T

Roberta Flake Clayton, Eva Tanner Shelley, Delilah Jane Willis Turley, and Mary Adelia Pace Tyler, "T," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 709-736.

Eliza Ellen Parkinson Tanner

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP[1]

Maiden Name: Eliza Ellen Parkinson

Birth: September 8, 1857; San Bernardino, San Bernardino Co., California

Parents: Thomas Parkinson and Mary Ann Bryant

Marriage: Henry Martin Tanner;[2] January 25, 1877

Children: Martin Ray (1878), Thomas William (1880), Julia Alice (1882), Mary Ida (1884), Rollin C. (1886), Hazel (1888), Daniel Kimball (1889), Marion Lyman (1890), Arthur (1892), Leroy Parkinson (1895), George Shepherd (1897), Donnette (1899), Mary (1901), Paul Moroni (1906)

Death: August 17, 1930; Joseph City, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Joseph City, Navajo Co., Arizona

The subject of this sketch was born September 8, 1857. Her parents were Thomas and Mary Ann Bryant Porter Parkinson, who came to America from Australia and settled in San Bernardino, California, where Eliza was born. Shortly after her birth, her parents moved to Beaver City, Utah.

Early in life, she decided to become a school teacher, so she improved every opportunity to get an education and taught school both in Beaver City and later in Joseph City, Arizona.[3]

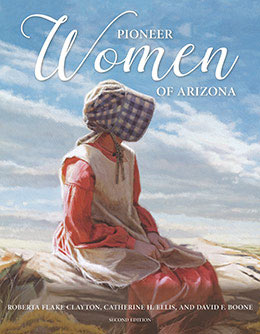

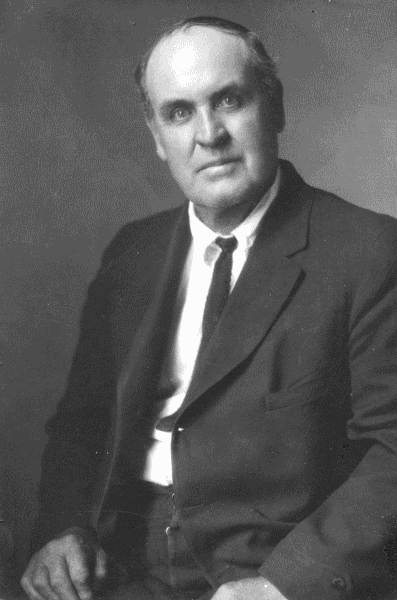

Henry Martin and Eliza Ellen Parkinson Tanner with children, left to right, Julia, Martin Ray, and Thomas. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Henry Martin and Eliza Ellen Parkinson Tanner with children, left to right, Julia, Martin Ray, and Thomas. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Eliza joined in all the sports and entertainments of that day the town afforded. She had a good memory and often did her part by reciting humorous poems. She was very popular because of her jovial nature and had a wide circle of friends and her share of suitors. She seemed unable to choose among the latter until Henry Martin Tanner offered her his heart and hand. They were quietly married on January 25, 1877. During these days of ’76 and ’77, many of the strong, able-bodied, well-to-do men were being called to settle Arizona, Nevada, and Idaho by the leaders of the Mormon Church, and Henry was called to Arizona. So with his bride, he made preparations for the journey into the barren wastes of Arizona. This trip lasted eleven weeks and was filled with hardship. Henry, having a good saddle horse, was delegated to look after the loose stock of the company with which they traveled.[4] This left Eliza to drive their four-horse team a great deal of the way.

One morning, they saw horses coming back and found that they belonged to a company that was a few days ahead. It was decided that Henry should take the horses ahead to the owners, so Eliza had to drive the team that day, though the wind was blowing a perfect gale. Trees were uprooted and were falling all around. One fell across the trail that served as a road, right in front of her team. This greatly frightened the horses, but she managed to control them and drove around the tree and back onto the road. When she reached camp, she had to go to bed at once with a sick headache and said that was the hardest day she had spent.

Scarcity of water was the greatest problem on the route. When found, it sometimes took two days for the little springs to supply enough to water the animals and fill up the large water barrels that were carried on the outside of every emigrant’s wagon. At one time, they had been without water until the animals were exhausted, so Henry was sent out to find water. He traveled for hours and at length turned back, disheartened. Getting down from his horse, he knelt in prayer. He then remounted and continued on his way back to the company. On nearing the camp, he looked up and saw some green trees and felt impressed to go there. On reaching the trees, he found a small spring with plenty of water. He called to the company, “Here is water.” But they did not believe him until he dipped his hat brimming full and threw it into the air. Eliza ran to him, and together they praised God for his kindness.[5]

They came to the Colorado River and crossed by Pearce’s Ferry. They floated their wagons across the river, and Eliza, much afraid, rode in theirs. They swam their livestock. From there they came to Flagstaff.

Finally, on May 1, 1877, the Tanners settled in the old fort at St. Joseph (now Joseph City), built as a protection against the Indians. However, the people believed it was better to feed the Indians rather than fight them.[6]

Henry Martin and Eliza Ellen Parkinson Tanner's golden wedding anniversary. Photo courtesy of DUP album, Snowflake-Taylor Family History Center.

Henry Martin and Eliza Ellen Parkinson Tanner's golden wedding anniversary. Photo courtesy of DUP album, Snowflake-Taylor Family History Center.

The settlers were living in the “United Order,” which meant that they lived as one large family. Each separate family had its sleeping quarters, but all ate at the same big table. Each one was assigned his or her special work—the women taking turns doing the cooking and other tasks.[7] Henry was to look after the cattle and was away much of the time. Eliza was very homesick and lonely, and for the first few weeks wore her bonnet all the time so that no one would see the tears she could not check.[8]

The cattle were taken out to Mormon Dairy, near Flagstaff, in the summer time, and the women who could make butter and cheese went out there. As Eliza was an expert at both, she spent much time out at the dairy. Not alone at these was she efficient, but at spinning, weaving, knitting, sewing, and as a cook and housekeeper she was unsurpassed. She was always busy, as it gave her less time to think of her family and friends so far away. She would wash the wool shorn from the sheep, card, spin, and weave it into cloth or knit it into stockings. When clothing could no longer be used for wearing apparel, it was torn into inch strips which were sewed together, then woven into carpets. With fresh clean straw underneath to make it warmer and softer, the new rag carpets were stretched and tacked down on the floors, and no woman was ever more proud of her imported Turkish rugs than were the pioneer women of their own striped or “hit and miss” homemade rag carpets.

Everyone who ever lived on the Little Colorado River knows the problem they had trying to settle the red, brackish water sufficiently for use.[9] It was hauled from the river two miles away in barrels on low sleds.[10] Plaster of Paris and buttermilk were used to settle it. Probably six inches of clear water could carefully be dipped from the top of the barrel, then the remainder would have to be emptied and the process repeated. In spite of this terrible handicap, Eliza’s laundry always looked white and clean.[11]

Eliza did her part to establish a tannery, a gristmill, a sawmill, and a sorghum mill.

In 1886, the Tanners moved to their own homestead, about a mile east of the fort.[12] Their house was only partly finished, but Eliza was glad to have a home of her own.

Through all the trails and tribulations, much happiness was had through the Church and with her babies. There were no doctors, and the women helped each other during sickness and death. The men became quite expert at setting limbs, extracting teeth, etc., and no one was ever too busy to help another who was in need. Always holding to their ideals, and Eliza always “backing” her mate in all of his undertakings—thus they lived.

From the little community in which they lived, Henry was the first to be called by his church to go on a mission.[13] It was just after they had moved to their unfinished house. He left for Great Britain, and she remained at home with her five small children and a new arrival expected. She understood how to manage the animals on the farm and encouraged the older boys to do the work of real men “to help father fill his mission.” Henry suffered severely from ill health and had to be released to return home after being away but eleven months.

Eliza was a counselor in the Relief Society for twenty-five years and was always at her post unless interfered with by sickness. She possessed the talent of music and led the singing in Sunday School and other Church gatherings in early days. She taught her children to sing and appreciate good music. She read to them from the best of books.

Honesty was one of her greatest virtues and by precept and example taught it to her children, with the result that they are all honored members of their different communities. Three of them have been school-teachers, and all are honest, industrious, and dependable.

Henry and Eliza celebrated their golden wedding anniversary on January 25, 1927. At this time all of their eleven children were alive, grown, married and had families.

Eliza died at the age of seventy-three, on August 17, 1930, surrounded by her children, who honor and praise her for her loving care, her faith, her integrity, and the example she set before them.

Ellis and Boone:

When Rollin C. Tanner, son of Eliza, was growing up in northern Arizona, he traveled back and forth with his parents and thought, “There must be a better and faster way to travel—better vehicles, better roads.” After better vehicles came to Arizona, he devoted his life to providing Arizona with better roads. Eliza and Henry taught their children to work, often from before sunrise until the work was done or until sundown. Although “there were implements to repair, soap to make, wood to cut, [and] animals to feed,” there was also time for recreation. Often these programs included songs and poetry, and “some of the poems [that Rollin] Tanner learned during those days he was still reciting to his grandchildren 70 years later.”[14]

Another of Eliza’s sons, George S. Tanner, became a well-known collector and writer of the history of the Little Colorado River settlements, particularly Joseph City.[15] Many of his materials are available at the Cline Library associated with Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff and at the University of Utah. He wrote a remarkably candid essay about Eliza and Emma Tanner, much of which is included in the sketch for Emma Stapley Tanner, next.

Emma Ellen Stapley Tanner

Eva Tanner Shelley[16]

Maiden Name: Emma Ellen Stapley

Birth: November 30, 1862; Toquerville, Washington Co., Utah

Parents: Charles Stapley Jr. and Sarah Parkinson

Marriage: Henry Martin Tanner;[17] March 24, 1886

Children: Charles Stapley (1890), Eva (1891), Horace E. (1894), Clifford (1896), Golden J. (1899), Francis Sidney (1904)

Death: April 17, 1933; Joseph City, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Joseph City, Navajo Co., Arizona

Emma Ellen Stapley Tanner was born November 30, 1862, in Toquerville, Washington County, Utah. She was the third of eight children born to Charles Stapley Jr. and Sarah Parkinson. Her parents were of English descent. They moved to Toquerville in 1858 with only three families preceding them.

Because of her pioneer life, she underwent many hardships, such as picking cotton barefooted and helping her father with his truck gardens. Her father tanned the hide to make her first shoes, and she remembers wearing a dress made from an old wagon cover. Her first schooling was given her by an emigrant lady. She won the prize for learning the most Bible verses and reciting them in Sunday School. She was a beautiful girl and was always ready and willing to help others. This made her a general favorite in the family.

Emma Ellen Stapley Tanner. Photo courtesy of DUP album, Snowflake-Taylor family History Center.

Emma Ellen Stapley Tanner. Photo courtesy of DUP album, Snowflake-Taylor family History Center.

She was always shy and timid, never hunting a position, but was always faithful in performing anything assigned to her. She sang in the choir from the time she was fourteen until she married. When the first Primary was organized in Toquerville by Sisters Eliza R. Snow and Zina D. Young, she was chosen as counselor by Sister Adelaide Savage, which position she held until her marriage to Henry M. Tanner in St. George on March 24, 1886.[18]

After her marriage, she came to St. Joseph, Arizona, where she began pioneer life again. For a short time after coming to Arizona, she lived in the same house with Aunt Eliza Tanner, Henry M. Tanner’s first wife, on a ranch about a mile and one-half east of Joseph City.[19] Then for a few years, she lived in a log house just across the street north of the John McLaws home. Later, a small house was built for her just west of the present location of the Joseph City Cemetery and about a quarter of a mile from Aunt Eliza’s home.

She was chosen as a counselor in the YWMIA in 1887. For a time this association printed a small paper known as the Literary Star, and in 1890 she was one of its contributors. On April 16, 1888, the Primary was organized in St. Joseph with Hannah Petersen as president and Emma Ellen Stapley Tanner as first counselor and Sariah Smith Bushman as second counselor. These women were released with the reorganization of the Primary on January 29, 1892.

She was chosen second counselor in the Relief Society in 1903, which position she held until 1915. She also served as block teacher for a number of years, many times having to walk the one and a half miles to her meetings and to do her teaching.[20]

In the summer of 1905, Mother was subpoenaed by the Federal officers and taken to Prescott to answer the charge of being a plural wife, but nothing came of it, probably because of the inability of the officers to prove anything.[21] Up until then she had gone by the name of Emma Stapley to all except her close friends.

In 1911, Mother had a severe illness. They named it inflammatory rheumatism. Her hands and feet were swollen and pulled out of shape and the suffering was intense. We did everything we could for her, but it seemed to be a losing battle until one Sunday, Father brought Brother Sullivan Richards home with him.[22] They gave Mother a blessing promising her she would regain her health and be able to take care of her family. From that time she began to mend and was soon able to enjoy life with her loved ones, never forgetting to express her gratitude to our Heavenly Father for this wonderful blessing.

She told of making a trip to Toquerville, Utah, in the winter of 1893 when I was two years old, along with Uncle Rube Parkinson’s family.[23] Coming back, we were six weeks on the road. It was cold, snowy weather, and the snow got very deep. Going over the mountains near Lee’s Ferry, our covered wagon tipped over. It was a big scare, but no one was hurt.

She was very thrifty—always finding ways of helping with family income. She made her own soap. She saved her waste fats and cracklins, and when she wished to make soap, she burned cottonwood in the stove for several days.[24] From the ashes, she would make lye. This she used with the fats to make soap. She also used this lye to get the hulls off the corn to make hominy.

She was the mother of six children. Three of her children preceded her to the Great Beyond. Her oldest child was born in 1890. He lived only two weeks.

In the fall of 1902, a terrible epidemic struck Joseph City in the form of diphtheria. Horace, a very promising lad of thirteen, died while his father was on a freighting trip to Keams Canyon. Because of the fears of the disease, no funeral was held. These were dark days for the family.

Her baby boy, a sweet lovely child, developed a heart ailment which caused his death in 1917 when he was thirteen years old. This was a terrible sorrow to her. It left her almost alone on the ranch as Golden was in school and Clifford was in the army in France, being called to the front the night the armistice was signed.

She worked in the St. George Temple with her sister Mary from September 1929 until April 1930 when her health failed.[25] She came home but was too independent to let anyone take care of her.

To those who knew her best, she was Aunt Emma. She was thrifty and uncomplaining—having early acquired the habits of punctuality and honesty. She was a fine seamstress and helped with the family income for a number of years. To those who bought her butter, eggs, and vegetables, she always gave a good measure. She made it a practice to save a little, hoping that in her last years she would not be compelled to depend on others. She was never more happy than when she could help someone in need.

In later years, they moved from the ranch to Joseph City, where she died very suddenly after a hard day’s work on April 17, 1933, with only her husband and a close friend, Samuel U. Porter, present. She was buried in the Joseph City Cemetery April 19, 1933.

We appreciate her fine example of faith and loyalty.

Ellis and Boone:

George S. Tanner wrote a combined sketch for Eliza and Emma Tanner; it seems appropriate to include most of it here:[26]

When people are writing up their pioneering experiences, the men usually get most of the attention. This may not be fair as women sacrifice as much and contribute as much as the men. This article is about Henry’s two wives.

Eliza Parkinson, wife number one, was born in San Berna[r]dino. . . . Emma Stapley, the second wife, was born . . . in Toquerville, Utah. Both wives were accustomed to pioneering conditions. . . .

Eliza came to Arizona with her husband in May of 1877, and the couple moved into a room in the old fort which was still in the course of construction. She had been used to better things in Beaver and the prospects of making a home and raising a family in this desert waste was almost more than she could stand. Henry related to this writer that she was in tears much of the first year, but she matured rapidly. She was only nineteen at the time of her marriage and she backed her husband and the other men in the colony as they labored to control the river and bring their farms into production.

Emma married Henry M. Tanner in the St. George Temple in March of 1886 and came to Arizona with him. She joined Eliza and her five children who were moving into a new home three quarters of a mile east of the old fort. Emma was a little older at the time of her marriage; she was twenty-four. Eliza was now twenty-nine.

Joseph City friends about 1928: (seated) Margaret Hunter Shelley, 632; James Shelley; (standing, left to right) Emma Stapley Tanner; George Thomas Rogers; Emma Swenson Hansen, 245; Henry M. Tanner; Eliza Parkinson Tanner, 709; Sarah Kartchner Miller, 458; and Sophia de la Mare McLaws, 427. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Joseph City friends about 1928: (seated) Margaret Hunter Shelley, 632; James Shelley; (standing, left to right) Emma Stapley Tanner; George Thomas Rogers; Emma Swenson Hansen, 245; Henry M. Tanner; Eliza Parkinson Tanner, 709; Sarah Kartchner Miller, 458; and Sophia de la Mare McLaws, 427. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

This writer has learned nothing about how these two women made out when thrown together in this pioneer situation. The church was doing its best to indoctrinate its members with the idea that polygamy was a righteous principle and most women, if they did not agree, would have remained silent. The writer, a son of the first wife, never heard the subject discussed. In any case, Emma did not remain long in the home with Eliza and her fast growing brood but was moved about for a while until Henry was able to provide a minimal cabin for her a quarter mile west of the other home.

Polygamy was a difficult role to live. The first wife was called upon to share her husband with another woman and the second or additional wife had perhaps an even more difficult role to play. This writer, who was one of the younger children, remembers that Emma was called Emma Stapley by the people of the village—she couldn’t even share her husband’s name. . . .

Henry may not have been the wisest of polygamists but he tried to be fair. He spent alternate weeks with each wife and they in turn provided his meals and cared for his laundry during his stay with them. There was evidence of affection and respect between him and each of the wives and there was no question that each of the wives loved him. He provided for each to the extent of his limited resources but each was thrown on her own resources in providing for many things. For example, each wife was provided with a small herd of dairy cows which the children milked and butter was made and sold to a peddler who called twice a week. Each wife also had a garden plot which she and her children tended and during the summer sold the produce. The money obtained from dairy and garden was carefully hoarded to be used to buy clothes and items from the village store. Henry bought many things like flour and sugar in quantities and they were divided between the two homes. But this still left plenty of things for the thrifty wife to buy. . . .

Eliza and Emma were superior women. They were cousins which may have had something to do with Emma being brought into the family. Though they may never have ‘loved’ each other as some plural wives have claimed to have done, they respected each other. When the chips were down, each knew she could count on the other. Eliza was in Emma’s home when her children died. I remember the event when Horace died, though I was only five years of age. There was a diphtheria epidemic and Eliza remained at Emma’s home so as not to spread the disease. Father was away freighting and Julia looked after us younger children. Emma would have done the same had the situation been reversed. There was some rivalry between the children of similar age in the two families but possibly not much more than was the case in large families in monogamy. I am not particularly proud of my own behavior which could have been more brotherly.

Both families turned out well. Eliza and Emma can be proud of them.[27]

Rebecca Redd Hancock Tenney

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP

Maiden Name: Rebecca Reed Hancock

Birth: December 14, 1877; Leeds, Washington Co., Utah

Parents: Mosiah Lyman Hancock and Margaret McCleve[28]

Marriage: George Quail Tenney; December 24, 1895

Children: Warren Q. (1897), George Dewey (1899), Joseph Chester (1901), Shirley Christy (1904), Carvel Gerald (1907), Bernie Harold (1910), Beatrice Valeria (1912)

Death: September 17, 1946; Taylor, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Taylor, Navajo Co., Arizona

Born in Leeds, Washington County, Utah, on December 14, 1877, Rebecca was the daughter of Mosiah L. and Margaret McCleve Hancock.

When less than two years old, she was brought to Arizona by her mother and the older members of the family. One evening, after they had made an early camp, Rebecca and one of her older sisters went out to hunt cedar berries and pine gum. She got tired and thought to return to the camp alone. When she came to the road they had left, she started back over the road they had traveled that day and trudged on and on looking for camp. When the sister returned and Rebecca was not with her, great excitement reigned. Everyone set out on the search. Finally her little footprints were found in the dusty wagon tracks, and her brother Joseph followed her for two miles before he overtook her. When she returned to camp, she was seated upon his shoulders and greeted all with a happy smile.

The family reached Taylor, Arizona, on New Year’s Day 1880, sharing in all the hardships and privations of those early days.

As soon as she was old enough, Rebecca started to the village school. Rebecca was the twelfth child in the family and was allowed to do pretty much as she pleased. Her mother was a nurse and spent much of her time with the sick, so the child was left to visit and play with her little friends, to wander through the fields and over hills. When she got large enough, she used to go to the field and help her brothers with the crops. Especially did she like hay hauling time, as it was such fun to “tromp” the sweet-smelling alfalfa, and then to ride to the barn on a mountain of it.

When Rebecca was eleven years old, her sister and her intended husband were going back to St. George, Utah, to be married, and decided to let Rebecca go along.[29] Frank M. Perkins, besides being the successful lover, was the owner of a fancy team of horses. When only a few days’ travel from home, they camped for the night and hobbled out the team. What was their amazement when they looked for the horses next morning to find them gone, hobbles and all. Mr. Perkins hunted until past noon, but no trace of them could be found. While the poor stranded people were trying to decide what to do, along came some men driving a bunch of Indian ponies. They stopped and very solicitously inquired what the trouble was. Upon being told, they generously offered to loan the travelers a pair of their ponies to work until they should reach the next settlement, which was about a week’s travel away provided you had a good team. The offer was accepted and arrangements were made to leave the team at Moabi.[30] There was a young man by the name of John Lewis along. He volunteered to return to Taylor and get a team belonging to Mr. Perkins’s brother and join the party at Moabi. After these arrangements were made the men rode away, in a different direction from that taken by Lewis, and also away from the road taken by the family of Rebecca.

The journey was resumed, but the little rats of ponies were balky, small, lazy, and everything that would tend to aggravate anyone, but Frank was on his best behavior, and moving at all was better than staying in camp, so they plodded on and, after many days, reached the settlement where they stayed until help came from home. While they were waiting, they learned positively, that the men who loaned them the team had stolen theirs, and that this span of ponies and the others they had were from the Navajos.

Rebecca Hancock Tenney with baby Warren Q. Tenney. Photo courtesy of Ida Webb Collection, Taylor Museum.

Rebecca Hancock Tenney with baby Warren Q. Tenney. Photo courtesy of Ida Webb Collection, Taylor Museum.

Rebecca made the best of the trip, enjoyed climbing the little hills and rolling down the smaller ones, and though there were hardships, she didn’t mind them and enjoyed the visit with newfound friends very much.

Among the girlhood pleasures of Rebecca were swinging on the long rope, or sometimes chain or cable swings suspended from strong limbs of trees, wading, and when there was enough water in the Silver Creek, swimming. They played games such as “steal base,” “run sheep run,” “pom pom pullaway,” and played in the moonlight or around a bright bonfire. They played Danish ball and baseball, and even after she became a mother, she belonged to a basketball team. She was very fond of horseback riding and dancing. She was a member of the Sunday School choir and liked to go to choir practice held at the homes of different members, where oft times such refreshments as parched corn and molasses candy were served.

When Rebecca was about twelve years old, some Mexicans came through the towns with a trained bear that used to dance, play dead, and perform many other stunts. Rebecca was a born mimic and often dressed up and imitated the antics of that bear for the amusement of her playmates.

She continued to help in the field, but when she tired of the work she would steal away, down to the grassy banks of the creek. There were two grass-grown islands in the stream, which she claimed as her own, by right of possession. From these, she had bridges so that she could go from one island to the other. She very nearly drowned one time when she slipped from her pole bridge into the stream that was high from spring floods. Had it not been for a clear head and strong arms, she probably would never have lived to tell the story of her life.

There was one incident in her childhood, over which she often laughs now, but that was not so funny when it happened. She used to drive the cows out to graze, and of course in those days, girls did not ride astride. As she did not have a sidesaddle, she had to ride a man’s saddle sideways. This was pretty hard riding, so one day she decided to put a pillow in the saddle. During the ride she lost the pillow, and it was one of her mother’s best ones. The pillow had to be found before she returned home, and that was some task, going back through the cedars to hunt for it. But luck was with her; the pillow was finally found, but she did not take it again.

The farmers used to haul their surplus hay to Fort Apache or Holbrook. One day, the Hancocks had their wagons loaded high with baled hay. Two of the brothers were going to take it to Holbrook, but as one of the boys was sick and there seemed to be no one else, Rebecca was enlisted to drive the extra team. One of the horses, Old Cap, was a balky rascal, and the Rio Puerco arroyo seemed to be his favorite place to lie down or quit pulling. So “Becky” had something to worry about from the time she left home until the stream was safely reached and crossed, which it was. For once Old Cap pulled his share of the load thru the quicksand all right.

On Christmas Eve 1895, Rebecca was married to George Q. Tenney, at Taylor, Arizona. Another couple was married at the same time, and a big dance was given which was attended by people for miles around. Rebecca looked very nice in her cream-colored, China-silk dress and orange blossoms. It looked like the beginning of a very happy life, but many trials have crept in, as they do in most lives. She has been a widow since 1920.

During the early years of her married life, she moved around a great deal, living in Pinedale, Mormon Dairy, and then back to Taylor, where she has made her home. She is the mother of seven children, two of whom died while young, and two of her boys joined the Navy during World War I. The eldest died after returning home.

She did her part during that terrible struggle, aside from that of sending her sons, by buying two Liberty Bonds and doing much knitting and sewing for the Red Cross. She bought Thrift Stamps and practiced close economy in foods, clothing, etc. during, and long after, the war.

Rebecca has raised her children and provided for herself by going into homes assisting with housework and the care of children.

Ellis and Boone:

Roberta Flake Clayton submitted this biography to the FWP in Arizona but for some reason did not include it in PWA. Rebecca Tenney continued to live in Taylor and died there on September 17, 1946.

Rebecca Hancock Tenney lived for nearly thirty years as a widow, as did many of the women in this volume. She raised her children by doing housework and babysitting; poverty was probably always at her door. Her situation was very similar to her mother-in-law, Clara Longhurst Tenney, as illustrated with this story:

On a lonely ranch about two miles south of Taylor lived the widow Clara Tenney with her six unmarried children. . . . She was a convert from England and had moved on this ranch thinking the farm would furnish employment for her four boys. They raised a pretty good crop of vegetables but did not have much to live on. The time came when their store of flour and other supplies were exhausted. The mother prepared dinner of just a mess of parsnips from their garden. Just as it was ready to serve, the Ward Teachers come. They were Brothers Butler and Hanks. True to her custom, this hospitable mother had set the table with her best linen and silverware, and had filled the sparkling glasses with water. Her nice things were relics of better days. She invited the visitors to join them in their meal. The blessing was said, and the parsnips were passed. Brother Butler said, “No thanks, I never eat parsnips.” The mother looked helplessly around the table and said, “Well, too bad, Brother Butler, help yourself to the salt and peppa.”[31]

Although this story may have been told to show a bit of humor even in the desperate poverty many early settlers faced, it seems likely that Butler understood that every mouthful of parsnips he ate meant fewer calories for the family members.

Ida Elizabeth McEwen Tompkins

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP Interview

Maiden Name: Ida Elizabeth McEwen

Birth: June 13, 1860; St. Lawrence Co., New York

Parents: George McEwen and Eliza Bohannan

Marriage: George Errath Tompkins;[32] March 25, 1887

Children: Bruce C. (1889), Ruby M. (1890), Amy Ethel (1892), unknown child, Hazel (1897), Dorothy Winifred (1904)[33]

Death: October 15, 1940; Phoenix, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Greenwood Cemetery, Phoenix, Maricopa Co., Arizona

In the early days in the settlement of new places, the school teachers had rather an envied place. Theirs was not to cope with the elements, try to make a home of a wagon box, gather the edible weeds for food, and do many things that the housewife did; they were just to teach the three Rs to the rising generation, keep themselves looking fit, and do the finer things. Then, too, there was always the susceptible cowboy or old bachelor in the town with a desire for higher education, so her life was different.

Ida Elizabeth McEwen was a “school marm,” the second teacher in the Pendergast District in Phoenix, Arizona. She was the daughter of George and Eliza Bohannan McEwen. Her father was born in New York and her mother in Vermont. They were living in St. Lawrence County, New York, when on June 13, 1860, baby Ida was born. She says with a twinkle in her blue eyes, “That’s why I have always been so lucky—because I chose the thirteenth for my birthday.”

Mr. McEwen had sugar trees. In March he would tap them, get the sap, and boil it down into maple sugar and syrup.

Ida started to school when she was five years old but could not go long at a time because in that country the snow drifts would sometimes be twenty-five feet deep. There were eight children in the McEwen family, five of them boys. It was the father’s ambition to have enough land so that they could all have farms around him. To do this he must go farther west. Accordingly, in the spring of 1868, he, with his family and household possessions, took the boat on the St. Lawrence River, twelve miles from their home [at Potsdam].

There was great foreboding in the minds of the relatives and friends left behind, who were sure if the Indians in the west did not kill them, the rattlesnakes would. Their route lay up the river, through three of the Great Lakes to Chicago.[34]

Mr. McEwen engaged two staterooms, but still the family of ten was very crowded.[35] The poor mother with eight children, the eldest fifteen and the youngest a baby six months old, was almost frantic before a landing was made. She had baked up a lot of cakes and cookies before they left home, and Ida says she has never cared for cookies since. The trip was made in a steamboat but was a slow, tedious one at that. The children used to get up in their bunks and look down upon the people below. Nothing escaped eight-year-old Ida. She remembers passing by the Thousand Islands, some of which were made into estates of wealthy people; remembers the contrast between the clear water of the St. Lawrence and the muddy Missouri. She thought they were in fairyland when she saw the first fruit trees, loaded with their pink blossoms.

It was a hard matter to decide on a permanent location, and the family lived at Marion, New London, Shelby County, Missouri, and at Quincy, Illinois.[36]

Their first camping trip took them three days, and what fun it was for the children to sleep out under the stars. Mrs. McEwen did not enjoy it so much; there was always the fear of the fate her friends had predicted.

One place where they stopped her father rented a big, vacant hotel. The children almost drove their parents crazy as they raced through the empty rooms, from the cellar to the attic.

Here was their first experience with colored people, and Rose, who helped Mrs. McEwen with the work, and the little [black children] who would go with the children to gather wild blackberries, raspberries, and other fruit were a constant source of merriment to them. Not so with the poor mother, who was so homesick in this strange land. Her suffering for home and kindred was very pathetic.

Finally, in September, Mr. McEwen found a place that suited him.[37] There were 140 acres of ground. A large orchard loaded with fruit of every kind. This was a treat to the children, and they appreciated their father telling them to make themselves to home. He paid three thousand dollars cash for the place, and added more acreage as the years went by. Some of it was railroad land at $1.25 an acre. A German family had owned the place and remained in part of the house until November. There were four grown daughters in the family, and the little McEwens took their first lessons in lovemaking as they watched these girls and their beaux. You were liable to come upon a couple billing and cooing under the trees at any time.

The orchard provided the family with preserved, pickled, and dried fruit to last a year. Then with the two cows and the chickens the father bought, they were well provided with food.

There was always the problem of clothing and shoes for these eight busy healthy children. The boys picked up enough that they cobbled up for themselves and the other girls, but Ida had to tie her mother’s rubbers on as a protection to her little feet when she went to school. While she was small, she didn’t go very often as it was 2½ miles to the nearest schoolhouse and there were three tall hills to climb. As Ida got older, her desire for an education was so strong that she got work for her board and room near the school. It was hard work, but she studied when she should have slept and finished when she was seventeen.

Mr. McEwen had some fine mares, and he gave each of his children one of the colts. Ida’s colt was five years old by the time she was through school. It was a beautiful horse. She was very fond of him, but by selling him she would have enough to begin college. A neighbor offered her $150 for him. Her father said he would give her that amount. That money, and what she worked for, enabled her to graduate and get a certificate. She began teaching when she was nineteen. She taught three years in Missouri and three in Nebraska.

One of Ida’s brothers had come to Arizona.[38] He wrote his sister the need of school teachers in this territory and that she could get twice the wages she had been getting. The inducement and a desire to see the West were too great, so she came, landing in Phoenix on San Juan Day, June 24, 1885.

After traveling through the beautiful rolling hills, prairies, farms and wooded places in the middle west with water everywhere, she felt she had never seen such desolation. As she traveled along on a slow immigrant train, it seemed she would never get here.

There was always a fear of Indians, so when she awoke one morning in Maricopa Station and saw about twenty-five or thirty Indians in gee-strings with bright red bandanas around their heads, she was about frightened to death. She learned from the conductor that they were army scouts and were peaceable; she was quite relieved. Ida was fortunate in making friends on the train. A light spring wagon was waiting in Maricopa Station to bring them to Phoenix—as the trains did not come any nearer than Maricopa at that time. The trip was made in about six hours.

A happy reunion awaited Ida as she had not seen her brother in about four years. He was employed by Mr. Montgomery, who gave the sister a hearty welcome. The summer was a very pleasant one which Ida enjoyed very much. In order to teach school in Arizona, Ida had to pass an examination.

Arizona was noted for years for its strenuous examinations, and though Ida had taught for six years before coming here, she failed to pass. Nothing daunted, she made preparation to enter school as a pupil that fall. Her brother thought it was a shame, but she told him she could make it all right. She gave one day a week and her time nights and mornings for board and room in the Jor Irvine home, where she was treated as a daughter. The remainder of the time before school started was spent in working in a dress-making and milliner establishment. Here she made $2.50 per week but learned many valuable lessons in these arts.

Prof. D. A. Reed was the teacher to whom she went when school started, and she had no trouble passing the examination the next June. She was promised a school, but through some misunderstanding or otherwise, a man was given the same school. He only lasted until the Christmas holidays, and then she took it, becoming the second teacher in the Pendergast district. There were nine pupils when she began and thirty-five when she finished two years after.

In the first school, there were four children belonging to one family. They had to come four miles to school. The eldest boy of this family told the teacher that his father didn’t want his children taught any newfangled notions. They were not to study geography because he knew the world was flat, and that settled that. Miss Ida said all right. His wishes should be obeyed. The children heard her tell the others how, when a ship was approaching you saw the top of the sails first; they went home and told their father that, and he said it was true. Little by little he became convinced the teacher was right.

Ida thinks diplomacy one of the greatest requisites in teaching a country school. One of the rules she always adhered to was to go to each home before school opened that she might meet, personally, the parents, and learn by observation the environment and background of each pupil—and that the parents might know the teacher and not have to take their children’s account of her. Another thing she never believed much in was punishment, neither in her own home nor in school.

Naturally there were plenty of admirers for the happy, good-looking Irish “school marm” with her ready Irish wit, but young George Tompkins won out over all the others. The Tompkins family came from Texas in 1876 to California. They had with them 3,000 head of cattle. George, then a youth of eighteen, rode horseback all the way. There were eight other children in the family, five girls and three other boys.

Bad luck seemed to attend them, and they lost most of their property before coming to Arizona. Here Mr. [John Givens] Tompkins took up 320 acres of school land in the Cartwright District, and he and the family farmed it. He and George freighted to Globe for a long time.

Ida had invested some of her wages with her brother in land and had 40 acres clear. George tried to persuade Ida to marry and give up schoolteaching, but she enjoyed it so much and took such an interest in her pupils that she insisted on teaching the second year, in fact she taught one month after the funds gave out. She didn’t know whether she would ever get her pay or not, and it didn’t matter; she had some pupils almost ready for high school, and she would see them through. She eventually got the last month’s pay.

She says a girl may make her plans for a career, but when the right man comes along, she changes them. When she came west, Ida brought a lot of yard goods and had her dresses made here. There were excellent dressmakers here at that time. None of these dresses were suitable for the wedding gown, however, so she sent $75 to a friend with whom she had boarded in Omaha to buy the trousseau. There were eighteen yards of 27-inch ottoman silk in the dress, which was made with short pointed basque, overskirt, and puckers.[39] The basque had twenty steel cut buttons down the front that cost $4.50 per dozen. The side panel of the overskirt was covered with cut bead passementerie [or trim]. The little hat, shoes, hose, gloves and purse were a rich cinnamon brown, the color of the dress.

One of the practical neighbor women lamented the extravagance [and] said, “Why that outfit cost you a whole month’s wages. With that amount you could have bought you a good cow.” To which Ida responded, “I expect to have lots of cows in my day, but only one wedding dress, and it shall be one I can always remember with pride,” and it has been as it was, a work of art and a thing of beauty.

Ida and her lover were married on her mother’s wedding anniversary March 25, 1887, in the Old Calvary Baptist Church in Phoenix. The reception was a grand affair and lasted all day and most of the night. There were over 100 guests invited. There was roast turkey and everything that goes with it. Everyone had a good time and wished the happy young couple a long and prosperous life.

George’s father had a homestead of eighty acres at Agua Caliente and to this went the bride and groom. She drove two old mules and a spring wagon; she held a parasol over her head for shade. She followed the plow and sowed the first grain down there, carrying it in her apron.

Her experiences as a farmer’s wife were very strenuous ones. At harvest time, she would cook four meals a day for the men, always from eight to twelve of them. Seventy-five to a hundred pounds of flour were cooked by her each week—this, with the other food, was no small amount of work. During this time, she was also having her six children and rearing them.

Ida’s father had always regretted she was not a boy and used proudly to call her “Pine knot” because she never flinched. That characteristic has come with her through life, and she never complained until she had a complete breakdown.[40] It took her five years to recover from it, but she has and enjoys wonderful health today.

After her marriage, her father planned to bring the remainder of the family and come to Arizona, but he sickened and died before these plans could be carried out. Her mother and sister came and visited her shortly after his death.[41]

Ida had a month of real pioneering when she took her mother-in-law up to Castle Hot Springs to take baths for her rheumatism.[42] During this time, she lived in a tent and cooked over a campfire. Mrs. Tompkins could not get to the springs, so a hole was dug and she sat in it and the hot water was poured in around her.

That was a month Ida remembers vividly, though not with regrets as the dear old lady was benefited by the baths. Ida was ever a devoted daughter to her husband’s parents, especially kind to his invalid mother. “How could I have been otherwise,” she laughingly asks, “when they all took me into the family-in-law and out-laws?”

Of her own mother, she has only the pleasantest memories, and one of her most prized possessions is a letter her mother began to her the day before her death and never lived to complete it.

She says her mother was a born nurse and that all of her children learned the medicinal herbs, roots, and plants as they gathered them for her to dry and use in the care of her own family and those of her neighbors.

Overnight her mother’s black hair became streaked with grey when her husband went to be examined for a soldier in the Civil War. She was very ill at the time, having a tiny baby only a few days old. She had two brothers who were then incarcerated in Libby Prison, and she had heard of the inhuman treatment they were receiving.[43] That and her anxiety about her husband in her already weakened condition almost cost her her life, and left the visible signs of her suffering in her whitened hair.

As is fitting after a life full of service to others, beautiful memories gladden the declining days of Ida McEwen Tompkins. However, she doesn’t live in memory alone. She still takes an active interest in all about her. She belongs to several clubs and takes part in them and her church. She lives very happily in her own home surrounded by friends, neighbors, and family.

On March 26, 1929, George Tompkins died. In 1930, Ida had her youngest daughter, Dorothy, living with her; in 1940, Ida was living by herself. Ida died October 15, 1940, when she was eighty years old.[44]

Ellis and Boone:

Ida Tompkins gave birth to her last child, Dorothy, on October 2, 1904 at age forty-five, seven years after her last child.[45] She may have suffered from postpartum depression because she was nervous and sleepless. Her husband also cited “lactation and debility” as further proof of insanity and committed her to the Arizona Territorial Asylum for the Insane on May 11, 1905.[46] Although many other women languished or died at the asylum, Ida was living with the family again at Cartwright by 1910.[47] Superintendent Miller in 1900 thought that “insanity in women is commonly caused by pelvic diseases which may be remedied by surgical means,” presumably meaning that he thought insanity in women was caused by hormonal problems.[48]

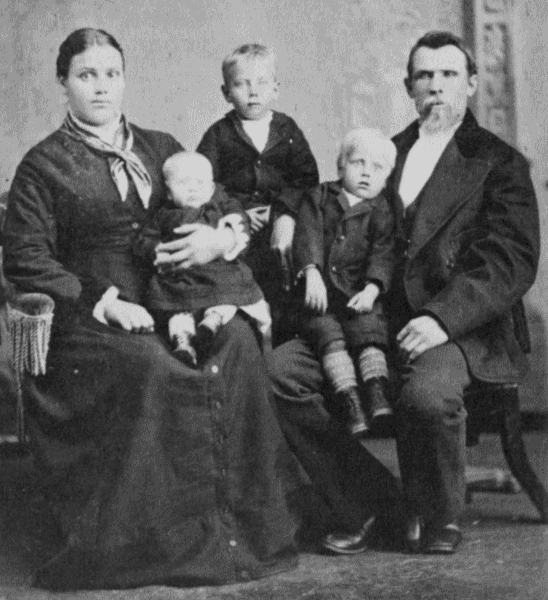

No photograph of Ida Elizabeth McEwen Tompkins was located, but this postcard shows the Arizona State Asylum for the Insane and was mailed in 1909 with an ambiguous message. Photo courtesy of Ellis Collection.

No photograph of Ida Elizabeth McEwen Tompkins was located, but this postcard shows the Arizona State Asylum for the Insane and was mailed in 1909 with an ambiguous message. Photo courtesy of Ellis Collection.

From the beginning, mental health care of Arizonans was probably not much better or worse than such care in other states. During the early territorial period, those declared insane were housed in Stockton, California. In 1885, the Thirteenth Territorial Legislature awarded the capitol to Prescott, the prison to Yuma, a teachers college to Tempe, the university to Tucson, and the mental health hospital (designated Insane Asylum of Arizona) to Phoenix. By 1887, “the patients were brought back to the Territory and the Asylum was finally functioning well, under the guidance of Doctor I. S. Titus.”[49] Problems at the asylum during the territorial period included inadequate buildings, commitment of criminals rather than just the insane, and inadequate records (including some patients entirely unaccounted for, no death records for some patients known to have died, and patients reportedly discharged when they really escaped).

However, the biggest difficulty was the diverse nature of mental health problems for those committed. In 1883, patients were classified as suffering from dementia, mania, melancholia, and paresis. By 1889, a list of the causes of insanity included alcoholism, apoplexy, brain disease, confinement, domestic trouble, epilepsy, exposure, fright, heredity, immorality, injury to head, lightning stroke, meningitis, menopause, drug addiction, religion, tuberculosis, syphilis, want of work, and worry. In 1900, most of the patients were men (seventy-three men and ten women). Often the treatment simply included “employment and amusement,” meaning “complete mental rest and mild physical employment.”[50] Occasionally, a dying person was committed; Dr. Miller wrote that “several patients in a dying condition have been sent to the asylum, their delirium being mistaken for insanity.”[51]

As noted here, Ida Tompkins spent some time at the Territorial Insane Asylum. Latter-day Saints also occasionally used the facility, although Miller noted that residents of outlying counties (such as Apache and Graham) used the asylum much less than those who lived close by. Aaron Adair died at the facility in 1911 after having been there for twenty-nine years.[52] Samuel Lewis of Thatcher (and formerly the Mormon Battalion) was committed to the asylum July 23, 1911, and died there six weeks later on September 1; he died of exhaustion (with a contributing condition of senile debility) and was buried at Thatcher.[53] Karl Bushman of Snowflake began living there when his caregivers, brother Degan and sister-in-law Phoebe Bushman, wanted to go on a mission about 1956.[54]

As Adeline Rosenberg wrote in 1962, “Mental illness has existed since the history of man. No chapter in the history of man’s inhumanity to man is darker tha[n] that concerned with the treatment accorded those suffering from mental illness.”[55] In 1956, Ron Silverman wrote a series of thirty-nine articles for the Arizona Republic which won the Mental Health Bell Award, a national award from the National Association for Mental Health.[56] These articles highlighted problems and suggested solutions for the Arizona State Hospital, as it was then called. By 1962, when the facility celebrated its seventy-five years of history, a more positive report was written for mental health care in Arizona.[57]

Delilah Jane Willis Turley

Autobiography/

Maiden Name: Delilah Jane Willis

Birth: June 28, 1871; Virgin City, Washington Co., Utah

Parents: William Wesley Willis Jr.[58] and Gabrilla Stratton[59]

Marriage: Alma Rueben Turley; November 3, 1888

Children: Hazel (1890), Isaac Wesley (1892), Rhoda (1893), Sarah (1895), Josephine (1898), Charles Herman (1899), Tillman Willis (1902), Leora (1904), twins Alma and Delilah (1907), Wallace Mar (1909), Martha (1911), Joseph Chester (1913)

Death: September 26, 1946; Woodruff, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Woodruff, Navajo Co., Arizona

I know but very little of my ancestors, only that they were of a religious nature. Their nationality was American as far back as we have any record. Most all favored the Republican platform and were very loyal to this country and its laws. The greater part of them followed agricultural lives.

My birthplace was in a little southern town in Utah—Virgin City. My parents, William W. Willis and Gabrilla Stratton, moved to Arizona when I was six years of age, settling in Brigham City, where the United Order was carried out. They lived there one winter, then the family moved to the Tonto Basin with my father’s brother John H. Willis Sr.[60] They stayed there during the summer, then they moved back to Johnson, Utah; lived there one year and returned to Arizona, settling in Snowflake, traveling with William J. Flake and his wife Lucy when they were driving their cattle out, overtaking Uncle Paul Smith and his wife Jemima, who were waiting at the Colorado River for company.

Delilah Jane Willis Turley. Photo courtesy of Erlene Kartchner Plumb.

Delilah Jane Willis Turley. Photo courtesy of Erlene Kartchner Plumb.

The second day out after crossing the Big Colorado River, our wagon tipped upside down. I, being the only one in the wagon, all the company thought I was killed but was taken out unharmed in any way. I resided in Snowflake during the rest of my childhood days. Was married the fall of 1888 to Alma R. Turley, living in Snowflake until the spring of 1900.[61] Six of our children were born there. We then moved to Woodruff, Arizona, a small settlement on the Little Colorado River, which is still my home. Have had many hardships and trials, through the dams going out, depriving us of raising our crops. Through it all I have enjoyed working in the Sunday School, being a teacher over different classes for several years, also the Relief Society, working in it from the time I was a small girl until the present time of writing, as a teacher, first and second counselor, and president. Was counselor and president fourteen years from 1908 to 1922.

My religion and trials are what have influenced my life more than any other thing as it has been my desire to serve the Lord, do what little I could for the good of my associates and family. Have tried to raise my children up to be good citizens and Church members; to cherish the gospel, that the world would be better for their living in it. My husband and I have quite a numerous posterity—five daughters, four sons, fifty-three grandchildren, four great-grandchildren.[62] They are our treasures and blessings.

Ellis and Boone:

RFC submitted a biographical sketch for Delilah Willis Turley to the FWP on November 16, 1937 (written in third person). The first four paragraphs of the FWP sketch provide the same information as Delilah’s first person account above. The following is the remainder of the FWP submission:

From her early childhood, Delilah began taking on responsibility and was very dependable at home or wherever she went, and in the organization to which she afterward belonged. She was given every advantage for an education that the pioneer town afforded. From an early age she was a teacher in the Sunday School, and was a Choir member from the time she was seventeen until she was fifty-five years old. She had a soprano voice of unusual clearness and volume. She has been especially active in the Relief Society, beginning in her childhood by doing errands or caring for the children while their mothers made quilts or rugs, sewing carpet rags, until she has filled every position in the Society except that of secretary. Punctuality and dependability have been two of her slogans.

In her young womanhood, she shared in the pleasures incident to those early days. Since her father was an excellent molasses maker, and kept molasses for his toll [payment] in making it for the neighbors. Delilah was always ready to furnish molasses for the candy pullings; yes, and there was always plenty of sweet corn for the parched corn that went so good with the homemade candy. Many of these festive occasions were held in her home. She was very popular with both boys and girls and shared with them the attentions of all the young lovers of the town. Finally she settled on one, Alma R. Turley, and in the autumn of 1888, they were married.

Their first home was in Snowflake and six of their thirteen children were born there. Then they moved to Woodruff, Arizona where they still reside.

Delilah Jane Willis Turley. Photo courtesy of Erlene Kartchner Plumb.

Delilah Jane Willis Turley. Photo courtesy of Erlene Kartchner Plumb.

Like the other settlers in that little town, they have endured many hardships in trying to maintain themselves there. They have assisted in building dams there only to see them washed out by the spring floods for which the treacherous Little Colorado is famous. Then there would be no crops or gardens, due to drought, and the men folks would have to go away from home to earn a livelihood, leaving the responsibility, care, and work of raising the family and making the meager wages cover the needs. The strictest economy had to be practiced, and everything that could be used was put to use. What they could not afford, the Turleys did without. However, they found the means necessary to send eight of their children to Snowflake to the Union High School, four of whom graduated from the four year course, and all are honorable men and women, and a credit to their sacrificing parents and the community where they live.[63] The remaining children died in early childhood, a pair of twins, a boy and girl, only lived a few hours.

At the time the Americans were driven out of Mexico, two of Alma’s brothers and their families came to Woodruff, and were welcomed into the home of their brother, and for a while Delilah had the responsibility of cooking and caring for twenty in the family until they could find suitable homes to move into. One brother, whose wife had died, left his family with Delilah for several months while he was away at work.[64] Through all these times she gladly did her part, uncomplainingly, glad to be of service.

Time has been very good to her. Her health has been exceptionally good. There have been no doctor bills to pay, and her active life has kept her youthful, and given her a keen interest in the things that are going along about her.

Her spirituality is reflected in the lives of her children, who honor her, and do their best that her remaining years may be many and filled with happiness.[65]

Delilah Jane Willis Turley died on September 26, 1946, in Woodruff and is buried in the little desert cemetery just outside of town.

Mary Agnes Flake Turley

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP

Maiden Name: Mary Agnes Flake

Birth: February 16, 1866; Beaver, Beaver Co., Utah

Parents: William J. Flake[66] and Lucy Hannah White[67]

Marriage: Theodore Wilford Turley;[68] November 1, 1882

Children: James Theodore (1883), Pearl (1885), Sarah (1886), Lucy (1888), Ormus Flake (1890), Lowell Barr (1892), Frederick Andrew (1895), Roberta, (1898), twins Harry William and Harvey Isaac (1905)

Death: December 19, 1909; Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Mary Agnes Flake was born February 16, 1866, in Beaver City, Utah, the fifth child and first daughter of William Jordan and Lucy Hannah White Flake, and named her for her two grandmothers, Mary and Agnes. Her father was a full-fledged Southerner and her mother a dyed-in-the-wool Yankee, so to preserve peace, the War Between the States was never discussed in their home.

Mary’s summers were mostly spent on one or another of her father’s ranches, and as soon as she was old enough, she did her part in milking cows, making butter and cheese, assisting with the housework and the younger brothers and sisters, as she was one of thirteen children. . . .

She also learned to ride and to drive a team; this knowledge and love of horses stood her in good stead, for when she was eleven years old, her father moved his family to Arizona. The boys and five hired men were needed to drive the cattle, so Mary became one of the teamsters and drove over some of the most terrible places that were ever called roads. When coming over “Lee’s Backbone,” her wagon was directly behind her father’s. He heard her call “Whoa” to her horses, and looking back he saw that she had been pulled from her wagon and was clinging to the brake. He stopped his team to go to her rescue, but she shouted, “I’m all right, Father, go on!”

For this trip her father got her some high-topped boots, just like the ones he had for her brothers. Her mother seriously objected to having her daughter’s feet thus shod, but the father was vindicated when the snow became so deep it almost came to the tops of the boots.

The winter was bitter cold, and though everything was done for the comfort of the family that could be, the suffering was very great. To add to the seriousness of the situation, Mary and her sister Jane both took diphtheria. The mother had never seen a case of it before, and but for the services of a dear old blind nurse, both girls might have died and other members of the family as well.[69]

In December, the family reached the settlements on the Little Colorado River. Here they remained until July 1878, when her father, William J. Flake, bought the Stinson Ranch on Silver Creek. The family was very delighted to move there.

That September, and the succeeding fall, her father had to go to Beaver City on business and took his family with him. These trips were not as hard as the first one, and Mary enjoyed meeting her friends and relatives. Whenever it was necessary she assisted with the driving, as well as the cooking and other camp work. Being large and strong for her age and a willing worker, her father often said she did more than any two of his hired men.

During one of these trips, they had a traveling companion, Isaac Turley, and his family. Under no other circumstances do people become so well acquainted as traveling together. The oldest son, young Theodore, had known Mary during their school days in Beaver, and after making that long journey, he decided when they were old enough he would make her his wife. Mary had known many beaus; one . . . that she had never could tear himself away. After saying goodbye several times he would finally depart. On one of these occasions Mary got his hat and handed it to him saying, “Here’s your hat, what’s your hurry?”[70] He never came back. But Theodore wouldn’t be so easily discouraged, so before she was seventeen they were married. Their honeymoon was spent on a trip back to the St. George Temple, where they were married for time and eternity. This was the fifth trip Mary had made over this road by team and wagon. They made it in twenty-one days, which was the shortest time they had ever made going one way.

Their married life began under very humble circumstances, but youth, health, and love find a way, and both were ambitious. Soon a comfortable, two-room log house was built on a large lot on Main Street, given Mary by her father.[71] Here they lived in peace and happiness, until many years later when they built a large brick home.

Before they had been married long, her husband’s mother died, and seven of his brothers came to live with them.[72] The two eldest stayed until they were married, and the others remained for several years until they joined their father and his second wife in Mexico. After Mary’s mother died in 1900, Mary was the comfort and solace to her father and two unmarried brothers, and when her widowed sister came home and brought her one child, “Molly’s” home was hers.[73] No person was ever turned from her door, and her home became a haven to anyone in distress.

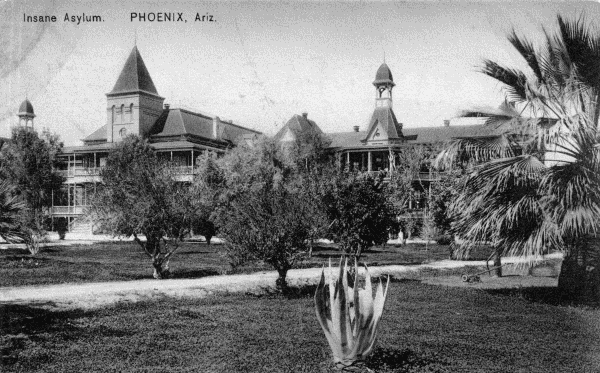

Wedding photograph of Theodore Turley and Mary Flake, 1882. Photo courtesy of Wanda Turley Smith.

Wedding photograph of Theodore Turley and Mary Flake, 1882. Photo courtesy of Wanda Turley Smith.

In the early days, when Flake Brothers had the U.S. mail contract from Holbrook to Fort Apache, the mail was conveyed in buckboards. “Fool’s Holler” (or Adair as it was called by the more discriminating of its few residents) was the night station for the mails going both ways. It was the most important station en route and needed someone with business ability to look after it. Theodore and Mary were the ones who were given the responsibility. Not only did they furnish meals and beds for the drivers and passengers, look after the teams, and keep the conveyances in repair, but they kept a store to supply the employees, the inhabitants for miles around, and the Apache Indians who brought in their wild game, corn, and beans to trade for supplies. One time a trusted young Apache, who had been away at school, got into debt to them, but his intentions were good as he wrote: “Just as soon as I thrash my beans and corn I will pay you,” and he did.

The station became the gathering place for all the neighbors, and their home served as the church and dance hall. Many times during the deep snows, folks would gather in and eat, dance, and visit for two or three days at a time. There was always plenty of wood, plenty of food, and a warm welcome at the Turley home, and it was seldom that the family ever sat down to a meal or spent an evening alone. Mary was so full of fun and good humor that when her home was crowded to “capacity,” she would laughingly say, “The more the merrier,” and “There’s always room for one more.”

After about two years spent at the mail station, Mary and her husband moved home. She had proved so valuable to her brothers that when there was a rush of work at the store, or their duties called them elsewhere, they would call across the street to “Molly,” and she was never too busy to help them or anyone else in need. If there was sickness or death, a wedding, birth, or celebration, she was sought after and was ready to go with the one thought in her mind, aside from service to others, that she must be at the gate to welcome her husband when he returned from work. One of his trades was that of blacksmith, and Mary would take her sewing, knitting, or mending and sit near while he worked, or if it came to setting a tire, she was his helper.

In 1896 he was called on a mission to the Southern States. He traveled without “purse or scrip,” in the ten months he was gone. He spent 75 cents buying crackers and cheese when they got too hungry. They were hungry often and had to sleep on the wet ground with only an umbrella to cover them. He became ill with chills and fever [i.e., malaria] and had to return home.

During all their married life, Theodore and Mary were “pals” and understood each other perfectly. There were no quarrels or fault finding; happiness and love reigned within their home. They were blessed with ten children; two of them died in early childhood. The last two were twins, strong husky boys, who were the pride of the family.

Theodore decided to homestead at what is now Aripine and go into the cattle business. He bought some of the surrounding ranches and brands, and they were very well fixed.[74] Mary enjoyed this very much and called their place “Sundown Ranch” from the glorious sunsets so visible from there.

Mary was an ardent church worker, holding many responsible positions in the organizations. She was never known to speak evil of anyone, but could always be depended upon to know and tell plenty of good about everyone.

On December 19, 1909, she passed away and was buried in the cemetery of the little town she helped to found and to which she gave all she had. She endeared herself to young and old alike, and all who knew and loved her. To her father she was the sum of perfection; to him she could always do everything better than anyone else.[75]

Although only forty-three years of age, she had lived every minute of it to the fullest, and her memory is revered by all who knew her.

TO MY MOTHER

A tribute from her daughter Mrs. Lucy T. Bates

Gracious, charming, tender, true—

Those are things I love in you.

Loving, laughing, calm and kind,

My ideal in you I find.

Peace you carried in your heart,

Always ready to impart

Strength to others, till it seems

You’d bring courage, hope and dreams.

Mem’ries of you are a shrine

Burning in this heart of mine,

Till its gleaming, golden light

Guides me safely through the night.

And at last, ‘tis this I pray,

Striving, yearning day by day,

Somehow, somewhere may I be

Nearer your nobility.

Ellis and Boone:

RFC submitted this sketch to the FWP and then moved it into PWA with few changes. This version has been highly edited, mostly at the suggestion of a granddaughter, Wanda Turley Smith. She requested that the first three paragraphs of the PWA account (which contained no information about Mary) be deleted and the following be included. The first section is from a sketch Lucy Turley Bates wrote about her mother in 1979.

No person was ever turned from her door, and her home became a haven to anyone in distress. I still have a picture in my mind of Indians sleeping on the floor of our store. Father and Mother ran a trading post at Fools Hollow for the mail and Indian trade which was owned by Uncle Jim and Uncle Charley Flake. This was near Show Low, Arizona.

When Aunt Nancy died, mother helped Uncle Jim and his large family any way she could [in Snowflake].[76] She sewed, cooked, and helped many ways. At Conference time when she had to cook for so many, mother made cakes, pies, etc. for each family (Uncle Jim’s and hers). I remember she used a three pound lard can for a measuring cup. She mixed it in a large pan, then made white cake, spice cake, jelly cake and all kinds, besides pies and rice pudding, enough for the Conference. We had a Conference every three months for three days which made so many people to feed. [We had] no cars then, [only] teams and wagons, so they came and stayed three days, even people in Taylor and Shumway. When the Choir started to sing the closing song of the morning sessions, Pearl and I were to leave to go home and start the fire in the wood cook stove, begin warming or cooking the food, set the table and prepare for company.

Father would stand at one door of the church and Mother at the other door and invite anyone who hadn’t been invited to other homes. We would have from twenty-five to thirty to feed and get back by 2 o’clock for another meeting. . . .

Father being of the same generous nature as Mother, their home was soon known as a mecca for those in need, and a general stopping place for the travelers. We children cannot remember ever sitting down to eat without someone besides the family being there. She was able to do the work of two women and did it without complaint.

When Father went on a Mission, all we children were down with measles. For breakfast the morning he left, Mother used the last flour she had. For the next six weeks, we didn’t have a bit of flour in the house. No one knew we didn’t have bread, but she worked hard for some wheat and in ten months when Father came from his Mission (he had chills and fever and had to come home), she had the foundation all laid for adding two rooms to the house, also the brick paid for. She wove carpets for people and did anything she could for a little money.

My mother . . . was especially kind to the boys who were not so active in Church and people thought they were the rough kind. She kept boarders and boys of this kind who were good boys at heart but were looked on as not so good. . . .

The day she died [December 19, 1909], Grandfather Flake sat by the window with a book in his hands. He said, ‘Why don’t you children get a book and take your mind off things by reading?’ but we noticed he sat with the book upside down and never turned a page. Mother, to her father, was the sum of perfection. To him, she could always do everything better than anyone else.[77]

On November 15, 1978, Mary’s son Fred A. Turley also decided to write about his mother, some of which is quoted here:

One of the remarkable things, to me, her son, was that the week I was born she wove one hundred ten yards of carpet on the large, quite modern, loom in the little house back of our home. During my early youth, this loom seemed to be the greatest machinery ever manufactured. A push and a pull sent the cylinder racing across with another string of rags. The warp was filled into uprights [the weft or woof which was usually cotton strings] that changed places every time it was pulled. The change was wonderful to me, as I was the one to keep the cylinders filled with the balls of rags. A number of rag parties were held in our home, with the teenage young people of Snowflake. Winter was ice cream season in our town. The ditches froze over in the cold weather making ice, so we could have that wonderful treat.

Mother also liked fishing trips in the White Mountains in the summer time. The teenage boys and girls would ride horseback and the women and children in buggies or wagons. These trips were of about ten days in length. In those days, Charley Cooley lived on his father’s ranch high in the mountains where they raised cattle [which were] real fat about the middle of July. He always came and butchered a fine yearling heifer. Mother always claimed this to be the best beef she ever ate.

Also, she was the only woman I knew who made pleasure out of freight trips. Freighting for the government installation in Fort Apache was the most lucrative possibility in the early days of Snowflake. Mother took a buggy and us kids along for the week trip from Snowflake to deliver this freight. She would go along with the teams until near camping time, then go ahead and make the camping spot for night and have supper ready by the time the wagons got there.[78]

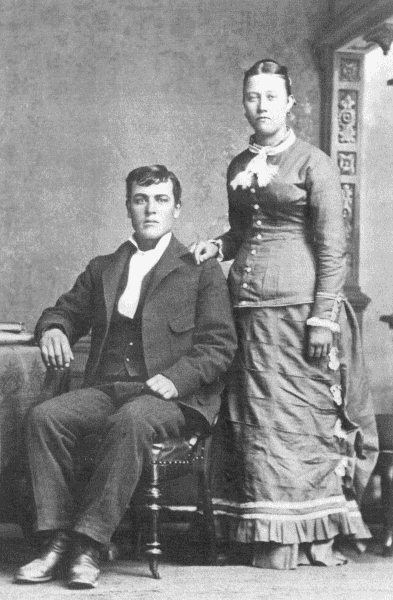

Mary Turley with her twins, c. 1905. Photo courtesy of Wanda Turley Smith.

Mary Turley with her twins, c. 1905. Photo courtesy of Wanda Turley Smith.

In 1908 Father decided to take up a homestead out on the Decker Wash southwest from Snowflake. His first priority was a place with a real permanent water well on it. Many homesteaders had taken homesteads where they had to haul drinking water. We went out there and lived through the summer and dug three wells which had water all season. So the place was homesteaded, and Mother named it Sundown Ranch, because all work was to be over by sundown. . . .

Mother’s death was one of the most beautiful experiences of my life. She said, ‘I do not wish to live and suffer as they usually do with cancer.’ One evening she said, ‘My time is soon up. I wish to speak with each of my children alone.’ That evening, Pearl, Lucy, Ormus, and Barr each spent about thirty minutes with her. The next evening myself, Roberta, Harvey, and Harry had the fine visit with Mother who was nearly free from pain. The next morning Mother said, ‘Well, this is my last day. They are coming for me.’ Besides the family, Uncle Jim and Aunt Belle were present.[79] All seemed to be pleasant while spending several minutes in just family conversation. Suddenly Mother looked directly up into the corner of the room and said, ‘They are coming for me. Jim, I will be seeing Nancy in just a few minutes. Please give me a special message for her. I can tell all about you and the family but just a personal message from you.’ Uncle Jim knelt down by the bed and spent a few seconds whispering to her. Then she said, ‘Belle, give me a message for Charley.’[80] Aunt Belle spent a short time in real confidence, then Mother looked again at the corner of the room and said, ‘Here they are for me. You children each kiss me.’ This we did, then Father knelt beside her whispering for a few seconds. Mother said, ‘Good-bye Darling. I’ll be waiting for you.’ She just smiled and without a gasp or a struggle stopped breathing.[81]

Sarah Ann Salina Smithson Turley

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP

Maiden Name: Sarah Ann Salina Smithson

Birth: October 13, 1870; Kanosh, Millard Co., Utah

Parents: James Daniel Smithson and Elizabeth Louisa Dorrity

Marriage: Theodore Wilford Turley; May 31, 1911

Children: Nina (1912)

Death: January 1, 1952;[82] Snowflake, Navajo, Arizona

Burial: Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Pioneering necessitated the doing of many unusual tasks by the women and children but probably none of them can lay claim to having “freighted” with the possible exception of the subject of this story.[83] Salina, as she was familiarly called, was the third in a family of thirteen and, when her services could be dispensed with at home, often went with her father from Holbrook to Fort Apache driving her four- or six-horse team with as great ease and skill as her father or older brother.

Coming as she did from pioneer ancestors, her grandfather and grandmother Smithson both having emigrated to Utah from the South, and her grandparents on her mother’s side having pulled or pushed their handcart from the Missouri River to Salt Lake Valley and then moving from place to place in the colonization scheme of the West, inherited a disposition to make the best of things and do her part.[84] Not a manger but something even more humble, a “dugout” was the birthplace of Salina in a little settlement called Kanosh in Millard County, Utah. She was the daughter of James Daniel and Elizabeth L. Dorrity Smithson. She was born October 13, 1870.