Adding and Taking Away "without a cause" in Matthew 5:22

Daniel K Judd and Allen W. Stoddard

Daniel K Judd and Allen W. Stoddard, “Adding and Taking Away ‘Without a Cause’ in Matthew 5:22” in How the New Testament Came to Be: The Thirty-fifth Annual Sidney B. Sperry Symposium, ed. Kent P. Jackson and Frank F. Judd Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2006), 157–174.

Daniel K Judd was a professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University and Allen W. Stoddard was a senior at Brigham Young University majoring in English and Asian studies when this was published.

The book of Revelation ends with the following words of warning familiar to many Latter-day Saints: “For I testify unto every man that heareth the words of the prophecy of this book, if any man shall add unto these things, God shall add unto him the plagues that are written in this book: and if any man shall take away from the words of the book of this prophecy, God shall take away his part out of the book of life, and out of the holy city, and from the things which are written in this book” (Revelation 22:18–19). Latter-day Saint familiarity with these verses comes, in many cases, from confrontations with those who use this biblical text to challenge the legitimacy of the Book of Mormon or other latter-day scripture. Some individuals reject the idea of adding any new scripture to the canon.[1]

Many traditional New Testament scholars have the same point of view as latter-day prophets, apostles, and scholars who teach that the warning in the book of Revelation and a similar text found in the Old Testament (see Deuteronomy 4:2–3) are warnings against corrupting the contents of the individual books of scripture and not against adding additional books of authorized scripture.[2] These conclusions are supported by the sixty-one books of scripture following the warning in Deuteronomy and scholars’ belief that the epistles of John were written and added to the New Testament after the book of Revelation.[3] There is, however, ample evidence that the Savior’s warning in Revelation 22:18–19 has not been heeded and that both the Old and New Testaments have undergone textual corruption.

In the Book of Mormon, the prophet Nephi stated, “Many plain and precious things . . . have been taken out of the book [Bible], which were plain unto the understanding of the children of men” (1 Nephi 13:29). Nephi also explained that “because of these things which are taken away out of the gospel of the Lamb, an exceedingly great many do stumble, yea, insomuch that Satan hath great power over them” (1 Nephi 13:29, emphasis added). While there are countless examples of biblical texts that have not been “translated [or transmitted] correctly” (Article of Faith 8), this study aims to describe in some detail the textual and theological corruption of the teachings of Jesus concerning anger in Matthew 5:22. This study will also briefly discuss the implications of the textual changes and the inspired translation, correction, and understanding of latter-day prophets, seers, and revelators.[4]

Textual Changes through Translation and Transmission

The Prophet Joseph Smith taught, “I believe the Bible as it read when it came from the pen of the original writers.”[5] But he also declared, “From sundry revelations which had been received, it was apparent that many important points touching the salvation of men, had been taken from the Bible, or lost before it was compiled.”[6] Many ancient and modern clergyman and scholars have come to similar conclusions. Writing as early as the third century AD, Christian theologian Origen recorded, “The differences among the [New Testament] manuscripts have become great, either through the negligence of some copyists or through the perverse audacity of others; they either neglect to check over what they have transcribed, or, in the process of checking, they make additions or deletions as they please.”[7] Nearly a century later, Jerome wrote of the copyists who “write down not what they find but what they think is the meaning; and while they attempt to rectify the errors of others, they merely expose their own.”[8]

One New Testament scholar, after acknowledging and discussing the many “mistakes” in biblical translation and transmission, concludes that “scribes occasionally altered the words of their sacred texts to make them more patently orthodox and to prevent their misuse by Christians who espoused aberrant views.”[9] Elder Jeffrey R. Holland noted that because of “a misreading (and surely, in some cases, a mistranslation) of the Bible,” “some in the contemporary world suffer from a distressing misconception of [God].”[10]

As the Prophet Joseph Smith and others have stated, plain and precious writings and teachings of the Savior and His servants were modified both by those who made simple mistakes in copying, translating, and transmitting the text, and by others who did so intentionally. While there are many examples of innocent mistakes in both the Old and New Testaments, there are also examples of similar unintentional errors in the Book of Mormon. Alma 32:30 provides one classic example of what translators call “parablepsis.”[11]

Alma 32: 30-31 (Original Manuscript)[12] | Alma 32: 30-31 (1830 Edition) |

But behold, as the seed swelleth, and sprouteth, and beginneth to grow, then you must needs say that the seed is good; for behold it swelleth, and sprouteth, and beginneth to grow. And now, behold, will not this strengthen your faith? Yea, it will strengthen your faith: for ye will say I know that this is a good seed; for behold it sprouteth and beginneth to grow. And now behold… | But behold, as the seed swelleth, and sprouteth, and beginneth to grow, and then ye must needs say, That the seed is good; for behold it swelleth, and sprouteth, and beginneth to grow. And now behold . . . |

A careful comparison of both the Original Manuscript and Printer’s Manuscript of Alma 32 with the printed edition published in 1830 reveals that the typesetter omitted thirty-five words from the end of Alma 32:30. This innocent mistake was probably made when the typesetter’s eyes moved from the phrase “sprouteth, and beginneth to grow. And now behold” to the similar phrase later in the verse— inadvertently skipping the words in between. The missing text was restored in the 1981 edition and is found in each subsequent printing. This is an example of a mistake with no apparent harmful consequences. And while there have been a number of editorial changes in the Book of Mormon over the years, even those who criticize its authenticity acknowledge that the changes are not of major doctrinal significance.[13] However, many of the errors in the translation, transmission, and editing of the New Testament are of significantly greater consequence.

The Teachings of Jesus on Anger

In the Sermon on the Mount in the King James translation, Jesus provided the following counsel concerning anger: “Ye have heard that it was said by them of old time, Thou shalt not kill; and whosoever shall kill shall be in danger of the judgment: But I say unto you, that whosoever is angry with his brother without a cause shall be in danger of the judgment: and whosoever shall say to his brother, Raca, shall be in danger of the council: but whosoever shall say, Thou fool, shall be in danger of hell fire” (Matthew 5:21–22, emphasis added). The portion of this scripture that has been the subject of controversy and discussion for centuries, and which is the primary focus of this study, is the phrase “without a cause.” Some manuscripts and versions of the text in Matthew 5:22 include the phrase “without a cause,” and others do not. The inclusion of the phrase implies that anger is justified if one has sufficient cause. The exclusion of “without a cause” eliminates such justification and appears to be an invitation from Jesus to eliminate anger from our lives.

Manuscript and Early Textual Evidence

Many scholars in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries adopted the motto ad fontes, which is Latin for “to the source.” Instead of relying on commentary, those scholars attempted to identify truth by going directly to the ancient documents. In addition to Classical scholars examining the original writings of philosophers such as Aristotle and Cicero, biblical scholars sought to examine the earliest texts of the Bible. The major problem, however, with attempting to examine the teachings of Jesus on anger by examining the original New Testament documents is that the original documents do not exist (or have not been discovered). All of the 5,735 ancient manuscripts (whole or partial) of the New Testament that have been catalogued are copies of copies.[14] While opinions vary concerning the dates when the New Testament manuscripts were written, many scholars believe that “the earliest known New Testament manuscript” is a papyrus fragment of the Gospel of John, identified by the symbol P52, that has been dated between AD 100 and 150.[15] The earliest surviving manuscript of Matthew 5:22 has been dated as early as AD 125–50.[16] The reference is included on a small fragment designated as the “Barcelona” papyrus and is identified by the symbol P67. The Barcelona text does not include any form of the phrase “without a cause.”[17]

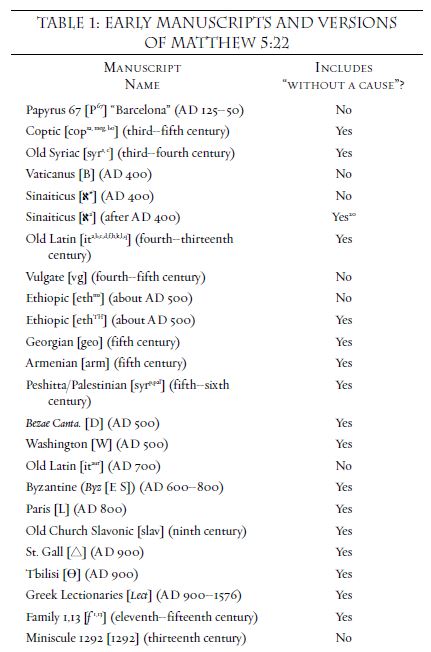

Table 1 is a listing of the earliest and most reliable ancient manuscripts and versions of Matthew 5:22.[18] It also indicates whether the phrase (or a form of the phrase) “without cause” is included. It is significant to note the great variance among manuscripts and versions concerning the inclusion or omission of the “without a cause” phrase.

By examining the earliest manuscripts and versions of the New Testament, it is clear that the absence of the phrase “without a cause” represents the earliest reading. The manuscripts which do not contain this phrase are normally of the Alexandrian text type. Although more Byzantine and other text types exist, the Alexandrian text types are considered older and more reliable.[19] Textual evidence shows that the phrase “without a cause” was first added to some New Testament texts by at least the third or fourth century. Because this phrase is referred to by Irenaeus (c. AD 130–202), noted New Testament scholar Bruce Metzger believes the addition may have been even earlier: “Although the reading with [“without a cause”] is widespread from the second century onwards, it is much more likely that the word was added by copyists in order to soften the rigor of the precept, than omitted as unnecessary.”[21] While many scholars agree with Professor Metzger, there are those who disagree. Professor David Alan Black, for example, while acknowledging that the shorter text is clearly an early reading, argues that the widespread nature of the longer reading as found in the majority of the Byzantine, Western, and Caesarean texts is a valid argument for the longer reading being original.[22]

Reference[20] is next to the "Yes" of Sinaiticus (AD 400)

Reference[20] is next to the "Yes" of Sinaiticus (AD 400)

Patristic Writings

Jerome, a fourth-century Catholic priest, scholar, and translator of the Latin Vulgate Bible,[23] stated: “In some codices [manuscripts] ‘without cause’ is added; however in the authentic codices the statement is unqualified and anger is completely forbidden, for if we are commanded to pray for those who persecute us, every occasion for anger is eliminated. ‘Without cause’ then should be deleted, since the anger of man does not work the justice of God.”[24] John Chrysostom, a Catholic bishop and a contemporary of Jerome, provided an alternative perspective on Matthew 5:22: “He who is angry without cause will be guilty, but he who is angry with cause will not be guilty, for without anger, teaching will be ineffective, judgments unstable, crimes unchecked.”[25]

Writing shortly after the time of Jerome and Chrysostom, John Cassian added his opinion to the debate concerning the verse: “The words ‘without a cause’ are superfluous, and were added by those who did not think that anger for just causes was to be banished: since certainly nobody, however unreasonably he is disturbed, would say that he was angry without a cause. Wherefore it appears to have been added by those who did not understand the drift of the Scripture.”[26]

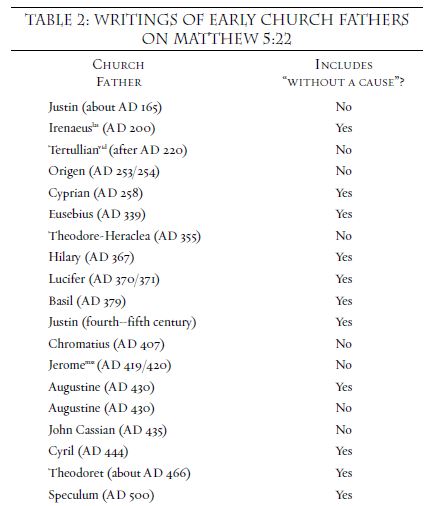

Table 2 provides a sampling of the writings of many of the early Christian Fathers and whether they include the phrase “without a cause” in their discussion of Jesus’ words in Matthew 5:22.[27]

The disparity between those of ancient date who included “without a cause” in their commentary on Matthew 5:22 and those who did not is representative of the debate that has continued to this day. Whether ancient or modern, those who include the phrase generally argue that anger is acceptable in some circumstances, while those who exclude the phrase believe Jesus was calling for anger to be eliminated from our lives.[28] Consider the contrasting views of two scholars of the twentieth century concerning the teachings of Jesus on the morality of anger. First from New Testament scholar Dale C. Allison Jr.: “Although human experience teaches the dangers of anger, . . . Jesus here [Matthew 5:22] seems to go further. He does not say that one should not be angry for the wrong reason. Nor does he imply that there might be some good reason for being angry with another. He seemingly prohibits the emotion altogether.”[29] Compare this view with that of feminist scholar Beverly Wildung Harrison: “All agree that anger is not only a disposition but a relational dynamic and in no way the deadly sin of classical tradition. Feminist theologies all but unanimously reject the patriarchal definition of the Christian life as involving ‘sacrifice’ of self and refuse the notion that the self-assertions involved in the expression of our passions, including anger, are ‘wrong.’”[30] This ongoing debate concerning anger and Christ’s words in Matthew 5:22 demonstrates that while statements from patristic authors and contemporary scholars are indeed valuable, they are not a sufficient measure in determining whether “without a cause” was original to the words of Jesus in Matthew 5:22 or a later addition.

English Versions of the Bible

The first complete English translation of the Bible did not exist until the distinguished scholar and priest John Wycliffe, along with his associates, produced a translation in 1382. The words of Jesus on anger in the Wycliffe translation are as follows:

Ye han herd that it was seid to elde men, Thou schalt not slee; and he that sleeth, schal be gilti to doom. But Y seie to you, that ech man that is wrooth to his brothir, schal be gilti to doom; and he that seith to his brother, Fy! schal be gilti to the counseil; but he that seith, Fool, schal be gilti to the fier of helle (Wycliffe New Testament, Matthew 5:21–22).[31]

Note that the phrase (or any form of the phrase) “without a cause” does not appear in the Wycliffe translation. John Wycliffe and those with whom he associated based their English translation on the Latin Vulgate, which was the standard scripture of the Roman Catholic Church. Jerome completed the Vulgate in AD 400 and believed the phrase in question “should be deleted.”[32]

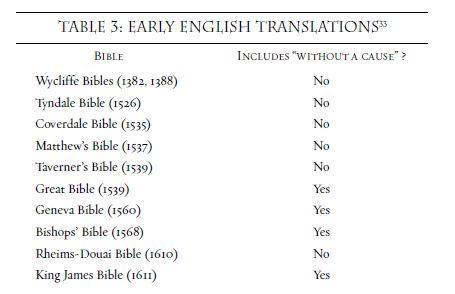

Wycliffe’s fourteenth-century English translation was followed in the sixteenth century by several printed English translations: Tyndale (1526), Coverdale (1535), Matthew’s (1537), Great (1539), Geneva (1560), and the Bishops’ Bible (1568). In 1604, King James I authorized the translation of what is now called the King James Version, attempting to resolve the controversy over which version of the Bible should be used by the Church of England. This was completed in 1611. Table 3 summarizes these English translations relative to the inclusion or exclusion of the phrase “without a cause” or its variants in Matthew 5:22.

Reference[33] is next to the title of this table: Early English Translation.

Reference[33] is next to the title of this table: Early English Translation.

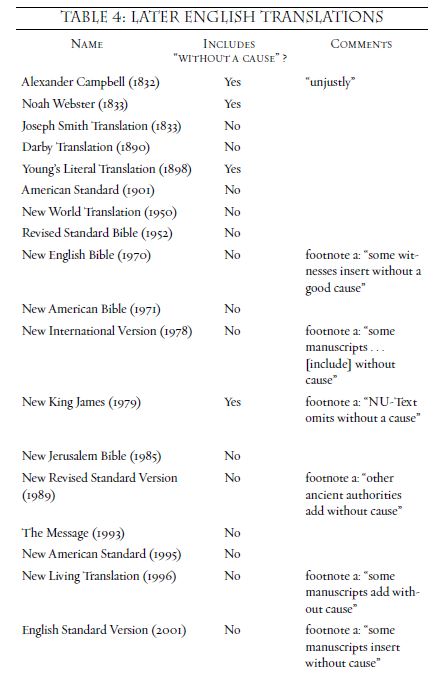

Miles Coverdale, the translator of the Great Bible, was the first of the English translators to break with the Wycliffe, Tyndale, and even his own 1535 version, and include the phrase of exception. Thomas Cromwell instructed Coverdale to base his text primarily on Matthew’s Bible, the Vulgate, and both Sebastian Münster’s and Erasmus’s Latin translations.[35] But while Coverdale was the first to include the phrase in the English Bible, because his primary sources for the translation did not include the phrase of exception, it is unclear why he chose to introduce the phrase in question. Like the King James translators that would follow, it may have been that Coverdale was influenced by what at the time was the growing scholarly acceptance of the reading of Matthew 5:22 as found in the Textus Receptus, which contains the phrase.[36] The first instance of “without a cause” appearing in an English Bible text is in the Great Bible of 1539 in the form of the word “unadvisedly” (vnaduysedly).[34] The Great Bible, Geneva Bible, and Bishops’ Bible all include the word “unadvisedly.” From the time of the publication of the King James Bible to the present day, there have been at least 291 English translations of the Bible.[37] Table 4 lists a sampling of those translations and whether they include the phrase “without a cause.”[38] Later English Versions of the Bible

While the majority of the later translations are based on the earlier Greek manuscripts and do not contain the phrase “without a cause,” some modern translations retain the phrase. The inclusion or exclusion of the phrase in Matthew 5:22 continues to be a topic of debate.

The Significance of Restoration Witnesses

The long-standing debate concerning the Savior’s words in Matthew 5:22 based on manuscripts, patristic Fathers, and Bible translations is indicative of humankind’s struggle to discover truth. Latter-day Saints are greatly blessed to have modern prophets, additional scripture, and personal as well as institutional revelation as means of identifying and understanding truth. Elder Dallin H. Oaks of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles stated: “We rely on prophets and revelation in circumstances where others rely on scholars and scholarship. . . . Latter-day Saints believe that as a source of knowledge, the scriptures are not the ultimate but the penultimate. The ultimate knowledge comes by revelation.”[39]

In terms of modern prophets and revelation, both the Joseph Smith Translation of Matthew 5:22 and the Savior’s similar sermon in the ancient Americas exclude the phrase “without a cause.” They, along with the traditional reading from the King James Version of the Bible, read as follows:

| KJV, JST, and Book of Mormon Readings | ||

| KJV, Matthew 5:22 | JST, Matthew 5:22[40] | 3 Nephi 12:22 |

| But I say unto you, that whosoever is angry with his brother without a cause shall be in danger of the judgment: | But I say unto you, that whosoever is angry with his brother shall be in danger of his judgment… | But I say unto you, that whosoever is angry with his brother shall be in danger of his judgment. |

While several General Authorities have commented on the text of Matthew 5:22, Elder Lynn G. Robbins of the Seventy gave the most detailed and representative statement on the subject:

The Lord expects us to make the choice not to become angry. Nor can becoming angry be justified. In Matthew 5, verse 22, the Lord says: “But I say unto you, That whosoever is angry with his brother without a cause shall be in danger of the judgment” (emphasis added). How interesting that the phrase “without a cause” is not found in the inspired Joseph Smith Translation . . . , nor in the 3 Nephi 12:22 version. When the Lord eliminates the phrase “without a cause,” He leaves us without an excuse. “But this is my doctrine, that such things should be done away” (3 Ne. 11:30). We can “do away” with anger, for He has so taught and commanded us.[41]

Latter-day Saint scholars have also commented on the differences in renderings of Matthew 5:22.[42] Professor John W. Welch notes that “the absence of without a cause [in latter-day scripture] has important moral, behavioral, psychological, and religious ramifications.”[43] In considering the abundance of early manuscripts which have been found since 1830, Professor Welch concludes that while the “high degree of confirmation of the [received Greek texts] speaks generally in favor of the [Book of Mormon’s] Sermon at the Temple, . . . one could not have wisely gambled on such confirmations a century and a half ago, before the earliest Greek New Testament manuscripts had been discovered.”[44]

Some critics of Joseph Smith and the scriptures of the Restoration have attempted to explain the absence of “without a cause” from the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible and the Book of Mormon by asserting that the Prophet Joseph borrowed the idea from the writings of protestant reformer John Wesley.[45] While Wesley’s commentary on Matthew 5:22—consistent with many of the early Christian Fathers—does state that the inclusion of “without a cause” “is utterly foreign to the whole scope and tenor of our Lord’s discourse” and that “we ought not for any cause to be angry,”[46] no evidence suggests that Joseph Smith knew of Wesley’s work or referred to it while translating the Book of Mormon or the Bible.

Conclusion

This chapter has shown a multitude of conflicting opinions among early texts and manuscripts, Christian Fathers, English Bible translations, and New Testament scholars (ancient and modern), concerning the legitimacy of the phrase “without a cause” in the text of Matthew 5:22. From the evidence presented, the teachings of latter-day scripture, and prophetic direction, we can conclude that the addition of the phrase “without a cause” is evidence of Nephi’s prophecy that the New Testament text would be corrupted and that truths would be lost from the New Testament and from the lives of individuals, families, and the world at large.

In addition to prophesying of truths being taken from scripture, the Lord also revealed that these truths would eventually be restored: “And after the Gentiles do stumble exceedingly, because of the most plain and precious parts of the gospel of the Lamb which have been kept back, . . . I will be merciful unto the Gentiles in that day, insomuch that I will bring forth unto them, in mine own power, much of my gospel, which shall be plain and precious, saith the Lamb” (1 Nephi 13:34). The Book of Mormon prophet Nephi recorded that additional scripture would come forth that would testify of the divine truths retained in the Bible and restore those that were taken away: “These last records [Book of Mormon, Doctrine and Covenants, Pearl of Great Price, and the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible], which thou hast seen among the Gentiles, shall establish the truth of the first [the New Testament], which are of the twelve apostles of the Lamb, and shall make known the plain and precious things which have been taken away from them” (1 Nephi 13:40).

Through modern revelation, we can be confident that in the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus clearly taught the following concerning anger: “Ye have heard that it hath been said by them of old time, that thou shalt not kill; and whosoever shall kill shall be in danger of the judgment of God. But I say unto you, that whosoever is angry with his brother shall be in danger of his judgment; and whosoever shall say to his brother, Raca, or Rabcha, shall be in danger of the council; and whosoever shall say to his brother, Thou fool, shall be in danger of hell fire.”[47] While various texts, patristic Fathers, and scholars throughout time have helped contribute to a better understanding of these teachings, the Prophet Joseph Smith restored and clarified what was originally taught by Jesus concerning anger.[48] These verses clearly teach that when we are angry, we are “in danger of” losing our intimate associations with our family and friends (“his judgment”), the Church (“the council”), and with God (“hellfire”).[49] It is not surprising that with such important relationships at risk, the adversary of all that is good would attempt to confuse us with respect to the morality of anger by tampering with the text of the New Testament.

Notes

[1] John MacArthur, The MacArthur New Testament Commentary (Revelation 12–22) (Chicago: Moody, 2000), 310.

[2] Howard W. Hunter, “No Man Shall Add to or Take Away,” Ensign, May 1981, 64. See also David E. Aune, Word Biblical Commentary Volume 52C, Revelation 17–22 (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1998), 1232; and Stephen E. Robinson, Are Mormons Christian? (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 47.

[3] Stephen L. Harris, The New Testament: A Student’s Introduction, 5th ed. (Mountain View, CA: Mayfield, 2006), 11.

[4] See Daniel K Judd, “A Scriptural Comparison Concerning Anger: 3 Nephi 22 and Matthew 5:22,” in The Book of Mormon and the Message of the Four Gospels, ed. Ray L. Huntington and Terry B. Ball (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2001), 57–76, for a detailed discussion of the morality of anger.

[5] Joseph Smith, Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, comp. Joseph Fielding Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1938), 327.

[6] Smith, Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, 9–10.

[7] Origen, Commentary on Matthew 15:14, in Bart D. Ehrman, Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why (New York: Harper Collins, 2005), 52.

[8] Jerome, Epistulae, 71.5, Ad Lucinum (J. Migne, Patrologia Latina, 22.671; Corpus Scriptorum Eccleriasticorum Latinorum, 55, 5f ), in Bruce M. Metzger and Bart D. Ehrman, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 4th ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 260n13.

[9] Bart D. Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture: The Effect of Early Christological Controversies on the Text of the New Testament (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), xi.

[10] Jeffrey R. Holland, “The Grandeur of God,” Ensign, November 2003, 70.

[11] Parablepsis is a haplographic error—a mechanical error in writing which occurs by writing only once something that occurs two or more times in the original document. The term parablepsis (“looking aside”) refers specifically to the omission of one line of text due to confusing the text with another line which has a similar ending (see Glen G. Scorgie, Mark L. Strauss, and Steven M. Voth, The Challenge of Bible Translation [Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2003], 274).

[12] Based on Royal Skousen, ed., The Original Manuscript of the Book of Mormon: Typographical Facsimile of the Extant Text (Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2001), 304.

[13] Jerald and Sandra Tanner, The Changing World of Mormonism (Chicago: Moody, 1980), 131.

[14] Metzger and Ehrman, The Text of the New Testament, 50.

[15] Philip W. Comfort and David Barrett, The Complete Text of the Earliest New Testament Manuscripts (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1999), 13–17.

[16] Comfort and Barrett, The Complete Text, 35. Carsten Peter Thiede estimates the dating of papyrus 67 at AD 70, in Rekindling the Word: In Search of Gospel Truth (Herefordshire, UK: Gracewing Fowler Wright, 1995), 27.

[17] Comfort and Barrett, The Complete Text, 34, 61. Professor Eric Huntsman of Brigham Young University examined an image of the Barcelona papyrus and provided a second witness that “without a cause” is not found in the text. See also David Allen Black, “Jesus on Anger: The Text of Matthew 5:22a Revisited,” Novum Testamentum 30, no. 1 (1988): 5n14.

[18] Barbara Aland, and others, eds., The Greek New Testament, 4th ed. rev. (New York: United Bible Societies, 1993), 13.

[19] Ehrman, Misquoting Jesus, 224–25n2.

[20] The phrase was later added to the original by a second corrector.

[21] Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, 2d ed. (New York: United Bible Societies, 2002), 11.

[22] Black, “Jesus on Anger,” 5–6.

[23] In AD 383, under the direction of Pope Damasus, Jerome began working to “produce a uniform and dependable text of the Latin Scriptures.” The confusing diversity among the several Old Latin manuscripts which Jerome had to work with made the production of a reliable, revised Bible text a particularly arduous task (Bruce M. Metzger, The Bible in Translation: Ancient and English Versions [Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2001], 31–32).

[24] Jerome in Thomas Aquinas, On Evil, trans. Jean Oesterle (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1995), 371.

[25] John Chrysostom in Aquinas, On Evil, 373.

[26] Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, eds., Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Volume 11, Slpitius Severus, Vincent of Lerins, John Cassian (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1995), 263.

[27] Aland, and others, The Greek New Testament, 13.

[28] John Cassian summarized the argument in these words: “For the end and aim of patience consists, not in being angry with a good reason, but in not being angry at all” (Schaff and Wace, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, 263).

[29] Dale C. Allison Jr., Matthew: A Shorter Commentary (London: T and T Clark International, 2004), 77.

[30] Beverely Wildung Harrison, in Andrew D. Lester, The Angry Christian: A Theology for Care and Counseling (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2003), 134.

[31] Wesley Center for Applied Theology, Wycliffe Bible, Northwest Nazarene University; http://

[32] Jerome in Aquinas, On Evil, 371.

[33] Metzger, The Bible in Translation, 56–67. The online collection of English Bibles found at http://

[34] The 1551 edition of Matthew’s Bible (New Testament) is the first English version to include the actual phrase “without a cause.”

[35] Benson Bobbrick, Wide as the Waters: The Story of the English Bible and the Revolution it Inspired (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2001), 149.

[36] The King James Version was primarily based on Beza’s and Stephanus’ editions of what would later be called the Textus Receptus. (William W. Combs, “Erasmus and the Textus Receptus,” Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal, Spring 1996, 53n86, in reference to Vaganay, Introduction to New Testament Textual Criticism, 134. Scrivener [A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, 391], citing Wetstein, says that Beza’s text differs from that of Stephanus in about 50 places.) Beza’s 1598 edition does contain the word eike, or “without a cause.”

[37] Laurence M. Vance, A Brief History of English Bible Translation, as referenced in Metzger, The Bible in Translation, 186.

[38] Sampling of Bibles adapted from Metzger, The Bible in Translation, 90–104, 117–62.

[39] Dallin H. Oaks, “Scripture Reading and Revelation,” remarks given at BYU Studies Academy dinner meeting, January 29, 1993, at Provo, Utah; transcript in author’s possession.

[40] New Testament Manuscript 2, folio 1, page 8; spelling, punctuation, and capitalization standardized (see Scott H. Faulring, Kent P. Jackson, and Robert J. Matthews, eds., Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible: Original Manuscripts [Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2004], 244).

[41] Lynn G. Robbins, “Agency and Anger,” Ensign, May 1998, 80.

[42] See Daniel K Judd, “A Scriptural Comparison Concerning Anger,” 57–76.

[43] John W. Welch, “A Steady Stream of Significant Recognitions,” in Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson, and John W. Welch, eds., Echoes and Evidences of the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2002), 335.

[44] John W. Welch, The Sermon at the Temple and the Sermon on the Mount (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book and Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 1990), 146–47.

[45] See Ronald V. Huggins, “‘Without a Cause’ and ‘Ships of Tarshish’: A Possible Contemporary Source for Two Unexplained Readings from Joseph Smith,” Dialogue 36, no. 1 (Spring 2003): 157–79.

[46] See John Wesley, Explanatory Notes Upon the New Testament (Philadelphia: Joseph Crukshank, 1791), 1:29; spelling modernized.

[47] New Testament Manuscript 2, folio 1, page 8, spelling, punctuation, and capitalization standardized (see Faulring, Jackson, and Matthews, Joseph Smith’s New Translation, 244).

[48] Also compare the KJV and JST translations of Ephesians 4:26.

[49] See Daniel K Judd, Hard Questions, Prophetic Answers: Doctrinal Perspectives on Difficult Contemporary Issues (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2004), 79–99, for more on the anger of God.