U

Pearl Udall Nelson and Paulin U. Smith, "U," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 737-748.

Eliza Luella Stewart Udall

Pearl Udall Nelson, FWP[1]

Maiden Name: Eliza Luella “Ella” Stewart

Birth: May 21, 1855; Salt Lake City, Salt Lake Co., Utah

Parents: Levi Stewart and Margery Wilkerson

Marriage: David King Udall;[2] February 1, 1875

Children: David Stewart (1878), Pearl (1880), Erma (1882), Mary (1884), Luella (1886), David King (1888), Levi Stewart (1891), Paul Drawbridge (1894), Rebecca May (1897)

Death: May 28, 1937; St. Johns, Apache Co., Arizona

Burial: St. Johns, Apache Co., Arizona

To have written the last chapter of Proverbs beginning with the tenth verse, the wise Solomon must have been divinely inspired, and also he must have known a woman like our mother.

It seems not unfitting to slightly change Solomon’s description of the ideal woman—wife, mother, friend—and apply his words to one who lived as Mother lived her eighty-two years. Mother led a rich and busy life, but it is not so much what she did as what she WAS that stands out in our memory of her as clean-cut as a beautiful cameo, her sweetness, her culture, and spiritual refinement impressed alike close friends and passing strangers.

“Who can find a virtuous woman?” says Solomon, “for her price is far above rubies” [Proverbs 31:10]. Father found such a woman when in his youth he married Luella Stewart. She was only a slip of a girl then, with charming modesty and poise. In her maturity, she developed a wealth of human understanding, which made it possible for her to be patient and forgiving in her dealings with people. Throughout her years, she opened her mouth with wisdom, and in her tongue was the law of kindness. Her price was above rubies because she practiced what she believed and taught, and she taught more by example than words. When she said to us, as she sometimes did, “My children, remember that two wrongs never make a right,” and “It is better to suffer a wrong than to do one,” the lessons usually went home because in her everyday life she conformed to these ideals.

The heart of her husband did safely trust in her, and she did him good and not evil all the days of her life [31:11–12]. Her love and loyalty and her faith in her husband sustained him, and he was known in the gates when he sat among the elders in the land [31:23].

Mother looked well to the ways of her household; she did not eat the bread of idleness nor did she permit her children to do so [31:27]. She loved the morning hours and often arose “when it was yet night” that she might give meat to her household [31:15] and send her loved ones forth fortified for the day with a morning prayer and a wholesome breakfast. Like the “merchants’ ships” [31:14], her mind traveled far and near, for she sought knowledge along many lines and especially pertaining to the art and science of her housewifery. She delighted in preparing and serving attractive and health-giving foods. She said to us often that through keeping the Word of Wisdom and being consistent in her eating she had built her frail body into a strong and healthy one. “Yes, she girded her loins with strength and strengthened her arms” [31:17]. From her own experience she found her “merchandise” was good [31:18], and she shared it with her many friends, for the Udall home was always a “house by the side of the road.”[3] Motherless girls and boys turned to her as naturally as flowers turn to sunshine, and she mothered many of them to whom she was always “Aunt Ella.”

Mother’s candle did not go out at night [31:18]. She read or stitched by the light of her candle, and it burned in the window to beckon us home. She sought wool and cloth and worked willingly with her hands [31:13]. She enjoyed so much the beauty of “fine linen” [31:24] that she considered it worth her time and effort to procure and preserve it. In pioneer days she was skilled in carding wool [31:19] and making it into balls to be used in her quilts. Her rag carpets were as beautiful tapestries on the floor of her cottage. She was not afraid of the snow for her household, for all her household was clothed, though seldom in “scarlet” or “silk” or “purple” [31:21–22], for our mother was a Mormon pioneer and of necessity turned simple materials into usefulness and beauty. Always “strength and honour” were the warp and woof of her clothing [31:25], and she tried to teach us to be happy in her way of life. Truly, her children have risen up to call her blessed and her husband to praise her [31:28].

Eliza Luella Stewart Udall; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

Eliza Luella Stewart Udall; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

She stretched forth her hand to the poor, yea she stretched forth her hand to the needy [31:20]. She ministered not alone to the poor in this world’s goods but also to the needy in the things of the spirit. For thirty-five years our mother directed the Relief Society work in the Arizona towns of St. Johns, Concho, Eagar, Nutrioso, and Alpine, and in Luna, Ramah, and Bluewater in New Mexico. It is often conceded that in no other organization under the sun is charity in its fullness practiced as it is in the Mormon Relief Societies. This could not be save [i.e., except] for the untiring efforts of women who served for the love of serving. Through her Relief Society work Mother helped in setting high standards intellectually, spiritually, morally, and physically in the homes of the people. She and her co-workers took an active part in advancing the cause of Woman’s Suffrage and were alert to the need of fostering in women a keener sense of civic responsibility. Her friends and associates will tell you that she was a wise director and exemplar in Relief Society work, and that in reality she stretched forth her hands to the needy, often going as an angel of mercy in the hours of the night to succor the sick, care for the dead, and to comfort those that mourned. Mother looked upon the Relief Society as a great “field” to be purchased by the women of her church with love and unselfish service and to be planted as a “vineyard” [31:16].

In her later years, Mother was called to preside over the woman’s department in the Latter-day Saint temple in Mesa, Arizona. For seven years she served in that sacred place. So often in the temple, she sat at the foot of a beautiful stairway that her sisters affectionately referred to her as the “angel by the stairs.” Attired in spotless white, with a smile on her lips and a light in her clear blue eyes, she encouraged all who came her way to fear the Lord and love him.

Mother sits no longer by the stairs in the temple, for she has ascended the steps that lead to the throne of the Master. We are thankful for her abundant life and for the assurance we have that in our Father’s kingdom she will be given the fruit of her own hands and that her own work will praise her in the gates [31:31].

DATA:

Eliza Luella Stewart Udall was born in Salt Lake City, Utah, May 21, 1855, a little less than eight years after the first pioneers arrived there. She was the daughter of Levi and Margery Wilkerson Stewart. In her youth she attended private schools in Salt Lake, among her tutors were Sarah E. Carmichael, one of Utah’s gifted poets;[4] T. B. Lewis, a veteran teacher who was a great inspiration in her life; and a Mrs. Brown, who gave the Stewart girls formal instruction in the art of sewing.[5] In her early girlhood she helped her mother in making tallow candles and homemade soap, and she learned in many ways to meet the needs of a pioneer home.

In the Spring of 1870, when she was fifteen years old, her father was called to Kanab and to take his large family. The call came from that great Mormon colonizer, Brigham Young. Her father was to be the first bishop of that town. The colony was small, and for a while the people lived within a fort built as a protection against marauding Indians. In December of that year her mother and five brothers perished in a terrible fire that broke out in the fort, and her own life was providentially preserved at that time.[6]

Before the Stewart family left Salt Lake City, President Young requested that one of the girls stay at Toquerville en route to Kanab to study telegraphy [words left out] line out of Kanab. Ella was left in Toquerville with Sarah Ann Spilsbury as her teacher.[7] In great homesickness, she studied almost day and night for six weeks and was then qualified to go into the new telegraph office when it should be opened. Immediately she joined her family in their new abiding place, not yet could it be called a home. In December 1871, she was stationed for a time in the telegraph office at Pipe Springs, Arizona, located a few miles from Kanab. Thus she became one of the first telegraph operators in Arizona. During the time of Major Powell’s expeditions to the Grand Canyon, she telegraphed his reports from the Kanab office to the Government in Washington, D.C.

On February 1, 1875, in Salt Lake City, she was married to David K. Udall of Nephi, Utah. Six weeks after their marriage, he left for England to fulfill a mission for his church, and she returned to Kanab where she resumed her work in the telegraph office then located in the Co-op Store. She also kept the store books and for two years assisted as part-time teacher in the town school held in a building very near the telegraph office. Her salary for all this work was paid, not in cash, but in labor which she turned into the remodeling of a small rock house, which her husband’s father had sold to them. This first home was old before they even moved into it, for soon after her husband came from Europe, the Church authorities called him to return to Nephi and be the leader of the newly organized Young Men’s Mutual Improvement Association in that town. Soon after reaching Nephi, they took up a homestead near town and joined relatives in the construction of a reservoir to store water to be used for irrigating the land. They built a new home; this one of logs brought in from one of Mount Nebo’s rugged canyons. In spite of their high hopes, their homesteading proved a great disappointment, by reason of their dam being torn out one night by jealous and uninformed neighbors. The year’s crop was burned up, and the little home was left high and dry and had to be abandoned. Soon after this occurrence, the Udalls moved to Kanab where they lived for two years. During that time they secured holdings in the now famous Dumott Park on the north rim of the Grand Canyon.

David and Ella Udall's home in St. Johns, October 1937; Max R. Hunt, photographer. Photo courtesy of Elis Collection.

David and Ella Udall's home in St. Johns, October 1937; Max R. Hunt, photographer. Photo courtesy of Elis Collection.

In October 1880, the still youthful couple with an infant daughter came to St. Johns, Arizona, in response to another call from the authorities in the Mormon Church. This little Mormon colony was only one year old when they arrived, and David K. Udall was made the first bishop. For some years, the family lived in a Mexican house with a dirt roof. The building of the community of St. Johns was a long struggle with floods and droughts and alkaline land and unfriendly neighbors who did not at that time understand the Mormon people.

From July 1887 until April 1922, Mrs. Udall served as the president of the St. Johns Relief Society of the stake, her husband serving at the same time as president of the stake. Ten years of that time they lived on the Old Mill Farm in Round Valley, thirty miles south of St. Johns. In 1912, the family built their present home in St. Johns, which stands as a monument to the taste and industry to these faithful pioneers.

In November 1927, this venerable couple was honored by their church in being called to preside in the Latter-day Saint temple in Mesa, Arizona. They served in that capacity until January 1934.[8]

On May 28, 1937, at three o’clock in the morning, Mrs. Udall passed from her earthly home after only a few hours of illness. The day before her death, she and her devoted husband were working together in her rose garden, her last contribution toward beautifying the grounds around the home she loved so much.

She was the mother of nine children, four of whom died in infancy. She is survived by her husband and the following children: Dr. Pearl Udall Nelson, Erma Udall Sherwood, Luella Udall Pace, David K. Udall Jr., and Judge Levi Stewart Udall; also by twenty grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. Interment took place on May 30 in Westside Cemetery, St. Johns, Arizona.

Ellis and Boone:

Ella Udall’s life is ably retold here, but one of her more remarkable accomplishments is the son and grandsons who served as judges and politicians in the state of Arizona and the nation. In 1914, son Levi began attending law school at the University of Arizona. With World War I service, he did not graduate but instead passed the bar exam in 1922. He was elected to Arizona’s Supreme Court in 1947 and served until his death twelve years later.[9]

Likewise, Levi’s two sons, Morris and Stewart, attended the University of Arizona law school immediately prior to World War II. During that war, Stewart served in Italy and completed fifty missions as a gunner on a B-24. After practicing law in Arizona, they both became prominent politicians. Stewart served as the Secretary of Interior under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, and Morris represented the state of Arizona in Congress for thirty years. Morris even ran for the Democratic nomination for president in 1976.[10] Because of David K. Udall’s sons and grandsons, the name Udall in Arizona is synonymous with the law and politics.

Ida Frances Hunt Udall

Pauline U. Smith

Maiden Name: Ida Frances Hunt

Birth: March 8, 1858; Hamilton Fort, Iron Co., Utah

Parents: John Hunt[11] and Lois Barnes Pratt[12]

Marriage: David King Udall;[13] May 26, 1882

Children: Pauline (1885), Grover Cleveland (1887), John Hunt (1889), Jesse Addison (1893), Gilbert Douglas (1895), Don Taylor (1897)

Death: April 26, 1915; Hunt, Apache Co., Arizona

Burial: St. Johns, Apache Co., Arizona

Since she was twelve years old, Ida had been going to choir practice with her girl chums and young men friends. Now that she was eighteen, her father was deciding to go to Sevier County, across the mountains to the east of Beavertown, where they would have to make new friends. They had been so happy in Beaver, and she couldn’t keep back the tears, until her father’s words, “Now my girl, I’ll put up with none of that,” made her dry them and prepare herself to make the best of her lot, as she did so nobly the rest of her life.

Although her father was a strict disciplinarian by nature, and to outward appearances almost stern, this was the first time in Ida’s eighteen years that he had ever used that tone of voice when addressing her. Brought up as John Hunt had been, schooled by the strong hand of adversity in meeting and subduing the frontiers since early childhood, there was one thing he would never tolerate and that was “boobyishness” in either man or woman. He had always taken great pride in Ida’s gifts. She must not be allowed to show the “white feather” now over such a small matter as being removed from dear old Beaver and not being privileged on this night of attending her usual choir practice and mingling with her young companions.

Ida was born March 8, 1858, at Hamilton Fort and was laid in her mother’s arms in a covered wagon.[14] John Hunt and his young wife Lois Pratt, who had just turned twenty-one, were moving from San Bernardino to Beaver when their first baby’s unexpected arrival compelled the company to remain at the crude fort. When mother and baby Ida were strong enough to travel, they journeyed to their destination fifty miles to the north, where they set up housekeeping near her mother, Louisa Barnes Pratt, who had made the journey to Utah with them to make her home in Beaver.

John’s father, Captain Jefferson Hunt of the Mormon Battalion, was heading this company of thirty.[15] He and the remainder of the group went on to Ogden to settle. Ida had received her well-integrated nature from the virility of noble ancestors and the diversity of their characters. She became very outstanding in Beaver’s social life where high standards of education and music were early established under the leadership of her beloved old teacher, Richard S. Horne. He called his pupils by numbers. Ida’s was number seven, and that number became a favorite with the old schoolmaster. Her voice was early recognized, and she was given the leading parts in the choir. She was chosen, when but a very young girl, to sing “The Star Spangled Banner” in the big Fourth of July celebration, this being the highest musical honor the community could bestow.

A very appealing story comes to us from the pen of her dear Grandma, Louisa Barnes Pratt:

In the year ’65—I went the second time to Salt Lake City, taking with me my granddaughter Ida Frances, and my Island boy [Ephraim], then able to drive the team. Ida F. was eight years old. She had yellow glossy [auburn] hair, of unusual dimension for one of her age. She was self-possessed and amiable, neither bashful or rude, always obliging. If she were invited to sing, she would never wait to be urged, as little girls generally do, but would seem pleased to contribute something to the enjoyment of the company she was in. We spent a week in President Young’s family; he called her his girl, because of her complexion; she so much resembled several of his children.

At that time, switches made of real hair were worn by the ladies, which they thought enhanced their beauty. It happened that Ida Frances’ hair was exactly the color of Sister Young’s who was very desirous of having a switch. One day in a playful mood she said to Ida, “How many dollars would you take for your pretty red hair?” Quickly Ida replied, “How many dollars would you give me?” After a moment’s thot she answered, “I will give you as many dollars as you are years old.” “But I am eight years old, will you give me that many?” “Yes, I will give you that many.” The child was thrilled at the thought of so much money, and urged me to consent to have it cut. “And what would you buy with the price?” I asked. “Well, I need a new dress, and so do my three little sisters; the material for these I will buy first. I need new shoes, too. I will buy a pair of high-topped ones with tassels on. (Such shoes were much worn by little girls at that time.) Then I’d like a little parasol; I have never had a parasol.” So the exchange was made to the satisfaction of both parties. When we reached home, great was the astonishment when the family saw Ida Frances’ bobbed hair; but when they saw her happy face and the things the price had bought, all were reconciled. While in the City, Ida Frances and I were photographed together.[16]

She was a great comfort to her little grandmother and learned many lessons from her.

Ida Hunt Udall (and daughter Pauline) on October 1, 1886, at Nephi, Utah, while living underground to avoid testifying against her husband. Her sister, Mary Hunt Larson, wrote that Ida "did not take the name of Udall for a long, long time." Photo courtesy of Marion and Wanda Turley Smith.

Ida Hunt Udall (and daughter Pauline) on October 1, 1886, at Nephi, Utah, while living underground to avoid testifying against her husband. Her sister, Mary Hunt Larson, wrote that Ida "did not take the name of Udall for a long, long time." Photo courtesy of Marion and Wanda Turley Smith.

Although Beaver became a cultural center, it had also attracted a very rough element, due to the mines on the west and the government soldiers there. It became necessary for the citizens of the town to have a peace officer possessed of rare courage, tact, and discernment. In John Hunt, they found just such a man. For fifteen years, he held this trying position.[17] Ida learned to do his office work for him. What pride he took in the education and aptness of his eldest daughter. (His entire schooling experience had consisted of a three month term when but a small lad in Nauvoo, Illinois.) Ida also grew into a bosom companion of her dear patient mother, a mother whose poise, dignity, and understanding of the human heart was so rare. When John was away on his perilous business, sometimes for days at a time, with no communication with home, Ida might have been seen with her arm linked in her mother’s pacing to and fro in the front yard under the quiet stars, to wear away the weary anxious hours of the long night.

When Ida was but fourteen years old, she held the position of bookkeeper for the Beaver woolen mills. Because of the neatness and legibility of her handwriting, she had been offered this position. She drew her pay in linsey-woolsey cloth, knitting yarns, cheese, etc., which helped the family budget, as the sheriff’s salary in those days was very meager. John and Lois now had a family of eight, six daughters and two sons. It fell to Ida’s lot to make up the cloth into dresses, not only for herself and little sisters, but even her mother, as she soon became an adept at sewing. Her grandmother Pratt had been trained as a tailoress back in New England, and she must have taken great pride in Ida’s taste and skill. She was one of the early school teachers of Utah, and inspired her granddaughter in scholarly pursuits also. Is it any wonder that Ida was “teary” at prospects of leaving her dear grandma and the life in Beaver?

Near their home on the Sevier was a little village of Joseph City, where Ida taught the little “log cabin” school.[18] She was a diligent reader, with a taste for classical literature. Her greatest solace, however, was her guitar and large repertoire of songs. Her brothers and sisters also had fine voices, and their regard for their eldest sister was almost akin to adoration. In the evenings, they would all gather round her and sing, while father and mother listened with the keenest appreciation. Wherever this family journeyed, the wilderness was made to resound with the melody and harmony of their lovely voices. Countless are the lives that have been uplifted by the songs learned under Ida’s leadership out of the Sevier and on the other frontiers where she blessed people’s lives. As the years passed by and the family went to homes of their own, they always counted on the time of Ida’s annual visit, when she would have new songs to teach them and they could rejoice in their old ones.

In 1877, John and his wife Lois, who always sustained him in any decision, followed the urge to move on to new frontiers and help colonize Arizona. On February 21, 1877, they were outfitted and in Beaver, bidding their loved ones good-bye. Ida and her sister May drove one of the teams on the long journey, which took three long weary months to complete. One can only imagine Ida’s feelings—a cultured, refined girl of nineteen years, facing the primitive and wild aspect of the Arizona wilderness. On the stub of a receipt book, written in lead pencil, she kept a daily record of that journey. After leaving Beaver on February 21, 1877, they traveled so far each day, encountering many difficulties en route. On March the 8th, which was her nineteenth birthday, they were just over the Arizona line for a short distance. A typical entry:

On March 15th started at daylight and traveled till sundown before we found water and that was 1½ miles from the road. The animals suffered very much for want of water, some of the horned stock having gone 53 hours without, and all of them 30 hours, but one of the oxen gave clear out. This water is about 26 miles from Pahgrim Pockets and there is plenty of it, but no grass. The next water called Tasha Spring was eight miles from there. The train started early, March 16, and some of the wagons were till after dark getting into camp, the animals being weak and most of the road very rough. Tasha Spring is a very pretty place, there being plenty of water and green vegetation, which was very refreshing to us. The ground seemed to be under cultivation by the Indians, and I will mention that we found two there, which were the first we had seen after leaving the settlements in Utah. It really seemed pleasant to see them and to know that some living beings besides us were in this barren desert country.

On March 19, she has this to report:

We came in sight of the long looked for river about 8 o’clock. I wondered when I looked at the great body of water why it had to be all in one place, when it would make the country so much more desirable all around to have it divided. We had been dreading the crossing of the river all the way, but we found it by far the pleasantest thing of our journey. The ferry which was Pierce’s Ferry, was in a splendid place. The water being very smooth, the wagons went across without the least trouble. March 20th, we laid by at the river, as they had to ferry and swim all the animals across and after we were all safely landed, we took all the music we had in the train (which was one guitar) and went out for a sail by moonlight.

The Hunt family arrived at Lot Smith’s camp at Sunset, April 29th, about noon. He was very kind and hospitable and made them a very generous offer to remain there, but they were all rather inclined to go on into New Mexico.[19] They arrived in San Lorenzo, Valencia County, New Mexico, on the 10th of May. There they stayed three weeks before going on to Savoia Valley which is fifteen miles into New Mexico. Here they resided for a little more than a year. The father and sons were away a great deal hauling freight, the Indians’ wool, and goods to Fort Wingate. The mother and four grown daughters and two little ones would have languished in utter loneliness without the rich background of culture from which they had grown. Letter writing became an art, horseback riding a recreation, and family singing an evening ritual. Making the acquaintance of the surrounding Indians and Mexicans became a hobby. Ida purchased a Spanish book and learned the language in a scholarly way.

As she and her family had been vaccinated for smallpox before their exodus [from San Bernardino, California], they were able to minister to the poor Southern immigrants who came down with the dread disease and escape its dire consequences. Her metal had been thoroughly tested and found pure gold, and her father’s heart delighted in her courage and fortitude in meeting the vicissitudes of frontier life so triumphantly. An opportunity appeared for her to return to her beloved Beaver and comfort her aged grandmother and again mingle in the society of her many dear friends. She accompanied her father as far as Snowflake and helped him select a homesite, as he had decided to yield to the inducements of his old friend of former years, William J. Flake, and bring his family to the fertile little Silver Creek Valley, where they were to make their last move.[20]

Each winter that Ida passed in Beaver, she taught school, and when she returned to Snowflake and her family, she left a sweetheart behind. During the next two winters, she taught school in the little log school houses at Taylor and then at Snowflake. It was at this time that David K. Udall came to Snowflake and visited the Hunt home. He was in search of a clerk for their newly established store in St. Johns who could speak the Spanish language. He had been informed that Miss Ida Hunt was capable. The agreement was made, and Ida took the two-day journey to St. Johns. The Beaver sweetheart did not measure up with this fine cultured man from St. Johns, who soon showed marked interest in Ida. After months of close acquaintance, Ida found David K. Udall to be one of all the men she had ever known who completely satisfied her every ideal. The story of their great love and checkered career is recorded in a beautiful journal, which is in possession of her posterity. She became his second wife on May 26, 1882.[21]

She passed through trying times in St. Johns.[22] A lawless element settled there. She always shuddered at the memory of the night when two men were lynched just across the way from her home. The groanings and oppressive gloom were not conducive to one’s dream of a honeymoon. In the spring of 1887, her husband moved her to the Milligan ranch, near Springerville. It was here that she felt the joys of young motherhood, even though borne amid much adversity. The high altitude and cold winters told dreadfully on her health. She had never been too robust, and a heart affliction, due to bad teeth, preyed on her as she bore her six children. Her husband was away from home a great deal with his church and civic duties, which left the rearing and caring of the children mostly to her.

Ida Hunt Udall with children, left to right: John Hunt, Gilbert Douglas, Pauline, Don Taylor (on lap), Grover Cleveland, Jesse Addison, c. 1898. Photo courtesy of Marion and Wanda Turley Smith.

Ida Hunt Udall with children, left to right: John Hunt, Gilbert Douglas, Pauline, Don Taylor (on lap), Grover Cleveland, Jesse Addison, c. 1898. Photo courtesy of Marion and Wanda Turley Smith.

She half-soled their shoes, barbered their hair, and made every article of clothing they wore until they were nearly grown. She made butter and cheese for sale, raised chickens and a garden each year, while at the same time cooking for hired men. It was a most uncommon thing to ever eat a meal to themselves as a family. Her husband ran a large farm, a gristmill, and freighting outfits, so as a result, there were many hired men. Her children consisted of a daughter, Pauline, the eldest, and five sons. She was a wonderful mother, whose government was that of love and firmness. She envisioned a goal for each child early in life and inspired each of them with confidence to attain it. Notwithstanding her frail body, the multiplicity of her every day duties, she always found time for the refinement of life. There were petunias blooming in the window or mignonettes in the yard. On the wall hung pictures, the frames of which she had fashioned from pine cones. The Mexican house in which she lived often ran tubs of water through its leaky roof, yet she never gave up the yearly going over its ceilings and walls herself with the whitewash brush. The rag carpet on the floor had taken hours of her time to make, but it brought comfort and cheer to her home.

On the Sabbath day, she was often seen in the cart with its shafts drawn by one horse, accompanied by her children and their cousins on the way to the school house, one mile distant, or perhaps walking another time. There a Sunday School class would be taught by her or a choir practice held. So her life ran on, in this little mountain home for fourteen years, scattering sunshine and cheer with her kindly words and beautiful singing voice. How common it was to see the hired men and boys, rough and uncouth as most of them were, gather around the coal-oil lamp, after the evening meal, and beg “Aunt Ida,” as everyone called her in her later years, to play the guitar and sing for them. She would, providing this one or that would perform in turn. How she loved these big-hearted mountain people and endeared herself to them!

After years of crop failures, due to prolonged droughts, the mortgage on the farm was foreclosed. It became necessary for this courageous woman, in connection with her devoted husband, to whom she always gave full measure of devotion, to make another start in life. In order to do this, they decided to apply for a homestead entry in the Greer Valley, twenty miles below St. Johns. David had been a mail contractor for some time, carrying the mail in buckboards from Holbrook to Springerville. In this valley, he could establish a mail station while he homesteaded, where Ida’s boys might care for the teams while David was away on business pertaining to many affairs, as recorded in his life’s story told in the book David K. Udal—lArizona Pioneer Mormon.[23] As the boys grew older, they carried the mail over these treacherous rivers and washes and across the sandy flats. The mail station soon became, out of necessity, a wayside inn for travelers to stop overnight on their way to St. Johns and farther south. The charm and hospitality of Ida’s nature made all classes at ease, forgetful of the primitive conditions under which she was living. They even had to haul water for culinary purposes for more than a mile. The anxiety over young sons detained by raging torrents, or of facing the long cold rides in winter, day after day, together with the hard work and privations and loneliness proved too much for Ida’s physical resistance. She claimed these busy days helping her husband get a new start were the happiest in her life, however.

She suffered a paralytic stroke in July 1908 in Anaheim, California, where her daughter had taken her for the purpose of building up her health. Ida lived for seven years after that as a semi-invalid, dividing her time with her sons who were attending high school in St. Johns and her daughter and husband and grandchildren residing in Hunt. She enjoyed most of all the companionship of her beloved husband and an occasional visit to her home in Snowflake with her aged father and brothers and sisters. She spent much time with her favorite books and reliving her past happy days in memory.

When the St. Johns dam and the subsequent breaking of the one at Hunt were swept away, her tired heart could stand no more.[24] Much of the strength and vigor of hers and her husband’s lives had been expended on these projects. As the angry flood swept destruction down through the valley she loved so well and across their homestead, death’s “bright angel” called for her. She passed away on the morning of April 26, 1915, [ten days after the dam broke] in the home of her daughter Pauline at Hunt, Arizona, after which she was beautifully laid to rest in the St. Johns cemetery. Her pallbearers were her five stalwart sons: Grover C. Udall, John H. Udall, Jesse A. Udall, Gilbert Udall, and Don T. Udall.[25]

The following tribute is an excerpt from the pen of her youngest son, Don: “I am proud to say that my mother possessed many noble attributes. She was a serene and intellectual person. From her New England grandparents on her mother’s side, she acquired that practical determination of going on with her tasks, and the power for sacrifice for righteousness’ sake was in her very blood. From her Hunt father and grandfather, she had been bred and born on the story of leaving all and going to a new country for God’s sake. This is in memory of one who was remarkable in the diversity of her friendship and so versatile in turning from music and song to the practical things. I feel everlasting pride for having been her son.”

Ellis and Boone:

Although Ida Udall’s father, John Hunt, was a polygamist, she was the only one of her siblings to choose that life (although admittedly some were too young). She lived incognito in Utah during her early married life, and her husband spent time in prison at Detroit. She and her children were responsible to provide much of their own support and even contribute to the rest of the family. Her siblings were never quite happy with her status as a second wife, which may have been as good as could be expected with the general poverty in Apache County. This slight undercurrent of discontent can be seen in Maria Smith Ellsworth’s exhaustive biography of her grandmother.[26] However, Ida, herself, never supported any such feelings; she gave herself wholeheartedly to David K. Udall.

On a different subject, analysis of the story from Ida’s grandmother Louisa Barnes Pratt is an example of why this printing of Pioneer Women of Arizona had to be a revised edition with footnotes and comments to clarify meaning, provenance, or authorship. With so many versions of the same sketch, these tools are often necessary to understand a particular story. As described by S. George Ellsworth, in 1874 Louisa Barnes Pratt began to revise her journals and saved correspondence with the idea of publishing a journal-memoir. This became the basis of Ellsworth’s book, The History of Louisa Barnes Pratt, published in 1998.[27] But in the 1940s, Nettie Hunt Rencher (sister to Ida and granddaughter of Louisa), Pauline Udall Smith (great-granddaughter of Louisa), and Louise Willis Levine (great-great-granddaughter) prepared this same journal-memoir for publication by the Daughters of Utah Pioneers; it was published in 1947 in volume 8 of Heart Throbs of the West with the title “Journal of Louisa Barnes Pratt.”[28] The story, as told in PWA, basically follows the 1947 publication, which is not surprising with Pauline Udall Smith as author/

But the major question is the authorship of the incident involving the sale of her hair. First, this story in PWA is one paragraph; it is divided into two paragraphs for Heart Throbs of the West. We have chosen to publish it in two paragraph, because the second paragraph may not have been part of Louisa’s original journal-memoir; at least it is not included in Ellsworth’s 1998 book. The story of the cut hair is a bit of folklore (using the anthropological definition) that both Rencher and Smith would have heard repeated through the years.[29] And we believe neither would have hesitated to insert it.[30] Second, that this paragraph was probably inserted by Rencher or Smith is also seen in the color reported for Ida’s hair: Louisa, reflecting the bias against red hair in Utah at that time, reported it as “yellow” (in both the Ellsworth book and DUP account), but the dialogue in the second paragraph calls it “red.” In addition, by the time this story was repeated in PWA, either Smith or RFC had changed Louisa’s “yellow” in the first paragraph to “auburn.”[31] Nevertheless, this story is a great addition to Ida’s history which would otherwise have been lost.

Finally, the FWP sketch also includes a poem, written on Ida’s twentieth birthday, by her grandmother, Louisa Barnes Pratt. It seems to only be found in the FWP account and is included here.

Well, I remember that eventful day,

As we were traveling on our way,

A fearful long and tedious journey that;

Trials of various kinds did we combat.

The Indians robbed, and filled our hearts with fear.

We walked o’er desert wild neith [sic] many a tear.

At length we made a barren camping ground,

And in a house on wheels, a babe we found;

‘Twas newly born, only a few days old’

Cozy and Quiet ‘spite of snow and cold.

In a rough old shanty we made a fire,

And coals were used to warm the little cryer.

Not much a cryer, She breathed the fresh cool air,

The wagon was a palace for all her care.

In the old ‘doby shanty, we gathered round,

A blazing fire; thirty souls were found

To number, besides the babe and mother;

Thankful we were for that, we had no others.

We waded in the snow, and shivered long;

At length we traveled on, when babe grew strong,

We reached where humans lived, and found a place

Among a people poor, yet rich in grace,

Old Cedar was forbidding to the sight;

But there we tarried many a day and night,

When we moved on, and came to Beaver Town.

Amidst wild sage and rocks we settled down,

Back o’er the desert, then they took the child;

With grief and sadness then my heart grew wild;

With fear that I would never see her more.

Four years rolled by, and I went to her door;

Over scorching deserts, and heated sand;

My way I wended to that pleasant land,

And there I found the chubby little girl,

With golden hair, so nicely did it curl,

And she could go to school, read A.B.C.

As glad to see grandma as she could be,

Seven months had passed away, much had she learn’d.

When she with her mama and all return’d

With me to Utah o’er the deserts wild;

Proving herself a pleasant patient child.

We watch’d her growth, and her development

Gave to our hearts both pleasure and content.

We gaz’d into the future and fore saw

A home for her, established by the law.

Where we could run and spend an hour each day

Exchange our smiles, and hear what she would say.

Our plans proved vain, for she was called to go

O’er untrod paths, to wilds of Mexico.

Tears from our eyes ran down to say fare well;

But now we have some cheerful news to tell;

The harbinger of hope, the faithful mail,

Brings the glad word, we may expect to hail

The absent one again when happy spring

Makes merry birds upon the branches sing,

And the highway is gay with the green grass.

Then shaking hands and kisses with the lass,

Will make us half forget that we were sad;

By knowing sorrow know we to be glad,

We hope to sing of Ida many years,

Joys multiplied, but with no bitter tears.

—Grandma Pratt, March 8th, 1878

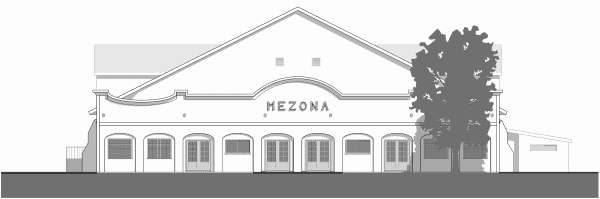

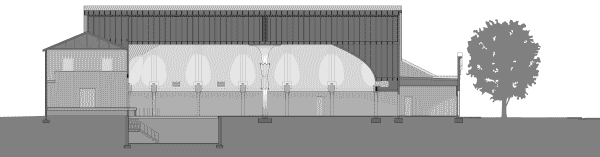

Pioneer Buildings: The Mezona. Few pioneer buildings have become as well-known as the Mezona in Mesa. Seeing the need for a large assembly hall, in 1907 John T. Vance purchased seven railcar loads of lumber and contracted with William Burton to build a 100 x 300 foot building, later known as the Vance Auditorium. Its hardwood floor made it perfect as a ballroom or roller skating rink, and, with a stage and motion picture machine, it was used for local musical productions and commercial movies. In 1919, the Church purchased the building, remodeled it by adding offices in the front (creating the iconic arched windows and doors), and renamed it the Mezona. it was used for stake conferences, funerals, citrus fairs, and temporary housing for large temple excursions. The building was remodeled several times and then deemed unsafe and demolished in 1971. The photo (left) is from a 1938 M-Men and Gleaner conference held in Mesa at Easter. The architectural drawins were made from elements seen in photographs from 1925 to 1940, written accounts compiled by Nancy Norton in her 2003 book Mezona Memories: A Sentimental Journey, and consultations with Dilworth Brinton Jr. Photo by Max R. Hunt; drawings prepared by Merlin Ellis, AIA; both courtesy of Ellis Collection.

Pioneer Buildings: The Mezona. Few pioneer buildings have become as well-known as the Mezona in Mesa. Seeing the need for a large assembly hall, in 1907 John T. Vance purchased seven railcar loads of lumber and contracted with William Burton to build a 100 x 300 foot building, later known as the Vance Auditorium. Its hardwood floor made it perfect as a ballroom or roller skating rink, and, with a stage and motion picture machine, it was used for local musical productions and commercial movies. In 1919, the Church purchased the building, remodeled it by adding offices in the front (creating the iconic arched windows and doors), and renamed it the Mezona. it was used for stake conferences, funerals, citrus fairs, and temporary housing for large temple excursions. The building was remodeled several times and then deemed unsafe and demolished in 1971. The photo (left) is from a 1938 M-Men and Gleaner conference held in Mesa at Easter. The architectural drawins were made from elements seen in photographs from 1925 to 1940, written accounts compiled by Nancy Norton in her 2003 book Mezona Memories: A Sentimental Journey, and consultations with Dilworth Brinton Jr. Photo by Max R. Hunt; drawings prepared by Merlin Ellis, AIA; both courtesy of Ellis Collection.

Notes

[1] This sketch was submitted to the FWP six weeks after Udall’s death and appears to be the funeral eulogy and life sketch. Nelson was living in Utah when PWA was published, which may be the reason Clayton did not included it.

[2] “David King Udall,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 1:325–28; Udall and Nelson, Arizona Pioneer Mormon.

[3][3] Sam Walter Foss, “The House of the Side of the Road,” in Cook, One Hundred and One Famous Poems, 9–10.

[4] Sarah Elizabeth Carmichael (1838–1901) published her first poem in the Deseret News in 1858. About a year after her marriage to Jonathon M. Williamson, an army surgeon at Camp Douglas, she suffered a severe mental decline; http://

[5] Theodore Belden Lewis (1843–89) came to Utah in 1865 and was baptized a year later. He served a mission in the South and became an educator in Utah, teaching in Provo, Payson, Nephi, Salt Lake City, and Ogden. He married into the Coray-Dusenberry family of prominent early educators in Utah and became a supporter of free, public schools. Jenson, LDS Biographical Encyclopedia 3:149–50; Wilkinson and Skousen, Brigham Young University, 31–49. Mrs. Brown is unidentified.

[6] The deaths all occurred on December 14, 1870, and included her mother, Margery Wilkerson Stewart (born 1832); brothers Charles (1857), Herbert (1861), and Edward (1863); half brother Urban Stewart (1857), son of Artimacy Wilkerson Stewart; and half brother Levi Stewart (1848), son of Melinda Howard Stewart. Udall and Nelson, Arizona Pioneer Mormon, 249–50.

[7] Although spelled Spillbury in the FWP sketch, this is probably Sarah Ann Higbee (1853–79), who married Alma Platte Spilsbury in 1869; her daughter Fanny married Isaac Dana and lived in Mesa. The surname is spelled both Spilsbury and Spillsbury.

[8] Peterson, Ninth Temple, 238–46.

[9] Ida Hunt Udall’s sons Jesse and Don T. also became lawyers and judges. Jesse was elected to the state Supreme Court in 1960. Murphy, Laws, Courts, and Lawyers, 97–99, 153, 162, 166, 185.

[10] Ibid., 176; Carson and Johnson, Mo: the Life and Times of Morris K. Udall; Ellis, Latter-day Saints in Tucson, 79, 101; Udall, St. Johns, 79, 87–88.

[11] “The Life of John Hunt (1833−1917),” in Clayton, PMA, 236−38; “John Hunt,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 3:417–18; Rencher, John Hunt—Frontiersman.

[12] “Lois Barnes Pratt Hunt,” in Rencher, John Hunt—Frontiersman , 91−96.

[13] “David King Udall,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 1:325–28; Udall and Nelson, Arizona Pioneer Mormon.

[14] Hamilton Fort was four miles south of Cedar City. First settled in 1852, it has also been known as Shirts Creek, Fort Walker, and Sidon. Van Cott, Utah Place Names, 175.

[15] “Jefferson Hunt,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 4:747–48; Smith, Captain Jefferson Hunt of the Mormon Battalion; Sutak, Into the Jaws of Hell.

[16] This has been reformatted to the 1947 version, with PWA additions in brackets. See comments by Ellis and Boone to understand the provenance and editorial changes in this story.

[17] Osmer Flake wrote, “John Hunt was Sheriff of Beaver County for twelve years, and during the whole time, depended on William Flake for his chief helper. There were rough times, but he [Flake] never carried a gun except on the chase.” Flake, William J. Flake, 70.

[18] Generally, this town in Utah is known as Joseph (named after Joseph Angell Young), whereas the town in Arizona is today known as Joseph City.

[19] Before the Hunt family left Utah, Brigham Young wrote a letter to Bishop John Murdock stating, “I should like Bro. John to go and join Bro. Lot Smith at the Little Colorado, either to locate with Lots’ Camp or at any of the other Camps on that River. If Brother Hunt after getting there felt he would like to go to the brethren who are laboring with or near the Zuni Indians all right.” Brigham Young was even willing to let John Hunt join the group headed by Daniel W. Jones. Letter from Brigham Young to John Murcock, January 17, 1877, copy in possession of Ellis.

[20] In mid-September 1878, William J. Flake talked with Apostle Erastus Snow about the new settlement of Snowflake and suggested that John Hunt be called as bishop. This call was extended, the family moved from New Mexico to Snowflake, and Hunt served for thirty-one years. The statement that John Hunt was yielding to the inducements of William J. Flake in making this move may be technically correct, but in reality, Hunt moved because he was responding to a call from Church leaders (through Erastus Snow). Flake, William J. Flake, 79–80; Erickson, Story of Faith, 9; “John Hunt,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 3:417–18; “John Hunt,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 3:417–18; Rencher, John Hunt—Frontiersman, 74–75, 81–82.

[21] This was a polygamous marriage; David K. Udall’s first wife was Eliza Luella Stewart Udall, see 737. For a review of Udall’s legal problems in Arizona as a polygamist, see Miller, “St. Johns’s Saints: Interethnic Conflict in Northeastern Arizona, 1880−85,” 66−99.

[22] Catharine Romney details many of the events in St. Johns during this period. Hansen, Letters of Catharine Cottam Romney, 21−110.

[23] Udall and Nelson, Arizona Pioneer Mormon.

[24] For information about the Lyman Dam disaster of 1915, see Sarah Wilmirth Greer DeWitt, 152; Wilhelm and Wilhelm, History of the St. Johns Arizona Stake, 65–69.

[25] Ida’s son Grover Cleveland was born after David K. Udall returned from his prison term in Detroit, and so the new baby was named after the president of the United States who issued a pardon in December 1885. Udall and Nelson, Arizona Pioneer Mormon, 142–43.

[26] Ellsworth, Mormon Odyssey.

[27] Ellsworth, History of Louisa Barnes Pratt, xiv–xv.

[28] Pratt, “Journal of Louisa Barnes Pratt,” 189–400.

[29] Greenway, Folklore of the Great West, 1–3. Greenway wrote, “It is the responsibility and pleasure of folklorists to study these people [‘these islands of separate enclaves’]—recording their customs, attitudes, beliefs, artifacts, and arts—preserving their memories for the sake of preserving knowledge; studying the processes of their thinking and behavior, the better to understand themselves;” 3. Greenway’s book begins with “Memories of a Mormon Girlhood” by Juanita Brooks, 17–46.

[30] Compare Ellsworth, History of Louisa Barnes Pratt, 305, with Pratt, “Journal of Louisa Barnes Pratt,” 353–54.

[31] The exact color of Ida’s hair when young is open to some discussion. In her own memoirs she wrote: “President Young called me up to him, admired my long yellow hair, took me on his knee & kissed me, saying I was certainly his girl because he claimed all those with sandy hair.” Ellsworth, Mormon Odyssey, 6.