W

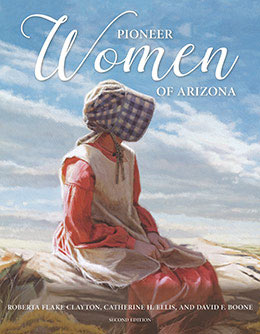

Rhoda Perkins Wakefield, Roberta Flake Clayton, Annie Woods Williams Westover, Artemesia Stratton Willis, Nancy Cedenia Bagley Willis, and Annie Woods Westover, "W," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 755-826.

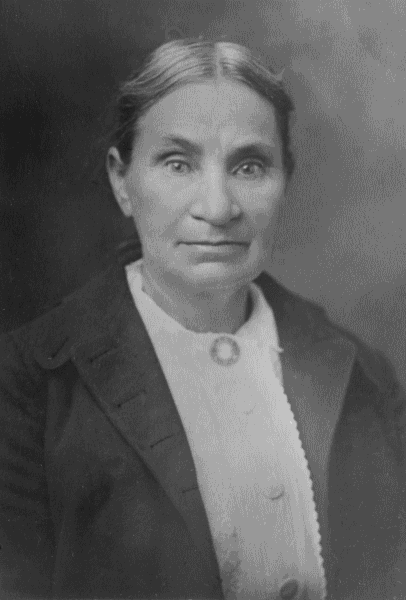

Aretha Morilla Bates Wakefield

Rhoda Perkins Wakefield

Maiden Name: Aretha Morilla Bates

Birth: February 6, 1855; Batesville, Tooele Co., Utah

Parents: Ormus Ephraim Bates and Morilla Spink

Marriage: Joseph Buck Wakefield; October 3, 1870

Children: Alpheretta (1872), Joseph Thomas (1873), Lillian Marinda (1876), Lansing Ira (1878), Erastus Snow (1881), Elizabeth Elliott (1884), Myrtle (1887), Julia (1891), Herma (1895), Celia (1897)

Death: November 25, 1928; Taylor, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Taylor, Navajo Co., Arizona

Born February 6, 1855, in a little town called Batesville, Tooele County, Utah, the daughter of Ormus E. and Morilla Spink Bates. Her father was a man of considerable means, owning mines and other property, but the children were taught to work and be industrious. Aretha learned to card the wool, spin and weave it into cloth, and make her own dresses, as well as knit stockings, shawls, and other articles of clothing.

She was married at age fifteen to Joseph B. Wakefield in the Endowment House, and she became the mother of ten children, seven of them growing to maturity. Her brother Orville had married her husband’s sister, Sarah Ellen Wakefield, and they were very closely associated ever after as their children also have been close, almost like brothers and sisters.[1]

In 1876, both families were called to leave northern Utah and colonize Arizona and work as missionaries among the Indians. The Wakefield and Bates families, who had been sent by Lot Smith to take charge of the milking and caring for one hundred forty-two cows, and the making of butter and cheese for the camp, settled at what was known as Mormon Dairy. Jesse O. Ballenger was in charge [of the closest settlement on the Little Colorado River] and it was called Ballenger’s Camp. Later it was named Brigham City in honor of President Brigham Young.

In September 1878, Erastus Snow found this community in a flourishing condition. There was a fort 200 feet square, with rock walls seven feet high. Inside were thirty-six dwelling houses each 15 by 13 feet; on the north side was the dining hall, eighty by twenty feet; adjoining was a kitchen 25 by 20 feet with an annexed bake house. Twelve other dwelling places were mentioned as well as a cellar and storehouse. Water was secured within the enclosure from two good wells. South of the fort were corrals and stock yards. Milk, butter, and cheese were supplied abundantly during summertime. But discouragement became general in 1881 and all were released from the mission.[2]

The summer of 1878, spent in the new settlement, had been a hard one for Aretha Wakefield, who was expecting her fourth child. She said she slept in a wagon bed with her clothes on until her husband managed to get a small house ready for her to get into, just before the arrival on November 8, 1878, of a big fine boy. It has been told in the family that he was called the “Graham Baby,” because of the healthy appearance which supposedly came from the diet of the community health-giving graham flour and bread.

He was given the name of Lansing Ira.[3] Lansing was the name of Aretha’s brother; Ira was for Ira Hatch, Indian missionary and companion and friend of his father.[4] Later Ira had a younger sister, Julie, who married into the Hatch family.

When Joseph Wakefield and family left Brigham City, they moved to “The Meadows,” some nine or ten miles north of St. Johns, Arizona. In 1873, Sol Barth had laid claim to 1200 acres of land. As a squatter, he had come in with a group of Mexican laborers and the town subsequently was named the Mexican name San Juan or later St. Johns, after the Mexican patron Saint. It was in celebration of this same saint on that June 1, 1882, that a commotion arose which was quite upsetting even in those days. There had been trouble over the theft of a colt belonging to the Greer family. Some of the Greer boys entered the town and some shots were fired, wounding a Greer boy and a Mexican. In a short lull between fighting, an old Mormon pioneer, Nathan Tenney, tried to take the part of peacemaker, walking to the house to induce the Greers to surrender to the sheriff, and was shot. The bullet, intended possibly for a Greer, struck the old man in the head and neck, killing him instantly. The sheriff had been in the act of arresting some of the men, but little punishment came out of it all for the offending parties.[5]

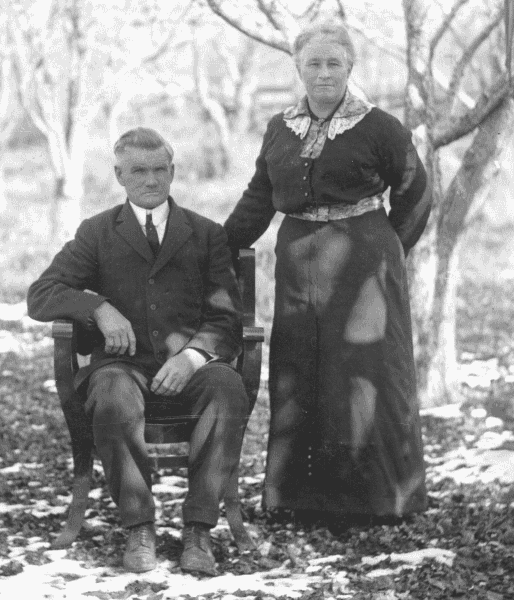

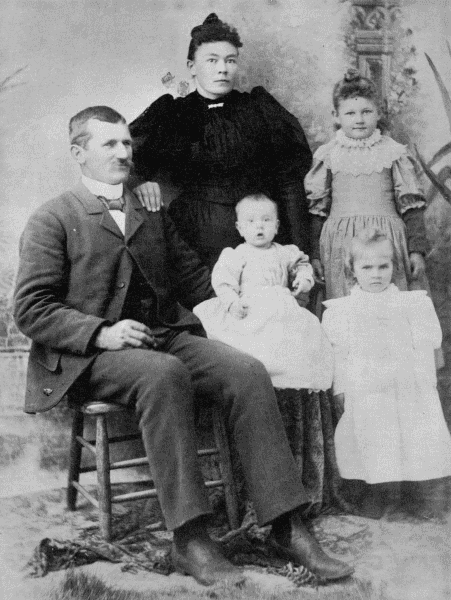

Joseph Buck and Aretha Morilla Bates Wakefield. Photo courtesy of JoAnn Hatch, Taylor Museum.

Joseph Buck and Aretha Morilla Bates Wakefield. Photo courtesy of JoAnn Hatch, Taylor Museum.

The Wakefield family moved to Navajo Springs [about 1893], where Joseph and sons found employment of a different type on the Santa Fe Railroad, first loading box cars with coal or [doing] some other odd job with which they could earn a livelihood.[6] Two more babies were born there, but both died soon after birth. The family enjoyed their life and association while living at Navajo. The boys went into the cattle business and became quite prosperous in that business.

In 1906, they bought a home in Taylor, Arizona. Most of the family married and raised their families there.

It was in 1906 that I [Rhoda Perkins Wakefield] became a member of the Wakefield family when I was married to their son, Lansing Ira. It was then [that] I became intimately acquainted with this fine woman, of whom I became very fond. She talked to me for hours on early day history of the Mormon pioneer. She was quite well versed in Church doctrine and loved to converse on its principles.

She was chosen as president of the Taylor Ward Relief Society and was very faithful in the performance of the same. One of her outstanding qualities was being on time. To be late to any appointment was almost a sin in her eyes. Mother Wakefield was a nurse and did much good among the sick.

In 1920, she went to California with her husband, where they lived for two or three years with some of their children. At a conference held in San Bernardino, President Joseph Robinson surprised her very much by calling her name from the audience to come to the stand and told her he had chosen her to be Relief Society President of the San Bernardino Ward, which position she held until she returned home to Arizona.

She passed away November 26, 1928, at her home in Taylor, where she is buried beside her husband, who had preceded her four months earlier, and for whom she never ceased to mourn, calling his name to the last.

Ellis and Boone:

As historian Dale F. Beecher recently wrote, “Mormons typically did not make their homes on farms or ranches away from town” when they began to colonize a new area.[7] Beecher used this 1882 Church directive to leaders in Logan, Utah, to support his statement:

In all cases in making new settlements the Saints should be advised to gather together in villages, as has been our custom from the time of our earliest settlement in these mountain valleys. . . . By this means the people can retain their ecclesiastical organizations, have regular meetings of the quorums of the Priesthood and establish and maintain day and Sunday schools, Improvement Associations and Relief Societies; they can also co-operate for the good of all in financial and secular matters, in making ditches, fencing fields, building bridges and other necessary improvements. Further than this they are a mutual protection and source of strength against horse and cattle thieves, land jumpers, etc., and against hostile Indians, should there be any, while their compact organizations give them many advantages of a social and civil character. . . .[8]

Some have used this or similar statements to argue that the Church discouraged ranching, but there were Latter-day Saint ranchers even in Utah, as evidenced by information about Prime T. Coleman, William Bailey Maxwell, the Sanders brothers, and Moses Simpson Emmett in this volume.[9] Beecher said that “pioneers located a good townsite, nearly always where a large stream issued from the mountains” and as the village grew, “satellite hamlets sprang up nearby.”[10] For settlements along the Little Colorado River and its tributaries in northeastern Arizona, however, there was never a large enough stream to allow for the town to grow substantially, and men had to look elsewhere for work, as did Joseph Wakefield about 1893.

The Wakefield family, after living at Brigham City, Mormon Dairy, The Meadows, and St. Johns, moved to Navajo Springs, about six miles east of Adamana on the Rio Puerco where they developed a ranch. Morilla’s husband and two of her sons, Tom and Erastus, worked for the Santa Fe Railroad. Her son Ira worked with some of the Hashknife cowboys, including “Frank Wallace, John Paulsell, George Hennesy, and Dick and Jones Grigsby, who became his life-long friends. They said of Ira that he was a good cowboy, dependable, level-headed, and slow to anger.”[11] Morilla’s daughters, especially Myrtle and Julia, became expert horsewomen.

When the family moved to Taylor in 1906, they bought land about ten miles northeast of town on Black Mesa, and during the ensuing years, they owned several ranches in this area. Joseph Wakefield worked for some years at a Pinedale sawmill with Joseph and Calvin Stratton. He also was the town constable and postmaster, and played the harmonica and called for square dances.[12] The Wakefield family married into and became part of the Taylor community.

Although much of the Wakefield family’s time was devoted to ranching, Joseph and Aretha were known as good Mormons. An unidentified grandchild wrote: “Though Joseph and Aretha never gained great fame nor prominence, they were great souls. . . . At the party honoring the couple on their 60th wedding anniversary Joseph’s sister, Ellen, had said: ‘Aretha was a very attractive young girl’. Grandpa jumped up, went over and put his arms around Grandma, and said: ‘I thought so too.’ Their granddaughters Grace and Irma sang, for the occasion, a song which was very appropriate:

If the Master knew

How I’d miss you

I wonder if He’d call me too?

’twould break my heart

If we should part,

For I’ve grown so fond of you.”[13]

Aretha Wakefield died only four months after her husband.

Charlotte Martha Maxwell Webb

Author Unknown

Maiden Name: Charlotte Martha Maxwell

Birth: February 15, 1862; Santaquin, Utah Co., Utah

Parents: William Bailey Maxwell[14] and Lucretia Charlotte Bracken

Marriage: Edward Milo Webb Jr.;[15] September 13, 1878

Children: Lucretia Annetta (1880), William Marcellus (1882), James Levi “Lee” (1884), Ruth Estelle (1889), Julia Isabelle (1891)

Death: May 5, 1943; Tohatchi, McKinley Co., New Mexico

Burial: Pinedale, Navajo Co., Arizona

On February 15, 1862, Charlotte Maxwell was born at Santaquin, Utah, the fourth child of Lucretia Bracken and William Bailey Maxwell. Her brothers, Lee and Jim, were twenty and eighteen years old. Her sister Ruth had died sixteen years before, at birth.

The Maxwells had adopted an Indian baby, Jeannie, about a year before Charlotte’s birth, who died when about seven years of age from whooping cough. William Maxwell, a wealthy cattleman for those days, also had two other families from his wives Jane Mathis and Maryetta Hamblin. Charlotte loved her half-brothers and sisters, especially her brother Will, [who was] about a year younger than herself.

The family moved to Spring Valley, Nevada, while Charlotte was still very young. The life there was ideal and lasted until she was fifteen. Since “Crishy” and Julia, her Aunt Jane’s daughters, were older than Charlotte, Mr. Maxwell decided to move to a Mormon community before they became of marriageable age. The maternal grandmother, Elisabeth Bracken, had died and her loved brother Jim had been killed by a cattle rustler before this, making the move away from Spring Valley more acceptable, since the place now held sad as well as happy memories.[16]

The Maxwells moved first to Panguitch, Utah, and later, in October 1877, to Orderville, Utah.

Charlotte went at once into school as assistant teacher to Willard Carroll; another young teacher was Milly Mulliner. First counselor to Bishop Thomas Chamberlain was Edward Milo Webb, a scholarly young man of thirty, black-haired, blue-eyed, and handsome. He was one of the few college men in the community, sensitive, beauty-loving, music-loving, and with a quiet humor to match Charlotte’s scintillating wit.

He had two wives, Ellen and Sarah, and his oldest child, Abbie, was only ten years younger than Charlotte.[17] This was the man Charlotte married on September 13, 1878, in the St. George Temple, and loved devotedly all her life.

Charlotte lived with her mother the first year of her marriage. By the spring she was eighteen, and her father had become restless and moved to Arizona. Lucretia and Charlotte parted tearfully, as Charlotte was expecting a baby.

Lucretia Annette, named for Charlotte’s mother and her dearest friend, Annette Coleman, was born April 18, 1880.[18] When Charlotte was twenty, her second child, William Marcellus, was born and died at the age of three weeks. She was still teaching up to a few weeks before James Lee’s birth on September 11, 1884.

Charlotte Maxwell Webb and her children, left to right: Lee, Estelle, and Louie, 1891. Photo courtesy of Thomas, Uncertain Sanctuary, 54.

Charlotte Maxwell Webb and her children, left to right: Lee, Estelle, and Louie, 1891. Photo courtesy of Thomas, Uncertain Sanctuary, 54.

The summer before Lee was a year old, Charlotte and her two children, her sister Julia and two children, and two young nephews, Bailey and Jim Maxwell, went to visit Charlotte’s parents at Bush Valley, New Mexico.[19] This entailed a long and dangerous journey by wagon over the Mogollon Mountains, at that time infested by Indians, outlaws, and wild animals. Lee was very sick most of the way.

When Lee was two, Charlotte accepted the position of teacher in the Bush Valley School. She and her two children “boarded ’round” a week with each family in the district. In this way, people paid their school assessment. That fall, her mother came from Oaxaca, Mexico, where the Maxwells were now pioneering in a Mormon colony, and spent the winter with her.

The next summer, the Webbs moved to Arizona. E. M. had been offered the career of starting the Church school system in the colonies there [Mexico], and at the time they thought their stay in Arizona would be only a brief stopover.[20] His brother Adelbert and family went with them. The women of the party each drove her own team and wagon and the men the freight wagons. Charlotte drove a team of white mares.

They settled in Woodruff and, as always, their time was full to overflowing with Church and temporal work. E. M. was made bishop, and Charlotte, or “Lottie” as she was now called, worked in all the auxiliary organizations, taught school in the winters, and worked in the Woodruff branch of the ACMI store summers while E. M. managed the Holbrook branch of this store. They were also active in civic and political affairs, and in the next few years, two more children were born to Lottie: Ruth Estelle and Julia Isabelle. The latter was born three years later at Snowflake where they lived.

E. M. Webb had been called on a mission to start a Church academy at Snowflake and urged as a personal favor to do so by Dr. Karl G. Maeser, who had befriended and sponsored him at the Utah University. He taught without salary, and Charlotte [taught] for a nominal sum, and her two youngest children were brought up in the Academy building.[21]

One activity at this time was a dramatic club of which E. M. was manager and Lottie was usually leading lady. Other close friends and actors were Osmer and Roberta Flake, Nettie and Loie Hunt, and Samuel F. Smith. Among Church positions held there and later in the mountain settlements and Mexico by Lottie were Relief Society president, president of the YWMIA, Primary, and various Church teaching positions as well as always teaching school.

In August of 1898, the Webbs realized their old dream of going to Mexico. Lottie went immediately into the schoolroom, but by this time, E. M. was suffering from a heart ailment and must be outdoors, and could do little more teaching. The family, as usual, was soon involved in church and community affairs. Lottie was made a stake aide to President Dora Pratt and filled numerous other positions.[22]

The family lived at first at Colonia Dublán, Chihuahua, and then at Colonia Garcia in the Sierra Madre Mountains. Later they moved to Colonia Morelos, Sonora, just twenty miles from Colonia Oaxaca, which Lottie’s parents had helped to found.

After a few years in Morelos, Lottie became desperately ill. She underwent a serious operation at El Paso, Texas, for a uterine tumor which weighed three pounds. The day before her operation, the Mexican colonies en masse fasted and prayed for her recovery and Apostle Woodruff, who came to see her at the [Arwell] Pierce home where she was staying with her husband, gave her a blessing, promising that her life span would be doubled and she would become a ministering angel to her people. She was forty years and six months old at the time. She recovered and lived to be eighty-one.[23] All the later years of her life were devoted to nursing, and she never refused a call, feeling she owed it to this promise to arise from a sick bed often to assist someone in need.

Fifty years after her operation at Hotel Dieu, El Paso, the daughter of her grandson, Edward M. Thomas, was born at this same hospital and named Linda.

After years of teaching in Mexico, Lottie had taken up nursing and was on a case at Douglas, Arizona, when the colonists were forced to flee from their Mexico homes to the United States by the Revolution. The Sonora colonists came out in 1912, and her two daughters joined her in Douglas. Louie had married and remained in Arizona and now Lee [Levi] was married to a Utah girl, Lillie Alispah.

After a few months in Douglas, Lottie and the girls joined the rest of the family at Tucson. From this time on, Lottie [made] her career as nurse full time. Later, the family moved back to northern Arizona, and she saw the dire need of a good county nurse, since many isolated ranch homes were fifty miles or more from the nearest doctor, and the only means of transportation was a wagon and team of horses.

For years she worked with Dr. Neal Heywood and became known to all in Navajo County and indeed, most of Arizona, as “Aunt Lottie.”[24] Her little house between Pinedale and Clay Springs was truly a “house by the side of the road” and she was a friend to man, woman, and child.[25]

She had lost her husband [in 1918], and her son Lee had been killed in an accident, leaving a wife and six young children.[26] Estelle and Belle were married also. When she was seventy-six, she went with Estelle and her husband, Jim Thomas, to Shiprock, New Mexico. She had been engaged in genealogical and temple work for years in wintertime and continued until her health broke. Even when she was too frail for the annual pilgrimage to the Arizona Temple, she became an ordained [set apart] missionary and with her daughter, worked among the Navajo Indians. She taught the women to knit and held weekly Relief Society meetings with them; the only one she missed was the day before she died.

On her eighty-first birthday, her Relief Society Indians surprised her with a party and gave her tribal souvenirs and wrote in her memory book. She died from a coronary thrombosis on the birthday of her youngest grandson, Donovan W. Brewer, May 5, 1943. She died at Tohatchi, New Mexico, at the home of her daughter, Estelle Thomas. Interment was in the cemetery at Pinedale, Arizona.

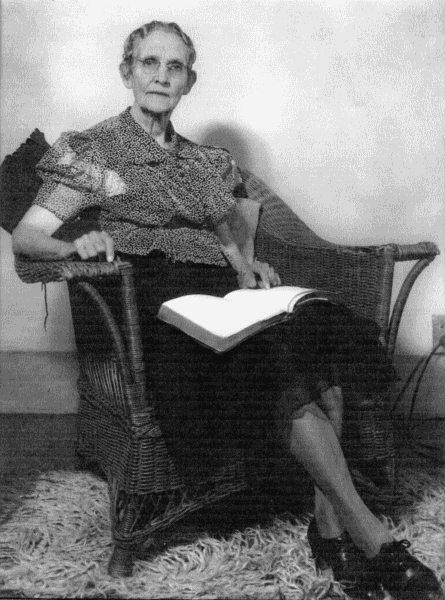

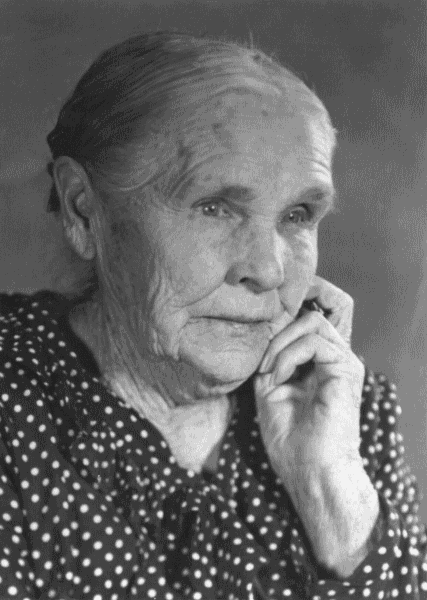

Charlotte Maxwell Webb. Photo courtesy of Jan Shumway Farr.

Charlotte Maxwell Webb. Photo courtesy of Jan Shumway Farr.

After she went to New Mexico, her home and everything in it was burned by juvenile delinquents. But now, on its site there stands a monument, erected by her grandsons, on which is a bronze plaque inscribed:

The flame of life burned brightly in her veins,

She loved the world, its creatures great and small;

And loving, shared their burdens and their pain

And in their service gladly gave her all.

Her radiant spirit warmed this lonely spot,

And maybe even heaven is more complete

For knowing those she loved have not forgot,

But keep her memory ever green and sweet.

Ellis and Boone:

A longer sketch for Charlotte was written as part of a book about Edward Milo Webb Jr., Charlotte Martha Maxwell, and their descendants.[27] But this story has been told in several places:

When the flu epidemic of 1918 struck the country, the little village of Pinedale was hard hit. Always more or less isolated in the winters, from bad roads and poor transportation, this year it was completely cut off from its neighbors for with the dreadful new disease there descended one of the worst snowstorms in years. The mailman, floundering through drifts on horseback, got through perhaps once a week or less often. Telephone lines were down and the scanty supplies of medicine were soon exhausted.

At the height of the epidemic, there were three able bodied persons in the town—E. M. Webb, seventy and with a bad heart; his wife, “Aunt Lottie,” 55; and his daughter May. Aunt Lottie . . . went from house to house, caring for the sick; many [were] very ill, and most of the family all down at once. May went with her, milking cows, helping with the wash . . . and feeding animals. E. M. Webb shoveled snow and made a network of paths all over town from one house to another. He chopped wood and carried it in, endlessly, when he should have been sleeping, walked to the outlying ranches of his children to see that all was still well with them.

Gradually, the disease subsided and people began to recover. . . . When at long last, the telephone lines were mended, and communication again established between towns, Dr. Sampson, of Holbrook, called Aunt Lottie up.[28]

“I am almost afraid to call you,” he apologized, “I thought of you often, but couldn’t get in touch. How many did you lose?”

“One,” said Aunt Lottie. “Mrs. Anderson, and she was already ill.”

“One? I lost dozens! What did you use? I tried everything!”

“We used what we had—faith and cup grease,” she answered, laughing.

“Faith and—what’s cup grease?” demanded the doctor.

“Eddie got it out of the cars and we made chest plasters of it,” said Aunt Lottie.

“Faith and cup grease!” said Dr. Sampson wonderingly. “The only two things I didn’t think of.”[29]

Finally, this letter from Charlotte Webb illustrates two other important parts of her later life—her emphasis on temple work and her concern with Native Americans.

254 E. 2nd St., Mesa, Ariz. Feb. 5th, 1929

President Anthony W. Ivins,

Dear Brother, I am advised by Pres’t Udall to write you concerning the adoption to my Father and Mother of two Indian children [sealing of these two children to Charlotte’s parents].

A [woman] of the Paron tribe died leaving a delicate girl baby of about three months old. Father and Mother took her and took care of her as if she were their own. She was blessed and given the name of Imogene Maxwell. The camp was moving as is normal after a death and the infant was to be abandoned. She died of whopping cough in her 7th year in Eagle Valley, Nevada. Father gave the Indians a horse in exchange for the child.

About two years after the death of the little girl, the same Indians of the Shoshone tribe came for a hunt and celebration to the part of Nevada where we lived. During the carousel of drinking, gambling, etc. a woman and two children changed ownership. The eldest child, a boy of about eight years, resented the change and refused to accompany the new father back to their home. The mother besought my father to take the little fellow and he gave her a horse, flour, and beef in exchange.

He lived with my mother until her death and then lived with other members of the family until his death in 1897. He was baptized and given the name of John Maxwell. He was always treated as one of the family. Mother loved him and he was devoted to her. If it will be right to all parties I should like to have these two children adopted to my parents.

I am working in the Temple this winter and can attend to it if I am allowed the privilege of having it done.

Yours very respectfully,

Charlotte Maxwell Webb

His reply was penned on the bottom of the letter: “I see no reason why these children may not be sealed to your parents. A. W. Ivins Febry 8th 1929.”[30]

Sarah Elizabeth Carling Webb

Author Unknown

Maiden Name: Sarah Elizabeth Carling

Birth: February 25, 1856; Ogden, Weber Co., Utah

Parents: Isaac Van Wagner Carling and Aseneth Elizabeth Browning[31]

Marriage: Edward Milo Webb Jr.; April 10, 1873

Children: Rachel Asenath (1875), Ether B. (1877), Owen Adelbert (1878), Catherine Alvira (1879), Isaac Clark (1881), Abraham Dewitt (1884), Jonathan Henry (1886), Thomas Howard (1888), Edson Burr (1889), Laura Martha (1891), Eliza May (1893), Sydney Jesse (1895)

Death: July 16, 1949; Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

In Ogden, Utah, on February 25, 1856, a daughter, their first child, was born to Isaac Van Wagner Carling and Aseneth Elizabeth Browning. They named her Sarah Elizabeth.

Isaac Van Wagner Carling was born in Klinesopur, Esopus, Ulster County, New York. His family heard the teachings of the LDS missionaries and believed. They joined the Church and moved to Ogden, Utah.[32]

Aseneth Elizabeth Browning was the daughter of another God-fearing man who joined the new faith.[33] She was born at Adams County, Illinois. Her family moved to the west with the Saints and made their home in Ogden. Here the young couple met and were married in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City.

When Sarah was two years old, they moved from Ogden to Fillmore. Here in the little pioneer school, she learned what she could during the short school season, which began after the crops were harvested in the fall and closed early in the spring so the children could help with the farm work.

Most of her education was in the practical arts learned from her beloved parents. Being the oldest child, it was necessary that she help her father with the work in the garden. She loved the out-of-doors and the smell of the loamy soil. Her teacher was a master gardener and he took pride in Sarah’s successes. She used the knowledge gained from him throughout her life, raising a garden wherever she went.

She learned to wash and card wool, spinning it into yarn from which she wove cloth. She took pride in fashioning clothes for herself and her sisters, and in knitting stockings.

Sarah grew up to be a quiet, reserved young lady with smiling brown eyes and soft curling hair. She was quick to see the funny side of little provoking happenings. Instead of becoming irritated at her mistakes, she usually could see a comical side of the situation, and her soft merry laugh would dispel the tenseness.

She was called to be a counselor in the first organization of the Young Women’s Retrenchment Society of the Fillmore Ward. There came into her life a school teacher, Edward Milo Webb. He was a brilliant and devoted young man who wanted very much to live the gospel to the letter. Sarah loved and married him, entering into the order of plural marriage as a second wife in 1873. She was willing to accept the responsibilities and sacrifice necessary to this calling.

There were two children born to them while Eddie was teaching school in Fillmore. Then they moved to Orderville, where her father also moved his family. Shortly after this move, Eddie took to himself a third wife, Charlotte Maxwell, in 1878.[34] They lived a busy, happy life in the community-order in which all property was pooled and each family received supplies as they needed. And each was assigned work according to his qualifications.

Eddie was given the job of clerk and bookkeeper. And Sarah spent most of her time as weaver. After ten years, the United Order was dissolved, and the Webbs moved to Arizona, where many Saints were gathering to help colonize that new country [about 1885].

Shortly after settling in Woodruff, Arizona, E. M. Webb was called to be the bishop of that new ward.[35] His faithful wives each shouldered her share of the responsibility of the work of caring for and training the children, supplying food, and making clothing.

Eddie was managing the co-op store, and while Aunt Lottie helped in this project, Sarah raised a wonderful garden with the help of the little boys. She also directed the care and tending of the family [cow], and some neighbors’ cows, which supplied the family with milk, butter, and cheese. She used her talent at the loom in weaving carpets for the family and many of her neighbors’ homes.

Having also learned from her resourceful father to mend shoes, she taught her eldest son, Owen, to repair the many pairs of Webb shoes.

Sarah was a very good cook. She was especially noted for her delicious salt-rising bread. She taught her neighbors and her daughters-in-law to make it and shared her rising [starter yeast] with them often.

She was quiet and unassuming, but graciously and efficiently filled whatever position in the organizations she was called to. She was counselor to three presidents of Relief Society in the Pinedale Ward in her later years. She loved the Lord and was always in attendance at her meetings. She suffered through her sorrows silently, losing four small children and her son, Burr, as a promising, talented young college student.

Faith in the power of prayer was cultivated in the heart of the members of this unusual triple family. One never-to-be-forgotten experience brought them all closer to the knowledge that a kind Heavenly Father is very near us and is willing to bless and help, in time of trouble and need, when called upon.

Sarah Elizabeth Carling Webb with her children, left to right: Clark, Henry, Burr, Owen, and Catherine, 1891; A. Miller, photographer. Photo courtesy of Flora Clark.

Sarah Elizabeth Carling Webb with her children, left to right: Clark, Henry, Burr, Owen, and Catherine, 1891; A. Miller, photographer. Photo courtesy of Flora Clark.

Here is the story as related by a son of E. M. Webb to the writer. “Pa’s leg had an infection in it, and it seemed that any treatment, which had been applied, was not effective. After a few days of suffering and worry, he saw that the limb had begun to turn black, and the pain was almost unbearable. He called for every member of his large family to come to his bedside. He explained to his children that he was very sick and that he might not get well. He asked them to sing his favorite hymn. Then he asked them to kneel around his bed and each took a turn offering a prayer in his behalf. Their prayers were heard and that night Pa rested, the pain eased, and the infection begun to clear up. The leg was well in a short time.”

Many happy years later, Sarah was living in Pinedale. Eddie was in Murray, Utah, with his daughters Cordelia, Hattie, and Irene, suffering from cancer of the stomach. He was proud to hear of the birth of his one hundredth grandchild. Shortly after he received this news, he passed away [on September 11, 1921].

Although Sarah was almost seventy, she decided to homestead a beautiful little valley out north and west of Pinedale. In 1922, she and Sydney and May moved out on the homestead. Here Sarah enjoyed pioneering again. There was no running water or electricity, and again she planted her seed in virgin soil. They never missed their church meetings, even though it may be storming or cold, and they had to go by team and wagon for three miles.

Her daughter, Martha, and husband O. C. Williams lived in Holbrook at this time.[36] On one of their visits to the homestead, Orlando was inspired to write this poem, in honor of her birthday.

Dear Little Old Lady

I found a little old lady sitting alone in the twilight glow,

Serene in her little homestead, wrapped in thought of long ago.

As I gazed through the open window upon the form so slender and bent,

I mused on the long life of service this dear kind soul had spent.

And I wished that I could fathom the depths of so great a soul,

And paint a life so charming to the world, on a mighty scroll,

Or write on the pages of history the deeds of kindness and love,

The trials hardships and sorrows endured through grace from above.

I marvel that though her fair form is bent and her steps grown slow,

Her smile has grown more sweet—her eyes with pure rapture glow;

And I wonder which of life’s changes of all her years of eighty plus four

Bring her now the sweetest memories as she dreams them o’er and o’er.

I wonder if the pain and sorrows are outweighed by gladsome joys,

Or if thought of kindly service to others, her pensive mood employs.

Methinks that the gentle spirit of this devoted soul

The path of all true greatness has pursued to its final goal.

Standing on the brink of tomorrow she can view with calm repose

The trials and sorrows of yesterday as her gaze eternal riches disclose.

And I know that her reward is sure as she nears that heavenly shore

To mingle again with loved ones in God’s presence forever more.

—O. C. Williams

Her uncomplaining goodness, her fairness and understanding in the difficult position of plural wife, combined with her energy and industry, have been a shining example to all who knew her. Sarah was always known for her patience, but even the best of us get annoyed at times, as this little anecdote will illustrate.

One morning, while Sarah was leading in family prayer, her two-year-old son began crying for his mother’s attention and would not be appeased by big sister or quieted [convinced] to close his mouth, but when he demanded her attention all the louder, she stopped praying, spanked him soundly enough to let him know that he was to obey, then proceeded with the prayer as if nothing had happened.

Sarah appreciated the gospel’s great divinely laid plan by which she could teach her children. She was humble and prayerful and taught her children to pray and have faith in our Heavenly Father’s kind and loving care. Their stories of guidance to find lost cows and many other more important and serious occasions of divine help in solving problems showed her that her children were following her teachings.

She was proud of each new grandchild and lived to welcome great-grandchildren. One by one her children moved their families to Mesa where they could give their children advantages of schools, etc. She passed away July 16, 1949, at her home in Mesa.

Ellis and Boone:

Not mentioned above is the family’s time in Mexico. Information from a history of Woodruff better describes their sojourns in northeastern Arizona, Mexico, and back to Arizona:

In 1876 Eddie [Webb] moved his family to Orderville, where, as secretary of the Order, his talents were used in making it a success. Records show that when the Order was discontinued [about 1885] the people were financially independent. So Edward and his brother, Francis Adelbert, were considered well-to-do. Outfitted with twelve good teams, wagons, breeding animals, and provisions to last their families for two years, they started for Mexico, where the church was beginning to colonize.

As they paused in Woodruff to take a three month rest before going on to the colonies, they received word through George Teasdale, an apostle, that an epidemic of smallpox was raging in the colonies.[37] Thus it happened that Edward Milo Webb had a change of heart and settled in Woodruff. Disposing of some of his cattle, he began to build for the future, not only of Woodruff, but of all of Northern Arizona. The first brick made in that part of the country was made under his supervision. He did bookkeeping for the A.C.M.I. in Holbrook and managed their store in Woodruff. His time and talents were given freely to the Church. While he was superintendent of the Sunday School a call came from Church authorities for him to establish an academy at Snowflake, less than thirty miles south of Woodruff.

The Snowflake Stake Academy was started on January 21, 1889, with Edward Milo Webb as its principal and teacher, and with a total student body of forty-four. High school subjects were taught, and this new school soon justified its existence.[38]

When the academy had been going for a year, Eddie was called back to Woodruff, this time to become bishop of Woodruff Ward, replacing James C. Owens. He was ordained as Woodruff’s second bishop on February 8, 1890.

After [nearly] two years as bishop, Edward’s services were again required as principal of the academy at Snowflake, where he stayed until the school had to close down for lack of funds. Then he took the trip which he had planned long ago, to the Mexican Colonies [about 1897]. Here he lived until the Mexican Revolution in 1912, when the saints were driven back into the United States. Eight years later he died in Salt Lake City, Utah.[39]

Julia Ellsworth West

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP Interview[40]

Maiden Name: Julia Ellsworth

Birth: December 15, 1869; West Weber, Weber Co., Utah

Parents: Edmund Lovell Ellsworth[41] and Mary Ann Bates

Marriage: Samuel Ezra West; April 21, 1886

Children: Emma (1887), Ezra Joseph (1889), Karl Bates (1891), Ida (1893), Sedenia (1896), Lavern (1898), Earl (1901), Mary Robinson (1904), Julia Gwendolyn (1907)

Death: August 10, 1958; Phoenix, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Lakeside, Navajo Co., Arizona

Julia Ellsworth West was the daughter of Edmund and Mary Ann Bates Ellsworth. She was born at West Weber, Weber County, Utah, on December 15, 1869. Being of a family of thirteen children, Julia early learned to be unselfish, a trait that characterized her life. From her English mother, who walked all the way from the Missouri River to Salt Lake City, she inherited a steadfastness of purpose that also remained with her.[42]

Julia Ellsworth West. Photo courtesy of Marion Hansen Collection.

Julia Ellsworth West. Photo courtesy of Marion Hansen Collection.

The Ellsworth family moved to Arizona in the fall of 1880, and settled at what is now known as the Ellsworth Ranch, near Show Low. This was purchased from Moses Cluff, and has been owned by some member of the Ellsworth family ever since. Here the family was raised, and happy recollections cling to the spot. Coming as did this family shortly before the coming of the railroad, when work was plentiful and the necessities of life a little easier to get, they were spared some of the hardships endured by the earlier pioneers. “As children we always had plenty to eat and wear. At Christmastime our stockings were always full and we enjoyed ourselves to the fullest.” Julia described these days thus and then went on, “My girlhood was spent on this ranch. The country was new and we had many thrilling experiences. The Apaches had a drunken fight on the hill right close to our house. They killed three Indian men, one a Chieftain, and wounded another Chief. Father took this wounded Indian to our home and cared for him until he was well.[43] Father was a great friend to the Indians; he would feed them and give them wagon loads of squash. He tried to teach them that all men were brothers. One day he called Natzen a rascal. This sly old fellow patted father on the back and said, ‘You my brother.’”

Julia recalled the only death of the Mormon pioneers in this part of the country was caused by Indians when they murdered Nathan Robinson, the uncle of the man she afterward married. He rode up to where they had killed a stolen beef, and they shot him and threw his body in Show Low Creek, covering all but one leg with stones. This foot stuck out of the water, and thus his body was discovered.[44]

The children of the family were given all the advantages of an education the country at that time afforded and, best of all, an unsatisfied thirst for knowledge, which urged them on to acquire more.

Frequently the young people of the surrounding towns attended conference at Snowflake, and many a friendship thus began ended in matrimony. This is Julia’s account of one:

We used to go to Snowflake to conference. These lasted three days, and were held every three months. The good people of Snowflake would always make us welcome, although we always tried to take our welcome with us. One time we took a large turkey and some butter. It was at one of these conferences I met my future husband. I was just sixteen, but we seemed to think we were in love, almost at first acquaintance, and it proved we were for we were married April 21, 1886 in the St. George Temple, Utah. We traveled the distance from Show Low, Arizona to St. George, in a light wagon traveling most of the way alone.[45] We had a small but very good team. At the Colorado River, we had to take our wagon apart to cross on the small boat. We had a very narrow escape of being drowned, and the ferrymen worked frantically to keep from going into a whirlpool where years later he was drowned.[46] Part of the way we had company. One time when we were alone, Ezra had to go quite a way to find the horses. He left his six-shooter in the seat for my protection. Not long after he was out of sight, a band of Indians on horseback surrounded the wagon, and poor little trembling sixteen-year-old Julia had to face all that war paint alone. They asked for something to eat, and I showed them the almost empty lunch box, and after a while they decided to leave, much to my relief, but being used to Indians, I was not frightened as I might otherwise have been.

We brought back small trees and other plants in the back of our wagon. We were fifteen days going and sixteen coming back. Ezra shot an antelope and some rabbits on the trip. I tried to make biscuits in the bake oven; the first time they did not raise a bit and I was just sick about it, for fear he would think he had a poor cook for a wife, but the next time they were better. We cached part of our grain on the way going so we would not have to haul it so far, and found it all safe when we came back. We had not intended getting married so young, but my folks were getting ready to move to Mesa, Arizona, and that was so far away in those days. Mother objected to our marriage because of our youth. Not only that but she did not have money to get me clothes, but after we pleaded our cause, she told him that if he wanted me just as I was, he could have me. She made me a white dress; the basque [bodice] was tight-fitting, and the skirt had three ruffles on it; this and one cheap cotton dress were my trousseau, no coat or hat. I wore a sunbonnet all the way there [i.e., to St. George] and back, and while I was there. Ezra bought me a coat on the way [back], when we got to Holbrook.

We returned to Snowflake, first, my husband’s home, where such a welcome awaited us. Mother West loved me as she did her own and was always as sweet and tender to me as a mother could be.[47] Father and Mother West gave us a lot just opposite their home to build on. We built one room of logs, and after a while we moved two small rooms of their old house as they had built them a fine two-story one. Mother West made me fifty yards of carpet from rags I had sewed. We had a lovely fireplace, and I used to whitewash the hearth, and the room looked like a little palace. I hooked rugs, and made crocheted tidies for the center table and chest my father had made for me. I made cushions for my homemade chairs, and Mother West would bring friends over to look at our house. She would give me cloth for a dress if I would make one for her, and when my girls came she would do the same for them if I would make dresses for her girls.

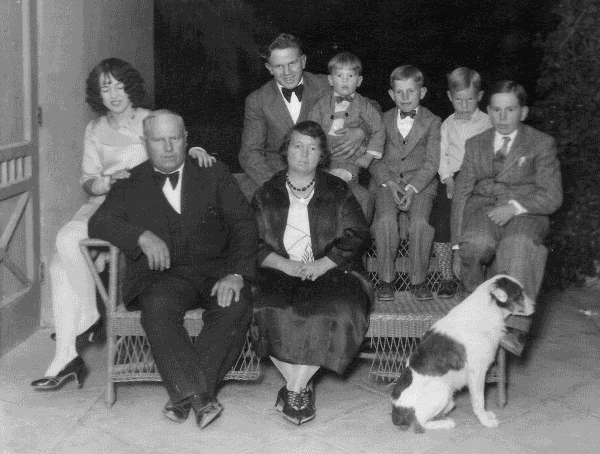

Julia Ellsworth West in 1938 with her children; front row, left to right: Earl R., Julia Gendolyn W. Johnson, Julia, Samuel Ezra (husband, insert), Emma W. Sponseller, Ezra Joseph; back: Lavern (insert), Sedenia "Dena" W. Sheehan, J. Alma (son of Ezra Joseph and Elma Stratton West), Mary W. Johnson, Karl Bates, and Ida W. Hansen. Photo courtesy of Marion Hansen Collection.

Julia Ellsworth West in 1938 with her children; front row, left to right: Earl R., Julia Gendolyn W. Johnson, Julia, Samuel Ezra (husband, insert), Emma W. Sponseller, Ezra Joseph; back: Lavern (insert), Sedenia "Dena" W. Sheehan, J. Alma (son of Ezra Joseph and Elma Stratton West), Mary W. Johnson, Karl Bates, and Ida W. Hansen. Photo courtesy of Marion Hansen Collection.

In this little home, five of Ezra’s and Julia’s children were born. The family moved to Woodland and was then away from both of their mothers. Frequently they came to Snowflake, but the two hundred miles of terrible road to Mesa prevented them making that trip often. Her mother came and visited her several times, and they would be very happy.

In Woodland (Lakeside) the family bought a good ranch and then some lots in town where they built themselves a spacious two-story house, with a bath on each floor. This home is almost elegantly furnished, with every comfort and convenience. It has served as a hotel since the West children have homes of their own. Ezra has been a successful businessman, having sheep, and with some of his sons engaged in the mercantile business. They had cabins for rent as well as the fine hotel rooms. Julia was an excellent cook, and guests who had been at their place once were always glad to go back again.

Nine children have blessed this union and are married and have homes and families of their own. They have had their share of sickness in rearing their children but have been unusually successful, as the sons are successful businessmen, and the daughters have all married well.

Julia was in a very serious accident many years ago and had one leg broken near the ankle joint. There was no doctor to be had, so they got a doctor’s son, who had assisted his father. He was very unsuccessful in this instance, however, and Julia suffered untold misery for a long while, unable to put any weight on that limb. The doctor said she might as well resign herself to a wheelchair, that she would not walk again. Her son Karl was in the mission field at the time of the accident. He wrote home that he was impressed that if she was taken to Salt Lake to a certain physician that she would be walking when he came home. She did go and was able to walk by the time he came home.

Besides raising her own family, she took a tiny babe and one of the other children of her son’s wife when she died, and in spite of every handicap, she raised him to manhood and was very happy with him. When her son married again, he took the little girl but let the boy remain with his grandparents, as they felt they could not give him up.

All of the children and grandchildren of this family are unusually talented, showing musical and elocutionary ability almost as soon as they can talk.

Julia was one of the sweet, gentle souls who radiated love and kindness and was beloved by her numerous family and wide circle of friends. She and her husband enjoyed the fruits of their labors and received some of the adoration to which they were entitled while they could still enjoy it. Her husband passed away August 15, 1938, at Lakeside. Julia was a widow for twenty years. She passed away in Phoenix on August 10, 1958. Her body was taken to Lakeside and placed by the side of her husband.

Ellis and Boone:

Information about two of Julia’s children should be included with this sketch. First, her son Lavern was known as a cowboy who lived in three centuries, born in 1898 and dying in 2000. He married, as his second wife, a White Mountain Apache woman named Clara. This meant that he could run his cattle on the reservation at Forestdale.[48]

As noted in this sketch, on November 24, 1918, Joseph’s wife, Elma Stratton West, died, leaving four children ranging in age from one-and-a-half to six years. Ezra and Julia moved to Mesa and lived next door to Joseph so they could help with the children. According to this sketch, when Ezra and Julia moved back to Show Low, they took the two youngest children with them. By 1930, Joseph had remarried, and the children (except for Alma) were living with their father in Laveen.[49] Alma simply became part of Julia’s family, and when a photograph of Julia and her children was taken shortly before her death, Alma was included.

Mary Jane Robinson West

Roberta Flake Clayton

Maiden Name: Mary Jane Robinson

Birth: October 24, 1848; Little North Canyon, Davis Co., Utah

Parents: Joseph Lee Robinson[50] and Susan McCord

Marriage: John Anderson West;[51] May 27, 1865

Children: Samuel Ezra (1866), Joseph Anderson (1867), William Heber (1869), Moroni Edward (1871), Amulec Isaac (1876), James Alma (1877), Oliver Robinson (1880), Mary (1883), Robert McCord (1885), Susan (1887), Wilford Cooper (1890)

Death: August 15, 1914; Salt Lake City, Salt Lake Co., Utah

Burial: City Cemetery, Salt Lake City, Salt Lake Co., Utah

Mary Jane was born just two weeks after her parents landed in Salt Lake Valley. ’Twas a cold blustering night. Snow was falling in Little North Canyon, October 24, 1848, just the eve of winter. Her bed? The wagon box which had brought them all the weary miles. They left Winter Quarters mid-June. Four months of travel, and now in all that cold was to be born a baby. The covered wagon bed was warmed only from the hot rocks carried from the campfire.[52]

When the Robinsons reached Mt. Pisgah and later Winter Quarters, they were very comfortable; their trip had been pleasant. However, during this time they had lost horses, oxen, and several cows, but their faith saw them through.

The year 1849 found [them in Utah with] their grain and meal greatly depleted. Men, women and children had to go on rations. They worked hard, clearing land and making ditches, and when spring came they had their hope renewed when their grain began to grow. The struggle with the crickets and the blessing of the seagulls came to them as it did to others. For two years they worked and were blessed with cattle and crops.

All too soon, word came from President Young that families were needed to leave their homes again and go to southern Utah. This time it was to Parowan, called Little Salt Lake, three hundred miles from where they were. Mary Jane’s mother had two sons from a former marriage, also colored John, who was part of Susan’s wedding dowry. Her father, James McCord, had asked at the time that she never part with colored John and had John make the same promise that he would never leave his “Missa Susan.”[53]

It was late fall before they started south. Land would have to be prepared for crops, and it would be a repetition of what they had just finished. Susan often wondered what her parents would have thought could they have seen her in all this poverty. She contrasted this to the night they heard the gospel in her father’s beautiful home. How servants had prepared the delicious meal. No wonder her father had had such strong premonitions [reservations] regarding her future.

Mary Jane’s childhood was made happy by sitting at her mother’s feet and hearing stories of the beautiful home she had had when she was a little girl. There had been servants to carry out her every wish, horses to ride, books to read. The culture and refinement of her mother’s life was made a part of her own. She grew to love books and was a natural-born actress and speaker. She took parts in many plays and became a favorite performer. She also studied dancing from a very interesting dance instructor, John A. West. Soon a romance blossomed, and Mary Jane and John West were married when she was not quite seventeen. John left soon thereafter to complete a mission in Hawaii, and Mary, much to her delight, was left comfortably fixed and enrolled in a school of her choice. When John returned from Hawaii, he sweetly insisted that she continue her schooling. This year school was out early in the spring, and not too soon for Mary Jane, because she gave birth to her first-born son, Samuel Ezra on May 25, 1866.

The very next year, October 5, their second son, Joseph, was born. He was named for his grandfather, Joseph Robinson and the Anderson for the great-grandmother West—Joseph Anderson West. On August 10, 1869, she presented John with his third son, William Heber. Another studious son, Edward Moroni, was born July 28, 1871. At this time the grandmothers stepped in and said they would take care of the children while Mary Jane took the baby and went up north to visit her relatives and enjoy a vacation. While she was there, she really enjoyed going to all the stores and buying lots of things that were unavailable in a small town. She was so elated when she arrived home after a long trip that she vowed she would never spend so much time away from her young family.

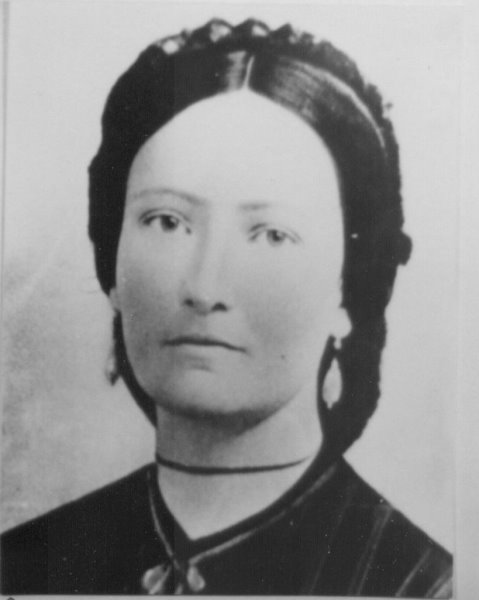

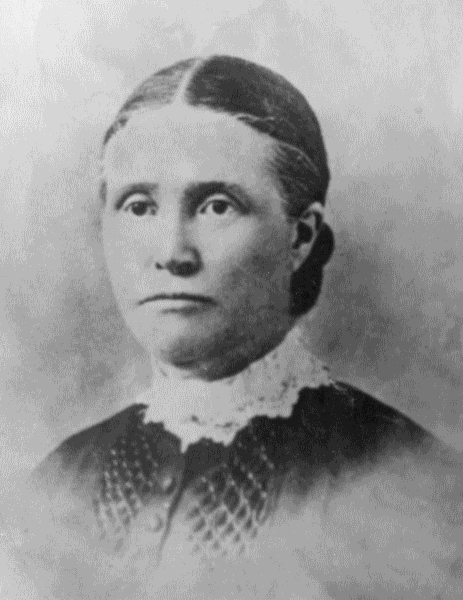

Mary Jane Robinson. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Mary Jane Robinson. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Since John’s mission to Hawaii had been cut short, he was now asked if he could return and finish his mission. At first they thought it impossible, but Mary Jane considered it very seriously and finally came up with the solution. She could teach school to support the family while he was gone. Preparations were made and John left for Salt Lake. While there he purchased an organ to send back to his little family. Mary Jane thought sure it was a mistake when she opened the large crate and saw the beautiful organ. A letter from John said he had arranged with Professor Durham to give the instructions she might need.[54] This was a blessing indeed to their home, and Mary Jane taught her boys to sing and be glad. They had music in their home and joy and peace in their hearts.

Mary Jane’s mother took care of the children while she taught school. The little pay that was given her spelled independence.

A very sad experience occurred to the West family when word came that William, John’s brother, was dead. It was difficult to send word to John. And while the tears were still wet upon their cheeks, word came that Father West was very ill. A great love had always existed between this trio, Father and his two sons, but now with William dead and Father West dead, only John remained, and he in far-away Hawaii. But time is a healer. John was now spending his third year in the mission field, and soon he would be coming home.

John could hardly believe he was looking at his little boys. They had grown so much while he was gone. It took a while to renew family life with his sons, who had become young men instead of children. Three years makes such a difference in the young. John showed his appreciation to his mother and Mary Jane’s mother by taking them on a trip to St. George to see the temple while it was being built.

Susan McCord Robinson was failing in health and seemed to know that her days were numbered. She was happy. Mary Jane had freshly painted her house and put up new curtains. On September 19, 1876, Susan passed peacefully away. To Mary Jane, this seemed the hardest trial; her mother had been her sole confidant, no secret ever between them. How could she walk alone—without her mother’s out-stretched arms? She was happy, however, that her mother had known five of her children. Her last baby had been born February 17, 1876, Amulec Isaac.

On April 6, 1877, the St. George Temple was to be dedicated. John planned to take his family there for the wonderful occasion [including] his mother, Mary Jane’s brother, Solomon, and his wife and children. While there, they had the sealings done for James and Elizabeth McCord, Robert Barnett with Hannah Herron, and others, which was a great comfort to Mary Jane. It was a wonderful trip.

In November of 1877, their sixth son, James Alma, was born. Two years later, scarlet fever swooped down upon the town. Grandmother West came quickly, but despite all they could do, John and Mary Jane were called upon to part with two of their sons, one four years old and the other almost two. Both were taken the same day, March 26, 1879, almost the same hour.[55]

Soon after this they received a call to go to Arizona. Mary Jane welcomed the call this time as it would take her away from the empty beds and the house where such great tragedy had come.

Quite a colony was named for this mission. Jesse N. Smith was asked to go and act as a stake president. He would take his wife, Emma, and two of her sisters were called, Lydia with her husband, C. E. Freeman and family, and Nancy and John Henry Rollins and family. Also the Decker family, the Hulet family, and the Rogers family. Most of them left early in the season. Grandmother West left with the first company because there were several women in that company who expected babies, and she was their doctor.

It was November when, with their worldly possessions packed in wagons, they left to wend their way to Arizona. Hardships came when cattle died; snow was encountered when they thought they would find sunshine in Arizona. Mary Jane became sick, and only a kind Providence brought her back to health.

When they reached Snowflake, they pitched their tent, and as soon as a fire was built, Mary Jane had the boys lay strips of carpet and set the organ down on it, and they all sang, “Home, Home, Sweet, Sweet home.”[56]

Snowflake became a joyous place to live. Mary Jane was asked by Bishop Hunt to be Relief Society president, and her work of service began.

On June 19, 1882, death came again and this time took John’s mother, Margaret Cooper West, who had lived so well and so abundantly.

John was a good and kind husband, always looking after the welfare of his family. He built a log room before summer set in, and before winter came, he had built another log room with a good fireplace.

Joseph, the second son, attended BYU, starting with the fall term of 1883. Ezra, the oldest son, married Julia Ellsworth April 21, 1886.[57] He did not have the opportunity of attending college. His father depended upon him so much to help with the family problems, and that, coupled with his humble willingness to be of service whenever and wherever he could, kept him at home. He loved to sing; in fact, all the family enjoyed music. Willie seemed a natural musician. Ezra and Julia lived very close to John and Mary Jane, and often Julia helped sew for the family.

On July 12, 1880, Mary Jane R. West was sustained as Relief Society president with Sister Lucy H. Flake as her first counselor. The second counselor changed many times, but Sister Flake remained with Mary Jane to the completion of her tenure of office. A great love seemed to come to these women from the start. They seemed to feel a kinship which even they could not quite understand.

Their days ahead in Relief Society were busy and rewarding. The summer did not pass before they were planning a new building to house the organization. With the help of their husbands and all the sisters, this building became a reality. It was much larger and nicer than they had dared imagine.

On November 2, 1880, little Oliver Robinson was born. This was one of the saddest things any of the family had known. The child was helpless from birth but lived to be five years old. The older children helped a great deal with this dear, patient child, especially Edward. Mary Jane said that he would receive a wonderful reward for his loving care of this little helpless one. Mary Jane had other children, two babies, younger than he, and she said she could not have survived without Eddie’s help.

In 1883, much to the surprise of all the town of Snowflake, Mary Jane gave birth to a little girl. She was all that they had dreamed of and hoped for, from her curls to her tiny pink toes. After seven boys, you can imagine how happy they were. This was Mary, who later married Don F. Riggs. Later years brought more children into this home: Robert McCord, on October 8, 1885, another beautiful daughter, Susan, on August 16, 1887, and Wilford, February 26, 1890.

Life here had its worries and perilous times. The Indians were hostile much of the time, and one midnight word came that Nathan Robinson, Mary Jane’s brother, had been killed by Indians.[58]

In 1892 many wonderful things happened. Dr. Karl G. Maeser, an eminent educator from Germany, who was now the well-known President of Brigham Young University, was sent to Arizona on educational matters. He came to start a Church academy in Snowflake. Mary Jane and her band of Relief Society sisters played a very important part in helping this movement. The sisters agreed to save every egg that was laid on Sunday for contribution to the buildings that would be needed. The Relief Society donated their building to the school so it could be opened in September. John A. took the Sunday eggs to Fort Apache and sold them, and it wasn’t long until they were building them a new building. In fact, it was a larger building; it had two rooms this time and built of bricks instead of logs.[59]

About this time, a distinguished lady from the East visited Snowflake. She was Mrs. Carrie Chapman Catt of Woman’s Suffrage fame. Women of this day who treat the privilege of voting very lightly, passing it up unnoticed at times, can little realize how hard so many people worked that women might be allowed to be heard in public or to cast their vote. Mrs. Catt visited a few women and then very bluntly asked if she [Mary Jane Robinson West] would accept the county chairmanship of the Woman’s Suffrage Movement. Mary Jane considered it carefully, and after getting the consent of her husband and the stake president, she was appointed.[60]

Each month Mary Jane wrote an article for a little paper, The Pearl, and in her choice papers are many of her contributions. One was entitled, “Making the Mind Beautiful,” another, “The Greatest Teacher, Except One,” another “Marriage, What it Means.”

Mary Jane was a wonderful mother and managed her home with kindness and love. For eight and one half years, her home was made beautiful and happy by the presence of her beloved brother, Solomon, and his motherless children. His Teena had died in 1890, and the family came to Arizona in 1891. Lots of changes had taken place since we told you of first the tent, then the dirt room, and next the large log room with the fireplace; then came the Big House, as it was called. Five bedrooms upstairs, two large living rooms, kitchen, pantry and basement. So when these children came, it looked like they had been expected.[61]

In 1899 John and Mary left for an extended visit in Salt Lake. She missed her work with the dear Relief Society sisters, especially her life-long friend, Lucy Flake, who passed to the great beyond while Mary Jane was in Utah. The Wests returned home in 1902. In 1905 she was sustained as the Snowflake Stake Relief Society president. She had spent fourteen years as president of the ward Relief Society, ten years as counselor, and seven as stake president before they made a final move back to Utah. All their children except Ezra and his wife, Julia, and family would be close to them in Utah. Mary Jane loved Arizona, with its wind and its storms and its beautiful, peaceful summers.

Her twilight years were spent in Salt Lake, where often on a warm evening she and John A. would sit on their long porch overlooking Salt Lake Valley, watching the twinkling lights as they came from Fort Douglas down into the city, and she often wondered if Heaven could be more delightful.

Ellis and Boone:

RFC submitted a sketch for Mary Jane Robinson West (written by daughter, Mary West Riggs) to the FWP in the 1930s.[62] The sketches for the FWP and PWA are entirely different, although much of the information is the same. It seems appropriate to include several paragraphs from the FWP sketch that describe Relief Society activities in Snowflake:

Mary Jane Robinson West with baby Mary, c. 1883. Photo courtesy of Smith Memorial Home, Snowflake.

Mary Jane Robinson West with baby Mary, c. 1883. Photo courtesy of Smith Memorial Home, Snowflake.

There was a dear old blind man who used to enjoy going to her home, because she was never too busy to sit and read to him or converse with him, on the things that were nearest their hearts.[63] One day he said to her, “Dear friend, you are so good to all of us. I can feel the heavy load you are carrying, but I say to you the day will soon come when you will have more help than you need.” This prophecy was fulfilled as her daughters and nieces grew older. . . .

A beautiful custom prevailed in the town at that time. If there were any sick or homebound, the ladies took turns sending the afflicted one a good hot dinner each day. This was under the direction of the President of the Relief Society and her councilors. If there were a fire, or any other calamity, they were the first to aid, as many of the people not only in Snow Flake, but Holbrook and other surrounding towns can testify.

Her home and church duties were not the only responsibilities Mary Jane carried.

When the women were working so hard for suffrage and the ballot, she entertained many of the visiting ladies, and was made County President of the Suffrage Clubs. She was also a member of the Board of Education. All of these positions necessitated her visiting all of the towns in the County, at frequent intervals. There were no automobiles in those days, so they purchased a “White tot” carriage and borrowed trusty teams and started out. It took two days travel to reach some of the outlying places, but they were always welcome wherever they went, she and her councilors, and the work was so dear to their hearts that they never considered the performance of a duty a hardship.

The first flag that ever floated over the town was made by the sisters of the Relief Society, and was sixteen feet in length. From a tall Liberty pole in the Public Square, it proudly waved on all festive occasions such as the Fourth and Twenty-fourth of July.[64]

May Hunt Larson does not record a visit of Carrie Chapman Catt, but she does mention a visit by Laura Johns in 1896.[65] Two entries from Larson’s journal describe this visit. April 18: “A noted lady lecturer on Woman’s Suffrage, Mrs. Laura M. Johns of Kansas visited us. Father [Bishop John Hunt] met her at Holbrook and brought her up.” April 20: “Monday Mrs. Johns held both another afternoon meeting and evening meeting and organized an association. Making Henrietta Hall, president; Mary J. West, vice president; Nettie Hunt, correspondence secretary; Bashie Smith, records secretary; James M. Flake, treasurer; and May Larson, auditor. The meetings [are] to be held semi-monthly. The lady seemed to be pleased with our town and people, and we were pleased with her and her interest in us.” May Larson also wrote about attending “the Taylor Woman Suffrage Association meeting with Sisters Hall, West and Driggs” on July 29, 1896.[66]

Before coming to Snowflake, Laura Johns had visited the Gila Valley. Joseph Fish wrote, “On March 10th [1896] Mrs. Johns who was from Kansas gave a lecture in Layton on the subject of Women’s Rights. She did very well, but appeared to have but one speech which had been carefully prepared. After the close of the meeting a club was formed for the promotion of Women’s Rights. I with several others joined this organization as I always had been in favor of the women having the right to vote.”[67] Fish then mentioned that when he was in the Arizona Legislature, he had supported the right of women to vote. On February 12, 1895, the House passed a suffrage bill by a vote of 16 to 7, but the bill was later killed in the Territorial Council.[68]

In 1899, the Phoenix newspaper mentioned Mrs. Catt attending a state convention on November 21 and 22, but there is no documentation of her coming to northern Arizona.[69] During this period, woman’s suffrage moved forward state by state, with western states leading the way. Sometimes women gained the right to vote in municipal elections before state elections. In Arizona, the territorial legislature regularly debated a woman’s right to vote, but it was not until November 1912, the first election after becoming a state, that Arizona men voted for woman’s suffrage. Even so, this was eight years before passage of the Nineteenth Amendment.[70]

Annie Woods Williams Westover

Autobiography, FWP

Maiden Name: Annie Woods

Birth: March 23, 1868; Porterville, Morgan Co., Utah

Parents: James Tickner Woods and Annie Chandler[71]

Marriage 1: Pleasant Samuel Williams; May 19, 1887 (div)

Children: none

Marriage 2: Arthur Leo Westover; May 30, 1938

Death: January 11, 1966; probably Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

I first opened my eyes to the light of day in the little town of Porterville, Morgan County, Utah, March 23, 1868.[72]

I came welcomed into life by both fond parents to a home where abject poverty reigned. They were emigrants recently from England to this dreary, forbidding little spot, such as all Utah was at that early day, arriving travel-worn and destitute of the comforts of life.[73]

My mother, having come from an old English mansion, with its retinue of servants and all the luxuries that went with an Old Country Seat, was about as frail as a lily grown in a hot house, and as helpless as a birdling dropped out of its nest before having grown its feathers.[74] She had also been recently bereft of both parents, so that her orphanage, coupled with poor health, did not contribute anything towards the normal body which I should inherit, but did not.[75]

Annie Woods Williams Westover. Photo courtesy of Anonymous.

Annie Woods Williams Westover. Photo courtesy of Anonymous.

I did not thrive but had to make a hard fight for life; grew up under malnutrition and so fell an easy prey to all diseases common to infants and small children, until I believe I ran the gamut—mumps, measles, chicken pox, scarletina, and the rest.

When I was seven years old, my father, James T. Woods, was called to Arizona to help establish the United Order on the Little Colorado River. We bade goodbye to home and friends and sallied forth in the midst of a heavy snowstorm February 7, 1876.

The journey of three months and ten days was fraught with perils and hardships similar to those who made the trip across the plains to Utah. When we crossed over the Buckskin Mountains, the road had to be worked with picks and shovels through nine feet of snow in places. Many of our party suffered from frost-bitten hands, feet, and ears. After sitting in a cramped position all day, we had to line up for the night in a sitting posture crosswise of the wagon box like sardines in a can, too cold to remove wraps or shoes, our breath forming into frost around our faces. One wagon had to accommodate one family together with all its worldly belongings, such as food supplies, farming implements, and seeds.

As canned milk, vegetables, and all canned goods were then unknown, our bill-of-fare consisted of dry beans, bacon, flour, rice, and dried fruit; campfire bread was baked over any kind of fire we could get; the bread burned if the wind was heavy, and doughy if the wood supply was scarce.

Water supply: any kind we could find, muddy, brackish, or even stagnant. After we struck the Little Colorado River, our only supply was in holes along the river bottom, and in places so stagnant that the fish were dead and floating in the green slime. But it was water and had to be used by man as well as beast. This was boiled over a sagebrush fire to sterilize it, then strained into barrels, and used very sparingly.

Before we reached our destination, while we plodded our weary way across those wastes of glistening sand (on foot, to lighten the load of our jaded teams), the mercury registered 114 degrees and our tongues were swollen from thirst.[76] Oh, for a drink of pure, cold water from our wells in Utah. We arrived at our destination the fore-part of May, making the journey in about three months and ten days.

The first job after establishing camp was to begin clearing land and prepare for planting so the food-stuffs could be growing. So we lived in wagon boxes and tents that season.

In the fall, an adobe fort was built, and each family was assigned one room in which to live. All ate at one big table, so [everyone] had a chance to sample a variety of cooking, as each group of women took their turn in the kitchen.

As every ounce of foodstuff (as well as other supplies) had to be hauled from Utah by ox teams across the Arizona desert, nothing could be wasted when once it arrived, even though a can of coal oil happened to spring a leak on the road and come in contact with a sack of sugar or flour or dried fruit. Every morsel had to be eaten.

The first Christmas, I remember my stocking was not empty in the morning, for it had in it a raw carrot and a small piece of molasses candy, and I was quite content and happy.[77]

My schooling began here, my mother being the teacher. My brother, Andrew Woods, received the first diploma and drew the first salary from the county treasury for school teaching. He taught in the territory and state for many years.

Annie Woods with husband Pleasant Williams. Photo courtesy of Anonymous.

Annie Woods with husband Pleasant Williams. Photo courtesy of Anonymous.

Soon after our arrival, whooping cough came along and found all the children in camp waiting for it. Their poor little, skinny bodies were so emaciated that they had very little resistance and so fell an easy prey to this dread disease, which took a heavy toll, my baby sister being among the victims.[78] I coughed for two years, during which time I did not grow at all; if possible, I became thinner and weaker. After a time, Apostle Erastus Snow came down from headquarters and paid the camps a visit, investigating conditions. Finding them unsatisfactory, he released from the Order all who desired to leave.[79] My father had taken a good outfit with him and put in it all his worldly possessions, which were now all gone, and had nothing with which to move away, so had to stay in the country.

About this time, some settlers were taking up land at and around Show Low.[80] Father went there and planted a crop, but before harvest the Indians caused us trouble, and the authorities advised all ranchers to move to larger settlements for safety. We went from there to Taylor, Arizona, and built a little home, fenced a small piece of ground, and again planted.[81] We remained in Taylor for a couple of years, when a better opening seemed to present itself in Woodruff and we moved again.[82]

The Woodruff Dam washing out for seven successive times is a matter of common history and needs no further comment. Here again Father made another attempt to build us a home; [he] had the framework up and a couple of rooms under roof when he was called to Great Britain on a mission (1885−87).

During his absence, Mother and I were thrown entirely on our own responsibility, as well as furnishing money for Father during his absence. Mother kept the little country post office and I was her assistant. During my father’s absence, my only living sister (foster child) came and visited us. Soon after her arrival, she fell ill with typhoid fever, and later my mother became infected and was also very ill.[83]

There was not a doctor in our part of the country, not even a drug store. I was young and inexperienced but did my best (which was poor indeed) and watched them fade and die just eight days apart, leaving me thus alone in the empty, unfinished house to carry on, as I was assistant p[ost] m[istress] and must look after my official duties until another could be appointed from Washington D.C. to take my place. In these days, Washington was a long way off, and weeks of time was needed to make the change.

As mail arrived in the night, every night I had to be there to attend to it. I slept upstairs alone in the bed which my mother so recently died, came down stairs by the light of a coal oil lamp, and into the empty post office. Telephones were not yet in use, and no neighbor living within call. Everybody seemed so far away and everything so silent.

When Father returned, he found Mother and my sister gone and me wasted almost to a skeleton. The following spring, I married and moved out of the state and came back years later and built a home in Mesa, Arizona. I have taught school for five years, was a member of the Home Dramatic club for years, and have always taken part in all of the activities, religious and social, in every community in which I have resided.

Ellis and Boone: