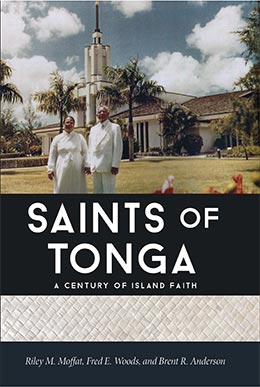

Liahona, the Labor Missionaries, and Preparing for Temple Blessings (1950-59)

Riley M. Moffat, Fred E. Woods, and Brent R. Anderson, "Liahona, the Labor Missionaries, and Preparing for Temple Blessings (1950-59)," in Saints of Tonga (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 199–254.

The decade of the 1950s was the turning point in the history of the Church in Tonga. The Church went from a small, poorly understood religious body to a major force in the kingdom’s religious fabric. From meeting in a few small wooden chapels and Tongan fale to meeting in dozens of fine concrete block chapels in many villages, the Church made tremendous progress during this period. Church education also developed from a humble little secondary school out in Makeke to the finest school complex in the country at Liahona College.[1] The physical growth provided the government with a large portion of its income from import duties on materials, and the Saints’ spiritual growth during these years prepared them for the eventual blessings of the temple. Liahona and the many fine new chapels made the Saints proud to be members of the Church. By the end of the decade they felt they were no longer looked down upon as an insignificant and strange religion. It encouraged more people to take the gospel message the missionaries were sharing more seriously. The annoyance of government restrictions and petty harassments of other churches seemed to work more for the Church’s benefit than to its detriment.[2]

Labor Missionary Program Started

President Emile Dunn had his hands full supervising the mission as well as the construction of Liahona. Elder Matthew Cowley called his friend Lionel C. Going, an experienced builder from California, and his wife, Norma, on a mission to help build Liahona. They arrived in Tonga on May 17, 1950.[3] A few weeks after the Goings’ arrival, President Dunn turned over the Liahona project to him, and a month after that President Dunn was replaced by Evon Huntsman on July 12, 1950, the same person who had completed Dunn’s earlier term as mission president. This was the second time in four years that Huntsman had come to replace Dunn. By this time Emile Dunn had served thirteen years in Tonga. The Dunns even returned in the 1980s as senior missionaries to teach at Liahona.

Because of the strict missionary quota, the Goings, like other subsequent expatriate building missionary supervisors, were allowed into Tonga so long as they did not do any proselytizing. However, they did visit various branches each Sunday to preach and work with branch leaders. They were also able to socialize with members of the Church and other faiths throughout the country and plant seeds for the proselytizing missionaries to harvest.

After their arrival in Tonga, President Huntsman and Brother Going reasoned they needed to call local priesthood brethren to help the eight expatriate skilled supervisors building the Liahona school. Huntsman recollected,

Elder Going and I had several meetings and decided to call fifty strong, able bodied members of the Priesthood quorums, to accept a call to work on the school, until finished and request that a plumber, a cement man, an electrician, and two carpenters be called from Zion. I called a General Priesthood meeting and told them I was acting in accord with the wishes of the First Presidency and we needed fifty men to volunteer to work as labor missionaries. There were some 250 members present and when I asked for 50 they all raised their hands—many were old and crippled. We selected 50 out of the group and set them apart as Labor Missionaries, to work until the school was completed. Elders Hansen and Weiss, from Salt Lake City and Elders Clark, Hapeta, and Elkington, soon arrived and each took ten natives and went to work under Elder Going. They were the first Work Missionaries called in the Church.[4]

This happened on September 17. Not long after, Elder George Biesinger paid a visit from New Zealand to inspect the project at Liahona and possibly get some ideas for the new Church schools being planned for Pesega, Western Samoa, and in New Zealand. Governor ‘Ahome‘e and other members of Parliament from Ha‘apai and Vava‘u also came out to Liahona and were surprised and amazed at the size of the project.

Elder Cowley had called some skilled builders from Vava‘u to come work at Liahona in 1947. [5] These men, such as Iohani Wolfgramm, had helped build the chapels at Neiafu and Ha‘alaufuli in 1938. However, President Dunn had “emphatically” said the idea of using labor missionaries “would never work with the Tongan people.”[6] Yet the new building supervisors, President Huntsman and Brother Going, moved their families to Liahona to begin the labor program. “And so, handicapped by unskilled labor, shortages of materials, equipment and food, the labor missionaries of Tonga proceeded to build their school.”[7] Their home branches and the plantation provided their food. The building missionaries acquired valuable skills, and Brother Going said there were never any quarrels.[8]

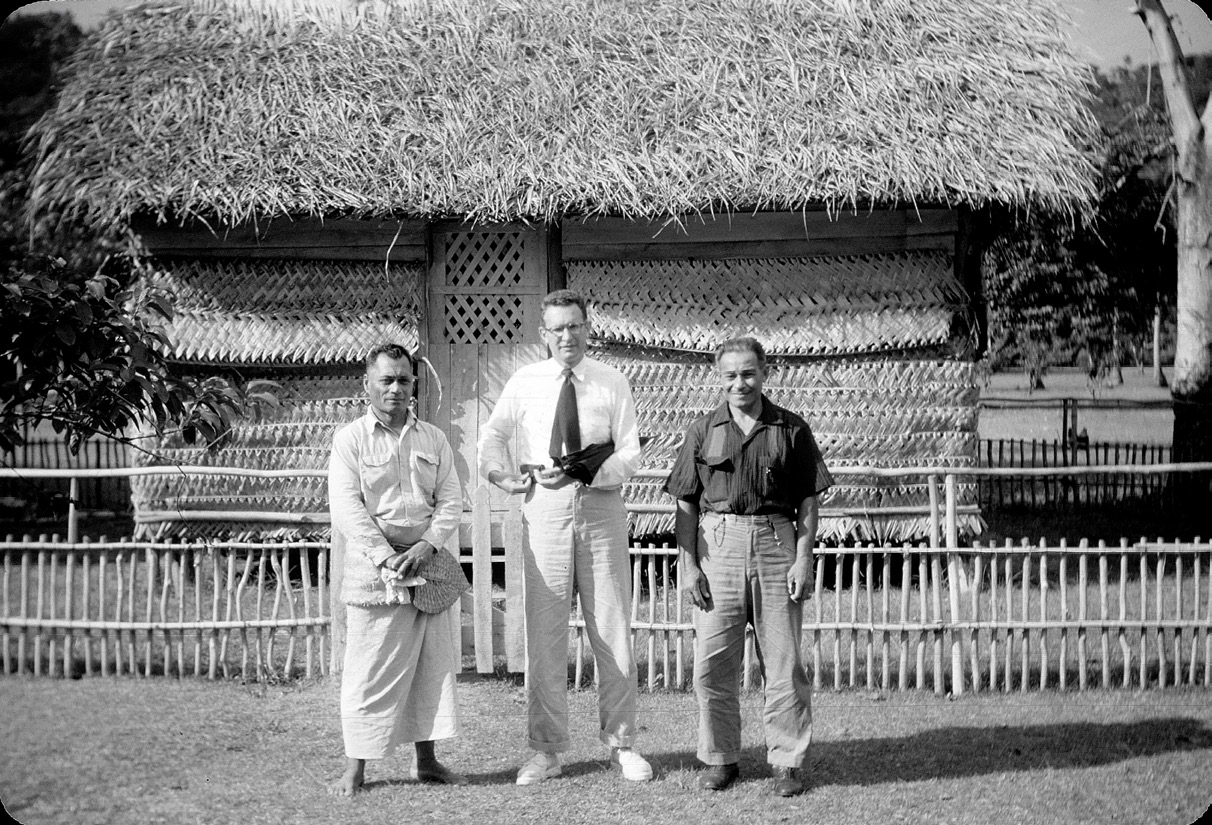

President Evon Huntsman and his counselors Samuela Fakatou and Alex Wishart. Lorraine Morton Ashton.

President Evon Huntsman and his counselors Samuela Fakatou and Alex Wishart. Lorraine Morton Ashton.

David Cummings wrote, “Elder Going and his wife lived at Liahona. The other Zion Elders lived at Nuku‘alofa and drove out to the project each morning in an old jeep. . . . At frequent intervals before going to work, the missionaries had to drive down to the dock at Nuku‘alofa at 4am to pick up the food that came by boat from the branches on the other islands. If they were not on the dot, someone else would make off with the food.”[9]

The cargo of any ships arriving from the United States consisted largely of building materials for Liahona. Whenever they arrived, the Saints mobilized all the trucks they could find to load and transport the materials to the building site in record time, to the amazement of the government and all onlookers. Getting the tons of building materials from the dock to Liahona without getting rained on should have been a problem, but the Lord was known to intervene.

President Huntsman selected Alex Wishart as his first counselor and Samuela Fakatou as second counselor. Elder J. Layne Black, a proselytizing missionary, was assigned to be the principal of Liahona College. By the end of 1950, the large temporary Tongan fale built in 1947 at Liahona were not expected to last another year. In December 1950, President Huntsman closed the school to wait until the new Liahona College buildings were ready. However, though the classrooms were not yet finished, school started up in Tongan fale for seventy to eighty students of Forms 4–6 on March 21, 1951. School for the hundred students in forms 2–3 didn’t start until August. That same month, James Elkington and James Hapeta with their wives arrived from New Zealand to work as construction supervisors on the Liahona campus. Construction of the permanent campus was completed by the end of 1951. It was estimated that the cost of construction was $300,000 in currency. In the meantime, Ermel Morton and his family arrived on February 20, 1951, to organize the new college and prepare it to open. He was called as a teaching missionary and was not counted against the government’s missionary quota. Many others called from America were to follow.

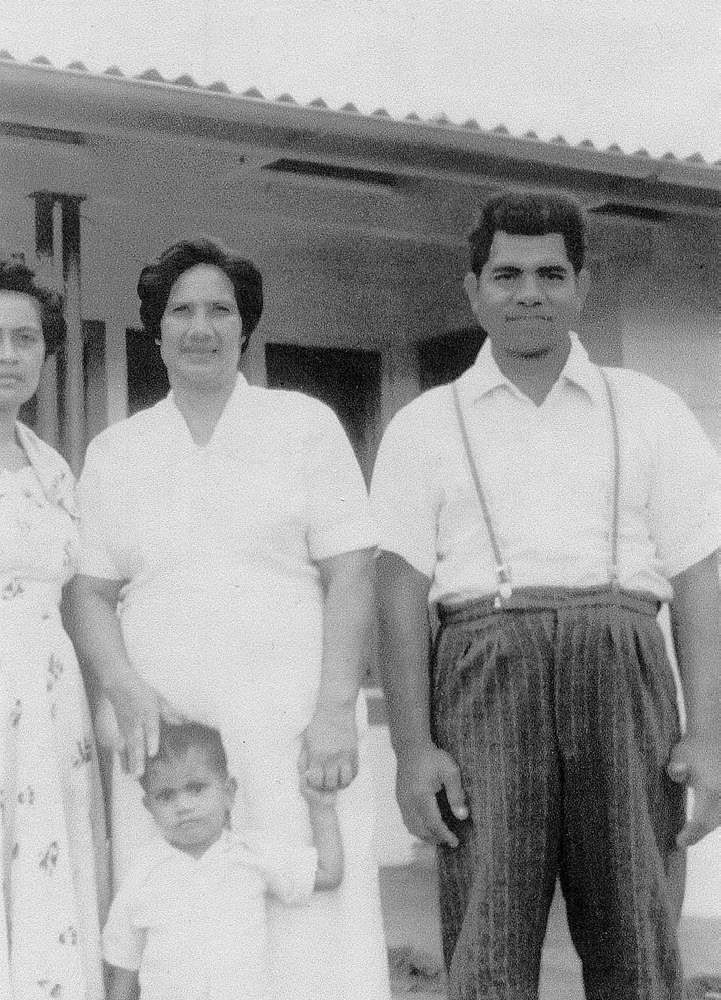

Ermel J. Morton and family. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton

Ermel J. Morton and family. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton

Ashton.

The focus on building Liahona caused proselytizing in the mission to practically cease. Mele Taumoepeau observed that the time and effort that was lost in proselytizing was more than made up for when Liahona became the best missionary tool the Church had in Tonga. Principal Morton noted, “Such a large project has drained most of the available manpower of the approximately 3000 members of the Church, and as a result many priesthood members who would normally be available for missionary work have been available for building. . . . Native missionaries have filled the breach to do missionary work.”[10] This meant that most active males were either laboring at Liahona or serving a mission.

During construction a number of important government officials came to inspect the project. On November 20, 1951, Prince Tungī visited and was “rather awestruck with the modern construction and equipment.”[11] At the end of 1951, as construction of Liahona was coming to an end, President Huntsman reported to Salt Lake: “I have called and set apart twenty new local missionaries and sent them to all five of the main islands of the mission, instructing them that they are to spend all the time possible in carrying the Gospel message to everyone who will accept it!”[12]

D’Monte Coombs Replaces Evon Huntsman

President D’Monte Coombs and his counselors Samuela Fakatou and Lisiate Talanoa. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

President D’Monte Coombs and his counselors Samuela Fakatou and Lisiate Talanoa. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

About this same time, Sister Huntsman was afflicted with a serious tropical disease and needed to return to the United States. D’Monte Coombs and his wife, Joan, previously called as teaching missionaries at Liahona, had their call modified, and he was appointed and set apart December 2, 1951, as the new mission president.[13] Coombs had grown up in Tonga while his parents presided over the mission from 1920 to 1926. President Coombs was thirty-one, and his wife, Joan, a decade younger. One of his first acts was to organize a translation committee consisting of Samuela Fakatou, William Sovea, Semisi Taumoepeau, Elder Tupou, and Elder Hansen. Beforehand, the translation of Church materials from English to Tongan was generally done by the mission president’s wife and various elders who had acquired some proficiency in the language. President Coombs chose Lisiate Talanoa and Samuela Fakatou to be his counselors. In March President Coombs instructed the district presidents to reorganize their branches as needed with local brethren to preside, thereby freeing the missionaries to spend more time proselytizing.[14] As young mothers, Sister Coombs and Princess Mata‘aho, Prince Tungī’s wife, became “quite friendly” and regularly visited each other.[15] This did not sit well with many hou‘eiki (nobles and other elites), so visits were kept discreet.

Faculty at Liahona in 1954. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Faculty at Liahona in 1954. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

The 1952 school year opened with over two hundred students, 35 percent of whom were members of other faiths. Many students, such as fifteen-year-old Fane Fale, were baptized during the year. With their work done, the Goings reported their service in Tonga to authorities in Salt Lake City and then moved on to Samoa in September to labor on the facilities of the Church College of Western Samoa. In November Bishop Carl W. Buehner of the Presiding Bishopric, New Zealand Mission president Sidney Ottley, and Church architect Edward O. Anderson arrived to inspect the newly completed campus at Liahona. Bishop Buehner described Liahona as “the greatest missionary in the islands.”[16] He also had a pleasant audience with Queen Salote, who was on her way to attend the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in London. Bishop Buehner invited her to attend the upcoming dedication of Liahona, and Her Majesty requested that it be held off until she returned. Though the campus was completed, its dedication was postponed until the following year when some other buildings were completed in the Pacific and a General Authority could be scheduled to visit all the newly completed projects. The first graduation ceremony at Liahona was held on November 26. Also, on December 16, 1952, Church pioneer Iki Tupou Fulivai died at age one hundred.

For the 1953 school year, President D’Monte Coombs received permission from the government to bring in eight professional teaching missionaries from America who would not count against the official quota of three proselytizing missionaries.These included Patrick and Lela Dalton and Kenneth Lindsay. The first weeklong missionary training program was held at Liahona for sixteen newly called local missionaries in September. This same year Liahona also began using the same entrance exam as the other secondary schools in Tonga.

Dedication of Liahona

Liahona teachers in ca. 1952. Courtersy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Liahona teachers in ca. 1952. Courtersy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

The new campus was dedicated by Elder LeGrand Richards on December 2, 1953. As Elder Richards, accompanied by Evon Huntsman and his party, approached Liahona, they found many students lined up on each side of their path; the band played “We Thank Thee, O God, for a Prophet,” followed by the Tongan national anthem. Elder Richards was presented with a puaka ha‘unga (a large ceremonial roast pig) on the field in front of the campus.

Lela Dalton recorded,

One of the most impressive parts was when a film in color was presented during the program in which President McKay, sitting at his desk, gave a very warm and friendly greeting to the people, giving special recognition to Queen Salote. McKay said he would like to have visited them in person, but due to other appointments couldn't make it. He recalled his trip to Tonga thirty years before and mentioned the various things which impressed him then. Among other things, the President counseled the Tongan Saints to “cultivate those virtues which would contribute to their salvation.”

We heard afterwards that several men were astonished when the film came on—they kept saying “It’s a real man. No, it couldn’t be; he doesn’t have any legs. But what is it? Isn’t it wonderful! Must be television from America. Isn’t this church doing great things!”[17]

President and Sister Coombs with Elder LeGrande Richards greet Liahona students. Ross Bulkley collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

President and Sister Coombs with Elder LeGrande Richards greet Liahona students. Ross Bulkley collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Queen Salote also attended, along with Crown Prince Tungī, Prince Tu‘ipelehake, and their wives, Princess Mata‘aho and Princess Melenaite. The queen cut a ceremonial ribbon and spoke to the people. She expressed her feelings that the dedicatory ceremony was a joyful event, that happiness comes from achieving, and that the school and the dedication were a representation of achievement. The queen explained, “The objective of founding this school is to build up and encourage Christian civilization among the Tongan people and the world.” Elder Richards told the assembly, through his interpreter, Ermel Morton, that he was grateful the Church could supply the Tongans with the Liahona school. He also mentioned the Latter-day Saint belief that “the glory of God is intelligence” and noted that education would help humankind become like God.[18] Uai Fa had composed a special song, “Liahona,” that was then sung. It was a rainy day, but nothing could interfere with the excitement of the occasion. A mammoth outdoor feast was prepared but was rained out, so the invited guests ended up eating in the auditorium with the queen’s pola (feast) set up on the stage.[19] Later that month newly crowned Queen Elizabeth II paid a visit to Tonga as part of her worldwide tour of Commonwealth countries. Some of Queen Elizabeth’s staff were billeted at the mission home at Matavaimo‘ui and given a tour of Liahona.

With the dedication of Liahona College, the first phase of the labor missionary program in Tonga was complete. It had lasted from 1950 to 1952. It would be resumed in January 1956, but on a much broader scale.[20]

Developments after the Dedication

President D’Monte Coombs with Elder LeGrande Richards and Evon Huntsman inspect a puaka toho. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

President D’Monte Coombs with Elder LeGrande Richards and Evon Huntsman inspect a puaka toho. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

President Coombs opened up several small islands in Ha‘apai and Vava‘u to missionary work. On February 18, 1954, President Coombs shared several Church films with the royal family at the British consul’s home. He decided to clean up the membership records of the mission. Besides finding members who had died or moved, he found a number who needed disciplinary action for apostasy, adultery, and fornication. Previously, mission leaders had been counseled by Church headquarters in Salt Lake City to be lenient with the native members as they became accustomed to living the Church’s doctrines regarding such things as the law of chastity, Word of Wisdom, and law of tithing. President Coombs, however, felt inspired to act, calling members to repentance and excommunicating several, including the mission’s largest tithe payer, which prompted several other members to come forward to confess their wrongdoings. He recalled that he held three hundred disciplinary councils from 1953 to 1955 and excommunicated one hundred people.[21] A number of unmarried couples decided to get married. Many of those disciplined eventually heeded his counsel, repented, and returned to Church activity. Some thought his actions were harsh, but in the long run it helped prepare the Saints in Tonga to be worthy to attend the temple when the opportunity came.

To free more missionaries for proselytizing, Coombs reorganized many branches by installing local members as branch presidents instead of missionaries. Throughout all these years, the government continued to restrict the number of foreign missionaries to three, so the bulk of missionary work fell to native Tongans. President Coombs began calling young married men to six-month missions to assist with missionary work, along with a few married couples who were called to lead some of the weaker branches. Other adjustments were made to the missionary program to reflect Tongan cultural values. However, the finest missionary tool the mission had was Liahona College, where many students were baptized each year.

President Coombs wanted the Tongan Saints to become more familiar with the Book of Mormon. At a mission conference, he asked those assembled how many had read the Book of Mormon; only he, his wife, and Elder Morton raised their hands. Then he counseled the members to use the Book of Mormon in all their gospel study and preaching. He also wanted the mission to be self-supporting. One way was to feed all the students at Liahona from the school farm. There teaching missionary Elder Patrick Dalton developed a herd of milk cows and taught students how to milk them.

The island of Niue, situated two hundred miles east of Vava‘u, had been opened to missionary work from New Zealand in 1952. At the recommendation of the First Presidency, on July 25, 1954, Presidents D’Monte Coombs of the Tongan Mission, Sidney Ottley of the New Zealand Mission, and Howard Stone of the Samoan Mission met in Suva, Fiji, and transferred Niue from the New Zealand Mission to the Tongan Mission, which made Niue more accessible to visits by Church leaders because of transportation schedules. At the same time they decided it was time to open Fiji for missionary work, starting with the small branch that had been organized earlier in Suva and putting it under the Samoan Mission.[22]

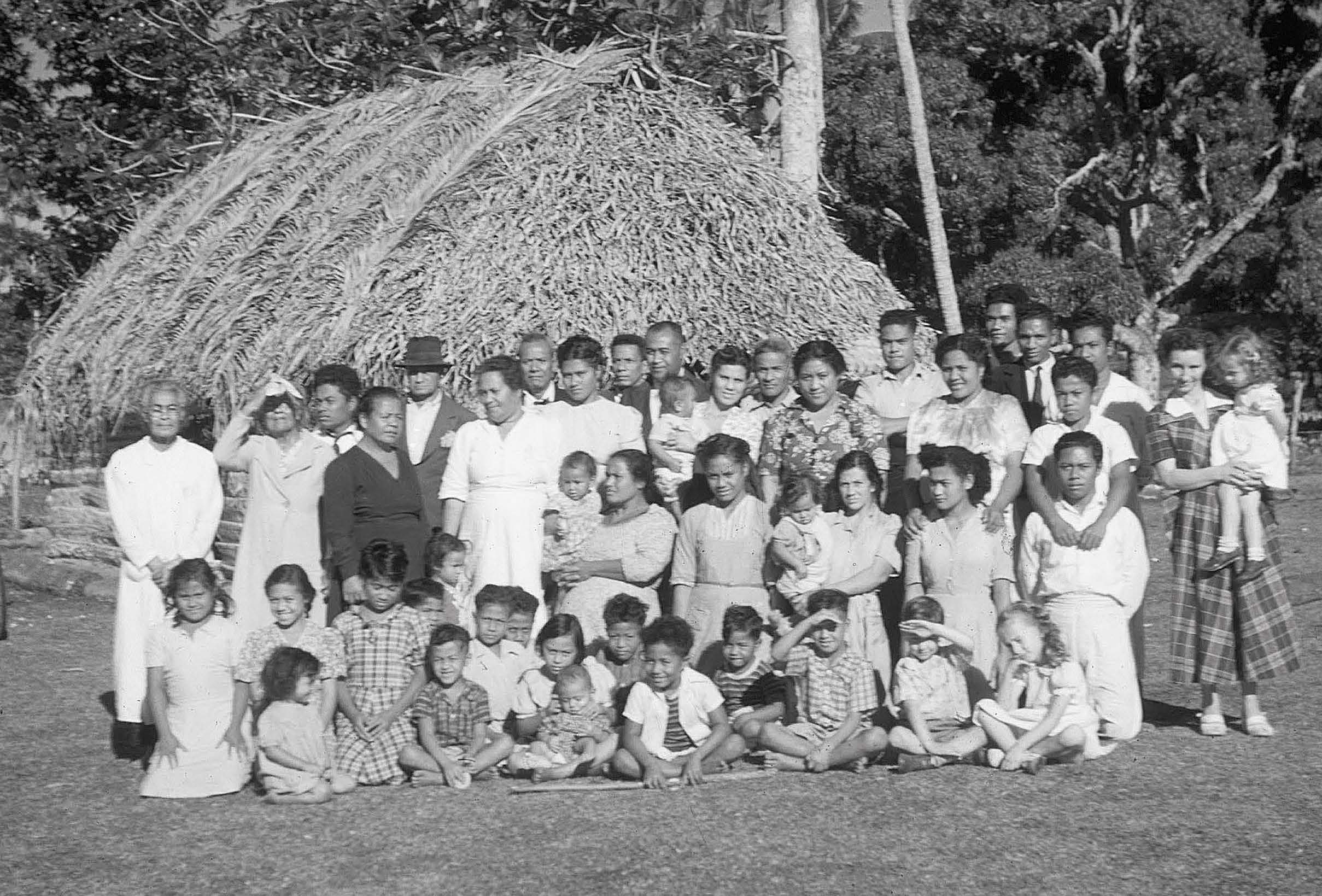

Nukunuku Branch 1952. Ermel J. Morton Collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Nukunuku Branch 1952. Ermel J. Morton Collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

At Liahona in 1954, Brother Ermel Morton, the principal of the school and also a distinguished linguist, completed and published an English–Tongan dictionary for the Tongan Department of Education. In his spare time Brother Morton, who had years before translated the Book of Mormon into Tongan, completed the translation of the Doctrine and Covenants and Pearl of Great Price into Tongan, which was reviewed by ‘Atonio Tui‘āsoa and Viliami Sovea Kioa. These scriptures were eventually printed and made available in 1959.[23]

On October 6, 1954, missionary teachers Ronald Peck and Kenneth Lindsay initiated a program of Liahona students entertaining passengers from the Union Steamship Company’s ships Tofua and Matua that regularly stopped at Nuku‘alofa. The students danced, sang, and offered handicrafts for sale at the Liahona campus. The show included the Joseph Smith lakalaka (group dance) composed by Muli Kinikini and a ma‘ulu‘ulu (seated group dance) describing the establishment of Liahona. This program was apparently modeled after the hukilau program put on for tourists in La‘ie, Hawai‘i, and was a tremendous opportunity to introduce the Church to visitors. The Tongan Saints who were responsible for various aspects of the program and activities were Fine Taufa, Muli Kinikini, Fa‘alupenga Sanft, and ‘Atonio Tui‘āsoa as the dance instructors with ‘Atonio Tui‘āsoa and Fa‘alupenga Sanft in charge of the Tongan crafts.[24] Their show also demonstrated dances from other islands such as Tahiti and Hawai‘i, and featured dances from the Maori of New Zealand. This show was enhanced by students sent from Tahiti, and later Fiji, and may have been a model for what later became the Polynesian Cultural Center night show, which a few of these students, such as Kalolaine Mataele and Nanasi Fine, were a part of.[25]

Liahona College had its own student branch in which all the branch positions except for the branch president were held by students. The students in the dorms were formed into families of six for branch activities like home teaching, just like wards elsewhere in the Church.[26] This gave students hands-on training in Church leadership, which was a great benefit in later years to the students.

New Chapels Approved

With the college completed, President Coombs believed it was time to replace the many little wooden and thatched chapels with new concrete block chapels since a corps of skilled workmen who had built Liahona resided in the country. But which branches most deserved new chapels? As he considered this question, it was difficult to determine which villages should receive one. Eventually, Coombs told the branches that to get a new chapel they would need to raise about £200 and provide labor equivalent to about one-third the cost of the chapel; the Church would then furnish the materials. Remarkably, the Tongan locals were very faithful in following through on this plan.[27] In the end President Coombs proposed to Church headquarters that twenty-one chapels be built.

On December 14, 1954, approval was received to build all twenty-one chapels with the understanding that local Saints would provide all the labor. New building missionaries were to be called and set apart, along with some American supervisors who were to be sent to supervise the construction of each chapel. The newly approved chapels to be built were in Nuku‘alofa, Neiafu, Pangai, Kolonga, Mu‘a, Veitongo, Vaini, Fua‘amotu, Tu‘anuku, ‘Otea, Ha‘alaufuli, Leimatu‘a, ‘Uiha, Ha‘akame, Fo‘ui, Tokomololo, Nukunuku, Matahau, Houma, Vaipoa, Tongamama‘o, and Alofi. Morton noted, “At a meeting on January 31 the mission presidency decided that each branch where a chapel was to be built should raise a building fund of £500, also to feed the workers and do much of the work themselves without pay.”[28] These projects lasted for several years because it often took a few years to arrange leases for the chapel sites.

Visit of President David O. McKay and Vision of a Temple

A landmark event occurred in January 1955 when Church President David O. McKay and his wife, Emma, stopped in Tonga for three days on their way to New Zealand, where he would inspect the construction of the Church College of New Zealand and announce the building of a temple there. His visit came with just twenty-three days’ notice. This visit was in stark contrast to the visit he made in 1921. Instead of being quarantined on trumped-up charges, he was welcomed with crowds of faithful Saints singing “We Thank Thee, O God, for a Prophet.” At Liahona he walked from the road to the college between lines of uniformed students on a path covered in ngatu (tapa cloth) and was “honored with a ha‘unga ceremony and royal kava ceremony reserved to honor kings and queens.”[29]

Arch welcoming President and Sister David O. McKay to Liahona College. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Arch welcoming President and Sister David O. McKay to Liahona College. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Afterward, President McKay asked to visit Makeke. Some members of the Church and of other faiths approached him on their knees as they would the queen. Prince Tungī and other members of the royal family were on hand to greet him. He was very interested in the success of Liahona College, remembering that he had given permission in 1921 to seek a site for what became Makeke College. This time he was so impressed with what he saw at Liahona that he encouraged the school to seek more funds to expand the college’s facilities beyond the current capacity of 250 students, with seven expatriate missionary teachers and six Tongan teachers.[30] After a grand feast for 1,500, at which President McKay sat on the ground with the people, a gesture very endearing to them, he spoke in the Liahona auditorium and emphasized the importance of every member being a missionary in all seasons. Sister Lela Dalton, a missionary teacher at Liahona who knew shorthand, recorded all his sermons. He stated, “God bless the 250 students, that wherever you go you be a credit to the Liahona school of the Church.” President McKay told the Tongan youth that they could be trusted to carry the gift of the gospel to the world.”[31] Before the prophet left Tongatapu, he stated, “It was a wise church policy to establish schools as this is the way to win the souls of people. If you get them while they are young and bring them up in the truth, then when they are older, they will not depart from the way.”[32] The next day President McKay went to the palace to meet with Prince Tungī.

Tapa covered path leading into Liahona College. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Tapa covered path leading into Liahona College. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

President McKay went to Vava‘u aboard the Tofua but was only able to stay half a day. Lela Dalton recorded this experience: “Arrived early the next morning at Neiafu, Vava‘u. The saints were on the wharf to greet us with a choir. Island governor, ‘Ahome‘e, Crown Prince Tungī’s father-in-law, was there to meet Pres. McKay. They rode in a truck, only available vehicle, to Ha‘alaufuli, . . . to see the chapel there.” In his talk at Neiafu on January 13, 1955, President McKay said, “During that visit [in 1921] we took a drive that we repeated this morning over to the spot where the Church of Jesus Christ was born in Vava‘u, Ha‘alaufuli.”[33]

President McKay also shared the story of a faithful sister from Vava‘u named Martha Wolfgramm who was very patient with her husband, giving him time to receive his own testimony.[34] Sister Dalton noted, “Returning to Neiafu for another feast for 1,500 and program, after which Pres. McKay spoke in a meeting. During this talk in the chapel, which I was recording, Pres. McKay made the statement, ‘Today in vision I saw a temple in these islands.’ I could hardly believe he meant these tiny, tiny islands of Tonga. Since they were on their way to New Zealand to dedicate the ground for the building of a temple there, I thought to myself that surely, he must mean New Zealand.”[35] Ermel Morton, who translated for President McKay, remembered him saying, “Do you know what I saw today in vision?—a temple on one of these islands where the members of the Church may go and receive the blessings of the temple of God. You are entitled to it.”[36]

In 1980 D’Monte Coombs recalled that as they sailed from Vava‘u to Samoa with President McKay in 1955, “I asked him what he meant. He said, ‘For now we are looking at a temple in New Zealand that will serve all the islands.’” Then he told Coombs, “But in a couple of years they will have a temple close to Liahona.”[37]

President D’Monte Coombs, President David O. McKay and Elder John Groberg at Liahona College. Ross Bulkley collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

President D’Monte Coombs, President David O. McKay and Elder John Groberg at Liahona College. Ross Bulkley collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Also on this occasion, President McKay surveyed the Church compound at Ha‘alaufuli with the little 1912 wooden chapel, the social hall, and the elders’ cottage. He suggested President Coombs ask for funds to add recreation halls to all the chapels that had been authorized so the Saints in Tonga would have access to all the resources the Saints in Zion had.[38] “Pres. McKay said he wanted the chapels to have recreation halls. “I want you to write Salt Lake and tell them that you want 21 recreation halls to go with those chapels. The time has come for the people of the islands to have all the blessings of the Church that the people of the Wasatch Front have.”[39] As a result of this request, the mission received authorization on April 12 to build recreation halls for seventeen of the new chapels, as well as a new industrial arts building at Liahona.

The next day the McKays stopped at Niue. However, the seas were very rough and the Tofua had to anchor offshore. President McKay asked to take a boat ashore, but the captain said it was too dangerous. The three missionaries on the island did make it out to the Tofua and visited with President McKay, but they all got soaked and one was injured getting back to shore.

Crown Prince Tungi with President and Sister McKay. Lela Dalton collection courtesy of Eric Shumway.

Crown Prince Tungi with President and Sister McKay. Lela Dalton collection courtesy of Eric Shumway.

Because of President McKay’s visit to Tonga, Prince Tungī was invited to Salt Lake City and Brigham Young University in May 1955 to get a better understanding of the Church’s programs.[40] The prince was given the royal treatment as he toured Utah. In Salt Lake the prince met with eighty-eight former missionaries and was shown around Temple Square by President McKay, where Prince Tungī, an accomplished pianist, played the Tabernacle organ with organist Alexander Schreiner. President McKay also hosted the prince at his home in Huntsville. Apparently, Prince Tungī was suitably impressed and promised landing permits for the construction supervisors and their families that were needed to lead the building of all the new chapels being planned, though arranging leases from the government for the chapel sites still took much time.

President David O. McKay and President D’Monte Coombs visit Ha‘alaufuli chapel. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

President David O. McKay and President D’Monte Coombs visit Ha‘alaufuli chapel. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

When school started at Liahona College on February 7, 1955, there were 237 students enrolled, with 172 still waiting to find boats that could bring them to Tongatapu. This was up from 191 students in 1954. “To prepare Tongan youth to better earn a living” in Tonga after graduation, a vocational division was established in June to teach agriculture, forestry, fishing, and mechanics, and a girls’ division to teach domestic arts was started.[41] This was also part of an effort to coordinate Liahona’s curriculum to conform to the government curriculum.

Sometime previously, President Huntsman had requested new band instruments and new green and white uniforms that the band wore for the first time in the June 25, 1955, parade for the opening of Parliament. Liahona was the first school band in Tonga to have uniforms. The contingent included a color guard, baton twirlers, and a strutting drum major. This astonished both Tongans and Europeans alike. The queen commented that it was like a band from another country.[42]

That year there were nine expatriate teachers and ten Tongan teachers at Liahona. President Coombs recognized the value of Liahona for missionary work; therefore, he made certain that it received all the resources it needed.[43] President Coombs thought Ermel Morton was a “godsend” to be able to accomplish all he did.[44] The Church in Tonga went from second class to a league of its own.[45] By 1955 the Church had spent $600,000 in building Liahona.[46]

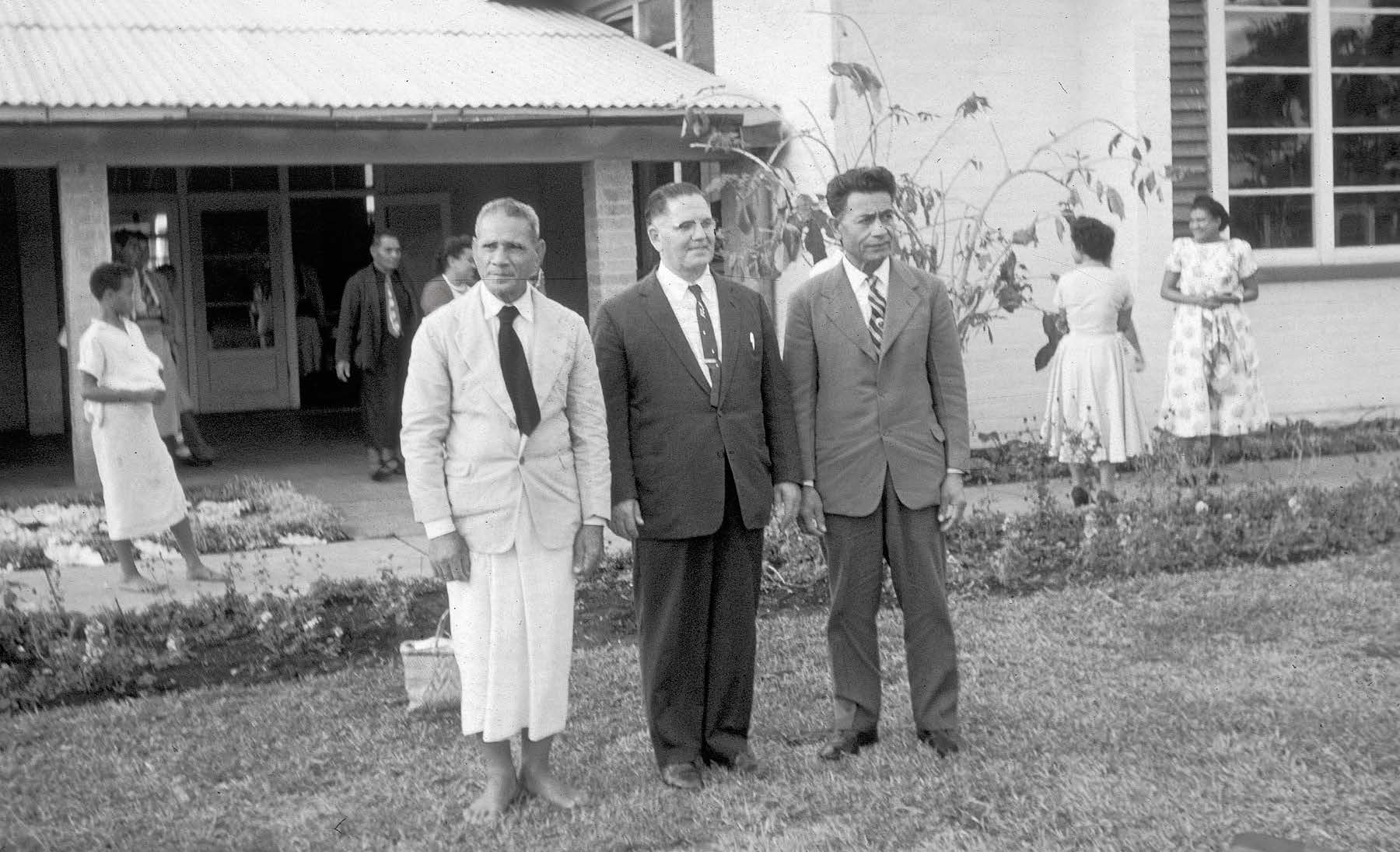

President Fred Stone with his counselors Siosifa Tu‘iketei Pule and Misitana Vea. Zola Jensen collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

President Fred Stone with his counselors Siosifa Tu‘iketei Pule and Misitana Vea. Zola Jensen collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

On May 2 President Coombs went to Niue. The resident high commissioner there, Mr. McEwan, praised the missionaries and said he didn’t expect any more trouble from the London Missionary Society people,[47] as they had now accepted the fact that the Latter-day Saints were on Niue to stay.[48]

Fred Stone Replaces D’Monte Coombs

As the year ended, President Fred Stone, a former missionary from 1926 to 1929, arrived in Tonga to replace President D’Monte Coombs.[49] President Stone’s brother, Howard Stone, was at the same time president of the Samoan Mission. Fred Stone chose seasoned veterans Siosifa Tu‘ikitei and Misitana Vea as his counselors. At the farewell interview between the Coombs and the queen on November 12, President Coombs explained the Book of Mormon and the aims of the Church in Tonga with respect to her people once more. The queen said she knew that the Latter-day Saints respected and supported her, contrary to the information her government gave her. She also felt the Church added much to her country and did not take away resources like the other churches. She sobbed as President Coombs bore his testimony; at the close she stood and said, “Me‘a‘a tangata piki” (‘farewell, man of principle’ in the royal dialect) and he replied, “Afio‘ā” (‘farewell’ in the royal dialect). Coombs noted, “I had every reason to believe that if it weren’t for the pressures of her being the head of the Wesleyan Church she would have been baptized. But I recognized how difficult it would have been.” It seemed that they were in Tonga “at the end of the old or the beginning of the new.”[50]

Prince Tungī also promised to issue landing permits for the incoming construction supervisors and their families. Another evidence of the growing maturity of the Church in Tonga came when President Coombs received authorization to form elders quorums throughout the country on September 13, 1955.

Nineteen fifty-five was also a banner year for Liahona’s rugby team. Although they were at a disadvantage as to size, weight, age, and school enrollment, they won the secondary championship by beating Tonga College at ‘Atele 18–0. Their coach, Sitarami Vamanrav, a member of another faith at that time, offered his services because he admired the cleanliness and fitness of the Liahona boys.[51] The boys also benefited from the Church’s incorporation of the Scout program. The Church had always been a leading force in the kingdom for the Scout movement even before Elder George Albert Smith, a great proponent of Scouting, visited in 1938.

Labor Missionary Program Resumes

With authorization to build twenty-one new chapels and approval to bring in building supervisors from America, a new labor mission program was set up, and fifty new missionaries were called and set apart on January 2, 1956, by President Stone to begin building the chapels and to enlarge Liahona. In preparation for these projects, the government granted landing permits to four new construction supervisors: Lavell Manwaring, Archie Cottle, Jack Dowdle, and Franklin Knowlton with their families.[52] Principal Ermel Morton wrote a long letter to A. G. Kemp, director of education, on January 10 requesting additional support for the Church’s educational program; Liahona was expecting 280 students to enroll for the new school year. He requested landing permits for more missionary teachers and permission to establish primary schools to feed into Liahona: “The Church is now starting this year an extensive building program in Tonga which includes 21 buildings suitable for use as classrooms in various villages throughout the islands.” Morton further noted, “It is contemplated that these be used for establishing Primary schools if teachers can be secured from America and permission granted for them to enter Tonga.”[53] One of the first things President Stone did was to assign Elder James Christensen to go to Vava‘u as district president and start a primary school there. At Liahona, Morton reestablished a Good English Club as he had at Makeke in 1937 to encourage better use of the language. At Liahona there were sixteen expatriate teachers. With the support and cooperation of President Stone, a primary school was established on March 22 in Ha‘apai called Tesaleti (Deseret) with 65 students under the direction of Elder John H. Groberg and another 80 adult night students learning English. This adult class resulted in many new contacts for the missionaries. A year later, when school started at Pangai on February 6, 1957, there were 42 students enrolled, but by the end of the year there were 102 attending, with 7 having been baptized under head teacher Elder Dale Frost. Other primary schools were established in Neiafu, with 150 students taught by Elder Don Milligan, and at Ha‘alaufuli, a school named Bountiful, with 80 students taught by missionary teacher Armand Glick.

Elder Wendell B. Mendenhall, chairman of the Church Building Program, who was closely supervising the construction of many chapels, schools, and the temple in New Zealand, arrived on February 24 to see how the program was progressing and to participate with the first chapel groundbreaking.

When the groundbreaking services for the new Mu‘a chapel occurred on March 5, 1956, it was raining heavily but the rain completely stopped for the services and the feast that followed, then immediately started up again. At this groundbreaking, President Stone had a favorable meeting with Prince Tungī, the noble of Mu‘a, concerning the need for more labor missionary supervisors.

President Fred Stone and labor missionary supervisors. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

President Fred Stone and labor missionary supervisors. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

On March 9, President Stone administered to Sister Fangeau, who was about to give birth. She had been married for twenty years but had not been able to conceive until President McKay had blessed her. A fine baby boy was born, and she named him David O. McKay Makasini.

Rugby was, and still is, the national sport in Tonga, and Makeke had fielded winning teams since the 1930s. In April 1956, the Liahona rugby team toured Fiji and Samoa, chaperoned by Elder Kenneth Lindsay. They won most games and conducted themselves in a very gentlemanly manner.[54] Then in August, a representative team from Fiji was hosted by Liahona and lost to Liahona 6–5. Track and field competitions among the secondary schools were also important, and Liahona hosted the 1956 Sports Day. Five thousand attended, including almost all the high chiefs and government officials.

The work on Niue was progressing nicely with Elder Charles Woodworth as the district president. The branch in Alofi had been meeting in the Bluebird Hall, an old dance hall the missionaries had fixed up. When President Stone visited Niue in late May, he pointed out the site where the approved new block chapel should be built. When he returned to Tonga from the New Zealand dependency, President Stone called the Mutis to help the elders get started building the chapel. Later Archie Cottle and Feki Po‘uha also came to help with construction.

Faculty at Liahona in 1956. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Faculty at Liahona in 1956. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

At the end of 1956, there were five districts in the Tongan Mission with over four thousand members: Hahake, led by Siosaia Maile Mataele; Hihifo, led by Epalahame Tua‘one; Niue, where there were eight branches on the little island, led by Elder Charles Woodworth; Ha‘apai, led by Elder John H. Groberg; and Vava‘u, led by Elder James Christensen. As the project to build new chapels and enlarge Liahona was underway, Makeke was used to raise food for the labor missionaries with Lisione Manisela as supervisor. Branches in Vava‘u and Ha‘apai were asked to plant gardens to help feed the labor missionaries assigned to build chapels in their villages. Mr. Riechelmann, a Nuku‘alofa businessman, offered his five-hundred-acre plantation on ‘Eua to the Church, but his offer was turned down because the property was too remote for Church purposes. As the old wooden chapels were being replaced by concrete block buildings, approval to replace the old wooden mission home at Matavaimo‘ui also came. Also, authorization was received to build a new, modern cafeteria at Liahona.

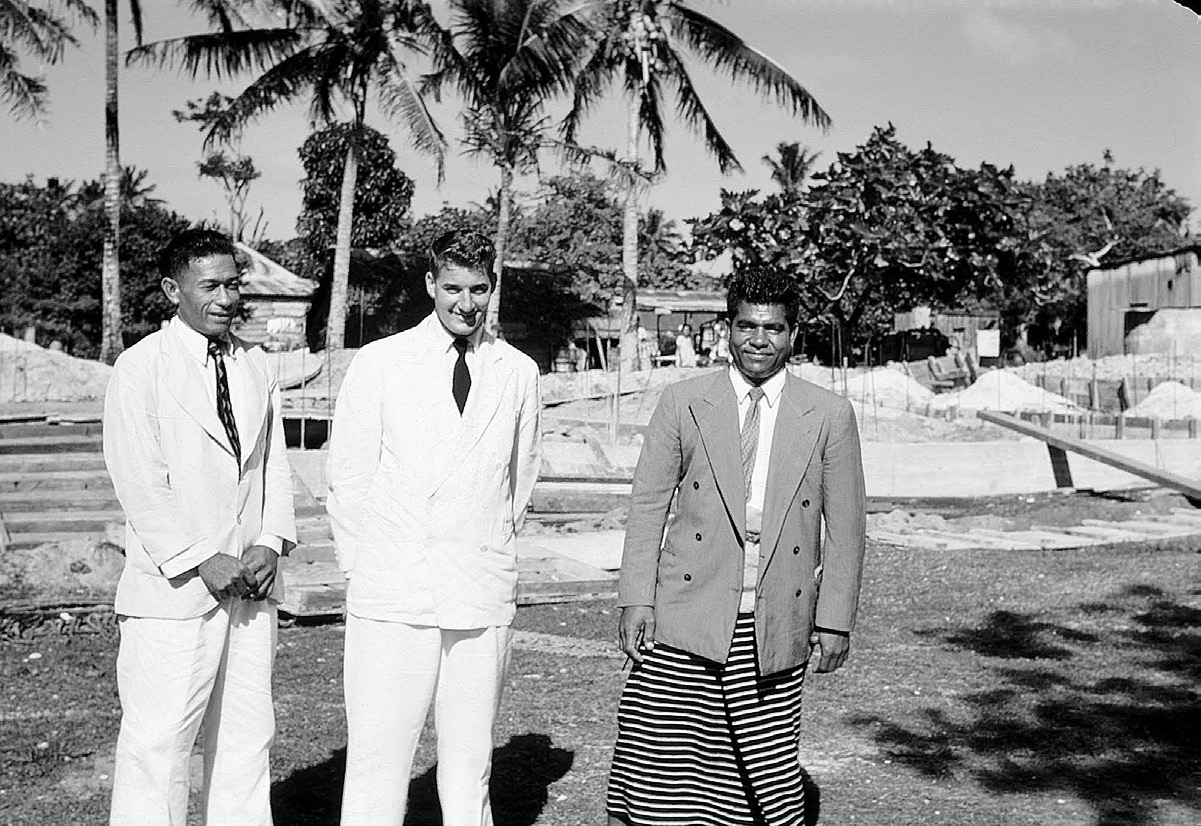

Ha‘apai District presidency: Sione Vea, Elder John Groberg, and Viliami Kongaika. Zola Jensen collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Ha‘apai District presidency: Sione Vea, Elder John Groberg, and Viliami Kongaika. Zola Jensen collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

President Stone recorded in his mission history that the greatest delay in obtaining leases for property to build new chapels was the lack of action by the government. The old issue of dealing with a Protestant-influenced government bureaucracy just wouldn’t go away. On December 5, 1956, he recorded,

Pres. Stone met with the Premier [Tungī] and the Minister of Lands [Tu‘ipelehake] regarding church leases. Application has been made for several months to obtain leases but they have apparently done nothing about it. They keep saying that it will be done next week but when next week comes around, still nothing has been done. All they do is give you the royal run around. . . . On the contrary they seem very jealous because they have done nothing for their own Church (Wesleyan) and they don’t want our Church to have an advantage for fear that we will take their members from them.[55]

Conversely, on October 12, 1956, when President Stone and Prince Tungī went to look for a chapel site in Fua‘amotu, Prince Tungī offered not only a piece of his estate for a chapel site but also eight acres nearby for the Fua‘amotu Saints to live on near the chapel on their ‘api kolo (town lots). At a feast the Fua‘amotu Saints held for Tungī, he told them about his trip to Utah.[56] The prince was obviously impressed by what he saw there and in meeting with President McKay.

By the end of the year, there were five American supervisors and sixty Tongan labor missionaries working on various projects. Ermel Morton reported that the labor mission was quite complex:

It had to include teaching of many of the building missionaries English and training them in various crafts; handling materials and trans-shipping them sometimes four or five times from a central unloading point; crushing quarry rock and gathering rock and sand from beaches; making a quarter-million concrete blocks; working without power equipment most of the time; finding a way through many obstacles of many types, including government red tape, to facilitate the progress of the work. In addition to this, the Zion labor builders had to overcome a formidable language barrier on every hand as well as a lack of knowledge of building procedures and practices on the part of the Tongan workmen who were eager and willing but who lacked the experience that would make the work go forward in the way desired.[57]

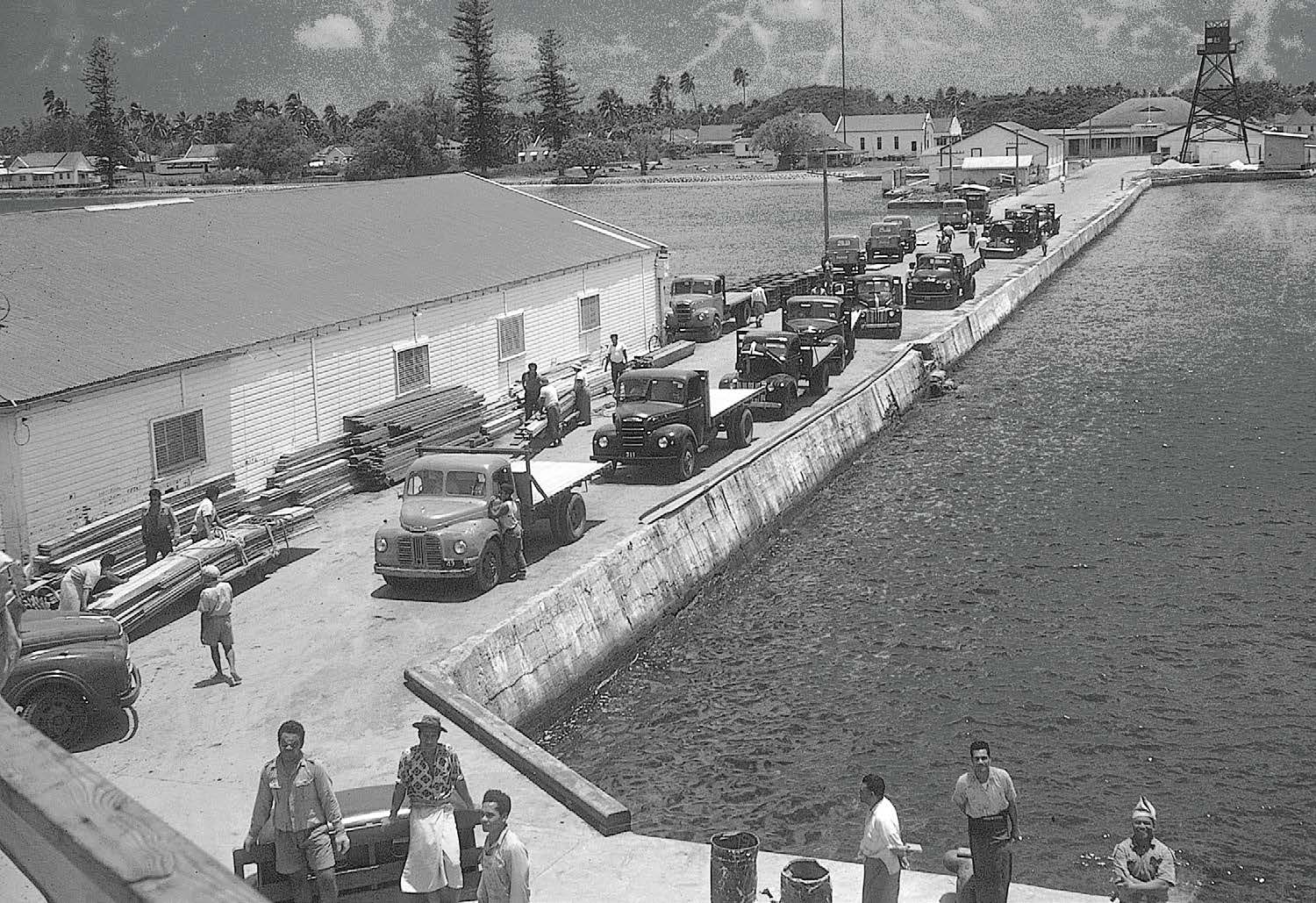

Elder John Groberg with the branch at Ha‘apai . Courtesy of John H. Groberg.There was also a continual problem of keeping equipment and materials from walking away. When a boat would come from America with building materials, the Church would arrange to use just about every truck on the island and work around the clock ferrying materials from the docks to Liahona and from there to ship them to the various building sites around the kingdom.

Elder John Groberg with the branch at Ha‘apai . Courtesy of John H. Groberg.There was also a continual problem of keeping equipment and materials from walking away. When a boat would come from America with building materials, the Church would arrange to use just about every truck on the island and work around the clock ferrying materials from the docks to Liahona and from there to ship them to the various building sites around the kingdom.

After six years spent establishing the finest secondary school in Tonga, Ermel Morton and his family were released to return home on January 28, 1957, and Brother Ralph Olson arrived to become the principal of Liahona. Brother Olson had served a mission in Tonga from 1926 to 1929 along with President Stone.[58]

In February 1957 members of the Makefu Branch on Niue had a dispute about where to build a chapel for their branch. Various members wanted it built on their land; one sister said if they didn’t move it to her land that she and the branch members would start a church of their own. District president Charles Woodworth found a piece of property to lease and instructed the members on how these things were done in the Church. Later that month two hurricanes hit Niue and destroyed most of the native chapels.[59]

Liahona faculty. Don Milligan collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Liahona faculty. Don Milligan collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

With the development of Church education in Tonga, the mission president was really overwhelmed with managing missionary work, districts and branches, and Liahona College and the primary schools. The First Presidency took notice of this and decided on July 12, 1957, to create the Pacific Board of Education to administer all Church schools in the Pacific, including the Church College of Hawaii, thereby relieving the various mission presidents of that responsibility. Wendell Mendenhall, who also headed the labor missionary program, was called as chair, and among the members of the board were Ermel Morton and D’Monte Coombs, so Tonga was well represented.[60] President Stone received a letter on August 4 telling him that the schools were now transferred from the mission to the Pacific Board of Education. Wendell Mendenhall and board secretary Owen Cook arrived on October 14 to effect the transfer.[61] Among their first decisions was one to cease calling professional educators as missionaries but to hire qualified teachers on a salary. President Stone encouraged students to go overseas, if they were qualified, get a university education, then return to serve their people in Tonga. The first Tongan student to get a scholarship to the Church College of Hawaii was Sione Tu‘alau Lātū. He was followed by Nanasi Fine, Kalo Mataele, and others.

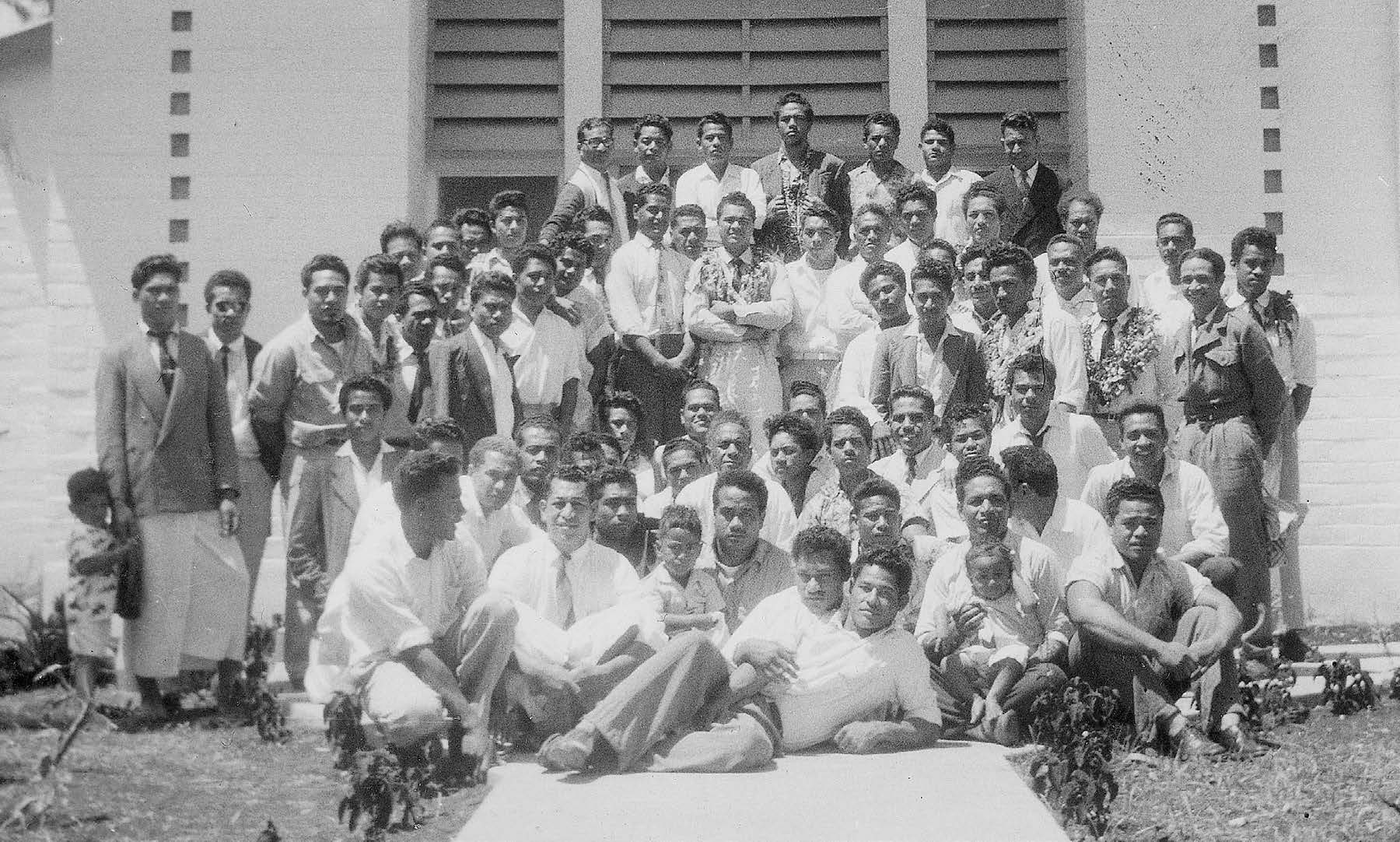

Labor missionaries serving in Tonga, late 1950s. Fred Stone collection courtesy of Perry Special Collections.

Labor missionaries serving in Tonga, late 1950s. Fred Stone collection courtesy of Perry Special Collections.

During the 1957 school year, forty Liahona students were baptized. To prepare for the opening of the New Zealand Temple, the mission held a genealogical conference on December 9, 1957, to organize committees and classes in all the districts and branches to prepare names to take to the temple. By this time, the building program was rapidly moving forward. At the end of 1957, there were eleven expatriate building supervisors and seventy-five Tongan labor missionaries, and sixteen chapels had been built to the square. Twenty of the original labor missionaries had finished serving their two years but wanted to stay until the project was done. They were learning many valuable skills.[62]

Reed Garfield baptizing Sione Ma‘afu Lasike at Liahona College. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Reed Garfield baptizing Sione Ma‘afu Lasike at Liahona College. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Considering the island geography of the Tongan Mission, getting the building materials to the construction sites was a challenge. Cargo from the United States generally came on two Norwegian freighters, the Thorsisle and the Thorshall, which stopped at Nuku‘alofa once or twice a year but eventually came more often because of the amount of cargo being delivered for the Church building program. Once at Nuku‘alofa, material for the outer islands had to be transshipped on smaller boats. At ‘Otea, Vava‘u, and ‘Uiha, Ha‘apai, there wasn’t even a dock. A Ford tractor the Church brought to ‘Uiha to haul materials from the beach to the chapel site was the first mechanized vehicle ever brought to that island. Lumber coming to ‘Uiha was usually thrown overboard and swum to the beach with the help of strong Relief Society sisters.[63] Franklin Knowlton was the general supervisor of the 1956–59 building program. Knowlton credits Viliami Sovea with suggesting that each U.S. missionary supervisor take a crew of Tongan missionaries to train and supervise rather than working all together.[64]

Unloading construction materials from the Thorsile. David Craner collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Unloading construction materials from the Thorsile. David Craner collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

One small miracle was related by electrician Elder Vernon Lee Gale:

As we were preparing to work on the Fua‘amotu chapel, Elder Knowlton asked me if we had sufficient electrical supplies to commence. I replied that we had only 14 outlet boxes, whereas it would take from 48 to 50 to do the job. Elder Knowlton said: “We will start and when we run out we will do something else.” As the chapel walls went up we installed boxes, never running out. Whenever we went to the storeroom for another box, one was always there. After installing fifty boxes, we moved to Liahona, taking along seven of the boxes with which we had started. Elder Knowlton asked again: “Can we start the Nuku‘alofa chapel?” I replied: “We still have seven, half the number we started with, in spite of the fact that we have installed fifty.” I searched all over Liahona College and found fifteen boxes in a place I had searched many times before, and we were in business again. These boxes kept us going until our supplies arrived from America. Please don’t try to tell me that this is not the Lord’s work.[65]

The local branch members, including women and children, turned out to help the missionaries in carrying water, sand, cement, and lumber. The women saw it as a relief from their regular chores. Even members of other churches brought food and helped as their mea ofa, or offering. They were intrigued with these unique projects in their villages where the cement block structure was likely the first of its kind. Some of the Tongan labor missionaries felt that from what they learned on their mission, they could build their own American-style home, and some did.[66]

Old and new chapels at Mu‘a. Zola Jensen collection, courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Old and new chapels at Mu‘a. Zola Jensen collection, courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

In Suva, Fiji, on January 15, 1958, President Stone met with Samoan Mission president Charles Sampson to transfer Fiji from the Samoan Mission to the Tongan Mission.[67] Given the monthly circuit of the Tofua and Matua through the islands, Church administration in Fiji could best be served from Tonga. The Church was growing, and Fiji allowed more expatriate elders than Tonga. Along with this, on February 25, the American SS Orcades arrived in Suva with seventy missionaries, teachers, and construction supervisors with their families for the Tongan Mission. Brother Mendenhall chartered a TEAL seaplane to carry forty-one of them to Tonga[68] so they wouldn’t have to wait a month in Suva for the next boat. There were twenty-six expatriate salaried teachers and several Tongan teachers to start the new school year. The last of the sixteen missionary teachers that started the 1958 school year returned home in 1959.

Vaha‘i and Sela Tonga

Vaha‘i and Sela Tonga

with their children. Zola Jensen

collection courtesy of Lorraine

Morton Ashton.

All these experienced American teachers at Liahona tended to alter the nature of Liahona College from that of a Tongan secondary school to that of an American high school. The name was changed to Liahona High School, forms were changed to grades, and the curriculum was altered to more closely resemble an American high school. Unfortunately, the revised curriculum did not necessarily reflect the needs of those students planning to live and work in Tonga, because only a few students were prepared and able to go overseas to get a university education and there were few opportunities to utilize a university education in Tonga at the time. The American system was geared toward preparing students for higher education, whereas the vast majority of jobs available in Tonga were of the vocational variety. This system simply did not benefit the Tongan students. They were finding it difficult to obtain employment because their Liahona High School graduation diplomas were not commonly recognized by local employers accustomed to Tongan credentials. The Tongan Leaving Certificates that showed a student had sat and passed a set standard examination could be compared against those of their peers throughout the kingdom, but an American graduation diploma could not. On October 26, the newly renamed Liahona High School graduated thirteen twelfth-graders with high school diplomas. This change in curriculum was noted by outside observers and would persist for many years even though one of the early policy goals for the Pacific Board of Education was to hire local faculty familiar with the Tongan educational environment. The realization of this goal had to wait many years for fulfillment until Tongans were able to return from their studies overseas, usually from the Church College of Hawaii. It took years to reorient the curriculum to meet the expectation of the Tongan educational system—this happened only after the administration and faculty were localized. Yet the name of the school remained Liahona High School.

Luisa and Courtesy of Viliami Kongaika. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Luisa and Courtesy of Viliami Kongaika. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Preparing to Attend the New Zealand Temple

After President McKay visited Tonga in January 1955, he went on to New Zealand. While touring the country, he announced that the Church would build a temple there just south of Hamilton at Tuhikaramea. To help prepare the Tongan Saints for this wonderful opportunity, Ermel Morton was called to translate the temple ceremony into Tongan. He worked on this in the Idaho Falls Idaho Temple while teaching at Ricks College. With this announcement, many families began saving for a trip to the temple in New Zealand. For years the mission had been encouraging genealogy work and held genealogy sessions at mission and district conferences that served as a great preparatory work.

For almost all Tongans, the expense of a trip to New Zealand seemed almost prohibitive given the Tongan economy. Many eventually ended up selling virtually everything they had to make the trip. Because of countless miracles, many Tongan Saints were able to make the journey to the New Zealand Temple. Luisa Kongaika described her family’s struggle to find the money to go.[69] Tevita Mahu‘inga related a series of amazing blessings he received related to his work as a police inspector that allowed his family to undertake this sacred expedition.[70] Leni Tu‘ihalangingie also told of a miracle that allowed him to take his family to the temple.[71]

The story of Semisi Nukumovaha‘i Tonga and his wife, Sela, illustrates the faith of the Tongan Saints in sacrificing to journey to the New Zealand Temple. When it was announced that a group from Tonga would go to the temple dedication, Vaha‘i and Sela Tonga decided they would like to go and began saving their money. Just when they had saved enough, President Fred Stone came to them on a Tuesday and said, “Brother Tonga, I want you now to take all the money you prepared to go to the temple and bring it all to me. We want to build a chapel in your branch, and if you don’t, the building program will pass by your branch and you will have to wait for a couple of years to build a chapel. Can you do that, Brother Tonga, for me?” Vaha‘i replied, “President, I’ll do it. Tomorrow I’ll get the money.”

On Wednesday President Stone came, and they gave him the money to build the branch chapel. But Vaha‘i and Sela still wanted to go to the temple. They decided to sell their cows, horses, and furniture. On Thursday and Friday, no one came to buy their goods. The temple excursion was to leave on Monday. However, on Saturday three families came and bought all the items they were selling. On Monday morning, they took the money from the sales to President Stone, who said, “Brother Tonga, the Lord will bless you.”

In New Zealand Vaha‘i and Sela Tonga were the first Tongan couple to be sealed after the dedication. Brother Tonga, a skilled choir director, led the Tongan choir at the dedication program. However, when they were sealed, they both had tears in their eyes because their children were not there. For two years after their return they ate no meat and lived on seventy cents a month. The children went without candy or shoes or going to the movies. When Vaha‘i had Church assignments in other branches on the island, he rode his bicycle instead of paying his share to ride in a car. They had just enough money for their family to join the temple excursion of November 1960.[72]

Mosese and Salavia Muti and their children. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Mosese and Salavia Muti and their children. Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Another amazing story of sacrifice is that of Viliami and Luisa Kongaika of Pangai, Ha‘apai. When Viliami and Luisa got married, they couldn’t have children. Viliami asked Elder George Albert Smith in 1938 to bless Luisa. He promised Luisa she would have not one, but many boys. Nine months later she had her first boy, and then others came. Elder Groberg, who was serving in Ha‘apai at the time, told them to prepare to go to the temple in New Zealand when it opened. Viliami was serving as a counselor to Elder Groberg and didn’t have any money, although they did everything they could to raise some funds. Viliami told Luisa that if they sold everything, they’d have enough for just the two of them, but Luisa didn’t want to go without her seven children. Therefore, Luisa, a skilled seamstress, set out to sew clothing for purchase. They made and sold copra from their coconut trees and sold crops from their garden. Then they sold their nice lumber house, board by board, to their neighbors. Eventually all the family had left were the clothes on their backs, their suitcases, and Luisa’s sewing machine, which they stored. They eventually had just enough to take their whole family to the temple.

When they returned, they worked on the Makeke plantation and lived in a little Tongan fale to earn some money, then returned to Ha‘apai in 1961. They faced persecution from their friends, family, and even some Church members. Their neighbors ridiculed and laughed at them. They had come back home and had nothing. The people said, “Now where are you going to stay? You have no place to go. Your property is all gone. We were right. You are a fool for going.” So they started from scratch. They built a little Tongan fale with coconut fronds.

In March 1961 a big hurricane came and basically blew everything on the whole island into the ocean. Now everybody had to start from scratch. They had to salvage whatever little bits and pieces they could gather and start over. Viliami’s son ‘Isi said, “We never lost anything. We have built ourselves a mansion in heaven. We would never have been able to do this if we had stayed. Then other people came to notice the wisdom of my father. Now we are a forever family because of my father’s courage to follow his promptings.”[73] Sione Fineanganofo agreed, “When the hurricane came in 1961, all the houses in the island were destroyed and Viliami’s family lived just like everyone else, but they had been to the temple.”[74]

Perhaps the most amazing story is how Mosese Muti and his family found the means to attend the temple. Brother Muti had been called to serve a labor mission with his family to the island of Niue in 1956. Earlier he had been ordained an elder by Elder George Albert Smith on May 12, 1938. In that ordination blessing Elder Smith, as reported by Sione Fineanganofo, promised Mosese “that through his faithfulness, perseverance, and steadfastness in keeping the commandments of the Lord, he would one day take his sweet wife to the House of the Lord at no cost to them.”[75] On Niue the Mutis met Elder Charles (Chuck) Woodworth, and they became close friends as they helped build the new chapel in Alofi along with Feki Po‘uha and Archie Cottle as supervisor. The Mutis sincerely wanted to go to the temple, but there was no way they could get the money to go. At the end of his mission, Elder Woodworth, who had boxed professionally before his mission, asked for permission and was granted the opportunity to arrange a fight in New Zealand with a world heavyweight contender named Kitione Lave. Woodworth was regarded as a heavy underdog with no chance to win, but after a rough start he went on to beat Lave before 15,000 spectators in Auckland on February 25, 1958. He won $10,000, which he used to pay the way for the Muti family to go to the temple dedication. The Mutis went on to serve eleven missions from 1938 to 1983.

Many other members were able to get to the temple through events that were beyond coincidence. One such family was that of Folau and ‘Onita Mahu‘inga. While Brother Mahu‘inga was serving as branch president in Nuku‘alofa in 1958, Elder Marion G. Romney of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles came to dedicate the first labor missionary chapel in Nuku‘alofa at Latai. At that time Elder Romney told President Mahu‘inga, “President Stone has told me of your work and sacrifice in your Church calling. For this devotion there will be a blessing in your life that will allow you to take your family to the temple.” Later as he took Elder Romney to the boat, the Apostle specifically said he would receive a promotion in the police force that would “take” him and his family to the temple. The next day the queen’s cabinet approved his promotion from sergeant to inspector, which position included the benefit of a six-month leave anywhere in the Commonwealth after three years’ service. But saving money in Tongan society with its ceremonial and family obligations was next to impossible.

Later as inspector of police in Ha‘apai, he had a dream to build a fish trap near the reef pass between Lifuka and Ha‘ano against the advice of experienced fishermen. He went ahead with building his fish trap and in six months caught and sold enough fish to pay for his family and his parents to go to the New Zealand temple for six months.[76]

Suva, Fiji, chapel from Don Milligan, Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Suva, Fiji, chapel from Don Milligan, Courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Forty- Forty-seven Tongan Saints sailed to Suva by way of Vava‘u and Apia, where they picked up more Saints going to the temple, making 125 in all, then flew from Nadi to Auckland on April 9. During the celebrations in New Zealand, they performed for President McKay and his party and then witnessed the dedication of the temple on April 20. Their Tongan sessions were held on April 22 and 23, and the group returned to Tonga on April 28.

On his way home, President McKay and his party stopped in Suva. President McKay was unhappy with unnecessary restrictions the Fijian government placed on the number of foreign missionaries. On May 4, 1958, he dedicated the beautiful full-sized Suva chapel that he had asked to be built when he had visited in 1955.[77] President McKay was presented with a special tabua (sperm whale tooth pendant), which required a special act of government. Many people attended the dedication, including Governor Sir Ronald Garvey, the colonial secretary, and the mayor of Suva.[78] The next day President McKay met with Governor Sir Ronald Garvey and arranged to have the missionary quota increased from three to six elders.

During this time, the many chapels that were being built in Tonga were completed, and dedications were held almost every month around the kingdom.[79] After the New Zealand Temple dedication, Elder Marion G. Romney stopped in Tonga to dedicate the Nuku‘alofa chapel at Latai. Six hundred attended the dedication, and Prince Tungī opened the door to the new chapel. Elder Romney dedicated the Matahau and Alofi chapels on Niue. On May 28, Elder Romney, along with the Stones, Mendenhalls, and Clissolds, sailed on the Tofua to visit the chapels nearing completion at Pouono in Neiafu and at Ha‘alaufuli.[80]

The Church was growing in the Nuku‘alofa area, and a new district called the Vahe Loto District was formed from the Hahake District on July 13. It was led by Maile Mataele, and covered the branches in the Nuku‘alofa area. Prince Tungī, the noble of Mu‘a, also attended the dedication of the Mu‘a chapel on October 19. At the dedication, Prince Tungī broke several royal protocols by his extended conversations with the Latter-day Saint missionary supervisors.[81] He told them he had made a point of visiting other labor missionary projects in New Zealand, Hawaii, Samoa, and Fiji.[82]

His Royal Highness Prince Tungī opening the new Nuku‘alofa chapel at Latai 1958. Fred Stone collection courtesy of Perry Special Collections.

His Royal Highness Prince Tungī opening the new Nuku‘alofa chapel at Latai 1958. Fred Stone collection courtesy of Perry Special Collections.

Members carefully disassembled the old wooden chapels being replaced and reassembled them in other sites to serve as chapels for smaller branches. Members from Houma pulled down the Matavaimo‘ui chapel and reassembled parts of it in Houma. They used other parts of the Matavaimo‘ui chapel to construct chapels at Nakolo, Veitongo, and a twenty-four by forty-foot chapel at Tongamama‘o on ‘Eua—all under the direction of Iohani Wolfgramm. They moved the Ha‘alaufuli chapel to Tefisi; the Pangai, Ha‘apai, chapel to Faleloa; and the Ha‘ateiho chapel (which had earlier been moved from Makeke) to Tokomololo. They transported the old mission office at Matavaimo‘ui to Fo‘ui to be their chapel.

On October 13, 1958, Owen Cook, the secretary of the Pacific Board of Education, arrived to announce the closing of the three primary schools at the end of the year. There were at that time 100 students at the Bountiful school in Ha‘alaufuli, 150 at Neiafu under head teacher Robert Laird, and 100 at the Tesaleti school in Pangai, Ha‘apai. The Church and the government had agreed that the government would take responsibility for all primary education in the kingdom. At the end of the year, Liahona enrollment was up to 385 students, with fourteen expatriate teachers and twelve Tongan teachers. Eighteen graduates were leaving to pursue higher education overseas, ten were headed to the Church College of Hawaii.

Over the summer break, Liahona students were asked to serve as guides when the SS Orsova docked in Nuku‘alofa because their English language skills were considered the best, and the Liahona band played to greet the 1,400 passengers and 645 crew members. In addition, on December 15, thirty-five more Tongan Saints left for the New Zealand Temple, including the Kongaikas and the Paletu‘as. They returned on February 2, 1959.

Elder Marion G. Romney and Elder Wendell B. Mendenhall. Don Milligan collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Elder Marion G. Romney and Elder Wendell B. Mendenhall. Don Milligan collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Elder Joseph Fielding Smith stopped in Suva for just one day on February 10, 1959. In considering the condition of the Tongan Mission and the severe quotas of expatriate missionaries, he considered the missionary quotas to be a blessing, motivating local members to step up and help carry the work.[83]

The old wooden mission home at Matavaimo‘ui was old, and a new mission home was built at Fasi to replace it. It included the mission president’s quarters, the mission office, and some missionary quarters. Princess Mata‘aho toured it on March 9 with Sister Stone before it was dedicated on June 7. It was named Maamafo‘ou, or New Light, the same name as the original Church school in Neiafu.

To help support the school, the 324-acre Brehner property at Niumate, a plantation a mile and a half west of Liahona, was leased on April 4, 1959, for $92,000. This offered more vocational agriculture opportunities and copra production. Under the supervision of Ross Bulkley, Niumate also increased the school’s ability to provide more food to feed the campus.

The Church heavily subsidized Liahona. The boarding students paid two shillings per day for board and room. If the families lacked cash, the students received work assignments on the plantation and grounds. President McKay’s desire that Liahona be enlarged caused enrollment to increase. There were 385 enrolled in 1958, 485 in 1959, and 500 in 1960. There were often more applicants than there was room. Many of Tonga’s youth wanted to attend, whether members of the Church or of other faiths, and some years, as many as one hundred students were baptized. There were baptisms on campus many Saturdays. Some of these young converts—such as Sione Tu‘alau Lātū, Sione Fineanganofo, and Saia Paongo—went on to get higher education and returned to Tonga as teachers. In 1959 Tupou Pulu was the first teacher to return from overseas to teach at Liahona. Liahona truly was the greatest missionary tool the Church had in Tonga.

Mark Vernon Coombs Replaces Fred Stone

President M. Vernon Coombs.

President M. Vernon Coombs.

Courtesy of Riley Moffat.

On June 22, 1959, President Mark Vernon Coombs returned to Tonga for his third mission to replace President Fred Stone. President Coombs had served as a missionary from 1911 to 1914 and as mission president from 1920 to 1926.[84] Liahona principal Ralph Olson left in May to become the dean of students at the Church College of Hawaii, where he always had a special interest in the students from Tonga. The new principal was Kenneth Lindsay, who had come as a missionary teacher in 1953.

President Coombs kept Siosifa Tu‘iketei Pule and Misitana Vea as his counselors. On September 8, the First Presidency appointed an advisory board for Liahona. They were President Mark Vernon Coombs as chair, with Lisiate Talanoa Maile, Hale Vete, Tevita Kitekeiaho, and Manase Nau, and Principal Kenneth Lindsay, ex officio.[85]

During the labor mission from 1956 to 1959, members built forty-three structures, with an average of one completed every twenty-seven days.[86] They encompassed over 200,000 square feet of floor space and cost almost $2,000,000, with nearly $500,000 paid to the Tongan government in import duties. Cummings wrote, “So much for the tangibles. No score can be computed for the intangibles: the spiritual growth of the labor missionaries, their joy in the mastery of a well-paid trade, the upward surge of prestige for the Church throughout the Kingdom of Tonga from the throne down, the immeasurable benefits to the youth of Tonga, both Mormon an[0] non-Mormon through education in a splendid, modern school and, central to it all, the powerful, continuing stimulus to the spread of the restored gospel of Christ.”[87]

In the early years of the Church in Tonga, little branches met in little Tongan fale in many villages so that the meetinghouses were within walking distance of the members. As the building program built large new chapels, the usual practice would have been to combine several branches to make larger congregations. However, the Tongan experience was that many new converts began filling the big new chapels in each village. It fulfilled the motto “If you build it, they will come.”[88]

On December 4, 1959, another group of seventy-three Tongan Saints sailed on the Tofua as deck passengers on their way to the temple in New Zealand via Niue, Pago Pago, then on to Apia and Suva, where a gasoline strike stopped all ships and planes from leaving. The travelers ended up sleeping on the floor of the Suva chapel, but a miracle allowed them to get to Nadi to catch a plane to Auckland. These Saints handled this challenging situation so well that their food and temple clothes were provided for free by the Auckland First Ward. They returned to Tonga on January 4, 1960. President Coombs said that many members of this temple excursion had sold their homes or their last cow or pig to raise the money to go to the temple. “They stayed for a month and left with tears of gratitude in their eyes for the blessings they received.”[89] These first Tongan Saints who could go to the temple in 1958 and 1959 returned with a greater understanding of the gospel and a greater dedication to remain true and build the kingdom of God in Tonga.

The decade of the 1950s really established The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the Kingdom of Tonga. As President D‘Monte Coombs said, the Church in Tonga went from being second class to a league of its own. The Church had the finest school in the country where students received not only academic instruction but perhaps more importantly spiritual training and preparation for missions while converting many of other faiths who chose to attend Liahona. Fine new concrete block chapels dotted the islands. But more significant was the faithfulness of the members. They responded to calls to serve missions and callings in their branches and districts. There were many second- and third-generation members, well grounded in gospel principles. They understood how the Church operated and held their meetings and devotionals properly under the direction of priesthood and auxiliary leaders. Mission, district, and branch conferences were held regularly even though there could be challenges with transportation. By the end of the decade there was a strong core of members who had been to the temple and understood and lived the covenants they made there. As Elder Cowley and others had noted, the lack of missionaries from Zion was actually a blessing. The mission leadership was prepared to lead out on their own. By the end of the decade all the standard works were available in Tongan as well as much of the instructional material for the auxiliaries. The palangi teachers at Liahona and the construction supervisors who responded to calls to serve in Tonga set good examples, but the pure faith of the Tongan Saints often raised the bar. They were not afraid to make whatever sacrifices were necessary for the gospel’s sake.

Notes

[1] In Tonga and much of the British Commonwealth a “college” is a secondary school, or high school.

[2] R. Lanier Britsch, Unto the Islands of the Sea: A History of the Latter-day Saints in the Pacific (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1985), 468.

[3] “Californian to Build New Liahona College in Tongan Mission,” Church News, April 23, 1950, 5.

[4] Evon Wesley Huntsman, “My Story Lest I Forget,” http://

[5] Tisina Wolfgramm Gerber, comp., Iohani Wolfgramm: Man of Faith and Vision, 1911–1997 (n.p., 2000), 106.

[6] Lionel and Norma Going, “Our Mission to Tonga and Samoa,” typescript in the possession of Riley Moffat.

[7] David Cummings, Mighty Missionary of the Pacific (Salt Lake City, Bookcraft, 1961), 138.

[8] Cummings, Mighty Missionary of the Pacific, 138.

[9] Cummings, Mighty Missionary of the Pacific, 137.

[10] E. J. Morton, “Tongans Prepare to Celebrate Liahona College Completion,” Church News, July 11, 1951, 4–5.

[11] MHHR, by date.

[12] Mission Financial and Statistical Report, 1951, CHL.

[13] “New President Appointed for Tonga Mission,” Church News, November 21, 1951, 3.

[14] Ermel J. Morton, 20th-Century Western and Mormon Americana, Perry Special Collections (hereafter cited as Morton notes), 15.

[15] Joan Coombs, interview by Vai Latu (1980), CHL.

[16] “Building Experts Back from Pacific,” Church News, December 13, 1952, 12.

[17] Lela Dalton, autobiography, 56, CHL.

[18] MHHR, December 31, 1953.

[19] “Elders Richards and Huntsman Complete Mission,” Church News, December 26, 1953, 6–7.

[20] Cummings, Mighty Missionary of the Pacific, 136–37.

[21] D’Monte Coombs, interview by Vai Latu, 1980, CHL.

[22] “South Sea Missions Boundaries Changed,” Church News, August 14, 1954, 4, 10.

[23] “Ricks Instructor Translates Scripture into Tonga Tongue,” Church News, June 20, 1959, 17.

[24] Morton notes, October 6, 1954.

[25] “Tonga Students Tell Story in Dance,” Church News, August 20, 1955, 8.

[26] MHHR, March 31, 1955.

[27] D’Monte Coombs, interview, 1980.

[28] Morton notes, 34–35.

[29] MHHR, January 11, 1955. In other references it was variously called a taumafa kava or an ‘ilo kava ceremony reserved for nobility or heads of state.

[30] Harvey L. Taylor, “The Story of LDS Church Schools,” typescript, 2 vols. (n.p., 1971), 132.

[31] Morton notes, January 11, 1955.

[32] Morton notes, January 12, 1955. Here President McKay is paraphrasing Proverbs 22:6, “Train up a child in the way he should go: and when he is old, he will not depart from it.”

[33] Morton notes.

[34] President McKay’s detailed story of Martha Wolfgramm as recorded by Lela Dalton can be found in MHHR under the date of January 13, 1955.

[35] Lela Dalton, “Traveling with President and Sister David O. McKay in the South Pacific,” 1955, CHL. See Myrna Fairbanks, “Patrick and Lela Dalton,” 1999, MS 22403, CHL, and D’Monte Coombs, interview, 7, also Joan Coombs, interview. Also MHHR, January 13, 1955.

[36] Morton notes, 33.

[37] D’Monte Coombs, interview.

[38] MHHR, January 13, 1955.

[39] D’Monte Coombs, interview.

[40] “Tongan Prince to Repay Visit to Pres. McKay,” Church News, May 7, 1955, 10. See Morton notes, 32.

[41] MHHR, by date.

[42] Morton notes, 44. See “Band on Parade,” Church News, July 23, 1955, 10.

[43] D’Monte Coombs, interview. See Morton notes, 40.

[44] Morton notes, 38.

[45] D’Monte Coombs, interview.

[46] Delworth Keith Young, “Liahona High School: Its Prologue and Development to 1965” (master’s thesis, Utah State University, 1967).