Benjamin Johnson and the Sandwich Islands Mission

Reid L. Neilson and R. Mark Melville, "Benjamin Johnson and the Sandwich Islands Mission," in The Saints Abroad: Missionaries Who Answered Brigham Young's 1852 Call to the Nations of the World, ed. Reid L. Neilson and R. Mark Melville (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 135–170.

Historical Introduction

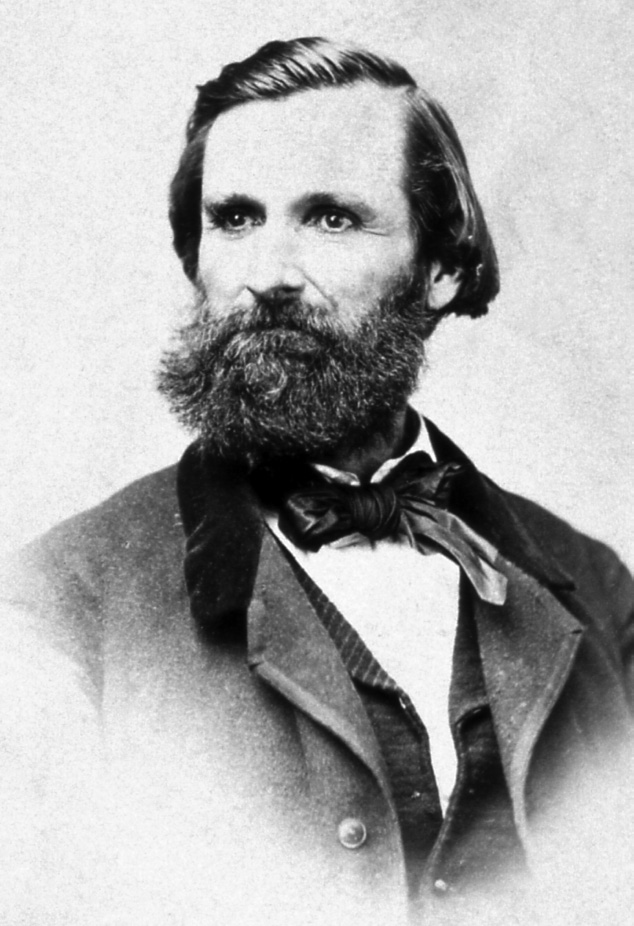

A month and a half had passed from the special August 1852 missionary conference before Benjamin Johnson learned that he had been called on a mission to the Sandwich Islands.[1] “At first I could not believe it, but when I found it a reality I was dazed!” he later reflected. “How possibly could I be prepared in ten days—or even in ten months—to leave my familys, now separarated 100 miles; . . . and unsettled business almost every where . . . all to be disposed of or thrown away! . . . Reason said—‘No, you cannot go; it is not just to require it under such circumstances.[’]” He had three wives and eight living children, and only four years after his arrival in territorial Utah, he already held interests in several business ventures. However, a sense of religious duty had enabled him to pack up and head west in 1848, and this same sense of responsibility prompted him to make tremendous sacrifices and accept the mission call. “I told the Lord I would now commence, and wanted His help.”[2]

Benjamin Johnson’s Early Life, 1818–52

Benjamin Franklin Johnson was born July 28, 1818, in Pomfret, New York. In 1830, Benjamin’s older brothers brought the distinctive message of the restored church of Jesus Christ to the Johnson family. Although Ezekiel Johnson, Benjamin’s father, objected to this newfound religion, Benjamin’s mother, Julia, embraced the teachings, and the family moved to Kirtland, Ohio, the locus of the Latter-day Saints, in 1833. Benjamin was baptized in March 1835 at the age of sixteen. Shortly thereafter, Johnson had his first proselytizing experience: after his sister was seemingly miraculously healed of a hip injury, he returned to his hometown to preach to his former neighbors, but they had no interest. Benjamin followed the Latter-day Saint migration from Ohio to Missouri and then to Illinois, where he was called on a mission to Canada in 1840. After his mission, he returned to Kirtland, where a few Saints still resided. He relocated to Ramus, Illinois, about thirty miles east of Nauvoo, in 1842, where he became a member of the Council of Fifty[3] and was taught about plural marriage from Joseph Smith.[4]

Johnson departed from Nauvoo in 1846, stopping in Garden Grove, Iowa, and later in Winter Quarters, now in Nebraska. In 1848, he joined the Willard Richards company to travel west to the Great Salt Lake Valley. When Johnson and his family arrived in Salt Lake City in October 1848, they found the situation dire, as the crickets of the previous summer had decimated the crops. To support his family, Johnson established a harness shop and a drugstore in the city. He became involved in local politics, including Utah’s territorial legislature. In 1851, he accompanied Brigham Young on an expedition to southern Utah. Young asked him to make a settlement at Summit Creek, about seventy miles south of Salt Lake City, so Johnson sold his city home and relocated to Summit Creek (now Santaquin)[5] and also nearby Salt Creek (now Nephi),[6] Utah. Johnson retained the ownership of his shops in Salt Lake and also took up a job delivering mail. With all these mercantile, political, and colonizing duties, Johnson felt he did not have the time to attend the special conference session of August 1852. When he later learned that he had been called on a mission to Hawaii at that meeting, he only had ten days to wrap up loose ends of his property and businesses and make preparations for his family.[7]

A History of the Hawaiian Mission

In 1849, Brigham Young sent a few Latter-day Saints to California to join prospectors searching for gold.[8] In 1850, Apostle Charles C. Rich, who oversaw the Saints in the San Bernardino, California, area, asked eleven of these gold seekers, with Hiram Clark as their president, to take the gospel message to the Sandwich Islands.[9] After arriving in Honolulu[10] in December 1850, these elders spread out to labor on the islands of Oahu, Hawaii, Maui, and Kauai. On Maui, George Q. Cannon realized that he would be limited if he tried to teach only the white, or haole, population, who were not interested in the missionaries’ message and who were outnumbered by native Hawaiians. Therefore, he began to study the Hawaiian language so that he might preach to the native population. He began to have success throughout Maui. Other elders, however, were not so optimistic about their missions, and by April 1851, half of the missionaries had left the islands.[11]

In August 1851, three more missionaries arrived in Honolulu as reinforcements to the Sandwich Islands Mission. By the end of 1851, Cannon and James Keeler had established the church throughout Maui, and William Farrer[12] and Henry William Bigler[13] were having moderate success on Oahu. In early 1852, George Q. Cannon began translating the Book of Mormon into Hawaiian in collaboration with Hawaiian convert Jonathan H. Napela, though it would still be two years before the translation was complete. Some of the converts began to depart from their new faith, but still the church continued to grow throughout 1852.[14]

Johnson’s Mission to Hawaii, 1852–55

Benjamin Johnson was one of nine missionaries called to the Sandwich Islands in August 1852. The other eight were William McBride, an Ohioan convert of 1841; Nathan Tanner, a former Zion’s Camp[15] member who had been baptized in 1831; Thomas Karren, an 1842 British convert who had been in the Mormon Battalion;[16] Ephraim Green, an 1841 convert who helped discover gold in California in 1848; James Lawson, originally from Scotland and baptized in 1844; Redick Allred, a Mormon Battalion alumnus who had been baptized in 1833; Reddin Allred, the twin brother of Redick who had also been baptized in 1833; and Egerton Snider, born in Canada and baptized by 1837.[17] This group joined the missionaries traveling to Australia, India, and China as they made their way south through Utah Territory on their way to San Bernardino, California. The Hawaii missionaries sailed from San Francisco and arrived in Honolulu on February 17, 1853, where they were met by Philip B. Lewis,[18] who had assumed duties as president of the mission, and found six hundred converts already on the islands.[19]

For the missionaries, the Hawaii of the 1850s was not the paradise of its modern-day reputation, and they faced significant challenges. Polygamy was an unpopular doctrine and elicited considerable disdain from other Christian clergy. Latter-day Saints, on the other hand, criticized the earlier Protestant and Catholic missionaries for doing an inadequate job of teaching the natives the benefits of Western education and agriculture. The Latter-day Saints tried to establish schools for the Hawaiians, but due to cultural differences and a declining population, these schools did not fare much better than their earlier counterparts. Worst of all, the native population plummeted as a smallpox epidemic swept over the islands.[20] Johnson and his companions saw this as an opportunity to manifest the gift of healing that they believed was present on the earth;[21] not heeding quarantine laws, they administered healing blessings, traveling from smallpox victim to smallpox victim, without being vaccinated themselves.[22]

Not everything, however, was so grim on the islands. A few thousand joined the ranks of the church in the Pacific. By October of 1853, Johnson had earned the trust of his fellow missionaries, and the mission presidency placed him on committees to fulfill some of the mission’s objectives, including purchasing a press to print the Book of Mormon translation and helping with the less-than-successful church schools.[23] He eventually became first counselor in the mission presidency.[24] One significant endeavor of the mission was to establish an island gathering place for the Saints of the Pacific. Rather than require all the converts to gather to Zion in Utah, church leaders decided it would be wise to create a smaller community there on the islands. Johnson was part of the group that sought a suitable location. Haalelea, a local chief, offered to donate his lands on the island of Lanai[25] to the church, so Johnson and fellow missionaries Ephraim Green and Francis Hammond scoped out a spot to establish a settlement. During the summer of 1854, they found a spot in the Palawai Valley and named it the Valley of Ephraim. Some Saints moved to the valley to settle and farm. Johnson witnessed the beginnings of the colony at Lanai, but he suffered from an illness, and he departed from Hawaii in January 1855. He arrived at his Utah home on March 26.[26]

Additional Church Service, 1855–1905

Just as Johnson had spent his two years in the Sandwich Islands ministering among the natives of Hawaii, when he returned home, he found himself frequently interacting with the natives of Utah. During his absence, his homes at Summit Creek had been burned to the ground by Indians during the Walker War of 1853–54.[27] As he reestablished homes and farms at Santaquin (the new name for Summit Creek) and nearby Spring Lake, he earned the respect of local Indians by offering them food, protection, and other gifts, even though these were times of turmoil.[28] Johnson even purchased and adopted some Native American children who had been captured by the Ute tribe.[29] In the early 1870s, he and his siblings attempted to build a settlement in Kane County, Utah. After this would-be town, named Johnson, was unsuccessful, he returned to Spring Lake, where he was appointed as a bishop.[30]

In 1882, church leaders asked Johnson to move from Spring Lake to help establish a colony in Arizona. Church President John Taylor then asked him to build up settlements in Mexico to enable polygamists to avoid federal prosecution. Johnson relocated to Tempe, Arizona, that year, and while he never permanently settled in Mexico as had been planned, he frequently visited the country.[31] On one occasion in late 1884, he was part of a group sent to preach to the native Yaqui tribe of coastal Mexico. “The Yaquis in physiognomy, dress and mode of living are so like the Hawaians that here on the sea coast I could almost fancy myself again upon the islands,” he wrote.[32] After years of hiding, in 1888 Johnson was finally fined seventy-five dollars in Arizona for practicing polygamy. Though he often visited his former homes in Utah, Johnson mainly dwelt in Arizona, where he served as a local patriarch in the church. He died at Mesa, Arizona, on November 18, 1905.[33]

The other eight missionaries sent to the Sandwich Islands in 1852 all returned to settle in the Mormon Corridor[34] of Utah and Arizona. William McBride went to California in 1854 to try to get a printing press; he returned to Utah in 1855 and died in Salt Lake City in 1895.[35] Nathan Tanner left Hawaii in 1854 and served a mission to the eastern United States in 1869; he died in Granger, Utah, in 1910.[36] The other six left Hawaii in 1855, just as Johnson had done. Thomas Karren returned to Lehi, Utah, for the rest of his life, dying in 1876.[37] Ephraim Green returned to Hawaii for another mission from 1865 to 1868, when he helped establish the Latter-day Saint settlement at La’ie; he died in Rockport, Utah, in 1874.[38] James Lawson likewise served another mission to Hawaii from 1865 to 1867; he died in Salt Lake City in 1912.[39] Redick Allred served in several ecclesiastical callings in Sanpete County, Utah, before dying in the county’s town of Chester in 1905.[40] Reddin Allred spent many years in Tooele, Utah, after his return and died in Thatcher, Arizona, in 1900.[41] Egerton Snider died in Salt Lake City in 1867.[42]

Benjamin F. Johnson’s Family Life

When Johnson left on his mission, he was married to three wives. He married Melissa Bloomfield LeBaron on Christmas Day of 1841 in Kirtland, Ohio; Mary Ann Hale on November 14, 1844, in Macedonia, Illinois; and Harriet Naomi Holman on March 17, 1850, in Salt Lake City. He also married Flora Clarinda Gleason on February 3, 1846, in Nauvoo, Illinois, but they were divorced in 1849. His first three wives had borne him nine children, eight of them living at the time of his departure.[43]

After receiving his mission call in 1852, Johnson made arrangements for his businesses and farms and moved two of his wives, Melissa in Salt Lake City and Mary Ann in Salt Creek, to join his third wife, Harriet, in Summit Creek. Harriet’s father, Bishop James S. Holman,[44] agreed to “see to [the] family and property.”[45] A year after Johnson’s departure, the Indian uprising referred to as the Walker War began in the area. For safety, the entire settlement of Summit Creek was evacuated, initially to Holladay Springs (three miles to the north) and then to Payson (about six miles north of Summit Creek).[46] After the families moved to Payson, one man was killed and two were injured in Summit Creek, and later, the Summit Creek homes were burned to the ground. The Johnson home and crops were a complete loss.[47]

After this significant setback, Johnson’s wives and children faced the challenges of finding and securing a safe place to live, caring for livestock, and providing education for their children.[48] Mary Ann and Harriet each gave birth to sons, both named Benjamin Johnson, months after he had left, and Melissa’s newborn died shortly after his departure.[49] Melissa wrote about living in a hastily constructed shelter before buying an adobe home and adjoining land in Payson.[50] Despite the trials, they managed to endure their obstacles. Harriet wrote, “I say that we may rejoice in the sacrifice that we have made. We must consider it the greatest blessing that could be bestowed upon ourselves though it looks like a long time to be parted from each other, but we can realize each other’s society which if hadn’t happened we would not have known anything about.”[51]

After returning from his mission, Johnson married three additional wives: Sarah Melissa Holman, Susan Adeline Holman, and Sarah Jane Spooner; and he had additional children with all six of his wives.[52] In 1860, his first wife, Melissa, died in childbirth.[53] His relationships with his wives were not always harmonious; Mary Ann nearly divorced him in the 1860s.[54] When he moved to Arizona in the 1880s, his five remaining wives chose not to accompany him, and his relocation and subsequent visits to Mexico caused some of them to feel neglected. In return, Johnson felt that his wives treated him coldly.[55] Even so, during the twilight of his life, he reflected, “I can believe that to some plural marriage was a great cross. Yet I cannot say so from my own experience, for altho in times that tried men’s hearts, I married seven wives . . . and there is not one of my children or their mothers that are not dearer to me still than life.”[56]

Source Note

Benjamin Johnson began writing a retrospective autobiographical manuscript in 1885 “to record the principal events of my life. From this duty I shrank for years and tried to excuse myself from it. But a voice within my soul has continually urged me to this effort, which has so long appeared onerous. But now, feeling I have no other farther excuse I commenced to write a Life review from my early childhood.”[57] Johnson worked on the history off and on until his last entry in 1896. “A Life Review by Benjamin Johnson” is housed at the Church History Library of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; it has been published a few times, including as My Life’s Review: The Autobiography of Benjamin F. Johnson (Provo, UT: Grandin Book, 1997). We have herein reproduced pages 132–89, the portion of his autobiography that relates to his mission to the Sandwich Islands as it appears in the original manuscript. He describes his journey to California and then to Hawaii, preaching on the islands, the smallpox epidemic, finding a place for settlement on Lanai, and the journey back to California and then Utah. For space considerations, we have omitted portions of his writings that are more tangential to the overall story of the mission.[58]

Document Transcript

Benjamin Johnson, “A Life Review by Benjamin F. Johnson”[59]

At Salt Lake city July 10th 1852 Melissa B.[60] gave birth to our daughter Frances Bell,[61] and I had taken a boy—Orson Murray[62]—to raise. His father was dead, and his mother and grandfather gave me a writing to ensure my keeping him until 21 years of age. He was a good boy, and we adopted him in our hearts as well as in our home; and business so increased that at the time for October Semi-annual conference I had so much to do and look after that I could not go, and attend Conference.

But the Lord’s ways are not as man’s ways;[63] and things appearing of so much consequence to man is of no worth to him. And so it proved; for about Oct. 10th I received notice that I was called by the vote of General Conference to a Sandwich Island Mission, and that I had until the 20th to prepare for the start. At first I could not believe it, but when I found it a reality I was dazed! How possibly could I be prepared in ten days—or even in ten months—to leave my familys, now separarated 100 miles; with a U.S. mail contract,[64] and unsettled business almost every where, from north of the city to Manti.[65]—Then my saddlery, with large bill of merchandise just imported, & drug store—all to be disposed of or thrown away! All this,—and only ten days to rent out my farms, gather up my family, dispose of my mail contract, settle all business, and get ready for a start. Reason said—“No, you cannot go; it is not just to require it under such circumstances.[”] Three wives with 8 small children—to be increased by two in my absence; and what a loss in means! Such a needless sacrifice! And then—to go among barbarians in a land of license! It was terrible for one so weak as I. “But what shall I do?[”] I asked myself; and Faith answers by asking—“from whom did you receive wives and children—farms and houses—goods and cattle? Who redeemed you when you were hopeless of life and name upon the earth? To whom do you owe all you are, all you possess, and all you hope for, but to God? Then why hesitate? when you have professed to be willing even to die for the truth of the gospel?” I could see but little choice between the grave and my mission. But in gratitude to God I said “With the Lord’s help I will go; and the cord I cannot untie that holds me from my duty I will cut loose from; for go I will, with the Lord’s help.[”] I told the Lord I would now commence, and wanted His help.

I started to the city to settle business, and find some one to take my farm at Salt Creek, to dispose of mail contract, Saddlery, Drug Store &c. Faith and Hope grew in my heart. In Salt Lake City those I wished to see on business were the first I met, all dues to me seemed ready, and men I owed and not ready to pay were not pressing; Men living in the north I had no time to visit I met on the street; and the first men I met when looking for renters for my Salt Creek farm were brs. Vickers[66] and Udell,[67] with whom I at once closed an arrangement to take my farm for the term of my absence.[68] . . .

But the idea of leaving my wives and children—more dear to me than life—and for so long a time—Would I ever see them again! A long, tedious and dangerous journey of twelve hundred miles to the coast; then up the coast by sea some 800 miles, and then near 3000 more across the ocean to the Islands![69] . . .

In conversation with Prest Kimball in regard to immoralities of those lands, he gave me a key that I would not forget. I spoke of those who had fallen upon their missions, and expressed a fear for myself. He asked how many wives I had? I said “Three.” He asked if they were good, praying women? I said yes. “Well,” said he, “no man ever did nor ever will fall that has three good, praying women to hold him.” This, as a key of knowledge I wish to record for the benefit of my children.

Our mission was to carry to the world the revelation on plural marriage, to advocate and defend it. We were told to go without purse or scrip, and on arrival in California to sell our teams and send the money home.

I now started teams to move Melissa B. to Summit and to bring Bros. Vickers and Udell to Salt Creek, and by my suggestion Br. Holman was ordained Bishop at Summit. He was also to see to my family and property. Melissa B. and Mary Ann[70] were now moved to Summit and <all> were to remain together there during my absence. I now took an inventory of the improvements on land, grain on hand, houses, horses, oxen, cows, sheep, wagons, stock in trade, farm tools and implements that I left at Summit and Salt Creek to the amount of over $7000.00 after all debts were paid, taking one light spring wagon and a valuable span of horses with me.

On the 22nd of October I was ready and waiting for company, who came and passed, as all were to meet at Salt Creek and start from there on the 24th. . . .

Br. Alexander Badlam[71] who by Prest Young’s arrangement was to accompany me to San Barnardino, was with me, and the evening of Oct. 23d we arrived at Br. John Vickers at Nephi, (Salt Creek) and as the company had been already organized, came in as the last wagon of the train, but I felt to be satisfied, confident that through the providence of God I would occupy the place that would be according to his will.

We held meetings on our way through the southern settlements, we being over forty in number, appointed to China, Australia, Ceylon, Hindostan, Africa and perhaps other points within the Indies. To the Sandwich Islands there were nine, namely:—William McBride, Nathan Tanner, Thomas Karren, Ephraim Green, James Lawson, Redick and Reddin Alred, Egerton Snyder and B. F. Johnson. . . .

From Parowan[72] we proceeded pleasantly down the Santa Clara.[73] . . .

We were a little short of food, but did not suffer much, and arrived all well, in San Bernardino, and found homes for a time among friends. . . .

At San Bernardino we remained near 3 weeks to recruit our teams and dispose of them, and made my home at Br. Norman Taylor’s, by whose two wives, Lorana and Lydia I was treated with great kindness, making all needed clothing for my further journey.[74] I sold my outfit for over $300.00 lent $100.00 to Br. Badlam, and arranged to send to my family by one of the brethren soon to return to Salt Lake whatever I might have left after paying expenses to San Francisco. . . .

From San Bernardino it is about 80 miles to San Pedro on the coast, to which place the brethren of San Bernardino shipped us in open wagons, and the first night—oh, how it did rain, and having no shelter but our blankets, and the last of December, we were soaking wet and miserably cold. The next night we suffered nearly as much; but on the following night, within six miles of San Pedro we stopped at a Spanish Ranch. The proprietor being one of the party of whom the San Bernardino ranch was purchased by Apostles Lyman and Rich. Here we hired a large room at ten dollars per day in which to stay until we could negotiate for our passage up the coast. Here I was appointed with Br. Nathaniel <V.> Jones as agents to negotiate and transact business for the company; and here I began to get an insight into Mexican social and moral life, in a manner I may never forget. . . .

After a short stay here we moved to San Pedro, a small harbor on the coast, Dec. 22d, and here we remained over a week, waiting the arrival of a vessel on which to get passage up the coast. Here we found, also waiting passage, two gentlemen from Boston, physicians, named Williams. The younger was nephew to the other, and he was one of the first known writing mediums in Spiritualism.[75] They seemed refined and cultured, and eminent in their profession. Religion and spiritualism was soon in discussion, and with much assurance they offered to give us demonstrations of power greater than could be found in any religion; and they asked me if I would preside at a meeting if our company would agree to attend, and witness the manifestations of their power, which I agreed to do, conditioned that our company wished it, and the dining hall could be obtained. Being agreeable to the brethren, the room was engaged for the coming evening, and so at the time appointed all were present. There were no opening ceremonies, and as I announced the meeting opened, a feeling came upon me that gave me faith and full assurance that while I exercised my will they could do nothing. I sat while they called for spirits, one after another, until they seemed to exhaust their vocabulary of Spirit names, without answer or demonstration of any kind. At last, chagrined and mortified, they said there was a stronger power present than theirs, whose will had been exercised against theirs, and that under such circumstances they could do nothing; but that they did not regard the man who had placed himself in opposition as a gentleman. I remembered that the Lord had rarely on the earth been regarded as a gentleman. They left the hall mortified and disgusted, and the young man was so chagrined that he rarely spoke through all the time we were together. But at San Francisco, on their arrival, the public journals were soon full of the mighty things manifest through these men, converts came to the islands the following year and made many converts to spiritualism. Some brethren at Honolulu were captivated by it.

But to return. I spent much time upon the shore in admiration of beautiful shells, or from som[e] higher point watching the sportive seal or sea lion, or the spouting whale in its majesty slowly passing in view; with the wonderful sea weed, like forests and gardens, whose fruit and foliage of great variety in shape, these, with the thousand wonders of the deep gave me pleasant occupation until the arrival of the brig “Fremont,” Capt. [John] Erskine,[76] commander, bound for San Francisco, our final point of departure.

Br. Jones and I soon arranged terms of passage for all our party, now numbering 40; and the vessel being limited in accommodations the Captain guaranteed us every facility for comfort in the cabin except the sofa, on which himself would sleep. Upon these conditions we paid passage money and went on board, while he went to Los Angeles for supplies. I was just now afflicted with neuralgia and incipient piles, which tended to greatly weaken and unnerve me. . . .

After ten disagreeable days we landed safely at San Francisco, where we were to raise money to defray expenses to our different fields of labor. But how was it to be done? We rented a house large enough to accommodate all, then, in general council agreed that a Circular Memorial to the people of San Francisco should be written, showing the object of our mission, and ask for donations in money to assist in defraying our expenses. Bros. James T. Lewis, A. M. Musser and Wm Hyde were appointed to draw up this statement memorial, which they zealously strove to do, but did not succeed in a manner satisfactory to themselves and appeared discouraged. Acting then as chairman and sitting by the table, I picked up a pencil and proceeded casually to write as thoughts came to me. One of the committee read the following:—

[“]To all to whom this may come greeting:—We the undersigned, missionaries of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints from Salt Lake City, Utah, to the different nations of the Earth, respectfully represent to the honorable people of San Francisco, that we, like the Apostles of old have left our homes “without purse or scrip,” and are now in your midst waiting a passage to our respective fields of labor. We therefore humbly ask you, in the name of our Master to assist us with means to defray expenses incidental to our journey, and the God whom we serve shall reward you a hundred fold.” He said, “This is just what we want,” and read it aloud, and all agreed that was just what was wanted. I begged the Committee to revise it which they sought to do, but said they could not better it, and asked me to write it over, which I did, carefully. It was given to the brethren, who, two by two, went through the city visiting stores, public houses and business places, to present this memorial and ask for donations. Many responded in small sums of one, two and five dollars; but the amount we must have was not less than six thousand dollars. This was continued for a few days, and having been a member of the Utah legislature I was asked to visit the state legislature then in session in Sacramento[77] and present our memorial and ask for help. I was about to start when Br. John M. Horner,[78] a wealthy L. D. Saint of San Francisco, came and wished us to cease all further efforts to raise money, and said he would furnish us five or six thousand dollars when we were ready to sail. It is but just to say that Thos. S. Williams, who was a member of the Church, gave us $500.00 as also Bros [Quartus] Sparks[79] and others, all of whom later turned away, but gave sums from $10.00 to $50.00. We almost felt to shout “Hosanna” to the Most High.

After 2 weeks pleasant stay in San Francisco, associating with old fri[e]nds, holding meetings, & conversing with many upon the revelation on plural marriage we heard the ship “Huntress” would sail for Honolulu Feb. 2nd James Lambert Master, with whom we arranged for our passage, and went on board, Feb. 1853.[80]

Our passage to Honolulu occupied sixteen days with weather just rough enough to give us the full benefit of sea sickness. Otherwise it was exceedingly pleasant, and rendered so by the Captain’s extreme kindness to us, of which the Lion’s share, through his partiality fell to me, for we had no sooner shipped on board than he came to me with the freedom of an old acquaintance or companion. . . .

On our arrival at Honolulu the Captain’s friendship did in no degree abate, and as he had friends of long standing among the merchants and business men of the city, he took great pleasure in introducing us to them, and in commending us to the public as missionary gentlemen, and so continued until the day before setting sail, when he invited us and insisted on our coming on board with all our friends, to a turtle soup dinner.[81] After a time of enjoyment, before our farewell, he asked us to sing “When shall we all meet again,”[82] which caused a moisture in his eyes, and made us to feel—“God bless our dear friend Capt. Lambert.”

On arrival in Honolulu, which was on Feb. 17, 1853 we found Br. Philip B. Lewis, who was set apart as President of the island mission, occupying rooms with Br. Dennis[83] and his wife, a sickly woman, who died on her way home from the mission, plying her needle for their support, while he with all his soul was studying to acquire the native language. The mission was financially in a scanty and humble condition, as was in many ways manifested by the elders who came from their fields of labor to welcome us. . . .

About this time I felt an inspiration to urge the ordination of natives to the priesthood, to assist the foreign elders in preaching the gospel. In this Prest Lewis and Br. Cannon and others were with me, while others opposed; but no sooner were a few ordained and sent than all objections vanished, for they proved far more efficient than we had hoped. Through them the work spread mightily, and many of the best educated were baptized and soon became efficient auxiliaries. . . .

Native elders now in the field were exerting a powerful influence, and it almost seemed as though all the Hawaian people would become members of the Church; but at this time the small pox was getting its start among them. I had never before seen a case of it, and I had no apparent protection by vac[c]ination; and as they continued to flock to us for ministration, there soon came those in the fever, soon developing the disease, to all of whom we ministered. But so soon as it was really known to be small pox the old missionaries left their flocks and fled. Many of the physicians were too frightened to remain and Br. Tanner with some others left us for Hawaii. The health officers began to gather the sick to hospitals and pest houses, to which the natives looked with terror.

Brs. Lewis, Farrar, and I were still together, in the City, and we agreed that by the help of the Lord we would stand by each other, and stay with the native saints. Unlike the others I had no apparent protection, but I felt I was in the line of duty, and in the hands of the Lord, and that I could not afford to desert my post and leave the native brethren alone in their affliction.

But there were trials before us. As soon as some of the natives began to die with small pox it struck the people as a panic; and being nearly amphibious in their habits, at the appearance of fever they fled to the sea to plunge into the surf,—almost to certain death. This from the first we counselled them not to do, but they would not listen; and before we were aware of it almost the whole native population were sick, dying, or lying dead. Such was the terrible condition of the city that States Prisoners were pardoned on condition they would assist in burying the dead. At first the health officers took them to hospitals or pest houses, and to escape this many fled to the mountains and died in some bye-place. Accompanying Br. Lewis to the hospital at one time to look after some of our brethren, the stench from the dead and dying so overcame me that I was helped from the room to the open air. And going from house to house among the sick we found in yards where perhaps 20 had lived now not a soul alive, while some of the dead were still unburied. Often in one day we used two quart bottles of oil in anointing the sick, for we ministered to all who asked us, feeling they were all our Father’s covenant children. I cannot describe the piteous sights we often witnessed. On one occasion coming to a house where lay upon the mats a man and boy too swollen to be recognized, as we ministered to the man he seemed to revive and tried to talk, and I felt sure it was one of our brethren. I looked around and saw a coat which I knew belonged to one of our dearest friends—a most devoted member of the Church. All the rest of his family were dead and he was nearly gone. And so went most of our dearest and most zealous brethren and friends—our most active help in the ministry—and my heart wept, and my whole soul cried out to the Lord for that poor people, and I was in great affliction, and marvelled that the Lord would permit all his most faithful servants to die, so dear to us, and whose help we so much needed, and I pondered the subject prayerfully until the light of the Lord shone upon my understanding, and I saw multitudes of their race in the spirit world who had lived before them, and there was not one there with the priesthood to teach them the gospel, and the voice of the Spirit said to me—“Sorrow not, for they are now doing that greater work for which they were ordained, and it is all of the Lord.” So I was comforted, knowing that through the Spirit of Elijah the hearts of the children were now being turned to the fathers in the spirit land.[84] Of the 4000 who died in the vicinity of Honolulu some 400 had received the gospel, embracing the most efficient and the very best of the native saints. . . .

At our conference Oct. 6th 1853 a move was made to procure a printing press, for publishing the Book of Mormon and other works, in the Hawaian tongue; and Prest Lewis, Br. Cannon and I were appointed a committee to devise ways and means for that purpose.[85] At the same time I was called upon, with others, to select & negotiate for a suitable tract of land for the gathering of the Saints. Heretofore the mission had been very poor, and it appeared a great undertaking, especially to raise the money necessary to buy a press and material sufficient for the work before us. But with me it was a principle of faith, and according to prediction that means should come into my hands through the blessing of the Lord, to sustain and comfort my brethren, and to accomplish every purpose pertaining to my mission. Thus far the way had been marvelously opened, and I felt strong faith that we would succeed.

Our general conference was held at Waialuku on East [West] Mauii at which near 2000 native members were present, there being 6 or 7000 native saints in the mission. East [West] Mauii embraces about one third of the island, and is one vast mountain rising abruptly from the sea on all sides except landward, and attaining the height of 14000 feet. In the summit is an abrupt chasm about 10 miles in diameter and some thousands of feet in depth.[86] To visit this a party was formed, consisting of Prest Lewis, Brs. Cannon, Hammond,[87] Bigler, myself and others, with horses, mules, asses and jennys, the provisions being furnished by the natives. With some natives for guides we set out, the summit being 15 or 20 miles distant. The ascent occupied nearly two days, and for some miles was gradual, over land which was the richest and most beautiful of any I had then seen upon the islands. Here grew many acres of beautiful potatoes, thousands of bushels of which had in the past been shipped to California, and other markets. They were of a flesh color, smooth, good size, and much like our present “early rose.” I tried to learn if they were indigenous or from foreign lands, but the oldest inhabitants could not tell. Thousands of acres were covered with tomatoes, ground cherries, straw berries, whortle berries[88] &c, and here was the only place I saw where was growing the famed sandal wood—burnt as incense in eastern worship.[89] And here was a branch of the church with their flocks of goats, pigs, fowls &c. who feasted us on our way up and invited us to stay with them on our return, with promise to cook for us a fat goat. The first night brought us up to the frost line, and into the region of rocks, brush, and steep ascent, and to a commodious cave, where we camped for the night. The natives had broiled goat meat and roasted potatoes &c which gave us supper and breakfast, which last was served at break of day. Again we scrambled upward over the few remaining miles before us, which grew steeper and more steep until we were compelled to dismount, lead our mules and pull up by the brush, and there was no intimation to our near approach to the top until we stood upon the very rim of this most awful abyss, almost just beneath us. Here opened to our view a scene sublime, grand and wonderful. Before us was a chasm some thousands of feet deep and 30 miles in circumference, once, to all appearance, the mightiest volcano that ever shook the earth:—where had rolled in majesty not a volcanic caldron but a ten-mile sea of molten fire, which, as we gazed, appeared from our elevation a moving mass and still flowing through a gorge into the sea. But my pen is inadequate to describe the awful majesty of this unparalleled, though now qui[e]scent volcanic crater. And while standing at this great altitude the view stretches away over the mighty deep, taking in all the surrounding islands, which appear but as dots in the watery expanse. And never has any view so impressed me with the majestic greatness of Nature’s God and the smallness of finite man.

Of our descent into and exploration of this awful chasm and the dangers encountered in our exit, as also the many interesting incidents attending our visit and return I must not pause to write. Returned to Makawon[90] on the night of the 16th and stayed with Br. John Winchester[91] in company with Brs. Lewis, Cannon and others. Started in early morning for W[ai]luku, 15 miles, and on leaving the road and crossing a broad sand plain we saw large quantities of human bones, apparently spread broadcast far and near in every direction—a grim and hideous sight. We learned that here was fought the great battle by Kamahamaha 1st through which the Mauii king became his vassal, as also all the other island Chiefes or kings who were conquered by him about the beginning of this century, since which a constitutional kingdom has been created, and recognized by the governments of Europe & America.[92]

The Haleakala Crater. This formation is likely near the location Benjamin Johnson is describing.

The Haleakala Crater. This formation is likely near the location Benjamin Johnson is describing.

Courtesy of Pixabay.com.

From Wailuku we went to Palia,[93] where the natives took us by whale boat 20 miles to Lahaina,[94] from which point the Committee appointed to obtain a location on which to gather the native saints were to cross the Channel and explore the island of Lan[a]i, much of which belonged to our friend Halalia,[95] who, I forgot to say, had offered it to us on easy terms, either for occupation or purchase.

We arrived on the 18th and on the 19th the committee consisting of Bros. Hammond, Dennis, McBride, N[athan Tanner] and myself, with Brs. Cannon and Napela[96] started in a whale boat 20 miles across the Channel. After a tedious passage without wind we arrived about 4 o’clock at Mannetta where were a few native houses and the people had collected upon the beach to receive us. We held meeting, baptized a few, and after an early breakfast the following morning upon fish caught by native Brn. through fishing all night in a heavy storm lest we should go hungry, we started to explore this island, which very few foreigners had ever visited. It is nearly circular in shape, and about 20 miles in diameter, and has been upheaved, a melted, dripping mass of molten rock. On all sides, except at the place of our landing the once melted rock stands vertical for some thousands of feet, and its honey combed sides[97] is inhabited by flocks of domestic pigeons in their wild state, with swallows and sea birds as associates. In ascending this island mountain about one mile was rugged and rocky, but another mile of smooth and beautiful grass covered lands brought us to the summit or rim of a basin or valley which as a concave occupied its whole top; and as we gazed down upon it we were charmed with its beauty. Never had I seen a valley of such symmetry and beauty, and as we proceeded, we found the soil very rich, the only question of importance being the needed supply of water to sustain the population through the dry season. To stay both hunger and thirst we ate the Pabisus, or fruit of a cactus, which is delicious and is much used by the natives. In color it is of a bright red or yellow, and about the size of a turkey’s egg. The plant, with its mammoth leaves growing one upon another attains to 20 feet, and its fruit is reached with a forked pole or bamboo.

We were told of springs over a high ridge, from the top of which our descent was over a mile into a deep gorge so steep that much of the way was by steps <cut> out in the hard clay. At the bottom we found a number of small basins dug in the clay banks, filled by the seeping waters. While there two native women came with calabashes, taking water away upon their heads.[98] On our return we found that those two women upon the beach had washed more clothes and made their linen whiter than foreigners would have done with ten times the amount of water, and this trait I often noticed among them.

Exploring the interior portion of the valley, we found beautiful fields of sweet potatoes, with melon vines and beans that had grown year after year, and one bean vine, as it spread over trees and brush, covered, I think, nearly half an acre. It was constantly in bloom, with pods in all stages and bushels of ripe beans loading its branches; near the ground it was 5 inches in diameter. It is said this bean was brought by Capt. Cook.[99] The natives made little use of it, but early ship masters gathered them for ship supplies.

We could not see how to procure water for a settlement, as to construct tanks would be expensive and take time, and then Br. N[athan Tanner] as one of the committee was opposed to any move that interfered with his plan of procuring a ship and emigrating the native saints to the coast, the outcome of which may be seen further along.

A storm the night before our leaving for Lahain[a] left the Channel very rough, and on setting sail in the morning we were at once [in a] chopped sea and soon in a dead and sultry calm of tropical heat. The natives plied their oars until exhausted, with little progress. The chopped sea and sultry calm was a terrible ordeal and all became sea-sick—so very sick, and like some others I became unconscious. When aroused from stupor I heard Br. Cannon tell Br. Napela to pray. He stood up in the bow, and in his native tongue and simple faith asked the Lord to have mercy upon his servants there so sick, and send the wind quick or they might die. I knew the wind would come, and it did, in less time than I take to write it, and we soon gladly landed at Lahain[a]. . . .

From a spirit of opposition and other causes the committee deferred for the present efforts relating to a place of gathering for the native saints. . . .

Prest Young again suggested that a place of gathering be obtained upon one of the islands, and so soon as the way opened to commence to gather the saints. Halalia still offers us his choice lands upon the island of Lanai, either to sell at a small price, or to give us to occupy free for a number of years, and this question, by vote of the Conference, was left to be settled by the Mission Presidency. As Prest Lewis feels compelled to remain with our business in Honolulu he lays it upon me, with Br. Karren, to go to Lahain[a] and with Br. Hammond go to Lanai,—select a place, and organize a commencement for the gathering of our native brethren, at once, with Br. E. Green to go with us, and open up and superintend farming works. For this purpose we obtained farm implements, seeds, and necessary outfit, and on the 22d of August 1854 sailed for Lah[aina], arriving after a three day’s voyage, and remained with Br. F. A. Hammond until Monday 28th when in a whale boat we crossed the Channel, 20 miles, to Lanai. As I am again sea sick and not strong at best, I feel poorly qualified for climbing up again to the valley. The whole island is but one mountain, the top of which is a beautiful concave or basin, in shape like a saucer, some 10 or more miles in diameter, of which I have written previously. . . .

Although we had spent several days, examining the valley and holding meetings among the natives, looking for a place to start our settlement, which as yet we could not decide upon, even to the day of our departure for Lah[aina]. On this morning I started alone for a walk, without thought as to where or how far I would go, and was glad to see Br. Green coming with me. In him I always had perfect confidence, with warmest friendship, and was glad for his coming. We talked of not having yet agreed upon the place for a town to be established, and wondering how the point would be settled, and were oblivious as to the distance we had come, or the features of that part of the valley over which we were walking, until we came to a tree, and stopped to look around. But when we did, it was with an admiration and an inspiration that filled us both, and I exclaimed “This is the spot we have been looking for!” to which he bore testimony. It was a plot of some hundreds of acres of excellent mesa or table land, sufficiently elevated to overlook the whole beautiful valley. We had walked about one and a half miles which we soon retraced, and made our report to the brethren, who were eager to visit the spot. In eating my breakfast I found myself, for the first time eating locus—a large green grasshopper, which I had not noticed until finding them too dry to relish I looked for something more juicy though perhaps equally as nasty. But braced up by a sense of our duties the nasty did not trouble us much.

We soon returned to the spot with the other brethren, and all with one voice said “This is the place,” and joy seemed to fill all. After a short period of congratulation it was moved that Br. Johnson name and dedicate this spot of ground for the gathering of the native saints; and this being expressed by unanimous vote I named the plot “Joseph” and the valley “Ephraim.” We knelt together in the dedication prayer, and on arising all were full of prophecy of good upon this spot; and I well rem[em]ber the words of my prediction—“that through the faithfulness of the elders from this spot salvation should begin to go forth to the children of Joseph upon these lands.”[100] We left Br. Green with seed and implements, to commence gathering around him the native saints, to build houses and start agriculture, designing that as soon as the elders now on their way should arrive one or more should be associated with him, and that Br. Karren also should return to his assistance. . . .

My health was now so very poor that Prest Lewis suggested that I return home;—but how can I shirk the fast-increasing responsibilities now upon me! . . .

On the 30th of Dec. a letter came from Apostle Pratt counselling us to ship the Press and material to San Francisco in view of greatly reducing expense of publication. By this I feel a full and honorable release, as our mission liabilities are being paid; but to get money for passage home is now the great question. . . .

The native saints learning I was soon to leave them, came with their small offerings in money—large, considering their poverty—and with tears and sobs said “good bye.” I found about $20 in these small sums. I was glad in the hope of again seeing my family, but had not realized how my heart was entwined with these poor people, and it required an effort to subdue my own grief at parting with them. . . .

Tuesday 16th We set sail—so joyful and so sad.[101] . . .

Our cabin was nicely fitted upon the after deck, containing about 20 persons; and with good weather and agreeable social relations we might reasonably hope for a pleasant and cheerful voyage, neither of which were in store for us. No sooner had we taken possession of our berths with hopes of rest and pleasant converse than we found we were associated with libertines, gamblers and renegades of the most prophane and vulgar character. On the 3d day a robbery was committed; some one had entered the Captain’s cabin, cut open his carpet bag and stolen a gold watch chain and jewelry to the value of $300.00. While we were known as Mormon missionaries we had hardly spoken to the captain to make his acquaintance; and we could but feel anxious in relation to the matter, when all, both sailors and passengers, were called on deck, the hatchways closed, while the captain and his officers searched on board. When our turn came, with our baggage on deck, we expected a rigid scrutiny, and felt a tremor of anxiety as the Captain stepped to my side and in a low voice said “Mr. Johnson, we shall only look a little at your things for form’s sake. We know you have not the property.” When we proceeded to open out everything he would not permit it, and to our surprise, moved away with apparent confidence and respect.—which was marvelous to us. . . .

Cold, sea sick and in peril, we endured these profane and vile fellow passengers and wore out the 22 long days of our passage. But to such a degree did they carry their blasphemous and beastly vulgarity that I rebuked them sharply. They seemed to feel the rebuke and did not again annoy us with their extreme foulness. They were men who had roamed over the world gathering in the vices of all nations, Christian or pagan.

On coming to anchor in the [San Francisco] bay, the Captain of Police was soon on board, to search again for the stolen property, but without finding trace of it. And leaving us, who had more baggage than others until the last, the captain said there was no need for farther search. I insisted that we should be searched, for, should he not find the lost property, he could never know that we had not robbed him. But he assured us he should always be perfectly satisfied upon that point, and seemed to take pleasure in giving us information, and in doing all within his power for our accommodation. . . .

We soon found temporary homes with some of the saints, I being invited and kindly cared for by Mother Mowry,[102] whose husband was not in the church; yet I was welcome. In flesh I was thin, and weak in body, but felt I would improve, and did, at once. My stay in San Francesco was very pleasant; apostle Pratt was there and some of the brethren from the islands were waiting to return with him in May. By Br. Pratt, I found our labors upon the islands had been appreciated. He spoke of my pamphlet in reply to the “Polynesian,” and said that nothing better had yet been published upon plural marriage;[103] and said the press and material we had procured belonged to us according as we had contributed to its purchase. I said I was sent out to work for God and his kingdom; and if I had been faithful I wanted the credit of having “well done.” And I could not be paid for leaving a dear family in dollars and cents. I had left the islands, I said, with just money enough to pay my passage at half fare; and as I had money with me due to the “news” “Seer”[104] and tithing office at home, I might use it for my outfit, but would repay every dollar before visiting the city after meeting with my family, then at Payson. . . .

As a steamer that would touch at San Pedro on her way to Panama was soon to leave port, we arranged for our passage; and Br. James Lawson, who had just arrived from the islands, arranged for passage with us. On our way down the coast we encountered the heaviest storm experienced upon the coast, and in a dense fog came near stranding upon the rocks; and such was the storm that when standing on the upper deck, 30 feet above the waters, the waves seemed like mountains above us.

After a cold and perilous passage both by sea and land we arrived at San Bernardino, and found that Capt. Hoopers team, with Capt. Congers mail party would start for Utah in one week; which, for a long period might be the only safe conduct through the hostile indian country. From Capt. Conger I learned that two horses, with pack and riding outfit for each man, with blankets and provisions would be necessary; and with the money due Prest Young and others I bought my horses and outfit. But one of my animals was pronounced unfit for the journey on the evening previous to our start; and this indeed seemed too much. For I had already more than I was able to do to get ready, and I felt I must wait another opportunity. But as usual I prayed that if now was the time for my return, that the way would open through some of those who came to visit our camp. I said to those present and who wondered what I would do, that I was in a degree upon their mercy or charity; that I was on my way home from a mission of years, and unless some one would exchange horses, and give me one that would do, for a reasonable difference I must remain, for I could not go around to hunt up a trade; and I must leave the matter with them and the Lord. Br. Thomas Holladay said he had a colt that would carry me if I could ride him, and brought him to me. . . .

At Cedar city[105] I found my brother George[106] and many other warm hearted friends, and at Johnson’s Fort[107] my brother Joel H.,[108] and at Parowan Br. James H. Martineau,[109] who accompanied me home, where I arrived March 26th 1855.

But I am again at home with my family in Payson, though worn, weary, weak and thin in flesh. But I know the Angel sent with me by the Prophet and the one promised me on my leaving the islands has been with me to open my way, and I look back with wonder to the many providences that have sustained me upon my mission and upon my return.

Notes

[1] The Pacific volcanic island chain of the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii) was occupied by natives sometime before AD 1000 and was explored by James Cook in 1778. Whalers and Christian missionaries came to the island in the nineteenth century. In 1850, the first Latter-day Saint missionaries arrived; the first branch was formed in 1851 on Maui, and by 1854 there were fifty-three branches. When the Utah elders left in 1858 because of the Utah War, the local Saints struggled. Walter Murray Gibson arrived in 1861 and began engaging in unorthodox practices, including selling priesthood offices. He was excommunicated in 1864, and the church purchased land at Laie, which became the new home for Hawaiian Latter-day Saints. Merriam-Webster’s Geographical Dictionary, s.v. “Hawaii”; R. Lanier Britsch, “Hawaii,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 474–76.

[2] Johnson, “Life Review by Benjamin F. Johnson,” 133, in Johnson, papers, box 1, folder 1; p. XXX herein.

[3] The Council of Fifty was an organization that convened under Joseph Smith between March and May 1844. It was intended to function as the kingdom of God, as opposed to the church of God, on earth. The council bolstered Joseph Smith’s presidential run in 1844 and discussed potential sites where the Saints could relocate. After Smith’s death, Brigham Young likewise convened the council between 1844 and 1846, and again after migrating to Utah. Grow et al., Joseph Smith Papers, Administrative Records, Council of Fifty, xxiii–xlv.

[4] LeBaron, Benjamin F. Johnson, 1–60.

[5] Summit Creek was founded by Johnson and others in 1851 and received its name because it was located at the summit between the Utah and Juab Valleys. Its name was changed to Santaquin in 1856. Van Cott, Utah Place Names, 331.

[6] Salt Creek flows out of the canyon south of Mount Nebo in central Utah. The area was settled in central Utah in 1851. The name of the settlement was changed to Nephi, after a Book of Mormon prophet, but some people of other faiths continued to call it Salt Creek. Van Cott, Utah Place Names, 272, 327.

[7] LeBaron, Benjamin F. Johnson, 62–79.

[8] Latter-day Saints in California were among the first to discover gold, and while gold would be a valuable resource to the Utah settlers, Brigham Young discouraged the Saints from seeking for gold, believing that they should gather in the Great Basin and raise crops. He believed that Sacramento was corrupt and unprofitable, but he did authorize some missionaries to go to California to obtain gold. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 64–71; Davies, “Mormons and California Gold,” 83–99.

[9] These eleven were George Q. Cannon, Henry Bigler, Thomas Whittle, James Keeler, John Dixon, Thomas Morris, William Farrer, James Hawkins, John Berry, Hiram Clark, and Hiram H. Blackwell. Berry started with the others but returned to Utah. Cannon, Journals of George Q. Cannon: Hawaiian Mission, xxxvii.

[10] British explorer William Brown visited the area of Honolulu in 1794, and it became a trading center in the Pacific Ocean in the nineteenth century. It became the capital of Hawaii in 1850, the same year that the first Latter-day Saint missionaries arrived. Joseph F. Smith, who later became President of the church, came to Hawaii in 1854, when there were fifty-three branches on the islands. Merriam-Webster’s Geographical Dictionary, s.v. “Honolulu”; R. Lanier Britsch, “Hawaii,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 474–76.

[11] Britsch, Moramona, 3–17; Cannon, Journals of George Q. Cannon: Hawaiian Mission, xxxiii–xli.

[12] William Farrer (1821–1906) was born in England and baptized in 1841. He traveled to Utah in 1847 and joined gold prospectors in California in 1849. He served a mission in the Sandwich Islands from 1850 to 1854 and nearly served again in 1856, but he returned to Utah for the Utah War. He died in Provo, Utah, in 1906. Journal of George Q. Cannon, People, s.v. “William Farrer.”

[13] Henry William Bigler (1815–1900) was born in Virginia and baptized in 1837. He went to Utah in 1848 after being part of the Mormon Battalion and staying temporarily in California. He served missions to Hawaii from 1850 to 1854 and again from 1857 to 1858. He died in St. George, Utah, in 1900. Bishop, “Henry William Bigler,” 122–36; Journal of George Q. Cannon, People, s.v. “Henry William Bigler.”

[14] Britsch, Moramona, 17–28; Cannon, Journals of George Q. Cannon: Hawaiian Mission, xli–lii.

[15] Zion’s Camp refers to an incident in May and June of 1834 when Joseph Smith led more than two hundred Latter-day Saints from Kirtland, Ohio, to Clay County, Missouri to reclaim lands taken from the Saints by mobs in Jackson County, Missouri. After marching nearly a thousand miles, the Saints met a hostile group of Missourians. Rather than fight to reclaim the land, Smith told his followers to disband and return to Ohio. The expedition failed in its initial purpose, but many veterans of the experience later became prominent leaders of the church. John M. Beck and Dennis A. Wright, “Zion’s Camp,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 1399–1400.

[16] In 1846, around five hundred Latter-day Saint men and eighty women and children left Council Bluffs, Iowa, to march to California to fight for the United States in the Mexican War. This Mormon Battalion arrived in California in January 1847. Most men were discharged from the Battalion in July 1847, but some served until March 1848. Larry C. Porter, Clark V. Johnson, and Susan Easton Black, “Mormon Battalion,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 783–85; John F. Yurtinus, “Mormon Battalion,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 2:935–36.

[17] Journal of George Q. Cannon, People, s.v. “McBride, William,” “Tanner, Nathan,” “Karren, Thomas,” “Green, Ephraim,” “Lawson, James,” “Allred, Reddick,” “Allred, Reddin,” “Snider, Egerton.”

[18] Philip B. Lewis (1804–1877) was born in Massachusetts and was baptized in 1842. He traveled to Utah in 1848. Lewis had helped fund a mission to the Society Islands in 1843 and was assigned to go there in 1851, but Parley P. Pratt appointed him as president of the Sandwich Islands Mission instead. He labored in Hawaii from 1851 to 1855, and he died in Kanab, Utah, in 1877. Journal of George Q. Cannon, People, s.v. “Philip Beesom Lewis.”

[19] LeBaron, Benjamin F. Johnson, 80–83.

[20] Smallpox was a highly contagious, painful, and often fatal disease, manifested by rashes and pustules. For centuries, Asian nations had practiced inoculation, whereby they inserted smallpox-infected pus or scabs into people’s flesh, which diminished the effects of the disease; inoculation was introduced into the Western World in 1721. In 1796, English physician Edward Jenner created a smallpox vaccine by infecting others with cowpox, which made them immune to smallpox. The vaccine was brought to America in 1800 and was endorsed by President Thomas Jefferson. Thanks to the vaccine, smallpox was eradicated worldwide in the 1970s. See Hopkins, Greatest Killer.

[21] Hawaiian officials ordered for quarantines and vaccinations for smallpox, but the Latter-day Saint missionaries believed that God would bless and heal the people, or at least that it was God’s will if they were not healed. Many of the missionaries were not vaccinated or violated quarantine regulations. This negligence made some view the Latter-day Saints unfavorably. Hammond, Island Adventures, 141–66; Johnson, “Life Review,” 151–52.

[22] LeBaron, Benjamin F. Johnson, 83–99; Britsch, Moramona, 29–34; Hammond, Island Adventures, 141–56.

[23] LeBaron, Benjamin F. Johnson, 86–94; Britsch, Moramona, 25–31, 35.

[24] Britsch, Moramona, 37–38.

[25] Lanai is one of Hawaii’s central islands. In 1854, the church’s Hawaiian mission purchased lands on Lanai as a gathering place for those who joined the church in Hawaii. Most Latter-day Saints were encouraged to gather to Utah, but conditions and laws in Hawaii made that impractical, so the island of Lanai became the gathering place instead, at least temporarily. Lanai had fertile soil, but it was rocky and dry, making it not an ideal agricultural land. As the most faithful Latter-day Saints gathered there, the other Hawaiian branches lost their most active church members and struggled to succeed. Britsch, Moramona, 35–49.

[26] LeBaron, Benjamin F. Johnson, 94–105; Britsch, Moramona, 35–42.

[27] The Walker War was named after Ute Chief Wakara (known also as Walker). In 1852, the Utah territorial legislature passed three acts intended to end the Ute slave trade with Mexican traders. These efforts, along with the encroachment of settlers on Ute hunting and gathering lands, created a tense environment between settlers and Indians, particularly in Utah County, Sanpete Valley, and other settlements south of the Salt Lake Valley. Atrocities were committed on both sides, and though Brigham Young at times instructed settlers to act only defensively, settlers continued organized assaults on Indians. In an attempt to end the hostilities, Young offered amnesty to the Utes in December 1853. Young also dispatched Indian agent E. A. Bedell to broker a peace with Wakara in March 1854. Dimick B. Huntington, who served as an interpreter, apparently went with Bedell. Young and Wakara met in May 1854 and formally ended the war. Peace, however, was temporary, as settlers continued to encroach on Indian lands and expend shared natural resources. Acts, Resolutions, and Memorials, 91–94; Watson, Life under the Horseshoe, 11–13; Christy, “Walker War,” 395–420; Farmer, On Zion’s Mount, 84–87.

[28] LeBaron, Benjamin F. Johnson, 107–27.

[29] The Utes were known for capturing children of other tribes and selling them into slavery, and pioneers often bought Native American children so that the Utes would not kill them. Settlers hoped the adoption of Indian children would protect the children from death and torture and from servitude. They also hoped to civilize a race they regarded as degraded by exposing adopted natives to religion, education, and Western culture. Muhlestein, “Utah Indians and the Indian Slave Trade”; Bennion, “Captivity, Adoption, Marriage and Identity”; LeBaron, Benjamin F. Johnson, 123.

[30] LeBaron, Benjamin F. Johnson, 136–39.

[31] LeBaron, Benjamin F. Johnson, 149–58.

[32] Johnson, “Life Review,” 279.

[33] LeBaron, Benjamin F. Johnson, 168–96.

[34] The Mormon Corridor is a north-south band of Latter-day Saint settlements in Utah and surrounding states. Michael N. Landon, “Mormon Corridor,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 786–87.

[35] Journal of George Q. Cannon, People, s.v. “McBride, William.”

[36] Journal of George Q. Cannon, People, s.v. “Tanner, Nathan.”

[37] Journal of George Q. Cannon, People, s.v. “Karren, Thomas.”

[38] Journal of George Q. Cannon, People, s.v. “Green, Ephraim.”

[39] Journal of George Q. Cannon, People, s.v. “Lawson, James.”

[40] Journal of George Q. Cannon, People, s.v. “Allred, Reddick.”

[41] Journal of George Q. Cannon, People, s.v. “Allred, Reddin.”

[42] Journal of George Q. Cannon, People, s.v. “Snider, Egerton.”

[43] Johnson, My Life’s Review, 359–60. His living children at this time were Benjamin Franklin, Melissa, Julia, Esther, Delcina, and Frances, all from Melissa; Joseph, from Mary Ann; and Huetta, from Clarinda. Harriet bore Benjamin Farland on January 20, 1853, and Mary Ann bore Benjamin Samuel on April 20, 1853. Frances died as an infant while Johnson was on his mission. Johnson, My Life’s Review, 208, 359–60.

[44] James Holman (1805–1873), Johnson’s father-in-law, arrived in Utah in 1847, then traveled to Utah again with his family the following year. Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel database, s.v. “James Sawyer Holman.”

[45] Johnson, “Life Review,” 135.

[46] Payson was originally named Peteetneet after the Indian chief of the same name. James Pace and others settled the area, thirteen miles south of Provo, in 1850, and the place came to be known as Pacen, later spelled Payson. Van Cott, Utah Place Names, 290.

[47] Santaquin Ward Manuscript History, 1853; Gottfredson, History of Indian Depredations in Utah, 78–82.

[48] Melissa L. Johnson to Benjamin F. Johnson, May 8, 1854.

[49] Johnson, My Life’s Review, 360.

[50] Melissa L. Johnson to Benjamin F. Johnson, May 8, 1854.

[51] Harriet Naomi Holman Johnson to Benjamin Franklin Johnson, no date, Johnson correspondence. Spelling and punctuation corrected for ease of reading.

[52] Johnson, My Life’s Review, 360–61.

[53] Johnson, My Life’s Review, 121.

[54] Johnson, My Life’s Review, 130–33

[55] Johnson, My Life’s Review, 150, 157.

[56] Benjamin F. Johnson to George F. Gibbs, 36–37, in Johnson, papers.

[57] Johnson, “Life Review,” 294.

[58] See Johnson, “Life Review” to review the omitted portions, which include the following accounts: Johnson’s blessing from Jedediah M. Grant (134), rescuing German immigrants from Indian attacks (136–38), a Spanish father attempting to pimp his daughters to Johnson in California (139–41), a disagreement with intoxicated Captain Erskine between San Pedro and San Francisco (142–43), personal clashes with Nathan Tanner and other missionaries (146–48, 162–63), Johnson’s role as an attorney in a court case stemming from quarantine laws (151–55), other government issues (155–58), arrival of the printing press (177–78), and Indian troubles on the way home (188–89).

[59] Excerpted from “A Life Review by Benjamin F. Johnson,” 132–89, holograph, MS 1289, box 1, folder 1, CHL. Also printed in My Life’s Review: The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin Johnson (Provo, UT: Grandin Book, 1997), 124–82.

[60] Melissa Bloomfield LeBaron (1820–60) married Benjamin F. Johnson on December 25, 1841, in Kirtland, Ohio. The two were sealed to each other twice: first in May 1843 in Macedonia, Illinois, by Joseph Smith, and second in February 1846 in the Nauvoo, Illinois, temple by Amasa Lyman. Johnson, My Life’s Review, 359.

[61] Frances Bell Johnson was born July 10, 1852, and died as an infant while Johnson was on his mission. Johnson, My Life’s Review, 208, 360.

[62] Orson Murray died in 1853 while Johnson was on his mission. Johnson, My Life’s Review, 154–55.

[63] Isaiah 55:8 reads, “For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways, saith the Lord.”

[64] In summer 1851, Johnson’s brother Joseph obtained a contract to carry mail from Salt Lake City north to Ogden and south to Manti. Johnson sublet the Manti route. Stations were established at Summit Creek, where he built a house for his wife Harriet, and at Salt Creek, where he built a house for his wife Mary Ann. His first wife, Melissa, lived in Salt Lake City. Johnson, My Life’s Review, 123.

[65] Manti, located about 120 miles south of Salt Lake City, was settled in 1849 and was named after a city in the Book of Mormon. Van Cott, Utah Place Names, 243–44.

[66] John Vickers (1822–1919) arrived in Utah in 1852. Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel database, s.v. “John Vickers.”

[67] David Udall (1829–1910) was born in England and was baptized in 1848. He arrived in Utah in 1852 and settled in Nephi. He served a genealogical mission to Britain in the 1890s. Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 2:112–13; Early Mormon Missionaries database, s.v. “David Udall.”

[68] John Vickers and David Udall had just recently arrived in Salt Lake City after crossing the plains when Johnson invited them to settle at Salt Creek (Nephi). They arrived in Salt Lake on September 5, 1852, and left for Nephi on September 20. Arizona Pioneer Mormon, 2–3, 282.

[69] In reality, there are approximately 700 miles between Salt Lake City and San Pedro, 400 miles between San Pedro and San Francisco, and 2,400 miles between San Francisco and Honolulu.

[70] Mary Ann Hale (1827–1910) was sealed to Johnson in Nauvoo, Illinois, in November 1844 by John Smith and again in the Nauvoo Temple in February 1846 by Amasa Lyman. Johnson, My Life’s Review, 359.

[71] Alexander Badlam (1809–94) was born in Massachusetts and was baptized in 1832. He had visited northern California twice before Brigham Young requested him to accompany Johnson to California in 1852. Badlam remained in California thereafter and even attempted to minister to the gold-seeking Chinese there before dying in San Francisco in 1894. Bagley, “Cities of the Wicked.”

[72] Parowan, in Iron County, was the first Latter-day Saint settlement south of Provo. It was originally called Little Salt Lake, after a small semi-salty lake (now a dry lakebed). Parley P. Pratt explored the area in 1850, and it was officially founded a year later as part of the Iron Mission under the direction of Apostle George A. Smith. Van Cott, Utah Place Names, 288–89; Janet Burton Seegmiller, “Parowan,” in Utah History Encyclopedia, 418.

[73] The Santa Clara River begins in the Pine Valley Mountains in southern Utah and drains into the Virgin River south of the city of St. George. Van Cott, Utah Place Names, 331.

[74] Norman Taylor (1828–99) first arrived in Utah in 1847 and then returned east to Winter Quarters. In 1850, he returned to Utah with his wife Lurana Forbush Taylor (1826–84) and his future wife Lydia Forbush (1830–1900). Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel database, s.v. “Norman Taylor,” “Lurana Forbush Taylor,” “Lydia Forbush,” “Milo Andrus Company (1850).”

[75] See chapter 2, note XX, p. XXX herein <<”Spiritualism began in New York”>>.

[76] See “Nason’s Line for San Pedro,” Daily Alta California, December 6, 1852.

[77] Located in north central California, Sacramento was first settled in 1839 and became an important trading site during the gold rush. It became California’s capital in 1854. Merriam-Webster’s Geographical Dictionary, s.v. “Sacramento.”

[78] John M. Horner (1821–1907) was born in New Jersey in 1821 and was baptized by Erastus Snow in 1840. In 1846, he traveled from New York to California on the ship Brooklyn, and he became a successful farmer in northern California, but he subsequently fell into great debt. He financially assisted the missionaries called in 1852 as they traveled to Asia and other places in the Pacific. In 1879, he moved to Hawaii, and he died in 1907. He never went to Utah, but he remained in contact with the church throughout his life. Green, “John M. Horner,” 244–46, 302–3, 340–42, 344–45.

[79] Quartus Strong Sparks (1820–91) was born in Massachusetts in 1820. He traveled on the ship Brooklyn to California in 1846, and he practiced law in San Bernardino and supported the missionary efforts of Parley P. Pratt and Hosea Stout. He was excommunicated in 1857, became an enemy of the church, and remained in California until he died in 1891. Bullock, Ship Brooklyn Saints, 219; Lyman, San Bernardino, 182, 316–17.

[80] The ship Huntress, captained by James L. Lambert, was built in Maine in 1850. It left California in late January 1853 and arrived in Honolulu on February 17. Captain Lambert had previously transported a group of Saints from Liverpool, England, to New Orleans, Louisiana. Sonne, Ships, Saints, and Mariners, 101.

[81] Turtle soup was not unheard of at this time, even in the United States, though it was increasingly viewed as a delicacy. Bronner, Grasping Things, 162–63.

[82] “When Shall We All Meet Again” was a hymn written by Parley P. Pratt and included in the Latter-day Saint hymnal published in Manchester, England, in 1840. A Collection of Sacred Hymns, no. 220, pp. 247–48; Chism, A Selection of Early Mormon Hymnbooks, 338.

[83] Edward Dennis was baptized in Honolulu in 1852 and became an elder in 1853. He donated money and time to the mission and left Hawaii in February 1854. He settled in San Bernardino, California, and departed from the restored church of Jesus Christ. Journal of George Q. Cannon, People, s.v. “Edward [Edmund in some sources] Dennis.”

[84] Malachi 4:5–6 of the Old Testament reads, “Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet before the coming of the great and dreadful day of the Lord: And he shall turn the heart of the fathers to the children, and the heart of the children to their fathers, lest I come and smite the earth with a curse.” Latter-day Saints use the term “Spirit of Elijah” to refer to an interest in and connection to one’s ancestors. Latter-day Saints believe that after death, the righteous in the spirit world preach to those who were never able to receive the gospel in their mortal lives. Mary Finlayson, “Elijah, Spirit of,” and Walter D. Bowen, “Spirit World,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 2:452, 3:1408–9.

[85] George Q. Cannon began his translation of the Book of Mormon in January 1852, assisted by Hawaiian convert Jonathan H. Napela. The translation was completed in January 1854, but it was not immediately printed. Church members pooled funds to purchase a printing press, and they ordered one from Boston. When the press arrived in October 1854, no one knew how to use it, so it was sent to California. Cannon printed the translation in San Francisco in an edition of 2,000, finishing it on January 28, 1856. A few copies were bound at the time the printing was completed, and 200 were bound eight months later, most of which were sent to the Hawaiian Islands. How many copies were ultimately bound is not known. Britsch, Moramona, 25–28; Crawley, Descriptive Bibliography of the Mormon Church, 3:266–70.

[86] Maui, the “Valley Isle,” is the second largest of the Hawaiian Islands, formed by two adjacent volcanoes that connected to each other, with an isthmus between them. The settlement of Wailuku is located on the north shore of the western portion of the island (not the eastern, as Johnson wrote). The western portion’s highest peak is Puu Kukui, at 5,787 feet. The eastern portion is made up of the volcano Haleakala, which takes up three-fourths of the island. Its highest peak, Red Hill, reaches 10,023 feet, and at the top of Red Hill is a large crater that formed not from volcanism but from erosion; it is more than 2,500 feet deep and covers an area of nineteen square miles. Merriam-Webster’s Geographical Dictionary, s.v. “Haleakala Crater,” “Maui.”

[87] Francis A. Hammond (1822–1900) was a sailor born in New York. He was baptized in 1847 in San Francisco and traveled to Utah in 1848. He served missions to Hawaii from 1851 to 1856 and again from 1864 to 1865. Hammond, Island Adventures.

[88] Ground cherries are a fruit similar to tomatoes or tomatillos. Whortleberry can refer to various berries of temperate areas of the Northern Hemisphere.

[89] Several species of sandalwood, a fragrant tree used for incense, grow in Hawaii. Between the 1770s and 1820s, sandalwood was greatly exported and exploited. Rock, Indigenous Trees of the Hawaiian Islands, 126–35.

[90] Makawao is a town on the north side of the eastern portion of Maui. Merriam-Webster’s Geographical Dictionary, s.v. “Makawao.”