Part 3: Final Reflections

Catherine H. Ellis and David F. Boone, "Part 3: Final Reflections," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 835-844.

Arizona Women

When Roberta Flake Clayton first published Pioneer Women of Arizona, she could have titled it “Mormon Pioneer Women of Arizona,” except she included seven accounts of women who were never members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and three who had only minimal association with the Church.[1] RFC did not state the religion of each of the seven women, but she mentioned Bahá’í, Presbyterian, and Baptist faiths. She also told about Freemasonry, which, although not a specific religion, was influential in instilling Judeo-Christian values in early Arizona communities of any size. Nevertheless, the overwhelming majority of women in PWA were Latter-day Saints.[2]

In 1977, Christiane Fischer wrote “A Profile of Women in Arizona in Frontier Days” for the Journal of the West. She correctly noted that most historical documents for Arizona pioneers, and even general histories of Arizona, were written by men and about men’s activities.[3] Her observation was that few women wrote about Arizona pioneering in the nineteenth century, but “at the beginning of the 20th century, many surviving settlers were asked about their life in Arizona, and often their memories go back to that decade.”[4] Some of these reminiscences that were given to James McClintock or to the Arizona Republican were from women. It seems likely that Fischer was unaware of the biographical sketches in PWA or was overwhelmed with the unindexed and unanalyzed nature of the book. Fischer did cite the memories of Caroline Teeples from the Gila Valley as published in the Arizona Historical Review in 1929, but twenty-six of the PWA sketches are partially or fully autobiographical and would have been useful for Fischer’s profile.[5]

Fischer also described a dearth of pioneer women in Arizona, not just a dearth of women’s histories. This is illustrated with the statistics she cites from census records and a story that Harold Wayte Jr. recounted about Holbrook. Fischer noted that in the first census for Arizona in 1864, only twenty percent of the population was female, but in 1870 there were forty-two women for every 100 men. By 1880, this had only increased to forty-three women, and in 1890 there were sixty-three women for 100 men.[6] These statistics are the result of single men coming to Arizona as prospectors and adventurers; sometimes these men left wives at home to come later, and sometimes the men found wives among the Hispanic or Native American women living in Arizona.

Harold Wayte described such a town when he wrote about Holbrook. He quoted the Holbrook newspaper as boasting of a town “too tough for women, children and churches” and a town that “had the distinction of being the only county seat in the U.S. without a church.”[7] Then he included this story:

Sidney Sapp, an attorney active in the fund drive for the first church [in 1912], says that he called on one pioneer resident for a donation to the building fund.

“What’s this money for?” the old timer asked Sapp.

The attorney explained that it was to build a church “so families can be induced to come here and make their homes.”

“Who wants to bring women and children here?” was the rejoin[d]er. “This is a man’s country.”

Sapp explained he had brought his wife to Holbrook and wanted her to be able to attend church.

“Send her back to Oklahoma if you want her to go to church,” Sapp said he was told.[8]

Although the first exploring parties Brigham Young sent from Utah were composed of men as described above, by the time Mormon settlers came to Arizona in the 1870s and 1880s, they traveled as families, often extended families. Historian Leonard J. Arrington, citing Relief Society minutes from Snowflake, claimed that this enabled

pioneering women a richer, more emotionally satisfying life than was possible for many other western women.[9] They did this partly by locating in villages, where the families would have close neighbors and would thus find it easy to participate in many village activities, and partly by organizing in each village a branch of the Women’s Relief Society. The Relief Society held weekly meetings where they sang songs, made clothing and quilts for Indian women and children and other needy persons, held classes in hygiene and nursing, and discussed literature and art. These meetings provided opportunities, not only to do worthwhile things for the village but for self-expression and self-fulfillment as well. These women lobbied for the right of suffrage in New Mexico and Arizona, as they had successfully done in Utah in 1870; they had their own magazine, The Woman’s Exponent. Several wrote novels and poetry, and, of course, led in building schools and promoting programs to improve health.[10]

Arrington was describing the town of Snowflake, but his description applies equally well to communities in the Gila and Salt River Valleys. Fischer saw marriage, home, and motherhood, including the care and education of children, as a “dominant [mindset] in the United States at that time” and, in fact, that women in Arizona “had practically no other choice but to be wives and mothers.”[11] These statements are true for Mormon women, but they also saw marriage and motherhood as a tenant of their religion and as an ideal to attain, not only in Arizona but also for the eternities. Large families were the norm, and when women bore no children, they felt the loss keenly. Sometimes, especially in polygamous marriages, a childless woman was given a baby to raise as her own.[12] Other women, such as Lois Bushman, Sarah Curtis, Emma Hansen, Julia West, and Annie Woods, raised motherless children, sometimes their kin and sometimes not.

This higher percentage of pioneer women in Mormon communities, both because they came as families and because they were practicing polygamy, meant that everyone—men, women, and children—had to work to sustain the communities. Food for large families and not just for a lone prospector had to be procured, either by raising crops or by purchase. Long years of widowhood, both because of marrying an older man with polygamy and simply the earlier average age of death for men, meant that many women had to provide their own support. Early Mormon women also worked alongside their husbands, as seen in F. A. Ames’s anonymous women in the Mormon Dairy photograph, who were producing butter and cheese during the summer. Sometimes men helped with this task, but Lucy Flake (and RFC) made cheese and butter on William J. Flake’s summer ranch. Emma Hansen worked alongside her husband, growing and packing garden produce to sell. Margaret Brewer and Salina Smithson (Turley) both physically helped with freighting trips instead of just preparing food for the men on these trips.

Fischer wrote that actual occupations outside the home for respectable women in Arizona were few, and she thought these women were limited to being seamstresses, domestic servants, laundresses, teachers, or boarding housekeepers. With the exception of domestic servant, all of these occupations are seen in the lives of Mormon women.[13] Sarah Driggs and Rebecca Houghton kept boarding houses or hotels; Sarah Francelle Heywood, Sarah “Ina” Pomeroy Brewer, and Charlotte Maxwell Webb taught school much of their adult lives; Louisa Gulbrandsen Cross and Lucy DeWitt Eagar partially supported their children by doing laundry, often receiving fifty or seventy-five cents (and sometimes one dollar) for a day’s work. Many women sewed to provide additional income, including Olena Olsen Kempe, who tells of making the long black frock for the Catholic priest in St. Johns. Sarah Lucretia Pomeroy wrote, “Due to circumstances [apparently meaning polygamy and widowhood] I had to work out all of my life. I worked in stores such as Zenos Co-op, the O. S. Stapley [hardware store], Joseph Clark’s Furniture, George Ellsworth’s grocery, and my brother William and Roy LeSueur’s grocery store. I have done lots of practical nursing. I cooked two seasons for the ‘thresher’ [crew] and one season for my brother William’s bailer crew.”[14]

The occupation that many Mormon women pursued which was not mentioned by Fischer was nursing or midwifery.[15] Initially the pioneers simply helped each other and consulted their doctor books. About 1894, Sarah Vance of Mesa decided to become a licensed midwife. The Vance family had been living in western Colorado and eastern Utah when this decision was made. Sarah’s husband took her four oldest boys back to Mesa, and Sarah took her three youngest boys to Salt Lake City. There she enrolled in Dr. Ellis Shipp’s School of Nursing and Obstetrics, and after six months, she was able to take the licensing examination. She was also given a blessing by Apostle Abraham H. Cannon, setting her apart for this calling. Similarly, Mary Cheshire Ramsay of Snowflake traveled to Salt Lake City in 1886 to become a licensed midwife, serving her community for many years, and May Hatch Decker took advantage of being in Utah before her marriage to take an obstetrics class (sometime before 1897). In the early twentieth century, Lucy DeWitt Eagar wanted her youngest daughter to have some professional training, so they traveled to Utah for a nursing course, and then Lovina Eagar Gardner served the community of Woodruff as a nurse/

The general Relief Society organization in Salt Lake City became the champion of better health care for Latter-day Saint women. By 1915, they were offering a midwife/

Mormon History in Pioneer Women of Arizona

Besides the contributions these women made to their communities as they worked both inside the family circle and outside of the home, these sketches contain a great deal of Mormon history. Although there is little information from the New York period, the sketches tell of time in Kirtland, Ohio; in western Missouri; and in Nauvoo, Illinois. These women remembered or heard their parents tell of the Hawn’s Mill Massacre, the Battle of Crooked River, Joseph and Hyrum Smith’s deaths, and Brigham Young’s transfiguration. They crossed the plains in the first wagon companies in 1847, in both successful and ill-fated handcart companies, and in later years used the down-and-back wagon system. Their men were Mormon Battalion members and handcart rescuers. But the women participated in all aspects of Church history, from the beginning of its organization in 1830 to settlement in Arizona in 1880.

In conjunction with being members of the restored Church, many of these women tell conversion stories, either their own conversions or their parents’. Families and single individuals came from England, Ireland, Scotland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Italy, and Switzerland. The family of Barbara Belinda Mills Haws was Loyalists from Canada. Eliza Parkinson Tanner’s parents came from Australia. And some did not become members of the Church until they came to Utah; for example, Margaret DeWitt’s husband, Alex; Catherine Burton’s father, James M. Barlow; Louisa Cross’s husband, David; and Minnie Wooley Rogers herself.

After arriving in Utah, these women suffered through all the hardships of pioneering in the West. Often they had previously established homes in several places in Utah, Nevada, or Idaho before coming to Arizona. They were part of families who had settled in San Bernardino, California, and along the Muddy River in Nevada. They supported husbands who worked on the Salt Lake and St. George Temples. Finally, many of the women who came to Arizona were born in the West: ninety-four in Utah, five in California, six in Idaho, two in Nevada, and one in Colorado.[20]

Regardless of whether a family received a call from Church authorities to help build Mormon settlements in Arizona or whether they came of their own volition, these families followed Church instructions and made extensive preparations before beginning the trek south.[21] At a minimum, families were to bring enough food to last the six-week to three-month trip, but families were encouraged to bring provisions to last at least until the first crop was harvested. Margaret and William Kartchner, along with their sons and sons-in-law, were called in 1877 to help colonize the Little Colorado River area; they spent several months “gathering provisions and stock, teams, wagons and supplies [to last] for two years.” John Anderson and Melitón Trejo came with an eighty-gallon barrel of cured meat, plus cream and sugar boiled down and a large churn of preserves (see Elsina Peterson Isaacson). One of the better descriptions of preparations comes from Priscilla Hamblin Alger, a sister of Annie Eliza Hamblin Lee. Priscilla wrote that they planned to take “plenty of food like flour & sugar, meat, cheese, [&] butter” so they “went on a ranch & rented cows & started making butter & cheese, fattening 5 hogs.” What they did not decide to take with them, they sold and bought “sugar, coffee, tea, cloth for clothes, & many other things, like shoes, we had manny guns & plenty of amunition, yarn for socks & stockings, [and] Bucks skinn for jackets.” This group traveled with “good strong waggons with double covers on them,” and some of the wagons “had a trail waggon behind.” The company had five men and boys who trailed loose horses and cattle.[22] Priscilla’s mention of guns and ammunition help understand Elese Schmutz Hunt’s assertion that, although after she and her sister reached Snowflake they only had cornmeal and some frozen squash to eat, “it was not long before our husbands went out and killed a deer so we fared pretty well.”

Often these women drove one of their company’s wagons into Arizona. When Elizabeth Allen’s husband decided to come to Arizona, they left Cove, Utah, with “two wagons, four horses to each, a light hack with one team and some nice fat horses.” Elizabeth drove the hack, and RFC recorded that “during these six weeks of traveling, her knitting needles were ever busy as she permitted her horses to follow along behind the other wagons.”[23] Lois Bushman drove a light wagon but tipped it over after only a few days on the trail, breaking her son’s arm and making her mother decide to stay in Utah. Stella Larson’s seventy-two-year-old grandmother, Sarah York Carter, drove one of the company’s wagons from Utah to the Gila Valley.[24] In contrast, John Hunt’s sixteen- and eighteen-year-old daughters, May and Ida, drove one of his three wagons from St. George to New Mexico via Pearce’s Ferry.[25] Mary Flake, age eleven, drove one of William J. Flake’s wagons into Arizona, including up Lee’s Backbone, where she experienced difficulties but refused help from her father.[26] RFC wrote that when Tom and Ella Merrill came to Arizona in 1880, “she drove a team all the way while Tom drove a three span team hauling the provisions of the company. He was the only one who could manage a team of that size. Besides, the other men were needed to drive the loose cattle and horses.”[27]

These initial trips varied considerably. Lucy Flake remembered the hardships and cold suffered during a winter trip, especially when she had to leave her fifteen-year-old son and a hired man behind on the trail to take care of cattle until spring. In contrast, Lois Bushman, even with tipping over the wagon and breaking her son’s arm, thought “the trip was a wonderful one, in spite of hardships. Every day revealed new surroundings with beautiful and sometimes strange scenery.” Lois and her husband also enjoyed harmonizing along the trail.[28] When Annise and Nathan Robinson came to Arizona, she drove her own team so Nathan could trail a hundred head of cattle for a Mr. Shumway. She also took care of their three children, cooked the meals, and knitted three pairs of stockings. Upon reaching the Little Colorado River, they were an hour or two behind the other members of their company, and in trying to cross the river, their wagon got stuck in quicksand and rising water. First, Nathan took the baby and laid her on the bank. Then he returned to rescue the two boys. Annise next handed Nathan, standing on the bank, three sacks of flour which were important not to get wet and threw him six hens and one rooster, which were drowning. (He immediately dispatched the chickens by wringing their necks.) Then the Robinsons unhitched their horses and, with a chain and the horses on dry ground, successfully pulled their wagon out of the mire. Realizing the outcome could have been worse, Annise wrote, “We cooked our chickens and ate supper with thankful hearts. We thanked the Lord for sparing our lives.”[29]

After arriving in Arizona, these women began the process of building homes and communities in a sometimes unforgiving desert. They practiced frugality, rationing out food brought from Utah to make it last as long as possible. Even when they brought enough food to last until crops could be planted and harvested, they shared with those who were destitute (especially those in the Arkansas Company), and soon they were rationing food for their own families. They suffered poverty and hardships, widowhood and divorce. With no social safety net, they worked hard to support their children. Two examples illustrate the activities of many others. After Lucy DeWitt Eagar was divorced, she moved to Woodruff and worked at any job she could find to provide the necessities for her children. Nevertheless, she always yearned for musical instruments. First, she “saved and schemed and went without” to buy two guitars for her oldest daughters. But she still wanted an organ or piano. Once her ex-husband gave her an outstanding note and said if she could collect on it, she could have the money. She did collect the money and used it to purchase a small organ from Sears, Roebuck and Co. Her daughter Sara Brinkerhoff wrote that when the organ arrived, her mother “patted it and looked at it with tears running down her face. She could play one chord on it, and before we went to bed she had sung about every song she knew. She never went to bed at all that night.”[30] The second illustration comes from Anna Kempe, who first lived at St. Johns in Apache County while her sister-wife lived at Concho. Both women supplemented the family’s income by sewing for others. Anna Kempe also kept up a friendly correspondence with relatives in Norway and eventually received $100 as her inheritance. Her granddaughter Ellen Rees wrote that Anna first bought a child’s bed with $10 and paid $10 for tithing. Then she used the remaining $80 to buy a sewing machine. Rees wrote, “The first night that they had it she and her daughters sat up most of the night trying it out, making a dress.”[31]

Oral historians Mary Logan Rothschild and Pamela Claire Hronek describe pioneering all across Arizona as “rough and primitive.” They wrote, “Leaving a beloved and fertile midwestern farm because a family member had ‘weak lungs’ probably made the transition to hardscrabble, waterless homesteading harder than coming at the behest of Brigham Young to make the desert blossom.”[32] Nevertheless, it was only Mormon women who sent husbands on missions, meaning they not only provided for their own support while husbands were away, but they also earned and sent money to their husbands (see appendix 3). They took in borders, sold garden produce, honey, or farm products, and sewed for others. Loretta Ellsworth Hansen was able to be debt free when her husband returned, and Mary Flake Turley had the foundations laid and bricks purchased to add two new rooms to their house. Annie Chandler Woods paid the ultimate price; she passed away before her husband returned from his mission.

The Mesa Temple

The question could be asked: how was Roberta Flake Clayton able to collect such a large number of biographical sketches for Mormon women? These sketches cover the entire state, from Fredonia in the north to Tucson and St. David in the south; PWA includes sketches for women in every part of Arizona where Mormon pioneers settled. Many Mormon women left behind journals, letters, and reminiscences, some of which are quoted in PWA, to document their activities. But the compilation of over 200 sketches for pioneer women is a remarkable feat.

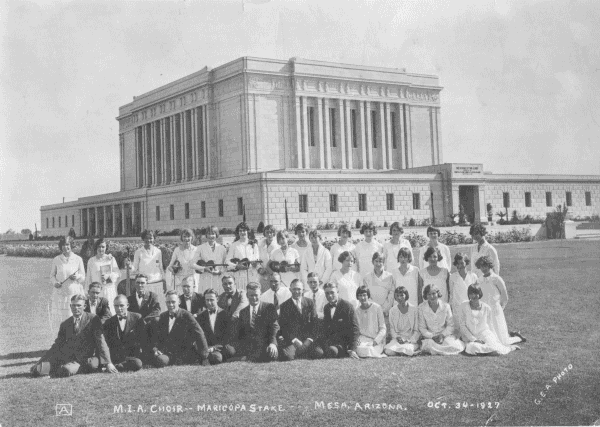

On Tuesday, October 25, 1927, a children's session was held as part of the Mesa Arizona Temple dedication. The Maricopa Stake M.I.A. Junior Choir provided the music. Effa Duke (left) was chorister, and Essie Furr (second from left) was accompanist. Natelle and Bill Clayton were in attendance so they could hear their mother's song. Photo courtesy of Church History Library.

On Tuesday, October 25, 1927, a children's session was held as part of the Mesa Arizona Temple dedication. The Maricopa Stake M.I.A. Junior Choir provided the music. Effa Duke (left) was chorister, and Essie Furr (second from left) was accompanist. Natelle and Bill Clayton were in attendance so they could hear their mother's song. Photo courtesy of Church History Library.

It seems likely that this collection illustrates the importance of the Latter-day Saint temple in Mesa and that the bulk of the sketches in PWA were collected at Mesa. Clayton had little money for travel and no car after 1935; she is not known to have made trips to the Gila Valley, St. David, or Fredonia for any purpose. In addition, many of these women or their descendants are known to have either moved to Mesa or to have spent some winters there. Emma Hansen spent two winters in Mesa attending the temple, and Mary McGuire moved to Mesa specifically to be near the temple. Further, the family of Metta Sophia Johnson believes that her sketch was given to Clayton when a son, Louis, spent a winter in Mesa, and internal evidence in the sketch seems to substantiate this claim.

When church leaders first began discussing a temple for Arizona, Mesa was not automatically considered the best location. Presidents from the Snowflake, St. Johns, and St. Joseph Stakes each made strong arguments for building a temple in their towns. People in the Gila Valley “reasoned that [their area] was much more nearly central in location for the Mormon population in Arizona, New Mexico, and Old Mexico, while Mesa fell at one edge of the Mormon settlements.”[33] At that time, they were right, although today Mesa could be considered a central location both for Mormons and for the state. In addition, Mesa’s summer heat dictated that a temple located there would only be open from September through May.[34]

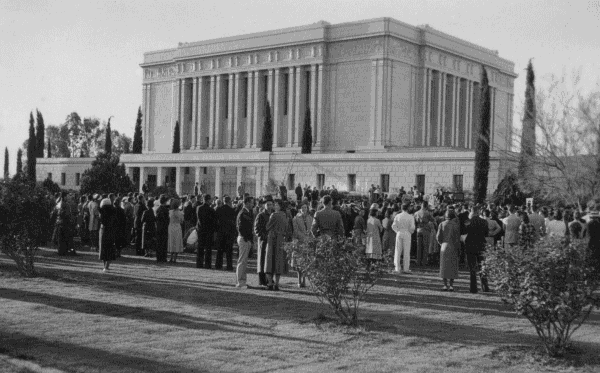

In 1938, an Easter sunrise service was held at the Mesa temple in conjunction with an M-Men and Gleaner Conference for young adults in Arizona and also El Paso, Texas; Max R. Hunt, photographer. Photo courtesy of Ellis Collection.

In 1938, an Easter sunrise service was held at the Mesa temple in conjunction with an M-Men and Gleaner Conference for young adults in Arizona and also El Paso, Texas; Max R. Hunt, photographer. Photo courtesy of Ellis Collection.

After the decision was made to build a temple in Mesa, RFC was one of many Maricopa County residents who worked to raise money for it and who attended the ground breaking and dedication. On Sunday, October 23, 1927, she wrote, “DEDICATION OF THE ARIZONA TEMPLE: I have never been so thrilled in my life as I was this morning when our choir and the congregation sang ‘The Hosannah Anthem’ in the first service of the dedication. This has been a wonderful day and one I’ll never forget.”[35] She often sang with the Phoenix Ward choir, and this group provided music for the first dedicatory service. President Heber J. Grant gave the dedicatory prayer in each of ten sessions over four days. On Monday, RFC wrote, “This was Snowflake day and I saw hundreds of old friends. I went to the store and bought up enough food to feed 43 of the Flake family that joined me for lunch. We had Richard R. Lyman, Bro. Wells and Sister Anna Wells Cannon with us.”[36] The next day, Bill and Natelle Clayton were able to attend the session for children ages six to fourteen; RFC wrote that they came “to hear the song I had composed for the dedication” which was titled, “Accept Our Offering.”[37] Not only were people able to attend the ten dedicatory sessions, they also could hear the words and music while the sat on the lawn, in the Mezona (a church-owned dance hall and auditorium, 748), at ward buildings, and in their homes, because at least the first session was broadcast over the radio.[38]

Temple work commenced immediately after the dedication. Richard O. Cowan wrote, “No time was wasted in getting the temple into operation. The last dedicatory service took place Wednesday morning, 26 October, and the first baptism for the dead commenced that same afternoon. Endowments and sealings were inaugurated the following day.”[39] The temple district originally extended from Kansas to California and included everything south of the Utah/

As early as 1921, when groundbreaking for the temple was announced, the railroad was willing to offer special reduced rates for people wanting to attend this event.[42] The newspaper thought that completion of the temple “will be the means of bringing to this county many hundreds of people yearly who have in the past journeyed to the Utah capital,” and Mesa businessmen believed that the town would “experience a new activity . . . in every enterprise and commercial force.”[43] Even with this optimism, no one could have foreseen the impact the temple would have on Latter-day Saints in Arizona. The most important contribution, of course, is the personal genealogy and temple work itself. However, these two activities also stimulated the recording of personal histories. As Roberta Flake Clayton encouraged others in this endeavor, she left a wealth of information for descendants and historians. In 1969 when Mitzi Zipf listed the surnames found in PWA, she wrote, “This is not a complete list, but it serves only as an example of the names these women bore and the men they married who in those early years laid the foundation for much of the agriculture and other development of the [Salt River] Valley, and all of Arizona for that matter.”[44]

Pioneer Women of Arizona, both as Roberta Flake Clayton first published it in 1969 and as found in this new edition, is a testament to the pioneering experiences of women in Territorial Arizona.

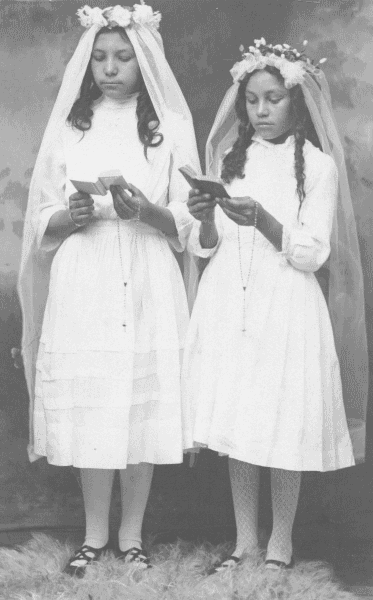

Hispanic Pioneers: Navajo and Apache Counties. Hispanic settlers were in most areas before Mormon pioneers arrived. Left: These unidentified girls are ready to receive first communion at Springerville. Right: the family of Henry H. Scorse. Scorse was born in England and immigrated to America in 1869. He traveled troughout the west before settling in Holbrook and marrying Julianita Garcia in 1881. She later shortened her name to Julia and used the English pronunciation. The children are (from left) Ellen, Henry Jr., Rose (baby), and Julia. Left photo courtesy of Fidencio Baca; right: Maryann Coulter.

Hispanic Pioneers: Navajo and Apache Counties. Hispanic settlers were in most areas before Mormon pioneers arrived. Left: These unidentified girls are ready to receive first communion at Springerville. Right: the family of Henry H. Scorse. Scorse was born in England and immigrated to America in 1869. He traveled troughout the west before settling in Holbrook and marrying Julianita Garcia in 1881. She later shortened her name to Julia and used the English pronunciation. The children are (from left) Ellen, Henry Jr., Rose (baby), and Julia. Left photo courtesy of Fidencio Baca; right: Maryann Coulter.

Notes

[1] For women who were not Mormons, see “The Federal Writers’ Project,” n. 79, 14. Those with limited Mormon ties include Ruth Ann Durfee, who was a member of the Church in Utah, moved to Nevada, and may have never been known as a Mormon in Arizona, and Rebecca Houghton and Mary Schnebly, who were baptized later in their lives; neither of their husbands joined.

[2] While living in Phoenix, RFC was open about her Church membership and worked tirelessly for its cause.

[3] Fischer, “Profile of Women in Arizona,” 42–53.

[4] Ibid., 42.

[5] Teeples, “First Pioneers of the Gila Valley,” 74–78. Although a few of the women who wrote autobiographies were very small children when they came to Arizona (e.g., Barbara Allen, Mary Helen Merrill, Avis Laverne Rogers, and Clayton herself), the earliest of the autobiographical sketches in PWA may be Cyrena Dustin Merrill’s—the main part of which was completed by 1898; Merrill died in 1907. In addition, some Mormon women kept journals (e.g., Lucy White Flake and May Hunt Larson).

[6] Fischer, “Profile of Women in Arizona,” 43, 45. Native Americans were counted separately in censuses, but Hispanics were not. Therefore, we assume that these statistics include Hispanic women but not Native American.

[7] Holbrook Tribune-News, August 23, 1935, and December 21, 1924, in Wayte, “History of Holbrook and the Little Colorado Country,” 287.

[8] Holbrook Tribune-News, August 23, 1935, in Wayte, “History of Holbrook and the Little Colorado Country,” 288. Charles Peterson’s description of A.C.M.I. business in Holbrook helps understand the limited Mormon presence there. He wrote, “Stubbornly eschewing all non-business associations with the Gentile community, Mormons neither brought their families to Holbrook nor boarded in town, but in most cases camped, summer and winter, in the store itself. Unable to make the long trip to their villages each weekend, they whiled away the burdens of isolated Sundays in tasks about the store. Thus, while the front door was closed, the back door was open.” Peterson, Take Up Your Mission, 152.

[9] Although this comparison may be true for women on isolated ranches, many non-Mormon pioneer women in Arizona were active in churches and community organizations. For example, see the description of pioneering in the novel Filaree (based on experiences of the author’s mother) versus Luckington’s description of Phoenix in 1878, which he said had “merchants and bankers, shopkeepers and saloonkeepers, doctors and lawyers, blacksmiths and carpenters, voice teachers and dance instructors.” Noble, Filaree, 3–12; Luckington, Phoenix, 21.

[10] Arrington, “Mormons in Twentieth-Century New Mexico,” Szasz and Etulain, Religion in Modern New Mexico, 108.

[11] Fischer, “Profile of Women in Arizona,” 47–48.

[12] See Happylona Hunt, 296; Mary Ann Farnsworth, 173; Anna Benz Kleinman, 372.

[13] The exception to this statement might be Louisa Cross, who served as a companion to Augustia Clark in Holbrook at the end of Clark’s life. 1910 census, Louisa Cross, Holbrook, Navajo Co., Arizona (but Louisa Cross is also listed as living in the home of her son, William B. Cross, in Holbrook). Also, some of the daughters of LDS pioneers worked in non-LDS homes before they were married. For example, Mrs. Pauline Barth in St. Johns employed Charlotte Kempe, daughter of Olena Olsen Kempe, 353, and Mrs. Sallie D. Hayden in Tempe employed both Cassandra Johnson (Pomeroy), 540, and Sarah Melissa Johnson (Pomeroy), 555, daughters of Sarah Melissa Johnson, 323.

[14] Sarah Lucretia Phelps Pomeroy, 547.

[15] A useful discussion of Mormon midwifery from an anthropological viewpoint is McPherson’s chapter 3, “Divine Duty: Midwifery at the Turn of the Century.” McPherson, Life in a Corner, 50–69.

[16] [Advertisement], Relief Society Magazine, 2 (September 1915): iii.

[17] Taylor, 25th Stake of Zion, 34; Palmer and Palmer, Taylor Centennial, 26. Apparently, a similar class was taught in Mesa, but the date is unknown; see Sarah Indiaetta Young Vance, 749. For a photograph of the Snowflake nursing class, see Emma Ellen Larson Smith, 672.

[18] Erickson, Story of Faith, 61; Derr, Cannon, and Beecher, Women of Covenant, 266–67.

[19] “Find Abandoned Babe in Hatbox on Desert,” Arizona Republic, December 25, 1931.

[20] An additional seven women were born in Arizona, so 115 (55%) of the 208 biographies were for women born in the West, A total of 169 (81%) women were born in the United States, and 39 (19%) were born in other countries (these figures include all women and not just Mormon women).

[21] See Presiding Bishop Edward Hunter’s list of supplies needed for two people coming to Arizona; Tanner and Richards, Colonization on the Little Colorado, 19.

[22] The widow Betsey Leavitt Hamblin was traveling with the extended John and Mary Adair Mangum family. Both a daughter and son of Betsey’s had married into this family. It is hard to understand from Alger’s description if there were eight wagon teams (with two being tandem) or ten. Some of this group became permanent residents of southern Apache County, and others eventually settled in northwestern New Mexico and southeastern Utah. History of Sarah Priscilla Hamblin Alger, holograph in possession of Sheryl Pursley Martin, copy in possession of Ellis.

[23] Elizabeth Adelaide Hoopes Allen, 41.

[24] Gustella Arminta Wilkins Larson, 389.

[25] May Louise Hunt Larson, 394, and Ida Hunt Udall, 743.

[26] Mary Agnes Flake Turley, 727.

[27] Ella Emily Burk Merrill Brown, 74.

[28] Lois Angeline Smith Bushman, 90.

[29] Annise Adelia Bybee Robinson Skousen, 656.

[30] Lucy Jane DeWitt Eagar, 161.

[31] Anna Dorthea Johnson Kempe, 351.

[32] Rothschild and Hronek, Doing What the Day Brought, 15.

[33] Kimball and Kimball, Spencer W. Kimball, 114.

[34] Peterson, Ninth Temple, 207.

[35] RFC Journal, October 27, 1927.

[36] Ibid., October 24, 1927.

[37] Ibid., October 25, 1927.

[38] Peterson, Ninth Temple, 164–65; also “Temple Ceremonial is Begun at Mesa,” Arizona Republican, October 24, 1927, 1, as quoted in Peterson, Ninth Temple, 170–73.

[39] Cowan, “The Arizona Temple and the Lamanites,” 60.

[40] “Three Excursions Make Trip to Latter Day Saint Temple,” Mesa Journal-Tribune, November 1, 1935. See also Nina Matilda Leavitt Porter, 558.

[41] For a detailed discussion of specific duties in each category, including temple workers who were volunteers versus “called,” see Peterson, Ninth Temple, 311−18.

[42] “Special R. R. Rates to Dedication of Mesa Temple Site,” Arizona Republican, October 25, 1921, 9.

[43] “To Start Work Next Month on L.D.S. Temple,” Arizona Republican, August 29, 1921, 3.

[44] Mitzi Zipf, “Meandering with Mitzi,” Sun Valley Spur-Shopper, July 10, 1969, 22−23.