Carrying On: The War and Afterward (1940-49)

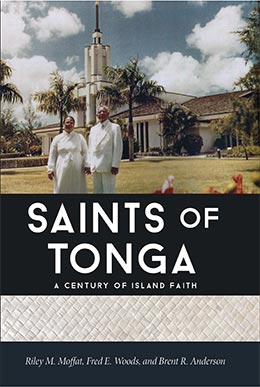

Riley M. Moffat, Fred E. Woods, and Brent R. Anderson, "Carrying On: The War and Afterward (1940-49)," in Saints of Tonga (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 165–198.

The 1940s began peacefully in Tonga, but soon war clouds from World War II began to gather, bringing challenges and opportunities for the Latter-day Saints in Tonga.

The new home for missionaries that Elder Thomas Wilding had started building on December 14, 1939, at Matavaimo‘ui was finished six weeks later, just before he sailed for home on the Matua. It had cost £225, or $1,096.

The mission history records that in mid-January 1940, Elder Ralph Hugh Lee was translating the Doctrine and Covenants and the Pearl of Great Price into Tongan and had already finished one hundred sections. It further states that on June 15 President Dunn and Elder Lee had secluded themselves on the small island of Nomuka Iki for a week, quietly revising 108 sections of the Doctrine and Covenants, and that the Pearl of Great Price translation was already finished. Elder Lee was released to return home on August 25, and nothing more was heard of his translations.

Makeke College opened on February 15 with eighty-five students. Elders Franklin Spencer and John Laudie were in charge. By late September, Elder Spencer was listed as the principal, and Efalame and Finau Wolfgramm supervised the students in the dorms.

While traveling to ‘Eua on September 10, Elders Teeples and Shepherd survived a shipwreck and arrived in ‘Ohonua with only the clothes on their backs. The captain, Ned Cook, reportedly wrecked his boat on purpose when entering the harbor because he was angry at being asked to transport the elders.

Recalling the warning of Elder George Albert Smith and receiving news of the war in Europe, President Dunn counseled the Tongan Saints in late 1939 to plant extra gardens as a form of food storage since many root crops could be left in the ground for a few years.

Elders Are Withdrawn

The mission was dealt a serious blow on October 15, 1940, when they received a cable from the First Presidency that required all foreign missionaries to evacuate to the United States as soon as possible since war clouds loomed over the world. The cable read:

Having in mind possible developments, please make necessary boat reservations and return all elders to the United States as soon as possible in American ships where available. We will try to facilitate reservations from this end. Install local officers to take charge of branches. Send elders in as large of groups as possible, properly organized and officered. We urge the strictest possible conduct and caution against political controversies. The President of the Mission will remain for the present using his own discretion whether his family will remain with him or return now.[1]

Rumors quickly spread that all U.S. citizens were being called back to the United States to enlist in the army and that the Church would be discontinued and would die, leaving only Makeke College. On hearing this, William Parsonage, director of education for Tonga, asked to inspect Makeke as soon as possible. When he came out to Makeke on October 17, he spoke very highly of its program, students, buildings, and grounds. He said that without a doubt, the boys that were sixteen years of age would receive a grant-in-aid that would exempt them from the payment of half the poll tax that each male sixteen and over owed each year.[2]

When British Consul Arthur C. Armstrong heard the rumors, he expressed hope that President Dunn would stay. He extended the cooperation of the British Navy wireless station in helping President Dunn make emergency travel arrangements. Ten elders needed to be notified and evacuated. Elders Teeples and Shepherd would be released to go home because they had served more than twenty-four months. The other eight would be transferred to missions in the United States. Most of them ended up finishing their missions in Hawai‘i. It took a few days to notify the elders in Ha‘apai and Vava‘u to gather in Nuku‘alofa. Tearful feasts were prepared, and Charles Sanft composed a special farewell song. All the elders were gathered in Nuku‘alofa by October 20.

The Mission History and Historical Reports recorded the sorrowful scene at the special missionary meeting held on October 22: “The meeting was a very sad occasion. The elders had a hard time to speak, but they all bore strong testimonies to the truthfulness of the Gospel. Although they would much rather stay until their time expired as missionaries they are all willing to abide by the instructions of the Prophet of the Lord in sending them away from Tonga. They all expressed their appreciation of the opportunity to spend as much time as they have done in the Tongan Mission.”[3]

President Dunn and his family chose to stay with the Saints in Tonga, and arrangements were made with the help of the British consul in Tonga, Arthur C. Armstrong, for the ten departing missionaries to leave Tonga on October 24 for Samoa on the Matua. Morton recounts in his history:

The Saints turned out en masse to bid farewell to the ten departing elders. The wharf was filled as the boat pulled away at 5 p.m. The mission record described the scene: “It was indeed a sad occasion. The Saints cried so hard that it was almost impossible for them to sing and the elders had in their hearts a grief that no one knows unless he has gone through such an experience.” The boat pulled out leaving Mission President Emile C. Dunn with Sister Evelyn Hyde Dunn and their three children Hyde, Karen, and ‘Ofa alone to carry on with the Saints the work of bringing the Gospel to the Tongans.[4]

The Matua only got them as far as Apia. The elders from both the Tongan and Samoan missions boarded a tugboat for a stormy overnight passage to Pago Pago. On the tugboat they were relegated to the deck with no railings. They had to find something to hold on to in order to avoid being washed overboard.[5] Upon reaching Pago Pago, American Samoa, they joined with missionaries from Samoa, New Zealand, and Australia to sail on the Monterey for Hawai‘i. Some elders were assigned to Hawai‘i, others to mainland missions, and others released to return home.

Many Tongans from the queen on down wondered why the mission was being discontinued and whether the Church would die. “However, nowhere in the southwest Pacific did the removal of the elders have less effect upon the Church and its continued progress than in Tonga.”[6]

The same day the missionaries sailed, President Dunn kept a prearranged appointment to visit with Queen Salote to present her with a lovely Navajo Indian blanket, a gift from Elder George Albert Smith. The queen commented that some of the designs on the blanket had significance to Tongans. They talked for an hour, and President Dunn explained why the missionaries were leaving. “The missionaries were being withdrawn, he explained, because the prophet had been inspired to call them back.”[7]

Local Saints Step Up Again

President Dunn immediately began touring the mission to reorganize the districts and branches under local officers and put things in order for the foreseeable future. He called Tevita Mapa as president of the Tongatapu District, Vuna F. F. Wolfgramm as president of the Vava‘u District, and Tevita Finau as president of the Ha‘apai District, and they in turn each chose two counselors. Every district, branch, and auxiliary organization was staffed by local Tongan members. This need to call upon native members to fill leadership positions was not new; it had happened before when there was a severe shortage of foreign elders during the Passport Act and Wiberg era. By and large, the local members stepped up to the challenge, and the reorganization was completed by the end of November.

With the departure of the elders, the Form 6 students at Makeke were moved in to Nuku‘alofa so Sister Dunn could help prepare them to take the government exam, which four of the six students passed. Makeke College continued with Samuela Fakatou, Tevita Pita, Siaosi Balauni (George Brown), and Sister Evelyn Dunn as teachers. When Makeke opened for the 1941 school year, Sione Tuita was the principal.

Otherwise the war in Europe had little effect on Tonga at this time, though President Dunn continued encouraging the Saints to plant extra gardens to be ready for any emergencies. One of President Dunn’s greatest challenges was training the native Saints in record keeping, which previously had been done by the foreign missionaries. He called secretaries in each district and branch and had them trained in this important work. At the end of 1940, there were 1,866 Latter-day Saints in Tonga, and thirteen local couples were serving as missionaries.

As 1941 dawned, President Dunn started calling strong couples as missionaries and assigned them to branches that needed their leadership. These couples were to be provided a Tongan fale to live in and a garden spot during the period of their assignment as branch presidents. Throughout the war, President Dunn kept an average of fifteen native couples in the field, and convert baptisms continued.

One such faithful missionary couple was Muli and Le‘o Kinikini from the island of ‘Uiha in Ha‘apai. Muli was called to go to Koloa in Vava‘u to serve as the branch president in 1941. One Saturday while Muli and his boys were out fishing, Sister Vika Fatafehi, who was over one hundred years old, died. Nevertheless, Muli was inspired to go and bless her to live, which she did. But the next day, chiefs and relatives who had come for the funeral were convinced that Vika would not live and so were staying for the funeral. Muli was inspired by the Spirit to tell these people that Vika would not die and that so long as he was serving as the branch president in Koloa, no Latter-day Saint would die. None did. The faith and sacrifice of men like Muli Kinikini showed the people of Tonga that even without the elders from overseas, the native Tongan elders held the power of the priesthood and knew how to use it. The Kinikinis were next called to serve in ‘Otea to revive that branch, which they did through a series of humble healings and faithful service.[8] With the Kinikinis at ‘Otea, the branch grew from just two or three families to one of the largest branches in the mission.

Then came the Japanese attacks of December 7, 1941, on Pearl Harbor and elsewhere in East Asia. Now the war became closer. The next day all Germans and Japanese in Tonga were interned. Fearing attack on Nuku‘alofa, the government evacuated the citizens of Nuku‘alofa out of the city and into the country. As the Dunns were preparing to move out to Makeke in mid-December, British Consul Armstrong notified them that all European and American women and children were required to leave Tonga. Sister Dunn and her children left for New Zealand on December 20, where they were put up at the mission home in Auckland by the mission president there, Matthew Cowley, and his wife. From then on, all major Church meetings were held at rural Makeke in a large Tongan fale, sometimes under blackout conditions. Cottage meetings needed to be scheduled in the afternoon. Under the direction of mission Relief Society president Sulia Tu‘iketei, members celebrated the one-hundredth anniversary of the Relief Society, meeting in a Tongan fale that could seat five hundred in the nutmeg grove at Makeke. By December 1941, Makeke was on its own without the help of any expatriate missionaries, and it operated effectively with local teachers carrying forward the program.

Effects of the War

On March 23 J. K. Brownlee, secretary in the government, notified President Dunn that the government wanted to use the mission home to billet some soldiers from the United States. Dunn agreed to the request, but he would allow only officers to live there. On April 20, 1942, an American fleet, including the aircraft carrier USS Yorktown and twelve other ships, anchored in Nuku‘alofa harbor and began off-loading troops and supplies. Two days later a Colonel Rice came to see President Dunn about billeting officers in the mission home. President Dunn moved the Church records and materials over to the chapel and made his home there for a time while the American officers stayed at the mission home. With the members in Nuku‘alofa evacuated to the countryside, no one was using the chapel. President Dunn eventually moved out to Makeke to help teach school. By August 9 as many as forty-three warships were anchored in the harbor. The queen and her two sons moved to her estate at Fua‘amotu, and during emergencies they went to a cave under the hill by the ocean. Her husband and consort, Prince Viliami Tungī Mailefihi, who had been one of the Church’s most vocal opponents, had passed away July 21, 1941.

With the overnight influx of soldiers and sailors, Tonga—and Nuku‘alofa in particular—was transformed. Natives were employed or commandeered to help the military. On May 12, 1942, the U.S. Army told President Dunn he was to be in charge of hiring native labor for the army. Dunn said he didn’t have time, but the army said he had no choice. Dunn turned to his most dependable Church members to work for the military. One was Iohani Wolfgramm, who worked as the lead carpenter in building army hospitals at Houma and Fua‘amotu. The army released Dunn from this duty after one month, but he was kept on as a translator. Money flowed freely, and the interaction with the U.S. military changed Tongan society in many ways, both good and bad.[9]

During this occupation, President Dunn continued holding district conferences more or less on schedule as transportation would allow. At a conference on Ha‘apai held March 28, 1942, the high chief Siake “Jack” Lolohea, who had been a great help to President Smith in 1917 in establishing the Church in Ha‘apai, attended the conference and spoke, relating many experiences when the Church first came to Ha‘apai.[10] President Dunn received a letter from the First Presidency on July 3, expressing their hope that he could stay on in Tonga and assuring him that his family would be taken care of in New Zealand.

During this time, the other churches in Tonga closed their schools, but President Dunn was determined to keep Makeke open. He felt it was important to keep the students out in the country and away from the negative influences of the military. He claimed that he didn’t lose a single student. Enrollment at Makeke rose to 143, the highest ever. President Dunn moved out to Makeke and became one of the teachers. Other teachers in 1943 were Sione Tuita, the principal, and Sinisa Fakalata, along with Paula and Lesieli Malupō, who supervised the students. When the school needed a new well, the U.S. Navy dropped off some dynamite to blast one.[11]

As the war situation evolved, the evacuation order for white women and children was lifted. Sister Dunn and her children returned to Tonga on February 13, 1943. Most of the American soldiers were moved closer to the action. The order evacuating Nuku‘alofa was also lifted. As the members moved back, they were able to start holding meetings at Matavaimo‘ui again.

At the height of the occupation, ten thousand soldiers and two thousand sailors were stationed on Tongatapu. A large hospital was established in Houma. One outcome of the occupation was that many Tongans made good money working for the military. Among the military were a few Latter-day Saint men who participated in Church services and activities as they could. They shared their testimonies and were a good example to the local members. Many were returned missionaries. These were the first foreign members who were not missionaries that most Tongans had met. On the other hand, a negative impact noted by President Dunn was an increase in alcohol and tobacco use, home brew, stealing, gambling, and immorality.[12]

Iohani Wolfgramm, a missionary and a branch president at Fo‘ui (1942–43), recalled that he received lots of surplus food and supplies from the military. Sadly, his little daughter Tisina was hit by an army jeep. Her head was crushed and she died. The Spirit told Iohani that little Tisina would not be with him that night but would return tomorrow and to wait to give her a blessing. He felt ready to bless her at three o’clock in the morning, and as the sun rose, Tisina was completely healed by the power of God through an inspired priesthood blessing offered by her father.[13]

Iohani and his wife, Salote, were asked to assume leadership of the Halaloto Branch when their relatives Samuela and Heleine Fakatou were called to go to Niuatoputapu in 1943. By that time at least fourteen Latter-day Saint families who had evacuated Nuku‘alofa were living in the Halaloto area. Samuela and Heleine Fakatou had a large garden with nine rows of each crop for them and one row for tithing. Iohani put the money Salote earned by cooking and doing laundry for the soldiers in a savings account they had been using since 1934 to save for a temple trip.

As the war progressed and Tonga was no longer in the path of danger, the U.S. military began to withdraw. They left behind much of the equipment they had brought. It was initially offered to the Tongan government for ten cents on the dollar, but the British consul advised that they wait because they could eventually get it cheaper. Instead the army built a ramp behind Makeke on the low sea cliff and drove their vehicles and machinery off into the ocean in May 1944.

On December 27, 1943, as Tevita Mapa’s son, Penisimani, prepared to leave for Fiji to attend the medical college there, he was set apart as a missionary to Fiji and was authorized to hold Sunday School in Suva with the few Tongan Latter-day Saints there such as the Cecil Smith and Mary Ashley families. His father, who was the captain of the queen’s guard and secretary to the premier, passed away on January 15, 1945. He had been serving as the president of the Tongatapu District. Tevita Mapa had turned down Queen Salote’s offer to accept the noble title of Ma‘atu if he would renounce his affiliation with the Church.[14]

Missionary Work in the Niuas

Missionary work was not forgotten even during the chaos of the war, and a significant number of individuals were converted in the far northern islands during this time. President Dunn made sure strong missionaries were sent to support the small branch on Niuatoputapu and to open up Niuafo‘ou. President Dunn was able to find transportation up to Niuafo‘ou on December 15, 1942, where he met two men, Haiane and Lea Kehe, who they said had been baptized in 1896 by Elders Welker and Smith. These men hadn’t seen anyone from the Church since that early time when Tonga was under the Samoan Mission.

Dunn called Samuela and Heleine Fakatou on a mission to Niuatoputapu on March 21, 1943, but they were not able to find transportation there until June 16. When they finally arrived, the ministers and chiefs declared that Elder Fakatou was a false prophet and a devil and counseled people not to listen to him. But eventually, through his kind spirit and dedication, he made some friends.

Landing at Niuafo‘ou. Maurice Jensen collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Landing at Niuafo‘ou. Maurice Jensen collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Some time later the branch president, Elder Fakatou, along with twenty-four other members sailed six days to attend the June 1944 district conference on Vava‘u. On July 2, while at the conference, Elder Fakatou and his wife, Heleine, were reassigned to serve on Niuafo‘ou. President Dunn instructed them to take enough food to last six to twelve months because the volcano on Niuafo‘ou had destroyed much of the crops and livestock in 1943, and the mail was delivered only every six to twelve months.

When the Fakatous arrived on Niuafo‘ou, Samuela encountered a former classmate from the Maori Agricultural College who, in the absence of a Latter-day Saint presence on the island, had become a Methodist preacher, though he still taught gospel principles. They also found Vaha‘i Tonga, a faithful member who had recently been sent by the government to run the government school there. When President Dunn learned of the appointment, he set apart Brother Tonga and his wife, Sela, as missionaries before their departure but told Brother Tonga, “Don’t say anything about the Church for six months until they get to know you.” However, he was soon recognized by some of his old classmates from the government’s Tonga College, so he started holding cottage meetings right away. Brother and Sister Tonga stayed on Niuafo‘ou for three years.[15]

Niuafo‘ou was experiencing a famine at the time, and Vaha‘i Tonga wrote to President Dunn requesting food for the Saints. After it arrived, Brother Tonga wrote back to President Dunn that the food sent by the mission had preached a strong sermon to the people and softened a few hearts.[16] On October 18 Elder Fakatou restored the life of Patisepa, the daughter of the chief Malu‘amaka of Niuafo‘ou, after she had been pronounced dead by a doctor. This miracle showed the power of the priesthood of God and opened more doors to the preaching of the gospel. Then on November 23, 1944, the volcano on Niuafo‘ou erupted again.

Less than a week later, President Dunn visited Niuafo‘ou and wrote a detailed history of missionary work on that island for the Church News. In it he related:

Very little had been done by missionaries on this island until the past year. In the year 1894, two elders were sent from Nuku‘alofa to preach the gospel to the people. They did a lot of preaching, organized a school at the village of Sapa‘ata and baptized ten people. For some reason it was decided to give Tonga up, as a part of the Samoan Mission, and the missionaries were all called to return to Samoa from Tonga.

A few years later the Tonga Conference of the Samoan Mission was reopened, with headquarters at Neiafu, Vava‘u. In the year 1910, two elders were sent to Niuafo‘ou to continue the work there. The missionaries were again successful in baptizing another ten people, and they established a school at the village of Tongamama‘o. The work continued there until 1912, when the elders were called away to keep up the work in Vava‘u, Ha‘apai, and Tongatapu.

No more missionaries were called to Niuafo‘ou until September 1943. At that time I called as a missionary, Malakai Nukumovaha‘I [Vaha‘i Tonga], a young man who was being sent to Niuafo‘ou as a school teacher for the government. With him were his wife, Sela, and two native elders, Simote Fusitu‘a and Sione Esau Loloa.[17]

The ministers on Niuafo‘ou continued forbidding people to listen to the elders. As Elder Fakatou was preaching at a street meeting in Angahā on February 19, 1945, the Niuafo‘ou Catholic band started playing loudly to interrupt his sermon. Some people in the crowd tried to start a fight, but Samuela just read the Bible to them to settle the crowd. Twice he was threatened with death for preaching the gospel. At a cottage meeting one night in the village of Mu‘a, an angry mob surrounded the house and shouted, “Let’s kill the Mormons.” The leader of the mob barged in and knocked down Elder Fakatou. The rest of the crowd rushed in and accidentally knocked over the lantern, the only source of light. In the melee and darkness the elders escaped, and the mob, unaware of the escape and thinking their leader was Elder Tonga, beat their leader severely. He died three days later.[18] Despite those challenges, the missionaries eventually established missionary homes at Mu‘a and Tongamama‘o on Niuafo‘ou. Elders Fakatou and Tonga were able to baptize strong converts such as Solomone and Salome Ulu‘ave.

Even after the war ended, the Dunns decided to stay at Makeke because there were no other expatriate missionaries to help teach. Brother Mosese Muti was called to replace President Dunn as principal of Makeke on April 9, 1945, and Fa‘alupenga Sanft came from Vava‘u to be the matron of the girls’ dorm.[19] Brother Muti was a stern but loving leader who had attended the government college from 1927 to 1932. He served three missions at Makeke.

President Dunn asked for more missionaries now that the war was over, but the government, influenced by the other churches, was slow to consider issuing landing permits. Throughout the Pacific an anticolonial movement spread among the various island territories along with the desire to limit the influence of foreigners. On July 18, 1947, Elder Matthew Cowley, now an Apostle, shared his thoughts with leaders in Tonga about the antiwhite sentiments in the islands’ governments. He understood the larger picture in the Pacific island and doubted that Tonga would get more missionaries anytime soon.[20]

Evon Huntsman Replaces Emile C. Dunn

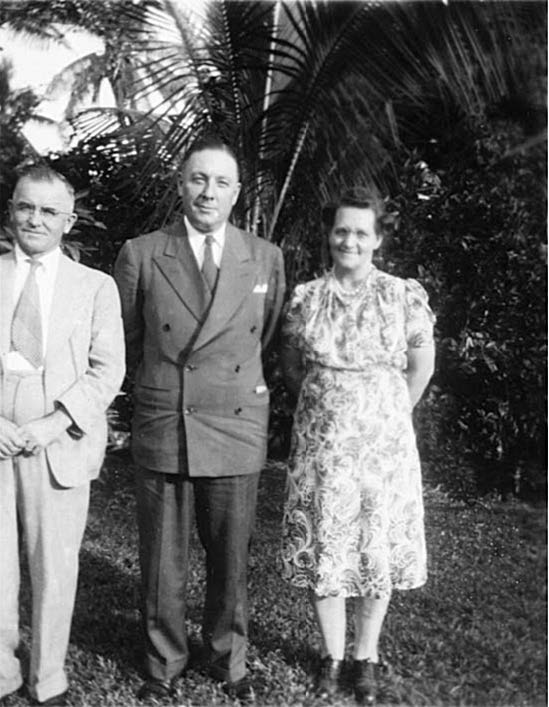

President Evon and Sister Martha Huntsman. Evon Huntsman collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

President Evon and Sister Martha Huntsman. Evon Huntsman collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

While communications and infrastructure were generally improved with a new airport and better docks, the war had disrupted commercial shipping and the availability of consumer goods. The slow return to normalcy also affected the Church. It wasn’t until June 7, 1946, that missionaries were able to return. On that day, President Evon Huntsman and his family and Elder Liddell Roberts and his family, both former missionaries in Tonga, arrived to replace President Emile Dunn and his family. The Dunns had served in Tonga for ten years as mission president, with six of those years as the lone foreign representatives of the Church. President Huntsman had served as a missionary from 1912 to 1915, and Elder Roberts from 1935 to 1938.

One of the first things President Huntsman wanted to do was to become familiar with all areas of the mission; he had been away for thirty-two years. He took Elder Roberts up to the northern areas, including Niuatoputapu and Niuafo‘ou. On Niuafo‘ou, a Catholic island, they felt an unfriendly spirit, and when they were leaving, the crowd began mocking them. When they were getting into the rowboat to go out to the Hifofua, several men jumped into the little boat and tried to sink it, saying, “Here is where we will drown the Mormons.”[21] Two days after they left, on September 9,1946, the volcano on Niuafo‘ou erupted, destroying some villages and covering much of the land in lava, including the Catholic church, school, and government buildings. In December 1946 the government decided the entire island had to be evacuated, and the island’s twelve hundred inhabitants were compelled to leave everything behind. President Huntsman encouraged the Saints to treat the evacuees with kindness. Most ended up being relocated on the island of ‘Eua near Tongatapu. During their tour they also located 600 members in Vava‘u and 450 in Ha‘apai.

Evon and Martha Huntsman present Queen Salote with the Tongan Book of Mormon. Evon Huntsman collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Evon and Martha Huntsman present Queen Salote with the Tongan Book of Mormon. Evon Huntsman collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

The Church had not only survived but had grown stronger through the faith and devotion of the members, even without the support of foreign missionaries. When the Dunns returned to Utah, they reported to the First Presidency that Tonga was organized into three districts and twenty-eight branches, all led by native brethren who were doing an outstanding job. There were meetinghouses on nine islands. Makeke College had 140 students between the ages of thirteen and twenty-one, and it was largely self-supporting. Its graduates were among the leaders of the Saints, having been well instructed in the principles of the gospel.[22]

After the war, the antiforeign attitude manifested itself when President Huntsman asked for landing permits for new elders. Elders John Laycock and Bevan Blake reached Tonga on July 9. Soon after they arrived, the landing permits for five more elders were granted and then revoked. Two days later the Tongan government decided to limit the number of foreign missionaries for all churches to a ratio of one per two thousand members. This meant just one missionary for the 2,422 Latter-day Saints in Tonga would be allowed. On the surface this may have looked fair for all, but it really was enforced only for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The government would eventually permit the presence of three full-time proselytizing missionaries plus the mission president, a limit they imposed for many years. No amount of pleading with the queen, her son (Prince Tungī, then the crown prince), the premier, the British consul, or the Parliament would change the policy. However, on July 9 the Parliament voted fifteen to five to allow more missionaries, but that vote was overruled by the queen’s cabinet. On July 28 there was a mission-wide fast to soften the hearts of the government leaders to allow more missionaries to come. Premier Ata told President Huntsman on September 9, 1946, “The Tongan people are Christianized and therefore need no more European missionaries.”[23] The government’s view seemed to be that Tonga was already a Christian nation and that foreign proselytizing missionaries were not needed. President Huntsman felt that the reason he was having a hard time arranging landing permits for new elders was that the Wesleyan Church heavily influenced the government and didn’t like the competition.[24]

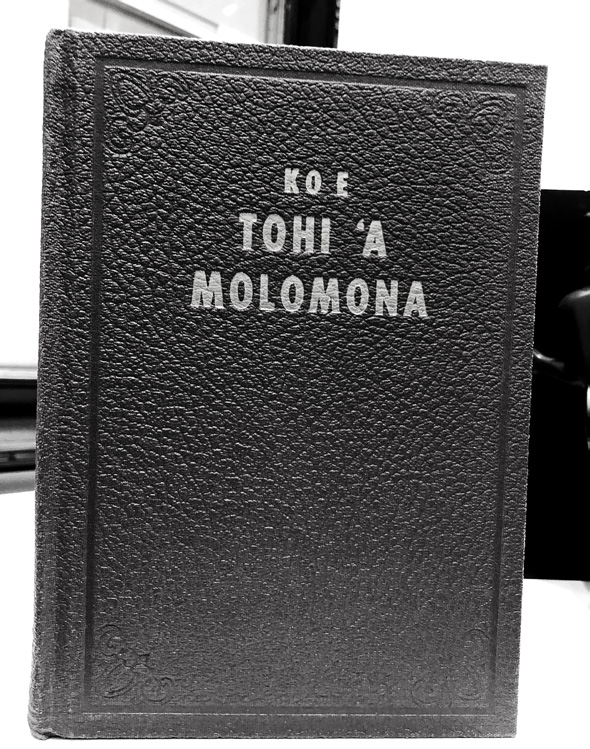

Cover of the first edition of the Tongan Book of Mormon. Courtesy of Reed Moon.

Cover of the first edition of the Tongan Book of Mormon. Courtesy of Reed Moon.

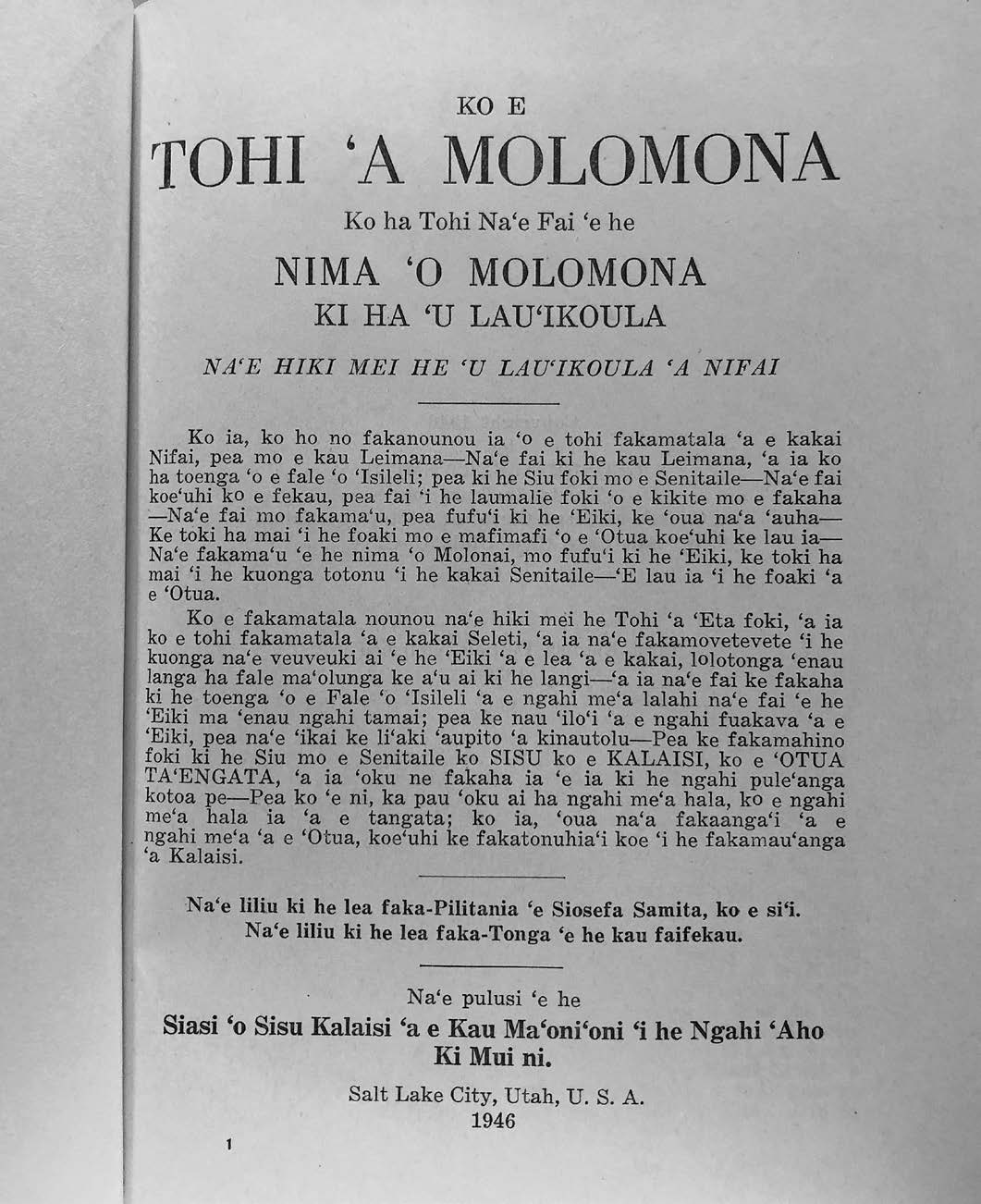

Title page of the first edition of the Tongan Book of Mormon. Courtesy of Reed Moon

Title page of the first edition of the Tongan Book of Mormon. Courtesy of Reed Moon

Linked to the issue of foreign involvement in island affairs was the experience of native governments that foreign missionaries and advisors tended to act in a paternalistic fashion and look down on local leaders. Latter-day Saint missionaries were occasionally guilty of some of these same prejudices, though to a much lesser degree. The gospel taught that all men were brothers, yet the Brethren had advised caution in extending the priesthood to native converts. The practice of having young, inexperienced missionaries called to supervise older, more experienced local leaders seemed illogical. However, government quotas on foreign missionaries forced the Church to extend leadership callings to local leaders much faster than in other missions, and in the vast majority of cases the local leaders magnified their callings.[25]

Amid this pleading for more missionaries, President Huntsman met with Queen Salote on September 10 to present her with a specially bound black leather copy of the recently published Book of Mormon in Tongan, titled Ko e Tohi ‘a Moromona, which had been promised to her eight years before by President George Albert Smith and was inscribed by him. Huntsman then had his photo taken with the queen. President Huntsman also took specially bound copies of the Book of Mormon to Prince Tungī and Premier Ata, who dodged the subject of landing permits.

The lack or shortage of foreign missionaries was not as severe a problem as it could have been. The Tongan Saints had not only survived but even thrived during the six years they had been left largely to their own devices. They had filled all the leadership positions in the mission, and missionary work had moved forward; strong converts had been baptized, and new areas had been opened. They loved the foreign elders but knew they could stand on their own feet.

On November 8, Rudy Wolfgramm and his wife, Edna, came for a visit from America on a three-month visitor’s visa. They became a great help to the mission. Rudy had gone to the United States with President Wiberg in 1936 to attend Brigham Young University and became a naturalized citizen. He joined the military and fought in the Pacific during the war, then brought his wife to Tonga on a visit. When the Wolfgramms’ visa was about to expire, Elder Laycock suggested to President Huntsman that he would be willing to transfer to Hawai‘i to allow the Wolfgramms to stay in Tonga as missionaries. President Huntsman agreed, and Elder Laycock sailed for Hawai‘i on February 22, 1947.

The Situation at Makeke

In 1946, when President Dunn returned to Salt Lake City after the war had ended, he told President McKay that what Tonga needed most was a good school and that the Church should either renovate Makeke or build a new school. President Dunn thought that if the Church could supply the materials, the local Saints could build it just like they had always done in the past. When Salt Lake City hesitated to spend more money in Tonga, President Dunn reminded President McKay that he wasn’t asking for very much compared to the one million dollars being spent on a new gym at Brigham Young University and that the Tongans deserved it. The money was approved within a week.

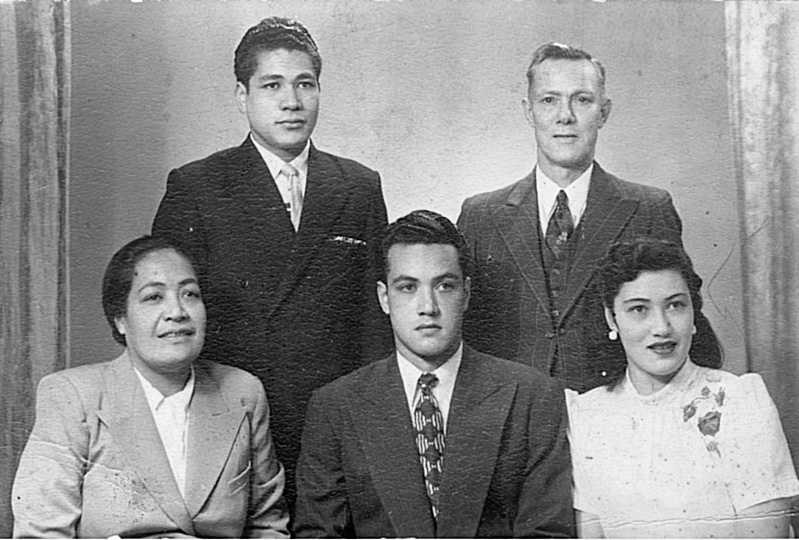

President Evon and Sister Martha Huntsman, Elder Bevan Blake, Elder Rudy and Sister Edna Wolfgramm. Evon Huntsman collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

President Evon and Sister Martha Huntsman, Elder Bevan Blake, Elder Rudy and Sister Edna Wolfgramm. Evon Huntsman collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

When President Huntsman arrived in Tonga in June 1946, he said that Makeke was in poor condition because of the lack of supplies during the war.[26] After Huntsman dropped off the Dunns at the airport, he drove past Makeke and was saddened to see the children eating a meager meal of yam, or taro.

President Huntsman recorded his thoughts on Makeke as he became reacquainted with Tonga:

We visited over the main island with President Dunn for a few days, then he left and we were officially in charge. One of the first visits mother and I made, was out to Makeke Plantation where our Mission School was located and was in the hands of native teachers, who were doing their best to keep it alive. The Elders from Zion had been evacuated from all the Pacific Missions because of the war and we and the Roberts family were the first to come out after the war. We found the school in poor condition. The buildings were mostly of native construction and they were leaking and unclean and the some 75 students were poorly fed and cared for. On our way back to the Mission Home . . . we discussed the conditions at the school and I said as soon as I could get a letter off to the First Presidency, I was going to request a better school, or I would close Makeke down and send the boys and girls back to their homes.[27]

Elder and Sister Roberts were assigned to teach at Makeke. The school was a bit run down, but the rugby team had not been beaten in three years. When school started in February 1947, Elder Bevan Blake was the principal along with his companion, Elder Rudy Wolfgramm. They were the only foreign missionaries allowed in the kingdom besides the Huntsmans and the Roberts.

Finding a Site for a New School

President Huntsman spent the next several months looking for a larger site for a school. All the land in Tonga was controlled by the nobles and the government, and they were not willing to help the Latter-day Saints in any way. He was turned down in every instance.

Frank and Vangana Cowley and family. Pauliasi Vainuku collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Frank and Vangana Cowley and family. Pauliasi Vainuku collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

On the evening of February 19, 1947, just as he was about to give up hope, a less-active Latter-day Saint Tongan woman who was married to a European businessman named Frank Cowley came to the mission home. She said she had heard that the Church was looking to buy a plantation. She said they owned the lease on 375 acres at Halaloto in central Tongatapu and wanted to sell out and move to New Zealand. They offered the lease of the land, which included 100–150 acres planted in coconut palms, as well as ten horses and seventy to one hundred Angus cattle for £10,000, or $33,000. According to Huntsman’s later account, when President Smith was in Tonga in 1938, he had driven past the Cowley plantation on June 3 and remarked, “This is where I would like to see the Church obtain some land.”[28] President Huntsman immediately accepted the offer. The next day President Huntsman, with Elders Liddell Roberts and Rudy Wolfgramm, went out to survey the property. Huntsman said the property comprised about 276 acres (150 acres in coconuts and 125 in virgin bush), seventy-one head of Poll Angus cattle, nine horses, and three carts.[29] Concerning these events, President Huntsman wrote, “After much careful thought and prayer, and having tried all other leads whereby we might lease or purchase some land without success we decided to send a request and recommendation to the First Presidency to buy the plantation so that the school might be improved and have sufficient land to raise gardens on.”[30]

Yet making arrangements to finalize the deal between Tonga and Salt Lake City took time. A letter from the First Presidency arrived on March 20 approving the renovation of Makeke, pending the purchase of the Cowley plantation. A month later, a letter arrived granting $138,000 to build a new school and to find more land to support the boarding students. In the meantime, other churches offered the Cowleys more money, and the government threatened that they would not renew the lease when it ran out in fifteen years. President Huntsman was afraid the deal would fall through, but the Cowleys kept their word. President George Albert Smith cabled Huntsman, “Please close the lease as soon as possible. The Lord will take care of His affairs in His own time.”[31]

Eventually, Havea, the Tu‘i Ha‘ateiho and minister of lands, helped President Huntsman secure the lease. In a meeting with Havea in mid-April, he said the transfer of the lease could be made. Then a week later, President Huntsman and Frank Cowley signed a temporary agreement in the office of Mr. Brownlee, the government secretary. With this in hand, President Huntsman assigned Samuela Fakatou and Siosaia Hola to be caretakers of the property. The area of the Cowley plantation was known as Fualu and was part of the noble Lavaka’s estate.

Visit of Elder Matthew Cowley

Elder Matthew Cowley, a new apostle and supervisor of the Pacific-area missions, arrived on June 15, 1947. He visited Makeke, then he and President Huntsman visited the minister of lands, the Honorable Havea Tu‘i Ha‘ateiho, to talk about the lease of the Cowley plantation. The minister of lands was supportive and was pleased the Church was buying the Cowley plantation for a school. Three days later, Elder Cowley inspected the plantation and was impressed with what he saw. He cabled Salt Lake City, requesting them to send the money to pay Mr. Frank Cowley.

President Evon Huntsman, Elder Matthew Cowley, and Sister Martha Huntsman. Evon Huntsman collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

President Evon Huntsman, Elder Matthew Cowley, and Sister Martha Huntsman. Evon Huntsman collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

At a mission conference held on June 22, Elder Cowley told the Saints: “Here we’re buying a new plantation from the tithing of our people. . . . And God will expect you to pay more tithing than you’ve ever paid before because you’re receiving more tithing in this land; and if you don’t pay your tithing the time will come when this will not be a blessing to you but will be a curse. The day will come if you obey this principle of the Gospel that even the government of this land will look to this people for leadership.”[32] Nineteen hundred people attended this conference; about half of them were members of other faiths.

Elder Cowley then went to visit the queen and Prince Tungī and was quite impressed with them. Because of Elder Cowley’s experience throughout the Pacific, he saw the situation with the Tongan government in a different perspective. Elder Cowley admonished the Tongan Saints to avoid religious prejudice and support the government as the twelfth article of faith encouraged. “If you will support one another in your positions and your work in the church, you won’t need many missionaries out here from Zion, for you have the same priesthood as the elders do that come from Zion, and God will have his spirit with you if you are following the principles of the priesthood.”[33] He also told the Saints that “your school is your greatest missionary.”[34]

After the mission conference, the Vava‘u and Ha‘apai Saints went to the Cowley plantation to help clean the property while waiting for boats to take them home to their islands. While there, they processed five tons of copra. President Huntsman organized a building committee to plan the school, with Charles Wolfgramm and Rudy Wolfgramm as members and Harry Percival (Hale Vete) as secretary. The First Presidency approved the purchase for the construction of the new school.[35] This new school was to be a fully modern school, the likes of which Tonga had never seen.

Moving from Makeke to Liahona

At the Tongatapu District conference on August 29, President Huntsman declared that the school should move into a temporary setup at the new location as soon as possible. He wanted to have the school open for the 1948 school year. The following week, they moved the schoolhouse at Makeke to the new site and began building several Tongan fale to temporarily house the students.

The first recorded mention of the name Liahona was at a general priesthood meeting held on June 4, though President Huntsman said he chose the name on April 28. He said, “I chose the name because of its meaning hoping it will accomplish the same results for the Tongan people that the Liahona did for their forefathers in Book of Mormon times and that was [to] lead them aright whenever they were doing aright and in possession of the Spirit of the Lord.”[36]

On November 29, 1947, Elder and Sister Emile Dunn and their two children arrived for their third mission to Tonga, only a year and a half after being released as mission president. Elder Dunn’s assignment from Salt Lake was to supervise the construction of the new mission school. He quickly went to work, surveying the site for the school with President Huntsman on December 2. Elder Dunn recalled that the government hesitated to issue building permits, thinking that they would just take the property back when the lease ran out in 1961.[37]

After the lease was signed, Makeke students got busy cutting copra on the plantation to help pay the lease. The first Church services on the property were held in early July. The transfer of the lease of the Cowley plantation to the Church was officially recorded on August 28. In September the fale that were used as dorms at Makeke were moved to Liahona, and others were built. The three new fale to be used as classrooms, built in January 1948, were large, measuring 125 by 25 feet. The wood-frame schoolhouse at Makeke was moved to the village of Ha‘ateiho as their branch chapel.

On February 15, 1948, Makeke College opened its temporary facilities at Liahona with seventy-five boys and thirty-four girls. The first faculty at Liahona consisted of Elder Bevan Blake as principal and as teachers Rudolph Wolfgramm, Sione Filipe, Vaea Tangitau, Fauniteni Ikaukolu, Siaosi Loiti, Viliami Pasi, Fa‘alupenga Sanft, and Nafetalai ‘Alusa, who also supervised the boys and the plantation, and Fa‘alupenga Sanft, who supervised the girls.[38] By 1971 only a cistern and a caretaker’s house remained at Makeke, which had become a Church welfare farm.

As difficult as the government’s attitude had been toward the Church, much progress was being made. Church membership had increased from 2,395 in 1946 to 2,589 in 1947, and the number of missionaries, almost all Tongans, had increased from twenty-three in 1946 to forty-four in 1947. This growth in the Church necessitated that Tongatapu be divided into two districts, the Hihifo and the Hahake, which was effected at the district conference on December 26, 1947. Twenty-four branches were just too many branches for one district to supervise. Lisiate Talanoa was named president of the Hihifo District, which included the Nukunuku, Fo‘ui, Fahefa, Matahau, Fatai, Houma, Ha‘akame, Halaloto, Liahona, ‘Ohonua, Ha‘atu‘a, and Tokomololo Branches. ‘Ohonua and Ha‘atu‘a were in ‘Eua. Misitana Vea was called as president of the Hahake District, which included the Nuku‘alofa, Ha‘ateiho, Vaini, Loto Ha‘apai, Malapo, Mu‘a, Kolonga, Nakolo, Fua‘amotu, and Makeke Branches. A belated Christmas present was the delivery of 504 copies of the new Tongan-language Book of Mormon on January 9, 1948.

Elder Matthew Cowley paid another visit to Tonga in April 1948 and encouraged the Saints to “try and help build the college and then to utilize it and get the benefits from it for which it is intended, that of teaching our young people to live proper lives and to know of the truths of the gospel.”[39] The priority for the Church in building Liahona was not just to provide a secular education but to build testimonies, character, and leadership, similar to the priority at the Church College of Hawaii, which came later. A good secular education would allow students to better utilize those first priorities, according to Elder Cowley.

Emile C. Dunn Replaces Evon Huntsman; Building Liahona

On July 13 President Huntsman was released after two years to take his wife back to America to receive treatment for a serious tropical disease; he also took Elder Roberts and his family with him. Emile Dunn, who was supervising the construction of Liahona, was called to replace him as mission president. This was his second term as mission president. President Dunn went to Fiji in September to be set apart by Elder Cowley. This meant that President Dunn was supervising not only the building of the big new school at Liahona, probably the largest construction project in the country, but also the affairs of the mission.

Elder Matthew Cowley laying the

Elder Matthew Cowley laying the

cornerstone of Liahona College. Evon Huntsman collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

The Liahona property was fenced during August 1948, and on September 19, construction of the permanent campus began with making concrete blocks. Two months earlier, the first shipment of building materials, cement and lumber, arrived from America in Nuku‘alofa. With these materials on hand, there was a need for more help to build Liahona. The call went out for trained carpenters to assist, and answering the call were Iohani, Karl, and Walter Wolfgramm and Simote Fusitu‘a from Vava‘u. Each branch on Tongatapu was asked to send a group of men to volunteer to work at Liahona for a week at a time. Their branch was also to furnish their food. On December 2 President Dunn showed the plans to Prince Tungī and Premier Ata, who were surprised at the size of the building and the Church’s willingness to spend so much money on the project. The government granted landing permits for expatriate building supervisor missionaries as long as they didn’t proselytize. Church architect Edward O. Anderson came to work on the plans for the school, and he turned the first sod at a groundbreaking ceremony on November 5. The mission history reported on March 31, 1949, that the volunteers were working hard—making forms, pouring cement, making blocks, and that they had plenty of food. The plantation would donate one beef a week to supplement the food the branches brought. Bricklaying commenced on May 6, 1949, under the direction of Elder Reuben Flynn, who had come to help supervise construction. Elder Matthew Cowley came and laid the cornerstone on August 29, assisted by Elder Flynn and Mosese Muti. By September 1949, President Dunn had the schoolboys at Liahona making 1,200 blocks a day after classes.

Constructing the school with concrete blocks was a first for Tonga, along with other construction methods. Pacific shipping was slow getting reestablished after the war. Much of the building materials and equipment required for the construction of Liahona were not available in Tonga, so when ships arrived from America, most of the cargo was destined for Liahona and was off-loaded by the members and taken out to the school. The import duty paid on all this building material coming in became a large part of the government’s revenue for many years.[40] Thomas P. Wilding, a former missionary who was called back as the head carpenter on the project on May 7, 1949, related: “As President Dunn was in the government office paying duty, one of the merchants of Nuku‘alofa asked him, ‘How is it that when you have a ship load of material come in it stops raining and when I have one it rains continually?’ President Dunn said, ‘You don’t belong to the right church.’”[41]

Brother and Sister Huntsman with Like, and Harry Percival and their daughter Mele Tupou. Evon Huntsman collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Brother and Sister Huntsman with Like, and Harry Percival and their daughter Mele Tupou. Evon Huntsman collection courtesy of Lorraine Morton Ashton.

Preparations for constructing the school moved forward. Sand and gravel were brought in from other parts of the island to be used in the new cement block plant. Yet it did take some time to train the volunteers to make concrete blocks properly. The various branches took turns sending men to help. Some men even came from Vava‘u and Ha‘apai to volunteer for a month at a time. President Dunn called a new mission presidency with Elder Reuben Flynn, the block plant supervisor, as first counselor and Tevita Folau Mahu‘inga, a police inspector, as second counselor.

Each time Elder Cowley visited, he tried to get the quota of missionaries increased, but the government continued to insist that the Church be limited to three foreign missionaries. However, the mission history indicates the Church did get permission in 1949 to bring in six professional teaching missionaries destined for Liahona who wouldn’t count against the proselytizing missionary quota. The government’s restrictions on the number of foreign missionaries was really a blessing because it caused the Tongan members to continue taking responsibility for the leadership of the branches, districts, and auxiliaries in the mission. The members responded with faith and perseverance. This experience created strong leaders and testimonies.

In the first week of May 1949 the first Tongan couple traveled to the United States to be sealed in the temple—Brother and Sister Harry Percival Vete, who had been encouraged by Elder Cowley to prepare to go to the temple. Brother Vete was a lawyer and a member of Parliament who had joined the Church in 1926. They, with their daughter, were sealed in the Idaho Falls Temple. While in America, they attended the temple thirty-eight times and spoke in thirty wards in Utah and Idaho. Their testimony was that they were of the house of Israel through the explorer Hagoth mentioned in the Book of Mormon.[42] They were the first of only four Tongan families to have the privilege to go through the temple before the New Zealand Temple opened in 1958.

Elder Cowley returned on September 1949 in his assignment of supervising the missions in the Pacific. He visited again with Prince Tungī at that time. British Consul James Edward Windrum told Elder Cowley that he thought the Church should be able to have as many missionaries in Tonga as they wanted, but he had limited influence with the government. At a conference in Ha‘apai, Elder Cowley was able to answer questions from Siake Lolohea, who had befriended the Church when it returned to Ha‘apai in 1917. By the end of 1949, there were 2,820 members in Tonga and thirty-seven missionaries serving full-time, many of them as couples lending support to struggling branches. President Dunn’s summary report for 1949 described the work:

During the year 1949 we have put most of our efforts on the erection of the Liahona College. . . . The saints have supported the building program very well. Each branch of the two Tongatapu districts have taken their turn working for a week at a time. The men from Vava‘u and Ha‘apai and Niua Toputapu have come and stayed a month or more at a time. Twelve or more men have worked and stayed here at Liahona continuously. The school boys have worked a week at a time for each class and they have provided the food for the men who have stayed continuously and for those from Vava‘u and Ha‘apai. . . . All of the mission, district, and branch offices are completely organized and the missionary work is progressing. The native brethren and sisters are carrying the load of the missionary work.[43]

The war and the lack of expatriate missionaries had not slowed the growth and development of the Church. The Church in Tonga was on a firm foundation and prepared to blossom.

Notes

[1] Ermel Morton, Brief History of the Tongan Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Golden Jubilee (Suva: Fiji Times, 1968), 38.

[2] Harvey L. Taylor, “The Story of LDS Church Schools,” typescript, 2 vols. (n.p., 1971), 1:124, Perry Special Collections.

[3] MHHR, by date.

[4] Morton, Brief History of the Tongan Mission, 39.

[5] David F. Boone, “The Worldwide Evacuation of Latter-day Saint Missionaries at the Beginning of World War II” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1981), 209–11.

[6] R. Lanier Britsch, Unto the Islands of the Sea: A History of the Latter-day Saints in the Pacific (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1986), 459.

[7] Britsch, Unto the Islands of the Sea, 459.

[8] Eric B. Shumway, Tongan Saints: Legacy of Faith (Laie, HI: Institute for Polynesian Studies, 1991), 109–10, also Mormon Pacific Historical Society, Proceedings (Laie, HI: Institute for Polynesian Studies, 1985), 24–25. At the 1948 mission conference on Vava‘u, he debuted the famous Joseph Smith lakalaka he had composed and choreographed that was performed in the Polynesian Cultural Center night show for many years.

[9] Tisina Wolfgramm Gerber, comp., Iohani Wolfgramm: Man of Faith and Vision, 1911–1997 (n.p., 2000), 87.

[10] MHHR, by date.

[11] Taylor, “Story of LDS Church Schools,” 125.

[12] Sione N. Fiefia, “Americans in Tonga” (unpublished paper, fall 1965, LR 9197 28, CHL), states that the American military in Tonga during World War II brought a sense of security to Tonga and were usually generous and friendly. The economy boomed with American dollars. Many Tongans were taught some engineering, carpentry, electrical, and business skills. But they also brought home-brew alcohol, smoking, and gambling skills and taught the young to defy traditional Tongan mores. Regarding the American missionaries and teachers in Tonga in 1965, Fiefia said, “As Americans they are liked, but as Mormons they are hated.”

[13] Gerber, Iohani Wolfgramm, 89–91, and Shumway, Tongan Saints, 87–89.

[14] Paula F. Muti and Sisi K. Muti, Mosese L. Muti: A Man of Service, 1911–1993 (Bountiful, UT: self-published, 2016), 222.

[15] Semisi Nukumovaha‘i Tonga, interview by R. Lanier Britsch, 1974, 4, OH 323, CHL.

[16] Tonga, interview, 4.

[17] Emile Dunn, “Church Grows on a Tongan Island,” Church News, April 28, 1945, 9.

[18] Shumway, Tongan Saints, 124–27.

[19] Delworth Keith Young, “Liahona High School: Its Prologue and Development to 1965” (master’s thesis, Utah State University, 1967), 26.

[20] MHHR, July 18, 1947.

[21] Huntsman, “My Story Lest I Forget.”

[22] “President Dunn Returns from Tongan Mission,” Church News, August 3, 1946, 8.

[23] MHHR, August 27, 1946.

[24] MHHR, July 11, 1946, and Evon Huntsman journals, CHL.

[25] R. Lanier Britsch, “The Expansion of Mormonism in the South Pacific,” Dialogue 13, no. 1 (1980): 56.

[26] Evon Wesley Huntsman, “My Story Lest I Forget,” http://

[27] Huntsman, “My Story Lest I Forget.”

[28] Huntsman family histories, see also “Liahona College Opposition Melts to Permit School,” Church News, September 21, 1963, 16, 30–32.

[29] Huntsman, “My Story Lest I Forget.”

[30] Morton, Brief History of the Tonga Mission, 44.

[31] Huntsman family histories, CHL.

[32] Morton, Brief History of the Tonga Mission, 45–46.

[33] MHHR, June 24, 1947.

[34] Britsch, Unto the Islands of the Sea, 479.

[35] Huntsman, “My Story Lest I Forget.”

[36] Huntsman, “My Story Lest I Forget.” Other sources suggest the name was chosen by written ballot. See Martha Huntsman Journal, 1946–1948, August 7, 1947, MS 16995, CHL.

[37] Emile C. Dunn, interview by R. Lanier Britsch (typescript, 1978), 37, OH 499, CHL.

[38] Taylor, “Story of LDS Church Schools,” 127.

[39] Young, “Liahona High School,” 40.

[40] Charles Woodworth, in Houston Chronicle, May 20, 1973. Newspaper clipping in Charles Woodworth, Papers 1948–2009, MS 30024, CHL.

[41] History of Thomas P. Wilding, 1988, 46, typescript in possession of the authors.

[42] Gordon B. Hinckley, “Tongan Convert Brings Records of His People to Depository in Zion,” Church News, May 8, 1949, 10.

[43] MHHR, December 31, 1949.