O

Roberta Flake Clayton and Lenora Owens Skillman, "O," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 499-514.

Louisa Jones Oakley

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP[1]

Maiden Name: Louisa Jones

Birth: October 13, 1837; Appledoor, Devonshire, England

Parents: William Jones and Mary Ann Dovell

Marriages: John Degroot Oakley; February 19, 1857

Children: John Heber (1858), Mary Ann (1859), Thyrza (1862), William Jones (1864), Louisa Dicey (1867), Lucy (1868), Vilate (1871), Ellen Kalantha (1873), Margaret (1876), Sarah (1878)[2]

Death: March 23, 1915; Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Among the pioneers of 1880 who moved into Snowflake, Arizona, was the Oakley family—the blind husband, John; his wife, Louisa; and their six daughters. The eldest was married and her husband accompanied them, [as well as] Robert Jones, an afflicted brother of Louisa. Four tiny graves were left behind them in Utah.

It took a great amount of courage to make the trip, even when everything was in one’s favor; but handicapped as this family was, it looked like an impossibility. But Brigham Young, the great colonizer and President of the Mormon Church, had called them, and the same faith and loyalty that had prompted Louisa and John to leave their English home and had sustained them on a long sea voyage and the tedious trip across the plains made them willingly undertake the journey by ox team from Kanab, Utah, to somewhere in Arizona.[3]

Kanab was the last of the Utah towns, and through it passed a stream of emigrants beginning in January 1876—companies at first and then lone families.[4] There were some who returned dissatisfied, and others who made the trip back to close out their business or settle up their affairs. Thus there were conflicting reports as to the desirability of the new land, but the Oakleys were called, and they came and arrived early in 1880.

They stayed at Woodruff a short time then came on to Snowflake where their first home was in one of the adobe stables belonging to the ranch purchased by William J. Flake which had been cleaned out to house the newcomers until they could build homes of their own. The Oakleys exchanged some of their cattle for a choice lot and a one-room log house in the northeastern part of the townsite.

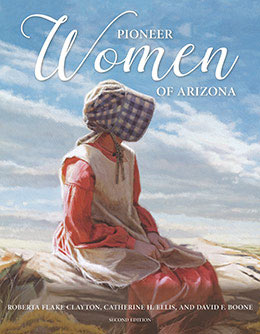

Louisa Jones Oakley and unidentified child. Photo courtesy of Roma Lee Hiatt.

Louisa Jones Oakley and unidentified child. Photo courtesy of Roma Lee Hiatt.

In writing of the journey to Arizona, Mrs. Vilate Oakley Pearce, then eleven years of age, says,

I well remember when we came to the Colorado River, it was running very high. The men had a hard time to keep the animals in the boat. Some of the cattle jumped overboard and the stream took them down so far it was hard for them to find a landing place on the other side. How happy we children were to see them safe.

Two Indians attempted to swim the swollen stream and one of them was drowned. I fancy I can hear the moaning and wailing of the family and friends. They killed his horse and shoved it into the seething water, along with his personal belongings and enough food to last the Indian to the “Happy Hunting Ground.”

After they crossed the river, the worst was yet to come, the dangerous dugway over “Lee’s Backbone.” It was Vilate’s task to lead her blind father every step of the way over it and again we take her version of it. “I remember clinging to the side of the road where the cliffs were hung, the mad river below. How my heart beat with fear at the sound of that wild rushing torrent, many, many feet below.”

The hardships of that journey were augmented by the fact that two of the three men making it were practically unable to assist. So to the girls was added the responsibility to assist with camp duties, gathering scanty fuel to prepare the meals. It was an experience, too, for Louisa, who left a very devoted lover in England when she joined the Mormons and came to America.[5] He was a man of means and offered her every comfort if she would renounce her religion and remain with him, but if she ever regretted her choice, no one ever knew it, although her lot was exceptionally hard.

Because of the blindness of her husband, and the childish mind of her poor brother, she had to plan and assist with all the labor necessary to making a new home. The work was too hard for her and for many years she was an invalid. Always cheerful in spite of her affliction it was a joy to do for her, and for years the women of the town took turns sending her a warm dinner each day.[6]

John was a man of refinement and education, and was not idle. He loved trees, plants, and flowers, and the demand for those things was great in this new community. So every cent of money he could get was sent to the East to get roots and cuttings for his little nursery. These were planted, tenderly nourished, and supplied the town with fruit trees, grapevines, berries, and beautiful roses, shade trees, etc. So although he could not enjoy the beauty he helped create, the appreciation of his service by those who could was recompense to him.

The daughters assisted him in his work in the nursery and gardens, and went out to work in the homes of the townspeople as soon as they could be spared from home, and so the family fared as well, financially, as their neighbors. All were good workers and their services much in demand.

Although herself a sufferer for many years, Louisa lived twenty-five years longer than her husband who was blind the last seventeen years of his life. He died May 5, 1890.

Her daughters married and had homes of their own near her, so that they continued to be a help and comfort to her. In 1900, Louisa and her brother, Robert Jones, were living in Snowflake with her daughter Sarah Willis.[7]

Naturally a public-spirited woman, as soon as she was sufficiently recovered from her illness, Louisa would enter into the life and duties of her church organizations as teacher in the Sunday School or Primary and other duties until she overtaxed her strength and would be bedfast again. Death brought relief to her in March 1915.

Ellis and Boone:

Because this sketch contains almost no information about John and Louisa Oakley before they came to Arizona, additional information is needed to understand their lives. First, John DeGroot Oakley, his parents, sister, wife, and daughter first came to Utah in 1847 as part of the Edward Hunter/

Second, the Jones family—William (age 45), wife Mary Ann (49), Robert (21), Louisa (19), and Frederick (14)—also left England on the S. Curling in 1856. However, they were part of the William B. Hodgetts wagon company of 1856 which accompanied the ill-fated Martin and Willie Handcart Companies.[10] Louisa’s father was one of the many who died en route, but his death date is questionable (see note at MPOT). When Joseph A. Young reported on the rescue mission, he said,

Brother Garr and I went back to where E. Martin’s camp had been. They had rolled out and Captain Hodgett’s wagon company were just starting.

We continued on, overtaking the hand-cart company ascending a long, muddy hill. A condition of distress here met my eyes that I never saw before or since. The train was strung out for 3 or 4 miles. There were old men pulling and tugging their carts, sometimes loaded with a sick wife or children – women pulling along sick husbands – little children six to eight years old struggling through the mud and snow. As night came on the mud would freeze on their clothes and feet. There were two of us and hundreds needing help. What could we do? We gathered on to some of the most helpless and helped as many as we could into camp on Avenue hill.[11]

As Joseph Young said, the rescuers helped as much as they could, but still many died as they struggled toward Utah. The last of the handcart and wagon companies arrived in Utah in mid-December.

Then, in February 1857, John Oakley and Louisa Jones married. The Oakleys at first lived in Salt Lake City (the 1860 census lists John Oakley, age 40, and Louisa, age 23); they were in St. George by 1862 and in Kanab by 1873.[12] While living in St. George, three of their children died; although the cemetery location is available, there are no markers for their graves. By 1880, the family was on their way to Arizona.

While living in Snowflake, John and Louisa Oakley were visited by Catharine Cottam Romney of St. Johns. Romney then wrote a letter to her mother, Caroline Cottam, telling more about the deaths of Louisa’s children and the part that Caroline Cottam played. Romney said that Louisa “inquired about you, and asked me to tell you when i wrote that she should never forget your kindness to her when her children died and shall ever feel grateful. she says she had nothing but an old muslin dress to bury her baby in and she thought that wouldn’t do, but Mother said, ‘it will do very well Sr Oakley. I will take it and do it up for you.’ And she says when mother brought it back, it looked beautiful just as nice as if it had just come out of the store.”[13]

Esther Meleta Johnson Openshaw

Author Unknown

Maiden Name: Esther Meleta Johnson

Birth: September 26, 1847; Bonaparte, Van Buren Co., Iowa

Parents: Benjamin Franklin Johnson and Melissa Bloomfield LeBaron

Marriage: Samuel Openshaw;[14] December 25, 1863

Children: Benjamin Samuel (1864), David Arthur (1866), Meleta Ann (1868), William Franklin (1869), Eli Carlos (1872), Esther Melissa (1874), Joseph Almond (1878), Mary Julia (1879), Delcena Vilate (1880), Lavina Ann (1882), Brigham Nelson (1885), Rose Adena (1888)

Death: April 26, 1926; Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Esther Meleta Johnson was born in a covered wagon en route to Utah, September 26, 1847, daughter of Benjamin Franklin Johnson and Melissa Bloomfield LeBaron. She was fourth in a family of eight children, two dying in infancy. Benjamin F. was a commanding figure of a man who accumulated worldly goods readily for his family needs; [he was] a close friend, secretary, and business executive to the Prophet Joseph Smith. Melissa was the first of his seven wives. The Johnson mansion in Spring Lake, Utah, was a rambling house surrounded by vegetable gardens and fruit trees. Here Esther spent her childhood, and here her mother died when Esther was thirteen.

On Christmas Day 1863, Esther became the bride of an English convert thirteen years her senior, Samuel Openshaw. They made their first home in Santaquin, Utah, where their first two children were born. Eight other children were born (two dying in infancy) during the years filled with farming, school teaching, and church work before the family moved to Arizona in 1883. Here two more children were born completing the family.

Settling in Tempe, Arizona, Samuel served as bishop of the Tempe Ward; moving to Nephi (five miles away), he served as the bishop of Nephi Ward until he died.[15] Meanwhile Esther served as Ward Relief Society president for eleven years. The sizeable family filled Esther’s years with delights and joys, underscored with occasional soul testing moments of tragedy. In 1872, Samuel asked and received Esther’s permission to bring a second wife into their family, Elizabeth Spainhower, and Esther declared that some of the happiest times of her life were spent in Elizabeth’s company.[16]

Esther spent much time in prayer: the gospel, Bible, and other church works were solace in time of trouble, sustenance for every day’s service and love. Beloved by her neighbors, “Aunt Esther” must be at the bedside of birth, and she never failed a call. A cultured woman, the perfection of her grooming and the pride of her bearing blessed the homes of those she served. Large of body and of heart, deeply hospitable, she delighted in feeding her guests, in sharing and serving.

Esther enjoyed out-of-door life, camping in the mountains, cooking in the open, “all kinds of weather but [not] too much sunshine.” She told her children of gathering brush to tie into a broom with which she swept dirt floors, in the early Utah days. She spoke of a time when an old Indian, Guthic, risked his life to warn her people of a pending Indian raid and her mother bundled the children in bed fully dressed, not even removing their shoes.[17] Perhaps growing up with the two Indian children adopted by her father to save their lives, made the Lamanites less alarming to Esther, for she did not hesitate to push a drunken Indian, disturbing her child, out of the crate of drying peach halves and drive him away with her enraged mock stick attack.

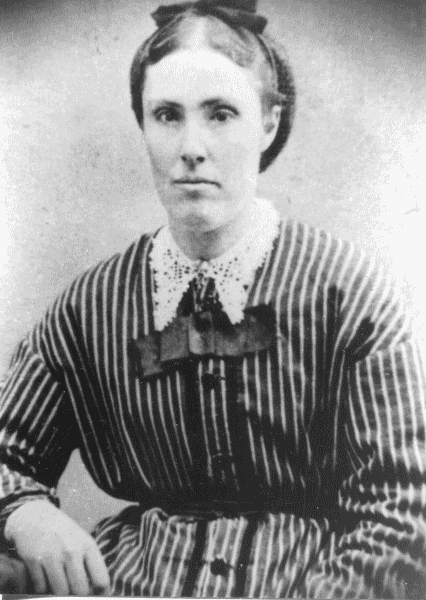

Esther Meleta Johnson Openshaw. Photo courtesy of International Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

Esther Meleta Johnson Openshaw. Photo courtesy of International Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

Esther Meleta Johnson Openshaw. Photo courtesy of Ancestry.

Esther Meleta Johnson Openshaw. Photo courtesy of Ancestry.

After Samuel’s death on January 2, 1904, Esther stayed on the farm six years, but the loneliness was too much to bear. She sold the farmland, built a cozy little home three miles east of Mesa, and settled there in 1910. In 1918 her health failed but revived again during a three-month trip to San Diego, California. On June 7, 1921, Esther was stricken with paralysis of the left side, and lay for a week in a state of coma, rallying to survive five more years.[18] A fall fractured her hip, and three weeks later she died on April 25, 1926.

At the time of Esther Johnson Openshaw’s death, her posterity numbered almost fifty. A glorious woman, one not easily vanquished by “the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,” a pioneer dependable and faithful as the soil—she fulfilled her patriarchal blessing: “None of all thy father’s house shall excel thee. . . . Thou shalt be enabled to raise up a righteous posterity and they shall become numerous upon the earth, and thy sons shall assist in building the Zion of the Lord and shall dwell in the Holy Sanctuary when the Lord shall bring again Zion and thy daughters shall be crowned with the daughters of Zion.”[19]

Ellis and Boone:

Today, with the huge metropolis that the Salt River Valley has become, it is hard to envision a distinct community of Nephi. As noted here, the Openshaws (and LeBaron and B. F. Johnson families of which they were a part) first settled in the area of present-day Tempe. When the Maricopa Stake was first organized in 1882, these members were organized into a Tempe Branch, along with the Jonesville (Lehi) and Mesa Wards. The Tempe Branch was changed to a ward in 1884 and then discontinued in 1887 when the Johnsons and their relatives moved further south, just west of today’s Dobson Road. For a short time, these families were part of the Alma (Stringtown) Ward, but in 1888, a separate Nephi Ward was created for them. When Andrew Jenson of the Church Historian’s Office visited Arizona in 1894, he gave these population figures for the various wards: Mesa, 637; Lehi, 193; Papago, 590 (with another 629 Indians on the reservation further south); Alma, 261; and Nephi, 110. These figures, and the close proximity of the Alma and Nephi Wards (Alma School and Dobson Roads, respectively), help us understand the eventual dissolution of the Nephi Ward about 1904; Samuel Openshaw was the one and only bishop of the original Tempe and later Nephi Wards.[20]

With the ease of modern transportation, it is also hard to envision the loneliness that Esther Openshaw felt living in the Nephi area after her husband’s death. To understand, one must picture the process of hitching the horse to a buggy or cart for the five- or six-mile ride from Nephi to Mesa or Lehi and add Esther’s age (she was about sixty years old) and the fact that she was a large woman. Isolation has always been difficult for Mormon women, particularly ones who have been used to being in the center of all activities whether through being the bishop’s wife or the Relief Society president for eleven years.

Finally, in 1974, Esther’s youngest daughter, Rose, wrote a brief sketch of her parents, probably in response to a request from Earl Merrill, giving this tribute to her mother. She wrote that her mother “presided as Relief Society president in Nephi, and whenever babies were born, she always went to take care of them and their mothers. She loved to give, and tho we were poor as ‘Job’s turkey,’ she always shared with those still less fortunate. She was too, exceedingly hospitable, and no matter what time visitors came, she always insisted on preparing them a meal. This used to irk us lazy girls, for dish washing wasn’t one of our favorite pastimes. But as I look back upon it now, her unerring kindness and thoughtfulness of everyone seems a most beautiful and God-given trait.”[21]

Ethelinda Hall Murray Osborn

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP[22]

Maiden Name: Ethelinda Hall Murray

Birth: April 5, 1857; Burleson Co., Texas

Parents: William Pinkney Murray and Margaret Elizabeth White (or Buck)

Marriage: William Lewis Osborn; January 24, 1873

Children: William J. (1873), Maude Evangeline (1875), Pauline E. (1877), Regina Gertrude (1878), Winfield S. (1880), Estelle (1883), Hazel (1886), June (1888), Myrtle (1893), Harry (1895)[23]

Death: January 9, 1947; Phoenix, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Greenwood Cemetery, Phoenix, Maricopa Co., Arizona

In a comfortable, vine-covered brick home in a quiet residential part of Phoenix lives a charming little old lady, old as years go, but with the mentality and alertness of a person many years younger. This smiling, gracious pioneer woman is Ethelinda Murray Osborn.[24]

Her parents William P. and Margaret White Murray were living in Burleson County, Texas, when on April 5, 1857, Ethelinda was born. She was one of seven children.[25] They were not long privileged to enjoy the love and devotion of their mother, as she passed away when the children were small.

In the month of May 1870, her father brought his family west en route to California. They were driving oxen and had a large herd of loose cattle. The trip was hard on the stock because of scarcity of grass and water. Whenever both of these necessities were found in the same locality, many days or even weeks were spent there until the supply was exhausted hence it was December before the company reached Maricopa.[26]

Mr. Murray heard of the possibilities of the valley of the Salt River, so leaving his outfit there, he came on. He was so delighted with what he found that he let the company go on to California without him.

Ethelinda’s father did not live long to enjoy his new home, but the following May he passed away leaving his smaller children in the care of a married daughter and older members of the family.[27]

Ethelinda Hall Murray Osborn with three granddaughters, 1927; baby Harriet, Joyce (left) and Adele Osborn (daughters of Harry). Photo courtesy of Inez Heinemann.

Ethelinda Hall Murray Osborn with three granddaughters, 1927; baby Harriet, Joyce (left) and Adele Osborn (daughters of Harry). Photo courtesy of Inez Heinemann.

When the Murrays arrived, there was only one little store and only a few houses. The valley was covered with large mesquite trees and paloverdes. This had to be cleared off and the ground leveled off for farming. Raiding Apache bands robbed the family of most all of their cattle. Land could be preempted and farmed. The Murray boys were hard workers, and it was not long before they began to prosper.[28]

The distance from sawmills prevented the use of lumber for homes. The houses were built of adobe, the roof of ocotillo and palm stems covered with grass then a layer of dirt, which made them passably cool in summer. The floors were also of dirt. They were wet and patted down until they were almost as hard as the cement floors now so fashionable.

Everything that could not be produced here had to be freighted in from California. Screens for the windows and doors were unknown. The flies were terrible, as were the centipedes, scorpions, and tarantulas. Kind Providence must have favored the pioneers because there were few or no fatalities among them from poisonous insects.

The schoolhouse was a little one-room building where all the pupils sat on split-log benches with peg legs to hold them up. There was the long “recitation bench” where, at the tap of the little desk bell, the next class was seated. If it were reading, then each one opened the book and in rotation read the lesson verse by verse, or sometimes the teacher played a trick by skipping around. That was an unfair advantage because it did not give you a chance to figure out which would be your paragraph and study it while the ones ahead of you read theirs aloud.

If the lesson was grammar or arithmetic, then there was the blackboard where you might be called upon at any time to get up and diagram a sentence or work an example in long division. Then there were the spelling lessons where you had to go down one every time you missed a word until finally you found yourself at the foot of the class, or if you were a good speller you might work yourself up to the head. You could only stay there three days in succession, then you would have to go to the foot and how you studied to get to the top again! The spelling bees were looked forward to with pleasure by good scholars as it gave them a chance to show off. Friday afternoons were red letter occasions because then there were songs, recitations, and sometimes even a playlet or farce.

School days were pleasant ones for Ethelinda. Her keen sense of humor, inherited from the Whites of Ireland, has stood her in very good stead during the trying days of pioneering, and, from her thrifty Scotch ancestors, she has made the most of whatever has come into her hands—not using it selfishly but sharing it with those who need help.

Whether it was because she had no home or mother, because she was so attractive, or because she and young William Osborn were so much in love, Ethelinda and he were married before she was seventeen—the wedding took place January 24, 1873. She says, “After two weeks of playing around, we settled down to enjoying married life and its responsibility,” and for fifty-four years that pleasure was theirs.

Ten children came to bless their union, and unusual as it is, they all lived to be grown and have families. In fact, all are still alive with the exception of one who passed away December 1938.[29]

William Osborn died in Phoenix on July 1, 1927.[30] Their Golden Wedding, celebrated in 1923, was beautifully and fittingly celebrated by this congenial couple. Always William was an excellent provider and made adequate provision for his beloved companion after his death.

Ethelinda gloried in her independence. She took orders from no one. Her hospitable home was open to her family, her many friends, and her acquaintances, but she reigned as its queen.

Though she is past eighty-two years of age, she still actively goes about her household duties. Her vision is as clear, her hearing as keen, and her intellect as bright as ever. She attributes her ability to go about her tasks to never letting down. One of her pastimes is the working of crossword puzzles, and they seldom get too hard for her. Many times her grandchildren come to her to get her to tell them what the words are, and they are proud to think their grandmother is so smart.

Mrs. Ethelinda Osborn is one of the few remaining pioneers who came into the territory in the early 1870s. It is a real joy to visit her; she is so wholesome and understanding. The trials of early days taught her to bear stoically whatever comes. Because there were no doctors for miles around in those early days, she did not look upon childbirth as a condition to be dreaded. She always had faith that everything would be all right. When sickness came to her children, she mixed common sense with herbs, roots, and simple remedies for their care and was successful in raising a family of strong healthy boys and girls.

Her philosophy of life is most refreshing. It can truly be said of her that she has grown old gracefully, and Henry Giles says it should be—

“The day of life spent in honest and benevolent labor comes in hope to an evening calm and lovely; and though the sun declines, the shadows that he leaves behind are only to curtain the spirit unto rest.”[31]

She died at the age of eighty-nine, January 9, 1947.[32]

Ellis and Boone:

William Murray brought his family to Arizona just a few years after settlement began at a site along the Salt River which later became Phoenix. In December 1867, Jack Swilling formed the Swilling Irrigating and Canal Company, began enlarging the Hohokam canals, and planted crops to sell to the army. Recognizing the symbolism of old canals and new, the town was named Phoenix after the bird that sprang from its own ashes. By 1870 when the Murrays arrived, Phoenix was a small agricultural community which needed governance. John T. Alsap, a lawyer who had earlier lived in Prescott, organized a committee to decide on a townsite, supervised the surveying of lots, arranged title to the land, and became an ardent booster in every way. He was elected the first mayor of Phoenix and became the Maricopa County Probate Judge.[33] He was also single.

Marilla Murray Osborn. Photo courtesy of Arizona State Libraries, Archives, and Public records, 97-7804.

Marilla Murray Osborn. Photo courtesy of Arizona State Libraries, Archives, and Public records, 97-7804.

Ethelinda Murray Osborn had a younger sister, Marilla, who married Neri Osborn in 1882. Author Margaret Finnerty wrote, “Marilla Murray was one of eight sisters newly arrived from Texas. Almost every year for the next decade a Murray sister married a local man, adding considerably to the family life in the frontier community.”[34] Mary married John A. Chenowith in 1871, Matilda married George Buck in 1872, Ethelinda married William Lewis Osborn in 1873, Anna married John T. Alsop in 1875, Flora married Roland Lee Rosson in 1880, and Marilla married Neri Osborn in 1882.[35] With the death of William Murray, the 1880 census shows the younger children living with married siblings; Flora is living with Anna Alsap; Rilla and Eula are living with Mary Chenoweth. Apparently, Eula had been living with Matilda Buck, but by 1880 Matilda had died and George Buck had remarried.[36]

The Murray, Osborn, and Alsap families illustrate the importance of Freemasonry in early Arizona history. John T. Alsap was Master of the Aztlan Lodge when it was organized in Prescott under the auspices of the Grand Lodge of California in 1865. In 1879, he organized the Arizona Lodge in Phoenix. He was part of the convention in 1882 which created a Grand Lodge in Arizona severing ties to California and New Mexico, and he served as the second Grand Master. The list of Masons who were important businessmen and government officials is massive, including Governors George W. P. Hunt and John N. Goodwin, Senators Ralph Cameron and Carl Hayden, Andrew E. Douglass, and Morris Goldwater, to name only a few.[37] In this tradition, Marilla and Neri’s son, Sidney P. Osborn, was governor of Arizona from 1941 to 1948. Because both the Osborn and Murray families came to Arizona so early, Governor Osborn was not only a native son but intimately acquainted with all aspects of the history of Arizona.[38] Reportedly he said, “Only death or the people of Arizona will remove me from office,” and, Margaret Finnerty wrote, “The people never did.”[39]

Lucretia Proctor Robison Owens

Lenora Owens Skillman

Maiden Name: Lucretia Proctor Robison

Birth: May 18, 1841; Schroeppel, Oswego Co., New York

Parents: Joseph Robison Jr. and Lucretia Hancock

Marriage: James Clark Owens II;[40] January 16, 1856

Children: James Clark Owens III (1857),[41] Marion Alfred (1860), Lucretia Adelpha (1862), Clarence Edward (1865), Elsie Abigail (1867), Joseph Alonzo (1869), Mary Amelia (1871), John (1874), Lillis Alvira (1876), Zina (1878), Franklin Horace (1881), Adelia (1883)

Death: May 24, 1929; Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona

Burial: Woodruff, Navajo Co., Arizona

My earliest memory of Grandmother Lucretia Owens was when I was four or five years old and we lived on the opposite corner of the block in Woodruff, Arizona.[42] We loved to go to her house and would cut through the lot, past the orchard, the garden, and other things that held great interest for my brother Vivian and me. For instance, there was the big old high wagon that was permanently parked under the big pear tree. This was our favorite play spot. We would mount the high seat and imagine it was a big cavalry wagon with fine teams hitched to it, and we were hauling supplies to the soldiers somewhere. We spent hours there. Then there was the cellar, which had a pitched, dirt-covered roof, where roots from the garden and apples from the orchard were stored for the winter. It seems like Grandmother could find an apple for us there almost any season of the year. Then there was Grandfather’s blacksmith shop with its big bellows, the old anvil, huge hammers we could hardly lift, etc., which were so interesting and it was so much fun to pull the handles of the big bellows and feel the breeze that kept Grandfather’s coals glowing hot when he used it. Finally, we would reach the back porch of the always neat and inviting home and inside the kitchen door Grandmother always made us very welcome.

Grandmother was a quiet, slender, very neat, dignified, and sweet little woman. As I think back, I spent quite a lot of time with her, and she tried to teach me many things I should know by repeating often sayings such as: “Beauty is only skin deep,” “Beauty is as beauty does,” or “Birds of a feather flock together,” and other similar phrases, but all through my life I have remembered them, and they have been good advice when I needed it.

Lucretia Owens was born May 18, 1841, in Schroeple, Oswego County, New York. She was the daughter of Joseph Robison Jr. and Lucretia Hancock and was christened Lucretia Proctor Robison, the Proctor being her grandmother’s maiden name. She was the eighth child in a family of thirteen. There were nine boys and four girls.

Lucretia Proctor Robison Owens. Photo courtesy of Morjorie Lupher Collection.

Lucretia Proctor Robison Owens. Photo courtesy of Morjorie Lupher Collection.

Lucretia’s parents became members of the Mormon Church in February 1841, three months before she was born. They started to go to Nauvoo, but it was very rainy and muddy when they got to Crete, Will County, Illinois, so the family stopped. They rented a house and were waiting for the teams to rest and the weather to moderate, when some Mormon elders came and stopped with them. These men told them the Prophet Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum had been killed and that it was advisable for them to stay away from Nauvoo until the trouble was settled.[43] Joseph Robison bought 160 acres of government land and made a home there for his family. This place was only thirty miles from Chicago, and during the ten years they lived in this place, they prospered and accumulated livestock—horses, cattle, sheep, hogs, etc., for which there was a ready market in Chicago.

Joseph Robison’s wife, Lucretia, especially, was still anxious to gather with the Saints in Zion, so with a feeling of reluctance on the part of most of the family, after ten years, they disposed of their property in Crete and started for Utah. The oldest son, Alfred, did not convert to Mormonism and refused to go west, so it was with sadness in their hearts they left him alone in Illinois.

Lucretia Owens wrote about the trip as follows:

Left Crete April 12, 1854. Started for Utah across the plains with fourteen in family. With three ox teams and one horse team. We had no trouble in any way. No sickness or Indian trouble. Perigren Sessions was captain. We had fourteen wagons in the Company. There was no loss of cattle or teams. The Company laid over Sundays and generally held meetings. We arrived in Salt Lake City October 5, 1854, all well. We camped southeast of city. Father, Mother, and brothers went into the city and paid tithing. President Young told Father to go settle in Fillmore, one hundred and fifty miles south. Father moved into Fillmore. The people were living in a fort, as the Indians were on the war path. Father bought a home, also bought wheat and built a granary.

Soon after the Robisons settled in Fillmore, they contracted with James Clark Owens II to build a rock house for them. Lucretia Proctor Robison and James Clark Owens II met at this time, and they were married January 16, 1856, by President Brigham Young. Lucretia was at that time just under fifteen years old and James was twenty-three years old.

Earlier, when James Owens II was fourteen years old, his father was frozen to death during a blizzard.[44] At that time the family was at Mt. Pisgah, Iowa, and from then on James had the responsibility of caring for his widowed mother. Just prior to crossing the plains, his sister Julia’s husband, James Amacy Lowder, died and left her with two small daughters, and these three were then added to James’s family. While crossing the plains, James’s sister Caroline Amelia’s husband, Edward Milo Webb, died and left her with two young sons, and James helped with the support of this family also. Lucretia willingly joined this family when she married James, and she was loved and respected by all of them.[45]

Lucretia’s first child, James Clark Owens III, was born January 14, 1857, and during the latter part of February of this same year, James received a call from President Young to report in Salt Lake City prepared to go to the mountain to cut stone for the temple. James and Lucretia arrived in Salt Lake City in time for the April Conference and at that time received their endowments.

Following conference, they were sent out twelve miles to the mouth of Little Cottonwood Canyon, where the beautiful granite used in the construction of the temple is located. They made a camp and lived there while James cut stone that summer. At first they lived in tents, but later some slab houses were put up and some sheds were constructed to cut stone under.

Times were very hard. The only remuneration received was daily sustenance from the tithing paid in by the Saints in the Cottonwood Ward and delivered to them by Bishop Holladay. Sometimes there was hardly enough for the laborers to eat. However, they felt they were there to do their bit in furthering God’s work and were willing to make any sacrifice necessary.

Cutting stone was very hard on clothing, and Lucretia saw to it that James’s clothes were always kept clean and mended. There was patch upon patch, if necessary. I remember as I grew up, Grandmother always said: “Patches are honorable, if the clothing patched is clean.” A worn garment was never destroyed. When it was past wearing, it was used for patches, for cleaning cloths, or for rug rags. James wore leather or buckskin aprons to save his clothing from unnecessary wear. He also wore leather gauntlets on his forearms, and instead of gloves, leather pads were used which fit over the palm of his hand and were held in place by narrow strips cut to fit over the third finger and thumb.

James and Lucretia were at this camp all summer. They joined with all of the people of the valley in celebrating the 24th of July in the canyon eighteen miles above the city. Everyone was having a good time when two horsemen arrived and told President Young that Johnston’s Army was approaching. The stonecutters, along with all other men, were called to go as guards to Salt Lake City, but they were released to go back to cut stone when they found there were enough men for guards without them. They were told to be ready at a moment’s notice should they be needed. There were twelve men working as stone cutters, and they continued to work at the quarry until winter snows began. They were released to return to their homes, seven months after they began this work.

James was called other times to cut stones for the various temples; the sum of the time spent at this work adds up to more than four full years. He cut the stone used in arches and winding stairs of the Salt Lake Temple, the St. George Temple, and Manti Temple. During all the time James was away from home, Lucretia remained at home with her growing family and doing her part cheerfully. Lucretia bore ten children during a period of twenty-one years while they lived in Fillmore and two more children after they moved to Arizona. She lost four small children while they were in Fillmore.

James’s mother, Cordelia Burr Owens, lived with them almost eleven years after they were married. Their son, Franklin Horace, says: “[Cordelia] loved [Lucretia] because of her kind and submissive disposition, her neatness and aptitude in the home, as well as her religious duties. The two worked together—washing, carding, and spinning wool into threads.”[46] He further stated that—“during resting periods and in the evenings, they would sit for hours knitting stockings, mittens, jackets, and even headgear, ear-muffs, etc., for the cold winter weather.” Franklin also says his mother “was never idle, neither did she ever attempt to dictate to her husband, but was always cooperative. Of them I can truthfully say, I never remember hearing a cross word spoken between them, one to the other.”

Lucretia in her writings says: “Father [apparently meaning James Clark Owens II] joined the United Order in Fillmore sometime during the year 1870, and later he was called back again to cut stone for the Salt Lake Temple. He was cutting the stone for the arches for the winding stairs. He lived with President Young’s family.”

Lucretia Owens also wrote that she and James were at the dedication of the St. George Temple on April 6, 1877, and that they did some work in the temple. They had all of their children with them except their oldest son, and at that time they had these children sealed to them.

It was just twenty years prior to this time that James and Lucretia attended the April conference in Salt Lake City and, in the Endowment House, received an early blessing and were assigned the duty of opening up the rock quarry at the mouth of Little Cottonwood Canyon in April of 1857. Lucretia, in writing about the dedication of the St. George Temple and the work they did in the temple at that time, says that she and James “went through the temple for their second endowments, and as for the children all ordinances necessary, including sealings, baptisms, etc., were attended to.”

Lucretia writes further: “That summer, 1877, he (James) was called to Salt Lake City again to work on the temple.” It was during this period that he was given the assignment to move to Arizona to assist in developing that state.

This call was almost stunning to Lucretia. It was very hard to leave their little home in Fillmore, their friends, family, and familiar surroundings, and move to an undeveloped country. However, the call was from the Church Authorities, and without hesitation she agreed to accept the call with her husband. Their son, Franklin Horace Owens, writes of this period: “Their two oldest sons were young men—Clark in his twentieth year and Marion eighteen, and they had become a great help in the support of the family. They did their part toward the accumulation and care of livestock and other properties, thus aiding in many ways in building up and maintaining a happy home. Since for a long period now Father had been almost steadily employed cutting stone for the temples, Mother, and the boys under her direction, ‘Kept the Home Fires Burning.’”

Several families of Saints were scheduled to move to Arizona in late October or early November 1878. It was with this company James and Lucretia were directed to travel. The hardships of this trip from Utah into Arizona are familiar to all who had parents and grandparents who were pioneers into this area. We know of the very poor roads, of the hazardous crossing of the Colorado River, of the long stretches between water, with little grass for the animals, etc., therefore, I will not dwell upon this story.

After seven long weeks of wearisome travel, the family arrived, on Christmas Day 1878 at what is now Show Low, Arizona. It was a great relief to reach their destination. Lucretia had a five-month old baby when they arrived in Show Low, and in her writings she merely states: “We pitched our tent and spent the winter in it and the wagon beds.” She says further: “They (meaning James and her sons) put up a log house. We only lived in it a short time, then moved to Bush Valley, now Alpine. James planted a crop and built a house of hewed logs. The frost killed the crop.” Lucretia, in telling of her experiences when they moved to Bush Valley, mentioned the beautiful mountains, the various trees, the valleys covered with beautiful tall grass, etc. The Indians were treacherous and cunning and made several raids and drove off stock grazing in the open meadows. In this way many of the horses belonging to the settlers were driven off and never recovered. Only teams that were closely guarded or kept on the roads were saved. Evidently James Owens presided over the Bush Valley Ward, as Jesse N. Smith says in his history: “James Clark Owens had charge of the Bush Valley Ward, and at the September Stake Conference in Snowflake he gave a report of existing conditions.”[47] It was during this Conference, or soon after, that James was called to move to Woodruff to build a dam in the river. There had already been attempts made to dam the river but the floods would come and wash the dams out.

Lucretia, in telling about this call to go to Woodruff, said that James had just completed a nice little house of hewed logs and that she was very happy and contented in it; that it was very hard to give it up and again move to a place where they would have to start all over again. However, they had never refused a call from the Church Authorities, and when Elder Wilford Woodruff asked them to go to Woodruff, they did not hesitate, but disposed of the new house as best they could and moved again. They arrived in Woodruff December 4, 1879, again in the cold wintry months.

Grandmother was always an immaculate housekeeper, and I can imagine how she must have felt when she first looked into the dingy one room in the old adobe fort where they were supposed to live. In describing it, she says the walls were unplastered adobe, the floor was dirt, poles of cedar were laid across from wall to wall, and then willows from the river were laid across them. Then on top of the willows was a mound of earth, and this made the roof and ceiling of this room. There was an opening for a door, and another small and rather high opening for a window, and several port holes in the outside walls. There was no glass in the window and no door to open or shut. In short it was a very primitive shelter, and I know it was with a heavy heart that she set about making it into a home for her family of eight—six children, three boys ages fourteen, nineteen, and twenty-two years, and three girls ages one, eight, and twelve years. They used the wagon boxes as bedrooms for the boys and for storing certain things like the loom, the spinning wheel, and certain other things that would be saved until they could have a home again.

In one room, they made a partition by hanging a piece of old carpet and a blanket on a rope stretched across the room; in this way they had a bedroom and a kitchen-living room. Their son, Franklin, describes the furnishings of these rooms as follows: “two rudely fashioned clothes cupboards hung against the walls above the beds. One little cupboard rested on some flat rocks several inches off the floor, and this also served as a dressing table, in the corner by Mother’s bed. Crosswise at the foot of her bed was a bed for the smaller children. This filled the back room. In the kitchen, or front room, was another bed, a table, a small cast iron cook stove, some rough cupboards, and a chair or two, which were part of a set of beautiful and well-designed kitchen chairs, including a most comfortable rocker.”

James made these chairs. The seats were of leather thongs woven back and forth, and they were neat, solid, and comfortable. I remember them well, as Grandmother used them as long as she lived.

I have heard Grandmother, and also my father [Franklin Horace], tell about conditions in the old fort during the rainy season. It didn’t take much rain to soak the sod roof and when it was soaked, it began to drip muddy water and just plain mud. What disheartening dreary days they had during rainy weather.

Franklin was born in this old fort, and young as he was when they finally moved into a house of their own, he can remember one particular rainy day. Of this he writes:

It was during the summer rainy season, and it had rained each day for several days thoroughly saturating the earth. Then after a hot forenoon, it began to rain again, this time in real earnest. Mother from experience knew what might happen and began piling her clean clothes and other things on the beds, then covered them with quilts. Then she put out every container she had out to catch the already falling drips of muddy water. The drops became almost streams of mud and water until the floor was a slush almost shoe top deep. Everything in the house was soaked. To keep me as dry as possible, Mother put a doubled quilt around me and stood me in the doorway, which partially protected me, as the adobe walls were thick and made a partial shelter over me. The girls were in the wagon box, where it was dry, and the men were at the dam. Poor Mother, drenched through and through, not even a dry cloth to wipe her eyes, sat down on an old box and wept. When I saw Mother crying, I began to sob and cry, too. To quiet me, she carried me out through the mud and slush to the wagon where the girls were. The yard was virtually a lake of water. We had no fire and there was no dry wood, and no dry clothes to change into.

Finally, James was able to build a nice four-roomed house with a porch enclosed on three sides for his family, and what a happy day it was when they moved into this house. Lucretia was able to take the carpets, window curtains, etc. which had been stored so long in the wagons and begin to make the new house into a home. It was a very neat, comfortable, and happy home she made for her family. I remember this house, as Grandmother lived in it most of her later life.

Lucretia, of necessity all of her life, had to be thrifty and careful of everything she had. She saved every small thing. Nothing was ever wasted. Even the rinsings from the syrup pitcher went into the vinegar bottle to become vinegar. Every bit of fat was rendered and the grease saved to make soap. To make soap, it was necessary to have lye, and she made lye by leaching the ashes from the hearth. It took certain kinds of wood to make this ash, and both cottonwood and aspen wood left an ash from which the lye could be made. Franklin says: “Mother had three beautiful brass kettles, and in these she made her soap, and when properly cooked, she poured it into tubs to cool.”

Another thing Lucretia made was dye. She made very good fast colors, and her daughter, Adelia Owens Hatch, writes as follows:

She loved these varied activities which had to do with homemaking. She had a place for everything. As these skills improved with much use, she found new and varied methods, especially in the use of homemade dyes, etc., where she learned, in addition to the old indigo for blue and log-wood for a fast black, to use the blossoms from rabbit-bush for yellow and peach leaves for green. Her children found great sport in going to the mountain for madder to create a red dye which was achieved by using sour bran water set with ash lye, and taking copper, sometimes known as blue vitriol, with which to make all their color fast.[48]

I remember the old candle molds that Grandma had, and my father remembers how as a child he helped [his mother] string the wicks into these molds and then pour the tallow and bees wax into them to make the candles.

I have watched Grandmother carding wool, but this wool was used in making mattresses. Periodically the mattresses were taken apart, the wool washed, carded, and then retied inside the mattress cover.

Another thing I remember is the bed I always slept in whenever we visited Grandmother. It was a beautiful mahogany bed with beautifully turned spindles in the head and foot. Instead of springs it had rawhide thongs strung across it in a diagonal pattern. On top of this was a straw tick, and on top of the straw tick a feather bed. How I loved the softness and warmth of that feather bed! Each summer, Grandmother would spread a large canvas on the grass when the weather was warm and dry, then dump the feather beds on this canvas. She would cover the feathers with mosquito netting so they wouldn’t scatter, and several times a day she would stir the feathers so all would be well-sunned and aired. While the feathers aired, the cover was washed, then the feathers were put back. While the feathers aired, the straw ticks also came out and they were filled with new straw. How clean and wonderful everything smelled when her house cleaning was finished!

Another part of Lucretia’s house cleaning was taking up the rag carpets. If they needed washing, the strips were unsewn and washed, then resewn, ready to spread over the fresh new straw that had been spread on the floor for padding. Finally, the carpet was tacked and stretched tight over the straw.

The floor of her kitchen was made of fairly wide boards, and these boards were scrubbed with lye and hot water until they were white and beautiful.

The day always began at 4 a.m. for Lucretia. Even after there was no need to get up at that hour, she could not seem to break the lifetime habit. Breakfast by lamplight was the rule in her house. It was a big meal. While the men took care of the animals, Lucretia made hot biscuits, fried potatoes, and meat of some kind. It wasn’t always possible for the men to have a good lunch, so she made sure that the morning meal was substantial.

Woodruff, for years, was on the main road between Holbrook, Snowflake, and the other towns to the south. James was bishop of Woodruff for ten years or longer, and his home was always headquarters for people going through. Lucretia writes: “His home was a place for the traveler, friend or foe, to stop without money or price.” James was a stonemason, a blacksmith, and wheelwright, and more often than not, he gave his time and services free to the traveler in shoeing a horse or fixing their equipment. Their son, Franklin, says that many times it was necessary for Lucretia to set two tables to take care of her company. Their daughter, Adelia Hatch, has written: “When the Authorities would come from Salt Lake City to visit the wards or stakes, they would always stop at our place. Sometimes they would bring their wives and children. That would mean that we children would have to go to the home of one of our brothers to sleep so as to make room for the company.”

During the early days in Woodruff, the people were very poor and sometimes they were thankful to have only bread to eat. When there was fresh milk to go with the bread, it seemed like a feast. Later, when the railroad came into Holbrook, it was easier to get food. Until the railroad came, supplies had to be brought in by team and wagon from Albuquerque, New Mexico, two hundred fifty miles away.

I remember one spot in Grandmother’s garden where she grew her herbs. There was yarrow, golden seal, saffron, tansy, pennyroyal, and many other herbs that she used to make teas, canker medicine, spring tonics, etc. for Mother [Lucy Eagar Owens] and the neighbors. Lucretia, through the years, had been a ministering angel to anyone in the little town who needed her services, and she would go any time night or day when her help was needed. Adelia says she was an excellent nurse.

In 1893, James and Lucretia moved back to Fillmore and remained there four years. These four years were wonderful years for Dad [Franklin], who was then in his teens, but I don’t remember hearing Grandmother say much about them. Apparently Woodruff had become home to them, as they moved back in the fall of 1897.

Lucretia was always active in the Church. She served as president of the Primary, religion class, and Relief Society, and was a teacher in the Sunday School and in the other organizations for many years. She loved the Church and spent many hours reading the scriptures after her children were grown and she had less work to do.

James died suddenly February 1, 1901 and this was a great sorrow to Lucretia. We have copies of several poems she wrote expressing her loneliness and sorrow.

Besides losing James, her last three children married and left the home within a few months of each other. Zina married a short time before James died. Franklin and Lucy Eagar had planned to be married and were married on July 4, 1901, and Adelia married in October of 1901. This left Lucretia alone in the home where she had worked so hard and taken care of her family and so many others through the years. Lucretia enjoyed being busy, so it was hard for her to adjust to the lonely life without the house full of people needing her help.

All of her children left Woodruff within a few years after they married, so finally Clarence built a nice little home for her in Snowflake on a lot adjoining his home, and there she lived until she died May 24, 1929.

Ellis and Boone:

James and Lucretia Owens made significant contributions to the community of Woodruff. In the copy of this sketch at the Mesa FHL, Skillman also included this paragraph to describe her grandmother’s personality: “I lived with her one winter and went to school in Snowflake. She loved to talk about her life and the gospel. The well-worn Bible and Book of Mormon were always on the kitchen table, and she would sit beside this table reading from these books, thinking and writing some, for hours at a time.” A 1925 letter from Bishop Levi M. Savage (which reads like a patriarchal blessing) was also included in that sketch.[49]

During the pioneer period when converts to the Church were gathering to Zion, family members were sometimes left behind, as was Alfred Robison.[50] The denouement of this incident is both ideal and bittersweet. Descendant Brenda Johnson wrote:

Lucretia Hancock Robison died in 1899; Alfred died in 1892. Seven years after Lucretia’s death, the old post office in Fillmore, Utah, was moved. When they took out the cabinets, they found several letters which had fallen in between, one of which was to Lucretia Robison from her son Alfred. In the letter, Alfred wrote that if his mother would forgive and forget the bitter, unkind things he had said when they parted, and if she would enjoy a visit from him, nothing would please him more or make him happier. No doubt Alfred wondered why his mother failed to answer his letter. A distant relative, who visited Fillmore a short time after Alfred died, told Lucretia that the Friday night before Alfred died on Sunday, he talked of his mother all night.[51]

Notes

[1] Some of the information for this sketch came from Louisa’s daughter, Vilate Oakley Pearce.

[2] Ellen Oakley Willis, 796.

[3] John Oakley and Louisa Jones did not come across the plains in the same company, and they were not married until later in Utah. See comments by Ellis and Boone for their early history.

[4] As noted in the introduction, Kanab became very important to the settlement of Arizona. It was the last settlement where supplies could be obtained and colonists sometimes overwintered there before going to Arizona.

[5] Although Clayton uses the word “lover” here, she may actually mean “husband;” some entries in the Ancestral File list another marriage for Louisa—to a “Mr. White.”

[6] Hannah Jackson suggested that as Louisa was helping her husband or brother unload heavy items, she suffered a miscarriage and developed a hernia which essentially left her in bed for eleven years. Hannah J. McCleve Jackson Collection, 485−86, MS 13883, CHL. Catharine Cottam Romney visited Louisa in 1884 and told her mother that she “found Sr. Oakley about as usual. dressed, but lying on the bed. she dos’nt [sic] appear very [ill], but dont get around much if any.” Hansen, Letters ofCatharine Cottam Romney, 92. For additional information on the family, see Ellen Kalantha Oakley Willis, 796; fn. 142 identifies the married daughter and tells about the disabilities of Robert Jones.

[7] She is listed as “Louisa Willis.” 1900 census, Snowflake, Navajo Co., Arizona. Robert Jones died November 17, 1913, at Snowflake, age seventy-nine.

[8] The easiest way to see the manifest is at https://

[9] Although lists of rescuers have been printed elsewhere, the most complete list may be at MPOT. They note that the Rescue Companies of 1856 “involved hundreds of men, teams, and wagons. There is no single record of who went out on this rescue effort so the names of the men who participated in this act of charity comes from various sources.” There are 368 men on their list including John Oakley. MPOT.

[10] Riverton Wyoming Stake, Remember, E-31.

[11] Ibid., 137.

[12] Ancestral File; Oakley and Patterson records in 1850−80 census records in Utah; MPOT.

[13] Hansen, Letters of Catharine Cottam Romney, 92. This makes it sound like all three children died about the same time. Daughter Thyrza died May 13, 1869, age seven, and son William Jones Oakley died May 20, 1869, age four. Two conflicting records exist for the baby: Louisa Dicey Oakley was born February 28, 1867, and either died on August 13, 1867, or May 13, 1869. It might be possible to find a conclusive record, but it may be that this letter from Romney contains the best information.

[14] “Samuel Openshaw,” in Clayton, PMA, 365−66; “Samuel Openshaw,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 4:526.

[15] “Samuel Openshaw,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 4:526.

[16] Sarah Elizabeth Spainhower, born August 21, 1857, married Samuel Openshaw on August 26, 1872. She died August 8, 1928 in Oroville, Butte Co., California.

[17] This is apparently Guffick, leader of a band of peaceful Utes who lived near Esther’s home. Peterson, Utah’s Black Hawk War, 173; Johnson, My Life’s Review, 229–31.

[18] PWA originally said she survived four more years and listed a death date of 1925. However, the correct death date is 1926 and the text has then been corrected. AzDC.

[19] The “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune” comes from William Shakespeare’s play Hamlet and is part of Prince Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” soliloquy as he considers suicide. It seems particularly appropriate juxtaposed here with the quote from Esther Openshaw’s patriarchal blessing.

[20] Merrill, One Hundred Footprints on Forgotten Trails, 239–41.

[21] Rose A. Openshaw, “A Brief Sketch of my Parents,” Earl Merrill Collection, Box 15, Folder 16, Mesa Room, Mesa Public Library.

[22] When RFC submitted this sketch to the FWP, it was written in present tense because Ethelinda was still alive. By the 1960s when Clayton transferred it to PWA, Ethelinda had died, so Clayton changed some of the tense and added the last sentence.

[23] From 1880 census, William J. Osborne, Phoenix, Maricopa Co., Arizona; 1900 census, William Osborn, Township 1, Maricopa Co., Arizona Territory; and AzDCs: Maude Evangeline Foster, Gertrude Osborn Harris, Estelle Osborn Keddington, Myrtle Osborn, and Winfield S. Osborn.

[24] The surname for this family is generally, but not always, spelled without an e. The subject’s given name is sometimes listed as Etha or Ethel.

[25] This may refer to the seven known daughters of Ethelinda’s mother: Mary (born 1851), Matilda (1854), Anna (1855), Ethelinda (1857), Flora (1859), Marilla (1861), and Eula (1866). William had previously been married to Adeline Byers who gave birth to at least four children: Jane Elizabeth (1841), Thomas Pinkney (1843), James (1846), and Margaret Adeline (1848). The family can be found in the 1850 and 1860 censuses, but not in the 1870, presumably because this was during the six-month move to Arizona. 1850 census, William P. Murray, Pontotoc Co., Mississippi; 1860 census, W. P. Murray, Burleson Co., Texas.

[26] This is probably Maricopa Wells, an area in present-day Pinal County that was of great importance to early travelers because it was one of the few places where water was available. Granger, Arizona Place Names, 299.

[27] William Pinkney Murray was thrown from a horse and died in May 1871; he is buried in the Independent Order of Odd Fellows Cemetery in Phoenix. The married daughter may be Margaret Adeline; it is not Elizabeth Jane who married R. B. Roody and lived in Texas. 1880 census, R. B. Roody, Hamilton Co., Texas; findagrave.com #35713423.

[28] Ethelinda may have said “brothers” to RFC which may have been written down as “Murray boys;” it seems likely this means Ethelinda’s brothers-in-law. Ethelinda’s brother, Thomas Pinkney Murray, did not come to Arizona until 1887 and then settled in the southern portion of the state; he is buried at Naco, Cochise County. It is not clear that the James Murray in early Phoenix was Ethelinda’s brother. Findagrave.com #43916806.

[29] Myrtle Osborn died December 8, 1938. AzDC.

[30] AzDC. PWA had a death date that was incorrect by ten years; besides correcting the death date, the number of years married was also recalculated.

[31] Henry Giles (1809−82) began life as a Roman Catholic in England, converted to Protestantism, and became a Dissenter. He traveled to the United States, and is remembered today as a Unitarian minister and writer of some renown. This quote was not located.

[32] PWA originally had the burial date, not the death date, here. AzDC.

[33] Luckingham, Phoenix, 12–26.

[34] Margaret Finnerty, “Sidney P. Osborn,” in Myers, Arizona Governors, 64−76.

[35] “Arizona, Select Marriages, 1888–1908,” ancestry.com. Names spelled as found in database.

[36] 1880 census, John Taber Alsap, John A. Chenoweth, Ethalinda H. Osborne, and George Buck, all Phoenix, Maricopa Co., Arizona.

[37] Harry Arizona Drachman, “Freemasonry in Arizona,” in Gould, Gould’s History of Freemasonry throughout the World, 5:17–28. Anna and John Alsap are buried in the Masonic Cemetery in Phoenix, but the Greenwood Cemetery, where the Osborn families are buried, was also originally a Masonic cemetery.

[38] Raymond Carlson, “Governor Sidney P. Osborn: A Native Son Becomes Chief Executive,” in Clayton, PMA, 367−71.

[39] Margaret Finnerty, “Sidney P. Osborn,” in Myers, Arizona Governors, 65.

[40] “James Clark Owens,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 3:191.

[41] Ibid., 2:217–18.

[42] Because Skillman, a granddaughter, used family relationship names (Grandmother, Uncle, etc.) which make it difficult to understand the story, and at the suggestion of descendant Brenda Johnson, family relationship names have been changed to given names in many instances. Also, I, II, and III were added to better identify a particular James Clark Owens. Parentheses Skillman used within direct quotes (which would be brackets today) have been retained.

[43] Although this account does not state when the Robison family left New York for Illinois, Joseph Smith was killed on June 27, 1844. In addition, the last Robison child to be born in New York was Proctor, March 5, 1842, and the first child born in Crete was Almon, May 15, 1845.

[44] James Clark Owens I died in January 1847. Owens left his family to seek work and did not return. His body was never found, and there are conflicting stories of his death.

[45] This sentence was moved to the end of the paragraph for clarity.

[46] Franklin Horace Owens was the father of Lenora Owens Skillman.

[47] This quote was not located in Smith’s published journal, but the entry for September 25, 1880, tells of the organization of the Snowflake Stake, with high council, bishops, and quorum presidents. James C. Owens was noted as bishop of the Woodruff Ward. Journal of Jesse Nathaniel Smith, 249; “James Clark Owens,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 3:191.

[48] Several species of madder were used. The Eurasian species, Rubia tinctoria, which has small yellow flowers and a red, fleshy root, was cultivated in the U.S. and was once an important source of red dye.

[49] Lenora Owens Skillman, “A History of Lucretia Proctor Robinson [sic] Owens,” in Clayton, Pioneer Women of Navajo County (partial manuscript of PWA at the Mesa FHL), 2:154−66.

[50] Meaning they had to choose to leave their father, mother, sisters, etc. as mentioned in Mark 10:29–31.

[51] Brenda Gardner Johnson to Ellis, March 31, 2014.