R

Roberta Flake Clayton, Avis Laverne Leavitt Rogers, and Louesa Bee Harpers, "R," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 569-620.

Mary Ann Cheshire Ramsay

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP

Maiden Name: Mary Ann Cheshire

Birth: August 28, 1841; Kensworth, Durham, England

Parents: George Cheshire and Elizabeth Phoebe Keys

Marriage: Ralph Ramsay; August 2, 1869

Children: Marian Cheshire (1871), Joseph Cheshire (1872), John Cheshire (1874), George Cheshire (1876), Rose Ann (1878), stillborn son (1880), Ralph Cheshire (1883)

Death: November 5, 1923; Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

“Well, Father, now that we have reached our destination and the long tiresome trip almost across America is over, I suppose our traveling days will end and we will not have any more use for the faithful old oxen that have hauled all our earthly possessions from Missouri River to here, so we might as well trade them off for something we need worse.” So observed Mary Ann Cheshire to her father shortly after the family’s arrival in Salt Lake City, Utah, October 4, 1863.

Mary Ann was born in Kensworth, England, August 28, 1841, the oldest child of George and Elizabeth Keys Cheshire. For generations, her family had resided in that vicinity and by honest toil and strictest economy had eked out a living. Eight children were born to this worthy couple, and as each child became old enough, he or she had to share in responsibilities.

As Mary Ann was a delicate child and could not receive the necessary attention because of the arrival of the other children, she was taken into the home of an uncle and aunt who had no children, and they loved and cared for her as their own.

Being of a very independent disposition, Mary Ann could not remain idle and accept their kindness, so at the age of fourteen she began learning the millinery trade. At eighteen, she went to Luten, a larger town about six miles from her home, where there was a greater demand for the work she had now become quite proficient in. Here she rented a room, and as she went to the shop in the morning she would take her food to the bakery to be cooked for her, getting it on her return from work.

Every shilling she could spare was carefully hoarded, as was that of her family, for now George Cheshire and all his household were members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and the desire to go to America was the greatest object of their lives. Whenever Mary Ann went home, stock was taken of the savings contributed by each one, but there were so many mouths to be fed, occasional sickness, and other unlooked for expenditure beside the large amount needed for the voyage across the broad Atlantic and the unknown expenses after their arrival in New York and until they should reach “the Valleys of the Mountains” that their dreams were delayed from year to year. Hope and determination never wavered, however, and at last when she was twenty-one years of age, Mary Ann became the “fairy godmother” and supplied the deficiency in their joint bank account for the long dreamed of journey, with the money bequeathed her upon the death of her uncle, her aunt having died a few years previously.

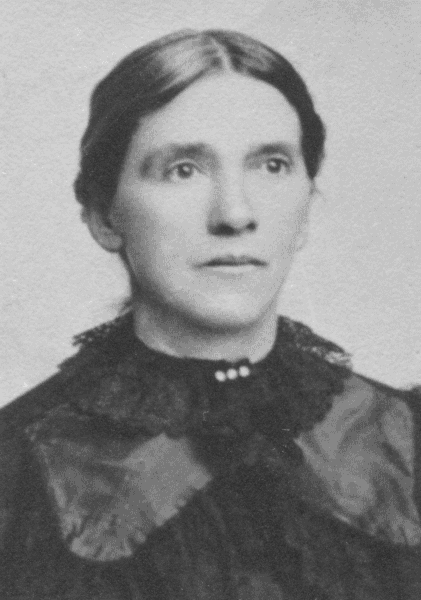

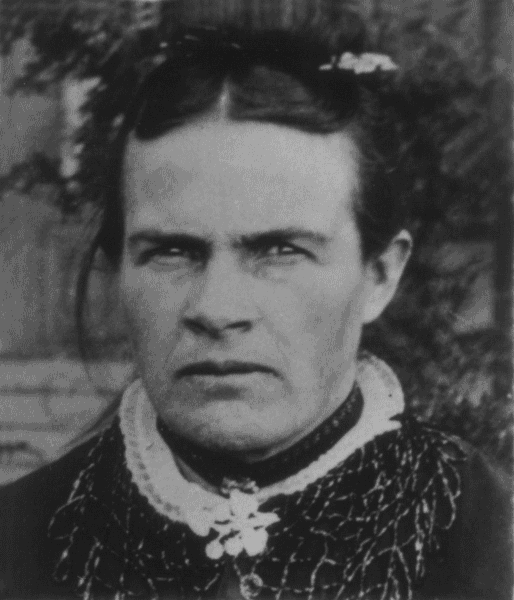

Mary Ann Cheshire Ramsay wearing a hat she presumably made for herself. Photo courtesy of Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

Mary Ann Cheshire Ramsay wearing a hat she presumably made for herself. Photo courtesy of Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

On June 4, 1863, all of her family but the eldest son, who was in the army, set sail from their beloved England for the New World.[1] Only the most necessary of their belongings could be taken, and there was many a heartache at the giving up of things so dear to them, and the relatives and friends whom they should never see again. America was a long way off in those days.

Of course, steerage passage was all that could be thought of because they did not know what they might meet before another home should be established, and the money saved by the family was gotten at too great a sacrifice to be spent unnecessarily. Besides, would not the steerage passengers get there as soon as the others?[2]

An ox team and covered wagon were obtained in Missouri, and with them the family journeyed westward. But one wagon for nine people and their belongings doesn’t provide much comfort, so Mary Ann rode part of the way on a threshing machine that was being brought to Salt Lake, and part of the time she walked. Her twenty-second birthday was spent on “the Plains.”[3]

Father Cheshire recognized his daughter’s business ability, so he readily consented to her suggestion that they trade off their oxen and wagon. For the latter, she got a cook stove, and the oxen almost paid for a city lot. As the legacy had all been spent by now, Mary Ann went out to work to earn enough to pay off the balance, and the treasured lot remained in her family many years. There her two oldest children were born.

Shortly after their arrival, Mary Ann established a shop and began making hats. She gathered wheat and oat straw, braided it and made the hats, then trimmed them with flowers also made of straw. If the hat was to be white, it was put into a box or barrel after it was shaped, and then [she] bleached it with sulphur fumes. If it was to be black or colored, dyes from roots and barks were used.

Her trade grew to such dimensions that before long she had six girls working for her. Hats of every shape and design were made by her, and many of the samples she had kept served in after years in fancy dress balls, home dramatics, and character pageants.

At the age of twenty-eight, Mary Ann Cheshire was united in marriage to Ralph Ramsay, but she kept up the millinery business and established a store on Main Street.[4] This venture was also successful, but after their two oldest children were born, her husband became restless and moved to several places, even down into Mexico before they finally settled in Snowflake, Arizona, in 1891, where they spent the remainder of their lives. They had lived in St. Johns for a while previously.

Mr. Ramsay was an artisan of rare skill. Wood carving was his avocation, though he was a first-class cabinet maker. He carved the eagle [on the famed Eagle Gate] that spans the principal street in Salt Lake City, the Lion and the Beehive that give to each of two noted buildings its name, and a bedstead of very intricate design that may be seen among the relics and curios at the Utah State Capitol building.[5] In Snowflake, on the three-story home of James M. Flake is a very realistic horse head surrounded by a horseshoe that he carved. Many ceiling pieces and mantels in homes in Snowflake are works of his hand, also mirror frames, hall trees, etc.

Both Mr. Ramsay and his wife being from England, and both artists in their line, their home was one of refinement and beauty. Seven children were born to them, five boys and two girls. All of them have families of their own except the eldest daughter who died in infancy and a baby boy born in a wagon during one of their frequent moves and who did not survive the exposure.

Sensing the need of nurses among the pioneering families, Mrs. Ramsay returned to Salt Lake City in 1886 and took a course in obstetrics. She served as a midwife for over forty years, assisting hundreds of babies into the world. Once when asked the exact number, her black eyes danced as she answered, “Oh, I don’t know; haven’t had time to count.” Her “territory” extended for more than a hundred miles and fortunate was the woman who could engage her services. She went calmly and efficiently about her tasks, no matter what the complications—never lost her head, seldom had a doctor in attendance, and in all her practice only lost one case. Indian and Mexican women were also among her patients.

Her services were much sought after in all classes of sickness because of her knowledge of human anatomy and also of the herbs that nature has provided for the cure of the ailments of her children. Small in stature, one wondered at her strength and endurance. Always dressed immaculately and in excellent taste, she was easily the best dressed woman in Snowflake, especially as long as her “black silk alpaca” lasted.

Never ruffled, never hurried, with a motto, “Oh, things are never so bad but what they might be worse,” she was always a welcome guest.

Her husband died January 25, 1905, and she departed this life November 5, 1923. Appropriate funeral services and burial was given to each. They are gone, but the memory of their unselfish service to humanity is cherished by all who know them.

Ellis and Boone:

Recognizing the service Ramsay gave to the community of Snowflake rather than remembering the acrimony of divorce, Clayton wrote this sketch in the 1930s for her former mother-in-law. RFC married Mary Ann’s oldest son, Joseph, in 1896; they were divorced about 1904 while living in New Mexico, with some rancor but mostly recognizing their differences.[6]

Because this was originally an FWP sketch, the subject of polygamy is not mentioned. Mary Ann was Ralph Ramsay’s fifth wife. In 1880, Ralph and two of his wives traveled to Arizona, settling in St. Johns.[7] The move to Mexico mentioned in this sketch was directly related to polygamy, but the families returned to Arizona in 1887 and settled in Snowflake in 1891.

Both of Ralph Ramsay’s wives who came to Arizona were midwives. Granddaughter Norma Baldwin Ricketts wrote, “Both wives were busy assisting at births. At first the fee was $3 which included two visits a day for ten days to care for the mother and child after delivery. Several years later the fee had increased to $5, sometimes as high as $10. (A great grandson, Jarvis Jennings, remembers his father telling him that he gave Grandma Ramsay a ten dollar gold-piece to assist at the birth of his first son.) No one was ever refused for want of money.”[8]

Ruth Campkin Randall

Roberta Flake Clayton

Maiden Name: Ruth Campkin

Birth: January 2, 1845; St. Louis, St. Louis Co., Missouri

Parents: George Campkin and Elizabeth Bell

Marriage: Alfred Jason Randall; November 16, 1867

Children: Annie Elizabeth (1868), Alfred Bradley (1870), Emerette (1872), George Campkin (1874), Walter John (1875), Frank Campkin (1879), Bert Davis (1882), Harry Jason (1884), Howard L. (1887)

Death: April 26, 1929; Pine, Gila Co., Arizona

Burial: Pine, Gila Co., Arizona

The Campkins were emigrants from England in 1844.[9] George Campkin and his wife Elizabeth Bell were on a boat, in the Mississippi River, docked at St. Louis, Missouri, when a wee baby girl was born to them, January 2, 1845. They named her Ruth. Her father was an expert shoemaker and plied this trade for a living. In 1850 the family immigrated to Utah, traveling in an emigrant train of Mormon Pioneers. Ruth grew up in Salt Lake City, and what schooling she had was obtained there.

A little story of Ruth’s courtship was found in an old letter that Alfred Jason Randall sent to her, probably as he was on a freighting trip hauling machinery from Kansas to Salt Lake City for his father’s woolen mill.[10] He wrote thus:

I know that I could give you

The love that should be thine

And for that reason I would

Make you a wife of mine;

If you will only say the word

I’ll make you my valentine.

In another letter, written later, he ended it this way: “If I live and keep my health, and the Lord is willing and the devil don’t care, and the Indians don’t get my scalp and father doesn’t raise any objection and I have a pony I will see you.” Evidently things were favorable to this union.

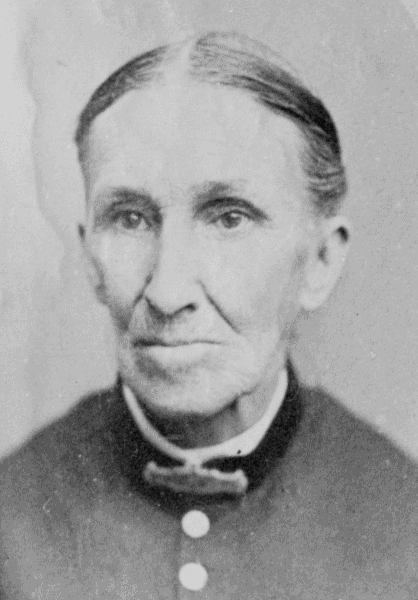

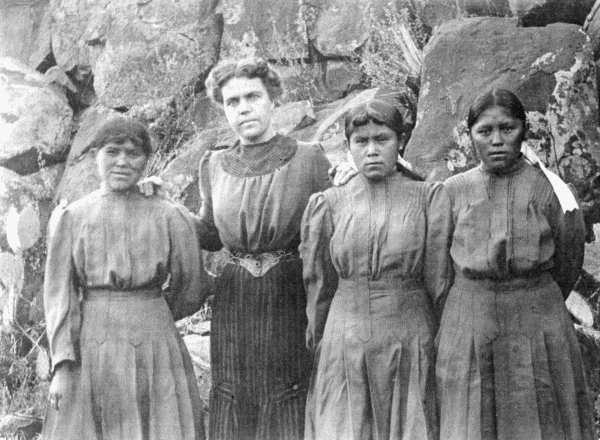

Ruth Campkin Randall at the time of her marriage. Photo courtesy of Maurine Heisdorffer.

Ruth Campkin Randall at the time of her marriage. Photo courtesy of Maurine Heisdorffer.

Ruth was twenty-two years old when she married Alfred Jason Randall on November 16, 1867. Her older sister Annie was married November 9, 1867, to Wyllys Darwin Fuller, a close associate and a friend of Alfred’s. These two young men had been called to go to help in the settlement of southern Utah.

Soon after their marriage, preparations were made to take these brides with them to the outpost of civilization, a barren, Indian-infested country. Imagine what a honeymoon trip that would be. What courage and loyalty to a church and its leaders they manifested.

The Randalls settled at Harrisburg, Washington County, Utah, arriving there Christmas Day 1867. They lived there fourteen years, and six children were born to them. An infant son was buried there.[11] The Randalls had bought a larger home in Washington and had lived in it but a short time when they received a call to go to the Tonto Basin, Arizona.

In September 1881, they were on their way traveling to another isolated frontier. The trail led them up a gradual incline until they reached the top of the mountains; then it suddenly dropped over the rim several thousand feet into a narrow valley. The road was narrow, rocky, and steep. A tree was chained to the wagon to drag as a brake. As Ruth and her children stood looking down the road, she said to them, “I think your father is taking us into Hell.”

They made the descent successfully, and that first winter they lived in a small log room that had been a blacksmith shop. They used covered wagon boxes for bedrooms.

Three children were born to Ruth in Pine.[12] She helped care for her sister’s five children until they were grown, their mother having died when they were all young.[13] Wyllys (Wid) Fuller, their father, moved from Utah to Pine when the Randalls did.

As a safeguard from the Indians or other enemies, there was a stockade built by setting deep into the ground heavy slabs of timber on end close together in a circle with only one entrance. When an Indian raid was reported, all the residents were to get into this enclosure for protection. Once a call came for all to go to the fort, as it was called. Ruth said, “No, I have been dragged from pillar to post and from the post to hell and I am not going to the fort. I’m staying right here.”

This area was traversed often by a number of Indian tribes, and they were not always at peace among themselves. It was also in the path of [a] trail leading to Phoenix, where often the warring factions of the Tewksbury and Graham clans would travel.[14]

Ruth Campkin Randall (left) and another sister, Sarah "Sadie" Campkin Evans. Photo courtesy of Robert Fuller.

Ruth Campkin Randall (left) and another sister, Sarah "Sadie" Campkin Evans. Photo courtesy of Robert Fuller.

The Randalls were hospitable to strangers who came to their door asking for food or lodging. They never asked their visitors who they were.[15] They were generous in sharing and helping the poor and unfortunate any time.

While Ruth was on a trip to Tuba City with her husband and small son Howard, they camped for the night with their bed on the ground. One night Ruth’s hand was bitten by a prowling skunk. They were fearful the animal might be rabid. They had seen the death of a friend from hydrophobia who had been treated with a madstone.[16] They hastened their journey to Flagstaff; here Ruth boarded the train for Chicago, the nearest place she could get treatment.

After that experience, their camp beds were protected from prowling animals by skunk boats made by driving pegs around the bed and fastening the bed tarp so as to make a fence of the canvas around the bed.

Mabel Randall Shumway describes her grandmother Ruth Campkin Randall as follows:

She was the tiniest, wittiest, and most independent little person in the world. She combed her dark brown hair (streaked with grey) parted in the middle with a braided or twisted bun at the back. She never weighed 100 pounds and was hardly five feet tall. Her snappy brown eyes were full of laughter. She wore dark-colored dresses, gray or black (when I knew her), and always an apron and when outside, a bonnet. For dress-up she had a black velvet cape and a beautiful beaded one. As she sat in her home by the fireplace, in her last years, she most always had a little knit shawl across her shoulders and a cat in her lap.

Her home was kept neat and clean. Her delicious bread and jelly or cake that she always had ready for us kids tasted better than anything I can remember. I loved to skip into her parlor and play the piano; it was the first and only one in Pine for many years. What a thrill I got when she showed me her trinkets in an old trunk. A little pair of stockings she knitted for my father while she jolted over the road to Arizona was one of her keepsakes. Her stories were fascinating and full of her witty and original expressions. She was very outspoken, but she always spoke the truth.

She was addressed as “Aunt Ruth” by her friends and acquaintances. An old friend who was from Dixie, Frances Adair Peach, known as “Ma Peach,” who lived in Strawberry, always called in when in Pine to visit with Ruth.[17] Mrs. Goodfellow was another good friend who always came in when up from the Natural Bridge.[18]

Ruth was a good housewife and mother, supporting her husband in his public works in the Church and community but not holding positions herself. She taught her children the gospel and had a testimony of its truthfulness.

She was fond of pets, especially cats; two favorites she named “Mert” and “Tort.” Many of the grandchildren will remember [that] Mert was always curled up on her chair ready to lay on her lap and be stroked. She also liked dogs. She enjoyed parties and dances and danced with her sons at seventy-five years of age. In her last years, she could read without glasses. Often one of her granddaughters would spend the night with her if she was alone, and checker playing was her favorite game.

The accidental death of her husband in 1907 at Willow Valley, Coconino Co., Arizona, and the death of her son Harry in 1908 were too much for her, and she requested that her son Howard be released from his mission in the Society Islands.[19] She had her oldest son Fred move his family to Pine to help care for the cattle and be a comfort to her. After Howard married, three years later, he and his wife lived with her for four years. When they moved away, her daughter Emma came back to Pine and cared for her mother until she died.

Ruth was fearful that she might be a burden in her last years. Her fatal illness was short, and she waited upon herself almost to the last day. Her children were all at her bedside when she passed away April 26, 1929. Apparently, her death was as she had always wished it to be. She was a widow for twenty-two years. Surely she has lived nobly and left a posterity to bless her name; she has sixty-six grandchildren.

Ellis and Boone:

Although RFC submitted a short biography of Ruth Campkin Randall to the FWP on September 13, 1937, the sketch here is completely different. With the FWP account and modern databases, more information should be included on the two pioneer journeys, from England to Utah and from Utah to Arizona.

The Campkin family (parents and three children) were part of the first company of Saints to emigrate from England after the martyrdom of the Prophet Joseph Smith. They traveled aboard the ship Norfolk, leaving Liverpool September 19 and arriving in New Orleans on November 11, 1844. The Millennial Star described this voyage, which included 143 Latter-day Saints: “We rejoice to see so practical an illustration of the faith of the Saints being unshaken by the late tragical [sic] events in the West, and that the Saints are not living according to the precepts of men, but the word of God.”[20] The FWP sketch states that they “went up the Mississippi [from St. Louis] on a steam boat as far as Kanesville, Iowa, the outfitting post of the pioneers.[21] Here they obtained two yoke of oxen, one yoke of cows, and a prairie schooner.”[22] MPOT lists the Campkin family as traveling to Utah in 1850, company unknown; this is not from information in PWA but is circumstantial evidence from the 1850 census and the death of one child (Mary) and birth of another (Elizabeth).

Finally, when grandchildren were writing about Alfred and Ruth Randall, they included more information about the move to Arizona. Two granddaughters wrote:

In 1877 Alfred was directed, in company with five other men, to explore Arizona, in particular the Tonto Basin. This was the first of four trips he made before finally moving his family in 1881. On his second trip he moved his cattle to the Tonto Basin area. In January 1879 he helped his brother-in-law, Wid Fuller, move his cattle down. At Lee’s Ferry the Colorado River was frozen over, so the cattle crossed on the ice. It was on this trip that he and Rial Allen bought squatters’ rights to Pine from [Henry] Siddles and [William] Burch for $300.[23] In March of 1881, Alfred, Wid, and Dave Fuller made another trip to Pine in a light wagon. About 60 miles north of Pine they were snowed in for ten days. Their food supplies ran low and they were forced to kill a cow for food and use the hide for shelter. In June he returned to Utah to bring his family to Pine.[24]

Then a grandson gave this detailed list (from his father, who was eleven years old at the time of the journey) illustrating the route the family took from Utah to Pine: “Pine [Pipe?] Spring, Kanab, House Rock, Pooles, Soap Creek, Lee’s Ferry, Navajo, Bitter and Willow Springs, up the Little Colorado River by Black and Grand Falls, Winslow, Sunset, Mt. Jarvis Pass, Antelope Tank, Long Valley, Potato Valley, Baker’s Butte, Seven-mile Tank, Nash Point, up Strawberry Valley to Pine.” He also states that the family arrived on October 23, 1881.[25]

Both Alfred and Ruth Randall are buried in the Pine Cemetery, in a little town that they helped to create.

Susan Temperance Allen Randall

Author Unknown

Maiden Name: Susan Temperance “Tempy” Allen

Birth: January 24, 1871; Washington, Washington Co., Utah

Parents: Rial Allen and Susan Elizabeth Collins

Marriage: Alfred Bradley “Fred” Randall;[26] September 28, 1891

Children: Alfred Harvey (1892), Della (1895), Ruth (1897), Rial Melvin (1899), Pearl (1902), James Leslie (1904), Grace (1905), May (c. 1908), Ivy (1911)[27]

Death: January 29, 1941; Holbrook, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Joseph City, Navajo Co., Arizona

Tempy Allen, the name she was known by, was about five feet, five inches tall. She was a beautiful, attractive girl with blue eyes and blond wavy hair which in later life turned to a lovely silver gray. She had very good taste in choosing her wearing apparel. She always looked richly dressed; lavender was her favorite color, which she wore becomingly. She was a good seamstress. She made nice clothes for her daughters, was a good cook and homemaker. She had a dignified bearing, ladylike manners, and a kind, gentle disposition.

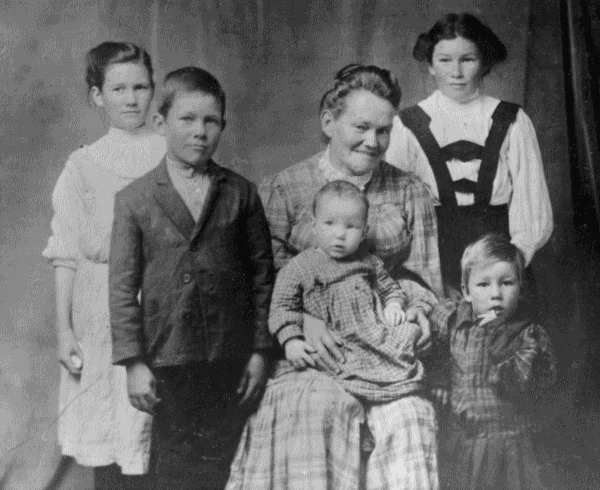

Tempy Randall with children, Harvey, Ruth, and Della; Ruth and Della died shortly after this photograph was taken. Photo courtesy of Wayne Standage Jr./ Dilworth Brinton Jr.

Tempy Randall with children, Harvey, Ruth, and Della; Ruth and Della died shortly after this photograph was taken. Photo courtesy of Wayne Standage Jr./ Dilworth Brinton Jr.

The Rial Allen family lived in Southern Utah when their daughter Susan Temperance was born. She was always called Tempy. When she was seven years old, her parents moved to Pine, Arizona, in Yavapai County, now known as Gila County. Their home in Pine, Arizona, was a log house built by her father. Tempy had two brothers and six sisters.

Her first schooling was in Pine and was taught by Mary Allen, the wife of her father’s cousin Marion.[28] When nineteen years old she went to Snowflake and attended the Academy the winter of 1889−90. She lived in Snowflake with Jane Freeman, her father’s sister.

The next September 1891, she married Alfred Bradley Randall, known as Fred. They moved that fall with her parents to Tuba City, Arizona, which is ninety miles north of Flagstaff. Tempy’s father had given her a horse and sidesaddle, which she rode on this trip, helping her husband drive about thirty head of brood mares, with mule colts. Her father turned his horses out on the range around Tuba City, and the Indians drove them off to Navajo Mountain, and the Allens never saw them again.

Tempy had some stock with a brand of her own at Pine; she sold them to her husband’s mother. About six miles west of Tuba City, Fred and the Allens bought a farm. This ranch was called Moenava. Tempy and Fred lived in a two-room adobe house, later moving to a two-story frame building called the Bates home. Tempy was afraid of Indians; she had a good neighbor, Susan Foutz, who always came to her rescue should she see Indians around Tempy’s house when she was alone.[29]

They made the trip to St. George to the temple in a light wagon and a mule team, which took a month’s time. They belonged to the Tuba City Ward.

Tempy lived in Tuba City while her husband was away on a mission to Texas. She had three children; a daughter, Della, had died before her husband left for the mission field. She had Harvey, her oldest son, and her little daughter, Ruth, and then Rial Melvin was born soon after his father departed for his mission.[30] Ruth died of a kidney infection January 2, 1902. This great sorrow brought her husband home from his mission. Another infant daughter, Pearl, died in 1903; all three children were buried in Tuba City.

Tempy often spoke of the help Fred Tanner [her brother-in-law] rendered during her husband’s absence.[31] Sometime after the death of Tempy’s mother in 1895, her younger sister, Lottie, came to live with them and stayed for about eight years. Their father died in 1889.

Fred [Randall] moved his family to St. Joseph (Joseph City) in March 1903. Here an infant son, James Leslie, passed away. Three more daughters came to their home. Five children grew to maturity. Except for two years’ residence in Pine from 1908 to 1910, the remainder of her life was spent in Joseph City.

Tempy had poor health the latter part of her life; her husband did everything possible to make her life pleasant and happy. At her sudden death, he could hardly be reconciled. This occurred in the hospital in Holbrook, January 29, 1941.

Ellis and Boone:

Two short sketches of Alfred Bradley Randall mention the Randall family moving to Tuba City, “where they lived until the government bought the holdings of the Mormon settlers.”[32] Tanner and Richards give a brief history of Latter-day Saint settlement at Tuba City, an area which was a natural halfway station between Lee’s Ferry and the settlements on the Little Colorado River. Originally, the Hopi chief, Tuba, gave permission for Mormon settlement, but from the beginning, there was tension between Anglos and American Indians. Eventually, the Hopis discouraged further settlement, saying, “The water is scarce in our country for our numerous flocks and increasing people, and our good men do not want your people to build any more houses by the springs. But we want to live by you as friends.”[33] This was the area that Lot Smith moved to after the abandonment of Sunset, and where he was killed after a disagreement with Navajos in 1892.

The Mormon population of Tuba City and Moenave increased as people like the Allens and Randalls moved to the area. In 1886 there were 156 Mormons; in 1889 this number rose to 229; in 1890 it was 286; and by 1893 there were 305 Latter-day Saints. These numbers then fell, and the population was down to 149 in 1900. Tanner and Richards describe the demise of the Tuba City Ward, writing, “In 1900 the federal government took over control of the area in order to establish reservations for the Indians, and the Mormons who had only squatters’ rights were required to leave. After much negotiation, the government appropriated $48,000 to the Mormons as compensation. By late 1903 all the Mormon residents had moved to other localities.”[34] Then they gave a list of nineteen individuals or couples who received compensation, stating that “older residents of Joseph City will recognize many of these families. At least five lived in Joseph City [including Fred and Tempy Randall], and other[s] lived in wards of the Snowflake Stake [mainly Woodruff and Holbrook].”[35] Another important relocation site was the Fruitland area of San Juan County, New Mexico, where five families moved, including Anna Elese Schmutz Hunt (288). By 1910, families from Tuba City were living in Bluff, San Juan Co., Utah; Alamo, Lincoln Co., Nevada; Fruitland, San Juan Co., New Mexico; and Joseph City, Holbrook, Woodruff, and Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona.[36] It is interesting to note that these people generally moved to areas on the periphery of the Navajo Reservation; they did not move to Show Low and Springerville, but instead they moved to Joseph City, Holbrook, and Woodruff.

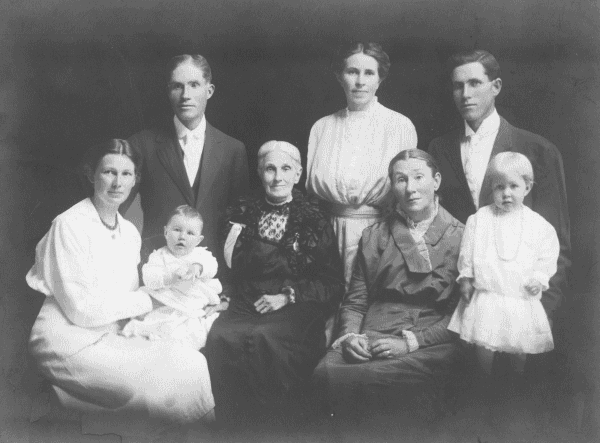

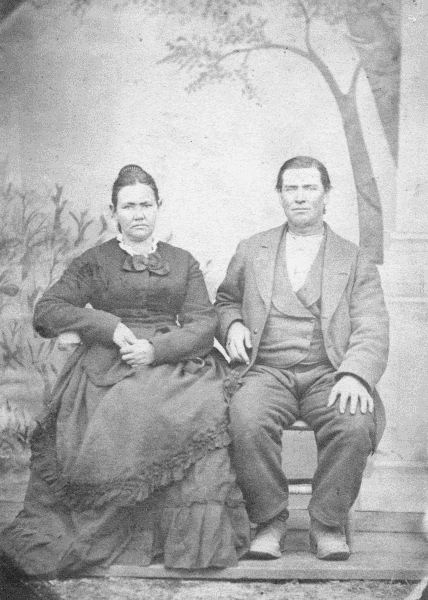

Tempy Randall (center) with her husband's family (left to right): Walter and Martha Florence Randall, Alfred and Tempy Randall, Frank and Lucinda Randall, Bert Randall. Photo courtesy of Maurine Heisodrffer.

Tempy Randall (center) with her husband's family (left to right): Walter and Martha Florence Randall, Alfred and Tempy Randall, Frank and Lucinda Randall, Bert Randall. Photo courtesy of Maurine Heisodrffer.

Tanner and Richards summarized the settlement at Moenkopi this way: “Tuba City was the first of the Arizona Mormon communities to complete a building, to clear land and plant crops, and to build a dam to irrigate their fields. While not the first to lose a dam, they had experience with dam losses too. The supreme distinction to which Tuba City should be entitled was its attempt to convert the Indians and do them good. That they failed largely in this was not due to lack of an honest desire, but to their methods and lack of long-term patience.”[37] Actually, much of this concern for Native Americans moved with these people to their new locations. Fred Tanner “spoke the Hopi language and enjoyed his association with the Indians” in part because he was postmaster in Tuba City and “knew everyone in the area.”[38] A descendant of William and Elese Hunt today makes his living at Waterflow trading with both Navajo and Anglo residents. James L. Allen, besides living at Tuba City, also lived at Keams Canyon and “while there he learned the Navajo language and acted as an interpreter.”[39] Finally, Fred Randall “became acquainted with the ways and languages of the Indians and understood them better than most people did. All of his children have been interested in Indian welfare. The Indians called him ‘Hosteen Yazzie.’”[40] The time that Latter-day Saints spent in Tuba City influenced relations between Native Americans and Mormons for generations.

Mary Sutton Pettit Willie Richards

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP Interview[41]

Maiden Name: Mary Sutton Pettit Willie

Birth: May 31, 1850; Salt Lake City, Salt Lake Co., Utah

Parents: James Grey Willie[42] and Elizabeth Ann Pettit

Marriage: Joseph Hill Richards;[43] November 30, 1867

Children: Joseph Parley (1869), James Willie (1871), John Ezra (1873), Emma Elizabeth (1876), Mary Amelia (1879), Hyrum Enos (1881), Anna Belle (1883), George Elmer (1885), Lettie Pearl (1889)

Death: June 2, 1941; Joseph City, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Joseph City, Navajo Co., Arizona

When the pioneers were immigrating to Utah, many modes of conveyance were employed to bring their few belongings across the plains. The “prairie schooners,” covered wagons drawn by horses, mules, and oxen, were the most successful method, and, for those who had lived in the east and had owned these animals on their farms or could trade some of their possessions for them, the cheapest. But for the emigrants from the old country, it was too expensive [to purchase covered wagons and teams], so handcarts were made to be drawn and pushed by two people, which could carry all the luggage brought with them.[44] At best, these journeys were never pleasure trips. They were begun by easy stages, and, as the people got more used to walking, longer distances between camps were the result.

We are considering in this sketch the life of Mary Willie Richards, and it so happened that her father James G. Willie was the captain of the most ill-fated of these companies.[45] He had been a missionary for his church in England for four years and on his return home was called to take charge of a company of over five hundred converts from Europe to America. It was late in the season when they started, and the company suffered untold misery from snow, cold, and hunger. Mary well remembers when her father arrived with his feet wrapped in sacks and then they were badly frozen. There were very few of that ill-fated company but lost toes, fingers, and even limbs.[46]

She was born May 31, 1850, in Salt Lake City, the second in a family of five born to her mother, Elizabeth Ann Pettit. When Mary was nine years old, her father moved to Mendon, a small town in Cache Valley, Utah, and there she grew up. She had very little schooling as three or four months in the middle of the winter was as long as school kept in these early days, but her education was not confined to the schoolroom. She learned to do many things that would later help her to be a competent wife, mother, and pioneer.

First thing in the morning, she helped milk the cows. Then out came the spinning wheel, and four skeins of yarn was Mary’s task each day but Sunday, week in and week out. She did this in order that her mother would have plenty for weaving the cloth that was made into clothes for the family.

No matter how long or hard the tasks, love always finds a way, and because their homes were not far apart, Mary and Joseph Hill Richards were easy victims to love’s spell. Soon the young people developed a strong attachment to each other. Joseph was nine years older, but this was no hindrance to their love and devotion for each other, so on November 30, 1867, they were married in Salt Lake City, returning to Mendon, where they made their first home. They were in the midst of their family and were very happy. Three fine boys were born here.

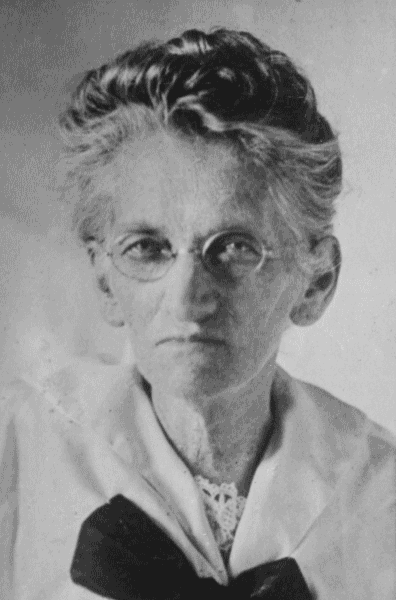

McClintock used this photograph of Mary Willie Richards for Mormon Settlement in Arizona. Photo courtesy of DUP album, Snowflake-Taylor Family History Center.

McClintock used this photograph of Mary Willie Richards for Mormon Settlement in Arizona. Photo courtesy of DUP album, Snowflake-Taylor Family History Center.

One day, like lightning from a clear sky, came a call for the little family to leave their happy home, their kindred and friends, and go out into the wilds of Arizona to help colonize. No matter what the sacrifice, nothing but death could prevent Joseph H. Richards and his wife, Mary, from answering this call.

Now all was hurry and bustle. The little home must be sold for whatever it would bring. Cash was scarce, so grain, flour, corn, and anything in the way of provisions would be taken, as each family was advised to have enough on hand to do them two years.

By February 8, 1876, they were ready and made a start on that long, perilous journey in the middle of the winter, leaving behind all that was dearest to them on earth. When they reached the Panguitch Divide, they found the snow two feet deep. They could travel only a few miles a day; then after the snow, it was deep mud. When the feed they brought was gone, their poor tired animals gave out, and the travelers must stop every little while for them to rest. For more than three months they toiled on the way but felt they were greatly blessed, for the Lord spared all their lives. On April 20, 1876, they arrived at the settlements on the Little Colorado River, the first companies having arrived the March before. Such a barren, desert-looking country they found! Not a tree for miles except an occasional cottonwood on the river.

There were four colonies or camps, as they were called: Lot Smith’s, Ballenger’s, Lake’s, and Allen’s camps. They were called after the man that presided over each. Later these places were named Sunset, Brigham City, Obed, and St. Joseph.[47] The Richards family lived first at Lake’s Camp or Obed. Immediately after arriving, they went into the United Order. Mary and her husband were very well fitted with provisions, cows, chickens, etc., and had they not turned all they possessed into the Order, would have been very well fixed for pioneers.

But some of the Saints were very poor indeed, yet all must, and did, share equally. The women took turns cooking and washing the dishes. Then there were washings to be done in wooden tubs on homemade washboards with soap they had made with lye, from cottonwood ashes. There were later great quantities of molasses to be made, as bread and molasses was their chief diet.

At first they all lived in tents and wagon boxes, with a large bowery where they met to hold religious services, and where they spread the long tables at which they all ate together. In this camp there were sixty men and twenty women, besides the children. Soon they began building homes of rock which was near and plentiful. Mary had the joy and honor of living in one of the very first houses with a roof. Nearly all the houses in early days had dirt roofs, but not this one. Philip Cardon, a member of the colony who emigrated from Italy, understood the art of “flat roofing,” fitting large flat stones together so they would shed the rain.[48] This was the kind of roof that sheltered the Richards family. Mary tells us that it was far superior to dirt, as the mud did not run through, and it did not leak, no matter how long it rained.

In those early days when there were no doctors or nurses to welcome the stork that made frequent visits in pioneer homes, some dear, kindhearted woman with a love for humanity and a little knowledge of the human body had to qualify in each community as a midwife. Mary began at the age of twenty-six and for fifty-two years served in that capacity, assisting in bringing hundreds of babies into the world, and in all that time she never lost a mother nor a child. With a prayer in her heart she went cheerfully about her task, be it day or night, hot weather or cold, and to this day she is held in love and esteem by all whom she so faithfully served.[49]

When her fourth baby was expected, their house was not finished, and the tent house was soaking wet because it had been raining almost constantly for two weeks. The men folks worked all night to get the roof on. Then they took the wet tent and hung it between her bed and the unplastered walls, and how happy she did feel! The baby arrived at dawn the next morning. The modern mother would be terror stricken in going through the ordeal of childbirth without doctor, midwife, or even a nurse; not so with our heroine. She sent for two neighbor women, one a girl just married and the other the mother of one baby. She told them what to do and they very tremblingly did it. Thus was born her first daughter, and first Arizona baby. She adds, “With all my nine children, I never got along better.”

There were many swamps near Obed, and when summer came almost the entire colony was stricken with malaria. It became so serious that the camp had to finally be abandoned. Some of the people went to the other camps, while others went to the southern part of the territory where there were two Mormon settlements. The Richards family moved across the river to Allen’s Camp. Here the fort was almost finished. The schoolhouse was completed and was used for all public gatherings. Every evening all who were able gathered in this large room for the singing of a hymn and a prayer, after which the men planned their work and the women visited. It was a real social center.

Joseph Richards was called as first bishop of the new St. Joseph Ward, and Mary was chosen as president of the Relief Society.[50] This position she held for seven years. In those days a bishop’s house was the free stopping place for all who might come. It was nothing uncommon for twenty or thirty people to be entertained at conference time, when they came by team for miles around and remained three or four days.

While Mary was nursing in this wilderness country, her husband was taking the place of doctor and dentist, setting all broken bones and pulling all the aching teeth. Mary’s time was so completely filled with the caring of the sick and entertaining the well that she was released from her position as president of the Relief Society and was put in as head teacher. This position she held for more than thirty years.

Mr. Richards was postmaster of St. Joseph for twenty-nine years, his busy wife doing as much of the work as he.

In 1891, Mary’s husband was called on a mission to England. He left his wife and nine children and gladly answered his call. He sailed on the S.S.Abyssinia. When about half way across the ocean, the ship, which was partly loaded with cotton, took fire. The passengers became panic stricken, but Elder Richards was calm and unafraid, for the Apostles who set him apart for his mission had promised him: “You shall go and come in safety.”

There was no wireless in those days, but just as it began to look very serious and hopeless, they sighted a German ship. They fired their signals of distress, and the German ship hastened to their rescue, and every passenger was taken aboard it. Before they were out of sight the Abyssinia sank. Elder Richards’ luggage was all burned and now must be replaced. He jokingly wrote his wife that they all went on a spree, meaning the German boat was named the Spree.[51] When he had been gone more than two years, their fifteen-year-old daughter, May, became seriously ill with typhoid fever. For three weary weeks the mother watched over her day and night, then May passed away, and it took a month for her husband to receive word of their daughter’s death. As the Apostle promised, Joseph reached home in safety, after being gone more than two and one half years.

On July 3, 1924, Mary was called upon to part with her dear companion. This trial, as her other trials, she bore bravely. Service is so much a part of her very life that she must continue it, so she turned to temple work. She has worked in the Salt Lake, Logan, St. George, and Arizona Temples.

What great reward must be waiting for one who has spent more than three quarters of a century doing for the “least of these.” When her mission here is finished, surely the Master will say, “WELL DONE THOU GOOD AND FAITHFUL SERVANT. ENTER INTO THE JOY OF THY REST.”[52] And “rest” to Mary Willie Richards will be “eternal serving.”

Mary Willie Richards, wife of Joseph Hill Richards, died at Joseph City on June 2, 1941.[53]

Ellis and Boone:

The importance of this couple to the development of Joseph City is readily apparent in the two histories of the town, Unflinching Courage and Colonization on the Little Colorado.[54] A story told by Alice Hansen illustrates:

Times were difficult in the newly established Little Colorado Settlements. The family of the midwife, who had been especially called to Arizona to serve the Obed colony, had early become discouraged and had gone back home to Utah. Mary and Joseph Richards had just arrived with three small sons and it was nearing the time when the arrival of a fourth child was expected. All the inexperienced young people of the colony turned to Mary. “You have had three babies,” they said. “We are expecting our first, you will have to help us.”

Fortunately, Mary Richard had brought with her a “Doctor Book.”[55] One of her first patients was a woman, thought to be dying, and this was at a time when Mary was very near her own confinement. With some trepidation, Mary took her big doctor book, said a prayer, “searched her brain for all the remedies she had ever heard about,” and the woman made a full recovery. Hansen concluded, “Mary Richards later served the entire area as a midwife, everyone learned to respect and have confidence in her administrations. She was blessed with unusual natural aptitudes as a nurse. Through the aid of her ‘doctor book’ and keen observation, she added to her knowledge and skill. When doctors came to Northern Arizona, they marveled at the success of Mary W. Richards as a midwife and at her uncanny skill in various arts of healing.”[56]

Anna Matilda Doolittle Rogers Rogers[57]

Unidentified Granddaughter

Maiden Name: Anna Matilda Doolittle

Birth: December 24, 1820; Wallingford, New Haven Co., Connecticut

Parents: John Doolittle and Ruth Ann Davis

Marriage 1: Amos Philemon Rogers; January 12, 1846

Children: Amanda Jane (1846)

Marriage 2: Samuel Hollister Rogers; March 7, 1850

Children: Amos (1851), Smith Doolittle (1852), Davis Samuel (1854), Sarah Matilda (1856), Chloe Ann (1859), Orpha Amelia (1861), Mary Malinda (1864)

Death: September 23, 1887; Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

My grandmother, Anna Matilda Rogers, was born December 24, 1820, at Wallingford, Connecticut. Her father, John Doolittle, was a mechanic and cabinet maker. Her mother, Ruth A. Davis was a small, lovable woman, a good homemaker, winning the love of her children and the respect of older folks.

Anna Matilda came from Wallingford, Connecticut, to Nauvoo, Illinois; then to the camps of the Saints: Sugar Creek; Garden Grove; Mount Pisgah; Council Bluffs, Iowa; Winter Quarters, Nebraska; and on west to Utah by ox team.

Anna Matilda Doolittle Rogers. Photo courtesy of DUP album, Snowflake-Taylor Family History Center.

Anna Matilda Doolittle Rogers. Photo courtesy of DUP album, Snowflake-Taylor Family History Center.

She was married to Amos Philemon Rogers on January 12, 1846, in the Nauvoo Temple by Brigham Young. After a short five months of marriage, she was left a widow. Her husband died June 26, 1846, following several weeks of illness. He was buried on the lonely mountain side at Mount Pisgah; his brother Samuel helped dig his grave.

At Council Bluffs, October 14, 1846, the brokenhearted widow became the mother of a baby girl, Amanda Jane, by name. The tiny one took a great deal of her time but helped to while away the lonely hours when on the plains.

In September of 1849, she reached the Salt Lake Valley with the help of her brother-in-law, Samuel, who met her and the baby and his sister, Sarah, the remaining ones of the family. Samuel helped them on the last lap of the trek.[58] This way of life was not easy.

She and Samuel, her deceased husband’s brother, were married in Salt Lake in 1850.[59] They stayed there but a year or so, and then they were called to Parowan, Utah. In Parowan, she and her husband built a comfortable home (which still stands in 1958) and raised seven children. They were active in both Church and civic affairs, and they did much temple work in the St. George Temple.

She was a homemaker in every way. Her home duties were her first and last consideration. Gossiping had no place in her busy, active life. She was a hard worker and particular with everything she undertook to do. She did all the spinning, weaving, and sewing for her family and even made the cloth for the menfolks’ suits. She cut them out and tailored them herself. Everything she did, she did well.

Her home was a place for family and community entertainment. Their home was open to all young folks, and she and her husband encouraged home parties and dances. She was never too busy to teach her children the principles of the gospel by word and example. She was quiet, firm, and understanding of the needs and interests of her children. All her family honored and respected her, and her teachings were ever a guide to them.

They were called to help colonize Arizona, and they reached Snowflake January 8, 1880. She was fifty-nine years old at that time. She passed away in Snowflake on September 23, 1887, at the age of sixty-seven years. Jesse N. Smith says of her, “I don’t know of any one person that could do so many things as Matilda Rogers did. She could do anything.” Aunt Ellen Smith says of her, “There wasn’t anything she could not do such as sewing, weaving, spinning, cooking, and other arts of pioneering.”

Ellis and Boone:

Most of the years Anna Matilda Doolittle Rogers spent raising her children were in Parowan, Iron Co., Utah. Parowan was originally established to support the Iron Mission, and the town celebrates its founding as January 13, 1851. Samuel H. Rogers did not bring his family to Parowan until 1853 and was not considered an iron missionary. Nevertheless, he became a leading figure in Parowan for twenty-five years. Because many of the residents (including the Rogers family) eventually left Parowan for other settlements, Parowan is often called the “Mother Town of Southwestern Utah.”[60]

Little is recorded of Anna Matilda’s life other than the information here, but a few details from Samuel’s life help readers understand the family dynamics. In 1853, three years after marrying his brother’s wife, Samuel married a second wife, Ruth Page.[61] Shortly afterwards, he moved his family to Parowan. Then in 1857, he married a third time, to Lorana Page, a sister of Ruth.[62] Neither of these two women had any children, but instead helped raise the children of Samuel and Matilda.

In 1869, Samuel H. Rogers was made bishop of the “east ward” in Parowan. He was also the justice of the peace, a director for the United Order, and a local missionary. In July 1877, he was called as bishop of the Second Ward in Parowan.[63] All of these activities left little time for his family, and many family responsibilities fell to his three wives. By 1877, there was some disharmony in Parowan over a new stake president; for over a year, this priesthood office was left vacant.[64] In March of 1878, William H. Dame was sustained as president with Jesse N. Smith as first counselor, but as Joseph Fish wrote, “I think that the disunion or party feeling that had existed in Parowan for some time at the division in getting a president for the stake had some effect upon the Smith boys and particularly Jesse N. This may have had some influence in our taking the move that we made at this time [to Panguitch].”[65] Then Jesse N. Smith was on his way to Arizona by December 1878, and in his party was Smith D. Rogers, son of Samuel and Matilda Rogers. By September 1880, Samuel H. Rogers was in Snowflake and was sustained as a member of the high council.[66]

Matilda Doolittle Rogers lived less than ten years in Snowflake. Jesse N. Smith’s journal entry for September 23, 1887, reads, “Anna Matilda Doolittle Rogers having died, I preached her funeral sermon.”[67]

Avis Laverne Leavitt Rogers

Autobiography

Maiden Name: Avis Laverne Leavitt

Birth: June 17, 1878; Kanosh, Millard Co., Utah

Parents: Lyman Leavitt and Ann Eliza Hakes[68]

Marriage: George Samuel Rogers;[69] January 8, 1896

Children: George Vernon (1896), Collins Rulon (1899), Mabel Ann (1901), Avis Pearl (1902), Lyman Henry (1905), John Leavitt (1907), LaVerne (1910), Samuel Glenn (1913), Florence (c. 1918),[70] Betty Jo (1923)[71]

Death: March 9, 1965; Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

I was born at Kanosh, Utah, June 17, 1878. My parents were Lyman Leavitt and Ann Eliza Hakes.

When I was four years old, my father was called to leave his home and help settle in Arizona. We left Kanosh in the winter, and the ground was covered with snow. I was just four years old, and I remember as we left the people came out along the way to bid us all good-bye. I can also remember we crossed the Colorado River on a ferry or flat boat. While crossing, one of Dad’s horses stepped off the flat boat with his hind foot. I can just see Father patting his head and talking real low to him and finally getting him back on the boat. We went through a town called Hackberry, and when we camped that night I found a nice white towel with red stripes for the border.[72] This was one of my prized possessions, and I kept it for many years. We had many hardships on our way down, and roads were rough and long.

Avis Leavitt with siblings: front row, left to right: Joseph, Mabel "Mae," Lucy Pearl, Avis; back row: Lucinda "Cindy," John. Photo courtesy of Wayne Standage Jr./ Dilworth Brinton Jr.

Avis Leavitt with siblings: front row, left to right: Joseph, Mabel "Mae," Lucy Pearl, Avis; back row: Lucinda "Cindy," John. Photo courtesy of Wayne Standage Jr./ Dilworth Brinton Jr.

The wind and dust storms we had in those early days were awful. The first summer [in Mesa], we had a hard one which hit just after we had gone to bed. Mother and Dad were each trying to hold the tent down to keep it from blowing away. One of the neighbors crawled in under the tent and rolled me up in a blanket and carried me to their house and put me in bed with her mother and father, then went back after my brother John, who was two years old. Another time a terrible storm was coming, and Dad thought it was a cyclone; it looked so terrible. He rolled us all up in quilts and took us all out in the orchard and waited to see what it would do. If it got worse, we were to put our arms around a peach tree and hang on for dear life. This time it went around, and we only got a part of it, for which we were very thankful. Father soon bought a lot and built an adobe house on it. It was where the Catholic church now stands. The jailhouse was where it is now, and the windows had iron bars across them. Father would take my brother John and myself across the road to the jailhouse and we would sit on the ground while Father sang songs and talked to the men in jail.

We went to church under a bowery made of logs and brush. Logs were set in the ground with logs across the top of them, then brush and willows spread on top of them for shade, with benches for seats. When my sister Mabel and I were old enough to go to school, we had to walk to school and then home for our dinner. As soon as it was warm enough, we went barefoot. Some days the ground was so hot that we would run as fast as we could until our feet got so hot we would throw our bonnets on the ground and step on them to cool our feet, then run on. Our bonnets were made with pasteboard slats across the front and tied under our chins. One day we were running along and an Indian girl stepped out from behind a tree and whipped our legs good and hard, and it made us late for school. A few months later, as some of us were coming home from school, she took after us with a scythe and said she was going to cut our legs off. We all ran through the pasture, screaming to a neighbor. When he came out, the Indian girl, Juana, ran home. She was about fifteen years old then, and soon after she was sent back to her people.

In a few years, Father bought a twenty-acre ranch out east of town, north of the temple. Father built a large home for us, and when it was partly finished we moved in. My brother John and I helped make adobes for the walls, then we would help load them up and then unload them. We helped on the farm and had the usual chores to do. I was always happy when I could wade in the water and mud to help set out sweet potato plants. We also had a large strawberry patch. Many times I have helped pick the strawberries and then take[n] them to town in a big white dishpan and sell them to the hotel, which was run by my Grandfather and Grandmother Hakes. Father planted a nice orchard and vineyard, and we always had a good garden. One year the farmers went in together and bought a lot of orange trees, and not knowing how to protect them, they froze.

Wedding photograph of George Samuel Rogers and Avis Lavern Leavitt, January 8, 1896; Hartwell, Phoenix. Photo courtesy of Wayne Standage Jr./ Dilworth Brinton Jr.

Wedding photograph of George Samuel Rogers and Avis Lavern Leavitt, January 8, 1896; Hartwell, Phoenix. Photo courtesy of Wayne Standage Jr./ Dilworth Brinton Jr.

We had bees and extracted lots of honey. We used to help with the extracting about four times a season. It would take five or six days to get the honey extracted. When the peaches were ripe, we would pick them in the afternoon, and then at night everyone would pitch in and spread them on crates. We would put them in the smokehouse and burn sulfur under them, leaving them in all night, and in the morning they would be nice and white. We would put them out to dry, and it took about a week. We also made peach preserves using honey. This was put in five-gallon cans. We had a herd of cows, and I used to help milk.

I remember one year we cut and dried peaches to sell to pay my mother’s way to Salt Lake to conference. The night she left, while Dad was taking her to the station, my brother John accidentally tipped over the coal oil lamp. It threw oil on the table and floor, which caught on fire. I remember grabbing the burning lamp and running to the kitchen door and throwing it out. I grabbed the mop and began to beat out the fire. After it was all over with, we were all so scared we didn’t dare light a match, so we huddled in bed with our clothes on until Father came home. He thought I was a brave girl.

As a child, I remember the smallpox epidemic that caused a good many deaths and severe sickness. A young boy had been away from home and came back with an awful case of prickly heat, so everyone thought, and the people all went to see what he looked like. It later turned out to be black smallpox, so everyone was exposed. Grandfather Hakes did a great deal of nursing the sick at this time.[73] They put the people in what they called the pesthouse. My mother, along with the other women, would cook food to send to them. We children would take whatever Mother fixed and carried it down past our front gate, and someone would be by to pick it up. If we heard a lumber wagon in the still of the night, we knew they were taking someone to the graveyard to be buried.[74]

Whenever it rained good and hard up in the mountains, floods would come roaring down the Salt River, and we would all go down to watch the rolling water. It would be carrying trees, brush, and logs, and did it look wicked. No one could go or come from Phoenix until it went down enough so they could ferry across. It was too dangerous to ferry across when the river was at its highest. When the water started over the banks, the Indians would start leaving to camp up on the hill. They would jog along all night and day, in their old wagons or walking or riding horses, chanting their Indian chants. After the waters receded, the Indians returned to their homes.

Ice was very scarce, and when we got a little, we would make ice cream by filling a large bucket with crushed ice and salt, then whirl a bucket filled with ice-cream mix around in the ice. Every little while we would open the bucket and scrape the sides down and then whirl some more until it was frozen.

One time, thirteen of our ducks were missing at feeding time. We couldn’t find them, so Mother and I went over to the neighbor as they had ducks just like ours. The extra ducks were there, but we couldn’t tell which were which. Father always stacked his wheat instead of thrashing it, so we always fed our ducks by pulling the bundles of wheat out, and our neighbor always fed theirs by throwing out thrashed wheat. As they didn’t have any stacked grain, Mother went to their haystack and pulled out handfuls of hay. Immediately here came thirteen squawking ducks. Our neighbors said, “Take them, Sister Leavitt, they are yours.”

As I was growing up, I learned to cook and sew and keep house and do the things girls should do. My mother was an excellent teacher, and when I grew older I used to work out for people. I would work every day with just Sunday afternoons off and get two dollars a week. It was while I was working with my aunt and uncle, who ran a boarding house at the mines, that I met George Samuel Rogers.[75] He drove to the mine with loads of hay and watermelons. He would make the trip about every two weeks. This was in 1895. After I moved back home, I started going with him, and we were married at my home by Collins R. Hakes, my grandfather, January 8, 1896.

In August 1897, we traveled to St. George by team and wagon. It was a hard trip and took us seven weeks to make it. On the way home, we found the water was so high in the river we had to camp for a week, waiting for the water to go down so we could ferry the wagon across. We came through Flagstaff and camped about five miles out in the pine trees. We had had our evening meal and were prepared for bed. While we were kneeling in prayer, we heard this terrible whooping and yelling and thundering of horses’ hooves. The temptation was just too great, and I couldn’t resist taking a peek. I turned my head just enough so I could look out the corner of my eye—my heart beat about three times faster than it should—three Indian braves, all painted up, were riding in on us just as hard as they could ride. How he did it I will never know, but George, not even hesitating to peek, just kept right on praying and asking Heavenly Father to protect us from these Indians. They rode right to the wagons before they reigned up. They were so close we could almost feel the breath of the horses as they sat down on their hind legs to stop. The Indians looked in and saw George praying, they gave a whoop, whirled their horses around and left. We could hear them yelling as they rode away. Needless to say, we had a great deal to be thankful for that night. We were told later that Indians are very superstitious about people praying, and that was probably why they left without bothering us at all. We knew that the Lord had answered our prayers as he had done so many times before.

A visit to Pine stands out in my memory. It was when my sister-in-law was sick. I was sitting up with her, and about midnight I heard a rumbling noise. It sounded like a lot of mice running around and got louder and louder. Then the whole house started to tremble. I had never heard such an eerie sound or had such a queer feeling. I remember thinking it was an evil spirit. The chair I was sitting in just rocked back and forth. I was so frightened, I just didn’t know what to do. Then just as suddenly as it had began, it quit. Mother stuck her head in and said, “Laverne, did you feel that earthquake?” I was so relieved I remember saying, “Thank the Lord it was only an earthquake.”

Avis Laverne and George Samuel Rogers. Photo courtesy of Wayne Standage Jr./

Avis Laverne and George Samuel Rogers. Photo courtesy of Wayne Standage Jr./

When we were married, we lived in Mesa two years, then moved to Lehi, where we lived for fifty-seven years. My husband took sick, so we sold our farm and moved to Mesa, and nine months later he died, March 4, 1954. We had ten children, five boys and five girls, but two boys died in infancy.

I have been a counselor in the Maricopa Stake YLMIA and was treasurer in the Lehi Ward Primary, then counselor from 1903 to 1910, president from 1911 to 1916, and teacher in 1920. I was president of the ward Relief Society at two different times, and I was work director and visiting teacher. My hobbies are making rugs, knitting and crocheting, and making nice quilts. I have made a quilt for every one of my children, grandchildren, and many others.

I lived in the days of pioneering in this valley, and I am thankful that I was allowed to come to earth at this time. Our home was one of love and kindness, and my father was a man of God. Mother and Father were diligent Church workers and brought their children up in the way of the Lord. We had very few conveniences in my day. It would take us all day to wash, and now if we are willing to get up early we can have the washing on the line by breakfast time. We used to travel with wagons and buggies; now it is the automobile and airplane. We used to go to church, first in a brush shed, and then later on, a stake house was built, and we were so proud of it. When we went to Pine forty years ago, it would take about six days of traveling with a wagon and team. We would stay a few days and then the long journey home. Now we can travel it in a few hours by auto on well-paved roads with all streams bridged over. The heat was almost unbearable. We had no coolers in our houses, and the clothes we used to wear are even too hot for winter now. It would take us days to get ready to go on a trip; now we can be ready in a few minutes and be 150 miles away in a couple hours.

Thus ends the story of Avis Laverne Leavitt Rogers. Death came to her March 9, 1965, at Mesa, Arizona. She was beloved by everyone that knew her and was truly a pioneer in every sense of the word.

Ellis and Boone:

In this autobiography, Avis Laverne Leavitt Rogers provides descriptions of farming around Mesa. The settlers used these farm products for both subsistence and sale, giving them cash income. Rogers also tells of drying fruit to preserve it for later use. Dried apples, peaches, and apricots were used for pies—sometimes fondly remembered and sometimes not. Elizabeth Lambert Wood of Oracle remembered Charlie Jackson, an African-American cook for mine owner John DeWitt Burgess, and wrote, “It did not take us long to learn that Charlie made the best dried apricot and peach pies in the land.”[76] On the other hand, an anonymous boarding-house guest in Tucson penned the following poem:

Dried Apple Pies

I loath, abhor, detest, despise!

Abominable dried apple pies.

I like good bread, I like good meat,

Or anything that’s fit to eat;

But of all poor grub beneath the skies

The poorest is dried apple pies.

Give me a toothache or sore eyes,

In preference to such kind of pies.

The farmers take their gnarliest fruit

’Tis wormy, bitter, and hard, to boot;

They leave the hull to make us cough,

And don’t take half the peeling off.

Then on a dirty cord they’re strung,

And from a chamber window hung,

And then they serve as roost for flies

Until they’re ready to make pies.

Tread on my corns, or tell me lies.

But don’t pass me dried apple pies.[77]

Although the sketches in PWA do not generally mention sanitation problems, Mesa, as probably all other towns of that era, had to contend with animal and human waste and flies spreading disease. W. Earl Merrill wrote a newspaper column titled “Pioneers Had Garbage, Too,” citing early Phoenix newspapers telling about city ordinances to deal with the accumulation of waste. Merrill wrote, “Such were the unsanitary habits of the early citizens of our neighboring city of Phoenix. Though we do not have the newspaper clippings to prove it, early residents of Mesa were probably just as careless.”[78]

Clara Maria Gleason Rogers

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP[79]

Maiden Name: Clara Maria Gleason

Birth: May 28, 1860; Farmington, Davis Co., Utah

Parents: John Streeter Gleason[80] and Desdemona Chase

Marriage: Andrew Locy Rogers;[81] August 28, 1879

Children: Andrew Locy (1880), Spencer Chase (1883), John Thomas (1885), Marion (1887), Alvirus Ogden (1889), Leroy (1892), Clara (1894), Desdamona (1896), Leone (1899), Thora Aurelia (1902)

Death: December 26, 1932; Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

On May 28, 1860, in the little town of Farmington, Utah, was born to John Streeter and Desdimona Chase Gleason a baby girl who was later given the name of Clara Maria. She was one of six children of this sturdy pioneer couple, who had accepted the gospel in Ohio, had sacrificed their all, crossed the plains, and gave to their little family what care and comfort frontier life at that time could afford.[82]

She was educated in the best schools of the day and led a comparatively uneventful life, until she met Locy, the son of Thomas and Aurelia Spencer Rogers, pioneers from Canada and Connecticut. This was a red-letter day in her life, for his mother, a sincere and enthusiastic worker for truth, was later the founder of the Primary Association, and had inspired her son with many of her ideals.[83]

Locy and Clara Rogers. Photo courtesy of Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

Locy and Clara Rogers. Photo courtesy of Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

Her future husband, though unsuspected at that time, was employed in the ZCMI, from which position, in 1876, was called by President Brigham Young, with about 200 others, to form the first company to make a settlement in the then wild and unknown wastes of Arizona.[84] This company left Utah on February 21, 1876, crossed the mountains with snow six feet on the level, parts of the trail having to be plowed through enormous drifts. In spite of hardships, they arrived at their destination, Sunset Crossing (across the river from where Winslow now stands), with cattle, sheep, horses, seeds, etc., lived in their wagons until the first crop was in and water on the land.

The Order of Enoch [United Order] was established, with Lot Smith in charge. The buildings were arranged and built on a cooperative plan. A large building in the center served both as dining room and chapel, the kitchen adjacent was in charge of a man (the position in that day being too important for a mere woman), but the women, three in number on a daily relay plan, did the work. Food was sometimes scarce, but bread and sorghum molasses were staples. Because of this shortage, a rule was made that all food should be eaten from the plates; any left would be reserved to those particular individuals at the next meal. A cheese factory took care of the surplus milk, a tannery produced leather for buckskin clothes, shoes, and harnesses (the latter not being very satisfactory however, because the character of the tan permitted [the leather] to stretch), a sawmill cut sufficient lumber for all their needs.

The women were supplied with spinning wheels, carding machines, and looms, and made good, substantial “homespun.” By filling in cotton warp with wool, a good linsey was made. As some were more efficient than others in spinning and weaving, they exchanged work with those less fortunate.

Nearly three years passed, and having made all preparations for his life partner, Locy took the trail back to Farmington, where he surprised his fiancée and upset her feminine plans for a fitting trousseau by insisting on an immediate marriage. Through the advice of her mother, she finally consented, and they were married in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City, Utah, on August 28, 1879, by Elder Joseph F. Smith, who later became President of the Church. On their return trip to Farmington, they bought about a dozen fine watermelons, a delicacy not to be had as yet in Farmington, and upon reaching home they found their relatives, friends, and a wedding supper awaiting them, the melons supplying a luscious finale to the feast, which is still remembered with gastronomic delight.

Shortly afterward they started for their new home alone but later met two families from Ogden, which proved beneficial for each, as Locy knew the trail well and the others relieved the monotony of the journey.

As a means of encouragement and a source of consolation in food deficiencies, poor water, or similar conditions to be met, Locy would frequently speak of the wonderful bread and milk to be had in such abundance at the journey’s end. Well, the trip ended, as all trips must do, and upon pulling into camp, they found their friends, who had so anxiously and impatiently awaited the coming of Locy’s bride, with true hospitality had prepared a feast of the best the fort afforded. With much joy and some misgiving, they were seated together at the bountiful board, and Clara, recognizing the much-talked-of milk, reached for her bowl, tasted it, and set it down. Later she tried again and finally said, “Well, if it comes back forever, I’ll not drink that milk.” Locy, wishing to save his bride an infraction of the rules, drank it for her. The strained feeling dawned at last on the hosts when a child refused to drink its milk also. Investigation then proved the milk to be in that sickly “blue-john” stage, so unpalatable to all. The trouble had arisen when a sour milk pan, instead of a sweet, had hurriedly been brought from the row of shelves in the milk house. The event was speedily forgiven when the fresh milk, in quantity and quality which Locy had advertised so fluently, was served as needed.

Of course, there were no canned fruits or vegetables on the table; such things were an unheard-of luxury. Sometime later, however, when some old friends from Farmington came to work on the railroad grade and brought some canned fruits and vegetables, especially for a feast with “Locy and Cad” (with the understanding that they were to furnish the milk), an old Danish man said it was an outrage that some could have such “victuals” as that—fit for a king—while others were deprived of anything approaching it.

Mrs. Rogers and her husband were sincere workers for the success of the order. While they could have found fault many times, they preferred to remain quiet and “boost” the work along, anxious to see if it could be made a success.

About this time, Locy was assigned to the position of wood-hauler to the camp. He arose early and returned late with all he could haul. When the weather was extremely cold, the women [were so desperate for wood that they] waylaid him with axes [to help cut it into appropriate sizes], and the wood sometimes literally failed to touch the ground. In the summer, they were transferred to the sheep range, and while engaged in that work on one occasion, Mr. Rogers was impressed very strongly to move away from the place where they had made their camp. He paid little attention to the first urge to move; when in a short time it was repeated, it appealed to him with greater force. When it came the third time, he was so impressed that, although they had retired, they got up and hurriedly packed their camping equipment and moved at once. Later, they learned that their delightful camp had been a battleground between the Indians and U.S. soldiers and an Indian had died in their newly built cabin.[85]

Impressions were not always regarded in the same light, however, for later when they had returned to the fort, Mrs. Rogers was waiting with fond heart in anticipation of her husband’s fortnightly visit, he coming one weekend and his partner the next. Much to her surprise, instead of Mr. Rogers, the partner came two weeks in succession, explaining, “I just could not rest until I came to see you, but I’ll tell you, I had an impression to come and leave Locy out there with the sheep, and so I came.”[86] She told him she wondered if he would ever have an impression to let Locy come twice, whereupon he answered, “I’m sorry, but I see it hasn’t impressed you as it did me.”

Sometime after this, Mrs. Rogers was again appointed as companion to her husband in sheep herding, thereby releasing one man for more strenuous work. One day, her husband was much startled at the sheep stampeding down the mountainside, and, rushing up to see the cause of the disturbance, came face to face with a large bear. Being unarmed, Mr. Rogers stopped when the bear stopped, and they surveyed each other steadily for a little while, then the bear dropped to all fours and withdrew slowly up the mountain, leaving him victor of the field and the spiritual uplift that “the true shepherd will give his life for his sheep.”

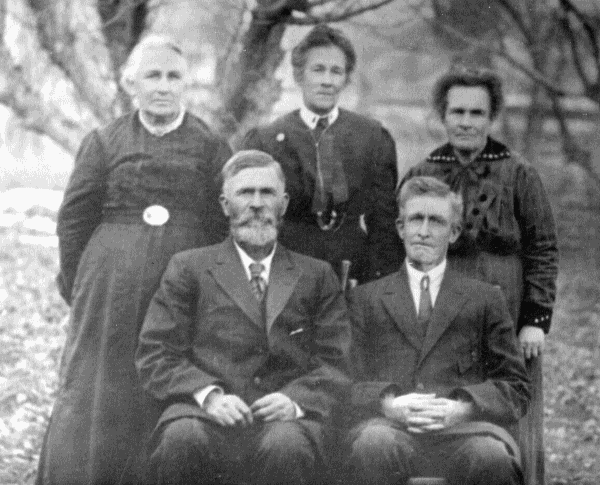

Clara Gleason Rogers (seated, gray dress) with her two sons, Andrew Jr. (left) and Marion with wives and daughters: Rebecca Smith (seated) with baby Beatrice Rogers (Papa) and Lenora Smith (standing) with daughter Mayola (Miltonberger). Apparently the family was visiting their grandmother, Aurelia Spencer Rogers (black dress), in 1914. Photo courtesy of LeOla Rogers Leavitt.

Clara Gleason Rogers (seated, gray dress) with her two sons, Andrew Jr. (left) and Marion with wives and daughters: Rebecca Smith (seated) with baby Beatrice Rogers (Papa) and Lenora Smith (standing) with daughter Mayola (Miltonberger). Apparently the family was visiting their grandmother, Aurelia Spencer Rogers (black dress), in 1914. Photo courtesy of LeOla Rogers Leavitt.

Their first baby, a boy, was born at the fort, and while no great sensation to the general inhabitants, for other babies had been born there, it was a never-to-be-forgotten day in the Rogers household. He was a lusty little fellow and thrived on frontier life. Notwithstanding their dearth, he was supplied at one time with a multiple musical rattle that is seldom surpassed in value; though of short duration, it was superb while it lasted. It happened thus: Five or six years before this, a Mexican employee had robbed his employers of about seven or eight thousand dollars in U.S. double eagles. A posse had formed and pursued him. He had hidden the gold or lost it from his saddle and when caught could not retrace his steps and find it, although he was hung until nearly dead to force a confession. Mr. Rogers’ sheep were on this range, and while walking along the sheep trail one day, he noticed a peculiar glitter to the oak leaves. On closer observation, “the leaves” proved to be twenty-dollar gold pieces. About ten feet away, he saw one of the little mounds of rocks which had been made to mark the ground as a guide to the searchers that that part of the country had been thoroughly searched. He tied the ends of his coat sleeves, filled them with gold, and hurried after his sheep. Arriving at the camp, he notified the owner that the gold had been found and that he might have it by calling for it. So the baby played with the gold pieces on the bed and rejoiced at the musical clink as they jingled together, for the owners had given Mr. Rogers a handful of coins which counted out to be $200.[87]

The Order went along with more or less dissatisfaction—the people were American-born and restriction irked—a few dollars’ extra profit failed to compensate for personal prerogative. So when the dam went out of the river, as it had done frequently before due to current and quicksand (but this time had taken the gristmill with it), they decided to have the requiem sung over the remains of the Order of Enoch. President Taylor appointed a committee to investigate, audit, and give a just settlement when each family went to itself.

The Rogers family moved to Joseph City, remained there for about a year, then bought land in Snowflake, where they have resided ever since. They had ten children and reared seven, all receiving good educations, some college graduates.