Jesse Haven and the Cape of Good Hope Mission

Reid L. Neilson and R. Mark Melville, "Jesse Haven and the Cape of Good Hope Mission," in The Saints Abroad: Missionaries Who Answered Brigham Young's 1852 Call to the Nations of the World, ed. Reid L. Neilson and R. Mark Melville (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 107–134.

Historical Introduction

After arriving in England in early 1856, Jesse Haven wrote to Franklin D. Richards, president of the British Mission, about the two and a half years he had just spent as a missionary in South Africa. “It is not so easy as one who has not had the experience might suppose, to establish the Gospel in a country where it has not before been preached; where the climate weakens the constitution of persons brought up in a northern clime; where the people speak three or four different languages, and are of all kinds, grades, conditions, and complexions; and where there are only two or three hundred thousand scattered over a country twice as large as England.”[1] Despite these difficulties, Haven did his best to fulfill his duties as president of the Cape of Good Hope Mission. There were no church members when he arrived, but during his presidency he created branches of the church. Haven and his companions, William Walker and Leonard Smith, were the first to establish a Latter-day Saint presence on the African continent.

Jesse Haven’s Early Life, 1814–52

Jesse Haven was born March 28, 1814, in Holliston, Massachusetts, a first cousin of Brigham Young and Willard Richards. In his youth, he began thinking about religion. At thirteen, he aligned himself with Holliston’s Congregational Church, where his father was a deacon, and at sixteen, he helped organize a temperance society and a singing school in his neighborhood, which met with derision from his peers. “I mention these circumstances to show that opposition to what I undertook to perform, even in my youthful days, when I knew I was right, instead of discouraging me, made me more zealous,” he recounted. In 1833, he left home and pursued various jobs, but it was schoolteaching that he settled on as a profession. When he returned to his hometown in 1837, “the Elders of the Latter Day Saints had been there and left the Book of Mormon. I read it but did not immediately receive it.”[2]

However, by the spring of 1838, Haven believed and was baptized by Joseph Ball on April 13. Nine days later, he packed up from his Massachusetts home and headed out to join the main body of Saints at Far West, Missouri. He witnessed the sufferings of his fellow Latter-day Saints in the ensuing months. After relocating to Quincy, Illinois, in 1839, he was sent on a mission with Henry Jacobs back to his native Massachusetts: “Our business was to call on the different branches on our journey east, comfort them as much as possible as it was a time of great excitement about the Church.” After his preaching ended, he worked in a shoe business in Massachusetts, where he married Martha Hall in November 1842, and taught school in Rhode Island before once again joining the main body of Saints at Nauvoo, Illinois, in 1843. In 1844, he was part of the Nauvoo Legion[3] and was ordained a member of the Seventy. He left Nauvoo on July 1, 1846, settling in Iowa. In 1848, he was called on another mission, this time to Missouri and the eastern states. That mission ended in 1849, and in 1850, he traveled to Salt Lake City with his wife Martha and “a young lady by the name of Abby Cram,” who was sealed to him as a plural wife a week after their arrival. Haven taught school and farmed for two years in Utah before he was called on another mission.[4]

The South African Mission, 1852–55

In early 1852, Joseph Richards stopped in South Africa, known then as the Cape of Good Hope or Cape Colony,[5] on his way to his mission in India by passenger ship. During his brief time there, he distributed tracts and preached sermons.[6] Richards’s efforts appear to have had little or no effect on the inhabitants of Cape Colony. It was not until August 1852 that Jesse Haven, William Holmes Walker, and Leonard Ishmael Smith became the first men formally assigned to spread the Latter-day Saint message in the region. William Walker, born in 1820, had been baptized in 1835 and arrived in Salt Lake City in 1847 after serving with the Mormon Battalion.[7] Leonard Smith, born in 1823, had been baptized in 1847 and arrived in the Salt Lake Valley in 1851.[8] Haven, Walker, and Smith left Utah together on September 15, 1852. “I left my family with tears in their eyes; I felt bad when I left—prayed to God to sustain me on my journey, and sustain me in my absence,” Haven wrote in his journal.[9] After traveling across the United States, over the Atlantic, and stopping temporarily in England, they arrived at Cape Town, on the southwest coast of the Cape of Good Hope, and went ashore on April 19, 1853.[10] Shortly thereafter, they ascended Lion’s Head, a small mountain of 2,200 feet, and dedicated the land for their preaching. Elder Haven then prophesied that “the Church now organized in the Cape of Good Hope, will roll forth in this Colony, and continue to increase, till many of the honest in heart will be made to rejoice in the everlasting Gospel.”[11]

The church did not “roll forth” without considerable opposition. As repeatedly happened elsewhere in the world, the local clergy objected to this new religion in town, doing what they could to stop them, and mobs frequently broke up the Latter-day Saint meetings. Still, Haven and his companions did have their successes; on May 26, 1853, the first two converts were baptized, and a branch was formed in the Cape Town suburb of Mowbray in August. By the end of 1853, William Walker extended his efforts to the settlement of Grahamstown, near the eastern coast of the country, accompanied by John Wesley, one of his converts; and a few months later, Leonard Smith left for Port Elizabeth, also to the east, with Wesley joining him soon thereafter. By the beginning of 1855, there were more than 125 Latter-day Saints in South Africa.[12]

A British colony, South Africa was an ethnically diverse nation. Various African tribes, including the Khokhoi, Zulu, and Xhosa, had inhabited the country for millennia. During the seventeenth century, Dutch colonists established Cape Town, and their descendants formed the Afrikaans-speaking Afrikaner population. The Dutch also brought slaves from Southeast Asia, who formed the Cape Malay population. Around the turn of the nineteenth century, the Cape came under British control, with the first prominent group of English settlers arriving in 1820. Initially, Haven and his companions preached among the English-speaking population—a practice that made sense since Latter-day Saint missionaries in England were meeting with considerable success.[13] Haven later found it important to also preach to the Afrikaner population. He had pamphlets translated into Dutch (or perhaps its linguistic daughter, Afrikaans) in 1854. Haven, his companions, and their new converts visited the Dutch towns of Stellenbosch, Paarl, Malmesbury, and D’Urban in 1854 and 1855. Haven tried to learn Afrikaans, but he never became fluent, and there were not enough bilingual converts to be effective in preaching to Afrikaners. Cultural and religious traditions also made it difficult for those of Dutch descent to heed the Latter-day Saint message. Indeed, during the nearly three-year mission to the Cape of Good Hope, there might have been only one Afrikaner convert.[14]

Besides these European peoples, Haven also mentions “coloured people” in his letters, including the Muslim Cape Malays. There is no evidence of an organized effort to preach among these people, but shortly before his departure, Haven visited a Muslim clergyman. “I then told him of Joseph Smith and of the visions given to him. He was anxious to learn more about him,” Haven described. “It is my opinion that many of them will yet receive the Gospel.”[15] The other nonwhites, however, were the native African tribes, and there is no evidence of Haven and his companions ministering to them. According to his own words, these peoples “have too much of the blood of Cain in them, for the Gospel to have much effect on their dark spirits”[16]—a reflection of nineteenth-century biases and ideas about race. In February 1852, Brigham Young had laid out his views, commonly held in America and Europe, of Africans being descended from biblical Cain, the first murderer, and initiated a ban for those of African descent to receive the priesthood.[17] It is unclear, however, to what extent the priesthood ban was an obstacle to Haven’s preaching to the native Africans; cultural and linguistic barriers likely played a more substantial role. Missionaries frequently struggled to reach non-European peoples; for example, James Lewis and his companions had difficulties taking their message to the Chinese.[18]

In 1855, word arrived from church leaders in Utah that Haven and his companions were welcome to depart whenever they were ready. On November 27, Walker and Smith boarded the ship Unity, which had been purchased by some well-to-do converts, and sailed away the following day with fifteen other members. Circumstances did not permit Haven to leave with them, so he left two weeks later on the Cleopatra, but none of the Saints accompanied him on the ship. Local converts took over the leadership of the Cape Town church members.[19]

On his way home from the Cape of Good Hope, Haven spent three and a half months visiting the British Saints in England and Scotland.[20] In May 1856, he and Edward Martin—who had been assigned on a mission to England at the same August 1852 meeting—oversaw more than eight hundred Saints traveling from Liverpool to Boston aboard the ship Horizon.[21] After taking the train to Iowa City, Martin, Haven, and the emigrants outfitted to depart for Salt Lake City starting in July 1856. Haven headed a handcart company for three hundred miles, but this group combined with the Martin handcart company, while Haven joined the Hodgetts wagon company.[22] Haven witnessed firsthand the hardships of the Martin handcart company: “I saw much suffering while crossing the plains—women and children travelling in the snow while the thermometer stood below zero. . . . I have been in this church 19 years. I saw more suffering last fall than I ever saw before among the Saints. I was in Missouri when the Church was driven from there and I believe what the Saints suffered there with the exception of those that were taken prisoners was nothing more than a drop to a bucket compared to what those Saints suffered that came in late last fall.”[23] He arrived in Salt Lake on December 15, 1856, after a harrowing journey, and he met his three-year-old child, Jesse C. Haven, son of Abby Haven, for the first time.[24]

Though Walker and Smith had left the Cape of Good Hope before Haven, Walker, at least, returned to Utah later than Haven. Walker and Smith reached London on January 29, 1856, and did not tarry long in Britain. They boarded the ship Caravan a few weeks after their arrival in England, and they oversaw the emigrating African Saints to America. Smith arrived in the Salt Lake Valley on May 31, 1856.[25] Walker was supposed to head a wagon company to Utah that year, and he had made the necessary preparations to do so, but it was too late in the year, so he stayed behind in the Midwest until the next season and then reached the valley on August 20, 1857.[26] He narrowly avoided the notorious tragedies that Haven witnessed in 1856.[27]

Additional Church Service, 1856–1905

After his return home, Haven quickly became involved in civil and ecclesiastical service in Salt Lake City. He functioned as a chaplain in the Utah Territorial Legislature from 1856 to 1858, and he was also a leader in a militia tasked with defending Utah from Johnston’s Army in 1857 and 1858.[28] He was actively involved in the Fourteenth Quorum of the Seventy, of which he had been a member since 1844, and he resumed his vocation as a teacher.[29]

In 1862, he moved from his Salt Lake City home to establish a farm in Morgan County, northeast of Salt Lake.[30] Soon after Haven moved there, Brigham Young asked him if he would like to take another mission to Africa. Haven responded, “I should not like to go,” because “the climate of Africa is debilitating to both my body and mind, yet I told him that I was ready to do as he said.” He was instead appointed to serve as circuit judge in his new home of Morgan County and adjoining Weber and Davis Counties. “The Office of Judge is an office I have no desire to fill, but as I have been appointed to the place by my brethren I will try to do the best I can,” he recorded.[31] He became probate judge in 1869 and served until 1878. In addition to these civic duties, he also held a variety of ecclesiastical callings on the branch and stake levels in Morgan County. Haven continued to serve in the church until he died on December 13, 1905.[32]

William Holmes Walker similarly lived the remainder of his life in service to the church. He arrived in Salt Lake in August 1857, and he served a mission to southern Utah in the 1860s. He built mills and homes for his wives in Utah and Idaho and evaded federal authorities who were actively pursuing polygamists. He died on January 9, 1908, in Lewisville, Idaho.[33] Less is known about Leonard Smith. He carried the mail from Salt Lake City throughout Utah and apparently established a farm near Tooele, Utah, where he was shot and killed during an altercation with his nephew in July 1877.[34]

Jesse Haven’s Family Life

Jesse Haven married Martha Hall in November 1842, and they were sealed in February 1846 in the Nauvoo Temple. In 1848, Haven and Martha moved to Iowa with four orphans whom they were caring for. It is not known how long they cared for these children, though they probably remained in the Haven family through Haven’s mission to the eastern United States. In 1850, Haven and Martha traveled to Salt Lake City with Abigail Cram, and he and Abigail were sealed to each other a week after their arrival.[35] The 1850 census shows a five-year-old Abby and a three-year-old Martha living with Haven and Martha, but it is not clear whether these really were children living with them or simply a census error (they do not appear in the 1860 census).

When Haven left for his mission in 1852, it was the last time he would see his father, John Haven, who died in Salt Lake City in March 1853.[36] In June, however, Jesse Haven’s family grew when his wife Abby gave birth to a son, Jesse Cram Haven.[37] Martha, Haven’s other wife, followed her husband by becoming a teacher, which might have provided income for the family during his absence, though it is not clear at which point she took up teaching.[38]

When Haven returned home in 1856, young Jesse was more than three years old. In March 1857, he married a third wife, Sarah Taylor, who had traveled west with him in 1856, but they divorced in 1860.[39] Martha bore no children before her death in 1861.[40] Haven and Abby apparently gave birth to a daughter, Marie, in 1857 or 1858, but little is known about her. Haven and Abby faced an ordeal when their son, Jesse Cram Haven, died on April 14, 1879, at the age of twenty-five, leaving behind a wife and two children.[41] Abby died at Enterprise, Utah, on December 4, 1904, and Haven died the following year on December 13, 1905.[42]

Source Note

Between August 1853, four months after Haven and his companions arrived in Cape Town, and May 1856, about the time he was preparing to sail from England to America, Haven wrote eleven letters to Presidents Samuel W. Richards and Franklin D. Richards, which were published in the church’s Millennial Star periodical.[43] The last three of these letters were written while Haven was in the British Isles, and these three are presented in this chapter as they appeared in that publication. The first of these letters describes the missionaries’ journey to the Cape of Good Hope and their proselytizing efforts there; the second and third primarily describe the people, cultures, and climate of the country.

Document Transcripts

Jesse Haven to Franklin D. Richards, February 25, 1856[44]

107 Finch Street, Liverpool,

February 25, 1856.

President F. D. Richards.

Dear Brother—I have written a lengthy report of my proceedings since I left G. S. L. City, and also an account of the situation of the Mission at the Cape of Good Hope, and have sent it to the First Presidency in Zion.[45] Instead of sending you a copy of this report, many items of which have already been forwarded to you, I have concluded to extract from it such items as have not appeared in my former communications to the Liverpool Office.[46]

Elders William Walker, Leonard I. Smith, and myself arrived in Liverpool January 4, 1853, on our way from Utah to the Cape of Good Hope. Here we found President S[amuel]. W. Richards ready to lend us all the assistance he possibly could. I must say that his conduct towards the Elders, when they landed in Liverpool, was more like that of a father, than of a young man just emerging into the active scenes of life. His kindness will long be remembered by me, and, considering the multiplicity of business on his hands, I was surprised at the attention which he gave to every call. I remained in Liverpool and its vicinity until January 22nd. Having then obtained means for the further prosecution of my journey, I left Liverpool for London, and wrote to brothers Walker and Smith, who had gone to other parts of England, to meet me there. I remained in London, visiting and preaching among the Saints, who received me with great kindness, until February 11, when, between two and three o’clock, p.m., Elders Walker, Smith, and myself embarked on the barque Domitia,[47] bound for the Cape of Good Hope.

As an account of our voyage, arrival at the Cape, and success in preaching, and the organization of Branches and Conferences has been forwarded to the Office in Liverpool before, I will pass over it to matters which more particularly pertain to the mission at the present time.

Many tracts have been circulated,[48] and some preaching has been done among the Dutch in Cape Colony, but only a few have yet received the Gospel. They, as well as other classes of the natives, are much attached to the country, and the idea of leaving it frightens them. Their religion is the Dutch Reformed.[49] Only to suggest the idea that their church is not the true one, causes them to look astonished, and they seem to say—“Is it possible!”

Owing to the prejudices of the Dutch against the English in this colony,[50] if Elders should be sent to labour among them, I would suggest that they be not natives of England. Americans or Scotch would do very well, and a native of Holland still better, for they think much of their mother country, and everything that comes from it.

Through fear of another Kaffir war,[51] the Colonial Parliament have passed a law, that all males in the Colony, between twenty and fifty years of age, shall do military duty, except ministers of religion, and some others. The brethren, who had been ordained to the office of either Elder or Priest, claimed exemption from military duty, as “ministers of religion.” They appeared before the committee, appointed by the government to decide such cases, but they refused to decide on their case, and referred it to the Attorney-General. In a few days the brethren were informed that he had decided, that they could not be exempted from doing military duty. I immediately, in company with the brethren, paid this dignitary a visit, and requested the privilege of laying before him the organization of our Church, that he might see that my brethren were exempt from doing military duty, according to law; but he refused to hear me, and said, “I have given you my decision, and if you don’t like it, you may take it before the Supreme Court.” After this I wrote a letter to the Committee before mentioned, requesting a hearing before them, and had my brethren sign it. As I left soon after this letter was written, I am not prepared to state the result; but I told the brethren to claim their rights, and if possible get a hearing before some one in authority, for this is the way that the Lord will prove the rulers of the earth, and see if they will do justice to the Saints.

When I left, 176 had been baptized in Cape Colony. Of these about 30 are natives, the remainder English emigrants; 38 had been cut off, one had died, one emigrated to India, and three to Australia, with the intention of going from these places to the land of Zion; twelve have emigrated to America, via England, two of whom went before those who lately arrived in London on the Unity;[52] leaving now 121 Saints in Cape Colony, in good standing. When I left, the work was still spreading. A number, I believe, would soon be baptized, if there were Elders there to labour among the people. We have ordained some of the brethren to be Elders, and appointed them to preside over the Saints whom we have left behind. I believe that they will prove faithful, and act up to the light which they have.

The Saints are anxious to have more Elders sent to them, and the universal question they asked was—“When do you think that we shall have more Elders from Zion.” Of course I could not tell them, but I promised that I would lay their case before the authorities over me.

While in Cape Colony, I paid out about £33 for printing. There has been from £140 to £150 worth of books sent from Liverpool, for the benefit of the mission. I have remitted £40 to the Office in Liverpool by mail; and Elder Walker and myself, since our arrival in England, have paid £45 19s. 9d. There has been collected in the Colony, and remitted to the Liverpool Office, £16 6s. 7d. for the P. E. Fund.[53]

When Elder Walker left, agreeable to my instructions, he appointed Elder Edward Slaughter,[54] of Port Elizabeth, book agent for the Eastern Province, and Elders Walker and Smith left in his hands all the books which they had in their possession, belonging to the mission. When I left, I appointed Elder Richard Provis,[55] who lives at Mowbray, general book agent for the whole Colony, until such times as other arrangements are made. The expense of freight, duties, &c., on books sent to the Colony, has been considerable, so that I have been obliged to sell them much higher than they are sold in England. I have given away many pounds worth of books and pamphlets to spread the work, paying for them partly out of my own pocket, and partly by occasional contributions from the Saints of the Cape Conference.

I have kept a strict account, in writing, of everything pertaining to the financial affairs of the mission, and left it in the hands of brother Provis, so that whoever comes after me can see the course I have pursued. I have not been in the habit of trusting out books, except to Elders Walker and Smith, who have acted as agents. After brother Slaughter was appointed agent of the Eastern Province, I sent him a letter of instructions, in which I made the following remark—“I do not make it a practice to trust out any books, &c., except to agents; if I am ever so foolish as to do it, and the persons neglect to pay, I pay it out of my own pocket, and not let the mission suffer for it.” My object has been to manage so that the cash and books on hand would at any time pay what the mission owed.

Just before I left, I took an inventory of all the cash, books, pamphlets, &c., which were on hand, also what were in the hands of Elders Walker and Smith, as agents, prizing them at the Liverpool wholesale price; and I found that the amount was about £12 more than the mission was owing to the Office in Liverpool. There were also £9 8s. 11d. worth of pamphlets on hand, which I have had printed in the Colony, and the expense of publishing paid. These I have left for the benefit of the mission, which makes upwards of £20 worth of books in the Cape of Good Hope Mission over and above what the mission is owing. For want of proper mail facilities, I have laboured under many inconveniences in forwarding the Star and Journal of Discourses[56] to my brethren. For the same reason it has been difficult to circulate pamphlets, &c., through the country.

In my instructions to the Saints, I have endeavoured to teach them the first principles of the Gospel, and the gathering, and that it was of more importance to learn how to live their religion, day by day, than to be troubling themselves about doctrines and principles that did not immediately concern them. I have tried to lay before the Saints the object of the P. E. Fund, and urged them to do what they can for it. I have also taught them the principle of Tithing. When speaking on this subject, I have always been impressed upon to say to them, that when they gather to Zion they should not only be willing to pay one-tenth of their property to build it up, but ten tenths, adding themselves, wives, and children, in order to secure the bargain of eternal salvation.[57] This is the way that I understand the revelations of Jesus Christ, which I have made my study since I have been from the body of the Saints.

It is not so easy as one who has not had the experience might suppose, to establish the Gospel in a country where it has not before been preached; where the climate weakens the constitution of persons brought up in a northern clime; where the people speak three or four different languages, and are of all kinds, grades, conditions, and complexions; and where there are only two or three hundred thousand scattered over a country twice as large as England.[58]

I have often felt, while I have been on this mission, as though the privilege of having the society and counsel of those who preside over me, if only for a few moments, would be invaluable. My situation has often driven me to the throne of grace, and my prayer unceasingly has been, “Lord, give me wisdom, that I may know how to manage the things committed to my care.”

As President of the mission, I have not accomplished as much as I could wish, yet, if those who sent me and my brethren are satisfied, I am. If they are not satisfied, and think that I need correction, all I ask is, that I may receive the chastisement with meekness, and kiss the hand that inflicts it.

Having made my report to you, and to the First Presidency of the Church, whose characters I trust I shall ever hold sacred, sustain, and defend, I feel the responsibilities that were placed upon me in August, 1852, rolling off; and when I shall have arrived in Utah, with the Saints now on their way from Africa, I shall consider that the mission appointed to me, nearly three years and a half ago, is fully and completely closed; yet, I trust that I shall ever hold myself ready, at a moment’s warning, to take other missions, or do whatever those who preside over me shall be pleased to direct.

If it was not for fear of exhausting your patience, I would continue writing, and express the feelings of my heart, for it is full of gratitude to my Heavenly Father, for the light of the Gospel and the plan of salvation revealed through Joseph the Prophet. I have never enjoyed myself better than when I could stand before Saints and sinners, and declare unto them the Divine mission of our martyred Prophet, saying to them, that he, under Christ, would be the leading judge of this generation, for he was sent to this generation, and if they would not believe it, the time would come when they should know it, to their sorrow and condemnation.

Will not I defend the character of the Prophet Joseph? Yes, I will before all men, for he was the instrument in the hands of God of giving me and my brethren the Holy Priesthood, through which we obtain light, knowledge, and salvation. Will I not defend and uphold those men whom he has ordained and left to carry out the work which he commenced? Yes, for on them I am dependent for further light, knowledge, and keys of exaltation, while they also, in connection with him, will be the judges of this generation. May his words, who sealed his testimony with his blood, delivered to the Quorum of the Twelve before his death, ever be fresh in my mind—“There is not one key or power to be bestowed on this Church, to lead the people into the celestial gate, but I have given you, showed you, and talked it over to you; the kingdom is set up, and you have the perfect pattern, and you can go and build up the kingdom, and go in at the celestial gate, taking your train with you.”[59] My prayer is that I may be one of this train.

I will here say, in regard to Elder Richard Provis, whom I appointed general book agent at the Cape of Good Hope, that I have given him instructions in the business, and I am perfectly satisfied that all books, pamphlets, &c., sent to him will be seen to and taken care of, and a strict account kept of all moneys received for them, or for the P. E. Fund, and that it will be forthcoming when called for.

I certainly feel interested for the mission and the Saints at the Cape of Good Hope, and wish to do all I can for their benefit. My business is merely to present the situation of the mission to those who preside over me, then leave it for them to act as they think proper.

I remain your brother in the covenant of peace,

J. Haven.

Jesse Haven to Franklin D. Richards, April 26, 1856[60]

41 Charlotte Street, Glasgow,

April 26, 1856.

President Richards.

Dear Brother—According to a promise in a previous letter, I take my pen to note a few things in regard to the country, climate, and people of the Cape of Good Hope.

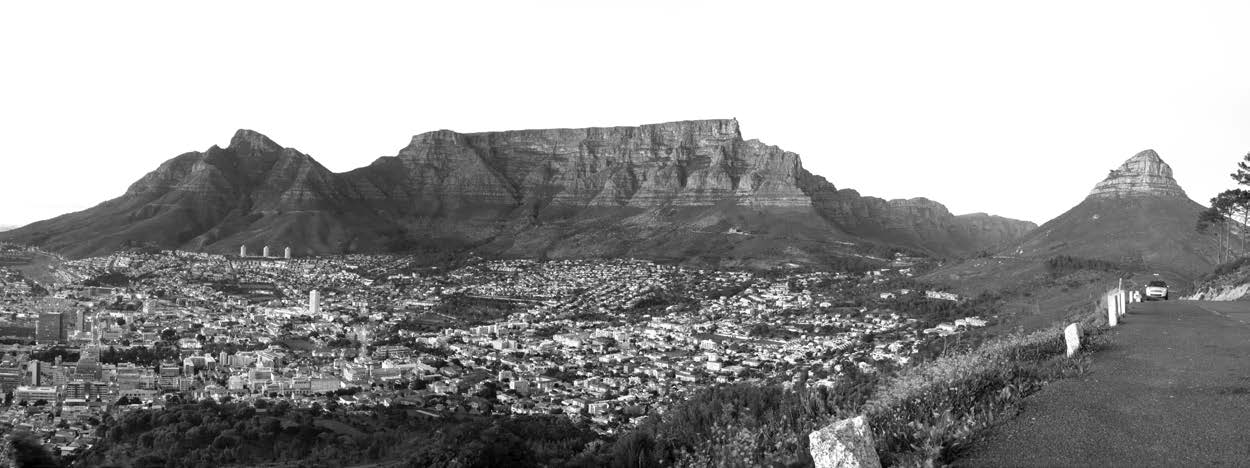

The colony is divided into the eastern and western provinces. Cape Town, the largest town in the colony, is in the western province, and situated on the south-west side of Table Bay. On the south side of the town commences the base of Table Mountain, which rises to the height of nearly 3,800 feet above the level of the sea; the upper half is nearly perpendicular.[61] On the west side of the town is a point called the Lion’s Head, which is nearly as high as Table Mountain, being the highest part of a mountain extending along on the north-west side of the town, which has the appearance, when at sea, of a lion lying on his belly.

Elders Walker and Smith, and myself went on this mountain, on the 23rd day of May, 1853, and organized a Branch of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, in the Cape of Good Hope, consisting of us three as members. I there and then prophesied that the Church that day organized in the Cape of Good Hope, would roll forth in that land till many of the honest in heart would be made to rejoice in the everlasting Gospel. I rejoice that I tarried there long enough to see this prophecy literally fulfilled.

Modern-day Cape Town. Table Mountain is pictured behind the city, and Lion’s Head is at the far right. Courtesy of Pixabay.com.

Modern-day Cape Town. Table Mountain is pictured behind the city, and Lion’s Head is at the far right. Courtesy of Pixabay.com.

Cape Town has about 30,000 inhabitants. About one half are coloured people—being of all shades from a jet black to almost a European complexion. A large portion of the coloured population were formerly slaves; but by an Act of the English Parliament, they were emancipated in the year 1838.[62] Those of them called Malays, are Mahometans, and according to their religion, they are permitted to have and do have a plurality of wives.[63] Sometimes the English who have emigrated to that colony, intermarry with them, and then adopt their religion. They are generally very quiet people, attending to their own business, though they occasionally practise witchcraft on those with whom they get offended. There is less drunkenness and licentiousness among them than among the whites, or Christians. I called on one of their priests a few days before I left the Cape. He treated me kindly. He said the Mahometans believe there have been six great Prophets on the earth of equal authority, for these six have given the commandments; they are Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus Christ, and Mahomet; Mahomet was the last one; no more are to come.[64] He said Christ is coming again, and when he comes, we shall all see and understand alike. As he believed in the Old Testament, I asked him if it did not look reasonable that there should be a seventh Prophet, as seven is a Bible number? He acknowledged it looked reasonable, though he had never thought of it before. I then told him of Joseph Smith and of the visions given to him. He was anxious to learn more about him. I gave him a small tract in Dutch, giving an account of the visions of Joseph, as he could not read English, nor converse much in that language.[65] It is my opinion that many of them will yet receive the Gospel. I believe they are the descendants of Abraham by his wife Hagar, that is, those who are the pure blooded Malays.[66] They have long, straight, black hair, skin darker than the American Indian, and none of the Negro features in them. They practise circumcision on their male children, when they are about thirteen years of age; or from thirteen to sixteen. The Malays are scattered more or less through the whole colony. They, and the other coloured inhabitants, form a large portion of the population, perhaps nearly one-half.

The whites are principally English and Dutch, and their descendants. The English language is spoken more or less throughout the whole colony; yet, in many towns and among the scattered farmers in the western province, but very little English is spoken; the white inhabitants being principally of Dutch descent. An Elder, to labour successfully among them in spreading the Gospel, should be acquainted with the Dutch language.

The English language is spoken more in the eastern province than in the western. It was settled more by the English, as the whites did not settle there much, until the colony came into the possession of the English, which was in the year 1806.

It is my opinion that there are some honest in heart among the Dutch in that land, who will yet embrace the Gospel.

An Elder to travel among them should be provided with a good horse, saddle, and bridle, and dress respectably. If he goes in this way, he can travel without money, and both him and his horse will be fed and lodged, and he will be provided for much better than he would be were he to go on foot, as has been the practice of Elders in this country and in America; because, if he should go on foot, they would look upon him as some poor vagabond. Their ministers all ride on horse-back, and they expect to see every man that preaches the Gospel, when he travels, ride a good horse; and they have a great respect for preachers of the Gospel.

The winter there, which is at the time of our summer months here, is the rainy season, and the season in which the agriculturist must grow his vegetables and grain, unless he has low moist land, or land that can be irrigated; for the summer is very dry and hot, there being little or no rain.

The rains in the western province generally commence in April, and continue more or less until November; though there are many beautiful, pleasant, fair days in the winter season.

Occasionally there is a light frost on low land in the winter, and sometimes snow on the surrounding mountains. All kinds of tropical fruits grow in the colony, such as oranges, lemons, &c.

Wine and raisins are manufactured from grapes that grow in the country, which are plentiful in the western province, though many vineyards have gone to ruin since the abolition of slavery.[67] The wine is generally cheap, and is much used by those who have emigrated there from Europe, causing much drunkenness, and a hindrance to the spread of the Gospel.

The natives of the country are not so much addicted to drinking as are the emigrants from Europe. The grape is the best fruit that grows at the Cape. It is a great country for flowers. Trees and shrubbery grow rapidly there. There is a tree there called the Gum-tree, brought there, I believe, from Australia or New Zealand. I have seen them, only 10 years old, 80 feet high, and 3 feet in circumference at the bottom. They make excellent timber which is sometimes used for masts for ships. If they would grow in the Valley as they do at the Cape, we could soon have plenty of timber there.[68] I sent some of the seed on when the Enoch Train sailed.

The climate of the Cape of Good Hope is weakening to the constitution of all who are raised in a cold climate. I found it had that effect on me. I feel much stronger since I came to this country. The climate is called very healthy for a warm one. The air is pure, and the natives live to a good old age.

I find I am making this communication too lengthy; I will therefore close by promising another slice on the same subject at some future time.

That the Lord may bless you is the prayer of your brother in the kingdom of peace,

J. Haven.

Jesse Haven to Franklin D. Richards, May 13, 1856[69]

41, Charlotte Street, Glasgow,

May 13, 1856.

President Richards.

Dear Brother—In accordance with my promise in my last communication, I take my pen to give you some further items about the country, climate, and people of the Cape of Good Hope.

In my last letter, I spoke more particularly of the Western Province of Cape Colony, I will now speak of the Eastern Province, some parts of which I had the privilege of riding over, a few months before I left.

The Eastern Province, as well as the Western, is rocky and mountainous; timber and water are scarce, and there is much barren uncultivatable land. Near the sea shore, there are hills and almost mountains of white sand, which, at a distance, look like mountains covered with snow. The inhabitants are far apart. Sometimes I have rode for miles without seeing a house. To find the honest in heart in this part of the world, seems like fulfilling the prophecy of Jeremiah, where he speaks of the fishers and hunters being sent out in the last days—“And they shall hunt them from every mountain, and from every hill, and out of the holes of the rocks.” I believe this prophecy, of the old Prophet, was literally fulfilled, in me and my brethren.[70]

In my travels in that part of the country, I beheld much of the effects of the last Kaffir war. Houses and forts are in ruins, being the remains of fires lit by the torch of the savage. The inhabitants were rife with accounts of the cruelties inflicted by the Kaffirs,[71] on those whom they took prisoners; such as flaying them alive; cutting them up inch by inch until they would die; fastening them down to the ground, and there leaving them for the ants to destroy—an insect prevalent in that part of the land—fastening them to a stake or tree, for the purpose of permitting the Kaffir boys to practice throwing the asseyai at them, a weapon much used by the Kaffirs in war, and in hunting.[72] The inhabitants are continually in excitement through fear that the Kaffirs will come on them again.

The Kaffirs have a plurality of wives. They buy their wives with cattle, which they have in abundance, though of late, the cattle sickness has been among them, as well as among the whites, and carried off thousands and tens of thousands of their cattle. Among themselves, where they are away from the whites, they go almost entirely, and sometimes wholly, in a state of nudity; yet there is more virtue among the sexes, with them, than there is among the whites. Death is the penalty of adultery. They circumcise their male children, between the ages of twelve and sixteen years. Some suppose that they are descended from Ishmael; if so, they must have mixed up with some of the African tribes, for they have some of the negro features about them—colour, nearly black, and woolly heads. The men are large and athletic.

There is another class of blacks, called the Fingoes; they are like the Kaffirs in features. Formerly they were the Kaffirs’ slaves, but they revolted from them and united with the whites in the last war. They now live among the whites as servants. They have some large villages in the Eastern Province. They also practise circumcision, and have a plurality of wives.[73]

Misionaries are labouring among them, as well as among the Kaffirs, and trying to convert them to modern Christianity, but their success is limited, for the Kaffirs do not like the idea of giving up all their wives except one, which they must do to conform to the “holy religion” of the 19th century.[74]

The English bishop at Natal has a little consistency; he proposes that those who receive the Christian religion, and have already a plurality of wives, should be permitted to keep their wives. I think that this proposition of the bishop’s is a choker to some of the “pious, good, sanctimonious” missionaries of that land.

There is a class of blacks in the Cape of Good Hope, called the Hottentots, who are said to be the original natives of that part now occupied by the whites. They are altogether a different race from the Kaffirs and Fingoes; not so dark, but more degraded.[75]

They are scattered more or less over the Colony, and have mixed up much with the whites by intermarrying, &c.

In the last Kaffir war the body of them joined the Kaffirs.

Missionaries have been labouring among them, trying to convert them to Christianity. They have succeeded in introducing among them some of the licentious customs of our refined cities. Some of the missionaries, in their great zeal to exalt them, have married their women. I think that they, and the Kaffirs and Fingoes, have too much of the blood of Cain in them, for the Gospel to have much effect on their dark spirits.[76]

Much wool is grown in the Eastern Province which is taken to Port Elizabeth on waggons, drawn by oxen—generally from 12 to 18 hitched to one waggon. Port Elizabeth is a seaport, lying on Algoa Bay. The wool is taken from there and shipped to England.

Severe hail storms occasionally occur in the Eastern Province. A farmer informed me that one passed over his farm in October 1854. The hail fell eighteen inches deep, in fifteen minutes, in front of his house, the cloud broke just above his house. His wheat was nearly ready to harvest; but not a vestige of it was left. It killed about thirty sheep for him. The hail stones were about two-thirds the size of hen’s eggs. The trees in front of his house, were literally barked by them, which I plainly saw.

If time and circumstances would permit, other items of interest might possibly be related, but I will close for the present.

That heaven’s choicest blessings may rest upon you, is the prayer of your brother in the Covenant of peace,

J. Haven.

Notes

[1] “Foreign Correspondence: Cape of Good Hope Mission,” Millennial Star 18, no. 12 (March 22, 1856): 191; p. XXX herein.

[2] “The Biography of Jesse Haven,” in Haven, journals.

[3] The Nauvoo Legion was a unit of the Illinois state militia created in 1840 when the city of Nauvoo was incorporated. It was created to defend both city and state. Joseph Smith called the legion to action in 1844 when tensions were high between Latter-day Saints and dissenters. The name was later used in Utah to refer to a militia of Latter-day Saints. Philip M. Flammer, “Nauvoo Legion,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 3:997–99; Mike Trapp, “Nauvoo Legion,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 826–27.

[4] “Biography of Jesse Haven.”

[5] The Cape of Good Hope, Africa’s southernmost point, is located about thirty miles south of Cape Town, South Africa. Merriam-Webster’s Geographical Dictionary, s.v. “Cape of Good Hope.”

[6] Cannon, “Mormonism’s Jesse Haven,” 446.

[7] Walker, Life Incidents and Travels of Elder William Holmes Walker, 5–15; “Walker, William Holmes,” in appendix 2, p. XXX herein.

[8] “Smith, Leonard Ishmael,” in appendix 2, p. XXX herein.

[9] Haven, journals, September 15, 1852.

[10] Wright, “History of the South African Mission,” 24–35, 59.

[11] Haven, journals, May 23, 1853.

[12] Wright, “History of the South African Mission,” 59–118; Haven, journals, May 26, 1853.

[13] David Cook, “England,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 337.

[14] Cannon, “Mormonism’s Jesse Haven,” 446–56.

[15] Jesse Haven, “Foreign Correspondence: Cape of Good Hope Mission,” Millennial Star 18, no. 20 (May 17, 1856): 318; p. XXX herein.

[16] Jesse Haven, “Foreign Correspondence: Cape of Good Hope Mission,” Millennial Star 18, no. 23 (June 7, 1856): 366–67; p. XXX herein.

[17] Reeve, Religion of a Different Color, 152–58; Mauss, All Abraham’s Children, 215.

[18] See chapter 6, “James Lewis and the China Mission,” herein.

[19] Wright, “History of the South African Mission,” 106–38; Enduring Legacy, 8:211.

[20] Stephens, “Jesse Haven,” 56–59.

[21] Sonne, Ships, Saints, and Mariners, 98.

[22] “Biography of Jesse Haven.”

[23] Haven, journals, December 15, 1856.

[24] “Biography of Jesse Haven”; Stephens, “Jesse Haven,” 62–69.

[25] “Elder Leonard I. Smith,” Deseret News, June 4, 1856.

[26] “Elder William Walker,” Deseret News, August 26, 1857.

[27] Walker, Life Incidents and Travels of Elder William Holmes Walker, 58–63.

[28] In 1857, President James Buchanan sent an army of soldiers, under the command of General Albert Sidney Johnston, to suppress a perceived Mormon rebellion in Utah. The Nauvoo Legion, a militia of Latter-day Saints, was sent to push back against the approaching army by burning wagons, scattering livestock, and doing other stalling tactics. Johnston’s Army finally entered Salt Lake City in June 1858, but the Saints had temporarily relocated southward and left the town empty. Thomas L. Kane, a friend to the Mormons, helped negotiate a peaceful resolution to the conflict. Audrey M. Godfrey, “Johnston’s Army,” and Richard E. Bennett, “Utah War,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 580–81, 1282–84.

[29] Stephens, “Jesse Haven,” 72–88.

[30] Stephens, “Jesse Haven,” 90–93.

[31] Haven, journals, April 23, 1862.

[32] Haven died at his grandson’s house in Morgan County, Utah, either at Peterson or at Enterprise. A burial notice in the Deseret News stated that Haven died “at Preston,” but that was likely a misprint. Stephens, “Jesse Haven,” 95–110; Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 4:379; “Interment in Salt Lake,” Deseret News, December 18, 1905.

[33] Walker, Life Incidents and Travels of Elder William Holmes Walker, 67–80.

[34] “Murder,” Salt Lake Tribune, July 20, 1877; “Smith, Leonard Ishmael,” in appendix 2, p. XXX herein.

[35] “Biography of Jesse Haven”; Stephens, “Jesse Haven,” 13, 20, 24.

[36] “Biography of Jesse Haven.”

[37] Haven, journals, December 22, 1853.

[38] Barlow, Israel Barlow Story and Mormon Mores, 411.

[39] Stephens, “Jesse Haven,” 76, 81.

[40] Stephens, “Jesse Haven,” 83.

[41] Stephens, “Jesse Haven,” 105.

[42] Stephens, “Jesse Haven,” 110.

[43] See the following articles in the Millennial Star: “The Cape of Good Hope Mission,” vol. 15, no. 43 (October 22, 1853): 695–96; “The Cape of Good Hope Mission,” vol. 16, no. 11 (March 18, 1854): 173–74; “Foreign Correspondence: Cape of Good Hope,” vol. 16, no. 38 (September 23, 1854): 604; “Foreign Correspondence: Cape of Good Hope,” vol. 17, no. 8 (February 24, 1855): 127; “Foreign Correspondence: Cape of Good Hope,” vol. 17, no. 22 (June 2, 1855): 347–49; “Foreign Correspondence: Cape of Good Hope,” vol. 17, no. 36 (September 8, 1855): 572–73; “Foreign Correspondence: Cape Colony,” vol. 17, no. 49 (December 8, 1855): 780–83; “Foreign Correspondence: Cape of Good Hope,” vol. 18, no. 7 (February 16, 1856): 111–12; “Foreign Correspondence: Cape of Good Hope Mission,” vol. 18, no. 12 (March 22, 1856): 189–91; “Foreign Correspondence: Cape of Good Hope Mission,” vol. 18, no. 20 (May 17, 1856): 318–19; “Foreign Correspondence: Cape of Good Hope Mission,” vol. 18, no. 23 (June 7, 1856): 366–67.

[44] Jesse Haven, “Foreign Correspondence: Cape of Good Hope Mission,” Millennial Star 18, no. 12 (March 22, 1856): 189–91.

[45] This “lengthy report” was thirty-five pages long. Jesse Haven to the First Presidency, January 1856, Incoming Correspondence, Brigham Young Office Files.

[46] See note XXX <<n. 43, “See the following articles in the Millennial Star . . .”>>, herein.

[47] The small bark Domitia was built in 1852. When Haven and his companions traveled on it, they were the only passengers, and they arrived in Cape Town on April 19, 1855. The ship was lost near Gibraltar in 1855. Sonne, Ships, Saints, and Mariners, 59–60; Haven, journals, April 19, 1855.

[48] During his mission to South Africa, Haven published eleven items describing Latter-day Saint doctrines, including the following four pamphlets: Some of the Principal Doctrines or Belief of the Church of Jesus Christ, of Latter Day Saints (Cape Town: W. Foelscher, [1853]); Celestical [sic] Marriage, and the Plurality of Wives! (Cape Town: W. Foelscher, [1853]); On the First Principles of the Gospel (Cape Town: Van de Sandt de Villiers & Tier, 1853; reprinted in 1855, also translated into Dutch); and A Warning to All ([Cape Town]: n.p., [1853]; reprinted in 1855, also translated into Dutch). William Walker also published a few items, and the missionaries brought tracts with them from England as well. Whittaker, “Early Mormon Imprints in South Africa,” 404–9; see also Cannon, “Mormonism’s Jesse Haven,” 450.

[49] The Dutch Reformed Church began in the Netherlands in the sixteenth century during the Protestant Reformation, and it spread to South Africa starting in 1652. The religion embraced Calvinistic ideas, such as unconditional election (God has elected whom he will save) and irresistible grace (the elect cannot reject God’s grace). The Reformed Dutch Church was a key aspect of European colonialism in South Africa. Gerstner, “A Christian Monopoly,” 16–30; Oxford Dictionary of World Religions, s.v. “Dutch Reformed Church,” 298–99.

[50] The Dutch were the first Europeans to colonize Cape Town and Cape Colony, beginning in 1652, but the British took over from 1795 until 1803 and again in 1806. In 1820, many settlers arrived from England to Cape Colony, and in the 1820s and 1830s, the British began passing laws that were difficult for the Afrikaner population, including laws that led to their losing property and slaves. In response, large groups of Dutch descendants left Cape Colony in the 1830s and 1840s to establish homesteads elsewhere in the country. As much as one-tenth of the white population left Cape Town during this period of animosity toward the English. Thompson, History of South Africa, 31–69.

[51] The Xhosa Wars, also known as Kaffir Wars, were a series of skirmishes between the native African Xhosa people and Europeans beginning in 1778. Now considered offensive, “Kaffir” was a term referring to blacks, especially Xhosa or other native tribes. Both Dutch and British farmers and colonists tried to force the Xhosa off their land, and the Xhosa retaliated to retain it. Eight Xhosa Wars had already occurred when Haven and his companions arrived, with one more occurring in 1877–78. Timothy J. Stapleton, “Cape-Xhosa Wars,” in Encyclopedia of African Colonial Conflicts, 1:170–77; Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “Kaffir.”

[52] The ship Unity was built in England in 1848. Three Latter-day Saints at Port Elizabeth purchased the ship, and Elders Leonard Smith and William Walker, as well as fifteen emigrating Saints, left aboard the ship on November 28, 1855. Jesse Haven left by himself on December 15 on the ship Cleopatra. Buckley, “‘Good News’ at the Cape of Good Hope,” 486; Sonne, Ships, Saints, and Mariners, 49, 193.

[53] The Perpetual Emigrating Fund originated in fall 1849. It was an organization to help emigrating Saints, as the principle of “gathering” meant that foreign converts were expected to move to the Great Basin. Those who were helped were expected to give back to the fund once they arrived in the Salt Lake Valley, but many of them never did. Fred E. Woods, “Perpetual Emigrating Fund,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 910; Carson, “Perpetual Emigrating Fund”; Howard, “Economic Analysis of the Perpetual Emigrating Fund.”

[54] Edward Slaughter (1807–97) was born in England and later moved to South Africa. After being baptized by Leonard I. Smith, he made his way to Utah and later served a mission to Britain in the 1880s. Early Mormon Missionaries database, s.v. “Edward Slaughter.”

[55] Richard Provis (1825–1907) traveled to Utah in 1860. Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel database, s.v. “Richard Samuel Provis.”

[56] Journal of Discourses was a semimonthly magazine published in Liverpool from 1853 to 1886. It featured speeches by church leaders in Utah, transcribed by George D. Watt, as well as other reports and forms of public discourse. Crawley, Descriptive Bibliography of the Mormon Church, 3:103–8.

[57] Devoting all of one’s property to the church is known in Latter-day Saint teachings as the law of consecration, and it has shifted in practice throughout the church’s history. From 1831 to 1834, the law of consecration was largely a communal endeavor designed to assist the poor and build up communities; living the law involved donating all of one’s money, lands, and goods to the church to be administered by the bishop, who would issue a portion (one’s “stewardship”) in return. Problems forced the system to be modified in 1833 and discontinued by 1834. Due to the struggles of the Saints after their expulsion from Missouri and their failure to keep the law of consecration, they were commanded in July 1838 to pay tithing of one-tenth of “their interest annually” (Doctrine and Covenants 119:4). Lyndon W. Cook, “Consecration, Law of,” and Dale Beecher, “Tithing,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 241–43, 1249–51; see also Harper, “All Things Are the Lord’s.”

[58] South Africa has considerably more than “three or four different languages.” In addition to the English and Dutch (Afrikaans) languages of European colonists, various African peoples speak (or spoke) numerous native languages, including Zulu, Xhosa, and Swazi. Creole languages based on Portuguese also emerged among Asian slaves. Mesthrie, “South Africa: A Sociolinguistic Overview,” 11–26; Thompson, History of South Africa, 52.

[59] This quote was attributed to Joseph Smith by Brigham Young, who wrote to Orson Spencer that “Joseph told [it to] the Twelve, the year before he died.” “Letter from President Brigham Young to Orson Spencer,” Millennial Star 10, no. 8 (April 15, 1848): 115.

[60] Jesse Haven, “Foreign Correspondence: Cape of Good Hope Mission,” Millennial Star 18, no. 20 (May 17, 1856): 318–19.

[61] Table Mountain is a peak south of Cape Town that stands about 3,500 feet above sea level. Merriam-Webster’s Geographical Dictionary, s.v. “Table Mountain.”

[62] When the Dutch colonized Cape Colony in the 1650s, they brought slavery with them. Slaves were imported from other areas in Africa and from southern Asia. In 1807, after England gained control of the cape, the British Parliament banned the slave trade, meaning no new slaves could be brought to British colonies, but slavery continued with those who were already in its clutches. The government enacted various laws to ameliorate the condition of slaves in South Africa until slavery was officially abolished in 1834. Freed slaves went through a state of “apprenticeship” until 1838. See Dooling, Slavery, Emancipation and Colonial Rule.

[63] Cape Malays are an ethnic group descended from slaves imported from Southeast Asia, and most of them are Muslims. The Koran permits polygamy, especially when it helps widows, but does not expressly encourage the practice. Modern Muslim Societies, 32–35.

[64] According to Muslim belief, prophets are sent by God to different peoples at different times, preaching the same message of the Koran. However, the message from the earlier prophets became corrupted. Muhammad was the last prophet because he preserved the Koran without corruption. Oxford Dictionary of World Religions, s.v. “Nabī,” 674.

[65] Haven had the first third of a pamphlet by Lorenzo Snow, The Voice of Joseph, translated into Dutch. He likely used the Liverpool 1852 edition. This part of The Voice of Joseph recounts Joseph Smith’s early visions, the publication of the Book of Mormon, and the organization of the Church. Whittaker, “Early Mormon Imprints in South Africa,” 407; Crawley, Descriptive Bibliography of the Mormon Church, 2:369–70, 3:221–22.

[66] Genesis 16 recounts the story of Abraham and Hagar. Hagar was the handmaid of Abraham’s wife, Sarah, and Sarah gave her to Abraham since she was barren. Hagar bore a son, Ishmael, to Abraham, but it was Sarah’s son, Isaac, who would be heir to the Abrahamic covenant described in Genesis 17. Muslim tradition holds that Ishmael is the ancestor of certain Arabian tribes. Oxford Dictionary of World Religions, s.v. “Ishmael,” 478–79.

[67] Wine production also declined after a preferential tariff on wine exports ended in 1826. Thompson, History of South Africa, 53.

[68] Beginning in the 1820s, blue gum trees, Eucalyptus globulus, were brought to South Africa from Australia. They grow well in Africa because of the similar climate, but the timber is inferior, and as a nonnative species, they can damage the environment. Bennett and Kruger, Forestry and Water Conservation in South Africa, 27–36.

[69] Jesse Haven, “Foreign Correspondence: Cape of Good Hope Mission,” Millennial Star 18, no. 23 (June 7, 1856): 366–67.

[70] Jeremiah 16:16.

[71] By “Kaffirs,” Haven is probably referring to the native Xhosa people, a group of mixed farmers who herded cattle and raised crops. See Thompson, History of South Africa, 1–30.

[72] The assegai is a long, throwable spear used by African tribes. Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “assagai | assegai.”

[73] The Fingo, or Mfengu, people are traditionally considered to be a native group of people who fled from conquering Zulu tribes in the early nineteenth century and joined the Gcaleka group of the Xhosa. The Xhosa enslaved them, and the Fingoes allied themselves with the British and became liberated in the 1830s. Some scholars reject this account as a colonial fabrication and think the Mfengu are actually Xhosa captives. See Stapleton, “Oral Evidence in a Pseudo-Ethnicity,” 359–68.

[74] Christian missionaries began preaching among the Xhosa in the late 1790s and more permanently beginning in 1816. Missionaries often used native traditions to share their message, and the Xhosa likewise appropriated Christian ideas into their culture; at the same time, however, missionaries tried to quash local traditions they regarded as immoral. Hodgson, “Battle for Sacred Power,” 68–88.

[75] The Khoikhoi, originally called Hottentots by the Dutch, are a pastoral people of southern Africa. The term “Hottentot” is now considered offensive. Thompson, History of South Africa, 7; Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “Hottentot.”

[76] See chapter 2, note XX, p. XXX herein <<“Nineteenth-century Protestant whites”>>.