N

Roberta Flake Clayton and Lydia Ann Lake Nelson, "N," in Pioneer Women of Arizona, ed. Roberta Flake Clayton, Catherine H. Ellis, and David F. Boone (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 479-498.

Charlotte Ann Tanner Nelson

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP[1]

Maiden Name: Charlotte Ann Tanner

Birth: May 5, 1870; Ogden, Weber Co., Utah

Parents: Seth Benjamin Tanner and Charlotte Ann Levi

Marriage: Price Williams Nelson (b. 1855); January 13, 1886 (div?)

Children: Francis Tanner (1886), Seth Benjamin (1887), Joseph William (1889), Elizabeth (1891), Ezra Beswick (1893), Gilbert Levi (1895)

Death: August 3, 1939; Eagar, Apache Co., Arizona

Burial: Taylor, Navajo Co., Arizona

One of Arizona’s pioneer nurses was Charlotte Ann Tanner Nelson. She was born in Ogden, Utah, on May 5, 1870. Her parents were Seth Benjamin and Charlotte Ann Levi Tanner. When she was only two and a half years of age her mother died, leaving seven small children, the eldest, John, being fifteen at the time. Because of her tender years, the other children were very kind to her, particularly John, who by his love and care of her won her undying affection.

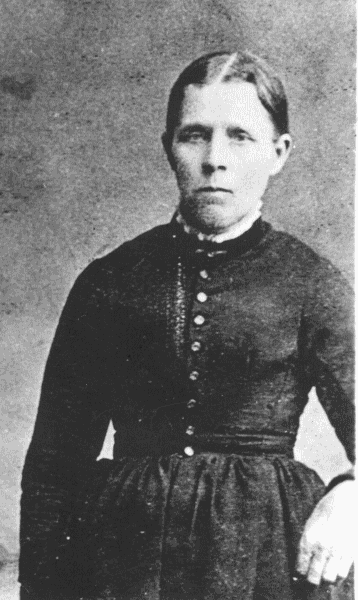

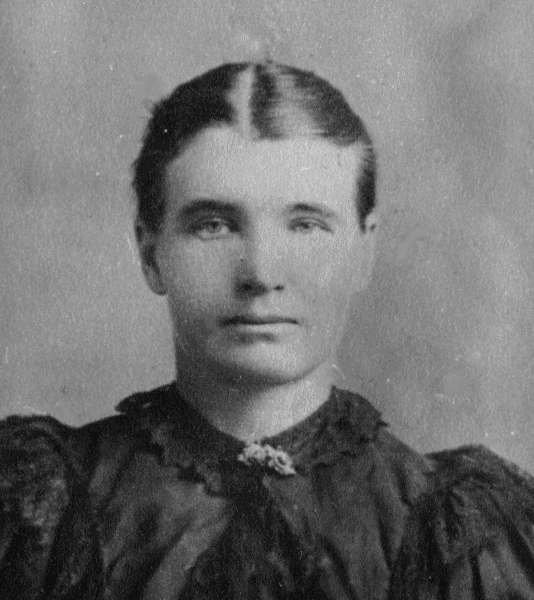

Charlotte Ann Tanner Nelson. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Charlotte Ann Tanner Nelson. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

At a very early age Ann began making herself useful in the world—first, by carrying water and doing other small tasks for an invalid, and then at the age of four, becoming the eyes of her Grandmother Levi, who had lost her sight. During two years, she was always near to lead her grandmother wherever she went. She had learned to do many things, among them to knit her own stockings.

It wasn’t from choice that Ann became a pioneer of Arizona. She had been living with her grandmother when her father came for her in December 1876. She says, “I had such a horror of Arizona, the land of Indians and wild animals, that when Father came I hid under the bed and cried myself to sleep. The next morning when they were ready to start, my Uncle Sidney had to take me to town and literally dump me into the wagon with my father and brothers and my new stepmother. The latter was a Danish woman and had no experience with children nor American ways and could scarcely speak a word of English. She had been a dressmaker and was a very fine seamstress, but the trouble was, in those days, we had very little to sew.”

While on this trip to Arizona, there was a clash of wills between Ann and her father in which he came off victorious, but unselfish Ann feels to this day that she was justified. On a former trip, Mr. Tanner had taken part of his family including a daughter older than Ann. He had bought each of the girls a pair of shoes, and when one morning he told Ann to put hers on, she refused, not telling him that she didn’t want to wear her new shoes until her sister could wear hers also. She bore her punishment with a fortitude that characterized her whole life.

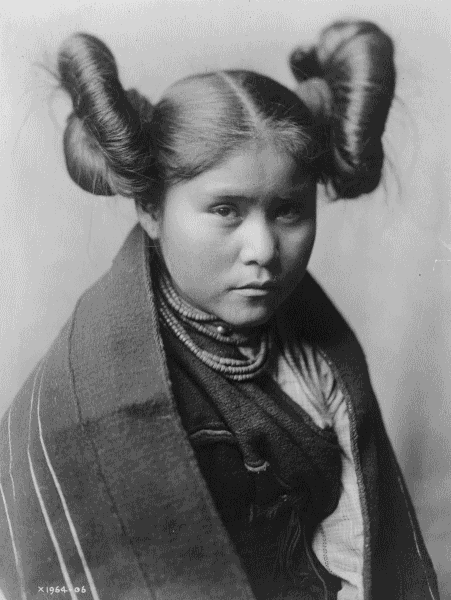

The Tanners arrived at Moencopy, Arizona, on January 2, 1877. There were few neighbors besides Indians, but these were mostly the peaceful Navajo, Hopi, and Oraibi tribes.[2] Some of the Oraibi girls took quite a fancy to Ann and used to dress her hair in the fashion worn by brides. It was done up on a piece of wood, which stood out about four inches from the head and was then patterned after a wheel. They taught Ann to make “peeke,” a bread made from blue corn raised exclusively by the Indians. This was rolled flat on hot stones and curled up when baked. Ann says, “The Indian girls named me after these cakes and called me ‘Povel Peeke.’”

Ann used to spend her Sundays roaming over the hills hunting rubies, or down at the river fishing.[3] One day the girls got tired trying to fish with a bent hook and having no seine they improvised some by taking off their long sleeved petticoats, tying the neck and wrists, then dragging them through the water. They caught plenty of fish, more than they could carry. But they caught something else when they got home with their lace-trimmed petticoats completely ruined by the red mud of the Little Colorado.

When the Hopi girls of Oraibi dressed Ann Tanner's hair "in the fashion worn by brides," it would have looked like this. This style was worn by unmarried girls; after marriage their hair was worn plain and never wrapped around the hoops. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

When the Hopi girls of Oraibi dressed Ann Tanner's hair "in the fashion worn by brides," it would have looked like this. This style was worn by unmarried girls; after marriage their hair was worn plain and never wrapped around the hoops. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

Her father was instructed to go to the place on this river where emigrants first contacted it and there to build a granary where travelers from Arizona, bound for Utah, could store their grain and other feed for their horses on the return trip.[4] While there, he built a two-room log house for his family to live in. It had a mud roof. A steady rain of long duration caused the roof to leak. Her father was not there, so Ann and her sister climbed up and were going to put a heavy wagon cover over it to keep the rain from ruining everything within. Ann got too near to the edge and slipped and fell to the ground, hitting the back of her head on a large rock. She lay unconscious for fifty hours and from this fall developed weak eyes and ears and a sickness that lasted a year.

At this time the country was filled with desperados and cattle thieves. Ann and her sister were now to be detectives, reporting to the sheriff the color of the eyes and hair of every man that passed.

While the family was living on the Little Colorado, a long continued rain brought the river up filling their house with red, muddy water to the depth of two feet and the women and children had to be taken to the hills on a hastily improvised raft. They then moved to Moenave.[5]

One time the two girls went for the milk cows. They had to cross a dry arroyo on their way.[6] A heavy rain fell, and when they returned they found the arroyo a raging torrent. The girls were wet and cold, and must get home, but how to cross this swollen stream they knew not. Their childish faith prompted them to pray, then they each took hold of a cow’s tail with both hands and drove the cows into the treacherous stream. The girls held on for dear life, and the cows swam across, taking the girls with them. Thus was their faith rewarded.

On January 13, 1886, Ann was married to Price Williams Nelson. For six months they lived at Lee’s Ferry on the Big Colorado. In speaking of some of the experiences through which she passed in those early days, Mrs. Nelson says, “I have lived for months where my only neighbors were Indians and my only music the howl of the coyote. We ground our wheat in a coffee mill. Our only food was beans, venison, and cow’s milk. I tanned our deer skins and from them made shoes. Gleaned wheat from which I saved the straw and braided hats. I colored the straw with orange, brown, and black dyes—the orange taken from the cypress and lye, the brown from sumac, and the black from oak bark.”[7]

One of her homes was made with poles stuck upright in the ground, the cracks “chinked” with mud, and then Mrs. Nelson declares she whitewashed the inside with a paste made of buttermilk and ashes of cottonwood and oak.

Mrs. Nelson studied nursing, obtaining all the medical knowledge she could and went out as a nurse, bringing, according to her account, 1,234 babies into the world, never losing a mother or a child. She took care of cases in a radius of forty miles from her home near Springerville, sometimes having as high as nine patients at once. She never had a doctor in attendance. At one time a Mexican woman gave birth to triplets and all the help Mrs. Nelson had was a ten-year-old Mexican. She remembers one trip over the mountain from Eagar to Alpine when the snow was so deep she had to keep shoveling it out of the front of the buggy she was riding in.

From this short sketch of the life of Charlotte Ann Tanner Nelson it is certain that she was a worthy pioneer of Arizona even though an unwilling one.

She died August 3, 1939, at Eagar, Arizona, and was buried in Taylor, Arizona.

Ellis and Boone:

When the pioneers traveled from Lee’s Ferry to the Little Colorado River settlements, they followed the Tanner Wash, crossed a watershed divide at Cedar Ridge, and traveled along the Hamblin Wash until it joined the Moenkopi Wash, which emptied into the Little Colorado near Cameron. As can be seen from the names, these were all washes and not permanent streams.[8] In fact, when Joseph Fish was traveling to Utah in 1879, he did not find the Little Colorado River flowing between Winslow and Cameron. Instead, he found little pockets of water, some of which were salty, some bitter, and a few useful for drinking. He wrote, “At Black Falls we found a little [water], but it was not fit to use as the fish had died in it and it smelt very bad like carrion.”[9] This helps understand the location and timing of Ann Tanner’s fishing story. Not only did she mention the red water of the Little Colorado, but the ephemeral nature of washes places the story after they were living near Cameron rather than at Moenkopi.

Fishing is only sometimes reported for Mormon pioneers in Arizona. It is estimated that when they came to Arizona there may have been only about twenty-five different species in the entire state, and many were small, not useful for human consumption.[10] Nevertheless, W. L. Minckley reported that people in the mid-1880s would make an annual trip “to the headwater streams of the Little Colorado and Salt Rivers. All members of the party would fish, and the [Arizona] trout were ‘salted’ in barrels for use in the coming winter.” Minckley also cited the St. Johns Herald of July 5, 1888, reporting on a trip by Thomas Carsen “to the head waters of the Black River for the purpose of enjoying a short season of sport in hooking and delivering some of the speckled beauties that are known to abound in the stream.”[11] Finally, the Colorado River squawfish was abundant in the canals of the Salt River Valley prior to 1915, and was used as fertilizer, food for hogs, and sometimes even food for humans; it is now extirpated from Arizona.[12]

Probably the most important aspect of this sketch, however, is that it makes almost no mention of the years between Ann’s marriage in 1886 and her death in 1939, including the fact that she was a second (or in other words, plural) wife. Price Nelson had earlier married Mary Louisa Elder on January 11, 1878, and they eventually had ten children. All of Annie’s children died in infancy except her son, Joseph W. Nelson. Some of her married life, she lived in Cave Valley, Chihuahua, Mexico (where Joseph was born).[13] The family cannot be located in the 1900 census, which may mean that they were still in Mexico.

Also not mentioned here is the eventual separation of Price and Annie; whether they ever obtained a divorce is not known. In 1910, Annie was living with Benjamin and Waity Crosby in St. Johns; her son Joseph had just married and was living in Flagstaff. By 1920, Joseph and family had moved to Taylor, and Annie was living with them; she listed herself as “widowed” on the census, even though Price was still alive. When Price’s first wife, Louisa, died in 1916, he remarried a year later (to Annie Byron McCotter).[14] Annie Tanner Nelson died in 1939 in Eagar, although the death certificate stated that her usual places of residence were Taylor (presumably living with her son) and Mesa (probably where Roberta Flake Clayton interviewed her in 1936).[15]

Lydia Ann Lake Nelson

Autobiography[16]

Maiden Name: Lydia Ann Lake

Birth: May 13, 1832; Camden, Ontario, Canada

Parents: James Lake and Philomela Smith[17]

Marriage: Price Williams Nelson (b. 1822); December 31, 1850

Children: Edmond (1851), Samantha (1853), Price Williams (1855), Lydia Ann (1856), Lorania (1859), Jane (1861), Hyrum (1863), James Mark (1865), Alvin David (1868), Thomas George (1870), Levi (1872), Wilford Bailey (1874), Philomelia (1876)

Death: January 16, 1924; Eagar, Apache Co., Arizona

Burial: Eagar, Apache Co., Arizona

In giving a sketch of my life, I’m compelled to depend largely upon my memory since I kept no record of myself. Yet I think what follows is quite accurate owing to the fact that my life from childhood has been cast with the Latter-day Saints, and in their early movements I took part, but only as a child.

My father joined the Mormon Church in 1832 while living in Canada. He was among the first to accept the doctrine under the teaching of Brigham Young and was among the first fruits of that man’s missionary labors.[18]

I was born May 13, 1832, at Camden, Upper Canada, and was six months old when my parents joined the Church.[19] Our family remained there about one and a half years after that event and then moved to Kirtland, Ohio. My father worked on the temple, being employed as a brick maker. Owing to the persecution, we were compelled to leave our home at Kirtland and move westward. We intended going to Missouri, but the troubles arising between our people and the Missourians caused us to stop in Illinois. My father rented a large farm near Springfield and remained there until the Saints began to gather at Nauvoo. Wishing to get closer to the main body of Saints, we rented another farm within fifteen miles of Carthage and were living there when Joseph and Hyrum were killed, and well do I remember that day.[20]

That afternoon my father sat reading his Bible. He read aloud the passage, “The wicked flee when no man pursueth.”[21] At that instant, a man rode up to the fence and called out “Joe Smith is killed.” We looked out and saw men, women, and children coming with all their might; some in wagons, and others on horses, and all were fleeing from the awful scene at Carthage. My father gathered a few household goods into his wagon and moved to Nauvoo, leaving a farm and a beautiful crop for which he never received a cent.

We passed through the trials common to the Saints at Nauvoo and moved with them to Council Bluffs. Here my father built a log cabin, which we occupied for about two years. My brother Barney Lake went with the Mormon Battalion to fight with Mexico.[22]

Owing to the lack of teams to cross the plains, we were compelled to go down into Missouri and work for them. My brother, sister, brother-in-law, and myself went down in the fall. I got a position as a dishwasher and baby tender in a tavern. About Christmas time while browning coffee in a large bake oven over the coals of a fireplace, my clothes suddenly blazed, and I narrowly escaped being burned to death. I attribute my almost miraculous recovery to the administrations of Elders Phineas and Lorenzo Young, who chanced that night to stop at the tavern.[23] As soon as I recovered, we went back north to the “Bluffs.”

Lydia Ann Lake Nelson. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

Lydia Ann Lake Nelson. Photo courtesy of FamilySearch.

A few months after our return, Father, with all the family, moved down into Missouri. He was fortunate in finding work for himself, and we were soon equipped with good ox teams and wagons. The people there were very kind to us. In the summer of 1850 we went forth again in time to join a company of Saints moving to the Valley. My father was chosen captain of fifty. Our company was well supplied with provisions of food and clothing. Father had one large wagon with three yoke of oxen and a smaller one with two. Our family then consisted of Father and Mother, my two brothers, Bailey and George, and my sister, Samantha, and myself. Along with our company were my three married sisters, Sabre Dixon, Clara Taylor, and Jane Ordway, and my married brother, Barney, who had just returned from the Mexican War. While on our way Barney’s wife was buried on the plains.[24]

The most vivid event of the journey occurred at Green River, Wyoming. In crossing the river the wagon box floated off and began drifting downstream. In the box were a young woman named Snyder and a little girl about nine years old. All was excitement for a few minutes. The only man in the company who dared to swim the stream and effect a rescue was a youth named Price W. Nelson, a young man who at the time I had paid no attention to. He was of quiet nature, and I knew nothing of him except that he drove his aunt’s team. After this, we two became better acquainted which resulted in our marriage after arriving in Salt Lake City. We were married on the last day of the year 1850 in the Old Fort at Ogden. The ceremony was performed by Elder Lorin Farr.[25] Of the many things said at the time, the prophetic utterance of my father proved the most true. He said, “Price is a good man, but he will never be contented anywhere.”

Our first child was born October 30, 1851, while living at my father’s ranch five miles north of Ogden. We named him Edmond. The next year, about the first of June, we started by team to California and while traveling fell in company with an apostate named Chapman and five other men who were driving stock. The journey throughout was quite pleasant. We stopped in San Bernardino and, liking the place, decided to make it our home. My husband went into the sawmill business with Amasa Lyman and Charles Rich.[26] The mill ran during the winter but closed in the summer due to the lack of water. During this time, for seven years, we moved each fall from the valley to the mountains and returned to the fertile valley in the spring. Three children were born there. They were Samantha, October 28, 1853; Price Williams, August 29, 1855; and Lydia Ann, December 12, 1856.

Heeding the call of the First Presidency, we, with other California Saints, came back to Utah. We stopped at Payson and began to build up another home. Here my daughter Lorana was born March 10, 1859. About this time we heard that my brother Bailey had been killed by the Indians.[27]

Not being satisfied at Payson, we remained there only about eighteen months and then went to Franklin, Utah [Idaho]. Again Brother Nelson took up mill work, laboring as a sawyer in the mill of Thatcher and Benson, then operating a sawmill at Logan, Utah. While there my daughter Jane was born March 22, 1861.

The following summer, I joined my husband at Logan. There Hyrum was born January 10, 1863, and James Mark on August 12, 1865. In that village we lived comfortably for six years.

Brother Nelson was called to assist in settling the Muddy Mission. We found there an ideal climate and very productive soil, and followed farming for a livelihood. There my son Alvin was born January 7, 1868, and Thomas George on December 14, 1870.

There in Nevada we had an abundance of such things as could be produced from the soil but had difficulty in obtaining clothing. Conditions were favorable for the building of comfortable homes, when trouble arose between the state authorities and settlers. Heavy taxes were imposed, and people were forced to withstand much abuse. President Young visited us and, seeing the situation, advised us to move away. We acted immediately on the advice and left our homes and fertile lands with luxuriant crops almost ready to harvest and went to Glendale in southern Utah, arriving there with our large family with only what provisions we could carry in one wagon. Our livestock consisted of a team of horses and two cows.

We found it somewhat difficult to live, but were not long in finding work and again supplying ourselves with the necessities of life.

During the seven years we lived there, three children were born to us. They were Levi, born on April 4, 1872; Wilford Bailey on April 26, 1874; and our last child who only lived three weeks, Philomelia, on February 20, 1876.

Brother Nelson and the boys constructed a shingle mill which they operated about four years and did fairly well financially. My son George died while there, and four of the older children were married. They were Edmond to Mary Caroline Brinkerhoff; Samantha to Warren Johnson; Price W. to Louisa Elder; and Lydia Ann to David Brinkerhoff.

During our residence in Long Valley, a general move of settlers was in progress, and people were being called to assist in building the country south of us—also to help in the Indian Mission work then being conducted in northern Arizona.

Edmond was called to assist Warren Johnson at Lee’s Ferry. We went to Moencopy and were among the first settlers of that place. During our one and a half year’s sojourn there, we lived with the missionaries in the Old Fort.

My daughter Lorania was married to Joseph Foutz the morning we left Moencopy.[28] They started to St. George, and we to Pine Creek. At Pine Creek we went into ranching and stock business and soon had a good home.

We made a trip back to St. George to [see] our daughter Jane and son-in-law, John A. Allen, who were going to the temple. Our purpose was to be sealed to each other and to have our children adopted.[29] Not long after our return, Hyrum was married to Martha Sanders.

The Saints were making settlements in Mexico and my husband, desirous to assist in opening a new country, was induced to break up our home and move south, choosing Cave Valley as our destination. Brother Nelson with the boys, Bailey and Levi, put up a small gristmill. They also made chairs.

After being in Mexico three years, my brother George Lake and I went to the Logan Temple to be sealed to our parents. I spent the following winter with my sister Eliza Smith at Logan and returned the next summer to Mexico.

After remaining about five years in Cave Valley, we moved to Oaxaca in Sonora and made a home about five miles up the river from the town. While there Alvin married Tennie Johnson, and Bailey, Edith Nichols. We built another comfortable ranch home.

Brother Nelson’s health began to fail in the year 1902. His ailments were dropsy and heart failure, which terminated in his death October 27 of that same year. Two years after my husband’s death, a flood swept away everything from the ranch, and I went to live with Alvin.[30] Since then I have spent a short time with each of my children in the following places: Lee at Tombstone, Arizona; Bailey at Morelos, Sonora, Mexico; Jane at Hubbard, Arizona; Lorana at Colonia Juaréz, Mexico.

When the Mormons were driven from the country, I came out with the main company and went to Hubbard, Arizona, on August 5, 1912.[31] Edmond came after the following October. I am now (February 26, 1914) at his home in Eagar, Arizona.

I am proud to say that of my thirteen children, eleven raised large families. My grandchildren total 113 at the present, and my great-grandchildren total about 80—making a total posterity of about 206.

Ellis and Boone:

Lydia Ann Lake Nelson lived another ten years and died at the home of her son Edmond in Eagar, Arizona, on January 16, 1924, age ninety-one. Although her husband is buried in Oaxaca, Mexico, she is buried in Eagar, Arizona.

Some of the Mormon pioneer women from Utah moved to Arizona and became a stable part of a single community. Women such as Emma West Smith and Emma Swenson Hansen never made a second move. Other women moved multiple times as did Lydia Ann Lake Nelson. Lydia herself blamed these moves on her husband’s nature: his need to be on the frontier or need for new adventures or discontent with an area. Of course, an occupation such as sawmilling also dictated such moves. It was normal to move a sawmill when nearby logging was no longer possible.

Nevertheless, Lydia Nelson moved many times both before her marriage and after her husband’s death. Lydia Lake was born in Ontario, Canada; lived in Kirtland, Ohio; lived in Springfield, near Carthage, and in Nauvoo, Illinois; lived at Council Bluffs, Iowa; lived in several places in Missouri; and lived in Ogden, Utah, all before her marriage. After her marriage to Price Nelson, she lived in San Bernardino, California; Payson, Utah; Franklin, Idaho; Logan, Utah; the Muddy, Nevada; Glendale, Utah; Moenkopi, Arizona; Pine, Arizona; Cave Valley, Chihuahua, Mexico; spent a winter in Logan, Utah; and lived in Oaxaca, Sonora, Mexico. As a widow, Lydia Nelson spent the first ten years living in Tombstone, Arizona; Colonia Morelos, Sonora, Mexico; Hubbard, Arizona; and Colonia Juaréz, Chihuahua, Mexico. The last ten years of her life, Lydia lived sometimes in Eagar and sometimes in Hubbard, Arizona. There was never a time in Lydia Nelson’s life that she did not move to better meet her needs.

Ann Jane Peel Noble

Roberta Flake Clayton, FWP[32]

Maiden Name: Ann Jane Peel

Birth: February 15, 1852; St. Louis, St. Louis Co., Missouri

Parents: Benjamin Peel and Nancy/

Marriage: Edward Alvah Noble;[33] January 31, 1870

Children: Mary Jane (1870), Nancy Louisa (1872), Artemesia (1874), Louisa Beman (1877), Maude (1879), Edward Alvah (1881), Pearl Emeline (1883), Joseph Bates (1885), Armeda (1887), Benjamin (1889), Charles Leslie (1891), Hazel Elnora (1893), LeGrande (1896)

Death: December 17, 1945; Mesa, Maricopa Co., Arizona

Burial: Alpine, Apache Co., Arizona

What tragedies and comedies used to commingle in the long immigrant treks over the plains! In the company destined to reach Salt Lake City in November 1862 was one outfit with the not unusual combination of a yoke of oxen and a yoke of cows hitched to a wagon so loaded with household gear that the father, mother, and one child had to walk most of the way. The child would get so tired at times that she dared occasionally to park herself on the handy back steps of the next wagon, until one day, the driver’s ox whip laid cruel welts across her back.

That little girl was Ann Jane Peel. Her father, Benjamin Peel, was a nephew of Sir Robert Peel, famed premier of England.[34] Benjamin and his brave wife, Nancy Turnbull, had been disinherited and driven from home for having dared to join the Mormons. How and when they reached America is unrecorded.[35] Their two children, Ann Jane and Robert, were born and grew to school age in St. Louis. The father, a calico printer in Manchester, turned to whitewashing, plastering, and painting in the New World. Let this little touch of workmanship indicate the grain of the Peel tribe: Summoned one day to whitewash a fine home, he found all the floors bare and the furniture covered. He insisted on restoring the rooms as they were before beginning the job. “I put my whitewash only on the walls,” he said proudly.

Benjamin Peel, an Englishman, was threatened with draft into the Southern army—a cause he detested. This fact brought to a head the long cherished, long delayed journey to Utah. He had not intended that his wife and daughter should walk; but when only a few days out, one of his oxen died. This animal he could have replaced, but it happened coincidentally that an old lady was stranded for a similar reason. There seemed therefore nothing else to do but take on her belongings, for the use of her remaining ox. Nancy Peel was thus confronted with the grim necessity of dumping on the open plains goods in the category of luxuries to make room for their helpless, but doubtless very worthy passenger, and to walk a thousand miles instead of ride.[36] She rose to the occasion, however, then and ever after, without complaint, as did also her husband and daughter.[37]

In Utah, Benjamin Peel turned to gardening and peddling his truck [produce] in the city. Ann Jane, at fourteen, hired out as general servant and cooked for a family of nine over an open fireplace. Her wages were about $2.00 per month, paid in whatever her father could turn to value in support of the family. The one outstanding, long-cherished return for this lowly service was the fine dress of checked delaine, which served her many years for best. Verily, pioneer life brought out gratitude and appreciation!

Ann Jane Noble was born February 15, 1852, at St. Louis, Missouri. She went to school in St. Louis and played marbles on the stone steps.

Jane’s parents settled in Bountiful, Utah, where she lived until her marriage, January 31, 1870. She was married to Edward A. Noble soon after his return from a four-year mission to England. It seemed to be love at first sight. Ed went to Church and sat down. He asked the man next to him who that girl was. “She is my daughter,” answered Benjamin Peel. “I’d like to call,” said Ed. “Come along,” said Peel.

Mounting his horse one afternoon, Ed started out to ask Jane for her company to the dance that night. He fell in with three other boys on the same errand. They decided to race for the prize. Two fell out, and the other two raced. Ed won. The courtship was short, but ended happily.

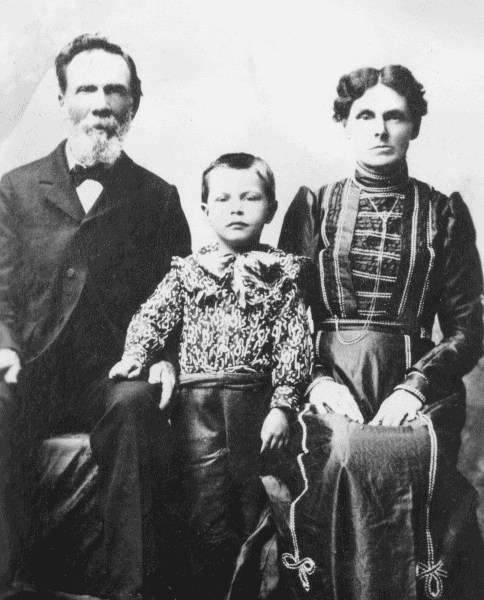

Edward Alvah and Ann Jane Peel Noble with unidentified child; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

Edward Alvah and Ann Jane Peel Noble with unidentified child; Margaret J. Overson, photographer. Photo courtesy of Overson Collection, St. Johns Family History Library.

Brigham Young, the outstanding pioneer, succeeded in his far-flung settlements by drafting only men and women of known hardihood and stamina. Thus it happened, only two months after his marriage, that Elder Noble was called, at the April conference 1870, to reinforce the recently settled town of Kanab in the very southern part of the state. Learning, however, that the young man recently returned from a long mission, President Young made the call optional.

But Edward Alvah would not exercise his option, much as the valley north of Salt Lake, already famous for its rich soil, might appeal to his self interest. Your really great man always chooses the harder alternative, a fact which may ultimately explain why the periphery of the later Zion is often so rich in men and women of character, while the smug centers abound in mediocrities.[38]

But while Elder Noble chose the hard part himself, it was equally characteristic of his tender heart that he would not let his charming, young wife go south with him till he had built her a home. She joined him the following spring. Here they lived for ten years; here the first five of their thirteen children were born, and one little grave was dug and left behind. As counselor to the bishop, Ira Stewart, Elder Noble had ample scope to help build up faith in the settlers, harmonize their differences, and establish this outpost of the growing Mormon commonwealth. For a living he farmed, raised cattle, and freighted to and from Salt Lake City.

But now came a still more urgent frontier call. St. Johns, Arizona had been settled tentatively for some years, but lately, thru influx of bad men due to cattle and other interests, the Latter-day Saint settlers were in extreme danger. One of our men, Mathew Jenney [Nathan Tenney], had already been foully murdered, (and a fate like that of Hawn’s Mill, Missouri, loomed on the horizon for all of them).[39] Elder Noble and his family reached there January 1, 1880, with other reinforcements. By spring the tide of peace and security having returned, a new call led him to the extreme eastern part of the state.

Alpine is the eagle’s nest, not only of Arizona but of the southern part of the continent. The valley itself is 8,400 [8,050] feet in altitude and the mountains loom still higher, though lacking the ruggedness of their European namesakes; a valley appealing to the loftiest instincts of the out-of-door man or woman. Its grassy slopes and heavily timbered mountain stretches greet the eye on all sides.

Alpine, fifty years ago a hundred miles from any kind of base for succor or supplies, presents an aspect that can only make the reader pause and marvel at the stoutness of heart and trustfulness in God which animated that little band of pioneers who entered it in the early fall of 1880.

No sooner had they reached the eagle’s nest, than came terrifying news that Apaches were again on the rampage. That word “again” proved their salvation; for so chronic had these raids become during the previous years, that the hunters, trappers, and cattle outfits had combined to build a rude fort for emergencies. The half dozen log huts inside rock walls were dilapidated through some years of disuse, and a prolonged rain was in progress, when the settlers reached the enclosure. To accentuate the climax, Ann Jane was on the very eve of confinement with her sixth child. Burns, the trapper, moved out of his cabin to facilitate the auspicious event. Even at that, a parasol had to be opened over the bed to keep off the muddy drippings from the dirt roof.

What an adventure to treasure in memory and laugh at when the event was all over, and sunshine once more flooded the valley! Before that relief came, however, the plucky little woman was again on her feet, sloshing about in the mud of the dirt floor, and cooking for her little family at the open fireplace. In the meanwhile, the men folks couldn’t await the issue of the Indian outbreak. Winter was approaching, and they had to be on their homesteads cutting logs and building cabins for their loved ones, and corrals and shelters for their cows and horses. Luckily, through Uncle Sam’s intervention the war scare was soon over.

The Noble Ranch was an open haven not only open to everybody, but inviting; and never was a charge made for man or beast. Talk of giving till it hurts; the hurt was never felt here—only the joy of giving and serving till the cupboard was bare, and the last spare veal was killed. “We have had as many as twenty people for a week at a time, usually visitors at ward conferences, but sometimes friends who came up for the sheer pleasure of breathing.”[40] And when they were gone, the father and mother would only laugh at the yawning emptiness left in the larder and kitchen!

Many of the years that followed were filled with tragedy, poverty and all the trials that go with pioneer life. During these years there were five graves added to the Alpine cemetery. The other lonely little grave is in Bountiful, Utah. Most of these tragedies were experienced on the ranch during the bleak winter months, with the snow two and three feet deep.

One of the sweet, comforting remembrances of those days is the loyalty of the Alpine people. Night after night, one or more would trudge through snow, wind, or sleet to sit by the bedside of sick ones or bring comfort and cheer to a family bereft of loved ones. Sister Jepson, the “ministering angel of the sick room,” was always ready to go any time of the night or day to do her share in relieving the sick and ushering little souls into the world.

Jane’s husband was bishop and presiding elder of Alpine for about twenty years.[41] At one time he presided over both Alpine and Nutrioso, walking over the mountain eight miles every other Sunday to preside at Nutrioso. Jane always did her part and never faltered in any responsibility that was placed on her. She entertained general and stake authorities. At times there were as many as twenty-one people in her home at one time. It was a common occurrence for her and her husband to sleep on the floor with one quilt under them and one over them, when visitors were occupying the beds. (When polygamous raids were going on, those on the underground were also taken care of.) In fact, not even a tramp was ever turned away from her door hungry. Everything she had in her home has always been shared with others.

On November 28, 1909, after thirty-nine years of married life, Jane was called upon to face death again. This time it was her companion. She met this with head up, face forward, and when another responsibility of rearing her family alone was thrust upon her, again she never flinched. By the next spring, she was back on the ranch and had ranch life going as usual. She helped send her two youngest children to college. Another boy was sent on a two-year mission and then to the World War.

From a pension her husband received for guarding the mail line in the early days of Utah, she has maintained herself and for many years has spent most of it in temple work. She has always been very active both in body and mind. In fact, she has grown old beautifully.

It has been the delight of her children, grandchildren, and those who have married into the family to visit with her and feel of her sweet influence. They especially like to joke with her, for she is so keen of wit that none ever got the better of her. Because she is so active, no one would guess her to be eighty-five years of age from looks or manner. Her large posterity all delight to do homage to her, and all are glad to have her spend all the time she can stand to be away from her beloved Alpine in their home. These visits are never very long, for although she seems to enjoy them very much, she shows most enthusiasm about going “home.” To see the welcome every child in Alpine gives his “grandma” when she returns is indeed touching. To come into her presence is a privilege. To associate with her is an inspiration. She has passed through many trials in life, but she has met them bravely and uncomplainingly. Her personality radiates courage and good will; it stimulates lofty thoughts, and inspires one to self effort and worthy deeds.

Her inspiring life came to an end on December 17, 1945, when she had reached the ripe old age of ninety-three years.

Ellis and Boone:

The ancestry of Ann Jane Peel Noble, as reported here, has interesting Mormon history implications. In early April 1840, Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, Parley P. and Orson Pratt, and George A. Smith arrived at Liverpool, England, in what was later known as the British Mission of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles.[42] Three days later, these men traveled north to Preston, passing through Lancashire, an early center for linen production and in 1841 cotton cloth manufacturing. Preston had earlier been the site of many missionary baptisms. On April 12, seven members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles spoke to a congregation of five hundred plus Latter-day Saints at a dissident gathering location, the Preston Cock Pit. Later that week, a conference was held with nearly 1,600 people present, and Brigham Young proposed publication of the Book of Mormon, a hymnal, and a monthly magazine called the Latter Day Saints’ Millennial Star; all consented.[43]

However, although Benjamin and Nancy Peel were from this area and joined the Church as the result of later missionaries, it was the cotton industry which influenced the Peel family, the Church, and United Kingdom. When missionaries first entered Preston, they were shocked at the result of industrialization; Preston had at least thirty-eight cotton mills and about sixteen thousand people working in them.[44] Poverty was rampant. Particularly onerous was the Corn Law of 1815. A stagnant economy after the Napoleonic Wars left the landed gentry wanting to prop up prices by imposing tariffs on imported grains. With the Corn Law and bad harvests, food prices were high, resulting in hunger and suffering. Industrialization also meant the rise of a middle class which was not willing to be unrepresented in parliament.

Sir Robert Peel was born April 15, 1788, and grew up amid the cotton mills of Lancashire. The son of a wealthy mill owner, Peel was educated at Harrow and Oxford and became a member of parliament in 1809. With this background, he saw industrialization as inevitable and worked to make it beneficial. Peel served as chief secretary for Ireland (c. 1812–17) when Roman Catholics were not allowed seats in Parliament. He reformed the criminal laws of England (1820s) and set up a police force in the Greater London area. The men were known as “Bobby’s Boys” and later simply “Bobbies.” This was the era when slavery was outlawed in England and when the first child labor and public health laws were enacted. Peel served as British Prime Minister from 1834–35 and 1841–46 and was responsible for the 1846 repeal of the Corn Laws during the Irish potato famine. He believed in free trade, was the founder of the Conservative Party, and saw government ministers as responsible to the state rather than to their party, thereby preserving parliamentary government during the rapid social change and class conflict resulting from industrialization.[45] One of his biographers, Norman Gash, wrote that “more than any other man, he was the architect of the mid-Victorian age of stability and prosperity that he did not live to see.”[46] Sir Robert Peel died in 1850 as the result of a carriage accident.

In England, the 1840s were called the “hungry forties.” Benjamin Peel is reported to have been a “calico printer,” possibly meaning a dyer of cotton. Sir Robert Peel, seeing the suffering in Ireland and England, spent his entire life working toward a better society. Mormon missionaries, particularly the members of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles, found a field white and ready to be harvested in Lancashire. All of these factors came together when Benjamin and Nancy Peel listened to the gospel message, were baptized, and immigrated to St. Louis in 1849. Their daughter, Ann, was born in St. Louis, grew up in Utah, and married Edward Noble. She lived most of her adult life in Arizona, and this part of her background is known simply because she told RFC, when being interviewed for the Federal Writers’ Project, that her father was the nephew of Sir Robert Peel.

Christina Archibald Hubbard Nuttall

Author Unknown

Maiden Name: Christina Archibald Hubbard

Birth: January 31, 1870; Grantsville, Tooele Co., Utah

Parents: Elisha Freeman Hubbard[47] and Agnes Archibald

Marriage: John Horatio Nuttall; August 20, 1887

Children: Agnes (1888), Joseph (1890), James Floyd (1895), Etta (1899), Freeman Karl (1901), Margaret (1902)

Death: August 25, 1940; Pima, Graham Co., Arizona

Burial: Pima, Graham Co., Arizona

Christina Archibald Hubbard, daughter of Elisha Freeman Hubbard and Agnes Archibald Hubbard, was born January 31, 1870, in Grantsville, Tooele County, Utah. At Christina’s birth, her grandmother, Agnes Christina [Kinghorn] Archibald, acted as doctor and nurse (midwife) as they were called in those days. Her life seems to have been spent in moving from one place to another. Because of ill health of her mother, her father sold his sheep. He was well equipped with wagons and horses to make the trip to Arizona. They traveled in company with other families who were going to Arizona. They were delayed fifteen days on the road by an accident to Sam Bryce who was hurt while swimming in the Sevier River. They crossed the Colorado River at Lee’s Ferry. It was rising and dangerous with trees floating down it. It took five boatloads to cross it, and they swam the stock across. Later they had trouble crossing the Little Colorado. When they reached Winslow, Arizona, they stopped and worked on the railroad for three weeks.

Teena’s father and family came to the Mormon settlement at Snowflake, Arizona. John H. Nuttall and his wife Laura Gardner Nuttall were living there. Little did Teena think at this time that one day she would be a member of that family.

Christina Archibald Hubbard Nuttall. Photo courtesy of Craig M. Reay.

Christina Archibald Hubbard Nuttall. Photo courtesy of Craig M. Reay.

They left Snowflake in company with Philemon and Henry Merrill and their families to go to Fort Thomas.[48] When they got to Fort Apache, they found the Indians were on the warpath. With all possible haste, they drove on without stopping to unhitch their teams to St. David on the San Pedro River in southeastern Arizona, arriving on May 5, 1881.[49] Teena’s father began freighting from Willcox, which was the end of the railroad for a long time, to Tombstone, the desert town of cattle ranchers and miners.

Teena’s father made a trip back to Sevier River in Utah to get some stock he had left behind. He left the teamsters in charge of Daniel Eldridge while he was away.[50] Her brother Robert, who was a small boy, fell from one of the freight wagons and was killed.[51] The father was detained on the return trip by Indians on the war path and did not hear of the death until three weeks after it happened. As he passed through Mesa, some friends told him of the accident. He reached home tired and sick and brokenhearted. The grief-stricken mother never recovered from the shock of her boy’s death. She died August 5, 1884, and was buried beside her son Robert in St. David, Arizona.

After the death of his wife, Mr. Hubbard made another trip to Utah to visit relatives, leaving Freeman and Hulda to care for the home. He left Teena with a neighbor, Lizzie Layton, who was kind to the children after the death of their mother and brother.[52]

After a year’s absence, the father returned bringing his new wife, who was joyfully received by all the children.[53] She was a good stepmother, and, in later years, Teena said of her that she was so glad to have her for a mother. She always wanted to please her.

At this time, men of good character and ability were counseled to marry more than one wife with the consent of all concerned. Teena was now sixteen years old. When John Horatio Nuttall asked her to be his plural wife, she accepted with the blessing of his wife Laura. The fact that he was much older than she and had a wife and five children made no difference to Teena. Teena and John were married April 20, 1887, in St. George Temple. They lived happily at Pima, Arizona, where their first child, a girl, was born in April 1888.

In 1889 the Edmunds-Tucker law was put in force by the United States government.[54] This law prohibited plural marriage. Men who would not comply were either sent to prison or were forced to take their families to Old Mexico where there was no law against polygamy. Many men took their families to Mexico; among them were John and Teena Nuttall. These people had many trials and hardships in this newly-formed colony of Juárez. There, Teena’s second child, a boy named Joseph, was born April 8, 1890.

By this time persecution had somewhat died down in the states, and the Nuttalls returned to their home in Pima, Arizona, where they were warmly welcomed by Laura. Teena went to Salt Lake City to the dedication of the temple. She went with her father; there they did some temple work. Then she returned to Arizona with her father and another family. It took them twenty-three days to make the return trip, and Teena drove all the way.[55]

From Pima they moved to the little town of Hubbard, which was named for her father. There she taught the neighborhood children their lessons. This was the first school in Hubbard, and she taught in her own two-room house.

She lived on the Nuttall Ranch at Bryce for sixteen years. Several of her children were married while she lived there, and two more were born there. She bought a store in Bryce, which she operated and was manager of the United States Post Office there until 1920. After the tragic murder of their beloved Laura on September 10, 1925, John and Teena lived at Pima until he died in April of 1931, after fifty-four years of married life.[56]

Teena’s was a life of adventure and service. She was greatly loved by everyone. After the passing of Laura, she did everything she could to make the remainder of John’s life happy. They enjoyed fifty-four years of married companionship.

Christina Archibald Hubbard Nuttall. Photo courtesy of Craig M. Reay.

Christina Archibald Hubbard Nuttall. Photo courtesy of Craig M. Reay.

Teena was a thrifty homemaker, always learning and doing for others. She spent much of her time nursing the sick besides caring for her family. She was always a good member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and held many offices in it.

After a lingering illness, she passed away on August 23, 1940, at the home of her daughter Agnes in Safford. She was laid in the family plot in the cemetery at Pima.

Ellis and Boone:

This sketch for Christina Hubbard Nuttall illustrates many of the ways Arizona pioneers coped with the pressures of polygamy, particularly a polygamous marriage contracted only a few years before the Manifesto of 1890. Christina, as a second and younger wife, was responsible for providing much of her own support, though this does not imply that the first wife did not also help support the family. John and Christina spent time in Mexico, leaving Laura in the Gila Valley; then they returned to Arizona after the Manifesto and after Arizona courts no longer prosecuted polygamous marriages (believing that a normal death rate would eventually bring an end to the practice). The trip to Utah was another way to handle polygamy, and sometimes these trips were several months to a year in length. Finally, after Christina returned from Utah, it seems likely that she never lived in the same town as Laura, who was in Pima; Christina lived on the ranch and in Hubbard, leaving her status slightly ambiguous to law enforcement officers. Nevertheless, both women gave birth to their last child in 1902.

After the death of Laura in 1925, Christina moved to Pima and lived with John Nuttall full-time until his death in 1931. Thus Christina experienced five-and-a-half years of monogamy, though surely she substituted, at least somewhat, as a grandmother for Laura’s family.

Laura Naomi Gardner Nuttall

Author Unknown

Maiden Name: Laura Naomi Gardner

Birth: June 10, 1859; Provo, Utah Co., Utah

Parents: Charles Gardner and Rhoda Elizabeth Kellogg

Marriage: John Horatio Nuttall; June 7, 1875

Children: Laura Lizette (1876), Mary LaPrele (1878), John (1880), Charles William (1882), George (1884), Ernest (1887), Annie (1889), Alice Rosemond (1891), David (1894), Maude (1897), Paul (1902)

Death: September 10, 1925; Pima, Graham Co., Arizona

Burial: Pima, Graham Co., Arizona

These are the pioneer experiences of Laura Naomi Gardner, daughter of Charles and Rhoda Elizabeth Kellogg Gardner. She was born June 10, 1859. She was married to John Horatio Nuttall June 7, 1875, in the old Endowment House in Salt Lake City. John H. Nuttall was the son of William Ephraim and Mary Langhorn Nuttall. He was born December 14, 1854, at Provo, Utah. His family left Liverpool, England, and came to Utah with a company of Latter-day Saints known as the Deseret Sugar Manufacturing Company, because they bought and brought along with them the machinery to make sugar from the beets that President Brigham Young was having the Saints in Utah raise for that purpose and had ordered this machinery. John’s father was a mechanic, and it was his job to run this sugar mill when it was set up.

The first home of John and Laura was at Wallsburg, Utah, where two little daughters were born to them.

Laura Naomi Gardner Nuttall. Photo courtesy of Eastern Arizona Museum and Historical Society, Pima.

Laura Naomi Gardner Nuttall. Photo courtesy of Eastern Arizona Museum and Historical Society, Pima.

The call came from Church Authorities for folks to settle the new land of Arizona. These two young people with their little girls came to northern Arizona with a small band of settlers in 1879 by ox team and covered wagon to make a new home.[57]

Laura tells about a scare she and John got while they were living in Forest Dale. The snow was deep around their one-room cabin, and John was snugly tucked in bed. She was getting ready to join him. She was facing the small window, when she suddenly screamed and fell over in a dead faint. John jumped from bed, grabbed his gun, which always stood by the door, and dashed out in the snow to get the Indian he thought had scared Laura. While poor John prowled around in the snow, she came out of the faint and got into bed, not daring to tell John it was not an Indian but her petticoat had fallen down across her feet which she thought was a mouse. To this day, when Indians are mentioned, John growls. Indians—huh? Her baby LaPrele learned to talk the Indian language from her Indian neighbors and playmates.

John, being a good carpenter, made coffins for the people who died, and his wife helped to wash and lay out the bodies. The first time Laura helped with a dead woman in Forest Dale, she felt such horror that she prayed and promised God if he would take the memory of that horror away she would never refuse to help whenever she was called. They helped nurse many sick Indians and gave them consecrated olive oil and saved many lives by the elders blessing them by the power of the priesthood.

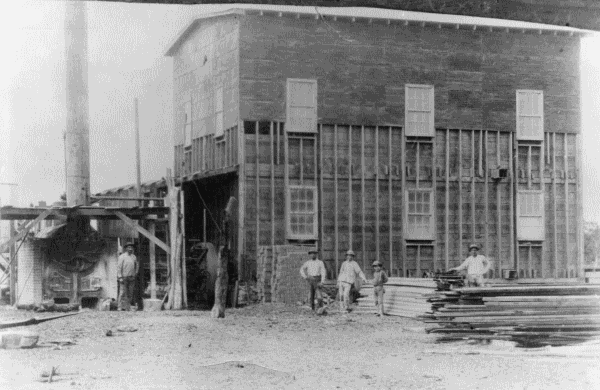

The Nuttall sawmill in 1899 as it was being dismantled to move it to Bryce. Note the shape of the burner on the left (which is usually tepee-shaped); potential spontaneous combustion of the sawdust made a burner imperative. Photo courtesy of Craig M. Reay.

The Nuttall sawmill in 1899 as it was being dismantled to move it to Bryce. Note the shape of the burner on the left (which is usually tepee-shaped); potential spontaneous combustion of the sawdust made a burner imperative. Photo courtesy of Craig M. Reay.

Because of the frequent uprising of the Apaches, Forest Dale was abandoned.[58] John and Laura and some of their friends moved to Gila Valley in southeastern Arizona and settled the town of Pima. These settlers learned from the Mexicans how to make adobe. It is a mud brick that is laid out in the sun and dried till it can be handled and built into houses like burnt clay brick.

John dug a good cellar near a big mesquite tree covering it with branches and brush and dirt. He used this clay to make adobes with which he built a two-room house. This was still in use in 1932. Their first baby boy, John Jr., was born June 20, 1880, on this home place. Little Lizetta had died, and Laura took her two little ones and made the long hard trip back to Wallsburg to visit her people. While there her second son, William, was born. On the way back to Pima, William died. She also lost another son George in infancy. Her other children were Ernest, Annie, Alice Rosemond, David, who died young, Maud, and Paul. Their son John was the first white boy born in Pima, Graham County, Arizona.

Laura’s husband, John, bought and operated the first sawmill located in the Graham Mountains in a canyon among the pine trees that still bears the name Nuttall Canyon. They used ox teams to take the logs to the mill and to freight the clumsy wagons loaded with new lumber the twenty miles to the home lumberyard in Pima.

Laura would take her little family of children and move up to the mountains living in the lumber shack and cook for her husband and the lumberjacks all summer. In winter they returned to their home in Pima. They built and operated one of the first roller flour mills in the valley. The first dance hall in the valley was built by John Nuttall on his lot. He owned an old violin and was often a one-man orchestra for townspeople to dance there.

At this time polygamy was sanctioned by the Church. With Laura’s consent and approval, John took Christine Archibald Hubbard to the St. George Temple to become his plural wife.[59] He moved the flour mill to a farm on the north side of the Gila River. Here he built a home for his second wife and family.

Laura took great pride in her flower garden. She had brought rose bushes and purple lilac bushes from Utah. She was never selfish with her flowers but gave hands full of flowers to neighbors or sick friends. She always said that for every flower she picked, the bush would put out two more. The trees in their yard always had plenty of fruit on them to which the neighbors were welcome.

Her positions in the Church were too numerous to mention. Her chief joy was the young people’s organizations over which she presided as stake officer for twenty-five years. The Relief Society and the Sunday School came in for their share of her valuable teaching. Her home was always open to young people and visiting Church leaders. She was a lover of good books and encouraged everyone to read them.

When the Salt Lake Temple was dedicated, John was sent by the high council of the St. Joseph Stake to represent the stake. Laura and the children drove him to Willcox. There he took the railroad, and Laura drove the wagon back to Pima.

Their son Paul filled a mission for the Church. They took care of their daughter LaPrele and her three children while her husband also filled two missions to the Samoan Islands.

Laura’s beautiful life was brought to a tragic end. She was brutally murdered by a drug addict. He was captured, and while in jail he took his own life to escape the vengeance of the infuriated family and valley people who loved Laura.

She was laid to rest in the Old Pima Cemetery September 1925, there to await the glorious resurrection. She and John had been happily married for over fifty years.

Ellis and Boone:

Laura Nuttall died on September 10, 1925, two days after being attacked by Robert E. Lee Johnson. He was married to Laura’s daughter, Annie Nuttall, on August 14, 1924. Johnson died October 8, 1925.

Sarah Allred with her husband Alex C. Hunt, 1901. Photo courtesy of Graham County Historical Society.

Sarah Allred with her husband Alex C. Hunt, 1901. Photo courtesy of Graham County Historical Society.

While Laura Nuttall’s sad death is probably the most unique aspect of her life, the most noteworthy is really her work with the young women of the St. Joseph Stake. She was president of the stake young women’s organization from 1888 to 1900 with Sarah Burns, Jane Wright, Eva Rogers, Lydia E. Williams, Josephine O. Rogers, Rhoda Foster, Emma M. Walsh, Lucinda M. Gustafson, and Sarah Allred serving as counselors at various times during this period.[60]

Lucinda Matilda Dodge Green Gustafson. Photo courtesy of Graham County Historical Society.

Lucinda Matilda Dodge Green Gustafson. Photo courtesy of Graham County Historical Society.

The Young Ladies’ Mutual Improvement Association is probably the least reported auxiliary organization during pioneer times. The first YLMIA in the St. Joseph Stake was organized on June 15, 1883, with Sarah D. Curtis as president and was reorganized on March 23, 1888, with Laura Nuttall as president; normal activities for teenage girls can probably be assumed.[61] During the last year of Christopher Layton’s presidency when he was sick, all church activities languished. Consequently, a new stake presidency went from ward to ward reorganizing and bringing new enthusiasm to the congregations. At the end of this period, on February 26, 1899, the young ladies’ organization provided a luncheon honoring President Andrew Kimball and may have sponsored the dance that evening.[62] In 1900, the young women of Pima sponsored a Valentine’s Ball, held at the Weech Opera House, with an admission price of 50 cents.[63]

But the most important activity may have been to encourage the young girls in their schooling. Laura Nuttall’s last two counselors were a good example for the girls. Lucinda Green Gustafson was an early schoolteacher in Smithville-Pima and then operated a millinery shop in Pima.[64] Sarah Allred Hunt, a granddaughter of Christopher Layton, attended the St. Joseph Stake Academy in Thatcher from 1891 to 1893 and then spent a year at the Brigham Young Academy in Provo, Utah. Returning to Arizona, she taught at the St. Joseph Stake Academy and in the Graham and Bryce schools. In 1896, she helped organize the young women for a Fourth of July float honoring the original American colonies; Sarah herself rode behind the horse-drawn wagon carrying a banner reading “Arizona, the Coming State.”[65] Both of these women later became gifted historians of Graham County.

Pioneer Service: Visiting Teachers in Tucson. Shortly after Latter-day Saint women had their own organization in Nauvoo, Illinois, in 1842, charitable work was promoted by in-home visits. These visits have continued through the years and include both assessments of familiy needs and gospel discussions. In 1957, Clara Busby (left, age eighty), Agnes Watson (center, age ninety-one), and ouisa Done (right, age eighty-eight) were honored by th Tucson Stake Relief Society for their service as visiting teachers. It was noted that each month Busby traveled 100 miles, round trip, to visit her assigned sisters. Photo courtesy of Joyce Goodman McRae.

Pioneer Service: Visiting Teachers in Tucson. Shortly after Latter-day Saint women had their own organization in Nauvoo, Illinois, in 1842, charitable work was promoted by in-home visits. These visits have continued through the years and include both assessments of familiy needs and gospel discussions. In 1957, Clara Busby (left, age eighty), Agnes Watson (center, age ninety-one), and ouisa Done (right, age eighty-eight) were honored by th Tucson Stake Relief Society for their service as visiting teachers. It was noted that each month Busby traveled 100 miles, round trip, to visit her assigned sisters. Photo courtesy of Joyce Goodman McRae.

Notes

[1] Errors in PWA (including one line omitted) have been corrected from the FWP sketch.

[2] Perhaps this should read “Navajo, Hopi, and Havasupai” (although the Havasupai were generally further west); Oraibi is simply one of the Hopi villages.

[3] This reference is probably to garnets. W. P. Blake reported in the 1909 Minerals of Arizona that J. L. Hubbell of Ganado had identified an area about seventy-five miles west where, over a stretch of about ten miles, “garnets are picked up from the surface by the Indians. They occur in sandy soil, and are uncovered by the action of the wind.” Also, in 1910 F. N. Guild published The Mineralogy of Arizona and wrote that the Moki (Hopi) Indians “bring into the towns large quantities of loose garnets many of which are cut and show a beautiful dark ruby tint. They are known among gem dealers as the Arizona rubies and are without doubt the finest garnets in the United States. They are picked up in gravel deposits and around ant-hills.” Both quotes from Anthony and others, Mineralogy of Arizona, 46–47.

[4] This location was apparently near present-day Cameron.

[5] Written as “Moabby” in PWA.

[6] Arroyo is the Southwestern word for gulch or ravine, often dry except after a rainstorm.

[7] Reilly, Lee’s Ferry, 103−4.

[8] For information about perennial and ephemeral streams, reservoirs that regulate water flow in Arizona, and fish habitats today, see Brown, Carmony, and Turner, Drainage Map of Arizona.

[9] Krenkel, Life and Times of Joseph Fish, Mormon Pioneer, 193–94.

[10] Minckley, Fishes of Arizona, xv. Today there are more than four times that many species, with both accidental and intentional introduction of other fish. Watersheds have also been drastically altered since pioneer times—with overgrazing helping to reduce the number of permanent streams and encouraging deep erosion, large and small reservoirs creating not only a change in the water flow but also the temperature of the water, the pumping of underground aquifers, and the consumption by the human population, which vastly increased.

[11] Ibid., 65.

[12] Ibid., 120–21.

[13] For information about the time in Mexico, see the sketch for Annie’s mother-in-law, Lydia Ann Lake Nelson, 483.

[14] Price W. Nelson died in 1946 and was buried in St. George, Washington Co., Utah.

[15] AzDC, Charlotte Ann Tanner Nelson; her son was the informant, listing her as “widowed.”

[16] “As told to, and written by, her grandson Joseph N. Brinkerhoff.” Life Sketch of Lydia Ann Lake Nelson, MS 841, CHL. This source also reported the time and place as “Eagar, Arizona – 1915.”

[17] “James Lake,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 2:287–88; “Philomela Lake,” in ibid., 2:388–99.

[18] In 1830, Samuel H. Smith, brother to the Prophet Joseph Smith, left a copy of the Book of Mormon with one of Brigham Young’s brothers. After two years of investigation, Brigham Young was baptized and almost immediately began preaching the gospel in New York and Ontario, Canada. Leonard J. Arrington, “Brigham Young,” in Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 4:1602.

[19] The area around Toronto was called Upper Canada until 1842, then Canada West, and with confederation on July 1, 1867, it became the Province of Ontario; the same name changes apply to areas further down the St. Lawrence River (i.e., Lower Canada, Canada East, and the Province of Quebec).

[20] Joseph and Hyrum Smith died June 27, 1844.

[21] Proverbs 28:1.

[22] Barnabas Lake was a private in Company A and spent the winter in Pueblo, Colorado, as part of the Brown sick detachment. Ricketts, Mormon Battalion, 22 and 238; “Barnabas Lake,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 3:136.

[23] Phineas (1799–1879) and Lorenzo Young (1807–95) were brothers of Brigham Young. Arrington, Brigham Young, 419. For a photograph of the five Young brothers, see Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 4:1603.

[24] This was a small group of fifty-six people, about half of whom were Lake family members, leaving in early June and arriving in Utah, September 4−5, 1850. James Lake was 62, and his wife, Philomelia, was 56. Electa Snyder Lake, wife of Barney Lake, died August 9, 1850. MPOT.

[25] Lorin Farr (1820–1909) was born in Vermont, the son of Winslow Farr; he was the first mayor of Ogden and the first president of Weber Stake. One of his daughters became the wife of President George Albert Smith. Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 1:749.

[26] While Lyman does not mention Price Nelson in connection with the lumber industry around San Bernardino, the sawmilling activities themselves are discussed in detail and were an important source of income for the community. Lyman, San Bernardino, 73–75, 113–17.

[27] William Bailey Lake died March 31, 1858, at Bannock Creek, Power Co., Idaho; he is buried in the Ben Lomond Cemetery, North Ogden, Weber Co., Utah.

[28] Lorania Nelson and Joseph Lehi Foutz Jr. were married on July 3, 1878.

[29] Here she uses the old word adopted; today, we would say that the children were sealed to their parents.

[30] This sentence was omitted from PWA and has been reinserted from the CHL sketch.

[31] Hubbard, Graham Co., Arizona, was where her daughter, Jane, lived with husband John A. (Jonathan Alexander) Allen.

[32] The FWP account was transferred to PWA with minimal change and the addition of one paragraph telling of Ann Noble’s death. One paragraph has been reinserted from the FWP account.

[33] “Edward A. Noble,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 4:597. Additional information for the Edward Noble family, including his second wife, Fanny Young, was published in 2000. Flammer, Life Stories of Edward Alvah Noble, Ann Jane Peel Noble, and Fanny Young Noble, 6−44.

[34] For information about Sir Robert Peel, see comments by Ellis and Boone.

[35] This is likely Ben Peel (age 25) and Nancy Peel (age 27), who arrived on the ship Berlin at New Orleans on October 23, 1849. On board the Berlin were 253 Mormons; 13 adults and 15 children died of cholera, and Sonne wrote that this was “the greatest death toll up to that time among the Mormon emigrant companies—11 percent.” “New Orleans Passenger Lists 1813−1945,” ancestry.com; Sonne, Ships, Saints, and Mariners, 28–29.

[36] “Instead” was left out of PWA and reinserted from the FWP sketch.

[37] The Benjamin Peel family, consisting of Benjamin (age 37), wife Nancy Turnbull (age 39), Ann Jane (age 10), Mary Francis (age 6), and Robert (age 3), came to Utah in 1862 traveling in the James Wareham Company. MPOT.

[38] Some of the Arizona pioneers left good homes in Utah and then worked hard to establish new communities in the deserts. When they saw friends decide the pioneering was too hard in Arizona and return to Utah, they were occasionally critical. But Rothschild and Hronek correctly noted in their book about Arizona women that the women’s “reactions to the desert were as varied as their personalities—some cursed a terrain they found harsh and bleak, while others saw beauty immediately.” Rothschild and Hronek, Doing What the Day Brought, xxxvii.

[39] Although there is a problem with the date, this should probably be Nathan Tenney who died on June 24, 1882. Wilhelm and Wilhelm wrote, “In 1883 the tension in St. Johns reached an all time high. . . . As the pressures continued to build, a call was issued for 102 Utah families to move to St. Johns to bolster the settlement. The thought behind this was to gain dominance over the anti-Mormon element by sheer weight of numbers. As Apostle [F. M.] Lyman stated, We expect this difficulty here to be settled by the steady growth of our people. The order of the day was to hold St. Johns at any cost, lest it become a second Carthage.” By 1886, problems with the St. Johns Ring had subsided. Wilhelm and Wilhelm, History of the St. Johns Arizona Stake, 49; see also 29−39, 45−50. See n. 85, 537, for an explanation of the updated spelling and information about Hawn’s Mill.

[40] It is not clear in either the FWP or PWA account who is talking. Presumably this is Ann Noble, and the reference to father and mother in the next sentence means Edward and Ann Noble.

[41] “Edward A. Noble,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 4:597.

[42] Allen, Esplin, and Whittaker, Men with a Mission, 81–83.

[43] Arrington, Brigham Young, 81.

[44] Allen, Esplin, and Whittaker, Men with a Mission, 28.

[45] “Sir Robert Peel,” in New Encyclopedia Britannica, 9:237–38, 29:82–85.

[46] Ibid., 238.

[47] “Elisha Freeman Hubbard,” in Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 4:600.

[48] This reference to Philemon and Henry Merrill in Snowflake is not their initial trip into Arizona. Both men originally came with the Daniel W. Jones Company via Stone’s Ferry in 1877 and later that year moved further south to settle St. David. Jones, 40 Years Among the Indians, 238–45; Cyrena Dustin Merrill, 441.

[49] This is likely from Fort Apache to Rice or Fort Thomas. Going from Fort Apache to St. David without unhitching the teams seems impossible because it implies that they drove through the night and for more than one night.

[50] In 1880, Daniel Eldridge/

[51] James Robert Hubbard was fourteen years old; he was born September 21, 1867, and died October 26, 1881.

[52] Elizabeth Williams Layton, 402.

[53] Almira Wilson married Elisha Freeman Hubbard on April 1, 1885; they had eleven children.

[54] The Edmunds-Tucker Act was enacted in 1887 but may not have been enforced in the Gila Valley until 1889. The U.S. government began trying to eliminate polygamy with the Morrill Act (antibigamy) of 1862, and the court cases of George Reynolds in the 1870s tested its legality. The Edmunds Act of 1882 and the Edmunds-Tucker Act increased penalties for polygamists until the Manifesto, which prohibited new plural marriages in the U.S., was issued in 1890 by President Wilford Woodruff. Ray Jay Davis, “Antipolygamy Legislation,” in Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 1:52–53; Van Orden, Prisoner for Conscience’ Sake, 58–91.

[55] The Salt Lake Temple was dedicated April 6, 1893, forty years after the cornerstone had been laid by Brigham Young. Marion D. Hanks, “Salt Lake Temple,” in Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 4:1252–54.

[56] For information on John H. Nuttall’s first wife (including her death), see Laura Naomi Gardner Nuttall, 494.

[57] A sketch in Mt. Graham Profiles states that they “left the 17th of October, 1878, by team and wagon with several families namely: Joseph K. Rogers, Arthur K. Newell and Hyrum Weech. The 23 of December, 1878, they arrived at Forest Dale.” Burgess, Mt. Graham Profiles, 1:272.

[58] It was also decided that Forestdale was on the Apache Reservation. See Smith, “Mormon Forestdale,” 165−208. Although Oran A. Williams does not discuss the Gardner/

[59] They were married April 20, 1887, and had five children. See Christina Archibald Hubbard Nuttall, 491.

[60] Taylor, 25th Stake of Zion, 407.

[61] Although local histories call this the Young Women’s Mutual Improvement Association, that name was not used until later. Gates, History of the Young Ladies’ Mutual Improvement Association, 430–32; Burgess, Mt. Graham Profiles, 2:368; Taylor, 25th Stake of Zion, 24.

[62] Ibid., 31.

[63] Ibid., 36.

[64] Burgess, Mt. Graham Profiles, 2:171–72. The Green family preserved her 1880 school records, and Ryder Ridgway considered these “a priceless portion of Smithville-Pima history.”

[65] Ibid., 2:93, 161, 365–66. For photos of Sarah Allred Hunt, see 322 and 496.