Challenging Times (1930-39)

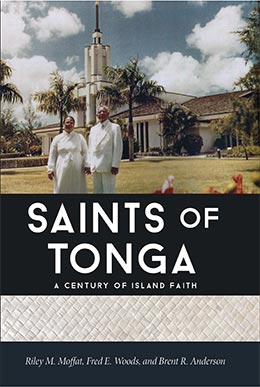

Riley M. Moffat, Fred E. Woods, and Brent R. Anderson, "Challenging Times (1930-39)," in Saints of Tonga (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 135–164.

Newel and Floy Cutler Return Home

As a new decade commenced, there remained yet some challenges for President Cutler and the mission. The school at Maamafo‘ou in Neiafu was closed in 1931 because of lack of support from the Saints and an epidemic of influenza that also caused Makeke to close for a while. Next, two more missionaries died in 1932. Elder Mervin Proctor died on April 12 of a heart ailment in Nuku‘alofa and was buried in Telekava Cemetery next to Elder Charles J. Langston, across from the Matavaimo‘ui chapel. Several months later, on August 2, Elder Victor Lee succumbed to typhoid fever at Ha‘alaufuli and was buried there across from the chapel. Also, this same month Sister Floy Cutler became ill with yellow jaundice. On August 17, 1932, President Cutler felt it necessary to take her immediately back to America for medical treatment. He set Elder Verl Stubbs apart as the temporary mission president. At the end of 1932 the membership of the Tongan Mission stood at 1,332.[1]

It took some time for a new mission president to be found and transportation arranged; in fact, it took over a year in this case. In the meantime, the elders carried on under the direction of Elder Stubbs. He reported to the Church News on the condition of the mission and noted that the elders were happy, diligent, and interested in their work.[2] Native Tongans received more leadership opportunities when Sione Taufa was called as mission Sunday School president and Tevita Vehikite as Mutual Improvement Association president. Herman Wolfgramm was serving as Vava‘u district president. Elder Charles Sanft from Vava‘u helped establish the Makeke College Theatrical Society.[3] Sanft, a talented part-Tongan who had attended the M.A.C. and had spent some time at BYU in 1929–31 learning to be a showman, put on successful fund-raising concerts in Nuku‘alofa to help Makeke students attend the mission conference in Vava‘u. He later had a very popular band in Vava‘u.

Reuben Wiberg Sent to Restore the Mission

In 1933 rumors reached Salt Lake that some missionaries were having some serious problems observing the Word of Wisdom and keeping the law of chastity. Their poor behavior had become known locally and became an embarrassment to the Church and its members. When the Brethren in Salt Lake City called a new mission president, Reuben M. Wiberg, they instructed him to investigate the situation and to close the mission if he felt the damage to the Church was significant: Wiberg was to clean it up or discontinue it. President Wiberg, who had served faithfully in Tonga under President Coombs as a missionary from 1920 to 1925, was told to leave his family behind because the Brethren anticipated closing the mission.[4]

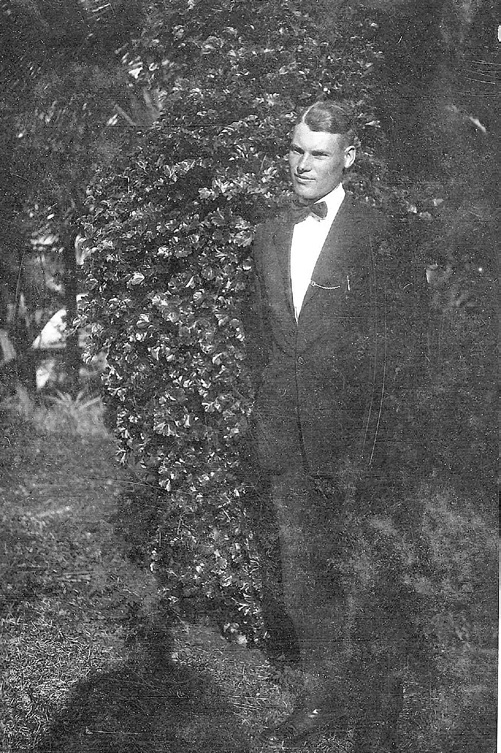

President Reuben M. Wiberg. Clarence Henderson collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

President Reuben M. Wiberg. Clarence Henderson collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

President Wiberg finally arrived in Nuku‘alofa on December 4, 1933, just in time for the school closing exercises at Makeke held four days later with one thousand in attendance. He also thought the final grand concert on December 21 was wonderful. President Wiberg wrote in the mission history a detailed description of the mission up to that point. Five foreign missionaries and twenty-four Tongan missionaries were serving when he arrived, and the total membership stood at 1,416. Elder Charles Sanft was the principal of Makeke, and the teachers were Samuela Fakatou, Pauliasi Malupō, and Pauliasi Pikula. Tevita Maile Niu was the teacher at the Ha‘alaufuli school.[5]

After New Year’s Day, President Wiberg left for a tour of the northern islands. At Ha‘apai he interviewed the missionaries and held what he called a “court martial relative to several missionaries’ conduct.”[6] At Vava‘u, from January 18 to 21, he “held some grilling sessions with other elders which were involved in misconduct, and enquired of some of the members who had knowledge of these things.”[7] The following day he “got more information relative to Elders trouble then made some definite regulations for them to follow.”[8] Wiberg believed that the elders’ conduct had not totally lost the confidence of the members and others who knew of Church standards. He felt confident the damage could be repaired and proceeded on that track. At Nuku‘alofa, on January 27, 1934, he “wrote a long letter to President Grant reporting the labors of the Elders.”[9] Four of the five foreign missionaries were sent home on the next boat and either excommunicated or disfellowshipped.

At each of the first round of district conferences, he preached strong sermons on living the principles of the gospel, and reorganizations took place at each of the conferences. With only one foreign elder to assist him, President Wiberg ordained a number of local men to the office of elder: Tevita Maile Niu, Sione Moleni, Sione Tuita, Charles ‘A. Wolfgramm, Tevita Mailangi, and Sione Leveni on Vava‘u and Sosaia Tonga, Misitani Vea, Mahanga Taniela, Salesi Vanisi, Sosaia Maile, and Pauliasi Vainuku on Tongatapu. By the end of February, native elders presided over all branches. In his quarterly report dated February 28, 1934, Wiberg wrote, “The reproachable conduct of . . . all of whom were released during this first quarter has caused a deep wound in the hearts of the Tongan Saints. They are all feeling discouraged, however, and are determined to live down the unsavory aftermath of the actions.”[10] Over time the peoples’ confidence in the missionaries was restored, and these incidents were forgotten. As part of an initiative by President Wiberg to rebuild the mission, “a special campaign was begun during April throughout the mission to learn the whereabouts of every member on record and as far as possible to get personal contact with them to inquire as to their standing and to encourage them to become active in church functions.”[11]

Local Members Step Up

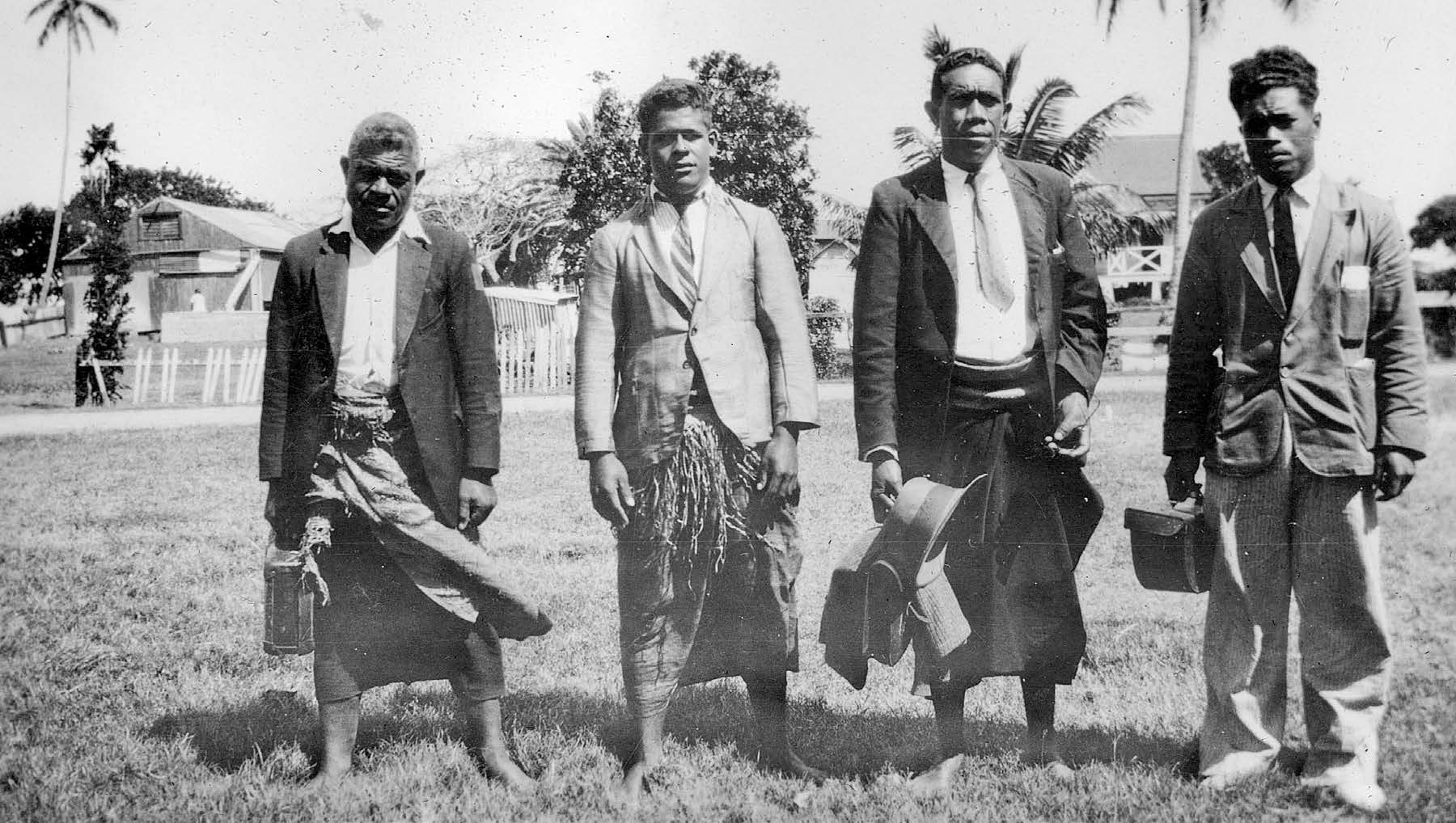

Native missionaries Sione Kongaika, Inoke Mataele, Simote Fusitu‘a, and Sione Tuita. Donald Anderson collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Native missionaries Sione Kongaika, Inoke Mataele, Simote Fusitu‘a, and Sione Tuita. Donald Anderson collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Again, the mission president needed to rely almost totally on the local members to run the mission. He had only one elder from the United States to assist him, and when Elder Childs, the district president in Vava‘u, left on January 8, 1935, President Wiberg was all alone until Salt Lake City sent more elders. The native missionaries that were left in Vava‘u were Sione Kongaika, Tevita Maile Niu, Paula Langi, Talanoa Maile, Efalame Wolfgramm, and Sione Esau. At that point all three districts were presided over by graduates of the Maori Agricultural College: Charles ‘A. Wolfgramm in Tongatapu, Misitana Vea in Ha‘apai, and Tevita Maile Niu in Vava‘u. All the branch presidents and missionaries were local brethren as were the mission’s auxiliary leadership and the teachers and staff at Makeke. During this time alone, he relied heavily on Charles ‘A. Wolfgramm to assist him on Tongatapu and spend time with him at Matavaimo‘ui.

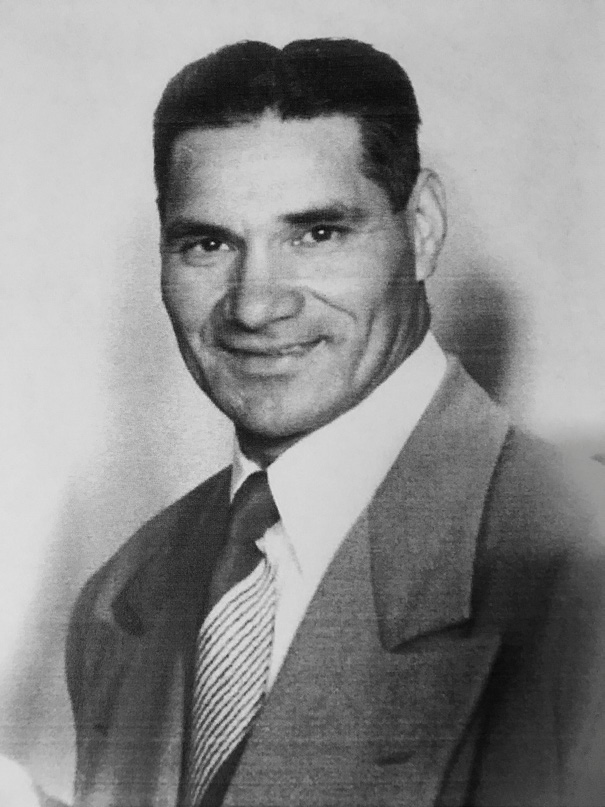

Charles ‘Ataongo Wolfgramm.

Charles ‘Ataongo Wolfgramm.

Courtesy of Family History Library.

In these early years, the president of the Relief Society was usually the mission president’s wife, but Ma‘ata (Martha) Wolfgramm from Vava‘u faithfully served in this capacity for four years. She requested Sister Teine Hettig from Nuku‘alofa as her counselor.

President Wiberg received a projector in mid-May with which to show Book of Mormon films. He would take this around to the various villages and put on a show, which drew a great deal of attention. It ran off a six-volt car battery. When he showed the films at the town theatre in Neiafu on July 28, four hundred people showed up.

Genealogical work initiated by President Cutler continued. For some time the mission had been sending names to the Hawaii Temple. When the work was completed, the slips were returned to the mission.

When Makeke opened for the 1935 school year, the school had a record enrollment of ninety ten- to eighteen-year-olds. Therefore, President Wiberg and the Tongatapu district president, Charles ‘A. Wolfgramm, both helped teach. President Wiberg also formed a Makeke School Board on May 21 to help supervise the school. Samuela Fakatou was selected as chair with Misitana Vea, Sione Tuita, Sione Esau, Tevita Pita, and Sosaia Maile as members of the board. Josiah Naeata was mentioned as being a great leader in managing the students.

Martha Emilie Sanft Wolfgramm. Karen Adams collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Martha Emilie Sanft Wolfgramm. Karen Adams collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

During a famine in early 1935, President Wiberg shared yams and bananas with Police Inspector Ballard for the relief of needy Europeans in Nuku‘alofa. A “food house” had been built at Matavaimo‘ui as a sort of bishops’ storehouse.

Demonstrating the strength of the mission, nine hundred people attended the mission conference held May 15–21, 1935. During the conference, relief arrived in the form of Elders Floyd Fletcher, Thomas Whitley, and Donald “Andy” Anderson. Elder Fletcher was assigned to Makeke, and “having had considerable experience in scouting,” he introduced the Boy Scout program into the mission school and had it up and running by September 1. Also during this conference a chief named Tevita Mapa and his wife, Mele, were baptized on May 19. It is believed he was offered the noble title of Ma‘atu by the queen if he would leave the Church, but he refused. He later became captain of the queen’s guard and secretary to the premier.[12]

In June the following year, Elders Whitley and Anderson were showing the sailors from HMS Leith and HMS Dunedin around Vava‘u, and word spread that the elders were drinking with the sailors. The rumormongers soon came and begged forgiveness for slandering the elders. Apparently, the poor conduct of some previous missionaries was still fresh in some people’s minds. Yet the work moved forward, and Elder Whitley helped the missionary efforts by organizing a Scout troop in Ha‘alaufuli.

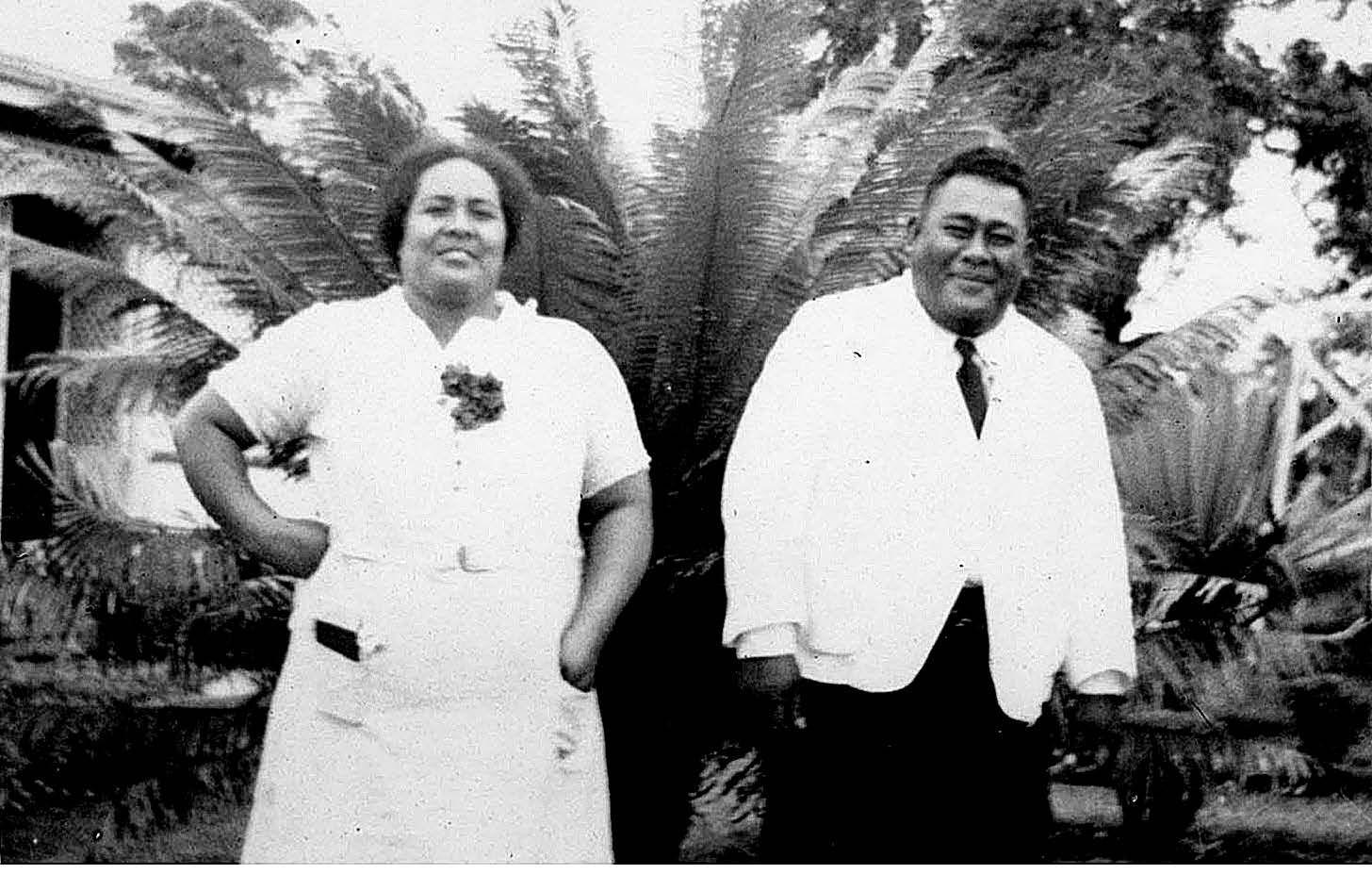

Mele and Tevita Mapa. Harris Vincent collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Mele and Tevita Mapa. Harris Vincent collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Preaching the gospel in Tonga was also hindered by the lack of Church resources in Tongan. Materials from Salt Lake were usually translated by the mission president’s wife or elders who had acquired the language, but with no one to help him, President Wiberg called Samuela Fakatou to be the mission translator. As a star student at the Maori Agricultural College in New Zealand and as teacher and principal at Makeke, Brother Fakatou had a good command of English. All printing of Tongan language materials was done at the mission home on various forms of duplicating machines.

Late in 1935 President Wiberg told the members that they needed to get the enrollment at Makeke back up to eighty-five or he would be forced to close the school. Tonga was still feeling the repercussions of the Great Depression, and many families were in arrears with their tuition payments. They lacked both the financial resources needed to keep it going and the missionaries to staff it. Because of the Depression and low prices for copra, there was no cash for tithing, so President Wiberg encouraged members to pay “in kind.”[13] However, the tithing in cash or kind did not come in, and Makeke did not reopen after the summer break.

Emile C. Dunn Replaces Reuben Wiberg

A new mission president, Emile C. Dunn, and his wife, Evelyn, arrived March 12, 1936. He had previously served as a missionary in Tonga from 1920 to 1924. Dunn replaced Reuben Wiberg, who had been in Tonga by himself without the assistance of any other elders from abroad for over one year and had organized everything under local leadership. Members held a farewell feast for President Wiberg at Kitione Maile’s home in Nukunuku. As he departed, President Wiberg expressed his feeling that “over the past three years one can see a vast improvement in the spirituality of the mission.”[14] On his way home, President Wiberg picked up a young man, Rudolph Herbert (Rudy) Wolfgramm, in Vava‘u to bring to the United States to attend Brigham Young University. In his quarterly report President Dunn had this to say about President Wiberg: “President Wiberg received his honorable release and left the same day on the SS Nordic for America. President Wiberg has done a fine work in organizing the work in the mission under the local priesthood, because of being here more than a year without help from Zion.”[15] When President Dunn arrived in Tonga, there were just three or four new elders, all of whom were struggling to learn the language.

Upon arriving, Dunn discovered that Makeke had been closed because of lack of finances and a shortage of missionaries who functioned as teachers. As a result he met with the Makeke School Board and got it going again within a month of his arrival by using Samuela Fakatou, Pauliasi Pikula, and Maile Mataele as teachers. They agreed on a list of plans and decided to reopen Makeke on May 19, 1936. President Dunn and Elder Fletcher met with Mr. Harry Selwood, the minister of education, to get copies of the government curriculum to use at the school.

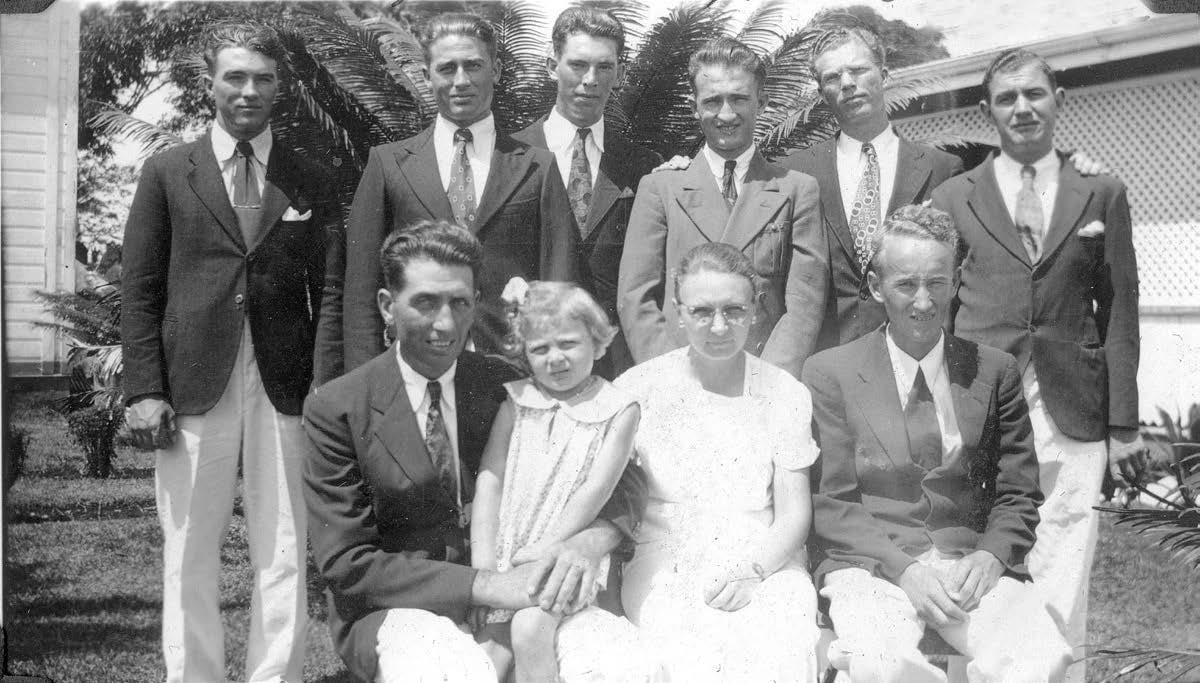

President Emile C. and Sister Evelyn C. Dunn. Donald Anderson collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

President Emile C. and Sister Evelyn C. Dunn. Donald Anderson collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

When Makeke opened, there were seventy students under the supervision of Elders Floyd Fletcher and Liddell Roberts. Mosese Muti and his wife, Salavia, were assigned to help them in June. Sione Tuita Vehikite was released as district president in Ha‘apai in February 1937 and assigned to teach music at Makeke. After classes, students worked on the Makeke plantation, where they grew copra and nutmeg to sell, and in gardens, where they grew root crops, making them nearly self-sufficient.

President Dunn had also brought with him the script for a pageant called The Conversion of King Limhi that his friend Carl Woods had written back in Utah. President Dunn called Charles Wolfgramm to translate it into Tongan.[16] It was a popular part of several Mutual Improvement Association conferences. People made costumes out of ngatu (tapa cloth), which gave the production a unique look.[17]

The mission had three cars, including a new V8 Ford. Much prestige came from having the flashiest car in the kingdom; even the queen and premier asked to use it. At this time a number of Solomon Islanders also worked on a copra plantation near Halaloto, where Samuela Fakatou was branch president. He did some proselytizing among the workers and converted some of them.

Brother Jacob “Sekope” Olsen, one of the early converts in Vava‘u in 1896, passed away at Tefisi on October 14, 1936. He had always been counted on to take care of the elders and had helped establish the Church in Leimatu‘a and Tefisi on Vava‘u.

A week and a half later, Elder Ermel J. Morton arrived as a missionary (October 25, 1936). Not only was he the first college graduate assigned to Tonga, but he was also very gifted with languages. Thus, he was immediately assigned to teach at Makeke under the current principal, Elder Floyd Fletcher. Elder Fletcher was an Eagle Scout and had organized Boy Scout troops, later taken over by Elder Thomas Wilding, in each district. The headmaster of Tupou College invited Wilding to instruct the boys at his school on Scouting; Wilding also organized a troop with twenty-seven boys at the Wesleyan Church in Nuku‘alofa until their minister forbade the boys to attend.

Elder Ermel Morton at Makeke

Within two months, Morton was preaching in Tongan, and on December 19, 1936, he was sustained as principal of Makeke. His autobiography, My Errand from the Lord,[18] relates a very interesting history of his year as principal. In preparing for the school year, he went to see Mr. Harry Selwood, director of education for all of Tonga and a good friend to President Coombs, and applied to start a Form 6 at Makeke. This would prepare students to take the Government Leaving Certificate Exam, which, if they passed, would allow them to become schoolteachers in the Tongan government system. Previously Makeke had only gone to Form 5 because Form 6 required a teacher with a bachelor’s degree. Morton was the first one the mission had ever had.

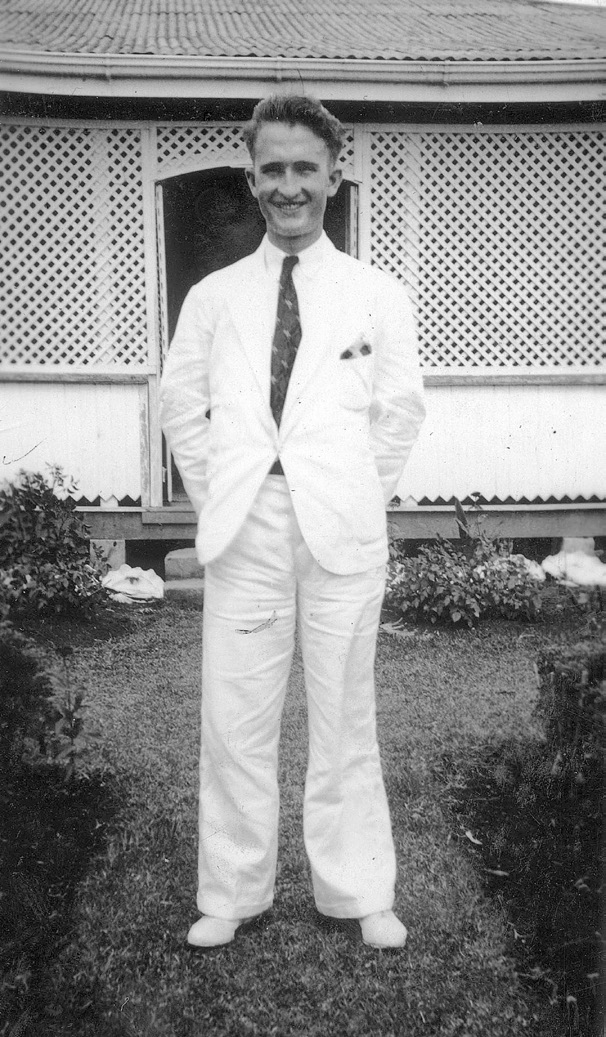

Elder Ermel J. Morton. Ermel J. Morton collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Elder Ermel J. Morton. Ermel J. Morton collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Elder Morton got a copy of the government college curriculum on February 9 and called Sione Tuita, a graduate of the Maori Agricultural College, as well as Mosese Muti, Nafetalai ‘Alusa, and Elder Liddell Roberts as teachers. The secondary students in Forms 2–6 were to meet in the large classroom building, and primary students in Grades 1–6 in the smaller classroom building. Not long after school started, a hurricane struck on February 22, 1937, and the girls’ dorm was blown down along with four native houses. The hurricane returned two days later with even greater force. Although the school buildings were boarded up, the boys’ dorm and five more native houses were blown down. After assessing the damage, mission leaders met and decided to rebuild. Starting on March 8, all the elders on Tongatapu and thirty-five Saints began the process of reconstruction, which was finished by the end of March. President Dunn was a staunch supporter of Makeke and of education. During his later service in Tonga from 1948 to 1950, he said those who attended the Church schools during his first mission were the backbone of the Church.[19]

Elder Morton listed the daily schedule at Makeke as follows: 6:00 a.m. wake-up bugle call; 7:30 marching practice with Brother Muti; 8:00 classes, beginning with seminary and continuing until 2:30, with an hour lunch at noon. Classes were followed by working on the grounds and in the gardens or plantation until 5:30, followed by dinner and study hall. The Mutual Improvement Association met on Tuesday evenings, and a dance or social was held on Friday nights.

Elder Morton wrote that he was trying to promote speaking English all the time, or at least during class. This was a never-ending challenge. One form of punishment for breaking school rules was to give a two-and-a-half-minute talk in English during morning devotional, which seemed to be very effective. Elder Morton also started a Good English Club, which gave positive reinforcement.

Students at Makeke. Ermel J. Morton collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Students at Makeke. Ermel J. Morton collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Elder Morton was hoping to see some of the Form 6 students pass their exam and be eligible to become teachers. To help these students, Elder Morton initiated a class on teaching techniques. Five of the Form 6 students signed up for the Government Leaving Certificate Exam held on November 8; unfortunately, none passed. However, one girl, Mele Lātū, did get a job as a head nurse at the hospital, and within a few years, several Form 6 students from Makeke were passing the exam each year.

In late July, Makeke received the band instruments from Maamafo‘ou College in Neiafu because the school there had been closed. The building was to be dismantled in order to use the lumber to build a new chapel in Neiafu and a recreation hall in Ha‘alaufuli. Under the direction of Sione Tuita and Elder Verl Teeples, the students soon formed a band that became very popular around the island, playing at dances, socials, po hiva, and po malanga (evening songfests and street preaching).

Elder Morton’s one-year assignment as principal ended, and he was replaced by Elder Verl Teeples. On December 4 President Dunn quietly gave Elder Morton the assignment to translate the Book of Mormon. Morton recorded he had a premonition earlier that year that he would be assigned to complete that task.[20]

Makeke school band. Ermel J. Morton collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Makeke school band. Ermel J. Morton collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Elder Morton’s initiatives at Makeke during the 1937 school year were so successful that when school opened again in February 1938, enrollment was up by one-third. Looking back at his service at Makeke decades later, Morton recalled, “I think the school had a big part to play in [the development of the Church in Tonga] because when I went there in 1936 during that year and the few years following I noticed and it was brought out in discussions that we had, almost every person of any importance in the Church who has had much of a position, they’ve had attendance and training in one of the Church schools either in those early primary schools or at Makeke or had gone to Maori Agricultural College.”[21]

After serving a year at Makeke, Morton was assigned to Houma. One challenge he had while serving there was to try to dissuade some of the Tongan missionaries from preaching too harshly and to avoid debates, arguments, and contention. A good Tongan orator can preach with real power, and apparently some were getting carried away.Fortunately, Morton also became good friends through faikava with Hokafonu, the chief of the entire Hihifo district who had previously been hostile to the Church.

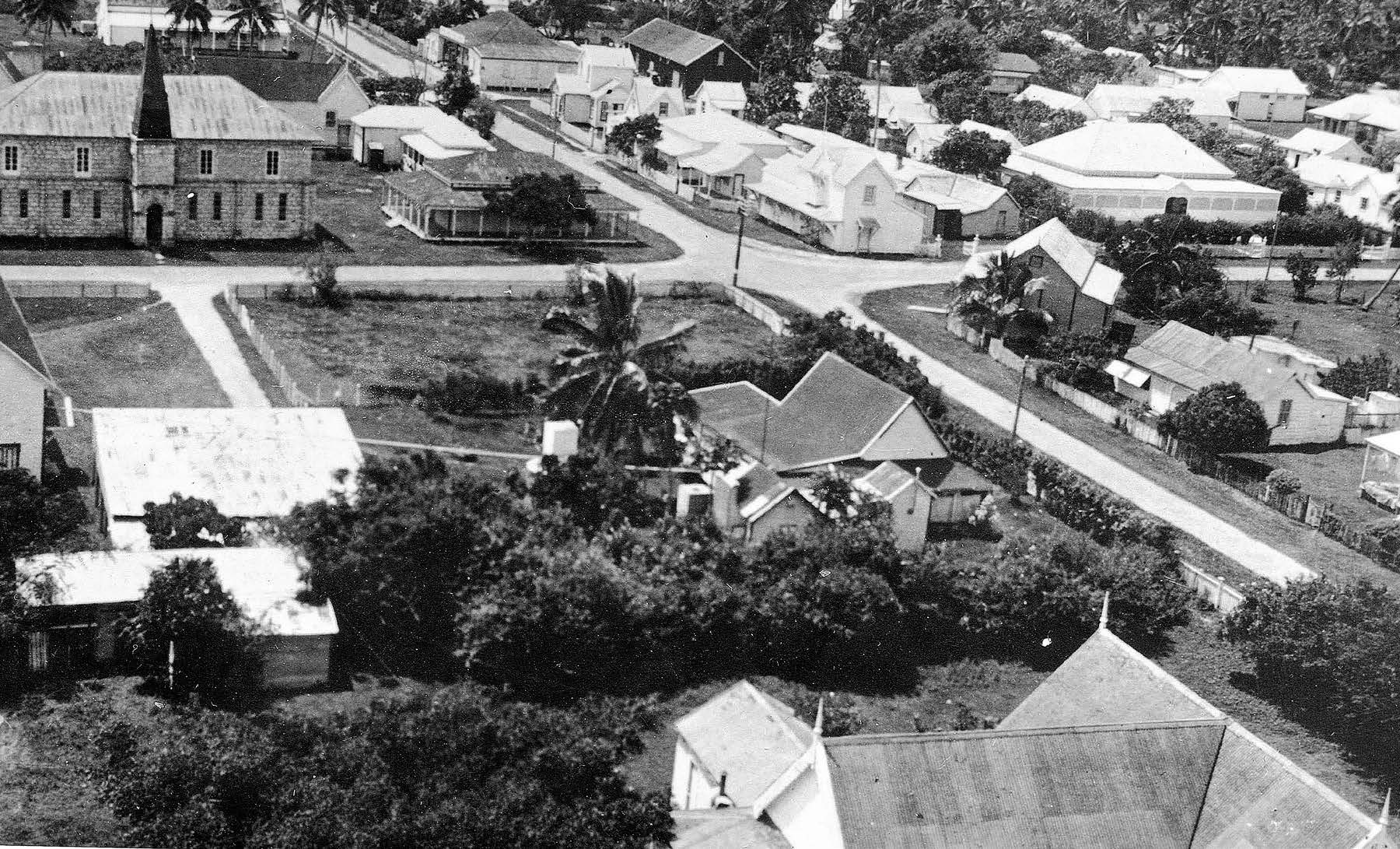

Downtown Nuku‘alofa late 1930s with Percival Building on top right corner of the intersection. Photo by August Hettig in Harris Vincent collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton

Downtown Nuku‘alofa late 1930s with Percival Building on top right corner of the intersection. Photo by August Hettig in Harris Vincent collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton

Ashton.

President Dunn promoted proxy ordinance work for the dead. On July 12, 1937, he assigned Elder Verrill Draper to organize genealogical committees in all the districts as well as several branches. From then on there were regular genealogical sessions at mission and district conferences.

A drought during the first half of 1938 caused widespread hunger. Previous Church leaders had encouraged members to plant extra gardens of root crops. By the end of the drought, Church members were nearly the only people with food to sell. President Dunn reported, “The only people who were selling produce to the market and steamers were the Mormons.”[22]

Visit of Elder George Albert Smith

The most important event of the decade was the visit of Elder George Albert Smith of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. He was the second apostle to visit the Pacific, and he spent a month from May 10 to June 8 of 1938 in Tonga. His traveling companion for this Pacific tour was Elder Rufus K. Hardy of the Presidency of the Seventy, but Elder Hardy had been hospitalized in New Zealand because of a serious illness that required an operation that rendered him unable to accompany Elder Smith to Tonga. Consequently, Brother Alex Wishart, a part-Tongan living in New Zealand, took Elder Hardy’s place. Brother Wishart’s father was a Ha‘apai trader, and his mother was from Ha‘afeva. While in Tonga, Dunn and Smith held three-day conferences with three sessions of conference each day in each of the three districts. Elder Smith spoke in every session, and all his talks were recorded.[23] Forty-eight people were baptized and fifty meetings were held during his visit.

Scouts from Makeke greeting Elder George Albert Smith. Harris Vincent collection courtesy

Scouts from Makeke greeting Elder George Albert Smith. Harris Vincent collection courtesy

of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

When Elder Smith and Brother Wishart arrived, they were greeted by the forty members of the Makeke Boy Scout troop, which was under the leadership of Elder Wilding and Brother Mosese Muti. Elder Smith was very impressed with the Scouts and Beehive girls in their nice uniforms. It was the first time on his trip that he had been greeted by Scouts. That afternoon the visitors were honored with a feast for one thousand at Matavaimo‘ui.

That first day of this trip, Brother Wishart spoke in Tongan, then Elder Smith greeted the conference by saying, “I am sorry that I cannot understand your language. It is not what you hear or what you see but the spirit you have. I have been privileged to talk to many people in many nations but I have learned but the one language. Therefore, I must always have some one interpret it for me.” To the Relief Society in a later session, he said, “You Tongan people should respect your Queen and honor her.” In regard to remaining faithful to the gospel message, he said, “The loss of our body is not very serious for it only lasts about one hundred years. But we must be careful not to lose our souls because it is eternal.” His messages that day were interpreted into Tongan by Charles Wolfgramm. Six hundred members and visitors attended this meeting.

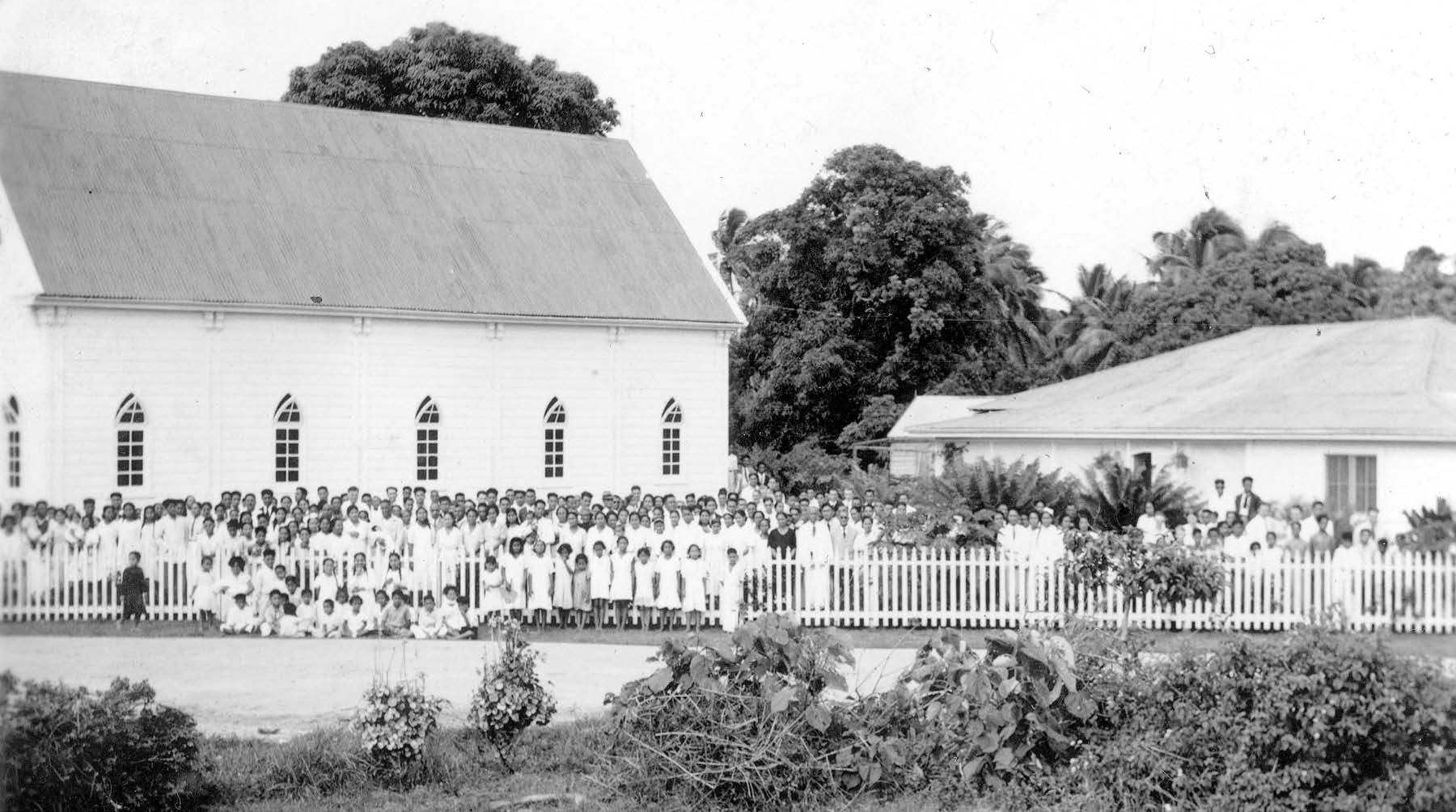

1938 Tongatapu District conference at Matavaimo‘ui with Elder George Albert Smith. Ermel J. Morton Collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

1938 Tongatapu District conference at Matavaimo‘ui with Elder George Albert Smith. Ermel J. Morton Collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

In a sermon given on May 11, he warned, “It will not be very long we will have a great war, and we will have famine and pestilence. . . . It will not be long until the Lord will gather his people. So Latter-day Saints should set their houses in order. See that you are law-abiding citizens.”[24] Elder Smith also said, “Some of you are from the Royal Family of Tonga, but all of you are of the Royal Family of our Father in Heaven.” After the afternoon session, twenty-five converts were baptized at the seaside in Nuku‘alofa. Following the baptismal service, Elder Smith told those in attendance, “This is the only ordinance which Christ received under the hand of mortal man while he dwelt here upon the earth.” The next day he talked about temple work: “Prepare your records, and if you cannot go to the temple, you can send the names for some one else to do for you.” That day he ordained Mosese Muti and Siosifa Tu‘iketei Pule elders and promised Brother Muti he would be able to go through the temple without paying a single penny from his pocket if he served in the Church all his life.[25]

Elder George Albert Smith with missionaries and Church leaders on Tongatapu. Ermel J. Morton collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Elder George Albert Smith with missionaries and Church leaders on Tongatapu. Ermel J. Morton collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Elder Smith and his party then sailed to Ha‘apai for an overnight stop, where Brother Wishart left to go visit his mother on Ha‘afeva. The visitors then traveled to Vava‘u for three days of conference during which Elder Smith told the Saints they were a remnant of the Book of Mormon people.[26] He also counseled them to be faithful in their tithing, saying the Lord would bless the land for their sakes. This probably referred to the drought the kingdom was experiencing and alluded to a similar promise President Lorenzo Snow made to the Saints in St. George, Utah, in 1899. The conference also included a sunrise baptismal service for five new converts. On May 29 he prophesied that Tonga would have great athletes if they kept the Word of Wisdom.[27] He also did some touring and visited the Swallows Cave.

Elder George Albert Smith aboard the Tu‘itonga sailing to the northern islands. Harris Vincent collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Elder George Albert Smith aboard the Tu‘itonga sailing to the northern islands. Harris Vincent collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

During the three-day conference in Ha‘apai, he preached on record keeping and spoke on the origin of Polynesians, noting that they were descendants of the Book of Mormon people and of Joseph who was sold into Egypt. There was no car or truck on Ha‘apai, so President Dunn bought a bicycle from the Morris-Hedstrom store for Elder Smith to ride on while everyone else walked.[28] Elder Smith said it was the first time he had ridden a bicycle in about forty years. On the last day of the conference, Elder Smith spoke on the history of the Church in Tonga, which he had learned by asking many questions during his visit. They held a sunrise baptismal service for four converts on the other side of the island of Lifuka, and three hundred attended. Afterward, Elder Smith rode his bicycle two miles back to Pangai. After the priesthood session that day, the Ha‘apai people presented him with an umu toho (an underground oven containing a very large pig), and a faikava. Throughout his visit, Elder Smith, a national leader of the Boy Scouts in America and a personal friend of the organization’s founder Lord Baden-Powell, spoke on the value of the Scouting program and said the Scouts in Tonga were the best he had seen.

Back on Tongatapu he had a visit on May 30 with Prince Tungī, who arranged an audience with his wife, Queen Salote. During his visit with Queen Salote, he discussed the Book of Mormon with her for an hour and promised to send the queen a copy of the Book of Mormon when it was published in Tongan. Little did he know that it would take eight years to fulfill his promise. He also visited the powerful noble Ata, the minister of lands, who was previously a most bitter opponent of the Latter-day Saints but had now become a friend of the Church. On June 3, Elder Smith toured the west end of the island, taking photos of all the Church buildings. At Halaloto he had dinner with Samuela and Heleine Fakatou.

According to Tongan Mission president Evon Huntsman in 1947, when Elder Smith was in Tonga in 1938, he drove past the Cowley plantation near Halaloto on June 3 and remarked, “This is where I would like to see the Church obtain some land.”[29] The Fakatous had been living nearby in the village of Mapelu-mo-e-lau since 1936 to care for the Halaloto Branch. Nearby lived a group of Solomon Islanders who were working on a copra plantation, and some had joined the Church.

Elder George Albert Smith inspecting a Church welfare garden on Lifuka. Harris Vincent collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Elder George Albert Smith inspecting a Church welfare garden on Lifuka. Harris Vincent collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

The next day Elder Smith toured the east side of the island and laid a wreath on the tiny grave of the Durham baby that had died in Mu‘a back in 1894 and laid wreaths on the graves of Elders Proctor and Langston at the Telekava Cemetery across from Matavaimo‘ui.[30] At a conference held June 5, Elder Smith “blessed the Tongan people and the land of Tonga to be a place of peace and plenty if the Saints would keep the commandments.”[31] Elder Smith also visited Makeke, which had a brass band and choir. He described the school as having a hundred students who grew their own food—he was clearly impressed with their self-sufficiency.

Having recovered in New Zealand, Elder Rufus K. Hardy arrived in Tonga on June 8, and he and Elder Smith sailed for Samoa two days later. Elder Ermel Morton was assigned to type up all of Elder Smith’s speeches. From this, Morton wrote up an article on Elder Smith’s visit for the Church News.[32] President Dunn recalled that Elder Smith was always asking questions about Tonga. He seemed very interested in learning all he could during his month-long visit.[33]

Developments after Elder Smith’s Visit

When Elder Morton was transferred to Ha‘apai, he sailed on the Tofua with young Prince Tungī. On the ship, they stayed up and played the piano and sang together. In Ha‘apai he described a water spout or tornado that skipped over the little chapel on Faleloa because of the prayer of ‘Isileli Fehoko. He also visited with Siake Lolohea, the Tu‘i Ha‘apai, or chief of Ha‘apai, who was instrumental in getting the Church established in Ha‘apai and who had suggested to King Tupou II in 1917 that he ask for a priesthood blessing.

Graves in Nuku‘alofa of Elder Mervyn Proctor, Vika Olsen, wife of Jacob Olsen, and Elder

Graves in Nuku‘alofa of Elder Mervyn Proctor, Vika Olsen, wife of Jacob Olsen, and Elder

Charles J. Langston. Ermel J. Morton collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

A few weeks after Elder Smith’s visit, the Saints, under the direction of Elder Thomas Wilding, dismantled the Maamafo‘ou chapel in Neiafu. Elder Wilding described pulling twelve baskets of bees and honeycomb out of the building without getting stung. Maamafo‘ou School had closed in 1931 because of decreased enrollment, and the missionaries living there had moved to Pouono. Part of the wood was then used to construct a new chapel over in the Pouono area of Neiafu, and the other part was taken to Ha‘alaufuli to build a recreation hall next to the chapel. President Dunn, along with Elders Thomas Wilding, Herman Lynn, Silvan Rindlisbacher, and Brother Charles Wolfgramm, started construction on the Pouono chapel on August 3. The local people donated over six hundred hours of labor. The Ha‘alaufuli recreation hall project was started by President Dunn and Elder Wilding on September 19. It was finished and dedicated two months later on November 21 and was the first church recreation hall in Tonga.

The dedication of the new Neiafu chapel occurred on November 25. It had cost £714 to build. At the dedication service, the highest chief on Vava‘u, Siosaia Kalauta, said that the chapel’s location at Pouono was sacred space. It was where Taufa‘ahau Tupou I had dedicated Tonga to God in November 1839. Kalauta said he first heard the elders preach in 1894 and was also the person who sold President Court of the Samoan Mission the horses that he came to buy in 1907. The dedication was attended by 546, and a large feast was laid out for 1,225. There were 225 pola (long trays of woven coconut fronds loaded with all kinds of food).

By December 31, 1938, the Latter-day Saint membership in Tonga stood at 1,672. The following year, President Dunn said the quota, or limit, for expatriate missionaries reached a peak of twenty-one.[34] At that point, the government set a policy that for every missionary who went home a new missionary could replace him. Some new missionaries were assigned to be teachers at Makeke, and the rest went out proselytizing. In 1939 the Makeke faculty consisted of Elders Verl Teeples, Franklin Spencer, and John Lowdle, with Tongan teachers Viliami Naeata and Mosese Muti.[35]

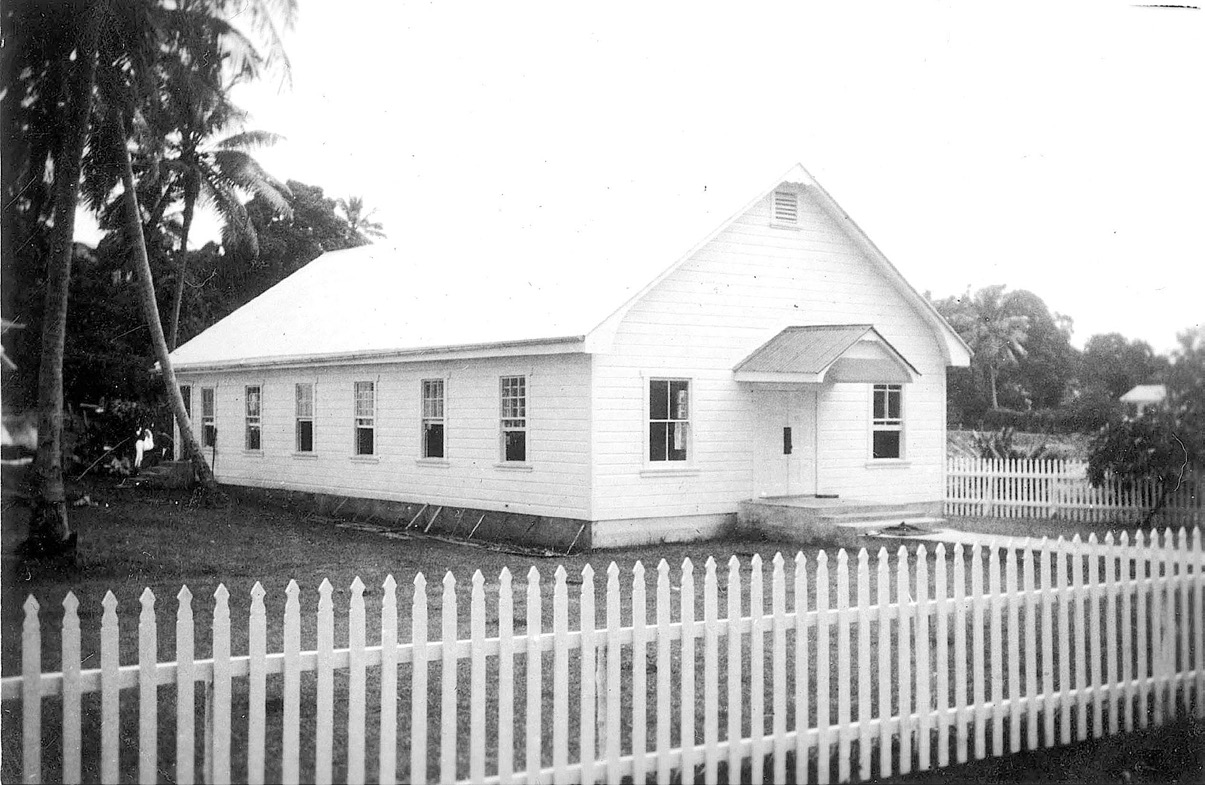

New chapel at Neiafu. Ermel J. Morton collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

New chapel at Neiafu. Ermel J. Morton collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

From time to time, missionaries had been assigned to visit Niuatoputapu with limited success. Over the next few years, President Dunn made a concerted effort to establish the Church there. During a district conference in Vava‘u in the late spring of 1938, he assigned Elders Epalahame Tu‘aone and Sioele Kauvaka to visit Niuatoputapu. They were the first missionaries to visit there since 1896. They were prevented for a time from landing because of their religion. Eventually Elder Kauvaka was able to make contact with relatives on Niuatoputapu and baptized his brother, Semisi Sika, and his family on December 18.

Several months later, on March 12, 1939, they organized a branch at Vaipoa on Niuatoputapu when President Dunn made his first visit and dedicated a new fale chapel there. He stayed for a month working to get the new branch operational. President Dunn then sent Misitana and Mele Seini Vea to preside over the branch. Sixteen years later a young American missionary named John H. Groberg would spend a year serving as a missionary on this island.

Book of Mormon Translation

While in Tonga, Elder George Albert Smith was so impressed with Elder Morton’s ability with the language that he asked President Dunn to assign Elder Morton to focus on completing the translation of the Book of Mormon but to keep his work confidential. In Vava‘u, President Dunn and Elder Morton found some Book of Mormon translations they thought Elder Sterling Ibey May had written while at Ha‘alaufuli years before. Unfortunately, only the translation of the book of Moroni appeared to be usable.

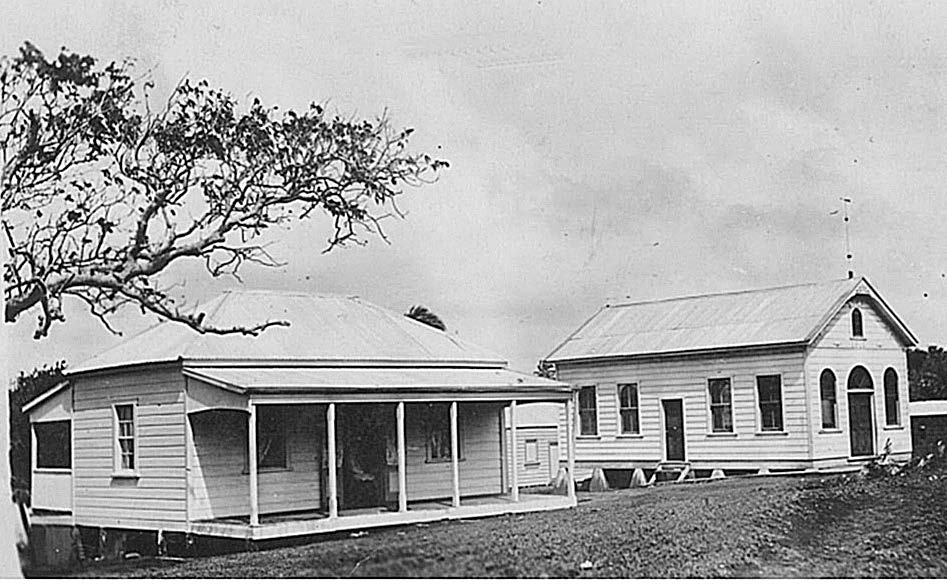

Ha‘alaufuli chapel and elders’

Ha‘alaufuli chapel and elders’

home. Donald Anderson collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton

Morton’s schedule involved teaching school at Ha‘alaufuli during the mornings, working on translation in the afternoons, then conducting cottage meetings in the evening whenever appointments could be made. Iohani Wolfgramm recalled that Elder Morton often came to ask him and his wife, Salote, about some Tongan words as he translated, but didn’t say why.[36] This schedule continued into 1939 with President Dunn pushing Elder Morton to finish his translation before it was time for him to return home. On April 10, 1939, President Dunn sent Elder Morton a telegram instructing him to translate full-time and to stay on an extra three or four months to finish the job.

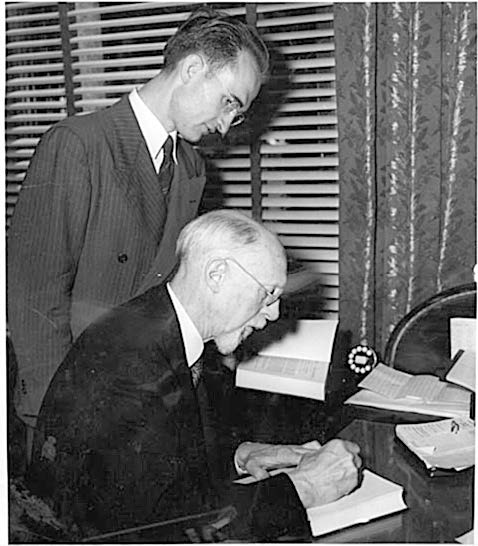

President George Albert Smith and Ermel J. Morton inspect the Tongan Book of Mormon. Ermel J. Morton collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

President George Albert Smith and Ermel J. Morton inspect the Tongan Book of Mormon. Ermel J. Morton collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Ten days later, President Dunn told the Saints at a conference in Vava‘u that the Book of Mormon had been translated. It was one of the two goals Dunn had set for himself when he came as mission president; the other was the new chapel in Neiafu. Elder Morton then went with him to Nuku‘alofa to review the translation before Elder Morton took it to Salt Lake. In Nuku‘alofa he was helped by Tevita Mapa, Sione Tu‘iketei Pule, and Charles Wolfgramm. On July 10 Elder Morton took the Book of Mormon translations to Vava‘u to have the elders there evaluate the translation. After reviewing and correcting the text with President and Sister Dunn and Elder Ralph Hugh Lee, Elder Morton left on August 25 to take it to Salt Lake. He delivered the Book of Mormon manuscript to President McKay on October 6, 1939.

However, that was not the end of the translation story. In 1942 Morton was called by Elders George Albert Smith and Rufus K. Hardy to assume the responsibility of revising the Book of Mormon manuscript. It was probably fortunate that the Church didn’t rush into printing it. In 1944 the Tongan Cabinet, on the advice of young Prince Tungī, who had been studying at university in Sydney, changed the way some of the Tongan language was spelled, such as replacing b’s with p’s and adding n’s before g’s, among other changes. The final proofreading was completed in 1945, and the book was finally published in 1946. Distribution began in Tonga when one of the first copies was presented to Queen Salote as promised by President George Albert Smith in 1938. In 1950 D’Monte Coombs, son of former mission president Mark Vernon Coombs, who was then over the Church’s Translation Department, said, “This is the only edition of the Book of Mormon in the history of the Church that had not been changed when it was reprinted.”[37]

Notes

[1] Archibald F. Bennett, “Dawning Day for the Children of Lehi: Descendants of Lehi in the Church,” Church News, April 1, 1933, 6.

[2] Verl L. Stubbs, “President Stubbs Reports Activities of Mission; Elders Are Happy in Tonga,” Church News, August 5, 1933, 3, 7.

[3] A college in the British Empire was really a secondary school equivalent to a high school.

[4] Colleen Whitley and Thomas Farrar Whitley, I Make a Record of the Things Which I Have Both Seen and Heard: The Missionary Diaries and Papers of Thomas Farrar Whitley, Tonga, 1935–1938 (Salt Lake City: privately printed, 2004), 2.

[5] MHHR, April 11, 1907.

[6] Reuben M. Wiberg, “Abstracts from the Journals of Reuben M. Wiberg, Mission President of the Tongan Mission, 1933–1936,” January 17, 1934. CHL.

[7] Wiberg, “Abstracts,” January 18–21, 1934.

[8] Wiberg, “Abstracts,” January 22, 1934.

[9] Wiberg, “Abstracts,” January 27, 1934.

[10] Ermel J. Morton, 20th-Century Western and Mormon Americana, Perry Special Collections, 7–9 (hereafter cited as Morton notes), February 28, 1934.

[11] Morton notes, May 31, 1934.

[12] Paula F. Muti and Sisi K. Muti, Mosese L. Muti: Man of Service, 1911–1993 (Bountiful, UT: n.p., 2016).

[13] R. Lanier Britsch, Unto the Islands of the Sea: A History of the Latter-day Saints in the Pacific (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1986), 451.

[14] MHHR, May 12, 1936.

[15] Emile C. Dunn, interview by R. Lanier Britsch (typescript, 1978), 13, OH 499, CHL.

[16] Emile C. Dunn journal, March 19, 1936, MS 2786, CHL.

[17] Dunn, interview, 16.

[18] Ermel J. Morton, My Errand from the Lord: Tongan Missions, 1936 to 1957, comp. Lorraine and Arden Ashton (n.p., 2011).

[19] Morton, My Errand from the Lord, 61 (February 27, 1937).

[20] Morton, My Errand from the Lord, 61 (February 26, 1937).

[21] Ermel J. Morton, interview by Ken Baldridge (typescript, 1979), 27, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[22] Dunn, as cited by Britsch, Unto the Islands of the Sea, 454.

[23] See MHHR by date and Morton notes. For more details on Elder Smith’s visit, see Emile C. Dunn, “Elder Smith Visits Tongan Mission,” Church News, July 9, 1938, 5, reported by President Dunn; and “Meeting Houses of the Church in Tongan Mission,” Church News, January 7, 1939, 3. See also Fred E. Woods and Riley M. Moffat, “An Apostle Visits Tonga: The 1938 Mission of Elder George Albert Smith,” Mormon Historical Studies 19, no. 2 (Fall 2018): 60–83.

[24] Ermel Morton, Brief History of the Tongan Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Golden Jubilee (Suva: Fiji Times, 1968), 34. See also Tisina Wolfgramm Gerber, comp., Iohani Wolfgramm: Man of Faith and Vision, 1911–1997 (n.p., 2000), 49.

[25] Mosese Muti, interview by R. Lanier Britsch (typescript, 1978). See also full-length treatment of Muti’s life by Muti and Muti, Mosese L. Muti.

[26] Gerber, Iohani Wolfgramm, 49. See also MHHR, May 20, 1938.

[27] Morton, My Errand from the Lord, 184 (May 29, 1938).

[28] Gerber, Iohani Wolfgramm, 49. See also Dunn, interview.

[29] Evon Wesley Huntsman, “My Story Lest I Forget,” http://

[30] Dunn journal, May 31, 1938.

[31] Morton, My Errand from the Lord, 187 (June 5, 1938).

[32] Dunn, “Elder Smith Visits Tonga Mission,” 5. Rufus K. Hardy, “With Church Leaders in Tonga,” Church News, July 23, 1938, 1, 6. See also Woods and Moffat, “An Apostle Visits Tonga,” 60–83.

[33] Dunn, interview, 18. All of Elder Smith’s talks were recorded and included in the manuscript mission history.

[34] Dunn, interview, 20.

[35] Delworth Keith Young, “Liahona High School: Its Prologue and Development to 1965” (master’s thesis, Utah State University, 1967), 24.

[36] Gerber, Iohani Wolfgramm, 45.

[37] Morton, interview, 17. See also Brent R. Anderson, “A Gift of Tongues: Ermel J. Morton and the Translation of the Book of Mormon” (paper at Mormon Pacific Historical Society Conference, October 21, 2016).