"Nearer, My God, to Thee": The Sinking of the Titanic

Richard E. Bennett and Jeffery L. Jensen

Richard E. Bennett and Jeffrey L. Jensen, “‘Nearer, My God, to Thee’: The Sinking of the Titanic,” in Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: The British Isles, ed. Cynthia Doxey, Robert C. Freeman, Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, and Dennis A. Wright (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2007), 109–27.

Richard E. Bennett was a professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was published. Jeffrey L. Jensen was a student researcher with degrees in history and marriage, family, and human development when this was published.

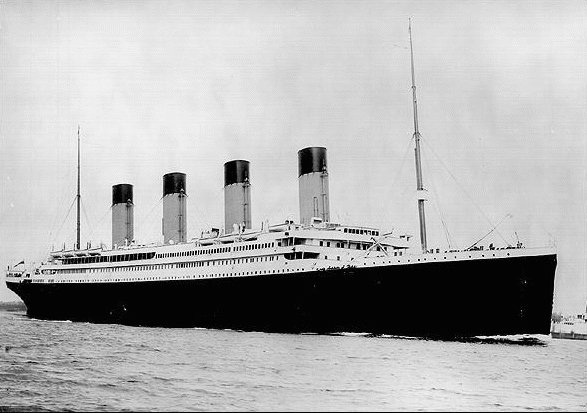

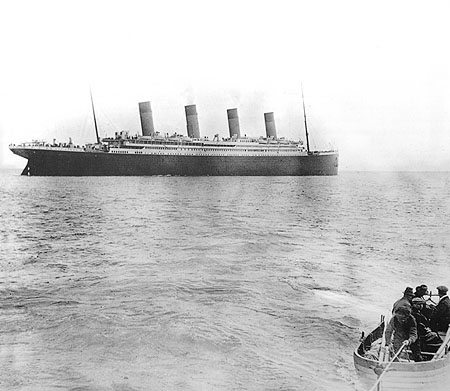

At 2:20 a.m. on April 15, 1912, in the frigid depths of the North Atlantic off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, the forty-six-thousand-ton luxury ship Titanic (then the world’s largest ocean liner) sank less than three hours after colliding with an iceberg. Of the 2,201 passengers and crew on board, 1,490 perished.

Although the Titanic sank beneath the calm surface of the ocean almost a century ago, the memory of it remains very much alive. It continues to live on in ways thousands of other vessels long mothballed or scrapped have failed to do. As recently as December 2005, the lead editorial in the Deseret Morning News in Salt Lake City spoke of the finding of new information on the timeline of the sinking of the great ship. The article concluded, “More than 93 years after the tragic accident, the Titanic still makes headlines.”[1]

The scope and character of the tragedy; the pitting of man’s pride, technology, and industrial might against the enduring indomitability of nature; the utter carelessness and needlessness of it all; the irony of the maiden voyage being its last—all bear the elements of a Greek tragedy. Unlike scores of other marine tragedies, the wreck of the Titanic continues to speak to something deep in our psyche, a morality lesson for the ages, as if the entire human race were on board that fateful April night.

While much has been and undoubtedly will continue to be written about the disaster, the purpose of this chapter is to study its effect on Latter-day Saints and how both the leadership and the rank-and-file membership reacted to it. The Latter-day Saint response may be most appropriately studied from both sides of the Atlantic: first, the American or Utah-based reaction, which tended toward a more doctrinal, moralistic construct; and second, the British-Mormon response, which more acutely grieved the loss of one of England’s most liberal supporters and activists of religious tolerance, diversity, and pluralism and a true friend of the Mormon people. The chapter concludes by looking at the Latter-day Saint view of redemption for the dead and how this doctrine was applied to those lost in the disaster.

The Utah Response

News of the sinking of the Titanic reached Salt Lake City by wireless telegraph late in the evening of April 15. As with many others elsewhere, Latter-day Saints received the news with a mixture of incredulity, astonishment, horror, and profound sadness. They yearned to know more about the tragedy—who and how many survived. Rumor had it that several missionaries returning from their fields of labor were on board the ship. The prominent English-born Apostle James E. Talmage confided in his journal on April 16: “Yesterday telegraphic dispatches brought word of an appalling disaster; and the lapse of a day has served rather to intensify than to mitigate the horror. By wireless waves word was flashed from a point in the Atlantic eleven hundred and fifty miles from New York that the White Star steam ship Titanic was wrecked through collision with an ice-berg and that within a short time the great vessel went down.” Writing three days later, upon hearing of those rescued at sea by the Carpathia, he continued: “The stories of mental and physical suffering are agonizing. It is not to be wondered at that some of those who were rescued have since gone insane. It now appears to be almost surely true that the death list is much larger than was at first reported, numbering in fact over sixteen hundred souls. May the Lord comfort the bereaved and the suffering.”[2]

Although the Church itself made no official response to the news—in fact, no directives of any kind were sent to congregations throughout the Church—the Titanic’s sinking spawned a good deal of commentary from the highest Church authorities and from regular members. It was simply too arresting a tragedy not to provoke an outpouring of grief, and it begged doctrinal explication to place it all in perspective.

At a meeting in the Salt Lake Temple on April 17, the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles discussed the tragedy at length. President Anthon H. Lund of the First Presidency “spoke upon the great Disaster of the sinking of the Titanic” and saluted the courage of the Carpathia for coming to the rescue of so many stranded in life boats. “What a blessing the wireless is,” he said. “But for this, none might have been saved.”[3]

The first formal public Latter-day Saint response came the Sunday after the sinking, in the famed Mormon Tabernacle during the final session of the downtown Salt Lake City Liberty Stake (diocese) quarterly conference on April 21, with President Lund presiding and Elder Orson F. Whitney of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and Elder Rulon S. Wells of the First Council of the Seventy speaking. After the choir sang “Though Deepening Trials Throng Your Way,” “God Moves in a Mysterious Way,” and “Nearer, My God, to Thee,” Elder Whitney rose to speak on behalf of the entire Church to a particularly hushed and silent congregation. “I feel the deep solemnity of this hour. My heart is at half-mast. I am mourning with you . . . and with the whole American people and the civilized world over the great disaster of the Titanic. . . . It is appalling to consider that in the providence of God so vast a number of his children should be called instantaneously into eternity.” Elder Whitney then went on to show why the Latter-day Saints found the sinking to be of such interest: “There is not a people on earth to whom this idea has greater significance than to the Latter-day Saints. There is perhaps no people with a larger percentage of their number who have crossed the mighty deep.[4] There is probably not a family in the Church that has not one or more members who have been on the ocean. . . . My heart is full of sympathy for those whose loved ones went down in this great disaster. I have naught but sorrow and condolence to express and no word of thought or censure shall escape my tongue. Let God judge who is to blame.”

Elder Whitney emphasized what he called the principle of “compensation,” not in the financial but in the moralistic, religious sense. He said, “For the fall of Adam there was the compensation that man should be; for the crucifixion of the Savior there is the great compensation of eternal life; and for the Titanic disaster there will be compensation.” His point, like that undoubtedly echoed in sermons that Sunday around the world, was that this terror would bear positive results for many souls. He continued: “If the sinking of the Titanic, the flicking out of 1,600 human lives shall teach the countless numbers of humanity to guard against a recurrence of disaster and to render safer the crossing of the mighty deep; if it shall teach men there is something more to live for than the accumulation of gold, the attainment of pleasure and the realization of speed; if it shall turn the hearts of any considerable number of God’s children to thoughts and deeds that shall lead to their salvation, then those who went down with the Titanic shall not have died in vain.”[5]

The closest thing to an official Church response came a few weeks later from President Joseph F. Smith, who had earlier called it “the worst disaster at sea in the history of the world.”[6] He roundly condemned “the seemingly criminal carelessness” in running the great ship at excessive speeds into the ice fields. In a highly critical and uncharacteristically negative tone, he said that “every chance was taken for the sake of speed,” that the ship was on a course too far north, that there were too few and improperly equipped life-boats, and that the ship’s searchlights should have been “stronger and more carefully applied.” Above all, he condemned the haughtiness and irresponsibility of those who defiantly claimed the ship to be invincible and virtually unsinkable while foolishly pursuing a course of inevitable tragedy. He went on to relate the terrible tragedy to spiritual catastrophe:

Spiritually, the catastrophe teaches us that the boasts which one sometimes hears from certain sea captains and unbelieving passengers, expressed in a recent sacrilegious statement of a captain to one of the elders of our Church, “You need not give a damn for God in this kind of a ship,”—are vain, unwarranted and unreasonable. It teaches with a force that should stir the rankest unbeliever that mankind is still dependent upon Him “who stilleth the noise of the seas, the noise of their waves, and the tumult of the people.”[7]

Revered by his people as a prophet, seer, and revelator, President Smith had a personal connection to the disaster. His cousin Irene Colvin Corbett, a thirty-year-old wife and mother of three, had earlier sought his counsel before departing for England to study midwifery. Having previously earned a degree from Brigham Young Academy in nursing, she had been encouraged by several Utah doctors to pursue her studies abroad. Her husband, however, had asked her not to go, and President Smith counseled her likewise. “He told her he believed she could learn as much at home, and that his counsel was for her not to go.”[8] Strong-willed and ambitious, Corbett nevertheless went ahead with her plans. After six months of study in a London hospital, she excitedly dashed off a quick postcard to her family in Provo, Utah: “Leave London soon. Am going to sail on one of the biggest ships afloat: The Titanic, an American liner.” Just a few days later came a much more somber communication: “Irene took Titanic. Name not among survivors.” The Payson, Utah, native was one of just fourteen women traveling in second class who went down with the ship.[9] Corbett was the only known Latter-day Saint to perish on board the doomed ocean liner.

Other Latter-day Saints probably should have been on board. Between 1910 and 1912, five hundred to one thousand converts immigrated to North America each year, usually in groups of five to sixty persons. Most bookings by this time were made with the White Star, Cunard, Dominion, or Allen shipping lines. The most preferred steamers were the White Star’s Luarentic and Megantic, each about 15,000 tons; the Canada of Dominion Lines, 9,415 tons; and the famous Cunard sister ships Lusitania and Mauretania, each weighing more than 30,000 tons. During 1912, 928 Latter-day Saint converts sailed in sixty-eight groups from England to North America. Many of these left from Liverpool and landed in New York; St. John’s, New Brunswick; Boston; or Montreal. During the month of April alone, ninety-eight Mormon converts set sail from England, the great majority sailing from Liverpool.[10]

While no evidence yet suggests that Mormon converts were scheduled to sail to America on board the new queen of the White Star line, six young returning missionaries—Alma Sonne, George B. Chambers, Willard Richards, John R. Sayer, F. A. Dahle, and L. J. Shurtliff—all had been booked passage on the Titanic by Elder Sonne himself, who had served as emigration clerk in Liverpool for much of his mission. What a greater farewell for successful missionaries than to send them home on the world’s greatest ship! The Church’s British newspaper, the Millennial Star, saluted Elder Sonne for his fine work as emigration agent, wishing him “God speed and marked success in that wider field of endeavor to which the great ocean liner and overland express will swiftly carry him.”[11]

“Then a strange thing happened,” as Sonne’s biographer reports. “[Elder] Fred Dahle . . . sent a wire a day or two before their scheduled departure stating that he had been delayed and could not arrive by the 12th. He suggested that the other elders go on without him. Alma, for some inexplicable reason, cancelled their bookings on the Titanic and rebooked them on the Mauretania leaving a day later. ‘I did this on my own responsibility,’ he later said, ‘and the others in the group manifested a little resentment because they were not sailing on the Titanic.’”[12]

There are unsubstantiated rumors that Mormon missionaries were on board the Carpathia, the ship that saved several hundred Titanic passengers in lifeboats. Elder James Hamilton Martin was on board the Virginian en route from Halifax to Liverpool when it changed directions to help with rescue efforts if necessary. He wrote: “Shortly after 9 a.m. [April 15] we reached the iceberg that had caused the sinking of the largest steamship afloat and the death of 1,630 people and for six hours traveled along side of it. It was no more and no less than a mountain of ice. At 11 a.m. we passed the place where the Titanic went down.”[13]

A few Latter-day Saints interpreted the sinking as evidence of a long-held doctrine that Satan, the destroyer, rides upon the waters. An early 1831 revelation to the Prophet Joseph Smith had stated: “There are many dangers upon the waters, and more especially hereafter; for I, the Lord, have decreed in mine anger many destructions upon the waters; . . . nevertheless all flesh is in mine hand, and he that is faithful among you shall not perish by the waters (D&C 61:4–6).” In an article titled “Dangers Upon the Deep,” Elder Orson Whitney wrote:

One frightful feature of the unparalleled struggle that ended with the signing of the armistice (November 11, 1918), was the havoc wrought by the German U-boats, otherwise known as submarines. There had been, before the coming of the U-boat, dreadful dangers upon the waters, as the fate of the ill-starred Titanic—ripped open by an iceberg—testifies. But the submarine, the assassin of the Lusitania, multiplied those dangers a hundredfold. Did the proud world know that a prophet of God had foreseen these fearful happenings, and had sounded a warning of their approach?[14]

While others read into the tragedy God’s hand of punishment, Elder Talmage, for one, took the more merciful viewpoint: “While I have no thought that this disaster is to be regarded by man as a direct judgment for some specific sin or offence, one cannot fail to realize that a power higher than man has spoken, and human pride stands rebuked.”[15]

The response to the tragedy among the rank-and-file membership of the Church is also worthy of discussion. Two examples may suffice: the first from a schoolteacher and the other from an amateur poet. Albert R. Lyman of Grayson, Utah, wrote the following entry in his journal on April 25 after a long day of teaching: “I was depressed in mind over the terrible news of 1500 passengers on the S. S. Titanic sinking off the coast of Newfoundland. The details were very distressing. After putting all the women who would leave their husbands on life-boats, the Capt. stood on the bridge, colors flying, and band playing ‘Nearer My God to Thee’ when the wrecked ship went down.” The next morning the Titanic was the point of discussion in their religion class. “A very kind feeling prevailed and some tears were shed. All the forenoon was like a funeral.”[16]

And from Lula Greene Richards, in her poem entitled “Nearer to Thee,” published in Salt Lake City just one week after the disaster, came a plea for man’s repentance.

“In a moment, suddenly,”

Launched into eternity!

Lo, a host, returning home,

Sank beneath the ocean’s foam:

Meeting death with this brave plea,

Nearer, O God, to Thee! . . .

As men might a world equip,

Sailed that proud, Titanic ship!

Heed, O world, its warning sent—

Cry repentance, and repent!

Thus to live, let all agree,

Nearer, Israel’s God, to Thee.[17]

The British Saints’ Response

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, the Millennial Star likewise expressed sentiments of “horror and sympathetic grief.” [18] Elder Rudger Clawson, an Apostle then serving as president of the European Mission, pointed out that “death is no respecter of persons,” as shown in the list of victims. Rich and poor, educated and ignorant, all perished together in the icy North Atlantic waters, there to remain “until called forth by the power of the resurrection.” The loss of the Titanic underscored not only the uncertainty of life but also the fact that “man is still comparatively helpless when combating . . . the mighty deep.”[19]

The British Saints turned their private mourning into a public charity by organizing a Titanic benefit concert. Held on May 4, 1912, in South Tottenham, London, the concert was “well attended” [20] and quite successful, “both artistically and financially.” Latter-day Saints performed “songs, piano selections, and recitations, which were of the highest order.” The former mayor of Finsbury, London, Alderman E. H. Tripp, spoke favorably of the evening. Tripp “was not at all surprised” that the Latter-day Saints were “among the first to contribute their means and talents to such a deserving cause.” Having previously visited Utah, Tripp said he had never before in all his travels “come across a more charitable people” both to each other and also “to every needy person with whom they came in contact.”[21]

No aspect of the disaster, however, bore more disappointment to the British Saints than the loss of one particular friend and advocate. From time to time in Church history, key friends from outside the faith have come to aid the Latter-day Saints at critical times. Alexander Doniphan’s courageous stand in Far West, Missouri, in 1838 immediately comes to mind as the one who saved Joseph Smith from an almost certain unjust execution. Likewise, Thomas L. Kane played a positive contributing role in raising the Mormon Battalion in 1846 and later in successfully negotiating a resolution between the government of the United States and the Mormon people during the so-called Utah War of 1857, an act that saved the lives of hundreds, if not thousands, of people. To this honorable list we should probably add the name of another important friend—William Thomas Stead.

As news of the sinking spread, speculation was rampant about who had survived the ordeal. Various reports published the names of the Titanic’s most prominent, wealthiest passengers, such as Colonel John Jacob Astor, Benjamin Guggenheim, Isidore Strauss, and Harry Widener, debating whether they had survived. Until the Carpathia docked in New York with all the Titanic’s survivors, nothing had been confirmed.

A prominent person feared to be lost was William T. Stead, editor of the Review of Reviews and one of England’s most popular, outspoken journalists. Among the British Saints, perhaps no other loss could have had more devastating results. When confirmed that his name was not on the list of survivors, Rudger Clawson wrote that “surely every Latter-day Saint whose eyes rest upon the writings of Mr. Stead . . . , will ever hold [him] in honorable remembrance.”[22]

Born in 1849 in the small English village of Embleton, Stead nearly followed his father into the ministry but chose journalism instead. Stead believed his talents were “to be used on behalf of the poor, the outcast, and the oppressed.”[23] Stead built a reputation for himself through his originality and independence of thought while championing unpopular causes.[24] Through his constant efforts at ensuring justice and suing for peace, he was considered one of the greatest crusading journalists in the world at the time of his death. “Intimately connected” with promoters of the world peace movement, Stead was well acquainted with Czar Alexander III, Nicholas II, and other world leaders. Nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize five times, many believed he would finally win in 1912. In fact, Stead was sailing to New York at the personal invitation of President William Howard Taft of the United States to speak at a peace conference in Carnegie Hall when he went down with the Titanic.[25]

Stead sought for peace not only among nations but among religions as well. He took a special interest in the Mormons, not as a believer in their faith but as a champion for their right to coexist with other denominations of the day. During the last half of the 19th century and certainly since the public pronouncement of Mormon polygamy in 1852, the British press had grown increasingly critical of the Mormons.[26] Such antagonism mounted as Mormon missionary success grew and tens of thousands of British Latter-day Saints emigrated to America, sometimes at the cost of dividing families and separating dear friends. The Reed Smoot trials in Washington between 1904 and 1907 and the ensuing journalistic muckraking of the Latter-day Saints in America contributed to British disdain.[27] What followed was a British crusade, of sorts, against Mormonism that ran from 1910 to 1913. “At the heart of the campaign,” as historian Malcolm Thorp has indicated, “was the belief that thousands of British girls were being lured away by false pretenses to Utah.”[28] Despite the manifestos of 1890 and 1906 separating the Church from the practice of plural marriage, decade-old rumors persisted that Mormon missionaries were in Britain only to find and ship off young women to Utah to snare them into polygamous marriages.[29]

Newspapers were responsible for spreading much of the anti-Mormon sentiment. In April 1911 the London Daily Express began promoting anti-Mormon meetings aimed at gaining support for anti-Mormon legislation—and selling newspapers.[30] The crusade generally took the form of rallies and resolutions against the Latter-day Saints, asking the Mormon elders to leave town by a certain time or else face dire consequences. While the crusades were generally peaceful, violence broke out in some areas. [31] Unquestionably, Mormon missionary work in Britain suffered adversely from the spate of negative publicity. Clawson admitted as much when he wrote, “The persecution has planted a prejudice in the minds of the people towards us that is hard to overcome and had told heavily against us in the matter of baptisms.”[32]

It was just these kinds of unjust activities that William Stead vehemently derided. As the prestigious editor of the Pall Mall Gazette since the 1880s, Stead condemned the anti-Mormon agitation and bore “testimony from a personal knowledge of the people and the country that there was not a vestige of truth in the charges brought against the [Mormons].”[33] On April 28, 1911, he wrote:

I protest against this undisguised appeal to the hateful spirit of religious persecution as an outrage upon the fundamental principle of religious liberty, an outrage which is none the lest detestable because it is masked by the hypocritical and mendacious pretence of a desire to protect English girls from being lured into polygamous harems. . . .

The attack upon the Mormons is almost entirely based upon the lie that their propaganda in this country is a propaganda in favor of polygamy, and that the chief object of the Mormon missionaries is to allure innocent and unsuspecting English girls into polygamous marriages.

I have called this a lie because it is a demonstrably false statement, which is repeated again and again after it has been proved to be false. Not one of the anti-Mormon crusaders has ever been able to produce any evidence that at any time, in any place within the King’s dominions, has any Mormon apostle, elder, or missionary ever appealed, publicly or privately, to any one of the King’s subjects, male or female, to enter into polygamous relations with anyone here or in Utah. . . .

The falsehood that thousands of English girls are being shipped to Utah every year is sheer, unmitigated rot.[34]

Stead continued, “The whole so-called crusade is an outbreak of sectarian savagery worked up by journalists.”[35]

The candor of Stead’s writing went far toward suppressing the boldness of the anti-Mormon sentiment throughout England.[36] Elder Clawson was so moved at Stead’s defense that he sent copies of Stead’s letters to President Joseph F. Smith, who deemed them so fair and favorable toward the Church that he authorized portions thereof to be used as a published tract (over 80,000 were distributed). One of these tracts was used for many years in the European Mission. Recognizing the sincerity of Stead’s convictions in defending an honest people, Clawson wrote, “All honor to this courageous man who, in the face of a frowning world, dared to wield his pen, mightily, in defence of an unpopular and apparently helpless people.”[37]

By all accounts, William Stead’s contribution to the Latter-day Saints in Britain was substantial. As a defender of religious freedom, he worked relentlessly to create an environment of religious tolerance and understanding. Due in large part to his liberal perspectives and powerful pen, anti-Mormon sentiment decreased in Great Britain. By 1914, just before the outbreak of World War I, the anti-Mormon crusade had decreased substantially, although the negative portrayal of the Latter-day Saints would persist in popular attitudes for years to come. His demise on board the great ship was a great loss to many, including the Latter-day Saints.

Redemption for the Dead

As with thoughtful people everywhere, the Latter-day Saints sought spiritual solace and doctrinal explication for this disaster. “Who can tell why?” one Mormon journalist asked. “Some have attempted to answer the query, but have failed. The peril which surrounded those thousands developed heroes who will be praised in song and story. . . . As they plunged to their watery grave, so well did that air ‘Nearer My God to Thee,’ fit the occasion.”[38] And trying to put the best face on a dreadful story, another wrote: “We are loth to mention the names of special ones who call for our consideration in the great disaster that has overwhelmed the world, lest, perchance, some whose name has not been mentioned should be slighted. Doubtless there were, as there always has been, heroes who did their work in the quiet and silent darkness on the ill-fated Titanic, and whose names have been lost amid the splendor of the few. Let us believe, however, that they recognized their neighbors.”[39]

Unique to the Latter-day Saint faith are two signal doctrines: the temple covenants of eternal marriage and those of baptism for the dead. The Titanic stirred discussion and elaboration of both. The Church-owned Improvement Era published S. S. Cohen’s poem that had appeared earlier in a New York City magazine about two particular passengers: Mr. and Mrs. Strauss who chose to go down together that fateful night.

I cannot leave thee, husband; in thine arm

Enfolded, I am safe from all alarm.

If God hath willed that we should pass, this night,

Through the dark waters to Eternal Light,

Oh, let us thank Him with our latest breath

For welded life and undivided death.[40]

While many people of all faiths hope for and believe in the possibility of eternal companionship beyond the grave, Latter-day Saints believe that through faithfully observing temple covenants, this hope takes on firm doctrinal assurance. Elder George F. Richards, another member of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles, chose to address this topic during his sermon in Ogden, Utah, at the Weber Stake Conference held on April 21. He regretted the “pathetic parting” of husband and wife that in so many instances marked the final moment of the tragedy and dwelt on the “subject of the eternity of the marriage covenant in this connection, showing the comfort of the knowledge of a reunion after death.”[41]

Likewise, there was much discussion about baptism for the dead. Latter-day Saints believe that the dead will be taught the fulness of the gospel of Jesus Christ hereafter and receive by proxy those saving ordinances necessary for their eternal progression. Some years before the sinking, the Church had established the Genealogical Society of Utah as a symbol of a growing realization and reiteration of the importance of Church members doing such redemptive temple ordinances as baptism for the dead and sealings (temple marriages) for those deceased.[42] Wrote President Charles W. Penrose of the First Presidency several months after the tragedy: “The minds of the Latter-day Saints have been turned in recent years to the necessity of learning something about their ancestry, not as a matter of pride but that they might be able to understand their relationship to their forefathers, that they may be able to do something in their behalf in the way that the Lord has revealed in this dispensation. . . . For, in this great and last dispensation the work of the Lord extends not only to the living but to those who have departed, that those who have gone before . . . might have an opportunity of learning the mind and will of God.”

And as to the need and manner of baptism for the dead, he continued:

And why should people be baptized over the dead? . . . Because those that die and go into the other world without baptism can’t be baptized there. Water is an earthly fluid composed of two gases—oxygen and hydrogen in certain proportions. It belongs here on this globe, on this earth. . . .

How glorious will be the day when we meet with our friends who have departed, and they cluster around us, when we depart from the flesh and enter into the spirit world, and they thank us for the good work we have done towards their redemption.[43]

Thus, the Latter-day Saints believed that ultimately the people who perished in the tragedy of the Titanic would be redeemed through the universal Resurrection of Christ because even the “sea [will give] up the dead which were in it” (Revelation 20:13) Furthermore, those who died could receive the blessings of the gospel through saving temple ordinances vicariously performed in their behalf.

Knowing all this, within a week of Stead’s drowning, Rudger Clawson wrote the First Presidency on April 20, 1912, recounting Stead’s efforts in stemming the anti-Mormon tide. Conveying his warm sentiments toward Mr. Stead, Clawson proposed that his temple work be done as “a simple act of charity and appreciation” for his efforts.[44] The First Presidency endorsed his suggestion wholeheartedly. Upon his return to Utah one year later, Rudger Clawson was baptized for and in behalf of Mr. Stead in the Salt Lake Temple on May 13, 1913, and stood as proxy for him in receiving his endowment on the following day.[45] Of this special occasion, Clawson wrote, “Those who lift up their voices and wield their pens in defense of the Latter-day Saints will in no wise lose their reward.”[46]

A final note: writing almost a century after the fact, I cannot help but be impressed with the widespread outcry of grief and sorrow this particular event triggered upon a worldwide audience. Surely the drama of the Titanic and how it sank will ever play out on the world stage. However, in our era, benumbed as it is by such subsequent horrors and calamities as two world wars, epidemics and diseases, and natural disasters, a reported loss of 1,500 people on a ferry boat sinking in the Red Sea evokes barely a nod in this news-saturated society. Perhaps the real tragedy of the Titanic is that unless tragedy is on a profound and large scale, empathy has become a victim of endless reporting of one horror after another. It may be the loss of the sense of loss that is now at stake. If the story of the Titanic can retain for all what tragedy can really mean, it will ever be a story worth remembering and worthy of reverent discussion.

Notes

[1] “More Titanic Information,” Deseret Morning News, December 10, 2005.

[2] James E. Talmage Journal, MS 229, April 16, 19, 1912. L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[3] Anthon H. Lund, Danish Apostle: the Diaries of Anthon H. Lund, 1890–1921, ed. John P. Hatch (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, Smith-Pettit Foundation, 2006), 477–78.

[4] By the end of 1870 alone, with the completion of the transcontinental railroad, more than 51,000 Latter-day Saints had emigrated to America, of whom 38,000 were from Great Britain and over 13,000 were from Scandinavia and other parts of Europe. By 1890, the comparable number stood at approximately 95,000 (see Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830–1900 [Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1958], 99, 381).

[5] “Compensation in Great Disaster,” Deseret News, April 22, 1912.

[6] “City Mourns with Half-Masted Flags,” Salt Lake City Herald, April 20, 1912.

[7] “The Titanic Disaster,” Improvement Era, May 1912, 15:646–48.

[8] Anthon H. Lund, Danish Apostle, 479.

[9] Ogden-Standard Examiner, May 23, 2004; see also the desk diary of Joseph F. Smith, Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library. The Titanic was, of course, a British, not an American, ship. Irene Corbett had once been a schoolteacher at Peteetneet Academy in Payson, Utah, but her first love was always medicine. She left a husband, Walter H. Corbett, and three children: Walter, 5; Roene, 3; and Mack, 2. Walter died in a mining accident five years later, and all three children were raised by Irene’s parents.

[10] We are indebted to Professor Fred Woods, Brigham Young University, for these statistics; see also European Mission Registers, Church Archives.

[11] Millennial Star, April 13, 1912, 251.

[12] Conway B. Sonne, A Man Named Alma: The World of Alma Sonne (Bountiful, UT: Horizon Publishers, 1988), 83–84. According to the Millennial Star, the above-named missionaries sailed from England on board the Mauretania on April 13, 1912 (see Millennial Star, April 13, 1912, 254). During the entire year 1912, an estimated 275 Mormon missionaries sailed from England to North America, 14 of them during April (see Millennial Star, consecutive issues for 1912; see also listings from Professor Fred E. Woods).

[13] Letter from W. C. Spence to J. Y. Calahan, May 1, 1912, Church Transportation Agent, Outgoing Correspondence, Church Archives, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City.

[14] Orson F. Whitney, Saturday Night Thoughts: A Series of Dissertations on Spiritual, Historical and Philosophic Themes (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1921), 63.

[15] James E. Talmage Journal, April 18, 1912, Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library.

[16] Journal of Albert R. Lyman, MS 1425 April 25–26, 1912, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library.

[17] L. Lula Greene Richards, “Nearer to Thee,” April 22, 1912, Photograph Collections, Church Archives.

[18] “The Sinking of the World’s Greatest Liner,” Millennial Star, April 18, 1912, 250.

[19] “The Sinking of the World’s Greatest Liner,” 250.

[20] “The ‘Anti-Mormon’ Agitation at Sunderland,” Millennial Star, May 16, 1912, 312.

[21] “Titanic Benefit Concert,” Millennial Star, May 16, 1912, 317.

[22] “William T. Stead and His Defence of the Mormons,” Millennial Star, May 2, 1912, 284.

[23] W. T. Stead Journal Entry, July 4, 1875. Electronic copy courtesy of www.attackingthedevil.co.uk, accessed September 20, 2006.

[24] For example, he condemned the British government’s involvement in the popular Boer War although he had previously started a campaign to expose the frailty of the British navy that prompted a 3.5 million pound government handout to update and repair their ageing ships. Another one of his most successful causes was uncovering the vices of child prostitution in London, a problem the government knew about but had continually turned a blind eye upon.

[25] See Frederic Whyte, The Life of W .T. Stead (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1925). Other information also gathered from electronically filed documents at www.attackingthedevil.co.uk.

[26] For a detailed treatment of the anti-Mormon crusade during this time, see David S. Hoopes and Roy H. Hoopes, The Making of a Mormon Apostle: The Story of Rudger Clawson (Lanham, MD: Madison Books, 1990), 253–67; see also Malcolm R.Thorp, “The Mormon Peril: The Crusade against the Saints in Britain, 1910–1914,” Journal of Mormon History 2 (1975): 69–88.

[27] See Thorp, “The Mormon Peril,” 72. A careful study of the full impact of the Reed Smoot controversy and the attendant media coverage on Great Britain and its dominions has yet to be written.

[28] Thorp, “The Mormon Peril,” 77.

[29] The Reverend Daniel D. C. Bartlett, vicar of St. Nathaniel’s, Liverpool; Hans Peter Freece, the son of a Utah Mormon polygamist; the popular novelist Winifred Graham; the Catholic preacher Father Bernard Vaughan; Bishop J. F. C. Welldon, Dean of Manchester and a well-known classical scholar; William Jarmin, an ex-Mormon; and other prominent members of several communities openly supported anti-Mormon agitation and the drafting of legislation in Parliament banning the Mormon religion from being preached and practiced. Letters were even sent to a young Winston Churchill petitioning him for support of the anti-Mormon legislation. Churchill’s involvement was limited and his responses were neutral to the situation, although he conducted an inquiry and believed that government intervention was not required. While Churchill was careful not to appear supportive of one party over another, William Stead had contact with Churchill and established a good relationship with him (see Rudger Clawson Memoirs [1926], 430–31, Special Collections, Marriott Library, University of Utah).

[30] Clawson said of the press generally that “they will deal with us in their own way and from their own standpoint. They have not asked for our help and they do not want it” (Rudger Clawson Memoirs [1926], 427, Special Collections, Marriott Library).

[31] Malcolm R. Thorp, “‘The Mormon Peril’: The Crusade Against the Saints in Britain, 1910–1914.” Journal of Mormon History 2 (1975), 69. In one area, a local presiding elder was assaulted by a mob and tarred and feathered (Millennial Star, June 6, 1912, 301).

[32] Rudger Clawson, “Memoirs of the Life of Rudger Clawson, Written by Himself” (1926), Typescript, Utah State Historical Society, Salt Lake City, UT, as cited in Thorp, “The Mormon Peril,” 88.

[33] Edward H. Tripp, Letter to the Editor of the Tottenham and Edmonton Weekly Herald, June 7, 1912, reprinted in “Words of Praise from a Non-“Mormon,” Millennial Star, June 27, 1912, 411–13. Tripp, a non-Mormon, was himself a factor in mitigating discord and anti-Mormon prejudice.

[34] London Daily Express, April 28, 1911. As reprinted in “Religious Liberty,” Millennial Star, May 2, 1912, 281–83; and in Vousden, “The English Editor,” 72–75. Stead closed his letter by illustrating the positive effects the episode would end up having on Latter day-Saint missionary efforts.

“The whole so-called crusade is an outbreak of sectarian savagery worked up by journalists, who in their zest for sensation appear to be quite indifferent to the fact that the only permanent result of their exploit will be to advertise and to spread the Mormon faith among the masses, who love fair play and who hate religious persecution none the less because it is based upon a lie” (Millennial Star, May 2, 1912, 283).

[35] William T. Stead and His Defence of the Mormons,” Millennial Star, May 2, 1912, 283.

[36] One British missionary said that he considered an article written by Stead to be “the finest defense the church has ever had from a man of Mr. Stead’s standing in the world” (personal writings of Walter Monson contained in the Rudger Clawson Memoirs, Special Collections, Marriott Library).

[37] William T. Stead and His Defence of the Mormons,” Millennial Star, May 2, 1912, 283.

[38] “The Power of Music,” Liahona, the Elders’ Journal, April 30, 1912, 714.

[39] Liahona, the Elders’ Journal, May 7, 1912, 726.

[40] Improvement Era, “A Love Story,” July 1912, 773.

[41] Deseret News, April 22, 1912.

[42] James B. Allen, Jessie L. Embry, and Kahlile B. Mehr, Hearts Turned to the Fathers: A History of the Genealogical Society of Utah, 1894–1994 (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, Brigham Young University, 1995), 44–47. Although organized in 1894, it was not until 1911 that the Genealogical Society began to establish genealogical committees in wards and branches throughout the Church (76).

[43] Charles W. Penrose, “Salvation for the Dead,” Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine, January 1913, 2, 14, 18.

[44] Rudger Clawson Memoirs, 434.

[45] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints did not forget Stead’s contributions to its missionary efforts and his defense of the Saints in Great Britain. When Stead’s wife, Emma Wilson, passed away twenty years later in September 1932, her temple work was promptly completed and she was sealed to her husband on October 3, 1932 (see Rudger Clawson Memoirs, 434–35).

[46] Rudger Clawson Memoirs, 435.