The Quest for Truth: Science and Religion in the Best of All Worlds

Robert L. Millet

Robert L. Millet, “The Quest for Truth: Science and Religion in the Best of All Worlds,” in Converging Paths to Truth, ed. Michael D. Rhodes and J. Ward Moody (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, Salt Lake City, 2011), 79–100.

Robert L. Millet was a professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University when this book was published.

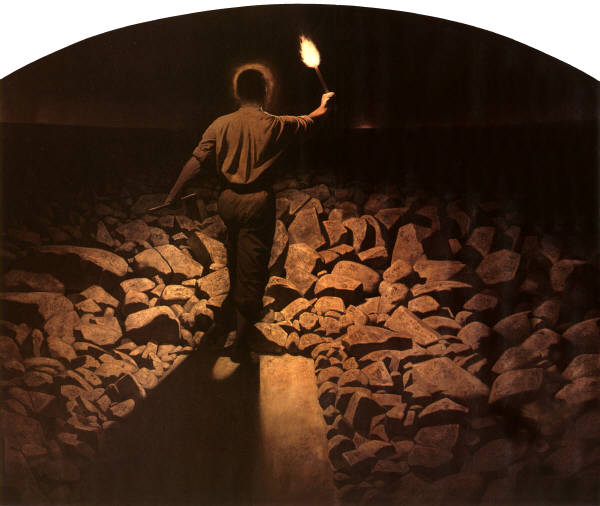

The Initial Act, by David Linn. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc., all rights reserved.

The Initial Act, by David Linn. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc., all rights reserved.

I have never been troubled much by supposed discrepancies between what scientists have hypothesized and discovered and what prophets have pondered upon and had revealed to them. It has not been particularly difficult for me to entertain certain personal beliefs about the origin of man, the age of the earth, the dimensions of the Garden of Eden, or a universal flood while at the same time acknowledging that some of my brothers and sisters in other buildings on this campus and elsewhere would disagree with my conclusions and consider me to be naive. More times than I would like to remember, during the decade that I served as dean of Religious Education, I received phone calls from irate parents who simply could not understand why Brigham Young University was allowing organic evolution courses to be taught. They would then ask what I planned to do about it, as though I were the head of the campus thought police. I would always try to be understanding and congenial, but I would inevitably remark that such things were taught at this institution because we happened to be a university; that what was being taught was a significant dimension in the respective discipline; and that we certainly would not be doing our job very well if a science student, for example, were to graduate from Brigham Young University and be ignorant of such matters.

Sometimes, if the person had not yet chosen to hang up the phone, I would go a step further: I would point out that my first two degrees were taken at BYU in psychology, a fascinating field of study to be sure, but not necessarily one whose accepted canons were in complete harmony with my personal or denominational perspectives. While I do not believe much of what Sigmund Freud or B. F. Skinner put forth as dogma, it was critical for me as a psychology major to know and understand what they taught. No decent graduate in the behavioral sciences would be worth their salt if they left this or any other institution of higher learning ignorant of either unconscious motivation or operant conditioning.

Maybe the reason I have never been very disturbed by alternative worldviews is that I became aware at an early age that we are all of us engaged in the quest for truth, for knowledge, for understanding, for meaning, for answers to timeless questions; that no matter what our own discipline might be—whether the fine arts, the physical or mathematical sciences, the social or behavioral sciences, the humanities, or the realm of religion (and for many of us, that discipline of study we call the restored gospel)—we each “see through a glass, darkly” (1 Corinthians 13:12), to quote the Apostle Paul. That is, we do not have a complete picture. We cannot view the entire scene. We too often see things not as they really are, but rather as we are. In short, sometimes our findings and declarations are more autobiographical than analytical, more a reflection of our preferences and priorities and penchants than a clear declaration of pure reality, of what is. The presuppositions we incorporate and the mental maps we construct will largely determine what we see, how we see it, and, importantly, what we do not see.

One positive step each of us could take is to adopt a healthy agnosticism. Dean Rodney J. Brown at Brigham Young University has written: “Every method available should be used to increase our understanding of life and the universe in which we live. There is a complete and correct explanation of life and the universe; the information we are seeking exists. However, we are far from knowing it. There are disagreements among religions, among scientists, and between religions and scientists. This often leaves us in the void between faith in science and religious faith. As we learn more, as we approach the truth from every direction, that void will disappear.” [1]

The Quest for Light, Not Heat

Knowing and accepting the fact that what we conclude is at best an approximation of what is, I am enchanted by this familiar but fascinating passage from the Doctrine and Covenants: “And if your eye be single to my glory, your whole bodies shall be filled with light, and there shall be no darkness in you; and that body which is filled with light comprehendeth all things” (D&C 88:67). This scripture reminds me of what Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard taught, that “purity of heart is to will one thing.” [2] If our motivation is proper, if our heart is right with the Almighty, if our desire is to contribute to the amelioration of suffering or to shine and spread light into a darkening world, and if our greatest hope is that humankind may be blessed and God glorified, then the conduit that channels light to the eye and truth to the understanding will be open and free-flowing. We will enjoy the Spirit of God in our labors, and through the influence of that member of the Godhead we will come to know “the truth of all things” (Moroni 10:5).

It is no coincidence that some of the greatest discoveries of human history have taken place during the last two centuries and, more especially, during recent decades. We should not be surprised that technological developments and medical marvels and scientific discoveries should parallel the opening of the heavens foreseen by Enoch some five millennia ago. Jehovah declared to the ancient seer, “And righteousness will I send down out of heaven; and truth will I send forth out of the earth, . . . and righteousness and truth will I cause to sweep the earth as with a flood” (Moses 7:62). Truly we are witnesses of the dual dispensation, spiritual and temporal, prophesied by Joel: “And it shall come to pass in the last days, saith God, I will pour out of my Spirit upon all flesh” (Acts 2:17; Peter paraphrasing Joel 2:28). The Light of Christ has both natural and redemptive functions. The Spirit of Jesus Christ, as it is called in the Book of Mormon (see Moroni 7:16), which serves as physical light to the eye and is the basis for law and life in the universe, is the same power by which light comes to the understanding and impressions come to the soul (see D&C 88:6–13; 84:44–47). [3]

As I have reflected on what would make me a more cooperative citizen at the university, one who could work comfortably side by side with scientists and artists and sociologists, I have drawn a few conclusions. I must admit sadly that when I was a student here at BYU and even in my first years as a faculty member, it was not uncommon for ideological grenades to be flying back and forth between the Joseph Smith Building and the Eyring Science Center. This person was labeled as godless, and that one was categorized as ignorant or naive. This faculty member hustled about to put forward his or her favorite General Authority quote, while that one relied upon a Church leader with a differing perspective. Thereby authorities were pitted against one another. Very little light, if any, was generated, but there was a great deal of heat, including much heartburn for university and college administrators. And of course the real losers during this “war of words and tumult of opinions” were the students. They admired their science teachers and valued their opinions but did not want in any way to be in opposition to what Church leaders believed and taught. They trusted their religion teachers but were not prepared to jettison their field of study. Further, such standoffs did something that for me was even more destructive: they suggested that one could not be both a competent academic and a dedicated disciple—one had to choose. And such a conclusion is tragically false. It defies everything that Brigham Young University stands for.

Maybe as Latter-day Saints we are just a little spoiled! We have so many answers to so many of life’s questions that we expect to have all answers to all questions. We tend to get downright frustrated when an answer is not readily available. But not everything has yet been discovered. Not everything has yet been revealed. Consequently, we really do need to do what many of us do not do very well—deal with ambiguity. I have said to my students many times that it is as important for us to know what we do not know as it is for us to know what we know. If we do not yet grasp with certainty how man came to be; how long it took to create the world; how Adam and Eve were placed in the Garden of Eden; how long they lived there before they fell; what the nature of a paradisiacal, amortal existence was like within Eden or how it would affect our present efforts to measure time; when death entered the world; where dinosaurs fit into the whole program; how extensively the earth was covered by the waters in the days of Noah—if we are unsure of such matters, then perhaps we ought to be a little less eager to volunteer definitive answers, a little more tentative in our conclusions and our tendencies to crusade, and a little more patient for God to uncover truth and clarify these topics. The wisest among us learn to put the presently unexplained on the shelf for a season and move on. The wisest among us are humble enough to admit where gaps exist in our own personal knowledge and in our field of study. The wisest among us remain open to new avenues of understanding and rejoice when such insight comes.

We do our students a serious disservice if we do not explain both the strengths and limitations of our discipline or field of study. In other words, it seems only right and proper for young people to understand clearly what they can learn from psychology or microbiology or philosophy or mathematics, and what they cannot learn, which questions their discipline can answer and which ones it cannot. In that process, if we are honest and humble, we will acknowledge, as Dean Brown pointed out, that “the greater curiosity for religion is purpose,” while “science explains life and the universe based on a different method of discovery. It has little interest in why things are as they are, but rather in how they are and how they came to be that way.” The picture of things as they really are “is easier to see if we include what can be learned from science and from religion. The answers to many of our questions are still in the void between faith in science and religious faith. However, as we learn more, that void will disappear.” [4]

The Value Added

It is intended that there be a value-added component at Brigham Young University that has a great deal to do with the beliefs and practices of our sponsoring Church. For some, a Latter-day Saint university is an institution of higher learning that is owned and operated by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, where Church standards such as the Word of Wisdom and a moral code are to be observed, where students, faculty, and staff strive to live in harmony, in the spirit of the highest of Christian virtues. I have been a part of several universities at which there are few such standards, and I for one would fight to maintain our distinctive atmosphere.

There is, of course, another way to see things. But before suggesting a different view, let me indicate how some have characterized a Christian college or university. One writer has asked,

Is the idea of a Christian college . . . simply to offer a good education plus biblical studies in an atmosphere of piety? These are desirable ingredients, but are they the essence of the idea? After all, through religious adjuncts near a secular campus [read institutes of religion], students could be offered biblical studies and support for personal piety while they are getting a good education, without all the money and manpower and facilities and work involved in maintaining a Christian college. . . .

The Christian college is distinctive . . . because we live in a secular society that compartmentalizes religion and treats it as peripheral or even irrelevant to large areas of life and thought. . . . The Christian college refuses to compartmentalize religion. It retains a unifying Christian worldview and brings it to bear in understanding and participating in the various arts and sciences, as well as in nonacademic aspects of campus life. [5]

In short, “underlying it all [is] the basic conviction that Christian perspectives can generate a worldview large enough to give meaning to all the disciplines and delights of life and to the whole of a liberal education.” [6]

It would seem then that a Latter-day Saint college or university seeks to do more than provide a healthy climate and an atmosphere suited to finding one’s eternal companion (as valuable as such things are). We must constantly ask ourselves, what difference does it make that there was a Joseph Smith, a Restoration, or modern revelation? How does my religion, my way of life, my revealed worldview impact what I study or the discipline in which I spend my professional life? Am I at peace, one with myself, or do I tend to compartmentalize my life, being a scientist on Monday through Saturday and a Latter-day Saint on Sunday? Is there any tie between the scriptures I read, the sermons I hear, the prayers I utter, and the work I do in my chosen field? Is my intellectual quest merely an effort to master and acclimate myself to an academic discipline, to memorize and converse in the vocabulary of the prevailing school or trend, or rather is mine a sincere effort to seek for, tap into, acknowledge, and adapt to eternal truth, to judge and assess all things thereby?

At Brigham Young University, we have been charged to engage some of life’s challenges, including hard questions, in a context of faith and mutual support, aided immeasurably by the scriptures of the Restoration and the words of living apostles and prophets. It is wrong to hide behind our religious heritage and thus neglect our academic responsibilities; there may have been a time when some faculty members at BYU excused professional incompetence in the name of religion, on the basis that BYU is different, that it is a school intent on strengthening the commitment of young Latter-day Saints. This was commendable but insufficient. It is just as myopic, however, to hide behind academics and thus cover our own spiritual incompetence. We can be thoroughly competent disciples and thoroughly competent professionals. We do not hide behind our religion, but rather we come to see all things through the lenses of our religion. “We are not only to teach purely gospel subjects by the power of the Spirit,” Elder Marion G. Romney counseled. “We are also to teach secular subjects by the power of the Spirit, and we are obligated to interpret the content of secular subjects in the light of revealed truth. This purpose is the only sufficient justification for spending Church money to maintain this institution.” [7]

Thirty years ago Professor Allen Bergin was asked to chair a session of the American Psychological Association meetings in Los Angeles. He called me and a colleague of mine in Florida and invited us to present a paper titled “Religious Values in Psychotherapy.” We accepted, knowing that we had several months to prepare. I began pushing my friend early, suggesting regularly that we get together, organize ourselves, and make arrangements for the writing of the paper. Being an extremely busy man, he put me off again and again. To make a long and painful story short, I found myself on the plane to Los Angeles saying, “Charley, we’ve just got to pull something together. This is big time. We can’t wing it; we can’t go into that meeting totally unprepared.” He agreed and reached into his coat pocket at that point, pulled out an envelope, and we began making a few notes.

The presentation was at best okay. It was not spectacular, not excellent, not even very good. It was okay. I was embarrassed and wished that we had spent at least some time ordering our thoughts. The funny thing is, a number of people surrounded us after the session to ask questions, to inquire after our own religious beliefs, and to request further information. Quite a few asked me if they could receive copies of our presentation. I was sorely tempted to indicate that all they needed to do was photocopy the envelope, but I did not yield! The occasion taught me something, a lesson that is not easily forgotten: people out there need and want what we have. Often they are not even aware of what that something is; they just want it! Brigham Young University has been established to assist the Church in extending to Latter-day Saints and to men and women of good will everywhere the very glory of God, but we must be in a position—be competent as well as humble—to let that kindly light shine. In other words, the glorious light of revealed truth must be allowed to shine forth undimmed and unrefracted.

The Quest for Unity

Certain disciplines lend themselves quite readily to the consideration of academic matters in the light of the restored gospel. Discussions of this sort will often be rather spontaneous and unpremeditated. With some areas of study this will be more difficult, and efforts to introduce religion or religious principles may be perceived as unnatural or contrived. It is not that we must create a Church-centered chemistry or a Mormon mathematics or a Latter-day Saint linguistics at BYU. More important, we must live in such a way that students and faculty have no reason to wonder where we stand on matters of faith and commitment. Obviously when we cultivate the spirit of inspiration on this campus, the truths of the gospel will be taught and learned more effectively; edification will be the order of the day. But the principle extends beyond the teaching of religion or the explanation of gospel precepts. It has much to do with how we teach, research, write, discover, display, and apply truths in all fields of study. Students who attend a calculus class taught by an instructor imbued with the Spirit of God will be richly rewarded, even if a religious principle is never mentioned. Students who counsel with a professor who is striving to keep the commandments of God will be enriched and strengthened from the engagement. Students who study with faculty members who are loyal to the Church and its leaders, who are earnestly seeking to put first in their lives the things of God’s kingdom, will come away from the BYU experience with an informed perspective that will tower above that which they might have received elsewhere. In short, the quest for personal and institutional spirituality must underlie all we do.

The Prophet Joseph Smith explained, “It was my endeavor to so organize the Church, that the brethren [and sisters] might eventually be independent of every incumbrance beneath the celestial kingdom, by bonds and covenants of mutual friendship, and mutual love.” [8] Elder Dallin H. Oaks declared to BYU students, “Love and tolerance are pluralistic, and that is their strength, but it is also the source of their potential weakness. Love and tolerance are incomplete unless they are accompanied by a concern for truth and a commitment to the unity God has commanded of his servants. Carried to an undisciplined excess, love and tolerance can produce indifference to truth and justice and opposition to unity. . . . The test of whether we are the Lord’s is not just love and tolerance, but unity.” [9]

President Brigham Young explained that “if this people would live their religion, and continue year after year to live their religion, it would not be many years before we should see eye to eye; . . . and the veil that now hangs over our minds would become so thin that we would actually see and discern things as they are.” [10] “We are seeking to establish a oneness,” Elder John Taylor observed,

under the guidance and direction of the Almighty. . . . If there is any principle for which we contend with greater tenacity than another, it is this oneness. . . . To the world this principle is a gross error, for amongst them it is every man for himself; every man follows his own ideas, his own religion, his own morals, and the course in everything that suits his own notions. But the Lord dictates differently. We are under his guidance, and we should seek to be one with him and with all the authorities of His Church and kingdom on the earth in all the affairs of life. . . . This is what we are after, and when we have attained to this ourselves, we want to teach the nations of the earth the same pure principles that have emanated from the great Eloheim. We want Zion to rise and shine that the glory of God may be manifest in her midst. . . . We never intend to stop until this point is attained through the teaching and guidance of the Lord and our obedience to His laws. Then, when men say unto us, “you are not like us,” we reply, “we know it; we do not want to be. We want to be like the Lord, we want to secure His favor and approbation and to live under His smile, and to acknowledge, as ancient Israel did on a certain occasion, ‘The Lord is our God, our judge, and our king, and He shall reign over us.’” [11]

We must have courage, the moral courage to stand up for what makes Brigham Young University distinctive, the moral courage to put down all that seeks to erode or hack away at that distinctiveness. This may prove to be a painful process. But there is a greater pain, the pain associated with knowing that we could have contributed to the realization of prophetic dreams concerning this place but chose to wait out the storm instead, only to find after the storm that we had lost something that cannot be retrieved. It is the pain known only to those who might have but did not.

Viewing all things through the lenses of the Restoration will then follow naturally and be reflected in the teachings and writings of men and women with regenerate hearts. And as we begin to do what we alone have been charged to do here at Brigham Young University, we will become a light to the religious and academic world; such will come, ironically, because we sought first the glory of God (see Matthew 6:33). In other words, if BYU is ever to achieve its prophetic destiny, is ever to make its mark in the world as a spiritual and intellectual Mount Everest, it must more closely approximate Mount Zion. As time passes, as President Spencer W. Kimball prophesied, there will be “a widening gap between this university and other universities both in terms of purposes and in terms of directions.” [12]

The Best of All Worlds

I suppose I am suggesting that Brigham Young University is in fact “the best of all worlds,” to borrow a phrase from Voltaire. It is an institution that is much more concerned with eternal discovery and spiritual certainty than with anything else. It is the best of all worlds in that it is a product of sacred sacrifice, an enterprise sustained by the tithes and prayers of Latter-day Saints all over the globe. It is the best of all worlds because it contains, as an article of its mission statement, the bold and distinctive declaration that it exists principally to assist individuals in their quest to obtain eternal life. It encourages character first and promotes personal integrity above all things, because its faculty and staff care even more about the spiritual growth and maturity of the students than we care about their intellectual growth (in fact, we care very much about both). It is the best of all worlds because we believe in the Almighty God, acknowledge him as our Father in Heaven, confess freely and unashamedly that Jesus of Nazareth was and is the Savior and Redeemer of humankind, and are poignantly aware that the clarity of our teaching and the success attending our research will depend largely upon our personal purity and our loyalty to true principles and true prophets.

BYU is the best of all worlds also because we have a perspective and a worldview that does not allow for a complete separation of the temporal and the spiritual. In a revelation given to the Prophet Joseph Smith in September 1830, the Savior declared that “all things unto me are spiritual, and not at any time have I given unto you a law which was temporal” (D&C 29:34). At the same time, we understand that the means, the methods for learning facts and uncovering truth may differ. On the relationship between our rational faculties, the power of reason, and our spiritual capacities, the place of revelation, Elder Oaks has written, “Reason is a thinking process using facts and logic that can be communicated to another person and tested by objective (that is, measurable) criteria. Revelation is communication from God to man. It cannot be defined and tested like reason. Reason involves thinking and demonstrating. Revelation involves hearing or seeing or understanding or feeling. Reason is potentially public. Revelation is invariably personal.” Then, in stressing the innate limitations upon reason, he continued, “Despite the importance of study and reason, if we seek to learn of the things of God solely by this method, we are certain to stop short of our goal. We may even wind up at the wrong destination. Why is this so? On this subject God has prescribed the primacy of another method. To learn the things of God, what we need is not more study and reason, not more scholarship and technology, but more faith and revelation.” [13]

Now to be sure, revelation for us does not represent a mystical distancing of one from reality, a transcendental separation of one’s reason from the receipt of a revelation. The will of God is meant to be understood and to be as satisfying to the mind as it is to the heart. We are never instructed to give ourselves wholly to feelings any more than we are instructed to surrender all thought. In a revelation given to Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery in April 1829, we find these words: “Yea, behold, I will tell you in your mind and in your heart, by the Holy Ghost, which shall come upon you and which shall dwell in your heart” (D&C 8:2). My colleague Joseph McConkie has commented on this passage:

We observe that neither [Oliver] nor Joseph was to experience any suspension of their natural faculties in the process of obtaining revelation. Quite to the contrary, their hearts and minds were to be the very media through which the revelation came. Prophets are not hollow shells through which the voice of the Lord echoes, nor are they mechanical recording devices; prophets are men of passion, feeling, intellect. One does not suspend agency, mind, or spirit in the service of God. It is . . . with heart, might, mind and strength that we have been asked to serve, and in nothing is this more apparent than the receiving of revelation. There is no mindless worship or service in the kingdom of heaven. [14]

Reconciliation and Respect

During the last decade, I have been immersed thoroughly in the work of religious outreach and interfaith relations. I have spent hundreds if not thousands of hours seeking to understand and be understood. It has been a taxing labor, one that indeed has stretched my soul and expanded my intellect. There have been setbacks, to be sure, in the form of misunderstanding on the part of our respective religious constituencies, in the form of collegial misunderstanding and suspicion that I was giving away the store or compromising our distinctive doctrine. Most people who have drawn this conclusion—a faulty one, to be sure—have done so under the impression that significant progress cannot be made between otherwise warring religious factions unless someone compromises or concedes. I have come to know for myself, and have had it reinforced again and again, that this is not the case, that “convicted civility” [15] between persons of differing traditions can exist if we learn how to listen respectfully, be open to the mind-boggling idea that we can actually learn something from another who has differences, and be more concerned with winning a friend than winning an argument. When relationships of trust and respect and love are in place, doors open, knowledge flows, and the Spirit of the Lord works wonders. The Prince of Peace explained, “Where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them” (Matthew 18:20).

If my Latter-day Saint colleagues and I can enjoy such a sweet brotherhood and sisterhood with a growing number of Evangelical Christians—a group with whom we have been in intense dialogue since 2000—then surely it is possible for men and women of faith who labor in varying avenues of science to enjoy cordial and collegial relationships with those involved in the study and teaching of religion, especially at Brigham Young University, the best of all worlds. Our epistemological thrusts may be different. Our presuppositions may be different. Our tests of validity and reliability may be different. But our hearts can be united as we strive to look beyond the dimensions of our disciplines toward higher goals. Some things we may and should reconcile here and now, while other matters may await further light and truth and additional discovery. “With an increasing body of facts,” Elder John A. Widtsoe observed,

there must needs be a constant demand for reconciliation among old and new conclusions. Such reconciliation should not be difficult, since all proper human activities aim to secure truth. Every person of honest mind loves truth above all else. In the proposed exchange of the new for the old, religion has often been in apparent conflict with science. Yet, the conflict has only been apparent, for science seeks truth, and the aim of religion is truth. That they have occupied different fields of truth is a mere detail. The gospel accepts and embraces all truth; science is slowly expanding her arms, and reaching into the invisible domain, in search of truth. The two are meeting daily. . . . Earnest attempts at reconciliation are rewarded with full success. Occasional failures are usually due to the mistake of alone trying religion. . . . Religion has an equal right to try science. Either method, properly applied, leads to the same result: truth is truth. [16]

The Discipline of Faith

Faith has its own type of discipline. Some things that are obvious to the faithful sound like the gibberish of alien tongues to the faithless. The discipline of faith, the concentrated and consecrated effort to become single to God, has its own reward. It is worth considering the words of a revelation given in Kirtland, Ohio. The early Saints were told, “And as all have not faith, seek ye diligently and teach one another words of wisdom; . . . seek learning, even by study and also by faith” (D&C 88:118). We note that the counsel to seek learning out of the best books is prefaced by the negative clause, “And as all have not faith.” One wonders whether what was not intended was something like the following: Since all do not have sufficient faith—have not “matured in their religious convictions” to learn by any other means [17]—then they must seek learning by study, through the use of the rational processes. Perhaps learning by studying from the best books would then be greatly enhanced by revelation. Honest truth seekers will learn things in this way that they could not know otherwise. This may be what Joseph Smith meant when he taught that “the best way to obtain truth and wisdom is not to ask it from books, but to go to God in prayer, and obtain divine teaching.” [18] It is surely in this same context that another of the Prophet’s famous yet little-understood statements finds meaning. “Could you gaze into heaven five minutes,” he declared, “you would know more than you would by reading all that ever was written on the subject” of life after death. [19] “I believe in study,” President Marion G. Romney stated. “I believe that men learn much through study. As a matter of fact, it has been my observation that they learn little concerning things as they are, as they were, or as they are to come without study. I also believe, however, and know, that learning by study is greatly accelerated by faith.” [20]

President Harold B. Lee expressed the following to Brigham Young University students just weeks before his death in 1973: “‘The acquiring of knowledge by faith is no easy road to learning. It will demand strenuous effort and continual striving by faith. In short, learning by faith is no task for a lazy man.’ Someone has said, in effect, that ‘such a process requires the bending of the whole soul, the calling up from the depths of the human mind and linking the person with God. The right connection must be formed; then only comes knowledge by faith, a kind of knowledge that goes beyond secular learning, that reaches into the realms of the unknown and makes those who follow that course great in the sight of the Lord.’” [21] On another occasion, President Lee taught that “learning by faith requires the bending of the whole soul through worthy living to become attuned to the Holy Spirit of the Lord, the calling up from the depths of one’s own mental searching, and the linking of our own efforts to receive the true witness of the Spirit.” [22]

No matter what our academic discipline, it is vital that we maintain our allegiance to the kingdom of God and never allow our discipline to dilute our discipleship. I made a decision many years ago that as a Latter-day Saint I was in this for the long haul and would never allow my faith to be held hostage by what had or had not been discovered or confirmed by external evidence. A while ago I spoke with an associate of another faith. I asked him what he thought of the recent claims by some to have located the very tomb and bones of Jesus Christ. To my surprise, he expressed serious concern. Almost jokingly I followed up: “Well, what would you do if it was proven beyond all doubt [which I rather think is utterly impossible] that those bones are indeed the very bones of Jesus of Nazareth?” He paused for a moment, reflected carefully, and said: “I guess I would have to denounce Christianity.” “You must be kidding?” I fired back. “No,” he said, “I take evidence very seriously.” My last question, one that went unanswered, was, “And what about the evidence that lies deep within your soul, the evidence that burns within your bosom, the God-given assurance that Jesus lived, taught, performed miracles, suffered and died for us, and rose from the tomb in glorious immortality? What of that evidence?”

Elder Neal A. Maxwell has written, “It is [my] opinion that all the scriptures, including the Book of Mormon, will remain in the realm of faith. Science will not be able to prove or disprove holy writ. However, enough plausible evidence will come forth to prevent scoffers from having a field day, but not enough to remove the requirement of faith. Believers must be patient during such unfolding.” [23]

Hugh Nibley, one of the great defenders of the faith, stated,

The words of the prophets cannot be held to the tentative and defective tests that men have devised for them. Science, philosophy, and common sense all have a right to their day in court. But the last word does not lie with them. Every time men in their wisdom have come forth with the last word, other words have promptly followed. The last word is a testimony of the gospel that comes only by direct revelation. Our Father in heaven speaks it, and if it were in perfect agreement with the science of today, it would surely be out of line with the science of tomorrow. Let us not, therefore, seek to hold God to the learned opinions of the moment when he speaks the language of eternity. [24]

I have learned a few things over the years. I thank God for the formal education I have received, for the privilege it is (and I count it such) to have received university training and to have earned bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees. Education has expanded my mind and opened conversations and doors for me. It has taught me what books to read, how to research a topic, and how to make my case or present my point of view more effectively. But the more I learn, the more I value the truths of salvation, those simple but profound verities that soothe and settle and sanctify human hearts.

I appreciate knowing that the order of the cosmos points toward a providential hand; I am deeply grateful to know, by the power of the Holy Ghost, that there is a God and that he is our Father in Heaven. I appreciate knowing something about the social, political, and religious world into which Jesus of Nazareth was born; I am deeply grateful for the witness of the Spirit that he is indeed God’s Almighty Son.

I appreciate knowing something about the social and intellectual climate of nineteenth-century America; I am grateful to have a living witness that the Father and the Son appeared to Joseph Smith in the spring of 1820 and that what followed that theophany has been of God. In short, the more I encounter men’s approximations to what is, the more I treasure those absolute truths that make known “things as they really are, and . . . things as they really will be” (Jacob 4:13; compare D&C 93:24). In fact, the more we learn, the more we begin to realize what we do not know, the more we feel the need to consider ourselves “fools before God” (2 Nephi 9:42).

Conclusion

When I think about all that has been done on this campus over the decades—about the prayers of dedication offered, the sermons preached, the thousands upon thousands of students prepared for meaningful service in a world that desperately needs them, and the fact that Apostles and prophets have walked and talked and taught here—I want to quote the words of the Lord to Moses: “Put off thy shoes from off thy feet, for the place whereon thou standest is holy ground” (Exodus 3:5). There are things we are able to do here that are neither permitted nor comprehended elsewhere. If we as a community are willing to work with single-minded dedication to bring to pass God’s righteousness, we will indeed become “a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, an holy nation, a peculiar people” who “shew forth the praises of him who hath called [us] out of darkness into his marvellous light” (1 Peter 2:9). The God of our fathers has his eye on this campus. This I know.

Thirty-four years ago I sat in the Smith Family Living Center wondering whether anything of worth would ever materialize in my life. I had completed both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in psychology here at BYU, had been accepted into a PhD program in clinical psychology, and, for all intents and purposes, everything should have been fine. There was only one major problem—I was not happy. I did not feel that I should continue my work in psychology, and in general I was wrestling with what I wanted to be when I grew up. One young faculty member, sensing my frustration and having desires akin to mine, sat and talked with me for over two hours. He read a statement by Charles H. Malik, former president of the United Nations General Assembly, a pronouncement that seems to me more prophetic as the years go by. “One day a great university will arise somewhere—I hope in America—to which Christ will return in His full glory and power, a university which will, in the promotion of scientific, intellectual, and artistic excellence, surpass by far even the best secular universities of the present, but which will at the same time enable Christ to bless it and act and feel perfectly at home in it.” [25]

I felt the spirit of those words in 1973, and they brought hope and comfort to my heart; I still feel them as poignantly now. Such things will indeed come to pass. They will come to pass because men and women fully committed to the gospel of Jesus Christ—students, faculty, and staff—will take a leap of faith, will walk a few steps ahead of the light, and maybe even a bit into the darkness. Then will shine forth that kindly light amidst the encircling gloom in the world, [26] and Brigham Young University will have become a city on a hill. That we may properly prepare for our date with destiny is my prayer.

Notes

[1] Rodney J. Brown, “A Scientist’s View of Life from a ‘Mormon’ Perspective,” Fundamentals of Life, ed. Gyula Palyi, Claudia Zucchi, and Luciano Caglioti (New York: Elsevier, 2002), 518.

[2] Søren Kierkegaard, Purity of Heart Is to Will One Thing (New York: Harper, 1956).

[3] Elder Bruce R. McConkie has suggested that the power of God, the Light of Christ, faith, and priesthood power may well be the very same power. See A New Witness for the Articles of Faith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1985), 257.

[4] Brown, “A Scientist’s View,” 519.

[5] Arthur Holmes, The Idea of a Christian College (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1987), 5, 9.

[6] Holmes, Idea of a Christian College, 7.

[7] Marion G. Romney, “Temples of Learning,” BYU Annual University Conference, September 1966.

[8] Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1957), 1:269.

[9] Dallin H. Oaks, “Our Strengths Can Become Our Downfall,” in 1991–92 BYU Speeches of the Year (Provo, UT: BYU Publications, 1992), 114; emphasis added.

[10] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses (Liverpool: F. D. Richards, 1851–86), 3:194.

[11] John Taylor, in Journal of Discourses, 11:346–47; emphasis added.

[12] Spencer W. Kimball, The Second Century of Brigham University (Provo, UT: BYU Publications, 1975), 4.

[13] Dallin H. Oaks, The Lord’s Way (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1991), 16–17, 19.

[14] “The Principle of Revelation,” in Studies in Scripture, vol. 1: The Doctrine and Covenants, ed. Robert L. Millet and Kent P. Jackson (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1989), 83.

[15] This term was coined by my evangelical Christian friend Richard J. Mouw in Uncommon Decency: Christian Civility in an Uncivil World (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1992).

[16] John A. Widtsoe, In Search of Truth: Comments on the Gospel and Modern Thought (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1963), 15–16.

[17] B. H. Roberts, quoted by Harold B. Lee, in Conference Report, April 1968, 129.

[18] Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, comp. Joseph Fielding Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1938), 191.

[19] Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, 324.

[20] Marion G. Romney, Learning for the Eternities (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1977), 72; emphasis added.

[21] Harold B. Lee, “Be Loyal to the Royal Within You,” in 1973 BYU Speeches of the Year (Provo, UT: BYU Publications, 1974), 91.

[22] Harold B. Lee, in Conference Report, April 1971, 94; emphasis added.

[23] Neal A. Maxwell, Plain and Precious Things (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1983), 4.

[24] Hugh Nibley, The World and the Prophets (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: FARMS, 1987), 134.

[25] Charles H. Malik, “Education and Upheaval: The Christian’s Responsibility,” Creative Help for Daily Living 21 (September 1970): 10.

[26] See Boyd K. Packer, The Holy Temple (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1980), 184.