Q

Roberta Flake Clayton, "Q," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 565-568.

Mary Rapier Quinn

Roberta Flake Clayton

Maiden Name: Mary Rapier[1]

Birth: January 1, 1874; Hackleburg, Marion Co., Alabama

Parents: John Andrew Rapier and Elizabeth Scott

Marriage: Allen McGee Quinn; April 8, 1893

Children: Edna Elizabeth (1897), Lester Floyd (1898), Lola May (1900), Eugene Allen (1904)

Death: December 4, 1957; Phoenix, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: East Resthaven Cemetery, Tempe, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Arizona, land of sunshine, flowers, fruits, rich metals, and romance, has gathered her substantial citizens from every state in the Union and from many foreign countries. The hardy pioneers were also representatives from far and near. Some came on foot with burros, some by ox team, some with fine horse teams, and after the advent of the railroad in 1881, the pioneers came by train, provided they had the price.

The Rapier family was among the latter, leaving their home in Alabama for Arizona in 1886. Always having been farmers, they found their way to the fertile valley of the Gila River, and settled at Safford.

Mary Rapier Quinn was the daughter of John A. Rapier and Elizabeth Scott. She was born on a plantation in Franklin County, Alabama on January 10, 1874 [sic]. When she was only four years of age, her mother died, leaving three children. Young as she was, Mary had pleasant memories of her mother. She used to give them a frying pan with sweet potatoes, turnip greens, and other food and let them cook it over a stone fireplace they had made and have little play dinners. Caroline, the older sister, was the cook. The young brother gathered the wood, and Mary was the taster.

After the death of her mother, Mary went to live with her Grandmother Scott. There she was petted and might have been “spoiled,” but her father married again and she went back home.

Always a lover of out-of-door life, Mary spent much time wandering about the plantation. Mother Nature seems to have been extra lavish to her children in the South. There were wild strawberries, gooseberries, huckleberries, peaches, scuppernongs, muskadines, persimmons, paw-paws, hickory nuts, walnuts, chestnuts, and pecans. There was no season of the year but what Mary and her sister could find something out in the woods to eat. She laughingly said that “Babes in the Woods” would not have fared so badly in Alabama.

Then there were the farm products. In one corner of the barn were Irish and sweet potatoes, cabbage, beets, turnips, carrots, and parsnips in pits. Peanuts were raised by the bushel and stored in the barn for winter use. In the smokehouse were enough hams, bacon, and lard to last the family.

The Rapier children had to go quite a distance to school. Because of deep snows in winter, their schooling was interfered with.[2]

When Mary was twelve years old, the river near their farm was flooded for days, submerging their land. This was not an unusual occurrence, but this time it helped John Rapier to decide to take his family and go West. They boarded the train at Bell Green, a little station nearest their home.

Mary was old enough to have regrets at leaving the place she was born. Then there were childhood companions left behind. When they changed cars at big, busy, smoky Birmingham and took the train to Memphis, there was so much to see, so many new sensations, that there was not time for homesickness until after the new had worn off in the Arizona home.

There were many Southern families already living on the Gila who welcomed the newcomers. Mr. Rapier moved his family into an adobe house on a farm that he rented for the first two years. After that, they spent their summers in the mountains where Mary’s father worked at a sawmill. They would return to Safford in winter. There the children went on with their schooling.

Mary was very fond of horseback riding. One day a very serious accident happened to her when a dog ran out and frightened her horse. He threw her and then kicked her. She always carried the scar as a reminder of the terrible experience.

Her independent nature prompted her to go out into homes and work, so that she might have her own money to buy her clothes. Because she was a good, conscientious worker and blessed with a cheerful, obliging disposition, her services were always in demand.

In spite of the fact that she had to work, Mary was very popular with the young people. Good looking, vivacious, and fond of dancing, riding, and skating meant her young ladyhood was very happy.

On April 8, 1893, Mary became the wife of Allen McGee Quinn, the grandson of one of the earliest Southerners to pioneer Arizona.[3] They were married at the home of her sister, Mrs. Robert Morris. The wedding was a grand affair, attended by neighbors and friends for miles around. The bride looked lovely in her white silk wedding gown, which she had earned herself.

A dinner and a dance followed the ceremony. It was a happy occasion. Many useful and beautiful presents were given the newlyweds. They went at once to housekeeping in their little home, which was dearer to Mary since she had been deprived of a home for so long.

Time went swiftly by to Mary. Their home was blessed with four strong healthy babies. Instead of working in other homes, Mary was happy in taking care of her own and enjoying her babies.

Her sister died, and then Mary showed her unselfishness and devotion.[4] Though she had broken her ankle when a girl roller skating, and it has always hurt her, she used to walk twice a day to her sister’s home to look after her three little ones. They lived a mile away, but that made no difference to Mary. She took their sewing, mending, and other things that she could to her home to do for them, but she wanted to see that they were properly cared for.

Until the day of her death, when any of them have any real or imaginary trouble, they always took it to “dear old Aunt Mary.” It could well have been she that James Whitcomb Riley wrote about.[5]

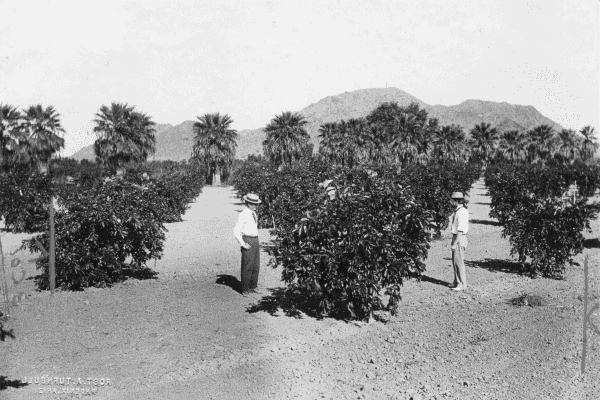

No image was located of Mary Rapier Quinn, but the family moved to Phoenix in 1928, purchasing an orange grove. This 1911 photograph shows a two-year-old grove (meaning two years in production) with Camelback Mountain in the background (originally printed reversed in the January 1912 Arizona Magazine). Photo courtesy of Collection of Royal John Medley.

No image was located of Mary Rapier Quinn, but the family moved to Phoenix in 1928, purchasing an orange grove. This 1911 photograph shows a two-year-old grove (meaning two years in production) with Camelback Mountain in the background (originally printed reversed in the January 1912 Arizona Magazine). Photo courtesy of Collection of Royal John Medley.

The Quinns lived in Safford until 1913, then moved to Miami, where Mr. Quinn was employed in the mines. In July 1928 they moved to Phoenix, and bought a citrus grove north of the city, where they still reside.

Mary was a fine seamstress and until late years made all of her own and her daughters’ dresses and those of her granddaughters.

“She was one of the most generous and big-hearted persons that ever lived,” so said one of her neighbors. Another one added, “If Mary had known of anyone worse off than she, she would go to them, or bake a cake or something nice to send them.” One of her daughters said she had known her to get out of a sick bed herself to fix something appetizing to send to a sick friend.

She had a way of making people like to do the thing she wanted done. One time when she was very ill in a hospital and the doctor said she shouldn’t have anything to drink for three days, she bribed her children to bring her some soda pop, and “that saved my life,” she said.

“You never get over stage fright,” was her excuse for never appearing in a public position, but she was usually the life of any party she attended. “You are never any older than you think you are,” was one of her maxims.

Later years, rheumatism and her broken ankle prevented her going away from [home?] very much. “One of my chief causes for thankfulness,” she laughingly said, “is that I’ve never been afflicted with rheumatism in my tongue.”

Friends and relatives thronged around her in her advancing years, as did suitors in her younger days, charmed by her personality, her cheer and optimism. This dear lady passed away December 4, 1957, at the home of her daughter Edna Foote in Phoenix, Arizona, and was buried in Tempe.[6]

Ellis and Boone:

The John Jackson Quinn family came to Arizona in 1878 as part of the Arkansas Company (headed by N. P. Beebe). This group also included LDS converts from other southern states (e.g., the Alexander Stewart family from Georgia). Most were poor when they began their journey, and by the time they straggled into northern New Mexico and Arizona, they were sick (with smallpox) and destitute. But for the ministrations of William J. Flake, John Hunt, and Ira Hatch, more would have died than did. Many eventually settled in the Gila Valley. Ryder Ridgway made this list of those who settled in the Gila Valley: “the D.V.A., K.V.B., Tom, and Robert Talley families; the Mrs. Robert Golding family; the John Jackson Quinn family; the John Scarlett family; the Gad Morris family; the Alexander Stewart family; the John and William Waddell families; the Alonzo McGrath family (moved to Duncan); the Gus Branch family; the Nathan Wanslee family; the John Wilson family; the John Evans family; and two single men, Austin Evans and Cyrus Spafford.”[7] Other members included the James T. Austin, James K. P. Pipkin, Thomas West, and Jesse W. Dempsey families.

Although the early Gila Valley merchant I. E. Solomon is not mentioned in any of these sketches, his biographer, Elizabeth Ramenofsky, provides some insight into interactions between Solomon and the Mormons: “Isadore Solomon’s attitude toward the Mormon settlers was the same as that of many non-Mormons: he feared that their strength in numbers would be too influential politically, and he disapproved of the practice of plural marriage.” Then she told a story of a man named H. W. Bishop, who came to the Gila Valley and wanted to purchase some land. Originally, Solomon refused to sell because “he had mistaken the man’s name for a title in the Mormon church.” Later Solomon realized his error, made amends, and the two men became friends. Ramenofsky’s conclusion was that “over time Isadore learned to respect the initiative of the settlers from Utah, and many became trusted customers and friends.”[8]

This same initial distrust with later compromise and working together could be noted for both Solomon Barth in St. Johns and Gustav Becker in Springerville. Becker’s son Julius briefly mentioned these early tensions when the Daughters of the American Revolution wanted to erect a Madonna of the Trail statue in Springerville; the DAR let Julius know that they “would under no circumstances recognize the Mormons” in the inscription on the base of the statue. Nevertheless, people of all religious persuasions participated in its dedication, and Governor George W. P. Hunt, in his address, made a point of mentioning the “pioneer Mormon women [who] faced incessant fatigue and constant danger . . . [so] they might worship their God according to the dictates of their own conscience.”[9] But, regardless of these early tensions, there were often marriages between the two groups.[10]

Note: When beginning this project, we understood the difficulty of using Arizona FWP sketches, because they often do not mention Mormon affiliation. We looked but did not find that information for Mary Rapier. Recently, however, Mary’s grandson, Avery Frantz, has added information and photographs to the findagrave website (#104723681). This is his tribute to his grandmother (punctuation standardized):

Mary Rapier came to Safford from Alabama in 1884 with her family when they became Mormon. . . . Before they came to Arizona they had missionary guests at their house in Alabama and sometimes held meetings there. Mary and her family settled at the foot of Graham Mountain when they first came to Safford. Mary Rapier was a very sweet and quiet old lady. Her mother Elizabeth died when she had her brother Joseph “Clint.” Mary only had two full siblings, the others were all halfs but she saw them as if they were her full siblings. She worked at the Olive Hotel in Safford as a cleaner. When she went to the Mormon Church they paired her up with her husband Allen McGee Quinn. To finish the wedding everyone went to Packers Hall were everyone danced. . . . Mary moved to Miami in 1913 with her husband; some of her grandchildren and children lived in the same town as them. She knitted little hats for her granddaughter Betty. She always knitted under cairoscene lamp (which we still have). She moved to East Phoenix with her husband in 1928. They lived on an orchard that grew grapefruit, oranges, watermelon, peaches, and pomegranates. When Mary got older she had very bad arthritis and had to use crutches to walk but should have been in a wheel chair—her great-grandchildren Cheri and Kathy use to take her crutches and use them as a rocket to shoot themselves off. Many of Mary’s grandchildren and great-grandchildren remember eating all the fruit their little hearts desired.

Notes

[1] Arizona records generally, but not always, show this surname as Rapier (versus Raper).

[2] This is one example of generic pioneer rhetoric that RFC sometimes put in her sketches; in this instance, there were simply no “deep snows” in Alabama—maybe there was occasional snow. Nevertheless, the children may indeed have had limited schooling.

[3] Allen Quinn’s grandfather, John Jackson Quinn, and father, James Barryman Quinn, were part of the Arkansas company that arrived in northern Arizona in 1877. See Burgess, Mt. Graham Profiles, 1:291−92.

[4] Caroline Melissa Raper Morris died September 11, 1906, and was buried in the Safford Cemetery.

[5] Riley’s poem “Out to Old Aunt Mary’s” includes eight stanzas with one brother reminiscing about visiting Aunt Mary as a child; in the last stanza, he notifies his brother about the death of their aunt. The poem begins:

Wasn’t it pleasant, O brother mine,

In those old days of the lost sunshine

Of youth—when the Saturday’s chores were through,

And the “Sunday’s wood” in the kitchen, too,

And we went visiting, “me and you,”

Out to Old Aunt Mary’s?

James Whitcomb Riley was never considered America’s best poet (particularly by literary critics), but he was beloved by the American people (including RFC). Cook, One Hundred and One Famous Poems, 3−4.

[6] Edna Elizabeth Quinn Foote (1897–1986) was married to George Vernon Foote.

[7] Burgess, Mt. Graham Profiles, 2:87−91. An important source for information on this group is the journal of D. V. A. Talley. David V. Amburg Talley Journal, MS 48 and MS 48211, CHL.

[8] Ramenofsky, From Charcoal to Banking, 71−72.

[9] Ellis and Turner, White Mountains of Apache County, 92−95.

[10] However, it was usually a well-established, non-Mormon man who married an LDS girl; for example, Henry Hopen and Emma/