Edward Stevenson and the Gibraltar Mission

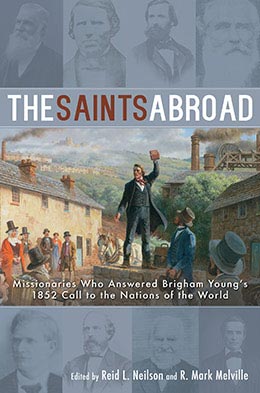

Reid L. Neilson and R. Mark Melville, "Edward Stevenson and the Gibraltar Mission," in The Saints Abroad: Missionaries Who Answered Brigham Young's 1852 Call to the Nations of the World, ed. Reid L. Neilson and R. Mark Melville (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 69–106.

Historical Introduction

In January 1885, the Juvenile Instructor magazine ran a short cover story on the history of Gibraltar, known as “the Rock,” the British overseas territory located on the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula bordering Spain. The editor, George Q. Cannon, wrote, “When Elders Edward Stevenson and N[athan] T. Porter arrived in Gibraltar in March, 1853, to preach ‘Mormonism,’ they were immediately taken before the police to plead their cause. Elder Porter was required to leave and the only thing which saved Elder Stevenson from sharing the same fate was the fact that he had been born on the rock; still he was forbidden to preach his religion. He, however, during his labors of one year, and amid great privations and trials, succeeded in bringing several persons into the Church.”[1]

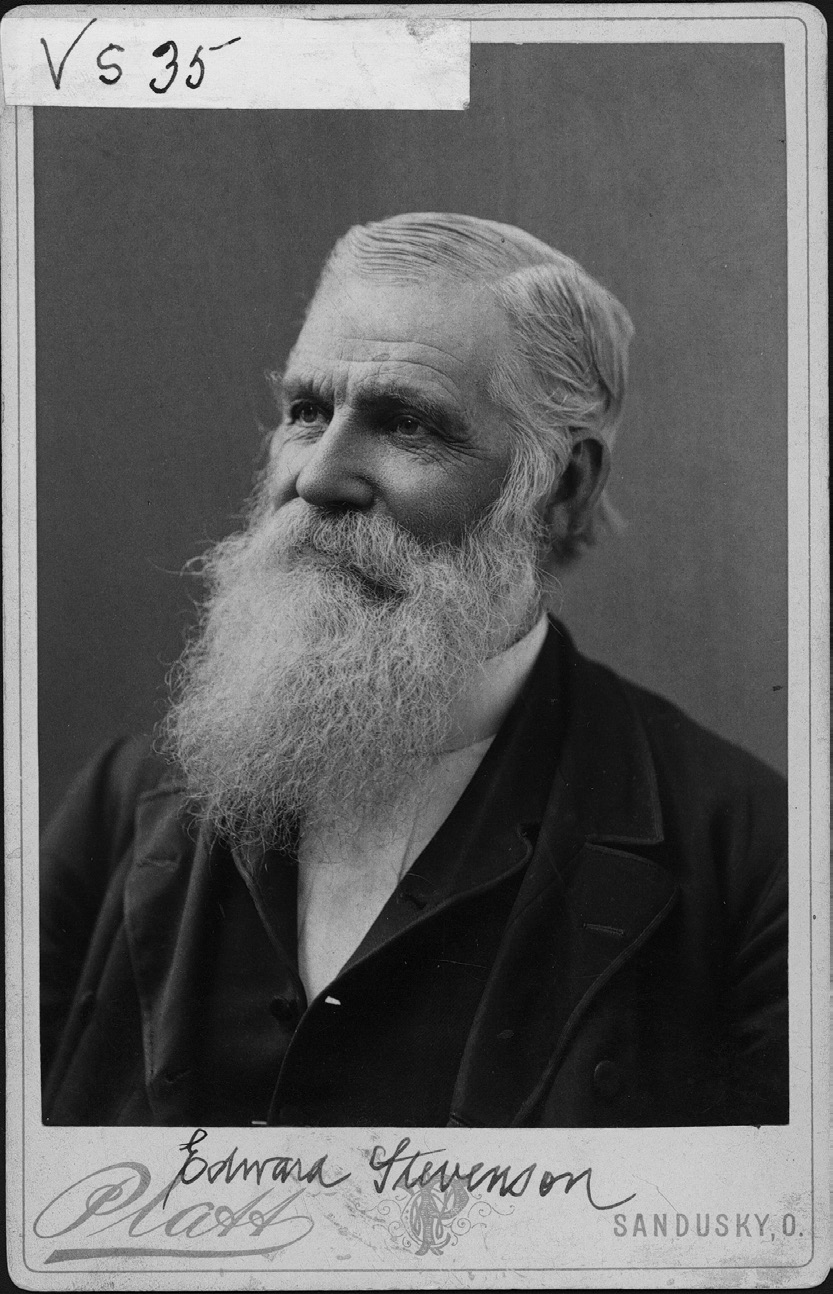

Edward Stevenson. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Edward Stevenson. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Another article on Gibraltar or even a mention in the future pages of the Juvenile Instructor would have been highly unlikely had the cover story not caught the eye of Stevenson, by then sixty-four years old and living in northern Utah. Desiring that his fellow Latter-day Saints in the Intermountain West might better appreciate the secular history of his British homeland, Stevenson drafted a seven-letter secular history of the Rock, which ran for months in the Mormon magazine.[2] Beginning with his eighth letter, Stevenson’s ten subsequent missives (for a total of seventeen letters to the Juvenile Instructor) chronicle his “missionary experience”[3] as a young elder in Gibraltar in 1853 and 1854. Stevenson narrates his mission to Gibraltar with great passion and some prejudice: the Latter-day Saints, whom he sees as righteous, are constantly trying to build Zion at home and abroad, while the Protestants and Catholics he encounters, whom he sees as less than righteous, are trying to thwart their progress at every turn. His story is filled with black and white characters and organizations—there is little gray in his reminiscent account—like the memoirs left by so many Latter-day Saint missionaries during the nineteenth century. Still, Stevenson’s detailed account of his experiences in Gibraltar is significant because he was one of only two Latter-day Saints to ever proselytize and temporarily establish the church on the Rock during the first 140 years of the church’s history.

Stevenson and Porter’s Early Years, 1820–48

Stevenson was uniquely suited by nativity to serve as a missionary in the British colony of Gibraltar. As later experiences made clear, only a native Gibraltarian would be allowed to proselytize on the Rock in the mid-nineteenth century. Stevenson was born on May 1, 1820, in Gibraltar, the fourth son of Joseph Stevenson and Elizabeth Stevens. In 1827, at the tender age of seven, he immigrated with his family to the United States, settling first in New York and then in Michigan. In 1831 his father passed away, leaving him in the care of his mother and siblings. In 1833, three years after The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was organized in upstate New York, missionaries Jared Carter and Joseph Woods evangelized in Michigan. Although still a young man, Stevenson believed their words and embraced their teachings. He was baptized on December 20, 1833, and his mother and several siblings also joined the church. As a family they gathered with the Latter-day Saints in Missouri and endured the trials that followed the church and its members across that state. While living in Far West, Stevenson became more acquainted with Joseph Smith, having first met him while living in Michigan. Stevenson was eventually exiled from Missouri with the body of the church and moved to the temporary safety of Nauvoo, Illinois. There he married his first wife, Nancy A. Porter (the sister of his future missionary companion Nathan T. Porter), in 1845 and was endowed in the Nauvoo Temple in 1846. He crossed the plains in the Charles C. Rich company in 1847, his first of nearly twenty crossings over the plains on behalf of the church as a leader and missionary.[4]

Stevenson’s brother-in-law, Nathan Tanner Porter, was born on July 10, 1820, in Corinth, Vermont, to Sanford and Nancy Porter. A decade later, Lyman Wight and John Corrill preached to the Porter family in Illinois, and they were baptized in August 1831. The Porters joined the main body of Saints, first moving to Independence, Missouri, in 1832 and then to Nauvoo, Illinois, in 1839. Porter was called on missions to the eastern states in 1841 and 1844, but he returned early from his 1844 mission because of the martyrdom of Joseph and Hyrum Smith. In 1847, the Sanford Porter family left Nauvoo and arrived in the Salt Lake Valley that October. Nathan married Rebecca Ann Cherry on November 12, 1848. He was called to accompany Stevenson to Gibraltar in 1852.[5]

Precursor to Mormonism in Gibraltar

Latter-day Saint evangelism in the Mediterranean world began several years before church leaders assigned Edward Stevenson and Nathan T. Porter to Gibraltar in August 1852. Apostle Lorenzo Snow and his companions arrived in Italy in June 1850 to begin proselytizing. Struggling to find a foothold in Italy, Lorenzo Snow determined to expand his Italian Mission into the larger Mediterranean world and even into British India to the east. In 1851, he called William Willes and Hugh Findlay to India,[6] and Thomas Lorenzo Obray to Malta.[7] In the spring of 1852, Lorenzo Snow was called back to church headquarters in Utah along with the other Apostles evangelizing in Europe. Before he left, however, he expressed his hope that missionary work might spread to the Iberian Peninsula. That May, Snow issued a call from the mission headquarters in Malta for elders to begin proselytizing work in Gibraltar. Sharing his desires with President Samuel W. Richards of the British Mission, he explained: “The English and Italian languages are much spoken at Gibraltar as well as the Spanish, and we are anxious to see the kingdom of God beginning to spread its light if possible through the Spanish dominions, and feel to do all in our power to effect so desirable an object. We cannot help but believe that the Lord has some good people in that place.” Snow himself was apparently planning to visit Gibraltar to observe conditions firsthand.[8] “In a few days I will have completed my arrangements here and shall then, the Lord willing, take my departure for that country, and spend there what little time yet remains at my control, with a view of making an opening as wisdom may direct.” The Apostle then asked for a “wise, energetic, faithful, and experienced Elder” to begin proselytizing on the Rock, as well as additional missionaries for Bombay, India.[9]

Samuel Richards published Snow’s letter in his mission’s periodical, the Millennial Star, and added his own letter of endorsement to open the Rock to missionary work. “The letter of Elder Lorenzo Snow, published in the last Number of the Star, contains an important call for Elders, to assist in moving on the work in Gibraltar and Bombay, to which we cheerfully respond, and hope the Presidents of Conferences will report to us, without delay, such Elders as they may be acquainted with, who are suitably qualified for those important stations.” Richards suggested that single elders or those married men who “can provide for their families” would be excellent choices. “An Elder with some knowledge of the French, Spanish, and Italian languages, would be peculiarly adapted to fill the call for Gibraltar.”[10] With his three-year mission complete, Snow departed from Malta and the Italian Mission, stopping over in Gibraltar for several days on his way to Liverpool, England. After crossing the Atlantic to New York City, he arrived in Salt Lake City on July 30, 1852.[11] One month later, Snow’s hopes of opening Gibraltar to missionary work and sending more elders to India were realized when the First Presidency called a special missionary conference in Salt Lake City. Edward Stevenson and Nathan Porter, the only two men assigned to Gibraltar, were as stunned at their assignment as the other newly called missionaries were at theirs.

Stevenson’s Experience in Gibraltar, 1852–55

Stevenson and Porter departed from Utah in September 1852 and traveled through St. Louis, New York City, and Liverpool before reaching their destination. When Stevenson and Porter arrived at Gibraltar on March 8, 1853, they followed a newfound friend, Mr. Willis, into the garrison. The colony was very strict on allowing visitors, but since Willis was a Gibraltarian resident, the guards did not question Stevenson and Porter upon their entry. One of their first tasks was to climb the Rock of Gibraltar, where they “erected an altar of loose stone and dedicated ourselves and the mission unto the Lord.” Days later, they visited Stewart Henry Paget, the police magistrate, who was amazed that they had made it into the port without identification. He told them, “You [Stevenson] will be allowed, as native born to remain on the rock, but if caught preaching will be made a prisoner immediately. And you, Mr. Porter, by this permit will be allowed to remain fifteen days; your permit will not be renewed, and if you preach you will be cast outside our gates.”[12] True to local official’s words, Porter was shipped out of Gibraltar on April 1, leaving Stevenson to spread his message by himself.[13]

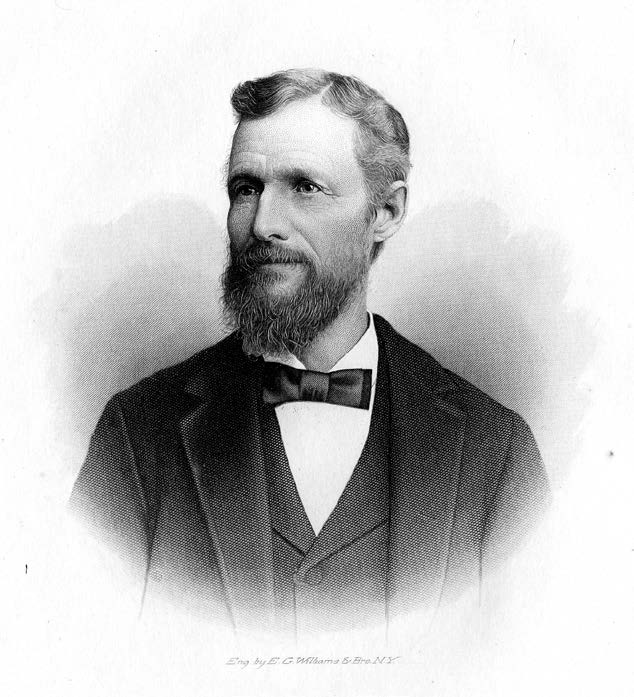

Portrait of Nathan Porter. Courtesy of Church History Library

Portrait of Nathan Porter. Courtesy of Church History Library

Stevenson faced considerable opposition from clergy and government officers. On one occasion, an officer who happened to be Methodist put him “under guard, saying that my religion was one that could not be tolerated in that place. For the first time in my life I was marched into the guard house a prisoner.” Stevenson was soon released after explaining what he had been doing.[14] Stevenson’s theology included heavenly vengeance against those who opposed the Latter-day work. He met a man who said that “Joe Smith was served just right and ought to have been killed long before he was.” The next day, this man “began vomiting blood, and before he could be carried to the hospital he was dead. . . . Thus did the judgment of God speedily follow him.”[15] Stevenson also met some people he had known from his youth in Gibraltar. One Mr. Smith, a Methodist friend of his father, wanted him to preach in their local church, but he rescinded his enthusiasm upon learning he was a Latter-day Saint. Smith’s family began reading the Book of Mormon, but Smith opposed the church. Like the man who vilified Joseph Smith, “the poor man was very soon again confined to his bed, but not long this time, for he soon died.”[16] Another family friend, Mr. Gilchrist, regarded the church as an “imposture,” but he offered to help Stevenson with fifty cents, which Stevenson declined.[17] Despite the antagonism of many of the Gibraltarians, he managed to baptize several converts, and on January 23, 1854, he organized the Rock Port Branch of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[18] Not all family friends opposed Stevenson and his doctrines as Mr. Smith and Mr. Gilchrist had done; Stevenson baptized a woman who had dandled him on her knee when he was a child.[19] In May 1854, however, several of his new converts, members of the British military, were sent away to Eastern Europe to fight in the Crimean War.[20] “A solemn reflection crossed my mind,” Stevenson recorded, “who of this one thousand will ever return home again to fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters or wives?”[21] One of these converts, John McLean, preached his new faith to fellow soldiers and established the Expeditionary Force Branch of the church.[22]

Stevenson was discouraged when these members left Gibraltar, “thus depleting [his] hard earned little branch.”[23] Two weeks later, Stevenson recorded his frustration and expressed his wish for divine punishment on Gibraltar: “There is no chance in this garrison under those adulterers <authorities> without permission from the colonial secretary of foreign affairs so I shall soon leave them to their own distruction for it is bound to come on this place. . . . This place neads a scourge to soften the hearts of the rulers & people & I feel to say in the name of the Lord Wo Wo Wo be unto this city.”[24] Sometime between May 1854 and April 1855, Stevenson left Gibraltar for England. He oversaw a group of Saints departing from Liverpool aboard the ship Chimborazo, aided by Elders Andrew Lamoreaux and Thomas Jeremy, who were also returning from their 1852 missions.[25] Stevenson arrived home in Utah in September 1855.[26]

Additional Church Service, 1855–97

Stevenson’s proselytizing efforts in his native Gibraltar mark just the beginning of his remarkable missionary legacy for the church. After Gibraltar, Stevenson served nine additional proselytizing missions in North America and Europe and helped lead four emigrating companies from the East to Utah. He was also responsible for bringing Book of Mormon witness Martin Harris to Utah and for encouraging his rebaptism in September 1870. Three years after he detailed his missionary experiences in Gibraltar to George Q. Cannon and the readers of the Juvenile Instructor in 1885, he joined Andrew Jenson and Joseph S. Black on a special church history mission to visit many of the early historic sites of the Restoration.[27] In October 1894, Stevenson was called to serve as one of the first seven presidents of seventies,[28] a position he honorably fulfilled until his passing on January 27, 1897, in Salt Lake City, Utah. He never did return to his birthplace in Gibraltar following the close of his mission in 1855.[29]

Nathan Porter also continued to serve in the church. After being forced out of Gibraltar in 1853, he labored in England until January 1856. While returning to Utah, he traveled with the Hodgetts company, a wagon company that somewhat shepherded the ill-fated Martin handcart company, and they arrived in Salt Lake City in December 1856. He married his second wife, Eliza Ford, in 1857. Nathan Porter and Edward Stevenson were mission companions two more times, in 1869 and 1872, when they traveled to the eastern states. Both Stevenson and Porter were born in 1820, and they both died in 1897 (Stevenson died January 27 and Porter died April 9, 1897).[30]

Edward Stevenson’s Family Life

Edward Stevenson married Nancy Areta Porter on April 7, 1845, in Nauvoo, Illinois, and they were sealed in the Nauvoo Temple the following year. When Stevenson left on his mission in 1852, they had four children, ages six and younger.[31] His mother, Elizabeth Stevens Stevenson, moved in with Nancy during his absence, and Stevenson made preparations for his family financially: “I have rented my set of tin tools & shop to Brother Whitehouse for one third of the prophits & the adjoining room for 18 dollers for the year as the man is poor for I was offered 36 dollers the same day for the same room for the same time this with 36 dollers for the other building & the rent of my 5 acre lot will help take care of my familey. I leave them with plenty of provisions for this year and 25 dollars cash so this is grattifying to me to think of though deprived of each other’s society & I feel as though they will be blest in my absence.”[32] Stevenson was heartbroken when he learned that their infant daughter died while he was away from home: “Rec[eive]d a letter this day from home anounceing the death of my youngest daughter Nancy Elizabeth Stevenson who departed May 5, which takes me rather on surprise haveing recd a letter last month dated Apr. 29th & that stated all well and little Nancy E. was then about 9 months old & could nearly run alone. But, oh, the sudden change the Monster Death can make in only 8 days.”[33]

After his Gibraltar mission, Stevenson married three additional wives: Elizabeth DuFresne in 1855, Emily Williams in 1857, and Louisa Yates in 1872. He had another child with Nancy, eight children with Elizabeth, eleven with Emily, and three with Louisa. Practicing polygamy came with substantial challenges: Nancy divorced him in 1869, and Stevenson had to hide from federal prosecution of polygamists during the 1880s, just as many others did.[34]

Source Note

Edward Stevenson wrote the featured seventeen letters to George Q. Cannon, editor of the Juvenile Instructor, in response to a short cover story on the history of Gibraltar, which ran in January 1885. The January article barely made mention of Stevenson’s missionary sojourn there in 1853–54, nearly thirty years earlier. Cannon published Stevenson’s detailed letters in his magazine over a nine-month period, beginning on February 15 and ending on November 15, 1885. Historians are reliant on Stevenson’s personal writings and his reminiscent accounts for the history of the Gibraltar mission field in the mid-1850s. Nathan Porter later wrote an autobiographical account of his life, but besides his account and what Stevenson personally recorded at the time, there are no corroborating accounts or documents. Stevenson did send a number of letters back to Utah during his early mission, and their contributions to our understanding of what he experienced as a young missionary in Gibraltar during 1853 and 1854 are noted below. It appears that Stevenson relied heavily on his 1850s writings (such as his letters, Deseret News correspondence, and regular diary entries) when he wrote his 1885 letters to Cannon.

Document Transcripts

Edward Stevenson to George Q. Cannon, June 1, 1885[35]

At a special conference held in Salt Lake City, August 28, 1852, I was called to take a mission to Gibraltar in company with Elder N[athan]. T. Porter. It was at this conference that the revelation on celestial marriage was first made public, and was taken to the world by the greatest number of Elders that had ever been called on missions at any one time before.

It was agreed that the company going east should meet on the Weber River, forty-five miles from the city, and we would proceed from that point across the plains together. Daniel Spencer was elected captain of the company; Orson Spencer, chaplain; and Orson Pratt, preacher and general instructor. Our company consisted of eighty-four Elders, who had twenty carriages and eighty-eight horses and mules.

In crossing over the Little Mountain our carriage was broken down, and we left our baggage there, covered up with a buffalo robe, while we returned to the city to have the vehicle repaired. After getting the necessary repairs done we again started, but on account of storms were compelled to camp out at the mouth of Emigration Canyon. The next day we arrived at our camp outfit on the Little Mountain just in time to save it from a band of roving Indians. That night we camped all alone on the Big Mountain and were disturbed in our slumbers by the howling of the wolves. We slept very well, however, after having commended ourselves to the care of the Lord.

On the 20th of September, 1852, the whole company began to move and on the 1st of October we arrived at the Missouri River in the best of health and spirits. Our evenings on the journey had been spent around the camp fire discussing religious subjects and often being instructed by Apostle O. Pratt.

Our company now began to scatter to go to their various fields of labor. I joined a company and took steamer for St. Louis. We were kindly treated on board. A discussion took place in the cabin between Elder O. Pratt and Mr. Storon, president of the Missouri College, resulting in a Bible triumph in favor of Apostle Pratt.

In St. Louis, Elder Wm. Pitt found himself without sufficient money for his passage to his field of labor and was walking down the street with his head bowed down, wondering what he should do to obtain the necessary means. Suddenly he saw before him, on the walk, a ten-dollar bill, the exact amount required. He picked it up and after searching in vain for the owner, used it for procuring his passage to England. On November 11th,[36] twenty-one of us, who had engaged passage to Liverpool on a sailing vessel of 1,800 tons burden, set sail, and arrived at our destination on January 5th, 1853.[37] We buried one passenger, a Catholic, in the open sea. He was sewed up in a blanket and some weights were attached to the feet. Burial services, in the absence of one of their priests, were read by Elder Perigreen Sessions,[38] and he was then slid off a plank into the blue waters of the ocean. The usual customhouse overlooking of our baggage took place at Liverpool. A French stranger was detected with a crust surrounding a quantity of tobacco, making it look like a loaf of bread. The experiment cost him $250.00.

While in New York our whole company were provided with passage and provisions with the exception of one Elder, who did not have sufficient money to buy food. A stranger came along and passed several of us, enquiring concerning our missions. But when he came to the only one not yet provided with his outfit, he dropped five dollars into his hand. With a tear of gratitude the stranger was blessed and God praised.

After visiting Prest. S. W. Richards at 15 Wilton Street, Liverpool, and my friends in Leicester, London, Southampton and the Isle of Wight, myself and companion took passage from Southampton on her majesty’s steam packet, Iberia,[39] on February 28th, 1853.[40] We had enjoyed many excellent and profitable meetings with the many churches in England, holding before them the new revelation on the eternity of marriage.[41]

On the morning of March 3rd we cast anchor in Vigo Bay, [42] Spain, after sailing 663 miles over the rough Bay of Biscay.[43] This is a lovely bay, abounding with a variety of fish. Its borders abound with oranges, figs, grapes and nuts. Sixty-eight miles more and we pass Oporto,[44] on the coast of Portugal. The next city was Lisbon,[45] the capital of Portugal. It lies two miles up the Tagus River,[46] and is very strongly fortified. The queen’s palace and garden are worthy of attention; the remainder of the city is very filthy. On March 6th we left Lisbon and cast anchor in Cadiz Bay, Spain.[47] We were now about 9,000 miles from our Utah home.

Edward Stevenson to George Q. Cannon, June 15, 1885[48]

On the morning of March 8th, 1853, we were anchored under Gibraltar and heard the morning gun fired as the signal for opening the gates of the fortress, raising the drawbridges, lowering rope ladders and opening up the garrison generally.

The picturesqueness of the rock and garrison from the waters of the bay, especially when illuminated, on a dark night was a grand scene. The houses of both the north and south towns are terraced one above the other on the rock.[49]

Small crafts soon placed us and our luggage on the rock. The guard was ordered to allow no one to pass the portals without proper credentials. One gentleman who was not prepared for this was turned away. My American passport[50] did not reach me at Liverpool as expected, and President Richards failed to influence the American consul and minister at London to supply the deficiency, and I was therefore in danger of being turned away. But strange to say, myself and companion passed into the garrison unchallenged, which afterwards surprised the officers.[51]

The Rock of Gibraltar. Courtesy of Pixabay.com.

The Rock of Gibraltar. Courtesy of Pixabay.com.

While passing along the narrow streets and sidewalks only paved with cobble stone, but scrupulously clean, and on seeing so many people of different nationalities, there being twelve different languages spoken by the people living here, we began to realize with what kind of a spirit we had to contend, and it produced peculiar emotions best known to those who feel the worth of souls and are placed in a strange land thousands of miles from home. It truly made us feel to put our trust in the Lord.

After getting something to eat we walked up to the summit of the rock and erected an altar of loose stone and dedicated ourselves and the mission unto the Lord, and we were comforted.[52] The scenery from this spot was sublime. Spain lies to the north; Morocco on the coast of Africa, fifteen miles to the south; the Mediterranean on the east, and the straits and bay on the west. It was dusk when we wound our way down the rock to the town and secured lodgings at the house of a Spanish lady whose husband was a convict keeper.

On the Sabbath we visited the Methodist[53] church and were introduced to Rev. Mr. George Alton.[54] Subsequently we made an effort to obtain the chapel for the purpose of holding meeting, but our request was denied. My father helped to build this chapel and myself and two sisters and a brother were baptized therein.[55]

While looking for a hall in which to hold meetings, we were informed that a permit from the governor was necessary before either an indoor or outdoor meeting was held. On the 14th, we therefore wrote to this individual and solicited the privilege, which was given other ministers to hold religious services. We were referred to Sir George Aderly [Adderley], colonial secretary.[56] With this person we had three interviews. While he was looking over Governor B[righam]. Young’s letter of commendation, he said he had read of Brigham Young and his thirty wives.[57] During our last interview we were informed by him that we would have to appear before Stewart Henry Paget,[58] police magistrate, and prove our right to remain on the rock. And he expressed surprise at our being able to pass the sentinels unchallenged, etc.[59]

We obtained from Mr. [Horatio J.] Sprague,[60] American consul, a permit to visit on the rock for fifteen days in favor of Elder Porter,[61] and I had a certificate of birth and baptism from the Methodist mission. But Mr. Alton was very reluctant to give a certificate to me now that I had become a “Mormon.” I had quite a long dispute with him on the principles of the gospel.

We then went to the court room and the magistrate, after looking at my certificate, said, “You will be allowed, as native born to remain on the rock, but if caught preaching will be made a prisoner immediately. And you, Mr. Porter, by this permit will be allowed to remain fifteen days; your permit will not be renewed, and if you preach you will be cast outside our gates.” We left some tracts in the police office and retired to our place of prayer on the top of the rock and offered our complaints to the Lord.[62]

We put out two hundred tracts in various parts of the garrison, and privately taught the people.

Edward Stevenson to George Q. Cannon, July 1, 1885[63]

The morning following our interview with the magistrate we took a walk out into Spain. We found the soil and climate producing oranges, figs, pomegranates, lemons, limes and a great variety of wild flowers; but the indolent Spaniards left nature to do most of the work. Many of them were living in huts similar to Indian wickeups. We could not but think that if Utah were favored with so good a climate and rich soil the huts would soon be supplanted by neat cottages and vineyards, and the land made almost like a paradise.

On our return to the lines we were told to call at the magistrate’s office. We did so and were informed that the governor had given our letter to him (the magistrate) and that we need expect no aid in spreading “Mormonism” in that stronghold. We were warned to be careful and look out what we were about.[64]

We again called on the American consul, claiming protection for Elder Porter, whose permit was about to expire. He promised to see the magistrate and do all he could for him. On April 1st we called on the American consul, who had just returned from the police station, holding a card in his hand on which were printed our articles of faith. He said, holding up the card and speaking to Elder Porter, “This is the only cause against you, and if Stevenson does not look out he will have to share the same fate as you, although he is a native. Your religion is not wanted here. You have already created jealousy in the churches.”[65] He then advised us both to leave the garrison.[66]

Elder Porter’s permit being now exhausted a passage was secured for him on a steam packet;[67] but, according to a dream that we had, I was to remain and establish the gospel.[68] I immediately went to our place of prayer on the mountain, and while I gazed on my only friend steaming out of the bay up the straits I had rather strange feelings.[69]

Previous to leaving England I was pointed out in a meeting as having been seen in a vision doing a good work in Gibraltar, but was told that I would meet heavy opposition in my labors. I was seen to be baptizing some persons, and heavenly messengers were seen to deliver me from the hands of the wicked.

A Mr. Elliot, who had been reading the Book of Mormon and was inclined to believe my testimony, became prejudiced by the ministers and turned me away from his door. Shortly afterwards he fell twenty feet, broke his leg and otherwise injured his body, which kept him in bed for forty days.

I visited the Jewish synagogue one day in company with a Mr. Delemar, a learned Jew who spoke six la[n]guages. He instructed me to wear my hat in the meeting as it was customary with them so to do. The pulpit was in the center. The ark, in one end of the building, being opened the parchment was taken out. It was rolled on two sticks with bells on the top of them. It was passed around the synagogue and kissed by the worshipers, while a continuous chanting was being kept up by the congregation. A portion was read from the pulpit, contributions were received and then the rolls were returned to the ark, each person bowing in that direction. Meeting was then dismissed.

On the 4th of May I visited the steam packet that brought me to the place, left a Book of Mormon and other reading matter with the clerk and got my mail. As it was raining I sat, by permission, under the porch of a guard house, reading the Millennial Star. Several persons became interested in me and asked questions about my belief. Soon an officer stepped up and inquired if I was a Methodist; but as soon as he learned that I was a Latter-day Saint he ordered me put under guard, saying that my religion was one that could not be tolerated in that place. For the first time in my life I was marched into the guard house a prisoner. I there began preaching to the guard, who listened attentively to what I had to say. After some few inquiries concerning what I had been doing in the fortress I was released, and I subsequently sold some books to one of the guard who arrested me, but whose sympathies were aroused in my behalf.

On the 24th of May, the queen’s birth-day, there was a grand celebration. The soldiers were marched to the north front, outside of the gates of the fortress. After considerable exercising of the soldiers the firing of cannon commenced from the top of the rock, 1,400 feet high, after which the galleries opened fire about half-way down the rock. Singular, indeed, was it to see fire and smoke gushing out of the perpendicular rock. The shipping in the bay was beautifully decorated with the flags of all nations.

June the 28th was a happy day for me, for at 4 o’clock, a. m., just after gun fire, as per previous arrangement, I met John McCall, a dock-yard policeman, and Thomas Miller, a gunner and driver of the royal artillery,[70] at the water’s edge, we having descended a rope ladder to the shore, and baptized them.[71] These were the first fruits of my labors after being on the rock three months and twenty days.

The Lord only knows the many privations and sacrifices I endured and the lonely hours I spent, living many weeks on the value of three to five cents per day.

Edward Stevenson to George Q. Cannon, July 15, 1885[72]

In the evening of the 28th of June we held a private meeting at the house of Brother Miller. We confirmed the two persons just baptized, and subsequently baptized and blessed some children of this same family.

Soon after this, while distributing tracts, I offered one to the attorney-general and received abuse in return. I also sent a second tract to Rev. Mr. Hambelton, by the hand of his servant. The minister soon returned it in person, throwing it abruptly at me, saying, “We belong to the established church and have no use for your tracts.”

I soon found that the priests not only ruled the people but influenced the governor and chief authorities; and in consequence of this influence a card was placed on the door of the barracks which read as follows: “An individual named Stevenson, a Mormonite preacher, is not allowed in the barracks.” This was shown to me upon one occasion as I was being marched out of the barracks, although the guard expressed sympathy for me and considered this act as base persecution.

With all this, however, they were not satisfied, but got up the following summons, which was handed me by one of the police:

“City Garrison and Territory of Gibraltar.

To Edward Stevenson, of Gibraltar:

You are hereby required to personally appear before me, Stewart Henry Paget, or any other of her majesty’s justices of the peace, in and for the said city garrison and territory, at the police office, on the 30th day of September, 1853, at the hour of eleven in the forenoon of the same day, to answer to the complaint of James McPherson, charging that you have used words profanedly, scoffing the holy scriptures, and exposing part of them to contempt and ridicule. Dated this 29th day of September, 1853.”

I was afterwards informed that the complainant was expecting a handsome reward if he got me into trouble. On one occasion I overheard the magistrate who issued the summons say to some ladies that he hoped soon to see me in the stocks.[73]

On the 30th I repaired to the police office. Just before going into court I had the pleasure of bearing my testimony to about fifteen persons, until prohibited by the police. I soon faced my plaintiff, and one good look in his face unnerved him. The following colloquy occurred in the court room:

“Do you know the defendant?”

“Yes, sir.”

“When was your first acquaintance with him?”

“Soon after he came here.”

“What, did he then give you those books?” (holding up some books I had sold the plaintiff and for which he failed to pay me.) “Did he wish you to change your religion?”

“Yes, he said I ought to be baptized.”

“In what way did he want you to be baptized?”

“By immersion all over in the water.”

“Did he speak against the established religion?”

“He said sprinkling little children was not right, as they were not old enough to judge for themselves—they were not accountable.”

“Is this all he said?”

“His books say all the churches sprang from the mother of harlots—the abominable Catholic church.”

“Can you find it?[”]

My books—the Book of Mormon, Voice of Warning[74] and some tracts—were then opened. I now availed myself of the opportunity of opening my Bible at the 17th chapter of Revelation, where it speaks of the mother of harlots. After the judge looked over the text for a short time he remarked, “Oh, this is the Bible.”

“Yes, sir,” I answered, “all our quotations are from the Bible.”

Many officers and spectators began to think that this was a singular way of scoffing at the holy scriptures. The questioning of the plaintiff then continued:

“Did he perform baptism on you?”

“No, but he did on a dockyard policeman and a gunner and driver of the royal artillery.”

I was still looking at my Bible, when I was asked, “Do you hear, sir?”

“Yes, sir, all that is said,” I replied.

It was then stated that I ought to give bonds to not speak to the military at all, and a bond with penalty was prepared. I was not allowed a defense, neither did they examine other witnesses who had been subpœnaed, as they found their evidence would be in my favor. On my refusal to sign a bond I was taken by the police as a prisoner into the prison room. Soon afterwards the officer came into the room and compromised the bonding by running his pen through some of the lines, rendering it as useless as a blank piece of paper. So to accommodate them I signed it and went on my way.[75] I soon baptized several persons, among whom was a woman who had held me on her knee when I was a child.[76] I organized a branch of the Church.

Edward Stevenson to George Q. Cannon, August 1, 1885[77]

Soon after my arrival in Gibraltar, a Mr. Smith invited me to take dinner with him, at which time he wept with joy for the pleasure it gave him, to eat with a son of one with whom he had enjoyed himself many times over twenty-six years before, in the good, old Methodist church. “Why,” said he, “your father helped build our good, old church; and used to play the bass viol in the choir, too. Yes, and he sold his property to me for one hundred dollars less than its real value. Can it be possible that you, a minister so well-versed in the good old Bible, the blessed Bible, have come back to us all the way from the land of America—a son of my good old Christian friend, Joseph Stephenson! It seems like a dream. You will doubtless preach for us in the church your good, old Christian father helped to build.”

“Yes, Father Smith,” I replied, “I am truly his son, and have come from Utah—over 8,000 miles away from my home, about one-third of the way around this world we now occupy. I have left my dear family, and have come as a true minister of the everlasting gospel of Jesus, as did His ancient disciples of old—without purse or scrip.[78] And I assure you Father Smith, it would afford me the greatest pleasure to have the privilege of speaking to my friends in the meeting house where memories arise like green spots in a desert, afresh in my memory, of the good things and favorable impressions made on my mind at the Sabbath schools I used to attend twenty-six years ago. I can well remember the time, although only seven years old, when my mother used to put on my white pinafore, and nicely blackened shoes, and my father bowed down and prayed to the Lord in that house he sold you. I feel to bless them for setting my feet in my youthful days in a Christian life and for the good that I received in this Sabbath school. But my father now sleeps with those who have passed behind the vail, he died when I was but eleven years of age.

“At the age of thirteen, I heard Joseph Smith, the Prophet, preach by the power of the Holy Ghost. He related the heavenly vision with which he was favored;[79] I had a witness of the truth that he had told, although I was not baptized until some time later.

“I will now relate to you a vision I had. I saw in a very nice, green spot every one who had joined this new Church. They were all dressed in white robes. A messenger, and the only stranger to me, stood by my side. I was the only one who was without the snow-white robe, and this very much amazed me. I asked why this was so, he replied, ‘Look! do you see one here who has not been baptized or come in at the door?’

“But I believe as well as do those.”

“‘You have not yet come in at the door!’”

“This was sufficient for me. I was soon baptized, and was made to rejoice with a testimony of the message which has brought me to this far-off land.

“Many old friends have received and treated me courteously, but the minister not only closed the church doors against me, but himself and some of his co-religionists began to circulate many falsehoods against the truth of the gospel, and the love of many waxed cold.”

I thus bore my testimony to the truth, but my father’s good old friend closed his house against me and turned as cool as he was warm at first. He became abusive to the servants of God. I told him the consequence of his rejecting the light that he had already acknowledged, and for turning me—a servant of God, from his door, and that the hand of the Lord would speedily follow him to his sorrow.

His wife was reading the Book of Mormon privately, and was with some of the children believing. It was but a short time before Father Smith was stricken and was confined not only to his house, but to his bed. Some time after his wife called my attention to his condition and humiliation. He was not expected to live. Soon after he desired to see me and said if the Lord would only spare his life, he would serve Him better than he ever had done.

I told him that the Lord brought down and raised up; that if he desired to recover and serve Him faithfully, he should get well and the Lord would raise him up to better health. In a few days I was invited to take dinner with him and pray with the family. He was up and around reading, and a very great change had come to him and his house. He was, however, too good to endure, and he shortly burned up some copies of the Church paper and pamphlets, and forbade me to enter his house again. I of course left my testimony, telling him the consequences of his actions. I told him it would now be worse than ever with him. The poor man was very soon again confined to his bed, but not long this time, for he soon died. His family decided to go to England where they said they intended to obey the gospel.

On the 23rd of January, 1854, I had the pleasure of organizing a branch of the Church consisting of ten members, ordaining one Elder and one Priest. We partook of the sacrament and had a joyful time.[80] The branch was named Rock Port Branch of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[81]

Edward Stevenson to George Q. Cannon, August 15, 1885.[82]

There was a well-to[-]do free citizen on the rock, a former acquaintance of my childhood, and a great friend of my father when he lived on the stronghold of Gibraltar, whose name was Gilchrist. He was a Methodist, and I had taken considerable pains to inform him concerning our doctrines and had furnished him with a Book of Mormon, Voice of Warning and other books and tracts. He became convinced that sprinkling children was only man’s theory and not consistent with Bible doctrine, as Jesus and the disciples taught the people to first believe and repent and then be baptized, not to be baptized and afterwards believe and repent. Mr. Gilchrist acknowledged that I taught the truth, yet he turned me away from his house and was, therefore, more culpable.

At his own request I went to his house one day and taught him for two hours, the principles of the gospel. During this time he was called twice to dinner, but he did not go himself, nor did he ask me to partake of a meal, although he was well aware of the meagre diet to which I was compelled to accustom myself.

It appeared to me that he was convinced of the truth of the message that I bore, but was not sufficiently honest to receive it. Finally, as I was leaving him, he offered me fifty cents, saying at the same time that it was not to help me in spreading the imposture, but for my personal use. I told him that I was preaching without purse or scrip, but was unwilling to receive gifts only in the name of a disciple. I returned not again to that house.

At the same time that I was teaching Mr. Gilchrist I was laboring with a soldier named Thomas McDonald, and though he received no more instruction than the former, he accepted the truth and was baptized.[83] One night, he said, after he had retired to rest, he had a dream and a messenger whose hair was nearly white, appeared to him. This searcher after truth then asked his visitor about the Book of Mormon, as they had been talking about that record. It was opened and the messenger simply said, “How plain it is, is it not?”

In the dream he also saw me tired and weary, but hard at work digging the ground. He touched me and asked what I was doing, when I replied that I intended to sow seed and if possible reap a harvest of souls.

This man was the means of bringing several other soldiers of his regiment into the Church.

There was a painful incident came under my observation about this time that I will here just mention: One day I had as usual a parcel of books in my arm and was visiting and teaching wherever I could meet anyone who would listen to my remarks. I called at a shoe shop in the southern part of the rock where I found six men engaged at shoe making. After telling them the object of my visit and giving them some tracts I opened the book of Doctrine and Covenants where it speaks of the martyrdom of Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum, and read this aloud to the workmen.[84] As I finished reading everything was for a moment as still as death everyone present having ceased to work. In a moment one of the six broke out in an ungovernable rage, saying, “Joe Smith was served just right and ought to have been killed long before he was.”

My reasoning with him only served to enrage him more, and his closing remark to me was, “Joe Smith ought to have been cut up into mince-meat.”

I gathered up my books and said to him that he was guilty of shedding innocent blood inasmuch as he consented to it in his heart, for which cause the wrath of God would rest upon him, and he should feel His power to the consuming of his body, and that too, in a very short time. He would then know that Joseph Smith was a Prophet of God and that I was a servant of the Almighty.

On the following day he with the others came to his work as usual, but he had not been there long before he began vomiting blood, and before he could be carried to the hospital he was dead. Just before dying he said to his fellow-workmen, “I wrongfully abused that man yesterday.”

Thus did the judgment of God speedily follow him.

Edward Stevenson to George Q. Cannon, September 1, 1885.[85]

Soon after organizing a branch of the Church there was quite an agitation regarding the war in the Crimea, England, France and Turkey were allies in a war against Russia, or in the words of Daniel the prophet, the king of the north, (Russia), was arrayed against the king of the south, (Turkey).[86] All this had a tendency to militate against my labors as a missionary in the military garrison of Gibraltar, for the British lion’s interests were assailed, and all of its military had war on the brain, which generally has far more effect on the human mind than the spirit of the gospel of peace.

The elder John McLain, Corporal Hays[87] and John McDonald,[88] all in the branch just organized, were likely to go on the Mediterranean sea to be engaged in the Crimean war, and the Priest, Sergeant Thomas Forbes,[89] was about to go to Scotland, thus depleting my hard earned little branch, which had a tendency to discourage me in my efforts, if such is possible to a Latter-day Saint Elder engaged in so great a work as saving human souls.

I concluded, however, once more to apply to the governor for liberty to open up a public place of worship, and sent him the following letter:

“Gibraltar, April 24th, 1854.

“To his excellency, Sir Robert William Gardiner,[90] Governor of Gibraltar:

The undersigned, an inhabitant of Gibraltar most respectfully solicits an audience with his excellency, on business of importance. I have the honor to be,

“Your most obedient servant,

“Edward Stevenson.”

The next day I received the following:

“The Colonial secretary requests that Mr. E. Stevenson will call at his office at 12 o’clock to-day.

“Secretary’s Office,

“Gibraltar April 25th, 1854.”

I responded to the request and had a favorable reception. The colonial secretary said my case should be duly laid before his excellency, and a reply forwarded to my address.

I was visiting at this time a Prussian whom I had been teaching the gospel, inducing him to read some of our tracts and then compare our doctrines with those taught in the Bible. He was apparently convinced of the truth. I also had some Spaniards investigating our doctrines, and it was manifest to me that if I could obtain permission to open a public place of worship my chances would be increased to spread the gospel among the people.

The Methodists had been making an effort to introduce their gospel into Spain by opening a school there, but as soon as it was ascertained by the inhabitants, who are mostly Catholics, that they were tampering with their religion the innovators had to flee by night out of the country.

I received a very pleasing reply to my letter to the governor through the colonial secretary, Mr. Aderly [Adderley], and therein consent was given me to open a place for public worship. The secretary, however, stated that this garrison was a hard place for religious teachers for a Catholic once had a cat thrown at him while he was holding service. I merely stated that all I expected was the protection of the law.

Subsequently with the assistance of some friends I found a suitable place and began to hold meetings. One evening when I had a few friends in my private room a policeman came with a message for me to appear at the colonial secretary’s office on the following day. My reply was that if the secretary had any business with me he would do well to officially notify me of it, otherwise, I would not notice their bidding. The next day I received from the colonial secretary a very polite invitation to visit him at 2 p. m. the next day on business of importance, and to my own interest.

Edward Stevenson to George Q. Cannon, September 15, 1885.[91]

On May 1, 1854, my thirty-fourth birthday, Elder John McLean, Brothers Thomas McDonald and Peter Hays, with their regiment, 1,000 rank and file, marched on board of one of her majesty’s men-of-war to sail up the Mediterranean sea and take part in the Crimea war. In the midst of thundering shouts of enthusiasm the gallant ship with her precious burden of souls steamed out of the beautiful bay of Gibraltar to do honor to Briton’s flag. A solemn reflection crossed my mind on this occasion with a mental question, who of this one thousand will ever return home again to fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters or wives?

Many tears were shed over the wounded and slain during this cruel war, which lasted about two years.[92] My blessings went with the brave boys in red, especially the three brethren mentioned. These were instructed to remember their prayers as they were in the hands of the Lord who could protect them even in the hour of fierce battle, and also to use their influence to spread the gospel among their comrades. A subsequent letter brought news that Elder McLean had organized a branch of the Church in a Turkish burying ground, and while doing so, bottles and other missiles were thrown at him and his companions. The branch was named the Expeditionary Force Branch of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[93]

Frequent letters revealed many of the horrors of warfare, such as being compelled to lie in the trenches before Sebastapool, in a mass of filth and vermin with no one to prepare them a change of linen. Elder McLean stated that he had been in the heavy charges at the battle of Inkerman and Alma.[94] So pressed was the charge from both sides that the soldiers were crushed together and faced each other with crossed bayonets being unable to use them for some time. He, however, came out with only a slight bayonet wound in the arm which only kept him from duty five days. Brother McDonald was wounded by the bursting of a shell, but with his handkerchief bound up his head and continued the encounter until another shell burst close by and this time disabled him so that he was taken from the field, but soon recovered. Corporal Hays lost his arm, but his life was spared; so the lives of all three of the brethren were spared, while often the ground was strewn with the dead and dying. Thus, even in this war, the hand of the Lord was plainly seen and acknowledged.

Edward Stevenson to George Q. Cannon, October 1, 1885[95]

Soon after receiving permission from the governor to open a public place of worship, I was called upon at my residence by a policeman, and requested to call at the secretary’s office. This I refused to do without being notified officially. Soon afterwards I received a polite official notice, which I answered on the following day. I was informed by the secretary that the governor had reconsidered the matter of my holding meetings and had concluded that I should neither preach nor hold meetings. It was a time of war, and he would not allow a new religion to be introduced on the rock of Gibraltar; and if an attempt to do so should be made I would be taken up by the police.

When I took into consideration that several of the brethren I had baptized upon the rock had gone into the Russian war, and that two others were about to go to Great Britain and the spirit of war that prevailed in the garrison, I felt impressed to ask the governor for a free passage to England, which, through the colonial secretary, was cheerfully granted, as I had already learned that the governor had expressed himself willing to give me a free passage on one of her majesty’s mail packets, in order to get rid of one who had stirred up so much of a religious excitement.

As I could take my departure at pleasure, the steam packets plying twice a week between that point and England, some twelve hundred miles, I at once began prep[a]rations to leave the few remaining Saints under the care of a proper officer. To my surprise I was again called to the colonial secretary’s office, and after going through the inquisition, because I would not compromise principle, my free passage was re[s]cinded, and I was left to depend upon the Lord to open up my way. A saying of the Savior, while instructing His disciples came into my mind:

“Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin; and yet I say unto you, That even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these. Wherefore, if God so clothe the grass of the field, which to-day is, and to-morrow is cast into the oven, shall he not much more clothe you, O ye of little faith? Therefore take no thought, saying, What shall we eat? or, What shall we drink? or, Wherewithal shall we be clothed? (For after all these things do the Gentiles seek): for your heavenly Father knoweth that ye have need of all these things. But seek ye first the kingdom of God, and His righteousness; and all these things shall be added unto you. Take therefore no thought for the morrow: for the morrow shall take thought for the things of itself. Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof.” (Matt. 6[:]28).

I repaired to the open sea, where I had baptized the first members of the branch, and there washed my feet and cleansed my garments as a witness before God against the cruel authorities of this strong garrison; and felt to rejoice that I was counted worthy to be cast out for the gospel’s sake.[96]

You can, perhaps imagine my condition, over eight thousand miles from home, on a little island of only three miles by one half of a mile in size, without purse or scrip and almost friendless.

Edward Stevenson to George Q. Cannon, November 15, 1885.[97]

One night, after retiring to my bed for rest, it was made known to me by vision that my mission on the rock was fulfilled acceptably before the Lord, and I saw a scourge come upon the place soon after my departure, for it appeared to me that I was sailing out of the lovely Bay of Gibraltar on one of her majesty’s elegant steam packets.

A short time after I had this vision shown to me I received a letter from a Mr. Lambel, a resident of Li[sb]on, the capital of Portugal. In his communication, Mr. Lambel informed me of the serious illness of his brother-in-law. The doctors had given him up, as it was out of their power to effect a cure. He further stated that he and his family had read a great deal about the Latter-day Saints, and had learned of their faith in the ordinances of the gospel; and by communications from England he had been told of my mission to Gibraltar. He desired me to go to Lisbon and anoint with oil, and pray for this sick man, as they fully believed in the healing of the sick by the laying on of hands, as was customary among the ancient saints of which the Bible tells us.[98] The gentleman furnished me nine pounds English money, with which to pay my passage to Lisbon and return, which was equal to a full fare from Gibraltar to Southampton, England.

Thus was my deliverance brought about. After the governor’s unfaithfulness to fulfill his promise, the Lord opened up my way to accomplish what was shown to me by vision. This incident teaches us the lesson that the Lord is good and kind to all who put their trust in Him.[99]

Notes

[1] “Gibraltar,” Juvenile Instructor 20, no. 2 (January 15, 1885): 18.

[2] Edward Stevenson, “Gibraltar [Letter 1],” Juvenile Instructor 20, no. 4 (February 15, 1885): 55; Edward Stevenson, “Gibraltar, Letter 2,” Juvenile Instructor 20, no. 5 (March 1, 1885): 66; Edward Stevenson, “Gibraltar, Letter 3,” Juvenile Instructor 20, no. 6 (March 15, 1885): 93–94; Edward Stevenson, “Gibraltar, Letter 4,” Juvenile Instructor 20, no. 7 (April 1, 1885): 100; Edward Stevenson, “Gibraltar, Letter 5,” Juvenile Instructor 20, no. 8 (April 15, 1885): 118; Edward Stevenson, “Gibraltar, Letter 6,” Juvenile Instructor 20, no. 9 (May 1, 1885): 130–31; and Edward Stevenson, “Gibraltar, Letter 7,” Juvenile Instructor 20, no. 10 (May 15, 1885): 159.

[3] Unlike letters 1–7, letters 8–17 all have “missionary experience” in their subtitles.

[4] “Three-Quarters of a Century,” Deseret Evening News, May 1, 1895; Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 1:214–16; Stevenson, “Life of Edward Stevenson.”

[5] Porter, “Record of Nathan Tanner Porter”; Early Mormon Missionaries database, s.v. “Lyman Wight,” “John Corrill.”

[6] See Britsch, “East India Mission of 1851–56,” 150–76; Britsch, Nothing More Heroic; Crawley, Descriptive Bibliography of the Mormon Church, 2:362.

[7] Jenson, Encyclopedic History of the Church, 465–66; Crawley, Descriptive Bibliography of the Mormon Church, 2:328.

[8] The first foreign LDS missions were created in Great Britain, and from there missionaries were sent throughout the British Empire. The plan to start a mission in Gibraltar fits this pattern. See for example “The Church in 1870,” in Plewe, Mapping Mormonism, 120–21.

[9] Lorenzo Snow to Samuel W. Richards, May 1, 1852, published as Lorenzo Snow, “The Malta Mission: Letter from Elder Lorenzo Snow,” Millennial Star 14, no. 15 (June 5, 1852): 236–37.

[10] Samuel W. Richards, “Editorial: Call for Elders for Gibraltar and Bombay,” Millennial Star 14, no. 16 (June 12, 1852): 250.

[11] Snow Smith, Biography and Family Record of Lorenzo Snow, 230–32.

[12] Edward Stevenson, “Gibraltar, Letter 9, Missionary Experience,” Juvenile Instructor 20, no. 12 (June 15, 1885): 191; p. XXX herein.

[13] Edward Stevenson, “Gibraltar, Letter 10, Missionary Experience,” Juvenile Instructor 20, no. 13 (July 1, 1885): 196; p. XXX herein.

[14] Stevenson, “Gibraltar, Letter 10,” 196; p. XXX herein.

[15] Edward Stevenson, “Gibraltar, Letter 13, Missionary Experience,” Juvenile Instructor 20, no. 16 (August 15, 1885): 252; p. XXX herein.

[16] Edward Stevenson, “Gibraltar, Letter 12, Missionary Experience,” Juvenile Instructor 20, no. 15 (August 1, 1885): 229; p. XXX herein.

[17] Stevenson, “Gibraltar, Letter 13,” 252; p. XXX herein.

[18] Stevenson recorded twenty-one individuals in his journal whom he baptized or blessed as members of the Rock Port Branch. See Stevenson, diary, table after the March 31, 1854, entry; Neilson, “Proselyting on the Rock of Gibraltar,” 130–31.

[19] Stevenson, “Gibraltar, Letter 12,” 229; p. XXX herein.

[20] The Crimean War began in 1853, when Russia tried to take over land from the Ottoman Empire, in part so they could have access to the Black Sea. The United Kingdom objected to this, joining French and Ottoman forces in the fight against Russia. Most of the fighting occurred in the Crimean Peninsula, and many soldiers died from disease rather than from fighting. In 1856, all countries involved signed the Treaty of Paris, which created some compromises, including making the Black Sea a neutral zone. Jones, “Wars and Rumors of Wars,” 30; Temperley, “Treaty of Paris of 1856 and Its Execution,” 387–414.

[21] Edward Stevenson, “Gibraltar, Letter 15, Missionary Experience,” Juvenile Instructor 20, no. 18 (September 15, 1885): 279; p. XXX herein.

[22] John McLean was baptized on January 6, 1854, and became the president of the LDS Expeditionary Force Branch in Turkey. His division fought in the Battle of Inkerman in November 1854, in which he was wounded by a bayonet. He attempted to preach to fellow soldiers in the war and was mainly unsuccessful, but there were a few converts. Jones, “Wars and Rumors of Wars,” 32–34; LeCheminant, “Valiant Little Band,” 20–21; Stevenson, diary, table after the March 29, 1854, entry.

[23] Edward Stevenson, “Gibraltar, Letter 14, Missionary Experience,” Juvenile Instructor 20, no. 17 (September 1, 1885): 262.

[24] Stevenson, diary, May 15, 1854.

[25] Sonne, Ships, Saints, and Mariners, 42.

[26] Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel database, s.v. “Seth M. Blair/

[27] See Neilson, Bray, and Johnson, Rediscovering the Sites of the Restoration.

[28] Seventy is a Latter-day Saint priesthood office below that of Apostle. The organization and functions of the seventy have changed significantly since the church’s beginning, but per Doctrine and Covenants 107:93–94, there have consistently been seven presidents who preside over the other members of the seventy. Both the Old and New Testaments speak of groups of seventy men performing ecclesiastical duties. Alan K. Parrish, “Seventy: Overview,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 3:1300–1303.

[29] “Three-Quarters of a Century,” Deseret News, May 1, 1895; and Joseph Grant Stevenson, “Stevenson, Edward,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 1192.

[30] Porter, “Record of Nathan Tanner Porter”; Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel database, s.v. “Nathan Tanner Porter.”

[31] Stevenson, “Life of Edward Stevenson,” 119.

[32] Stevenson, diary, September 15, 1852.

[33] Stevenson, diary, August 4, 1853.

[34] Stevenson, “Life of Edward Stevenson,” 138–40, 199.

[35] Edward Stevenson, “Gibraltar, Letter 8, Missionary Experience,” Juvenile Instructor 20, no. 11 (June 1, 1885): 175. Compare with Edward Stevenson, “Gibralter [sic] Mission, Letter No. 1,” Deseret News, January 2, 1856.

[36] Stevenson’s letter to the Deseret News as well as his personal diary indicate the missionaries actually boarded their ship on November 17. Stevenson, “Gibralter Mission, Letter No. 1”; Stevenson, diary, November 17, 1852.

[37] The missionaries sailed from New York to Liverpool, England, aboard the American Union, a Yankee ship that was built in 1851. The ship operated in various lines until it became a transient in 1877. Sonne, Ships, Saints, and Mariners, 13.

[38] Perrigrine Sessions was on his way to preside over the Manchester Conference in 1852; he got sick on the journey and never recovered, so he was sent home in 1854.

[39] The Iberia was built in England in 1835 and had some of the best passenger accommodations of the period. It had three masts and was owned by the P. & O. Line. Sonne, Ships, Saints, and Mariners, 102.

[40] Nathan Porter had this to say about their time in Southampton: “On the 11th (February 1853) we took the cars for South Hampton, the point of our embarkation for Gibraltar. Here we met with Elder James Wille, who also came with us across not only the plains but the sea also. He was now President over the Southampton Conference. We stopped in this conference until the 29th [sic] (February 1853), visiting the branches of the saints who contributed in furnishing means for our passage. Having now sufficient means we engaged passage on the steam Packet Iberia.” Porter, “Record of Nathan Tanner Porter,” 57.

[41] “While waiting for passage, we visited Portsmouth Dockyard and the Isle of Wight, and went on board the Duke of Wellington, a three decker of 131 guns, many of which were very heavy. This splendid ship is propelled by steam and sail, and has been the flag ship of the British fleet in the recent war with Russia. While on the Isle of Wight we were invited to preach in a sectarian chapel; the people were much taken up with our doctrine, not knowing that we were Mormon elders.” Stevenson, “Gibralter Mission, Letter No. 1.”

[42] Vigo is a seaport on the northwest coast of Spain. Merriam-Webster’s Geographical Dictionary, s.v. “Vigo.”

[43] The Bay of Biscay is a gulf of the Atlantic Ocean north of Spain and west of France. Merriam-Webster’s Geographical Dictionary, s.v. “Biscay, Bay of.”

[44] Oporto, or Porto, is a seaport city in northwest Portugal. Merriam-Webster’s Geographical Dictionary, s.v. “Porto.”

[45] Lisbon has been inhabited for millennia and is located on the coast of the country’s southern half. Merriam-Webster’s Geographical Dictionary, s.v. “Lisbon.”

[46] The Tagus River originates in eastern Spain and drains into the Atlantic Ocean in Portugal, where it forms a lagoon at Lisbon. Merriam-Webster’s Geographical Dictionary, s.v. “Tagus.”

[47] Cádiz, a seaport on the southwest coast of Spain and about sixty miles northwest of Gibraltar, is an ancient city dating back to the Phoenicians around 1100 BC. The Bay of Cádiz is the city’s harbor. Merriam-Webster’s Geographical Dictionary, s.v. “Cádiz,” “Cádiz, Bahía de.”

[48] Edward Stevenson, “Gibraltar, Letter 9, Missionary Experience,” Juvenile Instructor 20, no. 12 (June 15, 1885): 191. Compare to Edward Stevenson, “Gibralter Mission, Letter No. 6,” Deseret News, April 16, 1856; and “Gibraltar Mission,” Millennial Star 15, no. 17 (April 23, 1853): 266–67.

[49] “The morning was fair and beautiful. My feelings were peculiar as I gazed upon the stupendous rock of Gibralter rising from the Mediterranean Sea to the height of 1400 feet. And was it strange to have those feelings, as it was not only the land of my birth, but the field of my future labors in the ministry?” Edward Stevenson, “Gibralter Mission, Letter No. 2,” Deseret News, January 23, 1856.

[50] In the nineteenth century, passports were not as reliable as they are today, and government officials would often permit or forbid people based on subjective judgments, such as class distinctions. At this time, the population of Gibraltar was rapidly increasing, and the area’s officials tried to confront the problem by limiting the number of foreigners who visited or lived there. Even visitors needed permits. Robertson, Passport in America, 15; Constantine, Community and Identity, 93–131.

[51] Porter had this to say about how they got into Gibraltar without identification: “We disembarked with our friend Mr. Willis, he having ordered a conveyance to take him to his residence. He invited us to put our luggage in with his and accompany him to his home. We gladly accepted the invitation, and thus made our way into the garrison with our friend as a guide, which deluded the guards and sentinel at the gate from recognizing us as strangers from any foreign land or clime. So we were permitted to enter through the gate without any questions being asked as to our nativity, who we were or from whence we came, and so we were not under the necessity of obtaining a pass, which is required of all foreigners who wish admittance into the Fortress.” Porter, “Record of Nathan Tanner Porter,” 59–60.

[52] Climbing mountains and dedicating the land for the preaching of the gospel was a common occurrence at the time. In September 1850, Apostle Lorenzo Snow and his companions climbed a mountain in Italy and there offered a prayer dedicating the land to the preaching of the gospel. In December 1850, the missionaries in Hawaii climbed a mountain near King’s Falls, built a three-foot altar, and knelt in prayer to dedicate the land. Jesse Haven and his companions, who had been called on missions during the same 1852 meeting as Stevenson, climbed the mount called Lion’s Head in South Africa in April 1853 to dedicate the area to receive their message; Elder Leonard I. Smith wanted to call the peak “Mountain Brigham, Heber, and Willard” for the First Presidency. James A. Toronto, “Italy,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 556–58; Britsch, Moramona, 4–5; Monson, “History of the South African Mission of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,” 18–19; chapter 4, “Jesse Haven and the Cape of Good Hope Mission,” p. XXX herein <”Elders Walker and Smith, and myself went on this mountain”>.

[53] Roman Catholicism eventually overtook Islam as the dominant religion of Gibraltar. Methodism, an eighteenth-century break-off from the Church of England, was planted in Gibraltar in 1769, when it was established by British soldiers. Missionaries and preachers for the movement were continually sent to the area in the ensuing years. A formal society was established on the Rock by the early 1800s, and the first official chapel was completed in 1810. Methodist schools were established in the 1830s, and many families, even non-Methodists, began sending their children to those schools, an action that concerned the Roman Catholic priests. The Methodist missionaries regarded these schools as an essential aspect of converting people, but most students became Catholics. Methodism struggled against the Church of England, and missionaries to Spain fought against Catholicism, but Methodism retained a presence. See Jackson, “Methodism in Gibraltar.”

[54] Reverend George Alton arrived in Gibraltar in 1847. In addition to overseeing his Methodist religion in Gibraltar, he also attempted to distribute tracts and Bibles in heavily Catholic Spain. By 1854 he was in charge of all Methodist work in Gibraltar and was able to negotiate the Methodist Church through clashes with the Anglican Church. In 1855, he relocated to Madrid to supervise the printing of Bibles but still oversaw Methodism in Gibraltar. He left Spain in 1856 because of social upheaval there and went back to England in 1858, but he returned to Gibraltar in 1862. Spain was still too intolerant of Protestants, so he spent most of his time in Gibraltar. During his second term in Gibraltar, he helped provide the community with clean water, and he thus helped diminish persecution against Methodism. Jackson, “Methodism in Gibraltar,” 231–42.

[55] “After meeting, being introduced to Mr. George Alton, Methodist missionary to this place, we desired the privilege to preach to the people from his pulpit, at some convenient time. After many equivocations and apologies, we got a positive denial in as polite a manner as his genteel manners could admit, although my father had been a leading member of this society, and myself and others of the family had been baptized.” Stevenson, “Gibralter Mission, Letter No. 6.” Mormon missionaries often relied on the hospitality of other Christian clergy members for places of preaching and worship.

[56] Sir George Adderley was a British colonial secretary in Gibraltar. Colonial Magazine and Commercial-Maritime Journal, 1:125.

[57] Although Mormon polygamy was not publicly announced until 1852, rumors of the practice had been circulating much earlier. In 1851, federally appointed officials to Utah Territory had encountered polygamy and published their grievances with the practice. Howard Stansbury and John Gunnison, who had been appointed to make a topographic survey of Utah, also published their observations on polygamy in 1852, but their report was much more positive than that of the officials. These reports gained significant attention in the public press. Whittaker, “Early Mormon Pamphleteering,” 117–20; see “Report of Messrs. Brandebury, Brocchus, and Harris, to the president of the United States,” 19; Stansbury, Exploration and Survey of the Valley of the Great Salt Lake of Utah, 136–38; Gunnison, Mormons, or, Latter-day Saints, 67–72.

[58] Stewart Henry Paget (1811–69) came from a noble Welsh family and was appointed police magistrate in Gibraltar in March 1840. Roberts, Eminent Welshmen, 1:393; Bulletins of State Intelligence, 127.

[59] “Called at two o’clock at secretary’s office, where I was closely questioned. He wished to know if I was a Wesleyan minister or Church of England, &c. My reply was, that as I saw all religions tolerated, I did not expect to be questioned in this free country as to my religion. But I was neither ashamed of my religion, nor its name. I stated I was a minister of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. This, he said, was new to him; upon which I showed him my papers, bearing Governor Young’s name, with the territorial seal affixed; when I received considerable abuse, saying I did not come out in true colors, that Mormons was our true name; he had read about Mormons and Brigham Young and his thirty wives, &c. I then referred him to our true name on my papers, stating we were called by our enemies vulgarly Mormons, and also we were misrepresented by newspaper reports; but I found reason had but little impression.” Stevenson, “Gibralter Mission, Letter No. 6.”

[60] Horatio J. Sprague (1823–1901) was born in Gibraltar, and his father, Horatio Sprague, became the American consul there in 1832. Horatio J. became the consul in 1848, after his father’s death. He served in that position until he died in 1901. “Oldest Consul Is Dead,” New York Times, July 19, 1901.

[61] Nathan Porter said the following about being allowed to stay: “In the mean time we were put under rigid examination as to our nationality, and as to how I, claiming to be a foreigner, came into the garrison without a pass. I explained that I was not so instructed nor so requested by the officer at the gate. That ended any further inquiry on that point. He said I would not be allowed to remain in the garrison without a permit. Brother Stevenson claimed to be citizen by birth, as he was born on the Rock. This he sustained by producing the certificate of his christening, obtained from the Methodist Church Record. I applied and obtained a permit to remain in the garrison fifteen days, not to be renewed was inserted.” Porter, “Record of Nathan Tanner Porter,” 60.

[62] “We then proceeded up to the summit of the rock, to our private retreat, which was named Mount Edward, and entered our complaints to a much higher court, and asked the Lord not to do as vile man had done to reject us, but to guide us by the light of his Spirit. After being thus refreshed, we returned to our lonely room, as we had hired a small room for two dollars a month.” Stevenson, “Gibralter Mission, Letter No. 6.”

[63] Edward Stevenson, “Gibraltar, Letter 10, Missionary Experience,” Juvenile Instructor 20, no. 13 (July 1, 1885): 196. Compare to Edward Stevenson, “Gibralter Mission, Letter No. 7,” Deseret News, April 30, 1856.

[64] “On our return I was invited to call at the police office, as the magistrate wished to see me; a few minutes after we passed the last sentry, a messenger left word for us. This plainly shows our movements are closely watched and known, for no one knew where we were going, except ourselves.” Stevenson, “Gibralter Mission, Letter No. 7,” 63.

[65] Porter recorded this dialogue with the consul: “As I entered the Consul’s office he arose from his seat and saying, ‘Well, I was just going to see the Chief Magistrate. Please sit down. I will be back in a few minutes.’ He left having but a few yards to go. He soon returned, and on entering the door held up a pamphlet in his hand saying, ‘This is the reason you are not permitted to stay. You have been distributing tracts, and thus caused disturbance among the churches.’

“‘Ah, indeed’ says I, ‘I was not aware that there was a law prohibiting the distribution of religious tracts and references to the Holy Scriptures. Please, is there such law?’

“His countenance dropped with the reply, ‘No, not that I am aware of.’

“‘And is there any precedent to this charge? Has any person or persons been prohibited from such distribution?’

“‘No sir, not that I am aware of.’

“‘Then sir, why is this brought against me as a charge?’ I looked him straight in the eyes.

“He replied, ‘You know what it is.’

“‘Yes’ says I, ‘you mean to say it is religious prejudice.’

“‘Yes’ says he, ‘that is it. The governor consults the ministers and favors them against any thing prejudicial to their welfare religiously.’” Porter, “Record of Nathan Tanner Porter,” 62–63.

[66] “As I was passing the garrison library, also the sappers library [for British engineers], those tracts I had left was handed me, saying the clergymen had decided they were a nuisance to the library, and would not be allowed to remain. Many who were formerly friends began to look suspiciously upon us, and treat us with disdain, saying we were Mormons and deceived, but always failed to show us wherein, only the learned ministers said we were wrong, and the old apostolic gospel was no longer needed.” Stevenson, “Gibralter Mission, Letter No. 7.”

[67] Nathan Porter recorded his final moments in Gibraltar: “Brother Stevenson accompanied me to the side of the steamer where we shook the parting hand under circumstances to us very trying. We commended each other to God, trusting that in his providence we would meet again in due time. I watched his return to the shore to enter again that forbidding Fortress, whose rulers had rejected us and forbid our testimony being sounded in her halls or on the corners of her streets. This was the 1st day of April 1853. They doubtless thought we were both leaving their quarters, but were April Fooled when they saw him again within the walls.” The Mormon elders seemed to relish the opportunity to deceive the local authorities, given how they had both been treated and how one had been expelled from the British colony. Elder Porter then labored as a missionary in England from 1853 to 1856. Porter, “Record of Nathan Tanner Porter,” 63–67.

[68] “Finding no other resort but the fulfillment of the manifestations we previously had, which was—Elder Porter would have to go, and I remain alone to establish the work we came to perform, I found a passage home to England for Elder Porter, by paying 20 dollars, which had been previously given me, and I much required to sustain myself.” Stevenson, “Gibralter Mission, Letter No. 7.”