Planting Seeds with Little Harvest (1891-97)

Riley M. Moffat, Fred E. Woods, and Brent R. Anderson, "Planting Seeds with Little Harvest (1891-97)," in Saints of Tonga (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 9–52.

Opening Tongatapu

Latter-day Saint missionaries sailed into this sea of religious turmoil in 1891. They landed at Nuku‘alofa on the southern island group of Tongatapu. Their journals record vital details that might otherwise be lost. Such particulars include the initial meeting with the king of Tonga to seek permission to preach the gospel, their urgent need for housing, and their request to the premier of Tonga to build a mission home and school.

When they arrived at Nuku‘alofa on July 15, 1891, Smoot recorded, “What a pancake looking place it is, the highest elevation on the group being only about 200 feet above sea level. . . . The steamer pulled up to the wharf and we landed as the first L.D.S. Missionaries to Tonga. . . . Nobody was waiting with open arms to receive us.” Accommodations were also difficult to arrange. Smoot explained, “The natives are not allowed to take in foreigners and nobody knew of any private rooms to let so our only alternative seemed to be the only hotel in the place, which is anything but inviting.”[1] On August 4 they were able to rent rooms from Mr. Percival in a prime location downtown for ten dollars per month. It had a balcony that overlooked the main intersection of Nuku‘alofa.[2]

Meeting King Tupou I

At the time of their arrival, the city was also full of visitors from neighboring islands. Nobles and officials from all three island groups gathered for Tonga’s annual legislative assembly, and the two missionaries were fortunate to meet with King George Tupou I the following day. A local interpreter assisted the missionaries. After presenting the king with kava,[3] their congratulations, and a request to preach in his kingdom, Smoot wrote, “He answered with a pretty speach [sic] of welcome which quite encouraged us, wishing us success, thanking God for our safe arrival but added that he thought his people were all Christians. As he desired to know something about our faith, I had our man [the interpreter] read our ‘Articles of Faith,’ also refuted a number of false reports that Tonga is full of.”[4] Rumors from Europe, particularly Great Britain, and the United States were circulating around Tonga regarding Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, and the practice of polygamy, which spiked interest about the Latter-day Saints.[5]

After meeting King George, Elder Alva Butler—a young man from Butlerville, Utah—wrote, “This is the first time in my life I was before a king of a nation and we was there asking for permission to preach unto his people. He granted permission and we had the Articles of faith read to him. . . . He treated us well and shook hands with us when we left and wished us success in our work. He thought we were the same as Mohammedans.”[6] The confusion likely arose from similarities in the words Mamonga (Tongan for Mormon) and Muslim.

Their first cottage meeting was held at Pea on August 1. A village matapule (chief) allowed the elders to use his home, and a good crowd attended. They soon learned, however, that it was against the law to have a religious meeting in a village unless there were at least six adult members of that faith residing in that village. The fine could be up to fifty dollars.[7] According to Butler, when they became aware of the six-member law, the elders decided to hold their own services. Before their first service, a group of Samoans living in Tonga asked them to conduct the meeting in Samoan. That Sunday the Samoans were joined by forty Tongans.[8] From then on, the elders generally had a congregation to preach to, but none would commit to join the Church.

When Smoot and Butler met the premier of Tonga, Siaosi Tuku‘aho, along with other members of Parliament, just weeks after their arrival, the premier appeared to have great interest in the Latter-day Saints:

This has truly been an eventful day in my mission. There has not been an hour from 7:30 a.m. until 7 P.M., but what a number of Parliament members and high chiefs have been in to hear us talk. About 8:30 a.m. the house and yard were crowded and after speaking to them about an hour and bearing my testimony, the Catholics and Wesleyan ministers took sides and had a regular knock down argument, both claiming to be more like my explanation of the Bible than the other. It was really amusing.

Among our numberless or at least numerous callers during the day were no less personages [than] Tukuaho, the Premier of Tonga and Kubu the minister of police with a number of the highest chiefs in the kingdom. This was about 5 P.M. I gave them a piece of Kava and talked to them about 45 min. on the Gospel. They all seemed very pleased indeed, especially the Premier, who upon leaving said he wanted to talk to us again, thanking us at the same time for kindness shown him and associates and complimenting me on my knowledge of the Tongan language. . . . Mormonism is all the talk now in Tonga.[9]

The elders felt they were blessed with the gift of tongues as they shared the gospel with all their visitors. There were so many guests that sometimes it was practically standing room only in their apartment. The crowd included all the members of Parliament and all the island governors.[10]

Less than two weeks later, the elders went to hear the king of Tonga make a five-minute address to Parliament. Afterward, Smoot and Butler took advantage of the crowd and managed to get some of them to listen. Smoot wrote, “I was permitted to again bear my testimony to quite a number of the head men of the land, among the number being the Crown Prince’s father and the Minister of lands, both of whom seemed greatly pleased at the explanation of our principles.”[11]

However, soon thereafter the elders met stiff opposition. Smoot recalled, “Our fame very soon became widespread and we hear on every side, that least understood, yet worldwide despised name, Mamonga (Mormon) from the lips of most everybody we pass, generally accompanied by some sneering remark . . . from the lies of Christian ministers.” He added, “We are encouraged, however, . . . with the success we have had . . . with the King, . . . the Crown Prince, . . . the Premier and his private secretary.”[12] Forming friendships with these influential leaders would soon prove vital to finding permanent housing and mission headquarters.

A Mission Home in Mu‘a

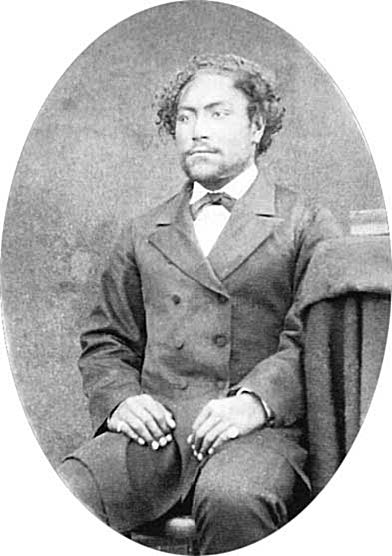

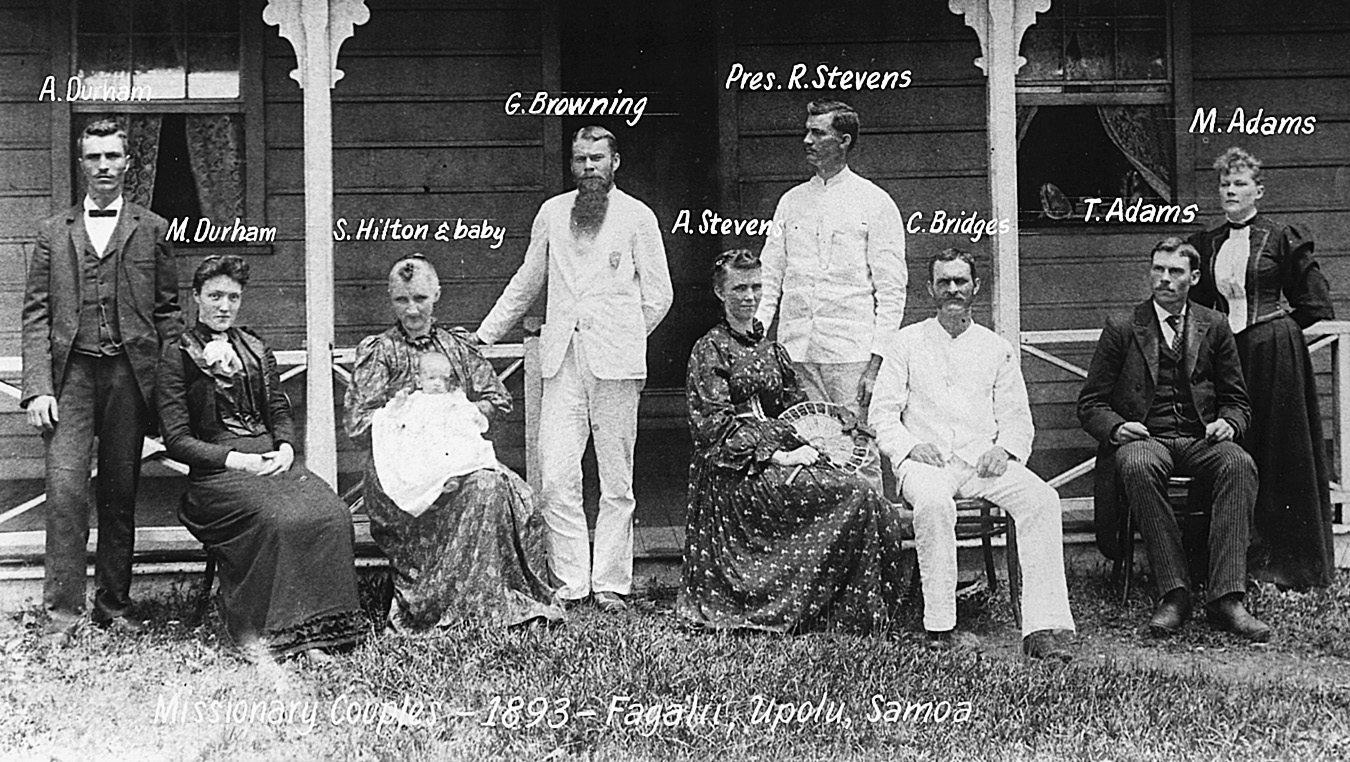

Prime Minister Saiosi Tuku‘aho.

Prime Minister Saiosi Tuku‘aho.

Wikimedia.

After months of searching for a place to lease, they were still unsuccessful. Tungī Halatuituia, the minister of lands, had originally given them approval to lease land, but ministers of the other churches who had strong influence in the government pressured him to rescind his approval. British consul Mr. Leefe wrote to the American consul in Samoa soliciting advice on what to do with the American missionaries. The American consul told Leefe to advise the government not to interfere with the missionaries. Notwithstanding, the landholders still refused.[13] They were repeatedly turned down by Tungī Halatuituia. However, his son Siaosi Tuku‘aho (the premier), who had befriended the missionaries, personally interceded with his father, allowing the missionaries to lease a small parcel of their family’s estate in Mu‘a between the government road and the lagoon. This parcel was called Hilatali. Viliami Toluta‘u explained that this was a personal arrangement between father and son and not one between the minister of lands and the premier because the official view was not to support the Latter-day Saints.[14] A meeting with Tungī on November 23 set the lease at twenty dollars per year for the property.[15] The Samoan Mission provided five hundred dollars to pay for a load of lumber from New Zealand to build a house on this property.[16] The elders also bought a fully equipped thirteen-foot sailboat for $48.75 and named it the Hilatali.[17] This allowed them to travel the seven miles to and from Nuku‘alofa across the lagoon rather than walk the twelve miles around it; however, if there was little or no wind, the elders had no choice but to row the boat.

Additional Missionaries

Just before the end of the year, Elders James Kinghorn and William P. Hunter, who had been sent from the Samoa Mission, joined Smoot and Butler to assist with missionary labors. On December 29, 1891, Hunter wrote, “Put our luggage in our boat and pulled for Mu‘a where we found a very nice little house ready for us built by Elders Smoot and Butler. They had put the house together and the roof. . . . We will help to do the finishing.” The transition in bringing these additional elders to live at Mu‘a was eased by the fact that Hunter and Butler had been “old school chums.”[18]

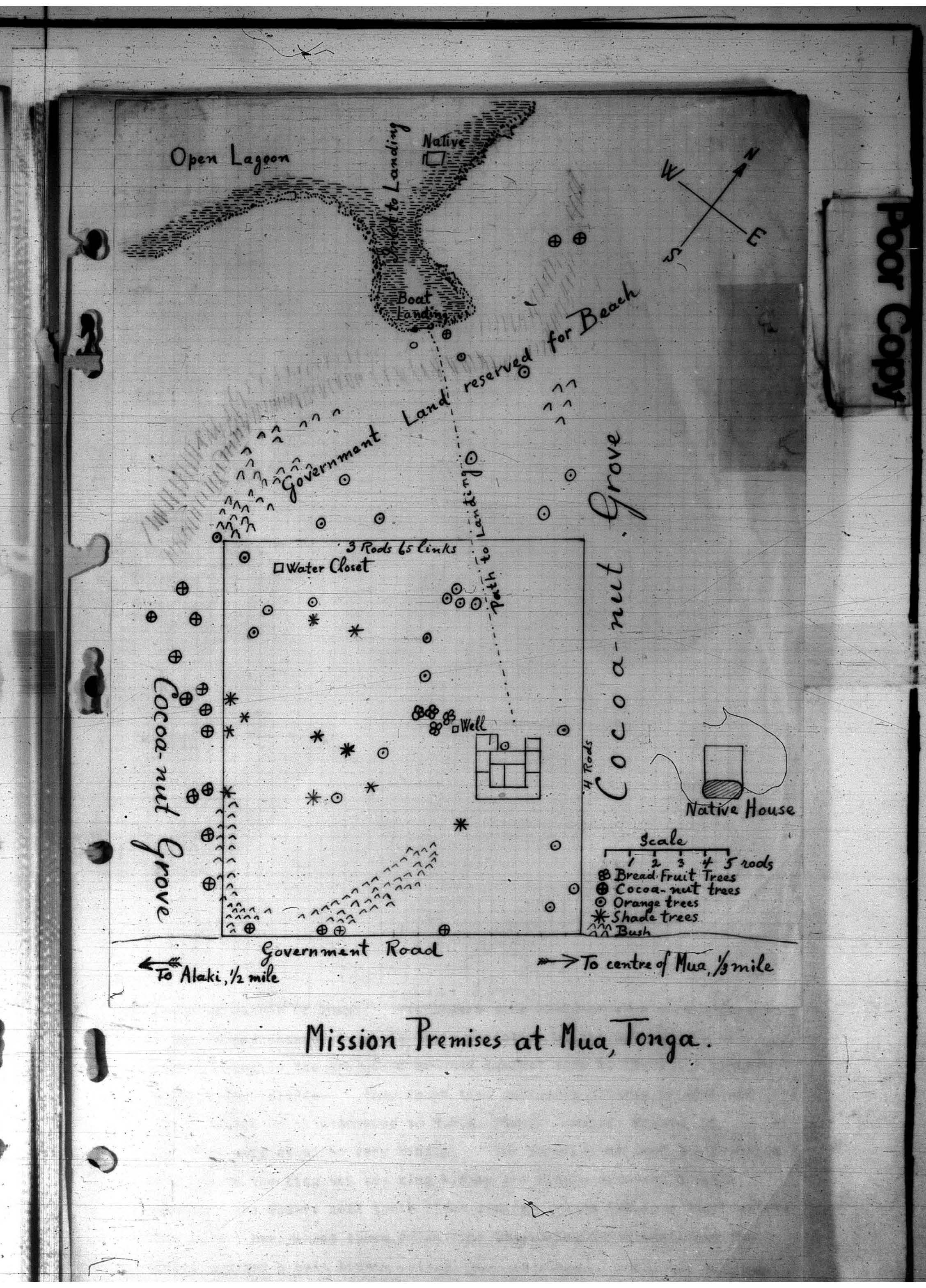

Mission premises at Mu‘a. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Mission premises at Mu‘a. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Although Smoot and Butler had erected basic living quarters, there was plenty of hard work to do in developing the property. Two days after the arrival of Hunter and Kinghorn, Hunter noted, “Bro. Butler and I started to build a well. The clay is the hardest and most stickey I ever saw[.] we did not dig six feet all day and were tired when we quit.”[19] Nearly a month later, they were still digging the well, and the coral they encountered made the hard clay seem soft. Hunter noted on January 25, 1892, “Started again in the well, but on account of it being very hard coral we only dug four inches.”[20] The elders persisted and finally two months later they “struck water in the well” after months of “digging through solid coral with only a pick and shovel.”[21]

The following month, the physical labor on the mission home and property began to be augmented with intellectual labor—language study for the elders. In early February, one of the missionaries wrote, “Brother Smoot started us to studying the pronouncing of the Tongan language.”[22] Before Smoot arrived in Tonga, a Tongan in Samoa named Mataele had walked out three miles from Apia to the Samoan Mission headquarters at Fagali‘i to start teaching him Tongan. His fluency in Samoan after having been a missionary in Samoa for two years gave him a head start in learning Tongan.[23] When Hunter and Kinghorn had arrived in Apia and learned of their assignment to Tonga, they too began trying to learn Tongan.[24] Once in Tonga, they were often diverted from their language studies by regular trips to Nuku‘alofa to check the mail for letters from home. The anticipation of mail was ever present with these Utah elders far from home.

Mission premises at Mu‘a. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Mission premises at Mu‘a. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Elder Olonzo D. Merrill arrived in Tonga on May 26, 1892, to join Elders Smoot, Butler, Hunter, and Kinghorn. Smoot recorded the scene in his journal: “Was not long in picking my young native friend Metaele [Mataele] out among the crowd. At the time I discovered him, he was in the act of pointing me out to my successor, Bro. O. D. Merrill from Richmond, Cache Co., Utah, with whom I shortly afterwards shook hands and introduced myself and we were soon old friends. My first impression is that he will make a good missionary and soon acquire a knowledge of the native language.”[25] This appraisal quickly proved true.

Learning the Language

Trying to master the difficult language would be the first real test of patience for Merrill, a Utah farm boy who had never been far from his country home. The days and nights that immediately followed his arrival would be filled with diligent study from his Tongan Bible side by side with his English Bible.

Elder Merrill’s first Sabbath in Tonga, May 29, 1892, was a rainy one, and no natives turned out for the morning Church meeting. Notwithstanding, the missionaries attended, and those who could speak Tongan shared their testimonies. In the late afternoon, another Church meeting was held in which twenty Tongans were present, 90 percent of whom were males.

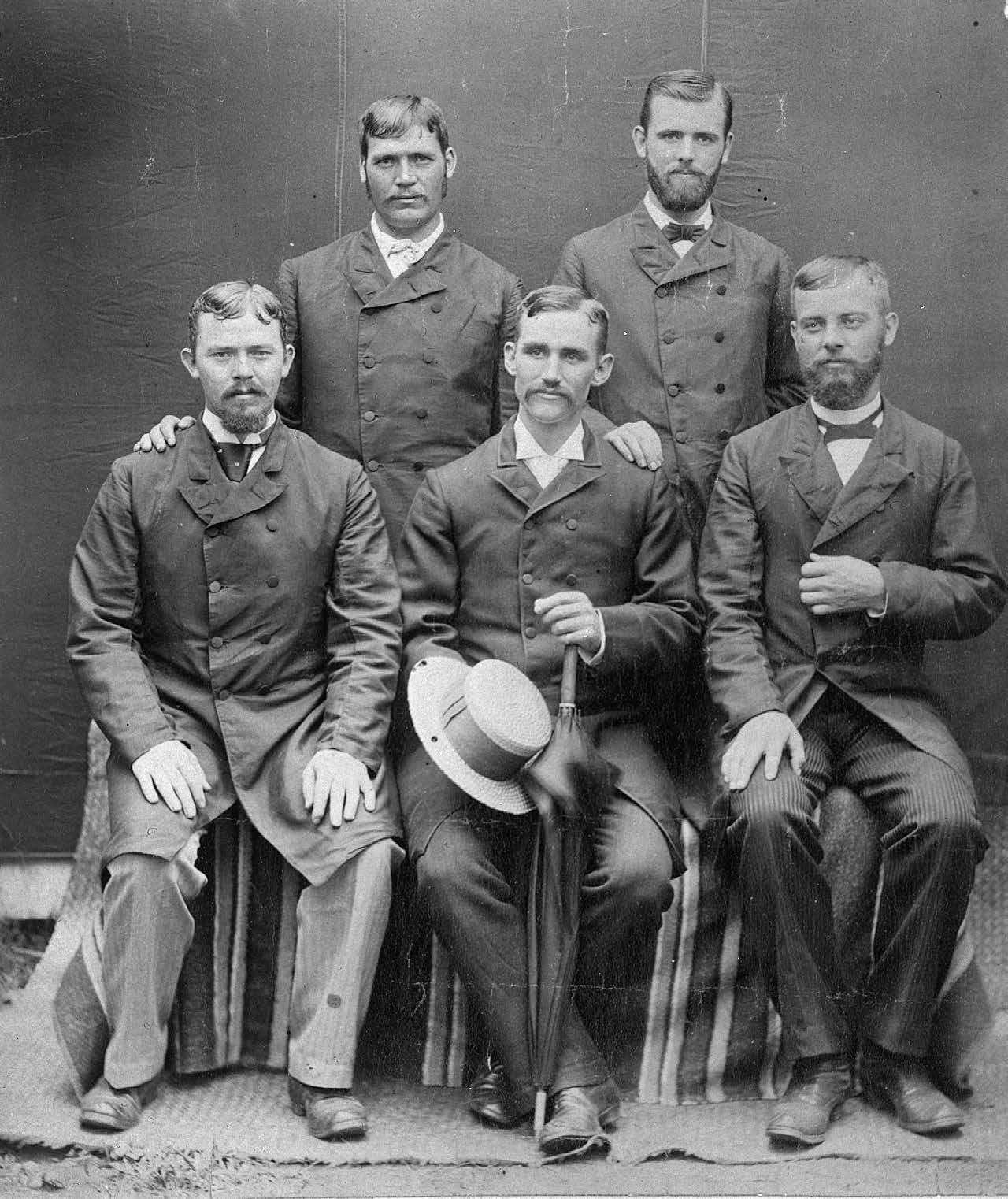

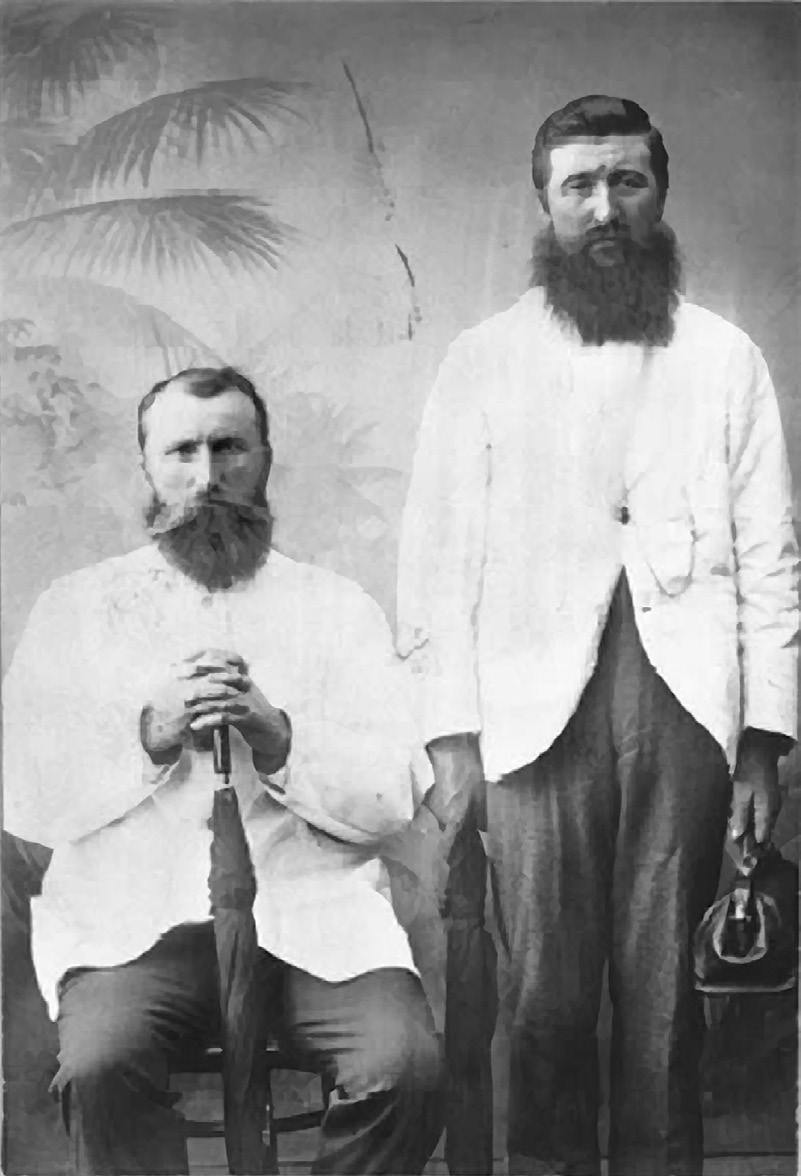

Missionaries in 1892. Top left to right: Elders James Kinghorn, Alva Butler; bottom left to right:

Missionaries in 1892. Top left to right: Elders James Kinghorn, Alva Butler; bottom left to right:

Elders Olonzo Merrill, Brigham Smoot, William Hunter. CHL PH 1871.

That same evening, Merrill recalled, “We all spoke expressing a determination to put our undivided attention to securing the language and learning the principles of the Gospel.”[26] The acquisition of the language was so important that just days later they issued a decree with penalties attached for each rule violation: “As we seem to make little progress in the language, we passed a resolution this evening to the effect that three days in every week there is to be no talking in English; but all conversation is to be carried on in the Togan language. Those violating this rule is to translate one passage of scripture from English to Togan and . . . to cook and keep house one day.”[27] Elders Hunter and Butler also wrote their own accounts of this agreement—they all resolved to work hard to learn the language.[28]

Another method that Elder Hunter used to learn the Tongan language was to begin copying a Tongan dictionary by hand. By mid-November 1892, the elders decided to copy a Tongan dictionary they borrowed from Mr. Lynch. Three of the elders also agreed to each copy one page every day for fifty days to complete the project.[29] These efforts were coupled with a year-end three-day fast to obtain greater faith, which included a mastery of the Tongan language.[30] The language acquisition eventually came, but notwithstanding their united faith, the trials continued as a new year dawned.

Starting a School

On July 15, 1892, an eventful day occurred when Siaosi Tuku‘aho, the premier of Tonga, visited the Mu‘a mission home and spent about a half hour talking with the missionaries, who were seeking permission to start a mission school. The goals were to teach English and to preach the gospel. Merrill recorded, “Brother Smoot talked to him about our condition here and got his permission to start a school here. And he also informed us that the people were, by law, free to join any church they felt disposed. He also seemed quite interested in our Book of Mormon charts which were briefly explained by Bro Smoot.”[31] Coincidentally, exactly one year had passed from the time that Smoot and Butler had arrived in Nuku‘alofa with the hope that the premier would allow a school to open.[32] The missionaries ordered school supplies from New Zealand, which arrived on August 15. They were then ready to start a school.[33]

On August 22, 1892, the missionaries opened the Mu‘a mission school with eighteen children enrolled, and a crowd arrived for this special occasion.[34] Yet by the end of the month, attendance was low. Elder Merrill painfully observed, “Our school seems to be almost a failure; the missionaries of the other religions have advised the people not to come: this has so far put a stop to the day-class of children; the parents obeying the orders of their preachers keep the children away. While our evening class has greatly diminished for the same reason there are four or five who say they will continue.”[35] Although this school eventually closed for lack of students, another school was opened September 19, 1893.

One of the few who later enrolled in the school in January 1894 was the youngest son of Tuku‘aho, the premier of Tonga. William Tupoulahi was brought by his mother, Siu‘ilikutapu. Merrill recalled, “Tukuaho’s wife . . . came with William Tupou Lahi today and had him join the school. We think it will have a good effect for these dignitaries to take some interest in us and we hope and pray that the school will succeed.”[36] This same son later became known as Tungī Mailefihi (converging chiefly lines). He married Queen Salote in 1917 and become premier of Tonga until his death in 1941.

The elders not only taught these young people but also learned from them. In one journal entry Merrill wrote, “I spent most of the forenoon talking with them [two students] and getting them to assist me in the language.”[37] Their efforts in learning the language paid off, and they continued the school as well as their preaching tours at different villages on the island of Tongatapu. On such excursions, the elders always made sure to seek permission from the leaders of each village in order to follow proper cultural protocol and avoid problems.

Early Converts and Opposition

Although the elders were eager to learn the language and were also careful to observe local customs, a strong opposition to their presence was spearheaded by Protestant ministers. Merrill wrote, “It appears very much like the other churches have combined their forces to hinder the people from comming [sic] to our meetings.” Notwithstanding, that same day, August 7, 1892, Merrill noted, “We held a sacrament meeting in the evening and after it was over Bro Smoot and I went to the . . . evening testimony meeting of the Wesleyan Church.”[38] Such efforts were used to learn from the local community and build bridges despite the opposition. In the meantime, some listened and pondered but were unwilling to go against their chiefs and ministers.

One friendly minister was Reverend J. B. Watkin, who was then head minister for the Tonga Free Church. He is mentioned in a very favorable light by both Smoot and later by Merrill. Regarding Reverend Watkin, Smoot noted the following: “We made Mr. Watkin a call and found him at home this time. Had a half hour very pleasant chat with him. It will be remembered that he was Baker’s colleague and is now the head of the Free Church and Minister to the king. Must say that he appears to be the fairest minded minister that I ever met. One of his expressions ‘I consider a good L.D.S. as good as a good anything else.’”[39] Merrill wrote, “Went to buy some hymn books of the Rev. [J. B.] Mr. Watkin. I was introduced to him by brother Butler and he seemed to be a very kind old gentleman. We gave him a Tongan tract and asked about the books we wanted, but he said he did not have very many on hand but, would make us present of a half a dozen: we thanked him very much for his kindness.”[40] On another occasion, Watkin also gave the missionaries six free Bibles, as noted by Merrill: “Mua Thursday Nov 15 1894 . . . went to the Rev Watkin to buy some bibles but he would not accept pay for them. He talked very kind and made us a present of six bibles valued at a dollar each. We thanked him for his kindness but wondered how he could afford to do it.”[41]

Over time, Merrill and his companions witnessed a few Tongans who desired to join the Church, the first Tongan being a man by the name of ‘Alipate. Elder Merrill noted the following: “Mua Sunday Sep 11 1892 . . . Brother Smoot and I went to Vaini and the other brethern staid home to hold services. After meeting we . . . then started for home accompanied by Alibati who, wished to be baptized after we got home. The ordinance was performed by Brother Smoot.”[42] Of this event, Elder Kinghorn recorded, “Bro. Smoot performed the ordinance and Brothers Smoot, Butler, Merrill, Hunter, and myself confirmed him. Brother Smoot was the mouth piece. This was a happy day for all, being our first member.”[43] These were the only baptisms the elders on Tongatapu would have until 1911.

Though many listened, most did not give heed because they feared the king and the ministers of the Free Church of Tonga. Two weeks later Merrill wrote, “There was a large crowd at the afternoon meeting and Brother Smoot did all the preaching giving them a good dressing down for being such cowards in not daring to act according to their own conscience but are so tied to the chiefs in religious affairs when the law of the country allows and should secure their freedom.”[44] Disapproval of the message by chiefs, families, and peers hindered acceptance.

On another occasion, Merrill wrote of how some (including a preacher) listened to the elders’ sermons and wanted to join, but could not overcome community disapproval:

The bell was rang for meeting at the appointed time and meeting began, (Bro. Butler having charge) with one present but in a short time several more came and we held a good meeting. Bro Kinghorn opened, Brother Butler preached, and Bro Hunter dismissed, all paid strict attention and as soon as most of the crowd left a preacher told us he knew he did not teach the plan of salvation as written in the scriptures and that he was satisfied that we had the truth. He is an officer in the city and gets his living through that and his preaching and of course he don’t want that to stop which it would do if he joined the Church of Christ. He acknowledged that he was a coward and dare not join for fear of the mocking of the people. Our words sink deep in the hearts of some of the people and they know we have the truth.[45]

Elder Hunter, also referring to this event, noted, “A preacher told us today that the people know we are right but were like him they are cowards also ashamed or afraid of what the chiefs and people will say if they join.”[46]

In addition to the fear of what their chiefs, family, and friends would say should they openly espouse the doctrines the missionaries were preaching, there was also the danger of losing access to the land the chiefs controlled. A second concern was that these palangi (white people) from America were seen as perhaps too young to be worthy of the respect normally accorded to ministers of the gospel. They came without a knowledge of Tongan customs and language even though they were interested in learning. Time would tell.

Missionary Labors

Elder Brigham Smoot had been in the mission field for three and a half years, so George E. Browning, the new president of the Samoan Mission, wrote a letter in October 1892 releasing him from missionary service and appointing Merrill as presiding elder. Butler wrote, “After a short speech Bro S. gave Bro M. charge of the mission. The spirit of God was with us and we enjoyed ourselves, but it was with deep feelings and emotions when we think how short a time for Bro S. to remain with us.”[47] Of this occasion, Hunter recalled, “Bro S. called a meeting of the Elders and after instructing us sometime relinquished all his rights to preside and Bro M. took the head of the table. We all spoke and expressed our determination of sustaining and supporting Bro. M as we had tried to sustain Bro S.”[48]

The elders marched on and continued taking preaching tours. Alva Butler recalled that these excursions were challenging: “It is quite difficult to get to talk with the people. They have been told so much stuff about us. Many treat us with silent contempt others laugh, mock, and call us names while a few feel to listen and treat us with respect. Indeed a missionary’s life is not always pleasant.”[49] Merrill remembered, “Brother Kinghorn and I started out on a preaching trip to the Fuamotu district, . . . went on to Hamulu, a Catholic village, . . . and when they sat down to drink kava we told them our business, read the articles of faith and several passages from the bible but it did not take affect. . . . After bearing our testimony to them we left the village.”[50]

After departing, Merrill said they were met by a man who asked if the elders would preach. Merrill responded that if the people in the village so desired, they would come. Merrill and Kinghorn were then brought to a meetinghouse, and a chief came and approved the meeting. The chief also sent out runners to assemble the villagers. Merrill’s humility is evident in his writing: “After the crowd assembled we began but we were two scared boys and felt our dependence on the Lord and he certainly did assist us.”[51] Despite their apprehension, the missionaries nevertheless shared their message, and the crowd appeared very appreciative.

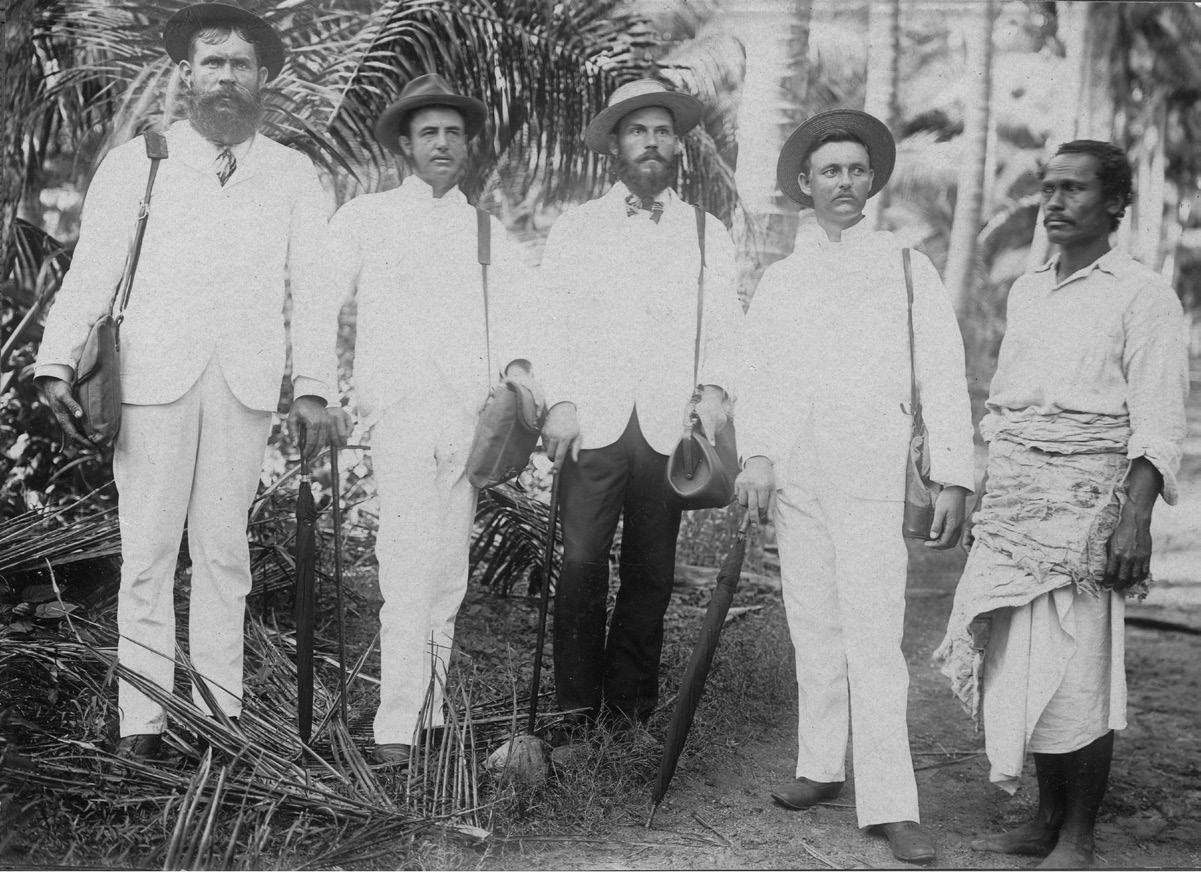

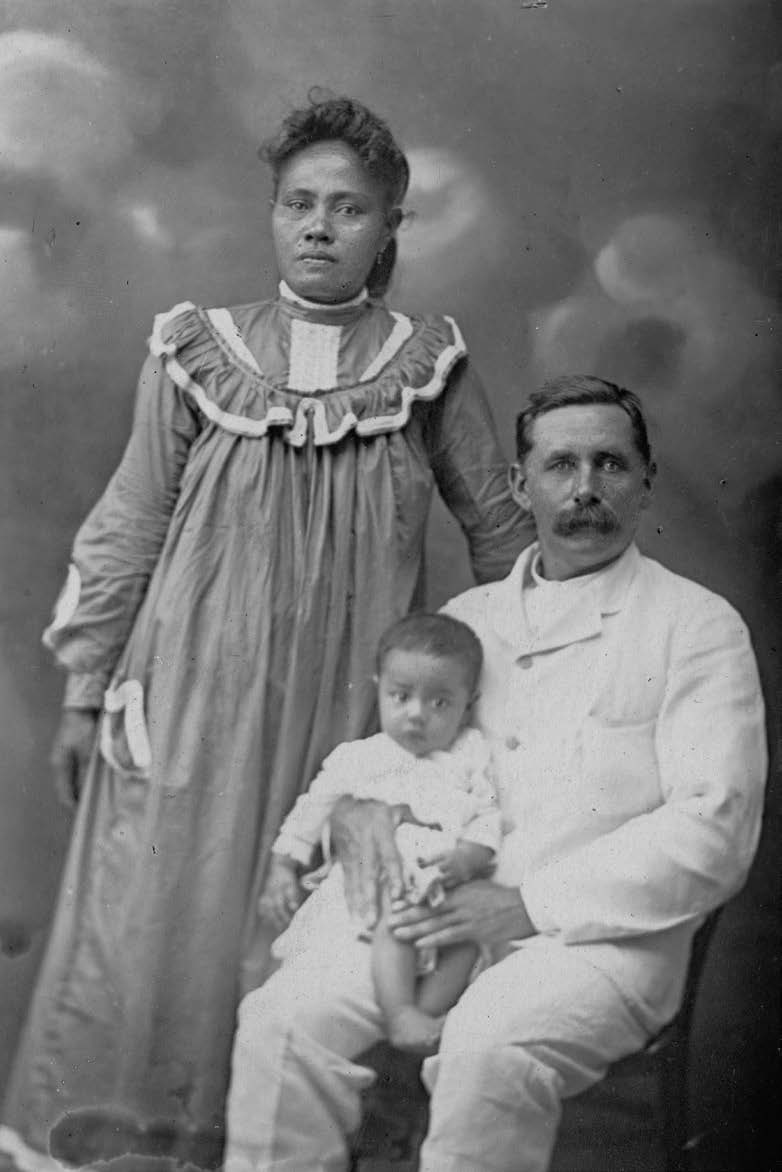

Elder Alfred and Sister Margaret Durham with Elder Thomas and Sister Maria Adams on their way to Tonga. Courtesy of Carl Harris.

Elder Alfred and Sister Margaret Durham with Elder Thomas and Sister Maria Adams on their way to Tonga. Courtesy of Carl Harris.

The missionaries carried on their labors with diligence and were mindful not only of the local chiefs, but also of the monarchy. In early March, ninety-five-year-old King George Tupou I passed away, and notwithstanding the pouring rain, the elders agreed that they, like everyone else, should show respect to the Tongan government and people by attending the royal funeral.

On April 15, missionaries from Utah arrived unexpectedly. Merrill recalled that while eating his breakfast, “I was suddenly called out by two young men who introduced themselves as Elders Thomas D. Adams and A. M. Durham of Parowan, Iron County, Utah and told me they had their wives on the Steamer, which completely upset me as we were not at all prepared to make sisters comfortable, I went down to the boat and met the sisters, Luella Adams and Maggie Durham.” Further, “The brethren were as greatly surprised as I had been to learn of the arrival of the new company but nevertheless we all felt thankful to the Lord that they had come to assist us in our labors.”[52]

The following day was the Sabbath, and Tongans thronged around to see the new missionaries, who were both newlywed couples. The missionaries held Church meetings and performed the baptisms of Poasi Niu and Mele Sisifa. At an evening testimony meeting each of the missionaries “expressed a determination to do his best in rolling on the work of the Lord.”[53] Thomas D. Adams wrote, “There were about fifty natives present and all seemed anxious to see the new missionaries.”[54]

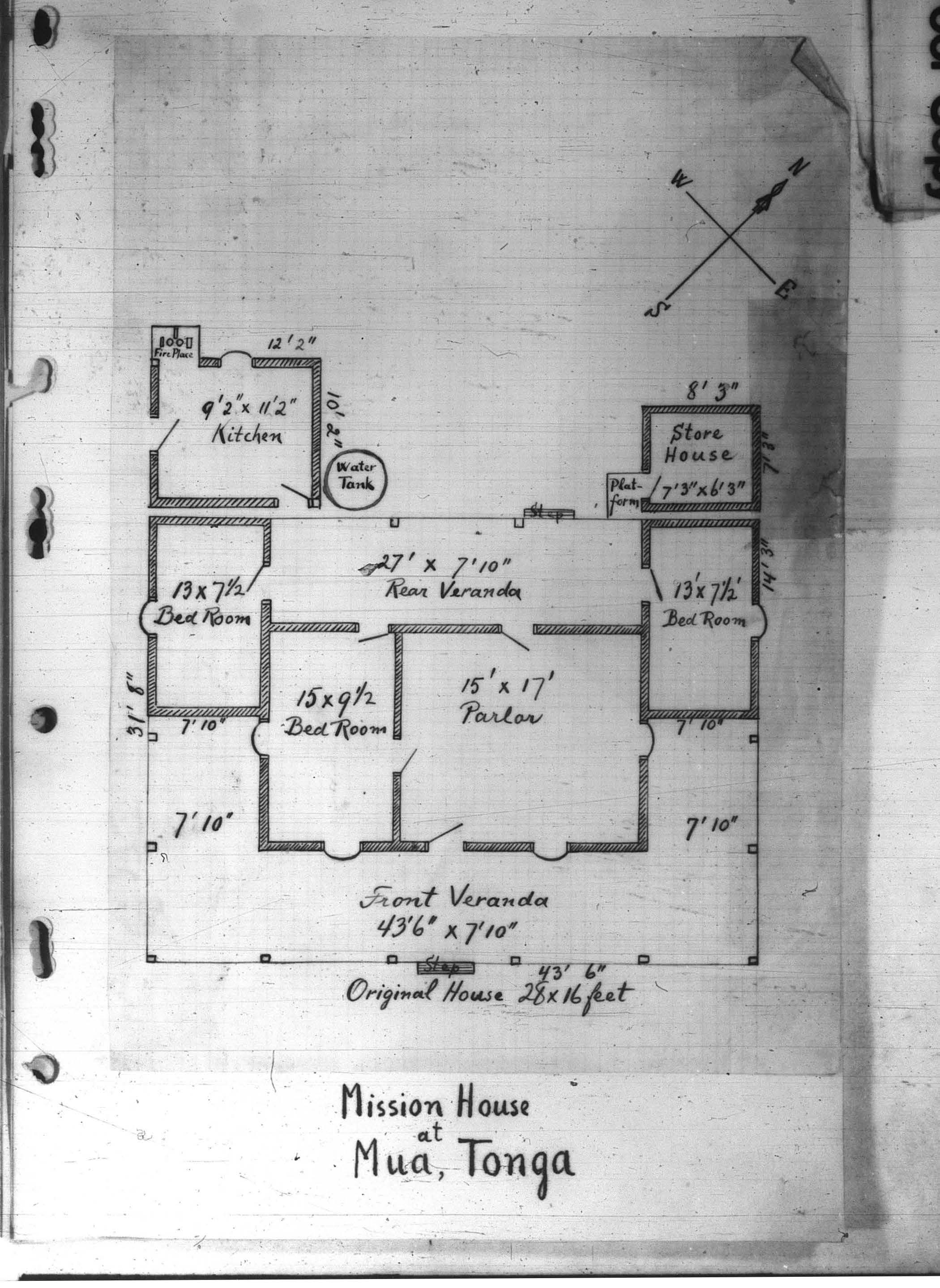

Having more missionaries necessitated building bigger quarters to avoid cramped conditions. The elders soon made plans for obtaining more building materials, which included a trip to Nuku‘alofa to look into the purchase of lumber.[55] With time and patience, the elders and the missionary couples grew to love one another and worked as one; they built an addition to the original mission home at a cost of $325.

Opening Ha‘apai

These overcrowded conditions seem to have encouraged Elder Merrill to make a decision the following month to send Elders Kinghorn and Hunter to Ha‘apai, with Kinghorn being appointed to preside over that area of the mission.[56] Of this event, Kinghorn noted, “Bro. Merrill . . . said he thought it was time we were beginning to scatter out. He then appointed Bro. Hunter and I to go to Haapai and open up the mission there. It made me feel rather shakey but I felt it my duty to respond.”[57] Hunter also recorded this notable announcement: “Bro. Merrill informed us that . . . it was time for us to spread out a little and that Bros. Kinghorn and I was to go to Ha‘abai.”[58]

Elders Hunter and Kinghorn sailed for Ha‘apai on May 31, 1893. At Pangai on the island of Lifuka, they found a “shanty” owned by a Mrs. McGregor for which she charged $1.25 per week. Their first cottage meeting on June 7 was attended by fourteen investigators. A week later, Elder Hunter said that a few people were coming, wanting to join the Church without knowing what it was.[59] By June 19 forty people were attending meetings. Within a month, they began visiting neighboring islands. In July they visited around Lifuka, Foa, Ha‘ano, and Ha‘afeva. However, a measles epidemic in August killed a thousand people in Tonga. The elders were unable to proselytize but instead ministered to the sick.[60] Each time they entered a village, they would seek out the pule kolo (town officer) and ask permission to hold a meeting in his village. If he agreed, they would walk around the village hoping to be invited into a house where they could strike up a gospel conversation. As any white man was a curiosity, this was initially easy to do until the ministers found out and discouraged interaction with the missionaries.

Elder Merrill came to Ha‘apai on October 24 to check up on them. During this visit, Elders Merrill and Kinghorn made a visit to the island of Nomuka. Elder Merrill returned to Mu‘a on November 21. In his year-end report, Elder Merrill noted that missionaries had visited all fifty-nine villages on Tongatapu, borne their testimonies, and held some meetings.[61]

At Pangai the elders met Mr. James Edward Giles, a merchant and baker from England who was married to a Tongan woman and who showed some interest in the Church. He offered much-needed help, and they visited with him almost every day. He took the missionaries under his wing and either invited them to eat with him or gave them food to cook. On January 17, 1894, he declared his intention of being baptized but still had challenges with the Word of Wisdom. On ‘Uiha the elders met a native named Vatu who wanted to get baptized but did not show up at the appointed time for the ordinance because of ridicule from his family and friends.[62] Their first baptism in Ha‘apai occurred on February 12, 1894, after seven months there, when they baptized Tevita Halaiano.[63]

Elders in Ha‘apai: Left to right: Amos Atkinson, Alfred Kofoed, William Hunter, Albert Jones, and Tevesi Lutui of Nomuka. Alfred Kofoed collection courtesy of Perry Special Collections.

Elders in Ha‘apai: Left to right: Amos Atkinson, Alfred Kofoed, William Hunter, Albert Jones, and Tevesi Lutui of Nomuka. Alfred Kofoed collection courtesy of Perry Special Collections.

At Mu‘a, Sister Margaret Durham, who was very young and in fragile health, gave birth to a baby girl on January 26, 1894, without the assistance of even a midwife; the baby died the same day. By law the funeral had to be held the next day,[64] and the tiny fbody was carried to the Si‘amoka cemetery by Tupouto‘a, the town pule kolo of Tatakamotonga, and laid to rest under a roughly chiseled coral slab headstone. Not long after this tragedy Sister Maria Adams took it upon herself to start up another school at Hilatali.

Also on Tongatapu, Elders Amos Atkinson and Albert S. Jones arrived on March 31, and Elders Butler and Kinghorn were released and sailed for the United States on June 13. Elders Merrill and Durham made their first visit to ‘Eua on September 1 and then returned to Tongatapu, where Elder Merrill started an evening school in November that lasted until May 1895.

Elder Albert Jones began serving with Elder Hunter in Ha‘apai in 1894. On July 4 they sailed to Nomuka on a trading schooner and stayed with a trader named Mr. Sandys. Four days later, they baptized a native named Tevesi Lutui, who was a former Wesleyan minister. His acceptance and willingness to be baptized so quickly was surprising to the elders. As Savani Aupiu has noted:

In Tonga, villages were relatively small and everyone knew everybody’s business. Gossip and backbiting were common problems in these small communities. People did not like to be the topic of gossip because it brought shame upon their family name. It was important not to do anything outside accepted norms. Many people refrained from listening to the missionaries simply because they did not want to be mocked and teased. It was more important for Tongans to be accepted among their family members, friends, village, and religious leaders than it was to be a Mormon.[65]

Back at Pangai, on July 17, the Crichton family from Nofoali‘i, ‘Upolu, Samoa, were baptized; Robert Crichton and his wife, Loua Fau Crichton, were baptized, and their three young children were blessed. Also baptized was Sister Crichton’s brother, Samuel Fau. That same week they baptized Siosateke Vainekolo, and Mele Sumu. The next Sunday Elder Jones recorded that there were now five members at church.[66] Unfortunately, the Crichton family sailed back to Samoa on August 16. There they raised a fine family that remained strong in the faith.

Elder Merrill, the presiding elder, along with Elder Thomas Adams, arrived at Pangai, Ha‘apai, on September 16. They arrived just in time to baptize a young man, Sione Paula, on Sefptember 18 and another, Semisi Ta‘ai, three days later before they returned to Tongatapu.

Elder Hunter baptized James Edward Giles, their English friend, on October 14, 1894, just before he was released. At Brother Giles’s request, Elder Hunter took his eleven-year-old daughter, Rachel, with him back to the United States to get an education.

The first Tongan to receive the Aaronic Priesthood was Tevesi Lutui, who had been baptized on Nomuka a couple of months earlier and was ordained a deacon on September 28, 1894.[67] He was evidently the only Tongan to be given the priesthood during this era of missionary work in Tonga.

Elder Jones’s report for December was not encouraging. He stated, “Our members are getting very negligent in attending to their meetings, we will have to talk to them and wake them up.”[68] Then on December 12 they heard that the “Tongan government passed a law that no Religious Body can hold meetings in any private house.” He thought this would be a hindrance but would not drive them out. About that same time, three more natives came asking to join the Church, but they were told to study more.[69] It seemed as if every palangi (white person) in Pangai stayed drunk over the Christmas and New Year’s holiday, which cast a pall on the holiday spirit, in the elders’ opinion. The government and demon rum seemed to combine against the missionaries and their work.

On Tongatapu, Elder Merrill summarized the elders’ activities for 1894: “The brethren made frequent visits to the different villages on Tongatapu and held meetings wherever an opportunity was given, and though none were baptized they made quite a number of friends, many of whom expressed their belief in the principles taught by the Elders, but lacking courage or sufficient willpower to stem the popular feeling by yielding obedience to the same.”[70]

When Elder Adams returned to Tongatapu on January 24, 1895, neither Elder Jones nor his new companion, Elder Robert Smith, could speak much Tongan, so they went back to the rule that Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays were days for speaking Tongan only. Elders Charles Jensen and Alfred Kofoed arrived on February 12, and Sisters Margaret Durham and Maria Adams were released because of ill health. Therefore, Sister Adams closed her little school at Hilatali that she had conducted since April 16, 1894. She had only three regular pupils.[71] It was probably to this school that the premier’s wife brought young Tungī to learn some English. Elder Durham escorted them as far as Apia, Samoa, then returned to Nuku‘alofa. On April 14 Tongatapu was divided into three districts—East, Middle, and West. A companionship was assigned to visit each district at regular intervals. Elder Adams started an infrequent school at Pangai, Ha‘apai, on June 13, 1895. Elder Olonzo Merrill was released as conference president on July 22 and sailed for America on August 7. He was replaced by Elder Alfred Durham as presiding elder.

Visit of Andrew Jenson

Andrew Jenson made a visit to Tonga from August 22 to September 9, 1895, in his official capacity as the assistant Church historian.[72] He was on a two-year worldwide tour to collect Church history and to train missionaries and members on how to keep records. While in Tonga he provided the following description of the mission home at Hilatali: “The mission house consists of a four-roomed frame building facing southeast. The two large rooms were built in 1891‒2, and the smaller added in 1893. There is also a small kitchen and a little storehouse adjoining the main building. . . . The land on which it stands—[is] about one and a half acres . . . , and the mission pays $20 per annum in rent for the use of it.”[73]

Jenson’s description of the work ethic of the missionaries was certainly complimentary:

The young Elders when at their mission headquarters are by no means idling away their time. They are studying hard to learn the language and to post themselves in regard to the principles of the Gospel; and their hearts are in the work before them, and it would be unjust to ascribe the little success attending their labors so far in Tonga to any lack of energy and earnestness on their part. The usual daily routine at the mission house is to rise about six o’clock in the morning, and have prayer at seven. Before prayer is offered a chapter or two is read from the Tongan translation of the Bible, and a hymn sung, the same is repeated in the evening, prayer being offered at 8 p.m. . . . Tuesday nights are devoted to testimony meetings, conducted in the Tongan language, and Thursday evenings to singing practices. The general meetings are held on Sundays, namely, at 9 a.m. and 3 p.m. In the evening a testimony meeting is held, the English language being used.[74]

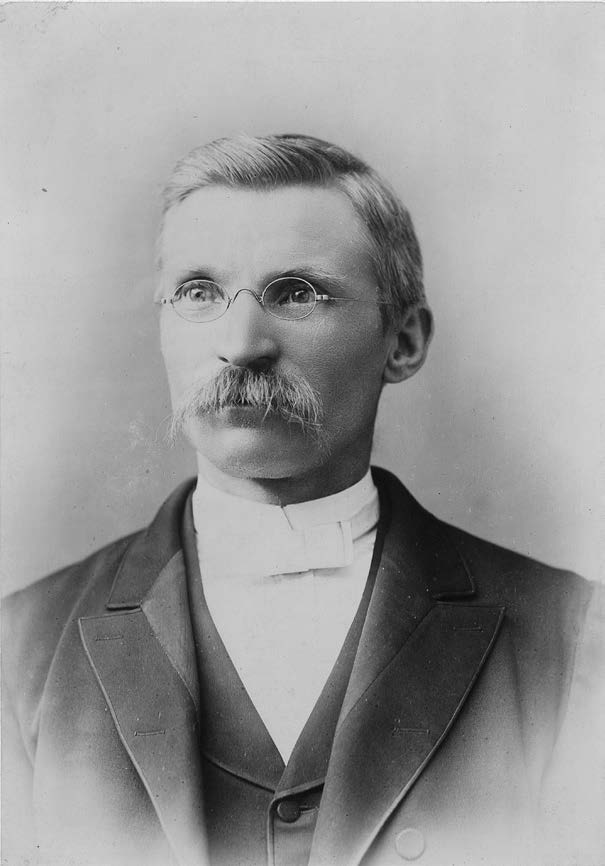

Andrew Jenson, Assistant Church Historian.

Andrew Jenson, Assistant Church Historian.

On August 27, Elders James Welker and Charles Jensen were assigned to accompany Andrew Jenson onward as far as Vava‘u and to open up these islands for missionary work. Before he left Tongatapu, Andrew Jenson gave a well-received lecture in Nuku‘alofa to most of the Europeans there. The elders were introduced to King George II at the royal palace on September 6 by the Reverend J. B. Watkin, president of the king’s Free Church of Tonga.

Stopping at Ha‘apai, Brother Jenson noted, “The Elders on the Haapai group have been a little more successful than those laboring on Tongatabu, as they have baptized twelve persons, one of them a white man, since the mission was first opened on the group in May, 1893. But otherwise it is the hardest field of labor of the two.” He further noted, “Belonging to the Haapai group there are sixteen inhabited islands, some of which are many miles apart and not easy of access. Through the kindness of the white traders located on the different islands the elders have been able to visit all of the most important members of the group.” Further, he noted, “it may be said in this connection that nearly all the white people in the Haapai group have been very kind and hospitable to the Elders since their first arrival there; they have not only given the missionaries free passages on their trading vessels; but have lodged and fed them on many different occasions, when the natives seemed indisposed to give them a welcome.”[75]

While at Pangai for a day, Brother Jenson gave a lecture to the small European community and had a fine dinner with Brother Giles, the only European member in Tonga.

Opening Vava‘u

Arriving the next day at Neiafu, Vava‘u, Elder Charles Jensen recorded that the first thing they did was to ask some Europeans about holding a meeting. A small schoolhouse was put at their disposal. Nearly all the Europeans in town, mostly Germans, attended the meeting, and Andrew Jenson spoke for over an hour. Then they returned to sleep on the steamer. The next day, September 9, 1895, they hiked up Mount Talau, where they sang “We Thank Thee, O God, for a Prophet” and then knelt in prayer. Jenson noted: “We dedicated ourselves to the Lord’s service on that land.”[76] He added that they dedicated “the Vavau group of islands and its people to the preaching of the Gospel . . . the Spirit of God rested upon us, and we rejoiced as servants of the Lord only can rejoice when they know they are in the line of their duty.”[77] Afterward, Andrew Jenson sailed on to Samoa.

Elders Charles Jensen and James Welker. Charles Jensen collection.

Elders Charles Jensen and James Welker. Charles Jensen collection.

Once the missionaries were settled in their little house in Neiafu, many natives stopped by to see them, and there were many opportunities for gospel conversations. Sixty natives attended the elders’ first cottage meeting. On September 26 they met an old Norwegian sailor named Jacob Olsen. Jacob had jumped ship, fallen in love with a Samoan woman, and moved to Vava‘u. They began teaching Jacob and his wife, Vika, on October 13 and visited them regularly and enjoyed their hospitality.[78] Jacob Olsen soon became their best friend and benefactor.

Elder Charles Jensen recorded that they made regular visits to Ha‘alaufuli, a village in Vava‘u. There they met a chief named Afu who would become a local stalwart member when the missionaries returned to that village.[79] Jensen and Welker did not attempt to start a regular school but did mention teaching a handful of children some English. Elder Alfred Durham was released on March 25, 1896, as presiding elder in Tonga and returned to America. Elder James Welker replaced him as presiding elder.

After eleven months in Vava‘u, the elders finally baptized their first converts, ‘Isileli Namosi and Sione Tania, also known as Sione Toutai. Sione soon returned to his home island of Foa, Ha‘apai, where he had been known as a good friend of the elders. On Foa, Toutai told the elders that his house was available every Sunday for meetings.[80] Namosi was a man of some prominence and was in line to receive the noble title of Fulivai and to be the pule kolo (town officer) of the island of Hunga; however, when it was discovered that he had become a Latter-day Saint the offer was withdrawn.[81] Namosi told Elder Jones that the other chiefs thought “he would not work hand in hand with the Free Church.”[82] The elders also met an important chief named Kalauta.[83] The elders called all interested parties to come to their services by pounding on a lali, a Tongan drum or slit gong. They also had regular discussions with Inoke Fotu, the high chief and chief judge of Vava‘u.

Jacob and Vika Olsen. Alfred Kofoed collection courtesy of

Jacob and Vika Olsen. Alfred Kofoed collection courtesy of

Perry Special Collections.

At one point their landlady told the elders they had to move to another house. They were offered a larger abode by their good friend Sione Pota Uaine, a prominent preacher in the Free Church. Uaine, though converted to the elders’ message, could not publicly make the change. Many people came to hear the gospel at Sione’s home, which served as a meeting place.[84]

To visit the many islands in the Vava‘u group, the elders bought a sailboat for twenty dollars from a local merchant, ‘Alipate Sanft. Thereafter the elders sailed between the islands of Vava‘u during the week preaching the gospel then returned to hold Church services back in Neiafu on Sundays.

On October 13 Vava‘u experienced a severe earthquake that damaged the stores as well as the meetinghouse for the Catholic Church. Two days later Elder Welker and his companion, Elder Smith, arrived. They had Elders Jones and Jensen sail with them to Tu‘anuku to catch a trading schooner called the Fleet Wing that would take them to visit the Niua Islands and beyond.

Missionary Journal Entries

The journals of these early missionaries describe remaining in their homes many days and often going out only to visit the various Europeans whose language, culture, and attitudes they could better relate to but who also had little interest in the elders’ gospel message. Nevertheless, these European traders in the various villages and on the small islands invariably were happy to invite the elders in for a meal and to spend the night. Mr. Sandys on Nomuka was an example of one who could always be counted on to host the elders when they visited his island and do all he could to help them along.[85] Elder Alfred Kofoed noted that the captains of the interisland trading schooners could generally be counted on to give the elders free passage wherever they went and feed them on the way.[86] European traders in Ha‘apai were always happy to be able to get the “Mormon boys” to mind their plantation or tend their store while they were away because of their honesty and dependability.[87] These friendships with the European traders were of great help to the elders.

During this early period, a mission home was established on each of the three main groups of islands. These mission homes were like offices where interested natives would stop by for a gospel conversation. They were sometimes also the sites for little schools where both youth and adults would come to receive lessons in English and other subjects. Two to four elders lived in each home, which was also used as a chapel on Sundays. The elders wrote of cooking, washing, and studying.

From these mission homes, the elders would pack their grips for a few days’ trek and visit other villages and islands, where they would first search out the pule kolo and ask permission to hold a meeting. Then they would walk around the village hoping to be invited into a house for a gospel conversation and perhaps a meal, or to join a faikava (a socializing circle gathered around a bowl of kava) and leave a printed pamphlet that they had translated into Tongan. Sometimes they could generate some interest and hold a cottage meeting in the evening. They would travel without purse or scrip, hoping to find a place to stay overnight. The Tongan people were generous with whatever they had, and the elders seldom went without a meal or a niu (coconut) to drink as they walked around. Invariably, the Free Church, Wesleyans, or the Catholic clergy had warned the people not to have anything to do with them, but the sight of two young palangi piqued the people’s curiosity. The European traders in the villages were generally welcoming in terms of food and shelter but seldom had any interest in their message.

This is not to say these missionaries were lazy; their journals describe not only many Tongans coming to their homes to discuss the gospel but also their tours of the many villages and islands of their areas with the aim of holding cottage meetings and looking to find people willing to listen to their message. Often the best they could do was to leave some missionary tracts and hope that they would generate some interest for a future visit in that village or at the mission home.

As with all missionaries, food was very important. Many entries in their journals mentioned what they ate, who cooked it, how they got their food, or where they went to eat. The Tongan people as well as the Europeans were very generous in sharing what they had with these young men from America. Obviously, many of the different foods they encountered took a bit of getting used to. But that was all they had, and sometimes it wasn’t much.

Their journals are also replete with descriptions of their daily devotions, their testimonies, and their gratitude for the many blessings they saw in their lives—how the Lord provided for their wants. Their devotion to their calling is all the more admirable given the isolation they had from priesthood leadership. Not once during these years did their mission president in Samoa come to visit them and give them encouragement, motivation, and training. This isolation is manifest in the attention given in the elders’ journals to the arrival of boats hopefully bringing mail from Zion. During this physical and cultural isolation, far from home and Church leaders, their testimonies and their call as missionaries sustained them through hard times and memorable adventures.

Elders Withdraw from Tonga

Notwithstanding the committed efforts of the elders from Zion, the First Presidency withdrew the missionaries within two years of Andrew Jenson’s visit. On December 4, 1896, Elder Jensen recorded that Elder Jones received his letter of release. Along with his discharge came a letter from the First Presidency (via Apia and Nuku‘alofa) for all elders to settle any outstanding debts and withdraw from Tonga.[88] Elder Jones added “that he was to advise the Elders from Tonga to close up the place and then go where they could do some good.”[89] Elders with more than two years of service would be released, and the newer elders would be reassigned to Samoa. Elder Jensen’s companion, Elder Alfred Kofoed, reacted much more thoughtfully: “A letter from Samoa to Bro. Welker which we had leave to open stating that the Tongan Mission was to be closed, the property to be sold, the newly arrived Elders to go to Samoa the first opportunity or as soon as possible, . . . the exact words of the First presidency.” It further noted, “As soon as it can be done they, the Elders should be helped to square their indebtedness, and then be withdrawn from the Tongan Group and placed where they can do some good for the cause of truth.” Kofoed continued,

I dred seeing this mission closed as there are many good honest souls here. . . . How can we leave our saints, who have boldly steped forth amid sevear persecutions a[nd] much mocking and joined the true fold of Christ, and what words of consolation, and incouragement can we give them. I fear they will be like sheep without a shepherd and will soon be over powered by the raving wolves. . . . And again how can we preach to the people and what can we preach the remainder of the time we will be here.[90]

The decision to close the mission did not come as a total surprise. On July 10, 1896, “Bro Shill received a letter from presiding Elder Welker stating all was well at Tongatapu and that he, [Welker], had received word from the presiding Elder in Samoa that we need not look for any more Elders until further notice. They are contemplating closing this mission unless things takes a sudden turns [sic] for the better.”[91]

The Sunday after the letter arrived, Namosi attended sacrament meeting and “bore a strong testimony to the truthfulness of the gospel and a determination to prove true to the end if he was left alone in the land.” Namosi told the elders that Brother Sione Toutai in Ha‘apai had been stripped of his village offices and that the village intended to banish him because he had converted to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints but that he remained true to his testimony.[92]

When word of Elder Jones’s release reached Ha‘apai, Brother Giles at Pangai asked Elder Jones to take his daughter Louisa to America. On December 24 the Ovalau arrived in Neiafu with Elder Atkinson and three of Brother Giles’s daughters. “Bro Jones took with him Louisa Giles, the daughter of James E Giles age seven years”;[93] they sailed the same day to Apia. The next day, Elders Welker and Smith arrived in Apia from their missionary tour of the Niuas on their way back to mission headquarters in Nuku‘alofa.

Their missionary tour of the Niuas was quite an adventure, which Elder James R. Welker described in a long letter to the Deseret Weekly News.[94] It was written from Mu‘a, Tongatapu, on January 9, 1897. In it Elder Welker described arriving at Niuatoputapu on October 24, 1896. There they met with Governor George Finau and were offered accommodations by Mr. Kiesewette. The following day they held a cottage meeting with about one hundred people attending. On October 29 five men applied for baptism but did not show up at the appointed time because they said their chiefs and ministers mocked them.[95] On November 3 they sailed to Niuafo‘ou, where they were not welcomed, it being a strong Catholic island. From there the schooner took them to the staunchly Catholic island of Uvea, where they met King Lavelua, who would not listen to anything they had to say. The king forbade anyone to listen to the elders and had police officers follow them everywhere until they left. Next, they were taken to the island of Futuna, also all Catholic, where they found no one to listen to them. The schooner then left for Vava‘u on November 22, but a couple of days out the boat sprang a leak and took on four feet of water, so they had to return to Futuna. Repairs were made and they left again, yet the boat sprang another leak. Everyone was told to bail out the water or drown.

The captain thought the winds favored heading to Suva, Fiji, which they reached on December 4. Elders Welker and Smith were then stranded in Suva with no money and no way back to Tonga. They were offered a room with a carpenter named Nicholson and convinced the Union Steamship Company to give them tickets on credit for the next boat heading to Tonga, which went by way of Apia. They finally arrived back in Nuku‘alofa on December 28.

That same day Elder Jensen in Vava‘u was asked by Brother Giles to perform the marriage of his oldest daughter, Emma, to a Thomas W. Mann in Neiafu. This was the only marriage performed by Latter-day Saint missionaries during this early period in Tonga. But for some unknown reason, perhaps because Elder Jensen did not have the legal authority to perform the marriage, Emma and Thomas were remarried by the Reverend J. B. Watkin of the Free Church on January 25, 1897.

Presiding Elder Welker wrote a letter from Nuku‘alofa to Elder Jensen in Neiafu that they “had straightened up all their affairs on Tongatapu and were going to Ha‘apai for a month before taking leave of the whole group of the Friendly Islands.”[96] The elders had sold Hilatali, the mission home on Tongatapu, for $825, the same amount it cost to build it.[97] Elder Jensen shaved off his beard in preparation for returning to America after two years of letting it grow. After meeting with the missionaries almost daily for six months, Jacob and Vika Olsen decided to get baptized on March 17, 1897. Olsen thought he needed to be baptized while he had the chance.[98] Namosi and his wife, Peni Lupe, brought parting gifts, and Sione Pota Uaine threw a grand farewell feast for the elders.

At that point Elder Jensen received a letter saying he was to wait another month for the next steamer. His journal recounts his last tour of the islands and villages of Vava‘u to say farewell to his friends such as the Wolfgramm families in Ha‘alaufuli and in ‘Otea, who would play a significant role in the Church when the elders returned in 1907. Elders Jensen, Jones, Kofoed, and Welker finally departed on April 15, 1897, and the Saints in Tonga were left on their own. Elder Welker took with him Brother Giles’s son, George. Brother Giles and others of his family later emigrated to America at Elder Welker’s invitation in 1901.[99]

Elder Jones felt that only about four members would feel sad at their departure; he thought the rest were too casual to miss them.[100] (When the missionaries did return in 1907, the only people in Tonga who still appeared to be faithful were Brothers Olsen and Namosi in Vava‘u.) On April 16, 1897, on his way back to America, Elder Alfred Kofoed noted that while the people of Vava‘u had largely rejected them, he did not feel to wash his feet against them but asked God to bear with them and again give them a chance to receive the gospel as he knew there were many honest in heart among them.[101] Although the missionaries would no longer ring the bell for meetings and school sessions for a season, their influence would echo to listening ears in subsequent generations.

Factors for the Withdrawal

In her master’s thesis, Savani Aupiu revealed some of the pressures the General Authorities in Utah were facing as they came to the decision to close the mission. She wrote:

Although it was hard for the LDS missionaries to leave Tonga, the decision to remove them was not. On May 7, 1896 the First Presidency and Apostles of the LDS Church met in the Salt Lake Temple to hold their weekly meeting. Of the many issues discussed, the first counselor, George Q. Cannon, reported that the missionary work in Tonga was “of the most arduous character with very unsatisfactory results.” He suggested that because of the “indifference of the people there to the gospel,” missionaries should be withdrawn from the islands. The brethren unanimously agreed and soon after a letter was sent out to the Mission President in Samoa notifying him of the decision.

The indifference of the people there to the gospel may have only been part of the reason why the First Presidency removed missionaries from Tonga. The Church was in transition at the turn of the nineteenth century and it faced many challenges.[102]

At this time the Church was in debt and was forced to divest itself of its interests in various mining and railroad ventures. This was a rough time in Utah because the territory was in the process of becoming a state. The Church had to show that it was reducing its economic and political influence in Utah. This economic hardship forced them to send out missionaries “without purse [or] scrip.” The Church was hard-pressed to expand missionary work or even maintain existing missions, and in Tonga, there had been fewer than twenty baptisms during the years 1891–97 by a combined force of nineteen missionaries.[103] The Brethren would naturally see this as a poor use of resources.

Church leaders were also concerned that many of those being called to go on missions had inadequate education. The church also did not have a systematic lesson program to teach members how to be missionaries. This may explain why one elder in Tonga blamed his failure to convert people on his lack of training. He wrote, “We have not achieved the success in baptizing converts that we often read about in other fields. The main reason, perhaps, is that we are all young and inexperienced.”[104]

What could not be known was that some seeds were planted that would later bear fruit.

Another factor affecting their withdrawal was the Tongan government, which was obviously influenced heavily by the existing Free Church and the Wesleyan Church that were vying for the hearts, minds, and money of the Tongan people. The feeling and official policy was that Tonga was already a Christian nation and that these young men from an American church who taught some peculiar doctrines and had some controversial history would not add anything to the kingdom other than disrupting the status quo that was already in some turmoil.

At the grass-roots level, the elders could recognize how the natives were sometimes using them for what they could get from the Church or the elders themselves. But at the same time the ever-optimistic elders could mistake Tongan hospitality for acceptance of their message. Aupiu wrote,

LDS missionaries traveled to every island, preached in every village, and talked to everyone who would listen. LDS missionary Olonzo Merrill wrote, “Our object is to preach to the people and when we are successful in this we feel better than we do when we get our regular meals and the people are not interested in what we have to tell them. We find the only way to get to talk to them is to go from place to place on foot and stop wherever the people will receive us and talk to them as long as they are anxious to hear.[105]

Then there were the missionaries themselves—strangers in a foreign land. They did not know the language or customs, which were radically different from their own. They had practically no language texts, dictionaries, or grammars to help them learn the language. The network of supportive, loving native members that helped later missionaries learn the language did not exist. An exception was the tutoring that Brother James E. Giles, fluent in Tongan, gave the elders in Ha‘apai. The elders by and large stuck to themselves by often studying the language in their homes and never leaving for days at a time. They felt lucky to be able to do any effective preaching after a whole year of study. They were different from later missionaries such as Ermel Morton, John Groberg, Eric Shumway, Lynn McMurray, or Ralph Olson, who were sent out among the natives and quickly learned the language from loving Tongan companions.

But probably the greatest challenge came from Tongan culture itself. The society was highly structured with deferential respect given to the king, nobles, and other chiefs who held social, political, and economic power over the common people. Therefore, the common people were very reluctant to go against the wishes of the ruling class for fear of ridicule, persecution, and even the loss of their land and livelihood. The common people had social and economic obligations to support the ruling class through traditional ceremonies. Unless the missionaries could get support from Tongan elites, the people would not be willing to join the Church. And these elites, by and large, were already closely linked to the Wesleyan Church or the Free Church, which were also in conflict. Early missionary journals describe situations in which people would apply for baptism after a cottage meeting or gospel discussion. A time was set for their baptism, but they wouldn’t show up. When the elders would follow up, these applicants would say their family, ministers, or chiefs ridiculed them and that they couldn’t face the persecution; however, the seeds were planted in their hearts.

Notes

[1] Brigham Smoot journal, July 15, 1891, Perry Special Collections.

[2] MHHR, August 4, 1891, LR 9197 2, Church History Library. This building still stands and appears as it did in Smoot and Butler’s day.

[3] Kava is a traditional herbal drink made from pounding roots of a tropical shrub. Savani Aupiu notes that drinking kava was a social and ceremonial act used for a variety of social activities. Kava, or Piper methysticum, comes from the dried root of the kava plant that is pounded into a powder and mixed with water. In Tonga it is ceremonially mixed in a wooden bowl and served around a seated circle to greet visitors or to share during social occasions as men discuss various issues or tell stories. Its use was all-important culturally. Savani Latai Toluta‘u Aupiu, “Mormon Missionaries in the Kingdom of Tonga, 1891–1897” (master’s thesis, University of Utah, 2009), 10.

[4] Smoot journal, July 16, 1891, the original spelling is preserved in all journal entries. Smoot recorded translating the Articles of Faith on June 12, 1891. The authors express gratitude to Loretta Nixon, who provided a transcription of the Smoot journals.

[5] Local legislative news told of current happenings in Nuku‘alofa. The authors express gratitude to Ami, chamberlain at the Royal Palace Archives in Nuku‘alofa since 1979, who kindly granted permission to peruse a bound volume at the archive titled “News Clippings.” It contained valuable information being circulated in Tonga during the early 1890s (as Tonga then had no newspapers) that was gathered by a news correspondent based in Nuku‘alofa. He represented the Fiji Times, which was based in Suva.

[6] Alva J. Butler journals, July 16, 1891, Church History Library.

[7] MHHR, August 1, 1891.

[8] Butler journals, November 22, 1891.

[9] Smoot journal, August 7, 1891.

[10] MHHR, August 4, 1891.

[11] Smoot journal, August 20, 1891.

[12] “Far Off Islands: The Tonga Group in Oceania. How the Natives Live. The Valuable Experience of a Provo Boy among a Strange People,” Daily Enquirer, September 9, 1891, transcription by Loretta Nixon, courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

[13] MHHR, August 27, 1891.

[14] Toluta‘u also noted that the Tongan name Hilatali came from a little spring on this property located in Mu‘a. See interview of Viliami Toluta‘u conducted by Fred E. Woods and Martin Andersen, August 12, 2017, in Pangai, Ha‘apai.

[15] Ermel Morton, Brief History of the Tongan Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Golden Jubilee (Suva: Fiji Times, 1968), 2.

[16] MHHR, November 28, 1891.

[17] Morton, Brief History of the Tongan Mission, 3. See also Aupiu, “Mormon Missionaries in the Kingdom of Tonga,” 45–46, and Butler journals, September 11, 1891.

[18] William P. Hunter journal, December 29, 1891, in possession of the authors.

[19] Hunter journal, December 31, 1891.

[20] Hunter journal, January 25, 1892.

[21] Hunter journal, March 24, 1892.

[22] James Kinghorn journal, February 4–5, 1892, in possession of the authors. However, the Kinghorn journal for December 11, 1892, notes that nearly two months earlier, President Lee had already assigned both Kinghorn and Hunter “to learn the Articles of Faith in Tongan” before they left for Tonga.

[23] Hunter journal, July 31, 1892.

[24] Hunter journal, November 28, 1892.

[25] Smoot journal, May 26, 1892. This was the same Mataele that had tutored him in the Tongan language in Samoa.

[26] Olonzo D. Merrill journals, May 29, 1892, in possession of the authors.

[27] Merrill journals, June 1, 1892; Tongan spellings as given.

[28] Hunter journal, June 1, 1892; and Butler journal, June 1, 1892.

[29] Hunter journal, November 14, 1892.

[30] Merrill journals, December 29, 1892.

[31] Merrill journals, July 15, 1892. “The Premier called upon us on his way back to N [Nuku‘alofa]. And I had a long chat with him on different topics among other things I asked him if we could start a school and he said why ‘certainly’, so we have ordered utensils from N.Z.” Smoot, July 23, 1892.

[32] Hunter journal, July 15, 1892; Kinghorn journal, July 15, 1892.

[33] Hunter journal, August 15, 1892.

[34] Merrill journals, August 21, 1892.

[35] Merrill journals, August 31, 1892. Over a year later it was reported, “The school has been very hard to establish for it seems all sects, parties, and power on earth combined against us. . . . For well does he [Satan] know that if we can get those tender minds under our care, even for an hour in the day, we will in time instill principles of truth that cannot be rooted out; for the seed will be sown on ‘good ground’ and will ‘bring forth fruit.’” See “In the Warm South Seas,” Deseret News, November 14, 1893.

[36] Merrill journals, January 24, 1894. Aupiu, “Mormon Missionaries in the Kingdom of Tonga,” 43, points out that William was the youngest son of Tuku‘aho.

[37] Merrill journals, October 5, 1892.

[38] Merrill journals, August 7, 1892. The major Christian churches in Tonga at this time were the Catholic, the Wesleyan Church, and the Free Church of Tonga, which was most closely aligned with the monarchy.

[39] Smoot journal, September 16, 1891.

[40] Merrill journals, May 31, 1893.

[41] Merrill journals, November 15, 1894.

[42] Merrill journals, September 11, 1892. Concerning this event, William Hunter noted, “To my great joy saw Bro. S. [Smoot] leading Alabate into the water. The first time he did not get burried but the second was alright.” See Hunter journal, September 18, 1892.

[43] Kinghorn journal, September 11, 1892.

[44] Merrill journals, September 25, 1892.

[45] Merrill journals, November 13, 1892.

[46] Hunter journal, November 14, 1892.

[47] Butler journals, October 24, 1892)

[48] Hunter journal, October 24, 1892.

[49] Butler journals, February 3, 1893.

[50] Merrill journals, February 7, 1893.

[51] Merrill journals, February 7, 1893.

[52] Merrill journals, April 15, 1893. Butler noted, “Besides the mail Bro M brought a new missionary with him. Bro A. M Durham of Parowan age—and told us there were three more in N [Nuku‘alofa]. two Sisters and a man. We are greatly surprised for we did not expect them until next month and then we did not expect two sisters for we are not fixed very well for them.” Butler journals, April 15, 1893.

[53] Merrill journals, April 15, 1893.

[54] Thomas D. Adams journals, April 16, 1893, Church History Library.

[55] Merrill journals, April 15, 1893.

[56] Kinghorn journal, May 30–31, 1893.

[57] Kinghorn journal, May 7, 1893.

[58] Hunter journal, May 7, 1893.

[59] Hunter journal, June 14, 1893.

[60] MHHR, August 1893.

[61] MHHR, December 31, 1893.

[62] Kinghorn journal, December 31, 1893.

[63] Kinghorn journal, February 12, 1894.

[64] In Tonga there were no undertakers, no mortuaries, and no refrigeration. Corpses would begin to decompose within hours. Hence, burials had to take place within twenty-four hours of death.

[65] Aupiu, “Mormon Missionaries in the Kingdom of Tonga,” 36.

[66] Albert Stephen Jones diary, July 22, 1894.

[67] Eric B. Shumway, comp., Tongan Saints: Legacy of Faith (Laie, HI: Institute for Polynesian Studies, 1991), xiii.

[68] Jones diary, December 9, 1894.

[69] Jones diary, December 12, 1894.

[70] MHHR, December 31, 1894.

[71] Perhaps young Tungī was one.

[72] See Reid L. Neilson and Riley M. Moffat, eds., Tales from the World Tour: The 1895–1897 Travel Writings of Mormon Historian Andrew Jenson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 113–39.

[73] Andrew Jenson to the Deseret News, written August 24, 1895, from Nuku‘alofa, Tonga. This site was recently memorialized as noted by the Mormon Historic Sites Foundation. See http://

[74] Andrew Jenson to the Deseret News, written August 24, 1895, from Nuku‘alofa, Tonga. Jenson also mentions meeting at Mu‘a a baptized member from Ha‘apai he calls Salesi Tanogamolofiaivailahi.

[75] Neilson and Moffat, eds., Tales from the World Tour, 135.

[76] Charles Jensen journal, September 9, 1895, Church History Library.

[77] “Andrew Jenson’s Travels,” letter 30, written September 13, 1895, Deseret News January 4, 1896, 81–83. The dedicatory prayer was offered September 9, 1895. See also Nielson and Moffat, Tales from the World Tour, 136.

[78] Vika, along with all of Olsen’s family in Tonga, would die of the Spanish influenza in Nuku‘alofa in November 1918, and Vika was buried between Elder Proctor and Elder Langston in the Telekava, Nuku‘alofa, cemetery.

[79] Jensen journal, January 15, 1896.

[80] Alfred A. Kofoed mission journals, August 9, 1896, Perry Special Collections.

[81] Namosi’s first cousin Iki Tupou, who greeted the returning elders in 1907, ended up getting the title.

[82] Jones diary, July 30, 1896.

[83] Kalauta later sold some horses to Samoan Mission president Thomas Court in 1907. This transaction initiated the return of the missionaries to Tonga.

[84] Tevita Ka‘ili, “Ta e Fihi: Clear a Path for the Lord’s Work” (BYU–Hawaii devotional, April 5, 2007).

[85] Kofoed mission journals, July 5, 1895.

[86] Kofoed mission journals, March 7, 1895.

[87] Kofoed mission journals, December 3, 1895.

[88] Jensen journal, December 4, 1896.

[89] Jones diary, December 4, 1896.

[90] Kofoed mission journals, December 4, 1896.

[91] Kofoed mission journals, July 10, 1896.

[92] Kofoed mission journals, February 7, 1897. In 1907 Namosi offered Elders William Facer and Heber McKay his own house in which to hold their first school.

[93] Kofoed mission journals, December 24, 1896.

[94] James R. Welker and Robert A. Smith, “From the South Seas: Elders Visit a Number of the Islands Forbidden to Preach on Some Leaky Ship,” Deseret Evening News, February 27, 1897, 12. Newspaper clipping from Kofoed mission journals, 1897. See also Lorraine Morton Ashton collection relating to Ermel J. Morton, 20th-Century Western and Mormon Americana, Perry Special Collections, 7–9 (hereafter cited as Morton notes). These are notes Ermel J. Morton made when he prepared his Brief History of the Tongan Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1968. They appear similar to the manuscript history of the Tongan Mission in chronological order and are partly typewritten and partly handwritten. The authors thank Lorraine Morton Ashton for making them available.

[95] This failure to follow through with baptism after conversion is discussed in Aupiu, “Mormon Missionaries in the Kingdom of Tonga,” 36–39.

[96] Jensen journal, February 18, 1897.

[97] Kofoed mission journals, January 21, 1897. This is the same amount it cost to build Hilatali.

[98] Kofoed mission journals, March 17, 1897. Jacob Olsen was a great friend to the elders until his death October 13, 1936, at Tefisi, Vava‘u.

[99] Samoan Mission Manuscript History and Historical Reports, 1863–1966, October 31, 1901, Church History Library.

[100] Jones diary, December 4, 1896; see also Jensen journal, December 4, 1896.

[101] Kofoed mission journals, April 6, 1897.

[102] Aupiu, “Mormon Missionaries in the Kingdom of Tonga,” 49–50.

[103] Aupiu, “Mormon Missionaries in the Kingdom of Tonga,” iv, 26. The reason for the failure of the mission was a combination of opposition from other churches as well as lack of support from King George Tupou I and other Tongan elites who feared the possibility of political takeover by foreign powers that had swallowed up other islands in the region (52). In reality, Tonga had no reason to fear the U.S. and the Tongan missionaries (46).

[104] Aupiu, “Mormon Missionaries in the Kingdom of Tonga,” 49–51.

[105] Aupiu, “Mormon Missionaries in the Kingdom of Tonga,” 33.