Chauncey West and the Siam and Hindoostan Missions

Reid L. Neilson and R. Mark Melville, "Chauncey West and the Siam and Hindoostan Missions," in The Saints Abroad: Missionaries Who Answered Brigham Young's 1852 Call to the Nations of the World, ed. Reid L. Neilson and R. Mark Melville (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 199–256.

Historical Introduction

“I cannot say that we have done any very great things during our mission,” Chauncey Walker West reported after returning from his 1852–55 mission to Asia, “but this much I can say, we have done the best that we knew how.”[1] From the perspective of gaining converts to the restored gospel, West was right. He did not record baptizing large numbers of converts,[2] and his attempts at preaching were met with great opposition. He had been called to Siam (modern-day Thailand),[3] but he didn’t even make it to his assigned field of labor during nearly three years away from home. But even though he did not see the proselytizing successes he had hoped for, he saw cultures and places unfamiliar to most nineteenth-century Americans and his fellow Latter-day Saints. West made sacrifices to leave his young family behind in the new Utah Territory, and he traveled by wagon to California, then by ship across the Pacific Ocean to India. He and his companion, Benjamin F. Dewey, were the first Latter-day Saint missionaries to preach in the island nation of Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka).[4] On his return, he had a harrowing journey through the coral reefs of Southeast Asia and made a stop in China. Fellow Latter-day Saints regarded these accomplishments as “a great and good work.”[5]

Chauncey West’s Early Life, 1827–52

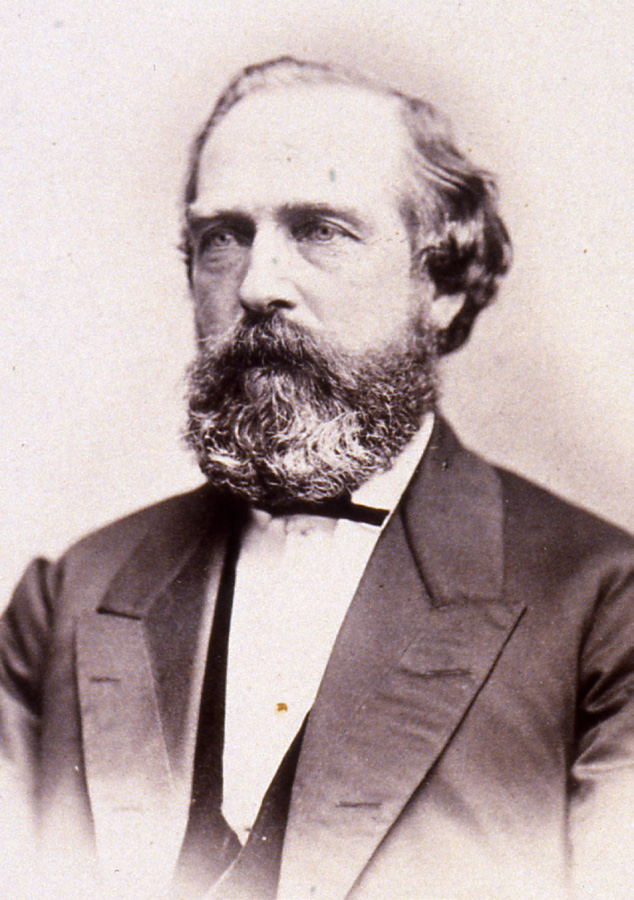

Chauncey West. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Chauncey West. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Born on February 8, 1827, in Erie County, Pennsylvania, Chauncey Walker West was baptized at age sixteen and moved with his family in 1844 to Nauvoo, Illinois, where he was ordained a seventy at age seventeen. In 1846, he married Mary Hoagland, and his family left Nauvoo. His parents and his older brother died in Winter Quarters, Nebraska, so he and Mary brought his three younger siblings (ages sixteen, thirteen, and five) to Utah, where they arrived in October 1847.[6]

Having traveled west in the first year of Mormon settlement, Chauncey West became involved in many of the important aspects of building up the new territory. In the spring of 1849, he was one of many people sent to establish Fort Utah (now Provo).[7] Later that year, Brigham Young sent Parley P. Pratt to explore new places in southern Utah for settlement. West was part of this expedition, which suffered hardships due to the cold and snow. In January 1850, this group was low on provisions, so Pratt and West traveled swiftly to Fort Utah to send supplies and a rescue party to the rest of the team.[8] After returning from this exploring mission, West continued to live in Salt Lake City.[9]

A History of the India Mission

While Latter-day Saints were relocating from the Midwest and colonizing Utah, they were still spreading their faith around the world. In 1849, British converts George Barber and Benjamin Richey had arrived in Calcutta,[10] India, as sailors and began informally preaching the doctrines of the restored gospel. Following a request from these two sailors, Joseph Richards was sent on a mission to India and arrived in 1851. He baptized a few converts and established a branch.[11] In early 1851, Apostle Lorenzo Snow, who was laboring in Italy, sent William Willis and Hugh Findlay[12] to India[13] and Thomas Lorenzo Obray to Malta.[14] Snow had intended to go to India himself, but the vessel he was going to take was damaged.[15] In the spring of 1852, he was called back to church headquarters in Utah along with the other Apostles evangelizing in Europe. Before he left, he expressed his hope that missionary work might spread beyond its Italian mission headquarters. That May, Snow asked the European Saints for additional missionaries for Bombay, India, before departing for Utah.[16] By May 1852, there were some church members around Calcutta, and Hugh Findlay established a small branch at Poona in September 1852.[17]

Chauncey West’s Mission to Asia, 1852–55

Lorenzo Snow’s hopes of expanding missionary work in India were realized when the First Presidency called a special missionary conference in Salt Lake City in August 1852. Nine missionaries were called to India: Nathaniel V. Jones, Amos Milton Musser, Truman Leonard, Samuel Amos Woolley, William Fotheringham, William F. Carter, Richard Ballantyne, Robert Skelton, and Robert Owens. Four others were called to go to Siam: Chauncey W. West (as president of the mission), Benjamin F. Dewey, Elam Luddington, and Levi Savage Jr.[18]

Benjamin Franklin Dewey was born in Massachusetts in 1829 and was baptized in 1847, just before traveling with Brigham Young’s pioneering company to the Salt Lake Valley. In 1849, he accompanied Jefferson Hunt’s wagon train that escorted gold-seeking emigrants to California,[19] and he returned to Utah in 1850.[20] Elam Luddington was born in 1806 and baptized in 1840; he served as a lieutenant in the Mormon Battalion.[21] Levi Savage was born in Ohio in 1820 and was baptized in 1846; he was also a member of the Mormon Battalion and arrived in the Salt Lake Valley in October 1847. He married Jane Mathers in 1848, and she died in 1851. Savage left his one-year-old son in the care of his sister Hannah Eldredge when he left on his mission.[22]

Of the four missionaries called to Siam, Elam Luddington was the only one who actually made it to his assigned mission. Complications from the Anglo-Burmese War[23] and ship schedules prohibited the missionaries from going there, even though West tried repeatedly. West and Dewey preached on Ceylon, but financial constraints prohibited Luddington and Levi Savage from joining them. All four of the elders preached in various parts of India for a time. Proselytizing in these locations was no easy task. Christian missionaries had incited the local populations against the Latter-day Saints for aspects of their peculiar doctrine, especially plural marriage. The missionaries were often forbidden from preaching to British soldiers. And native Indians would be outcasts and outcastes if they became Latter-day Saints, so they would only stick to this new faith if they were paid to do so—which was impossible for these moneyless missionaries to accommodate.[24] After West and Dewey left, Savage and Luddington stayed behind and preached in Burma (Myanmar).[25] Luddington did eventually make it to Siam, but his only converts were the ship’s captain and his wife.[26]

Meanwhile, West and Dewey had a harrowing time making their way back to America. For a time, they worked as sailors for their passage. The ships they traveled on passed through dangerous reef areas in Southeast Asia, and it was a great task to keep the vessels from wrecking on the jagged coral. Dewey was also sick for a great deal of the journey. The missionaries stopped for a time in China, hoping to meet the three elders who had been called to labor there (Hosea Stout, James Lewis, and Chapman Duncan); however, those three had already left Asia due to immense social difficulties. While in China, West and Dewey had a few premonitions that might have saved their lives: they left a hotel just before a massive boulder landed on it and killed many inside, and they opted not to board a ship that was soon shipwrecked.[27]

After crossing the Pacific and arriving in California in September 1854, West visited many of the missionaries and settlements in the area until he headed home for Utah the following spring. He arrived in Salt Lake City on July 15, 1855.

Additional Church Service, 1855–70

After returning to Utah in 1855, West played an important part in the church and Utah Territory. He moved to Ogden, about forty miles north of Salt Lake City, where he became a prominent member of the community, building several mills, constructing roads and canals, and serving as presiding bishop of Weber County.[28] In 1857, West was in charge of a regiment of the Weber Military District, and that fall he led units from Ogden to Echo Canyon to block a federal militia sent by President James Buchanan from entering Utah.[29]

The mission to Asia was not to be West’s only international mission. In 1862, William H. Hooper and George Q. Cannon were elected as senators from Utah Territory, and they were sent to Washington, DC, to petition for statehood. Church leaders called West to temporarily take over the responsibilities of Cannon, who was president of the European Mission. West traveled with Hooper to New York and then to Washington, DC, where he met President Abraham Lincoln[30] before continuing to England. The mission was based out of Liverpool, England, but West also visited France, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Prussia, Denmark, and Sweden in company with Brigham Young Jr.[31] He returned to Utah in the fall of 1863.[32] In 1866, the Deseret Telegraph Company completed a telegraph line from Salt Lake City to Ogden, and its first message was from Brigham Young to Bishop West and stake president Lorin Farr.[33]

Ogden became the terminus for the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, and the construction of the railroad gave West some interesting opportunities. Chauncey West and Lorin Farr contracted with the Central Pacific Railroad to employ two thousand men to build the railroad east from Humboldt Wells, Nevada. West was present on May 10, 1869, when the railroad was completed at Promontory Summit.[34] As Latter-day Saints who were gathering to Zion began to travel by train, West was responsible to help supply them with comforts and provisions as they arrived.[35] While working on the railroad, he got sick, so in late 1869 he and his first wife, Mary, traveled to California to conduct railroad business, hoping his health would improve in the coastal climate, but he died there on January 9, 1870, at the age of forty-two. Mary died soon thereafter at forty-one.[36] Some traditional stories claim that the town of Farr West, created in 1890 from Harrisville in Weber County, Utah, was named for Lorin Farr and Chauncey West.[37]

As for the other missionaries called to Siam, Benjamin Dewey became a miner and died in the mining community of Chloride, Arizona, in 1904.[38] Levi Savage circumnavigated the world on his return from Asia and became famous for being a captain in the Willie Handcart Company, advising against travel late in the season but supporting the ill-fated pioneers on their journey; he was a farmer and died in Toquerville, Utah, in 1910.[39] Elam Luddington was also a farmer until he died in Salt Lake City in 1893.[40]

Chauncey West’s Family Life

Chauncey West married Mary Hoagland, the sister-in-law of George Q. Cannon, in May 1846, and they had a daughter, Margaret, while crossing the plains to Utah. Margaret died as an infant, but Chauncey and Mary had two sons, Chauncey Jr. and Joseph, in their first few years in Salt Lake City.[41] Immediately before leaving on his mission, West sold some of his property to his father-in-law, Abraham Hoagland, who was bishop of the Fourteenth Ward.[42] Little is known about their family life during West’s absence, but it is supposable that Hoagland and his wife, Margaret, were able to oversee Mary and the two young West sons.

After his return, West married eight more wives: Sarah Covington in 1855, Martha Joiner in 1856, Jenette Nichol Gibson in 1857, Adeline A. Wright in 1858, Angeline Shurtliff in 1866, Mary Ann Covington (possibly in 1864), Susan H. Covington in 1867, and Louisa Musgrave at an unknown date. He had a total of thirty-five children with all nine wives, nineteen of them living to maturity.[43]

Source Note

Chauncey West wrote five letters about his mission to the Deseret News, which were published between August 11 and November 14, 1855. The letters describe a chronological narrative of his mission: the journey to California, sailing across the Pacific and Indian Oceans, proselytizing in India and Ceylon (Sri Lanka), perilous sailing through Southeast Asia and a stop in Hong Kong, and traveling back to Utah. West’s writing style is entertaining and even amusing, as he vividly describes such events as monkeys “show[ing] off their gymnastics among the trees” and “the sun hot enough to bake one’s brains.”[44] It is obvious that the Deseret News edited his letters, as West’s journal entries and holograph letters have largely nonstandard spelling and grammar; some of his relevant journal entries have been provided in the footnotes, mostly unedited.

Document Transcripts

Chauncey W. West to the Deseret News, August 11, 1855[45]

G[reat]. S[alt]. L[ake]. City, August 11, 1855

At a Special Conference held in Great Salt Lake City, Aug. 28, 1852, we were appointed a mission (in connection with Elders Elam Ludington and Levi Savage)[46] to Asia, the Kingdom of Siam being our place of destination.

On the 20th day of October we bid adieu to our families,[47] friends, and the lovely city of the saints, and started on our mission, being accompanied by 34 other missionaries for different nations of the earth.

We passed thro’ the southern settlements in the Territory, holding meetings with the saints.[48] We found them united, and the Spirit of God was in their midst, and they felt their interests were identified with ours in building up the Kingdom of our God. As we were about to leave them, they brought forward their grain for us to feed our animals while crossing the deserts, and oft they would bring more than we could carry. We felt to say in our hearts, may God bless such brethren.

We left Cedar city Nov. 8; had a good time crossing the plains and deserts. December 3, arrived at San Bernardino; found the saints all well, and rejoicing in the truth, glad to make us welcome to their homes and firesides, the few days we might stay with them.

Dec. 19, we bid the saints of San Bernardino farewell, and were accompanied by the brethren to San Pedro, a distance of 90 miles. Dec. 29, took passage for San Francisco on board the brig Fremont, in command of Capt. [John] Erskine. Jan. 7, arrived there, and on the 9th, leaving Elder Dewey and others in San Francisco, took steamer for Sacramento city.

From thence I traveled on foot to Mormon Island, Salmon Falls, Greenwood Valley, Mud Spring, Dimond Springs, Hangtown, and Prairie City,[49] holding several meetings by the way; found a number of brethren from the Valley, who contributed liberally to assist on our journey to San Francisco.[50]

Jan. 29 [sic], returned to San Francisco. On inquiring for a vessel sailing direct to Siam, we could find none. We were informed by an old sea captain that the only and best way for us would be to sail to the city of Calcutta, and from thence take the overland route thro’ the kingdom of Burmah to Siam.

Jan. 28, we took passage in company with the Hindostan Mission, on the ship Monsoon of Boston, Capt. Z. Winzon, for Calcutta. Saturday, 29, weighed anchor, made sail, and bid our native land farewell. Feb. 10, passed the Sandwich Islands, being the quickest passage ever known to those Islands.

March 1, we neared Farewell, on D. Toon’s Island, one of the Ladrone group, in the China Sea. There is on this island a volcanic mountain 2000 feet high.[51] On the 10th we passed along the coast of Coachin China,[52] and on the 19th passed Pirto Pisscany isle,[53] in the China sea, towering 2000 feet above the water, densely crowded with a mantle of beautiful green foliage, which caused it to have a lovely appearance.

March 20, sailed into the straits of Singapore, passed the city of Singapore,[54] near sunset, which lay in the distance some 20 miles; then sailed up the straits of Malacca,[55] and on the 27th sailed into the Bay of Bengal;[56] passed mount Ophir, where it is said Solomon got his gold for ornamenting the temple of Jerusalem.[57]

April 7, we sailed close alongside of Barren island, on which is a volcanic mountain rising 600 feet high. On the top of this mountain are two very sharp peaks, one extending considerably above the other, out of which issues a puff of black smoke every ten minutes, then immediately changes its color to a yellow, and from that to the resemblance of steam. The lava had run from the top of the mountain into the sea, and in appearance resembled stone coal.[58]

The 12th, passed thro’ the Andaman islands.[59] Sunday, 24, took a pilot at what is called the Sandheads; here we had to change day and date in journals, it being Monday, 25, in Hindostan, one day later than at home in America.[60]

I would here remark that these Sandheads are extensive deposits of sand and mud, that are continually increasing, being the settling of the muddy waters of the Hoogley.[61]—They extend into the bay about 75 miles.

[Tuesday], 26, we landed in Calcutta, being 86 days out from San Francisco, distant 11,000 miles.

We found a few saints in Calcutta, who were glad to see us and to administer to our wants.[62] The cholera was raging very much when we arrived in Calcutta; several hundreds dying daily.

April 29, called on the American Consul, Mr. Hoofniele, whom we found to be very much of a gentleman. He made a great many inquiries, and conversed freely, after which he said, any favor he could bestow upon us he would gladly do; he informed us that we could not go the overland route thro’ Burmah to Siam, because the East India Company were carrying on a war with the Burmese, and that no European would be allowed to pass thro’ their country; he also said he thought we would be troubled to find a vessel sailing to Siam until fall, when the Monsoons would change.[63] On inquiring among the shipping we found that was the case.

The way to Siam being hedged up for a time, we tho’t we would seek a field of labor in some other place. We met in council with the other elders of the mission, and it was decided that Elders Luddington and Savage should go to Burmah, and that br. B. F. Dewey should go with me to the island of Ceylon; and we were to labor in these two places until the way should open to Siam.[64]

May 7.—I left Calcutta with Elders [Truman] Leonard and [Samuel] Woolley for the city of Chincery,[65] up the Hoogley, took passage in a dinga (small native boat);[66] as we went out of the city, we passed the place where the Hindoos[67] were burning their dead; the stench was awful; we could but just get our breath while passing.

The cholera and yellow fever were sweeping them off so fast that they could not obtain wood sufficient to burn them, and there were to be seen heads, arms, legs, &c., &c., scattered here and there, with the flesh partly burnt off, and the vultures in swarms eating the balance. As we went up the river, we saw hundreds of dead bodies floating down the stream; at the same time, both sides of the river were strewed with men, women and children who were bathing.[68]

We arrived at Chincery in the evening, where we found Elder Richards,[69] and a small branch of the church, waiting to receive us. I tarried three days with the brethren in Chincery, had some good meetings, which made the devil mad, and his emissaries commenced to roar.

March 10, I gave Elders Leonard and Woolley the parting hand, and took passage in a native boat, with Elder Richards for Calcutta, where we landed in the evening; found the brethren all well and in good spirits. May 15, I took passage with Elder Dewey on the steamship ‘Queen of the South,’ Capt. Davis, for the island of Ceylon. During the day and night five persons were thrown overboard, who died of cholera; on the 16th, nine more died; a general time of excitement on board. On the 17th, seven died; on the 18th five died; on the 19th, three died.

On the morning of the 20th we arrived at Madras,[70] the capital of South India.[71] We took a boat and went on shore to view the city; on arriving at the water’s edge, we found a carriage waiting for us; it had been sent by Capt. Carmel, with whom we had become acquainted while on the passage; he had lost his ship a few weeks before, and was then on his way home to England. We had the carriage for the day, rode round the city and thro’ its principal streets, visited two cars of the Juggernaut,[72] and many other heathen curiosities. In the evening went on board; three had died during the day.

May 21, weighed anchor and sailed for Ceylon, where we landed on the morning of the 26th. We found a great prejudice existing among the people, and they were ready to reject us. While walking from the wharf into the town, we fell in company with two gentlemen who entered into conversation with us, during which we told them we were missionaries; they seemed very much pleased to hear that, and said they welcomed us to the island, and then commenced to tell us about the great success of the missionary societies in that country; said we must go and see their minister; after which they asked to what missionary society we belonged; we told them to the Lord’s; they said they hoped all missionary societies belonged to the Lord, and wished to know to what church or faith; we told them to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints; at which their countenances fell, and they said, “What! not Mormons?” We told them the world gave us that name.[73]

They said they had heard all about the Mormons, and said they could assure us we would meet with great opposition; that they had a pamphlet that told all about Joe Smith and the Mormons. I will here mention that a large number of tracts had been sent from Europe and circulated among the people, filled with the most base lies and misrepresentations.[74]

At this moment Capt. Carmel, who furnished us the carriage in Madras, came up and invited us to go and ride with him to the cinnamon gardens,[75] a distance of 4 miles; we accepted the invitation, thinking it would not be gentlemanlike to refuse, after he had manifested so much interest in our welfare; altho’ I must say, our minds at that time were in another direction from that of pleasure riding.

The road to the cinnamon gardens was smooth and nice, leading thro’ beautiful groves of cocoanut and breadfruit trees,[76] interspersed now and then with small fields of rice. On arriving at the garden, a native hailed us and asked what we wanted. We told him, to view the garden; he then conducted us thro’ a narrow lane to a large house, neatly built and well furnished. The owner of the garden was a half caste,[77] and was very kind and affable in all his actions; he accompanied us thro’ the garden to a long house where there were a large number of natives peeling and curing the cinnamon. He then took us to the other end of the garden, where he showed us the lemon, orange, plantain, mango, mango steam, nutmeg, clove, and guarver trees;[78] after which he took us to his pine-apple bed,[79] and told us to pick what we wanted. We then went to his house and spent an hour in conversation with him, and found him to be a staunch defender of Catholicism.[80]

On returning to the City, the steamer was about to leave. Mr. Carmel requested us to give him a letter of introduction to some one whom he could call upon for information and instruction when he arrived in England; said he was greatly pleased with our principles; thought we would yet see him in the Valley of the Salt Lake.—We gave him a letter to Elder S. W. Richards, who was then presiding in the British Isles felt very much affected when we parted, and said if he had not lost all he had, and had to borrow money to get home with, he would have assisted us.

In the evening it had got noised around that two missionaries had arrived. Mr. Ripen, a minister of the Presbyterian Church[81] sent a young man to hunt us up, and bring us to his house. We went with the young man; on arriving at his place we met him in the yard, and he gave us a welcome shake of the hand, and said he hailed our arrival with joy; invited us into his parlor (which was furnished in a grand style) asked us to take seats, and then called in his wife, and gave us an introduction to her; after which he commenced to tell us about the different locations of missionary Societies on the Island; of their progress and prosperity, and said he hoped we might be blessed in the good cause.[82]

He then asked us to what church we belonged; we told him to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, commonly known as Mormons. At hearing this, he seemed to be greatly amazed, and said we could not expect any favor or assistance from him, when our faith differed so widely. He had read some of our works, and considered our doctrines absurd and unscriptural.

We asked him if he would point out some items of our faith that did not agree with the Word of God. He commenced by denying that baptism was necessary to salvation. When he found that he could not sustain his point, admitting the Bible to be the criterion, he flew into a passion, and requested we should work a miracle; we told him we were not sent to work miracles to make the people believe, but to bear testimony of the truth of the Gospel, and that they who rendered obedience thereto should know of its truth. He still contended he should have a miracle done to make him believe; we told him if he could find an account within the Bible where a servant of God ever did a miracle, when called upon by the people, in order to make them believe, we would do one for him. He continued to get more enraged, and asked if we believed in the doctrine of Polygamy; we told him we did;[83] he then cooled down a little, and commenced to talk on that subject; we showed him that Holy men who were acknowledged of the Lord had practised it; he said it was in the dark ages, and the Lord looked over their ignorance. We told him we thought he must be mistaken, it could not be the dark ages, when God condescended to speak with man, and sent His holy angels to instruct him from time to time, and enlightened his mind by dreams and visions; that we believed that one glimpse thro’ the vail would teach a man more about the things of God, then the reading of volumes. He commenced to get angry again, and said he did not wish to talk with such men.

We took the liberty to bear our testimony to him of the message which God had sent to man in this day and generation of the world, and cautioned him to be sure and get in the right road, if he wanted to get into the kingdom of God, for Jesus said they would come from the East and West, from the North and South, and set down in the kingdom of God, with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob;[84] and they were the greatest Polygamists of whom we read. And moreover, in John’s revelations there is an account of him having seen the Great City—New Jerusalem descending from God out of heaven, having its twelve gates on which were inscribed the names of the twelve Patriarchs, the sons of the great Polygamist, Jacob; and John says, ‘Blessed are they that do his commandments, that they may have a right to the tree of life, and may enter in thro’ the gates into the city.’[85] Now sir, said we, if ever you get into that city, you will have to make friends with Polygamists.

{To be continued.}

Chauncey W. West to the Deseret News, n.d.[86]

The next day after we arrived at Galle,[87] a piece was published in the newspaper notifying the people that we had come to declare one of Joe Smith’s revelations, that we preached a new gospel, that we were polygamists, that they must beware of us and not receive us, for if they did, they would be partakers of our evil deeds.

We found it impossible to get a house to hold meetings in, or any person to take us in and feed us. As we had a letter of introduction to a gentleman in Colombo,[88] (Mr. Andra) we concluded to go there, a distance of 70 miles. On arriving at Colombo, he received us kindly, but as he was a lawyer, religion did not trouble him much; however he was a member of the church of England,[89] but he acknowledged to us that he did not believe there was any more salvation in that church than there was out of it, and that he was an infidel in belief. He thought so much of his good name, that he could not afford to keep Mormons long, for fear of being published in the papers; however he let us stop with him for a few days, during which we visited among the people, trying to get a house to hold meetings in, but all to no purpose.

We went to the authorities and tried to get the public hall; they being men who belonged to some of the christian churches, of course we could not have it. We left our testimony with them. We visited both high and low, priest and people, but reasoning and testifying had no good effect upon them; they would not open their doors for preaching, neither would they feed us unless we paid them.[90] Elder Dew[e]y sold his watch to get money to purchase food, altho’ he did not get half its value.

We were denied the privilege of preaching to the soldiers or visiting them; the low class of Europeans, as well as the half castes and natives, who are educated in the English language; they are dependent on a few speculators and Government men for employment, and if they do anything to displease the priests, they lose their situation, and then starvation will follows [sic]. Thus a few great men, with the priests at their head, have the people in fetters, while the priests are rolling in luxury. As for the natives, they are generally an indolent, drunken and filthy people, subsisting on cocoa-nuts and other fruits which grow spontaneously over the island.[91]

After spending several weeks in traveling from place to place, under the burning sun of that clime,[92] we did not feel able to endure such treatment much longer, therefore we concluded to return to Galle and give the people another trial, and if they would not receive us, we would leave and go to a people that would.

The weather being very hot, it took us five days to walk to Galle; we slept upon the ground, and our food was rice and cocoa nuts. We passed thro’ 37 native towns and learned something of their sickening, immoral practices and social degradation. The promiscuous intercourse among the sexes is so common that little or no disgrace attends it, even tho’ the parties were engaged in the violation of the marriage relations, unless it be with one of the inferior rank in society; then if exposed, the one in superior standing loses reputation;[93] and that most odious practice there prevails, of a plurality of husbands; a woman may have as many husbands as suits her disposition; they do not all share alike in common, in regard to her favors, but each enjoys her attention exclusively at stated periods, or at her pleasure. When she becomes the mother of a child, she nominates a father, and he has to maintain it.[94]

On arriving at Galle, we met with the same reception as before, oftentimes being abused in a most shameful manner. After this we went and saw the American Consul’s Agent, Mr. Walker,[95] who did not treat us with respect; he laughed at our papers, and said Governor Young was the man who rode thro’ Salt Lake City with sixteen wives;[96] said we had come to the wrong place to preach Mormonism. We bore testimony to him of the gospel which we had to declare to the people; we told him we had been ill-used, and he said that was what we might expect, after which he left us.

We were told by a number of gentlemen afterwards, that he had informed them that we did not belong to America—that the “Mormons” had rebelled against the Government and violated the constitution. This official story being afloat, it also had its influence.

We concluded to leave the island of Ceylon and go to Singapore, but as there were no sailing vessels running to that port, the only chance was to go by the steamers, but they would not take us for less than $50 each. Under these circumstances, we saw no chance of getting away. A few days after, the large ship “Penola,” from Belfast, Ireland, came in for water, while on its voyage from Australia to Bombay. We concluded if we could obtain a passage, we would go to Bombay[97] and visit br. Findlay, and then sail from there to Siam, and by so doing fulfil a very singular dream which I had a few nights before relative to going to his assistance.[98]

We went on board and found no trouble in getting our passage. We returned on shore and got our trunks, and went on board again. The next evening two gentlemen came on board and told Captain Rany that they hoped he was not going to take us to Bombay; that we were Mormons, and men not worthy to associate with. Captain Rany, who was an Irishman, told them, “I don’t care a damn what their faith is—they have treated me like gentlemen and they have the appearance of such, and they are going to Bombay with me, if my craft don’t sink.”

I may here remark, that we might have been able to make arrangements with the Captains of the Steamers for our passage, if the good pious folks had not used influence against us.

After leaving Ceylon, we sailed south-west until we struck the 7th degree of south latitude, where we got the trade winds; we then steered north-east, crossed the Arabian Sea and struck the Malabar[99] coast, 71 miles above Bombay.

The day before getting into Bombay, while sailing along the coast about 10 miles from shore, the ship ran a-ground; the wind was blowing very hard, and the waves were running very high, and when the waves struck the ship they would raise her up, and then she would come down with a tremendous crash, as if she must come to pieces in a very few minutes; and to all human appearance we must be lost in the great deep; as the small boats were so placed that it would take some time to get them overboard, and when they did it was doubtful whether they would ride the sea.

Elder B. F. Dew[e]y and myself went to our room and asked the Lord that the winds would cease blowing, and that He would save us from the fury of the elements. About this time they launched a boat and it filled in a minute; a few minutes after, they put over another boat, and in a few minutes more it was almost a calm.

As we were about to leave the ship, Captain Rany discovered that she was afloat; he called to the carpenter to sound the pumps; he found three feet of water in her hold. The Captain then said he would try and take her into Bombay. He put some of the hands to the pumps and some to hoist the sails, and the next morning, the 25th of July, we landed in Bombay.[100]

We found Elder Hugh Findlay, who was happy to see us after being so long a time in that benighted land. He had a small branch of the church established in Bombay, and one in Poona, 90 miles thence. We called on Elder Findlay, the President there, to know where he would have us to labor the few months we would tarry with him; he thought it best for me to stop in Bombay and for him and Elder Dew[e]y to go to Poona.[101]

August 1st, Elders Findlay and Dew[e]y left for Poona. I held four meetings a week in Bombay,[102] and also visited a great number of people at their houses, making my own introduction by way of offering them tracts to read. I found that the people acted generally shy, and did not feel free to converse, or to accept of a book to read; I finally took the liberty to ask them the reason of that, and why they rejected us without investigating our principles—that Saint Paul’s admonition was “Prove all things and hold fast that which is good.”[103] Some of them told me that their minister had told them, they must not read our works, or they would be deceived; that it was such a deception that almost all who allowed themselves to investigate, were caught in the delusion.

Several natives attended my meeting, among whom was one who offered himself for baptism; he was well educated in the English language, and could speak several others; I had hopes he would be a useful man, but as soon as he found to his satisfaction that what I had told him was the truth, how that the elders of our church went forth without purse or scrip, and we had not a few thousand lacks of rupees[104] in the Bank of Bombay to draw from to hire the natives to acknowledge our religion, he returned to the church of England, where he said he formerly had two rupees (a piece of money worth 44 cents) a week, but now got three.[105]

The natives of India and more particularly the upper caste, whatever their religion may be, it is made subservient to present interests. The idea of their receiving by immediate revelation a message from God for their implicit obedience, is most foreign from their imaginations; he who comes to them and has no bribe to offer, has no message for them.

The English and American missionaries who have gone to that country have been furnished with plenty of money by the missionary societies at home, and when they found that they could not win the natives with their principles, they have hired them to join their churches, and have written back what great things they are doing in converting the poor heathen.

I have had numbers of them come to me and offer to leave the churches whose names they were then acknowledging and come to ours, if I would only give them a few cents more than they were then getting, at the same time they knew no more about the principles and faith of the church to which they professed to belong, than the brute-beast, and these same people will bow down and worship sticks and stones, gods of their own make, when they think there is no christian seeing them.

Truly have these missionaries fulfilled the saying of the Savior, when he said that they would compass sea and land to make one proselyte, and then he would be twofold more a child of hell than he was before.[106] They have taught them to be deceitful and dishonest. The reasons why the native whom I baptized in Bombay did not believe what I told him—that I was sent forth without purse or scrip, and had not money to hire him to be a christian, and that if he joined our church he must do it for the love of the truth—was that he knew that all missionaries with whom he had been acquainted had plenty of money and that at the same time would say they had none.

I would here remark, as the missionaries wish to keep in the good graces of the natives, it is a common thing when they come for money or something which they do not wish to let them have, they say they have none, instead of saying, they cannot let them have it. Hence the natives look for missionaries to tell them these little White lies, as the down easter[107] would say.

On the 7th of September, Elder Allen Findlay[108] from England arrived in Bombay on a mission to that country. After tarrying with me a few days, by request of his brother, Hugh Findlay, he went to Poona to take charge of the work in that place.

October 8th, Prest Findlay and elder Dew[e]y returned to Bombay. It was then autumn, and we thought it time to start for Siam, but could find no ship sailing in that direction, save the mail steamers, and it was impossible for us to obtain a passage on them without money. President Findlay thought it best to give Bombay another fair trial, consequently we circulated a small printed sheet containing some of the articles of our faith; also a notification to the people that we would hold meetings at three different points in the city, naming the places and hours of service.

I went into Fort George[109] to distribute some of these printed sheets, whereupon I was stopped and ordered to be escorted out of the Fort with a guard of soldiers, and myself or any other Mormon forbidden to return. We attended our appointed places of meetings several times, while no one came to hear. We then thought we would leave them without a chance of excuse by visiting them all at their houses, leaving our testimony and offering them tracts to read; and I must say our general reception was either the European aristocratic sneer, or that cold formal orientalism so characteristic of that country.

During this time, the brethren who belonged to the army were called away to Aden[110] in Arabia, when we ordained one elder and one teacher, and furnished them with books and pamphlets, so that they could leave a testimony of the work in that land {where they arrived in safety}.

All this time we had been continually on the lookout for a vessel sailing towards Siam via Singapore, but to no effect; the ships bound for China did not go by Singapore, as they would have to beat[111] from that place all the way up the China sea against the monsoon; but they took what is called the eastern route thro’ the straits of Sunda.[112] It was the last of December, and we felt anxious to be on our way.

On being informed that a considerable trade was being carried on between Batavia (on the Island of Java)[113] and Singapore, we concluded to try and get a passage to that port, and trust for our way to be opened from there. After being refused a passage by 14 Captains, only on condition that we would pay them $150 each, we met with Captain Bell of the ship “Cressy,”[114] of London, who said he would give us a chance to ship before the mast and work our passage. Being men who had been raised in the cradle of persecution and hardships, such an offer did not bluff us in the least. We accepted his proposal.

{To be continued.}

{By a slight inaccuracy in the interlining of the manuscript, I was made to say in my first letter, that the brethren contributed liberally to assist “on our journey to San Francisco;” it should have read “on our mission.”}

Chauncey W. West to the Deseret News, n.d.[115]

Jan. 9, 1854.—We gave the parting hand to Prest. Findl[a]y, and the brethren in Bombay, and took passage on the ship “Cressa,” Capt. Bell, for Java (at this juncture I cannot do justice to my own feelings without expressing my unfeigned gratitude to brother and sister Davies[116] for their unceasing kindness to us during our sojourn in Bombay).[117]

From Bombay we sailed south-east along the Malabar coast. On the 14th we passed the ancient town of Goar,[118] it being the first town settled by the Portuguese in India. On the 15th passed the town of Calicut,[119] and on the 21st passed the town of Cochin,[120] where several natives came on board, who supplied us with fruits of various kinds.

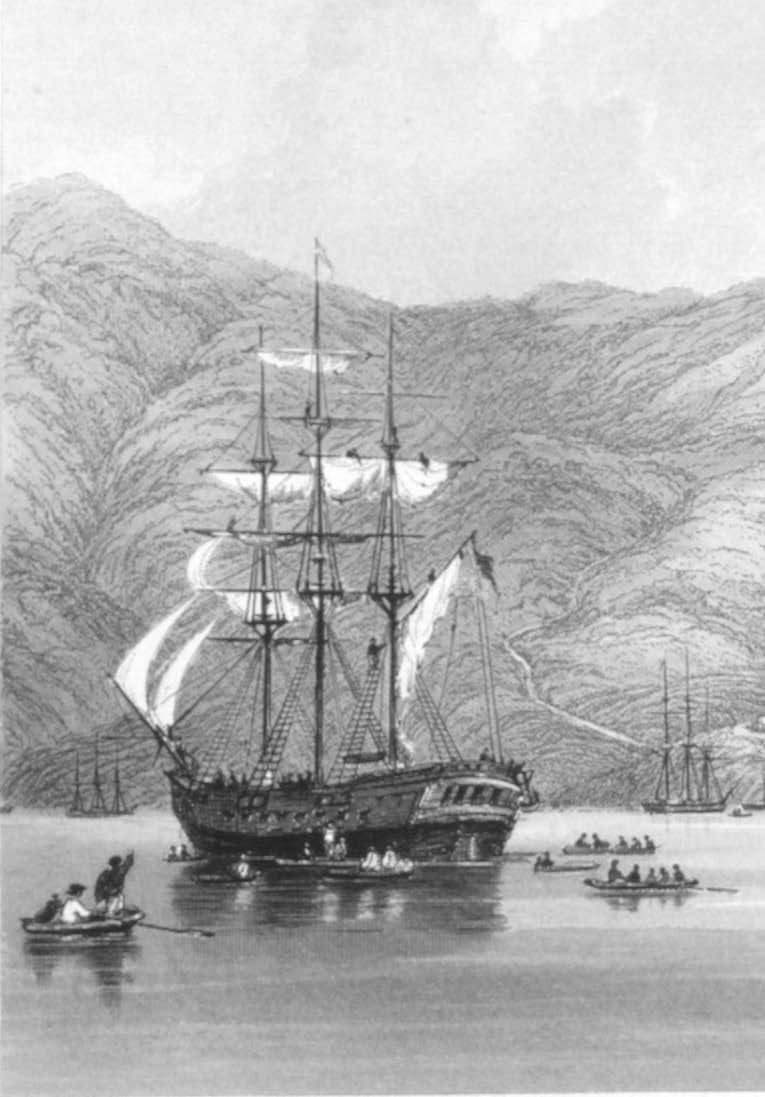

A drawing of Captain Bell’s ship, the Cressy. Original etched by T. Allom from a drawing by Miss Mary Townsend, 1850–51. Courtesy of Alexander Turnbull

A drawing of Captain Bell’s ship, the Cressy. Original etched by T. Allom from a drawing by Miss Mary Townsend, 1850–51. Courtesy of Alexander Turnbull

Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

Feb. 3.—We crossed the line; the heat of the sun was almost suffocating. On the 14th we spoke[121] the ship “Burlington,” of Liverpool, Capt. Gamble, who left Bombay the day before we did; he came on board our ship and counseled with Capt. Bell on the propriety of taking the north-east passage from Java round Borneo,[122] thinking by doing so they would beat several captains into China who left Bombay before us, calculating to take the eastern route. They finally concluded to take the north passage, although a ship had not taken that route for 30 years. On the 24th we sighted the island of Guenna;[123] the 25th, passed the island of Berila Buissa, and entered the straits of Sunday on the 26th in the morning, when six natives from Sumatra[124] came on board with some very nice shells, cocoanuts, and monkeys to sell.

In the evening we arrived at Batavia, where we found there were no vessels sailing to Singapore, with the exception of two Malay juncks,[125] and it was not considered safe for a white man to trust his life with that people; the laws were such that we could not stop there, as no stranger is permitted to tarry in the city unless he has means to take lodgings at some licensed public house, and the landlord has to examine the size of his purse, being responsible for the sustenance of all he has taken in, and obliged to see them conducted from the island. This being the condition of affairs, and Capt. Bell having proposed to let us go on with him to China, it seemed that the only and best chance was for us to accept the offer, and try and make our way from there.

March 1.—We left Batavia and sailed into the Java seas; on the 5th we neared the coast of Borneo, passed the island of Batton, and in the evening entered the straits of Macassar.[126] 6th, sailed between the Bush island and the coast of Borneo; the tide was so strong, with the wind light, we came near running ashore on the island; had to anchor until the tide changed. 7th, we sailed between Borneo and Macassar.

On the night of the 9th we encountered a very severe storm, which carried away the jibboom,[127] and split near half the sails on the ship. On the 10th we were sailing close along the shore of Borneo, found a very stiff tide, and the wind being light, we had to come to anchor.

We were seven days beating trying to round Kenneeoongon Point on the coast of Borneo. We would beat all day, tacking ship[128] between thirty and forty times, and getting within 3 or 4 miles of the point, and it then would become a calm; and during the night we would drift back to where we were in the morning.

On the fifth day, Capt. Gamble, who was in company with us, rounded the point and went out of sight. On the evening of the seventh, our Capt. got discouraged and thought he could not round the point with his craft, the tide was so strong, and he supposed Capt. Gamble had gone and left him; he swore he would strike across the Selebecean sea[129] and take the eastern route.

As we left the land and got from behind the point in the open sea, we could see the ship Burlington in the distance, the captain of which, as soon as he saw us steering in that direction, mistrusted what was up, and steered after us, and the next morning informed Capt. Bell he had been waiting for him.

About 12 o’clock the wind fell, and it became a calm and continued so until the next day at noon, when they ascertained they had drifted 40 miles from where they were when they left the coast, and they became satisfied that they could not stem the tide and cross the sea with the light winds which they would naturally get at that time of the year, and the only chance would be to go back in order to take the eastern route.

Capt. Gamble finally persuaded Capt. Bell to go back and try and round the point, thinking the tide would not be so bad. We struck the coast some 40 miles below where we left it, and commenced to beat again, and continued for three days, but could not round the point. They discovered as they supposed, a small bay or eddy between the point (which extended into the sea some three miles) and the main land, and concluded to run their ships in there and lay till morning, when they would get the breeze and could round the point, as they would not have far to beat.

About 10 p. m., Capt. Bell discovered that the ship was drifting ashore; about the same time, Capt. Gamble, who was about a mile above us, fired a cannon and made a blue light, which was a signal to us that his ship was near going ashore, and in great danger (I will here mention that they had a list of signals wrote out and each one had a copy).

Capt. Bell gave immediate orders for the three small boats to be let down and manned, made fast to the ship with a line, to row ahead of the vessel and try to tow her off; but we found we could not make any impression upon her, as she had got so near the shore that the swells of the sea had full control of her.

At this time Capt. Gamble shot a rocket, which was a signal that he was out of danger. Capt. Bell saw that our ship was nearing the shore very fast, and finding the water too deep for anchorage, he gave orders for a cannon to be fired and a blue light to be made, as a signal to Capt. Gamble that we were in great danger. In a few minutes more the stern of our vessel commenced to thump on the rock bound coast.

Capt. Bell then gave orders for two cannon to be fired, two rockets to be shot, and a blue light to be made, for a signal to Capt. Gamble that we were ashore, and wanted immediate help; who instanter[130] sent to our help his first mate with two boats well manned. They hitched on with our boats and tried to tow her off, but all to no purpose; the Capt. then gave orders to throw overboard some of the cargo to lighten the stern of the vessel, as he was afraid the rudder would get unshipped. While we were throwing over cargo, she swung round broadside on the shore, where she lay perfectly at the mercy of the swell, which was dashing her against the rocks.

As she struck very heavy in the centre, the Capt. saw something must be done or she would break in two; he therefore sent to the Burlington and got a kedge, (a small anchor) made it fast to a hawser (a large rope) took it out from us the ships’ distance and let it down in 270 fathoms[131] water; made the other end fast to the capstan,[132] and commenced to heave and thereby threw her bow off so that she did not strike so hard in the centre; she lay in that position until day light, when the tide commenced to ebb, and the stern swung off.

The night was dark, and not a breath of wind, otherwise she would have gone to pieces in a very few minutes. At day light it was still a calm, when the two mates, the doctor, the carpenter, Elder Dew[e]y and myself went on shore. We found the land densely timbered, plenty of cocoa nuts, some few berries and large numbers of monkeys, who showed off their gymnastics among the trees; we also saw droves of wild hogs.

While we were traveling in the woods, we came to a wet marshy place, and could discover marks of the feet of the lion and the tiger; having no weapons of war with us, we concluded to beat a speedy retreat.

About 1 o’clock p. m., a good breeze sprung up; we made sale and steered for the point, and rounded it at 4 p. m. While we were beating to round Kenneeoongan point, we crossed the equator twice in each 24 hours; once when we beat up in the day time, and once when we drifted back in the night; the heat of the sun was almost unendurable.

A few day[s] after, she run upon a coral reef, causing a portion more of her cargo to be thrown into the sea to lighten her, so that she could be got off. I will here mention that there was scarcely a day during the passage along the coast of Borneo but what we saw reefs or shoals, consequently had to keep a boat ahead sounding; we sailed nearly three thousand miles in an open boat steering, rowing or throwing the lead, and the sun hot enough to bake one’s brains.

On the evening of the 24th we went ashore on Borneo with our Capt. and six seamen accompanied by Capt. Gamble and eight of his men, we saw some natives but they would not come to us, on our return to the vessel we found a fine lot of turtles but their shells were so hard that we broke our spears and did not get many.

March 26th, —while we were ahead sounding, a shark about 20 ft. long came up to the boat, and made a lounge at the man who was throwing the lead, he saw it in time to throw himself down in the boat, when it struck one of the oars with great violence and nearly capsized the boat.

On the 31st the captains thought they had got out of the reefs, as they were in an open sea and neither reef nor island in sight, they therefore concluded to give the men rest and not send any boats ahead. In the evening Capt. Gamble ran his ship on to a reef when under good headway; on seeing the reef he immediately let go his small anchor thinking it might drag along and not bring up the ship so sudden, but the cable broke and hence to him the anchor lost. He then let go one of his large bower anchors which stopped her just in time, as she would touch occasionally when she rocked.

Our captain did not see the reef until the ship touched, but she was under such headway that she went over it although she bumped several times very hard.

April 2nd we lay becalmed between Borneo and several small islands, when a number of small boats made their appearance in various directions and continued to increase until they numbered over one hundred; they were gathering in towards us and from their movements we believed they intended giving us battle and taking our ship if they could; Capt. Bell became much alarmed as Capt Gamble with his ship was several miles ahead.

He then gave orders for the cannons to be loaded with shot, and all the fire arms on board to be put in readiness, also that the cook should fill his boilers with hot water and grease; we had everything ready and waiting their approach, when a little wind sprung up and increased to a stiff breeze when we soon left them and sailed close alongside of the island of Gai, and in the evening came to anchor near the shore of Borneo; during the night we saw large fires on the shore and heard the natives ‘hollowing, yelling and making a tremendous fuss.’

On the 4th in the after part of the day there was no wind, we went with Capt. Bell and 6 seamen to the “Burlington” to fit up for an excursion on shore; at 2 p.m. we started, being accompanied by Capt. Gamble and 8 of his seamen, all well armed; shortly after reaching the shore we saw some natives but they seemed afraid and run from us, we walked along the shore for several miles and collected some very fine specimens of coral and shells.

On the 7th of April we lay becalmed between the islands Tuscany, Toquet and Paggonet. We went ashore with Capt . Bell on the latter island; though it had a fine appearance, it was uninhabited, well timbered but very little game; we saw hundreds of turtles but they were very wild; the captain struck his 12 feet long spear into one of them, but it darted off with spear and all.

While we were in the Selebecean sea near the entrance of the straits of Banghey we had sailed for 2 days without seeing a reef or finding anchorage. The captains were in hopes we had got through with reefs and did not send a boat ahead to sound.

On the night of the 11th of April, as pleasant a moonlight night as we could wish to see in a tropical clime, we were sailing with a firm breeze at the rate of 7 knots an hour, the captain was on his lounge on the poop deck,[133] the officers and ourselves were listening to the sweet strains of the violin as played by the third mate, the sailors on the forcastle[134] were singing songs, and all was mirth and glee, thinking we had got through with pulling oars and heaving the lead. All on a sudden the ship ran into a reef, and as the water shallowed gradually and the coral alive and soft, she fastened herself as firm as if she had been in the stocks; when she struck, it was most terrific and not unlike the shock of an earthquake.

The captain immediately gave orders for two cannon to be fired, two rockets to be shot, and a blue light to be made as a signal to Capt. Gamble (who was about a mile to the windward) that we were aground and wanted immediate assistance; he bore down towards us when Capt. Bell sent out a boat and requested him to come and anchor near the stern of our vessel as we had sounded and found the water 7 fathoms deep; he came to anchor about a cable length from our ship, we then passed two nine inch hawsers from his foremast to our capstan and windlass[135] and commenced to heave but without effect, then passed two hawsers from our middlemast[136] to their capstan and windlass; we could not move her, but dragged the anchors of the other ship.

The captain then judged it impossible to get her off without lightening her cargo; he then called his mates and took a survey of the ship and commenced to throw over cargo and continued until we threw out nearly all on board, when all of a sudden she slid off and swung round.

Bales of cotton and other goods could be seen floating in every direction. The next day we made sail and steered on our course. On the 13th we entered the straits of Banghey, passed the beautiful island of Mulwally, noted as being the place where the English planted a small colony in the year a. d. 1700, who were all massacred by the Malays.

At 1 p.m. we were sailing opposite the island of Banghey. Capt. Gamble having only a few days’ supply of water on board, wished to go on shore on that island to obtain as much as would last him until he reached China.

Mr. Ausburg gives an account of a stream of fresh water flowing from that island into the straits, at which place he got a supply for his ship in the year 1700. We came to anchor near Banghey point where the stream was said to be, when each sent a boat in search of it; we found the mouth of a small brook, the water of which was quite saltish. The first mate (Mr. Miller) who had command of our boat would not go farther up the stream for fear of the natives; as Mr. Ausburg gives an account of a party of Dutch being massacred there while getting water.

We returned to the ship and reported what we had discovered; the next morning Capts. Gamble and Bell with 2 boats manned with 10 men each, well armed started to explore the stream, we ascended it about three fourths of a mile, when the water became so shallow we could go no further with our boats, we saw native tracks along the banks and passed several boats in which were some cooking utensils and other family necessaries, which seemed to us as if the natives had just fled.

We left a party to guard the boats and ascended the stream one mile farther on foot before we came to fresh water, when it was so shallow we could not go farther with our boats even in high tide and the brush so thick it would be impossible to get our casks up to the water; we then concluded it could not be the stream spoken of by Mr. Ausburg; we returned to the ship and after taking some refreshment we cruised along the shore but could find no stream, it was then conjectured it might be on the other side of Banghey point; during the night the natives came down on the beach in hundreds, howling and yelling in such a terrific manner that the captains gave up the idea of exploring farther.

Capt. Bell thought he could spare Capt. Gamble some water by putting his men on short allowance and make shift with what we had.

We made sail and steered on our course passing the island of Tonier, and about 1 p.m. sailed into the China sea; all hands were rejoicing, thinking we had got out of trouble, but we had not gone far when the Burlington who was ahead run into a sand bank, they fired a cannon and made a blue light to let us know he found bottom again and then raised signals for Capt. Bell to keep to the leeward, which he did and passed the bank; as the wind was blowing pretty strong, Capt. Gamble put on all sail and flung the yards aback, and as the waves and swells would occasionally raise her, he succeeded in backing her off and in a few hours were under way again.

I may here mention that the charts that they had was of little account. The captains believed that many of the reefs had grown since the charts were made. If we were afraid of reefs, sand banks and howling of natives before, we had now to encounter what was more terrific, a “Tiphoon” (a dreadful hurricane)[137] while in the China sea; it is impossible for me to describe the fury of the elements; they were truly awful and terrific, it seemed as if the great deep above and below were about to unite.

The captain being acquainted with these storms which frequent the tropical regions, made preparations for it, by sending down the top yards and masts, and as it was she lay on her side with her bulwarks under water for 36 hours while the waves ran mountains high, oft times dashing themselves over the vessel, and as she was very dry and open on her top side caused by the great heat of the sun, also had received much injury while on the passage, she leaked so that the pumps had to be kept constantly going to keep her afloat, and when the storm abated there were between 4 and 5 feet of water in her hold.

It appeared truly miraculous to all on board that she ever rode the storm. A number of vessels were lost in that sea during the same gale, but through the distinguished favor of our heavenly Father, on the 30th April we beheld the coast of China, and on the 2nd of May came to anchor before the town of Macoa.[138]

{To be continued.}

Chauncey W. West to the Deseret News, n.d.[139]

Macoa is a Portuguese town, and from the sea has an attractive and delightful appearance. We here got a Chinese pilot and on the 3rd of May steered for the mouth of the Canton we came to anchor for the night in Macoa bay, with hundreds of Chinese fishing boats in sight. On the evening of the 4th we came to anchor near the mouth of the river between two high hills, on which were China and Saractars forts each mounting two hundred guns.

On the morning of the 5th we entered the mouth of the river, passing fourteen forts within the first four miles. A more highly cultivated and more beautiful country I never saw than that along the banks of the Canton many of the hills bordering the river flats being cultivated to their summits.[140] The Chinese seem to think it a small affair to carry water in buckets to irrigate their crops on these hills, or to transplant a few thousand acres of rice. On the 6th of May we came to anchor in front of the city Wampoa,[141] the ship’s place of destination. Two of the ships company we convinced of the truth; they intended to emigrate to the mountains as soon as they returned to England and got discharged from the ship.

The climate and the great heat of the sun during the passage impaired the health of Elder Dew[e]y, as also that of the capt. who got worse the day we landed at Wampoa, and in a few days he was taken to the hospital at Hong Kong where he died. On the 7th we went to the English Consul to get our discharge from the ship, Capt. Bell being unable to attend to it. After giving it, the Consul told us that we must not go on shore, or we would be taken up and put in the Choca (prison ship).

We asked him the reason. He said, “the sailors and men from ships who went on shore generally got drunk and beat and knocked the Chinamen about, which caused the Consul and ship masters a great deal of trouble,” and remarked that “only a few weeks ago a ship’s crew went on shore and were half killed by the natives.[”] This we had reason to believe was the case, for we saw the bodies of several Europeans floating about in the river.

We showed him our Gubernatorial recommend and United States passport, at which he seemed considerably astonished and said, “I beg your pardon a thousand times, I thought you were queer looking sailors, and what astonished me most is that you are in possession of such credentials and came before the mast, the reason of which I wish to know.”

When we entered into the particulars of our mission he became uneasy, and it was evident that he wished the conversation to close, and as some shipmasters came in about this time he took the advantage, excused himself and left, but not without learning who we were.

In the afternoon we went on shore and traveled through and nearly round the town, and truly it was a picture of social degradation, to say nothing of the inhabitants, whose immoral practices are too low to be described. They were in a great state of excitement about the revolutionists,[142] fearing every day that their city would be attacked. We went on board of ship to stop for the night, as we could not find a place on shore that we considered safe.

May 8th, we fell in with Capt. Dible, of the barque Hiageer, who said his vessel would sail for Hong Kong in two days from that time, and we could have a passage. Capt. Bell gave us liberty to make our home on board his ship until Capt. Dible should sail.

We got a Saupan[143] (a boatman) and went up the river two miles to Bamboo town, which is built mostly on the water, the buildings resting on boats or spiles. Our pilot took us round to the back of the town among the gardens and rice fields. While there a quarrel commenced between several Chinamen who, when we supposed they had exhausted all their strength in words (for they yelled like hyenas), caught each other by their cues with one hand and commenced to unmercifully beat one another on the head with stones cutting great gashes in their heads from whence the blood ran profusely.

When they had fought until some of them were nearly beaten to death, so that they had to be carried off the ground, some other Chinamen interfered and separated them.[144] While we were returning we observed in the end of the boat a little appartment partitioned off in which was a light burning; we asked the boatman why he had a light burning there, he told us that it was his josh-house and that he kept the light there so that josh could see.[145]

He opened the door and we saw a light burning in the centre, behind which stood a little wooden god on a bench, and before and around it were placed some rice, curry, fish and fruits of various kinds, and a bowl of tea. He said that josh came every night and extracted the best of the articles of food, and that he gave him a fresh supply every morning. We asked him if josh was their god; no, he said their god was so good he would not hurt them, but josh was very bad and all the same as our devil, and that they had to do every thing to please him so that he would not hurt them.

In the evening we saw two very long narrow boats with nice silk flags inserted at each end; the boats were filled with men as close as they could sit, each having a paddle which they used with great dexterity, striking all at once. At each stroke came a hearty grunt from every one of them; they propelled the boat with the speed of a swift horse. At each end stood a man beating a drum. We asked a native what they were doing; he said they were making prayers to josh.

It is a common thing through the whole day and night to hear the firing of cannon and guns, and making of various noises, to please josh as they say. When they launch a boat, start on a voyage to sea, or part with a friend, they fire guns and bundles of fire crackers, which they sometimes keep cracking for hours, that they may have good luck, and their friends be blessed and not troubled with josh. When a ship leaves with Chinamen for California, one would almost think by the noises that he was near Sebastopol.[146]

On the 10th we took passage on board the barque Hiageer, Capt. Dible master, for Hong Kong, and had a pleasant passage. The capt. was very kind to us. At 4 p. m. of the 12th we entered the bay of Hong Kong, and at 6 p. m. we came to anchor opposite the city, which is situated at the base of an almost barren mountain. It presented a beautiful appearance from the sea, but when close by it appears more obscure and irregular.[147]

On the 15th we went on shore and made inquiries for Elders Stout, Lewis and Duncan, missionaries to that country, and were informed that they had returned to America.[148] We found ourselves again among perfect strangers, and destitute of the means to buy food or shelter; but we had the same God to lean upon for support that we had had ever since we left our home in the valleys of the mountains, for we took not a cent with us. Elder Dew[e]y’s health continued to get worse, and we could find no person to shelter us from the pitiless storm; the only alternative left was to again go on board ship, which we did in the evening.

16th, constant rain and remained on board. On the 17th we moved on shore and stopped at a Chinese boarding house, that being the best we could do. We found the people had but little regard for “Mormonism,” as they called it, or for any other kind of ism but devilism. The word virtue might be expunged from their vocabulary, for their delight appeared to be to wallow in the mire of wickedness and deeds of darkness. Perhaps the inhabitants of the cities of the plains were not much worse.

On the 27th Elder Dew[e]y was taken down apparently with a complication of diseases, fever predominating, and it seemed as if his whole system was a total wreck. In a few days we succeeded in getting the fever broke, which left him very weak.

About this time we became acquainted with a Mr. Jas. Young, a Chinaman by birth, but raised under American influence; he called himself an American, and kept the American Hotel. He was very much of a gentleman in his manners, and we would not have known but what he was an American if he had not told us.

On learning our circumstances, he said we could come and stop with him for a few days, until we could make some other arrangements; we thanked him for his kind offer, and took our trunks to his residence where we received comfortable fare.

On the 6th of June I took passage from Wampoa on the mail steamer Hong Kong, Capt. Williams Master, who gave me a free passage. We heard there was a vessel at Wampoa bound for Singapore, which had come in since we left. There were a goodly number of passengers on board, among whom were several sea captains. On learning that I was a Mormon, the general topic of conversation was ‘Mormons’ or ‘Mormonism.’

A Mr. Lane requested that I would deliver a short discourse on our faith; I told him I had no objections, if the Captain was willing; he asked the Capt., who said he had no objections, if I would preach the doctrine of the New Testament and not make my discourse from the Book of Mormon, or other ‘modern’ books.

In opening I stated that Capt. Williams had requested that my remarks should be in accordance with the doctrines of the New Testament, consequently I would endeavor to confine myself strictly to the word of God, and begged leave to make a request of Capt. Williams and the other gentlemen present that they would believe the few words that I might read or quote from the scriptures of truth, saying that I had found many people in my travels who believed the Bible when shut, but when it was opened and read to them they could not believe it meant just what it read, that it must have a spiritual meaning, hence so many different opinions in the world about the plain and pure principles of the doctrines of Christ.

After speaking quite plainly for some time, I bore a faithful testimony of the work of God in this age. When I had closed, Mr. Lane remarked to Capt. Williams that ‘he wanted a Bible discourse, and he thought he ought to be satisfied, as Elder West had quoted a good portion of the New Testament,’ and asked, what fault do you find with it? ‘None at all.’ I asked him if he had obeyed the Gospel; he said he had, but not exactly in the same order I set it forth, but that he believed his baptism by sprinkling was just as good as immersion.

Mr. Lane said he had been an infidel for 8 years, but he had to acknowledge there were some very peculiar things about the ‘Mormons’ which he could not account for, viz: their great prosperity and increase in numbers against such opposition and persecution, and that their leaders could govern such a mixed multitude gathered from all nations with such perfect order; he said there must be a secret spring somewhere.

At this time we came in sight of Wampoa which broke up the conversation. At 5 p. m. we arrived and I landed, leaving a good impression among those on board.

I went on board of our old ship the Cressy, which was in the dock being repaired. The officers were glad to see me (Capt. Bell had gone to the hospital at Hong Kong) and welcomed me to stop with them while I remained in the place.

The next morning I enquired after the vessel sailing to Singapore, but on seeing the Captain I could make no arrangement for our passage, for want of money.

Chauncey W. West to the Deseret News, n.d.[149]

June 8th, Mr. James Elister of Virginia, who came up on the steamer with me, invited me to accompany him to the city of Canton, saying that it would not cost me any thing. At 10 a. m. we started in a nice saupan boat, having three men to row and a woman to scull.

We rowed up the river with the tide at the rate of six knots an hour; the scenery was truly delightful; the country on both sides, as far as the eye could reach, was clothed with a mantle of green, interspersed with beautiful groves of fruit and shade trees of various kinds. We passed several large forts on each side of the river, also numbers of China Pago des (monuments) which were beautifully built, and were from 150 to 200 feet high; our boatman said that they had stood for hundreds of years.[150] We passed the entrances into thirteen canals leading from the river into the country, in which we could see immense numbers of boats plying to and fro.

At 1 p. m., we came in sight of the city and began to wind our way among thousands of boats, of all sizes and dimensions, laying from 15 to 20 deep almost obstructing the passage, and so it is for 5 miles above and below Canton. At 2 p. m. we landed in the front of the square where the English church stands; it is beautifully adorned with walks, shades and flower beds.

Our boatman acted as guide and took us to a hotel kept by a Chinaman; here we were treated with great respect, and furnished with a private room adorned with great splendor, after the Chinese style. In the evening our pilot conducted us through the principal streets in the city; the buildings are generally three and four stories high, the streets very narrow and thronged with people, nearly all of whom were carrying something from silk and satins to wood, vegetables, fruit, brick and mortar.

At nearly every shop we were importuned to go in and look at their goods, and a dozen or more followed us during our walk trying to get into our good graces by running down other traders, and telling how good and cheap their articles were. The Jews fall far short of the Canton merchants in urging one to trade.

The next morning I concluded to take a walk alone to the English factories, a distance of two miles. I had not gone far before I was surrounded by a crowd of Chinamen who followed me nearly there and back, talking constantly and urging me to trade. On my return I learned that our guide had gone out in search of me, and the landlord said it was a wonder that I got back alive, that it was not safe for an European to travel through the city alone, even in the middle of the day.

After breakfast we visited the markets and several other places of public resort; there appeared to be a great excitement and confusion among the people, which our guide said was caused by the news that the rebels were approaching the city, and would probably attack it that night or next morning.

At 3 p. m. we left Canton and arrived in Wampoa the same evening. When I extended the parting hand to Mr. Elister he gave me $2, and accepted some pamphlets, which he promised to peruse with care and lend to his friends. I again went on board the Cressy, which had come out of dock, and was informed by the officers that they expected to sail for Hong Kong the next day and I could have a passage.

The next morning, about 8 o’clock, we heard a tremendous cannonade at a town about two miles distant on the side of one of the canals, and soon saw the inhabitants running across the fields; in a short time the whole town was in flames. We were informed that the inhabitants had refused to pay tribute, and the government had sent her Mandarene boats to destroy it.[151]

At 5 p. m. we sailed for Hong Kong where we landed on the afternoon of June 12. I found Elder Dewey’s health about the same as when I left him; he had a severe attack of ague[152] and fever, but had got the chills broken; Mr. Young had been very kind to him. On the 14th I had a conversation with Mr. Miller, who succeeded to the Captaincy on the death of Capt. Bell, and he said we could come on board and remain while his vessel was in port; I thanked him kindly for his offer and returned to Mr. Young’s and talked with Elder Dewey, and we agreed to go on board next morning, as we thought it would be more healthy on the water.

On informing Mr. Young that we were going to leave, he said, as it was Saturday, it would be better not to go on board until Monday, that we were welcome to stop and urged us much to do so. He had been so kind to us that we did not like to go against his wishes and concluded to remain.

The next day (Sunday) passed very dull, and about 4 p. m. we concluded to leave our trunks, go out to the vessel and have a little chat with Capt. Miller. We informed Mr. Young of our intentions, but he said we had better remain until after supper, which would be ready in the course of an hour, still we felt impressed upon to go. On reaching the vessel we found Capt. Miller and had a pleasant interview.

The next morning we were informed that Mr. Young’s house had fallen down, and on going ashore for our trunks (which we found among the ruins) we learned that in about one hour after we left, while all were at supper, a large rock broke loose from the hill above the house, rolled down and struck the lower story, bringing it down with a crash and covering the inmates in the ruins; some were killed and all more or less injured.[153] Shortly after getting on board Elder Dewey had another attack of chills and fever.

On the 25th a vessel came in on its way to Singapore, but we could make no arrangements for a passage. The ship we were then stopping in was about ready for sea and Elder Dewey’s health was still failing, and, as we both thought he would not regain his health in a tropical clime, after fasting and prayer to know the will of the Lord, we felt that the Spirit dictated that it was our duty to return to America.

The barque Hiageer, Mr. Dibble, master, with whom we came down from Wampoa, was chartered to take Chinamen to California. On seeing him he proposed taking us for one hundred dollars each, payable in San Francisco; being from one third to one half less than the common price for a passage.

The second night on board I dreamed that the vessel was wrecked, and that I saw the crew and passengers in great distress. The next night I twice had the same dream, and a night or two after Elder Dewey dreamed the same thrice. We then became convinced that it was our duty to leave the vessel, but how to get off we did not know; we felt averse to speak to the captain about leaving, for he had been very kind to us and had turned away other passengers who wished to go with him; but the longer we remained on board the more we felt impressed that it was our duty not to remain in the vessel.