Appendix A

Accounts of the 1961 Tonga Hurricane

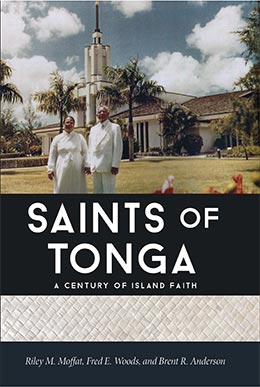

Riley M. Moffat, Fred E. Woods, and Brent R. Anderson, "Appendix A," in Saints of Tonga (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 383–416.

Account of President M. Vernon Coombs and Lavera Coombs[1]

We went up to Ha‘apai to hold district conference. . . . We had warning about the hurricane. . . . The Tongan Broadcasting Commission was then just experimenting, and we picked up the information that evening that there was a hurricane in the making up near Niuatoputapu. A Pan-American airplane on its way to Fiji from Samoa had spotted it and had sent the information in and said that it was, at that time, near Niuatoputapu and was headed for Vava‘u at about ten to twenty miles an hour. This was Wednesday the fifteenth, but we hadn’t felt it yet in Ha‘apai.

I had an experience in February 1926 of going through a hurricane on the little sailboat called the Makamaile. . . for three days and three nights, in that little 50-mile stretch between Ha’ano and Vava’u. . . . Three days and three nights on it in the hurricane! I daren’t tell you how big the waves were because you wouldn’t believe me. . . .

[But in 1961] we’d had the calm, sultry weather throughout our stay in Fiji and Tonga for two to three weeks before the hurricane came. That Wednesday we had been warned about it and we were expecting to leave on the next Hifofua. We had held district conference in Ha‘apai and had expected the Hifofua to come that Wednesday and pick us up to bring us back to Nuku‘alofa. The Hifofua came all right, and we (Manase Nau, Sione P., Sister Coombs, and myself) packed our grips and took them down to the wharf to have them taken out to the Hifofua. We wondered why it was such a long time getting started. We were told there was a special message for the captain. In the meantime, the wind was picking up a little bit, but you’d never think a hurricane was coming, though we heard of one up north. The captain sent word that nobody was coming aboard. We thought he was just playing it safe and that he’d probably go to some of the outside islands and find some safe anchorage and ride it out during the storm. We returned to the mission home, or elders’ home.

That night—at about three o’clock in the morning—the hurricane hit. Until then, it had been so hot and sultry for days that Elders Cottle and Paula Tonga had taken their beds out of their sleeping apartments and made their beds out on the veranda so they could enjoy what little breeze there was. [The] hurricane hit in the morning with a blast of rain. . . . Now that rain came from the southeast and wasn’t too much, but the wind kept increasing, stronger and stronger. Breadfruit trees went down, and then some of the coconut trees started going over. Some of the mango trees started going over, and some of the more poorly built lumber houses started going over. Roofs were lifted and tin was flying in the air. The natives of all denominations were so frightened (regardless of what church they belonged to—their houses were so poorly built) that many of the people in our end of the village at Pangai sought refuge in the protection of our chapel there. And there we sat it out. . . .

The next afternoon, the winds veered and came out from the southwest and hit us from the west. This was on Friday morning. Then was when the real damage was done. Buildings that had stood the test until that time just went!

Most of the older buildings, the lumber houses, went. And the old tin roofs . . . away they went, flying all over. And by the way, you ought to really see the house in which Her Majesty’s harbormaster used to live. That was just a pile of tin when the hurricane finished. Then, as soon as the hurricane was over, the natives went back to their homes. That second day, there was very little rain. Instead of that, the wind had picked up a lot of spray from the churned-up ocean to the west of us and brought it inland. That spray had an effect as if you had gone over all the green vegetation with some kind of material meant to kill vegetation, or like some parts of America would look after an unexpected early frost. It was brown and seared. Coconut trees were down everywhere. I mentioned before that breadfruit trees, other fruit trees, and the yams were completely destroyed, and so were the sweet potatoes. Bananas were completely blown over. In very few months, their food supply will be exhausted. Not only that, but because the coconut trees were ripped of most of their fronds, they’ll drop their young nuts before they mature, and the natives won’t have a money crop with which to buy certain necessities such as sugar, soap, flour—things like that which they get only from the stores.

I doubt if there will be any copra crop for another four or five years. That’s what the natives tell me. They’ll have food next year, such as bananas, yams, and sweet potatoes, but where will they get the money to buy other necessities such as clothing? They are going to have to have some relief from somewhere!

Now, that’s Ha‘apai alone. Later on, when Sister Coombs and I came back to Nuku‘alofa, we stopped at Ha‘afeva, and it was our opinion that the damage there was not nearly as extensive as that which was sustained in Lifuka [in Ha‘apai]. As we came a little further south to Nomuka, there seemed to be very little damage there. In fact, there were only three houses reported down. The vegetation looked green. We later on learned that the real center of the hurricane was in Vava‘u, and there’s where they suffered some real damage.

Our home and headquarters at Ha‘apai suffered no damage at all. But all other meetinghouses, with the exception of the Catholic Church, were down—everything, including the two comparatively new constructed Wesleyan churches. They felt terrible about it. Now that was in Ha‘apai.

When I had heard that Vava‘u had been struck very severely, I sent a cable to Brother Helquist in Nuku’alofa, requesting him to contact Fakatou Vaitai and ask him to go to Ha‘apai and Vava‘u and make a survey . . . to see what is necessary for repairs. He went up with Manase Nau and Sione Pi. They were right there to see what had happened to Vava‘u. They said, “Why, you folks thought we had it terrible in Ha‘apai; it’s nothing to what we had in Vava‘u.” The coconut trees in Vava‘u were not only blown over, but many of them were actually decapitated, . . . their heads twisted right off. It was like a harvester had gone through, set up fifty feet high, and just cut the heads clean off. All that is left is just simply telephone posts stuck up here and there all over the place.

And then, they had the same kind of damaging ocean spray as we had down in Ha’apai. In Vava‘u, our beautiful new chapels at ‘Otea, Tu‘anuku, Leimatu‘a, and Ha‘alaufuli all lost their roofs: the chapels and some of the amusement halls. The new and old chapels at Neiafu were quite unharmed. But, as at Ha‘apai, practically all the old wooden chapels—meetinghouses—of all denominations went down. One of our good Saints, Sepiuta Motu‘a, had the misfortune that in trying to escape from her own house that was being blown down, she happened to get close to a Wesleyan church as it went down, and she was crushed to death. That was a wooden church in Ha‘alaufuli.

There are a few interesting sidelights. During the force of this storm, I have been informed, the native doctors and nurses in the hospital in Neiafu completely deserted their patients . . . to their own devices. The only man [who remained] on the job was a dental assistant, a member of our Church by the name of Vili Pele [Folau]. He was here and there and everywhere, conducting the ill to places of refuge and carrying those who had to be taken [to a safer place]. He had no regard for his own life but was right out there in the midst of it, helping the other people who were helpless.

Mosese Langi at Tu‘anuku, completely disregarding his own safety, was here and there and all over the village, leading anybody of any denomination to the comparative safety underneath the concrete porch of our chapel there. Although it was roofless, being on the hillside, this porch afforded some protection from the effects of the storm. He brought in people of all denominations and offered them shelter.

We had the same thing happen at Leimatu‘a. This is where the man tried to dispossess us and made such a fuss over our lease. He was the first one to seek shelter there. . . . I have been told that over four hundred people from Leimatu‘a sought shelter and the protection afforded by the concrete porch.

The same thing was true at Ha‘alaufuli. Our good priesthood members, such as Peter Pauni and others, were busy bringing people in for protection. They even went out and offered shelter to the Wesleyan missionary who hates us . . . who, a few days before, had forbade the children of his missionaries to play with our Mormon kids. If they didn’t quit playing with the Mormon children, he would dismiss from service their fathers, who were his missionaries. He was just that hateful. Yet when this came up he wouldn’t accept our protection himself, but he did permit his wife and children to be led to the comparative safety of our chapel there in Ha‘alaufuli. Then, when his own house blew down, he very grudgingly permitted himself to be led into the protection of our place. When the storm was over, he and his family were the first ones to leave, and they have never, even till this day, offered one word of thanks. . . .

In ‘Otea we found the same thing. The action of our young brethren was a sermon in real Christianity to people who observed us. Not only that, but a number of people went up on the Hifofua, including Prince Tungī, and when they saw our places, they said, “You Mormons surely know how to do it. Although you lost your roofs, the bodies of your houses stand as a testimony to your know-how.” So we felt a bit good about that compliment. . . .

That boy [Eric Shumway] was here and there and everywhere bringing anybody. He had no regard for his own life, and even today, a week or so after the storm, he’s limping around with a big gash in his leg that he got during the storm.

Well, if he didn’t save lives, he surely made them a lot more comfortable. He paid no attention in regards to what church or denomination they belonged to—he was there helping them all. As soon as the storm was over, the government was too slow in clearing the roads, so he and Elder Murdock went out and took their own axes and actually cleared the roads so he could get to the distant villages. They wanted to see how the Saints were getting along.

Fakatou [Vaitai] and ten specially called men from Tonga [Tongatapu] have gone up there on a special call to see if they can repair those buildings that have been damaged and save the parts that haven’t already been damaged. They are up there working without pay. Our good Saints here sent up ahead of them talo and other kinds of food for them to eat to sustain them. They’ll stay there for what time is necessary to do what repairs are necessary. . . . The people in Ha‘apai and Vava‘u are not down in the mouth; they are very cheerful and they’re going right at it.

Sione Makaafi’s wife was standing by the chapel [at Fahefa on Tongatapu]. Brother Lindsay said, “Is Sione here?” “No, he’s in town,” [his wife replied]. “Do you know when he’s coming back?” “No, I don’t.” “Will he be at priesthood meeting?” “No, I don’t think that he will.” “We want him to go as a missionary to Vava‘u.” “When?” “Tomorrow.” “Ok, he’ll go.” That was his wife speaking. She is expecting a baby anytime, but that didn’t matter. She also has several little ones running around. . . .

The little lumber chapel up in Faleloa was also destroyed, but the people are going right after it with their own tools to restore the building the best they can with what materials they have. . . .

I have been told that the winds in Ha‘apai attained a velocity of about ninety or a hundred miles an hour at the center. And I have also been informed that the velocity of the winds in Vava‘u was up to 135 miles an hour. Now, if that’s true, that was a real terrific hurricane.

According to what the Saints say, Elder George Albert Smith said, when he visited them many years ago, with a promise that if they would endeavor to be faithful—stressing tithing—the Lord would protect this island from hurricanes. . . . Someone has remarked that tithing has jumped a hundred percent since the hurricane!

About this native temperament, bless their hearts, they believe what you say; they believe what they pray for. They aren’t like we “Europeans” with all of our philosophies. We seem to think we are their superiors and know so much more than they. These natives actually believe it! When they ask a blessing from the Lord, why, they’re going to get it! If our people at home were just that simple, I think maybe we might be better off. But, too often, we know more than the Lord and want to tell him how to do it. I’ve noticed so often that these people are so fundamental, and they take the Lord at his word. They also take the missionaries’ word, so we have to be very careful in the use of our priesthood and in making promises. These natives remember those things. They expect them to happen. . . .

I’ve been informed that the Wesleyans had thirty-eight churches in Vava‘u and that only two are left standing. Even the big Catholic church made from concrete, the roof is removed from it and two-thirds of its walls are down. The Catholic church in Ha‘apai was not hurt. All the other churches, except ours and the Catholics’, went down in Ha‘apai. The Catholic church there is made from native lime cement. It is just sad to see that devastation! It will take years for these other churches to replace their buildings. They haven’t the money, nor have they the organization that we have. They won’t get the help that our people have.

As soon as the houses started to go over, the people just left what was in them and sought their own safety. Most of the old native houses were blown down in Ha‘apai, and surely in Vava‘u. In Leimatu‘a, Brother Fakatou says there wasn’t a house left standing. Not a house . . . except the walls of our own. . . . There are four of our buildings there that have suffered material damage.

Brother Fakatou remarked upon his return from Vava‘u last Saturday that he was talking to one of the brethren who had been at Nga‘unoho; they went to see the people. He said it looked like a giant had taken his hand and scooped the village right off the land. . . .

Account of Elder Eric B. Shumway[2]

On Wednesday evening, March 15, we were gathered together at the missionaries’ house in Neiafu with some of the Tongan missionaries. I expected to sail to Nuku’alofa on Thursday. Elder David Murdock had arrived to replace me. They wanted to come that evening so we could stay together and talk and have a little get-together. There were eight at the house that night. But, there are twenty-one who were under my supervision in Vava‘u. Some are young, unmarried; some had left their families and were called to Vava‘u; there are some who had their wives with them.

While we were talking to these missionaries, we heard a “caller.” This is a custom that whenever a noble or chief wants something known, he sends out one of his callers. The caller goes throughout the town to let the people know what will happen that day or when something will be in the future.

This caller said the hurricane would hit Vava‘u about five o’clock Thursday morning. That was the first time we knew that the hurricane would hit there. The missionaries did not seem too concerned about it because the warning of hurricanes come in March every year. They have been just little winds, not too much to “shake a stick at.” This is why the missionaries wanted to stay with me that night. These were missionaries who had families, but they weren’t worried about them.

We stayed up till about two o’clock in the morning, as we wanted to get everything . . . that is, I wanted to let them know something of myself. We had a great missionary team in Vava‘u. These Tongan elders have a great spirit among them. They have great power with them. There is no equal—for years and years the gospel hasn’t been preached like that in Vava‘u. That’s why I love them so much and why I had called them together that night.

At two o’clock in the morning the wind had begun blowing. I went to bed and didn’t awake till five, when the wind was blowing very strongly, and two of the missionaries came into the house. I was surprised to see them, for I thought they were sleeping. They told me that they knew it was a big hurricane and that they knew it was not something to disregard. They wanted to get back to their families and asked if I could take them in the car before the big part of it hit. I thought about it because I love these fellows and I knew they lived a long way [away]. When I opened the door to look out, I saw the road; I saw the trees already coming down. The road was completely blocked and nothing could get through. I don’t think I could have gotten out of the gate. I told the missionaries it might be safer if they would walk, even though it was about five miles to their little island, . . . and they could probably reach their families before the biggest part of the storm hit. They were going to Tu‘anekivale and Koloa. Koloa is a little island. You have to walk across the reef. Tu‘anekivale is the farthest town on the main island to the east.

Before they got out of sight, the wind really came down. That is when I knew we were really in for it. We were going to have a great hurricane—not just one that they have every year, but one which would make history. I knew it, felt it in my bones. I called all the people that lived near there. The girl that helps the missionaries, ‘Ofa Toli, lives in a little house—an old tin house—next to the missionaries’ house. Before it was converted into a house to live in, it was a little bakery. It was a very old house. Much of the Church’s material is stored there . . . things left over from the building program. I called to ‘Ofa and Vili Pele, a dental apprentice who stayed in our compound. I thought Vili was there, but he wasn’t. He was up to the hospital. I told everyone who lived there to go into the chapel. I didn’t want anyone to stay in the old house, lest it fall down and someone be killed. I knew that two of the houses on the church lot would probably be taken with the wind. They just couldn’t possibly stand! The house that ‘Ofa lived in is quite a big house but is a rotten old thing. They must have held classes there years ago when the school was there. The old school or church house is a rickety old thing and I knew it must go, too.

About eight o’clock, or nearer to nine, everything in the town began going up—literally going up . . . straight up in the air. I stayed outside on the west side of the church house—the wind was coming from the east—so I could see everything that went on in town. I looked to see a chance to run out and bring someone into the safety of the chapel. From where I stood, I could see all the houses go down and being torn up and the big trees torn up by their roots and thrown into the air. I almost had a feeling of awe that I could witness such a power of nature . . . how little and tiny man seemed to nature. While I was standing in awe, it suddenly dawned on me that there were many people who were really hard up! They were being killed or crushed to death. I called about four of my missionaries, including Elder Murdock. We went to all the houses that I could see from where I was that had already started to go down. A lot of the sides of houses were down and roofs were gone. I knew that there were people there, so I ran with these four missionaries to bring these people into the chapel. I guess I ran for about a block.

One house that I entered, the one side of the house was already down and the roof already ripped off. Rain and sticks and limbs and tin and nails and everything was coming with the wind into the house. There was one woman sitting in a chair right in the middle of the house holding her little baby, which had been born but a week before. The woman was completely in hysterics. I had met her before, but she didn’t even know who I was. There were two women there, the one with the baby and another standing. They were both in hysterics. They couldn’t think straight. I told the woman who was holding the baby to let me have it to take to the chapel so it could live and escape from the hurricane. She didn’t want to give me the baby. She was completely out of her mind. I tried to talk to her in a soft voice so she would depend upon me. I knew that any minute the house would be taken. She wouldn’t listen to me, so I grabbed the baby and ran out the door with it and called for one of the missionaries to bring the woman after me. The woman was willing to come because she knew I had the baby and would follow after me. This was a testimony to me that she’d already given up and she’d thoroughly expected to die with her baby. But the fact that I grabbed the baby from her and went out of the house, she decided to get out of the house—to follow the baby, not because she wanted to live, but to follow the baby.

When we got to the chapel, though, the baby was very wet; we got dry clothes for it. The woman and the baby live to this day. The woman is all right and she might be baptized. She was one woman to whom we had tracted and given, I guess, three lessons before. That was the way it was with the baby and people rescuing expeditions. Of course, there were a lot of acts of heroism, but the missionaries did it. I guess I couldn’t count them all if I tried.

At ten o’clock, I estimated the wind to be about a hundred and fifty miles an hour! I could almost bear testimony to anybody that it wasn’t less than a hundred and fifty miles an hour at that point, ten o’clock Thursday morning. At that time I could see the Wesleyan tabernacle, which is about a block from our chapel, being completely torn to bits by invisible hands: the wind. Before the whole roof was even torn off, the whole building collapsed, crushing one man to death in the building. There isn’t one building in Liahona here which is equal in size to that huge tabernacle. It was about 40 feet high and about 150 feet long. It was completely demolished; parts were taken down the hill to the sea.

The Tongan Church tabernacle, which is about the same size and on about the same order as our old chapel at the church lot in Neiafu, about twenty feet high and a hundred feet long, was completely demolished, too.

The hospital roof, I could see from where I was, was taken off. All the beams, valleys, and timbers of the roof were taken off or had fallen down inside the building. I knew that if the patients hadn’t been taken out by that time that they would have been crushed to death. That’s why I was so worried. I had already known, almost, that many people had been lost in the storm. I looked down the hill and across the way to the Catholic cathedral, which is a huge rock building. The roof had already been taken to the sea and the high rock walls were crumbling down like a little baby hits his blocks after he had built them into a little house.

After we had all the people into the church from houses that were near, I thought I would run down to the Catholic place and see about the Catholic father and the nuns. Our members were already safe in the chapel. My companion, Palu Ton went to see how the father and nuns were and the other white people who had been my friends in Vava‘u. When we got there, we could see that the father’s house had already been taken somewhere. I don’t know where. There were only cement poles sticking up in the ground where his house stood. The chapel had been torn to bits, but one building which was still standing was their schoolhouse. I went there immediately. There were about fifty people in the basement of the schoolhouse. The Catholic father and nuns were there and said they were safe, so we returned.

Before we returned, one boy told us that the father was completely out of his mind and that at the beginning of the storm, he had stayed right in the middle of the cathedral. He fully expected it to stand. It was a building that was just built not very long ago and it was a huge rock building. It had a high tower that had withstood many winds. So, the Catholic father thought it would withstand this wind. He stood right in the middle of his cathedral. When the roof started to go, and his own house went, he realized that it was all gone and that all he’d dreamed for, as far as cathedrals and beautiful houses and schools go, was taken up with the wind. The people there told me that he’d lost his mind while standing in the cathedral. He wouldn’t go out. Even though the walls were crumbling down and ceiling timbers were crumbling in on him and it looked as if the building would collapse, he stood there without any regard as to what was going on.

The natives called in to him to come out, but he wouldn’t do it. He told them that he would rather die than witness the destruction of the things which had taken so long for him to build. Three Tongan boys entered the house immediately because they knew that within seconds, the whole building would be crumbling to the ground. They carried the Catholic father out against his will, carrying him to the basement of the schoolhouse. That was how the Catholic church went up (or down).

It’s a quarter of a mile from our church to the Catholic church (actually almost a mile). The wind was coming from the east and pushed me there. Coming back was what was hard. I had to walk at almost a 45-degree angle to stand up in the wind. Twice I fell down, being bowled over by the wind. I went with three other missionaries. On the way there and back, I witnessed a lot of destruction by the wind. It was quite a thing dodging the great trees which were being hurled around like paper.

One house I saw was just taken straight up in the air without being demolished or the roof being taken off. At about fifty feet, it was like someone had thrown a grenade into it. It exploded like that. Of course, it was the wind that exploded it in the middle of the air, and it went in every direction. Some went into the sea, and other parts of the house went in different directions.

The place where Lairds (former LDS schoolmaster) used to live is completely demolished, torn apart. Parts of it are in the sea, and other parts are still on the lot.

A lot of the government properties had good foundations, and the roofs were just taken off. The Burns Philp store and the Morris Hedstrom store escaped a lot of damage right on the store proper. Their back store, their fuel houses, and lumber buildings were taken into the sea.

Personally, I think it was a blessing of the Lord that these two stores weren’t taken. The people in Vava‘u, for the few days after the storm, got a lot of their supplies from these two stores. If the roofs had been taken off or the houses fallen, the wind would have taken everything into the sea. It wouldn’t have left anything. That was the characteristic of the terrific wind that fell. When a house went down, it wouldn’t stay there, but the wind scattered everything in the house: the beds, falas (mats), the mirrors, chairs, and chests of drawers were taken to the four winds. They just couldn’t stay there. Because the two stores didn’t collapse completely, the people were able to get a lot of supplies after the storm. . . .

The storm hit about five in the morning, was really strong about eight o’clock, and was terrific about ten. It stayed up until Friday morning. I guess we had about thirty-six hours of wind over a hundred miles an hour. For about five hours, I’d say the wind was up to a hundred and fifty miles an hour. But during that long time all of the houses on the church lot in Neiafu escaped damage, which is a miracle in itself. I thank the Lord that he preserved us and those houses. The little tin shack, used before as a classroom, had only three pieces of tin taken from it, and that was all. Every part of that house, if we talk about science, should have gone. I think we would all agree before that if a hundred-and-fifty-mile-an-hour wind would hit that place, that it would be the first house to go in Neiafu. The second house to go would be the old chapel. But, these two houses, through the preservation of the Lord, stood through that mighty hurricane without any bad damage. It was very easy to fix up the house from which the tin had been taken. Only one window, I think, was cracked in the old chapel. The little veranda that sticks out over the front porch on the old chapel has no bracing, has nothing to make it strong. The carpenter seemingly stuck it against the wall, and yet it stayed on perfectly, didn’t even twist. One huge two-by-six was torn off of one of the houses on the hill, and it came and hit the roof on our big chapel and made a four-inch-long hole in the roof. That was all the damage to our large brick chapel. . . .

The roof of the theater was taken off, but the walls stood. The lumber and some of the chairs were picked up from inside and taken right through the roof. That’s one thing that is hard to understand. The wind took off part of the roof, came down and picked up the chairs, etc., and took them out the same hole. But, the big house didn’t fall. If it did, it was sure to fall on our chapel and cause serious damage. It is just east of our chapel.

Most of the houses which stand near the chapel fell. The huge mango tree (a mango tree is comparable to the oak tree in America for strength) that stood across the street from our chapel was literally in ribbons. Big limbs, a foot in diameter, were torn off like matchsticks and taken to the sea or stopped the road, . . . making it hard to get out in the car. Right now, I don’t think that tree has any part sticking up ten feet in the air. Just the big trunk stands there right now. None of the trees in Vava‘u have any leaves now, or anything green on them: just stubs sticking up all over. . . .

Neiafu is the main city of Vava‘u. I estimated that the least damage in Vava’u was done in Neiafu. I think about 60 percent of all the houses in Neiafu were completely destroyed, or maybe more. Here is one thing for which the Church received much credit. Vili Pele, an elder of the Church, was one of the youngest boys to receive the Melchizedek Priesthood in Tonga. He received it when he was nineteen, or close to that age. He is one of the dentists’ assistants in the hospital. When the storm hit, he was right on the job. About ten o’clock, when the worst part of the storm came, why, the roof started to go. They had a lot of patients in the upper story of the hospital that could have been crushed to death when the beams of the house fell. . . . The tree limbs, tin, and big boards were coming in—right down on the patients.

This Vili Pele entered immediately into all the rooms that were in the upper story and moved the patients into the basement of the hospital. That is a great task for ten people! But Vili Pele did it with another person. I’m not sure who that other person was. I visited the hospital several times after the storm and this was all the patients could talk about—how brave this Mormon fellow was in saving all the patients in the upper story from being crushed to death.

Vili Pele is a good fellow, a great speaker, and a good Mormon, but since he’s been little he’s been sickly. His body is very weak and he is subject to sick spells every year. Even though he was sick when the storm hit, he was given enough strength to do the work of about ten people in moving the patients from the upper story to the basement. There wasn’t one patient that was injured. Some persons died because of results of their exposure to the rain during that trial, but there were no patients killed or crushed to death during the hurricane.

As I said before, about 60 percent of all the houses in Neiafu have been destroyed. And about 80 percent of them have been damaged so bad that it will be almost like building a new house to repair them. About 15 percent of the houses in Neiafu didn’t receive much damage. As for us, there was no damage on our church lot in Neiafu. Two huge coconut trees fell within inches of our missionary apartment, where I was during the storm—much of the time writing down what I saw. But none hit the house. I was in the house when a huge coconut tree fell between the fence and the house and came within inches of crushing the west wall. That was about two o’clock in the afternoon. . . .

I was there [in Neiafu] Thursday afternoon and night, also Friday morning. Friday afternoon, I spent the time cleaning up with Elder Murdock and other missionaries. That afternoon, the winds were down to sixty miles per hour, and the word had come that the hurricane was over and that it wouldn’t come back again. I thought that the best thing for us to do would be to clean up the church house, so we could use the rest of our time going to the missionaries in the outlying villages. Friday afternoon we spent most of our time cleaning up the huge trees that had fallen by cutting them and stacking them in piles. There were about four huge piles of trash that fell right in the church lot. Saturday morning I got up and got my ax and my Tongan knife and with four other elders, including Elder Murdock, went out, cutting fallen trees in the roads and clearing them so we could get to the outlying villages. My missionaries and their families were in the outlying villages and we wanted to get to them. . . .

There were some villages that we were the first ones to. I think we were the first to Tefisi and Koloa and Tu‘anekivale. We cleared the road from Leimatu‘a to Tefisi, which is about four miles.

We went on horseback to Ha‘alaufuli, Tu‘anekivale, and Koloa to see the missionaries. The wooden church house in Tefisi was completely demolished. There was absolutely nothing left standing. The floor was the only thing that could be seen—also some parts of the building that were just scattered over the yard. The missionary, Kepu Fungavaka, his wife, and his five little children escaped the great winds in a little tiny store, which I’m convinced the Lord kept standing during the storm. This little store stood up on a high part of the island where the wind got to it on both sides. But the house wasn’t touched, and the missionary and his wife and children were saved from the hurricane in Tefisi.

The missionary in Feletoa took his wife to Leimatu‘a to our big brick chapel. They were saved there. In Leimatu‘a on Thursday night, the missionary told me that there were over four hundred people that escaped to the chapel during the winds. The chapel part of the roof was already taken off. The rain was coming in right in the chapel proper. The recreation hall was the only part of the building with a roof and the people entered the recreation hall and stayed there Thursday afternoon and Thursday night. They couldn’t sit down or lie down or sleep; they just had to stand there in that little recreation hall all the time. They talked, sang, and prayed and asked the Lord to save them.

It was the same way in Ha‘alaufuli; the people rushed to our chapel. There were about three hundred of them that night in the chapel. All the people that hated the church before, their hearts were softened right then during the storm while they were being saved away from the winds. After it was over, they returned to their houses and hated the Mormons again. That’s the way it is sometimes with people who hate the Church. They hate the Church as long as they are prosperous and then when they’re not prosperous, they ask the Church for help. When they get their help, they return back to their hating the Church again.

The chapel in Tu‘anekivale, a wooden building, was completely demolished like the one in Tefisi. It was completely taken, and many of the parts haven’t been seen since. The missionary and his wife and children and the Saints took refuge in the house of Mu‘a, who is the first counselor to the district president. His house still stands, and the Saints and many of the outsiders were saved there. Every tree on his lot, three mango trees and three other huge trees, were torn up by the roots, but the little house still stood.

The chapel in Koloa is completely demolished. When it fell it was a miracle that the wind didn’t take all the parts of the chapel to the sea. It fell and just stayed there. There was a little opening about one and a half feet high under one wall that had fallen. There the Saints, about twenty-five of them, entered and stayed. Koloa is pretty well open. Many of the Saints ran down to the seashore and escaped the winds in little caves at the [edge of the island]. When they returned after the wind, they entered the little opening under that wall that had fallen. And when I got to Koloa (which is about five miles from Ha‘alaufuli) on Sunday morning on horseback, the people were still under the wall. I entered there because one of the little boys of the missionary was cut badly. The ligament on his little foot was completely cut in two. So I entered the little place to give them some first aid. I couldn’t sit up straight in that one-and-a-half-foot space.

I really felt that it was pitiful the way that those Saints had lived in Koloa during and directly after the storm. They had great faith and were happy that they still lived, but they just couldn’t stand to see their chapel fall. Everything was taken with the wind and there was nothing immediately to eat. The children were crying and cut up. It was just a pathetic sight. I gave them quite a little talk about how the Lord sometimes chastises us to see if we’ve got the stuff in us or not, and then they felt a little better. I told the missionary that he’d better give us his little boy, and wew would take him to the hospital and get him some first aid. I knew that if he didn’t get to a good doctor and have the ligament set that his foot would be twisted when it healed. So we took the little boy back on the horse to the hospital in Neiafu.

We went to Talihau by boat on Monday and were the first ones to reach that island. Every house in Talihau was completely demolished, and all the trees in the town were flat on the ground. It was just desolate. I know just how the Nephites and the Mulikites [Mulekites] felt when they came upon Desolation in the Book of Mormon. Everything was torn down and destroyed. This is the way it was with this little town of Talihau. Everything was down, taken, or ruined. It was a miracle to me when I saw all the people trying to fix up little lean-tos where they could live. The missionary, Potiti Fungavaka, had a bad cut on his hand but that was it. He was the only one of the Church members that was hurt. I doctored his wound for him. All of the houses were down. I took them some food, as I did all of the other missionaries.

The first thing that I did after the storm was to go down to the store. I’m a good friend of the man who runs the store, Emery Murry, so I got him to give me a lot of food on credit. We were able to reach all of the missionaries and give food to them and their children.

‘Otea is absolutely ruined. There are only three houses left standing and two of these belong to members of the Church. The house of Aisake Likiliki, who is the chairman of the district genealogy, still stands. The house of Sitapa, a missionary working here in Tongatapu, is also still standing. The other house belongs to a man outside of the Church. All the people in ‘Otea took refuge in our chapel. The Wesleyan minister who hates the Church was the first one to sit right in the middle of the recreation hall with his family. When I met him after the storm he was very happy, as though he had had a change of heart towards the Church.

The Wesleyan minister in Ha‘alaufuli was very different than this, as President Coombs has said. He was very reluctant to give up his house, which was torn apart by the wind, and take refuge in the Mormon chapel. After the storm was over, he left the Mormon chapel still regretting that he had to go to our chapel and he didn’t give us any thanks or offer any word of appreciation to the Saints in Ha‘alaufuli.

But this Wesleyan minister in ‘Otea, who hated the Church also, had a change of heart. ‘Otea sits right on the ocean, and so the wind hit this chapel full force. The roof over the chapel and part of the veranda were taken, but the recreation hall roof still stayed on. The people were able to stay in the recreation hall. It was a miracle that the waves didn’t go up into the chapel. (It is only about a hundred feet away from the ocean.)

The chapel in Tu‘anuku is completely riddled. All the roof was taken off. The people in that village took refuge underneath the chapel, which is like a huge cave. They built the chapel on huge cement poles because it was on a downgrade to the sea. Under the building, by those poles, was where the people took refuge. . . . There wasn’t any place else where they could have gone. The town runs right along a huge ridge. On one side of the ridge is a lake and on the other side of the ridge is the sea. There’s not one house that stands in Tu‘anuku right now, except the chapel.

The tauhikolo, branch president, Mosese Langi, was very courageous and showed a lot of ability to lead in removing all the people from their houses to the church house. The people, as I said before, lost their minds completely and were just thoroughly satisfying themselves that they were going to die. The priesthood members entered all the houses and literally tore the people from their houses to the chapel, because their houses were falling on them. That’s what I call pitiful: the people just losing their minds and staying in their houses, which were falling. The priesthood members entered the houses and grabbed the people and took them outside and then into the chapel, and they were all saved there.

As I said before, there’s not one house that stands in Tu‘anuku right now. I would say that 80–90 percent of all of the houses in all of the villages, except Neiafu, have fallen or are destroyed. There’s not 10 percent of the houses in the outlying villages that still stand.

The house of Dr. Mathesen is damaged very badly. I think that little village was protected a lot. I saw that many of the houses still stood there. Maybe 70 percent of the houses fell in that village. Dr. Mathesen’s house was very riddled. The roof was taken off, and four rooms were torn away from the rest of the house. The little house that stands on the little round island was hit by two huge coconut trees. The roof was crushed, but the little house was held down by the trees. I really feel like I’m not making this as dramatic as it should be. A poet should have been there to see the huge tempest that fell. . . .

Maybe 75–80 percent of everything in Vava‘u has been destroyed. Maybe even more as far as the vegetation and plantations go. As to houses and coconut trees, I say about 80–85 percent of all the houses and trees are destroyed. I guess the plantations and the gardens still have a few things left in them, but I think the supply will be exhausted this month or next month. It can’t possibly last longer than two months. It will probably be two years before they get any copra. The trees that are still alive right now, which is only about 25 percent, will bear next year. It will probably be about ten years before they will have copra as a moneymaking export again. There are some people who say fifteen or twenty years. I think if they really work hard they can do it in ten years. But it won’t be less than ten years. They will have good bananas next year. After the storm, I cut off some of the bananas that had fallen, so that the shoots would grow very fast. And within three days the shoots were already showing. So next year they will have plenty of bananas. That will be the first money crop they will have.

There’s an experience that I had with the branch president. . . . That’s one of the things that I really felt when he told me of his experience. I can bear testimony to anyone who wants to have a good testimony concerning the thing that happened to Tonga Malohifo‘ou (who is the branch president in Neiafu) and his family during the storm. Tonga Malohifo‘ou is a man of great power. He’s a man of great but simple knowledge as far as the gospel is concerned. But if anyone else would see him, they would say that he was nothing special. But when we see him as a Saint, we can bear testimony that he is a man of power, of the Melchizedek Priesthood. He demonstrated his faith and power during the storm by commanding the elements to stay away from his house that his wife and family could be saved.

On Thursday morning at eight o’clock, . . . the storm hit. . . . Tonga Malohifo‘ou was my first real friend in Tonga. He and his wife, Ana, were serving as missionaries in Mu‘a, in Tongatapu, when I first came. He was the first to give me Tongan language lessons, the first to show me anything about missionary work here. That’s why I’ve grown to love him through the months, and my love is still growing! He was released as a missionary in September 1960 and returned to Vava‘u to be the branch president in Neiafu again. He had been branch president before being called on his mission. The branch was really going forward under his direction.

When the wind hit on Thursday morning, I noticed that Tonga was not at the chapel. He, as branch president, should have been the first one there to organize the confusion that was going on. He didn’t show up, morning, noon (the wind was up about a hundred and fifty miles an hour, and things were being torn up, including the huge trees, as I’ve said before, which are comparable with the big oak trees in America) he didn’t show up. I had a tremendous feeling that something was wrong with his house.

In America his little house would be considered very worn and fragile. I couldn’t do anything about it because his house is about a mile from the chapel. The farthest I had gone in the wind was about one-fourth of a mile. His house was so far away, and I couldn’t get there, as that is the direction from which the wind was coming. I had a feeling that he’d be safe, inasmuch as he is a man of the priesthood and a man of power.

That afternoon, that night, he didn’t show up at the chapel. The wind was very bad that night. Friday morning, he wasn’t there. Friday morning, about ten o’clock, the wind was still over a hundred miles an hour, but I couldn’t restrain myself from going to his house to see what it was, how he was doing, and how his family was. I had loved them so greatly since I’ve come to Tonga. I took Vili Pele, the boy who saved so many in the hospital, and we ran to Tonga’s house. Now, I don’t say I’m an athletic fellow; but I have had some experience with athletics since I was little. I’ve never had a more trying physical exertion than that of running against the wind to his house.

When we reached there, I had one of the biggest surprises of all my life, because his house still stood without any seeming damage whatsoever! The little kitchen to his house, a little shack which should have fallen over had someone breathed against it, was still standing too, right next to his house. The big Tongan Church tabernacle, right across the road, has already fallen. The big house that stood on the corner, very close to Tonga’s house, was already taken. I couldn’t even see where it was. The house on the other side of Tonga’s house was completely demolished. The huge vavae tree . . . actually four vavae trees on Tonga’s lot, were completely torn apart and in pieces . . . some torn up by the roots. But, his house still stood; and the little house in the back! Everything else on the lot was still intact.

When we reached his house, I called in to him to open the door. I took off my coat and shoes, as I was wet through trying to get there. He had to brace himself against the door to let it open enough to let us in. The wind was strong enough to take the door right off! When we entered the house, I thoroughly expected to see dead people. I don’t know why. I was just sort of afraid that there had been some harm during the storm. But when we entered the house, his little wife, Ana, cheerfully called my name and invited us to sit down and eat some of the cold yam that they had had that morning. It surprised me that they had even been able to build a fire and cook some food. Most of the people in Vava‘u had been without food Thursday morning through Friday morning. This was Friday morning, and these folks had plenty to eat.

The first thing I asked Tonga was why in the world did he disregard his position and not go to the chapel with his wife! He didn’t say anything but just pointed to the little children on the floor. There were about ten tiny children. I don’t know whose they were nor why they came, but they were there. He told me he didn’t dare “enter outside” the house as one of them might be killed or crushed to death. I told him that it would have been much better to have tried to go to the chapel than staying here and maybe being crushed to death in the house. He just smiled and didn’t say anything. His wife was lying down at that time and I knew that she’d been sick. She had been sick the day before the storm. Tonga told me that that was another reason he didn’t want to go to the chapel, because his wife was ill, and he had these little children. He said he knew if he “entered outside” of the house to try to make a break for the chapel, that trees and tin would crush or kill one of them, or at least one of them would be wounded badly. I still tried to get from him why he didn’t make a break for the chapel. About that time he started to cry, as I was asking him why he didn’t go. He said, “Shumway, I want you to come in here to this other room, and I’ll tell you why I didn’t go.”

Vili and I entered the room and he told us, “I’ve already told you why I didn’t go, I was scared to go outside. I would have to carry my wife, and if I carried my wife, I couldn’t take care of the children.” He said, “At eight o’clock, I knew I’d have to stay in the house . . . on Thursday morning. About this time the wind hadn’t really got to its peak, but I could hear the roof and feel the house shaking, just like somebody was shaking it from outside. Or it was like a huge caterpillar was hitting one side and shaking it until ready to fall. I knew that if I stayed in the house I would die, with my family, and if I went outside, I’d die. Shumway, about that time, I climbed up on this chair and I placed my hand right on the part of the roof that would go off first. I said, ‘By the power of the priesthood which I hold, and in the name of Jesus Christ, I command you to stand solidly and completely throughout this storm.’ I stopped the storm from this house, from this lot and these houses which stand on the lot.” That was his command to the elements to stay away from his house—that his sick wife and little children would be safe.

Tonga told us that after he had said these words, the house quit shaking, the roof quit rattling, the wind seemed to die down outside. But it wasn’t! But, the wind was stopped from that little house, because he commanded in the name of Jesus Christ and by the power of the priesthood.

Vili and I heard his words and heard his testimony, and we couldn’t say anything. I couldn’t think of anything else. I wished from the bottom of my heart, when I heard that testimony, that all the skeptics of the Church, the scorners, all of the “intelligent” people of the Church, could stand right in that little house and hear the testimony that I heard and receive the burning in their hearts that I received at that time. I couldn’t disbelieve it! I just absolutely couldn’t!

I could see outside through the holes of his little house, and I could also see through the window all the destruction and the desolation, the tearing up of trees and everything that had gone on outside. I knew that the Lord saved him, that the Lord answered him or obeyed his command in the name of Christ and the power of the priesthood.

There was another house that stood on that lot of an outsider, and it stood through the storm too. All the other houses that stood around were completely demolished.

Personally, I believe, that in the power of the priesthood that was in Tonga, he stopped the wind from that particular area. The wind couldn’t get at it; it saved the house of his next-door neighbor. It was very close. All the outlying houses were completely demolished and taken, even the big tabernacle, or church. But in that particular lot of Tonga’s, all the houses stood [against] the wind.

Personally, I believe the wind didn’t go there. I am not saying that the Lord made the house strong. I personally believe that the wind was just stopped; that it couldn’t reach the house! The reason that I believe that was that even the little fale peito, where they eat, which was old and worn—any kind of a breeze could blow it over—but it still stood. So I believe that the wind and the elements were stopped from that particular area.

Another thing. For about five minutes, I couldn’t speak, couldn’t say anything. Lumps were in my throat and my heart was burning. I knew that the power of the Lord was manifested. I told him, “Tonga, we’ll go. You’ve been saved by the Lord, and we know it. There’s nothing else we can do, so we will go. But in two hours I expect you to be at the church house. You’ve got to run this deal. You are the branch president here, and there are about a hundred and fifty staying in our church house. You’ve got to take care of them.”

He said, “Yes, I’ll be there in less than two hours. But I want you to give me some nails. Even though the Lord saved me, I want to tack down the roof.” I gave him about ten or fifteen nails and then went back with Vili to the church house. In less than two hours, Tonga was there with his wife and family. He told me that he had climbed upon his house and tacked down the roof. There were only seven nails on the whole roof of his house that kept that roof on! He could see the holes. But those seven nails still stood, holding the roof on. That’s why I believe the wind was absolutely stopped from his lot, his little place. Yet, the wind had reaped destruction; it could be seen every place you looked from his house. That’s one of the miracles that I can bear testimony to—to any scoffer, any scientist, or any disbeliever.

We hear a lot of stories about things like that, but we often don’t take heed to it. We often think, well, that happened in some other place. But this personal experience I saw with my own eyes and heard with my own ears. I believe it from the bottom of my heart!

Tonga Malohifo‘ou is a Tongan native. He didn’t go to college. . . . He’s black. But, he’s an elder of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and he’s got the power of the Lord with him. He’s got faith to move mountains, to stop hurricanes, to rule the elements. There isn’t any other power in the world—presidents or kingdoms or dominions—that have power such as that. With all my heart, I bear that testimony.

I don’t preach this thing. I haven’t made a complete survey, but it was a little interesting thing that I noticed. I particularly took notice in Neiafu and all the little villages that I visited of the houses where we held our po malangas, our meetings. All the houses that had accepted the missionaries, or accepted our message, their houses had been spared.

In Holonga, there is a man called Tilini, who is the father of a boy in Liahona, Peni Tilini, from Holonga, Vava‘u. This man told me, since I arrived at Vava‘u, that he doesn’t believe the Church. He will not—never—believe it. But he loves his boy, who belongs to the Church. And, as long as he lives in Holonga, the missionaries can use his large lumber house to hold meetings and gather all the village. That was a great thing to me.

Every house in Holonga was severely damaged except that one that we had held our meetings in—the house of Tilini. Even the little fale peito where they gather to eat was spared too.

This was an interesting matter to me that his house still stood—the only house. No! There were a few more on Holonga that stood, but the two houses that were the only two that would let us have our missionaries meet in, they were the houses that were spared in Holonga.

It was the same in Leimatu‘a. I noticed some of the houses. Of course, some of the places we tracted, and they accepted our message, have fallen. But the huge ones where we held our big meetings—which should have been taken, along with the others—were spared. It was almost like a little testimony to me that the Lord spared them because of their love for the Mormons, and their acceptance of our message. . . .

I’ll think of a million things after a while. It seems like I’m on fire right now, and I almost wish that I had the words of a radio announcer or of someone who could really show what had happened. This was quite an experience, but it was a wonderful experience. Even though it was very destructive, I’m glad that I experienced it. I have seen a hurricane in the tropics which—is a devil!

The greatest thing that I was thankful for was that I witnessed the power of the priesthood and could see the work of the Saints that knew what it was all about. The outsiders had already given up hope and knew that it was their last day. But all the members of the Church kept their heads, and they were the ones that saved the people from being killed . . . in their moving the people, literally, bodily, to our chapels so that they could be saved. Also, the commanding of the elements: that Tonga commanded the elements to stop. I really think this should be a testimony to many people that read or hear of this recording.

Well, there is one more little story that I want to tell you, which I think is quite a touching little story and which is one that touches my heartstrings because I am very well acquainted with the two people that are involved.

In all the confusion that was demonstrated during those days, there was a man, or actually a boy, called Viliami Saulala and his little wife, who is a convert to the Church. Viliami had grown up in the Church. When he was fourteen years old, he was taken to Fiji for schooling. When he returned to Tonga, he met this little girl called ‘Ivoni. Even though she is [was] an outsider (she studied several years in a Fiji convent), she is a very attractive little girl and she was very attracted to this Mormon fellow.

Viliami is the typical native. He’s very well built, very good looking, and strong. Above all he has a tremendous faith and power in the Church. But when he met this little outside girl, he fell in love with her. He couldn’t see any other girl. He told me, before they were married, that there was no other Mormon girl he wanted to have more than this little girl. As far as obedience and virtue were concerned, this girl was about as high up as you could get. So they were married. Viliami tried to preach the gospel to her, but she wouldn’t believe, wouldn’t listen to him. Even though she was an obedient girl, she just couldn’t understand the gospel.

We started visiting this little girl in November and had given her about four lessons. She told us she believed the Church and would be baptized, not because of her love for her husband, but because she really believed the Church, for which I was very thankful. She was baptized in the Church the last of December. She showed the fruits of repentance and of coming into the Church by her coming to all the meetings. She received her first position in the Church last month, two weeks before the hurricane hit.

Even though she was baptized, yet she still didn’t have a good understanding of the gospel—as far as we know it, we who have grown up in the Church. But she did have a tremendous love for her little position in the Church. She received the position of secretary to the Primary in Neiafu. She was really happy that she had a chance to work in the Church, even though it was a “little” job. She really worked at it and was proud of being able to help the children and keep the records of the Primary.

When the great hurricane hit (as Viliami told me after afterwards), they were in his large house. Viliami is quite well off. There are just the two of them. Viliami knew the house was going down as it was shaking like a caterpillar shakes a tiny shack. He told his wife that they had better make a break for it.

At that particular time, about ten o’clock Thursday morning, the wind was at its worst. . . . Outside, the trees were being ripped up. The wind was taking tin and two-by-fours and twisting them all around in the air. It was a dangerous situation to go outside.

However, Viliami knew that if they stayed in the house, they would be crushed. So he grabbed the hand of his little wife and ran outside. Just as they got outside, here came a huge two-by-six, being hurled though the air by the great force of the wind. Viliami put up his hand to stop it from his wife, and he pushed her down. The big board, in the force of the wind, hit his hand and broke his arm in two places. Viliami told me that it really hurt him badly, but at the time he didn’t pay any attention to it. He was glad that they were saved, that his wife was safe.

He again grabbed the hand of his wife and again began down the hill, trying to make a break for the church house. Of course, they were dodging here and there, trying to escape being hit by everything which was being hurled around in the air.

Viliami told me that when they were running, every place they had been, a big piece of tin, a two-by-four, or trunk of a tree would hit there. About a half a mile from their house, as they were making a break for the chapel, all of a sudden his wife told him, “Viliami, I forgot my little Primary minute book! Even though we are running for our lives, I want to ask you, please return to our house and try to find the little minute book.” . . .

This was right in the middle of one of the most dangerous, terrible hurricanes that has ever hit the Pacific. Right in the middle of the hurricane, these two newlyweds were fleeing for their lives. When they had almost reached safety, the little girl turned to the boy, her husband, and asked him to return, to again risk his life to return to the house and bring the little Primary minute book that she was so proud of and which she kept with such diligence!

She then told her husband that she would crawl under a huge mango tree that was already torn up by its roots and that he just had to return back to the house. So she crawled under the big mango tree, and Viliami made his way back through wind and rain and muck and mud and trees and tin and everything else that was being torn up and hurled around in the air until he reached the house.

At that time, the house had not yet fallen. But the roof was already torn off and one side of the house had been taken off—which was a very dangerous situation, for him to again enter this house, which would fall any minute. He risked his life again to enter the house and do what his wife had asked him to do: to try to find one tiny minute book that his wife kept for the Primary.

He spent about fifteen minutes looking for the book. Finally, he found it in a box that was still locked and so not wet inside. He opened the box by force, as there was no key around. This is while he had a broken arm! He broke open the box and rescued the little minute book, tucked it into his thick leather jacket and then ran with it.

He told me it was about a half hour for him to run the four hundred yards back to the house and return again to his little wife, who was curled up under the trunk of the huge mango tree. Even though she was wet, she was all right and tickled to death that the little minute book hadn’t been lost. They then went on.

They didn’t reach the church house that day. It was just too bad. They took refuge under a big new house that had just been built in Neiafu. They were safe there.

That is quite a touching little story of how some of these converts believe in the Church, and how they take pride in any tiny position that they can hold in the kingdom of our Lord. Many of the people who hold the “big” positions—stake presidents, high councilmen, etc.—back home don’t take pride and don’t magnify and don’t make dignified their responsibility in the Church (as exemplified by) this good little lesson.

I hope that all the secretaries of the Primaries hear this little story about this beautiful little island girl. She’s a half-caste with beautiful blue eyes. She’s married to one of the cleanest, most handsome, well-built Tongans you’ll ever see. As far as her virtue, and the pride she has in the little position she has in the Primary, it is almost worthy of a prophet’s fakamalo (“gratitude” or “recognition”).

Now, Viliami wouldn’t go to the doctor. He just asked the branch president (Tonga Malohifo‘ou) to administer to him for his arm. He had enough faith that his arm would be healed through the administration! He said that for about three days after it was broken he couldn’t move any part of his hand or arm. After the administration, he could move his hand. One day after the administration, he came very happily to me to show how he could wiggle his fingers very well.

Notes

[1] Extracts from interview of President Mark Vernon Coombs and his wife, Lavera Coombs, by Elder Vernon Lynn Tyler in Tonga, March 29, 1961. Typescript in possession of the authors.

[2] Extracts from interview of Elder Eric B. Shumway (supervising elder of the Vava’u District) at Liahona High School, Nuku’alofa, Tonga, by Elder Vernon Lynn Tyler, April 1, 1961. Typescript in possession of the authors.