Part 2: The Sketches

Roberta Flake Clayton

Roberta Flake Clayton, "Part 2: The Sketches," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 29-32.

Introduction to the First Edition

Roberta Flake Clayton

It has been suggested that the name Pioneer Women of Arizona under which these stories were collected and compiled be changed so that it might have a more universal appeal.[1] Accordingly, we take from the scriptures the beautiful story of Ruth when she said to Naomi, “Whither though goest I will go,” which was also the motto of the women who came with their husbands in compliance with the call of the presiding authorities of the Church represented at that time by the prophets Brigham Young and John Taylor.[2] This book is in truth a saga of the pioneer women of the Southwest.

Captain Kate Carter of the Daughters of Utah Pioneers suggested, after she read my mother’s story, that these others should also be published since they contain a great deal of hitherto unpublished Church history, tracing the ancestry of the women who accepted the Gospel in foreign lands and colonized in many places, as Brigham Young called them to do.[3] They were able to do what was expected of them because of their faith and loyalty to the constituted authority of the Church. This should prove of great value to the rising generation in our day of shifting values and mounting uncertainties. Where there is a current lack of stabilizing influence; we owe it to ourselves and our youth to share with them the strength of their forbearers, to give them examples to follow, hopes to cling to.

The lives of the pioneer women of Arizona stand as an eternal monument to greatness. Interwoven in the stories of their lives, they have left unsurpassed examples of courage and self-denial. These women were called from homes where the necessities of life were just beginning to come more easily after thirty years of pioneering in the Valley of the Great Salt Lake and in nearby communities and as it became safer from marauding Indian bands in the more remote localities, so they were inured to hardships. Had they not been, they could not have endured the ones to which they were subjected in this [Arizona] country.

Usually three months were required to make the journey here, this in covered wagons drawn by horses, or, in some cases, oxen.[4] Their wagons were their only homes and continued to be until forts were built into which they could move. Then, the only difference was that the wagon boxes were removed from the running gears of the wagon and placed in a more accessible position on logs or rocks to make them a little more safe from snakes, centipedes, tarantulas, etc., and [more convenient] so that getting into one’s house didn’t necessitate climbing over a high wagon wheel.

Death came to some of these pioneers and loved ones had to be left in wayside graves. One mother painted with her own hands the rude pine coffin in which her darling boy of three was buried.[5]

These were times and scenes that revealed true character, and the wives soon learned to smile through unshed tears to give courage to the men to carry on. Dancing parties, in which the great outdoors served as a pavilion and the only light the moon or blazing campfires, singing fests, and story telling kept alive the spirit of youth. No reference was made to friends or family left behind, and the only means of communication with them was when other pioneers came to join their ranks.

The nearest stores were weeks away and the prices almost prohibitive. Salt was obtained from not-far distant salt beds.[6] When an animal was killed, every particle of fat was saved, and that which was not considered fit to eat was made into soap by the aid of lye condensed from cottonwood ashes. Candles were also made from the tallow. Starch was made from grated corn or potatoes; dyes were made from roots and barks. These latter also furnished medicines, and some of the women became excellent nurses, claiming that for every ill there was a remedy provided by nature. Nature was very kind to these children of hers so far from doctors and drug stores.

The wool from the sheep was used for mattresses and carded for quilts which were carefully pieced from every scrap of cloth.[7] Yarn was spun, and the stockings, scarfs, gloves, and mittens were knitted from it. When wearing apparel could be no longer worn, it was dyed, torn in narrow strips, and woven into carpets or braided into rugs to cover the rough pine or dirt floors.

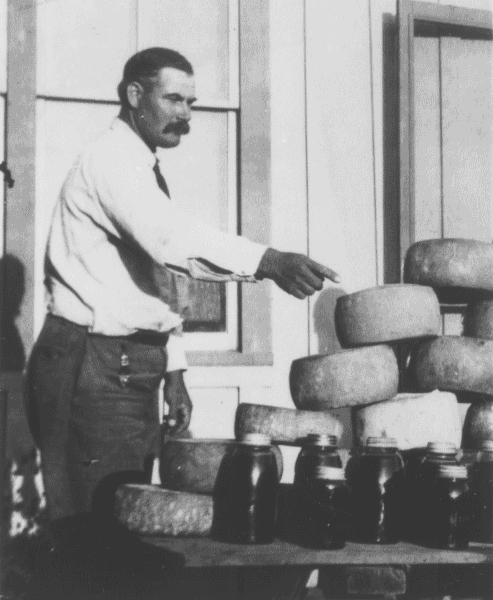

Meat was cured in the smoke of smoldering corn-cob fires. Cheese and butter of excellent quality were made by many housewives. Corn was cut from the cob and dried. Peas, string beans, and squash were dried to give variety to winter menus as well as to conserve the food supply. Hats were braided from straw. Straw and corn husks were used for beds for those who could not afford wool. Pillows were made from the feathers of chickens and from the wild geese and ducks that in the fall were plentiful.

County Extension Agent, Charles Fillerup, with homemade cheeses and honey at the Navajo County Fair, c. 1925. Photo courtesy of Albert J. Levine Collection, Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

County Extension Agent, Charles Fillerup, with homemade cheeses and honey at the Navajo County Fair, c. 1925. Photo courtesy of Albert J. Levine Collection, Stinson Museum, Snowflake.

The furniture was all homemade. The bed springs consisted of rope woven lengthwise and crosswise of the strong, if not beautiful, bedstead. The squeaks and groans these slackened or tightened cords made at every movement of the occupant would give the impression of the remorse of haunted souls. Trundle beds were concealed under the larger beds in the daytime by valances whose whiteness or dinginess betrayed the degree of cleanliness of the housewife. In some homes where one room served for all purposes, the bedsteads were canopied and curtained, giving the occupant comparative privacy.

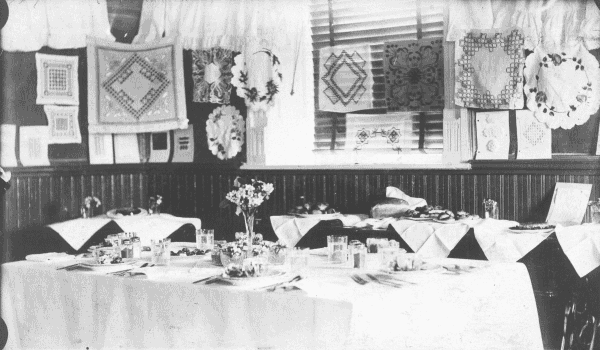

The home and the apparel were adorned by the workmanship of the owners with a certain rivalry as to who could make the most of the little they had. Beautiful laces were crocheted and knitted to trim pillowcases, dresser scarfs, and the half dozen white petticoats which every girl and woman must wear to be considered “well-dressed,” though these same articles were made of flour sacks or of a course fabric known as “domestic,” bleached to a snowy whiteness by frequent washing and then spread on grass or snow and exposed to the rays of the sun.[8] “Tidies,” crocheted or knitted of cotton, helped to make attractive the calico covered, “overstuffed” homemade chairs and couches.[9] Some elegant bedspreads were tufted with candlewick, and quilts of intricate design and quilting gave an air of beauty to the home.

The cultural part was not neglected in the life of the pioneer women. What books there were, were cherished, and before they were loaned, the backs were carefully protected by covering them with cloth. Home theatricals were a favorite source of entertainment, many of the plays being written by local people. Every talent was cultivated and used for the benefit and pleasure of all.

Handiwork from Pearl Potter's students at the Snowflake Stake Academy, 1907-1908. Photo courtesy of Karen Schuck LaDuke.

Handiwork from Pearl Potter's students at the Snowflake Stake Academy, 1907-1908. Photo courtesy of Karen Schuck LaDuke.

Perhaps it was this need for human resourcefulness which made these women strong not only in things requiring physical strength but in things requiring spiritual greatness as well, companionship and neighborliness, of endurance, and of a thankful heart, and this they bequeathed to their children and their children’s children. Rich is the heritage of the descendants of these brave and noble pioneer women.

Notes

[1] Although RFC called this a foreword, it is really an introduction to PWA.

[2] Ruth 1:16.

[3] When RFC writes “my mother’s story,” she is probably referring to her book, To the Last Frontier; however, today a better source for information about Lucy Hannah White Flake is Flake and Boone, Diary of Lucy Hannah White Flake. Kate B. Carter, a long-time editor, historian, and president of Daughters of Utah Pioneers, was born Catherine Vigdis Bearnson in 1891 and married Austin Carter in 1914. She was a charter member of the Spanish Fork DUP and later moved to Salt Lake City. In 1930, she was asked to prepare lessons and was soon asked to be assistant historian for the Central Company board. She served as president from 1941 until her death in 1976, https://

[4] Although three months was a reasonable length of time for the trip from Salt Lake City to Arizona, it usually only took four to six weeks with a heavily laden wagon from Kanab or St. George. The amount of time for the trip depended upon whether loose cattle and horses were being trailed and whether oxen or the faster mules or horses were used. See n. 69 for Margaret Ellen Cheney Brewer, 62; Ellis, “‘Arizona Has Been Good to Me,’” 1–32.

[5] RFC is here describing her own mother. Osmer Flake wrote, “In May, George, the youngest son, was taken sick and gradually grew worse, in spite of all Mother could do. . . . Day and night, she watched the suffering of her baby boy. . . . What wonder, that on July 6th [1878], she walked out alone behind a bush, where she would not be seen by staring eyes, and offered a simple prayer, asked the Lord to relieve his suffering even if it be in death. She calmly returned to the bed side. He looked up at her with a sweet smile; the pain was gone, he closed his eyes and the spirit had taken its flight. Her fourth boy had died. Reverently she washed the body and fixed it for burial. Just then, the glad cry of the children told her that Father had [returned]. . . . He prepared a casket, and Mother sewed every stitch of the burial clothes and dressed the body. When she saw the rough casket, (they had no plane to smooth the lumber) she asked that the body be not put in now. She hunted around through the wagons, and found some paint, and the casket was painted the best [she] could do it. On July 7th, a small group of mourners followed the body to the cemetery at St. Joseph.” Flake, William J. Flake, 64−65.

[6] When settlers along the Little Colorado River wanted salt, they usually traveled to Zuñi Salt Lake in New Mexico, about thirty-three miles east of St. Johns. McClintock reported that some freighters would come back with as much as two tons in one load. McClintock, Mormon Settlement in Arizona, 156.

[7] Louise Larson Comish described the process of making mattresses: “Well do I remember the busy brown fingers of the Indian woman, Fanny Adair, who came to the house to card the wool into soft pats—a great pile of them, like a wall a foot thick and three feet high—the pats looking like little soft bricks. Out of them, she and mother [May Hunt Larson, 394] made the splendid mattress that served on my parents’ bed for many years.” Comish also added, “This wool father had sheared from our own sheep. Mother had washed it clean of dirt, grease, and odor, dried it in Arizona’s undiluted sunshine and fresh breezes, and packed it away in sacks till enough was accumulated for her purpose.” Comish, Snowflake Girl manuscript, 2.

[8] Thrifty Mormons reused flour sacks, and when the girls washed their underwear and hung it out to dry, sometimes you could read “Pride of Denver” in big red letters; at other ranches, the underwear would say, “Pride of Colorado,” “Butterfly,” or “Sea Foam Fancy Flour.” Joseph Pearce, an early Mormon cowboy, Arizona Ranger, and son of Mary Jane Meeks Pearce (519), said that when the cowboys rode through the small Mormon villages, they would say, “What brand of flour are you goin’ to dance with tonight, Joe?” Joseph Pearce Reminiscences 1903−1957, MS 0651, AHS, 45.

[9] Tidies were also known as antimacassars and covered the arms, back, or headrest of a chair or sofa, protecting these areas from wear and soil.