Introduction

Reid L. Neilson and R. Mark Melville, "Introduction," in The Saints Abroad: Missionaries Who Answered Brigham Young's 1852 Call to the Nations of the World, ed. Reid L. Neilson and R. Mark Melville (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), xix–xxvii.

When most scholars of religion in North America and historians of the American West envision The Church of Jesus of Latter-day Saints in the mid-nineteenth century, they conjure up images of a martyred Joseph Smith buried in Nauvoo, Illinois, and his prophetic successor, Brigham Young, leading the beleaguered vanguard company of Latter-day Saint pioneers to the Great Salt Lake Valley by ox-drawn wagons. The Mormon Exodus, ultimately numbering about seventy thousand pioneers over two decades, has become an American epic of biblical proportions. But by 1852, just five years after the “American Moses” and his fellow Latter-day Saints had begun settling the valleys of the Intermountain West, the global distribution of members of the church of Jesus Christ was much more European than American.

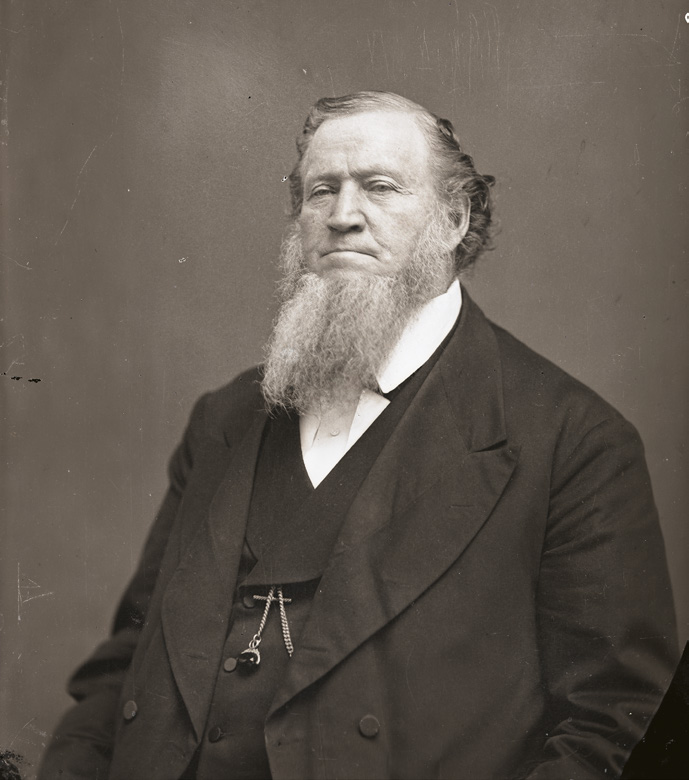

Portrait of Brigham Young. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Portrait of Brigham Young. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Beginning in 1837, Latter-day Saint missionaries evangelized in England and the surrounding countries, where they enjoyed tremendous conversion results. Smith later charged members of the Quorum of the Twelve in Nauvoo, Illinois, the year before his martyrdom, “Don’t let a single corner of the earth go without a mission.”[1] Before his death, he had called a handful of elders to evangelize in the nations of Australia, India, South America, Germany, Russia, Jamaica, and Tahiti; some fulfilled their missions, while others did not. It would be Smith’s successor and his fellow apostles who largely expanded missionary work beyond the British Isles. They were responsible for personally leading the Latter-day Saint errand to the world over the ensuing decades. Between 1849 and 1851, Young assigned church leaders and laity to preach in Italy, France, Scandinavia, the Sandwich Islands, and Chile for the first time. “While most of these initial attempts had limited success, they do reveal that Brigham Young and his associates took very seriously the scriptural injunction to carry the gospel” to all the world, argues historian David J. Whittaker.[2]

By the end of 1852, just fifteen years after the first Latter-day Saint apostles traveled to England, the 50,000-member American sect had evolved into a largely British religious tradition. Its center of gravity, although not its headquarters, had shifted across the Atlantic Ocean to the potteries and industrial centers of the United Kingdom. That year there were at least 10,000 Latter-day Saints in the Utah Territory, 1,000 in eastern North America, and 900 in the California Mission. In contrast, there were three times as many Mormons in Europe: about 32,500 in the British Mission, 1,100 in the Scandinavian Mission, 60 in the German Mission, 300 in the French Mission, and 200 in the Italian Mission. (Additionally, there were 950 in the Sandwich Islands Mission [Hawaii], 1,500 in the Society Islands Mission [Tahiti], 70 in the Australia Mission, and some converts in the East India Mission.)[3]

The church’s shift into a transnational spiritual movement further accelerated in the summer of 1852 in dramatic fashion. Young and his counselors in the First Presidency planned a special missionary conference in the newly constructed adobe Salt Lake Tabernacle on the temple block. Over the weekend of August 28–29, church leaders made two landmark announcements over the pioneer pulpit: a flurry of global mission assignments and a spirited defense of plural marriage.

Church leaders strategically held their conference in the summer heat, rather than the customary October timing, to help the newly called missionaries travel over the mountain passes to the west and east before the winter snows. “We have come together to day,” President Heber C. Kimball explained to the gathered Latter-day Saints that Saturday morning, “to hold a special conference to transact business, a month earlier than usual, inasmuch as there are elders to be selected to go to the nations of the earth, and they want an earlier start than formerly. There will probably be elders chosen to go to the four quarters of the globe to transact business, preach the Gospel, &c.”[4] During the Saturday afternoon session, the First Presidency assigned one hundred Mormon men to proselytize in distant lands, the largest cohort of full-time elders in the church’s three-decade history, as documented in the special conference meeting minutes featured in appendix 1.[5] Men (and their wives and children) were surprised to learn that they had been called to preach in the distant lands of Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Pacific Isles, as documented in the missionary register found in appendix 2. “That was the way things happened in Utah. You could be an ordinary man,” historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich explains, “then, all of a sudden, you were sent off to save the world.”[6]

On Sunday morning, August 29, Apostle Orson Pratt publicly acknowledged and defended the church’s practice of polygamy for the first time. It had been instituted by Joseph Smith more than a decade earlier and was conducted with increasing openness by Latter-day Saint patriarchs in the intervening years.[7] Though polygamy was no secret to the nation, the church’s open admission helped ratchet up tension that would lead to conflict with the United States government for more than fifty years. “From then on, Church leaders publically endorsed the practice as a fundamental, even defining, aspect of Mormonism and integrated the practice into a broader vision of Mormon political philosophy,” historian Christine Talbot argues. “The open practice of plural marriage added new dimensions to Mormon doctrine that, combined with earlier controversies, produced an insurmountable distance between Mormon and white middle-class Protestant Americans.”[8] The doctrine’s public promulgation would also present long-term challenges to Latter-day Saint elders called to preach during the second half of the nineteenth century—a painful theme that emerges often in their personal letters and subsequent narratives.[9]

These missionary assignments came at a tenuous time, while the pioneers were still literally trying not to starve to death in their desolate Great Basin kingdom.[10] Limited financial and human resources, coupled with competing institutional projects, forced church leaders to make heart-wrenching decisions. How to fulfill their divine mandate to “build Zion” at home and to “warn the nations” abroad, while at the same time meeting the temporal and spiritual needs of the Saints and the entire human family across time and space, weighed heavily on the hearts of Latter-day Saint authorities settled in the Great Salt Lake Valley.

Literary scholar Terryl L. Givens, in his history of church culture, argues that Latter-day Saints may be best understood historically as a paradoxical people. “A field of tension seems a particularly apt way to characterize Mormon thought,” he explains. “Mormonism, a system in which Joseph Smith collapsed sacred distance to bring a whole series of opposites into radical juxtaposition, seems especially rife with paradox—or tensions that only appear to be logical contradictions.” Givens insightfully frames his cultural study around four of the most prominent of these pairs: authoritarianism versus individualism, certainty versus learning, sacred versus quotidian, and exile versus integration.[11] His resulting study is illuminating and demonstrates how these ongoing oppositions have helped shape Latter-day Saint culture since the antebellum age in America.

As we have immersed ourselves intellectually into the nineteenth-century world of the church of Jesus Christ, we have come to appreciate that there were at least two additional paradoxes pressing on the minds of Latter-day Saint leaders and laity during the first decade of pioneering in Utah. As Reid L. Neilson and Nathan N. Waite document in their companion volume to this book, there was an ongoing tension between the prophetic priorities to settle the valley in Utah and simultaneously proclaim the gospel abroad during this pioneer era.[12] “Missionaries were expanding the work worldwide, opening one new land after another, although long-term efforts were gradually focusing on a few fruitful countries,” cartographer Brandon Plewe similarly describes this paradox. On the other hand, groups of Latter-day Saints increasingly immigrated to relatively isolated Utah Territory. “These competing efforts would continue throughout the rest of the nineteenth century.”[13]

Brigham Young and his fellow church leaders struggled to find the proper balance between their church’s competing (and complementary) colonization and evangelization programs. Prioritizing temporal and spiritual imperatives with limited human and financial resources required the wisdom of biblical Solomon. Any adult men they assigned to help settle the villages springing up throughout the Intermountain West meant fewer male missionaries they could send abroad to teach and gather new converts to Zion. The Latter-day Saints considered anyone who had not received baptism under proper priesthood authority, at home or abroad, among those needing salvation. Young’s calling of over one hundred men in August 1852 to cross geographical space across the globe to win converts exemplifies this missionary impulse. Ideally, their converts would then gather with their families to Zion, bringing with them the means to help colonize in Utah and aid their fellow pioneer Saints. These new immigrants could later serve as missionaries themselves, often to their former homelands, and convert others, ensuring that there was always a growing number of settlers at home and missionaries abroad.

An additional tension that emerges during this frontier era was the church leadership’s wrestle with eschatological time and evangelistic priorities. To whom should they first offer the message and ordinances of salvation in the last days: the living or the dead? This was not a question that their fellow Christians were asking themselves. Despite the Apostle Paul’s reference to his fellow Saints “who are baptized for the dead” (1 Corinthians 15:29; see also Doctrine and Covenants 128), the Latter-day Saints became the first (and only) Christians in the modern age to institutionally shoulder the divine responsibility to redeem the entire human family.[14] For believers, it was not “salvation of the living” or “salvation of the dead” but both. The only question was timing.

Church members felt compelled theologically to cross earthly time and this mortal sphere, which added an additional dimension to their already complicated evangelistic outreach. Smith first taught this distinctive Latter-day Saint doctrine in August 1840, while preaching at a public funeral in Nauvoo, Illinois. According to Smith’s dictated revelations, all of God’s earthly offspring—alive or dead—would be held to the same standards and be given equal opportunities to learn the commandments and accept the priesthood ordinances required for salvation in the mortal or postmortal life, prior to the Final Judgment and Resurrection. Months later the Prophet of the church of Jesus Christ reasoned, “If we can, by the authority of the Priesthood of the Son of God, baptize a man in the name of the Father, of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost, for the remission of sins, it is just as much our privilege to act as an agent, and be baptized for the remission of sins for and in behalf of our dead kindred, who have not heard the Gospel, or the fullness of it.”[15] Early Latter-day Saints rejoiced at this expansive theology, which permitted them to redeem vicariously their kindred dead. Since the Nauvoo period, Latter-day Saints have not struggled theologically with the destiny of the unevangelized, unlike their fellow Christians.

Christen Dalsgaard, Mormons Visit a Country Carpenter. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Christen Dalsgaard, Mormons Visit a Country Carpenter. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

While the living could participate in these salvific ordinances for themselves, the dead would have to depend upon the living to act as proxy for them in the same ordinances. Moreover, all ordinances for the salvation of the dead would have to be performed in Latter-day Saint temples, consecrated for that very purpose, the prophet taught. Latter-day Saints constructed a specially made font in the Nauvoo Temple’s basement to perform proxy baptisms for the dead, to aid in their work for the salvation of the dead. This doctrinal innovation has proven to be both a blessing and a burden for believers. Latter-day Saints are expected to become “saviors on Mount Zion” for their ancestors reaching back to the original family in Eden during their mortal or millennial estate.[16]

This redemptive work for the dead was resumed in Utah during the same years that the “missionaries of 1852” went out to the nations of the world. Just as they had embraced the opportunity to baptize their kindred dead in the Nauvoo Temple, the Latter-day Saints in Utah regularly participated in proxy baptisms for their deceased loved ones. Brigham Young and the First Presidency desperately needed more people to build another temple in the West, but on this August occasion, they prioritized the competing value of missionary work for the living. But living and breathing converts from Europe, Asia, and Africa promised to be future participants in the work for the salvation of the dead, just as they would help build Zion in Utah upon their arrival. It proved to be a virtuous cycle in the future, to be sure, but it was one fraught with tension in the present moment.

Within two months of the August 1852 conference, nearly all the missionaries embarked for their respective fields of labor. Unable to highlight their hundred plus individual stories, we have relied upon the autobiographical writings of eight men to illuminate their shared and disparate experiences, including how the news of polygamy impacted their proselytizing. In part 1, “Evangelizing in the Atlantic World,” we focus on the narratives of Dan Jones and the Wales Mission, Orson Spencer and the Prussia Mission, Edward Stevenson and the Gibraltar Mission, and Jesse Haven and the Cape of Good Hope Mission. Part 2 tells the story of “Evangelizing in the Pacific World,” through the records of Benjamin Johnson and the Sandwich Islands Mission, James Lewis and the China Mission, Chauncey West and the Siam and Hindoostan Missions, and Augustus Farnham and the Australia Mission.

This volume brings to the forefront the paradoxes and challenges Latter-day Saint leaders faced during the early 1850s, as they sought to both settle the valley and proclaim the gospel, as well provide salvation for the living as well as for the dead. While chronicling the first century of the restored church of Jesus Christ in 1930, Assistant Church Historian Brigham H. Roberts made an audacious declaration about the missionaries called in August 1852: “Thus did the Church of the Latter-day Saints in these years . . . seek to fulfill the initial obligation given to that church in the very opening of the New Dispensation, namely, to preach the gospel of the kingdom to every nation, and kindred, and tongue, and people.” He continued his claim with one long laudatory sentence, which begs contemplation (and challenge) by anyone studying nineteenth-century Christian missiology in America:

And if the numerical and financial strength of the church be taken into account, or rather its weakness in these respects be taken into account, and if the circumstance of the location of the saints in an undeveloped and comparatively isolated country in the mountain interior of America be also considered, the splendor of this missionary spirit, and the wonder of the journeys of these missionaries to such distant lands, and their achievements in the face of all the hardships and hindrances to be endured and overcome—if all this be considered, it will render these missionary enterprises the most wonderful manifestations of Christian zeal and enthusiasm—the largest and most earnest service undertaken, within the same space of time, for God and man, since the days of the apostles of the early Christian church.[17]

Notes

[1] Smith, History, vol. D-1, 1539; Smith, journal, April 19, 1843, in Hedges et al., Joseph Smith Papers, Journals, Volume 2, 370.

[2] See Whittaker, “Brigham Young and the Missionary Enterprise,” 90–91; see also Neilson and Waite, Settling the Valley, Proclaiming the Gospel, 114.

[3] Plewe, “State of the Church in 1852,” 234–36.

[4] Church leaders also held their regular fall general conference meetings on October 6–8, 1852. See “Minutes of the General Conference . . . ,” Deseret News, October 16, 1852.

[5] Minutes of Conference was initially published as a Deseret News extra in Salt Lake City, Utah, September 14, 1852. See appendix 1, XXX–XXX herein. Ten days earlier, the first newspaper mention of the historic gathering was printed: “The Special Conference,” Deseret News, September 4, 1852. The initial “extra” was republished in a regular newspaper edition as “Minutes of Conference,” Deseret News, September 18, 1852, about three weeks after the event.

[6] Ulrich, House Full of Females, 239.

[7] Crawley, Descriptive Bibliography of the Mormon Church, 2:354–57. See Whittaker, “Bone in the Throat,” 293–314; Daynes, More Wives Than One; and Gordon, Mormon Question, 22–23.

[8] Talbot, Foreign Kingdom, 33.

[9] In addition to the narratives featured in this volume, see Ulrich, House Full of Females, chapter 10.

[10] Neilson and Waite, Settling the Valley, Proclaiming the Gospel, 11–13.

[11] Givens, People of Paradox, xiii–xvii.

[12] Neilson and Waite, Settling the Valley, Proclaiming the Gospel, 1–31.

[13] Plewe, “State of the Church in 1852,” 243.

[14] See Paulsen, Cook, and Mason, “Theological Underpinnings of Baptism for the Dead,” 101–16.

[15] Smith, History, vol. C-1, 61.

[16] After Smith’s murder, Young performed the final ordinance work in the Nauvoo Temple on February 8, 1846, just as the Latter-day Saints began their Exodus to the American West. On July 28, 1847, days after he arrived in the Great Salt Lake Valley, he marked the location for a new temple where they could resume their work for the salvation of the living and the dead. The Salt Lake Temple, begun in April 1853, took four decades to complete before it was dedicated in April 1893. In the meantime, Latter-day Saint leaders performed temple ordinances in the public Council House (1851–55) and the private Endowment House (1855–89), both located in downtown Salt Lake City, a stone’s throw from the temple building site. LaMar C. Berrett, “Endowment Houses,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 2:456.

[17] Roberts, Comprehensive History of the Church, 4:75–76.