The Restoration of the Gadfield Elm Chapel

Carol Wilkinson

Carol Wilkinson, “The Restoration of the Gadfield Elm Chapel,” in Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: The British Isles, ed. Cynthia Doxey, Robert C. Freeman, Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, and Dennis A. Wright (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2007), 41–59.

Carol Wilkinson was an associate professor in the Department of Exercise Sciences, Brigham Young University, when this was published.

The Gadfield Elm Chapel is situated in the beautiful, green, rolling hills of Worcestershire, England. In this pristine, remote location, it stands as a memorial to the United Brethren who originally built it in the early nineteenth century, to the Latter-day Saints who inherited it a few years later, and to the Saints who recently restored it. It serves as a reminder of the great Latter-day Saint missionary work of the nineteenth century in this region of England. This paper will examine the history of the Gadfield Elm Chapel and focus specifically on the events of the decade from 1994 to 2004 that led to the purchase, restoration, dedication, and donation of the chapel to the Church.

The United Brethren

The United Brethren were a group of about six hundred individuals who lived in the adjoining parts of the counties of Herefordshire, Gloucestershire, and Worcestershire in the 1830s. They were largely poor people who had originally formed a splinter group called the Primitive Methodists, which had broken off from the Methodist movement founded by John Wesley. Primitive Methodists based their movement on their distaste for the growing wealth of Methodism and its focus on formalism. A small group within the Primitive Methodists rallied around their leader Thomas Kington, but in the early 1830s this group was expelled from the Primitive Methodists and reorganized themselves into a group called the Society of the United Brethren.[1]

Under the direction of general superintendent Thomas Kington, meetings were held every three months to arrange a preaching plan for the United Brethren preachers. Each plan laid out the route of villages or preaching places in the circuit that the preacher should follow. As part of their sermons, preachers encouraged their listeners to engage in personal and family prayer using their own words rather than formalized prayers.[2]

On March 4, 1836, two United Brethren of the parish of Castle Froome, Thomas Kington, and John Benbow, a farmer at Hill Farm, purchased Gatfields Elm from Thomas Shipton of Dobbs Hill in the parish of Eldersfield for the sum of twenty-five pounds. The land measured two hundred thirty-five feet in length by about thirty-four feet in width. The Deed of Conveyance permitted a chapel to be built on this land for the use of the Society of the United Brethren of the Froome’s Hill Circuit.[3]

By 1840 the Society of the United Brethren had been formed into two circuits (or conferences) centered at Froome’s Hill and Gadfield Elm. The Society had about forty lay preachers when Wilford Woodruff arrived in March 1840.[4]

Early Missionary Work in the Area

On January 11, 1840, the ship Oxford, carrying Wilford Woodruff, John Taylor, and Theodore Turley, arrived in Liverpool.[5] Six days after his arrival in England, Elder Woodruff was assigned to go to the Potteries, the towns around Stoke-on-Trent, where he worked from January 22 to March 2. During this time, he met recent converts William and Ann Benbow in Hanley.[6] Wilford received a spiritual prompting from the Lord to move south and mentioned this impression to William, who said he had friends and family living in Herefordshire and would like to accompany Wilford to introduce him to them.[7] So the two of them journeyed to Hill Farm in Herefordshire to meet William’s brother, John Benbow, a wealthy farmer.

The two men arrived in Herefordshire on March 4 and went to John Benbow’s home, where Elder Woodruff preached the message of the restored gospel to John and his wife, Jane.[8]

Elder Woodruff wrote that he “rejoiced greatly at the news that Mr. Benbow gave me, that there was a company of men and women—over six hundred in number—who had broken off from the Wesleyan Methodists, and taken the name of United Brethren. . . . [Benbow also said that the United Brethren had been] searching for light and truth, but had gone as far as they could, and were continually calling upon the Lord to open the way before them, and send them light and knowledge that they might know the true way to be saved.”[9]

Elder Woodruff was soon at work spreading the message of the restored gospel in the community, utilizing the homes of the United Brethren, which were already licensed as preaching locations. An especially significant convert was Thomas Kington, who was baptized on March 21 after first hearing the message preached on March 17.[10] Within a short time many of the United Brethren followed his example and joined the Church.[11]

Over the next two years several important events occurred at the Gadfield Elm Chapel. On April 4, 1840, Elder Woodruff baptized eleven people after preaching in the chapel.[12] A month later, on Sunday, May 17, Brigham Young and Willard Richards addressed the membership gathered in the building.[13] The first conference organized in the British Mission took place in the chapel on Sunday, June 14, 1840. At this time Elder Woodruff organized the Bran Green and Gadfield Elm conference, consisting of twelve branches: Bran Green, Gadfield Elm, Kilcott, Dymock, Twigworth, Ryton, Lime Street, Deerhurst, Apperly, Norton, Leigh, and Hawcross.[14] On September 7, six months after Wilford Woodruff brought the message of the Restoration to this area, former members of the United Brethren who had since joined the Church gave the Gadfield Elm Chapel to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. It was the first chapel the fledgling, decade-old Church could claim title to in the world. A week later, on September 14, 1840, Elder Woodruff attended conferences at the chapel and at Froome’s Hill. At these two conferences, forty branches of the Church were represented, with a total membership of 1,007. Five branches were added—Cheltenham, Bristol, Weston, Cranham, and Highleadon. Brigham Young presided over a conference at the chapel on Sunday, December 14, 1840. On March 15, 1841, the addition of seven more branches of the Church were reported: Forest of Dean, Flyfor, Pinwich, Nantom Beachom, Hill Common, Frogmarsh, and Walton Hill. In 1842 the chapel was sold to help finance the emigration of Church members to the United States.[15]

During the following decades of private ownership, the building was neglected and became a ruin. The roof had caved in, people had pilfered stones from the walls, and vegetation had engulfed large portions of the structure. Over a century after the Church had sold the chapel, a visiting CES (Church Educational System) teacher described his feelings as he viewed the tumbled down edifice that had once been the site of glorious events:

Tucked obscurely in the corner

Of some farmer’s field

The small, stone chapel dwindles

With no apparent honor.The walls are crumbling, slowly,

Flooded by a rising tide of slender weeds.

The grey slate roof lies slumped upon the floor

In uncontested disarray.It is a pale, unlikely sanctuary

For the word of God.That spoken word

Once transformed itself into the air

Our forebears breathed,

The blood, that even after several generations,

Pulses quick in recognition

Of the mildest echo still abiding hereA gently simmering catalyst inviting us

To witness

And to praise.[16]

Purchase of Gadfield Elm Chapel

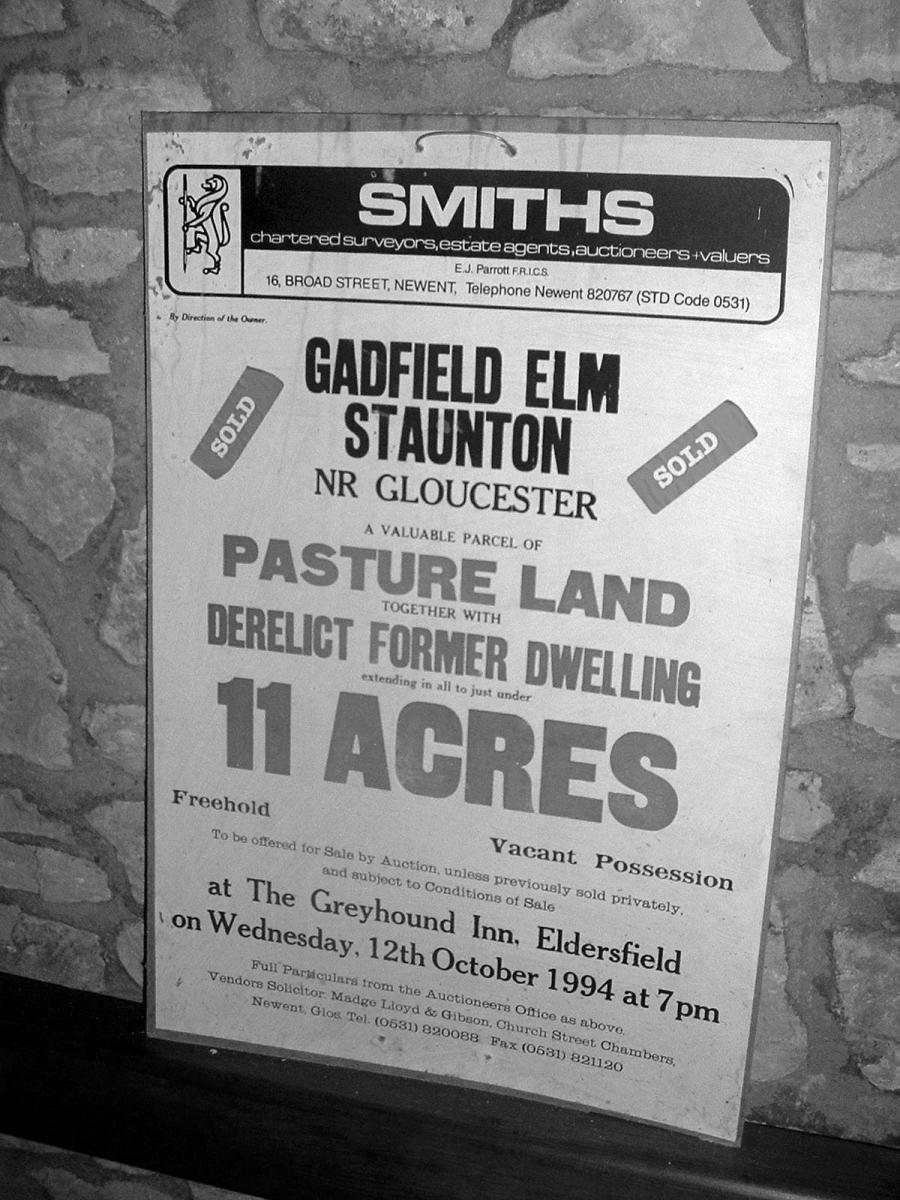

Wayne Gardner, bishop of the Hereford Ward, was an instrumental figure in the eventual acquisition of the chapel. He recalled that in the fall of 1994 several local members of the Church became aware that the dilapidated chapel was for sale. Several of these members had contacted stake and Church offices in Solihull, England, to see if the Church had plans to purchase the chapel. They did not. Apparently, Gardner had not learned of the sale until two weeks before the auction date, which was set for October 12, 1994.

Both by temperament and heritage, Brother Gardner was suitably equipped to investigate the possibility of acquiring the chapel. His family had moved to nearby Gloucester in 1974 when Wayne was a youth of fourteen. Wayne quickly developed a genuine interest in the local Church history of the area. He visited the sites made famous by Wilford Woodruff, the Benbows, Thomas Kington, and others during those heady, remarkable days of 1840–41, when hundreds and hundreds embraced the gospel. As a teenager, Wayne came under the tutelage of Dr. Ben Bloxham, a BYU professor who conducted ongoing research on the rich Church history of the area. Wayne came to share Bloxham’s deep passion and extensive knowledge of the early Latter-day Saint sojourn in the region.

Given his background, then, it was understandable for Brother Gardner to have more than a passing interest in the upcoming auction. He recalled his feelings and emotions as auction time drew near:

I knew I must do something. So I spoke to a few local members to see if anyone was interested in forming a trust . . . and found a few [Simon Gibson and Brian Bliss]. I also tried getting hold of Ben Bloxham, from Utah, because Ben had always said, “When you’re ready we’ll find someone who can help.” So I thought we should locate Ben, but I couldn’t. We had general conference broadcast the week before the auction, and I’m sitting in there and I notice Ben sitting in front of me! I’d been trying to track him down for a week and a half, and he’s suddenly sitting in front of me. When you’ve never done anything like that, it’s quite a difficult project to undertake: buying ruins using your own money. So the support of these three brothers gave me the confidence to move forward.[17]

Simon Gibson, a Church member from Monmouth, Wales, recalled how he initially became involved with this project:

Wayne Gardner worked for me in those days, and we were driving to work one day, and he said to me, “Gadfield Elm chapel’s for sale.” And I said, “Wasn’t that the old United Brethren chapel?” And he said, “Yes, why don’t we try and buy it at the auction and see if we can restore it? Because my fear is, if we don’t buy it, it’s going to be bulldozed and will be gone forever.” So, I said to Wayne, “I don’t know if I’ve really got the time to do something like this, it’s an awful lot of work,” not realizing just how much damage had been inflicted to this building from the owners and by vandals. Anyway, Wayne said, “Let’s go over tonight and have a look.”

So I remember driving over there with Wayne and it was dark and pouring with rain and there were only three walls left intact. The center wall was being held up by a telegraph pole, and the wall next to the road was virtually gone. It was only about two or three feet high. The wall where the door is, was missing pretty much down to the door. And then the wall with the windows, that faced the fields and the well, was totally in disarray but intact. There were no doors, and it was totally unsafe. A fully mature tree was growing in the middle of the building, and thorns and briars were everywhere. I mean, it was just in horrendous shape. It was pitch black. Wayne left me in there, and I remember thinking, “This is beyond repair.”

And I must admit I just stood there in the pouring rain and I did have a spiritual prompting, no doubt about that at all, telling me, “Do it.” Yes, definitely. Because I didn’t have the time or the inclination to really want to do it. And I remember all I could visualize in my mind was Wilford Woodruff’s eyes. Have you ever seen his eyes? Oh, I just saw those eyes, and then I thought of Brigham Young. . . . Once I’d had that spiritual witness that I needed to do it, I thought, “There’s no way I’m going into the next life not having done it and have to face those two very formidable gentlemen.” . . . That’s exactly what it was. I could visualize it. I mean it was just like there’s no way I’m not doing this now. I’ve got to do it because I think it would be important to those men and to the Church.

So there I was standing in the pouring rain, and then I got back into the car absolutely soaked. As I sat in the car I thought, “At least the fireplace was intact.” You know the little fireplace in the chapel there by the lectern? That was intact, and so you could imagine where the lectern had been. And I thought, “This has got to be the only place, certainly the only place I could think of in Europe, where you could, once it was restored, bring youth to. . . . They could sit in that chapel, and you could say, ‘On this spot Brigham Young, Wilford Woodruff, and Willard Richards all preached the message of the restored gospel.’ This one spot could act as a focal point for this wonderful story.” And I thought that would be a big deal for a lot of people. Imagine holding a testimony meeting in the chapel and inviting the kids to bear their testimonies on the same spot that Wilford Woodruff and Brigham Young testified to those people. You know, it would be powerful, which is what is happening right now.[18]

Brian Bliss, a Church member in Gloucester, was also willing to assist financially with the project, as was President Elvidge the England Bristol Mission president who had also seen the For Sale sign. So they, along with Wayne Gardner, Simon Gibson, and Ben Bloxham, came up with about six thousand pounds. Fortunately, when Wayne spoke to the local town planning people, they had zoned the land and property against residential development. Wayne felt this limited the interest in the property and probably ensured that the purchase price would be modest. He discovered that a local farmer who owned the adjacent land was interested in buying the land and then planned to demolish the chapel ruin. Wayne explained that his group would like to have the chapel plus one acre and suggested to the farmer that they not bid against one another but to let them do the bidding at the auction and then they would sell the other ten acres to the farmer afterward.[19]

Wayne and Brian Bliss attended the auction, which was held at 7 p.m. in a cozy room at the Greyhound Inn in Eldersfield (a village just over one mile east of Gadfield Elm Chapel) on Wednesday, October 12, with approximately twenty-five people present (including several locals and some Church members). Simon was attending a technology conference in Baltimore at the time and tuned in to the auction by phone from the States. Wayne recalled, “There wasn’t a lot of interest. I think they ran us up a little bit just to get the reserve price. [The sale closed at twenty thousand pounds.] But we were quite happy and the farmer said he was prepared to go fifteen thousand [pounds] and after that he wouldn’t honor his commitment. So that meant that it just cost us five thousand [pounds] then. So he gave us a thousand to cover fees.”[20]

Restoring the Chapel

Remedial work on the chapel began immediately. Latter-day Saint builder, Paul Woodhead from Weston-super-Mare, came with a couple men and used telegraph poles to prop up the walls and concreted the bases of the poles to help provide support. Wayne and his father, Peter, also helped with the project. At this stage, Wayne came to realize more fully that while they had indeed saved the building, the real work, the daunting task of restoration, lay ahead of them. During moments when the undertaking appeared especially formidable, they reasoned that if money-raising efforts fell short of the mark, they could at least preserve the chapel as a landmark ruin.[21]

Fortunately, they found that raising sufficient money for a complete restoration of the edifice was not an insurmountable problem. The Gadfield Elm Trust was organized with Wayne Gardner as chairman, Simon Gibson as vice chairman, Brian Bliss as treasurer, Ben Bloxham as historian, and Pam Gardner (Wayne’s mother) as secretary. The trust applied for charitable status and operated in accordance with the rules of the Charity Commission in England. In raising money, the trust’s aims were to preserve the chapel, to restore it to its condition when it was occupied by the United Brethren and the early Latter-day Saints, to raise awareness of nineteenth-century Church history in the British Isles, and to create a recreational site for public use.[22]

Raising the money necessary to really begin restoring the chapel rather than just doing remedial work on a ruin, although difficult, was not an insurmountable problem. Wayne reflected on one particularly gratifying experience during this time:

I was pretty confident and always felt, “Well, we’ve got this far. When the time is right, things will open up for us.” And they did, and at the right times and the right stages money became available, and we were able to do the things we wanted to. This was encouraging because it meant that there was a little bit of divine intervention, which helped us feel good about the project.

I had one experience after I returned from a trip to Germany. This was a couple of years after the auction, so we’d completed the quick remedial work and we were looking to rebuild the walls, which would take quite a bit of money. I was coming back from Germany, traveling through the night, and hadn’t slept properly for a couple of days. As I was driving past the road exit to the London temple, I thought, “I’ve got time to attend if I can make it there for 8:30 a.m.” But I was just a bit late and felt prompted to wait until I could go in at 9:30 a.m. . . . As I waited in the temple I noticed there were a couple of American brothers who were looking at a picture of Benbow’s pond. I explained a little bit about it to them, and how I was involved in the restoration of the Gadfield Elm Chapel. They were really very interested. Later, as we left the temple, I explained a little bit more about our restoration project, and they said, “Oh, we’d like to help.” I thought, “Yes, that’s great, but I’ve heard this before.” Then one of them told me that they owned a large business in Utah and were in a position to be able to offer real help. It just so happened I was going out to the States and was going to be in Utah on business a few weeks after that. So I arranged to see them, and they both donated some of their company stock to the Gadfield Elm Trust (via the Wilford Woodruff family group, who were also helping us). During this short transfer period the stock jumped, and that gave us enough money to get the builders back in so that we could rebuild the walls and floors and make the chapel more presentable. Of course, that was just out of the blue. I haven’t had a lot to do with them since, but they were just there at the right time. It was great because that helped us get through that stage, with a little divine intervention, which was very encouraging to us all.[23]

One of the trustees had an unexpected windfall in his business and was able to make a very significant donation to the trust, which, along with the other raised money, allowed the restoration work to proceed.

They also found challenges regarding building materials and chapel furnishings. Some of the stone was missing from the building. Luckily, there was a dilapidated barn about one hundred yards from the chapel built of stone from the same time period and the same quarry. The trust purchased some of that stone from the farmer who owned the barn, and work on rebuilding the chapel began.[24] Simon recalled:

The builders came in and started the work. The walls were unsafe, there was no integrity left in them, they were shot, either water-damaged at the foundation level or they were leaning, and clearly you wouldn’t put a new roof on, that was for sure. We decided to map the stones as they were removed so that every level was numbered. As a layer of stones was removed, it was laid flat on the ground. Then the next layer was laid flat on the ground, and so on. So it was built up exactly as it was originally. I think that’s probably what the architectural historians would do as I’ve seen them do it with other buildings. It’s like a jigsaw puzzle. The walls are removed and laid flat on the floor and where necessary, foundations are checked and fixed. Then you start at the nearest layer to you and just build the walls back up again in exactly the same order, inserting the windows.[25]

Once the walls were up, Church headquarters became involved and made a donation which helped pay for a new roof. Then the trust located a scrap merchant in Wales who specialized in church scrap, and he had just cleared some pews out of a nonconformist chapel in Wales. The pews were from the same time period as the original Gadfield Elm Chapel. The Trust purchased the pews, and Jim Griffin, a local member, sanded them down to retain their rustic appearance yet enhance the comfortableness. The old well outside was also restored and provided the water supply to the building. The whole project was completed in time for the new millennium.[26]

Dedication of the Chapel in 2000

Wayne recalled that Elder Spencer J. Condie the Church’s Area President in England was particularly supportive during the latter stages of chapel restoration. The announcement that Elder Jeffrey R. Holland of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles was traveling to England to fulfill Church responsibilities in neighboring stakes and to dedicate the chapel was received with anticipation and gratitude by local Church members. Elder Holland dedicated the building on Easter Sunday, April 23, 2000. Around 250 people attended the dedication, many of them waiting outside because the chapel seats only about one hundred.[27] The leaden skies and softly falling rain could not dampen the proceedings of the service. Bishop Gardner gave the opening remarks about the history of the chapel and the restoration process, and he recognized the contributions of many people. He was followed by the deputy mayor of Ledbury, Councilor Clive Jupp, who congratulated all who had worked on the restoration project. Before coming to the service, he had perused the Ledbury notes of town meetings held in 1840 that stated around two thousand people had left the area. He reflected that before the 1960s that would have been about half the population of Ledbury. With a smile on his face, he said, “I suspect any predecessors of mine wouldn’t have been quite so keen to promote an understanding. Thankfully these days we are more tolerant and keen to promote understanding between different denominations.”[28]

Elder Holland arose to speak and expressed what an emotional day this was for him. Having spent seven years serving the Church in England, he was extremely grateful to be given the opportunity to return for this special occasion on Easter Sunday. He congratulated President Condie and the members of the trust for the work that had been done. He mentioned that he had visited the site fifteen years ago when he was an Area President and the chapel was an overgrown ruin. Elder Holland stated that he now felt “quite chagrined with myself that I didn’t have the vision or opportunity or the timing. When it came up for auction, I wasn’t there.” He went on to express gratitude for others who had done something. He said that this was not just an ecclesiastical privilege but also a personal one since Ellen Benbow of Castle Froome and William Carter of Ledbury, who were married in Nauvoo, Illinois, were his direct ancestors. Then he pondered the possibility that perhaps Wilford Woodruff, Brigham Young, Willard Richards, and these two ancestors might be present at the dedication ceremony that day. Before giving the dedicatory prayer, Elder Holland recounted the circumstances leading to his presence there that day:

I’m supposed to be today in Fukuoka, Japan, with President Hinckley starting the first of four temple dedications that would have taken us from Fukuoka, Japan, to Adelaide, to Melbourne, Australia, to Suva, Fiji, and a quick side trip to Bangkok, Thailand [laughs]. Those are his [President Hinckley’s] kind of side trips. That’s where I’m supposed to be today. But in the broken-hearted prayers of the night, when I said, “Surely, surely they won’t dedicate Gadfield Elm without me,” suddenly there was a strike in Adelaide and all temple dedications were put on hold for a month. And President Hinckley said, “Well, you might as well go to England.” And don’t tell me that prayers of children and Apostles aren’t answered.[29]

Elder Holland asked for a show of hands if there were any descendants of the Carters or Benbows in the congregation. Several local people raised their hands, and he welcomed them. He mentioned that this was the first chapel the Church ever owned, whereas in 2000 the Church builds one chapel per day (not including Sunday). Elder Holland reflected that the Gadfield Elm Chapel, donated in the 1840s, signaled something of what this Church would become.

As he prepared to give the dedicatory prayer, Elder Holland explained that the Church had dedicated only one or two buildings that it did not own, but President Hinckley felt very strongly about having the Gadfield Elm Chapel dedicated. As he was speaking, Elder Holland observed the sunlight beginning to filter in through the side window and smilingly declared, “I knew the sun would come out before we were ready to pray.”[30]

In his prayer of dedication, Elder Holland said that the restored chapel was a tribute to those who went before who accepted and devoted themselves to the gospel, people who were not perfect but were believers. He prayed that something of that Spirit would be renewed, that modern Saints would emulate their example of being a light to the world. He expressed gratitude for the modern-day leaders of the trust, and of area and stake presidencies, who love God and who labored to create this edifice. He expressed gratitude for the leaders of the Church who had granted an apostolic involvement that day. He dedicated the building for God’s purposes, stating that it would not be a regular chapel but would be a suggestion or reminder of earlier days of worship. He prayed that the people who visited would feel a reverent and special spirit there. He also asked that through the priesthood the building would be protected, that people would be safe there, and that the building would be safe from the destructive forces of nature or vandals. He then dedicated the building to any other purpose that God would choose that may not be made know to us.[31]

Donation of the Chapel to the Church

From the beginning, the Gadfield Elm Trust made it clear that should the Church desire ownership of the chapel, it would be happily donated to them. In 2004 the Church accepted the offer. Elder Harold G. Hillam, president of the Europe West Area, called to inform the trust officials that President Hinckley would like to personally come to the chapel to collect the deed and dedicate the chapel.[32] The trust was asked to make the arrangements for the meeting and transfer of ownership and to keep the news of the occasion confidential. The date was set for Wednesday, May 26, 2004.[33]

Originally the Church suggested that only about twenty people be invited since this was an unscheduled event without the usual security measures. But after some discussion with trust members, this number was increased to eighty, and people who had been involved with the project were invited. Simon Gibson and Wayne Gardner each took half of the invitation list and called people, several of whom were overwhelmed and moved to tears at the opportunity to witness the event.[34]

Upon arriving at his home on the evening before the dedication, Wayne found a message on his answering machine from Elder Gerald N. Lund, a counselor in the Area Presidency, suggesting that it would be wonderful if the prophet could plant a tree the next day. So early the next morning Wayne went out and obtained an oak sapling. He went down to the chapel grounds and, after a little digging, created an area in the chapel grounds where President Hinckley could plant it.[35]

Elder Hillam conducted the ceremony. Simon spoke first about the restoration project, and then President Hinckley talked of the great missionary effort in the area in the nineteenth century and how the emigrating converts were a crucial, bolstering force for the struggling Church in Nauvoo. The Prophet then gave the dedicatory prayer. In the prayer he expressed gratitude that God had prompted certain local members to create a trust so that the chapel could be purchased and restored to its original condition. He paid tribute to the early leaders of the dispensation who had borne their testimonies of the Savior and the restoration of the gospel and who had touched the lives of many in this edifice. After asking that the building be protected from destructive forces, President Hinckley asked for “Thy blessings upon Thy work here in this great and beautiful land, the United Kingdom and Ireland. Touch again the hearts of the people as Thou didst once touch them in the past, that thousands more may embrace the gospel, and that the Church may grow and flourish and become strong and well known in this part of the world. There has been a falling away from the established Churches in this area. We pray that as that has occurred, that there may be a strengthening of Thy work.”[36]

Following the prayer, Wayne presented the keys and deed of the chapel to the Prophet. “I’ll look after it as long as I live,” President Hinckley promised. After the transfer of the deed from Bishop Gardner to President Hinckley, everyone moved outside to witness the prophet plant the oak sapling. It was “tough soil,” President Hinckley jocularly remarked after digging two spadefuls. Ever sensitive of others, the Prophet then turned the spadework over to Bishop Gardner’s father, longtime member Peter Gardner, who contributed further to this appropriate and symbolic gesture.[37]

Current Use of Gadfield Elm Chapel

Because the Church now owns the chapel, the Cheltenham Stake has responsibility for the day-to-day running of it (it lies within the stake’s boundaries). After the dedication of the chapel in 2004, a missionary couple, Elder Alec Mitchell and Sister Jeni Mitchell, were assigned to work at the chapel. They created a display containing historical information about the chapel and the background of converts from the area. They also arranged period plays for visiting children to participate in. Since the chapel opened in 2004, children and teens have comprised a large number of the visitors. From the beginning of January until September of 2005, there were approximately 2,500 visitors, of which five percent were not members of the Church.[38]

Since the building is a historic chapel, sacrament meetings and other weekly Sunday meetings are not regularly held at Gadfield Elm. Nor are marriages performed in the chapel. That said, the Church has indicated that it is appropriate, even desirable, to use the building for special events such as firesides, Relief Society meetings, and seminary graduations. People are allowed to camp on the property next to the chapel, and youth groups and families have traveled from different parts of Britain to camp there, learn about the history of the area, and hold firesides.

In 2005 the trust financed the purchase of hymnbooks and the printing of brochures on the history of Gadfield Elm that are on display at the chapel. They also advertise the building in the local What’s On magazine.

Conclusion

The Gadfield Elm Chapel and the surrounding hills and fields are oases of solitude. The quiet is broken only by sounds of nature and the purr of an occasional distant car or farm machine. The tranquility and geographical remoteness create the feeling that one has stepped back into a bygone era. In the stillness, it can be hard to imagine the religious activity and excitement that long ago swept across this area, changing so many lives, affecting the population of the area, and ultimately supporting an emerging Church in the United States. For Latter-day Saints and for interested people of other faith traditions, the chapel stands sturdy and strong in its remote location, a reminder of the simple beginnings of the Church in England and a testament to the faith and vision of a people intent on building the kingdom of God.

Notes

[1] See David J. Whittaker, “Harvest in Herefordshire,” Ensign, January 1987, 49.

[2] See Job Smith, “The United Brethren,” Improvement Era, May 1910, 820–21.

[3] See “Deed of Conveyance Between Thomas Shipton (as Grantor) of the One Part and John Benbow and Thomas Kington (as Grantees) of the Other Part Dated 4 March 1836,” Public Record Office, London, transcripted copy by V. Ben Bloxham in author’s possession.

[4] See Whittaker, “Harvest,” 49.

[5] See James B. Allen, Ronald K. Esplin, and David J. Whittaker, Men with a Mission: The Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in the British Isles, 1837–1841 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 79–80.

[6] See Whittaker, “Harvest,” 48–9.

[7] See Wilford Woodruff, “Elder Woodruff’s Letter Concluded,” Times and Seasons, March 1, 1841, 327.

[8] See Wilford Woodruff, Leaves from My Journal, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor, 1882), 78–79.

[9] Woodruff, Leaves from My Journal, 79.

[10] See Woodruff, “Elder Woodruff’s Letter Concluded,” 328.

[11] See Woodruff, Leaves from My Journal, 81.

[12] See Woodruff, “Elder Woodruff’s Letter Concluded,” 329.

[13] See The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “The History of Gadfield Elm Chapel,” http://www.lds.org.uk/

[14] See “Minutes of the Conference held at the Gadfield Elm Chapel, in Worcestershire, England, June 14th, 1840,” Millennial Star, August 1840, 84–5.

[15] See The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “The History of Gadfield Elm Chapel,” http://www.lds.org.uk/

[16] Randall L. Hall, “Gadfield Elm Chapel,” in BYU Studies 27, no. 2 (Spring 1987): 12.

[17] Wayne Gardner, interview by Carol Wilkinson, May 31, 2005, in author’s possession.

[18] Simon Gibson, interview by Carol Wilkinson, August 11, 2005, in author’s possession.

[19] Gardner interview.

[20] Gardner interview.

[21] See Gardner interview.

[22] See the Gadfield Elm Trust, “The Gadfield Elm Trust,” brochure published in 1996.

[23] Gardner interview.

[24] See Gardner interview.

[25] Gibson interview.

[26] See Gibson interview.

[27] See “World’s First Mormon Chapel Reopens,” This is Herefordshire, http://

[28] Clive Jupp, address at dedication of Gadfield Elm Chapel, April 23, 2000, videotape in possession of author, transcribed by author.

[29] Jeffrey R. Holland, address at dedication of Gadfield Elm Chapel, April 23, 2000, videotape in possession of author; transcribed by author.

[30] Jeffrey R. Holland, address at dedication of Gadfield Elm Chapel.

[31] See Jeffrey R. Holland, address at dedication of Gadfield Elm Chapel.

[32] Elder Jeffrey R. Holland dedicated the chapel before the Church owned the building. The second dedication of the chapel by President Gordon B. Hinckley was linked to the transfer of chapel ownership to the Church.

[33] See Gardner interview.

[34] See Gibson interview.

[35] See Gardner interview.

[36] Gordon B. Hinckley, “Dedicatory Prayer of the Gadfield Elm Chapel,” Deseret News Archives, http://www.desnews.com/

[37] “Little Chapel’s Keys Returned to Church,” Church News, June 5, 2004.

[38] See Brian Palmer (counselor in the Cheltenham Stake presidency), interview by Carol Wilkinson, in author’s possession.