Part 1: Introduction to This Edition

Catherine H. Ellis and David F. Boone, "Part 1: Introduction to This Edition," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 1-28.

Roberta Flake Ramsay Jordan (Acklin) Clayton

Catherine H. Ellis and D. L. Turner

Maiden Name: Roberta Flake

Birth: August 19, 1877, Beaver, Beaver Co., Utah

Parents: William Jordan Flake and Lucy Hannah White

Marriage 1: Joseph C. Ramsay, September 9, 1896 (div)

Children: Reginald Milton (Ramsay) Flake (1898)

Marriage 2: William Henry Acklin, aka Henry Jordan, about 1909 (div)

Marriage 3: James William Clayton, September 25, 1910 (Colonia Juárez, Mexico), remarried November 25, 1910 (El Paso, Texas)

Children: James William Clayton Jr. (1919), Natelle Clayton (1920), Robert Dennis Clayton (1930), Richard Flake Clayton (1930). All children adopted.

Death: January 12, 1981; Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Roberta Flake Clayton made an important contribution to the history of Arizona by collecting approximately 300 biographical sketches from early settlers. Most of these sketches have been published in two books: Pioneer Women of Arizona (1969) and Pioneer Men of Arizona (1974). Using these sketches, Clayton has been quoted by authors at every level of Arizona and LDS history: private individuals, undergraduate students, professional academics, and Latter-day Saint historians.

Clayton’s life was intricately woven with the history of Arizona and mirrored the development of the territory into a state. When Osmer D. Flake wrote about his father, William J. Flake, and the settlement of northeastern Arizona by members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, he said, “Strong men were needed to settle the Saints in Arizona and extend the settlements to the South. Some had been called, others volunteered . . . , some stayed, and many returned.”[1] In the Flake caravan that left Utah for Arizona on November 19, 1877, was three-month-old Roberta, daughter of William J. and Lucy Hannah White Flake. Osmer described the caravan as consisting of “six wagons, (loaded with provisions and household goods, farm tools, etc.) pulled by nine yoke of oxen and seven span of horses. There were also two hundred head of cattle and forty loose horses.”[2]

Thus, Roberta Flake came to Arizona and grew to adulthood in the newly colonized town of Snowflake located on Silver Creek, which was part of the Little Colorado River drainage. She attended the Snowflake Stake Academy and enjoyed acting in plays produced by the school and her brother for his home drama club.[3] In 1896 she married Joseph Ramsay, also from Snowflake.

Roberta Flake, about 1895. Photo courtesy of Jannie Lisonbee.

Roberta Flake, about 1895. Photo courtesy of Jannie Lisonbee.

Despite what may be considered a mainstream LDS beginning, Clayton’s life was not typical of most Mormon women today. About 1904, she divorced her husband and described her experience in 1973: “I had had eight years of H-E-L-L, H E double L, with a man that was untrue to his principles and untrue to everything, and I had endured that kind of a life until I could stand him no longer. . . . I was in New Mexico [in a] sanitarium [when] I left him.”[4] Previous to this divorce, they had adopted a baby boy. Born to an itinerate couple in Snowflake on January 24, 1898, they named him Reginald Milton Ramsay, although later in life he was known as Reginald Milton Flake.[5]

After her divorce, RFC worked for about a year in California and then traveled to Chihuahua, Mexico, to work as an English and Spanish tutor for a private family. She was briefly married to Henry Jordan, a man with a hidden past whose real name was William Henry Acklin.[6] Then in Ciudad Chihuahua, she met James William Clayton, a man whom she called J. W. or Billy. She described her husband as “an old bachelor fifty-eight years old and a very attractive Southern aristocrat who never did a lick of work in his life”; presumably she was referring to physical labor. She further recalled that J. W. made his first money by taking American cattle across the Texas/

The couple was first married by RFC’s brother-in-law Peter C. Wood in Colonia Juárez, and then two months later they traveled to El Paso, Texas. Here they were married again on November 25, 1910, because RFC wanted to make sure the marriage was legal in the U.S. The couple immediately returned to Clayton’s mine in Chihuahua. They lived through many of the tumultuous events of the Mexican Revolution, sometimes fleeing to El Paso for safety. They finally sold the mine in 1915.[8]

The Claytons lived for a short time in northeastern Arizona after leaving Mexico and then moved to Ellijay, Georgia, where J. W. Clayton again had mining property.[9] They adopted two children while in Georgia: a son, James William Clayton Jr. (usually called Bill to distinguish him from his father, Billy), born August 5, 1919, and a daughter, Natelle, born December 23, 1920.[10] In 1922, the family moved back to Arizona and built a home in Phoenix at 2310 East Willetta Street.[11]

Roberta Flake Clayton, probably while living in Georgia, about 1920. Photo courtesy of Jannie Lisonbee.

Roberta Flake Clayton, probably while living in Georgia, about 1920. Photo courtesy of Jannie Lisonbee.

RFC was always intimately concerned with the activities of other women, beginning with her mother, Lucy Hannah White Flake. Because both of Lucy’s older daughters married young, RFC became her mother’s confidant, and the two worked together to complete all the women’s work in a pioneer household. But Lucy died January 27, 1900, at age fifty-seven, only four years after RFC’s marriage to Joe Ramsay. RFC wrote, “Before the passing of my angel Mother she gave me her journals and the sad duty of completing the last chapters. No words of mine can do her justice. I feel about her as she expressed in her journal when her Mother passed away.” Eventually, RFC produced To the Last Frontier, which she called an autobiography but which today would be called a biography.[12] She wrote, “In the summer of 1923 [1926?] I decided to make copies for each of Mother’s children. I knew the other sisters and brothers would prize them as I did, besides the yellowing leaves and fading ink, along with much handling which the books had gone through, made me note they would have to be copied if preserved.”[13] She began this task noting on July 11, 1926, that she had “just finished the first page of Mother’s journal.” Of this process, she wrote, “I went thru the sacred pages and selected the vital things and the ones of most importance to all and condensed them.”[14]

Also in 1924, RFC was part of a group of women who met at the Rex Hotel in Mesa to organize a camp (or chapter) of the DUP. She was elected historian and encouraged the members to write about the lives of their pioneer ancestors. On October 23, 1929, she wrote in her journal, “After I came home [from a DUP meeting] I got the inspiration to compile a book of the lives of Pioneer women of Arizona, and that I am going to try to do.” She wrote about corresponding with Kate Carter, president of the DUP who “suggested, after she read my mother’s story, that these others should also be published since they contain a great deal of hitherto unpublished Church history, tracing the ancestry of the women who accepted the Gospel in foreign lands and colonized in many places.”[15]

J. W. and Roberta Clayton lived in luxury in Phoenix, although financial worries plagued them well before the Great Depression. By 1930, they had four boarders and sometimes William J. Flake living with them.[16] Nevertheless, they adopted two more children in 1930: Robert Dennis Clayton, born June 21, 1930, and Richard Flake Clayton, born November 5, 1930.[17] In 1932, the Claytons lost their home in Phoenix, and RFC moved back to Snowflake with her children. She lived in a portion of the original adobe Stinson home of her childhood, and, as with many others during the Depression, she was able to subsist with a milk cow, a garden, a few chickens, and the occasional beef that William J. Flake and his son James M. provided to the widows and the poor.

About this same time, Billy Clayton and his stepson, Reginald Flake, went to Mexico to look after mining interests that had reverted to the Claytons. For two years, J. W. sent “cheery letters” to her. She said he would write “at last we are about to see daylight” or “we are almost over the top now,” but no money came to help support the family. Then RFC received a telegram stating that her eighty-four-year-old husband was very ill and in the hospital. She took the next train to Chihuahua but, upon arrival, found him dead and buried. “The laws of Mexico,” she wrote, “require[d] interment within twelve hours after death.”[18] J. W. Clayton died August 25, 1935, in Ciudad Chihuahua; RFC said, “We had lost everything.”[19]

As a widow needing to support her children, Clayton turned to writing. Earlier, she had enjoyed creative writing as a young woman. In the 1973 oral history interview, RFC said that the first item she ever published was in the St. Johns newspaper after attending a dance (about 1895) and then she wrote a “Mr. and Mrs. column,” apparently news from Snowflake, for the same newspaper. She wrote pageants, short stories, poetry, and a journal. Some of her poetry was published in the Arizona Republican.[20] One poem, “Playing Dominos,” was later included in Mary Boyer’s Arizona in Literature.[21] She was always pleased with the recognition but would have preferred money.

About 1922, RFC had enrolled in a Palmer Photoplay Corporation correspondence course for screen writing. Palmer Photoplay was one of the first companies trying to make a profit from struggling writers desperate to publish. She never sold a screenplay, but some of her writing was influenced by the criticism she received from the instructors at Palmer. In June 1923, John Branch Timms, commenting on the difference between narrative and dramatic writing, said, “NARRATIVE is applied to stories that are . . . a series of incidents or lengthy descriptions. DRAMA is conflict or soul struggle.”[22] Sometimes, at least for RFC, using a short story/

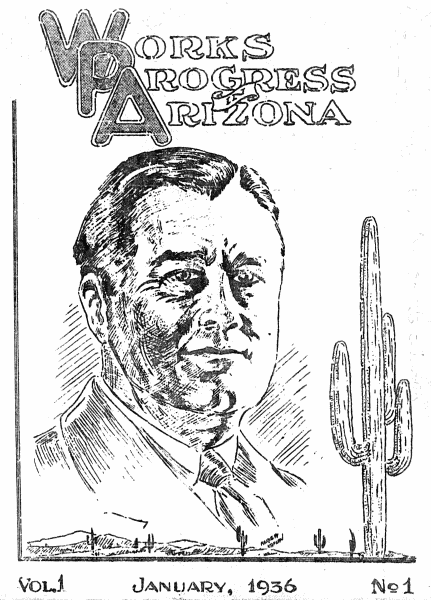

With a writing background, and needing money to support her children, RFC began about 1936 to participate in the Federal Writers’ Project, a New Deal program designed to give out-of-work authors some income during the Great Depression.[24] As part of this group, she was under the supervision of Ross Santee, a noted regional cowboy illustrator and author.[25] She submitted seventy-nine biographies for Arizona women and seven for Arizona men recalling, “I had no other means of support and I got thirty-five dollars every so often for an article.”[26] Many of her subjects were Utah colonizers who settled in Navajo County, and therefore people that she had known from childhood. However, she also submitted DUP sketches from Maricopa County, and she interviewed and wrote sketches for seven non-LDS women.[27]

But Clayton contributed more than just short biographies to the FWP. In fact, the biographies were perhaps not her first contributions.[28] In 1936, under the rubric “Navajo County Guide,” she wrote a description for every town in Navajo County (including those on the Navajo Reservation). Accounts varied, but many included name, location, altitude, history, when the post office was established, teachers and schools, government, commerce, accommodations, transportation, theaters, parks, public buildings, hospitals, community life, and points of interest. For some of these accounts, she included a list of “authorities” she had consulted (both people and books) that provide references for her information. Unfortunately, very little of this information was included in the book, Arizona: A Guide to the Sunset State, which was published in 1940. This may be due to the fact that the format for the book emphasized the larger cities in the state, and the topics RFC wrote about were mostly not covered.[29]

Clayton also contributed other interesting essays to Arizona’s FWP. Under the topic “America Eats,” she described pioneer methods of cooking meat; how pioneers made cheese, cottage cheese (also called Dutch cheese), and butter; the ways they preserved vegetables (including making sauerkraut); and the types of meats they ate. She described reloading cartridges; making candles, mattresses, rugs, hats, and soaps; curing meats; and using herbs and simple home remedies. She described “A Typical Day in a Pioneer Woman’s Life” (based on her mother’s life) and wrote about the Madonna of the Trail statue in Springerville. Under the topic of “Folklore and Folkways,” she mentioned rodeos, a wishing well at the Hotel Posada in Winslow, a lover’s lane in Snow Flake, the Future Farmers of America-sponsored autumn fair in Navajo County, dedicatory prayers at dams and chapels, and quilting bees. Because RFC was an expert horsewoman and grew up on the ranges of northeastern Arizona, she also contributed several essays about cowboys including “Cowboy Sayings and Amusements” and “Cowboy’s Work, Wages and Outfit.”

RFC lived an additional forty years after the FWP ended and continued to collect information about Arizona pioneers. She limited her scope to Arizona saying, “It’s only Arizona that I’m interested in.”[30] In the mid-1960s, she used seventy-one of the FWP sketches and added 127 more for a book she titled, Pioneer Women of Arizona.[31] Floyd and LeOla Rogers Leavitt of Scottsdale recalled that Clayton went door to door in Mesa selling the book to relatives of her subjects. Her second book, Pioneer Men of Arizona, was edited by nephew Chad J. Flake and published in 1974. A niece, Fern Flake Fairborn, remembered a sign on RFC’s front lawn advertising the books for sale. Undoubtedly, she hoped to supplement her meager pension with these sales.

William J. Flake, about 1908, with all of his living children from both marriages except Jane Wood (817), who was probably in Mexico. Both of William J.'s wives, Lucy (189) and Prudence (194), were deceased. Front row (left to right): Mary Turley (727), Pearl McLaws (Ellsworth), Annabelle (Rogers), Roberta Ramsay (Clayton), Emma Freeman, and Wilmirth Willis; back row: John T., Osmer D., William J. (father), James M., and Joel Flake. Photo courtesy of Cleone Solomon, James M. Flake Home.

William J. Flake, about 1908, with all of his living children from both marriages except Jane Wood (817), who was probably in Mexico. Both of William J.'s wives, Lucy (189) and Prudence (194), were deceased. Front row (left to right): Mary Turley (727), Pearl McLaws (Ellsworth), Annabelle (Rogers), Roberta Ramsay (Clayton), Emma Freeman, and Wilmirth Willis; back row: John T., Osmer D., William J. (father), James M., and Joel Flake. Photo courtesy of Cleone Solomon, James M. Flake Home.

In the early 1940s, RFC and her three youngest children lived in Provo, Utah, where daughter Natelle attended college. During World War II, son Bill enlisted in the navy and served as a fireman. His death date is listed as February 27, 1942.[32] Although Bill enlisted in Phoenix, he had attended high school in Snowflake, so Principal Silas L. Fish honored Bill along with other area casualties, although the story is slightly incorrect in the poem: “Bill Clayton was among / The naval force to dare. / His ship [the USS Langley] they sank, and when / Survivors got on board / A second ship, ’twas sunk, / So thick the Nippon hordes. / A third ship picked up some / Who did escape the two; / But it in turn was doomed, / The Japs sank that ship too.”[33]

Post WWII, RFC bought an acre of land in Mesa, Arizona, (on Alma School Road) with the compensation from Bill’s military service. Here she lived for a time in a tent with an outhouse constructed from a wooden refrigerator or freezer shipping box. Friend and builder Fred Johnson eventually found an old house, and he moved it onto the property for her. She said, “Then we built a room on, and . . . I had a two-story adobe house.”[34] When developers wanted this property to build a medical center, she traded it for a house at 221 South Hobson in Mesa, where she lived until after she fell and broke her hip (sometime before 1973). She then spent time recuperating in the home of her daughter Natelle Murdock, but at age 100, RFC was using a wheelchair and living independently in her own home “with the help of Reg, her son, who lives next door to her[,] and numerous nieces.”[35]

RFC died January 12, 1981, at her home in Mesa. She lived to be 103 years old.[36] Throughout her life, she was recognized as one of the original Mormon pioneers in northeastern Arizona and was honored as the last remaining pioneer at Snowflake’s centennial celebration in 1978.[37] She is also memorialized as the babe in her mother’s arms in the statue on Main Street in Snowflake today.

Two assessments of Roberta Flake Clayton’s contributions to the history of Arizona come from newspaper columnists Walter and Mitzi Zipf. Dorothy “Mitzi” Zipf worked her entire life as a reporter for the newspapers of Arizona and moved to Mesa in 1951.[38] After retirement, she and her husband, Walter, worked for Mesa’s Sun Valley Spur-Shopper. In 1969, Mitzi Zipf was writing the column, “Meandering with Mitzi,” which often included pieces about people in Mesa (particularly early pioneers), Mesa social life, and local archaeology. For a July 10 column, she featured RFC and her new book, Pioneer Women of Arizona. Zipf said, “Reading the names of those included in the book—more than 200 of them—is like reading a roster of names well known in the Valley today—Allen, Baird, Ballard, Berry, Biggs, Bourn, Brewer, Brown, Bryce, Cluff, Curtis, Decker, DeWitt, Driggs, Eagar, Ellsworth, Fish, Flake, Fuller, Gibbons . . . and on and on, clear through the alphabet.” After reading all 716 pages of the book, which RFC was selling for $10, Zipf concluded that “Mrs. Clayton has done a monumental service to this history of the state in compiling these stories just as the women themselves did in pioneering the land which has become Arizona.”[39]

Then, as Roberta Clayton neared her centennial birthday, Walter Zipf also wrote a column extolling her virtues. He called her “an exceptional Arizona pioneer of unusual literary attainments and frontier experiences” and wrote of her “countless plays, pageants, and poems and five . . . books.” In a list of her literary accomplishments, he noted that she had written the words to an opera, “America’s First Easter,” which, in the late 1920s, was produced twenty-one times in the Phoenix Union High School stadium. His final assessment of her literary contributions is also our assessment: “Her literary accomplishments are the more striking because of the limitations on formal education placed by frontier conditions.”[40]

Anthologies and Pioneer Sketches: Editorial Methods

It is the nature of anthologies, unless heavily edited, to have unequal entries, and Pioneer Women of Arizona is a classic anthology. Although RFC wrote some sketches from personal knowledge or interviews, she simply collected others. Authorship of some of the collected sketches is unknown, others are in part or wholly autobiographical, and some were written by children or grandchildren. Some of the sketches are brief, and others are very detailed. Some of them have significant information about early Arizona settlements, while other sketches emphasize family dynamics. Additionally, some of the biographies have two or three earlier versions: there are FWP sketches at ASLAPR in Phoenix, some early PWA sketches are found in Pioneer Women of Navajo County at the Mesa FHL, and a few are at the CHL filed under the subject’s name.[41] With this in mind, it is easy to understand Mary-Jo Kline and Susan Perdue’s description of editing a multiple-text document as “a special form of purgatory,” and it was concluded that this publication must be a new edition and not a documentary editing project.[42]

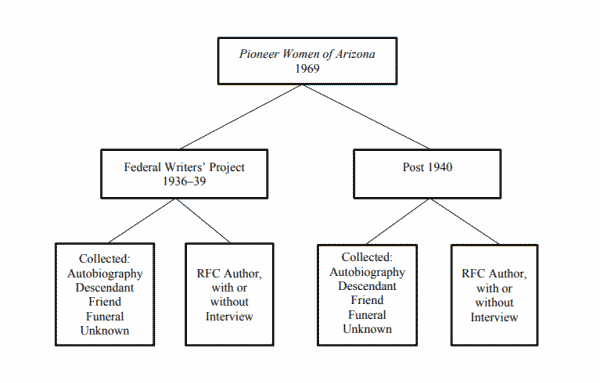

Origin of sketches as found in Pioneer Women of Arizona.

Origin of sketches as found in Pioneer Women of Arizona.

Transcription and Source Documents

Individual accounts in PWA have been typed multiple times, and there may not be a holographic copy of any sketch. Typographical (and other) errors have been introduced at every stage: the 1920s DUP sketches, the 1930s FWP sketches, the 1960s typing of PWA, and the 2011 typing for this edition. Spelling, punctuation, and formatting are generally better in the FWP sketches (which Clayton typed) than in PWA (which she did not type). In 1973, Clayton stated that she was “paying for the work that I’m getting done by Mrs. Leslie.[43] She does as much erasing as she does typing. I don’t know what I could get a real stenographer for. I guess it would be beyond me.” Mrs. Leslie had been part of the family for fifteen years, so it is likely that she was the typist for PWA.[44]

As Kline and Perdue noted, “Most editors compromise to one degree or another between a detailed diplomatic text and a clear reading text.”[45] Documentary editing ranges from typographic facsimiles to diplomatic transcriptions to expanded transcriptions. In recent decades, documentary editing has moved from liberal to conservative and from silent emendation to overt.[46] As much as the trend is to use a very conservative format, PWA falls into Kline and Perdue’s category of “historical documents that have little claim to literary merit.”[47] PWA is also a multi-text document, particularly those sketches that were originally submitted to the Federal Writers’ Project. Kline and Perdue state that usually “the most nearly final version of a document is the preferred source text,” but PWA is rife with errors in punctuation and spelling.[48] In addition, RFC’s form of abridgment when moving a long FWP sketch into PWA was to simply leave out sentences or paragraphs (thereby leaving the reader confused). These deletions have been reinserted.[49]

The decision concerning silent emendations ultimately revolves around the “barbed wire” nature of heavily edited texts. Also, the amateur-writer status of all who contributed to PWA and the problems with the typing make this text fit into Kline and Perdue’s discussion of slave narratives. They suggest that John W. Blassingame’s introduction to Slave Testimony: Two Centuries of Letters, Interviews, and Autobiographies is still a useful format. He wrote that his text did not depart from the text of the original documents, “but, since nineteenth-century printers are notorious for mutilating words, all obvious typographical errors in published sources have been corrected silently. The alternative of using sic when the letters in a word such as the were transposed seemed unnecessarily pedantic.”[50] These statements are also true for PWA when “PWA typist” is substituted for “nineteenth-century printers.”

For this edition, spelling and punctuation have been standardized, with the exception that some English spelling has not been changed to American spelling (e.g., moulding was retained). “Mother” and “father” have been capitalized when they are used as proper names; they are lower case when used as “my mother.” Names have been changed to the spelling normally used by the family, because there is no way to know if the spelling in PWA is from the family, from RFC, or from the typist; multiple ways of spelling are noted. Today, the accepted abbreviation for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is the Church, but in the past, lay members and historians alike have used the LDS Church, the L.D.S. Church, and the Mormon Church. We capitalized church when it was an abbreviation for the official name; we made it lower case when the reference was to the general organization; we did not update the older abbreviations in the sketches, but we did update the capitalization. We did not update the term Arizona Temple, because the temple at Mesa was the only Latter-day Saint temple in Arizona during the period this book covers, 1880–1969.

Other silent emendations involve one-sentence paragraphs and run-on sentences. One-sentence paragraphs were often included with the previous or following paragraph, but sentence order was not changed; run-on sentences were sometimes divided into two or more sentences, but word order was retained. Words that today would be seen as derogatory, however, were changed. Usually these were racial words, particularly for Blacks and Native Americans. These were commonly used terms in the early twentieth century, sometimes used with prejudice and sometimes not, but they are simply unacceptable today. These changes are always shown in brackets.[51] Finally, although today the name of the town of Snowflake is spelled as one word, it was often spelled as two words (Snow Flake) as late as the 1930s. The spelling for Show Low was just the opposite; in the beginning it was often spelled as one word—Showlow. Both have been left as in the original text.

Typographical errors were sometimes difficult to identify. The modus operandi was to ask, “Does this sentence make sense?” If the answer was no, the sentence was looked at more closely. Sometimes there was a misspelled word; other times an entire line had been left out (i.e., in the FWP to 1960s typing or in the 1960s to 2011 typing). FWP sketches were helpful in answering some questions; most of the FWP sketches have been microfilmed, and those not filmed can be searched.[52] Occasionally, the meaning had to simply be thought out. For example, one couple was described as being stranded in central Utah with a “hockey” team. After some deliberation, it was decided that it should have been “hackneyed” team.[53] Another example was the use of the word “pockets” in a discussion about the Civil War; after reading the entire paragraph, it was apparent that this should have read “pickets.” For the first example (Malinda Lisonbee), there was no prior manuscript to consult; for the second example (Susan Youngblood), an FWP sketch existed with the correct word. A bracketed word with a question mark was used where there was more than one possibility for the correction. Another example of errors corrected and noted occurs in the sketch for Ann Horton Matthews Holladay. The author stated that the land at San Bernardino, California, was “bought from a Mexican Dan Antonino Mario Lupo for $775.” This should have read “bought from a Mexican, Don Antonio Maria Lugo, for $77,500.”[54] Unfortunately, some errors like this may have been missed.

Formatting for this Edition

The title of each sketch is the woman’s name with the spelling as normally interpreted by the family today. For example, in Arizona, Mormon families with the surnames of Eagar, Holladay, Blain, and Ramsay use these spellings, but there are both Crandalls and Crandells; Merrills and Merrells; Woolleys and Wooleys; and Robinsons, Robisons, and Robsons. In the title, we list all given names, the maiden name, and all married names. The exception to this rule is Johanna Erickson Westover, who did not use her second married name, Despain, in her lifetime nor did her children.

The author of the sketch is listed below the title. When RFC published PMA, she wrote, “I requested that the stories sent in be signed by the ones who contributed them. The stories that are not signed are the ones I wrote and edited myself.”[55] Unfortunately, this was not followed when PWA was published. Authorship was sometimes recorded; for other sketches, the author can be identified internally (e.g., “my mother”), from Pioneer Women of Navajo County, or from other sources. The rest of the sketches are listed as Author Unknown; it cannot be assumed that RFC wrote these sketches, although she was undoubtedly author for many.

Genealogical information at the beginning of each account usually came from Ancestral or Pedigree Resource File entries at FamilySearch.org. Although FamilySearch.org is not always accurate, the size of this project and the limited number of original records made this the only recourse. In 2015, Arizona death certificates were open through 1964 and available online, so that source was checked for each woman. Discrepancies, including no death certificate filed, were noted.[56] Particularly difficult to find were children born between 1900 and 1910. This is before births and deaths were recorded in Arizona. Sometimes a child was born and also died between the census years, and other times the child was still alive when FamilySearch.org databases were formed.[57] The Mormon convention of using quotation marks around a single letter in a name was not used. Therefore, a letter and period will occasionally mean that the full name is not known, and at other times, it is simply an initial (e.g., Peter “O” Peterson becomes Peter O. Peterson). Cross referencing information on a particular family, both within this volume and also to PMA, was added.

Bibliographic information within a collection of sketches this size requires some modifications. Full citations to books and articles are only in the bibliography. Citations for newspaper articles only appear in the footnotes. Census information is found only in the footnotes and only lists the year, head of household, town, county, and state because most people now use databases (e.g., ancestry.com). Other information from online sources is also found only in the footnotes. Because individual sketches will likely be read independently, there is some duplication in the footnotes, although an individual or concept is defined at first mention.

Additional Information

At the end of each sketch, comments from Ellis and Boone were added which include additional stories, background information, or significant information not reported in the text. Sometimes this information helps put the subject’s life into perspective, sometimes it adds information about the family or community, and sometimes it gives information to help understand the sketch. Generally, information was limited to items directly related to women’s issues. Although it was not surprising to find a larger number of stories available for pioneer men than for women, the extent of this difference was significant. Information about a husband was not added unless it was specifically related to the sketch or to women’s issues.

Migration information in each sketch was checked against two databases. MPOT often yielded good information, but PWA was used as one source for that database. Occasionally, the Mormon Migration database at Brigham Young University proved useful. Information on ocean crossings is from Conway B. Sonne’s two books about Mormon maritime history and some online records.[58] Generally, DUP sources were not used—neither sketches submitted by descendants nor DUP publications.

Cautions

To correctly interpret many of the accounts in PWA, it is imperative to remember that “widowed” or “lost her husband” often means divorce rather than death of a spouse. It is impossible to know if Clayton was using a shortened version of “grass widow” or if she was simply avoiding the mention of an unpleasant incident.[59] Occasionally, she used euphemisms like those used in the nineteenth century for pregnant. Divorce records were not looked up for this project, but it is important to recognize the high incidence of divorce among polygamous marriages.[60] If the divorce is mentioned in the sketch or at FamilySearch.org or if it appears that a divorce occurred and there is some documentary evidence (such as divorce reported in a census record), “(div)” was placed after a marriage date. If a husband and wife were living apart for an extended number of years and it appears that they may have divorced, a question mark was included (i.e., “div?”).

A second caution would be to note the differences between Mormon and Native American interactions in Utah and in Arizona. Many of the PWA women lived in Utah during the Black Hawk War (1865−72).[61] Central Utah was sparsely settled, federal troops were not always willing or available, and Black Hawk and his followers had assumed the offensive. This became a citizen militia war with probably more Anglo cattle herders killed than militiamen and more Native Americans killed than settlers. Carlton Culmsee noted that “not only men but women and teenage boys and girls and younger children were drawn into defense as participants.”[62] He also described raids against the settlers’ herds of horses, cattle, and sheep, and said, “The Indians strove to wear down the enemy by exhausting the whites’ physical and psychological resources while replenishing their own.”[63] Brigham Young’s policies toward Native Americans might be summarized by the aphorisms “send missionaries” and “better to feed than fight.”[64] Cedenia Willis remembered seeing the bodies of Joseph, Robert, and Isabell Berry who were killed in early April 1866 east of Cedar City.[65] The most disturbing Native American encounter reported in PWA comes from Utah in the winter of 1848–49.[66]

In northern Arizona, the only Mormon death at the hands of Native Americans was that of Nathan Robinson, husband of Annise Robinson Skousen. Settlers in the Gila Valley, however, suffered much more from Native American aggression than did Mormon pioneers in other areas.[67] Most of the women in these sketches brought their fears of Native Americans to Arizona, even though Mormon settlements were generally not in areas inhabited by Native Americans, and by 1886 Geronimo and other Apaches were in Florida and Oklahoma.[68] The more interesting items about Native Americans in PWA are not the stereotypical fears, but the attitudes that made Mormons unique. Even before Church members moved to the Rocky Mountains, missionaries were sent to Native Americans, and Brigham Young’s approach in the West, as stated by Leonard Arrington, “was to be friendly, promote peace, trade fairly, avoid extreme reactions or retaliation, and maintain distance.”[69] This difference in attitude toward Native Americans is illustrated by James Pearce’s comments at the first Pioneer Reunion in Phoenix in 1921, as reported in the account for his wife, Mary Jane.[70] The two biographies that show the most interaction with Apaches were those of Mary Ann Smith McNeil and Sarah McNeil Mills, wife and daughter, respectively, of John C. McNeil who moved to Forestdale in 1880 but settled permanently in Show Low.[71] A similarly long discussion of Native Americans is in the sketch for Marium Dalton Hancock, who mostly lived in Taylor and Pinedale.[72] At St. David, Sarah Gardner Curtis’s daughter Clara would play the piano while Apaches sat on the floor and listened.[73] Alchesay and some of his men came to Snowflake to attend the 1892 funeral of Charles Love Flake.[74] Finally, Latter-day Saint services were held at the Phoenix Indian School in the 1920s where RFC was a Sunday School teacher, and several of the women in PWA women served missions to Native Americans in both Utah and Arizona.[75] All of these activities show much more diversity in Native American/

Conclusions

Most of the biographies included in this book are for Latter-day Saint women who came to Arizona from Utah. Exceptions include Mormon women who came directly from other states, women who were born in Arizona, and women not associated with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. There are many other important or deserving women, but only seven sketches were added—all were sketches that RFC had submitted to the FWP.[76] It is possible that some of these sketches were omitted intentionally (e.g., Catherine Dorcas Overton Emmett who only lived at Fredonia), but it is more likely that the exclusions were accidental.

The compilation of 200 sketches representing every area of Mormon settlement in Arizona is a remarkable feat, especially considering the era in which RFC was collecting them, but greater resources are available today. With library collections, demographic databases, and other records made available through the internet, a fuller picture of Arizona pioneers can be painted for this new edition. Hopefully it meets with RFC’s approval.

The Federal Writers' Project

Pioneer Women of Arizona, as published in 1969, consists of two types of sketches—those originally submitted to the Federal Writers’ Project from 1936 to 1938 and those written or collected after the New Deal program was over. Each of these groups contains at least three different types of sketches: sketches collected by RFC (an autobiography, information from a funeral, or material written by a descendant or friend), sketches written by RFC from personal knowledge (such as for her mother or sister), and sketches written by RFC from an interview. The earliest sketch in PWA may be for Cyrena Dustin Merrill, who wrote her autobiography in 1898; one of the later sketches was written about 1957 for Mary Jane McRae McGuire by her two daughters. Knowing the authorship of a sketch, the date it was written, and the audience is vital to understanding the events reported or omitted and the language, including tense.

Franklin D. Roosevelt's Federal Writers' Project in Arizona. Photo courtesy of Arizona State Libraries, Archives and Public Records.

Franklin D. Roosevelt's Federal Writers' Project in Arizona. Photo courtesy of Arizona State Libraries, Archives and Public Records.

In Utah, Juanita Brooks was instrumental in arranging Federal Relief Act monies for widows and unemployed women in Utah by providing them with FWP work. At a 1968 Utah State Historical Society annual meeting, she reminisced about the project saying, “Women who could type or who had daughters who could were set at copying diaries.” Although much of Brooks’s time was spent with the preservation of historical documents (making copies of diaries and journals), she also noted that other women “were sent out to take interviews with the older people of the areas.” Brooks said, “They were instructed to get the important dates of birth, travels, marriage, positions held, and so on, and to fill in with details of home management on the frontier, social activities [and] important events. They were to encourage reminiscences, impressions of visiting church leaders, of local leaders, of the polygamy raids, of anything in which the informant was interested. They would take notes, write them up as best they could, return to visit the person and read what they had written, supplement or change the story as needed, and finally bring it to us to be typed in a preliminary form before we made the final copy with carbons.”[77]

Clayton interviewed some women just as Brooks described, but she also submitted collected sketches, some of which were probably written earlier for the DUP. Of the seventy-nine women’s sketches that RFC submitted to the Federal Writers’ Project, thirty-seven (47 percent) were for women deceased before the project started and therefore these sketches could not have been based on interviews. Five of the collected sketches were written by the woman herself, another ten were written by a daughter, and several were a combination of both. Also, Clayton wrote some sketches from personal knowledge (e.g., for her mother). Not understanding the difference between sketches based on interviews and sketches simply collected has resulted in some misinterpretation. One example is Barbara Marriott, who assumed that all accounts had at least the basis of an interview and titled her book, In Our Own Words.[78]

The FWP sketches that are definitely based on interviews are those for non-LDS women, in contrast to the many collected sketches for Mormon women.[79] Without access to a diary that RFC presumably kept during the time she submitted FWP sketches, it is difficult to know how intimately acquainted she was with each of these women, and there is little internal evidence that answers this question. RFC could have been assigned by Ross Santee, supervisor of the Arizona Federal Writers’ Project, to interview these women, or she could have sought them out on her own as she tried to support her children by writing. These women could have been nodding acquaintances, or they could have been close personal friends.[80]

It is difficult to decide in retrospect what criteria, if any, Clayton used to decide who was a pioneer, both for the FWP submissions and also later biographies. In Utah, a pioneer was defined as someone arriving before 1869 (when the transcontinental railroad crossing Utah was completed), but this criterion was never used in Arizona. By the 1920s, Arizona began thinking about honoring early settlers. The Arizona Republican started collecting pioneer stories and defined a pioneer as “one who has lived continuously or nearly continuously in Arizona for 35 years, or from January 1, 1886.”[81] This date was later changed to 1890. The newspaper sponsored the first of many annual pioneer reunions on April 12–13, 1921. Clayton often attended these, sometimes taking her father, and she may have used the 1890 date for her pioneer women. However, because there are several women who fall outside this criterion, it is likely that she did not use any cutoff date at all.[82]

Clayton’s FWP sketches are markedly different from other sketches in PWA. For example, the FWP sketches have more information about the route and journey into Arizona (undoubtedly because they are closer in time to the event and many times the source is the immigrant herself).

The most important difference, however, may be that often the FWP sketches did not mention polygamy.[83] This omission may have been because the Works Progress Administration was a non-Mormon venue, but the Federal Writers’ Project itself had conflicting purposes of both trying to unite the nation and also showing regional differences. Jerrold Hirsch, who devoted thirty years to study of FWP materials, wrote, “Both American writers of the late nineteenth century and Federal Writers in the 1930s searched for local color. For the most part, the earlier group wrote nostalgically and patronizingly about regional and ethnic differences. . . . For them these different peculiar groups with their strange ways were vanishing remnants of the past. National FWP officials, however, encouraged local workers to seek out diversity with the goal of celebrating it as a sign of American vitality.” But Hirsch noted that neither Frank L. McVey, who, as president of the University of Kentucky, commented on the preparation of state guides from the FWP interviews, nor Harry Hopkins, a WPA federal relief administrator, “explained why American unity would emerge from a knowledge of diversity.” Hirsch summarized this problem by saying, “To the extent that national FWP officials used a romantic nationalist and pluralist approach to try to unite Americans while ignoring conflicts that divided them, they created a mythical view of the nation.”[84]

Certainly the practice of polygamy could be considered a dividing issue in US history. Likewise, the use of FWP slave histories languished because historians debated their usefulness. In 1974, C. Vann Woodward wrote, in a review article about slave sources, “It should be clear that these interviews with ex-slaves will have to be used with caution and discrimination. The historian who does use them should be posted not only on the period with which they deal, but also familiar with the period in which they were taken down . . . he should bring to bear all the skepticism his trade has taught him about the use of historical sources. The necessary precautions, however, are no more elaborate or burdensome than those required by many other types of sources he is accustomed to use.”[85] Nearly twenty years later, historian Robyn Preston wrote about the slave narratives in Oklahoma and concluded that “by paying close attention to these details, readers can sift through the various layers of the narratives in order to come to a better understanding of these remarkable stories.”[86]

One product that came out of the Federal Writers' Project was a guide book for each state; Arizona's was not published until 1940. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

One product that came out of the Federal Writers' Project was a guide book for each state; Arizona's was not published until 1940. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

These cautions apply equally well to Mormon FWP histories from Utah and Arizona. When Clayton’s FWP sketches that were moved directly into PWA without change are read by themselves, it becomes easy to make unwarranted conclusions. For example, it seems likely that when James Phillips wrote about Emma Hansen’s tears upon leaving Utah, he did not understand that Emma was a second wife and that the trip to Arizona included her husband Joseph, his first wife Sophia, and their daughter Mary.[87] When Jerrold Hirsch analyzed many of the FWP slave histories from the southern states, he discussed biases, untrained interviewers, lack of tape recordings, and even outright fabrication.[88] But he concluded that the “alleged weaknesses of the FWP interview materials are not an insurmountable barrier. Historians finally are working at separating the wheat from the chaff.”[89] This caution must be applied to the FWP sketches found in PWA and was used in assessing and supplementing RFC’s accounts.

One of the steps Juanita Brooks mentioned for the Utah FWP sketches was a return to the woman interviewed so she could review the written material. However, RFC may have returned only when the subject was close at hand. Not returning to interviewees when inconvenient distances were involved (e.g., even if the distance was only from Snowflake to Joseph City, as for Emma Swenson Hansen) may have been the source of some errors. These can be errors of omission (e.g., no mention of polygamy), typographical errors (e.g., Silver Roof versus Silver Reef mine), or simply an incorrect calculation or inference (e.g., the number of children for Emma Hansen).

Regardless of whether or not the lack of information about polygamy was overt, Clayton told Sue Abbey in 1973 that the sketches for pioneer men did not emphasize religion. “I just can’t die and let those wonderful stories go by,” she said. “So that’s what I’m getting [together]. I say it isn’t church wise. I’m not stressing the fact that I’m a Mormon or that any of these people went on missions for the Mormon Church.”[90] Nevertheless, these sketches do contain a wealth of information on Mormons in general and Mormons in Arizona specifically.

Ultimately, however, the following poem that Clayton wrote titled “My Friends” may explain her eclectic selection of histories both for the FWP and PWA:

My friends are a varied group of folk

That I choose in a novel way.

It matters not the shade of skin,

Whether eyes are black or gray

It matters not whether rich or poor;

Whether old, middle aged or young;

It matters not their race or creed,

Or whether they speak my tongue.

It only matters if their lives

Encompass all that is fine,

It only matters if their hearts

Speak the same language as mine.[91]

Migration and Settlement

The history of Mormonism has always been associated with people seeking a church that reflected the primitive church of the New Testament. With Joseph Smith’s first vision at Palmyra, New York, in 1820, the subsequent printing of the Book of Mormon in 1829, and the establishment of a formal church at Fayette, New York, in 1830, many felt they had found what they were seeking. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints grew one convert at a time, but not without conflict. Mormons, as a group and singly, moved from New York and Pennsylvania, to Kirtland, Ohio, to western Missouri, and finally to Nauvoo, Illinois, in 1839. The period at Nauvoo (1839–46) began as a time of peace and prosperity, but unfortunately it was all too brief. Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum were killed at Carthage, Illinois, on June 27, 1844, and Latter-day Saints knew that they would be moving yet again.

Under the leadership of Brigham Young, this became the great exodus west. The first wagons left Nauvoo in February 1846, and the last of the poor fled Nauvoo in September of that year. With the departure of the Mormon Battalion (500 volunteer soldiers enlisting in the US army) from Iowa during the summer of 1846, Young decided it would be necessary to spend the first winter on the Missouri River (Council Bluffs, Iowa and Winter Quarters, Nebraska). Mormon pioneers began their journey to Utah the next spring. The classic description of migration along the Platte River is The Great Platte River Road by Merrill J. Mattes. Although his treatment of the Mormon migration is superficial, he discusses the trail from five outfitting locations on the Missouri River to Fort Kearny and calls this route “by all standards the most important ‘way west.’”[92] Significant dates along the Mormon Trail would be 1847 (the Pioneer Company and initial groups of settlers entering the Salt Lake Valley), 1852 (all Mormons living in Iowa being called to Utah), 1856 (the handcart companies), 1860−61 (the down-and-back wagon companies), and 1869 (completion of the transcontinental railroad in Utah).[93]

The events these women report prior to coming to Arizona concentrate mostly on the Mormon Trail experience and settlement in the West. The sketches in PWA have limited information about Nauvoo and Kirtland. In contrast, nearly every convert tells her conversion story and the story of crossing the ocean and/

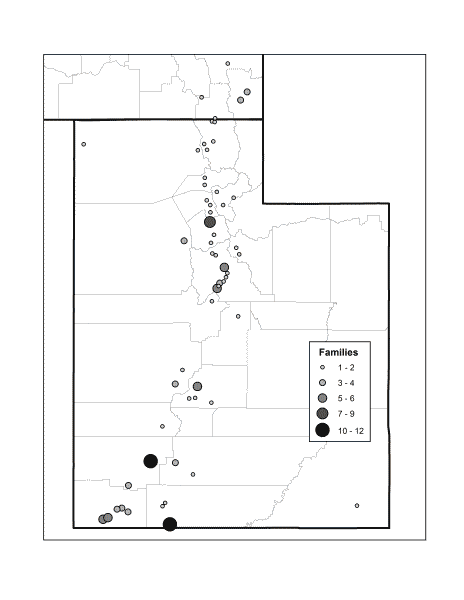

Towns of origin for Mormon emigrants coming to Arizona from Utah and southern Idaho as found in PWA. A family is defined as a married woman and any children, or a family may be two or more siblings. Polygamous wives are counted as one family unless wives came to Arizona in different years. Not all sketches reported previous residence, so the data include 140 families and 174 individuals. An unidentified area (e.g., Sevier River) was included with the county seat (e.g., Richfield). Although not apparent on this map, the large number of families from Parowan and Kanab illustrates two different types of groups: those from Parowan were nearly all associated with the Jesse N. Smith family, while the large number form Kanab were all from separate families. Data are found in Appendix 2. Map prepared by Karina Wilhelm, Map and Geospatial Hub, Arizona State University Library.

Towns of origin for Mormon emigrants coming to Arizona from Utah and southern Idaho as found in PWA. A family is defined as a married woman and any children, or a family may be two or more siblings. Polygamous wives are counted as one family unless wives came to Arizona in different years. Not all sketches reported previous residence, so the data include 140 families and 174 individuals. An unidentified area (e.g., Sevier River) was included with the county seat (e.g., Richfield). Although not apparent on this map, the large number of families from Parowan and Kanab illustrates two different types of groups: those from Parowan were nearly all associated with the Jesse N. Smith family, while the large number form Kanab were all from separate families. Data are found in Appendix 2. Map prepared by Karina Wilhelm, Map and Geospatial Hub, Arizona State University Library.

Immigrants to Arizona came from towns in every part of Utah. However, the most important emigrant town was not located in Utah but was San Bernardino, California. Established in 1851, San Bernardino was attractive to many southern converts; E. Leo Lyman estimated that half of the settlers coming with Charles Rich and Amasa Lyman to settle this area were from the South.[95] Within a few short years, San Bernardino became one of the largest towns in California. By 1857, however, these colonists were called back to Utah by Brigham Young and many settled in towns from Santa Clara, Utah, to Paris, Idaho. Lyman listed the following former San Bernardino families as coming to Arizona: Boyle, Crismon, Crosby, Flake, Hakes, Holladay, Hunt, Kartchner, Matthews, Nelson, Pratt, Reed, Sirrine, Smithson, Tanner, Tenney, and Turley.[96] Other families that could be added to the list are Burk, Daley, Driggs, Grover, Lake, Morse, Parkinson, and Phelps. These families settled along the Little Colorado River, in the Gila Valley, and in the Mesa area.[97]

The obvious physical barrier for members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints leaving Utah to settle in Arizona was the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River.[98] Mormon explorer and missionary Jacob Hamblin first crossed the Colorado River in 1858 at the Crossing of the Fathers located near the Utah-Arizona border, now buried beneath the waters of Lake Powell. Then, in 1862, he crossed below the Grand Canyon (at Pierce’s Ferry or maybe Stone’s Ferry), traveled past the San Francisco Peaks to the Little Colorado River, and returned to St. George via the Crossing of the Fathers, completely circling the Grand Canyon. As Arizona historian Frank Lockwood noted, between 1871 and 1873, Hamblin “marked out a hard but practicable route from Utah into the Painted Desert by way of Lee’s Ferry, Tuba City, Grand Falls, and up the Little Colorado to Sunset Crossing (near Winslow).”[99]

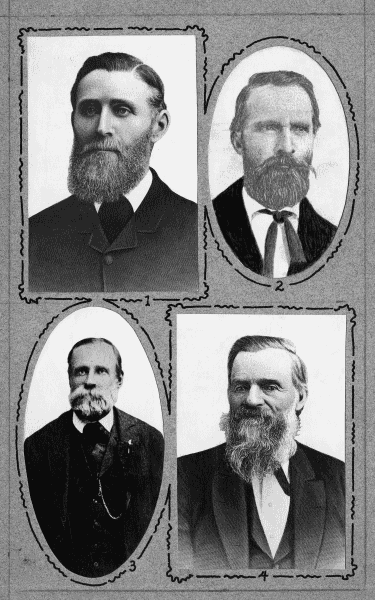

McClintock's 1921 collage of Colorado River ferrymen: (1) John Blythe who in 1873 built a 20-by-40-foot barge that could hold two teams and wagons. (2) Harrison Pearce who established a ferry at Grand Wash 280 miles below Lee's Ferry. (3) Daniel Bonelli who established a ferry at the Virgin River crossing (sometimes called Stone's or Scanlon's Ferry). (4) Anson Call who established a ferry and the twon of Callsville at the mouth of the Las Vegas Wash hoping steamboats could be used for supplies and emigrants to Utah. Photo courtesy of Church History Library.

McClintock's 1921 collage of Colorado River ferrymen: (1) John Blythe who in 1873 built a 20-by-40-foot barge that could hold two teams and wagons. (2) Harrison Pearce who established a ferry at Grand Wash 280 miles below Lee's Ferry. (3) Daniel Bonelli who established a ferry at the Virgin River crossing (sometimes called Stone's or Scanlon's Ferry). (4) Anson Call who established a ferry and the twon of Callsville at the mouth of the Las Vegas Wash hoping steamboats could be used for supplies and emigrants to Utah. Photo courtesy of Church History Library.

Eventually, ferries were established both above the Grand Canyon and below; Arizona’s historian James McClintock collected photographs of some of the founders. Lee’s Ferry (often called Johnson’s Ferry by the immigrants) was at the mouth of the Paria River, immediately above the Colorado River’s plunge into Marble Canyon, which is the beginning of the gorge of the Grand Canyon.[100] All of the lower ferries were located at the Big Bend of the Colorado River (i.e., near where it is joined by the Virgin River and where it turns from west to south). Pierce’s Ferry was first, 280 river miles downstream from Lee’s Ferry, followed by Bonelli’s Ferry (sometimes called Stone’s or Scanlon’s Ferry) and Callville or Call’s Landing.[101] These ferries are now under the waters of Lake Mead.[102] Mormon emigrants used both the lower ferries and Lee’s Ferry until the completion of Navajo Bridge over Marble Canyon in 1929.

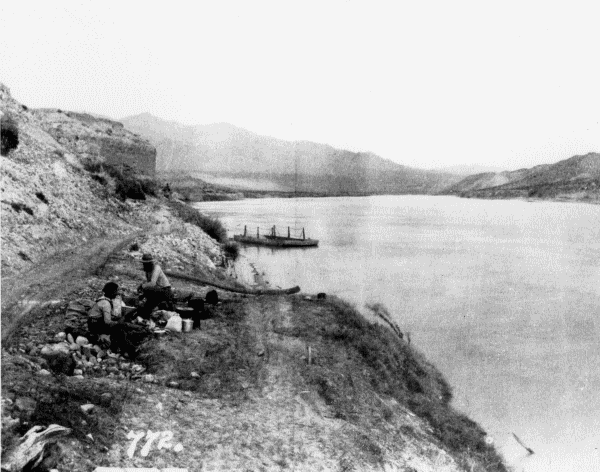

The setting for Lee's Ferry at the mouth of the Paria River where it meets the Colorado River. Photo courtesy of Oracle Historical Society.

The setting for Lee's Ferry at the mouth of the Paria River where it meets the Colorado River. Photo courtesy of Oracle Historical Society.

The ferry and ferrymen at Lee's Ferry, c. 1925; Lynn Lyman, photographer. Photo courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

The ferry and ferrymen at Lee's Ferry, c. 1925; Lynn Lyman, photographer. Photo courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

Bonelli's Ferry, looking upstream, 1890, Stanton Survey photograph. Photo courtesy of utah State Historical Society.

Bonelli's Ferry, looking upstream, 1890, Stanton Survey photograph. Photo courtesy of utah State Historical Society.

A Keystone View Company stereoscope image looking westward, with the Colorado River flowing downstream through Marble Canyon, titled, "New Bridge Across Colorado River near Lee's Ferry, Ariz." Navajo Bridge, located four miles below Lee's Ferry, was completed in 1929; it was 834 feet long and 467 feet above the river. Photo courtesy of the Ellis Collection.

A Keystone View Company stereoscope image looking westward, with the Colorado River flowing downstream through Marble Canyon, titled, "New Bridge Across Colorado River near Lee's Ferry, Ariz." Navajo Bridge, located four miles below Lee's Ferry, was completed in 1929; it was 834 feet long and 467 feet above the river. Photo courtesy of the Ellis Collection.

Before the death of Brigham Young in 1877, individuals and families received calls, generally at conferences, to settle new areas.[103] The settlement of southern Nevada (at one time Pahute County, Arizona) began with thirty missionaries called in April 1855 to an Indian mission at a spring and meadow eventually known as Las Vegas. Additional missionaries were called to mine lead nearby, but all were called back to Utah in 1857 as Johnston’s army marched toward Utah.[104] The next calls to this area were in November 1864 when 183 families were called to the Muddy Mission (Moapa Valley). Settlers gradually came and built the towns of Overton, St. Thomas, St. Joseph, and Mill Point. However, with the establishment of valuable mines in this section of Nevada and officials wanting to ensure the mines were not in Utah, Congress moved the Nevada-Utah border one degree east in 1866 and then in 1867 ceded to Nevada all Arizona territory west of the Colorado River.[105] This resulted in border disputes; Nevada officials expected taxes which had previously been paid to Utah and Arizona. Mormon settlers were also concerned about Nevada’s higher taxes which had to be paid in gold or hard currency. Finally, Brigham Young visited the area in March 1870 and by December decided to release all the pioneers to settle other areas. Some of these Nevada pioneers eventually settled in Arizona.[106]

Following Brigham Young’s death in 1877, not all pioneers came to Arizona with specific calls.[107] Ellen Larson Smith noted that “word came through the ward Bishop that President Young was planning to colonize Arizona and he wanted faithful, industrious thrifty men with families to go as soon as they could arrange their affairs. So [Mons] Larson and August Tietjen were the families called from Santaquin.”[108] On the way to Arizona, the Larson family heard about Snowflake and decided to settle there. Seth Tanner, however, was called in 1876 to “go to the place on this river [the Little Colorado] where emigrants first contacted it and there to build a granary where travelers from Arizona, bound for Utah could store their grain and other feed for their horses on the return trip.” The family lived at Moenkopi and Moabi.[109] Elizabeth Curtis reported that Erastus Snow told the people, “Brothers and Sisters, go somewhere but settle among the Saints wherever you do go. I think the Gila Valley is a very good place, but I do not advise any particular place, that is left to you.”[110] They settled in the Gila Valley.

Also, some women chose to come to Arizona to be with family members. Cedenia Willis wrote, “I pleaded with my husband to go that I might be with my Mother. What loving daughter does not know my feelings?”[111] Others came seeking better health. Elizabeth Adelaide Allen’s husband suffered with rheumatism and “persuaded his good wife that it would be to their advantage to go to Arizona, the ‘Land of Sunshine’. He had heard of the virtues of that sunny land from his brother, Elijah who had traveled through southern Arizona with the Mormon Battalion.” So, in October 1882, the couple left their home in Cove, Utah, with “two wagons, four horses to each, a light hack with one team and some nice fat horses.” Elizabeth drove the hack to Mesa, and “during these six weeks of traveling, her knitting needles were ever busy as she permitted her horses to follow along behind the other wagons.”[112]

As George Tanner, a son of one of these pioneers, wrote, “The migration of the Mormons into the bleak landscape of northern Arizona cannot be easily explained.”[113] Reports from the early exploratory parties of Lorenzo Roundy and Horton Haight in 1873 ranged from not optimistic to completely gloomy.[114] Jacob Hamblin and Daniel W. Jones were critical and thought these parties lacked faith and stamina.[115] Jacob Hamblin wrote, “In the winter of 1873−74 I was sent to look out a route for a wagon-road from Lee’s Ferry to the San Francisco forest or the head waters of the Little Colorado.” In the spring of 1874, he accompanied “about one hundred wagons” as far as Moenkopi. According to Hamblin, “For a considerable distance beyond Moancoppy the country is barren and uninviting. After they left that place the first company became discouraged and demoralized, and returned. . . . The companies that followed . . . partook of the same demoralizing spirit. They could not be prevailed upon to believe that there was a good country with land, timber and water a little beyond where the first company turned back. . . . When this company was sent into Arizona it was the opportune time for the Saints to occupy the country. Soon after, the best locations in the country were taken up by others and our people have since been compelled to pay out many thousands of dollars to obtain suitable places for their homes.”[116]

Then, in 1875, Brigham Young sent James S. Brown, with fourteen seasoned frontiersmen, to reassess the Little Colorado River area. Tanner thought that Young may not have even waited for their report before he called strong leaders to settle four places: Lot Smith at Sunset, William C. Allen at St. Joseph, Jesse O. Ballenger at Brigham City, and George Lake at Obed.[117] But in defense of Roundy and Haight, Tanner noted that three of these settlements “passed out of existence within a decade.”[118]

Arizona immigrants used two migration corridors in central and southern Utah—the first through Panguitch to Kanab and the second through Beaver and Cedar City to St. George. Many emigrants came from the towns around St. George (Washington, Virgin City, and Toquerville) where some of the men had been working on the St. George Temple. Completed in 1877, its construction had served as a quasi-public works project, and with no railroad to market their crops, many men who were looking for other areas to farm considered Arizona. Also, several groups had previously lived at Kanab, and this became an important stopping place for travelers. Groups from northern Utah often used the eastern route and did not go to St. George unless they wanted to attend the temple before proceeding on to Arizona.

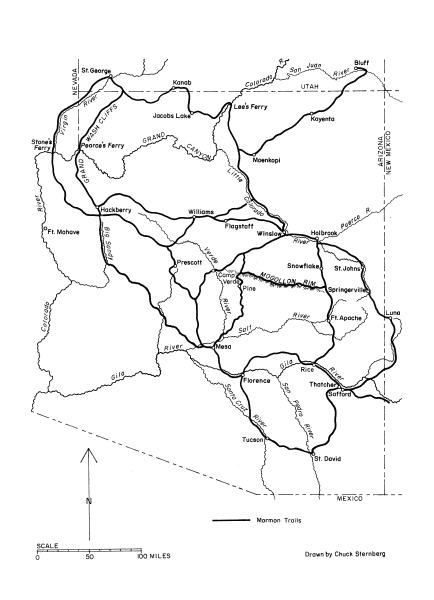

Latter-day Saints migration routes into Arizona as found in PWA. the route through Hackberry became known as the Western Route, and the route through Lee's Ferry was called the Old Mormon Road (later Honeymoon Trail). Map prepared by Chuck Sternberg.

Latter-day Saints migration routes into Arizona as found in PWA. the route through Hackberry became known as the Western Route, and the route through Lee's Ferry was called the Old Mormon Road (later Honeymoon Trail). Map prepared by Chuck Sternberg.

At St. George, emigrant parties had to choose between two routes into Arizona. The first route meant traveling south from St. George, through the Grand Wash Cliffs area and crossing the Colorado at Pierce’s Ferry or down the Virgin River and crossing at Stone’s Ferry, then proceeding to Hackberry, where the parties had to decide if they were traveling east through Williams and Flagstaff to the Little Colorado River area or turning south and traveling through Prescott to Mesa or St. David. This route was sometimes called the western route.[119] The second route meant traveling east from St. George through southern Utah and the Arizona Strip to Kanab, then southeast across Buckskin Mountain (often plural in pioneer manuscripts) on the Kaibab Plateau to cross the Colorado River at Lee’s Ferry (also called Johnson’s Ferry), then south to the Grand Falls of the Little Colorado River, and then east to Winslow and Holbrook.[120] By 1880, this was labeled on maps as the “Mormon Wagon Road.” Salina Turley, who came with her natal family in 1881, recalled that “the Smithson family started out alone, Arizona bound to find a new home. By this time a fairly good wagon road had been made by the hundreds of emigrants who had gone on before and the trip was a short one,” meaning four weeks.[121] It was not until 1934 that Will C. Barnes in an Arizona Highways article called this route the Honeymoon Trail, but many using this route were not, in fact, betrothed or honeymooners.[122]

Reaching Holbrook, an immigrant party again had to choose whether to travel south to Snowflake, Taylor, Show Low, and Forestdale; southeast to St. Johns and the Springerville/

Lee’s Ferry was not initially assumed to be the best route for Mormon immigrants coming into Arizona, even if the immigrant destination was the Little Colorado River. Deciding factors were distance, water, and cattle. The direct route was generally preferred, and the route across Buckskin Mountain was gradually shortened.[125] The amount of water in both the Colorado River and along the route usually made a fall trip preferable. Spring runoff often meant that the river was running so high that a crossing at Lee’s Ferry was unwise. Seeps or springs dotted the route, but probably every immigrant company carried barrels of water that could be used when the company made dry camp. And finally, many immigrant parties trailed a large number of loose cattle and horses.[126] Will C. Barnes, in writing about the Mormon newcomers, wrote, “The great number of these people were farmers who brought with them not only farming tools but live stock as well. Their cattle were unusually well-bred. They were nearly all milk stock.” He noted that the original cattle in the Southwest were “the longhorn type—huge, rawboned, high-hipped animals,” but of the cattle brought by the Mormons, nearly 75 percent “were Devons, famous always for their milking qualities; the rest were Shorthorns, or Durhams.”[127]

Using these three factors, it becomes easier to understand the choice of a route for Mormon travel to Arizona. Immigrants to the Little Colorado and Gila Rivers used Lee’s Ferry almost exclusively. It was direct and afforded sufficient water and feed for animals—if traversed during the fall. Immigrants to Mesa and St. David faced a harder choice—the western route through Hackberry was shorter, but it had fewer dependable water sources. If the pioneers were traveling light, using a hack and unencumbered by loose cattle and horses, the Lower Colorado River ferries made the trip from St. George significantly shorter. However, for emigrant parties trailing cattle, the presence of better water and grass made the Mormon Wagon Road (Lee’s Ferry route) the best choice. The first two groups of Mormon settlers in the Salt River Valley arrived in 1877 and were usually referred to as the Jones (or Lehi) Company and the Mesa Company; both were large parties. The Lehi Company, with no extra cattle, traveled from Utah via the Stone’s Ferry-Hackberry route, while the Mesa Company used the Lee’s Ferry to Sunset (now Winslow) to Camp Verde route.[128]

After suffering through the extreme heat of a summer in the Salt River Valley, the four Merrill families and the families of George Steele, Joseph McRae, and Austin O. Williams, who had all come to Arizona with the Lehi Company, moved farther south to the San Pedro River. Philemon C. Merrill first marched through southern Arizona with the Mormon Battalion in December 1846 and undoubtedly remembered the area along the San Pedro as having better grass for his cattle. This became the town of St. David and was eventually strengthened with the arrival of additional families from Utah—some of whom used Lee’s Ferry while others used Pierce’s Ferry. There was also a great deal of interaction between settlers in the Gila Valley and St. David. Hyrum Weech said, “People would come in here [to the Gila Valley] from Utah, look over the valley and usually locate somewhere. Some, however, went on from here to the San Pedro. Others came from the San Pedro and located here.” Weech also recalled: “I was on the San Pedro in 1881. They had just started getting land under cultivation. Jonathan Hoopes was on the San Pedro then and Sam Curtis, [Heber] Reed, Woorsley and others. All of them went over there from here [the Gila Valley], one reason, because there was a lot of freighting there,” particularly from the railroad to Tombstone, Arizona, and Nacozari, Mexico.[129]

The final nineteenth-century enclave of Latter-day Saints was in the Tonto Basin, particularly the towns of Pine and Strawberry. Early settlers included the families of Ruth and Alfred Randall, Hannah and John Sanders, Elese and William Hunt, and Rosetta and Alma Hunt. The Hunt brothers had spent one winter in Snowflake and then moved on to the Tonto Basin. Settlers here used both Lee’s and Pierce’s Ferries, sometimes depending upon if they wanted to attend the St. George Temple. Elese Hunt illustrated the pros and cons of each route when she said, “In 1883 my husband and our family went back to Utah to visit our folks. We went by Pearce’s Ferry, thinking it would be better but there wasn’t much choice, only each one was worse than the other. Feed and water for the animals was scarce.”[130] Later, additional settlers were called to this area including Lyman Utley Leavitt in 1899.[131]

Not just the Mormon settlements in Arizona, but the entire territory was settled late compared to other western states. With the economies of many of these states based on mining, exploitation of native ores in Arizona lagged far behind other states for at least three reasons. The first reason was Native American depredations. The state of Georgia simply moved Native Americans west, California killed most, and Montana, Alaska, and South Dakota experienced only a few brief skirmishes. To the Apaches, however, raiding was a way of life, and miners often justifiably feared for their lives. The second problem was transportation; railroads came late to Arizona because of the arid desert and harsh topography. Third, ores in Arizona were extremely complex, necessitating industrial expertise and machinery to extract it. As Rossiter Raymond wrote in 1875, “At present only such gold and silver lodes as would elsewhere be considered surprisingly rich can be worked to advantage, and scores of lodes that would pay handsomely in California or Colorado are utterly neglected, while the great copper interests of the Territory (for copper is nowhere more abundant or of greater purity) are for all practical purposes without value.”[132]

Consequently, the settlement of Arizona and the advent of railroads happened about the same time. The Southern Pacific Railroad was completed east to El Paso in 1881, and the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad (later Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe) was officially open to transcontinental passenger service on October 21, 1883.[133] These two railroads opened the territory to the outside world. Arizona historian Odie B. Faulk wrote, “Perhaps the greatest event in Arizona in the nineteenth century was the arrival of the railroads,” and then he concluded, “Eventually almost every major town in the territory had rail service, just as did every major mine.”[134] Several Mormon families, or parts of families, traveled by train to Arizona. When Elizabeth Layton’s husband, Christopher, was called in 1883 to preside over the St. Joseph Stake, which at that time included St. David and the Gila Valley settlements, he rented two entire railroad cars in Salt Lake City and “loaded them with horses, mules, furniture, farm implements, seeds, alfalfa, oats, wheat and flour enough to last a year.” He assigned some of his sons to take care of the animals in the freight cars while the rest of the family traveled by a faster train, arriving in St. David two days ahead of their household goods.[135] In 1884, Kate and William Burton traveled to Maricopa Station by train (through Downey, California, so she could visit relatives).[136] And in 1887, Happylona Hunt came to Snowflake presumably through Colorado, because her lost belongings were found in La Junta six months later.[137]

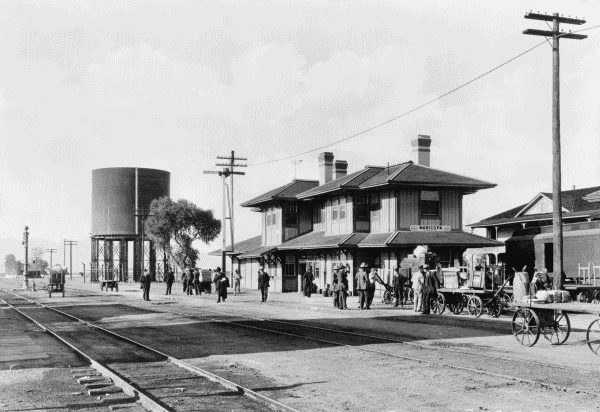

Maricopa Train Station, Southern Pacific Railway. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Maricopa Train Station, Southern Pacific Railway. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

It must be noted that some of the Mormon women whose biographies are included in PWA, and all of the non-LDS women, traveled directly to Arizona from areas other than Utah—including Mexico, Alabama, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Illinois, Missouri, Nevada, and Texas. Some of the Mormons included the ill-fated Arkansas Company (composed of converts from Arkansas, Georgia, and Alabama) that came to the Little Colorado River area during the winter of 1877−78. These families were poor when they started and destitute when they arrived. They were distributed throughout the various camps because no settlement had food enough to share with the full company. Most of these people eventually moved to the Gila Valley.[138] Other emigrants who came directly to Arizona include Ellen Greer (who arrived about 1878 from Texas) and Louise Cross (who came in 1885 from Illinois).[139] Both of these women had been part of the original migration to Utah, but they later traveled east and lived in Texas and the Midwest. Also, some women decided to come directly to Arizona when they converted to the Mormon faith. Susan Youngblood and Carrie Lindsey’s parents were converts of Charles L. Flake when he was serving as a missionary in Mississippi.[140]

The sketches in PWA detail a considerable amount of movement after 1880, both within Arizona and to points outside the territory. The earliest moves to Mexico were generally associated with imminent prosecution over the practice of polygamy, but other sketches express the desire to be with family members in Mexico or to look for better economic opportunities.[141] The biography for Mary Ann “Lannie” Mitchell Smith describes the route from Snowflake into Mexico: “They left Feb. 10, 1885, Lannie’s birthday, going by way of St. Johns, Nutrioso [Arizona], and Luna Valley [New Mexico]. The company camped near La Ascencíon [Mexico] but many of them pushed on to a site on the Piedras Verdes River above Casas Grandes [Chihuahua].”[142] Joseph Fish was part of the group that traveled through western New Mexico to Chihuahua, but he returned to Snowflake through the Gila Valley and Fort Apache in February 1886.[143] Shortly thereafter, the railroad became an important mode of transportation to Mexico. When Frederick G. Williams II moved his families from Ogden, Utah, to Chihuahua in 1890, they rode the train to Deming, New Mexico, and then traveled to Colonia Díaz by wagon.[144] Although Joseph Fish was a polygamist, his 1893 move into Mexico seems to be more related to economic security. He records this trip as through Fort Apache, the Gila Valley, Willcox, and Bisbee to Colonia Oaxaca, Sonora, a route which was often used into the Sonoran colonies.[145]

Generally, however, it was a search for economic security that prompted Mormon moves. Many Arizona settlements were on marginal farmland, specifically land tied to less reliable water sources compared to land in Utah. Without the obligation associated with being called to settle an area (or eventually released from their obligations under the communal United Order), the pioneers felt free to relocate. Sometimes they found a better life and sometimes not. Discouraged by the limited water supply at Snowflake, Ellen and Mons Larson moved to Pima and then to Glenbar, where Mons died in 1890. Their daughter Ellen Smith moved with them to Pima in 1882, returned to Snowflake in 1886, and then moved on to Salt Lake City; by 1937 when RFC wrote her FWP sketch, Ellen was residing in Monticello, Utah.[146] The biographies for Rowena McFate Whipple and Mary Ann Ramsay report several moves around the state related to employment, and both Caroline Kimball and Emma Merrill first lived at St. David and then moved to the Gila Valley.[147] The search for economic security likewise prompted the moves of the Lyman Hancock family. Marium and Lyman Hancock lived in Pinedale and Taylor when they were first married. Then they relocated to Luna and Williams Valley, New Mexico. According to Marium, “We didn’t gain anything by going to New Mexico but another son whom we named Charles Levi, so we returned to Pinedale.” Then later, they moved to Bryce, in Graham County, stayed one year, and came back to Pinedale.[148]

Several twentieth century settlements also need to be mentioned when writing about the Mormon settlement of Arizona. In discussing late Mormon colonization efforts, geographer D. W. Meinig wrote that by 1890, “the Gathering had lost its momentum and the concept of a geographically expanding kingdom was no longer feasible. The days of seizing virgin land were long since past and large blocks of land suitable for group colonization were becoming scarce and expensive.”[149] Meinig then used the 1893 settlement of Latter-day Saints in the Big Horn Basin of Wyoming as an example, stating that this settlement was not Church directed, had no designated leader, and did not secure land and water rights in advance. Others, however, have seen the Big Horn Basin as Church directed, at least by 1900 when Apostle Abraham O. Woodruff organized an immigrant company into this area.[150]

The 1899 settlement of Binghampton, north of Tucson on the Rillito River, may be a better example of a non-Church-directed settlement. This area was principally settled through the efforts of Nephi Bingham and his brothers, Jacob and Daniel. After Binghampton was established, Latter-day Saints from the Gila Valley and St. David felt comfortable moving to Tucson for employment and to attend the university.[151] The Binghampton area also absorbed many refugees from Mexico, beginning with Heber Farr and his relatives in 1909 and continuing with Mormon colonists fleeing revolutionary unrest south of the US-Mexico border in July 1912.[152]