XYZ

Rhoda Perkins Wakefield and Roberta Flake Clayton, "XYZ," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 827-834.

Rhoda Elizabeth Perkins Young

Author Unknown/

Maiden Name: Rhoda Elizabeth Perkins

Birth: March 20, 1862; Bountiful, Davis Co., Utah

Parents: Jesse Nelson Perkins and Rhoda Condra McClelland[1]

Marriage: Brigham Young Jr.;[2] May 17, 1886

Children: Jessie Alice (1888)

Death: August 26, 1927; Taylor, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Taylor, Navajo Co., Arizona

One of the saddest, sweetest stories to be found in the research into the lives of the pioneer women of Arizona was the one of Rhoda Elizabeth Perkins Young, which has been given in part by her niece and namesake Rhoda Perkins Wakefield.

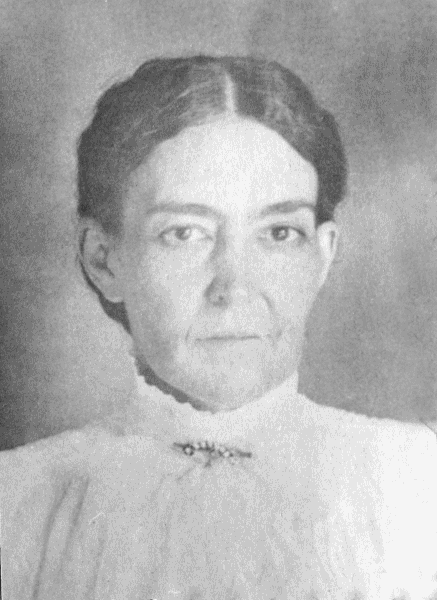

Rhoda Elizabeth Perkins Young. Photo courtesy of Ida Webb collection, Taylor Museum.

Rhoda Elizabeth Perkins Young. Photo courtesy of Ida Webb collection, Taylor Museum.

She was reared in a comfortable home in Bountiful, Utah, surrounded by orchards of fruit and fields of grain and was happy in the love of her parents and seven brothers. They had acquired some property in land, sheep, and cattle, and everything looked promising for their future success, when they were called to leave their home and go to Southern Utah and help colonize that part. Then again President Young called them to move on, this time to Arizona, giving them their choice of any place they wished to settle. They came first to the Salt River Valley, arriving in Lehi, (first called Fort Utah), March 7, 1878. Here her father Jesse N. Perkins was called and set apart by Erastus Snow as a presiding elder over all the Saints in Salt River Valley. On account of some serious sickness, Mr. Perkins was released and given permission to move to a cooler climate. They arrived in the little settlement now called Taylor on January 4, 1882.

In June of the following year, Sister Wilmirth East organized a Relief Society in the Perkinses’ home, and Rhoda C. Perkins was chosen and set apart as the first Relief Society president.[3] The daughter, Rhoda Elizabeth, was the first Sunday School secretary. Her father, Jesse Nelson, was the first postmaster in Taylor. Three years later, he and his oldest son, John, contracted smallpox through their post office work and died from this disease in March 1883.[4]

Rhoda was the only sister of seven brothers and by them was greatly admired, humored, and almost idolized; she fell not easy prey to the country swain, though many of them pressed their suit without any response from this beautiful girl. She had an air of superiority which impressed all who knew her. With this charm and a face and form beyond reproach, it was no wonder she attracted the attention of Brigham Young Jr., son of the famous Mormon colonizer and President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Rhoda had at last found a man to whom she could give her love and devotion, even though she had to share with four other wives.[5] She was proud of her noble husband, who was an apostle of the Lord. Young Brigham was also young at heart, full of wit and humor. He, too, was a favorite, a good speaker. Gifted with the Young family’s oratory, he was greatly admired, especially by the women folk.

Brigham and Rhoda were married [missing words] Saints. Under the Edmunds Tucker Bill, the name [by] which Rhoda would have been so proud to be called had to be concealed for a time. The marriage was not publicized. Only her family and a few choice friends knew she bore the honorable name of the wife of Brigham Young Jr. Rhoda returned to her mother’s home, her father had now passed away, and outwardly things were as before, except she could not mingle so freely with the young people of the ward. Rhoda, an accomplished seamstress, worked with her mother, happy in their work and devotion to each other and the secret which they shared.

When in the course of events it became apparent that she was to become a mother, her situation was much like Mary of old. She pondered many things in her heart and, in spite of some unkind criticism, knew within her heart there was no stain on her name or character. At the time of her marriage, leaders of the church, in fact all polygamists, were hunted down, imprisoned, fined by a law intended to destroy the Mormon Church. Officers of the law hunted down every apprehended polygamist. More especially, the high Church authorities were watched day and night; [they] were literally hounded and persecuted. Many of the men were imprisoned from six months to three years and in some cases paying fines from $500 to $5000. These were trying, heart-rending times to the wives who had to bear these persecutions and suffered much anxiety and fear over the dangers to their husbands, of which at times no word might be received for months. Volumes could be written of those dark, sad days, but this story only concerns Rhoda E. Perkins Young and her little daughter, Jessie Alice Young, who was born January 15, 1888. She grew up in the home of her grandmother, loved and tenderly cared for by her mother, with not much knowledge of her father, who was constantly laboring among the Saints at home or abroad. Her main associates were her uncles and many cousins, which but partly filled the place of the brothers and sisters she longed for. Her father had provided means to keep them comfortable (stock in co-op stores and flour mills to keep them clothed and fed), but Alice longed for more and would say, “I would gladly give all I have for some little brothers and sisters like my cousins have.”

Alice Young, daughter of Brigham Jr. and Rhoda Perkins Young. Photo courtesy of Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

Alice Young, daughter of Brigham Jr. and Rhoda Perkins Young. Photo courtesy of Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

Through all these trials Rhoda remained faithful to the principle of plural marriage. Although being denied the association of her husband, her love for him never wavered, and she honored him as a servant of the Lord who was devoting most of his life to the ministry. As his wife, she too sought the spiritual part and took a great interest in gathering genealogy and assisting her brother Brigham in getting the temple work done for their departed relatives. In the fall of 1899, arrangements were made for her to come to Salt Lake, where she would stay at the Lion House as long as she would care to remain. Imagine her disappointment upon arrival to find that her husband was in the East on a Church assignment. After about three month’s stay, during which time she did some work in the Salt Lake Temple for her mother’s close relatives who had recently passed away, Rhoda returned with her little daughter, Jessie Alice, to their home in Taylor, where she remained until her death.

Alice grew up to be a beautiful young woman, gifted with her father’s brilliance. Born to the stage, like her illustrious grandfather and others of his family, she took a leading part in the ward’s activities. With her mother’s culture and refinement, she was very outstanding and was admired by many, including the best of the young men. Although she had many admirers, she did not accept their attentions to where she could become a wife. She had high ideals of marriage, but remained close to her now widowed mother, now in poor health, who mourned deeply for her husband. The co-op institutions failed, and Alice sought employment. There was little to be had in Taylor. She was working in Holbrook as a telegraph operator when she was suddenly seized in the flu epidemic, which terminated in her death, March 5, 1920 [age thirty-two], leaving her mother to mourn in sorrow for eight more years.[6] Who could attempt to describe the disappointment of this fine woman? She had given her all, what had she to show for it? She had the gospel and brothers who held the priesthood to bless and comfort, and the assurance of a husband and lovely daughter waiting for her on the other side where with them she could find happiness at last.

Ellis and Boone:

The subject of polygamy has been mentioned, or not been mentioned, in many of these sketches, depending mostly upon when the account was written. For some of these women, it was a conscious religious decision to enter into a polygamous marriage. Others were widows who accepted it as a means of financial support or a way to have more children. Sometimes the marriages were happy, and others ended in separation or divorce. Generally the women provided some of their own support, either during the marriage or during long years of widowhood.

When Carolyn O’Bagy Davis, an author who grew up in Utah and has some Mormon ancestry but who is not a Latter-day Saint, was asked to write a biography of Julia Abegg Call, the fourth wife of Anson Bowen Call, Davis found that her “true dilemma . . . was the emotional unease and moral conflict that surfaced whenever the topic of [Julia’s] polygamous life was addressed.”[7] Eventually Davis found some resolution for her conflicted feelings through talking to Jeanette Done of Tucson. Davis wrote that Done’s “comment was that in today’s world, I would be hard pressed to find many devout Mormon women who would willingly enter into a polygamous relationship. Her observation was that times were vastly different from the 1880s, when the church had recommended polygamy for some of its members, and women today and modern expectations were also very different. She realized that my instinctive reaction to polygamy was from a contemporary viewpoint, but that it would not be dissimilar for a modern Mormon woman. That advice greatly eased my mind.”[8]

Jeanette Done was correct that today, even within the Church, attitudes toward polygamy are vastly different from those in the nineteenth century. The Manifesto, written in 1890, was ambiguous enough that three years later Jesse N. Smith recorded some speculation in his journal. He was in Junction, Utah, and wrote that the wife of Charles Harris asked, “When will the manifesto be recalled?” to which Smith replied, “When the Lord wills.” Then Mrs. Harris asked Smith whether a man with two wives should divorce one of them.[9] Men and women in the Church had defended the doctrine for so long that it was hard to envision a permanent change. In fact, RFC herself defended the practice of polygamy even in the 1960s.

A second, but less discussed, doctrine that was changed by President Wilford Woodruff in 1894 was the practice of adoption to a Church official or other prominent priesthood bearer. Both doctrines were based on the idea that ordinances for salvation must be performed on earth, and as noted in a history of the Genealogical Society of Utah, “The Saints apparently believed [adoption] would secure the salvation of their families in a worthy priesthood lineage if their own progenitors did not accept the gospel in the next life.”[10] Jonathan Stapley discussed this early practice of adoption and the change in thinking after Woodruff’s revelation. He wrote, “Perhaps the greatest ramification of the adoption revelation was a shift away from micromanaging eternal relationships to a position of aspiration—a belief that a just God will ensure that no blessings are kept from the faithful.”[11] Stapley’s summation is equally applicable to understanding why many of these women were willing to live polygamy, even in extreme circumstances as did Rhoda Perkins Young, living completely apart from her husband for so many years. To many of these women, the possibility of a better eternal reward was worth any sacrifice on earth.

Rhoda Elizabeth Perkins Young died of tuberculosis on August 26, 1927, at Taylor.

Susan Saphronia Hamilton Whitworth Youngblood

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP

Maiden Name: Susan Saphronia Hamilton

Birth: December 15, 1844; Dallas, Monroe Co., Mississippi

Parents: Isaiah Hamilton and Evaline Bailey Walpole/

Marriage 1: Charles Calvin Whitworth; February 7, 1861

Children: Charles Calvin (1862)

Marriage 2: James Irvin Youngblood; November 2, 1868

Children: Olive Electa (1870), Benjamin Franklin Porter (1871), Evaline Elizabeth (1874), Effa Augusta (1876), Claude Thomas (1879)

Death: June 20, 1926; Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Down in the far-famed, sunny South in the little town of Dallas, Monroe County, Mississippi, was born on December 15, 1844, a beautiful black-haired, black-eyed baby girl. She came to the home of Isaiah and Evaline Bailey Walpole Hamilton, and the little Susan was their twelfth child. She was royally welcomed, for doesn’t the Bible say “Children are a gift from God and blessed is the man who hath his quiver full of them?”[12]

Living on a plantation, these children had an outdoor, carefree life, and although her father died when Susan was only nine years of age, he left his family well provided for.

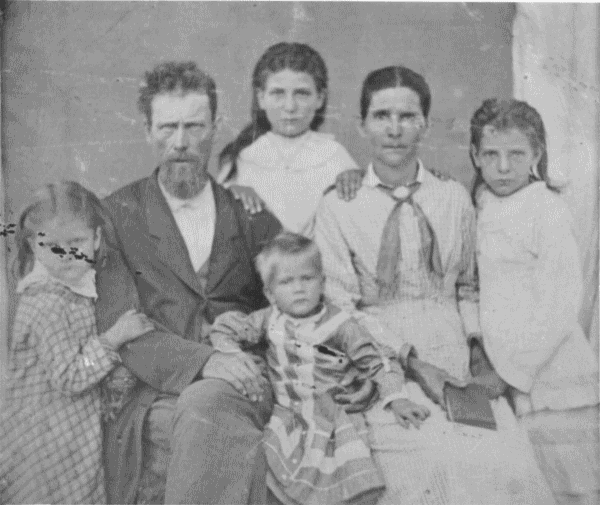

James and Susan Youngblood with children, left to right: Effie Augusta, Olive Electa (back), Claude Thomas, Eveline Elizabeth. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

James and Susan Youngblood with children, left to right: Effie Augusta, Olive Electa (back), Claude Thomas, Eveline Elizabeth. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Susan was blessed with many talents, among them that of music, which she expressed in her every movement, learning the dances of the [blacks] on the plantation, especially the double shuffle, back step, cake walk, and all the other fancy steps she saw. She possessed a beautiful voice and charmed [all] with her singing and playing of the violin. It was very unusual for a girl to “fiddle,” and some of the older, more sanctimonious people thought she was very wicked, and when they heard her clear, birdlike whistle they knew she would come to some bad end. She was very popular with the youngsters and always had a group of admirers around her.

The mode of travel in those pre-war days was on horseback, and Susan became famous for her good riding. With her long, flowing riding habit, she dashed away on her spirited pony.

In those Southern climates, people developed earlier, and it was not unusual for girls to marry when fifteen years old, and Susan married at that age on February 7, 1861. Her young husband, Charles C. Whitworth, who was born July 5, 1844, was stricken with typhoid fever, and died before they were married a year. The grief of this beautiful young bride was intensified by the knowledge that she was to become a mother, and five months after his father died, baby Charles was born. Now there was a baby to care for, and he must have every attention. Susan went home to live with her widowed mother, who could give her the kind sympathy she needed.

During these trying times of their widowhood, the Civil War broke out, the horror of which can never be written. Living in the extreme southern part of Mississippi, they were not near the battle front or near the firing line, but there was the grief of widows, fatherless, and sweethearts whose loved ones had given their lives in defense of their homes and families.

During the four years of the war, the women had to do the work formerly done by the slaves, and Susan willingly did her part. She would yoke her oxen and with them plow all day, then plant the corn and cotton, and then the crop had to be gathered. The only help obtainable were men who were too old or boys who were too young for war service. These were not very efficient, and so the women went to the fields to pick the cotton, take it to the gin, and, when it was in the bale, sell it.

When the blockade was up at Oxford, the price of cotton was very high there. It was very dangerous to try to run the blockade, but Susan was afraid of nothing, so she took her cotton and with her some of her friends decided to run the risk. They reached their destination safely and sold their cotton at one dollar a pound. All went well until the first night out of Oxford. They had made camp when a bunch of pickets rode up.[13] This filled the little group with fear as they knew the seriousness of their condition.

Susan had a solution, as she usually had, and told one of her friends to join her in giving a supper and breakfast to the soldiers. In return for this kindness, the two women were told to be the last to leave camp, and, when they came to a left hand road, to leave the main highway and take this route, and to drive as fast as their oxen [horses or mules?] could go and they would not be molested. They followed these directions and reached home safely while the others were captured and taken back to Oxford and their money confiscated. There was too much danger so they did not try this again.

Finally the war was over and six years of widowhood for Susan when she met, loved, and married James Irvin Youngblood in 1868. He was born October 4, 1837. They had five children. This marriage, like her first, was a very happy one, but again it was too good to last, and when her youngest child was only four years old, her second husband passed away January 13, 1883. The family was living in Arkansas at the time.[14]

Since her husband’s youth, he never had belonged to any religion, but about two years before his death, Elder John Price from Millcreek, Utah, came to their country as a preacher representing The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, commonly known as the Mormon Church. He believed all the words taught by this young elder to be the truth, and in April 1882, he became a member of this church by baptism. In a kind manner, he tried to get Susan to see the truth as he did but never coaxed or persuaded her. She was a member of the Missionary Baptist Church and did not take to his new ideas very readily, but after studying it and considering well for nearly a year, she became convinced that he was right and joined the true church. In August of the same year, she was baptized by Elder John Price.

Her husband was very devoted to the elders and used to follow them around, leaving Susan alone. To this she became bitter. One day, as her husband was returning home, he noticed a light coming from the home, a strange light, one he had never seen before. Upon entering he found that she had taken all the chinking from between the logs of the walls of the home and was burning them. She looked at him as he entered and said, “There you would go and leave me alone without any fire wood.” After this, he never left her without some logs to burn.

After she joined the Church, she became a devoted member and used her home for the missionaries, especially one young missionary from Arizona, Elder Charles L. Flake, of Snowflake, Arizona. Prejudice in the South at that time was very great against the Mormon people. Elder Flake was en route to meet the train to get the district president, [Joseph Loftis] Jolley. A mob waylaid him and emptied a bucket of tar over him and told him he was not worth breaking up a feather bed to feather him with. As he greeted President Jolley and shook hands with him, President Jolley patted him on his back and asked Brother Flake, “What’s this on your back, Elder Flake?” Elder Flake replied, “That’s dew.” President Jolley exclaimed, “Dew?” “Yes,” answered Elder Flake, “That’s how they do [it] in Water Valley.”[15]

When the time came for Elder Flake’s release, Susan and her family accompanied him to Snowflake, Arizona.[16] There she resided with him until a small log home for her was erected on a piece of land given her by Elder Flake’s father, William J. Flake. The home was soon erected, like the barn raising in the South, with willing hands.

Susan Hamilton Youngblood (center) with Ellen Webb (left) and Gabrilla Willis (803) as part of the Snowflake Relief Society, c. 1895. Photo courtesy of Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

Susan Hamilton Youngblood (center) with Ellen Webb (left) and Gabrilla Willis (803) as part of the Snowflake Relief Society, c. 1895. Photo courtesy of Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

Everything was strange and new in the West, and before she could adjust herself to changed conditions, her baby girl, a beautiful child, sickened and died.[17] The shock was almost too much for this poor widow, who had been bereft by the death of two companions and now two children, and it was a long time before she could bring herself to say, “The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away, blessed be the name of the Lord.”[18] But gifted as she was with courage, she went undauntedly to work to make a home for herself and the remaining children. This she did, and that home was a gathering place for the young and the old alike who were drawn to Aunt Susan, as she now became known to the neighborhood. Her stories of the Old South and of the war were listened to eagerly by all.

After she became an old lady, the writer of this sketch went to her to see if she could remember the tune to the Southern song, “The Bonny Blue Flag.” Of course she could remember the tune, but sickness had robbed her of her beautiful voice. However, she reached for her son’s violin and with trembling hands played the tune until the others learned it.[19]

My homespun dress is plain, I know

My hat palmetto, too,

But then it shows what Southern girls

For Southern rights, will do.

Aunt Susan’s beautiful black eyes flashed with the fire of youth, and she said, “Yes, and I’d pass through it all again for my beloved Southland.”

Loyal and true to principle all her life, independent and ambitious, she raised her family and taught them to be honorable, respectable citizens. Aunt Susan lived through the log cabin days of Snowflake; in fact, her home was one of them. No one ever heard her complain.

Death came to her on June 20, 1926, and with her going, her loss was felt by her wide circle of friends, who were her ardent admirers as well.

Ellis and Boone:

This sketch was submitted to the FWP on October 2, 1937. For PWA, the information about her conversion to the Church was added. But the FWP sketch has better punctuation and words which were accidentally omitted or left out in an attempt to condense the sketch; these have been reinserted. See Snowflake Pioneers in 1908, (708) for another photograph of Susan Youngblood.

A copy of Susan’s journal, which she began in 1893, was made by Norma B. Ricketts and is on file at the Stinson Museum in Snowflake. In the journal, Youngbood includes words to several songs and describes how the men and women of Snowflake helped after she arrived with Charles Flake. Here is some additional information from the journal:

About ten days after Gussie took sick I was taken with the same disease, and for six weeks, I did not know anybody or anything. It was while I was in this condition that I was called to part with my little treasure and when I was well enough to realize it all it seemed more than I could bear. I had left all for the gospel sake except for my four little children and I felt that I could not part with them. My trust was in my Heavenly Father, and He alone helped me to bear my many trials. She was buried by my kind friends. Brother Theodore Turley paid (three lines blanked out with ink). . . .

The Christmas following my sickness while I was still very poorly the brethren had a shooting match, and Brothers John Hunt, Ed M. East, A. M. Stratton, J. T. [T]alley, S. D. Rogers, and J. H. Willis Jr. presented me with the chickens that were killed. . . .

In September 1886 Leonard Jewell whose home was in the southern part of Arizona on the Gila River and who was intending to marry my oldest daughter, Olive, who was then 16 years old, came for her. They were going to be married in the temple in St. George, Utah. I made no thought of going with them, but the evening before they were to start Brother Flake came down and persuaded me that it would be best for myself and the other two children to go with them. We got ready on this short notice and with the financial aid of many friends were able to go and do the work for ourselves and our dead in the holy house of the Lord.[20]

Susan Youngblood then listed many of the ordinances performed.

One day, probably in the spring of 1895, the young men of Snowflake and their mothers came to surprise her. “The sisters got me off visiting one day and they came to my place with picknic, and the deacons came with plows and teams and wagons and brought with them shade trees and different kinds of fruit trees,” she wrote. The young men plowed the yard, planted the trees, and “made a water ditch and had the water all running nicely when I was sent for to come home at noon. My feelings I cannot describe. They all so halled me some wood and the decons made me a present of a good cow and a nice heffer calf which cost them 22 dollars.”[21]

Snowflake knew how to take care of their widows.

Notes

[1] Rhoda Condra McClelland Perkins, 523.

[2] “Brigham Young Jr.,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 1:121–26. This source only lists his first two marriages (1855 and 1857). It should be noted that he died in 1903. Ibid, 4:322.

[3] Wilmirth Margaret Greer East (1824−1902), sister of Thomas Lacy Greer.

[4] “Deaths from Smallpox,” Deseret News, March 14, 1883, but see Rhoda Condra McClelland Perkins, 525, for more details of this story.

[5] In 1881, Young brought his wife Catherine and spent a year in Arizona. Then in February 1883, he came with Heber J. Grant and others, touring many of the Arizona Mormon settlements. They suggested that the named Jonesville be changed to Lehi; the area was later incorporated into Mesa. This may have been when Young met Rhoda Perkins; however, they were not married until 1886. Brigham Young Jr. (1836−1903) married (1) Catherine C. Spencer in 1855 (eleven children); (2) Jane Carrington in 1857 (eight); (3) Rhoda Perkins (one); (4) Abigail Stevens in 1887 (seven); and (5) Helen Armstrong in 1890 in Mexico (one). Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 4:1650; “Brigham Young Jr.,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 1:121–26.

[6] Although PWA lists March 4 as the death date, Jessie Alice Young, a nurse, died March 5, 1920. AzDC, Jessie Alice Young; findagrave.com, #54994370.

[7] Davis, Fourth Wife, 2.

[8] Ibid., 6.

[9] Journal of Jesse N. Smith, 397. For a further discussion see Ellsworth, Mormon Odyssey, 191, 271.

[10] Allen, Embry, and Mehr, Hearts Turned to the Fathers, 42.

[11] Stapley, “Adoptive Sealing Ritual in Mormonism,” 116–17.

[12] See Psalm 127:3, 5. Verse 3 calls children “an heritage of the Lord.”

[13] PWA had a topographical error in this sentence, using the word pockets instead of pickets. Fortunately, in this case the FWP sketch had the correct word.

[14] The time in Arkansas must have been brief. The family was in Lafayette Co., Mississippi, in 1880 and again in Mississippi 1884−85 when the Youngblood family met Charles L. Flake. 1880 census, James Youngblood, Paris, Delay, and Dallas, Lafayette Co., Mississippi.

[15] Joseph Loftis Jolley (1846–1916) served from October 8, 1883, to November 18, 1885. This attack in Water Valley, Mississippi, occurred on May 17, 1884. Charles L. Flake diary, MSS SC 982, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, HBLL, BYU, vol. 4, May 17, 1884; typescript copy in possession of David F. Boone.

[16] The FWP sketch states that after the death of her husband, “Susan returned with her children to her old home in Mississippi. Here she remained until February 14, 1885, when with four of her children she bid good by to her dear old Southern home and came to Snow Flake, Arizona. One child [Benjamin] had died [at birth] and her eldest son remained in the South.” Two other relatives also joined the Church, nephews Jacob Isaiah Lindsey and John Thompson Cooper; both came to live in Arizona.

[17] Effa Augusta Youngblood, age nine years, died of complications from typhoid fever on October 15, 1885. She is buried in the Snowflake cemetery.

[18] Job 1:21.

[19] Claude Youngblood often played for dances, sometimes with Kenner Kartchner, son of Annella Hunt Kartchner, 339. Kartchner said that by age fifteen, he was “playing with Claude T. Youngblood, seven years my senior and considered the best dance fiddler in the area. . . . Hearing a tune once was ordinarily sufficient for me to memorize and play it.” By 1902, the Youngblood and Kartchner duo was playing for Texan, Mormon, and Hispanic dances throughout northeastern Arizona. Shumway, Frontier Fiddler, 37−38.

[20] “Sketch of Susan Sophrona Hamilton Youngblood, as written by her[self],” Stinson Museum, Snowflake Heritage Foundation, 2–3.

[21] Ibid., 4.