S

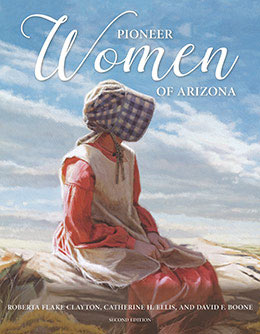

Elmina Sanders Power, Edith Pearl Openshaw, Roberta Flake Clayton, Phoebe Earston Johnson Scott, Thomas H. Shelley, Marie Shelley Webb, Wright P. Shill, Maria Annanettie Hatch Shumway, Blanche Shumwau Hansen, Effa Skousen Duke, Annise Adelia Bybee Robinson Skousen, Ellen Johanna Larson Smith, Leah Smith Udall, Henry Lunt Smith, Thyrle H. Stapley, Ethel H. Stewart Russell, and Artemesia Stratton Willis, "S," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 621-708.

Amanda Armstrong Faucett Sanders

Elmina Sanders Power

Maiden Name: Amanda Armstrong Faucett

Birth: May 6, 1810; West Columbia, Maury Co., Tennessee

Parents: Richard Faucett and Mary McKee

Marriage: Moses Martin Sanders; January 12, 1826

Children: William Carl (1826), Richard Twiggs (1828), John Franklin (1830), Rebecca Ann (1832), Martha Brown (1833), David Walker (1835), Joseph Moroni (1836), Sidney Rigdon (1839), Emma (1841), Eliza Jane (1843), twins Hyrum Smith and Moses Martin (1845), Moses Martin Jr. (1853)

Death: April 24, 1885; Gisela, Gila Co., Arizona

Burial: Gisela, Gila Co., Arizona

Amanda Armstrong Faucett was the daughter of Richard Faucett and Mary McKee. She was born May 6, 1810, in West Columbia, Maury County, Tennessee.

She was the ninth child in a family of fourteen children. She spent her girlhood days in Tennessee. She married Moses Martin Sanders, January 12, 1826. He was the son of David Sanders and Mary Allred, and he was born in Franklin County, Tennessee.

Amanda’s first two boys were born in Maury County, Tennessee. They were William Carl and Richard Twiggs Sanders. William Carl died before he was a year old.

Amanda and her husband moved to Montgomery, Kane County, Illinois. They lived in Illinois several years, and four of their children were born there. They were John Franklin, Rebecca Ann, Martha Brown, and David Walker Sanders.

Amanda and her husband Moses Martin Sanders moved to Far West, Caldwell County, Missouri. They became members of the Mormon Church in 1835. While they lived in Far West, Missouri, another son was born. He was named Joseph Moroni Sanders.

The Saints were driven from Missouri, and the Sanders family moved to Nauvoo, Hancock County, Illinois. Four more children were born in Nauvoo. They were named Sidney Rigdon, Emma, Eliza Jane, and Hyrum Smith Sanders. Their son, Sidney Rigdon Sanders, died in Nauvoo age six years. Their daughter Eliza Jane and their son Hyrum Smith died while on the trek across the plains to Utah.[1]

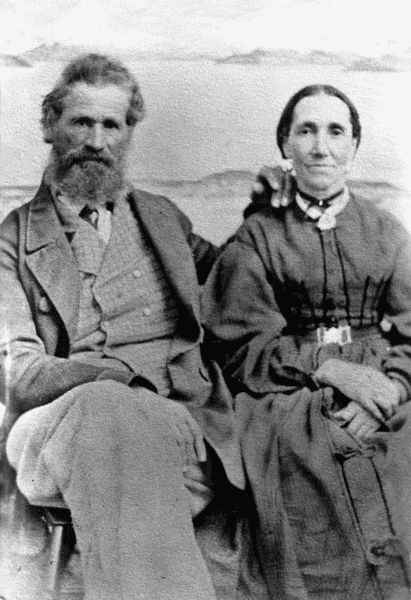

Amanda Armstrong Faucett Sanders. Photo courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

Amanda Armstrong Faucett Sanders. Photo courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

While they lived in Nauvoo, Amanda’s husband Moses Martin worked on the temple. He had a good home for his family and other property. While the mobs were making so much trouble, he and his eldest son, Richard, were with other men trying to drive the mobs off, and his son John Franklin was at home with his mother and the younger children trying to protect them and their home. They were driven from Nauvoo in February 1846.

The Sanders family farmed, raised cattle, and hauled freight for several years. They lived in Cottonwood, Salt Lake County, Utah. (They crossed the plains and arrived in Utah in 1849–50).[2] Their last child, Moses Martin Jr. was born in Utah County in 1853.

Amanda’s husband was called by President Brigham Young to go to St. George and work on the temple. They had a good home there, and Amanda enjoyed having her grandchildren come to her home to play. Her husband died in St. George, November 9, 1878.

Her sons had a large herd of cattle, and President Brigham Young advised them to try to find a better range for them in Arizona. It took a few years to get moved. They rounded up the cattle, and Amanda’s grandson John Franklin Jr. and Mr. Hansen drove them to Arizona. It was a long, hard cattle drive.

They found a range on Tonto Creek, near Payson, Gila County, Arizona. John Franklin Jr. went back to Utah where his wife and child were waiting for him, and other Sanders families were in St. George getting wagons, horses, and other things ready for the move to Arizona.[3] While in St. George, they went to the temple where they received their endowments and did sealings and baptisms for their kindred dead.

Early in the spring of 1882, Amanda, with her sons and grandson and their families, left St. George in their covered wagons to make new homes in Arizona. It was a good trip; sometimes they would camp two or three days, while some of the men would find work. It took them about three months to reach their destination on Tonto Creek.[4]

They began to build lumber houses, plant fruit trees, shade trees, and plant gardens. The lumber came from sawmills around Payson and Pine, and some of their trees and seeds came from settlements in the Salt River Valley.

Amanda enjoyed her own little home; she wasn’t very well and seldom left her house. She enjoyed having grandchildren and little great-grandchildren come to visit her. She had many years of worry and sorrow during the time of the persecutions of the Saints and on the trek across the plains. After living in Tonto Basin a few years, she became ill and died in her home April 24, 1885. The settlement is now called Gisela and she is buried in the little cemetery there.

Ellis and Boone:

Moses Martin Sanders traveled to the Salt Lake Valley in 1849 as part of the Allen Taylor Company, one year before the rest of his family.[5] Amanda and her children John Franklin, nineteen; Rebecca Ann, eighteen (married to Henry Weeks Sanderson); Joseph Moroni, twelve; and Emma, nine, were part of the Warren Foote Company of 1850. This company suffered several deaths from cholera before they reached Laramie, Wyoming. Not mentioned in the MPOT database are Eliza Jane and Hyrum Smith Sanders because, contrary to the information in this sketch, both died before the family left Council Bluffs (Eliza died April 4, 1847, and Hyrum died September 27, 1846). The database includes a “trail excerpt” by Henry Weeks Sanderson.[6] Sanderson traveled ahead and wrote, “I arrived at Father Sanders place 12 miles South of Salt Lake City on Jordan river & he went & met the Company.” Moses Martin Sanders and Henry Weeks Sanderson were also part of the 1856 Rescue Companies that traveled east to help the stranded handcart pioneers.

As noted in this sketch, Amanda Sanders lived in Arizona only three short years and is buried in Gisela. Most of her life had been spent moving with other members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—from Missouri to Illinois to Utah and then to Arizona.

Hannah Elmina Allred Sanders

Edith Pearl Openshaw

Maiden Name: Hannah Elmina Allred

Birth: February 20, 1862; Mt. Pleasant, Sanpete Co., Utah

Parents: William Alma Allred and Almira White Aldrich

Marriage: John Franklin Sanders Jr.;[7] August 31, 1879

Children: Myra Irene (1880), Franklin Alma (1882), Lafayette (1884), Elmina (1886), Perry Ray (1889), Minerva (1891), John Lester (1893),[8] Carrie (1895), Edith Pearl (1898), Jessie Grace (1900), Laura (1902)

Death: September 29, 1949; Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Hannah Elmina Allred was born February 20, 1862, in Mt. Pleasant, Utah. She was the fourth child of William Alma Allred and Almira White Aldrich.

Her parents, as young teenagers in Nauvoo, witnessed the mobbings and trials of the Mormons there. Their parents [Hannah’s grandparents] joined the Church soon after its organization and were with the Saints in Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois. They suffered many tribulations, but through it all they remained “true to the faith.” Her paternal grandparents are Isaac Allred and Julia Ann Taylor; the maternal grandparents are Levi Aldrich and Louisa Wing. With the exception of Levi Aldrich (he passed away before the westward trek), they all crossed the plains and settled in the Rocky Mountains.[9]

They didn’t enter the valley until after the return of the Mormon Battalion. It was at the request of Brigham Young that they stopped at Council Bluffs and helped raise food for the Mormons who would be crossing the plains at a later date.[10]

Hannah’s parents were married at Kaysville, Utah. Their first child was born there. Then they lived in Ogden, where the next two children were born. About 1860 they moved to Mt. Pleasant where Hannah was born. Before her birth, they went to the Endowment House in Salt Lake City and were married for time and eternity. Thus Hannah was born “in the covenant.” The trip to the Endowment House was made March 9, 1858.

When Hannah was about two years of age, her parents moved to Circleville. Everything looked so promising there, plenty of water and good fertile soil. Crops were planted and had grown to maturity. It looked like there would be a good harvest. The fields were waving with wheat, soon to be cut and thrashed. Then came the Indians. Their order was “Get out or be killed.” They hurriedly gathered their household possessions together, and driving their livestock, they started northward and settled in Fairview. Although only a little over three years of age, Hannah vividly remembered the trip and her fear of the Indians. She said her mother drove the oxen team that was attached to the wagon that held all their household possessions. Her father, riding horseback, drove the cattle.

The rest of her girlhood days were spent in Fairview. It was there she learned to love and care for flowers. Their yard always had an abundance of old-fashioned flowers that were shared with admiring friends. Irene Watson who started the “Watson’s Flower Shop,” in Mesa, Arizona, said she got the inspiration for having a flower shop from Grandmother Allred’s garden of flowers.

Hannah was always very industrious and learned to card, weave, knit, and crochet; she made candles, learned to bake, and sewed beautifully. She also learned the millinery trade and at one time made the remark, “If the Mormons had stayed on with the ‘United Order,’ they would have all been wealthy.” She also had fun. Sleighing was such a good winter sport. They would arise early on Christmas morning, get in the sleigh, and go to visit friends and relatives and wish them “Merry Christmas.”

Hannah was a beautiful young lady, tall and graceful. At the age of sixteen she was chosen to be “Queen of the May.” At this time the May pole was braided by the young dancers. It was a very important event, enjoyed by old and young alike.

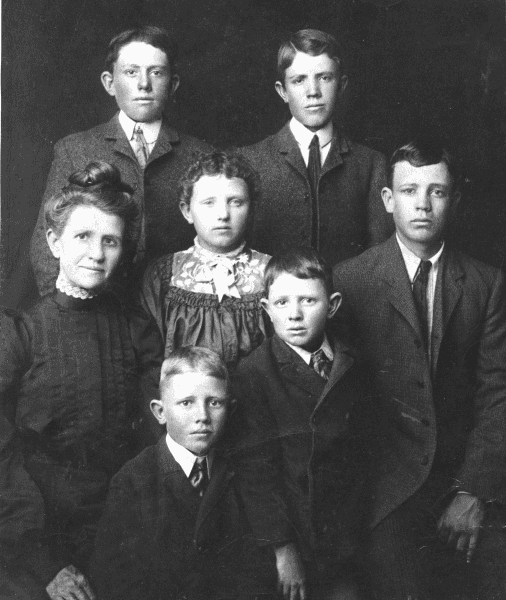

Hannah Elmina Allred Sanders. Photo courtesy of Jayne Peace Pyle.

Hannah Elmina Allred Sanders. Photo courtesy of Jayne Peace Pyle.

She told us some very inspiring stories. One was about the Indian raid of Fairview. It was the custom for the people to keep their cattle penned up in corrals at their homes at night. The next day, they were taken to the nearby hills and herded during the daytime hours. Her father was away at this particular time. Her mother went out to open the gate so the two boys who had the job of herding all the cattle in the community could also take theirs. As she was letting down the bars, she said she very distinctly heard a voice that said, “Not today.” She immediately securely fastened the gate and went to the house. Later that day, as the boys were herding the other animals, a band of Indians came down from the higher mountains, killed the two boys, and drove the cattle off to their camps. By being obedient and listening to that voice, her cattle were saved.

At the very young age of seventeen, Hannah married a handsome young man by the name of John Franklin Sanders Jr. This event took place on August 31, 1879. A home was made in Fairview for a year. Their first baby, a girl, was born there September 2, 1880. She was a beautiful black-haired darling and was given the name of Myra Irene. Shortly thereafter the Sanders families all started for Arizona, where President Brigham Young had called them to go. A stop was made at St. George. While there they went to the St. George Temple on November 20, 1881. The endowments and sealings were made at that time.

On the trip to Arizona, Hannah stated she was quite comfortable traveling in the covered wagon. She was the only woman in the party to have a cook stove in her wagon. She felt this was quite a luxury. She didn’t have to cook over a campfire as the other women did. The treacherous Colorado River was crossed on her nineteenth birthday. That experience was quite a fearful one. The crossing was made at Pierce’s Ferry.

Like her mother, Hannah had a divine gift, as is shown in the following story she told us. After the river crossing, they traveled on until evening and decided it was time to make camp for the night. Some Indians rode up at this time and offered them a pot of beans. Hannah graciously accepted them. Just then she heard a voice that clearly said, “Do not eat.” She took a tiny taste and found them to be sour. They didn’t eat the beans, instead they buried them. Then they hitched up their teams, rounded up the cattle, and traveled all night. They thought it might be some kind of a trick of the Indians to sicken them and then rob them of their horses and cattle. Is it any wonder that at a later date she was heard to say, “For the first forty years of my life I was always so afraid of Indians”?

The family continued their trip on to Tonto Basin, their destination. It is now known as Gisela. They remained in Tonto Basin until 1892. Five children were born to this couple while they lived there. Their names are Franklin Alma, Lafayette, Elmina, Perry Ray, and Minerva.

Upon leaving that desolate place, a new home was made in Lehi. They wanted the children to be reared in a Mormon community. Five more children were born there. They are John Lester, Carrie, Edith Pearl, Jessie Grace, and Laura. We children remember helping with the fruit canning, jam and jelly making. She was a good cook and kept us healthy with good simple food. Her homemade bread was so delicious and filling. She taught her children to be honorable and industrious good citizens. She was a good neighbor and was never too busy to help others when they needed her. Hannah was neat and clean. Her family remembers her as always combing her hair as soon as she dressed at morning and wearing clean, starched, and well-ironed dresses. Her house was immaculate, with homemade rugs and pretty doilies. The chimneys on the oil lamps were clean and shining.

She held positions in the Primary and Relief Society. Her husband passed away in 1912. At that time, she moved to Mesa and completed the rearing of her five youngest children. With her ability to sew well, she made our clothes and kept us neat and clean.

She died September 29, 1949, at the age of eighty-seven and a half and is buried in the Mesa City Cemetery. At that time she was survived by ten children, fifty grandchildren, and ninety great-grandchildren. We all honor and revere her blessed name.

Ellis and Boone:

If there is one area in Utah associated with the Allred surname, it would be Sanpete County. Both James Allred and his brother Isaac brought their large families to these communities, and their descendants have served in bishoprics and presidencies of all auxiliary organizations associated with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. James Allred is considered the founder of Spring City, and Isaac Allred, although also living in Spring City sometimes, usually lived in Mt. Pleasant. Isaac Allred and several of his sons were prominent violinists for the county.[11] After several moves, the town of Fairview became the home for Hannah Allred Sanders and her family.

Sanpete County, known for its agricultural products, was called “the Granary of Utah.” The summers were mild, and, although rainfall was only 10–12 inches per year, there was plenty of snow in the mountains. Similarly, Mesa usually had sufficient water for agricultural products, including flowers. As mentioned here, Irene Sanders Watson of Mesa got her inspiration for a flower shop from her Grandmother Almira Allred’s yard in Fairview, Sanpete County, Utah. People in Spring City, Utah, claim that the local killdeer with its multi-note call says, “Spring City is a pretty little town.”[12] Likewise, flowers from Watson’s Flower Shop have decorated miniature floats, gladdened the hearts of recipients at funerals, proms, or just special occasions, and made Mesa “a pretty little town.”[13]

Mary Luella Higbee Schnebly

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP

Maiden Name: Mary Luella Higbee

Birth: March 7, 1875; Winchester, Clark Co., Missouri

Parents: Louis Bryant Higbee and Cynthia Ann Waples

Marriage: Dorsey Ellsworth Schnebly; May 2, 1906

Children: Cynthia Marie (1907), Gertrude Reba (1908), twins Dorothy Alice and Daniel Ellsworth (1911)

Death: October 27, 1966; Farmington, San Juan Co., New Mexico

Burial: St. Johns, Apache Co., Arizona

In Missouri in the good old days, the principal of the rural schools had the right to recommend one of his pupils for a scholarship at some institute or college. Prof. Dorsey Ellsworth Schnebly was teaching school at Winchester, Missouri, and he selected Mary Luella Higbee as his brightest pupil and the one who would make the most of her opportunities; to her was given the distinction of going to college and preparing to be a teacher.

It was indeed a blessing to this young girl, who was ambitious to make something of herself, but whose hopes could not otherwise have been realized, because she was the “middle” in a family of seven children. Louis Bryant Higbee and his wife, Cynthia Ann Waples, were able to care for their family and only give them a common grade-school education.

Their farm was five miles from their nearest school, so the children had to go in a cart, buggy, or on horseback and many times suffered from high winds and inclement weather. But in spite of all disadvantages, Mary Luella never faltered, not even when she would have to go away to prepare herself for her chosen profession.

Born March 7, 1875, on this farm near Winchester, Clark Co., Missouri, Mary Luella spent many happy days during her childhood. There were an abundance of wild plums, cherries, grapes, berries, persimmons, black haws, and hickory, hazel, and black walnuts.[14] All of these the children gathered for their winter food. There would be barrels full of nuts, and the father would go to Warsaw, Illinois, and trade for a wagon load of apples so that during the long winter evenings there would be refreshments for the family and their frequent visitors. There was always popcorn to pass around. The games during these evenings were checkers, dominoes, caroms [billiards], and other such harmless ones. Gambling cards were never allowed on the place.

The father was a good provider. He raised the meats, wheat, corn, and other staples that his family consumed. The nearest store was eleven miles away, so many things had to be done without or substituted.

Luella went to a finishing school in Kahoka, Clark Co., Missouri, and began teaching when she was eighteen and taught for twelve consecutive years.

After two years teaching in his native state, Mr. Schnebly came west, first to Washington where he was principal of their high school in Pomeroy for a long time. Afterwards he came to Arizona and taught school, in all, twenty-five years.[15]

Always there was the remembrance of his honor student, and he went back to his home town once to see her, but she was away teaching and his vacation was so short he could not follow her. When, at the age of thirty-five, he decided to marry, he wrote to his sweetheart, who was then thirty-one, to join him in Flagstaff, Arizona, where they were married May 2, 1906.

Her husband had been teaching at Sedona, on Oak Creek, for some time. One of his school years was a record-breaking one, in that there was not an absent or tardy pupil during the entire time.

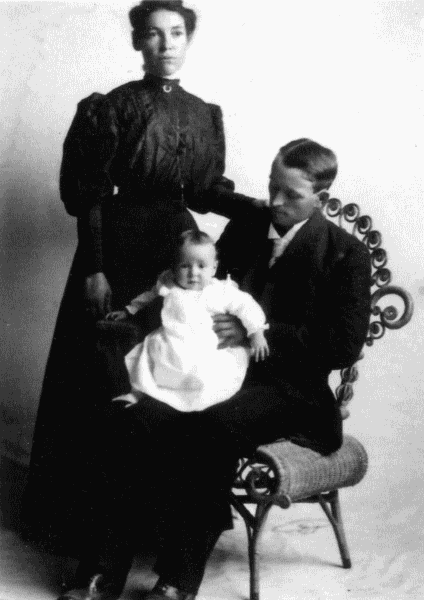

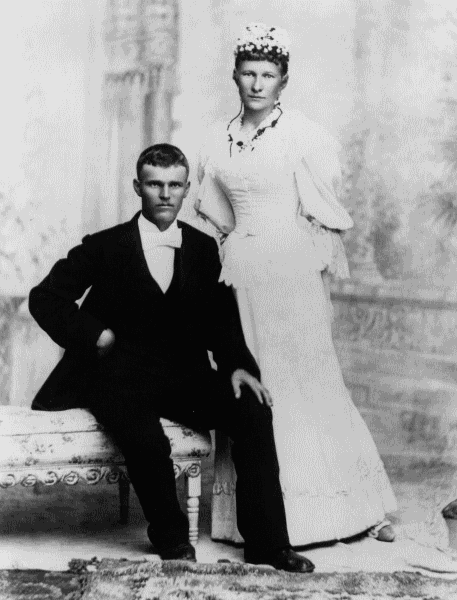

Mary and Dorsey Schnebly with baby Marie. Photo courtesy of Jeaneane Klefsky.

Mary and Dorsey Schnebly with baby Marie. Photo courtesy of Jeaneane Klefsky.

Mr. Schnebly, for whom the Schnebly Hill was named, took his bride to his ranch on Oak Creek, and there they continued to reside.[16] Their two eldest daughters were born there, and then Luella took them back to “show them off” to their proud relatives. While in Missouri, a pair of twins, a son and a daughter, were born to them—the little girl lived for five months, the son grew to manhood, began teaching at the age of eighteen, and is beginning his tenth year of teaching all in one school.

When the World War broke out, Mr. Schnebly answered a questionnaire and expected to be called into his country’s service, but he never was. He did his bit by teaching the youth of the land, and so interested was he in their education that his pupils gathered at his home many an evening for private instructions.

After leaving Oak Creek, the family moved to a ranch near St. Johns in Apache County. Mr. Schnebly taught for seven years in District No. 1. When the son was old enough to start in school, his mother was his first teacher, and he only had two teachers aside from his mother and father. The two daughters were pupils of their father.

The home life of the Schneblys was very simple and happy. Most of the time was spent on one of their cattle or sheep ranches [illegible number] miles from neighbors, and the family developed its own social life. The father was an excellent storyteller and reader, and the foundation of good reading was early laid.

The children loved nature and the great outdoors. They rode stick horses and hunted arrowheads and Indian pottery. On the rare occasions when there was water in the Zuni River [north of St. Johns], they went wading.

They did not lack for amusement though they were so far from other children. Their home life was all sufficient. Although the mother was a teacher and taught in every grade in school, she was first a mother, with a mother heart large enough to envelop all her pupils, which no doubt accounts of her thirty-one years of successful teaching.

Mr. Schnebly was a genial host, won friends by his jokes and good humor, and Luella had plenty of time to supervise the cooking and household and entertain her guests, as well as being a companion to her children.

After her husband sold their cattle and sheep interests, the family moved to California, bought a citrus grove, and remained there a year and a half. Returning to Arizona, they bought a home in Flagstaff and lived there while the children attended the normal school.

One winter that Luella looks back on as an experience she would not like to repeat was spent on the ranch alone when the three children were small. Snow that winter piled up to the depth of four and a half feet and laid on the ground most of the time.

In her young days in Missouri, telephones were unknown, but her teacher-lover fixed up a homemade telegraph line between their homes one mile apart, and it was often necessary for him to call her to give her an assignment or for her to call him to help her solve a knotty problem. Arithmetic was always Luella’s favorite subject.

On September 6, 1926, Dorsey E. Schnebly died in Phoenix, where he went on account of his physical condition.[17] His body was taken to St. Johns for burial. He was mourned by friends and former students, many of whom had made places for themselves in the business and social world. Luella has a home in Elfrida, Arizona, but visits around with her family, going occasionally to her home in Missouri.

When her children were asked what her outstanding characteristics are, these were some that were mentioned, and in the order named: generosity, agreeable disposition, sense of humor, understanding, confidence in her children, home-loving, industrious, faith in humankind.

Mrs. Schnebly has been associated with the school system from the days when the three R’s were taught in the one-room log house, to its present degree of efficiency, and bids fair to live many years to witness its further improvement. Though she gave up actual school work when she became sixty years of age, her children often go to her with their knotty problems. Eighty-seven years as school teachers is a record for a family of five, and the children give promise of teaching as long as their mother has. No one can estimate the wide spreading influence of this wonderful wife, mother, and teacher.

Ellis and Boone:

RFC submitted this sketch to the FWP on September 6, 1938, but did not include it in PWA. It may be she recognized that much of this sketch deals with the life of Dorsey Schnebly rather than Mary, because sketches for other non-LDS women were included in PWA.

Ultimately, however, Mary Luella Higbee Schnebly’s life did have a Mormon connection. Although the Schneblys were not Latter-day Saints while living in St. Johns, Mary’s children began joining the Church in 1928. Daniel, in particular, was influenced by an LDS roommate while attending school in Flagstaff. He then married Anna Flake, daughter of James M. Flake, in 1931. Mary Luella Higbee Schnebly herself was baptized on February 16, 1938. Before her baptism, she read the Book of Mormon, but she hid it under the mattress whenever anyone else was around.

Lisa Schnebly Heidinger, a great-granddaughter of T. C. Schnebly and writer for Arizona Highways, told of finally understanding this Mormon connection. She wrote, “The St. Johns cemetery yielded some of my own family’s Mormon history. My great-grandmother, Sedona, came west with her husband, T. C. Schnebly, at the behest of his brother, D. E. Neither my father nor his sisters knew where D. E. ended up after he drifted away from Oak Creek Canyon. When I went to St. Johns to do a story about Morris ‘Mo’ Udall, the venerable Arizona congressman, we were at the cemetery shooting video of headstones in the Udall plot. In the row behind them was a stone reading ‘D. E. and Mary Schnebly: Teachers.’ This, then, was where the wandering brother’s path concluded.”[18]

Phoebe Earston Johnson Scott

Autobiography

Maiden Name: Phoebe Earston Johnson

Birth: November 17, 1881; Concho, Apache Co., Arizona

Parents: Sixtus Ellis Johnson and Mary Ann Haslam

Marriage: George Washington Scott; December 12, 1899

Children: Mary Ellen (1902), Zina (1904), Nora Lavinia (1907), Pearl (1913)

Death: December 2, 1988; Glendale, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

I, Phoebe Earston Johnson, was born November 17, 1881, at Erastus, later Concho, Apache County, Arizona. I was the tenth child of Sixtus Ellis Johnson and Mary Ann Haslam.

My grandfather, Joel Hills Johnson, joined the Church in 1831, the year after the Church was organized. He was the first of the Johnsons to join the Church. My father’s mother was Annie Pixley Johnson, her name being Johnson before her marriage.

My mother’s parents, William Haslam and Ann France, heard the elders in far away England. They accepted their message, joined the Church, and came to America in 1854 when my mother was nine years old. Her sister Elizabeth, who was sixteen, died and was buried while crossing the plains.

The family settled in southern Utah where my father and mother later met and were married April 18, 1863. They were married in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City.

My mother was a plural wife, my father already having one wife (Editha Melissa Merrill [married August 3, 1851]). Later he took another, Mary Stratton [married August 31, 1867], so we were quite a large family. My own mother had thirteen children. Of these, two were stillborn, and seven died young. She raised four to adulthood [Ellis, Nora, Wallace, and Phoebe], and of those four I was the youngest.

Some of my childhood memories are a little knoll just a little way from our home where we used to go gathering wild larkspurs. I remember one day my mother was sick and Aunt Mary was over caring for her when we saw a snake. It frightened me so that I could never forget it. Another occasion I remember was going with my sister when she was baptized, and the lovely bouquet of flowers a lady gave to her.

In 1876 my Aunt Editha died, leaving five children. (This was while the family was still living in Johnson, Utah, and prior to their moving to Arizona.) After her death, my Aunt Mary took her children and cared for them as her own. [In 1880, Sixtus Johnson was living in St. Johns, Arizona, with his third wife and children from both Editha and Mary; by 1881, Mary Ann Haslam Johnson and her children were living in Erastus (Concho).[19]]

In 1885, my father decided to move to Old Mexico. There were too many of us to go all at once, so he took the others first, and then came back for Mother and her family. Our only transportation was a team and wagon, and it was a long and tiresome journey. We drove our cow and milked her on the way. I was between four and five years old at the time, and I remember how happy we were when we got to the end of our journey.

When the first families arrived, they settled on what was called the “Old Town Site,” but by the time we arrived they had laid out another town site, so we went there and were the first family to move into the town of Juárez. Our first home there was a rock house that Father built, and after living there for some time, my mother’s family moved to a small town up in the mountains which was called Cave Valley. It was while living there that Father’s third wife Mary passed away in childbirth, August 16, 1890. By this time, however, the children of Father’s first wife were grown and married, so Aunt Mary’s children lived with us, and my mother loved and cared for them as her own. The youngest one was two years old.

When we first moved into Mexico, there were twenty in the family, and times were hard, so we didn’t have all of the luxuries of the world, but we never suffered for the necessities of life.

Our next home was just a short distance away where Father built a frame house. It was here that I grew from childhood to girlhood. We were a happy family. I used to help Mother card the wool. She would spin the yarn, and we would knit our stockings. We made our soap, our starch, and as there was no electricity, many times we made candles to give us light. We used a washboard to wash our clothes on, and heated our irons on a wood stove to do our ironing. Yes, it was quite different from today when we can just push a button.

The first thing my father did every time we moved was to set out an orchard and plant vegetables so we usually had plenty of fruit and vegetables.

Juárez was where I first went to school. The first year I only went to school half the day since I wasn’t very strong. Father used to call me his “Frail Flower.” We lived there until I was fifteen, then we moved again. This time up in the mountains to a place called Chuichupa. It was a very beautiful town surrounded by tall pine trees, and there were flowers everywhere. I was the secretary in both Sunday School and Primary. It was just a small settlement, and the first year there was no school, so a cousin of mine and I had school for the children of the ward. It was just a free contribution, but we enjoyed it very much. At the close of our school we had a program and invited all the parents. One man gave each of us cloth for a dress. It was lavender and white. We made them just alike.

We really had good times sleigh riding and horseback riding.[20] One time I was dragged some distance by a horse, and I still marvel that I wasn’t killed, but I guess my time hadn’t come to go.

Our next move was to Nopala in the state of Sonora. My father was presiding elder there. The town of Oaxaca was five miles away, and we used to go there, but when the river was high we would go over the hills and cross just once in a boat. It was in Oaxaca that I met my future husband, George Washington Scott, and we were married there on December 12, 1899, by Apostle Abraham Owen Woodruff.[21]

The following December my husband and I, my sister Nora and her husband, Harlow Carlton, and Woodruff and Alice Judd with their six-month-old baby left Mexico to go to the St. George Temple. We went in two wagons, and we had a lovely trip until we struck snow in the mountains about thirty-five miles from St. George. I will just write what was written in the paper “The Dixie Falcon.”

Messers Carlton, Judd and Scott arrived in St. George Friday evening from Mexico. Their story is an uncommon one and shows that they had far from clear sailing at least the latter part of their journey. They left Mexico with two teams and crossed the Colorado River at Scanlon’s Ferry.[22] They struck heavy snow about 35 miles south of here and abandoned one of their wagons putting both teams on the other wagon, but this they were also compelled to leave, and put their wives on the horses, one carrying a little child, so completed their journey. Their provisions gave out and they were two or three days without food. They finally came upon a wagon loaded with beef. Someone had apparently been on their way taking meat to Pulsipher Saw Mill when the snow had become too deep, and they had taken the horses and gone back, knowing that the meat would freeze and be all right. They were provided with enough to relieve them though it had to be eaten by itself (without salt). It greatly renewed their strength. They are well taken care of here and will not care to risk another such journey soon. The Dixie Falcon[23]

From St. George we went to Virgin City and visited my grandfather Haslam who was then past ninety.

On August 7, 1901, my father-in-law, Franklin Scott, was killed by lightning [at Oaxaca], and just five years later his son, Franklin Scott Jr., was also killed by lightning.

Our first daughter, Mary Ellen, was born on March 1, 1902. I remember that our first house was a brick one. My husband made and burned the bricks himself. At this time I was very active in the organizations of the Church, being counselor in YWMIA, a Sunday School teacher, and a visiting teacher in Relief Society. Zina, our second daughter, was born on June 13, 1904.

In November of 1905, we had a flood which swept over the town of Oaxaca. It had rained for a week, and the Bavispe River rose until it flooded the whole town. People were compelled to seek higher ground in order to avoid the water. My husband was away at the time, so I took our two little girls, and three other children who were living with us, and went to the home of my sister-in-law who lived on the hill.

Oh what a night! All night we listened to the houses falling and wondered which was ours. When daylight came our house was down along with most of the others. There were only five houses left standing.

We next moved to Morelos, about twenty-five miles from Oaxaca. It was here, on May 15, 1907, that our third daughter, Nora Lavinia, was born. During the next five years, we built two homes. The last of these was a five-room adobe house in town, where we intended to make our home. However, in August of 1912, because of the revolution in Mexico, we were forced to leave our home and come to the United States for safety.

Just a short time before leaving Mexico, my father discovered that he had a cancer on his lip. He and Mother made a trip by team 125 miles to a doctor who operated on him. His lip healed so rapidly that the doctor, who was a non-Mormon, said, “Mr. Johnson, I want you to tell me about your life.” Father said, “There isn’t much to tell, but I have never used tobacco, liquor, coffee, or tea.” The doctor said, “That accounts for it.”

I should also like to tell two more faith promoting incidents:

My mother had dropsy. She became so swollen that it was impossible for her to lie down to sleep. She had been administered to many times. One day, when she had been very bad, my father and his brother, uncle David Johnson, administered to her. From that time on she began to get better, until she was completely well. One day, a stranger came walking down the road, leading a donkey. He asked for water for the animal. As the animal drank, he and Father stood there talking. Father told him his wife was very sick and that there wasn’t a doctor within a hundred miles. The stranger listened and seemed very much concerned. He asked several questions about her and then said, “You follow that trail that I just came over and about a quarter of a mile back you will find a bed of herbs with little yellow flowers on it. Gather it, steep it, and give her the tea. I am sure it will help her.” Father thanked him kindly. He lost no time in getting the herbs and making the tea.

One night, my daughter Ellen had such a bad sore throat. I think it was what we would call quinsy now.[24] Her throat was swollen so badly it was hard for her to breathe. There was no doctor. My husband was away from home; I was all alone. I had tried everything I knew. I went into another room and earnestly prayed for help. A voice spoke to me and told me what to do. I prepared the poultice and put it on her throat. She soon received relief and went to sleep. I used this same remedy many times, and it always worked.

After the revolution started, we went by team and wagon from Morelos to Douglas, Arizona, taking with us the few things we could, but leaving most of the things we’d worked so hard for behind. In Douglas, the United States government provided tents for the people to live in. We didn’t stay in Douglas very long; we moved to a ranch. Then about Thanksgiving time, we moved to Pomerene, Arizona. Here on January 21, 1913, our fourth daughter, Pearl, was born.

While living here, my father, Sixtus Ellis Johnson, passed away at the age of eighty-seven, June 14, 1916. He was a kind, loving father and was greatly missed by everyone.

We homesteaded there, but because of a scarcity of water, we moved again, this time to Gilbert, Arizona, near Mesa. It was the year the armistice was signed and during the terrible flu epidemic. I remember that for several weeks no public gatherings were held. From Gilbert we came to Mesa in 1920. In 1925, we bought a twenty-acre farm. We had a farm loan on it. These were hard years, and sad ones. In 1922, my mother passed away in Chandler, Arizona. In 1923, my mother-in-law, Sarah Scott, passed away in Gilbert. Then in 1925, my husband passed away in Prescott, Arizona, where he had gone to see if his health wouldn’t improve. Now we were left alone, my four daughters and I.

Three of the girls went through high school and one through college. We let half of the land go. We all worked hard but didn’t get the loan paid off until 1944.

Today is June 3, 1965. She [Phoebe] is eighty-three years old. She is a Relief Society visiting teacher and attends the Mesa Fourth Ward.

At the time of my father’s death, she was forced to go out as a midwife to help make ends meet. It was a great nervous strain, and her eyes went back [bad?] on her. Ever since she has had spasms of the muscles and her eyes go shut. It’s been a real struggle for Mama, but she hasn’t given up. She goes to the temple every time she gets a chance. She still makes us fig jam, and her cookie jar is always full of cookies. At one time, she crocheted each of her girls a bedspread, and has made us quilts by the dozen. She has helped us all in a financial way. She helped us get musical instruments for our children, and she gave each of her girls two city lots when she subdivided her place.

Ellis and Boone:

Phoebe Scott lived to be 107 years old; she died December 2, 1988. The author of the last two paragraphs is unknown but obviously one of her daughters.

Phoebe Johnson Scott left a remarkably clear account of relocations from Concho, Arizona, to the various towns in the states of Chihuahua and Sonora, Mexico. After 1912, her moves to Douglas, Pomerene, and Mesa, Arizona, were typical of the Sonoran refugees from Mexico during the Revolution.

James Henry Martineau makes a passing reference to George and Phoebe Scott in his journal. In November 1898, at age seventy, Martineau was ordained a patriarch for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[25] As such, he traveled throughout the Mormon settlements in Mexico giving a blessing to all those who requested one. In January 1900, Martineau traveled to Colonia Oaxaca with President Anthony W. Ivins and company. Martineau then continued twenty-five miles further to Batipito (later known as Colonia Morelos) and began surveying the town site. On February 11, a dependent branch of the Oaxaca Ward was established at Batipito with L. S. Huish as presiding elder. On February 18, 1900, Martineau recorded that while “at Oaxaca, I blessed Anna Naegle, Geo. W. and Phebe Scott by their request.” The next day he “started for home in a heavy gale, which broke limbs from the trees,” and arrived in Colonia Díaz on February 21, 1900.[26]

Margaret Hunter Shelley

Thomas H. Shelley and Marie Shelley Webb

Maiden Name: Margaret Hunter

Birth: July 29, 1859; Armadale, Bathgate, West Lothian, Scotland

Parents: James Hunter and Mary Robertson

Marriage: James Edward Shelley; December 13, 1875

Children: Mary Maud (1876), Elizabeth Charlotte (1878), Sarah Ellen (1881), Margaret May (1883), Thomas Heber (1885), James Hunter (1888), George Elsmore (1892), Walter Clyde (1895), twins David Franklin and Ammon Edwin (1897), Eliza Marie (1900), John Edward (1904)

Death: May 6, 1931; Joseph City, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Heber, Navajo Co., Arizona

Margaret Hunter Shelley was born in Scotland, July 29, 1859. Her parents were converted to the Church in Scotland. When she was seven years of age, the family came to the United States landing on the East Coast. Money was seriously scarce with them. Her father and brother had been employed in coal mines. Those who know of wages paid in those mines at that time will realize that the family was in a condition of poverty. This being the case, they had to work at whatever and whenever they could as they wended their way to Utah. While on a job in Pennsylvania in a mountainous place, her little sister was killed by a rolling rock, the mother witnessing the tragedy. Carelessness of a worker who had been drinking caused the death.[27]

“Maggie,” as she was called, told of the long, tiresome travel before reaching Utah, and how that, if they had enough to eat, she had to work, and no schooling was possible.[28] In fact, three months in a schoolroom covered her entire opportunity. However, she learned to read and could do so intelligently, even in public. This, of course, was evidence of a bright mind.

Margaret Hunter Shelley. Photo courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

Margaret Hunter Shelley. Photo courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

On reaching Utah, the town of American Fork was made their home. Here she met James Edward Shelley and in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City she became his wife for time and eternity. The marriage took place December 13, 1875. A foundation of a house was made with all intentions of living in comfort in that fruitful land just blooming with opportunity.

In February of 1876, a number of young married people were called by Brigham Young to colonize on the Little Colorado River in Northern Arizona. Their faith in the Lord and in the authority of the Prophet Brigham Young caused them to put aside their treasured plan of a home among friends and relatives in Utah and head for Arizona, along with others who were called. Note their faith and obedience to the will of the Lord.

After six weeks of cold winter weather, with their ox teams and few horse teams pulling covered wagons, they had reached their destination, which at first was known as Allen’s Camp. Then they moved a very short distance west where, for protection from Indians, they made a fort by making small living quarters out of cottonwood posts and logs. The houses were joined together, making sort of a mule shoe in shape. Here they lived what is known as the United Order, all eating at the big table and all supposed to share alike.

By means of dirt dams, water was turned out of the river a few miles above and farming began. However, this was very discouraging since many times the dams washed out leaving the crops to suffer and to make food short. There was no give up with such great pioneers.

Let us think for a moment on what these young wives faced at the time of childbirth. There were no doctors, and the midwives were not experienced. Twelve children were born to the Shelleys. Parents depended on the Lord.

Shortly after reaching Utah, all Maggie’s sisters and brothers and father passed away. Her mother survived, but had a stroke and became helpless. The writer remembers her lying in the home at Heber, Arizona, (Heber became the home in 1883) where he often moved her hand for her comfort. She was in this condition three years, and then passed away.

In 1887 [Margaret] and her husband did endowments and sealings for all the dead relatives they had record of. This they did for both the Hunters and the Shelleys. Maggie had very little information as to her relatives. A few years before her death, she said her grandmother appeared to her explaining that a mistake had been made and she was not sealed to her husband. She not only appeared once, but three times, pleading for the work to be done. Her husband, being an educated bookkeeper, believed all had been cared for and that he had made careful record. About three years before her [Margaret Shelley’s] death, at a family reunion, her attention was called to her many children and grandchildren and a promise was made that the mistake would yet be found and the sealing cared for. This promise pleased her very much, and she passed away with a feeling of satisfaction and hope.

About three years after her death, a granddaughter, Margaret Turley, was searching in an old family trunk. To her joy she found a record written in the handwriting of James E. Shelley (who as stated before was Maggie’s husband). There was a list of names showing names of wives sealed to husbands. This list was about eighteen inches long and there the truth was made clear. The list showed that the grandmother’s message about her not being sealed to her husband was true. The record was cleared, and a son, Thomas, and his wife, Eva Tanner Shelley, did the necessary temple work.

What a joy and how faith promoting this has been to the family of James E. and Margaret Hunter Shelley. She died May 6, 1931.

The following is submitted by Marie Shelley Webb, a daughter:

Living in the little town of Heber, many miles from a doctor, Margaret Hunter Shelley took care, after a midwife assisted in birth, of the new grandchildren that came along. But with the birth of the third child of her oldest daughter, a serious kidney infection set in. She remained bedfast and seemed to make no improvement. They had a doctor make a visit, but what he did for her did not seem to help.

She was lying very discouraged one day, when she suddenly said to her mother, if Uncle Sam Porter, a brother-in-law by marriage and a very good friend of her mother’s family, could administer to her, she would get well.

Due to the fact that he lived fifty miles away and no way but by horseback to get word to him, her mother decided her only hope was to kneel and pray that he be impressed that he was badly needed.

Her prayer was answered as Uncle Sam came home to his ranch house and told his wife he was going to Heber as he felt he was needed there, so the next night at sundown he came riding in.

He administered to her and she began improving at once, and lived to raise five more babies, who have been very active and carry with them the same faith that helped their grandmother through so many of her trials.

Ellis and Boone:

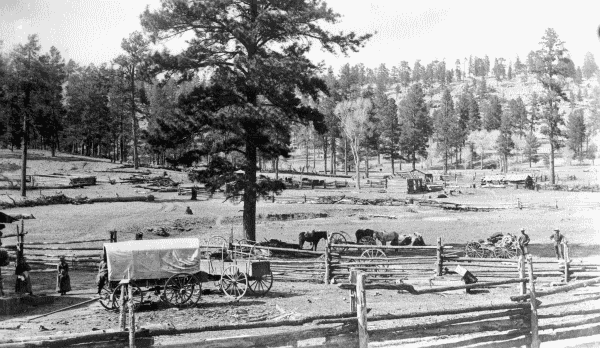

This area, Wilford, is near where the Shelley family settled after leaving Joseph City, c. 1886, F. A. Ames, photographer. Photo courtesy of National Archives.

This area, Wilford, is near where the Shelley family settled after leaving Joseph City, c. 1886, F. A. Ames, photographer. Photo courtesy of National Archives.

Tanner and Richards, in their book about the early Little Colorado River settlements, wrote that when the Shelleys came to Arizona, James E. was twenty-four years old and his wife, Margaret, was sixteen, “the youngest of the brides of the Joseph City pioneers.”[29] John L. Westover and Electa Westover Turley recorded details of the birth of the Shelley’s first child:

Maggie and Jimmy had not shared the secret of their prospective parenthood with anyone [when they left Utah], but Maggie’s mother-in-law had eyes to see and heart to understand. She made the leave taking as painless as possible and presented Maggie with yards and yards of flannel. “My dear,” she quietly said, “you can use this I’m sure.” The valuable gift was carefully stored in the covered wagon.

The wilderness home in St. Joseph proved to be so uninviting and the work involved to raise that first scanty crop was tremendous. Maggie watched with admiring heart the faithfulness of her Jimmy. She had tried hard not to complain, but Jimmy had so little time for her. As the days drew nearer for the expected arrival of the new baby, Maggie became characteristically fearful and apprehensive. Not being able to suppress her fears any longer, she resorted to tears, crying out to the inexperienced Jimmy that she didn’t know what she was going to do. “Oh Jimmy,” she wailed. “Sometimes women die.” “Now, now Maggie don’t you worry,” soothed the young husband. “Sister Neilson will help you. She knows a lot. Why just the other day she helped old Brindle have her calf. The men experienced with cattle could do nothing but Sr. Neilson knew just what to do. The old cow got along all right.”

Maggie’s pride was hurt. Why couldn’t Jimmy understand her condition better[?] The idea of comparing her to an old cow was almost beyond endurance. However, St. Joseph’s early midwives were capable of ushering in new life be it calves or babies. Maggie’s new baby was delivered safely and properly clothed in flannel given by a knowing grandmother.[30]

Harriet Stronach Paynter Shill

Wright P. Shill[31]

Maiden Name: Harriet Stronach Paynter[32]

Birth: March 16, 1848; Cheltenham, Brimafield, Gloucestershire, England

Parents: William Paynter/

Marriage: Charles Goulding Shill; February 9, 1867

Children: Ella Deseret (1867), Milo Goulding (1869), George Washington (1872), Charles Victor (1875), Orson Obed (1877), Wright Paynter (1880), Ralph Freeman (1882), Renus Edmond (1885), Frank Erastus (1888), Harry Scott (1890), Otto Stronach (1893)

Death: June 20, 1931; Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

About one hundred years ago (Mother was born March 16, 1848), there lived in Golden Valley, a small settlement near Cheltenham, England, a little black-eyed, black-haired girl, who was destined to become a great mother in Zion. No, she would be the last one to assert any claim to greatness and nobility should she be asked, but her posterity call her blessed and a great mother in modern Israel.

Harriet Stronach Paynter Shill, c. 1900, Mesa. Photo courtesy of Christine Schweikart.

Harriet Stronach Paynter Shill, c. 1900, Mesa. Photo courtesy of Christine Schweikart.

Her parents were of the poorer class financially, but were thrifty and careful as it was necessary to be in England at that time, in order to provide for a growing family of children; the habits of thrift were implanted in this little girl. Her activities were similar to that of other healthy and normal children, and there was no doubt considerable mischievousness in her makeup as there is in most normal children.

Her education was very meager as free schools in those days were almost unknown, and most of what book learning she acquired was learned in Sunday School classes. However, she had an alert mind, even brilliant, for one of her opportunities.

She had an aunt who was a particular favorite and, besides her mother, she was perhaps her dearest and closest friend, and she was much in her company.[34]

About this time, the gospel as revealed through Joseph Smith was taken to England, and a very energetic missionary crusade was carried on throughout Great Britain. Her aunt became converted to the message the Mormon elders brought, and this little girl just in her teens also heard the elders and was convinced of the truth of their testimonies, and of course wanted to join the Church. Here, her troubles started, for her parents did not see as she did regarding the message of Mormonism and became very antagonistic; they forbade her hearing the Mormon elders, even forbidding her a home if she persisted in going to the Mormon meetings. This attitude of her parents drove her closer to her aunt, and she spent as much time in her company as she could, and in that way kept in touch with the teachings of the elders, and in due time was baptized into the Church, unbeknown to her parents, by Elder Miles P. Romney.[35]

Time came when her aunt decided to gather to Zion in America, and she wanted so much to go with her, but she was forbidden by her parents, and not being of age she could not go. Her aunt advised her to stay, and when she became of age she could follow her.

Her aunt left and many days passed before any word came from her. One night, this little girl had a dream or vision. She saw the great American plains and an emigrant train wending its way across the trackless wastes. A halt had been made by a fresh but lonely grave. When the burial had taken place, the captain of the company took a piece of board from the end gate of a wagon, and wrote the name of her aunt upon it and placed it at the head of the grave, saying some relative coming after may see it. Her heart filled with sorrow as this dream told her she never would meet her aunt in Zion.[36]

Two years passed, and she now had her chance to go to Zion. She landed in New York Harbor, July 4, 1866.[37] At Council Bluffs, she started across the Great Plains.[38] After many days travel she came to a country that seemed familiar. She said to her two girl companions, “This is the place I saw in my dream. The mountains and all looks just as it did in my dream. This must be the place where Aunt is buried. Let us find her resting place.” The girls said, “That was only a dream, you cannot find her grave in this wilderness.” “Anyway let us try,” said she, and after a brief search they saw the grave and the piece of board with the name of her aunt written upon it. There in the trackless American desert, far from human habitation, a faithful soul had been laid to rest. It was a great satisfaction to this young girl to thus be able to visit the last resting place of her beloved aunt, and when in Utah she met the man who marked the grave and got all the details of her death.

When she reached Utah, she met her future husband and was married in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City in 1867.[39] They made their home on Lost Creek at Croydon, a little settlement about forty miles east of Ogden, Utah. It was a small valley with towering mountains on either side. There were about twenty families in Croydon, and her neighbors were her dearest friends.

In that small community, there came the dread malady—diphtheria. Her nearest and dearest neighbor lived just 150 feet away, and imagine the fear and anxiety when, with a household of little children, her neighbor’s family was stricken and two fine children were lost to the dread disease. That situation called for the highest type of faith and fortitude.

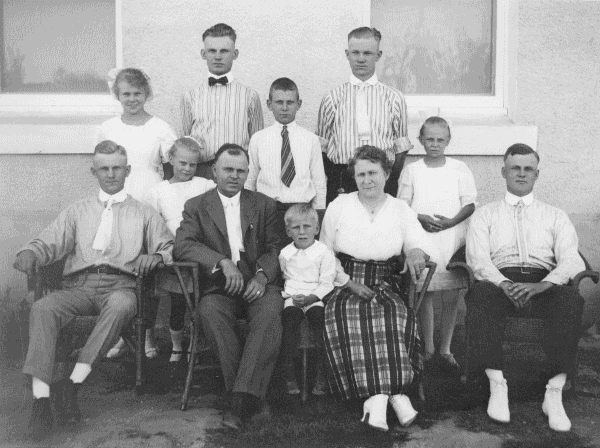

Charles Goulding and Harriet Stronach Paynter Shill photographed on July 4, 1897, in front of their home in Mesa, Arizona. Included in this photograph are all eleven children, two daughters-in-law, one son-in-law, seven grandchildren, and the family dog. Photo courtesy of Christine Schweikart.

Charles Goulding and Harriet Stronach Paynter Shill photographed on July 4, 1897, in front of their home in Mesa, Arizona. Included in this photograph are all eleven children, two daughters-in-law, one son-in-law, seven grandchildren, and the family dog. Photo courtesy of Christine Schweikart.

Her first child was an only girl. When her fifth son was born and when the baby was about five months old, she was stricken down with typhoid fever and had the following experience, which she has often told to me and other members of her family: It was a visit made into the spirit world. During her illness she became very low and finally passed away. Her passing was real, so real that Father and others made all preparations for her burial. Mother said she was conscious of her spirit leaving her body and could see her lifeless corpse as she was released from it, and she passed into the spirit world, and was taken in charge by someone who acted as a guide. She saw great concourses of people, and they seemed busy and contented. The surroundings were very beautiful, and she felt so good and longed to mingle with the people there, but she was told by her companion that she could not stay, that her work in mortality was not completed, and she would have to return to her mortal body. She said she did return and saw her body again, and she thought how impure the mortal tabernacle was and was loath to take it up again. Nevertheless, she entered her body again and was conscious of the preparations being made for her burial, and she worried then that she would be buried alive but was unable to communicate her fears to anyone. Father said he was busy making the coffin for the body, when something told him to go and bend her legs, and he did so and Mother said that caused her pain and was the first sensation of returning life. From that time on, she gradually gained strength, and during the time of her convalescence, my father sold his home in Utah and moved to Lehi, Arizona [about 1881], and five more sons were born to her, making a family of ten sons and one daughter, thereby rests her claim to being a great mother in Israel. To bear a family of that number in those days without the help of medical science as it is known today, and nurse them to maturity, and instill in them the principles of the gospel would amply justify her title to a mother in Israel.

She was a devoted and sincere member in the Church, a true Latter-day Saint, and had great faith in the powers of the priesthood. Many examples of that power in restoring the sick were seen in her family.

In this connection I wish to add my personal testimony concerning the healing power. One day, I remember asking Father and Mother if they had seen the signs follow the believer as was promised in the scriptures, and soon after there occurred this experience. My youngest brother, then just a child of two years, was afflicted and had been constantly annoyed by a severe cough until he was about worn out. Mother asked Father to administer to him and as soon as he did so his cough stopped, and Father said to me, “That is an answer to your question about signs following the believer.” The child had no further trouble with the cough. I consider this a very remarkable case of healing. With an older person, one might suggest that one might have such an influence over his mind as to cause a cessation of his cough, but with a little child that could not occur. So it was a testimony to me that the Lord surely hears the prayers of those who ask in faith. Many other similar experiences I have been permitted to witness.

She lived to see her family grown and to be honored and called blessed by them. Her posterity is numbered in the hundreds. That black-eyed, dark-haired girl and mother in Israel was my mother.

Ellis and Boone:

When Richard White wrote his new history of the West, he considered the different types of migration on overland trails. Although the Mormon migration had some aspects of the community or kinship model, he noted a second type migration, “far less common than community settlement,” which he called utopian. He wrote, “The Mormons provided the best example of it in the entire history of the West. Utopian migrants were not so much interested in maintaining an existing way of life in a better place as they were in creating a new and better way of life.”[40] The utopian model explains the acceptance of death along the trail. Harriet Paynter was sad, but accepting, as she came to understand that her aunt died trying to reach Utah. This search for utopia helps explain the high tolerance many pioneers had for such deaths.

White also described utopian societies as different “from that of the dominant society” and noted that “people who participated in utopian settlements usually sought some kind of separation from that society.” Both of these statements apply to Mormon settlements in Utah and Arizona. He wrote, “The Mormons thought a perfect society possible because of the spark of divinity that they believed all people carried.”[41] In Mormon society, this would probably be called “the Light of Christ.”

One copy of this sketch that Wright P. Shill wrote for his mother includes the title “Bishop 1911” after his name. Although he may not have been bishop of a Mesa ward when writing the sketch (he served from February 1, 1908 to November 1914), he chose to emphasize the spiritual aspects of his mother’s life rather than her pioneer accomplishments.[42] He saw his mother as a woman of faith.

Louisa Minnerly Shumway

Unidentified Grandchild

Maiden Name: Louisa Minnerly

Birth: January 8, 1824; Tarrytown, Westchester Co., New York

Parents: John Minnerly and Catherine Taylor

Marriage: Charles Shumway;[43] August 5, 1845

Children: Catherine (1846), Charles M. (1848), Wilson Glen (1850),[44] Peter Minnerly (1853), Louisa Adalia (1856), Joseph S. (1857), Levi Minnerly (1859)

Death: February 28, 1890; Linden, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Taylor, Navajo Co., Arizona

Louisa Minnerly was born at Tarrytown, Westchester County, New York, on January 8, 1824. Her parents, who according to record were also both natives of that same place, were John Minnerly and Catherine Taylor Minnerly.[45]

Little is known of her early life and family except that at least some of them came to Nauvoo with the Saints. It was here that she was married to Charles Shumway in August 1845 by Brigham Young.

At Winter Quarters, the family suffered great trials. Julia Ann Hooker, the first wife of Charles Shumway, passed away November 14, 1846, leaving three small children, one of which soon followed the mother. Louisa raised Andrew and Mary, the two that were left.

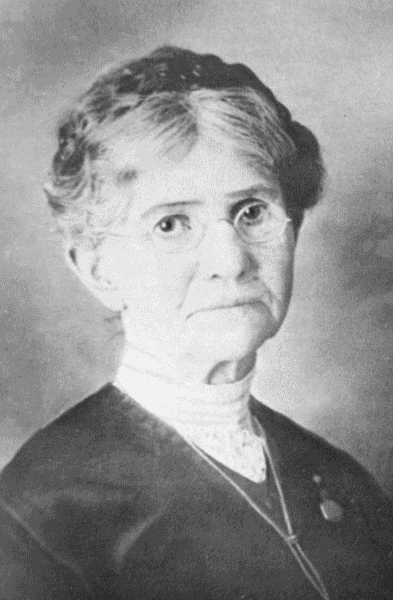

Louisa Minnerly Shumway. Photo courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

Louisa Minnerly Shumway. Photo courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

While at Winter Quarters, Louisa gave birth to a baby, but it did not live. She was very ill, in fact, near to death for some time. She was taken in by a kind neighbor, who nursed her back to health. While she was still bedfast, she happened to be left alone one day for a short time. The broom, which had been used to sweep up the hearth stone, caught fire. She forgot that she was sick and got up and put the fire out.

When the Saints were compelled to move westward, Charles Shumway went with the pioneer company in 1847, leaving his family to follow later, and he returned to meet them. When her husband went ahead to the Salt Lake Valley, Louisa remained with friends, resuming the journey later when she regained her health.[46] When the family arrived in the Valley, they lived in the old fort. Her son Charles was born there.

In answer to a call from Church leaders, Charles Shumway moved into Sanpete County. Here, Indian troubles were encountered. The family had just moved into a new adobe house when the Walker War broke out.[47] Word came to pull down everything before night. Accordingly, the new home was torn down along with other buildings in the settlement, and the families were moved to a place of safety at some distance.

This outbreak proved not to be a serious one. At times, provisions ran out so the breadwinner had to leave his family again. With several other men, he went all the way to Salt Lake City on snowshoes to get provisions.

After this, the family moved to Cottonwood, and Charles was called on a mission to the States, again leaving his family alone. It was during his absence that Johnston’s Army came to drive the Saints out of their homes, and the people had to move south. Upon his return, they moved again to Salt Lake City, and again back to Cottonwood. It seems the Shumways were always on the move, either for industry reasons or to answer the call of authority.

The next move was to Cache Valley. Here they lived at Wellsville, Mendon, and Franklin. At the latter place, a sawmill was operated by Grandfather and the boys. Amid all these moves and frontier hardships, Louisa was always the soul of patience and kindness and is remembered as such by those of her grandchildren who recall any memory of her. She was always industrious and thrifty. She spun and wove and was an immaculate housekeeper.

It was here in Wellsville that Elizabeth Jardine came into the family. She married Charles Shumway on March 29, 1862. She and Louisa were dear friends and lived together a good deal of the time, sharing the joys, sorrows, and burdens of pioneer life.

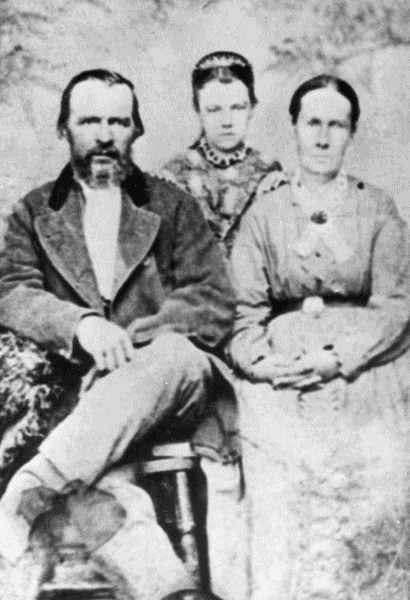

Charles and Louisa Shumway. Another photograph shows saved locks of hair from each. Photo courtesy of International Society daughters of Utah Pioneers.

Charles and Louisa Shumway. Another photograph shows saved locks of hair from each. Photo courtesy of International Society daughters of Utah Pioneers.

In 1874 Charles Shumway was called by President Brigham Young to help settle Arizona. The move was made as far as Kanab, which place was home for one year; then they moved to Johnson. In 1879, Wilson and others of the boys left for Arizona with the cattle. The stock was driven across the Colorado River on the ice. They went to Concho, and in the spring of 1880 the family came, living at Concho only a short time and moving to Taylor in the fall. Shumway proved to be the ultimate place of residence, as the family soon were all there, industriously working building homes. Grandfather built the flour mill there, which has served the settlers of this country long and faithfully.

Here in Shumway, Louisa lived alone for many years. At different times some of her married children lived with her. Her grandson, Wilson A. Shumway, tells a little incident which shows how industrious and independent she was. He says she asked him to clean her pigpen but he, boy-like, procrastinated. A few days later, he happened around to look the job over and, to his surprise, the pigpen had been cleaned and scrubbed by his grandmother.

Louisa had no formal education, but she spelled her way twice through the Book of Mormon, and was known to be a great reader of that book. She always lived on the frontier just ahead of the development of schools and the Church auxiliaries, so she saw little or no church activity, but she was always interested in community life, though her realm was her home.

She went one time to Linden, Arizona, to visit some of the family living there. She was taken suddenly very ill and died there on February 28, 1890. She was the mother of seven children—Charles, Peter, Wilson, and Levi, who grew up, and three who died in infancy. There is quite a large posterity of grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

It is thought she very likely died of appendicitis. (Note—in a letter from Elizabeth, she says that Grandmother Louisa died at the home of Spencer and Lizzie Shumway. Spencer was a son of one of Grandfather’s wives—Henrietta Bird Shumway. They were very dear friends.)

Ellis and Boone:

The Shumway family moved many times with other members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Several times, Louisa moved separately from her husband, including the trek from Winter Quarters to the Salt Lake Valley. Louisa and her stepdaughter, Mary Eliza, were part of the Jedediah M. Grant/

Louisa Minnerly Shumway’s last move was to Arizona. Charles Shumway had three wives in Utah but only two came to Arizona: Louisa Minnerly and Elizabeth Jardine. Louisa died in 1890, Charles on May 21, 1898, and Elizabeth on May 26, 1935. Henrietta Bird Shumway died on May 3, 1910, in Kanab, Utah, but many of her children also came to Arizona.

Maria Annanettie Hatch Shumway

Autobiography, FWP[49]

Maiden Name: Maria Annanettie “Nettie” Hatch[50]

Birth: October 31, 1870; Franklin, Franklin Co., Idaho

Parents: Lorenzo Hill Hatch[51] and Alice Hanson

Marriage: James Jardine Shumway;[52] December 9, 1887

Children: Alice Elizabeth (1888), James Lester (1890), Ernest Hill (1892), Joseph Lorin (1894), Lorenzo Dow (1896), Lula Mae (1898), Calvert Lyle (1899), Nettie Hatch (1902), Almina (1903), Charles Purley (1905), Ezra Jardine (1907), Vera (1908), Thora Agnes (1910), Rawson (1912)

Death: November 18, 1945; Taylor, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Taylor, Navajo Co., Arizona

Having been asked for a short sketch of my life as a pioneer, I will endeavor to give it in the hope that what I may write will meet with approval and be of interest to all who may read it.

I was born in the town of Franklin, Idaho, October 31, 1870. When I was seven years old, my parents, Lorenzo H. Hatch and Alice Hanson Hatch, came to Arizona settling in the northern part of the territory at that time long before statehood was granted.[53] The trip was made by wagons drawn by ox and mule teams. There was my father, mother, five brothers, two sisters, and myself, one sister being a babe in arms. We left our home and traveled by team as far as Salt Lake City. Here, Father, realizing that it would be many years perhaps before we would again have the privilege of visiting a city, had the boys go on with the wagons. Himself, Mother, and we smaller children stopped in the city, and as he had business to see to, he hired a guide to show us the sights of the city which indeed was wonderful. Then, when we were ready to leave the city, he bought tickets so we could have our first train ride. We visited at Lehi a number of days. Then our train riding ended at a small place called York. By that time the boys with the wagons had caught up, so on we came. To me all this was glorious. To my precious mother, I think it must have been a feeling of awe and wonder to know just how she would manage through another siege of pioneering with her family in a new and unsettled land. She had already pioneered in early Utah days, also in Idaho, before this venture into Arizona. She was really and truly a pioneer woman.

J. J. Shumway holding James Lester with Nettie standing. Photo courtesy of Bernice Skinner.

J. J. Shumway holding James Lester with Nettie standing. Photo courtesy of Bernice Skinner.

For sometime, we visited at St. George, Utah, then on to Johnson, Utah, where we made another stop, waiting for other emigrants as we felt the need of company. A family by the name of Dean joined us, also an old gentleman whose name was Liston.[54] We traveled the old wagon road from Kanab, Utah, to Lee’s Ferry. By this time the weather became cold enough so the teams and cattle could be taken across the Colorado on ice.[55] The wagons and house furniture and the family were ferried across on the big boat. In due time, we reached the settlement of Woodruff and here we resided for about two years.[56] Then we moved further up the country finding only one small home in the place in which I have made my home. It was not long then until other settlers came and our town began to grow and was given the name of Taylor.

We were all pretty much in the same circumstances, poor, yet the fathers and mothers felt happy and willing to go ahead and colonize as best they could. At that time, all food stuff and other necessaries had to be hauled from Albuquerque, New Mexico, by team and wagon.

My father homesteaded a farm about two miles from town. After much hard work and we had gotten the water to irrigate with, times began to be better, at least we had more to eat. Father got a few cows and a small herd of sheep.

James and Annanettie Hatch Shumway, 1937. Photo courtesy of Ida Webb Collection, Taylor Museum.

James and Annanettie Hatch Shumway, 1937. Photo courtesy of Ida Webb Collection, Taylor Museum.

My baby sister being several years younger than myself made it necessary for me to work and play with my brother just older. We were especially good pals. One of our tasks was to care for the sheep. One cold winter day, a wildcat frightened the sheep, scattering them, then what a time we had, wading in the snow to gather them before night. On reaching home, I sat down by the fireplace to warm my feet, which by this time did not feel as cold as when out in the woods. I immediately began to remove my shoes and stockings knit from woolen yarn. To my surprise, some of the skin from my feet came off with the stockings. Frozen, yes, and for three weeks or more Brother Bert had the task of the sheep by his own lonesome self.

There was other outdoor work that I could do to help, and it made me happy, such as strip the cane and feed the molasses mill when my brothers were too busy doing other things. Father owned and operated a mill, making molasses for the neighborhood. One time the boys overdid the thing and cooked a boiler of juice to candy. Then what a jolly good time we had with a hayrack load of boys and girls coming from town to the candy pull.

Besides the outdoor duties, I could help my mother to provide light by making candles, also by making lye soap, brooms, and other things the pioneers had to provide for themselves. Our house was of logs, two rooms, not much furniture. At that time most of our evenings as a family were spent at home. These to me were happy times. Mother was a gifted singer so some evenings we would sing hymns and old-time songs, sometimes scripture reading and games. One game was called The Game of Authors. This was of cards with the pictures and names of authors such as Henry Ward Beecher, Nathaniel Hawthorne, John Quincy Adams, Harriet Elisabeth [Beecher] Stowe, Longfellow, Dickens, and others. This was instructive as well as entertaining. We made rag carpets, and in them Mother contrived to have a number of bright colors, obtained from berries, roots, and bark. Our curtains were kept clean and fresh so all in all it was anything but drab and dull.

I attended school for several terms. Our school terms were short, and it was necessary that even the children help in every possible way in the settlement of this new country. Their schooling of necessity was meager. Later, I attended the dances and other social affairs of the community.

As young folks at that time we had a lot of good wholesome fun and frolic. True, no cars to ride in; we were in luck to find a wagon. Then when luck prevailed we would go riding. We generally had four spring seats with four couples. Perhaps the boys would sing to entertain, then maybe the girls, then again if we all knew a certain song we would have a chorus together.

I soon was attracted toward my boy friend, James J. Shumway, and after a year or more of courtship we were married December 9, 1887. Arizona has always been our homeland; we have had a large family, eight boys and six girls. Two of the girls died in infancy, twelve living to adulthood.[57] The passing of one son who was killed on June 2, 1933, in the Richfield Oil Plant at Long Beach, California, was one of the greatest sorrows of our lives, being doubly so as he left a dear little wife and six small children.[58]

We had two sons enlist in the World War. One was overseas in the midst of the battle, coming home to us unhurt. The other was released from Camp Funston, Kansas, just ready to leave for overseas when the armistice was signed.[59]

Through much sacrifice and hard work we were able to educate this family, all getting three or four years in high school, five of them into college, four going through college, and being teachers in prominent schools. We have forty-six grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

Ellis and Boone:

James and Nettie Shumway lived to celebrate their golden wedding anniversary. The following story was told by their son Ernest at that celebration. The story was really about his father, but it undoubtedly describes the home that Nettie made for her children:

Father had always taken much interest in young people, especially in their sports. He had always been willing to take his car and his boys to athletic competition. He, however, has been strictly opposed to Sunday sports and games and had adhered to his early training of keeping the Sabbath Day holy. I well remember one time when Taylor baseball team scheduled a game with Holbrook on Sunday. Taylor did not have a chance of winning the game without the services of three of Father’s boys. He was opposed, did not want to take his car and go along, yet he just couldn’t miss a game like this when his boys were taking such a prominent part, but still resisted and said we could not take the car and he was very much opposed to his boys playing ball on Sunday. These three boys were grown men and, of course, Father could not keep them from going, so finally said, “If you fellows want to go to Hell, I guess I had better go along to look after you.” We went, Father went, and we won the game.[60]

Maria Annanettie Hatch Shumway died on November 18, 1945, and is buried in Taylor, Arizona.

Maria Janette Averett Shumway

Blanche Shumway Hansen

Maiden Name: Janette Maria Averett[61]

Birth: March 20, 1859; Ephraim, Sanpete Co., Utah

Parents: Elijah Averett and Johanna Christene Nielsen/

Marriage: Wilson Glen Shumway;[62] May 28, 1876

Children: Wilson Averett (1877),[63] Wallace Everett (1879), Clarence (1881), Louisa (1883), Elijah Gill (1886), Christine (1888), Albert Minnerly (1891), Louisa (1893), Blanche (1895), Coral (1901)

Death: July 22, 1924; Linden, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Shumway, Navajo Co., Arizona

My mother, Maria Janette Averett, was born March 20, 1859, at Ephraim, Utah. She was the daughter of Elijah Averett and Johanna Christene Neilsen.