P

Roberta Flake Clayton, Rhoda Perkins Wakefield, Sarah Perkins Duncan, Barbara Ann Phelps Allen, Hazel Pomeroy Millett, Irene Pomeroy Crismon, Sarah Lucretia Phelps Pomeroy, and Elizabeth Isabelle Jacobson Pulsipher, "P," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 515-564.

Alzada Sophia Kartchner Palmer

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP[1]

Maiden Name: Alzada Sophia Kartchner

Birth: January 5, 1858; Mohave Crossing, San Bernardino Co., California

Parents: William Decatur Kartchner[2] and Margaret Jane Casteel[3]

Marriage: Alma Zemira Palmer;[4] May 11, 1874

Children: Wesley (1875),[5] Ida (1878), Alma Jordan (1881), Jesse (1883), John E. (1885), Sally Jane (1887), Arthur (1890), Dora (1893), Rosetta (1896), Lulu (1899)

Death: January 8, 1936; Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Alzada Sophia Kartchner Palmer was born January 5, 1858, at Lower Waters, Mohave Crossing, California, near what is now San Bernardino. She was the daughter of William Decatur Kartchner and Margaret Jane Casteel. They were pioneers in California at this time, and were just preparing to leave for Beaver, Utah, to pioneer the desert lands, when their daughter Alzada was born. The night after she was born, her brother James, who was two years of age, died. The journey then was delayed three or four days to let the mother rest. The father prepared the little boy for burial in an old fashioned metal churn, sealing it tightly.[6] They took him to Parowan, Utah, to bury him.

The Kartchner family moved into Beaver, where they made their home for eight years. Their home was humble but a heaven on earth. They were all musicians; some played violins, Alzada played the accordion, and they all danced and sang, enjoying many jolly times in the way of pleasure, at home. In their work, life was also a joyous thing. Three or four spinning wheels were put in one room where all could work together and enjoy real companionship and a wealth of family love. Alzada wove cloth when she was so small she could hardly reach to put the band on the wheel. They spun their own thread as well as wove the cloth. One year her sister Sarah wove four hundred yards of cloth.

Alma Zemira (A. Z.) and Alzada Sophia Kartchner Palmer. Photo courtesy of Arvin Palmer.

Alma Zemira (A. Z.) and Alzada Sophia Kartchner Palmer. Photo courtesy of Arvin Palmer.

It was here in Beaver that Alzada first went to school. She loved her school work and had much fun working her “sums” as she called it. She had a sweet alto voice, her sister, Marinda, soprano, and they spent many contented hours singing together.

Though very poor, they were quite happy. Their beautiful home life and the sterling character of her father and mother were truly reflected in her life, for no matter where she was she carried peace, strength, and comfort to those about her. In her diary, she mentions the caroling on Christmas morning, how she looked forward to the wonderful Christmas songs and spirit. Well might her life be compared to a beautiful song. Every minute was deeply lived in cheerful sacrifice and loving service to others.

From Beaver, Utah, they moved to what was called “The Muddy.” Here, both men and women worked very hard raising crops and weaving cloth and carpets. It was here they pioneered again, to build homes and make them comfortable. They raised good melons and made molasses. This first year they raised two crops. Always they were happy, making work as well as play a pleasure.

The taxes became so high they decided to move.[7] In 1871 they went to Panguitch where they built a log house of two rooms also a blacksmith shop as her father was a blacksmith. In this home as always they made work a pleasure and were taught by example as well as precept to be good sports and make life pleasant in the face of the difficulties that must of necessity arise when pioneering new countries. In her own words she says, “I was proud of my parents; they were honest and true.”

It was in Panguitch [that] she met Alma Zemira Palmer whom she married on May 11, 1874 in the Endowment House. Of him she writes in her diary, “My husband was an honest, straight-forward, good man and a good provider.” He had saved up a little money, and they were thrilled and happy buying a few necessities to set up housekeeping. In the little two-roomed log house there in Panguitch, they were happy and comfortably located.

Her husband obtained work at Beaver of William J. Flake (his brother-in-law). They moved to Beaver for a time, and it was here, on July 24, 1875, that a son was born to them. They named him Wesley. Soon after the birth of their son, they moved back to Panguitch. They were there about two years when their parents and the young folks too were called to go again and pioneer another desert, this time to Arizona.

In 1877, they came to Arizona. Her husband drove three yoke of oxen and two wagons, walking all the way from Panguitch, Utah, to Arizona. They encountered serious dangers while coming. One was in crossing the Colorado River, another when coming over what they called “Lee’s Backbone.” At one point the wagon was thrown on the two outside wheels almost throwing wagons, oxen, wife and child, and all the rest over the embankment to hundreds of feet below. But with his skillful control of the oxen, they were spared. These were only two of the many experiences.

For a time, they located on the Little Colorado River making farms and building dams. One main dining room and kitchen was built, and all the families ate together. It was here that a baby girl, Ida, was born to them, June 13, 1878.

The floods were so bad that her husband became discouraged. One day, as he was saddling his horse, William J. Flake asked him where he was going. When he told him, Mr. Flake said he wanted to go with him. (It was A. Z. Palmer who accompanied Mr. Flake on this trip and not as implied in this story.)[8] They went east and then south looking for a place where they would like to locate. As they were returning, they passed Stinson’s ranch thirty miles south of the Little Colorado on Silver Creek. Mr. Flake made a trade for the land and several families moved up and began again the work of pioneers, building up the waste places.

The place was named Snowflake. In a short time, the place was laid out in city lots, and they began building on their own lots. They went up in the forest and cut logs to help in the building of their homes.

Alzada Palmer soon had one room to call her home, the first to be built in Snowflake by the pioneers. After living in a wagon box for so long a time, she felt very rich and happy. When her husband had completed the first chimney ever made in the town, Mrs. Lois Hunt came by, swung her sunbonnet round and round in the air several times, and shouted, “Hurrah for Al Palmer.” Of course the floor was a dirt one, but they were truly home builders. Her husband put grass all over the floor and then they put a carpet down, one brought from Utah. It was cozy and lovely, but the deepest, grandest thought of all is that whether it was a wagon box or log house or the nice home they built in later life, it was indeed “Home Sweet Home,” for they made it so with the beautiful spirit of love and self-sacrifice.

They had brought enough flour to last a year but by this time it was gone. Her husband went over in the Nutrioso country and bargained for some good wheat. When they went for the wheat it was sacked and ready. They brought it home but when it was ground into flour they found it was not the nice wheat they had first bargained for but a dark, sticky wheat. She did not complain but, as always, found a way by learning how to mix it to make it eatable. They were even grateful for it, although disappointed in the bargain.

Six more children were born to them while they lived in Snowflake: Alma Jordan, Jesse, John E., Sally Jane, Arthur, and Dora. They moved to Taylor, three miles south of Snowflake, in 1895. Here Rosetta and Lulu were born. They lived in a four-roomed lumber house in Taylor for many years, [and] had an orchard and lots of fruit in the years when the frost wouldn’t kill the blossoms. Everyone for miles around enjoyed the fullness of this. In about 1910, they built an eight-room brick house much nicer than they had ever enjoyed before. This had been a goal long desired.

Mrs. Palmer, though timid, never making any public show, was in times of serious trouble or danger calm and handled the situation with deliberation and accuracy. After she was sixty years of age, she learned to play the piano well enough for her children to sing as she played. She received her lessons through the mail and worked them out herself. She lived fully, deeply, nobly, and truly, making her home a place of comfort and rest to all who entered it.

In about 1900, she was stricken with asthma and was almost entirely bedfast for fifteen years. She endured through this siege, having dropsy part of the time also. Never once did that sweet spirit of peace leave her despite the fact that her body suffered and she was powerless physically to help. She was a great source of strength to the family; she would laugh and join in the children’s jokes and sympathize with them in their troubles. She gave advice to them; she was a most helpful and loving wife. Her discipline was perfect for she did it with love, and in return the children obeyed her because of love and not of fear. She always had time to play the game such as crokinole and checkers with the children.[9] She was always at peace within herself to give the story hour in the evenings. She was truly a peacemaker. Her love reached out to the one in trouble. She could always in some way give relief, and day or night, ill or well, or in sorrow, she met you with a smile and a tender greeting that gave strength and made one forget he was in trouble. Not only her smile and time was given to others, but her last penny, butter, eggs, fruit—anything she had was as freely given.

Christmas was truly a joyous time, for she, with her husband, made it so. His death occurred in 1925, and she was very sad after so many years of close companionship. They had celebrated their Golden Wedding at Taylor a year and a half before. They had built a lovely home in Mesa, and it was here that Mrs. Palmer lived with her daughter Rose Brimhall until her death from pneumonia three days after her 78th birthday, January 8, 1936.

Ellis and Boone:

On December 28, 1936, Alzada Palmer was in an automobile accident with some of her grandchildren and died eleven days later.[10] In Arizona, poetry was common for funerals.[11] When the FWP sketch for Alzada Palmer was placed in PWA, Clayton made almost no changes, except for omitting this last sentence and poem: “A poem written by Vida Brinton at the time of [Alzada’s] death tells beautifully of her character.

“Sister Palmer”

Kind and gracious, sweet and lovely,

Is this sister whom we love.

Who by our Father’s been found worthy

To return to Heaven above.

She was grand to all who knew her,

Pleasant, sweet and gentle too,

An Inspiration to the young folks

To carry on and still be true.

What a glorious, grand reunion

When she meets her husband there.

With her children and her parents

All their glories she will share.

Would we ask if we could do it

To have her back on earth again?

No—’twould be a selfish motive

To bring her back to grief and pain.

Well she lived her life as mortal,

With husband, children, parents dear,

Now she’s gone to life eternal

To join her loved ones over there.

Now she’s gone each day you’ll miss her,

Miss her sweet and cheery smile.

Miss her in your work and pleasure;

Often it may seem a trial.

But through death our Father blesses

Those who seek in earnest prayer,

May his peace and comfort guide you

For his love you surely share.

Mary Jane Meeks Pearce

Roberta Flake Clayton, Interview

Maiden Name: Mary Jane Meeks

Birth: December 2, 1851; Kanesville, Pottawattamie Co., Iowa

Parents: William Meeks and Mary Elizabeth Rhodes

Marriage: James Pearce; March 6, 1867

Children: Lola May (1868), James William (1871), Joseph Harrison (1873), Mary Jane (1876), Elizabeth (1878), Henrietta (1881), John Henry (1884), Jesse Harvey (1886), Sylvia Amelia (1889), David Earl (1891), Perry Meeks (1895)

Death: October 13, 1941; Taylor, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Taylor, Navajo Co., Arizona

Born of pioneer parents and destined to live more than eighty years of pioneer life in building up the country her fathers had adopted before her birth, Mary Jane Pearce in fulfillment of her parents’ work, shows a record well written with adventure, danger, bravery, hardships, and the many occurrences which accompanied travel in the early days.

James and Mary Jane Meeks Pearce with children; front row, left to right: James (father), Jesse Harvey, Mary Jane (mother), Sylvia Amelia, John Henry; standing behind parents: Mary Jane, Joseph Harrison, Henrietta, Elizabeth, James William, Lola May; c. 1889. Photo courtesy of Shirley Cole.

James and Mary Jane Meeks Pearce with children; front row, left to right: James (father), Jesse Harvey, Mary Jane (mother), Sylvia Amelia, John Henry; standing behind parents: Mary Jane, Joseph Harrison, Henrietta, Elizabeth, James William, Lola May; c. 1889. Photo courtesy of Shirley Cole.

Mary Jane Pearce, weighing less than 100 pounds today at the age of eighty years, easily relates tales of hardships met and conquered by first her parents and brothers and sisters and later herself, her husband, and children.

She boasts a grandfather who was killed in the war while in action on the frontier of Indiana in 1811. Her father was William Meeks and her mother, Elizabeth Rhodes, and to them was born Mary Jane at Pottawattamie County, Iowa, December 2, 1851. Her parents and other members of the family came to Utah in 1852 before the child was a year old.[12]

In 1862, after already having made a home for themselves, the family answered a call to southern Utah to help settle St. George and work on the Latter-day Saint temple there.[13]

The childhood days of the young girl were spent in weaving cloth and later making their garments from the hand-woven materials and helping her mother with household affairs. At thirteen years of age, she was an expert weaver, and by the time she reached sixteen years of age and was married, all her bed ticking, pillowslips, and sheets were carded, spun, and woven by her own hands. The art of dyeing had been learned by the young girl from her mother who utilized native herbs as did the Indians, and Mary Jane boasted gaily striped and plaid garments. So expert was her weaving judged [that] she was requested to do the weaving for wives of high officials in the Latter-day Saint Church.

In 1866, a factory was completed in Washington which provided the pioneers with warp for the material, leaving only the woof threads to be filled in. In celebration of the completion of the factory, the entire countryside attended a dance of which Mrs. Pearce says

“Oh, we had good dances; we waltzed and schottisched, and square danced until nearly morning. I despise these dances nowadays. I don’t see how they get any fun with all their a-twisting.”

Mary Jane was married to James Pearce at St. George in 1867, the ceremony a culmination of a boy and girl attraction. The covenant was read by Erastus Snow.

Hardships of keeping house were but of the few confronting these people, but even the scarcity of soap must be met, and the women found they could obtain suds by digging up ooze roots, pounding them with an axe to start the lather. Mrs. Pearce lays claim to having dug many, many sacks of ooze roots.[14]

After nine years of residence in St. George, the young couple was called to help settle eastern Arizona. In 1876 they reached Panguitch and on October 18, 1877, they started for Woodruff, Arizona, arriving December 13 of the same year.

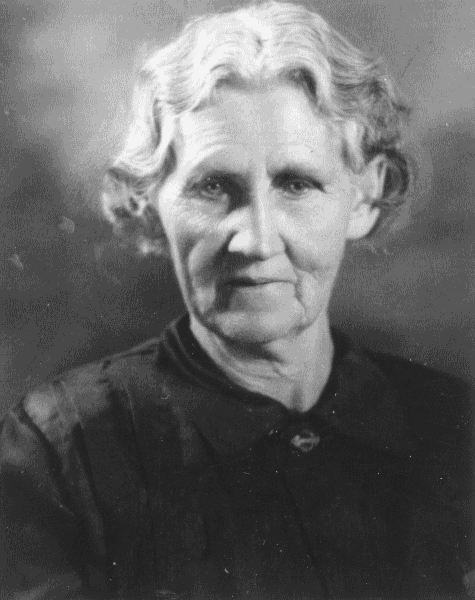

Mary Jane Meeks Pearce, December 2, 1931, her eightieth birthday. Photo courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

Mary Jane Meeks Pearce, December 2, 1931, her eightieth birthday. Photo courtesy of International Society Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

In addition to doing all the cooking and caring for four children, her husband, and a hired man who made the trip to Arizona in trade for a mule, Mrs. Pearce drove a team and wagon the entire distance. After some exploring done by James Pearce, he decided to move his family nearer to what is now Snowflake. As the couple topped the hill, coming in view of the Stinson ranch and what is now Snowflake, Pearce told his wife the entire valley belonged to James Stinson. She replied:

“Well, this is too good a place for one man to have it all. It won’t be more than two years before our people will have this place.” And within a year W. J. Flake and company had purchased the valley, fulfilling the prediction.

The family moved on toward what is now Shumway, Arizona. Here Pearce and J. H. Standifird purchased a ranch and farmed it for two years. The house was a half dugout with the lumber hand cut and hand sawed from Arizona pine. Mrs. Pearce made butter and cheese, selling it at Fort Apache during their stay here. At night she always managed to have the table cleared so “Pa could stand it up in front of the door to keep out the Indians.”

The first white child born on the Silver Creek was Elizabeth Pearce, now Mrs. Al Brimhall of Fruitland, New Mexico. Once during the absence of the men, Mrs. Pearce was left with a neighbor who was very ill. While Mrs. Pearce was attending the sick woman, several Indians entered the house. Mrs. Pearce decided to play on their superstitions and persuaded them to believe the woman was dying. The Indians immediately left, fearing the evil spirits.

Later, when questioned concerning the incident and her own thoughts at the time, she said: “Oh, they were just Indians, and I knew they were killing people all around the country.”[15]

When the first Relief Society was organized in Taylor, Mrs. Pearce was the second woman asked to act as a teacher. In 1888 she was made second counselor to the Relief Society president.

Later, the family moved to Shumway, and here she was active in Relief Society, religion class work, was chairman of the school board, and was assistant postmistress under her husband, James Pearce.

The Pearces are responsible for many acres of the fine plum trees planted in the Taylor region and bearing fruit today.

Their next move was to Snowflake where a two-story brick house was purchased. During the six years of residence here, a diphtheria epidemic claimed five of the Pearce grandchildren.[16] They then decided to leave and started for New Mexico. The children were ill with diphtheria and had to be quarantined (during the trip) in one wagon, while other members of the party rode in a second wagon.

They settled in Jewett on the San Juan River.[17] Mrs. Pearce immediately became active in Church duties and was instrumental in building and finishing a new chapel for the Jewett Branch. Donations of fruit, eggs, beans, and some cash were received toward paying for the building, and it was built by the men and painted by the women.

On December 10, 1904, Mrs. Pearce was made first assistant superintendent of the Sunday School and the next year was president of the Relief Society.[18]

In 1909 the couple sold their New Mexico property for $4000 and returned to Taylor, Arizona, buying the lot and building the house which is still home to the pioneer woman.

Since the death of her husband in 1922, Mrs. Pearce has spent the winters in Utah, visiting [family], and working in the Arizona Temple where she is continuing a life of service begun many years ago in a new and unexplored country. She was the mother of eleven children. She passed away October 13, 1941.

Ellis and Boone:

Northern Arizona pioneers, including the Pearce family, experienced near starvation their first winter in Taylor. Another Taylor resident, James Jennings, recorded the kindness of one non-Mormon neighbor. Jennings wrote:

Things were rough that first winter. There was no flour, but John [Standifird] did manage to get some barley meal. One day, while John was away, some range cows came down to the creek for water. Mother Standifird said to the teenage daughters, ‘Here is our chance for some milk. Lets [sic] go see if we can drive them into the corral.’ They were wild Texas cattle and had probably never before seen a woman. The women mounted the ponies and soon had three of them in the corral. Then with their lasso ropes they soon tied the cows down and milked them.

The cows belonged to Mr. [Corydon] Cooley, of Indian scout fame. Mr. Standifird sent word that they were milking some of his cows to see the babies through the winter. Cooley sent a message to keep the cows, ‘but do not starve the calves.’[19]

Also, with the Pearce family living in a half dugout, it is easy to understand a second story from Jennings. The details that he adds about the birth of daughter Elizabeth (whether true or not) definitely spice up the account. He wrote, “The Pearce family stayed in the dugout home. During this time Jane gave birth to her fourth [fifth] child. As she lay on a pallet on the dirt floor, in labor, a large bull snake slithered across the floor beside her. She called to her little son, Jim, to hand her the butcher-knife with which she whacked off the head of the snake and then watched the tail wiggle in the convulsions of death.”[20]

Finally, this story from granddaughter Georgia Young McGee provides a bit of local color to Mary Jane’s profession as midwife and nurse. McGee wrote:

Grandma was a licensed midwife for Arizona, and delivered over one hundred babies throughout the entire area. She was also a practical nurse. I turned seven years old while we were staying with Grandma. I will never forget the story that she told us kids about where babies came from. Mother was expecting her seventh child, and was having a very difficult time. For three months she had been right in bed. The day that my brother Leo August, was born, August 22, 1922, Grandma Pearce kept all of us kids out of the house. Aunt Gladys Pearce, who lived across the street, was trying to keep us under control. Grandma finally came to the door holding a tiny baby in her arms and told us that we had a baby brother. We did not let up, but kept asking Grandma where she got him. She finally gave in, and pointing to a big straw stack said that she got our new baby out of the straw stack. Grandma always wore a long white apron hanging from her waist and when she said that she heard a baby cry and took it out of the straw stack and wrapped it in her white apron and put it in bed with mother, it made sense to us kids.

After Grandma went inside with the new baby we got our smart little heads together and figured that if Grandma only got one baby out of that big straw stack, there should be a lot more babies still there. With the help of the neighborhood kids, we took that straw stack apart. The wind was blowing hard, and straw was flying all over Taylor before Mother decided to tell us the truth. Leo had not been found in the straw stack. He had been hatched out of an egg, along with the new baby chicks, in Mother’s bed.

And this is how that happened. A dog had killed the big black setting hen a few days before the eggs were ready to hatch. Grandma Pearce said we needed those chickens, so she punched some holes in a five-pound baking powder can, put in a few feathers, and then added the eggs from the deserted nest. Then she put the can in Mother’s bed so the eggs would be kept body-warm until they hatched. The chirping, tiny yellow chicks hatched out of those eggs the same day that Leo was born, so it was easy for us kids to believe that Leo hatched out of one of those eggs.[21]

Rhoda Condra McClelland Perkins

Rhoda Perkins Wakefield

Maiden Name: Rhoda Condra McClelland

Birth: October 20, 1821; Tompkinsville, Monroe Co., Kentucky

Parents: Josiah McClelland and Rhoda Condra

Marriage: Jesse Nelson Perkins; January 14, 1841

Children: John Henderson (1842), Littleton Lydle (1847), Brigham Young (1850), Heber Kimball (1852), Jesse Nelson (1854), Reuben Josiah (1856),[22] Franklin Monroe (1859), Rhoda Elizabeth (1862)[23]

Death: April 15, 1891; Taylor, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Taylor, Navajo Co., Arizona

My grandmother’s family, the McClellands, was of Scotch Irish descent. Some of the ancestors had set sail for America as early as 1685. Our branch first settled in Pennsylvania, then North Carolina and Virginia, and later moved to Tennessee, Kentucky, and Missouri. My grandmother was born in Monroe County, Kentucky, [on] Oct. 20, 1821. She was the fourth child of Josiah McClelland and Rhoda Condra. This name has continued to be handed down to daughter and granddaughters with a second name added for variation.

While she was yet a small girl, her father built a home in Jackson County, Tennessee, where Rhoda grew to womanhood. She learned to row a boat equal to the native tribesmen and was an excellent horseback rider, typical girl of the Bluegrass State.[24]

In another migration with relatives and friends who were constantly moving toward the west, to me it seems preparing to hear the gospel message, their travels took them to Missouri. We have found record there where Jesse Nelson Perkins and Rhoda Condra McClelland were the first couple married in Mercer County, Missouri, January 14, 1841. They settled on a new farm with the intention of making a permanent home, but when the Mormon elders found them and taught them the gospel, which they knew to be true and accepted, these plans were very much changed. Mob violence ran high, and they suffered persecution as hundreds of other Saints had done at the hands of cruel, vicious mobs when they were driven from their homes and forced to leave all possessions behind.

At the time Jesse and Rhoda heard the gospel [in 1848], they had two little boys ages six and one year. They had accumulated some property and were comfortable in their good two-room home. Those hostile Missourians were heartless and unfeeling. Many would be preachers, professing to be ministers, were leaders in the persecutions.[25] My grandparents were forced, by a group who had threatened to burn their home if they did not get out, to move again and make another start in life. They loaded what few things they could get into one small wagon and under cover of darkness took their departure into the wilderness leaving their bins full of grain, their smoke house full of meat, all for the sake of the religion they had embraced. Grandmother was the only one of her family who ever joined the Church. After a few months they started with a company of Saints for the Rocky Mountains. They arrived in Salt Lake City [on] October 18, 1849.[26]

Rhoda Condra McClelland Perkins. Photo courtesy of Ida Webb Collection, Taylor Museum.

Rhoda Condra McClelland Perkins. Photo courtesy of Ida Webb Collection, Taylor Museum.

They settled in South Bountiful, where they made a good home and where they lived for twenty-five years. In regular succession, the children came until nine sons were born to them. Rhoda was rewarded at last with a beautiful daughter, Rhoda Elizabeth, the pride of the family. The family had prospered in material things and were more than content in their comfortable home, and some of the boys were now married with homes of their own. Brigham Young, knowing the family well, said they were just the kind of family he needed to help build up the southern part of the state. They knew him to be a prophet and leader, and when the call came, “To your tents Oh Israel,” every member obeyed that call.[27]

They spent their first summer on the Sevier River. Here Grandmother put down kegs of butter which kept sweet and helped feed her big family for months to come. They bought land near Panguitch where they began again to establish themselves in good homes, but scarcely two years had passed when the call came to move on to Arizona to which ever part they chose to settle. One after another party was winding its way to Arizona then almost an unknown land but for the uncivilized natives, the Navajos and warring Apaches.

My grandparents knew they were going into this little known country, and before they left, there was some important work that must be done. The St. George Temple had recently been completed, ready for the sealing of families, work that had previously been impossible to have done. For two weeks the family was camped on the Virgin River while much of their temple work was completed.[28] They crossed the Colorado River December 31, 1877. That night the river froze over solid enough for many to cross on the ice.[29] What a time of year for families to be traveling. No wonder our people headed for the sunny land of the Salt River, but there would still be plenty of cold weather before their teams, some of them oxen, could travel the distance yet to go. They arrived at the little settlement first called Fort Utah, now called Lehi, March 7, 1878.

Once again the family bought land and water rights preparing to make permanent homes. They set out orchards, planted wheat and oats, put in gardens of melons and other vegetables. They made many friends with both white and Indian neighbors and, with true southern hospitality, entertained many travelers seeking new homes.

A meeting was held in one of their big tents, when with other brethren, Apostle Erastus Snow, often called the Arizona Apostle, called and set apart Jesse Nelson Perkins to preside over all the Saints in the Salt River Valley, the first to this position. Some of the boys had driven their loose stock down on the San Pedro River for better pasture; there they contracted bad cases of malaria. Owing to the severe illness of his family, Grandfather was released from his position to move them to a higher climate, and they decided to go to northern Arizona. The Perkins family arrived in the little settlement scarcely more than a camp, called Walker, afterwards changed to Taylor, January 4, 1879. Much improved in health, they soon began securing more land preparing to build homes.

At a special meeting held in her home, June 1880, some brethren of the Priesthood with Wilmirth East, Relief Society president of Eastern Arizona Stake, organized a Relief Society and set her [Rhoda Perkins] apart as president. Later, when Taylor Ward was organized with John H. Standifird as bishop, she was again sustained to that position. The ward was organized August 1880. This position she held until after the deaths of her husband and son John, who passed away with that dreaded disease known then as black smallpox.[30]

While she was Relief Society president, the call came for the women to store up wheat. To this cause she donated liberally. Four of her sons filled missions; others were bishops. Some were high councilmen as well as holding other important positions. She was a faithful wife and devoted mother. We have reason to bless the name of our little grandmother who passed away April 15, 1891.

Ellis and Boone:

In 1986 when Brigham Young University published papers which had been presented at a conference in Tucson, Arizona, the paper by Keith W. Perkins was titled “A Personal Odyssey” and included information about his great-great-grandfather Jesse N. Perkins. Here is the story of the deaths from smallpox at Taylor:

My second great-grandfather, Jesse N. Perkins, became the postmaster at Taylor; and his son John H. Perkins, became the mail carrier. John made frequent runs to Holbrook, when he picked up the mail and distributed it to the various settlements, ending up at Taylor. One night he stopped over in Holbrook, and for some strange reason the landlady forgot to tell him that a few days before, a man had died in the bed he had spent the night in from smallpox. John H. returned to Taylor, to what fate he did not know, since he had never had smallpox. They held a family council to decide the course they would take. The decision was simple. Rhoda, the mother, took the rest of the children and moved across the street. Dad, Jesse Nelson Perkins Sr., took care of their son.

Soon John contracted smallpox. Jesse cared for his son the best he could. Mother and father visited frequently, but never came closer than across the street. She brought supplies and medicines to her side of the road and carried information from her husband to the family. John grew steadily worse and finally passed away. Jesse, with the help of a friend, Joseph C. Kay, who had survived smallpox previously, took care of John’s final arrangements and burial.

Now the father, Jesse Perkins Sr., became ill with smallpox, and the only one who dared care for him was Joe Kay. Joe did the best he could for his friend, but after the disease had run its course, Joe Kay had to bury Jesse. The house was fumigated before the family moved back in; everything that could have been contaminated was destroyed.[31]

Another descendant, granddaughter Lucille Plumb, wrote, “How do you measure the devotion of this father? Or this pioneer mother? Each chose the role that was most important to the welfare of their family.”[32]

Sarah Catherine Hancock Perkins

Sarah Perkins Duncan[33]

Maiden Name: Sarah Catherine Hancock

Birth Date: February 23, 1870; Leeds, Washington Co., Utah

Parents: Mosiah Lyman Hancock and Margaret McCleve[34]

Marriage: Franklin Monroe Perkins;[35] March 20, 1889

Children: Sarah Alice (1890), Franklin Monroe (1892), Heber Kimball (1894), Jesse Joseph (1896), Rhoda Inez (1898), Brigham Dewey (1900), Katie May (1901), John Renmore (1902), Margaret Zella (c. 1905), Marion F. (c. 1907), Charles Fenton (1909), Edith (1912), Vaughn Elwood (1914), Ida L. (1916)[36]

Death: March 2, 1938;[37] Taylor, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Taylor, Navajo Co., Arizona

Sarah Hancock Perkins was the daughter of Mosiah Lyman Hancock and Margaret McCleve Hancock, born February 23, 1870, at Leeds, Utah. As a child she lived in Leeds with her parents. Her mother had a small store there which helped earn a living for the large family of twelve children. One child more was added after they arrived in Arizona in 1880.

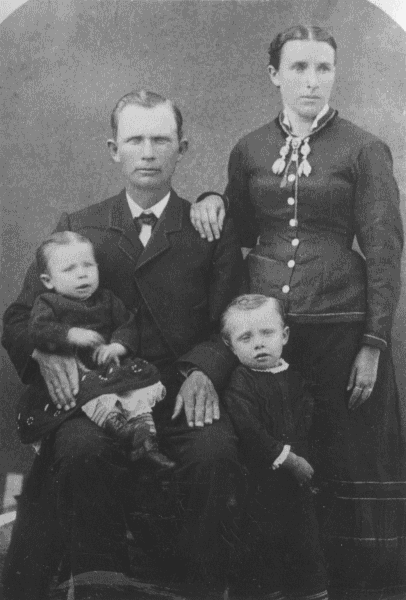

Frank and Sarah Perkins family, left to right: Frank, Joseph, Frank (father), Sarah, Sarah (mother), Inez, Heber. Photo courtesy of Ida Webb Collection, Taylor Museum.

Frank and Sarah Perkins family, left to right: Frank, Joseph, Frank (father), Sarah, Sarah (mother), Inez, Heber. Photo courtesy of Ida Webb Collection, Taylor Museum.

In addition to the work and cares of such a large family, Margaret Hancock was set apart by the Authorities on her arrival in the community of Taylor, Arizona, as midwife and nurse to those for miles around. She is said to have brought no less than two hundred children into this world, and that, without loss of the mother. Many youngsters were tenderly nursed through sicknesses of childhood and epidemics of both major and minor importance, and this faithful little nurse and mother finally gave her own life up to the cause for which she had labored diligently for so many years.

Little Sarah learned to work along with her mother early to help out with the other children. She was loving and kind to those in her care, was always free of heart, and never turned any away hungry or in need. When eleven years of age, she was out helping other women in their homes taking care of little ones while new babies were coming to add to the number of that household.

She was given a blessing which said she had been called to this country to be associated with her husband. The Perkins family arrived only one year earlier (1879) than did the Hancock family (1880). Franklin Monroe Perkins and Sarah Catherine Hancock were married on March 20, 1889, and made the trip back to St. George, Utah to the temple there to have the marriage performed in the way they believed was right.

Sarah saw many hard experiences in her early life in Taylor. Her family was her joy, and she stood willingly beside her husband in the rearing of a large family and bravely shared the pioneer hardships which the settlers of a new land are required to do. She was uncomplaining and enduring in all conditions and lived humbly before her fellowmen. She helped encourage those about her and always set a good example to others.

Her home was always open to visitors and strangers and many young people were drawn to the doors of this stalwart couple and their large, loving family. Somehow there was always warmth and love within those walls and room for one more, often many more.

Frank and Sarah Perkins family: front, left to right: Vaughn (baby), Fenton, Marion; second row: Dewey, Sarah, Zella, Frank, Renmore; back row: Frank, Sadie, Heber, Inez, and Joseph. Photo courtesy of Ida Webb collection, Taylor Mueseum.

Frank and Sarah Perkins family: front, left to right: Vaughn (baby), Fenton, Marion; second row: Dewey, Sarah, Zella, Frank, Renmore; back row: Frank, Sadie, Heber, Inez, and Joseph. Photo courtesy of Ida Webb collection, Taylor Mueseum.

Both she and her husband worked faithfully in the Church, which was a great pleasure to them. She especially loved visiting teaching and was a wonderful example of what a teacher should be in the fifty years of service in this capacity.

She also went with her husband to help hold down a homestead in Clay Springs, Arizona, and saw the building up of that little ward and community.

She became the mother of fourteen children. Two of these died in infancy, and another lived to be a young man, but was drowned in Black River in his youth.[38] The rest have married and lived to raise families who have settled in various places throughout Arizona and California.

Note added by Rhoda J. P. Wakefield:

Aunt Sarah passed away at her home in Taylor in her 70th year, in March 1938, mourned not only by her family but by numerous friends. She was a true Latter-day Saint and taught her children to walk uprightly before the Lord. Of her it may truly be said, “She stretcheth out her hand to the poor, yea she reacheth out her hand to the needy. She looketh well to the ways of her household and eateth not the bread of idleness. Her children rise up and call her blessed, her husband also. A woman that feareth the Lord, she shall be praised.”[39]

Ellis and Boone:

Roberta Flake Clayton once wrote that trying to make the fastest time to St. George and back was the goal of every matrimonially minded couple, and “Mr. Perkins was very proud of his matched team of high-stepping horses, and claimed that he would make the trip to the temple and back faster than it had ever been made.”[40] They chose to take Sarah’s younger sister, Rebecca, possibly as a chaperone.[41] Initially, the only temple available for Latter-day Saint couples wishing to marry was the St. George Temple, and so many from Navajo and Apache Counties used the Lee’s Ferry route that Will C. Barnes finally called it the Honeymoon Trail.[42] At this time, however, the route was simply known as the Mormon Wagon Road.

Mary Andersen Peterson

Author Unknown

Maiden Name: Mary Andersen

Birth: June 22, 1856; Bredstrup, Odense, Denmark

Parents: Hans Anderson and Maren Jensen

Marriage: Peter O. Petersen;[43] February 14, 1876

Children: Mary (1876), Anna Janette (1879), Sena Lenore (1881), Peter (1883), Wilford (1885), Alma (1887), Andrew (1890), Emily (1892), James Ammon (1894), Sylvia (1897), Lillian (1900)

Death: May 22, 1938; Thatcher, Graham Co., Arizona

Burial: Thatcher, Graham Co., Arizona

Mary Andersen was the fifth child of ten children born to Hans Andersen and Maren Jensen, June 22, 1856, at Bredstrup, Odense, Denmark. Her father tended land which consisted of seventy acres of timberland on the beautiful island known as Fyen Island and was quite prosperous. Her mother was known as the “honest miller’s daughter.” Her great-grandfather built a mill on the highest hill of the island, and it was handed down from one generation to another, each one taking great pride in keeping up the family honor and name which they had won of being the “honest miller.”

Peter O. and Mary Andersen Peterson family, 1914. Front, left to right: May Brown, Peter O. (father), Lillian Mulleneaux, Mary (mother), Sena Kempton; back: Peter, Wilford, Alma, Andrew, and Ammon. Photo courtesy of Eastern Arizona Museum and Historical Society, Pima.

Peter O. and Mary Andersen Peterson family, 1914. Front, left to right: May Brown, Peter O. (father), Lillian Mulleneaux, Mary (mother), Sena Kempton; back: Peter, Wilford, Alma, Andrew, and Ammon. Photo courtesy of Eastern Arizona Museum and Historical Society, Pima.

Hans and Maren had been married about nine years when two missionaries knocked at their door and were invited in, given something to eat, and a place to sleep. They listened to the story the missionaries told and were impressed with the gospel message, but they did not accept it at that time. However, from that time on, every Mormon elder that went to that island always found a glad welcome with Hans and Maren. Among the elders who went there were William W. Cluff, Patriarch John Smith, Erastus Snow, and Knud H. Bruun.[44] During this period, something happened that opened their eyes to the truthfulness of the Mormon gospel. Their oldest boy, Andrew, was kicked in the head by a horse, crushing his head so badly that the doctor said he could not live. In great grief and sorrow the father went to a grove of trees near the house where he knelt down and prayed to God to save his child, promising him that if he would, he would join the Church and give and do all in his power for the building up of the Church. This promise he kept all his life, for when he went back to the house his child was greatly improved, and with the elders to administer to him, the boy made a rapid recovery, the injury leaving only one scar on his head, which his hair covered.

On March 13, 1861, Elder K. H. Bruun had the pleasure of baptizing Hans and Maren into The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Two years later, they sold nearly all their possessions and their rights to rent the land on the island and on April 18, 1863, left Denmark with their seven children, also paying the passage for some friends that did not have the means to travel.

They left Liverpool on April 20, 1863, on the ship John J. Boyd in company with 755 Saints under the direction of William W. Cluff.[45] They were five weeks on the water. Mary was seven years old and told the following incident: “One day a whale came up to the vessel and raised its head up, leaning against the boat. The captain ordered all the people to go to the opposite side of the ship so it wouldn’t tip over, then ordered some of the men to bring buckets of potatoes which they poured into the whale’s mouth until finally it slid back into the water and went away.”

They landed at New York [on] June 1, 1863, and took the train to St. Joseph, Missouri, then a boat to Florence, Nebraska, to go across the plains in John R. Young’s independent company. They brought to America $20,000, more gold coins than any other immigrants up to that time. The mother had made a sort of slip of strong material to hang from the shoulders like a sleeveless blouse. For her and the two older girls, she had sewed three rows of coins around the bottom of this slip, and the younger girls had two rows on theirs. The rest of the gold pieces were in a large bag. They also brought many other things, such as large iron kettles and brass kettles and two cross cut saws. When they left Nebraska, they had two wagons, four yoke of oxen to each wagon, and one light spring wagon or hack for the women to ride in, which was drawn by a team of horses.[46] Also, they had provisions for fifteen people.

They arrived in Salt Lake [on] September 12, 1863. A great many of their friends went on south, but Hans felt impressed to go north, which he did. After getting settled in Logan, the older children worked for others in order to learn the language faster. Mary was privileged to go to school only a few months. Once she ran away from school and hid on a haystack and was crying because the children laughed at her Danish brogue, but her mother and teacher, Louisa Balliff, found her and took her back to school.[47] She learned to sew and card wool and the other things girls of that time were taught. As she grew older she was sent to the ranch, with her brother Andrew, to take care of the milk and help with milking and feeding the cows. While on this ranch one day, they were feeding the cows, and Andrew didn’t think she could lift a certain forkful of hay, and in attempting to show him she could, she hurt her back which gave her trouble the rest of her life. Life on the ranch was lonely and she loved to dance, but if they went to a dance they had to walk ten miles into the town.

Several other Danish families were living in Logan.[48] One young man, Peter “O” Petersen, who had been on his own since he was nine years old, was working on the St. George Temple and received a call from President Brigham Young to get married and help settle Arizona.[49] He asked Mary to share this call with him. Her father did not approve, but as she was of age, they finally decided she could go. Her brother Andrew and his young wife, Janet Henderson, also answered the same call.[50]

On February 7, 1876, they left Logan on bob-sleighs [bobsleds] to start their new venture. They were married February 14, 1876 in the Endowment House. There were about 200 people in the company, forty families and some single people. The way was rough and long, thirteen weeks from Logan to Obed. They crossed over “Lee’s Backbone” where the rocks were so large that some places there was barely room for the wagons to pass through and so steep that ropes or something had to be tied to the back of the wagons to trees to keep them from falling on the horses. They crossed the Colorado on a ferry, but when they got to the Little Colorado, they piled things high on the water barrels and floated the teams and wagons across. At Obed, a rock fort was built, and they tried farming near it. A spring of clear water flowed nearby but, when drinking it, caused them to have chills and fever. They found that the land was not good for farming and about eighty percent of the people went back to Utah.[51] While still at Obed their first child was born November 18, 1876. They named her Mary, but always called her May.

Peter “O” became discouraged and wanted to go back, but Mary would not go. She had that trait and faith that when she was sure she was right she would not change. She said they had not been released from the call given them and sat in the doorway of their little room, holding her baby and crying, while Peter was preparing to leave. But again, Andrew, her brother, assisted by talking to him, persuading him to stay.

In 1878, they were sent back to Utah for supplies. When it was time to return, the baby May was so ill with what they called lung fever that they could not travel, and when she was well it was too late in the season, and Mary was quite ill carrying her next child, another girl, born in Logan, March 18, 1879. As soon as they could travel, they left again for Arizona, going to the settlement of the Saints in the Order at St. Joseph.

While living in the Order one summer, Peter and Mary and another young family, Henry and Eliza Tanner, were sent to Mormon Lake to take care of the cattle.[52] They made 1300 pounds of butter and 2000 pounds of cheese for the Order. Mary had learned to be very thrifty and saved enough money to buy a sewing machine.

They moved to the Gila Valley in November 1882, and not more than three weeks later, their second daughter died of spinal meningitis.[53] They farmed just north of the Gila River. Mary was in a tent when her fourth child, a son, was born.[54] Peter had built a brush shed over it to keep it a little cooler, but as she lay in bed a whirlwind came and lifted the top off the shed and blew the tent down on her. As soon as possible, they built a log house which they lined with factory, as they called unbleached muslin. When it rained and the dirt roof sometimes leaked, that lining was taken down, washed, and put back up.

They worked in the ward; Peter was in the High Council, served also as bishop, and Mary worked in the Primary and was president of the Relief Society.[55] She was a good housekeeper, a very good seamstress, and a marvelous cook, using fifty pounds of flour each week for her good bread, when her five boys were at home. When the grandchildren would come, they always asked for bread and butter instead of candy or cookies. She was very thrifty, could hardly stand to see anything wasted, especially food. She taught her children to be strictly honest, to be dependable, and do their best. One of her pet sayings was: “Few can see how long it takes you to do a thing, but everyone can see how it is done.”

Mary had many trials to endure other than suffering with her hurt back; eleven children without a doctor didn’t help much.[56] One period she had sciatic rheumatism so severely she never slept a whole night in bed for twelve years but had to sit up in a big chair; heat seemed to be the only thing that eased the pain, and each morning she forced herself to walk around to exercise her leg until it felt better. It was during this period of suffering that her youngest son, Ammon, was in Europe serving in the First World War; and in 1919 she was proud to have her youngest child, Lillian, go on a mission for twenty-one months. Then she had a very bad sick spell and Lillian came home.

After the children were all married, she and Peter moved into town to be close to the church, stores, and post office. Then she took care of her husband when he was so ill with cancer just before he died.[57] She lived ten years longer, with her daughters taking turns looking after her. On Mother’s Day in May of 1938, she had a stroke and passed away two weeks later at her home in Thatcher, Arizona.

Ellis and Boone:

Some of the trials that Mary Petersen endured are not mentioned here, including the death of daughter Sena’s husband, Martin Kempton, in 1918.[58] This incident happened at the height of patriotic fervor (or resistance to the draft, depending on personal viewpoint) of World War I. On February 10, Graham County Sheriff Robert Frank McBride, Undersheriff Kempton, Deputy Thomas Kane Wootan, and U.S. Marshal Frank Haynes traveled to a remote canyon of the Galiuro Mountains southwest of the Gila Valley to arrest Tom and John Power on a charge of draft evasion. Before dawn, the lawmen surrounded the cabin, and when the shooting stopped a few minutes later, Jeff Power, father of Tom and John, lay dying, and three lawmen, McBride, Kempton, and Wootan, were dead. Tom and John Power, with hired hand Tom Sisson, fled toward the Mexican border and over 1,000 lawmen, soldiers, and civilian volunteers hunted the fugitives for almost a month before the men surrendered to a U.S. Cavalry troop in Mexico.

The lawmen’s deaths and resulting trial and incarceration of Tom and John Power left divisions and bitterness in the Gila Valley which lasted for decades. Some of these divisions were along religious lines, but only two of the lawmen were Latter-day Saints. After a quarter century in prison, the men were finally granted a parole hearing, and about twenty relatives of the slain lawmen attended to protest. This quote from Barbara Wolfe (who is not LDS), when writing about the 1952 hearing, illustrates the divide: “That so much bitterness had survived more than thirty years astounded prison officials. More appalling was the families’ unshakable faith in groundless rumors denied by evidence. Like the bitter hatred that blinded them, the rumors had become a family legacy passed from generation to generation. Most of the protesters were good people by any standard, but their self-righteous loathing of the Powers was shocking in its magnitude and horrifying in its intensity.”[59]

Applicable to the life of Mary Petersen is the story of grandson Glenn Kempton, who was thirteen years old at the time of his father’s death. Kempton said, “There grew in my heart a bitterness and a hatred toward the confessed slayer of my Father,” but after high school, Kempton accepted a call to serve as a missionary in the Eastern States Mission.[60] With the intensive gospel study common on any mission, Kempton came across Matthew 5:43–45 and Doctrine and Covenants 64:9–10, both of which teach the need to forgive. Kempton knew that he needed to speak with Tom Power after returning home, but with marriage and employment, the years quickly passed. He said that “guilt arose within me every time I thought of the appointment I had not kept.”[61]

One year, shortly before Christmas, Glenn Kempton made the trip to Florence, talked to Tom Power for about an hour and a half, and upon leaving, extended his hand (which Power took) and said, “With all my heart, I forgive you for this awful thing that has come into our lives.”[62] Kempton did not indicate that this encounter fully satisfied Tom Power who always believed that the lawmen shot first, but the Glenn Kempton story has had a powerful influence among Latter-day Saints all around Arizona. Kempton became a bishop and often spoke at firesides on the subject of forgiveness.

President Spencer W. Kimball lived in the Gila Valley in 1918 and for many years afterward. He included this story, much of which was in Kempton’s own words, in the book, The Miracle of Forgiveness. Kimball also told of one instance when he used this story in counseling a young widow with a bitter heart. He wrote, “Not only had Glenn Kempton found the joy of forgiving, but the example he set as a faithful Latter-day Saint has had far-reaching influence on many others who know his story and have heard his testimony.”[63]

Mary Elizabeth Bingham Phelps

Barbara Ann Phelps Allen[64]

Maiden Name: Mary Elizabeth Bingham

Birth: December 25, 1853; East Weber, Weber Co., Utah

Parents: Calvin Bingham and Elizabeth Lucretia Thorne[65]

Marriage: Hyrum Smith Phelps;[66] September 8, 1873

Children: Mary Laurette (1874), Lucy Ett (1876), Barbara Ann (1877) , Gove Edward (1878), Harriet Emeline (1881), Orson Ashael (1882),[67] Lester Leo (1883), Yuma Letitia (1885), Amy Dorothy (1887), Grace Darling (1889), Esther (1890), Clara (1893), Martha Gertrude (1895), Wilford Woodruff (1896)

Death: November 17, 1933; Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Mother was born on Christmas day, the year 1853. She is the daughter of Calvin Perry and Lucretia Thorne Bingham. Her early life was as useful and busy as were her later years. She worked out some, and she helped her grandfather Ashael Thorne make butter and cheese and other work to be done on a farm.

When she was a young lady, she earned money to buy herself a nice yellow calico dress with black dots on it and thought it most beautiful. She, like Father, loved to dance; she said often after midnight a crowd would get into a sleigh and ride until daylight.

Mary Elizabeth Bingham Phelps. Photo courtesy of Stephen Phelps.

Mary Elizabeth Bingham Phelps. Photo courtesy of Stephen Phelps.

She had quite a number of boyfriends; one in particular she liked real well. It was while she was keeping company with him that she married Father (Hyrum Smith Phelps) as a plural wife; said she didn’t know why she did it, but supposed it was meant to be that way.[68]

At the time she married, they lived in Montpelier. The weather was too cold, and they moved to Mesa, Arizona, after three daughters had been born, Laurette, Lucy, and Barbara. Laurette died with diphtheria before leaving Montpelier.[69]

The journey to Arizona was a long hard one, especially for Mother, as she was in delicate health. The company laid over three days at Lee’s Ferry because of her condition. On the third day, December 2, a son, Gove Edward, was born, and the same day traveling was continued. They left October 3, 1878, and arrived in Mesa January 17, 1879. Mesa was practically a desert when they arrived. They lived in tents the first three months, or until Father could make adobes to build a house. The first one was a long three room house. Mother lived in one end, and Aunt Clarinda the other. The center room was used for a while [missing words]. While she lived there, her son Ashael died.[70]

In 1881, Father built a house on the corner of First Avenue and Hibbert Street for Aunt Clarinda. This house was a “T” shape with a porch on two sides, had a shingle roof and dirt floors. It still stands today, but has been improved. Mother had the long house now to herself. It was here Hattie, Orson, and Yuma were born. The officers had been after Father, and Mother for plural marriage, and they got Father and arrested him. He was sent to Yuma, Arizona Penitentiary for three months.[71] Mother was taken to the home of Ed Jones in Lehi. She stayed there until just before Yuma was born, then went to her mother.

Father bought or traded and got 80 acres one mile east of town, known now as Frazier Acres. He built another home there for Aunt Clarinda who had a family of boys and moved Mother to the home on First Avenue and Hibbert because she had mostly girls. Here Grace (she only lived a few weeks), Amy, Esther, Clara, and Gertrude were born.

Hyrum S. and Mary Elizabeth Bingham Phelps. Photo courtesy of Stephen Phelps.

Hyrum S. and Mary Elizabeth Bingham Phelps. Photo courtesy of Stephen Phelps.

After Aunt Clarinda moved to the ranch, Mother was allotted a few cows for her support. It was Gove’s job to drive the cows to and from the pasture. He often rode a cow called Puso. I remember we had a lot of grief because the cows would often get out of the corral and get in Bro. Hibbert’s place at night, and he would come and awake Mother and say ugly things to her. We milked some of the cows that were brought from Montpelier. When Esther was a few months old, Father went on a mission to the Southern States. Mother lived in this home until 1895 when Father sold it and built her a nice brick house on the 80 acres. Wilford, Mother’s fourteenth child, was born here. He was the pride and joy of the family. Father used to call him the little prophet. He is four months younger than my oldest son Ashael. Mother practically raised him with Wilford. They were like brothers.

While living in this home, Mother’s greatest sorrow came when Lucy passed away. At the time, she [Mother] was confined to her bed with a sore leg and couldn’t go see her [Lucy] during her sickness. Lucy had blood poison after the birth of Lucy, her fourth child. Brother Calvin was sure good to Mother during Lucy’s sickness; he would come three times a day to keep her informed on Lucy’s condition.[72] Sometimes he would call at midnight. Lucy died January 6, 1905.[73] Mother took little Lucy and raised her as her own.

Because of Father’s age, and the boys married and gone, he found he couldn’t do the work, so he sold to a Mr. Frazier and moved on twenty acres on Horne Lane. He built Mother the nicest home she had had and built two houses in town on Sirrine, one for Aunt Clarinda and one to rent. As age kept creeping on, he found he would have to stop work all together. He sold and moved Mother into the house he built to rent. Here they spent their last days. Father died on April 23, 1926, after having been gored in his belly by a bull.[74] Mother died November 17, 1933, from the results of diabetes.

Mother was a wonderful mother to her family. She was a typical Bingham, the most unselfish and generous person to be found. She always went without for her family. I’ve seen her many times skim the cream off the milk and give it to Father, and she would use the skim milk. She didn’t go out very much; having fourteen children, two babies most of the time, one can understand why. One May Day there was a picnic; she sent us on ahead. Amy was the baby. Lucy and I took her and the other children on; Mother came later. When we took Amy to her, she didn’t recognize Mother and began to scream. ’Twas the first time she had seen Mother in her dress up clothes. Amy cried with hunger so Mother had to go home and change her dress so Amy would nurse.

Mother had inflammatory rheumatism while Amy was a baby. At that time there was an epidemic of some kind of fever, and Aunt Clarinda’s eldest son Hyrum had it. Father had to be with him until he died.[75] Lucy and me with Grandma Phelps had to take care of Mother and the baby.[76] She suffered something awful. Her legs were swollen twice their size, and she couldn’t bear it to be moved. After Hyrum died and Father came to help take care of Mother, he and Grandma decided to get her up on an open bottom chair and steam her. They got her on the chair, but it was cruel what she suffered during the ordeal, and the sad part was no good came from it. She finally got well.

Mother was quite spiritual. A number of times things happened and it was made known to her beforehand. One time she was in trouble and went into the bedroom to pray. As she came out, she said just above the door she heard the sweetest music she had ever heard, and as the music died away, a peaceful feeling came over her and she was comforted.

There are very few people that have suffered as much as Mother. One time she and sister Annie went into the field to glean wheat, and they came in contact with poison weeds, and their legs broke out with sores. Mother’s was the worst. Both her legs were a solid sore from her knees to the soles of her feet. It took weeks to heal them. Every summer for several years at the same time, her legs would break out with the same kind of sores, but each year they would be more mild. This was a few weeks before Grace was born. Since that time, her legs caused her a lot of misery. There were quite a lot of other things that caused a lot of suffering that I’ll not take time to mention, besides giving birth to fourteen children, without the aid of a doctor or having something done to ease the pain.

Mother was a good Latter-day Saint. She always donated liberally [and] paid her fast offering and tithing. When she began paying, she saved all her statements from the dairy so she would know how much she owed, and at the end of the year, she owed a few cents more than ten dollars. I don’t know how she managed to live. She had a few hens, but they didn’t lay any eggs until the price went down to ten cents a dozen. Lucy was the main stay of the family. Hattie and I worked some. When either of us earned any money, it was turned over to Mother; not a cent did we use for ourselves without her telling us to. She would shine our heavy shoes with stove soot. We were quite large before we could afford dress shoes. We weren’t the only poor people, however, most everyone was alike.

We had a happy home; Mother made it so. Our home was a house of prayer. We had family prayer night and morning, and I think that had everything to do with the spirit of our home. I know I speak for all of the family when I say I am thankful for our wonderful parents and what they did for us.

Ellis and Boone:

When Mary Logan Rothschild and Pamela Claire Hronek were describing the beginnings of their oral history research on Arizona women, they said that the project “had several bedrock premises: the first was that women were scandalously overlooked in the published histories of Arizona [Rothschild and Hronek cite Marshall Trimble’s Arizona: A Cavalcade of History and Odie Faulk’s Arizona: A Short History as examples]; the second was that if women in general were overlooked, minority women were invisible; and the third was that we were interested in the lives of ‘ordinary’ women, not the first doctor or professor or politician, but women who saw themselves as just like their neighbors and probably less worthy of interviewing.”[77]

Roberta Clayton could have written the same statement more than twenty years earlier when publishing PWA. Clayton wrote about ordinary women, not just the stake Relief Society presidents, and, in the context of general Arizona history and the number of times Mormon women are mentioned, Mormon women should be considered minority women. Finally, the amount that Mormon women are “scandalously overlooked,” even in Mormon sources, can be illustrated with W. Earl Merrill’s books about Mesa. By counting the number of women verses the number of men in the indexes of four of Merrill’s books, women make up only 15 percent of the people he discusses.

Actually, Merrill was heavily influenced by Clayton’s book on pioneer women. In 1973, he wrote, “No more fertile source for stories on ‘Pioneer Women of Arizona’ is to be found anywhere than in the 716-page compilation bearing that title which Roberta Flake Clayton completed in 1969 after 33 years of dedicated research.”[78] He noted that PWA contained more than forty biographies for women from the Mesa area. Then he picked five women and used brief excerpts from their biographies in PWA for his column.

One of the women Merrill used for his May 21, 1973, column was Mary Elizabeth Bingham Phelps. He used two shortened paragraphs from her sketch, including the phrase, “We had a happy home; Mother made it so.” Merrill concluded his column with these statements: “It is not by embellishment with words that memorials to a mother’s virtues are created. They are rather to be found in the reflections of her nobility that shine on in the lives of her children and their progeny. It is hoped, then, that the host of descendants of Elizabeth Allen, Ella Biggs, Margaret Millett, Mary Phelps, and Sarah Vance, along with all the rest of us, can make with our allotted days living tributes to all the noble mothers in our ancestry.”[79] Mary Elizabeth Bingham Phelps would probably agree that this would be a fitting tribute to her life.

Sarah Thompson Phelps

Barbara Ann Phelps Allen[80]

Maiden Name: Sarah Thompson

Birth: March 20, 1820; Pomfret, Chautauqua Co., New York

Parents: David John Thompson and Leah Lewis

Marriage: Morris Phelps;[81] March 27, 1842

Children: Laura Ann (1843), Sarah Diantha (1845), Hyrum Smith (1846),[82] Martha Ann (1848), Charles Wilkes (c. 1852), Amanda Angelia (1854), Olive Esphenia (1856)

Death: January 31, 1896; Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Grandma was born March 20, 1820. Her parents were David John and Leah Lewis Thompson.[83] When she was four years old, her father died, leaving her mother with seven small children, making it necessary for her to start out early in life making her own way. In spite of poverty, she succeeded in acquiring sufficient education to be able to teach school.

At the age of eleven years the gospel came to their home. She, together with her mother and the other members of the family (except one brother), joined and were baptized into The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. After joining, their friends turned against them, and from then on their trials began. They were driven from place to place and finally forced to flee to the Rocky Mountains. She was brave and courageous as a young woman.

Sarah Thompson Phelps. Photo courtesy of Stephen Phelps.

Sarah Thompson Phelps. Photo courtesy of Stephen Phelps.

When quite a young woman, she taught school. It was customary for the teachers to board among the parents of their pupils which she did, and in doing so, she learned many of the plots and schemes of the mobs to assassinate the Saints. She kept the Saints posted on what was happening. When the final plot came for the general roundup of the Saints, she made a dash on horseback to give the alarm to her people. She was followed for five miles one time but her horse, being the fastest, made her escape.

Another time when teaching school, she went to a home to collect [money], and the people refused to pay and said their intentions were to drive all the Mormons out and take the crops that they had recently harvested. She told them what she thought of them. While talking, a voice spoke to her and told her to leave next morning as soon as she arose. She did and was followed, and they tried to kill her.[84]

At the time of the Hawn’s Mill Massacre, she lived but a few miles from the mill; some of those who were fortunate enough to get away came to her home.[85] While the mob was going through the country, they crossed the creek where Grandma and all the women [were] washing clothes. She told many times how they looked, said they had their faces painted and were disguised in every imaginable way, said some of the women were so frightened they fainted but Grandma shouted hurrah for the captain. Two of the men rode up to her and asked if she wasn’t afraid of them. She said she hadn’t been raised in the woods to be afraid of owls. They asked her if she didn’t recognize them; she said she did not. They told her she should; they were her old neighbors. She then asked them what they intended to do and one replied, “Kill everyone on the creek.” Grandma asked what they had done that they should be killed; their reply was they did not know, they were only obeying orders. On two different occasions, she was chased by a mob who tried to shoot her, but their guns refused to go off.

One time, when they had been driven from their home, she said they had traveled all day in the rain and were driving their cattle. She had on a sunbonnet that was quilted so as to put cardboard slats in it, and the rain had dissolved the slats and the front of her bonnet flopped in her face. She was soaked to the skin, weary, and tired after plodding in the mud all day. As they were passing a farm house a lady saw her and invited her into her home to dry her clothes and get warm. She was taken into the parlor by the fireplace. There were two young ladies and their boyfriends sitting there, and when they saw Grandma they burst out laughing. She said she was nearly in tears; she looked them in the eye and said, “You must have been born in the woods.”

Grandmother and her mother were charter members of the first organization of Relief Society in Nauvoo that was organized by the Prophet Joseph Smith.[86]

As a young woman she was loyal to the Church and all the leaders. She was personally acquainted with the Prophet Joseph Smith, and during her life she never tired of relating the stories of the early rise of the Church—the wonderful manifestations, as well as the persecutions they had to endure.

The last time she saw the Prophet was when he was being taken to Carthage Jail. She said quite a number of people were standing in groups along the sidewalks. He stopped to get a drink of water and turning to them to tell them goodbye he said, “Remember, if I never see any of you again, I love you.”[87]

On March 27, 1842, Grandma married Morris Phelps, a widower with five children.[88] She was at the meeting when Sidney Rigdon made his claim as rightful leader of the Church. She, with hundreds of others, declared that when Brigham Young arose to speak, the mantle of Joseph Smith was upon him so much so that he looked like him, and his voice was the voice of Joseph. The Saints were assured that Brigham was the one to be their leader.[89]

A short time after Grandma was married, Grandpa was called away and a young woman came to stay with her. They moved everything into one room to make it appear like the house had been vacated. One night a mob made a raid on the little town, some entered her home (the vacant room), built a fire in the fireplace, and spent the night. Grandma and those with her heard them tell the awful things they had done to the helpless. She had piled everything against the door so it couldn’t be easily opened. The mob wasn’t aware that someone was in the other part of the house.

Troubles of a different nature came into Grandma’s life after her marriage. Her first two baby daughters died, one Laura Ann, being a little more than thirteen months. She was buried in the Nauvoo cemetery, and Sarah Diantha, who lived but two days, was also buried in Nauvoo.[90] After she died, Grandma had trouble with her breast. Dr. Woolley said it would have to be taken off but she refused, said she would die first. The brethren fasted and went to the temple and prayed until they had a testimony that she was healed. While they were praying her breast started to discharge and continued until the core fell out of the sore.

On a cold winter night [on] February 26, 1846 while they were camped on the bank of the Mississippi River, she and eight other women gave birth to babies; hers was Hyrum Smith Phelps. The family was en route to the Rocky Mountains. They started in 1847 and stopped at Mt. Pisgah for two years. They did not reach Salt Lake until September 25, 1851.[91]

They settled in Alpine, Utah, and suffered many hardships along with the other Saints. My father, Hyrum S., said [that] she never knew what it was to have a good time but always enjoyed herself by doing good to others. Says Father, “I never knew her to have a house of her own that had anything better than a dirt roof.” He went with her many times to the canyon to gather serviceberries to dry to make something extra for Christmas. He said he had gone to bed many times while she washed and mended his clothes.

In 1864, President Young called them to help settle Bear Lake, Idaho. They settled in Montpelier. Grandma’s daughter Olive tells of their severe hardships there. Their cattle and horses died from starvation and cold, all but a cow and a span of horses. Grandma did the weaving and the other things while Aunt Martha (Grandpa’s other wife) did the housework and cared for the children.[92]

In October 1878 in company with her son Hyrum, she left Montpelier for Mesa, Arizona, arriving in January 1879.[93] She was made president of the first Relief Society organized in Mesa.

Some of the things I remember about Grandma—she lived with us most of the time, but as a midwife she was gone a lot. She was a large woman and weighed about 210 pounds. Mother did her sewing. I think she used the same pattern for all her dresses for years. Nowadays we would call them the princess style. She had asthma and the only thing that gave her relief was to smoke a plug of tobacco. I slept with her most of the time. I remember in the coldest weather she would sleep with her feet out of the covers. About 4 o’clock a.m. she would begin to wheeze and cough and in order to get relief would get up and smoke her pipe.

She was often called out in the winter time to deliver a baby. We would hear a rumble of a wagon at a distance, and it never failed to stop at our house. Wind or rain, it was the same. Mother would get up and help her get off. When she left, she would be wrapped up in a heavy shawl. Sometimes she would go before she was needed and stay a week or two and always ten days after, and when her job was finished she would nearly always be given a five-dollar gold piece.

She did her spinning in the summer time, would get out under the shade of a tree and often the Indians passing would stop and watch her. After the yarn was spun she would knit socks; she also knit in the summer time while she made soap. It would take all day and sometimes longer to make a batch. She told of her experience in making soap while crossing the plains. She said one day as they were traveling, she came across the bones of a buffalo that still had marrow in them. She gathered them up and collected ashes from the camps, put them in a kettle, poured water on them, and boiled them. After she poured the water off into another kettle, put it over a fire, and when the water boiled, she added the bones and boiled it until it became soap. She said after the women saw her soap they were always on the lookout for green bones.

Grandma used to make straw hats for the Barnett boys. She would get a bundle of wheat straws, select the ends of a uniform size, soak them in water, and braid with about six straws. When the hat was finished it was larger [more expensive?] than anyone could buy.

She was a great reader; it seemed to me like she read the Deseret News from cover to cover as well as story papers and novels.

She dearly loved the Prophet Joseph Smith. In the winter time we would sit around the fire and listen to her tell of the suffering and persecution of the Saints. In her later years she seemed to live in the past.

She was quite a superstitious woman and would tell spooky stories such as evil spirits working her loom at night, and if one would turn out of a funeral procession, they would be the next one to have a death in their family. The night her daughter Amanda died, an owl hooted on the roof of the house just above her bed, she called Mother and asked her if she heard it.[94] Mother said “Yes. I heard it too and was certainly frightened.” She worried and said she knew she would hear bad news and she did.

She had a very dear friend, Grandma Averett; the last time she talked to her, they agreed that the one that died first would tell their folks on the other side how they were getting along.[95] They both died in the month of January, Grandma Averett died on the first and Grandma the thirty-first, 1896.

She was loved by everyone who knew her and was known as Aunt Sarah. She fulfilled well the calling made of her when she was set apart as a midwife. In 1870 Eliza R. Snow came to Idaho and organized a Relief Society, and Grandma was made president. About 1873, Apostle Charles C. Rich called her to be a midwife and set her apart as a nurse and midwife. She was promised by Brother Rich that she would never lose a mother. She was faithful. She was no doubt faithful because she delivered 580 babies and never lost a mother.

Many trials came into her life but she never complained. It seems all the trials she passed through only strengthened her testimony to the truthfulness of the gospel that was so dear to her.

She was the mother of seven children, whose names are: Laura Ann, Sarah Diantha, Hyrum Smith, Martha Ann, Charles Wilkes, Amanda Angelia, and Olive Esphenia.[96]

Ellis and Boone: