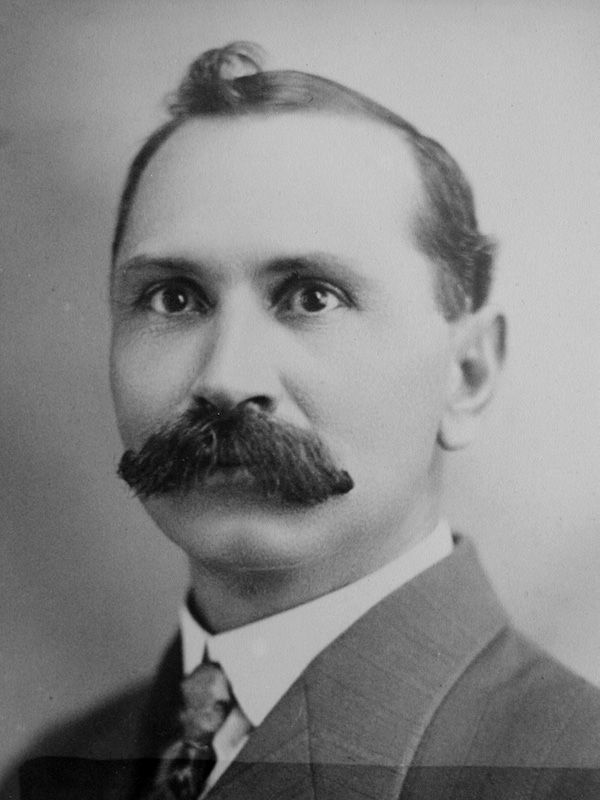

Samoan Mission president Thomas S. Court. Courtesy of Perry Special Collections.

Samoan Mission president Thomas S. Court. Courtesy of Perry Special Collections.

On March 19, 1907, Samoan Mission president Thomas S. Court decided to go to Vava‘u incognito to investigate prospects for reopening missionary work and, if possible, to buy some horses for the Samoan Mission. Since there was no hotel in Neiafu, he lodged with Iki Tupou, the harbormaster. Court soon found out he was living next door to where the elders had lived in the 1890s with Sione Pota Uaine. Court was then invited to hold meetings. He would preach in Samoan, then a Samoan member, Enele, living in Vava‘u, would explain Court’s message in Tongan. President Court found that ‘Isileli Namosi, Iki Tupou’s cousin who had been baptized in 1896, was still “true to the Church.”[3]

While Court was there, Tupou requested that he send missionaries to open a school and teach his children some English. President Court returned to Apia on April 11 with two horses he bought from the high chief Kalauta, the father of Fale Kava. He viewed the “prospects very bright” for Tonga.[4] Court had had some good meetings in Vava‘u and found a couple of old members. Two days later at a conference in Sauniatu, Upolu, Samoa, President Court assigned Elders William O. Facer and Heber J. McKay to go to Vava‘u. He said the people at Vava‘u “desired a school and also some elders to preach the gospel to them.”[5] The desire of the Tongans for education, particularly English language skills, was very strong.

Elder Heber J. McKay. Courtesy of Family History Library.

Elder Heber J. McKay. Courtesy of Family History Library.

Elders McKay and Facer arrived at Neiafu, Vava‘u, on June 13, where they met Iki Tupou, the very person Ermel J. Morton said had asked President Court to send the missionaries. Iki took the elders to meet his first cousin ‘Isileli Namosi. Namosi had been offered the noble title of Fulivai, but the offer was withdrawn when people learned he had joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Namosi offered the elders a place to rent and a large room to hold school at Mata‘utuliki in Neiafu. Elders McKay and Facer started a day school for children on June 24 and later a night school for ten adults desiring to learn English. Missionary work was slow until November 19 when they healed one of Iki Tupou’s children during a whooping cough epidemic. This healing was the impetus for many people asking the elders for priesthood blessings; in fact, so many that Elder McKay wrote President Court asking if there were any precautions needed with so many requests for the elders to heal their children.[6]

By January 13, 1908, Elder McKay reported that fifteen Tongans were attending their meetings along with twenty-eight students in the day school and thirteen in the night school.[7] The schoolhouse on Namosi’s property became too small, so the elders rented a room in the king’s palace in Neiafu.[8] Iki Tupou was baptized in January, and a branch was organized in Neiafu. A third elder, Marcus E. Woolley, arrived in Vava‘u on January 20, 1908, to help out. Ten days later, Elder McKay reported there were now thirty pupils attending the Neiafu school and that Elder Facer had been offered room and board and even money to start a school at the village of Mataika.[9] Elder Facer accepted the invitation but soon found that the Mataika people were interested only in the school, not the Church.

The new Samoan Mission president, William A. Moody, came to Vava‘u on November 24, 1908, to check on the progress of the work. While he was there, nine people were baptized. Interestingly, the first seventeen baptisms in Vava‘u were men. Moody returned to Samoa on December 15.

President Moody returned and held the first conference in Vava‘u on July 9, 1909, and twelve converts were baptized. He spent two months in Tonga, where there were now six elders laboring in Vava‘u with the addition of Elders Leonard Ormond, John Olsen, and Brent Wright.[10] Moody wrote, “The work in that conference [district] is progressing by leaps and bounds.”[11] When President Moody left to return to Samoa on August 25, he stopped at Ha‘apai, where he found that again the people wanted a school more than they wanted the gospel, so he decided not to send missionaries there. Apparently, he did not encounter any of the people who had been baptized in the 1890s.

Samoan Mission president William Moody. Courtesy of Carl Harris.

Samoan Mission president William Moody. Courtesy of Carl Harris.

The big news was that while Elder Facer was holding school in Mataika in March 1909, a delegation of three men, Semisi Fifita, Inoke Losaka, and Tali,[12] came from the village of Ha‘alaufuli and invited him to come there not only to start a school but also to preach the gospel to them. The village would provide room and board and a place for a school and chapel. By April, fifty students were enrolled in the school; this number included nearly everyone in the village between the ages of five and twenty-five. Elder Facer said there were baptisms every week, including the mayor, the town board, and the chiefs.[13] Within a month, thirty-two converts were baptized, and soon a branch was organized with seventy-five members. Plans were made by the members to purchase the property the school was on for the Church. The Church members organized themselves and spent three months collecting coconuts to make copra, which they sold to have money to purchase the property.

In Ha‘alaufuli, Elder Facer lived with an older couple named Tali and Lupe. Facer said when he first arrived a priest came and told Tali and Lupe that the Latter-day Saint missionary would consume all their food. When there was little fruit on most of the breadfruit trees a few months later, the priest asked, “How come, Tali, you have fruit on your trees when there is none on any others?” Tali replied, “Well, if you want to have fruit on your trees all the time just get a Mormon missionary to live with you and you will never want for food.”[14]

Mark Vernon Coombs, mission president from 1920 to 1926, related the story of one early faithful convert in Ha‘alaufuli, high chief Pita Afu, who was visited by the king and a delegation of other high chiefs who asked him to leave the Church of Jesus Christ and return to the king’s church. They were on a hill overlooking Ha‘alaufuli and much of the rest of Vava‘u. The king told Pita he could have any part of the land he could see as an inheritance if he would leave the Latter-day Saints. Pita Afu replied, “With all due respect to your majesty and to you other high chiefs, there is not enough land in the whole Kingdom of Tonga to tempt me away from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.”[15]

Soon after Elder Facer went to Ha‘alaufuli, Elder Woolley went farther down the road to Koloa and started a school and branch in 1909; another school and branch were started at the village of ‘Otea on the island of Kapa.

In 1910 President Moody sent two Samoan sisters, Malia and Lillie Joseph, mother and daughter, to Vava‘u to start the Relief Society and Primary programs.[16] The first Relief Society meeting was held at Ha‘alaufuli on May 29 with President Moody in attendance.

While serving as a missionary in Samoa, Elder Don Carlos McBride was called and set apart as president of the Samoan Mission by predecessor William M. Moody on July 31, 1910. McBride went to Vava‘u on November 24 to check on the district. In a meeting at Koloa, he assigned Elder Earl to go to Niuafo‘ou to assist Elders Wright and West, who were already there, but there was no further report on any progress made on Niuafo‘ou. On Vava‘u, however, there was considerable success, and more elders were sent from Samoa. Up until 1911 the Tongan Conference of the Samoan Mission really included only the islands of Vava‘u.

Much of that success was with the half-caste community, particularly the Wolfgramms and Sanfts, who descended from German immigrants who had come to Tonga to operate copra plantations and other commercial establishments and had married local women.[17] These half-castes may not have felt the same fatongia (obligations) to the nobles and chiefs that other Tongans felt and therefore were more open to accepting new ideas from the Latter-day Saints. Much support was given the missionaries by a former sailor from Norway named Jacob “Sekope” Olsen, who had settled in Vava‘u years before and had remained faithful along with his wife since their baptism in 1897. The few people baptized on Tongatapu and Ha‘apai in the 1890s had been so humiliated by their family and friends that they would have nothing to do with the Church when it returned, probably fearing that they would be abandoned again.

With the Church of Jesus Christ firmly established in Vava‘u, President McBride considered introducing the gospel to other parts of Tonga. Undoubtedly, members from Vava‘u were already sharing bits of Church doctrine as they traveled around the kingdom. In 1910 a woman named Lolohea Mataele from Fo‘ui, Tongatapu, brought a letter from her husband, Siosaia Mataele, to Vava‘u asking for elders to come to Tongatapu. Perhaps Siosaia Mataele and Iki Tupou Fulivai were friends, and Mataele was aware of the elders and their schools in Vava‘u.

Reopening Tongatapu and Establishing Schools

Elder W. Frank Winn. Courtesy

Elder W. Frank Winn. Courtesy

of Family History Library.

At a conference in Vava‘u on February 17, 1911, Elders Frank Winn and George Seeley were called to go to Tongatapu and establish the work there. They arrived in Nuku‘alofa on March 17 and met a young man named Fale Kava whom they had known earlier in Vava‘u. The letter advising Mataele that the missionaries were coming had not arrived, so Fale Kava invited the missionaries to his house in Nuku‘alofa. Two days later, they held a cottage meeting in Fale Kava’s home in the Kolofo‘ou neighborhood of Nuku‘alofa that was attended by thirty-five to forty investigators. The next day, March 20, they were asked to start a school in Nuku‘alofa. Two days later, Elder Winn recorded that men came from Fo‘ui asking him to come visit chief Siosaia Mataele. It was Mataele’s wife, Lolohea, who had gone to Vava‘u to ask for missionaries to come to Tongatapu. Elder Winn went and held a cottage meeting, which forty-five investigators attended. He talked to Mataele about starting a school, but he found that Mataele was more interested in a school than in the gospel, so Winn proceeded to leave only to be called back by Mataele’s wife, Lolohea, who was interested in the gospel. A school was finally started at Fo‘ui in April with sixteen students enrolled. The first baptism at Fo‘ui was Siosaia’s son Maile Mataele on August 9, 1911. His parents, Siosaia Mataele and Siosaia’s second wife Tokelupe, were later baptized by Elder Clarence Wiser on October 13. They and their posterity became very influential in helping the missionaries and opening doors for the elders to preach the gospel.[18]

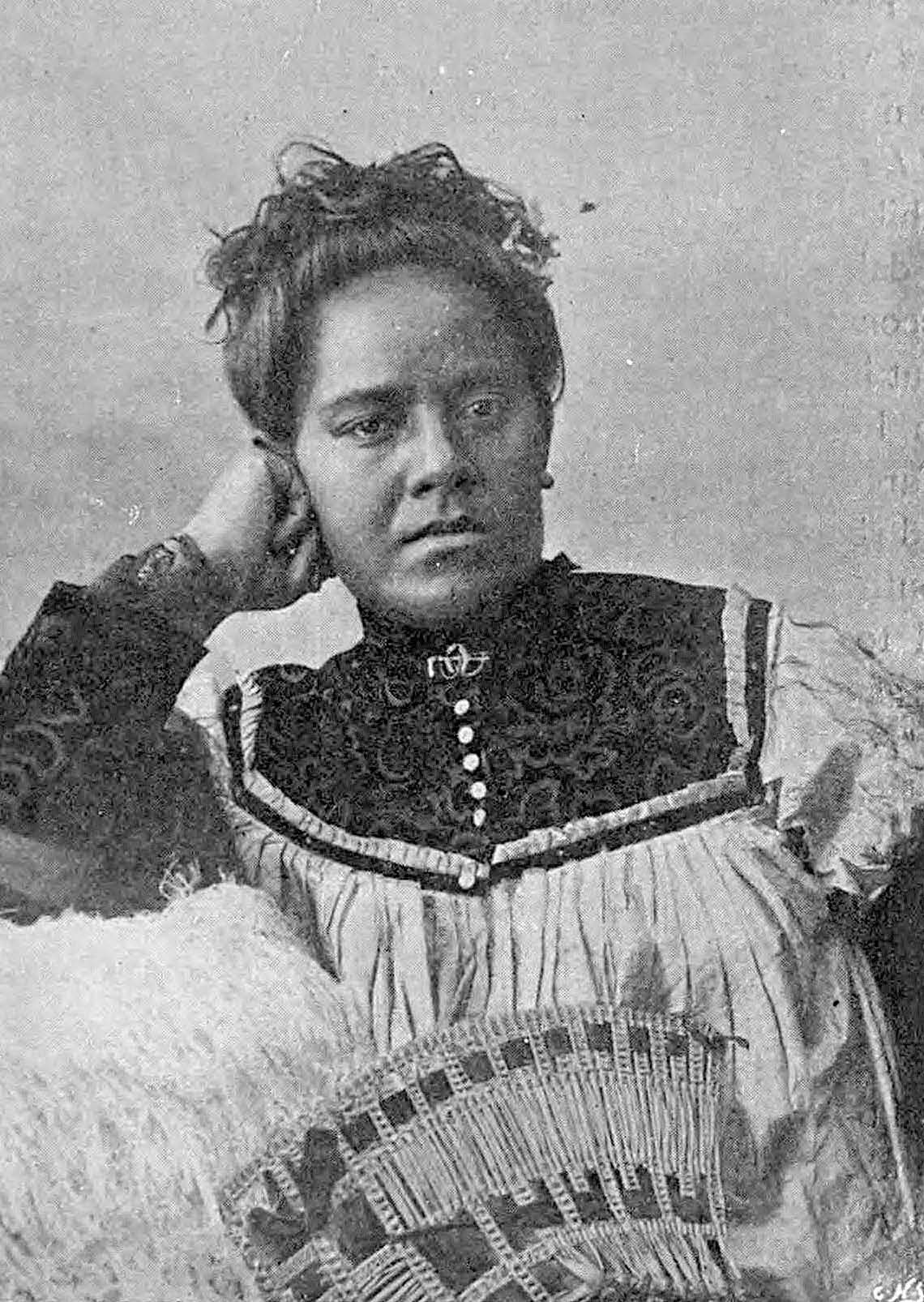

Back in Nuku‘alofa, Elder George Seeley started a school in the Ma‘ufanga district on March 27 and a night school for some older boys on May 1. By that time fifty to seventy-five investigators were attending cottage meetings in Nuku‘alofa. President McBride arrived on June 8 to see how things were going on Tongatapu and appointed Elder Winn as president of the new Tongatapu Conference. Two more elders, Abiah W. Miller and W. J. Siddoway, also arrived. While there, President McBride held a conference and the first baptisms on Tongatapu took place on July 15: Tevita Fatongia, Mele Tupou Moheofo,[19] and another Mele. Mele Tupou was a close relative of the king, who attended the baptism. President McBride and Elder Winn visited the king on July 18 and gave him some Church literature. The king sanctioned their work and invited them to visit him at any time.[20]

On his way down from Vava‘u, President McBride had asked Elder C. C. Wiser to stop off at Ha‘apai in July to investigate “establishing the work.” Wiser did not feel welcomed and continued on to Nuku‘alofa a month later. He apparently did not encounter any of the members who had been baptized in Ha‘apai in the 1890s.

By September 1911 the work had expanded to Nukunuku, where Elder Wiser performed two baptisms on August 15. He started a school and a branch there at Kitione Maile’s house. In September the elders visited Mu‘a and Houma, where seventy attended a cottage meeting at Chief Holafonu’s house. A few Tongan members reportedly attended the Samoan Mission conference held at Sauniatu, Samoa, in October.[21] On his final trip to Tonga in October, President McBride reported that he had visited all four branches on Tongatapu—Nuku‘alofa, Fo‘ui, Nukunuku, and Mu‘a—and that the mission had three flourishing schools at Ma‘ufanga, Fo‘ui, and Nukunuku.[22] In December McBride was replaced as mission president in Samoa by Christian Jensen.

Tupou Moheofo. Courtesy of Viliami Toluta‘u.

Tupou Moheofo. Courtesy of Viliami Toluta‘u.

It appears that by this time the mission presidents in Samoa had established the practice of visiting the Tongan Conference, or district, about every six months. Yet for most of the year the elders in Tonga were basically on their own, four hundred miles from their mission headquarters. This placed a great deal of responsibility on the missionaries to keep on task. Added to this responsibility was the fact that many of them lived alone in the village where they taught school and presided over the branch. In addition, only a few native Tongans had received the priesthood, so the elders were required to carry a much heavier load along with learning the language and the customs.

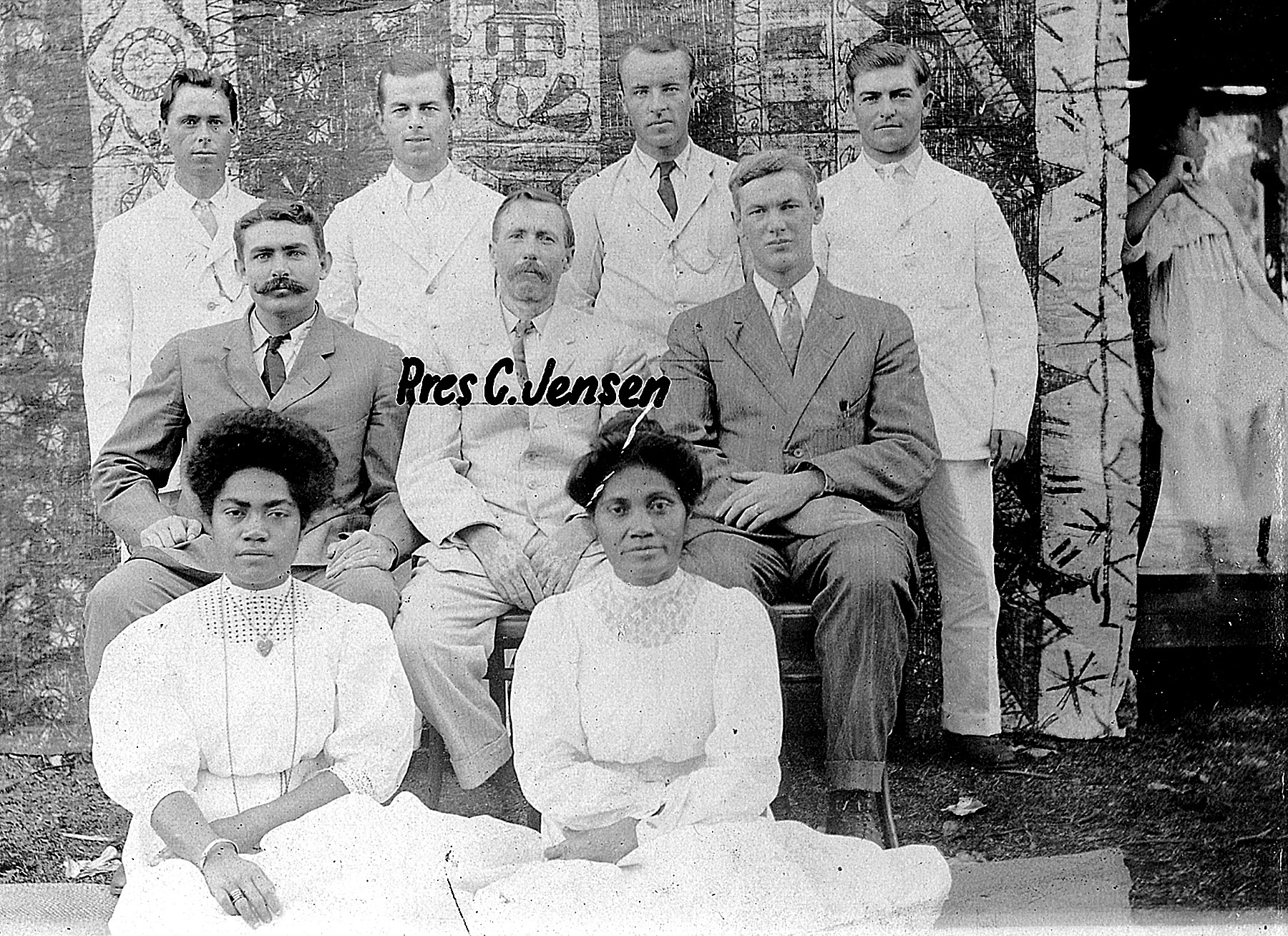

When President Jensen arrived in Vava‘u on his first visit in 1912, he found seven elders laboring there. At Ha‘alaufuli he discovered the branch was building a fine wooden chapel under the direction of Elder Joseph Spiker, who was the lead carpenter and foreman, and President Jensen donated two hundred dollars toward its construction. At Fo‘ui, on Tongatapu, the president learned that the school there was being taught by the two Samoan missionary sisters. The sisters put on a katoanga (program and feast) for two hundred family members of the students, which President Jensen found very impressive. At a district conference there he set Malia Joseph apart as Relief Society president and Lillie Joseph as Primary president. The school at Nukunuku, taught by Elder Wiser, had thirty-five students. They put on a school concert and another katoanga. The nobleman over the village, Tu‘ivakano, attended and was surprised at the school’s progress. At Ma‘ufanga the elders told President Jensen they had been discouraged because they didn’t feel they had much support from the mission president but that President Jensen’s visit had alleviated that concern.[23]

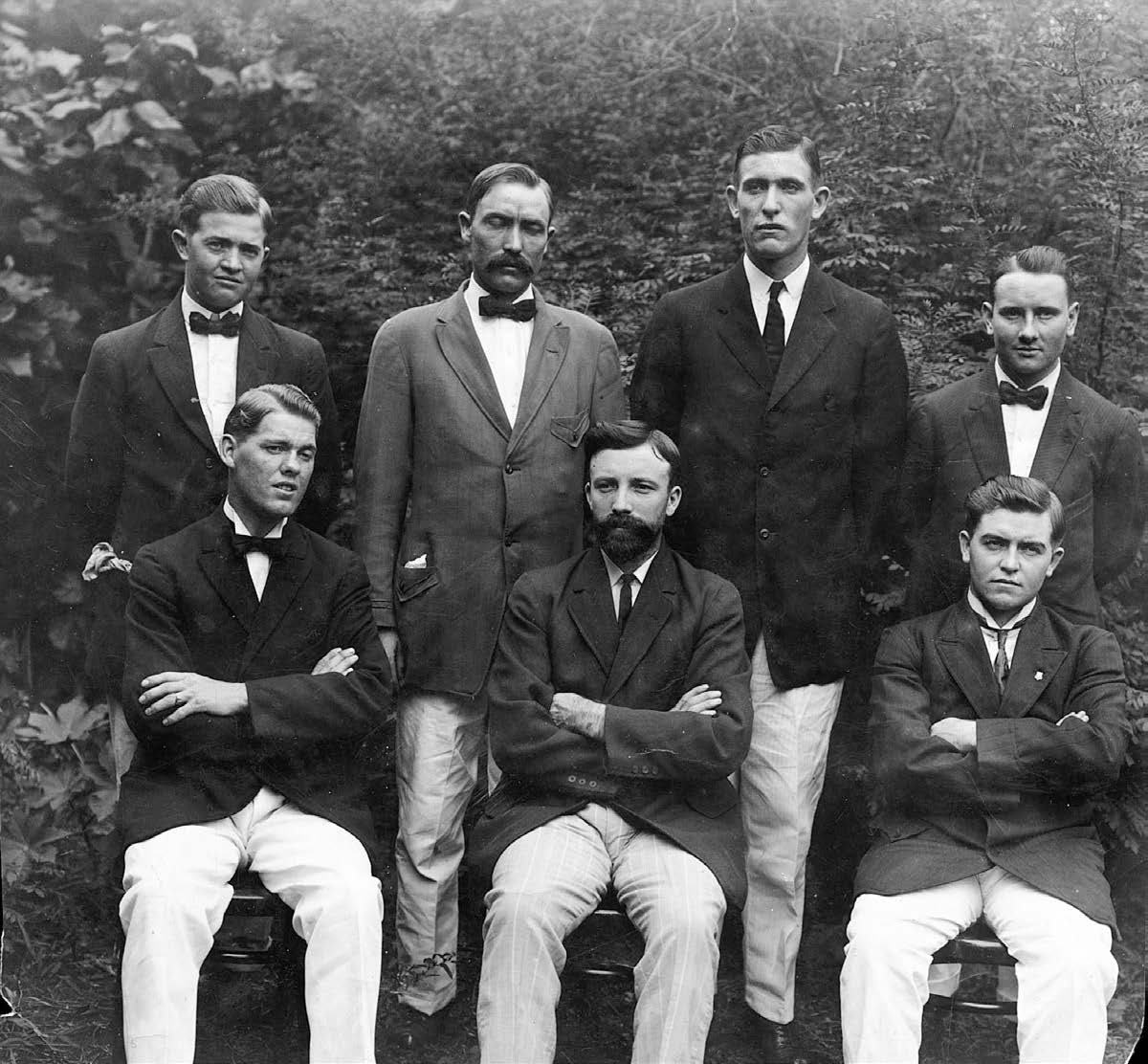

Samoan Mission president Christian Jensen and missionaries at Vava‘u. Courtesy of Carl Harris.

Samoan Mission president Christian Jensen and missionaries at Vava‘u. Courtesy of Carl Harris.

Returning to Vava‘u, President Jensen held a conference at Ha‘alaufuli on July 12–13, 1912. The new meetinghouse was filled to overflowing. He performed the dedication in Samoan since he didn’t know Tongan; it was the first Latter-day Saint meetinghouse dedicated in Tonga. A baptismal service was also held that day for twenty-one new converts. President Jensen learned that a few of the Vava‘u missionaries were guilty of some serious sins and had lost their influence among the people. One was sent home dishonorably, and another was transferred to a different island, evidence that perhaps they did need better supervision.

On Tongatapu, people in Mu‘a had been asking for a school, so on November 4 one was opened with an enrollment of sixteen students; the next day, thirty-one showed up. By March 4, 1913, it was hard to hold school because there were so many people crowding in. At that time Tungī, the noble of Tatakamotonga, offered some land for a school building in Mu‘a. The noble Havea, the Tu‘i Ha‘ateiho, asked for an elder to come to Ha‘ateiho, live in his house, and start a school, but there just weren’t enough elders.[24]

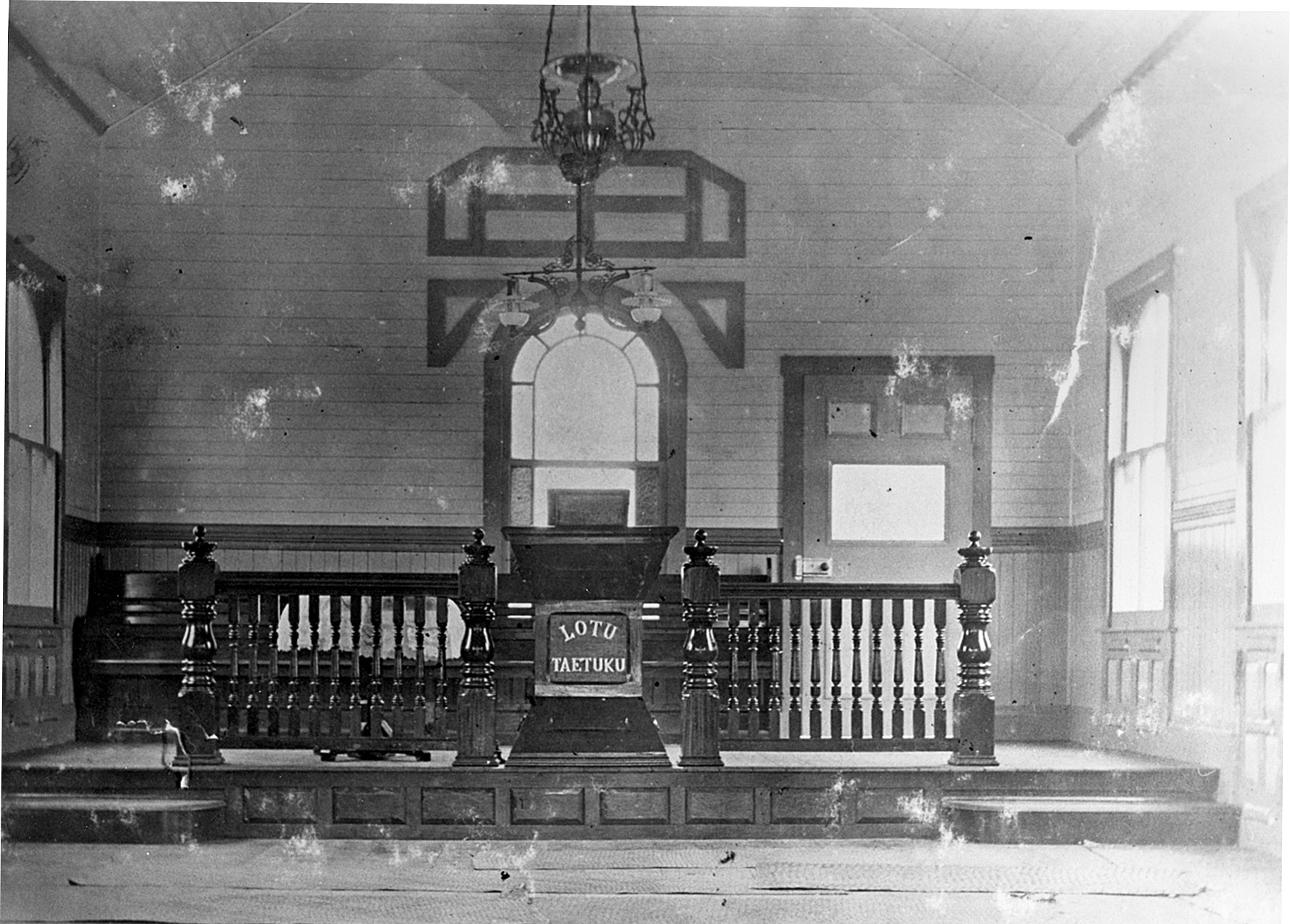

Ha‘alaufuli chapel. Courtesy of Carl Harris.

Ha‘alaufuli chapel. Courtesy of Carl Harris.

On his next visit, President Jensen went to Nukunuku and dedicated the new combination schoolhouse and chapel on December 28, again in Samoan. Tu‘ivakano, the premier of Tonga and noble of Nukunuku, was there and “thanked the Mormon Elders for what they had done and hoped they would stay.”[25] The conference at Nukunuku was attended by 128 Latter-day Saints and friends. President Jensen also brought some Samoan elders to labor on Tongatapu, Elders Upolasi, Walter Uaua, and Frank Aivao. Jensen was not feeling well, and when he returned to Samoa in early January he was replaced by President John A. Nelson.

Even though these missionaries did not have college degrees and were not experienced teachers, the government school inspector from New Zealand told Elder Evon Huntsman, who was teaching at Fo‘ui, “that our schools were the only ones trying to do the right things for the uplift of this people, he was well pleased.”[26] This seemed the opposite of what Reverend J. B. Watkins of the Free Church told Elder Winn: “It’s a waste of time to teach English to Tongans, keep them in ignorance.”[27]

Ha‘alaufuli chapel interior. Courtesy of Carl Harris.

Ha‘alaufuli chapel interior. Courtesy of Carl Harris.

The Latter-day Saint approach to education in Tonga was apparently different from the other churches. At least one of the missionaries during this time recorded in his journal that his lack of experience in the classroom was very discouraging.[28] They also noted that because of this lack of experience, keeping discipline in the classroom was a real challenge.[29] Sometimes, as soon as they got off the boat, they were assigned to a village to start or continue a school with little or no knowledge of the language and customs and little or no real teaching experience. That they succeeded as well as they did was a miracle in and of itself.

President Nelson made his first visit in June of 1913 and held a district conference at Fo‘ui, where he dedicated Tongatapu’s second combination schoolhouse and chapel. At this conference the students from the schools at Ma‘ufanga, Nukunuku, and Mu‘a put on a combined katoanga to show what they had learned. It was reported to him that each branch had an average attendance of twenty members, and sixty members would show up for district conference.[30]

Samoan Mission president John Nelson and missionaries in Tonga. Evon Huntsman collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Samoan Mission president John Nelson and missionaries in Tonga. Evon Huntsman collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

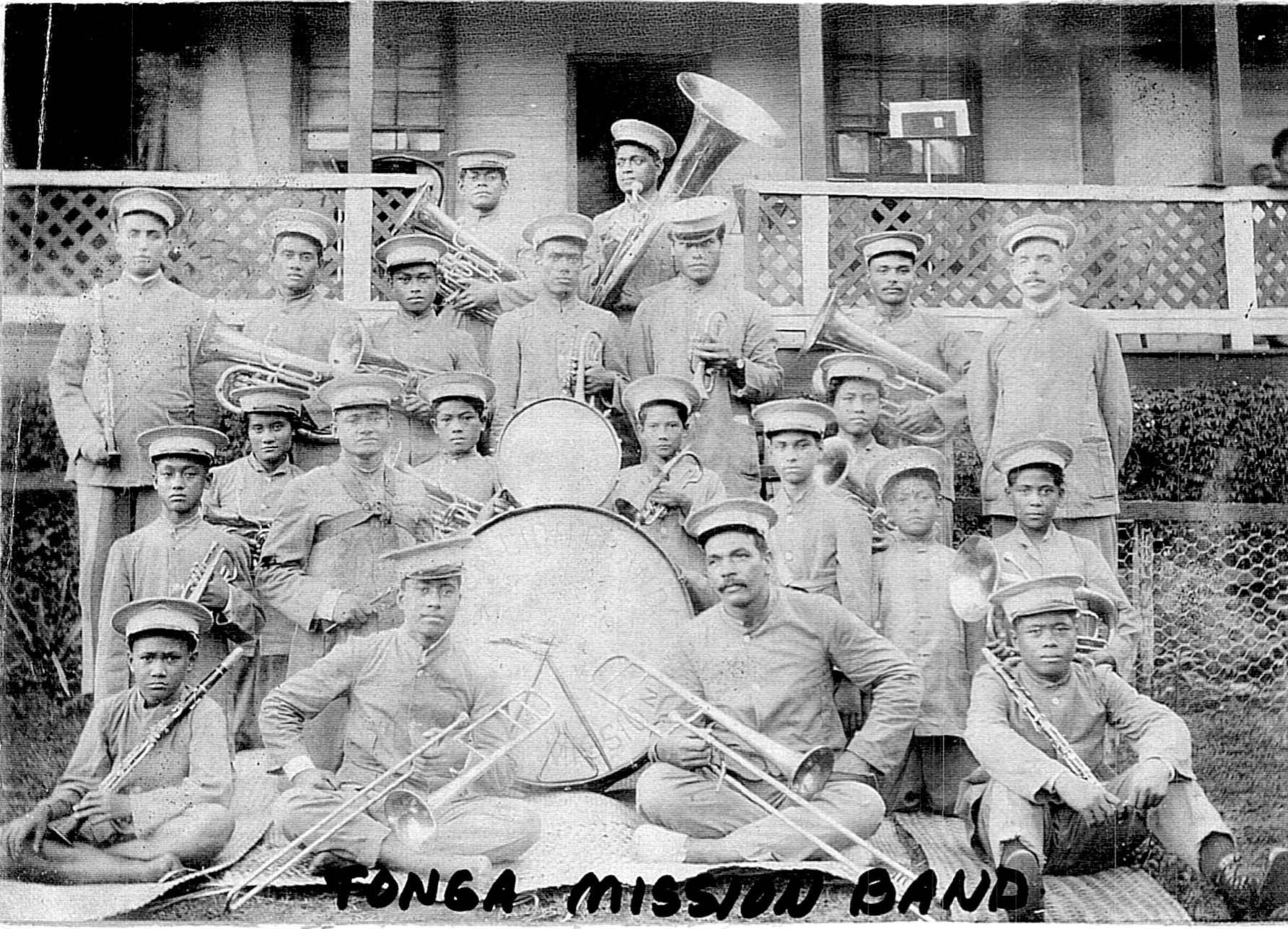

In the Samoan Mission, tours of the islands by the Latter-day Saint school bands were a great proselytizing tool. In addition to the musical performances, there were recitations by the students and speeches by the missionaries. On September 9, 1913, Elder M. Vernon Coombs, director of the Mapusaga School band on Tutuila, American Samoa, brought his band to the mission conference in Sauniatu on ‘Upolu. President Nelson asked Elder Coombs to prepare to take the Mapusaga band on a tour of the Tongan District. The band sailed for Nuku‘alofa with President Nelson about two months later. Their tour of Tonga was a great success. Another tour was planned for later in 1914, but it was canceled, probably because of the outbreak of World War I and the New Zealand takeover of Western Samoa from Germany.

President Nelson returned for his semiannual visit in early June, and at a conference on June 5 he bestowed the Aaronic Priesthood on Brother Maile of Nukunuku and Brother Metui of Fahefa, the first native priesthood holders on Tongatapu,[31] though some brethren in Vava‘u had already received the Aaronic Priesthood. He then went to Vava‘u two weeks later where Elder Huntsman noted that Ha‘alaufuli was the largest branch in the mission with eighty members.[32] At a district priesthood meeting held on July 3, he mentioned that there were fifteen native Aaronic Priesthood members present.[33] At this time the policy from Salt Lake was to delay advancing men to the priesthood until they had proven their devotion to the gospel over a period of time and to be temporarily lenient with them as they learned to follow the requirements of Church membership such as the Word of Wisdom, law of chastity, and law of tithing. While in Vava‘u, President Nelson visited with Governor William Tungī, “who offered all the support he could.”[34] Back on Tongatapu in August, district president Huntsman visited the noble Kalaniuvalu of Mu‘a, who said he was ready to assist the Church in any way he could when they decided to start building a new schoolhouse in Mu‘a.[35]

In 1915 President Nelson made his semiannual visits in January and June. In January he held conferences in Vava‘u and Tongatapu and noted that Ha‘apai had asked for missionaries but that none were sent at the time. In July he found that the six elders on Tongatapu were quarantined with typhoid until late August, and he was not able to meet with them on that trip.

As can be seen, the few elders in Tonga were often on their own. Most of them were tremendously dedicated and motivated to stay true to their calling. Elder Huntsman described his mission in these terms:

I never had many outstanding experiences during my mission. I followed instructions, kept the Lord’s commandments the best I could, worked hard to learn the language and the gospel, loved the people and my work and was willing to share my happiness with all I met. Most of my mission, I labored alone as far as a companion was concerned. Many times, my only companion was the Lord. I lived and ate much of the time with native Saints and friends I could make.

We Elders would visit back and forth with each other in our Branches, as often as we could, without neglecting our work. At the end of each month, we would spend a few days, usually two days, attending Elder’s Priesthood and Report Meetings, writing our mail home and receiving our mail. We called this “boat day” as the boat came in about once a month and when we could, we liked to meet on “boat day,” as that was the biggest day of the month. As the Islands are very damp and it rains a lot, the roads and trails we had to travel from branch to branch and into Headquarters, were always quite muddy. We walked every place we went and oft times made friends and opened the heart of a convert, as we walked along and would talk with him, or sit on a fallen coconut tree and rest. They would always be kind enough to climb a tree and get me a cool nut to drink, even though we could not agree on our religious views.[36]

When Elder Huntsman left to return home in 1915, he took with him Siosaia Mataele’s son, Maile Mataele, who wanted to get more education in the United States. Maile got as far as Pago Pago but was not allowed to go any further because of the war, so he went to school at Sauniatu and Mapusaga before returning to Tonga in 1924, where he became president of the Nuku‘alofa Branch from 1931 to 1943.[37]

Tongan Mission Created

On February 21, 1916, President Edward J. Wood—who had been a missionary in Samoa from 1888 to 1892, had served as the Samoan Mission president from 1896 to 1899, and was then president of the Alberta Canada Stake—was sent to tour the Samoan Mission, including Tonga. In Tonga, President Wood found that the elders were “not working much,” and two elders had been disobedient and were being sent home. Tonga obviously needed better supervision. The Brethren in Salt Lake City had given him the prerogative to divide the Samoan Mission and create a separate Tongan Mission as he saw fit.

In interviewing missionaries in the Samoan Mission who could be called to preside over the new mission, President Wood spoke to Elder Willard L. Smith, who was in charge of the school at Mapusaga. When President Wood issued the call to preside, the Spirit confirmed to Smith that the call was from the Lord.[38] Elder Smith and his wife, Jennie, both from President Wood’s stake in Alberta, had been serving at the Mapusaga School since January 31, 1915, and had been in charge of the school since October 3. According to Smith’s journal he was set apart by President Wood at Mapusaga on March 26.[39] The Smiths were apparently set apart again a week later.[40] They went to Apia to wait for a boat, and there they received a letter from the First Presidency on April 28 confirming their call.

The Smiths were finally able to sail from Apia on May 9 and stopped at Vava‘u, where President Smith left his wife, Jennie, to teach at the school at Ha‘alaufuli. He continued on and arrived at Nuku‘alofa on May 13. He was met at Nuku‘alofa by Elders Charles B. Crabtree and Thomas E. Beattie, who had been alone on Tongatapu for two months. President Smith found that missionary work in Tonga was somewhat in disarray. There were only six elders in Tonga, and one had left the mission to go work in a store, and another had gone to New Zealand to join their army, hoping to fight in the Great War.[41] Elder Newel J. Cutler, who came with President Smith from Samoa, said, “The work has been down low on the account of bad Elders, but it is improving now.”[42] Though there is nothing recorded in the mission history, Jay A. Cahoon recalled years later that President Wood accompanied the Smiths to Nuku‘alofa and dedicated the Kingdom of Tonga for the preaching of the gospel.[43] President Smith set himself to work organizing the new Tongan Mission. With the arrival of Smith and others, there were ten missionaries in eleven branches and approximately 450 members in an island kingdom of 20,000 people.

President Smith found that the elders’ home in Ma‘ufanga was unsatisfactory and rented a nice new home from Usaia for ten dollars a month. Yet these facilities were not quite what he wanted for the mission home. Elder Beattie said he went with President Smith to try to locate a place to build a new mission headquarters. Sister Smith records, “As soon as we arrived in Tonga, Willard tried to get lands, but the Govt. officials refused, they were very bitter towards the Mormons, they had advised the chiefs and land holders not to sell to us or even rent.”[44] Individual chiefs who had contact with the elders were often tolerant, or even supportive, after seeing the good the elders were doing in their villages, but government policy, heavily influenced by the Protestant churches, led to a great lack of support.

In July 1916 President Smith was sent $350 to buy land for a chapel and school, but it took a couple of years to find a suitable place for the Church to lease. According to Ermel Morton, President Smith’s greatest concern was to get enough elders into the country to be able to share the gospel on all the major islands. He tried to educate the Brethren in Salt Lake City that even though there were only 20,000 people in Tonga, they were scattered about on dozens of islands.[45]

In establishing the new mission on a firm footing, President Smith was involved in numerous matters. For example, Elder Beattie reported a good attendance at both the Ma‘ufanga and Kolomotu‘a Branches in Nuku‘alofa. President Smith bought a horse and buggy from a Mr. Ramsey for $200 and a typewriter. He had Filipo, a Samoan elder, teach him Tongan, and because of his previous experience in Samoa, he could bear his testimony in Tongan after only two weeks. Elder Cutler, who had been distributing pamphlets all over Vava‘u, was assigned to labor in Ha‘akame on Tongatapu, where he had thirty-five students in his school.

Education, especially for the purpose of learning English, was a high priority for many Tongan families, and the mission’s schools became the primary proselytizing tool. President Smith sent Elder Crabtree out to Mu‘a, where he had sixty students attending by May 24. Two weeks later, he sailed up to Vava‘u, where his wife, Jennie, was teaching school at Ha‘alaufuli. She had become known as “Misi Lila”[46] and carried that name for the rest of her mission. The students from the missionaries’ schools at ‘Otea, Neiafu, and Leimatu‘a came to Ha‘alaufuli for their midyear examinations on June 30, and President Smith returned to Nuku‘alofa a week later, leaving his wife to continue teaching school at Ha‘alaufuli.

Martha Emilie Sanft Wolfgramm. Karen Adams collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Martha Emilie Sanft Wolfgramm. Karen Adams collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

While he was in Vava‘u, President Smith got to meet Jacob Olsen, who had been in Tonga for twenty-five years and had provided significant assistance to the missionaries. Later he met some of the Wolfgramm families—several brothers and cousins who had emigrated from Germany, married local women, and raised large families and were very successful with their copra plantations, stores, and other businesses. Martha, or Ma‘ata, the wife of successful merchant Fritz Wolfgramm, had become interested in the Church, yet Fritz was very bitter toward the Church and wouldn’t allow his wife to be baptized. While Fritz was at work, she would attend Relief Society and Sunday School, of which he disapproved. After two years Martha asked to get baptized. Fritz refused, but she was baptized anyway. Fritz brought in his minister who sprinkled Martha, thinking this would bring her back to Fritz’s church. That tactic proved unsuccessful. Because of World War I and the fact that Tonga was a protectorate of Great Britain, the Tongan government confiscated much of the property of these German nationals. This humbled the Wolfgramms, and they were more receptive to the gospel message and were willing to support their families’ activity in the Church. Several Wolfgramms even ended up getting baptized. President Willard Smith, known in Tonga as “Uiliata Samita,” felt that Ma‘ata Wolfgramm was worthy to go to the temple if she ever had the chance.[47]

By September 1916 a young couple named Winward arrived to teach at Ha‘alaufuli, which allowed Sister Smith and DeLoy, the Smiths’ son, to join President Smith in Nuku‘alofa. Elder Beattie said the elders on Tongatapu were happy to have a sister missionary around.[48]

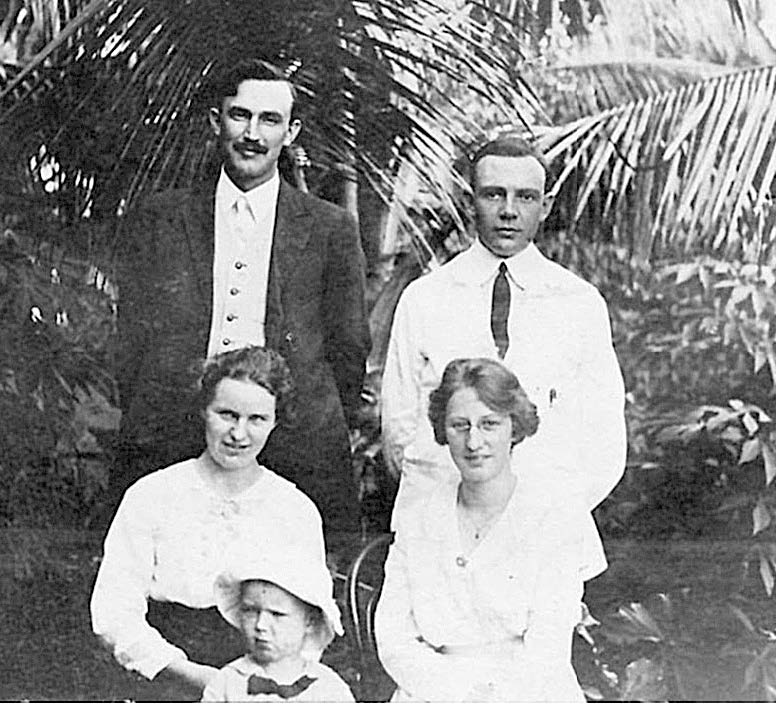

Front: Jennie Smith, DeLoy Smith, and Elsie Winward. Back: Willard L. Smith and Bryan Winward. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Front: Jennie Smith, DeLoy Smith, and Elsie Winward. Back: Willard L. Smith and Bryan Winward. Courtesy of Church History Library.

President Smith visited a Mr. Burns, the Tongan government school supervisor, on August 26, 1916. Mr. Burns offered President Smith his junior class outlines for the mission schools to use. Smith wanted to standardize the mission schools’ curriculum,[49] which he saw as a big help for the missionaries who were not trained and had never taught school before.

In some villages, the chief and community wanted a school more than they wanted the gospel, and sometimes the parents were not very supportive. This proved to be a challenge for the missionaries and even caused the mission to close a school from time to time; sometimes they then opened a school in another village. In 1916 President Smith decided to close the school in Ha‘akame because the parents were not supporting it. He also thought the school in Fo‘ui was at a standstill. It ended up being closed for a while, but the noble of Fo‘ui, Vaha‘i, later asked for it to be reinstated. So President Smith sent Elder Cutler to Ha‘ateiho to start a school there. When President Smith was at the mission headquarters in Ma‘ufanga, he usually helped out by teaching school in the mornings.

President Smith faced an interesting cultural challenge on December 31 when he learned that the Tongans believed their sins would go away at the end of the year and they would be able to get a fresh start each January 1. This was one Tongan tradition Smith worked to correct with some new converts.

Since Tonga now had its own mission, Church headquarters in Salt Lake City sent seven new elders there in early 1917. The work was moving forward. Sixty students were attending the school at Ma‘ufanga, and in Mu‘a the elders and Saints were busy building a combination schoolhouse and chapel, which was finished on March 23. During a visit to Vava‘u in April, President Smith decided to build a chapel in Neiafu. Construction started in July on land leased from Iki Tupou. It was called Maamafo‘ou, meaning “new light.” In September the mission bought a house for meetings in Ha‘ateiho for £12 and moved it to a lot that the Church leased. President Smith queried the First Presidency about ordaining Tongan men. The First Presidency wrote him to say,

There could be no objection to your ordaining native brethren to the Priesthood, provided that they are worthy to bear this responsibility. But great care should be taken by you in a matter of this kind, because of the tendency among our Polynesian brethren to become self-sufficient and to manifest insubordination when clothed with the authority of the Priesthood, and we suggest therefore that none be ordained except men of age and experience, known for their long years of faithfulness in the Church, and when convinced of the worthiness of such brethren from your own personal acquaintance with them, you may feel at liberty to bestow the Priesthood upon them.[50]

The wisdom of this counsel was borne out in later years. Naeata, son of Palemo, was the first Tongan to be ordained to the Melchizedek Priesthood in 1917.

President Smith was also instructed to encourage genealogical work. The Brethren wrote, “In reference to doing work for the dead, . . . nearly all of the Missions have been instructed to ascertain the names and genealogies as far as possible of every faithful member of the Church who has died in their several Missions without friends or relatives in Zion to do their temple work, and to send the names of all such persons to the St. George Temple.”[51]

Mission Restrictions

President Smith received unwelcome news from the First Presidency on September 1 indicating that Great Britain, who handled all of Tonga’s foreign affairs, would not be issuing any more visas to Latter-day Saint missionaries applying to come into Tonga. The letter read:

You mention that you need some experienced missionaries. . . . The British Government has recently ruled that they will not permit the entrance of missionaries into their possessions. They have instructed their ambassador and consuls in the United States not to issue visa passports. . . . So until this ruling is rescinded by the British Government, it will be impossible to send any Elders to New Zealand, Australia, Samoa, Tonga, or South Africa. We have not had any missionaries going to Europe since the beginning of the year. So your mission has been more fortunate, as far as receiving Elders is concerned, than most of the foreign missions.[52]

There were at the time considerable negative feelings among certain segments of the British public who believed Latter-day Saint missionaries in Great Britain were enticing girls to immigrate to America to become plural wives. The elders in Tonga had never preached polygamy or encouraged Tongans to immigrate to America. While this ruling was in force, it was suggested that missionaries already in the field be asked if they would be willing to extend their mission. A letter on December 16, 1916, reiterated that they could stay as long as their services were needed. Ermel Morton noted:

Correspondence between the office of the First Presidency and the Tongan Mission from 1919 to 1921 indicates that every avenue was explored in an attempt to get missionaries into Tonga, first through New Zealand and Figi [sic], and later through American Samoa. The Tongan Government was willing to permit missionaries to come but difficulties were encountered in obtaining permission from Great Britain. The Samoan route proved successful for two Elders in 1921, and this became the route followed by seven other Elders in the ensuing months. Missionaries coming this way were often delayed in Samoa making boat connections, but much red tape was avoided.[53]

Administering to the King

In 1917 a tremendous opportunity was presented to the elders, who were sometimes called on to provide some medical advice and perform a little doctoring. For some time they had visited in Nuku‘alofa with a chief they called Jack. Jack had been afflicted with bad sores on his leg and had been unable to walk without a cane for years. He asked the elders to administer to him. He was healed and threw away his canes. In mid-July, Elder Charles J. Langston wrote that he administered to Siake “Jack,” the governor of Ha‘apai, who said he would get baptized when they opened up the work in Ha‘apai. Thereafter, Elder Langston and others doctored Siake nearly every day until he returned to Ha‘apai.[54]

Not long after Jack was healed, a conference of all the high chiefs in Tonga was held with the king, George Tupou II. King George, a relative of Jack’s, suffered from consumption, now called tuberculosis, and had not been well for some time. When Jack told him of his administration and healing, the king was very much impressed and decided he would ask for this administration with consecrated oil.

On October 3, 1917, the king sent a messenger, a Brother Unga from Mu‘a, to ask President Smith to come to the palace the next day. On Friday, October 5, President Smith and his wife, Jennie, along with Elder Cutler, went to the palace and met with the king and his family. The king told of Jack’s report and of his desire to be administered to.

He had asked us to call on him, having heard of our work in healing the sick. He asked if it was true. I bore my testimony to him and we talked nearly an hour. . . . He said he would do anything that we asked him. I told him and his wife to fast with us and that Sunday afternoon at 4pm we would administer to him. He seemed overjoyed. I feel this is an answer to my prayers, also the fulfillment of the blessing I received when I was set apart as Mission President. Also, two months ago I was felt to say in Priesthood Meeting that I would preach the Gospel to the King and even administer to him. This is a testimony to me. We then visited Jack.[55]

Elder Cutler added this note: “Bro. Smith and myself went up the King’s place on his request. We had the privilege to preach the Gospel to him. He asked us to administer to him for his sickness.”[56] Elder Langston recalled that President Smith and Elder Cutler explained their work to the king and answered his questions, and the king asked to be administered to.[57]

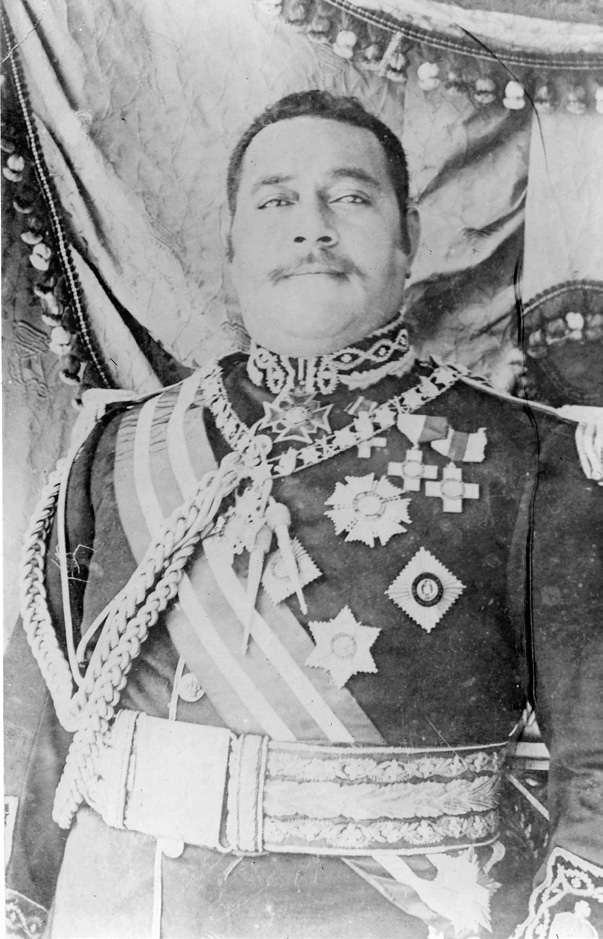

His Majesty King Siaosi Taufa‘ahau Tupou II. Clarence Henderson collection courtesy of

His Majesty King Siaosi Taufa‘ahau Tupou II. Clarence Henderson collection courtesy of

Lorraine Morton Ashton.

That Sunday they went to the palace and were received very warmly. They held a meeting with Elder Cutler speaking Tongan and President Smith speaking English. President Smith recorded on October 7, “We are fasting especially for the King as he asked of us. At 4pm Elder Cutler, Langston, Misi Lila [Jennie Smith] and I went to the palace. We met the Queen and King there. I took charge of the service. Opened by singing ‘Fakamalo kia Sihova.’ I opened with prayer then spoke a few minutes, asked the King if he was willing to leave off his other medicines. He said he would. He did not fast but the Queen and others had. Elder Cutler annointed and I sealed.”[58]

Misi Lila added, “It was fast day and we all kept it in behalf of the King. . . . Elders Cutler, Langston, Willard, and I went to the King’s. We were received kindly into his palace where Willard explained the gospel to him; the necessity of laying hands on him. He promised to do whatever the Elders asked him. They then administered to him.”[59] According to Jennie Smith, in the sealing President Smith told the king that he would get well and would testify that he felt like a young man. Elder Langston recorded that they “explained the ordinance of administration on him and requested that he leave off his other doctoring. He said he would. We then administered to him. Bro. Cutler did the anointing & Bro. Smith was mouth in sealing it.”[60]

The next day the king and queen went out to the mission home in Ma‘ufanga looking for President Smith, something they had never done before because Ma‘ufanga was a strong Catholic village. President Smith’s journal says, “The King came down in the afternoon and stopped in front of our house. I went to see him. He seemed very pleased and said that he felt very much better. I have been greatly worried over this matter but feel that our prayers have been answered.” The king told President Smith his “palace was open at any time for any of us.”[61]

President Smith and Elder Cutler visited the king on October 11. “In the afternoon Elder Cutler and I again visited the King. He was very much improved. The doctor came while we were there and said he was much improved. He was well pleased with our visit.”[62] Then President Smith, following the promptings of the Spirit on October 17, said, “I did not go to Mu‘a as I had planned but felt it best to stay and call on the King, Elder Cutler going with me. I felt when I went in the room that our visit was going to be an important one. . . . It appeared so, the King was much improved in health and very pleased to see us. He asked that I call Friday and explain him the Gospel and said he would give me a letter stating that any person who desired to give over his land for our work would meet with hearty approval.”[63]

They returned again on October 19: “Arose early, fasted. . . . Went to King’s, spent one and a half hours explaining the Gospel to him. Covered briefly Apostacy, Restoration, and Bk of Mormon. He wrote down all references.”[64] Elder Langston recalled that on this occasion he, President Smith, Elders Ira Jensen, and Newel Cutler “visited the King to explain the gospel to them.”[65]

The next day President Smith was out of town on business: “At Five this afternoon the King again sent for us. Elder Cutler and Misi Lila went up. He asked to be administered to again Monday.”[66] Misi Lila records, “The King sent for Elder Cutler. I packed suitcases to go to Vava‘u then went with Elder Cutler to the King’s palace. He asked that we administer to him again. Elder C. told him Willard had gone to Mu‘a but that we would fast for him and perform the ordinance Monday 10am. He seemed very pleased.”[67] President Smith described his visit:

The King had asked that I visit him as he wanted to be administered to. We Elders called on him at 10 o’clock. He was at the Consul’s but the Queen was there and we had a nice visit with her. She said the King was much improved. The first day (Friday) that I visited him his health was poor, appetite bad, but in our talk he asked to be administered to, . . . but Saturday he began to improve; his appetite improved and Sunday after the administration he was much improved. This is what the Queen told. The King came, surely gave us a hearty welcome, excused himself for being late. He explained his desire as he was leaving [to Vava‘u] he wanted to be administered to again. Elder Langston anointed him. I sealed the anointing. I promised him his sickness would leave him this day. He should regain his health as a young man but if he hindered the work his sickness would return. This is a great testimony to me of the power of the Priesthood; the Lord is striving with this people.[68]

Of this visit Elder Langston, who died of the Spanish influenza and was buried in Nuku‘alofa the following year, added, “Pres. Smith, Cutler, Jensen, Larsen and myself all went to administer to the King again. I did the anointing and Pres. Smith the sealing. He is sure getting better and feeling fine toward us.”[69]

Since he had arrived in Tonga, President Smith had tried to get land for a new mission home, chapel, and school. The government officials had always refused and had been very bitter toward the Latter-day Saints. They had advised the chiefs and landholders not to sell to the elders or to even rent. When they heard about the king being administered to by the elders, the chiefs and ministers advised him to disengage from contact with the Church.

It seems that government officials who were antagonistic toward the Church had advised the king to reconsider his relationship with the Church. However, through his experience of blessing the king and explaining gospel principles to him President Smith was finally able to get permission to buy the lease on a property that Tevita Tuliakiono had told him about previously in Kolomotu‘a, which they called Matavaimo‘ui, or “place of living waters.”

On April 5, 1918, the king died suddenly. The day after King Tupou II’s death, he was succeeded as monarch by his daughter, eighteen-year-old Queen Salote Tupou III. She had just been married a few months before on September 19, 1917, to Prince Viliami Tungī Mailefihi, thirteen years her senior, who, as a young boy, had attended the little missionary school in 1894 at Hilatali in Mu‘a to learn English. The accession of Salote was not without challenges and intrigue since there were other claimants to the throne who thought their genealogies were at least as strong as Salote’s and had powerful backers. For a period of time it was apparently unsafe for her to leave the palace.[70] As a young and inexperienced monarch, she relied heavily on her older and more experienced husband and consort, who wanted to shield her from the unpleasantries that came with politics.[71]

After his visits with the king in 1917, President Smith also went to Vava‘u, where he held the first meetings in the new Maamafo‘ou chapel on October 28. The building was twenty-four by sixty feet and divided into the elders’ quarters at one end and a combination chapel and schoolhouse on the other. It had a wood frame with a painted tin roof and was well maintained. He also followed up on the Ha‘apai governor’s request and called Elders Newel Cutler and Kenneth Rallison to establish the Church in Ha‘apai.

Reopening Ha‘apai

Her Majesty Queen Salote Tupou

Her Majesty Queen Salote Tupou

III and Prince Viliami Tungī

Mailefihi. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

When the elders arrived in Ha‘apai, they met the governor, Siake “Jack” Lolohea. He helped them find a house large enough for living and schooling purposes that they rented for thirty shillings a month. Two days after arriving, Elders Cutler and Rallison held their first meeting in Ha‘apai with one hundred present. The next day the elders established a day school with twenty-five students and were taking their meals at “Jack’s place.” The elders would stay and answer Jack’s questions about the gospel two or three times a week. By December 10 the enrollment had increased to sixty-five, and a Sunday School was initiated.

The elders’ success continued in Ha‘apai. The elders were able to preach to the mayor of Pangai and the governor of Ha‘apai. When school started again on March 25, 1918, 108 students were enrolled. They also had success on the island of ‘Uiha, where they baptized Leleimoepo, the chief of Felemea. When President Smith came for the first conference of the Ha‘apai District, held May 18–20, they performed twenty-six baptisms, then seven more the next week. Siake Lolohea nearly got baptized; he even took off his vala (wraparound skirt) in preparation for baptism then put it back on and watched his son get baptized. Sister Smith said, “He preached Mormonism wherever he went night and day but on the day President Smith was performing baptisms Jack went back and forth to the water’s edge several times, but he lacked the courage to go in, he knew he would be ridiculed and perhaps lose some prestige among the other chiefs. Although he didn’t get baptized, he always preached Mormonism wherever he went.”[72]

In Nuku‘alofa the elders marked off the land in Kolomotu‘a for the new mission home that had been leased from Koli Moa for fifty dollars a year. Elder H. J. Jacobs came down from Vava‘u to help with construction. Most of the elders were called away from teaching and proselytizing to work on the new mission home. When the king died, all work on the mission home in Kolomotu‘a ceased. After the funeral they had continued moving the schoolhouse from Ma‘ufanga to Matavaimo‘ui, but when they passed by the palace they were criticized for disturbing the peace and working during the mourning period. The mission school at Matavaimo‘ui commenced on March 10 with twenty students. The first services in the new mission home were held on April 7. The midyear examinations for the school were held on July 4, and Elder Langston recorded, “I could have hugged them all they were so good.”[73]

On Vava‘u, Elder Sterling Ibey May started a school band at Maamafo‘ou. Within three weeks Sister Smith said they were playing very well. Elder Langston wrote, “The band is sure a wonder for the time they have been together.” The band had only ten instruments, and they played at the Neiafu wharf for ship arrivals and departures. Elder May said the elders in Vava‘u got most of their converts through the school.

Maamafo‘ou band.

Maamafo‘ou band.

In 1918 the mission had twenty-one missionaries from Zion, the most ever. When the mission president asked for more elders, Salt Lake reminded him that Tonga had more per capita than any other mission. Yet the Brethren understood that more missionaries than normal were needed because the people were scattered among the many islands.

At that time the Saints throughout the mission were making handicrafts and soap out of coconut oil to sell at the upcoming mission-wide conference in order to raise money to help with the construction of the temple in Hawai‘i. Even though they had no hope of ever getting to a temple, it was a me‘a ‘ofa (love offering). Elder Cutler carried this hundred-dollar me‘a ‘ofa to Hawai‘i on his way home in 1919.

The Influenza Epidemic

Near the end of 1918 a boat from Vava‘u carrying the Maamafo‘ou band and many Saints arrived on November 12 for the first mission-wide conference in Nuku‘alofa. The chief judge in Vava‘u, a palangi named Wallace, had tried to prevent the Saints from Vava‘u from coming by bribing the boat’s captain with whiskey. What the passengers on the boat did not know was that they also brought with them the Spanish influenza virus. By November 16 most of the people at the conference were sick. Scores of people died each day. They were buried in mass graves because there were not enough people to properly bury them. Half-drunk sailors from a visiting American ship were hired to help bury the dead.

Elder Charles J. Langston succumbed on November 26 and was buried in Telekava Cemetery across from the Matavaimo‘ui chapel. Visiting from Vava‘u, Brother Jacob “Sekope” Olsen lost all his family except his daughter-in-law. Yet in Vava‘u not a single young Latter-day Saint person passed away. Elder Jacobs in Vava‘u was inspired to stay behind and was the only person in Vava‘u with the priesthood. He went from house to house administering to the sick. His service made many friends for the Church. An estimated 1,800 perished out of a population of just over twenty thousand. Misi Lila (Sister Jennie Smith) noted, however, that the pandemic caused the natives and Europeans to treat the Church better; they seemed humbler.[74] Even with the influenza pandemic, the mission-wide conference of November 1918 showed that the Church had become a permanent fixture on the Tongan landscape, and the work moved forward.

Events after the Pandemic

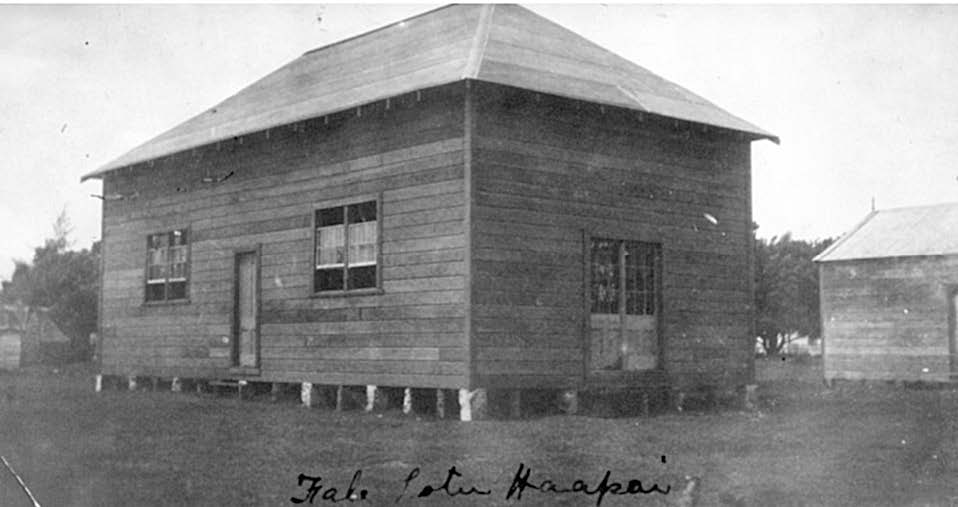

Ha‘apai chapel. Courtesy of Viliami Toluta‘u.

Ha‘apai chapel. Courtesy of Viliami Toluta‘u.

In Ha‘apai the Church continued growing. The members began working on a nice forty-by-twenty-by-fourteen-foot meetinghouse. It cost $1,300 and was paid for by the members. At this time Ha‘apai was the most productive area of the mission. The first services were held in the new chapel on March 23, 1919. Afterward, Elder Newel J. Cutler was finally released; he had served five years and five months because no one had been able to replace him because of Great Britain’s embargo on missionary visas.

The Church’s schools in Tonga were only primary schools, and the opportunity for further education was practically nonexistent. In New Zealand the Church had established the Māori Agricultural College in 1913 near Hastings in Hawkes Bay. It was a secondary boys’ boarding school that focused on agriculture and the manual arts. The mission president in New Zealand had invited the mission presidents in Tonga, Samoa, and Tahiti to send prospective students to attend. The first four Tongan boys, Samuela Fakatou, Manase Mailangi, Sione Filipe, and Misitana Vea, sailed for New Zealand on July 1, 1919. A month later President Smith received a letter from the college’s principal, John S. Welch, saying:

We registered Manase in the Sixth Standard and the other three in the Third Standard. They are all carrying their work in a very satisfactory manner and I can assure you we are glad to have them here. They are certainly well behaved and I am sure they will get along very nicely. I wish to congratulate you on the type of boys that you have sent. We are wondering whether this is a fair representation of all Tongan boys or whether these have been chosen for special merit. In quite a number of respects, they can set an example to the average Maori boy.[75]

These boys would later return and greatly bless Tonga.

At the same time, the Church’s schools in Nuku‘alofa were centered at Matavaimo‘ui. Native dorms were built that housed twelve boys and nine girls. There was a shortage of elders at this time, which President Smith had predicted in 1917, so Misi Lila sometimes ran the meetings at Matavaimo‘ui. She also started teaching school when it opened at Matavaimo‘ui on March 10, 1918, with twenty students. She later recalled that Tongan parents wanted their kids to attend the Latter-day Saint schools, and they were a great missionary tool.[76]

Following the end of World War I, Tonga held a world peace day on August 2, 1919. Latter-day Saint students from Matavaimo‘ui represented the United States. Matavaimo‘ui was judged the best school, and the students received many compliments. The Catholics and Protestants were unhappy with this decision and boycotted some events of the day.

In 1919 sentiments against the Church seemed to increase. At the mission conference in Pangai, Ha‘apai, held October 25–27, some schoolgirls were attacked and beaten. President Smith had the conference visitors’ sleeping quarters guarded by men with pistols and knives. On the way back to Tongatapu, they stopped at Nomuka overnight, and Sister Smith had to guard the door of the girls’ sleeping quarters. However, at the Vava‘u District conference held in early December, there were fifty-three convert baptisms.

By the beginning of 1920, it was becoming apparent that President Smith’s struggle with asthma was becoming too much for him—even after several mission-wide fasts and priesthood administrations. He received his letter of release on February 20 and was sad at the thought of leaving the Saints in Tonga after five years in the mission field and four as the first president of the Tongan Mission. His name throughout Tonga was “Misi Uiliata Samita.” He would later return to the Pacific as president of the Samoan Mission from 1927 to 1934. Willard and Jennie Smith would spend a total of thirteen years serving in the Pacific.

Benefits of Holding Conferences

The missionaries from North America introduced the program of the Church including the holding of regular branch, district, and mission-wide conferences. The Tongan Saints enthusiastically adopted these conferences as part of their worship. These conferences provided gospel instruction, sharing of testimonies, and opportunities for socializing. The district conferences were supposed to be held quarterly, and the annual mission conference usually lasted two or three days with two or three sessions each day. The auxiliaries each held their own session along with genealogical meetings and missionary training and reporting.

Socializing was an integral part of each conference. There were usually choir and dance competitions between the branches and districts. Along with oratory, composing music, conducting choirs, and choreographing native dances such as lakalaka and ma‘ulu‘ulu were highly admired skills.

Feasting was the foundation of each conference. Individual Tongans, families, and villages measured their material wealth and were admired not for what they had but by what they could share. Good hospitality is a core Tongan value. Conference feasts brought out the best the Saints could provide. Obviously, conferences were a great place for missionaries to bring investigators to hear the gospel and meet the members.

Notes

[1] The authors wish to thank Viliami Toluta‘u for sharing this analogy.

[2] Ermel J. Morton, 20th-Century Western and Mormon Americana, Perry Special Collections, 7–9 (hereafter cited as Morton notes).

[3] MHHR, April 11, 1907.

[4] MHHR, April 11, 1907.

[5] MHHR, April 13, 1907.

[6] Thomas S. Court letter to Zion’s Samoan Association, December 18, 1907, in possession of the authors.

[7] MHHR, January 13, 1908.

[8] This was actually high chief Kalauta’s home where the king stayed whenever he was in Vava‘u.

[9] MHHR, June 30, 1908.

[10] William Alfred Moody, Years in the Sheaf (Salt Lake City: Granite, 1959), 159–61.

[11] MHHR, August 24, 1908.

[12] Eric B. Shumway thinks one of the men was Se Saulala.

[13] William Orvil Facer history (manuscript, summer 1908), in possession of the authors.

[14] Facer history, 20–21.

[15] Journal of Mark Vernon Coombs, 1973, 10, typescript in possession of authors.

[16] MHHR, May 29, 1910.

[17] For more on the Germans in Tonga, see Kasia Renae Cook, “Sauerkraut and Salt Water: The German-Tongan Diaspora Since 1932” (PhD diss., University of Auckland, 2017), and Cook, “Germans in Tonga: A Look at Racial Integration and Relations in the Late-Nineteenth and Early-Twentieth Century” (BA honors thesis, Brigham Young University, 2011).

[18] Bernell W. Meacham et al., comps., “Faith Was Their Legacy: Biographies of William Frank and Lavon Cragun Winn,” typescript, 1994, in possession of the authors.

[19] Mele Tupou Moheofo was the granddaughter of King George I through his son ‘Isileli Tupou. She is the direct ancestor of both King Tupou VI and Queen Nanasipau‘u through different lines.

[20] Don Carlos McBride, Samoan Mission Journals, CHL.

[21] MHHR, October 27, 1911.

[22] Don Carlos McBride, “Excerpts from the Missionary Journal of Don Carlos McBride,” October 27, 1911, typescript in possession of the authors.

[23] Christian Jensen journal, June 20, 1912.

[24] William Frank Winn, “Faith Was Their Legacy,” typescript, February 20, 1913, 63, in possession of the authors.

[25] Jensen journal, December 29, 1912.

[26] Evon Huntsman journals, January 23, 1913, in possession of the authors.

[27] Winn, “Faith Was Their Legacy,” August 27, 1913, 76.

[28] Winn, “Faith Was Their Legacy,” February 13, 1913, 67.

[29] Interview of Abiah W. Miller by Charles Ursenbach (1974), OH 191, CHL.

[30] Huntsman journals, June 15, 1913.

[31] Huntsman journals, June 6, 1914.

[32] Huntsman journals, June 26, 1914.

[33] Huntsman journals, July 3, 1914.

[34] Huntsman journals, July 16, 1914; see journal of John A. Nelson for this same date, CHL.

[35] Huntsman journals, August 21, 1914.

[36] Evon Wesley Huntsman, “My Story Lest I Forget,” http://

[37] Siosaia Maile Lafokeimalu Mataele, interviewed by R. Lanier Britsch, 1974, OH 313, CHL.

[38] Willard L. Smith journal, February 22, 1916.

[39] Smith journal, March 26, 1916.

[40] Smith journal, April 3, 1916.

[41] Jennie Hill Leavitt Smith, “A Short History of My Life,” Perry Special Collections.

[42] Newel J. Cutler record, June 30, 1916, in possession of the authors.

[43] Cutler record, May 11, 1916. The dedication pronounced by Andrew Jenson on Mount Talau on September 9, 1895 was only for Vava‘u.

[44] Jennie Smith, “Short History of My Life,” Perry Special Collections.

[45] Morton notes.

[46] Misi meant “missionary” or “important white person.”

[47] Smith journal, December 4, 1919. Martha’s story was also shared by President David O. McKay during his visit to Vava‘u on January 13, 1955, and is recorded in the MHHR under that date.

[48] Thomas Beattie journal, October 28, 1916.

[49] Smith journal, August 26, 1916.

[50] Ermel Morton, Brief History of the Tongan Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Golden Jubilee (Suva: Fiji Times, 1968), 13.

[51] Morton, Brief History of the Tongan Mission, 13.

[52] Morton, Brief History of the Tongan Mission, 13.

[53] Morton notes.

[54] Charles J. Langston diary, July 16, 1917, in possession of the authors.

[55] Smith journal, October 5, 1917. Ian C. Campbell, Island Kingdom: Tonga, Ancient and Modern, 3rd ed. (Christchurch: Canterbury University Press, 2015), 138, thoughtfully observed, “Tupou II inherited a kingdom which had owed its stability only to the personal dominance of his great-grandfather [Tupou I]. His own personal qualities had not developed by the time he became king at the age of nineteen. He had been brought up indulgently, was a lavish spender and had not learned either the obligations or the skills of leadership.”

[56] Cutler record, October 5, 1917.

[57] Langston diary, October 5, 1917.

[58] Smith journal, October 7, 1917.

[59] Jennie Smith notebook.

[60] Langston diary, October 7, 1917.

[61] Smith journal, October 8, 1917.

[62] Smith journal, October 11, 1917.

[63] Smith journal, October 17, 1917.

[64] Smith journal, October 19, 1917.

[65] Langston diary, October 19, 1917.

[66] Smith journal, October 20, 1917.

[67] Jennie Smith notebook.

[68] Smith journal, October 22, 1917.

[69] Langston diary, October 22, 1917.

[70] See Campbell, Island Kingdom, 152–54.

[71] Concerning the state of the kingdom prior to and after the coronation of Salote, Campbell, Island Kingdom, 152, notes, “The kingdom which Salote inherited was neither united nor stable. . . . Few people, if any, expected Salote to play a dominant part in Tongan politics; not only was that not expected of women, but Salote was only eighteen years of age when her father died, and she had not been educated for leadership the way a son of Tupou might have been. These considerations were probably taken into account in choosing Tungi Mailefihi to be her husband in 1917. Tungi was a well-educated chief.” Therefore, it was always Prince Tungī who met with Latter-day Saint representatives. Perhaps not until Elder George Albert Smith’s visit in 1938 did Church leaders meet with Queen Salote.

[72] Jennie Smith notebook. See also Langston diary, May 27, 1918.

[73] Langston diary, November 12, 1918.

[74] Jennie Smith notebook, December 18, 1918.

[75] Smith journal, August 1, 1919.

[76] Jennie Smith notebook.